Linking of Traditional Food and Tourism. The Best Pork of Wielkopolska—Culinary Tourist Trail: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

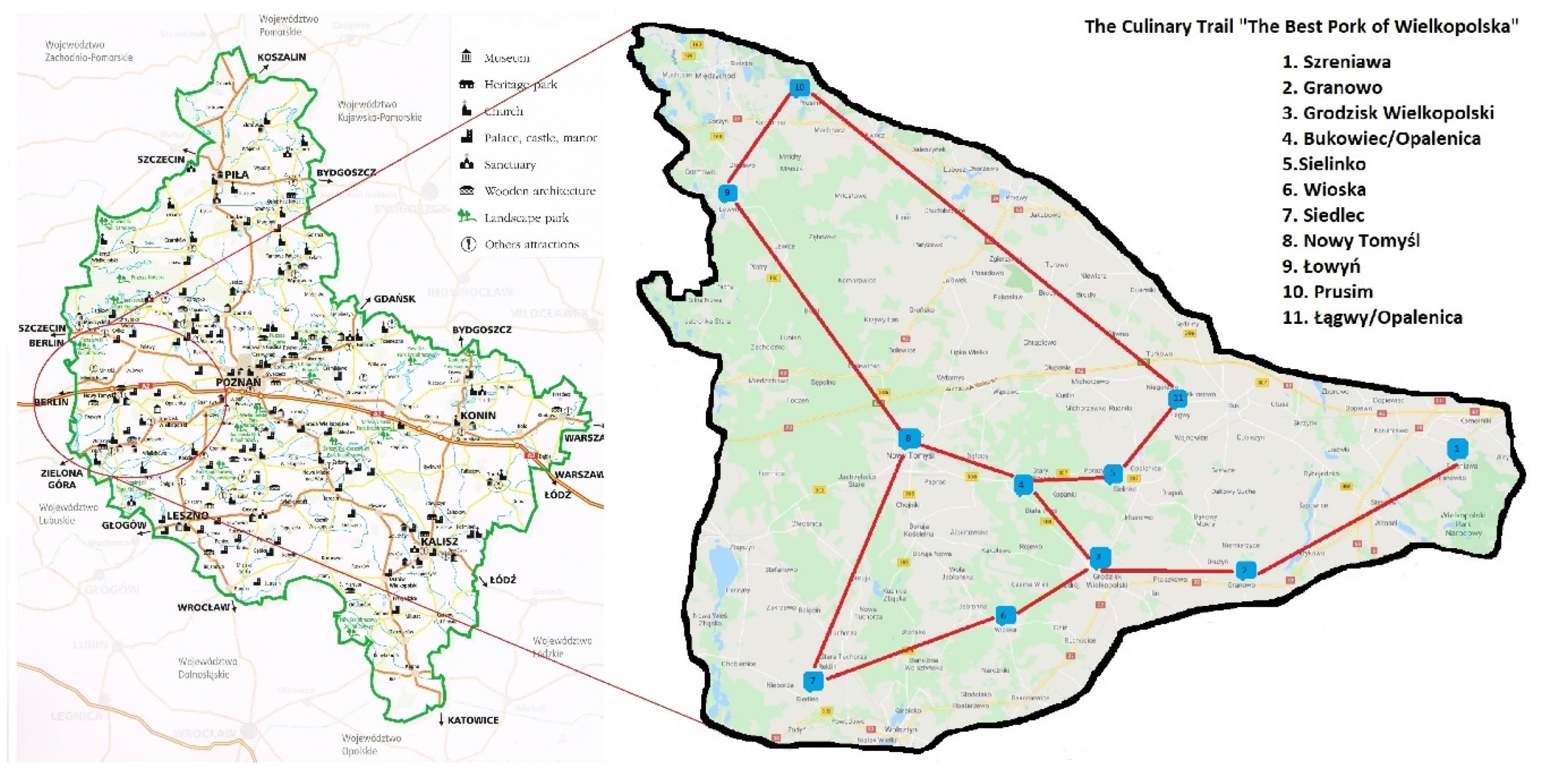

1.1. Culinary Trails

- -

- Origin in the region. The product should be made with techniques typical of the region and based on local traditions;

- -

- Range. The product must be characteristic of a specific place or region. The following dependence is crucial: the smaller the range, the greater the tourist attractiveness of the product. This results from a simple assumption: the more unique the good, the more willing a tourist will be to take a trip to benefit from it;

- -

- Producer. Attractiveness is a derivative of locality. If a product is manufactured by a local community, the community is provided with the profits and economic benefit. This also translates into their greater care to preserve and cultivate this value because, besides the deposit of tradition, it is also their source of income. The ideal situation is when the owner and distributor of a product is, at the same time, its manufacturer, and the main place of distribution is the place of production. It can therefore be assumed that the more local the product is, the higher its authenticity;

- -

- Raw material. The product’s attractiveness is greater if the raw material used for production is local or regional [51].

- Restaurant trails—usually urban trails leading to the best gastronomic establishments, offering various ethnic cuisines from all over the world (e.g., The Culinary Trail of Gdynia Centre, Białystok Culinary Trail, Culinary Poznań);

- Regional culinary heritage trails—they enable tourists to get to know the tradition of the local culinary products in a given region (e.g., Livonian Culinary Route, Baltic Sea Culinary Routes, Le Strade dei Vini e dei Sapori, Śląskie Smaki and Podkarpackie Smaki Culinary Trails);

- Monographic trails—dedicated to selected products or dishes, e.g., cheese (e.g., Route de Fromage, Emmentaler Käsestrasse, Szlak Oscypkowy), fruit (e.g., Steirishe Apfelstrasse, La Route du Cassis, Małopolski Szlak Owocowy, Śliwkowy Szlak), wines (e.g., Route des Vins d’Alsace, Deutsche Weinstraße, Moravské vinařské stezky, Małopolski Szlak Winny), or animal products (e.g., Strada del Culatello di Zibello, Kujawsko-Pomorski Gęsinowy Szlak Kulinarny, Szlak Karpia);

- Multi-theme trails with a culinary component—combining several groups of tourist attractions (e.g., historical monuments, folklore, nature, cuisine) into one integrated product, in which local gastronomy plays a particularly important role, becoming an attractive commodity on the market (e.g., Strada del Prosciutto e dei vini dei Colli di Parma, Szlak Tradycji i Smaku na Ziemi Chełmińskiej).

1.2. Local Product and Tourism

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Poland Case Study

3.2. Pork Meat as an Element of the Cultural Heritage of Wielkopolska

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hjalager, A.-M.; Corigliano, M.A. Food for tourists—determinants of an image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Ma, F. Food and gastronomy research in tourism and hospitality: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism; Material Worlds; The University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780813122922. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, D.; Shishaev, M.; Dikovitsky, V. Food System Digitalization as a Means to Promote Food and Nutrition Security in the Barents Region. Agriculture 2019, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; (Simon) Tsai, C.-T. Government websites for promoting East Asian culinary tourism: A cross-national analysis. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L. Sustainability of Agritourism Activity. Initiatives and Challenges in Romanian Mountain Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Martinez, U.J.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordek, S.M. Gastronomy Has No Borders. Global Trends in Food Tourism and Its Opportunities in Poland. Thesis, Central University of Applied Sciences, Degree Programme in Tourism, November 2013. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/70740/Kordek_Sara.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Fernandes, C.; Richards, G. Sustaining Gastronomic Practices in the Minho Region of Portugal; Breda University of Applied Sciences: Breda, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. Culinary Tourism: A Tasty Economic Proposition; International Culinary Tourism Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2002; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Chou, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-Y. Understanding the impact of culinary brand equity and destination familiarity on travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniczko, M.; Jędrysiak, T.; Orłowski, D. Turystyka Kulinarna [Culinary Tourism]; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Routledge: Abington Thames, UK, 2004; p. 392. ISBN 9780080477862. [Google Scholar]

- Program rozwoju i promocji turystyki gastronomicznej i szlaków kulinarnych w Polsce. Landbrand, Hubert Gonera & Polska Organizacja Turystyczna w Warszawie. Available online: http://docplayer.pl/17513202-Program-rozwoju-i-promocji-turystyki-gastronomicznej-i-szlakow-kulinarnych-w-polsce.html (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Jęczmyk, A. Turystyka kulinarna jako element rozwoju lokalnego [Culinary tourism as an element of local development]. In Proceedings of the Hradecké Ekonomické dny. Roč. 6(1). Recenzovaný Sborník Mezinárodní Odborné Konference Hradecké Ekonomické dny 2016; Univerzita Hradec Králové: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. We Are what We Eat: Food, Tourism and Globalization. Tour. Cult. Comun. 2000, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov, E. The Canadian Culinary Tourists: How Well Do We Know Them? University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

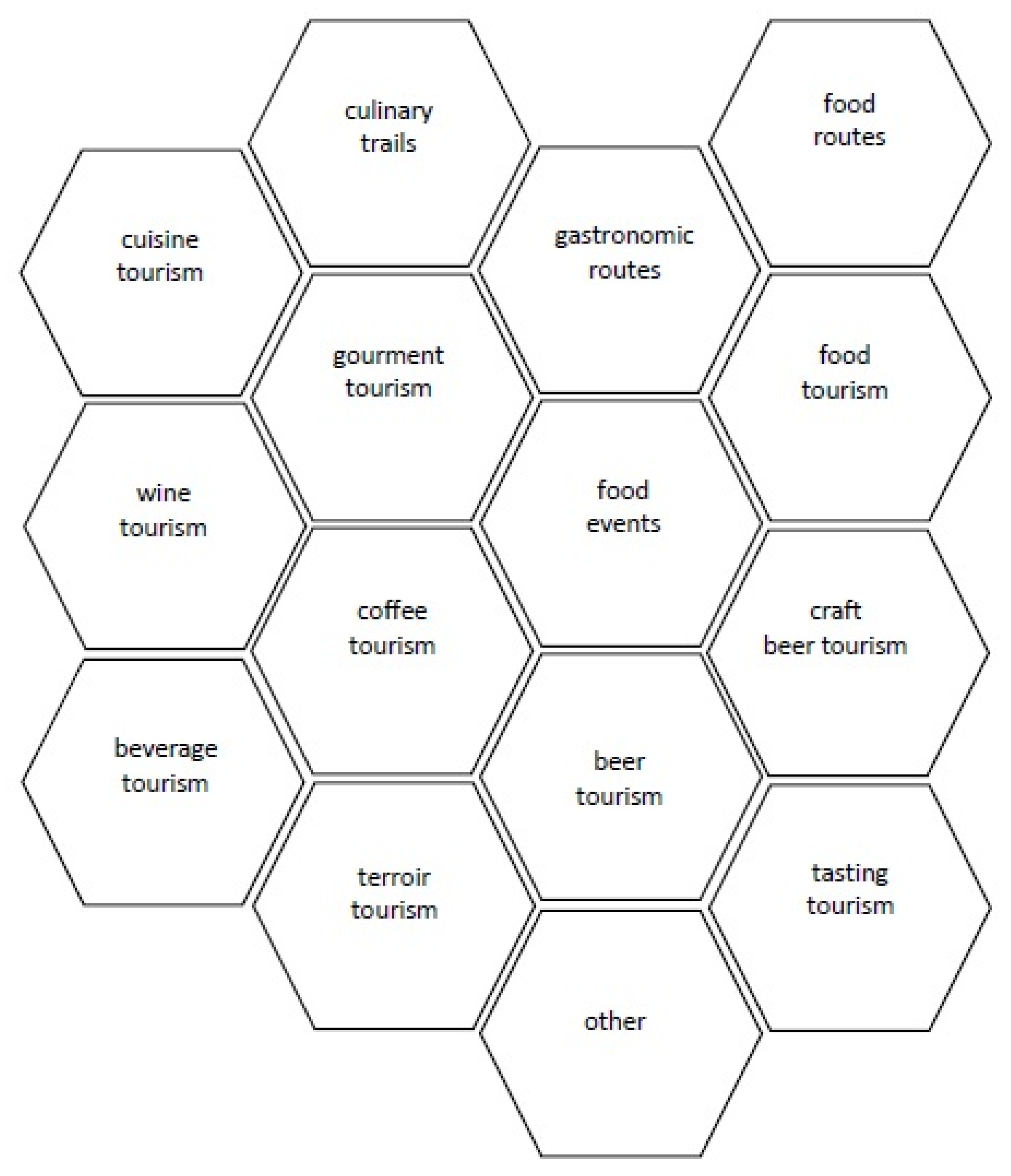

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Slocum, S.L. Food and tourism: An effective partnership? A UK-based review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovičová, K.; Pompura, M. The culinary tourism in Slovakia. Case study of the traditional local sheep’s milk products in the regions of Orava and Liptov. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2013, 12, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Kasprzak, K. Turystyka kulinarna w świetle koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju w Polsce [Culinary tourism in the light of sustainable development concept in Poland]. Polish J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 21, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism and Agriculture; Torres, R., Momsen, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780203834404. [Google Scholar]

- du Rand, G.E.; Heath, E. Towards a Framework for Food Tourism as an Element of Destination Marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E. Measuring Gastronomic Image Online. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, Quality, and Loyalty: Local Food and Sustainable Tourism Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R.; Kirkpatrick, I.; Mitchell, M. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business; Aspects of Tourism Collection; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2005; ISBN 9781845410124. [Google Scholar]

- Lampridi, M.G.; Sørensen, C.G.; Bochtis, D. Agricultural Sustainability: A Review of Concepts and Methods. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żmija, D. Zrównowazony rozwój rolnictwa i obszarów wiejskich w Polsce [Sustainable development of agriculture and rural areas in Poland]. Stud. Ekon. 2014, 165, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Prus, P. Farmers’ opinions about the prospects of family farming development in Poland. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference “Economic science for Rural Development”, No 47, Jelgava, Latvia, 9–11 May 2018; pp. 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, P. The role of higher education in promoting sustainable agriculture. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2019, 99–119, Special Issue “Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics in the Central and Eastern Europe”. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglis, J. Miejsce turystyki w rozowju wielofunkcyjnym obszarów wiejskich [Tourism in multifunctional development of rural areas]. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. i Agrobiznesu 2011, 13, 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Ferens, E. Turystyka jako element wielofunkcyjnego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich na przykładzie województwa mazowieckiego [Tourism as an element of multifunctional development of rural areas: Case of Mazovia region]. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW w Warszawie. Ekon. I Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2013, 102, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chudy-Hyski, D.; Hyski, M. The role of tourism in multifunctional development of mountain rural areas. Infrastruct. Ecol. Rural areas 2018, 3, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, R.; Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Migliore, G. Culinary Tourism Experiences in Agri-Tourism Destinations and Sustainable Consumption—Understanding Italian Tourists’ Motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Cetin, G. Marketing Istanbul as a culinary destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, D.; Woźniczko, M. Dziedzictwo kulinarne Polski i jego rola w rozwoju agroturystyki [The culinary heritage of Poland and its role in the development of agritourism]. In Innowacje w Turystyce Wiejskiej—szansa czy Konieczność [Innovations in Rural Tourism—A Chance or a Necessity]; Ditrich, B., Ceglarska, S., Eds.; Pomorski Ośrodek Doradztwa Rolniczego w Gdańsku: Gdańsk, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sieczko, A. Rola kuchni regionalnych w kreowaniu lokalnego produktu turystycznego [The role of regional cuisine in the creation of the local tourism product]. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego nr 590, Ekon. Probl. Usług 2010, 52, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gutkowska, K.; Gajowa, K. Możliwości rozwoju turystyki kulinarnej w Polsce [Possibilities of culinary tourism development in Poland]. Postępy Tech. Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 2015, 2, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, R.; Telfer, D.; Hashimoto, A.; Summers, R. Beer tourism in Canada along the Waterloo–Wellington Ale Trail. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J.; Stasiak, A.; Włodarczyk, B. Produkt turystyczny. Pomysł, Organizacja, Zarządzanie [Tourist product. Idea, Organization, Management]; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rochmińska, A.; Stasiak, A. Strategie rozwoju turystyki [Tourism development strategies]. Tur. i Hotel. 2004, 6, 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Szlaki Turystyczne, od Pomysłu do Realizacji [Tourist Routes, from Idea to Implementation]; Stasiak, A., Śledzińska, J., Włodarczyk, B., Eds.; Wydawnictwo PTTK, Kraj”: Warszawa–Łódź, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. Polska. Geografia Atrakcji Turystycznych [Poland. Geography of Tourist Attractions]; Proksenia: Kraków, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Icomos Charter on Cultural Routes International. Scientific Committee on Cultural Routes (CIIC) of ICOMOS. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/quebec2008/charters/cultural_routes/EN_Cultural_Routes_Charter_Proposed_final_text.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Meyer, D. Key Issues for the Development of Tourism Routes and Gateways and Their Potential for Pro-Poor Tourism; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Flognfeldt, T., Jr. The tourist route system—models of travelling patterns. Belgeo 2005, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, J. Szlak kulinarny jako przykład szlaku tematycznego [Culinary trail as an example of a thematic trail]. Pr. i Stud. Geogr. 2013, 52, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Widawski, K.; Oleśniewicz, P. Thematic Tourist Trails: Sustainability Assessment Methodology. The Case of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization, Global Report on Food Tourism. AM Reports Vol. 4; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- Coelho, F.C.; Coelho, E.M.; Egerer, M. Local food: Benefits and failings due to modern agriculture. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwil, I.; Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Krzywonos, M. Local Entrepreneurship in the Context of Food Production: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessiere, J.; Tibere, L. Traditional food and tourism: French tourist experience and food heritage in rural spaces. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3420–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.V.; Waehrens, S.S.; O’Sullivan, M.G. Future development, innovation and promotion of European unique food: An interdisciplinary research framework perspective. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3414–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęczmyk, A. Winnice jako element polskiego dziedzictwa kulturowego na terenach wiejskich [Vineyards as an element of Polish cultural heritage in rural areas]. Zagadnienia Doradz. Rol. 2019, 3, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe, B.; Bauman, M. Terroir Tourism: Experiences in Organic Vineyards. Beverages 2019, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, B.; Lee, S. Conceptualizing Terroir Wine Tourism. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniczko, M.; Piekut, M. Stan rynku żywności regionalnej i tradycyjnej w Polsce [The state of market of regional and traditional products in Poland]. Postępy Tech. Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 2015, 1, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rytkönen, P.; Bonow, M.; Girard, C.; Tunón, H. Bringing the Consumer Back in—The Motives, Perceptions, and Values behind Consumers and Rural Tourists’ Decision to Buy Local and Localized Artisan Food—A Swedish Example. Agriculture 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiechowska, M. Zapewnienie autentyczności i wiarygodności produktom regionalnym i tradycyjnym [Ensuring authenticity and reliability of regional and traditional products]. Stow. Ekon. Rol. i Agrobiznesu Rocz. Nauk. 2014, 16, 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Duda-Seifert, M.; Drozdowska, M.; Rogowski, M. Produkty turystyki kulinarnej Wrocławia i Poznania—analiza porównawcza [Culinary products of Wroclaw and Poznan—comparative analysis]. Tur. Kult. 2016, 5, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, D.J.; Wall, G. Linkages between Tourism and Food Production. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białogowska, A. Culinary tourism as an important, intercultural issue. Sci. Rev. Phys. Cult. 2014, 4, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gugerell, K.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kieninger, P.R.; Penker, M.; Kajima, S.; Kohsaka, R. Do historical production practices and culinary heritages really matter? Food with protected geographical indications in Japan and Austria. J. Ethn. Foods 2017, 4, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Touzard, J.-M. Geographical Indications, Public Goods, and Sustainable Development: The Roles of Actors’ Strategies and Public Policies. World Dev. 2017, 98, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union L 341; Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs; Document 32012R1151; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Soroka, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Consumer Awareness of the Regional Food Market: The Case of Eastern European Border Regions. Foods 2019, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOOR Database. European Commission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/list.html (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Weichselbaum, E.; Benelam, B.; Costa, H.S. Traditional Foods in Europe. Synthesis Report No. 6; EuroFIR Project Management Office, British Nutrition Foundation: Norwich, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krupiński, J.; Radomski, P.; Moskała, P.; Mikosz, P.M.; Paleczny, K. Certyfikacja surowców i produktów ras rodzimych [Certification of raw materials and products of native breeds]. Wiadomości Zootech. 2017, 55, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Potential of olive oil tourism in promoting local quality food products: A case study of the region of Extremadura, Spain. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Rohrscheidt, A.M. Kulturowe szlaki turystyczne—próba klasyfikacji oraz postulaty w zakresie ich tworzenia i funkcjonowania [Cultural tourist routes—classification attempt and requirements for their creation and functioning]. Tur. Kult. 2008, 2, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Von Rohrscheidt, A.M. Szlaki kulturowe jako skuteczna forma tematyzacji przestrzeni turystycznej na przykładzie Niemieckiego Szlaku Bajek [Cultural routes as an effective form of the tourist space thematization—the case study of the German Fairy Tale Route]. Tur. Kult. 2011, 9, 4–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiak, A. Rozwój turystyki kulinarnej w Polsce [Development of culinary tourism in Poland]. In Kultura i turystyka—wokół wspólnego stołu [Culture and Tourism—Around a Shared Table]; Krakowiak, B., Stasiak, A., Eds.; Regionalna Organizacja Turystyczna Województwa Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015; pp. 119–149. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, M.; Batyk, I.M. Szlaki kulinarne jako forma konkurencyjności oferty turystycznej [Culinary trails as a form of competitiveness tourist offers]. Zesz. Nauk. Uczel. Vistula 2017, 54, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Pogłowie świń według stanu w czerwcu 2019 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5508/10/3/1/poglowie_swin_wedlug_stanu_w_czerwcu_2019_roku.pdf+&cd=1&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Szulc, K.; Skrzypczak, E. Jakość mięsa polskich rodzimych ras świń [Meat quality of Polish native pigs]. Wiadomości Zootech. 2015, 53, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Karim, S.; Chi, C.G.-Q. Culinary Tourism as a Destination Attraction: An Empirical Examination of Destinations’ Food Image. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Czech, K. Food trails in Austria. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; p. 373. ISBN 0750655038. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, D.J.; Hashimoto, A. Food tourism in the Niagara Region: The development of a nouvelle cuisine. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; p. 373. ISBN 0750655038. [Google Scholar]

- Global Report on Food Tourism, UNWTO. Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/import/Projects/Gastronomic_Cities/outputs_media/Food_tourism.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- The Trademark for Regional Food & Culinary Traditions! Available online: https://www.culinary-heritage.com/information.asp?PageID=21 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, M. Consuming tourists: Food tourism consumer behaviour. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; p. 373. ISBN 0750655038. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Food and the tourism experience: Major findings and policy orientations. In Food and the Tourism Experience; Dodd, D., Ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Smith, A. The experience of consumption or the consumption of experiences? Challenges and issues in food tourism. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; p. 373. ISBN 0750655038. [Google Scholar]

- Buiatti, S. Food and tourism: The role of the “Slow Food” association. In Food, Agriculture and Tourism. Linking Local Gastronomy and Rural Tourism: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Sidali, K.L., Spiller, A., Schulze, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 92–102. ISBN 978-3-642-11360-4. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, B.; Ayala, C. Regional tourism at the farmers’ market: Consumers’ preferences for local food products. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food, Wine and China; Pforr, C., Phau, I., Eds.; Routledge: Abington Thames, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781315188317. [Google Scholar]

- Food and the Tourism Experience; OECD Studies on Tourism; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; ISBN 9789264110595.

- Jaffe, E.; Pasternak, H. Developing wine trails as a tourist attraction in Israel. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz-Pizlo, A. The importance of non-profit organisations in developing wine tourism in Poland. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2016, 14, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujdoso, Z.; Szucs, C. Beer tourism—from theory to practice. Acad. Tur. 2012, 5, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Star, M.; Rolfe, J.; Brown, J. From farm to fork: Is food tourism a sustainable form of economic development? Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 66, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jȩczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Graja-Zwolińska, S.; Maćkowiak, M.; Spychała, A.; Sikora, J. Research Note: Economic Benefits of Agritourism Development in Poland—An Empirical Study. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Maćkowiak, M. Food products as an element influencing agritourism farmer’s attractiveness. Rocz. Nauk. Ser. 2013, 15, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Prus, P. Innovations in Agritourism: Evidence from a Region in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Places | Events | People | Meals and Regional Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| taverns; inns; shops with regional products; shops with organic food; objects related to food production technology; vineyards; breweries; bread making places | culinary festivals; fairs and markets with regional food; culinary workshop and degustation; cooking art shows; vintage and other harvests | producers; craftsmen; farmers, etc., dealing with the production of regional food products; people storing the memory of traditional food processing technologies and others | existing in a given area or included in local or European programs for the protection of food products |

| Places | Events | People | Meals and Regional Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kuślin Jansowo Training and Recreation Center; Olenderski Open-Air Museum Olandia Prusim; Museum of Meat Management in Sielinko; Butcher Plant in Bukowiec, near Opalenica; Kopanica; Siedlec; The Village Museum of Agriculture and Agri-food Industry in Szreniawa; Meat Factory Szajek Granowo | Wielkopolska Agricultural Fair in Sielinko; Pig’s Day in Siedlec | Łowyń Organic Agricultural—Agritourism Farm “Tamarynowa settlement”; Łagwy Farm near Opalenica | Nowy Tomyśl sausage; Wielkopolska Złotnicka pork; roasted leg of Złotnicka pig; Kruszewnia rural sausage; Kruszewnia rural brawn; Kruszewnia liver sausage, Wielkopolska roll; Wielkopolska white blanched sausage; Polish smoked sausage; Grodzisk sausage; Grodzisk liver sausage; Grodzisk tongue brawn; Grodzisk ‘bułczanka’; Rychtalska black pudding; Wielkopolska ‘leberka’ |

| Places on the Trail | Products Related to Pork |

|---|---|

| Szreniawa | exhibition of live Złotniki pigs, Museum of Agriculture and Agricultural and Food Industry |

| Granowo | meat shops, possible purchase of Wielkopolska blanched white sausage and other pork products (e.g., Szajek Meat-Processing Company’s store) |

| Grodzisk Wielkopolski | meat shops, possible purchase of Wielkopolska blanched white sausage, Grodzisk sausage, Grodzisk liver sausage, Grodzisk tongue brawn, Grodzisk ‘bułczanka’ |

| Bukowiec/Opalenica | plant, butcher’s shop (Słociński Meat-Processing Company), possible purchase of pork products |

| Sielinko | Museum of Meat-Processing Equipment |

| Wioska | Krzysztof Zielinski’s Meat-Processing Company, possible purchase of pork products |

| Siedlec | ‘Sobkowiak’ Meat-Processing Company, possible purchase of pork products, Pig Day (pork meat competition, traditional pork products) |

| Nowy Tomyśl | meat shops, possible purchase of Wielkopolska blanched white sausage, roasted leg of Złotnicka pig, Nowy Tomyśl matured sausage, Wielkopolska ‘leberka’ Hop-wickerwork fair: stands with pork sausages |

| Łowyń | agritourism farm, own sausages based on meat from Złotnicka pig, and pork neck, pork chop or pork tenderloin, Network of Culinary Heritage of Wielkopolska |

| Prusim, Olandia | accommodation facility, restaurant: the menu is based on products from regional suppliers, including Złotniki pork from Gorzyń, Wielkopolska Culinary Heritage Network |

| Łągwy/Opalenica | farm, own sausages based on pork |

| Place | Attractions |

|---|---|

| Trzebaw | Deli Park—education and entertainment park |

| Granowo | St. Marcin Wooden church |

| Łęk Mały | Wielkopolska pyramids (kurgan) |

| Grodzisk Wielkopolski | Grodzisk Draisine railway |

| St. Jadwiga Parish Church | |

| Wioska | The Land of Bogil’s Fun |

| Rakoniewice | Wielkopolska Museum of Firefighting |

| Wolsztyn | Museum of Steam Locomotives |

| Robert Koch Museum | |

| Open-Air Museum of Folk Architecture of Western Wielkopolska | |

| Obra | Monastery Church of the Oblates, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint James the Apostle Church |

| Nowy Tomyśl | Wicker and Hop Growing Museum; the largest wicker basket |

| Wąsowo | Palace and landscape park and Wąsowo Farm |

| Mniszki | Regional and Natural Education Center |

| Opalenica | The first motorcycle factory in Poland with the symbolic name “LECH” |

| Historic Town Hall | |

| Górzno/Opalenica | Rope park |

| Brody | Wooden church of St. Andrzej from 1673, next to the belfry from the 17th century |

| Chalin | Nature Education Center |

| Lusowo | Museum of Wielkopolska Insurgents |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niedbała, G.; Jęczmyk, A.; Steppa, R.; Uglis, J. Linking of Traditional Food and Tourism. The Best Pork of Wielkopolska—Culinary Tourist Trail: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135344

Niedbała G, Jęczmyk A, Steppa R, Uglis J. Linking of Traditional Food and Tourism. The Best Pork of Wielkopolska—Culinary Tourist Trail: A Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135344

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiedbała, Gniewko, Anna Jęczmyk, Ryszard Steppa, and Jarosław Uglis. 2020. "Linking of Traditional Food and Tourism. The Best Pork of Wielkopolska—Culinary Tourist Trail: A Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135344

APA StyleNiedbała, G., Jęczmyk, A., Steppa, R., & Uglis, J. (2020). Linking of Traditional Food and Tourism. The Best Pork of Wielkopolska—Culinary Tourist Trail: A Case Study. Sustainability, 12(13), 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135344