Abstract

Common themes of EU social policy include: the promotion of employment; improved living and working conditions; the equal treatment of employees; adequate social protection; and capacity building of the European citizenship. However, it is often the case that rural dwellers and, more specifically, rural NEETs, experience higher levels of marginalisation than their urban counterparts. Such marginalisation is evidenced by their exclusion from decision-making, public life, community, and society. These issues are compounded by an underdeveloped rural infrastructure, problematic access to education, limited employment opportunities, and a lack of meaningful social interaction. This study, a cross-sectional analysis, assesses a number (n = 51) of social interventions under the Youth Guarantee Programme from a social innovation perspective and presents a characterisation of examples of best practice across different dimensions of social innovations. This paper presents an examination of the potential of sustainable rural–urban ecosystems that are focused on supporting the symbiotic social innovation diffusion methods which can help to establish and sustain rural–urban pathways to improved education, employment, and training.

1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) typically supports young people aged between 15–24 years who are not in employment, education, or training (NEETs) via policies that target the following interconnected areas at the individual member state level: employment; education; social work; and youth engagement. In the context of employment, each country must develop an aligned European employment strategy coordinated with the other member states, which should contribute to the management of common policies and the involvement of local governments, trade unions, and employers’ organisations [1]. In the area of education systems, this cooperative approach between the member states is intended to contribute to the development of high-quality education recognised within and across the European community [2]. The circumstances underpinning these common themes of the EU social policy are: the promotion of employment, improved living and working conditions, the equal treatment of employees, adequate social protection, and the development of human resources [2]. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan (2021) sets out guidelines for the member states relating to the need to achieve high levels of employability, skills, and strong social protection systems [3]. The Action Plan projected that, by December 2020, 16 million people would be unemployed, and youth unemployment would be at 17.8%, well above the overall population unemployment rate. Therefore, it was the goal of the Action Plan to reduce the rate of youth unemployment or NEETs from 12.6% to 9% over the lifetime of the plan. However, during the last decade, the recession exacerbated the economic disparities across Europe, with more pronounced increases in unemployment rates, especially among youths in the southern European countries, which were more severely impacted [4]. Indeed, it may be the case that differences in institutional environments may help explain cross-country youth disparities [5]. Considerable differences are evident in terms of the efficiency of the school-to-work transition system (e.g., the period between the end of compulsory schooling and full-time employment involving many actors from education systems to the institutions operating in the labour market); labour market regulations; and labour market flexibility, which may affect the length of unemployment spells and gaps in experience among youths [5,6,7]. Therefore, it is clear that there is a need to develop a coherent overview of this challenging environment.

Consequently, the European Commission encourages the member states, along with the provision of targeted financial support [3], to implement the newly reformulated Youth Guarantee Programme with a particular focus on the development and provision of high-quality opportunities that have the capacity to support stable labour market integration. An action plan needed to be set up to implement the reformulated Youth Guarantee Programme adapted to national, regional, and local circumstances. For ensuring continuity across the European Union as far as is possible, the European Commission’s Youth Guarantee guidance document identifies the need to strengthen partnerships between Youth Guarantee providers and the relevant stakeholders at all levels of government for the duration of the work programme (2021–2027) [3]. There is also a need to adapt these action plans to suit the complexities of the regional contexts of the affected people as the geographical location of a young person’s residence can be an important contributing or limiting factor. For rural areas, it is recommended that a review of the restrictions on public employment services is carried out to ensure more efficient support, institutional arrangements, and practices in various fields (social affairs; health; education; and employment) that do not meet the needs of young people and encourages young people to simply abandon their pursuit of employment [8,9].

The revised and reinforced Youth Guarantee recognises that while some NEETs may need a “less support” approach, other more vulnerable NEETs are likely to need “more intensive, longer-term, and comprehensive measures” to avoid disproportionately experiencing the negative impacts that are typical of the demographic [3]. At a European level, seven different categories of diversity-related NEETs have been identified, which allow the member states to analyse and concentrate on more precise policy-making [10]

Even though the Youth Guarantee Programme acknowledges that certain sub-categories of youth are more likely to fall into the NEET status and, consequently, can be at a greater risk of social exclusion, scant attention has been paid to systemic exclusion in the context of rural areas in Europe. Since 2012, Eurofound has calculated that young people living in remote areas are at one-and-a-half times greater risk of falling into the NEET status than young people living in medium-sized cities [1]. Indeed, youth NEET rates vary significantly across European countries (and sometimes also within the countries), in which personal characteristics can correspond to different NEET traits [6], compounded by rurality. Exploring this further, such categorisations are still largely based on the assessment of the individual context and not the systems that influence that context. Institutional and structural risk factors are rarely addressed within youth programmes despite local structures that support labour market entry, the field of innovation, and education systems being critical elements of urban and rural area ecosystems. Returning to the aforementioned disparity of risk versus geographic location, there are also significant variances between countries in which the percentage of NEETs in the population can vary greatly from 8% (Netherlands) to 38% (Turkey) [11].

The empirical research on this topic is extremely limited. It is clear that there is a need to understand the institutional and structural factors that underpin the challenges associated with NEETs and the increased risk that youths living in rural areas experience [12]. In the case of the Youth Guarantee Programme and the aforementioned categories, coordination is based on working in the context of multilevel governance, which focuses on combining the work of formally separate organisations to achieve a specific public policy objective [13]. This approach calls on the member states to share good practices in order to attempt to decrease the cross-country differences that are evident in countries, such as the Netherlands and Turkey. It is for this reason that the European Commission collates and disseminates good practice through public knowledge centres. These centres present opportunities to establish a variety of channels (yet unexplored) that can help us develop a deeper understanding of vulnerable youth [14]. The reports and guidelines from the knowledge centres investigated in the present study (n = 51) present an opportunity to understand the links between the revised Youth Guarantee Programme and the best practices from a range of the member states and regions across Europe that focus on supporting young people in their transition from school to work. Making this transition is difficult, and rural regions, especially Europe, are commonly regarded as places with challenges relating to regional economic growth; high migration levels; a great need for mobility; and the scarcity of available resources, such as the diversity in career and social interaction opportunities. These challenges, relevant to 83% of the EU area in 2018, are compounded by demographic fluctuation and a higher risk of poverty [11]. To evaluate and interpret the reports reviewed in this paper, the authors take a holistic approach to the review process, embracing the perspective that interventions that aim to support the youth should not only make them fit for the (labour) market, but also build their capacities to be the future drivers of change and innovation, empowering them to respond to these extant challenges [12].

2. The Role of Social Innovation in Supporting Sustainable Responses to NEET Challenges

This article aims to contribute to the future development interventions that focus on NEETs by providing a heretofore absent broader view of the reasons that influence the movement of young people into the NEET status. Understanding the lives of young people from their perspective, by embracing them as co-creators of responses to the challenges they experience, is a critical factor in effective policy-making [15]. This process is as complex as the target groups that such policies strive to serve. This paper will inform this action by exploring various best practices from Europe under the Youth Guarantee Programme, regarding their capacity to support sustainable social innovation.

Historically, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has determined that policies for the financial redistribution in rural development are not enough to address the specific challenges of different regions and help them develop. This action must be supplemented with policies that aim to develop rural regions and make them more competitive by mobilising local assets and potential [16]. In this context, social innovation can help communities respond to local problems; sustainable effect change; and react to environmental, economic, and social challenges [17]. Kröhnert and coauthors [18] conclude that in peripheral rural areas, only those villages in which an active civil society takes the local problems into its own hands are likely to be able to adapt and adjust, stressing that negative demographic change will not cease in regions that lack innovation and whose citizens lack a collective sense [18]. At this level, the commitment and creativity of citizens, as well as their ability to develop sustainable action structures, can support the successful and sustainable development of interventions [19]. Following on from this, and concerning rural development, such acts of collaborative action in the form of social innovations are at the core of rural development and essential prerequisites for its success. Indeed, social innovation is a participative process, bringing together different actors from different backgrounds [19]. These diverse social systems are considered more innovative than uniform social systems as, in such systems, there is a greater openness and willingness to adopt new ideas [20]. Applying this perspective to social innovation suggests that actors with entirely different backgrounds, know-how, and interests have more potential to develop a successful social innovation than actors with similar interests and know-how. The diversity of capacity in rural areas is often very limited. Therefore, it is important that participation involves the fullest range of citizenship to ensure that sustainable social innovation is possible.

According to Peter and Pollermann [21], participation seems to be related to the education level, whereby graduates, civil servants, and white-collar workers are more likely to take part in such processes than blue-collar workers and unemployed persons. As such, the social contexts most in need of social innovation may also have the greatest difficulties in motivating and mobilising the actors necessary for successful social innovation, which can also be addressed by the education system or youth work. It is clear, therefore, that education has a particular role to play in this process as those who engage with the education system, such as NEETs who re-engage, are likely to be the individuals who will have the decisive role in the occurrence or even the success of a social innovation act. Increasing this capacity, especially in rural areas, will be decisive for the future of any region as part of a systemic and/or systematic response to the challenges experienced by NEETs.

Critical aspects for the success of social innovation, especially the underlying participation process, are the opportunities or constraints beyond the responsibility of the actors involved in any participation process. Examples of such factors are the culture/means of funding; organisational structures; basic judicial conditions to which a rural development process is subjected; and the readiness of superordinate public administration groups to get involved with and support (development) processes with an uncertain outcome. Thus, one of the challenges is to alter disadvantageous determining factors to ensure potential success. One important factor to add to the likelihood of implementing social innovation is the possible barriers [22]. For example, in the case of the LEADER initiative, Dargan and Shucksmith [23] examined the use of the concept of social innovation in the context of LEADER interventions. They found that it can be challenging to promote local development in places with no history of collective action [23]. While the social innovation capacity of our communities seems to have the motivation to respond when supported, the distribution of reliable social innovative practices in rural areas is far behind their urban counterparts. This paper seeks to understand what social innovation interventions can work in such contexts through a close examination of disseminated knowledge and to encourage further discourse and action.

3. Methodology

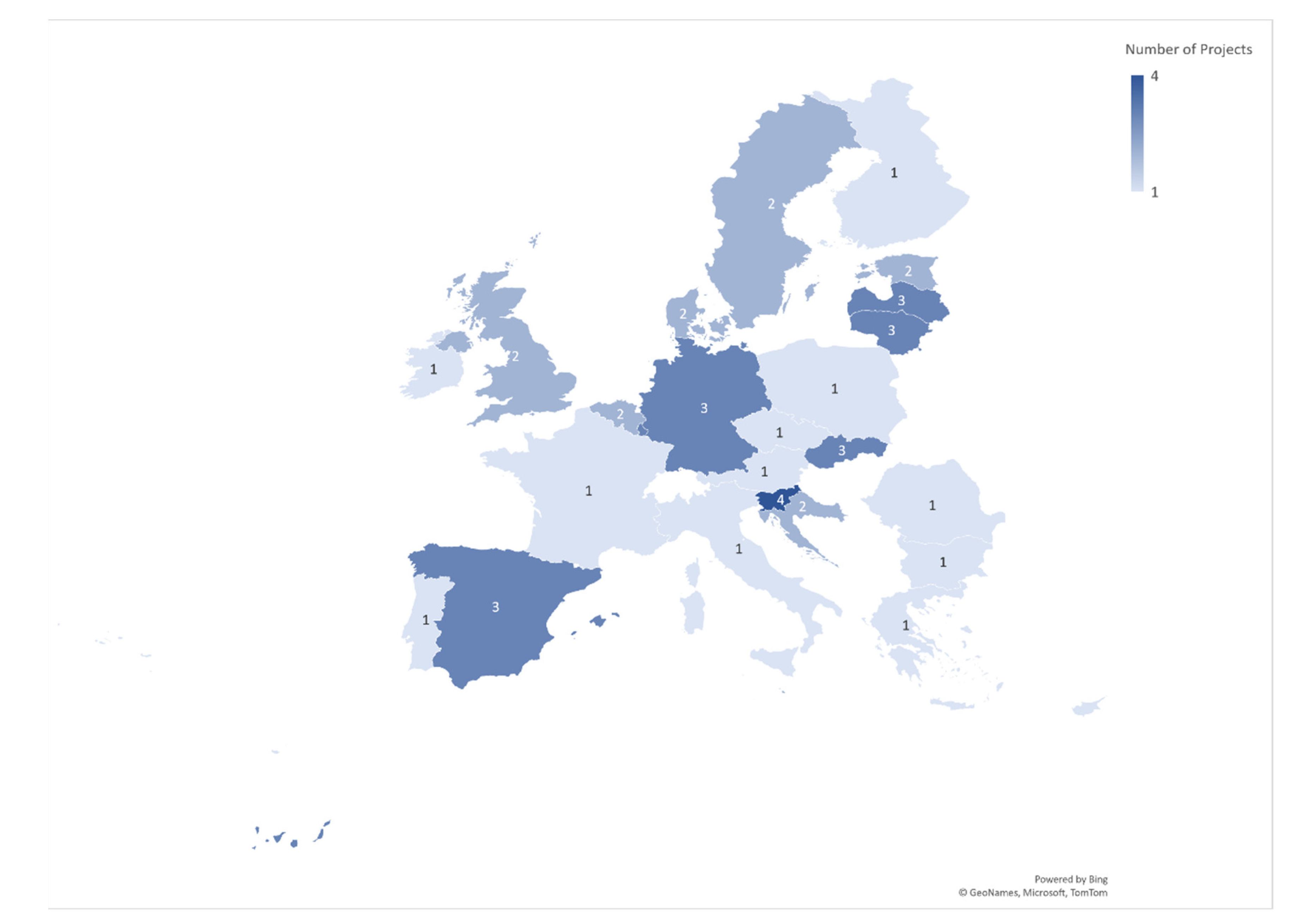

Employing a scientific realist review methodology, this article draws on documents presented on the webpage of the European Commission Knowledge Centre public channels, linked to the Youth Guarantee Programme, which allows all member states of the EU to upload their interventions and best cases. The documents are written from the national viewpoint and show the national and collective approaches to the extra curriculum services for youths from various nations of the EU. The reports are based on rural and urban experiences. This article aims to investigate how the youth programmes address or do not address social innovation factors, which are crucial for regional or rural development. In terms of methodology, a qualitative study that employs a scientific realist review methodology has been used. This review methodology has a number of important steps. In the first instance, the authors searched the European Commission Knowledge Centre public channels for different ideas, theories, and processes that reflect best practice in supporting youth transition into the labour market. Second, the authors narrowed the focus of the review by identifying commonalties across the document repository, bringing into focus the webpage linked to the Youth Guarantee Programme and the documents associated with this. Thirdly, the process was further advanced by searching for work that presented imperial evidence for appraisal. The authors appraised the documents independently and prior to synthesis. By analysing and synthesising the intervention documents, the authors attempted to understand the correlation between the implementation of the social interventions (under the Youth Guarantee Programme) and their impact on challenges associated with youth transition into the labour market in different European countries, thus achieving the aim of employing a scientific realist review methodology. The document repository comprises 51 documents and emerged from 27 different European countries. Slovenia has four interventions, followed by Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Slovakia as presented in the Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of projects.

There are two transnational projects (“Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships” conducted in Baltic countries and “Apprenticeship Toolbox” organised by Germany and its neighbours) in the database. The documents located in the database also provide information relating to the assigned budgets of the interventions. The budgetary support of the interventions ranges between 40,000 Euros (for the Open Youth Centre “Gates” in Lithuania, a local programme financed by the local administration) and 1 billion Euros (for the “Career entry support by mentoring” programme in Germany, a nationwide mentoring system). This budgetary distribution is noted as being skewed with 20 out of 51 projects having a budget lower than 10 million Euros and only 5 projects having a budget over 100 million Euros. The target population of all of the intervention projects is generally young citizens and NEETs. However, it should be noted that the definition of “youth” changes from one country to another. The lower age bracket is generally 15 or 16 years, and the upper bracket is 29 years, but, for some projects, this upper limit is defined as 24 years. The “MolenGeek” Tech Ecosystem project of Belgium also targets children above 11 years old.

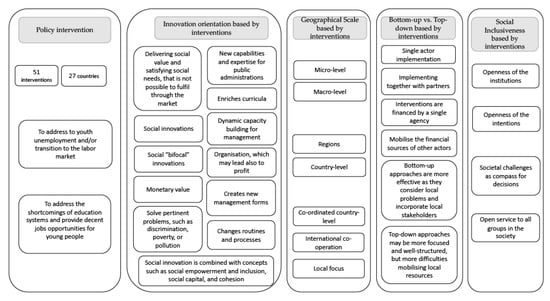

Summarising these specific interventions, we coded these documents according to our coding scheme, informed by the five aforementioned macro variables. We developed our coding scheme to reflect the dimensions of Baptista [24] and his coauthors using a holistic approach: two coders read documents and coded according to given directives.

Coding Scheme for the Evaluation Process

Baptista et al. [24] argue that government support and recognising the potential for the scaling of social innovations should be determined using a categorisation scheme. We identified five layers on how to include social innovation in youth work, namely policy intervention; profit orientation; geographical scale; organisation direction; and social inclusion. These layers are adapted from Baptista et al. [24] for use in this study and are presented below.

4. Findings

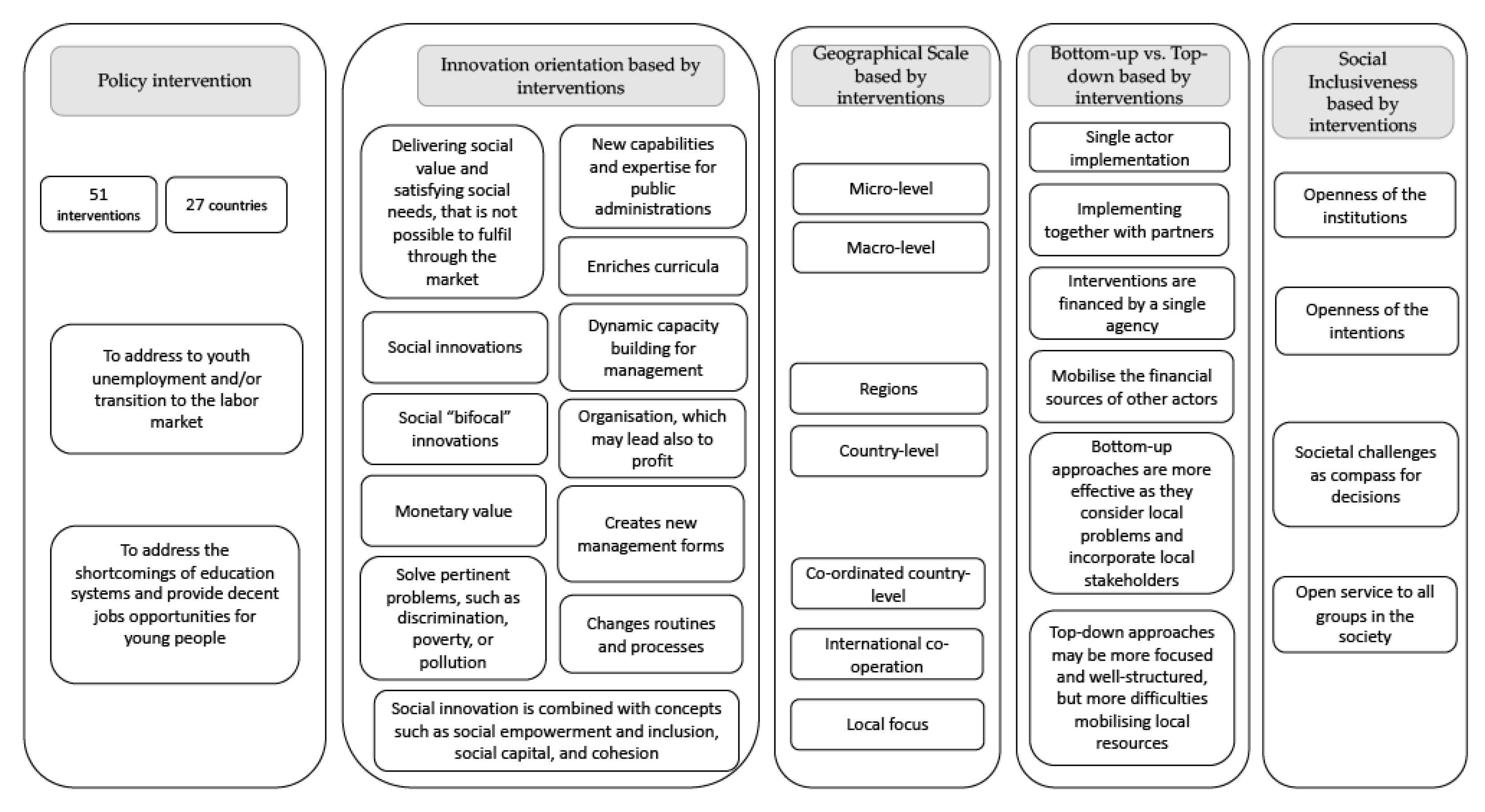

The analysis of all 51 documents covering 28 countries from the EU gave us a deeper understanding of how the youth programmes are organised and what aspects they address. In the present study, this analysis is presented thematically. Figure 2 below graphically shows the dimensions and subdimensions which we used in our analyses.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of social innovations.

4.1. Policy Intervention: Market Failure or Profit Generation

According to Baptista et al. [24] a several social innovations address market failures, such as the problems concerning school-to-job transitions. The cases analysed in this paper have different attitudes to the policy level for youth work. Some interventions attempt to solve market failures and others aim to establish new organisations, such as public and private partnerships. Given that the Youth Guarantee Programme aims to address youth unemployment and/or a transition to the labour market, the project’s primary objective is to address the shortcomings of education systems and provide decent jobs opportunities for young people. Almost every project we analysed targets the creation of jobs for youth cohorts; therefore, they can be accepted as policies that address market failures. However, some programmes support the nurturing of entrepreneurship in participating young people by channeling funds to young entrepreneurs. The “Self-employment Subsidy” project in Croatia provides subsidies to young entrepreneurs of up to 37,000 Euros, depending on the number of employees that are involved. The “Entrepreneurship Promotion Fund” in Lithuania provides microcredit of 25,000 Euros to young entrepreneurs, in addition to consultation service support. Another microcredit programme has been developed in Italy (the “SELFIEmployment” project) which channels up to 50,000 Euros to young applicants. As all these enterprises are profit-seeking, it is worth discussing to what degree these projects may be accepted as social innovations, as many of these investments are eventually turned into profit-making private institutions.

An additional point of discussion is the provision of individual incentives to the participants. Almost half of the projects we analysed channel material incentives to participants of approximately 30 Euros per day. This small incentive contributes significantly to sustained attendance and to the success of programmes, as noted by the organisers of these activities. Other programmes support employers for each young person they employ during the program, and this is a factor that contributes to the success of projects that adopt this approach as part of their engagement strategy.

4.2. The Profit Orientation

Another dimension of categorisation relating to social innovations is the tendency to generate profit from their activities. The studied cases have, in most instances, a variety of approaches in terms of defining “profit”. Some interventions only focus on “delivering social value and satisfying social needs, that is not possible to fulfil through the market” and we label these interventions as “pure social innovations”. Some others are social “bifocal” innovations, which generate a positive social value and create monetary value [24] (p. 386). Social innovation is also referred to when indicating the need for the society to solve pertinent problems, such as discrimination, poverty, or pollution [25]. In these situations, the focus rests on changes in social relations, human behaviour, as well as norms and values. Social innovation is then combined with other concepts, such as social empowerment and inclusion, social capital, and cohesion. In line with the profit orientation, the social innovation approach creates new capabilities and expertise for public administrations; enriches curricula; creates new management forms; changes routines and processes; as well as encouraging dynamic capacity building for management and organisation, which may also lead to profit. However, it is also possible that this can add new services and functions to potential new jobs.

4.3. Geographical Scale

This dimension refers to the capacity of social innovation to spread geographically, in other words, scalability. Some interventions can be only arranged at the micro level, and others at the macro level. Scalability means expanding social innovation to other geographic regions and countries [26]. The cases identified in this study are generally organised at the national level, and there are a few of them based on transnational cooperation. According to our analyses, 41 out of 51 projects are conducted at the national level using national organisations. We discovered seven projects that have regional focuses, three of them are from Belgium and two are from Spain. The “Traineeship First”, “MolenGeek”, and “Trecone” projects in Belgium are conducted in Brussels. Spain’s “Youth Guarantee Communication Plan through promoters” is a project conducting information activities in Catalonia, and “Technical round-tables for coordination of the Youth Guarantee at Municipal level in the Region of Murcia” is located in Murcia. Slovenia’s “First Challenge” project focuses on eastern Slovenia and Germany’s “Education & Business Cooperation” project is in Baden-Württemberg. It is evident that almost all regional-focused projects are located in countries in which the regional governments are compelling, or a federalist system exists. Only two international–transnational projects exist in the database. “Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships” is a project targeting “raising the status and enhancing the attractiveness of VET in the Baltic states by involving national social partners and VET provider organisations in the development of effective approaches.” It has been organised by the cooperation of the Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian ministries of education. The project has been successful in creating a dialogue between Baltic institutions. The second transnational project is “Apprenticeship Toolbox”, a project which aims “to create an online database—a ‘one-stop-shop’—housing reports and information on the different approaches to dual apprenticeships in the five participating countries,” namely in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, and Luxembourg. The project also aims to scale up the successful practices in these countries across Europe. These figures show that the scalability of projects is relatively weak, and many projects are conducted within the national boundaries.

4.4. Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down

This dimension focuses on the organisation of the intervention, whereby stakeholders are incorporated into the action. It also takes the sources of finance into account. Some interventions are organised and conducted by a single actor, and others incorporate other societal actors. Similarly, some interventions are financed by a single agency, and some others mobilise the financial sources of other actors [27]. This dimension is critical, as it has a demonstrable impact on the social innovation process in communities. According to Butkeviciene [28], the “bottom-up” and “down-up” approaches in social innovation seem to be more successful than “top-down” initiatives [28]. In terms of social innovation, the bottom-up approaches are more effective as they consider local problems and incorporate local stakeholders.

On the other hand, top-down approaches may be more focused and well-structured, but they will have difficulties mobilising local resources. We analysed these documents by asking two questions: which organisations are involved in the action and which institutions are financing them? Our analyses show that the state is the key actor in these projects. A total of forty-four out of fifty one projects include a state agency as the key actor. The public employment services (PES), ministries of labour or social services, ministries of education, and ministries of economics are among these state institutions. Two different factors may explain the dominant role of the state as the organiser of these activities. First of all, the Youth Guarantee Programme is an international body; it functions as a tool to be employed by government agencies. Secondly, the problem of NEETs is observed as a macro problem to be solved using macro interventions. As previously mentioned, the relatively lower number of regional projects is another indicator of this top-down approach.

Meanwhile, the role of the local governments presents a clue about the potential of local dynamics. Local governments are partners in nine projects, and they are the key actors in three. The “Trecone” project in Belgium; Spain’s “Youth Guarantee Communication Plan through promoters”, a project conducting information activities in Catalonia; and “Technical round-tables for coordination of the Youth Guarantee at Municipal level in the Region of Murcia” are projects coordinated by local governments. There is a conjunction between the regional focus and bottom-up approaches.

Civil society organisations (non-governmental organisations) are also active actors of these projects, and, in three of them, they acted as the main organiser. The “PULSA Employment” project in Spain is coordinated by Red Cross Spain and aims to empower youths across the country. The Open Youth Centre “Gates” in Lithuania has been operated by Actio Catholica Patria, a Lithuanian civil society organisation, and it provides services to young people visiting its centres. In other projects, civil society organisations have a supportive role. Our analyses show that the role of the private sector is also limited. Out of 51 projects, the private sector has a role in 6 projects, and it is the coordinator only in 1of them. An example of one of these projects is the “Talent Match” programme in the UK that has been organised with the support of the Big Lottery Fund and led by voluntary or community-led organisations. The involvement of the private sector has occurred via the incorporation of the umbrella organisations, such as the Chambers of Commerce and/or Industry, or they have been the beneficiaries of the project via subsidies provided for their employment. In a small number of projects, they are directly included in the decision-making process. From that perspective, we can conclude that the private sector has been observed to address the problem by providing employment. However, they are excluded from being an active actor in the decision-making process.

Similarly, the labour unions also had a limited role (5 projects), and they did not have any direct projects. A good example is the “Lifelong Career Guidance Centres—CISOK” in Croatia. The PES in Croatia operates these centres, and the labour unions are listed among the partners, without having any direct responsibility in the operation of these centres. Another example of this kind of division of labour was noted in the “Alliance for Initial and Further Training” project in Germany, in which labour unions are listed among the stakeholders without having any active role in the project.

The second sub-dimension we attempted to categorise is the financial structure of the projects. The majority of the projects were financed by the European Social Fund (ESF) programme and the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). In contrast, the local government contributed a small portion of the budget, changing between 8% to 15%. For example, 89% of the budget for “The First Challenge” in Slovenia (20.7 million Euros); 90% of the budget for “Through Work Experience to Employment” in Slovakia (31 million Euros); and 90% of the budget for “Second Chance Vocational Education Programs” in Lithuania (32 million Euros) have been financed by these two programmes. Meanwhile, Erasmus+ also financed some of these projects; for example, “Baltic Alliance for Apprenticeships” in the Baltic states and the “Young Adults Skills Programme” in Finland are two examples of that kind of contribution. Moreover, the contribution of the Erasmus+ programme is a meagre 200,000 Euros (out of 187 million Euros). These figures show that EU finance is essential for these projects.

It was also evident that the national governments channeled significant amounts of money to deal with this problem. For example, the Federal Employment Agency of Germany finances 50% of its “Career Entry Support by Mentoring” project (1 billion Euros) and the ESF has financed the rest. The French government channeled more than 120 million Euros to its “Guarantee for Youth” project (the total budget was 229 million Euros). In a small number of projects, the national budget was the only source of finance. “The Delegation for the Employment” in Sweden (15 million Euros), “Building Bridge to Education” (21 million Euros), and “Job Bridge to Education” in Denmark (17 million Euros) are examples of projects directly financed by the national budget. The private sectors’ contribution remains limited. In the case of the “Talent Match” project in the UK, the budget of 121 million Euros has been covered by the private sector. The private sector’s contribution remained extremely limited in the the “MolenGeek” Tech Ecosystem in Belgium (200,000 Euros). Similarly, other stakeholders’ contributions seem to be covering a minimal amount of money spent to solve this problem. Significantly, local governments, civil society organisations, labour unions, and other stakeholders have limited contributions to the projects. These figures show that the EU initiatives, the ESF, and the YEI are the most important initiators of interventions we analysed. The contribution from the national governments seems to be dependent on the fiscal capacity of the receiving countries. Germany, France, and Finland can channel a significant amount of funds, whereas the contribution of other member countries is limited. Meanwhile, it is possible to state that the private sector and other stakeholders have a very passive role in financing these projects. Considering all these facts, we can suggest that the top-down approach is the dominant method.

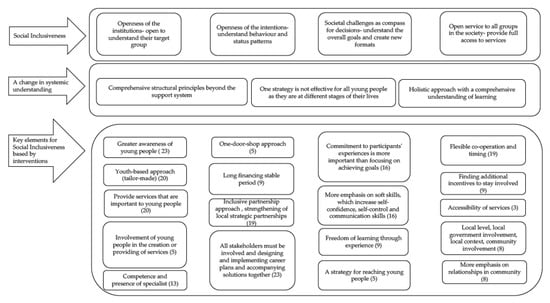

4.5. Social Inclusiveness

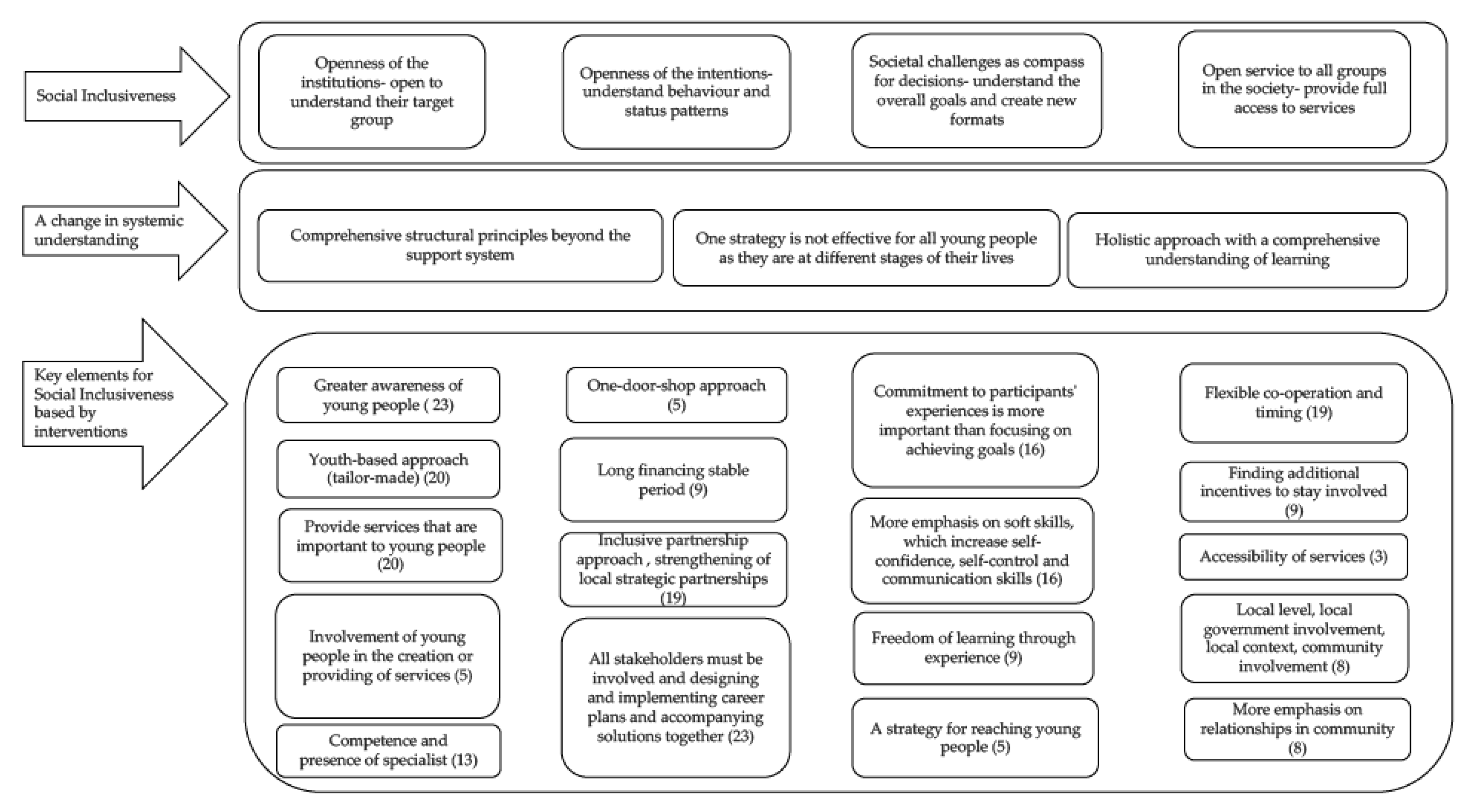

Social inclusion describes the participation of affected people in the process of intervention. In modern society, particularly disadvantaged people can enhance their opportunities, access resources, voice their needs, and gain respect for their rights through participation. According to Rogers [20], actors of successful social innovation must be from diverse social systems. In such systems, there is a greater openness and willingness to adopt new ideas [20]. Actors with quite different backgrounds, know-how, and interests have a greater potential to develop a successful social innovation than a network consisting of actors with similar experience and know-how. If an intervention explicitly states one or more vulnerable groups among its target groups, it will be considered suitable for classification as socially inclusive. The last dimension we used to categorise these documents was social inclusiveness. We defined social inclusiveness as openness, as presented in the Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Dimensions of inclusiveness.

Most NEET or youth projects and programmes aim to enhance the capacities for the job market. The analysed projects themselves are non-profit organisations or projects. They operate on a social dimension (common good) to make youths or NEETs employable. Being employable does not necessarily translate to the inclusion of the person in the society, nor does it suggest that the person can contribute through innovation to the society. Isolated people (geographically, education-wise, societally, or technologically) experience difficulties on various levels and areas of life, whereas social inclusion may, through contacts and relationships, ease the difficulties with support from the society on many levels. This can enable the person to be innovative regarding the pressing topics of the society (social, ecological, and technological innovation), which may also translate in the fruitful elaboration of projects, ideas, and business (e.g., for the youth entrepreneurship programmes). The inclusion or exclusion of persons is very much affected by the density of the population; the diversity of people in the society; and the encounters with different ideas, manners, and ways of doing things. People in rural areas may be less exposed to skills, solutions, and ideas, enabling them to be innovative in their surroundings. Densely populated societies can also live in a micro-world, in which certain disadvantaged people are not exposed to opportunities for innovation (e.g., migrant children, with weaker (local) language skills) and are, therefore, socially excluded.

The subjective perception of a job is often associated with social integration, but also with life satisfaction, the access to economic resources, and mental health [28]. Social status and higher self-efficacy are especially associated with employment and career. The negative effects of being unemployed are increasing with the duration of unemployment, as well as how early in life they occur, whereas having a partner and being highly educated reduces the negative effects. While we know that our current society cannot find employment for every single member, for the sake of resilience and wellbeing, we need to address the attached meanings to employment and find adequate solutions to those needs, too. This necessity is often neglected by the education and youth programmes. Analysing these potential dimensions of social exclusion is an important topic for future research. Less educated individuals suffer more from unemployment, which accounts for the cases of youth unemployment. Programmes that positively influence the perceived social status and self-efficacy can, prevent individuals from feeling rejected by society and, thus, avoid the onset of a downward spiral ending in long-term unemployment [29]. Social innovation actors from different backgrounds, know-how, and interests are potentially more successful in social innovation than actors with similar interests, know-how, background, and talents [20].

Consequently, the diversity of actors in areas with less population diversity, such as rural areas, may decrease substantially. Therefore, we conclude:

- The integration and empowerment of youths that engage in extracurricular activities can add the necessary diversity to the mainstream educated group of people in rural areas [30,31].

- Social inclusion is affected by the manner in which institutions in charge are operating. They can create the necessary “room to manoeuvre”, facilitating the emergence of social innovations [22].

- Youth work and education work can prepare young people for the engagement with social innovation.

- If social innovation actors are open to understanding their target group and engage with their communities, they must also be willing to embracing the characteristics of the people they support.

- Transparency is important as it allows new goals and outcomes to be established for the participants, which can evolve in the process and are therefore new for the institution and the participants (innovative).

- If they understand the overall goals and challenges (climate, resilience, etc.), scale up, and create new formats to maximise the local potential, this will facilitate social innovation.

- When social innovation actors provide full access to services without a restriction on gender, race, and/or geographical placement, this will open access to education and training pathways for all members of society.

The analysed projects provided a “starting package” with information about how to secure a smooth implementation, based on knowledge and experiences from the pilot phase. We assume that they were willing to understand their target group (openness of the institutions) and their decisions were guided with an inner compass of societal challenges. If the document addresses one of the vulnerable groups, we coded it as an inclusive social intervention.

According to our coding, two-thirds of projects do not have a clear definition of their target groups. These projects present their target groups as “young people”, “youth”, “school pupils”, or people younger than 29 years old. For some other projects, target groups are VET providers or other stakeholders. Hence, it is not possible to categorise them as inclusive projects. However, some projects have clearly defined their target groups. For example, the “Production Schools” in Austria includes young people with “special education needs or disabilities”; “Project Learning for Young Adults (PLYA)” in Slovenia targets young people who are socially excluded; Sweden’s “The Delegation for the Employment of Young People and Newly Arrived Migrants” aims to integrate newly arrived migrants; and “Alliance for Initial and Further Training” in Germany include migrants, young persons with disabilities, and disadvantaged young people in their target groups. Some other projects included favorable conditions for disadvantaged groups. Our analysis shows that social inclusiveness is not a common practice among the projects we analysed.

We indicated the numbers of interventions to visualise the scope of the proposals. Social innovation includes the development of new ideas and ways of working that offer better solutions to social problems and challenges than previous methods, leading to the more efficient functioning of society and the community. Social innovation offers solutions to social problems by developing innovative and better-functioning solutions. These can also be in the form of services. Given that our focus is on vulnerable young people, based on the descriptions of the interventions, factors can be identified that can help to reach and support the respective target group. According to our analyses (51 interventions), the involvement of young people with fewer opportunities is mentioned in the general plan in less than half of the interventions and it is less predictable through various explanations. Based on the interventions, it can be pointed out that although most of the interventions are universal and aimed at a wider target group, the description highlights the need to approach and offer more specific approaches to vulnerable target groups and to reach them. Half interventions repeatedly point out the understanding that the target group is not heterogeneous and, for this reason, there is a need for an individual, cross-sectoral, and youth-based approach (tailor-made method).

Poland’s intervention (Equal Labor Market) experience points out that individual support was needed for different age groups of the NEET target group and that one strategy is not effective for all young people as they are at different stages of their lives. The UK’s intervention (Talent Match) experience revelas that the development of young people who have lived chaotic lives and experienced trauma is not linear; it is important to work with them flexibly and for as long as necessary, without postponing meetings or having setbacks. It is important to point out that in a similar case there must be no time limits, otherwise support for a young person cannot be provided. In order to ensure an individual approach, factors such as the availability of the service (e.g., electronic registration; the proximity to home; local level; a lack of preconditions for participation; and additional incentives to maintain motivation, in addition to support and ensuring mobility) are also highlighted. Denmark’s intervention (Building Bridge to Education) experience describes how an individual and tailor-made approach also supports young people’s motivation and increases the likelihood of sustained education or training. Holistic views and strategic partnerships are the most mentioned key factors (23 interventions). In the Latvian interventions (KNOW and DO), it was highlighted that the establishment and strengthening of local strategic partnerships was key to ensuring that the strengths of local partners were fully utilised to reach and support the target group. This also included the development of a national information strategy and a common methodology for actions targeting young people at the national level, to ensure a common and shared approach between partners.

Furthermore, some interventions raised the participation of young people in the creation of the service as an important issue, and the commitment to the experience of the participants was more important than focusing on the achievement of the goals. Secondly, a specialist working with a young person was identified as an important party, whose knowledge and competence either created or limited opportunities for young people or networking practices. In the Slovenian (Project Learning for Young Adults (PLYA)) intervention emphasised that an inclusive partnership approach was important from this perspective, in which all major stakeholders (including participants themselves, as well as parents, support services/organisations, social partners, and schools) must be involved in designing and implementing career plans and accompanying solutions together. Luxembourg’s (National School for Adults (ENAD)) intervention suggested that common cooperation and mutual support among learners not only develops a positive work environment, but also enables learners to develop teamwork skills. Slovenia’s (Project Learning for Young Adults (PLYA)) intervention highlighted that more emphasis needed to be placed on soft skills, which increase the learner’s self-confidence, self-control, and the communication skills that benefit people throughout life, in both relationships and in the wider community. In the Lithuanian (Open Youth Center “Gates”) interventions, it was pointed out that to involve and support more youth, we must be able to provide the services they consider necessary for young people, not just following the priorities formulated by policymakers. The opportunity for workers and young people to experiment with new methods, tools, activities, and services, and the freedom to learn through experience is very important. Spain (PULSA Employment) also highlighted an innovative methodological approach whereby young people’s skills are assessed through informal activities outside the classroom (e.g., theater workshops, group games, and robotics).

Based on the descriptions of the interventions, it can be pointed out that although the services are aimed at everyone, there is a need for greater cooperation between different actors, in order to create more specific services based on the needs of young people. Most of the interventions are related to the European Commission’s recommendation to create quick support opportunities for young people on the basis of existing systems, but, at present, there is an opportunity to create new opportunities based on lessons already learned on the principle of social innovation. Given that social innovation represents new ideas and the way new solutions work, the interventions analysed offer better solutions to the social problems and challenges we face, making NEETs more effective for young people, society, and the community.

5. Conclusions

It is evident that tailoring social innovation activities to support the individual nature of education and training must be both the starting point and reference point for the design and implementation of learning environments. This position demands a comprehensive, holistic vision of how to support learners and it should take into account all areas and forms of learning and competencies, as well as the individual learner’s personality, lifeworld, and biographical (learning) history. While such an approach represents a paradigm shift from an institutional perspective to a strict learner centric perspective, the authors recognise that implementing such a comprehensive reform would require a resistance to the structural principles within education systems and their relationship with the wider social innovation ecosystem. However, reconceptualisation and, perhaps, new concepts of traditional structures of education are necessary, especially at the local (rural) level, if successful innovation is to be meaningfully connected to cultural contexts and to avoid reluctance or even refusal by stakeholders. It is also the case that successful strategies for establishing social innovation in education may not be fully transferable to other contexts or regions without also considering the cultural or regional context. This is an important consideration as reconceptualisation might therefore be more effective than disruption, for realising educational change.

In summary, it can be concluded that the findings presented in the present study can act as a starting point for further and deeper research in supporting sustainable rural pathways to education, employment, and training. Mission oriented social innovations can be based on a five-dimensional representation of interventions: policy intervention; the profit orientation; bottom-up vs. top-down organisations; and the last category, social inclusiveness. Following this, at a policy level, new European and national innovation strategies are required to sustainably support interventions. This includes the increase in awareness, visibility, acceptance, and implementation of social innovation and its underlying concept to improve the quantitative and qualitative contribution to education, employment, and training. At the core of this position is an acknowledgement that by addressing the individual capacities for social innovation and increasing the framework or ecosystem capacities, the youths can have a greater impact on the rural pathways open to them. This will require a reduction on the dependency of social innovations on formal support systems and in the silo thinking of public institutions. By adopting such an approach, public policy actors within a social innovation ecosystem will have critical input in areas previously marginalised or unknown. This cross-cutting perspective and the holistic approach of solutions, with the input of these stakeholders, will provide opportunities for collaborations that are focused on joint solutions that facilitate tailored support at different stages of the social innovation process, effective scaling mechanisms, and mechanisms leading to social change.

6. Limitations

Our work has significant limitations that extend our conclusions to a larger domain of interventions. First of all, our analyses are limited by documented interventions presented with a specific standardised format, which focuses on the accomplishments of interventions. This presentation undoubtedly hinders the failures and weaknesses of interventions, which require further investigation. An in-depth focus on the projects can reveal further information to create a clearer measurement of the social innovation dimensions of interventions. Secondly, these documents do not reveal information about the social impact of these interventions. Some of these documents include a specific section to present quantitative outcomes; however, it is not a common practice. A standardised toolbox for measuring the social impact of the programmes has not been developed yet, and it depends on the authors of the reports. In the medium term, this measurement can be included in the presentation of the results. The lack of this data prevented us from building a link between the social innovation of any intervention with its performance. Building such a link and proving it empirically would be an important contribution to the debate. To fill this gap, it is possible to select a sample of interventions and focus on this relationship. Finally, as these interventions are not developed from a social innovation perspective, our analyses became ex-post-facto and, sometimes, practically irrelevant, as many of them have already been completed. However, we believe that this article may include this perspective regarding the design and evaluation of the projects in the near future.

Independently of how radical the proposed changes are, social innovation is considered essential as an instrument and process to realise a transition towards more sustainable practices in urban/rural societies. This underlines the importance of better understanding how it works and how the process related to social innovation may be effectively supported. The role of the individual actors in the social innovation ecosystem is immense; therefore, the regions, despite whether they are rural or urban, must address this in their education programme (standard, voluntary, and extracurricular). The EU-wide policies and guarantees would make this new orientation more effective and can also emphasise a special attention to rural frameworks and ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization E.E., H.P., V.L.; methodology, E.E., H.P.; resources, H.P., E.E., P.F., B.N., H.P., V.L.; writing—review and editing, P.F., B.N., V.L.; visualization, H.P.; project administration, B.N.; funding acquisition, E.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18213 Rural NEET Youth Network, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology); https://rnyobservatory.eu/web/ (accessed on 28 August 2021) and the APC was funded by the COST Action CA18213 Rural NEET Youth Network.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available upon request by contacting Emre Erdogan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eurofound. Young People and NEETs in Europe: First Findings. 2012. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/resume/2012/labour-market/young-people-and-neets-in-europe-first-findings-resume (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- European Union. Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union OJ C 326. 26 October 2012, pp. 47–390. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- European Commission. Council Recommendation on a Bridge to Jobs—Reinforcing the Youth Guarantee and Replacing Council Recommendation of 22 April 2013 on establishing a Youth Guarantee. OJ C 372. 4 November 2020, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.C_.2020.372.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Quintano, C.; Mazzocchi, P.; Rocca, A. The determinants of Italian NEETs and the effects of the economic crisis. Genus 2018, 74, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floro, C.; Ciociano, E.; Destefanis, S. Youth Labour-Market Performance, Institutions and Vet Systems: A Cross-Country Analysis. Ital. Econ. J. A Contin. Riv. Ital. Degli Econ. G Degli Econ. 2017, 3, 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Floro, C.; Rocca, A.; Mazzocchi, P.; Quintano, C. Being NEET in Europe Before and After the Economic Crisis: An Analysis of the Micro and Macro Determinants. Soc. Indic. Res. Int. Interdiscip. J. Qual.—Life Meas. 2020, 149, 991–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus, Z.; Biavaschi, C.; Eichhorst, W.; Giulietti, C.; Kendzia, M.J.; Muravyev, A.; Pieters, J.; Rodríguez-Planas, N.; Schmidl, R. Youth Unemployment and Vocational Training. Found. Trends Microecon. 2013, 9, 1–157. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, F. How to involve rural NEET youths in agriculture? Highlights of an untold story. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikala, S. Agency among young people in marginalised positions: Towards a better understanding of mental health problems. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 23, 1022–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherini, M. Origins and future of the concept of NEETs in the European policy agenda. In Youth Labor in Transition; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 503–529. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Statistics on Young People Neither in Employment Nor in Education or Training. Statistics on Young People Neither in Employment Nor in Education or Training—Statistics Explained. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Statistics_on_young_people_neither_in_employment_nor_in_education_or_training (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- OECD. Youth Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) (Indicator). 2020. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/youthinac/youth-not-in-employment-education-or-training-neet.htm (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Tanja, D. Youth Policy in Estonia: Addressing Challenges of Joined Up Working in the Context of Multilevel Governance. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tallinn, Tallinn, Estonia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Brien, R. Activation measures for young people in vulnerable situations. In Experience from the Ground; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poštrak, M.; Žalec, N.; Berc, G. Social Integration of Young Persons at Risk of Dropping out of the Education System: Results of the Slovenian Programme Project Learning for Young Adults. Revija Za Socijalnu Politiku 2020, 27, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, J.; Ilbery, B.; Maye, D.; Carey, J. Grassroots social innovations and food localisation: An investigation of the Local Food programme in England. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, K.; Eva, K.; Reiner, K.; Die Zukunft der Dörfer. Zwischen Stabilität und Demografischem Niedergang. 2011. Available online: http://www.berlin-institut.org/?id=833 (accessed on 14 June 2012).

- Neumeier, S. Why do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research?—Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heike, P.; Pollerman, K. ‘ILE und LEADER’. In Halbzeitbewertung des EPLR M-V; Grajewski, R., Forstner, B., Bormann, K., Horlitz, T., Eds.; Braunschweig: Hamburg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargan, L.; Shucksmith, M. Leader and Innovation. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, N.; Pereira, J.; Moreira, A.C.; De Matos, N. Exploring the meaning of social innovation: A categorisation scheme based on the level of policy intervention, profit orientation and geographical scale. Innovation 2019, 21, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.K.G.; Roelvink, G. An Economic Ethics for the Anthropocene. Antipode 2010, 41, 320–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmańska-Maruszak, A.; Sudolska, A. Social Innovations in Companies and in Social Economy Enterprises. Comp. Econ. Res. 2016, 19, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzini, E. Making Things Happen: Social Innovation and Design. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkeviciene, E. Social innovation in rural communities: Methodological framework and empirical evidence. Soc. Sci./Soc. Moksl. 2009, 1, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Laura, P. Unemployment and Social Exclusion; Discussion Paper No. 18-029; Centre for European Economic Research: Mannheim, Germany, 2018; Available online: http://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/dp/dp18029.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Batty, M. The New Science of Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, C.; Wyn, J. Young People Making It Work: Continuity and Change in Rural Places; Melbourne University Publishing: Carlton, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).