Abstract

Newer strains of tourism research are often aimed at finding out good practices for dealing with overtourism and propose a broader understanding of stakeholders of sustainable tourism development. Drawing on qualitative empirical findings from two institutions located in major tourism hubs in Poland, the authors inquire to what extent negative impacts of overtourism can be mitigated by museums. As the findings indicate, museums provide the commercial sector with good examples of conservation and adaptation of historic buildings to contemporary functions and encourage environmentally friendly behaviors. They can contribute to the quality of heritage narration and the quality of merchandise offered to tourists. They may have an impact on community cohesion and local residents’ quality of life as well as encourage immaterial heritage practices. Lastly, museums may exert indirect impact on transformations of urban space by getting involved in strategic planning and discussions on contemporary challenges of urban development.

1. Introduction

Although the issue of the costs and benefits of tourism has long been present in research on tourism [1,2,3], in the last decade, the debate on the impacts of tourism has become much more heated and focused on the problems created by tourism traffic concentrated in selected areas, municipalities, and regions [4,5,6]. Different strains of this discourse focus on the issue of the causes, factors, and determinants of overtourism [7] and the diagnosis of its negative impacts from an economic, environmental, social, or cultural point of view [3,8,9,10,11]. In recent years, other directions of research have also emerged, moving forward from the description of impacts to searching for effective solutions to problems caused by overtourism [11,12,13,14,15] and looking for key actors who can implement them [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

The article aims to contribute to the above research by looking at how museums, which often function as key tourism attractions [23,24] in urban destinations, may become important stakeholders with a potential to mitigate the negative impacts of tourism. To the best knowledge of the authors, the issue of museums’ potential to cope with the problems of overtourism has been noticed in the literature only very recently, mainly in manuals produced by international organizations [25]. The authors therefore treat the current article as an exploratory study, which could inspire further investigation of the issue in different spatial, geographic, and cultural contexts. Their intention is to make a contribution both to the discourse on the role of museums in the contemporary society and to the debate on overtourism.

The structure of the text is as follows. First, the issue of overtourism and possible strategies to deal with it is introduced. The next section focuses on museums, as enablers, beneficiaries, or victims, and institutions that can help cities cope with overtourism. The fourth part presents the research methodology and introduces two Polish museums that serve as an illustration of museums’ potential with respect to dealing with overtourism. It is followed by an empirical section devoted to the analysis of particular museum activities. The final part of the text presents the discussion of results and suggestions with respect to limitations and possibilities for future research.

2. The Concept of Overtourism, Its Stakeholders, and Measures to Deal with It

“Overtourism” is a recent popular buzzword in academic and policy-making discourse. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) [26] (p. 7), it is a new term for existing concepts such as tourism congestion management and tourism carrying capacity. The concepts of overtourism and the connected process of touristification were derived from the observation of rapid changes in urban spaces, functions, and meaning of the urban environment as well as residents’ (often strongly negative) reactions to tourism observed in the last few decades in many municipalities all over the world [4,8,9,10,27,28,29,30].

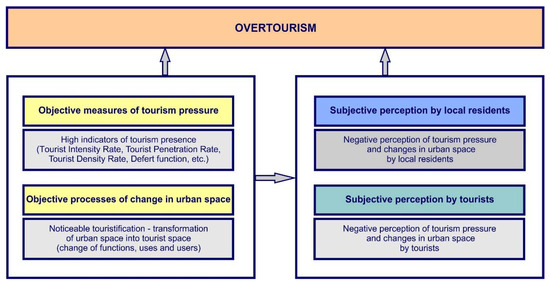

The existing definitions usually include references to three issues. First of all, overtourism is understood as a situation whereby a given destination is visited by ever-growing, disproportionately large numbers of tourists in relation to its carrying capacity, both assessed objectively looking at certain indicators and subjectively when it is perceived as overcrowded [13] (Figure 1). Measures which have been developed to show tourism pressure in specific locations and to picture its changes from a longitudinal perspective include: the average number of tourists in the city per day (Tourist Intensity Rate) and per 100 inhabitants (Tourist Penetration Rate), the number of tourists in the city per day and per 1 km2 (Tourist Density Rate), the number of beds per 100 inhabitants (the so-called Defert function), and the number of tourist beds per 1 km2 [13]. Second, the concept implies that excessive presence of tourists results in the decline of local residents’ quality of life, sense of place and well-being. Finally, many definitions notice that negative consequences of overtourism include the deterioration of the quality of tourist experience and well-being in an area [26]. For example, in a research report for the European Parliament [11] (p. 22), overtourism is understood as “the situation in which the impact of tourism, at certain times and in certain locations, exceeds physical, ecological, social, economic, psychological, and/or political capacity thresholds.” This echoes the definition of Goodwin [31] (p. 1), whereby “Overtourism describes destinations where hosts or guests, locals or visitors, feel that there are too many visitors and that the quality of life in the area or the quality of the experience has deteriorated unacceptably.” Accordingly, in some publications, both local residents and visitors are included among groups that suffer from the negative consequences of overtourism. In others the emphasis is put on the impact of excessive tourist presence on the local population [6].

Figure 1.

Objective and subjective dimensions of overtourism. Source: own elaboration based on references [6,11,13,20,26,27,28,31].

Overtourism is often analyzed in connection to two other related concepts. First of all, it is connected to the concept of tourism carrying capacity of a destination defined by the UNWTO [26], as “the maximum number of people that may visit a tourist destination at the same time, without causing destruction of the physical, economic, and sociocultural environment and an unacceptable decrease in the quality of visitors’ satisfaction” (p. 5). Second, overtourism can be understood as a result or an outcome of the process of touristification described as “a process that encompasses displacement as well as other material and symbolic consequences stemming from mass tourism on a given territory … Touristification contributes to a loss of authenticity in these spaces by the socio-spatial transformation of neighbourhoods in line with the needs of consumers with high purchasing power” [29] (p. 5). Touristification (and overtourism as its implied effect) is also seen as the outcome of recent neoliberal policies and is linked with but not synonymous with tourism gentrification processes, as “a complete transformation of the urban space into tourist space” and ”a multifaceted process of urban change promoted by both local and transnational actors and closely related to the improving tourism competitiveness and capacity for attracting visitors” [28] (p. 4). Overtourism may thus be understood as a state of affairs whereby, due to the process of touristification, tourist uses of urban space and urban resources become so dominant and intensive that they exceed an area’s carrying capacity and are negatively perceived both by residents and by tourists (Figure 1).

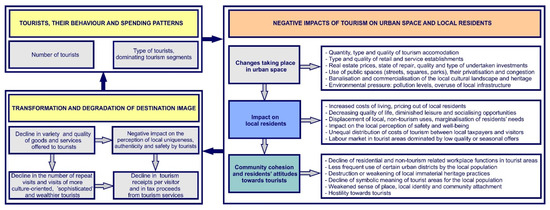

Researchers are in agreement with respect to main drivers of overtourism [7,11,13,15,28]. Rapid, continuous, world-wide growth of the tourism sector, especially international tourism arrivals and development of new tourism segments such as the outbound tourism from East Asia, is the first of these drivers. Improved accessibility and affordability of travel, especially by air, is the second. Next, technological changes in the provision of information and booking tourism services are often mentioned. They have led to the expansion of unregulated tourism accommodation and unlicensed transport and guiding services. Digital media are also key enablers of excessive promotion of selected sites. Other factors include proximity to sites with major heritage and tourism labels such the World Heritage status [11] and growing tourism congestion in regions perceived as safe and stable or relatively uncrowded [13]. In addition, in times of frequent instability in the financial markets, tourist real estate might appear as a safe and profitable investment [28]. Finally, local authorities in particular destinations might be reluctant to limit tourist numbers due to short-term visions of development and pressure of stakeholders who are stronger politically and economically and fail to foresee the negative impact of new major investments and attractions or do not realize that marketing efforts focused on tourism growth do not necessarily translate into sustainable tourism development. They neither control tourist numbers and the spread of tourism services nor have full knowledge on the tourism market [15]. Taking the above into account, overtourism may be conceptualized as a situation whereby both tourism indicators linked with tourist numbers, clustering and density in an area in comparison to its size, population or other economic activities, and a wide-spread perception of tourists’ presence in it indicate that positive impacts and benefits of tourism are overshadowed or outweighed by negative consequences and costs of its development (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The vicious circle of overtourism as the outcome of interrelated factors, causes and negative tourism impacts. Source: own elaboration based on references [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,19,32].

As indicated in Figure 2, problems generated by tourism are usually related to the excessive number of tourists in comparison to local residents and customers in an area, type of tourists attracted to a given place and their spending and behavior patterns (e.g., day-trippers rather than overnight visitors, budget and nightlife-oriented tourists rather than cultural tourists, certain types of organized tourist groups) [4]. Tourism-related changes taking place in urban spaces impact local residents’ purchasing power, their quality of life, their attitudes toward tourists, their community attachment, and their identification with local heritage [1].

Some of the most visible consequences of excessive tourism are functional changes linked with the ownership, quantity, type, and quality of tourism accommodation in an area and the construction of new buildings or conversion of historic buildings into hotels, hostels, and apartments for tourists [8]. At the same time, due to tourist pressure, the type and quality of retail and service establishments changes, which leads to crowding out shops and services principally used by residents by those catering mainly to tourists such as bars and restaurants, souvenir shops and other commercial tourist attractions ranging from low quality displays of various artifacts to illegal gambling and pimping [4,8,10]. The conversion of a former residential or multifunctional space [10] into a tourism space is often accompanied by rising real estate prices [1,4] and influences the type and quality of undertaken restoration and new construction projects as it tends to favor those that lead to the aestheticization and Disneyfication of urban space or maximization of commercial surfaces at the expense of continuity of functions, maintenance of historic features, and authentic built tissue or green spaces [11,19]. Large numbers of tourists in public spaces lead to their overcrowding, thus decreasing the comfort and enjoyment of specific cultural surroundings [1,4,10,11]. They also stimulate the privatization of public space and its “takeover” by tourist-oriented establishments [4,8]. A related issue is the frequently observed homogenization, banalization, and commercialization of the cultural landscape [1,8,11]. Another problem is simplification or selective interpretation of heritage focused on generating profits [8]. Finally, an area that experiences overtourism often faces environmental pressures—overuse of infrastructure and additional air and water pollution, noise, or waste [4,10,11,19].

The above changes have a profound impact on local residents. Decreased availability of residential spaces and increased costs of living [1,8,19] coupled with declining quality of life and worse access to basic services displace many residents from tourist areas and transform them into monofunctional tourism enclaves [2,9,10,11]. An additional problem from the perspective of locals is the changed perception of particular areas as less safe or good for socialising and leisure [10,11,19]. What exacerbates the problem is the unequal distribution of benefits and costs of tourism [2,11]. Residents who provide tourist services or rent premises to tourist uses profit from increased tourist traffic. Those who have no links with the tourism sector as local taxpayers pay the costs of infrastructure or services from which tourists benefit. Congestion and monofunctionalisation caused by tourism also diminish non-tourism related work opportunities, making the labour market in tourism areas less sophisticated and seasonal as it offers mainly service-related, low-paid jobs and temporary employment [11]. While specific touristified quarters lose permanent residents and non-tourism-related economic activities, residents of other parts of the city are also less likely to visit such areas [11]. This may lead to the destruction or weakening of immaterial heritage practices [9], the decline of symbolic meaning of most culturally valuable historic sites for local residents, and a weakened sense of place, identity, and attachment to the city [8,9,10]. Finally, disadvantages caused by the presence of tourists may cause visible, local hostility toward tourists as those responsible for the economic, functional, and symbolic takeover of the city [9,11].

Not all tourists are beneficiaries of tourism-oriented changes in touristified areas, either [10]. What makes places attractive to tourists is often their specific ambiance, diversity of functions, uniqueness of local offers and cultural expressions, and the presence of local residents. In areas where tourists dominate, a decline in the variety and quality of goods and services offered to tourists is often observed. This may lead to negative experiences of tourists and a negative perception of certain areas as inauthentic, monofunctional and unsafe [11]. In the long term this leads to the degradation of a destination’s image. A preponderance of low quality offers—such as quasi-museums or fast-food establishments that do not count on repeat visits; shops with low quality, non-locally made souvenirs; and psychological stress caused by overcrowding—may discourage repeat, culture-oriented, and wealthier tourists [8,19]. Their withdrawal from an area might in turn cause a decline in tourism receipts per visitor. As a consequence, the number of short stays and day trippers who spend less time and money in a destination and who are likely to visit only a few selected areas and contribute to their congestion will continue to increase. Establishments catering to more sophisticated tourists may leave the area as the majority of mass tourists favor low-cost catering and accommodation options, which are frequently linked with low or lack of tax receipts. Increased numbers of tourists who come to a city thanks to its image as an inexpensive and trendy destination will also make it more likely that certain segments of tourists will start to dominate (e.g., organized tourist groups who spend only a few hours in a given city following a standard tourist route, tourists on stag party and hen party trips, night life–oriented tourists, etc.) [26,30].

In the context of a municipality tourism stakeholders [33] may be conceptualized as “individuals, groups or organisations with a shared interest in an issue or problem” [34] (p. 9) and in particular “all parties interested in or affected by tourism development” [19] (p. 467). Tourist destinations have diverse, multiple stakeholders representing the public, commercial, and non-governmental sectors [16,17,18,19,32,34,35,36]. Some of them are firmly embedded in particular destinations (local), while others are loosely linked with or external to them (non-local). It is often stressed that sustainable tourism development should involve the support and inclusion of all relevant stakeholders in the discussion, development, and implementation of strategies for a destination [19]. At the same time, the issue of complex relationships between them should be taken into account. In the context of art cities, it is also valid to take into account that they may have strikingly different attitudes, needs, and practical possibilities to influence the way heritage is used for contemporary purposes [37]. Some of them may play a strategic role as stewards and brokers who negotiate between different parties: “mediating, interpreting and controlling heritage and tourism which looks beyond the host-guest, tourist-local interaction and economic consumer-producer relationship” [16] (p. 120).

The need to deal with overtourism has recently been recognized as an important policy issue by decision and policy makers on both local and higher governance and cooperation levels all over the world [11,26,38,39]. Moreover, recent publications and policy reports do not only diagnose overtourism as a problem but also suggest possible strategies and measures to cope with it [39]. Possible policy responses include economic, heritage-related, and environmental measures; (de)marketing; organizational measures linked with restrictions on, dispersal, and diversification of tourism offer; and, last but not least, resident-oriented measures (Table 1). It is also stressed that overtourism strategies should not be isolated but form a part of a broader urban agenda and involve all relevant stakeholders who could tackle overtourism at the local level [14,26]. In addition, it is necessary to recognize that congestion and destination overuse are a complex matter that is also related to the overuse of resources, infrastructure, or facilities in certain parts of cities by residents of other areas, commuters from nearby municipalities, university students, or migrant workers.

Table 1.

Measures and solutions linked with overtourism.

3. Museums in the Context of Overtourism

The traditional functions of museums include collecting, researching, conserving, and displaying artifacts, disseminating knowledge, and educating the general public. Recent decades have brought about recognition of additional museum functions such as bringing prestige to an area, museums’ role in defining and transmitting local and regional identity, or their function as spaces of leisure and social encounters [44,45]. Museum institutions are seen as agents of social inclusion [46], enhancers of health and well-being, facilitators of different types of social capital, and stimulators of creativity [47]. They are considered useful in attracting new functions, visitors, and customers. Apart from easily noticeable provision of educational or tourism services, many new arenas in which museums may engage are now proposed. These include the involvement of museums in the creation of local development strategies, spatial planning and sustainable urban design, facilitation of social participation [48], raising environmental awareness [49], cooperation with universities, artists and the creative sector, and broader involvement in the tourism, creative, and experience economies [25]. Museums may also perform more complex social functions as initiators and places of debates on important ethical, societal, and communal issues [50,51] or providers of services reaching out to the general public beyond the museum’s walls [52].

Museums have long been considered important tourism attractions [2,24]. They have therefore usually been understood as key elements of the tourist city [23] and a frequent part of the tourism experience [43]. Although museums represent rather traditional cultural attractions that focus mainly on the past, they are among most often visited cultural attractions on tourist trips [2,24]. It is also worth noting that most museums engage in presentation of contemporary art, recently produced objects, and new readings of the past or commentaries on present-day phenomena. As such, they serve as important discussion forums on contemporary society and culture. On the one hand, museums may be considered main beneficiaries and causes of overtourism. They do so both by the virtue of storing and displaying the most spectacular and valuable artifacts for a given area or thanks to unique venues they are based in. As such they contribute to overtourism indirectly as tourist venues, architectural icons and important parts of an attractive image of a tourism destination [40,53]. Museums may therefore be critiqued for stimulating overtourism—in particular, the congestion of tourists in specific areas and catering mainly to tourists though their day-to-day functioning is often determined by local subsidies and grants. As museums become more tourist-oriented, they may also become over-reliant on receipts from tourists and attracting visitors to blockbuster exhibitions on popular topics or less complex presentations of most popular aspects of heritage [54]. This can lead to the marginalization of more locally oriented museum activities and themes with less commercial appeal. Local visitors may also find themselves in direct competition with tourists or start perceiving museums mainly as tourist attractions. On the other hand, museums are often considered the type of tourism attractions which prolong tourists’ stay and therefore enable beneficial economic externalities. Income from tickets may subsidize more locally oriented museum projects. Museums may also make external visitors more sensitive to the complexity and uniqueness of local culture and heritage. Finally, in some cases, museums become victims of overtourism. This is due to conservation threats posed to heritage sites by excessive tourist numbers and to the rising costs of accommodating tourists not fully covered by tourism receipts. Congestion and decline in the quality of tourist experience in a museum is a related issue [55]. Moreover, in places that suffer from overtourism, museums often find themselves in direct competition with commercial quasi-museum establishments and exhibitions that present attractive but shallow interpretations of local heritage. Finally, as non-profit institutions, museums may be expected to counteract some of the negative impacts of tourism as organizations focused on the long-term conservation and preservation of heritage.

4. Gaps in Existing Research and Research Questions

Despite the prominent role of museums in stimulating tourism traffic and their often emphasized potential roles in local development [25], museums have scarcely been mentioned in the existing debates on overtourism. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explicitly links the issue of overtourism with museums. This paper thus aims to fill in an important gap in the existing literature by taking an in-depth look at museums as important stakeholders of (over)tourism development and their roles in mitigating the negative effects of overtourism. As such, it seeks to respond to the broader call for a deeper engagement of researchers in direct interactions with particular tourism stakeholders in order to offer a more nuanced and comprehensive analysis of their roles in tourism development [10]. It is also in line with the need to study resilience [39] and search for mediators of conflicts in urban space [21,22]. Taking the above into account, the following main research questions were posed:

- In what activities linked with mitigation of overtourism do museums engage?

- What problems and challenges linked with overtourism may museums contribute to solve?

- What good practices linked with coping with overtourism may be identified in the Polish context, and are these good practices transferrable to other geographical settings?

5. Case Studies, Sources of Data, and Methodology

Poland seems to be a good terrain of such an investigation. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, and in particular since Poland’s accession to the EU, tourism traffic to and within Poland has been growing intensively, especially in major Polish cities and tourism destinations [56]. The issue of overtourism has only recently captured greater attention of the media, policy makers, and academics [32,42]. It is still considered an under-researched problem in the Polish context. So far, references to foreign experiences and diagnoses of the problem tend to dominate, rather than studies of particular stakeholders of overtourism. Publications on the roles of destination management organizations in dealing with overtourism are an exception [32]. At the same time, a debate on the role of museums in contemporary society has been initiated in the Polish context [57,58,59]. It includes the topic of museums as partners who cooperate with municipal authorities on diverse issues linked with local development [60].

This exploratory paper is based on the case studies of two museums that function in two major Polish tourism destinations—Krakow and Zakopane (Table 2). They represent different urban settlement types under threat of overtourism: a major historic city and a medium-sized spa town (which is a major tourist base for the surrounding region). In both cases, the analyzed institutions are key cultural tourism attractions and key bodies with a potential to shape the narration on the heritage and culture of their respective urban locations.

Table 2.

Selected data on Krakow and Zakopane in the context of tourism (over)development in the two cities.

Krakow is the second largest Polish city in terms of population as well as economic and cultural significance. The city’s rich, multi-layered cultural heritage and attractive image as the cultural capital of Poland have made it one of the most popular urban destinations in Europe (it received 13.5 million tourists in 2018) [61]. Although the city has always been recognized as an important tourist attraction in the Polish context, and the number of visitors has increased steadily since 1989, it has witnessed a rapid increase in tourist numbers since 2004. This phenomenon has been primarily attributed to two factors—Poland’s membership in the EU and the launching of low-cost flights to Krakow. Interest in the city is also stimulated by two internationally recognized cultural labels (Krakow is home to a UNESCO World Heritage site and is a UNESCO City of Literature) and its reputation as a well-known student and night life center. The Museum of Krakow is a municipal institution. Its activities and collections are linked with the diverse dimensions of the history and culture of Krakow. Its institutional structure comprises of 19 branches, a conservation unit, and a digitalization unit. The number of visitors to the museum has been growing steadily in recent years (1.3 million in 2017) due, at least in part, to the opening of two major tourism attractions (the “Schindler’s Factory” and “Main Square Underground” exhibitions).

Zakopane is a medium-sized town located in southern Poland at the foot of the Tatras, the highest and best-known Polish mountain range. The beauty of the mountains and valuable cultural heritage contribute to the tourist attractiveness of the town, wish is often referred to as the Polish winter capital [61]. Although there is no confirmed data on the number of tourists who visit Zakopane per year, it can be considered that the 3.9 million entry tickets to Tatra National Park sold in 2018 are a good proxy of visitors to the town. It developed as a spa and a tourist and artistic center in the 19th century. The Tatra Museum is a regional institution that manages rich natural, ethnographic, and art collections. The museum is the owner of diverse properties representing different architectural styles (including excellent examples of the so-called Zakopane style and unique vernacular buildings). It runs 11 branches in Zakopane and the surrounding vicinity. The number of visitors to the museum reached 200,000 in 2017.

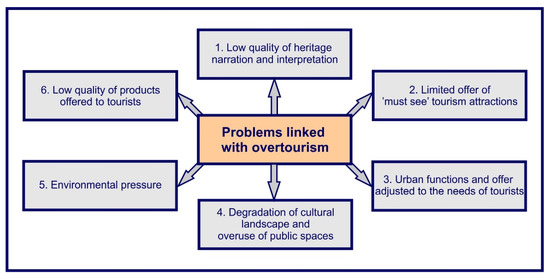

The growing interest in Krakow and Zakopane as leading tourism destinations in Poland has contributed to the generation of both positive and negative socio-economic and spatial phenomena in their urban space and has consequently generated a number of scientific studies on the subject [32,41,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. In publications on the two municipalities, six main problems resulting from overtourism are usually mentioned, which are in line with similar challenges discussed in the academic literature all over the world (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Problems linked with overtourism diagnosed in Krakow and Zakopane. Source: own elaboration based on references [32,41,63,64,65,66,68,69].

The analysis of museums’ involvement in coping with overtourism was done mainly on the basis of qualitative data obtained by the authors within the framework of a broader Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) project on “Culture and Local Development: Maximising the Impact” conducted in 2018 [25]. The topic of overtourism was not an explicit part of the OECD study. None the less, many of the questions asked during face-to-face interviews conducted in March to June 2018 for the purpose of the project revealed the complex roles played by museums in mitigating overtourism and were thus analyzed by the authors independently of the OECD report following its completion. The authors carried out 19 semi-structured interviews in Krakow, each lasting at least one hour, including 12 interviews with various staff members of the Museum of Krakow including the museum board of directors; members of the conservation, strategy, and marketing departments; heads of particular museum branches (IKR1–12); three interviews with representatives of municipal and regional authorities, including the head of the municipal culture department, municipal promotion department, and the head of culture department of the regional authorities (IKR13–15); and four interviews with other museum stakeholders (leaders of two non-governmental organizations involved in heritage promotion and protection, IKR16–17), a director of a public elementary school who cooperates with the museum (IKR18), and a local artist who rents shop space in a museum building (IKR19) (IKR denotes an interview which pertains to the Museum of Krakow, IZ an interview relevant for the museum in Zakopane). In Zakopane, a total of 11 semi-structured interviews, each lasting at least one hour were conducted; four were with the employees of the Tatra Museum in Zakopane (IZ1–4), three were with representatives of local and regional authorities (IZ5–7), and the remaining four were with other stakeholders (directors of two local schools (IZ8–9), the vice-director of the Tatra National Park (IZ10), and a local artist—a specialist in traditional highlander music and a teacher at a local cultural center (IZ11)). In 2019, the researchers contacted many of the interlocutors again to pose supplementary questions relevant to the topic. For the purpose of the article, the authors also collected supplementary statistical data such as museum reports to Statistics Poland and National Institute for Museums and Public Collections, relevant information available on-line, strategic documents provided by particular museums, and local governments. First-hand experience of each institution was also obtained via observation as participants in activities organized by the two museums.

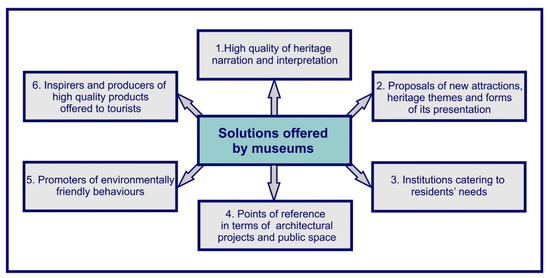

The authors applied the qualitative data analysis method suggested by J. W. Creswell and J. D. Creswell [76] to group the empirical data into six main theme groups. Each of them reflects the potential of museum institutions with respect to mitigation of a particular negative effect of overtourism in Krakow and Zakopane (Figure 4). Accordingly, the numbers that pertain to groups of museum activities in Figure 4 correspond with particular problems diagnosed in Krakow and Zakopane shown in Figure 3. At a later stage of data analysis, museum activities were further assessed taking into account additional criteria and dimensions such as form of impact (providing direct or indirect solutions to problems linked with overtourism) and activities conducted by museums independently or jointly with other stakeholders.

Figure 4.

Solutions to selected problems linked with overtourism diagnosed in Krakow and Zakopane offered by museums. Source: Own elaboration based on analysis of qualitative data.

6. Research Results: Museums and Mitigation of Negative Impacts of Tourism

6.1. High Quality of Heritage Narration and Interpretation

The deregulation of guiding services in Poland in 2014 resulted in a visible decrease in the quality of guiding, especially in urban centers with a large number of visitors. Currently, a much greater number of self-made guides, often without appropriate knowledge and skills, are very likely to provide tourists with scientifically doubtful and simplified information on Krakow and its heritage (IKR11, IKR3, IKR8). Although the situation in Zakopane is better as a license is still required to guide in the Tatra mountains, this problem to some extent also exists there. The issue was noticed by both museums. They have begun organizing their own courses, meetings, and lectures for guides and teachers who visit cities with school groups and often save on trip costs by refraining from hiring a professional guide. Museums see these new educational services as a way to ensure that guides and teachers have access to reliable information and specialist knowledge. The Museum of Krakow offers a year-round programme of courses and lectures for guides (IKR11). In 2010–2018 guiding certificates for the so-called “Memory Trail” (three museum branches focused on World War II) were obtained by 801 persons, and 809 persons obtained certificates for the “Main Square Underground” exhibition (IKR4, IKR5). In addition, the museum conducts specialist courses on specific themes, time periods, areas and on guiding skills (IKR4: “The quality of guides decreases parallel to the level of knowledge of our audiences … Education of guides is a never-ending process”). Examples of such initiatives include seminars entitled “Conversations on History and Memory” and the postgraduate program “Cracoviana—Tourism in Krakow and its Region” co-organized with the Pedagogical University of Krakow (IKR2, IKR11). The Tatra Museum also organizes training sessions for Tatra guides (IZ1). Training activities at museums are complemented by their offer of publications and study materials. They are available to tourists who want to explore the city on their own, too (IKR3, IZ4, IKR17).

6.2. Proposals of New Attractions, Heritage Themes, and Forms of Its Presentation

Museums have noticed that certain groups of tourists are less likely to visit cultural institutions. They stay in the city or a town for a very short period of time, or the main aim of their visit is skiing or hiking. In order to reach these groups with good quality information on local heritage, to make them sensitive to it, and spur their interest, museums prepare outdoor exhibitions and events. For example, during the Christmas and New Year season, the Museum of Krakow organizes an outdoor exhibition of the traditional Krakow Christmas cribs (IKZ9, IKZ11). Similarly, the Tatra Museum prepares exhibitions on local heritage displayed in public spaces in Zakopane, mainly in Krupówki street—the main pedestrian axis of the resort (IZ2). In 2019, “multimedia” benches were installed in Zakopane to remind people of the local history and famous artists connected to it. Sitting on such a bench, one can listen to recordings of music and literary texts from the museum collection or download further information using QR codes (IZ5). The Tatra Museum has also developed a special offer for hikers and skiers. It includes meetings with well-known climbers and explorers, presentations of historic mountain and skiing equipment, and film shows. Enthusiasts of hiking, climbing, and winter sports can also purchase books on related issues published by the museum and participate in promotional meetings linked with them (IZ2, IZ4).

Museums can enrich the offer for tourists by preparing a program of events or exhibitions that helps visitors become familiar with less known aspects of local culture. This may make visitors more aware of the richness and diversity of heritage in each of the cities and inspire dispersion of tourist traffic to less crowded areas. Museum institutions are likely to become initiators or co-creators of new heritage trails [77]. For instance, the museum in Zakopane was involved in the development of “The Trail of Zakopane Style of Architecture” and “The Trail of Outstanding Residents of Zakopane” in cooperation with local authorities and a local foundation (IZ2, IZ3, IZ5). A museum walk on “Zakopane—a city of modern art and architecture” in turn attracts attention to architectural details hidden under commercial advertisements. The Museum of Krakow also organizes educational walks on diverse topics such as nuclear shelters or green areas (IZ2).

6.3. Institutions Catering to Residents’ Needs

Museums undertake diverse effort linked with encouragement of local cultural consumption and provision of opportunities for encounters between local residents. In large cities such as Krakow, local museum branches can function as important community hubs and counterbalance the tourist orientation of the best-known venues. In both cases, museums serve as promoters, transmitters and reference centers for local immaterial heritage practices. Their initiatives engender a sense of place and a sense of pride among the local population (IZ1, IKR10, IKR18).

The Museum of Krakow is well aware of the need to differentiate its offer between museum branches which have a clearly supralocal character and as major tourist attractions cater mainly to tourists and district branches that are more focused on cooperation with local communities and associations (IKR9: “There has been a dramatic change of the roles played by the museum … it is not only that there’s so much more happening but also our attitude to the mission of the museum has changed completely. We are most of all a meeting place for the local community, whose members also co-create our offer”). Such cooperation includes crowdsourcing of artifacts and knowledge, functioning as spaces of meetings, and participatory activities that encourage residents to share their ideas and memories (IKR6, IKR7). Local branches often deal with specific local problems (IKR18: “Children in Nowa Huta grow up conscious that their district is a bad area. This is what adults tell them and this is how they see the world later on. That nothing will ever change here. By joining forces with the museum, we do our best to break this stereotype”; IKR7: “From time to time, apart from museum events, people simply come to me and chat, they tell me what happens in the area. And I listen to them, react, try to help whenever it is possible. I call it a ‘museum couch’”). Even the more tourist-oriented branches prepare a specific offer for locals, for example within the framework of the “Winter Vacation in the City” program for children and “Museomania”—an annual series of events organized during the school year (IKR4). The museum has also developed an original art performance on Krakow’s history entitled “The Guardians of the Magic Book” addressed to kindergartens and schools (IKR11).

In 2018, local authorities in Krakow introduced a new “Krakow Card” for residents and local taxpayers. Its holders can purchase public transport tickets as well as tickets to museums and other venues at a significant discount (IKR13, IKR14). The museum also participated in a comprehensive audience research project conducted jointly by various cultural institutions in Krakow in order to learn about visiting patterns and preferences of local cultural consumers (IKR11, IKR2) [78].

The Tatra Museum organizes numerous projects to familiarize the local community with the history of the Podhale region (IZ5). It is involved in diverse initiatives focused on commemorating famous inhabitants and visitors to the resort and specific communities, minorities, and social groups linked to the area. Such activities often require cooperation between the museum and local associations or activists and result in exhibitions, special events, or offers for residents and result in publications on unknown or forgotten aspects of local history (IZ2, IZ4). The directors of local schools emphasize that the museum is an important source of expert knowledge on local culture both for children from highlander families deeply rooted in the area who are under pressure of mass culture and for children from “migrant” (non-highlander) families (IZ8, IZ9: “Showing the value of highlander culture, its pure version without influences of mass culture. The original ‘highlanderness’ is in danger of extinction. We strive to reverse this trend and the activities of the museum help us a lot in this”). The museum is also engaged in a cultural education program initiated by the local government with the aim to stimulate cultural consumption (“A Cool-tured Man”) (IZ5, IZ7).

In cooperation with other local institutions such as the Tatra National Park, the Witkiewicz Theatre, or the mountain shelters in the Tatras, the museum organizes quaint meetings mainly for local residents. They consist of lectures or workshops coupled with performances and give residents an opportunity to socialize over tea or while dancing. For example, in 2019, a series of events entitled “Evening Meetings in the Mountains” featured lectures on local history and live concerts of highlander music in mountain shelters (IZ1, IZ10). The annual festival “Tatrzańskie Musealia” in turn concludes with an informal meeting reminiscent of the local tradition of highlander evenings called “Posiady.” A project on Christmas carol singing evenings conducted by local musicians proposed in the regional participatory budget is another interesting initiative (IZ1, IZ2).

Excessive numbers of tourists may discourage local immaterial heritage practices or inspire their commercialization and banalization (IZ8). Museums can counteract both trends by providing opportunities to residents and tourists to learn about uniqueness of local immaterial heritage and acquire skills necessary for its creative continuation. The Museum of Krakow is the key local stakeholder in terms of looking after important local traditions (IKR16: “The Museum of Krakow is the leader of museological revolution in Poland. It has managed to bring out and stimulate local and district identity”). The museum is the main organizer of the traditional “Zwierzyniec pony” pageant inscribed on the national list of immaterial heritage (IKR12, IKR9, IKR1). Krakow nativity scene (szopka) making has been a traditional local handicraft since the 19th century. The Museum of Krakow was the leader behind Krakow’s success in getting the “nativity scene tradition” inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. It organizes the famous, annual crib competition followed by an exhibition of all contest entries much appreciated by local residents (IKR12, IKR9). The museum documents the process of crib-making and acquires most beautiful cribs for its collection but also organizes crib-making courses and workshops. Such museum activities generate intergenerational links between different age groups and the crib makers milieu and between the museum, local residents, and educational institutions (IKR11).

Similarly, the Tatra Museum conducts numerous activities that link its collections and immaterial heritage by providing access to its collections to local artisans and artists, exhibitions, workshops, demonstrations of local crafts, and publications (IZ11: “As a young man I used to sit in the [museum] archive for hours, looking through archival materials on local culture. No other institution boasts such a collection of original historical [music] sources. My students today know it very well”). A good example of such efforts is the museum’s digitalization project focused on original, early 20th century archival recordings of highlander music and dialect (IZ1). Traditional highlander music is still relatively popular in the area both due to tourism demand and community attachment. Such projects can contribute to the quality of commercial performances for tourists and to transmission of music skills to younger generations (IZ11: “Thanks to this project we are able to recreate the original pace, tone, colour of local music. We were not aware to what extent in the past hundred years we have distanced ourselves from the original”; IZ1: “The community of local musicians has responded to the project enthusiastically. It was like a big feast of local folk music”). The latest project of the museum focused on intangible heritage is the so-called “Tatra Phonotheque” and the Zakopane Centre for the Documentation of Intangible Heritage (IZ2).

6.4. Points of Reference in Terms of Architectural Projects and Public Space

Both museum institutions own or manage valuable, listed historic buildings, often strategically located in the very city or town center. Some of them are considered significant local landmarks. Comprehensive conservation and adaptation activities undertaken by museums, in line with highest conservation standards and careful day-to-day maintenance of historic properties may serve as a point of reference to private heritage owners and investors. This is proof that proper conservation activities can enhance the value of historic properties bringing out their unique qualities and lead to better fulfilment of contemporary functions (IZ11, IKR12, IZ3, IZ6, IKR15).

Polish museums are also increasingly aware of their potential role as inspirers and providers of well-designed outdoor leisure spaces for the local public. For example, the Nowa Huta branch of the Museum of Krakow has plans to adapt the building’s roof as an open public space with a café and a summer cinema (IKR7). The Podgórze branch was first to notice the potential of an abandoned strip of land underneath the railroad junction and alongside the railroad line next to museum grounds (IKR6). The museum employees organized a voluntary clean-up action focused on this disused piece of land, proposed to redevelop it as a linear park between two museum branches located in this part of Krakow and entered into cooperation with the Krakow Polytechnic and a local association in order to work on its innovative design. As a partner of a local foundation, the Podgórze branch is also an organizer and a venue of public hearings on ideas for the development of green public spaces in the area. Similarly, all of the current extensive renovation and redevelopment projects conducted in the buildings of the Tatra Museum (seven out of 11 venues) take into account the need to redesign their green surroundings to create more friendly leisure spaces (IZ1, IZ, IZ3, IZ11: “Knowing the museum, one may be almost certain that the current restoration projects will result in unique outcomes, show the potential of historic buildings and set a good example of contemporary adaptations of historic pieces of architecture. Taking into account what happens in our town in this respect—setting good benchmarks is what the town urgently needs”).

Museums’ impact on changes taking place in urban space and with respect to local heritage and local residents’ needs can also be indirect and may be linked with their involvement in strategic planning: the elaboration of local strategic documents, development of local heritage protection strategies and measures in cooperation with local authorities and conservation authorities or engagement in discussions on challenges of urban development (IKR6, IKR10, IZ1, IZ2). The latter includes organization and provision of relevant discussion fora [77]. For example, employees of the Museum of Krakow take part in the formulation of recommendations on strategic documents for the entire city or pertaining to quarters and areas in the vicinity of its branches. They also participate in the elaboration of specialist municipal strategies concerning heritage protection, urban greenery, transport infrastructure, and tourism development or urban regeneration. The so-called “Cultural Park” is one of four monument protection forms foreseen by Polish heritage protection law. It is intended as a special measure for areas with particularly valuable cultural landscapes. The museum was one of the key partners of the local government in Krakow in the elaboration of the guidelines for the “Old Town Cultural Park” established by the local authorities in 2010. The Museum of Krakow also provides expert support to the local government in the form of opinions on the conservation and adaptation of historic buildings (IKR10). Another example of such cooperation is the development of plans for the commemoration project on the grounds of the former Plaszow Concentration Camp and organization of consultation sessions with local residents who live in its vicinity (IKR6). Similarly, although as a non-municipal institution to a slightly smaller extent, the Tatra Museum cooperates with the local government by taking part in consultations, discussions, and specialist commissions of the Town Council on culture and cultural landscape. For instance, it was actively involved in the development of the “Krupówki Cultural Park” (IZ2).

The Museum of Krakow has also become an initiator of discussions on important urban challenges. The museum has organized a series of debates on significant issues linked with the city’s past and present entitled the “Krakow Colloquy” (IKR8, IKR7: “These are difficult topics. The role of the museum is to be a place of toned-down dialogue”). The museum initiates meetings of civic leaders and urban activists or invites non-governmental organizations to conduct them (IKR16). In 2019, the museum’s innovative exhibition project “Przemieszczanie” linked the past and the present of diverse areas of the city and diverse social groups who reside in it. It made clear references to the problem of depopulation and displacement of residents from historic quarters. The museum is very active in initiating discussions on the role of museums in contemporary cities (e.g., a lecture series entitled “A Museum in the City: the City at the Museum,” a conference on “The City–Museum–Urban Residents: Museum and the Challenges of Contemporary Cities” in 2019, and a conference entitled “You Have the Right to the City“ planned in 2020) (IKR2). The Tatra Museum also organizes or participates in conferences on urban development and the challenges of tourism development, especially in the context of protection of natural and cultural resources. It cooperates on this topic with the Tatra Chamber of Commerce and the Tatra National Park (IZ1, IZ2, IZ7). Recently, apart from co-organization of a conference on “Culture and Nature,” it also organized a debate session for young people from Zakopane to contrast arguments of environmentalists and investors.

6.5. Promoters of Environmentally Friendly Behaviors

Although nature protection and the natural environment are not the focal themes of the two museums, they undertake numerous activities that link their collections or local heritage with promotion of environmentally friendly behaviors and a healthy lifestyle. The Museum of Krakow is the first museum institution in Poland that explicitly promotes visiting its branches by bicycle (IKR10). Its “Museum on a Bike” program encourages visitors to follow one of the three proposed bike trails between museum branches and collect stamps that entitle cyclists to discounts on further admissions and free-of-charge entrances. The museum is also the organizer of the annual “Remember with Us” memorial run (IKR4). In 2019, apart from a sports competition, the event included lectures, workshops, educational walks, and artistic performances. It was accompanied by the collection of money for the victims of the civil war in Yemen in cooperation with the Polish Humanitarian Action and a mobile blood collection session in cooperation with the regional blood collection center.

The location of the Tatra Museum in Zakopane, next to a particularly valuable and spectacular natural mountain area in Poland, makes its engagement with ecological issues both desirable and unavoidable (IZ10, IZ1). The museum organizes events on the natural resources of Podhale region such as lectures and workshops on the behavior and customs of birds or the sounds of Tatra fauna. The Centre for the Promotion and Protection of Peatlands in Chochołów (a village near Zakopane) is a recent partner of the museum. Their cooperation resulted in an exhibition on the uniqueness of fauna from the Podhale region on display at the Centre. The Tatra Museum also tries to encourage environmentally friendly travelling behaviors. It participates in a regional authorities’ program “A Train to Culture” meant to encourage rail travel and cultural participation by providing discounts on admission to cultural institutions to passengers of regional railways. The museum in Zakopane combines efforts to promote its collections and promotion of sports. Since 2018, in a partnership with the Municipal Centre for Sports and Recreation, it has organized the annual run which commemorates Władysław Hasior, a famous avant-garde 20th-century artist who lived in Zakopane and was also a talented runner. One of the museum branches is dedicated to him. The route of the run therefore connects the Tatra National Park with this branch where numerous accompanying attractions and leisure opportunities are provided. The museum is also engaged in efforts aimed at raising awareness of safety requirements and procedures in the mountains (e.g., as an organizer of free-of-charge training sessions) (IZ2).

6.6. Inspirers and Producers of High-Quality Products Offered to Tourists

Both museums notice the problem of poor quality of souvenirs sold to tourists (IKR2, IKR11, IKR8, IZ1, IZ4). In order to deal with this issue, three main types of activities are undertaken. Museums initiate cooperation with souvenir designers and producers to inspire them to refer to local heritage and stimulate the creation of unique products that are manufactured locally. Both institutions also commission the design and production of some souvenirs or serve as their places of sale. They publish books and other items (IKR15, IKR2) that can serve as souvenirs. Museum shops or shops in museum buildings are points of sale of unique artisanal objects or artworks and the publications of local authors (IKR11). For example, a branch of the Museum of Krakow rents space to a local historical crime writer for his unique “historical shop” (IKR19: “Kacper Ryx is a brand … the museum does care who rents here, our profile suits them very well … we support each other … museum visitors pass through our shop, it would however make no sense to be here if we had to pay market rent”).

Although the museum in Zakopane is much smaller than its Krakow counterpart, the Tatra Museum has also been involved in setting a good example in terms of its souvenir and publication offerings, the latter often prepared in cooperation with the Tatra National Park (IZ4, IZ10). A very interesting initiative of the Tatra Museum in 2019 was an open competition for the design of a good quality souvenir from Zakopane linked with local culture or nature (IZ1). As many as 293 projects were submitted. The first prize was granted for the design of a set of candles in the shape of three architecturally and historically valuable historic buildings in Zakopane. The name of the set (“Houses. Ghosts”) was inspired by the losses and threats linked with growing investment pressures in Zakopane. It is also worth mentioning that museum activities on traditional highlander culture such as clothing may be used by the commercial sector either as inspiration for contemporary fashion design or to enhance the ambiance of catering and hotel establishments.

7. Discussion of Research Results

Although the main mission and purpose of museums is to collect, preserve, research, and narrate heritage, their efforts linked with overtourism are often unavoidable and desirable, both as tourism attractions and as institutions serving local communities. Consequently, as evident from the empirical findings, Polish museums implement many measures and solutions proposed for dealing with overtourism (cf. Table 1). The direct impact of museums on coping with overtourism is mainly linked with their traditional functions, which seem all the more relevant in the context of tourism pressure. Their indirect involvement in the mitigation of the problems caused by overtourism in turn tends to be connected with the newer and more broadly defined tasks of museum institutions [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Form and character of museum activities linked with mitigating overtourism implemented by museums in Krakow and Zakopane.

Museums are most frequently and deeply involved in the implementation of heritage-related tasks, for example serve as points of reference of proper quality-built heritage maintenance, conservation, and adaptation to contemporary functions. They can also contribute to a broader awareness of local heritage, impact the quality of heritage narration, and encourage immaterial heritage practices. They are strongly engaged in measures linked with dispersal and diversification of tourism offer. They can perform the strategic role of heritage stewards and brokers [16] in cities suffering from overtourism. In both analyzed cases, residents are considered the most important long-term visitor group. Museums encourage local cultural consumption and repeat visits as well as resident participation in museum projects. They cooperate with individual residents, artists, and activists; local schools; other cultural institutions; nature protection institutions; and non-governmental organizations [77]. Both institutions often create opportunities and provide spaces for meetings, thus developing a sense of attachment to the museum and to the place of residence. Such museum activities show that museums have a significant potential to impact on social capital and residents’ quality of life in municipalities that experience overtourism, providing that they are aware of the need to strike a balance between offers for tourists and for locals [52].

As non-profit institutions, museums can have an impact on economic contexts in which they operate only to a limited extent, most often indirectly. None the less, some of their activities linked with discovering local heritage are connected with providing encouragement and support to local artists and artisans—small and microentrepreneurs who can contribute to the distinctiveness and authenticity of specific areas or provision of unique products and services, such as well-designed souvenirs. As such, they may set a good example in terms of the quality of the merchandise offered to tourists [35]. Museums are also involved in inspiring environmentally friendly behaviors and local policy development, especially with respect to heritage and tourism [49].

Particular stakeholder groups notice the potential of museums in dealing with overtourism to a different extent (Table 4). Museum staff members were rather unanimous in their answers. They tended to recognize museum impact in each of the distinguished areas. Differences of opinion between employees of the two institutions are very small (dimension 5) and may be explained by particular local contexts in which they operate (i.e., in Zakopane the enhanced role of the museum as the promoter of environmentally friendly behaviors is linked with its location nearby a famous natural park). Local authorities who are owners and direct supervisory bodies of a given museum (the case of the Museum of Krakow as a municipal museum) seem more prone to recognize its multidimensional roles in dealing with overtourism (in contrast to the Tatra museum as a regional institution), although, in general, public authorities are more likely to be aware of the traditional museum functions—in particular, their roles in catering to local residents and fostering local culture. The recognition of museum impact by other stakeholders might in turn depend on the size of the municipality and the presence of diverse cultural and educational institutions in it. Despite many activities, the impact of the Museum of Krakow might therefore be less noticeable due to the size of the city of Krakow and the variety of public sector stakeholders who manage heritage, such as universities and numerous other museums. In Zakopane, the Tatra Museum is the manager of key valuable heritage sites and the main museum in the local context. It is therefore recognized to a greater extent by other stakeholders as a major source of information on local heritage and a leading institution in terms of its interpretation.

Table 4.

The importance of museums in coping with overtourism according to different stakeholders.

Although in terms of limiting certain tourist functions, monitoring and encouraging ecological mobility, or providing green leisure areas, museums may play a visible role, they certainly should not attempt to nor are entitled to replace the responsibilities of local authorities in this field. Other potential solutions to overtourism are linked with competencies that in Poland are within the scope of control of central level public authorities (e.g., tax policies on tourism, licensing guides).

Apart from six main types of museum activities and initiatives discussed above, museums can fulfill an important advisory and educational role as expert institutions. Moreover, motions undertaken with respect to marketing museum institutions or, more broadly speaking, local heritage both internally (to local residents) and to tourists as well as potential tourists may likewise have an important impact on the overall image of a given destination. In addition, museums can contribute to the implementation of de-marketing policies, for example by introduction of more strict booking and guiding rules in museum venues, conduct (local) audience research or participate in and (in some cases) initiate discussions on contentious issues [46,50,51]. Museums may exert indirect impact on changes taking place in urban space by getting involved in strategic planning and discussions on urban development [25]. The extent to which local authorities benefit from this potential of museums, however, depends on the links and attitudes of local decision makers toward museums [60].

To paraphrase the argument of Boyd [43] (p. 221) about key principles in the development of (quality) heritage tourism, we can therefore say that, in the context of numerous threats posed by overtourism, museums can contribute to its mitigation by ensuring the authenticity and quality of heritage interpretation; providing a quality, creative, and learning environment that involves and invites local and non-local interactions; placing conservation of authentic objects and buildings at the core of their mission; and building cross-sectoral interactions and partnerships with other tourism stakeholders—in particular, local communities who are at the root of museums’ raison d’ětre. We can also consider museum activities from the point of view of negative impacts of overtourism such as distribution of tourists in an area, their activities, their behavior, the state of tourism infrastructure [4], and socio-cultural resilience to negative impacts of tourism [39], especially taking into account museums’ potential with respect to enhancing and building social capital [47].

Conversely, as stressed earlier on, museums should not be expected to become leading actors able to deal with all aspects of overtourism, either [31]. Apart from different core missions (e.g., in contrast to local authorities), museums still remain rather specialized institutions, which can impact the attitudes, knowledge, and behavior patterns of significant audiences, but only those persons who are attracted by different activities and marketing measures. What is more, from a professional angle, the museum offer should maintain its quality, be aesthetically and scientifically sound, provoke reflections, and educate. Although a museum visit or participation in museum activities might be an enjoyable free-time activity, it still requires some knowledge, reflection, and cognitive and often also emotional engagement on the part of residents or tourists. Many mass tourists are unlikely to become museum visitors despite intensive marketing efforts of museums and their outreach activities in public spaces. Even if such visitors become occasionally interested in local heritage, the offers of the commercial tourism sector prone to provide a lower quality narrative on local history, might be more likely to be selected by tourists not so much thanks to their low price but because of the cognitive ease of such tourism consumption. A similar issue is linked with the role of museums in shaping pro-ecological behaviors. Museum activities in this field are valuable, but they will only reach a certain share of the population, usually better educated and more culture-oriented residents and tourists.

Most good practice examples identified in the Polish context seem transferrable to other geographical settings. None the less, some important factors which impact on the extent of museums’ engagement in coping with overtourism and the applicability of the specific experiences of the two analyzed institutions in other national and local contexts must be mentioned. First, all of the described museum activities, even these which are able to generate some own income, require some sort of financial support from the public sector to be initiated and sustained. The multitude of activities undertaken by the two museums in Poland, in particular the museum in Krakow, are thus possible thanks to a stable, sizeable inflow of subsidies and grants from the local or regional governments respectively [60]. These, in turn, are linked with the rather good general situation of the Polish economy and the dynamic development of Krakow as the second largest Polish city. Both museums are also eligible for and often use the opportunity to tap into external sources of public funding such as EU funds or special programs of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage. Completion of numerous investments currently taking place in several museum buildings is likely to result in the enhanced impact of the Tatra Museum on the quality of heritage presentation as well as its better visibility in the urban space of Zakopane in the near future (e.g., new ideas with respect to functions of museum buildings depending on their location, more visitor-oriented functions in the city center) but will also require greater commercialization of its offers in order to cover growing maintenance costs.

An asset, though also a challenge, is the relatively strong embeddedness and sense of attachment of residents to both cities. This is linked with the fact that, despite large influxes of new residents in the interwar period and especially after World War II, in the Polish context, both Krakow and Zakopane are cities with a very large share of residents with a long family history rooted in the particular area.

Many museum activities depend on the existence of local (regional) partners who are willing to cooperate—in particular, non-governmental institutions, local community members, educational institutions, local governments, and museum supervising bodies [57,77]. For example, the Tatra Museum enjoys the possibility of extensive and multidimensional cooperation with a willing, complementary partner with a larger budget (the Tatra National Park). Both institutions have similar, often matching, interests and goals (protection and popularization of heritage and nature, respectively). They also share a common understanding of the need for high quality research and narration on local cultural and natural resources.

The scope and effectiveness of museums’ involvement in coping with overtourism is not only compromised by their budgets, competencies, and attitudes of museum staff but also depends on the overall trends in the tourism market and the strength and type of ties with local authorities [60]. The positive impact of the Museum of Krakow is enabled and enhanced by the fact that it enjoys a rather broad degree of freedom to pursue its own strategies and ideas. As a municipal institution, it has been given a clear mandate to act independently by the local authorities. They seem to trust the museum as an expert institution and the instincts of its director associated with many successes of the museum. Moreover, the recent initiatives undertaken by the local authorities in Krakow to deal with overtourism such as the establishment of a special expert group and a special task force entrusted with developing specific solutions to overtourism will benefit from activities already undertaken by the Museum of Krakow and at the same time enhance their positive impact.

As follows, many museum activities, in particular those that are implemented with a long-term vision and in cooperation with local partners, may contribute to weakening or reversing the vicious circle of overtourism [9]. Some of their initiatives are linked with new, broader roles played by museums in contemporary society, while others are undertaken in reaction to actual problems noticed in particular cities. One may venture to say, as an analogy to the idea of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), that museums are increasingly aware of their multidimensional Museum Social Responsibility (MSR). They are, to a growing extent, not only focused on the past and its reinterpretation but on fostering connections between the past and the present, between historic and contemporary issues, and new challenges and trends in terms of urban development, lifestyles or understanding of heritage and its values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-K. and D.H.; Investigation, M.M.-K. and D.H.; Writing—original draft, M.M.-K. and D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The empirical evidence presented in the text draws on empirical research conducted by both authors within the framework of the Polish edition of an OECD pilot project on “Culture and Local Development: Maximising the Impact” conducted in 2018.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the three anonymous reviewers and Chiara Dalle Nogare for their inspiring comments and valuable suggestions helpful in preparing the revised version of the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J.L. Developing and Testing a Tourism Impact Scale. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. The Tourist-Historic City: Retrospect and Prospect of Managing the Heritage City, 1st ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0080436753. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.P. Cultural Attractions and Destination Structure: A Case Study of the Venice Region. In Cultural Resources for Tourism. Patterns, Processes and Policies, 1st ed.; Jansen-Verbeke, M., Priestley, G.K., Russo, A.P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 43–58. ISBN 978-1-60456-970-4. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: Global Trends and Local Contexts; Ostelea School of Tourism and Hospitality: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. Introduction. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions, 1st ed.; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-3110620450. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. (Eds.) Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism, 1st ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781786399823. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. The Enablers of Overtourism. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 6–22. ISBN 978-3110620450. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural Heritage and Urban Tourism: Historic City Centres under Pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.P. The “Vicious Circle” of Tourism Development in Heritage Cities. Ann. Tourism. Res. 2002, 29, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee-Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/629184/IPOL_STU(2018)629184_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Timothy, D.J. Introduction. In Managing Heritage and Cultural Tourism Resources, 1st ed.; Timothy, D.J., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2007; pp. XI–XXV. ISBN 9780754627043. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.; Stettler, J.; Priskin, J.; Rosenberg-Taufer, B.; Ponnapureddy, S.; Fux, S.; Camp, M.-A.; Barth, M. Tourism Destinations under Pressure. In Challenges and Innovative Solutions; Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts: Lucerne, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56dacbc6d210b821510cf939/t/5906f320f7e0ab75891c6e65/1493627704590/WTFL_study+2017_full+version.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2019).

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. Conclusion. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 262–276. ISBN 978-3110620450. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.-J. Overtourism in European Cities: From Challenges to Coping Strategies. CESifo Forum. 2019, 20, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Living in a World Heritage City: Stakeholders in the Dialectic of the Universal and Particular. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, A.; Staniscia, B. Rome: A Difficult Path between Tourist Pressure and Sustainable Development. Riv. Sci. Tur. 2010, 2, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, M.; Hidalgo, C. Tourism in the Historic Cores, Conflict or Opportunity? The Stakeholders Point of View in Madrid’s Case. Riv. Sci. Tur. 2010, 1, 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, S.; Nyaupane, G.P.; Budruk, M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives of Sustainable Tourism Development: A New Approach to Measuring Outcomes. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomb, C.; Novy, J. (Eds.) Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-85671-4. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, J. Urban Tourism as a Bone of Contention: Four Explanatory Hypotheses and a Caveat. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 5, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Egedy, T.; Csizmady, A.; Jancsik, A.; Olt, G.; Michalkó, G. Non-Planning and Tourism Consumption in Budapest’s Inner City. Tourism. Geogr. 2018, 20, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtenshaw, D.; Bateman, M.; Ashworth, G.J. The European City: A Western Perspective, 1st ed.; Fulton Publishers: London, UK, 1991; ISBN 0470217618. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. (Ed.) The Development of Cultural Tourism in Europe. In Cultural Attractions and European Tourism; Cabi Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 3–29. ISBN 0851994407. [Google Scholar]

- Culture and Local Development: Maximising the Impact. In Guide for Local Governments, Communities and Museums; OECD; ICOM: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ICOM-OECD-GUIDE_EN_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- ‘Overtourism’?–Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-92-844-2006-3.

- Del Romero Renau, L. Touristification, Sharing Economies and the New Geography of Urban Conflicts. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Shaken, not Stirred. New Debates on Touristification and the Limits of Gentrification. City 2018, 22, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Diaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, Transnational Gentrification and Touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Stud. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. The Challenge of Overtourism. Responsible Tour. Partnersh. Work. Pap. 2017, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban Tourism Hypertrophy: Who Should Deal with It? The Case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, 1st ed.; Pitman: Marshfield, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 0-273-01913-9. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E.; Murphy, A.E. Strategic Management for Tourism Communities: Bridging the Gaps; Channel View Publications: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004; ISBN 1-873150-83-0. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, E.; Le Pelley, B. Managing Complexity and Change in Tourism The Case of a Historic City. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]