Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods for Species and Species Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Teaching and Learning for Sustainability

2.2. Teaching and Learning of Species and Species Identification

3. The Aim of the Study and Research Questions

- What kind of views do the student teachers express about the most efficient methods for teaching and learning species and species identification?

- What kind of views do the student teachers express about the most efficient materials and sources for teaching and learning species and species identification?

- What kind of characteristics and strategies do the student teachers prefer when they identify species?

- Do student teachers’ views on efficiency reflect their results in the species identification test?

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

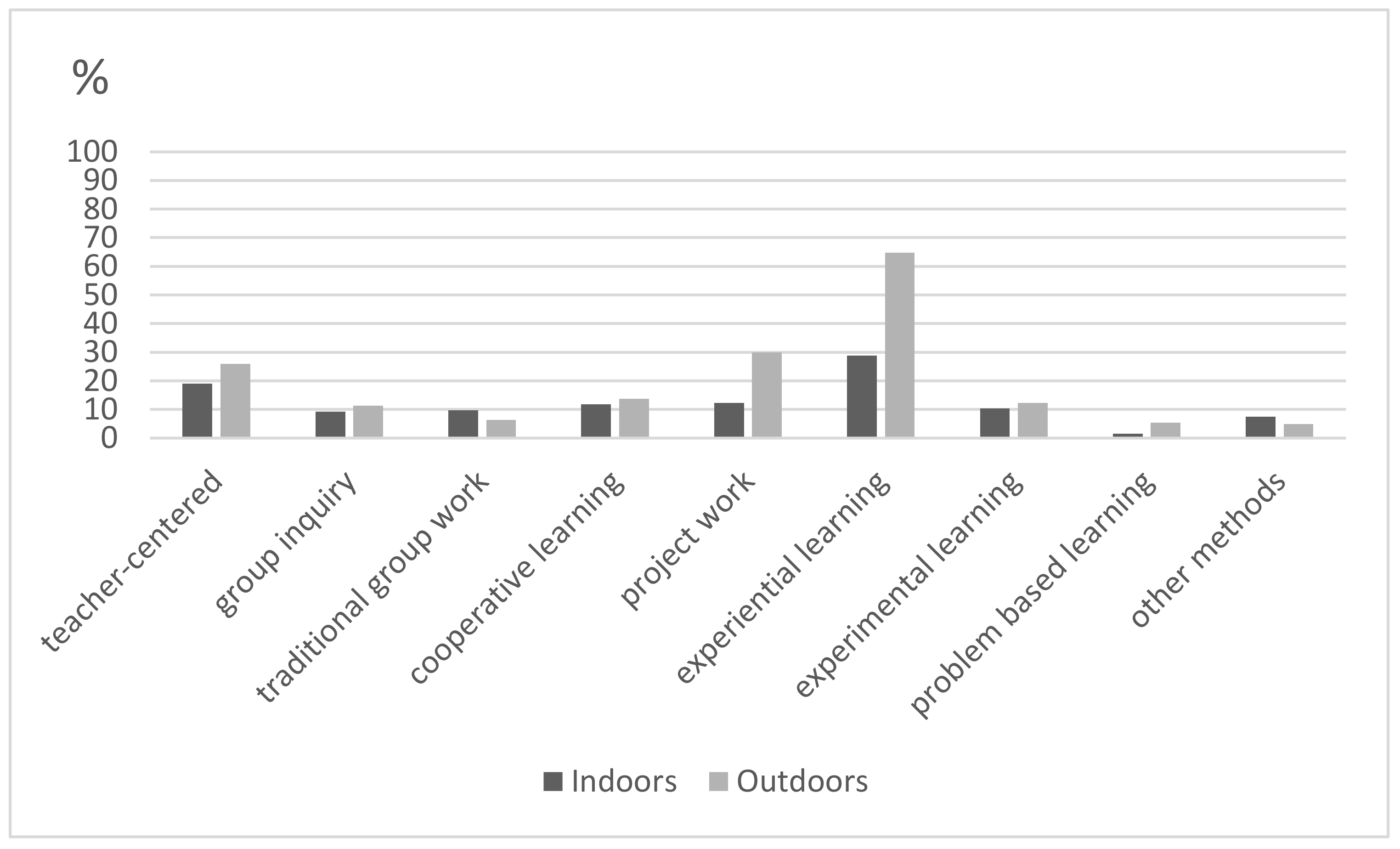

5.1. Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods

Student Teachers’ Explanations

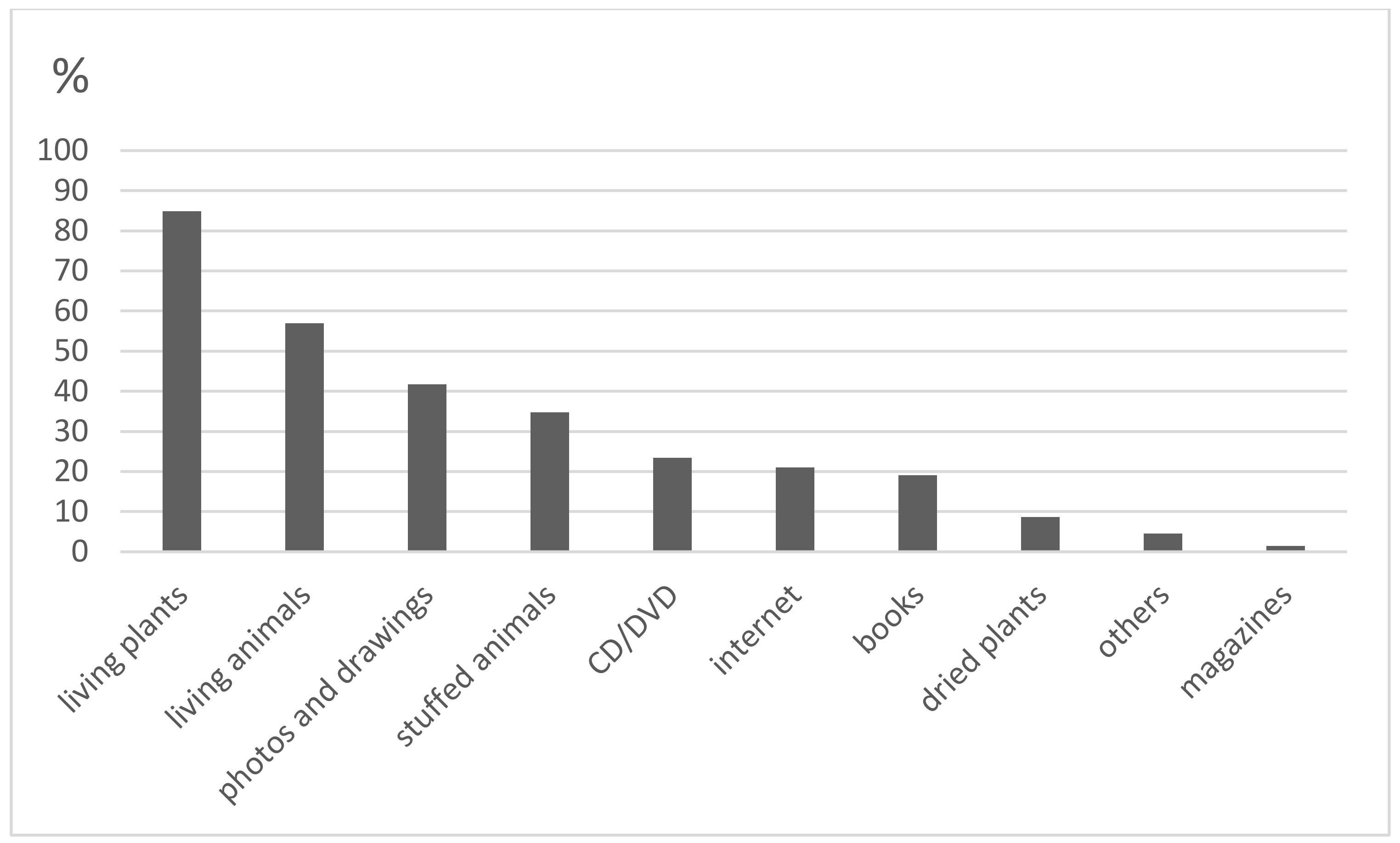

5.2. Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Materials and Sources for Teaching and Learning

Student Teachers’ Explanations

5.3. Student Teachers’ Preferences for Characteristics When Identifying Species

6. Concluding Discussion

6.1. Outdoor Experiential Learning and Outdoor Project Work with Living Plants and Animals

6.2. Teachers’ Role in Teaching and Learning Species and Species Identification

6.3. Media and the Internet for Teaching and Learning Species and Species Identification

6.4. Limitations

6.5. Summarizing Pedagogical Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaasinen, A. Kasvilajien Tunnistaminen, Oppiminen ja Opettaminen Yleissivistävän Koulutuksen Näkökulmasta. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Palmberg, I.; Jonsson, G.; Jeronen, E.; Yli-Panula, E. Blivande lärares uppfattningar och förståelse av baskunskap i ekologi i Danmark, Finland och Sverige. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 12, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C. Teaching species identification: A prerequisite for learning biodiversity and understanding ecology. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2008, 4, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Bose, E. How many species are there? Public understanding and awareness of biodiversity in Switzerland. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandersee, J.H.; Schussler, E.E. Toward a Theory of Plant Blindness. Plant Sci. Bull. 2001, 47, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bickford, D.; Posa, M.R.C.; Qie, L.; Compos-Arceiz, A.; Kudovidanage, E.P. Science communication for biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 151, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I.; Hermans, M.; Jeronen, E.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Persson, C.; Yli-Panula, E. Nordic student teachers’ views on the importance of species and species identification. JSTE 2018, 29, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish National Board of Education. The National Core Curriculum for Basic Education; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Board of Education. The National Core Curriculum for General Upper Secondary Schools; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Ministry of Education, Research and Church Affairs. Core Curriculum for Primary, Secondary and Adult Education in Norway; Royal Ministry of Education, Research and Church Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2015; Available online: https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/lareplan/generell-del/core_curriculum_english.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Swedish National Agency for Education. Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Recreation Centre; Swedish National Agency for Education: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/publikationer/visa-enskild-publikation?_xurl_=http%3A%2F%2Fwww5.skolverket.se%2Fwtpub%2Fws%2Fskolbok%2Fwpubext%2Ftrycksak%2FBlob%2Fpdf2687.pdf%3Fk%3D2687 (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Evagorou, M.; Dillon, J.; Viiri, J.; Albe, V. Pre-service Science teacher preparation in Europe: Comparing pre-service teacher preparation programs in England, France, Finland and Cyprus. JSTE 2015, 26, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, T.; Babiuk, G. The status of education for sustainability in initial teacher education programmes: A Canadian case study. IJSHE 2014, 15, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, A.; Bröckl, M.; Oja, L.; Ahvenharju, S.; Raivio, T. Kansallisten Kestävää Kehitystä Edistävien Kasvatuksen ja Koulutuksen Strategioiden Toimeenpanon Arviointi; Gaia Consulting Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2014; Available online: http://www.ym.fi/download/noname/%7B7A0AC771-670C-48B8-B7F8-8FB0B173236F%7D/78365 (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Wolff, L.A.; Sjöblom, P.; Hofman-Bergholm, M.; Palmberg, I. High performance education fails in sustainability?—A reflection on Finnish primary teacher education. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvammen, P.I.; Munkebye, E. Artskunnskap Som Introduksjon Til Naturfag i Grunnskolelærerutdanningene. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 14, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Constantinou, C.; Junge, X.; Köhler, K.; Mayer, J.; Nagel, U.; Raper, G.; Schule, D.; Kadji-Beltran, C. The integration of biodiversity education in the initial education of primary school teachers: Four comparative case studies from Europe. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I.; Berg, I.; Jeronen, E.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Norrgård-Sillanpää, P.; Persson, C.; Vilkonis, R.; Yli-Panula, E. Nordic-Baltic student teachers’ identification of and interest in plant and animal species: The importance of species identification and biodiversity for sustainable development. JSTE 2015, 26, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Wiek, A. Beyond interpersonal competence: Teaching and learning professional skills in sustainability. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellikka, A.; Lutovac, S.; Kaasila, R. The nature of the relation between pre-service teachers’ views of an ideal teacher and their positive memories of biology and geography teachers. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 14, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoller, U. Research-based transformative science/STEM/STES/STESEP education for ‘sustainability thinking’: From teaching to ‘know’ to learning to ‘think’. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4474–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I.; Hofman-Bergholm, M.; Jeronen, E.; Yli-Panula, E. Systems thinking for understanding sustainability? Nordic student teachers’ views on the relationship between species identification, biodiversity and sustainable development. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.J.J.M.; Tigelaar, D.E.H.; Verloop, N. Developing biology lessons aimed at teaching for understanding: A domain-specific heuristic for student teachers. JSTE 2009, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mensah, F.M. Teaching contexts that influence elementary preservice teachers’ teacher and science teacher identity development. JSTE 2018, 29, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großschedl, J.; Harms, U.; Kleickmann, T.; Glowinski, I. Preservice biology teachers’ professional knowledge: Structure and learning opportunities. JSTE 2015, 26, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.E.; Groulx, J.; Bloom, M.A.; Weinburgh, M.H. Assessing teacher self-efficacy through an outdoor professional development experience. Electr. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 12, 1–25. Available online: http://ejse.southwestern.edu (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Hwang, H. The influence of the ecological contexts of teacher education on South Korean teacher educators’ professional development. TTE 2014, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandholtz, J.H.; Ringstaff, C. The influence of contextual factors on the sustainability of professional development outcomes. JSTE 2016, 27, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, T.J.; Parker, J.M.; Ebenhardt, J. Assessing teachers’ science content knowledge: A strategy for assessing depth of understanding. JSTE 2013, 24, 717–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. IJSHE 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Transformative learning and sustainability: Sketching the conceptual ground. JLTHE 2011, 5, 17–33. Available online: http://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files/0cd7b8bdb08951af53e5927e86938977.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Pugh, K.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L.; Koskey, K.L.K.; Stewart, V.C.; Manzey, C. Motivation, learning, and transformative experience: A study of deep engagement in science. Sci. Educ. 2009, 94, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, F.X. Environmental values (2-MEV) and appreciation of nature. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Constantinou, C.; Lehnert, H.J.; Nagel, U.; Raper, G.; Kadji-Beltran, C. Confidence and perceived competence of preservice teachers to implement biodiversity education in primary schools—Four comparative case studies from Europe. IJSE 2011, 33, 2247–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experiences as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.M. Introducing a fifth pedagogy: Experience-based strategies for facilitating learning in natural environments. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M.; Dillon, J.; Teamey, K.; Morris, M.; Young Choi, M.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. A Review of Research on Outdoor Learning; National Foundation for Educational Research: Slough, UK, 2004; Available online: https://www.field-studies-council.org/media/268859/2004_a_review_of_research_on_outdoor_learning.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Kopnina, H. Forsaking Nature? Contesting ‘Biodiversity’ through competing discourses of sustainability. JESD 2013, 7, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fančovičová, J.; Prokop, P. Plants have a chance: Outdoor educational programmes alter students’ knowledge and attitudes towards plants. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killerman, W. Biology education in Germany: Research into the effectiveness of different methods. IJSE 1996, 18, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P. ‘Loveable’ mammals and ‘lifeless’ plants: How children’s interest in common local organisms can be enhanced through observation of nature. IJSE 2005, 27, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morag, O.; Tal, T. Assessing learning in the outdoors with the field trip in natural environments (FiNE) framework. IJSE 2012, 34, 745–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.W.; Goulder, R.; Wheeler, P.; Scott, L.J.; Tobin, M.L.; Marsham, S. The value of fieldwork in Life and Environmental Sciences in the context of higher education: A case study in learning about biodiversity. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, T.; Alon, N.L.; Morag, O. Exemplary practices in field trips to natural environments. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 430–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, E.; Gilburn, A. The field course effect: Gains in cognitive learning in undergraduate biology students following a field course. J. Biol. Educ. 2012, 46, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Bogner, F. Cognitive achievements in identification skills. J. Biol. Educ. 2006, 40, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolpe, K.; Björklund, L. Seeing the wood for the trees: Applying the dual-memory system model to investigate expert teachers’ observational skills in natural ecological learning environments. IJSE 2012, 34, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, M.; Franklin, T. A review of research on school field trips and their value in education. IJESE 2014, 9, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-Ekeke, J. Relative effectiveness of expository and field study methods of teaching on students’ achievement in ecology. IJSE 2007, 20, 1869–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magntorn, O.; Helldén, G. Reading nature from a ‘bottom-up’ perspective. J. Biol. Educ. 2007, 41, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I.; Kuru, J. Outdoor activities as a basis for environmental responsibility. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, R.; Scott, G.W.; Scott, L.J. Students’ perception of biology fieldwork: The example of students undertaking a preliminary year at a UK university. IJSE 2013, 35, 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, T.; Morag, O. Reflective practice as a means for preparing to teach outdoors in an ecological garden. JSTE 2009, 20, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnicliffe, S.D.; Reiss, M. Building model of the environment: How do children see animals. J. Biol. Educ. 1999, 33, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontkanen, J.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Dillon, P.; Hartikainen-Ahia, A.; Åhlberg, M. Collaborative processes in species identification using an internet-based taxonomic resource. IJSE 2016, 38, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. The ability of A-level students to name plants. J. Biol. Educ. 2005, 39, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, V.D.I.; Scheiter, K.; Kühl, T.; Gemballa, S. Learning how to identify species in a situated learning scenario: Using dynamic-static visualizations to prepare students for their visit to the aquarium. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2011, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.W. Use of Internet resources in the biology lecture classroom. Amer. Biol. Teach. 2000, 62, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golick, D.A.; Heng-Moss, T.M.; Steckelberg, A.L.; Brooks, D.W.; Higley, L.G.; Fowler, D. Using web-based key character and classification instruction for teaching undergraduate students insect identification. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2013, 22, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Randler, C. Animal related activities as determinants of species knowledge. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2010, 6, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Strnad, R.L.; Bondell, H.D.; Kirby-Hathaway, T.; Moore, S.E. Role of significant life experiences in building environmental knowledge and behavior among middle school students. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.; Jørgensen, K.A. Children in nature: Sensory engagement and the experience of biodiversity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, B.B.; Brewer, C.A.; Berkowitz, A.R.; Borrie, W.T. Environmental literacy, ecological literacy, ecoliteracy: What do we mean and how did we get here? Ecosphere 2013, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Is environment ‘a city thing’ in China? Rural-urban differences in environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Connecting students to nature: How intensity of nature experience and student age influence the success of outdoor education programmes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I. Artkunskap och intresse för arter hos blivande lärare för grundskolan. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2012, 8, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, B.; Momsen, J.L. Attention ‘blinks’ differently for plants and animals. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, E.; Randler, C. Living animals in the classroom: A meta-analysis on learning outcome and a treatment-control study focusing on knowledge and motivation. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricsfalusy, V.; George, C.; Reed, M.G. Integrating problem- and project-based learning opportunities: Assessing outcomes of a field course in environment and sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, S.; Sperling, E.; Inwood, H. What’s growing on here? Garden-based pedagogy in a concrete jungle. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenika, I.; Moreau, T.; Lane, O.; Zhao, J. Sustainability education in a botanical garden promotes environmental knowledge, attitudes and willingness to act. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavas, B. Outdoor education in natural life park: An experience from Turkey. Sci. Educ. Int. 2011, 22, 152–160. Available online: http://www.icaseonline.net/sei/june2011/p6.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Subramaniam, K.; Asim, S.; Young Lee, E.; Koo, Y. Student teachers’ images of science introduction in informal settings: A focus on field pedagogy. JSTE 2018, 29, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.H.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerden, M.D.; Witt, P.A. The impact of direct and indirect experiences on the development of environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemart, A.L.; Lhoir, P.; Binard, F.; Descamps, C. An interactive multimedia dichotomous key for teaching plant identification. J. Biol. Educ. 2016, 50, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Jones, K.T.; Moreland, K. Differences in learning styles. Responsibilities and leadership professional development. CPA J. 2014, 84, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palmberg, I.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Jeronen, E.; Yli-Panula, E.; Persson, C. Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods for Species and Species Identification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195231

Palmberg I, Kärkkäinen S, Jeronen E, Yli-Panula E, Persson C. Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods for Species and Species Identification. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195231

Chicago/Turabian StylePalmberg, Irmeli, Sirpa Kärkkäinen, Eila Jeronen, Eija Yli-Panula, and Christel Persson. 2019. "Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods for Species and Species Identification" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195231

APA StylePalmberg, I., Kärkkäinen, S., Jeronen, E., Yli-Panula, E., & Persson, C. (2019). Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Most Efficient Teaching and Learning Methods for Species and Species Identification. Sustainability, 11(19), 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195231