Exploring Trust in Health Insurers: Insights from Enrollees’ Perceptions and Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do enrollees perceive health insurers in general?

- What are the experiences of enrollees and their relatives with health insurers?

- What is the role of the media in enrollees’ perceptions of health insurers?

- What do enrollees perceive as the tasks and roles of health insurers in the health care system?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Interview Results

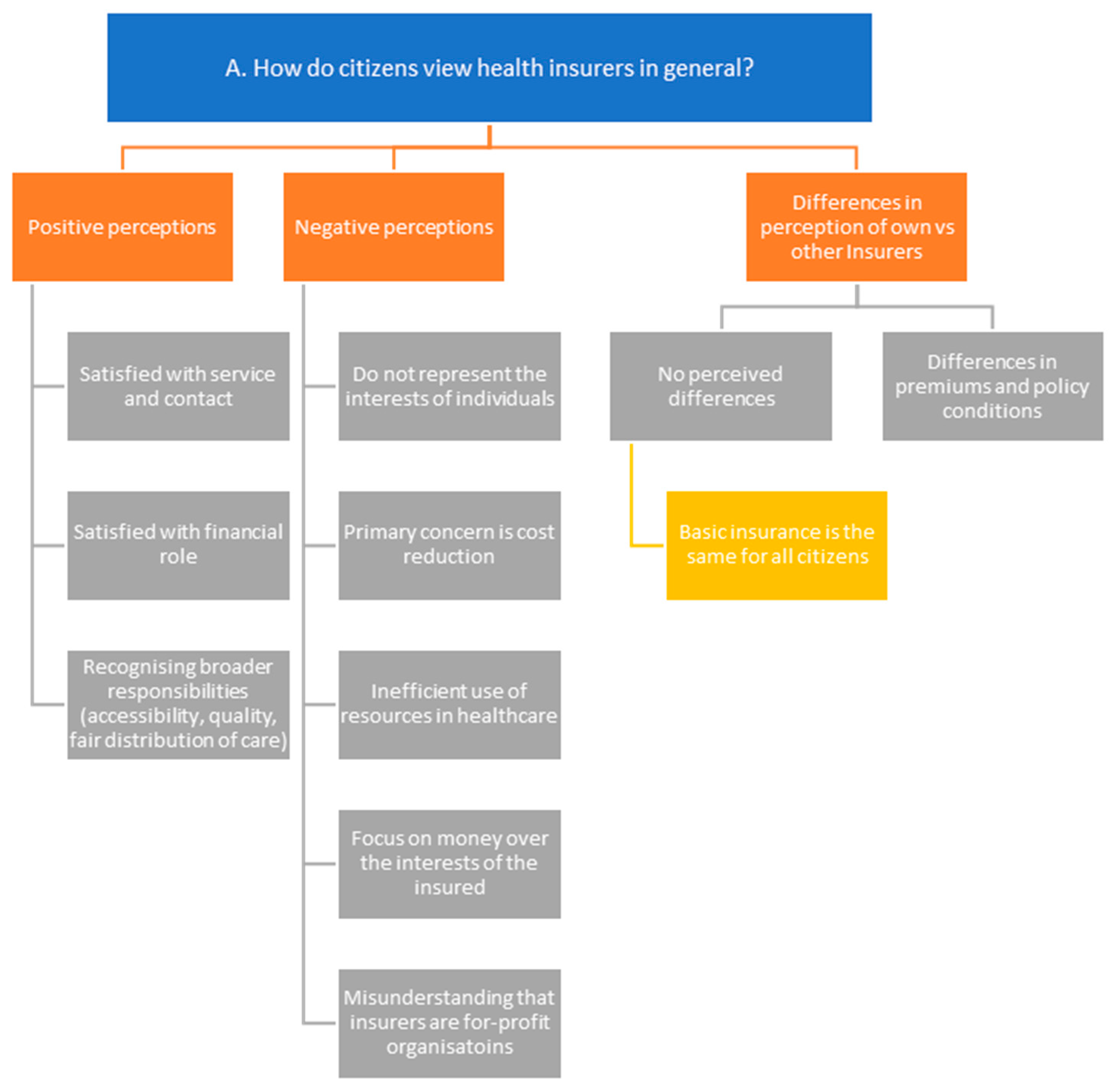

3.2.1. How Do Citizens View Health Insurers in General?

“I also find the human aspect important. You know, that individual circumstances are taken into account. Because people are biological and biology is not an exact science, sometimes there are situations that fall outside the norm. And it’s nice to put everything into the system, but sometimes there’s no box that person fits into, you know, and then you have to tweak things a bit, and I find that willingness to do so important as well.”Participant #3

“I think they have far too much power and that it’s all about money. I also believe that their privatisation, which happened years ago, was a bad decision (…) It’s really all about money. And people who need medication always have to... Well, at the moment, it’s a hot issue with medications being unavailable. People suffer too much from this. I think it’s not focused on care, which is what it should be about.”Participant #12

“Operationally, they do good work and facilitate the flow of money. I don’t have much trust in their interventions. Look, they are ultimately all companies that need to make a profit and have shareholders, and I think that shareholders are prioritised over patients.”Participant #15

“I’ve never wondered about it. It seemed so illogical to me that they would make a profit, that I’ve never questioned it. But do they?”Participant #11

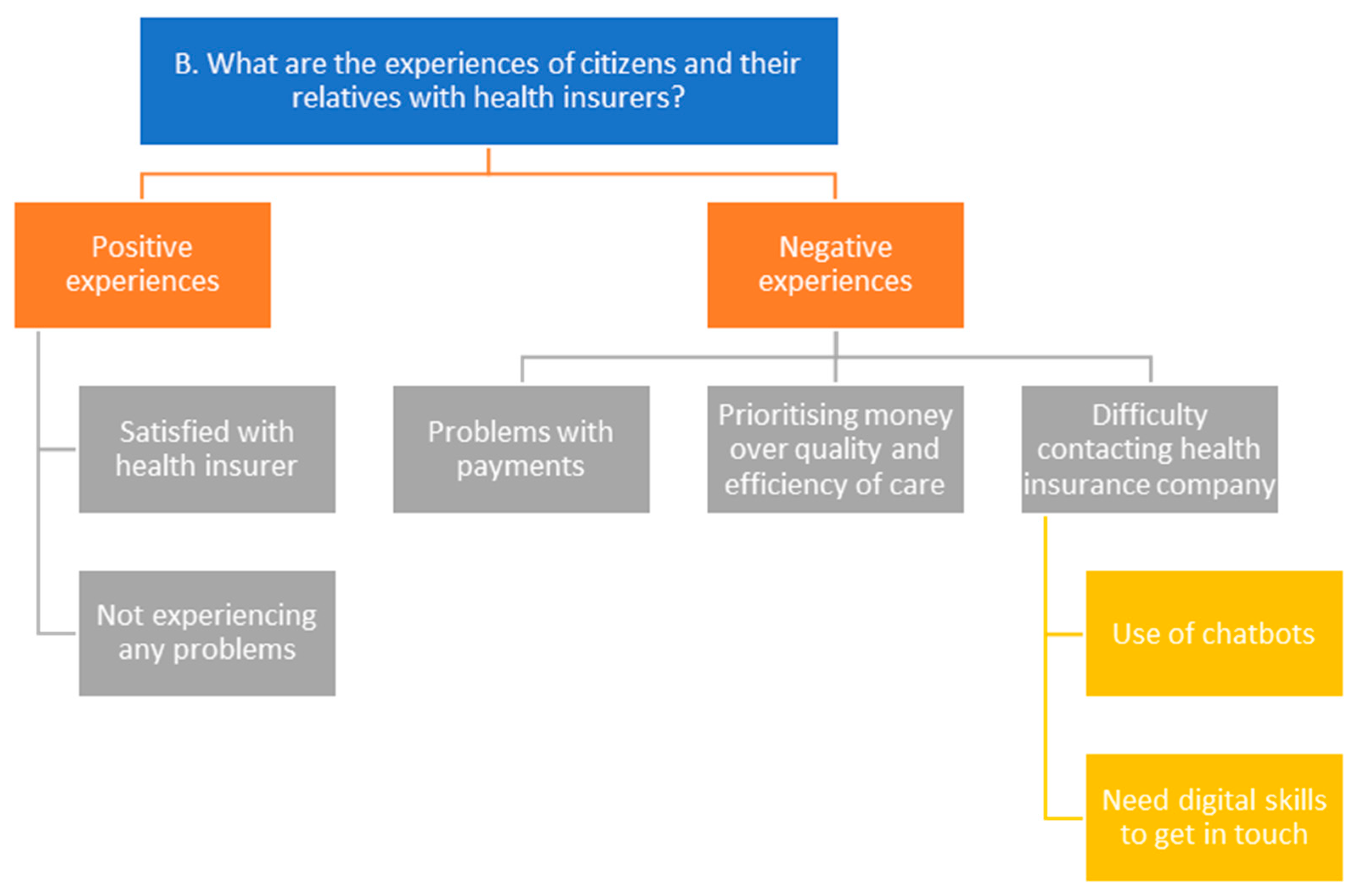

3.2.2. What Are the Experiences of Citizens and Their Relatives with Health Insurers?

“My brother-in-law was once picked up by ambulance somewhere and taken to a hospital not here in our area, but to another hospital because there was no room here. (…) Later he got a bill and that was because he did have a higher deductible I think. And that bill from the ambulance then had to be paid in stages because they didn’t have more money in their bank account. And then I think that just shouldn’t be allowed.”Participant #14

“My mother had medication for blood pressure, which worked perfectly without side effects, and all of a sudden it wasn’t allowed to be given anymore. And then I asked the pharmacist, ‘Why not?’. And so it was because 0.01 per cent of a cent per pill was more expensive than the alternative that she would get side effects from. But they get them because those 0.01 percentage points are important. And then you have more side effects, but you have a cheap drug, so yes, that creates aversion.”Participant #3

“Well, I have to say, my health insurance company does everything via e-mail. (…) That’s going to be a problem. At one point you could only log in with your DigID and I didn’t have a DigID. And then you had to log in with a smartphone. I don’t have a smartphone, I don’t have a cell phone, I’m one of those people who doesn’t have a cell phone.”Participant #3

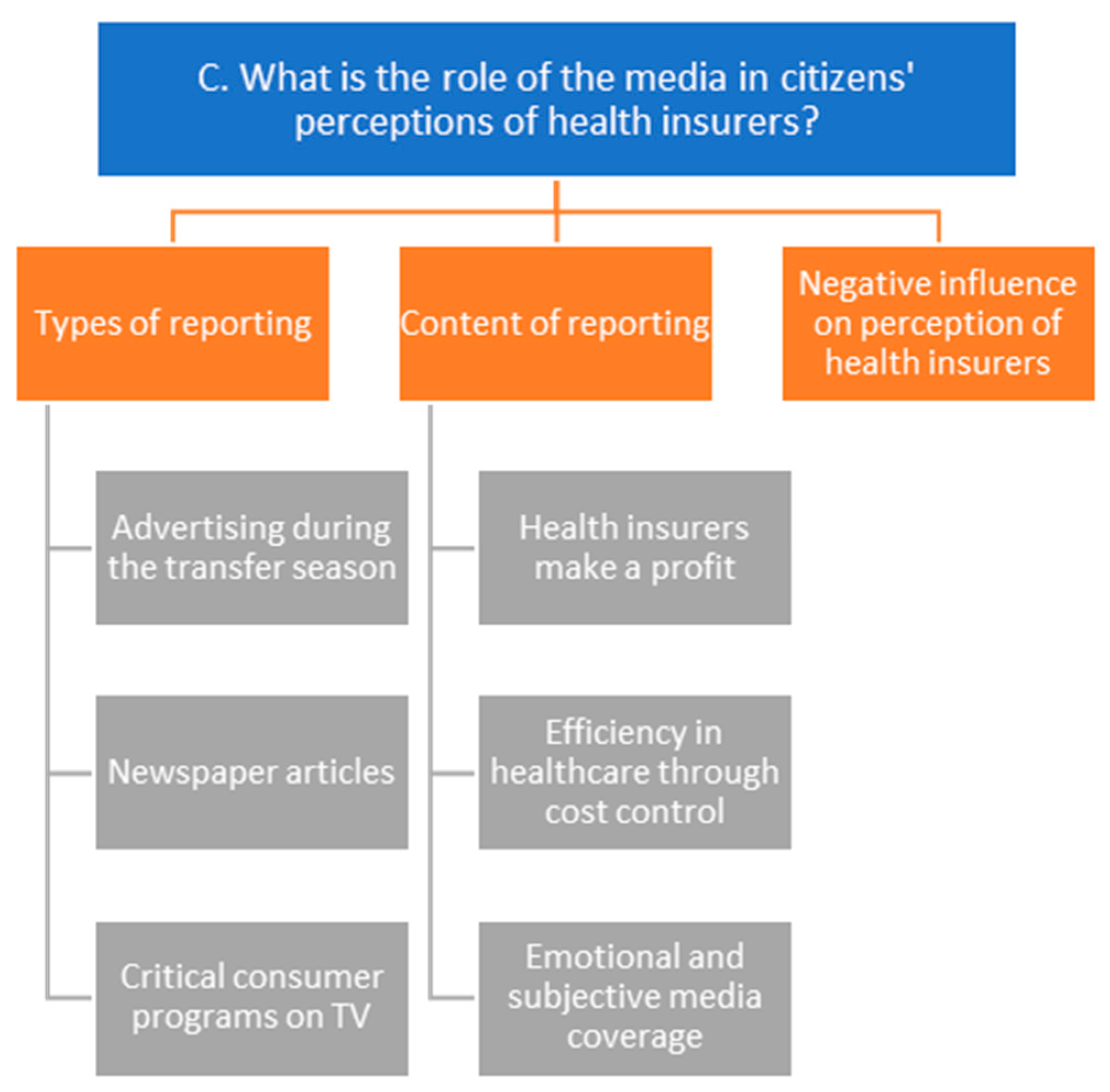

3.2.3. What Is the Role of the Media in Citizens’ Perceptions of Health Insurers?

“Then I see particularly the items about to what extent the health insurance companies are interfering with the efficiency of care, the cost of certain drugs and whether or not to use certain drugs and the trade-offs they have to make between care that is used very infrequently versus very widely used care and how those costs should be settled.”Participant #1

“Or things that have unfortunately gone less well or positive, yes. Often the negatives are expressed anyway. That’s good for the audience ratings, though.”Participant #10

“It’s often negative. But I also think because that’s kind of what’s out there. But there’s also a fallacy in that because everything that stands out comes out in the news. So if a hundred things go right, you don’t hear about it. Does one thing go wrong? That makes the news.”Participant #2

“Yes, my perception does get negatively affected by that, and that’s mainly because then they kind of take it easy off. And what I say is that I think yes, they really only look at those costs and how they can keep the price as low as possible. And that sometimes comes at the expense of patient care, so to speak.”Participant #7

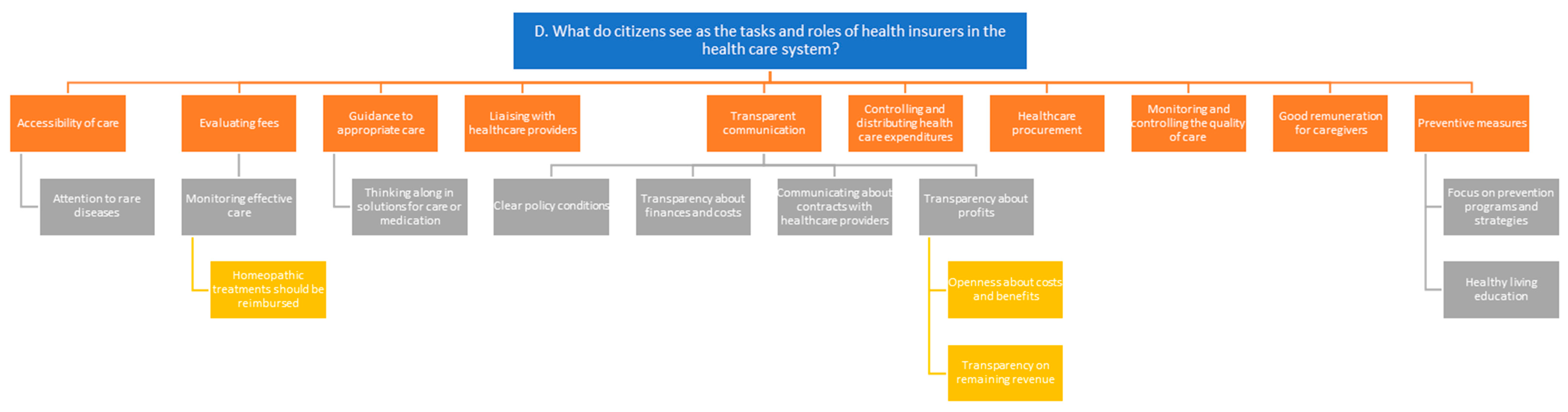

3.2.4. What Do Citizens See as the Tasks and Roles of Health Insurers in the Health Care System?

“I do expect that they ensure these negotiations go well so that everyone can access care everywhere. And I believe that is not always the case now, that you can really go everywhere, but rather to a large extent. But yes, I would expect them to make care as accessible as possible for people. So that you have the choice to go somewhere yourself.”Participant #7

“Well, ensure that the patient can make a choice from the treatment options that are available. So options of hospitals nearby or far away.”Participant #9

“I also expect that they enforce a certain level of care, meaning that they say [to healthcare providers] ‘you must also provide this care’, even if it yields little benefit for the caregivers themselves in that regard. Focusing more on rare diseases in particular.”Participant #1

“Well, I heard this week that homeopathic remedies don’t work at all. But why do they still exist? Look at what does work and maybe promote that, because there are definitely things that are effective. I think that through natural medicine there are enough options to solve problems. Unfortunately, this is not always reimbursed, and that’s a shame.”Participant #16

“I do think it’s very important that, even though everything is digital nowadays, insurers remain reachable by phone. It’s crucial that everyone can easily contact their insurer if there are things that need to be discussed.”Participant #6

“Well, I think it’s very important that they [health insurers] are very transparent about this [contracted healthcare providers]. Actually, every year I find it strange that you hear and see on the site that it is not yet known whether we will have a contract with them next year. Surely that should just be known the moment we get the choice to choose a health insurer.”Participant #8

“No, but I do think it’s important that those, that they provide that. Because ehm, actually you should just know what your health insurer does with its profits of course.”Participant #14

“The main task is to manage and disburse the pot of insurance money according to the clients’ or patients’ demand for care. Then. The main part of that task is balancing the incoming flows and the outgoing flows and they can turn to that by increasing premiums on the one hand or keeping healthcare costs in check on the other.”Participant #1

“Should you not put that [care premium] somewhere else, for instance into making more staff available in the end? Because we do face such a problem together. An ageing population in The Netherlands. More and more people are getting diseases and therefore more demand for care. And I do wonder whether the health insurers are sufficiently aware that this demand for care will soon have to be met. So the quality is good now. But what about ten years from now? I’m curious about that.”Participant #7

“They should try that, thus with education. They are already working on that. Towards healthier living of human beings. And they have to take the lead in that even more. But they don’t have to do that alone, but they can initiate that. Yes, they have to finance it, so I also think they should have a leading role in that.”Participant #15

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interview Guide Question | Relevant Research Question |

|---|---|

| 1. What can you tell me about how you view health insurers? a. Do you view your own health insurer differently compared to other health insurers? Why or why not? Can you explain? | A. How do enrollees perceive health insurers in general? |

| 2. What can you tell me about your personal experiences with health insurers? | B. What are the experiences of enrollees and their relatives with health insurers? |

| 3. Do people in your area ever share their experiences with health insurers with you? a. If so, what kind of experiences do people around you share? | B. What are the experiences of enrollees and their relatives with health insurers? |

| 4. Do you ever read media reports about health insurers? a. If so, what type of messages do you see in the media? | C. What is the role of the media in enrollees’ perceptions of health insurers? |

| 5. How much trust do you have in health insurers? a. Can you explain that? | A. How do enrollees perceive health insurers in general? |

| 6. What do you expect from a health insurer? a. What do you think the role of health insurers is in the healthcare system? Why? b. What do you think are important tasks for health insurers? Why? | D. What do enrollees perceive as the tasks and roles of health insurers in the health care system? |

| 7. What is your opinion about how health insurers carry out their tasks? Why? | D. What do enrollees perceive as the tasks and roles of health insurers in the health care system? |

| 8. What do you think health insurers can do better or differently? | D. What do enrollees perceive as the tasks and roles of health insurers in the health care system? |

| 9. Do you think health insurers should be allowed to make a profit? a. What do you know about that? b. If so, what do you think about that? | A. How do enrollees perceive health insurers in general? |

| 10. What do you think about the fact that most health insurers are associations or cooperatives, which are non-profit organisations? | A. How do enrollees perceive health insurers in general? |

Appendix B

References

- Enthoven, A.C. The history and principles of managed competition. Health Aff. 1993, 12 (Suppl. 1), 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enthoven, A.C.; van de Ven, W.P. Going Dutch—Managed-competition health insurance in The Netherlands. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2421–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ven, W.P.; Beck, K.; Buchner, F.; Schokkaert, E.; Schut, F.E.; Shmueli, A.; Wasem, J. Preconditions for efficiency and affordability in competitive healthcare markets: Are they fulfilled in Belgium, Germany, Israel, The Netherlands and Switzerland? Health Policy 2013, 109, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, W.; Kroneman, M.; Boerma, W.; van den Berg, M.; Westert, G.; Devillé, W.; van Ginneken, E. The Netherlands: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2010, 12, v–xxvii. [Google Scholar]

- Bouman, G.A.; Karssen, B.; Wilkinson, E.C. Zorginkoop Heeft de Toekomst [Health Care Purchasing is the Future]; Council for Public Health and Health Care (RVZ): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Healthcare Authority. Health Insurance Act: Article 11. 2022. Available online: https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_766940_22/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Dutch Healthcare Authority. Regulation on Health Insurance Information to Consumers. 2023. Available online: https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_743668_22/1/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Dutch Healthcare Authority. Regulation on Transparency of Healthcare Providers: Article 4, Paragraph 5. 2024. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0049988/2024-09-01/0/Artikel4 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Dutch Healthcare Authority. Zvw-Algemeen: Hoe Werkt de Zorgverzekeringswet [Health Insurance Act in General: How the Health Insurance Act Works]. Zorginstituut Nederland. 2024. Available online: https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/Verzekerde+zorg/zvw-algemeen-hoe-werkt-de-zorgverzekeringswet (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Voorstel van Wet van de Leden Leijten, Bruins Slot en Ploumen tot Wijziging van het Voorstel van Wet van de Leden Leijten, Bruins Slot en Ploumen Houdende een Verbod op Winstuitkering Door Zorgverzekeraars [Legislative Proposal Amending the Legislative Proposal by Members Leijten, Bruins Slot and Ploumen Prohibiting Profit Distribution by Health Insurers]. 2018. Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-34995-3.html (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Government of The Netherlands (n.d.). Standard Health Insurance. Available online: https://www.government.nl/topics/health-insurance/standard-health-insurance (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Bes, R.E.; Curfs, E.C.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Jong, J.D. Selective contracting and channelling patients to preferred providers: A scoping review. Health Policy 2017, 121, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stolper, K.C.; Boonen, L.H.; Schut, F.T.; Varkevisser, M. Managed competition in The Netherlands: Do insurers have incentives to steer on quality? Health Policy 2019, 123, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bes, R.; Wendel, S.; Curfs, E.C.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Jong, J.D. Acceptance of selective contracting: The role of trust in the health insurer. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hulst, F.J.P.; Brabers, A.E.; de Jong, J.D. The relation between trust and the willingness of enrollees to receive healthcare advice from their health insurer. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hulst, F.J.P.; Holst, L.; Brabers, A.E.; de Jong, J.D. Barometer Vertrouwen: Cijfers 2022. Available online: www.nivel.nl (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- De Pietro, C.; Crivelli, L. Swiss popular initiative for a single health insurer… once again! Health Policy 2015, 119, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, A. Umfrage zum Vertrauen in Klassische Krankenkassen/Krankenversicherungen 2017 [Survey on Trust in Traditional Health Insurance Schemes/Health Insurance 2017]. 2019. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/674061/umfrage/umfrage-zum-vertrauen-in-klassische-krankenkassen-krankenversicherungen-in-deutschland/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Maarse, H.; Jeurissen, P. Low institutional trust in health insurers in Dutch health care. Health Policy 2019, 123, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nold, V. Krankenversicherer. In Gesundheitswesen Schweiz 2015–2017: Eine aktuelle Übersicht; Oggier, W., Ed.; Hogrefe AG: Bern, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Balkrishnan, R.; Dugan, E.; Camacho, F.T.; Hall, M.A. Trust and satisfaction with physicians, insurers, and the medical profession. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, C.; Crispi, F.; Libuy, M.; Marchildon, G.; Cid, C. National Health Insurance: A conceptual framework from conflicting typologies. Health Policy 2019, 123, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabers, A.; de Jong, J. Nivel Consumentenpanel Gezondheidszorg: Basisrapport met Informatie over het Panel 2022 [Nivel Health Care Consumer Panel: Base Report with Panel Information]; Nivel: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CCMO (n.d.). Your Research: Is It Subject to the WMO or Not? Available online: https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/your-research-is-it-subject-to-the-wmo-or-not (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefman, R.J.; Brabers, A.; De Jong, J. Vertrouwen in Zorgverzekeraars Hangt Samen Met Opvatting over Rol Zorgverzekeraars [Trust in Health Insurers Correlates with View on Role of Health Insurers]; Nivel: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, I.; Stolper, K.; Boonen, L.; Schut, E.; Varkevisser, M. Vertrouwen in Zorgverzekeraars Vereist Duidelijkheid over Inkooprol. Economisch-Statistische Berichten. 2023. Available online: https://esb.nu/vertrouwen-in-zorgverzekeraars-vereist-duidelijkheid-over-inkooprol/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland. Dienstverlening Zorgverzekeraars. 2021. Available online: https://www.patientenfederatie.nl/downloads/rapporten/1025-rapport-dienstverlening-zorgverzekeraars/file (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- De Andrés-Sánchez, J.; Gené-Albesa, J. Not with the bot! The relevance of trust to explain the acceptance of chatbots by insurance customers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pinxteren, M.M.; Pluymaekers, M.; Lemmink, J.G. Human-like communication in conversational agents: A literature review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cardona, D.; Werth, O.; Schönborn, S.; Breitner, M.H. A mixed methods analysis of the adoption and diffusion of Chatbot Technology in the German insurance sector. In Proceedings of the 25th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Cancun, Mexico, 15–17 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tep, S.P.; Arcand, M.; Rajaobelina, L.; Ricard, L. From what is promised to what is experienced with intelligent bots. In Advances in Information and Communication: Proceedings of the 2021 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Volume 1 (pp. 560–565); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G.; Vollbracht, M. Media reputation of the insurance industry: An urgent call for strategic communication management. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta Strategists. Het Bedrijfsmodel van Zorgverzekeraars. Mogelijkheden om te Concurreren [The Business Model of Health Insurers. Opportunities to Compete]; Gupta Strategists: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, J.; Schneider, H.; Ferié, F. Mapping the consumption of government communication: A qualitative study in Germany. J. Public Aff. 2013, 13, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, L.; Rademakers, J.J.; Brabers, A.E.; de Jong, J.D. Measuring health insurance literacy in The Netherlands—First results of the HILM-NL questionnaire. Health Policy 2022, 126, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenens, W.; Van den Broeck, W.; Mariën, I. Channel choice determinants of (digital) government communication: A case study of spatial planning in Flanders. Media Commun. 2018, 6, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipirneni, R.; Politi, M.C.; Kullgren, J.T.; Kieffer, E.C.; Goold, S.D.; Scherer, A.M. Association between health insurance literacy and avoidance of health care services owing to cost. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e184796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, L.; Pieterson, W. Strategic communication in a networked world: Integrating network and communication theories in the context of government to citizen communication. In The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, L.R.; Garrard, G.E.; Bekessy, S.A.; Mills, M.; Camilleri, A.R.; Fidler, F.; Fielding, K.S.; Gordon, A.; Gregg, E.A.; Kusmanoff, A.M.; et al. Messaging matters: A systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, S.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S.; Deat, F. Numbers over narratives? How government message strategies affect citizens’ attitudes. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 1005–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaghaghi, A.; Bhopal, R.S.; Sheikh, A. Approaches to recruiting ‘hard-to-reach’ populations into research: A review of the literature. Health Promot. Perspect. 2011, 1, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandro, M.; Lagomarsino, B.C.; Scartascini, C.; Streb, J.; Torrealday, J. Transparency and trust in government. Evidence from a survey experiment. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Market Access Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van der Hulst, F.J.P.; Huijgen, S.; Brabers, A.E.M.; de Jong, J.D. Exploring Trust in Health Insurers: Insights from Enrollees’ Perceptions and Experiences. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2025, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13020029

van der Hulst FJP, Huijgen S, Brabers AEM, de Jong JD. Exploring Trust in Health Insurers: Insights from Enrollees’ Perceptions and Experiences. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy. 2025; 13(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13020029

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan der Hulst, Frank J. P., Sanne Huijgen, Anne E. M. Brabers, and Judith D. de Jong. 2025. "Exploring Trust in Health Insurers: Insights from Enrollees’ Perceptions and Experiences" Journal of Market Access & Health Policy 13, no. 2: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13020029

APA Stylevan der Hulst, F. J. P., Huijgen, S., Brabers, A. E. M., & de Jong, J. D. (2025). Exploring Trust in Health Insurers: Insights from Enrollees’ Perceptions and Experiences. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy, 13(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmahp13020029