Investigation of Combined Toxic Metals, PFAS, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Essential Elements in Chronic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

Overview of Chronic Kidney Disease

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection and Study Design

2.2. Glomerular Filtration Rate, Essential Elements, Metals, PFAS, and Volatile Organic Compounds Quantification

2.2.1. eGFR Calculation

2.2.2. Laboratory Analyses

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Handling of Missing Data Using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equation (MICE)

2.3.2. Descriptive Statistics

2.3.3. Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR)

2.3.4. Weighted Quantile Sum Regression (WQSR)

2.3.5. Quantile G-Computation

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Overview of Participants by Age, Sex, and Ethnicity

3.2. Pearson Correlation Matrix of Variables of Exposure and Outcome Variables Interest

3.3. BKMR Analysis

3.3.1. Posterior Inclusion Probabilities (PIPs)

3.3.2. Hierarchical BKMR Results for Posterior Inclusion Probabilities

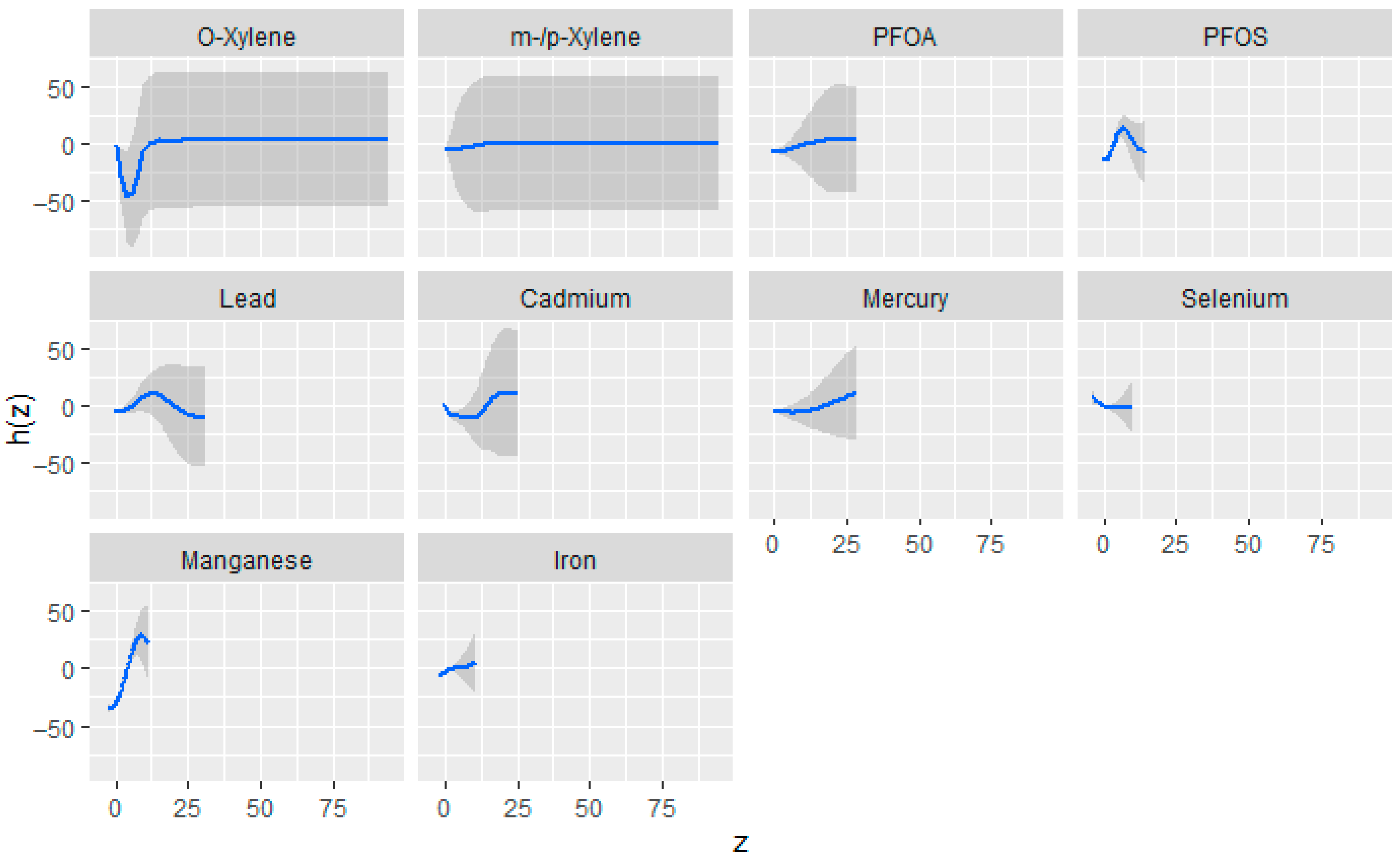

3.3.3. Univariate Association of Toxic Exposures Metals, VOCs, PFAS Compounds, and Essential Elements with eGFR

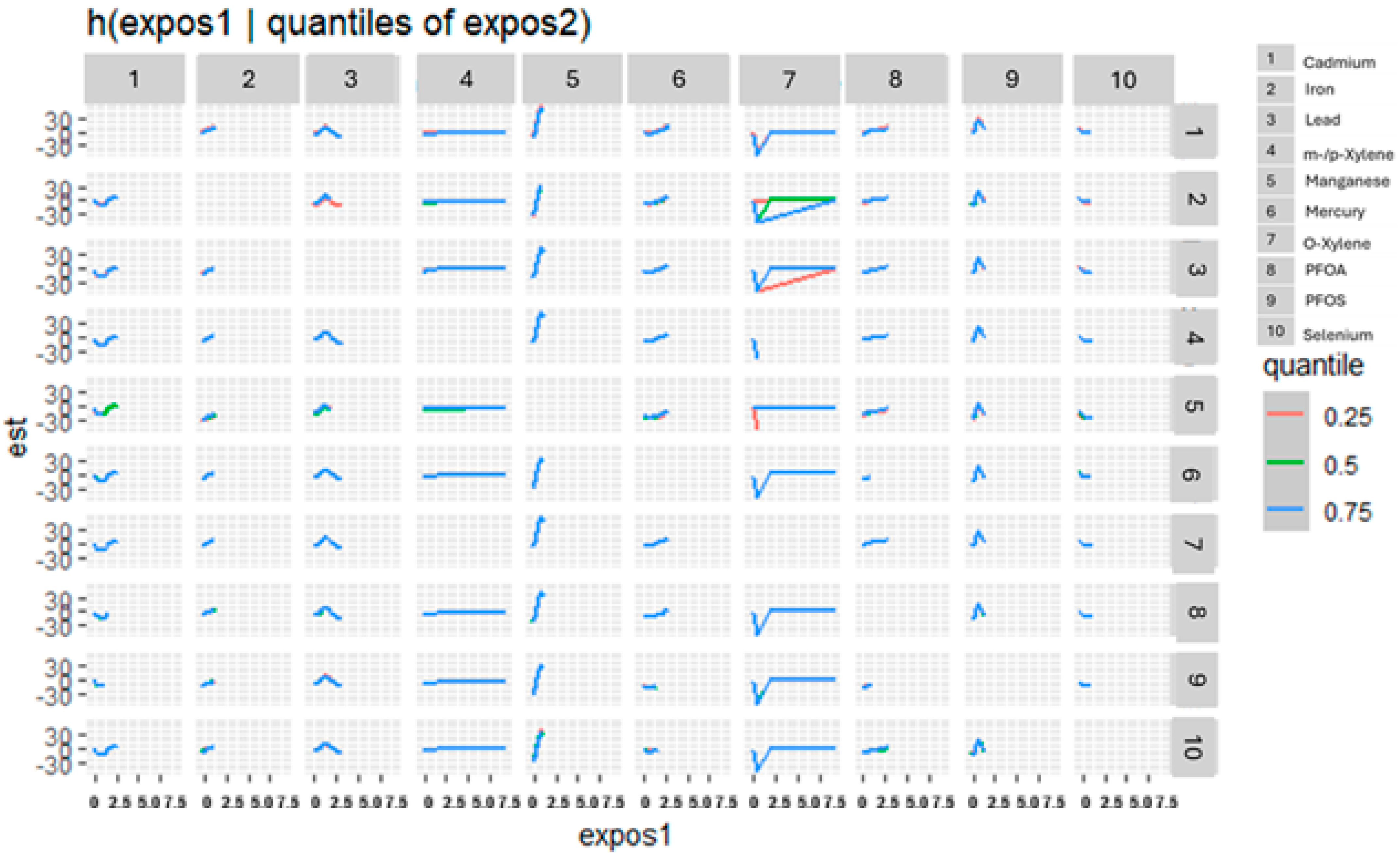

3.3.4. Bivariate Exposure–Response Relationships Between Toxic Exposures and eGFR

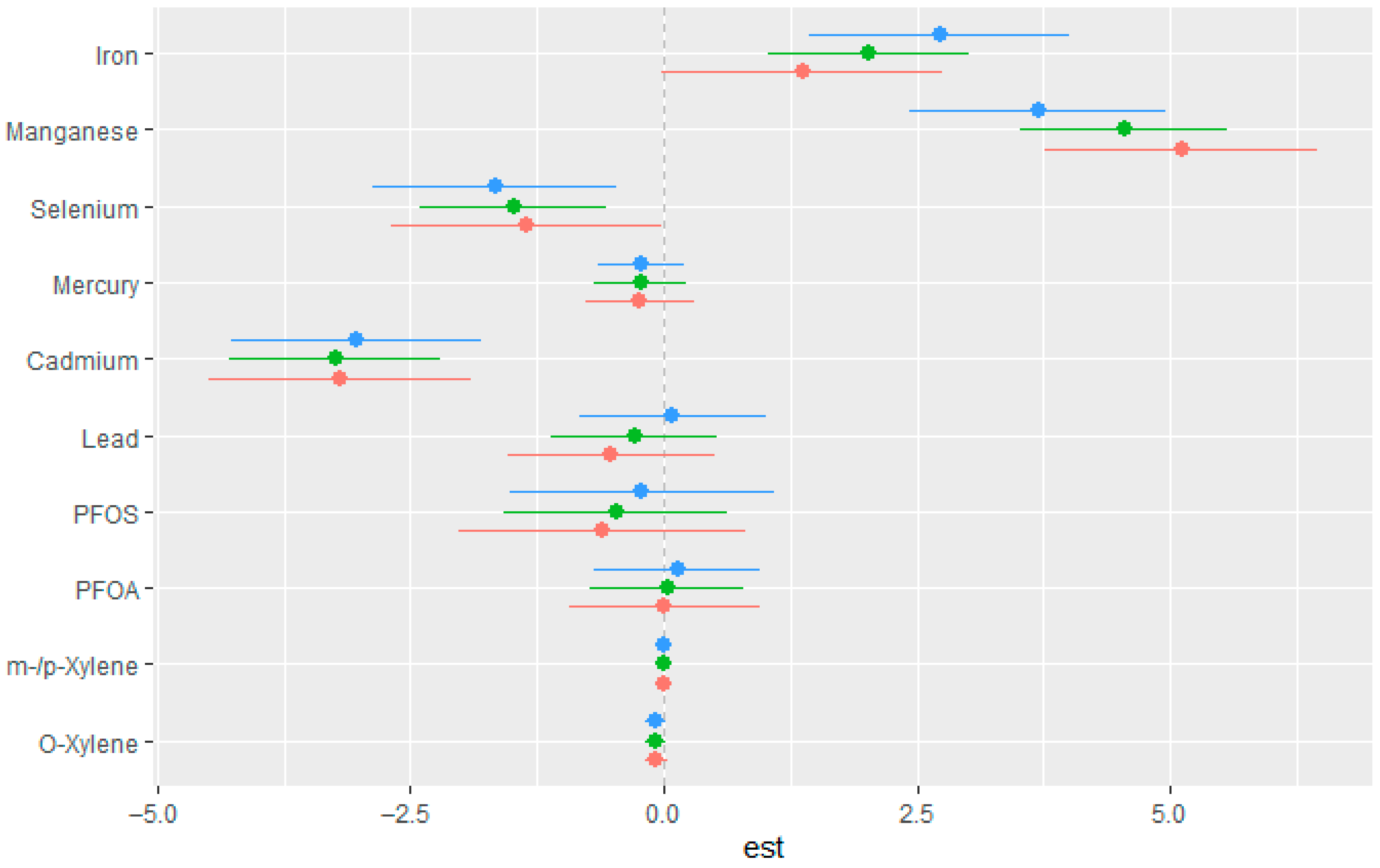

3.3.5. Single-Variable Effects of Exposures on eGFR

3.3.6. Single-Variable Interaction Terms of Exposures

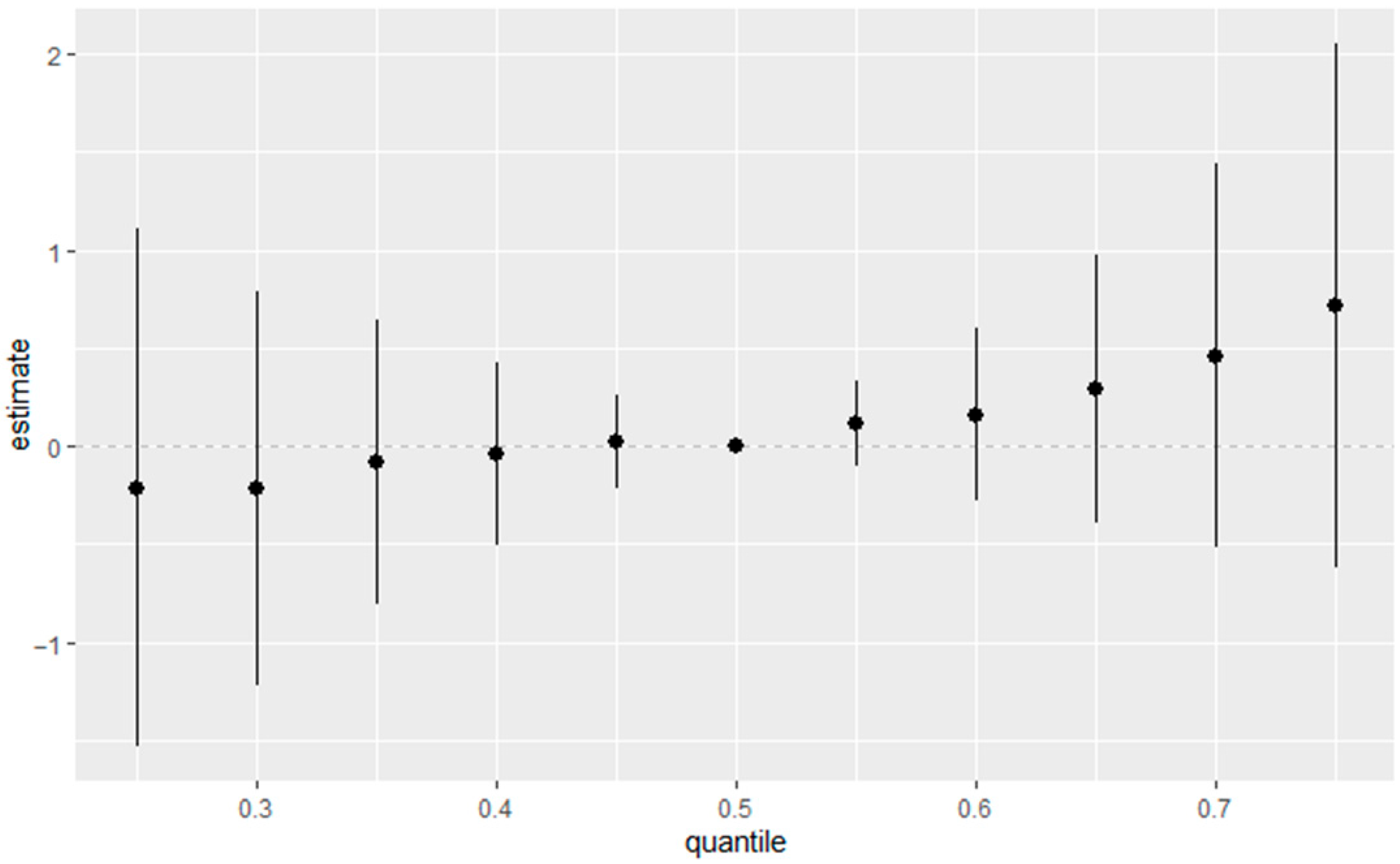

3.3.7. Overall Exposure Effect of All Exposures on eGFR

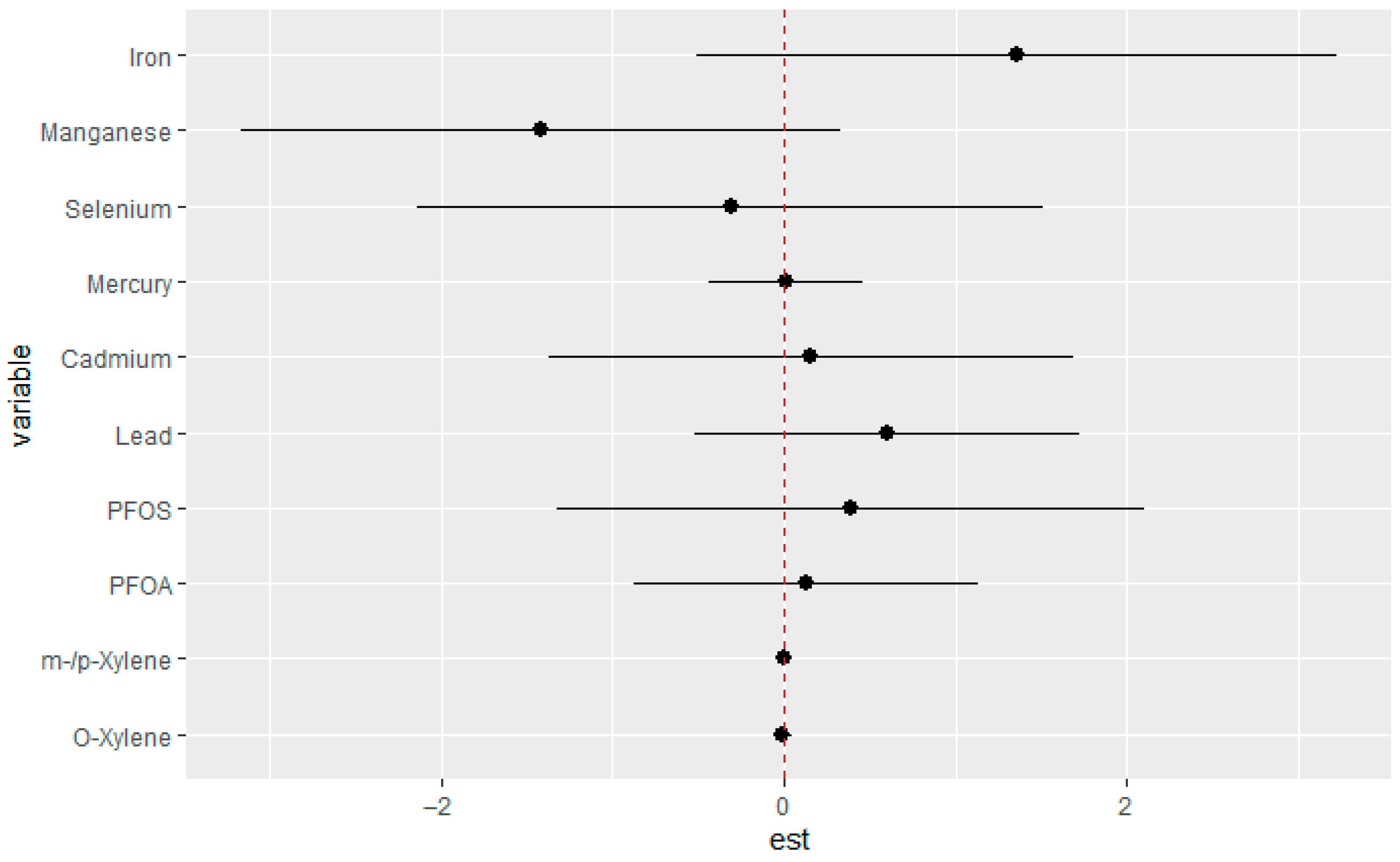

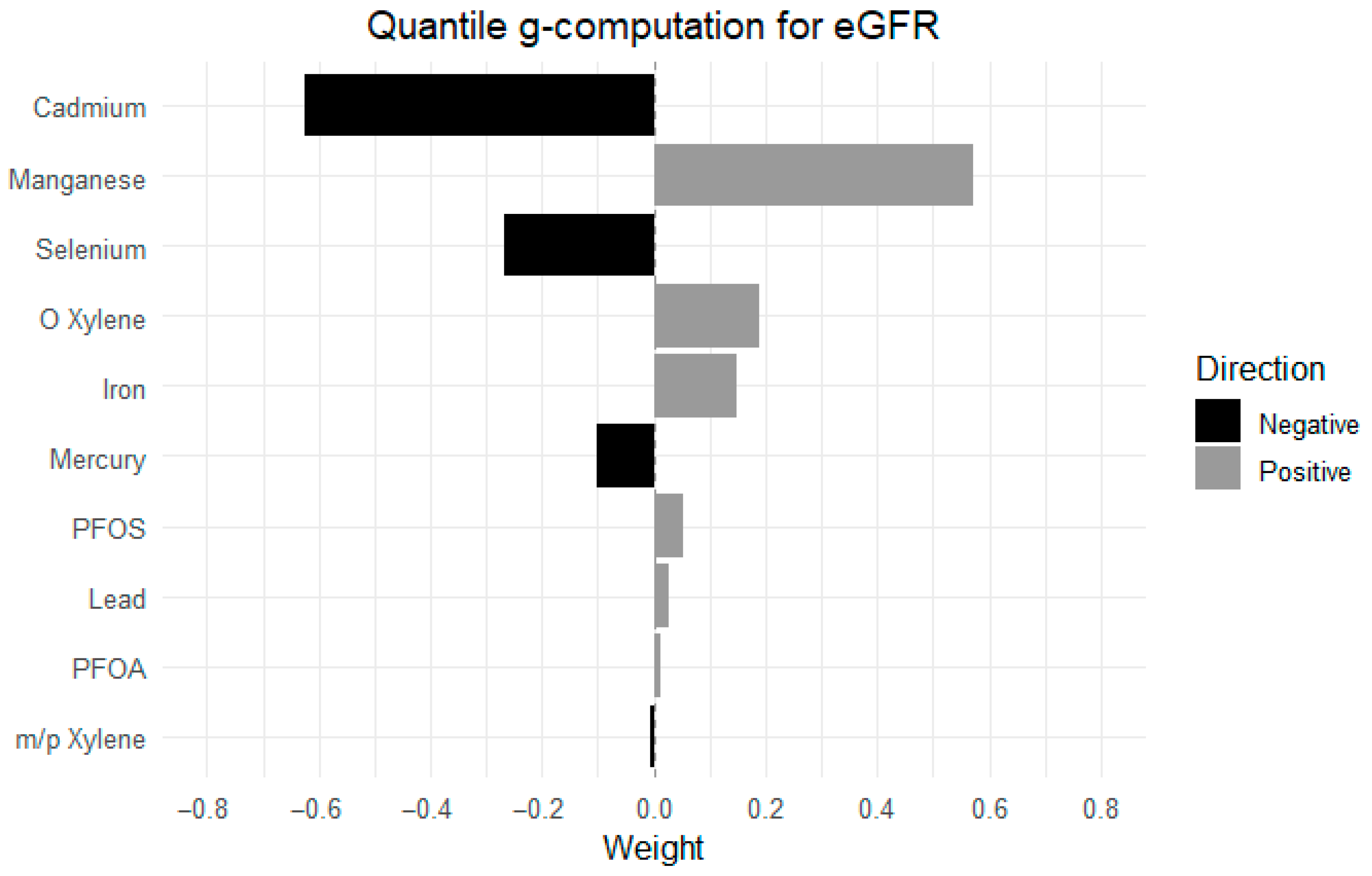

3.4. Quantile G-Computation Results

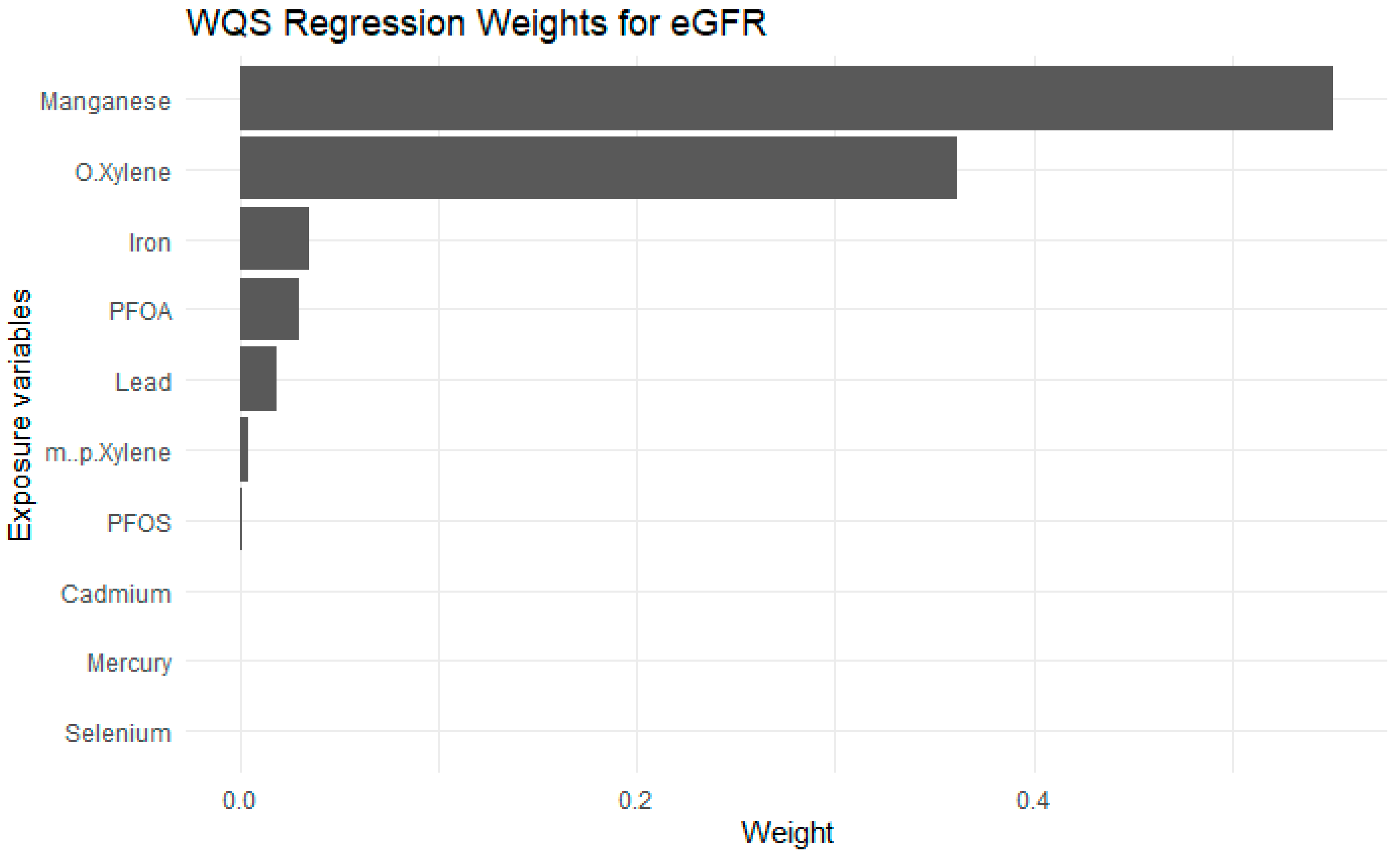

3.5. Weighted Quantile Sum Regression (WQSR)

4. Discussion

- Strengths and Limitations

- Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romagnani, P.; Agarwal, R.; Chan, J.C.N.; Levin, A.; Kalyesubula, R.; Karam, S.; Nangaku, M.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Anders, H.-J. Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, E.M.; Greenwood, S.A.; Müller, R.-U. The Importance of Lifestyle Interventions in the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Dial. 2023, 3, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, K.J.; Kovesdy, C.; Langham, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Jha, V.; Zoccali, C. A Single Number for Advocacy and Communication—Worldwide More Than 850 Million Individuals Have Kidney Diseases. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 1803–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2023; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/kidney-disease/php/data-research/index.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Raghavendra, M.; Vidya, M. Functions of Kidney & Artificial Kidneys. Int. J. Innov. Res. 2013, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2012, 379, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2021, 398, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, P.; Remuzzi, G.; Glassock, R.; Levin, A.; Jager, K.J.; Tonelli, M.; Massy, Z.; Wanner, C.; Anders, H.-J. Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, R. Glomerulonephritis Contributing to Chronic Kidney Disease. Urol. Nephrol. Open Access J. 2017, 5, 00179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, C.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Harris, P.C.; Horie, S.; Peters, D.J.M.; Torres, V.E. Polycystic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Donnan, P.T.; Bell, S.; Guthrie, B. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Induced Acute Kidney Injury in the Community Dwelling General Population and People with Chronic Kidney Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J.; Dissanayake, C.B. Factors Affecting the Environmentally Induced, Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Aetiology in Dry Zonal Regions in Tropical Countries—Novel Findings. Environments 2019, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozier, M.; Turcios-Ruiz, R.M.; Noonan, G.; Ordunez, P. Chronic Kidney Disease of Nontraditional Etiology in Central America: A Provisional Epidemiologic Case Definition for Surveillance and Epidemiologic Studies. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2016, 40, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Levin, A.; Coresh, J.; Rossert, J.; de Zeeuw, D.; Hostetter, T.H.; Lameire, N.; Eknoyan, G. Definition and Classification of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Position Statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, X. Molecular Mechanisms of Metal Toxicity and Carcinogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 222, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruna, I.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Association of Combined Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Metals with Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, C.; Kazemi, M.; Cheng, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaei, A.; Taheri, E.; Moradi, S. Associations between Exposure to Heavy Metals and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-J.; Hung, C.-H.; Wang, C.-W.; Tu, H.-P.; Li, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Kuo, C.-H. Associations Among Heavy Metals and Proteinuria and Chronic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinleye, A.; Oremade, O.; Xu, X. Exposure to Low Levels of Heavy Metals and Chronic Kidney Disease in the U.S. Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0288190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, B.N.; Badders, A.N.; Costacou, T.; Arthur, J.M.; Innes, K.E. Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Kidney Function in Chronic Kidney Disease, Anemia, and Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncob, C. The Role of Perfluorinated Compound Pollution in the Development of Acute and Chronic Kidney. In Nephrology and Public Health Worldwide; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 199, p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Yan, S.; Wang, P.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cui, J.; Liang, Y.; Ren, S.; Gao, Y. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Exposure in Relation to the Kidneys: A Review of Current Available Literature. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanifer, J.W.; Stapleton, H.M.; Souma, T.; Wittmer, A.; Zhao, X.; Boulware, L.E. Perfluorinated Chemicals as Emerging Environmental Threats to Kidney Health: A Scoping Review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, N.; Gong, Y.; Shi, W.; Wang, X. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analyses Reveal Perfluorooctanoic Acid-Induced Kidney Injury by Interfering with PPAR Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michanowicz, D.R.; Dayalu, A.; Nordgaard, C.L.; Buonocore, J.J.; Fairchild, M.W.; Ackley, R.; Schiff, J.E.; Liu, A.; Phillips, N.G.; Schulman, A.; et al. Home Is Where the Pipeline Ends: Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Present in Natural Gas at the Point of the Residential End User. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10258–10268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.F.; Lee, S.C.; Ho, W.K.; Blake, D.R.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.S.; Ho, S.S.H.; Fung, K.; Louie, P.K.K.; Park, D. Vehicular Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from a Tunnel Study in Hong Kong. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 7491–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gouw, J.; Warneke, C. Measurements of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Earth’s Atmosphere Using Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass Spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007, 26, 223–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, A.; Srivastava, A. Ambient Air Non-Methane Volatile Organic Compound (NMVOC) Study Initiatives in India—A Review. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana-Lilia, G.Y.; Kazimierz, W.; Elva-Leticia, P.L.; Katarzina, W.; Gloria, B. Occupational Exposure to Toluene and Its Possible Causative Role in Renal Damage Development in Shoe Workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 79, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.K.; Lin, Y.C.; Shih, T.S.; Chiung, Y.M. Effects of Occupational Exposure to 1,4-Dichlorobenzene on Hematologic, Kidney, and Liver Functions. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, M.; Rutkowski, B.; Dębska-Ślizień, A. Vitamins and Microelement Bioavailability in Different Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delipavlova, R.; Deneva, T.; Davcheva, D. The Trinity of Essential Trace Elements (TEs) Imbalance, Oxidative Stress (OS) and Inflammatory State in Chronic Kidney Disease and Hemodialysis (HD) Patients: Vicious Triad for Disease Progression and Outcomes. Knowl.-Int. J. 2024, 62, 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, A. Trace elements in patients with chronic kidney disease. In Chronic Renal Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 429–439. [Google Scholar]

- Filler, G.; Qiu, Y.; Kaskel, F.; McIntyre, C.W. Principles Responsible for Trace Element Concentrations in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Nephrol. 2021, 96, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, H.; Furuya, R.; Kaneko, M.; Nakagami, D.; Ishino, Y.; Kitamoto, S.; Omata, K.; Yasuda, H. Clinical Significance of Trace Element Zinc in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yin, Z.; Lv, Y.; Luo, J.; Shi, W.; Fang, J.; Shi, X. Plasma Element Levels and Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease in Elderly Populations (≥90 Years Old). Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Methods; NHANES 2017–2018. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/labmethods.aspx?BeginYear=2017 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Azur, M.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Frangakis, C.; Leaf, P.J. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What Is It and How Does It Work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobb, J.F.; Valeri, L.; Claus Henn, B.; Christiani, D.C.; Wright, R.O.; Mazumdar, M.; Godleski, J.J.; Coull, B.A. Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression for Estimating the Health Effects of Multi-Pollutant Mixtures. Biostatistics 2015, 16, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobb, J.F.; Claus Henn, B.; Valeri, L.; Coull, B.A. Statistical Software for Analyzing the Health Effects of Multiple Concurrent Exposures via Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbode, O.L.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Combined Effects of Arsenic, Cadmium, and Mercury with Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Insights from the All of Us Research Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafoggia, M.; Breitner, S.; Hampel, R.; Basagaña, X. Statistical Approaches to Address Multi-Pollutant Mixtures and Multiple Exposures: The State of the Science. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetunji, A.G.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Investigating the Interplay of Toxic Metals and Essential Elements in Liver Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetunji, A.G.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Investigating the Interplay of Toxic Metals and Essential Elements in Cardiovascular Disease. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mula-Abed, W.-A.S.; Al Rasadi, K.; Al-Riyami, D. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR): A Serum Creatinine-Based Test for the Detection of Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Impact on Clinical Practice. Oman Med. J. 2012, 27, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckon, W.N.; Parkins, C.; Maximovich, A.; Giarrosso, J. A General Approach to Modeling Biphasic Relationships. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. The Relationship between Typical Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Kidney Disease. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommar, J.N.; Svensson, M.K.; Björ, B.M.; Elmståhl, S.I.; Hallmans, G.; Lundh, T.; Skerfving, S.; Bergdahl, I.A. End-Stage Renal Disease and Low-Level Exposure to Lead, Cadmium and Mercury: A Population-Based, Prospective Nested Case-Referent Study in Sweden. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A.P.; Buckley, J.P.; O’Brien, K.M.; Ferguson, K.K.; Zhao, S.; White, A.J. A Quantile-Based g-Computation Approach to Addressing the Effects of Exposure Mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 047004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Tang, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Synergistic Interaction of Hypertension and Hyperhomocysteinemia on Chronic Kidney Disease: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019, 21, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, D.B.; Bobb, J.F.; Claus Henn, B.; Coull, B.A. A Permutation Test-Based Approach to Strengthening Inference on the Effects of Environmental Mixtures: Comparison between Single-Index Analytic Methods. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 087010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-J.; Chen, J.-L.; Jiang, W.-D.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L.; Wu, P.; Zhou, X.-Q. Influences of Five Dietary Manganese Sources on Growth, Feed Utilization, Lipid Metabolism, Antioxidant Capacity, Inflammatory Response and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Yellow Catfish Intestine. Front. Physiol. 2023, 566, 739190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.T.; Choi, D.S.; Park, C.H.; Heo, G.Y.; Kim, H.W.; Han, S.H.; Yoo, T.-H.; Kang, S.-W. Dietary Manganese Intake and Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease: Insights from the UK Biobank Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39 (Suppl. S1), gfae069-0502-1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Liu, M.; Yang, S.; Xiang, H.; Gan, X.; Ye, Z.; He, P.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Association of Dietary Manganese Intake with New-Onset Chronic Kidney Disease in Participants with Diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 18, 103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.-Y.; Wang, V.-S.; Wang, H.-Y.; Cheng, K.-Y.; Hwang, B.-F.; Bao, B.-Y.; Wang, P.-C. Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Kidney Dysfunction in Thin Film Transistor Liquid Crystal Display (TFT-LCD) Workers. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 178, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a) | ||||||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Lead (ng/mL) | 1.06 (1.35) | 0.00 | 42.00 | |||

| Cadmium (ng/mL) | 0.25 (0.59) | 0.00 | 13.00 | |||

| Mercury (ng/mL) | 1.07 (2.33) | 0.00 | 64.00 | |||

| PFOS (ng/mL) | 6.51 (7.74) | 0.14 | 104.90 | |||

| PFOA (ng/mL) | 1.71 (1.82) | 0.14 | 52.87 | |||

| O-Xylene (ng/mL) | 0.08 (2.27) | 0.02 | 119.00 | |||

| m-/p-Xylene (ng/mL) | 0.36 (12.30) | 0.02 | 649.00 | |||

| Selenium (ng/mL) | 186.30 (26.34) | 85.00 | 454.00 | |||

| Manganese (ng/mL) | 10.32 (3.77) | 2.00 | 52.00 | |||

| Iron (ng/mL) | 87.28 (36.62) | 10.00 | 476.00 | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 98.63 (35.00) | 3.44 | 313.44 | |||

| (b) | ||||||

| Variables | Description | Frequency | Mean | Percentage | 95% CI | |

| Gender (yrs) | 9254 | |||||

| Male | 4557 | 37.43 | 49.24 | 36.38 | 38.48 | |

| Female | 4697 | 39.38 | 50.76 | 38.12 | 40.64 | |

| Ethnicity | 9254 | |||||

| Mexican American | 1367 | 14.77 | 27.50 | 31.13 | ||

| Other Hispanic | 820 | 8.86 | 31.77 | 35.60 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3150 | 34.04 | 40.00 | 43.34 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2115 | 22.85 | 34.68 | 36.98 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1168 | 12.62 | 35.93 | 39.93 | ||

| Other Races—Including Multi-Racial | 634 | 6.85 | 29.59 | 37.36 | ||

| BMI | Male | 8878 | 27.45 | 26.91 | 28.00 | |

| Female | 8931 | 27.45 | 27.21 | 28.55 | ||

| Alcohol Use | 5130 | |||||

| Yes | 4545 | 88.60 | ||||

| No | 585 | 11.49 | ||||

| Exposure Variables | PIP |

|---|---|

| O-Xylene | 0.7224 |

| m-/p-Xylene | 0.5392 |

| PFOA | 0.2840 |

| PFOS | 1.0000 |

| Lead | 0.4880 |

| Cadmium | 1.0000 |

| Mercury | 0.0904 |

| Selenium | 1.0000 |

| Manganese | 1.0000 |

| Iron | 0.9852 |

| Exposure Variables | Group | Group PIP | Cond PIP |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-Xylene | 1 | 0.982 | 0.8195519 |

| m-/p-Xylene | 1 | 0.982 | 0.1804481 |

| PFOA | 2 | 1.000 | 0.0000000 |

| PFOS | 2 | 1.000 | 1.0000000 |

| Lead | 3 | 1.000 | 0.0000000 |

| Cadmium | 3 | 1.000 | 1.0000000 |

| Mercury | 3 | 1.000 | 0.0000000 |

| Selenium | 4 | 1.000 | 0.0000000 |

| Manganese | 4 | 1.000 | 1.0000000 |

| Iron | 4 | 1.000 | 0.0000000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adetunji, A.G.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Investigation of Combined Toxic Metals, PFAS, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Essential Elements in Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060202

Adetunji AG, Obeng-Gyasi E. Investigation of Combined Toxic Metals, PFAS, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Essential Elements in Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060202

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdetunji, Aderonke Gbemi, and Emmanuel Obeng-Gyasi. 2025. "Investigation of Combined Toxic Metals, PFAS, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Essential Elements in Chronic Kidney Disease" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060202

APA StyleAdetunji, A. G., & Obeng-Gyasi, E. (2025). Investigation of Combined Toxic Metals, PFAS, Volatile Organic Compounds, and Essential Elements in Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060202