Advancing the One Health Framework in EU Plant Protection Product Regulation: Challenges and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- -

- Reports, guidance, and scientific publications from relevant EU agencies: Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA), EFSA, ECHA, ECDC, and EMA.

- -

- International health and environmental organisations such as FAO, WHO, and UNEP.

- -

- Peer-reviewed articles and pilot project case studies.

3. Results

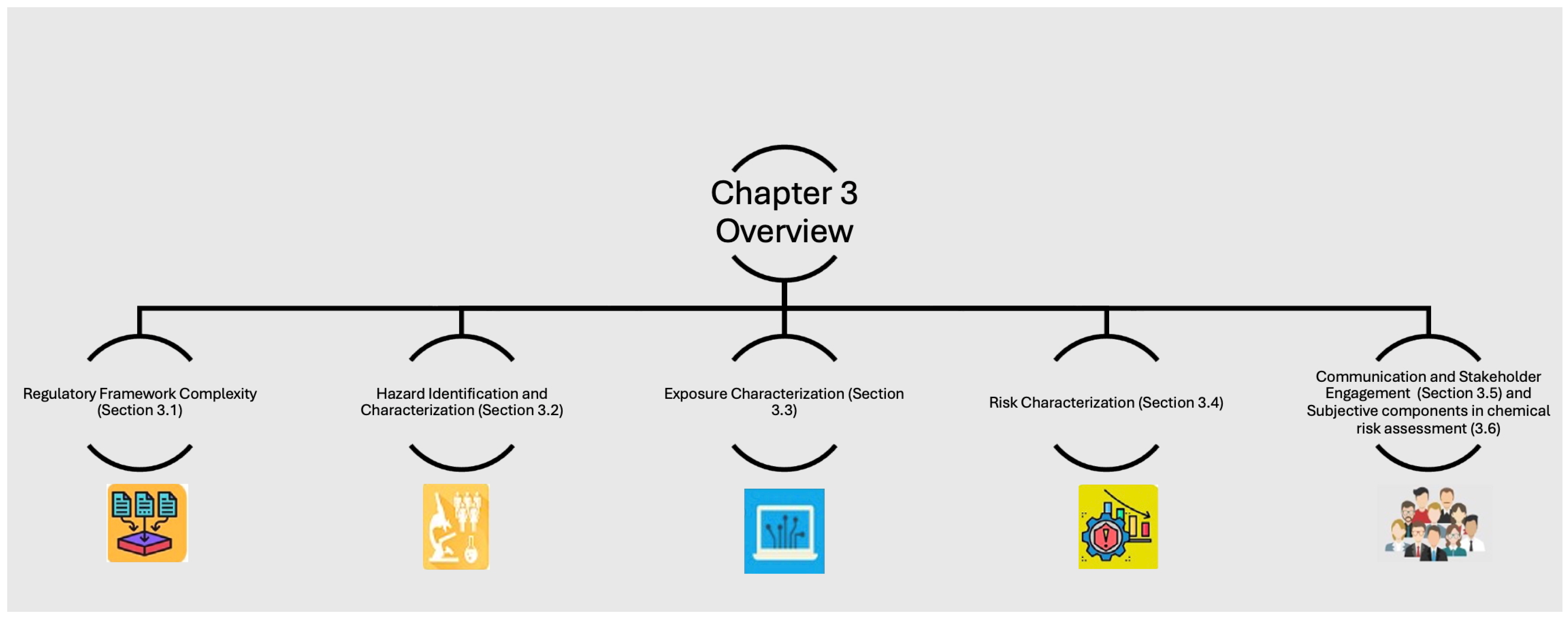

3.1. Complexity of the Legislative Framework

3.1.1. Regulatory Framework for Plant Protection Products

3.1.2. Evaluation and Authorisation of Plant Protection Products (PPPs) and Risk Management

3.1.3. Evaluation of Regulatory Effectiveness and Improvement Initiatives

3.1.4. Harmonised Risk Indicators and Data Criticality

3.2. Critical Issues Related to Hazard Identification and Characterisation

3.2.1. New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) Overview

3.2.2. European Case Studies

3.2.3. Regulatory Challenges

3.2.4. The Challenge of Integration of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) Within a One Health Framework

3.3. Critical Issues Related to Exposure Characterisation

3.3.1. Innovative Epidemiological Studies on Pesticide Exposure

3.3.2. Innovative Approaches in Exposure and Effect Assessment

3.4. Critical Issues Related to Risk Characterisation

3.5. Critical Issues Related to Risk Communication

3.5.1. Example 1—Exposure Management and Mitigation Measures

3.5.2. Example 2—The Case of Glyphosate and Uncertainty in Risk Assessment

3.5.3. One Health Approach and PPPs Public Perception of Risk

3.6. Subjective Components in Chemical Risk Assessment and the Need to (Re)Build Confidence in the Assessment Process

- -

- Risk perception plays a vital role in societal risk management and strongly influences how uncertainty and ambiguity are addressed [88].

- -

- Transformation within these processes requires trust, which in turn depends on transparency—ensuring stakeholders can understand system functioning, identify weaknesses, and see how these are or can be addressed [89].

- -

- Transparency must be coupled with a shared commitment among diverse stakeholders who align on common visions and values that are central to decision-making and strategy [89].

- -

- Behavioural and cultural factors are essential to the exposure assessment and risk management of plant protection products [90].

- -

- Clear communication of uncertainties inherent in exposure and effect assessment is paramount [91].

4. Discussion

- -

- Current regulatory systems for risk assessment face several challenges that must be addressed. These include the need to evaluate the cumulative risk of an increasing variety of chemicals and mixtures, the complexity of assessing diverse health effects such as endocrine disruption and neurotoxicity, and the emergence of new materials like nanoparticles in product formulations.

- -

- To address ethical and economic concerns, innovative methods [47,48,49,50,51]—including in vivo and in silico methods (e.g., quantitative structure–activity relationships, omics technologies, artificial intelligence, and automated processes)—have also been adopted for PPPs in toxicological assessments. While these advances enhance evaluation, they also demand new skills from assessors, increase the decision-making complexity, and introduce uncertainty, all of which impact the credibility of the process.

- -

- Ethical considerations are central to this evolution. The reduction demand in animal testing and the adoption of more humane, transparent, and precautionary approaches is aligned with the principles of sustainability and One Health [93].

- -

- To meet the ambitious EU objectives, the role of exposure science must also be strengthened. Currently, pesticide risk assessment in Europe is mainly hazard-driven, although guidelines and tools for chemical exposure assessment have evolved to meet the needs of specific policy areas.

- -

- Expert disagreement and scientific subjectivity influence perceptions of risk assessment credibility, particularly when inconsistent interpretations raise public concerns, as exemplified by controversies such as glyphosate, presented in Section 3.5.2 Example 2, for the case of glyphosate and uncertainty in risk assessment.

- -

- Public trust plays a pivotal role: confidence in science reduces perceived risks and boosts perceived benefits, while distrust in industry or conflicting information heightens risk perception. Confusion, conflicting messages, or lack of knowledge further amplify risk concerns. Although PPPs undergo rigorous risk evaluation, public opinions often emphasise environmental and health risks more than the benefits related to food safety and security [82,83].

- -

- To meet the EU’s ambitious risk reduction targets, it is essential to assess the effectiveness of mitigation measures, including the potential impact of new technologies and innovations. Improving how the effectiveness of these measures is addressed and calculated in specific contexts could help to minimise human and environmental exposure to PPPs.

- -

- To promote the effective use of PPPs, enhance communication, and bolster confidence in the entire risk assessment process, it is imperative to examine the behavioural and cultural factors, as well as risk perception assessments at contextual and territorial levels. Involving qualified professionals from the agricultural, forestry, livestock, and environmental sectors is essential to improve policy implementation and ensure an integrated approach according to the “One Health” principles and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Agronomists, farmers, and rural communities play a pivotal role in managing sustainable agricultural practices and safeguarding the environment and rural livelihoods [81]. Their participation is vital to the effectiveness of environmental policies and crucial to preventing rural depopulation and the higher social and environmental costs associated with land management, as highlighted in the most recent paper of Vos et al. (2025) [44], addressing the unresolved challenges between the “One Health” approach and the agricultural sector.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coghlan, S.; Coghlan, B.J.; Capon, A.; Singer, P. A bolder One Health: Expanding the moral circle to optimise health for all. One Health Outlook 2021, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Statement by European Union Agencies. Cross-Agency Knowledge for One Health Action. 2023. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-11/one-health-2023-joint-statement.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Joint Tripartite (FAO, OIE, WHO) and UNEP Statement on OHHLEP’s Definition of “One Health”; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-12-2021-tripartite-and-unep-support-ohhlep-s-definition-of-one-health (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Rietjens, I.M.; Zheng, L. Current and Emerging Issues in Chemical Food Safety. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 62, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, M.F.; Roth, N.; Aicher, L.; Faust, M.; Papadaki, P.; Marchis, A.; Calliera, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Andres, S.; Kühne, R.; et al. White paper on the promotion of an integrated risk assessment concept in European regulatory frameworks for chemicals. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015, 521–522, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueh, A.C. Sri Lanka: Impact Assessment Study of 2021 Ban on Conventional Pesticides and Fertilizers. 2022. Available online: https://eu-asean.eu/sri-lanka-impact-assessment-study-of-2021-ban-on-conventional-pesticides-and-fertilizers-2022/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nordhaus, T.; Shah, S. Sri Lanka, Organic Farming Went Catastrophically Wrong. Foreign Policy Magazine, 5 March 2022. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/05/sri-lanka-organic-farming-crisis/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Falkenberg, T.; Ekesi, S.; Borgemeister, C. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and One Health—A call for action to integrate. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2022, 53, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying Down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying Down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. Off. J. L 2002, 31, 1–24. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2002/178/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market and Repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC. Off. J. L 2009, 309, 1–50. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1107/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides. Off. J. L 2009, 309, 71–86. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/128/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Safety–EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/chapter/30.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/institutions-and-bodies/search-all-eu-institutions-and-bodies/european-food-safety-authority-efsa_en (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Van der Meulen, B.M.J. The Structure of European Food Law. Laws 2013, 2, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, T.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Chemical Food Safety in Europe Under the Spotlight: Principles, Regulatory Framework and Roadmap for Future Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR Lex: Commission Regulation (EU) No 283/2013 of 1 March 2013 Setting Out the Data Requirements for Active Substances, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/283/oj/eng (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- EUR Lex: Commission Regulation (EU) No 284/2013 of 1 March 2013 Setting Out the Data Requirements for Plant Protection Products, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/284/oj/eng (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Bullón Caro, C. Legal elements to operationalise One Health: From principles to practice. Res. Dir. One Health 2025, 3, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2009/127/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 amending Directive 2006/42/EC with regard to machinery for pesticide application. Off. J. L 2009, 310, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures, Amending and Repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. Off. J. L 2008, 353, 1–1355. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1272/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2022/2379 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 November 2022 on statistics on agricultural input and output, amending Commission Regulation (EC) No 617/2008 and repealing Regulations (EC) No 1165/2008, (EC) No 543/2009 and (EC) No 1185/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Directive 96/16/EC PE/37/2022/REV/1. Off. J. L 2022, 315, 1–29. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/2379/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Commission. REFIT—Making EU Law Simpler, More Efficient and Future-Proof. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/evaluating-and-improving-existing-laws/refit-making-eu-law-simpler-less-costly-and-future-proof_en (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- European Union. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Evaluation of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 on the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market and of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 on Maximum Residue Levels of Pesticides COM (2020) 208 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0208 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Parliament Resolution of 13 September 2018 on the Implementation of the Plant Protection Products Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 (2017/2128(INI)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2018-0356_EN.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Parliament Resolution of 16 January 2019 on the Union’s Authorisation Procedure for Pesticides (2018/2153(INI)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0023_EN.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the Transparency and Sustainability of the EU Risk Assessment in the Food Chain and Amending Regulations (EC) No 178/2002, (EC) No 1829/2003, (EC) No 1831/2003, (EC) No 2065/2003, (EC) No 1935/2004, (EC) No 1331/2008, (EC) No 1107/2009, (EU) 2015/2283 and Directive 2001/18/EC. Off. J. L 2019, 231, 1–28. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1381/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Your Europe. Registering Chemicals (REACH). Available online: https://europa.eu/youreurope/business/product-requirements/chemicals/registering-chemicals-reach/index_en.htm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Caldeira, C.; Farcal, R.; Moretti, C.; Mancini, L.; Rasmussen, K.; Rauscher, H.; Riego Sintes, J.; Sala, S. Safe and Sustainable by Design Chemicals and Materials—Review of Safety and Sustainability Dimensions, Aspects, Methods, Indicators, and Tools; EUR 30991 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-47560-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Safe and Sustainable by Design. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/industrial-research-and-innovation/chemicals-and-advanced-materials/safe-and-sustainable-design_en#documents (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Devos, Y.; Auteri, D.; de Seze, G.; Fabrega, J.; Heppner, C.; Rortais, A.; Hugas, M. Building a European Partnership for next generation, systems-based Environmental Risk Assessment (PERA). EFSA Support. Publ. 2022, 19, e200503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR Lex: Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council of October 2017 on Member State National Action Plans and on Progress in the Implementation of Directive 2009/128/EC on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides—COM(2017) 587 Final. Document 52017DC0587. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0587 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Parliament. Directive 2009/128/EC on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides European Implementation AssessementEPRS|European Par-liamentary Research Service. External Study. 2018. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/627113/EPRS_STU(2018)627113_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Court of Auditor. Special Report 05/2020: Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products: Limited Progress in Measuring and Reducing Risks. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?did=53001 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Council of European Union. Council Conclusions on the Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Experience Gained by Member States on the Implementation of National Targets Established in Their National Action Plans and on Progress in the Implementation of Directive 2009/128/EC on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides. 13441/20 AGRI 447 PESTICIDE 41 SEEDS 16 AGRILEG 157. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13441-2020-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Friends Earth. Joint Open Letter on the Need for a Strong Proposal on an EU Legislative Framework for Sustainable Food Systems. 2023. Available online: https://friendsoftheearth.eu/publication/open-letter-commission-president-must-stick-to-sustainable-food-system-law-timeline/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- EUR-Lex Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, ‘The European Green Deal’ COM/2019/640 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52019DC0640 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- EUR-Lex Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, ‘A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System’, COM/2020/381 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0381 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Eurostat. 2021 Methodology for Calculating Harmonised Risk Indicators for Pesticides Under Directive 2009/128/EC. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-manuals-and-guidelines/-/ks-gq-21-008 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- One Health Governance in the European Union, Publications Office of the European Union. 2024. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/8697309 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/1537 of 25 July 2023 Laying Down Rules for the Application of Regulation (EU) 2022/2379 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Statistics on the Use of Plant Protection Products to be Transmitted for the Reference Year 2026 During the Transitional Regime 2025–2027 and as Regards Statistics on Plant Protection Products Placed on the Market (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R1537 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Eurostat. ‘Pesticide Sales by Categorisation of Active Substances’, Eurostat Data Browser. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/AEI_PESTSAL_RSK/default/table?lang=en&category=agr.aei.aei_pes (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Shattuck, A.; Werner, M.; Mempel, F.; Dunivin, Z.; Galt, R. Global pesticide use and trade database (GloPUT): New estimates show pesticide use trends in low-income countries substantially underestimated. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 81, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; Alessandrini, M.; Trevisan, M.; Pii, Y.; Mazzetto, F.; Orzes, G.; Cesco, S. One Health approach: Addressing data challenges and unresolved questions in agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 977, 179312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennekou, S.H. Moving towards a holistic approach for human health risk assessment—Is the current approach fit for purpose? EFSA J. 2019, 17, e170711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Alvarez, F.; Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Binaglia, M.; Castoldi, A.F.; Chiusolo, A.; Crivellente, F.; Egsmose, M.; Fait, G.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate. EFSA J. 2023, 21, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaauboer, B.J.; Boobis, A.R.; Bradford, B.; Cockburn, A.; Constable, A.; Daneshian, M.; Edwards, G.; Garthoff, J.A.; Jeffery, B.; Krul, C.; et al. Considering new methodologies in strategies for safety evaluation. Toxicol. Vitr. 2016, 32, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Toropov, A.A.; Toropova, A.P.; Rallo, R.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J.; Kabir, M.M.; Benfenati, E. Optimal descriptors-based QSAR analysis of toxicity of organic compounds to Tetrahymena pyriformis. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2020, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelkonen, O.; Abass, K.; Parra Morte, J.M.; Panzarea, M.; Testai, E.; Rudaz, S.; Louisse, J.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Wolterink, G.; Jean-Lou, C.M.D.; et al. Metabolites in the regulatory risk assessment of pesticides in the EU. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1304885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, R.; Ellers, J.; Roelofs, D.; Vooijs, R.; Dijkstra, T.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; Hoedjes, K.M. Combining time-resolved transcriptomics and proteomics data for Adverse Outcome Pathway refinement in ecotoxicology. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. New approach methodologies for risk assessment using deep learning. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e221105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.P.; Aldrich, A.; Axelman, J.; Backhaus, T.; Brendel, S.; Dorronsoro, B.; Duquesne, S.; Focks, A.; Holz, S.; Knillmann, S.; et al. Building a European Partnership for next generation, systems-based Environmental Risk Assessment (PERA). EFSA Support. Publ. 2022, 19, 7546E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netherlands National Committee for the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes (NCad). Transition Programme for Innovation Without the Use of Animals (TPI). 2022. Available online: https://www.animalfreeinnovationtpi.nl (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Guidance on the use of read-across for chemical safety assessment in food and feed. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaunbrecher, V.; Beryt, E.; Parodi, D.; Telesca, D.; Doherty, J.; Malloy, T.; Allard, P. Has toxicity testing moved into the 21st century? A survey and analysis of perceptions in the field of toxicology. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 087024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, D.; Bharti, K.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, S.; Pathak, R.K.; Biosca Brull, J.; Sabuz, O.; García Vilana, S.; Kumar, V. Advancing human health risk assessment: The role of new approach methodologies. Front. Toxicol. 2025, 7, 1632941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. How Pesticides Impact Human Health and Ecosystems in Europe. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/how-pesticides-impact-human-health/how-pesticides-impact-human-health (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Levorato, S.; Medina, P.; Mohimont, L.; Solazzo, E.; Costanzo, V. Prioritisation of pesticides and target organ systems for dietary cumulative risk assessment based on the 2019–2021 moni-toring cycle. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntzani, E.E.; Chondrogiorgi, M.; Ntritsos, G.; Evangelou, E.; Tzoulaki, I. Literature review on epidemiological studies linking exposure to pesticides and health effects. EFSA Support. Publ. 2013, EN-497, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and Their Residues (PPR). Scientific Opinion of the PPR Panel on the follow-up of the findings of the External Scientific Report ‘Literature review of epidemiological studies linking exposure to pesticides and health effects’. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee; More, S.; Bampidis, V.; Benford, D.; Bragard, C.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.; Bennekou, S.H.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambr, C.; Machera, K.; et al. Scientific Committee guidance on appraising and integrating evidence from epidemiological studies for use in EFSA’s scientific assessments. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Guidance on Expert Knowledge Elicitation in Food and Feed Safety Risk Assessment. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkalec, Z.; Antignac, J.-P.; Bandow, N.; Béen, F.M.; Belova, L.; Bessems, J.; Le Bizec, B.; Brack, W.; Cano-Sancho, G.; Chaker, J.; et al. Innovative analytical methodologies for characterizing chemical exposure with a view to next-generation risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx-Stoelting, P.; Rivière, G.; Luijten, M.; Aiello-Holden, K.; Bandow, N.; Baken, K.; Cañas, A.; Castano, A.; Denys, S.; Fillol, C.; et al. A walk in the PARC: Developing and implementing 21st century chemical risk assessment in Europe. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-ToxRisk. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/681002/reporting (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Human Biomonitoring (HBM4EU). Available online: https://www.hbm4eu.eu (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, C. A review of cumulative risk assessment of multiple pesticide residues in food: Current status, approaches and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 10434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Bennekou, S.H.; Allende, A.; Bearth, A.; Casacuberta, J.; Castle, L.; Coja, T.; Crépet, A.; Halldorsson, T.; Hoogenboom, R.; et al. Statement on the use and interpretation of the margin of exposure approach. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Crivellente, F.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Pedersen, R.; Terron, A.; Wolterink, G.; Mohimont, L. Establishment of cumulative assessment groups of pesticides for their effects on the nervous system. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Hardy, A.; Benford, D.; Halldorsson, T.; Jeger, M.J.; Knutsen, K.H.; More, S.; Mortensen, A.; Naegeli, H.; Noteborn, H.; et al. Update: Use of the benchmark dose approach in risk assessment. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Craig, P.S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; et al. Cumulative dietary risk characterisation of pesticides that have acute effects on the nervous system. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Craig, P.S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; et al. Cumulative dietary risk characterisation of pesticides that have chronic effects on the thyroid. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Anastassiadou, M.; Castoldi, A.F.; Cavelier, A.; Coja, T.; Crivellente, F.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hooghe, W.; et al. Retrospective cumulative dietary risk assessment of craniofacial alterations by residues of pesticides. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, L.; Marazzini, M.; Kanadil, M.; Metruccio, F. Cumulative risk assessment methodology applied to non-dietary exposures: Developmental alterations in professional agricultural settings. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2025, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHER (Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks). Improvement of Risk Assessment in View of the Needs of Risk Managers and Policy Makers. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/environmental_risks/docs/scher_o_154.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Calliera, M.; Marchis, A.; Sacchettini, G.; Capri, E. Stakeholder consultations and opportunities for integrating socio behavioural factors into the pesticide risk analysis process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 2937–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Guidance to Provide Justifications as Referred in Point 1.5 of the Introduction of the Annexes of Regulations (EU) No 283/2013 and No 284/2013: Problem Formulation for Environmental Risk Assessment in the Context of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009. 2024. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/c4d6b7df-b7f9-4b3b-8ce5-b823ccdcf98c_en?filename=pesticides_ppp_app-proc_guide_horizontal_problem_formulation_era_en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Compendium of Conditions of Use to Reduce Exposure and Risk from Plant Protection Products. 2024. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/cdd9b6c4-29dc-4077-a118-3e51c0abeb80_en?filename=pesticides_ppp_app-proc_guide_horizontal_compendium_conditions_of_use_en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Calliera, M.; Di Guardo, A.; L’Astorina, A.; Polli, M.; Finizio, A.; Capri, E. Integrating Environmental and Social Dimensions with Science-Based Knowledge for a Sustainable Pesticides Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee; More, S.J.; Benford, D.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Bampidis, V.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Hern ndez-Jerez, A.F.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambr, C.; et al. Guidance on risk-benefit assessment of foods. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAPEA (Science Advice for Policy by European Academies). Workshop Report No.3: Risk Perception and the Acceptability of Human Exposure to Pesticides; SAPEA: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 112. 2015. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MonographVolume112-1.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Initiative ‘Ban Glyphosate and Protect People and the Environment from Toxic Pesticides’ Called on the Commission, Under Its Third Aim, ‘to Set EU-Wide Mandatory Reduction Targets for Pesticide Use, with a View to Achieving a Pesticide-Free Future’ European Citizen’s Initiative. Available online: https://europa.eu/citizens-initiative/_en (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Schwientek, M.; Rgner, H.; Haderlein, S.B.; Schulz, W.; Wimmer, B.; Engelbart, L.; Huhn, C. Glyphosate contamination in European rivers not from herbicide application? Water Res. 2024, 263, 122140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, N.; Malmfors, T.; Slovic, P. Intuitive toxicology: Expert and lay judgments of chemical risks. Risk Anal. 1992, 12, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearth, A.; Roth, N.; Wilks, M.F.; Siegrist, M. Intuitive toxicology in the 21st century-Bridging the perspectives of the public and risk assessors in Europe. Risk Anal. 2024, 44, 2348–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campling, P.; Joris, I.; Calliera, M.; Capri, E.; Marchis, A.; Kuczyńska, A.; Vereijken, T.; Majewska, Z.; Belmans, E.; Borremans, L.; et al. A multi-actor, participatory approach to identify policy and technical barriers to better farming practices that protect our drinking water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO—European Health Observatory. Trust and Transformation: Five Policy Briefs by the Observatory and WHO/Europe in Support of the Tallinn Conference. 2023. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/themes/observatory-programmes/governance/tallinn-conference-2023 (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Advancing Behavioural and Cultural Insights for Health Through Engagement with Experts: Report of the Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural and Cultural Insights, Copenhagen, Denmark, 8–9 February 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376929 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Guidance on Uncertainty Analysis in Scientific Assessments. EFSA J. 2018, 16, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzwaer, S.; de Coen, W.; Heuer, O.; Marnane, I.; Vidal, A. The framework for action of the Cross-agency One Health Task Force. One Health 2024, 19, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.H. Human testing of pesticides: Ethical and scientific considerations. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Challenge | Ongoing/Emerging Initiatives |

|---|---|

| Cumulative Risk Assessment | Development of cumulative risk assessment methodologies; EFSA guidance on dietary exposure (CRA); refinement techniques such as Expert Knowledge Elicitation (EKE) for uncertainty analysis |

| Exposure Characterisation | Continuous updates by EFSA on exposure assessment methods; harmonisation of data collection related to exposure sources and vulnerable populations |

| Adoption of NAMs (New Approach Methodologies) | EFSA’s Partnership for Environmental Risk Assessment (PERA); implementation of in vitro and in silico assays; omics and AI technologies; European pilot projects; regulatory validation challenges |

| Public Trust and Communication | Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 enhancing transparency; inclusive stakeholder engagement; risk communication strategies to build trust and manage risk perception |

| Methodological Complexity and Data Gaps | Initiatives for harmonised scientific assessments; simplification efforts such as “one substance, one assessment”; continuous updating of evaluation methodologies aligned with evidence |

| Key Point | Brief Description | Challenge for One Health Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Legislative Framework | The EU has a robust, multilayered legislative framework protecting human, animal, and environmental health through regulations and directives for PPPs. Directive 2009/128/EC promotes integrated pest management and pesticide reduction, balancing productivity and sustainability. | Regulatory inertia slows cross-sector coordination, hindering integrated One Health responses and limiting advancements in agricultural practice. |

| Harmonised Risk Indicators | Harmonised risk indicators and data collections rely on hazard-based metrics that miss real exposure and risks. | Hazard-based focus limits capturing complex human–environment interactions that are essential to understanding One Health impacts. |

| Innovative Methodologies (NAMs) | New approaches (in vitro, in silico, omics, AI) promise better hazard identification and reduced animal testing but require validation. | Slow regulatory acceptance and validation delay the integration of innovative science that is necessary for One Health. |

| Exposure Characterisation | PPP exposure pathways are complex with uncertainties, requiring improved cumulative risk assessment methods. | Scientific and data gaps hamper accurate, holistic exposure assessment across human, animal, and environmental health domains. |

| Toward One Health | Legislative and scientific landscapes are evolving toward One Health, requiring multidisciplinary collaboration and adaptive governance. | Institutional silos, resource constraints, and policy fragmentation impede fully integrated transdisciplinary One Health action. |

| Communication | Clear and accessible communication supports the One Health approach, enhancing awareness, collaboration, and transparency in PPP risk assessment. | Effective, transparent communication across diverse stakeholders remains challenging, especially in conveying scientific findings to foster trust and coordinated action in One Health contexts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calliera, M.; Capri, E.; Suciu, N.A.; Trevisan, M. Advancing the One Health Framework in EU Plant Protection Product Regulation: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060200

Calliera M, Capri E, Suciu NA, Trevisan M. Advancing the One Health Framework in EU Plant Protection Product Regulation: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060200

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalliera, Maura, Ettore Capri, Nicoleta Alina Suciu, and Marco Trevisan. 2025. "Advancing the One Health Framework in EU Plant Protection Product Regulation: Challenges and Opportunities" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060200

APA StyleCalliera, M., Capri, E., Suciu, N. A., & Trevisan, M. (2025). Advancing the One Health Framework in EU Plant Protection Product Regulation: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060200