1. Introduction

The 5G/6G network is separated into the 5G/6G network architecture sections: the control layer, the access layer, and the forward layer [

1]. This architecture separates user data from the control plane from the user plane only through the access and forwarding layers. In contrast, the control layer performs a logically centralized network control role. The access layer covers a wide range of wireless technologies and network configurations. Based on a common hardware platform, the forward layer can ensure high reliability, minimal delay, and average load of the service data flow.

Blockchain-enhanced Software-Defined Networking refers to a network controlled by a central entity or software used by all the network resources. With an SDN, the control is moved from the network layer to the application layer, dividing the data plane from the control plane. It has numerous advantages over a traditional network, including lower costs, improved security, more flexibility, easier configuration, and prevention of vendor lock-in. A secure framework for SDN can allow a network manager to change the way the network devices, i.e., Routers and Switches, handle packets by enabling complete control of the rules set into network devices from a central console. The mobility of devices in wireless networks has an effect on communication services. The controller can solve position changes in horizontal switching by detecting geographic locations, and it can also somewhat enhance vertical mobility and offer load balancing. Although there is no mobility, the controller can nevertheless locate an alternative route in the event of a failure and balance the traffic between nodes. Some researchers have brought up these issues; however, there are not many workable answers.

Wireless networks have become more virtualized and sophisticated with 5G/6G. While there are significant security flaws in the topology of conventional wireless networks, 5G and 6G promote infrastructure sharing. Even if the widely accepted hypotheses are true, their plausibility is diminished in networks with a large number of adaptive sensing devices. Additionally, the virtualization trend will provide many unknown difficulties.

The variables that affect a network’s quality include bandwidth, Jitter, propagation time, throughput, and latency. One of the most significant is Jitter, which typically causes reduced network throughput and, in certain situations, network congestion that sometimes results in total network failure. The market for Secure-SDN technology is expanding as all the major multinational corporations—including Google, Facebook, and Amazon—adapt to it and change their traditional networks. Traditional networks are now more sluggish, risky, and expensive. Software-Defined Networking with blockchain, on the other hand, enhances network connectivity for sales, customer support, internal communications, and document sharing. This job is in high demand since it integrates blockchain and SDN.

SDN enables complete network control, enabling quick responses to change network or business requirements. By converting them to a Secure Framework for Software Defined Networks, this work focuses on improving the scalability, efficiency, and security of the current Traditional Networks. By dividing the network into three layers—the application layer, control layer, and forwarding layer—traditional decentralized networks converted to centralized SDN networks. These layers each play a part in enhancing the scalability, efficiency, and security of the network. Routing attacks change how packets are routed on the SDN by manipulating routing control information. In order to keep the network secure from routing attacks, the data of the SDN network, such as routing information, including IP addresses and MAC addresses, are stored on a blockchain utilizing multichain.

The contributions of the proposed work are as follows:

- ❖

This paper first highlights how much faster, more scalable, and less expensive a software-defined network is than a conventional network in 5G–6G SDN.

- ❖

Building a private blockchain and uploading the network’s routing information makes SDN safe and impossible for anyone to change it. Creation of a private blockchain with the sole purpose of making a network more secure. Therefore, in order to keep the network secure from malicious nodes, the data of the SDN network, such as routing information, including IP addresses and MAC addresses, are stored on a blockchain utilizing multichain.

- ❖

Transfer rate, jitter, delay, and capacity are among the network performance measures used to evaluate the network in a mininet network simulator.

The remainder of the manuscript is structured as follows: The associated work is briefly reviewed in

Section 2. The proposed work is explained in

Section 3. The simulation setup and results are presented in

Section 4, and

Section 5 outlines the conclusions.

2. Related Work

Computer networks are currently getting faster, smarter, resource-rich, and more complex as a result of rapid progress. For instance, the Internet of Things (IoT) has been steadily embraced by many businesses and networks. According to a Gartner forecast, there are more than 20 billion linked devices worldwide as of 2020. As the control and data plane are traditionally integrated inside the network devices, the IoT architecture frequently contains a large number of devices, servers, and middleboxes, making network management and configuration much more challenging and error-prone. It is also very laborious to add new devices and modify services. Deploying new services without disrupting existing ones is typically a challenging task. As a network becomes bigger, this problem can get worse.

A viable solution to this problem is Software-Defined Networking (SDN), which separates the network control plane from the data plane. In such a network, IT managers can adjust network regulations from a controller that is software-based without having to modify settings in each switch. That is to say, regardless of the precise connections between a server and devices, the centralized SDN controller can instruct the switches to supply network services under the needs. This centralized management helps ease network administration and lighten configuration work. In reality, SDN still faces numerous security risks. For example, the SDN controller itself could fail in an adversarial environment, and distributed controllers may also experience reliability and reputation problems.

On the other hand, blockchain technology has drawn a lot of interest from academics and industry due to the massive success of the Bitcoin cryptocurrency. A blockchain maintains a record of all data transfers, where the record is also referred to as a “ledger” and the transfer of data as a “transaction”. Each new transaction, which can only be added to the blockchain after successful verification, can be verified via a peer-to-peer network. In this situation, it is thought that blockchain would make it possible for unrelated parties to exchange data or information without requiring a reliable intermediary.

Akshatha et al. (2018) [

2] suggested a novel approach for conforming the 5G architecture of the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) to the principles of Software Defined Networking (SDN). The gNB base station is transformed into a pure data plane node as a result of moving the control functionality from the 5G Radio Access Network (RAN) to the network core. As a result, the cost of signaling between the RAN and the core network is significantly reduced. Additionally, the performance of the system is enhanced.

The common SDN-5G/6G application scenarios and important concerns are covered by Long et al. (2019) [

3]. This work also concentrated on mobile network mobility management strategies. Additionally, three types of software-defined 5G/6G mobility management mechanisms are discussed and contrasted.

Ly et al. (2020) in [

4] analyze the dual-channel architecture specified by the software of wireless sensor in 6G/IoE and proposes a reasonable solution to reduce the signal interference so that the related signals can be transmitted more effectively. This is necessary in order to broadly apply 6G/IoE (Internet of Everything) to various scenarios in real life and connect the infrastructure closely related to people through the network. Zebari et al. (2021) in [

5] primarily focused on 5G by highlighting the fundamental design principles associated with such technology, such as the infrastructure architecture of 5G, the deployment potential of 5G, the technology employed in 5G, and the services and applications that 5G is capable of offering.

Yang et al. (2022) [

6] presented that the next-generation 6G network should be data-driven and sensor-based to enable huge connections and distributed intelligence. Artificial intelligence (AI) is expected to play a significant role in meeting critical needs for 6G networks because the majority of intelligent applications are being deployed at the edge [

6]. The authors outlined the need for a 6G network for AI applications before providing a thorough overview of AI toward 6G networks. They focused on the demands, trends, and problems of distributed edge intelligence in upcoming 6G networks. Then, 6G networks are used as inspiration for a discussion of a liquid-specific and adaptable software-defined network architecture for AI applications.

Yungaicela-Naula et al. (2022) [

7] examine the most recent security automation research projects in SDN environments. Different classes of security solutions with varying degrees of automation and complexity were discovered and ranked. Four clearly defined qualitative parameters—self-healing, self-adaptation, self-configuration, and self-optimization—are used to gauge the degree of automation. The quantity of processing, storage, and implementation requirements serve as indicators of complexity.

The Internet of Things (IoT) of today will become a gigantic IoT of the future as the number of internet-connected gadgets rises [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. On distributed-controller software-defined networking, network policy updates must be committed in a consistent manner. If this does not happen, the network can encounter unanticipated transient configuration states that affect its performance, security, or even proper operation [

13]. By providing a comprehensive view of the network, Software-Defined Networking (SDN) makes it possible to administer networks effectively [

14]. Although SDN was not specifically designed to address IoT problems, it can nonetheless give the motivation to address complex problems and aid in effective IoT service orchestration. IoT realization is a difficult problem because of the present IoT paradigm’s large data generation, complex infrastructures, security risks, and requirements from the recently developed technologies.

Due to its benefits in offering broad access services and the quick development of satellite technology, the space information network has been presented as a solution to address the rising demands of ubiquitous mobile communication [

15]. However, the extremely dynamic topology and the limited resource availability of satellites make management and resource use difficult for development. In order to streamline management and boost resource efficiency, some effort has been made to integrate the SDN, also known as the software-defined space information network. Huo et al. (2022) [

16] provide a unique lightweight measuring system that operates in the controller in order to lessen the overhead involved in the measurement process and achieve roughly fine-grained measurements. Coarse-grained measurement and interpolation optimization make up the innovative lightweight measurement architecture.

Abid et al. (2022) [

17] state that virtualization and Software-Defined Networking (SDN) are two promising technologies for affordably addressing the size and versatility needed for IoT. Following a discussion of traditional IoT networks and the necessity of SDN and Network Function Virtualization (NFV), the authors examined SDN and NFV solutions for various IoT implementation strategies. According to Singh and Sharma (2019) [

10], researchers must consider integrating new technologies rather than making minor changes to the LTE specifications since rising user networking demands in industrial automation, precision agriculture, and augmented reality are driving the development of 5G networks. A rapid and effective response must be made in the present world of smart communication, processing, and operation [

18]. According to Chica et al. (2020) [

19], SDN enables network managers to more flexibly apply security defense mechanisms to its network-wide visibility, monitoring, and flexible network programmability. The core components of the overall system framework are an automated security management function that aids the SDN controller in attack detection and mitigation and a network security monitor function that helps network managers keep tabs on the health of their networks.

According to Bannour et al. (2018) [

20], a physically-centralized control plane with a single-controller overseeing the entire network is the ideal option in terms of simplicity. A single-controller system, though, might not be able to keep up with the network’s expansion [

20]. With an increase in requests and a struggle to maintain the same level of performance, it is likely to become overloaded (a controller bottleneck). A Data Center Network primarily consists of tens of thousands of switching components. One centralized SDN controller could get overloaded by the volume of control events produced by such a large number of forwarding components that can develop quickly. Specifically, WANs and overlay networks are logically dispersed control plane architecture that functions in multi-domain heterogeneous contexts. The most apparent benefit of distributed SDN is the separation of the control plane’s intra-domain and inter-domain features, with each feature being carried out by a different component of the distributed SDN architecture.

Routing attacks change how packets are routed on IoT networks by manipulating routing control information [

21]. Farris et al. (2018) [

21] present that through the generation of fake erroneous routing notifications, hostile attackers can construct routing loops. Routing attacks have been researched using a variety of tactics. A malicious node advertises the shortest path to a destination node in a Black Hole attack, forcing all packets to be forwarded to that node. The enemy can then drop or modify the arriving packets. In a Sybil attack, an adversary device, or Sybil node, can generate false routing information and claim a genuine identity in the IoT network, which can change the proper forwarding rules of nearby nodes. On recent attacks and defense strategies for distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, Javanmardi et al. (2021) [

22] highlighted TCP SYN flood attacks in IoT and SDN in particular. Additionally, they summarised a simple method for detecting TCP SYN flood assaults in IoT networks, a predictive model for mitigating SYN TCP attack detection, and bots that resemble Mirai as IoT-based DDoS attacks. Mirai employs bot instances that launch TCP SYN flood attacks on the targeted computing resources.

Customizing blockchains to increase the security and energy efficiency of SDN was presented by Latif et al. in 2022 [

23]. IoT’s computation and energy bottleneck problem must be rapidly managed if safe and reliable services are to be provided. They concentrated on minimizing a few network-related issues with IoT. They have been suggested as an architecture for IoT networks to increase security and energy efficiency by utilizing the power of AI. They combined two cutting-edge AI-based technologies, blockchain, and SDN, and took advantage of their promise for effective data analysis, data security, and energy management. A cluster-based framework has been established for the IoT network with blockchain integration for the SDN controller. The blockchain is utilized on networks that are both public and private. A brief description of the related work is shown in

Table 1.

When using traditional networks in the modern era, several problems can occur. They unquestionably no longer exist. We must rethink how we approach networking in light of technologies like cloud computing, remote work, and multi-device management. The amount of data being transmitted grows daily, which increases the number of 5G and 6G devices. When a new network device is added to the system, rewriting is required. All of these gadgets have human controllers. Along with the development of 5G and 6G networks, more devices need to be monitored. Managing these massive 5 G and 6G network infrastructures is difficult. This needs to be performed dynamically in large networks.

SDN facilitates the separation, abstraction, and sharing of network resources, which aids in the virtualized network infrastructure in 5G [

25]. NFV is a noteworthy innovation that has profoundly altered networking and service provisioning. While some businesses assert that 5G solutions are already available, there are legitimate worries that we may only see a few SDN point solutions rather than a fully virtualized, SDN-enabled 5G mobile network, given the enormous effort of softwarizing mobile cellular networks [

26]. The authors in [

27] provided an in-depth analysis and current solutions for 5G network slicing with SDN and NFV. Following a presentation of the 5G service quality and commercial criteria, the authors described the 5G network softwarization and slicing paradigms, outlining key ideas, their background, and many use cases. The management and orchestration of network slices in a single domain are covered, and then a thorough analysis of management and orchestration techniques in 5G network slicing over several domains.

In comparison to current 4G technology, 5G infrastructures are anticipated to offer anywhere network access with notable network improved efficiency, including 1000 times more available bandwidth, 10–100 times higher data rate increases, upwards of 90% efficiency, reduced end-to-end delay with less than 1 ms, and 99.999% ease of access [

27,

28]. The author in [

28] analyzes and contrasts three SDN-based multi-hop routing methods. An SDN-based BS in the routing framework controls multi-hop connectivity between mobile nodes that are within its coverage region. The architecture makes use of two different frequency bands: licensed frequency for cellular and unlicensed frequency for D2D communication. In order to govern data forwarding, the controller uses both proactive and reactive methods. The authors in [

29] developed an SDN-enabled network model that supports the FOG networking paradigm in 5G IoT scenarios in order to assess the viability of the Mininet network emulator as a component of the 5G simulation environment.

Hence, it is evident from the linked literature that there has never been a framework for 5G–6G routing information security in SDN utilizing blockchain. Therefore, this work presents a security architecture that combines blockchain technology with Software-Defined Networking in 5G–6G.

3. Proposed Approach

The following discussion covers the many technological ideas connected to the proposed work:

Using software-based controllers or application programming interfaces (APIs) to communicate with the network’s underlying hardware architecture and control traffic is known as software-defined networking (SDN). This architecture is distinct from conventional networks, which manage network traffic using specialized hardware (such as switches and routers). Through software, SDN may build and manage a virtual network or manage conventional hardware. SDN has numerous advantages over traditional or conventional networks because it divides the control plane and the data plane and places the control in the application layer rather than the network layer.

Blockchain data is stored in such a way that system changes, hacking, and cheating is made difficult or impossible. A blockchain is basically a network of nodes that replicates and distributes a digital record of transactions throughout the network. Each blockchain block is made up of numerous transactions, and each individual’s ledger acquires a copy of every new transaction added to the blockchain. The term Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) refers to a decentralized database maintained by many people. On a blockchain, transactions are stored with an unchangeable cryptographic fingerprint known as a hash. As a result, if a block occurred in only one chain, it would be obvious that it had been updated. To breach a blockchain system, hackers would need to change every block in the chain across all decentralized versions of the chain.

Smart Contracts—A smart contract is a software program that, under specific conditions, controls the exchange of digital wealth between parties directly and autonomously. A smart contract, like any other contract, functions with automated enforcing compliance. Smart contracts are computer programs that run precisely how they are configured (coded, programmed) by their authors. A smart contract is enforceable by code, just way a conventional contract is by law.

iPerf: The maximum possible bandwidth on IP networks can be actively measured using the iPerf. It allows numerous fine-tuning timing, buffer, and protocol-related factors (TCP, UDP, SCTP with IPv4 and IPv6). It provides parameters such as bandwidth, loss, and others for each test.

Multichain—Multichain technology allows users to create specific private blockchains that businesses can utilize for financial transactions. Multichain offers us a command-line interface and a straightforward API. This aids in establishing the chain. The multichain platform cuts the time required for blockchain development by up to 80%.

The steps involved in the proposed smart contract for storing routing information in the multichain are described in Algorithm 1 as follows:

| Algorithm 1: Routing Information Registering: MAC Address, IP Address, and Nest Node ID in Multichain |

Procedure: Route(list, macAddress, IP, NextNode)

Step1: if(device[macAddress]! = True]).

Step1.1: then mac_list.push(macAddress).

Step1.2: device[macAddress] = True

Step2: if(device[IPAddress]! = True]).

Step2.1: then ip_list.push(IPAddress).

Step2.2: device[IPAddress] = True

Step3: if(device[NextNode]! = True]).

Step3.1: then NextNode_list.push(NextNode).

Step3.2: device[NextNode] = True

Step6: end procedure Route |

The steps involved in the proposed

LSSDNF approach are described in Algorithm 2 as follows:

| Algorithm 2: Proposed approach: LSSDNF |

| The steps involved in the proposed LSSDNF approach are described as follows: |

| | Step1: With the aid of the mininet network simulator, the new topology is set up. The topology components are computers, Openflow switches, and an Openflow remote SDN controller. |

| | Step2: The Openflow 1.0 protocol is then used to implement the aforementioned architecture in the mininet. |

| | Step3: Execute several instances of the cli within the same display when the command-line interface is provided in a window using the Xterm. Use Xterm to access the shells of the two network computers for testing. |

| | Step4: Configured one of the two chosen devices as a server and the other as a client using the Iperf utility.

|

| | Step5: In order to accept incoming packets of the same protocol type, the client creates a TCP or UDP window.

|

| | Step6: Using the client’s IP address as a connection point, the server begins transmitting data packets to the client.

|

| | Step7: In addition to receiving the data packets, the client stores each network characteristic in a separate file, such as bandwidth, jitter, and transfer rate.

|

| | Step8: For each of the two types of topologies, steps 1 through 6 are repeated three times.

|

| | Step10: Out of the topologies compared above, pick the best one and obtain its routing data from the SDN controller.

|

| | Step11: Using Multichain, build a private Blockchain and store the routing data. |

4. Test System, Assumptions, and Result Analysis

This section provides concrete evidence of how SDN outperforms traditional networks. Here, we tested two distinct network types while controlling the number of devices connected to the network, its bandwidth, and the testing period for each network.

4.1. Simulation Setup

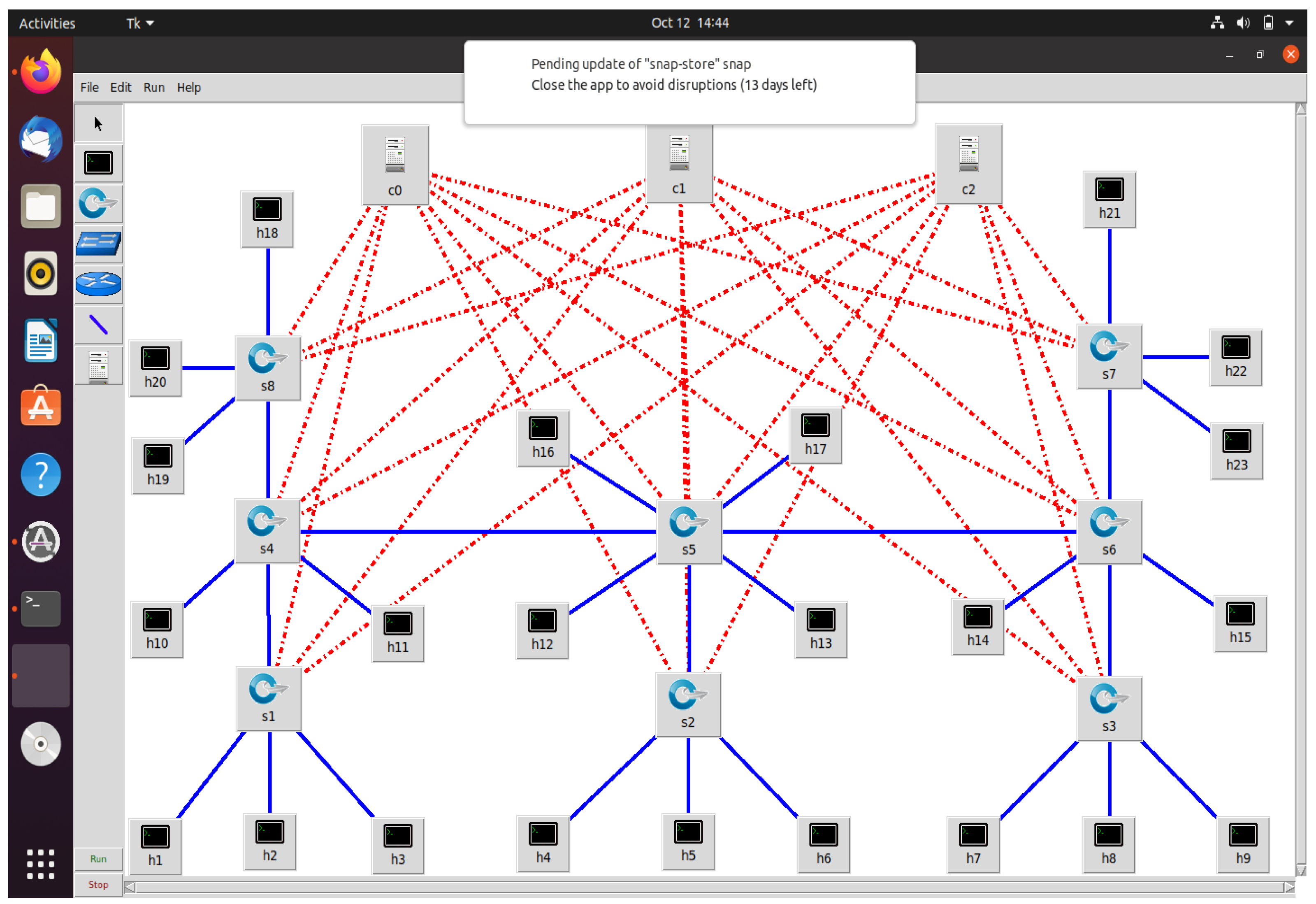

To simulate our network topologies, we used the mininet network emulator. Mininet runs actual kernel, switch, and application code on a single machine to build a realistic virtual network. In this work, we created two topologies using mininet: one with 40 devices, including 30 computers, 9 switches, and 1 SDN controller; the other, with 42 devices, including 30 computers, 9 OpenFlow switches, and 3 SDN controllers.

The multi-controller topology serves only to make the single-controller topology crash-protected. For example, in a single-controller topology, everything depends on the controller, and the entire network will also crash if it crashes. Here, we used a multi-controller topology in a master-slave configuration, where one controller is the master and all the others are slaves; if the master crashes, the slave wakes up and begins acting like the master, and our entire network does not crash.

The following tools and technologies are used to simulate the networks:

- ❖

Mininet and the Pox SDN controller are used to construct the topology that will be evaluated [

30,

31].

- ❖

iPerf is employed in order to test the network [

32].

- ❖

For storing routing information, a multichain private blockchain is used [

33].

- ❖

Smart contracts are created using the Solidity programming language.

- ❖

For evaluating the behavior of the smart contract under various circumstances, the Mocha testing framework is used.

- ❖

Ganache-cli for creating a test wallet and blockchain for testing [

34].

- ❖

Truffle HD Wallet Provider for connecting our smart contract to the user’s Metamask wallet in the web3 framework using Remix IDE [

34,

35].

The parameters used to measure the network performance are given in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. The description of the test network is as follows:

- ❖

In the case of TCP: With a network connection established between the two end devices and a TCP bandwidth restriction of 26 Mbps, data packets were transferred from device 1 to device 2 to test the network.

- ❖

In the case of UDP: Set the bandwidth restriction to 2 Mbps, and send several UDP data packets from one end device to another end device.

- ❖

Routing Information—Using the Multichain blockchain development platform, a private blockchain is created and put the routing data (IP, MAC, etc.) to the controller in the multichain.

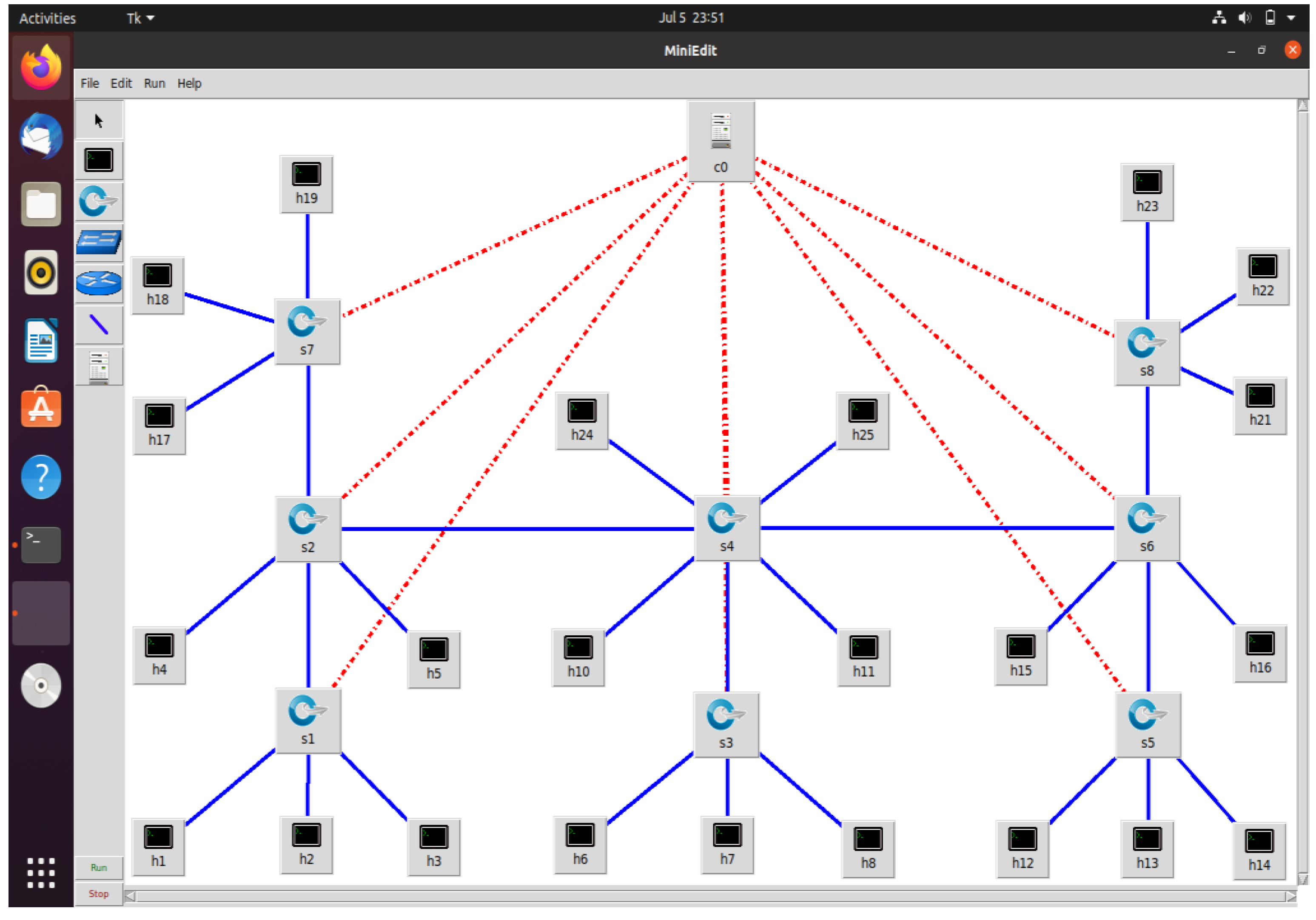

The test networks with a single-controller and multi-controller topologies are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively.

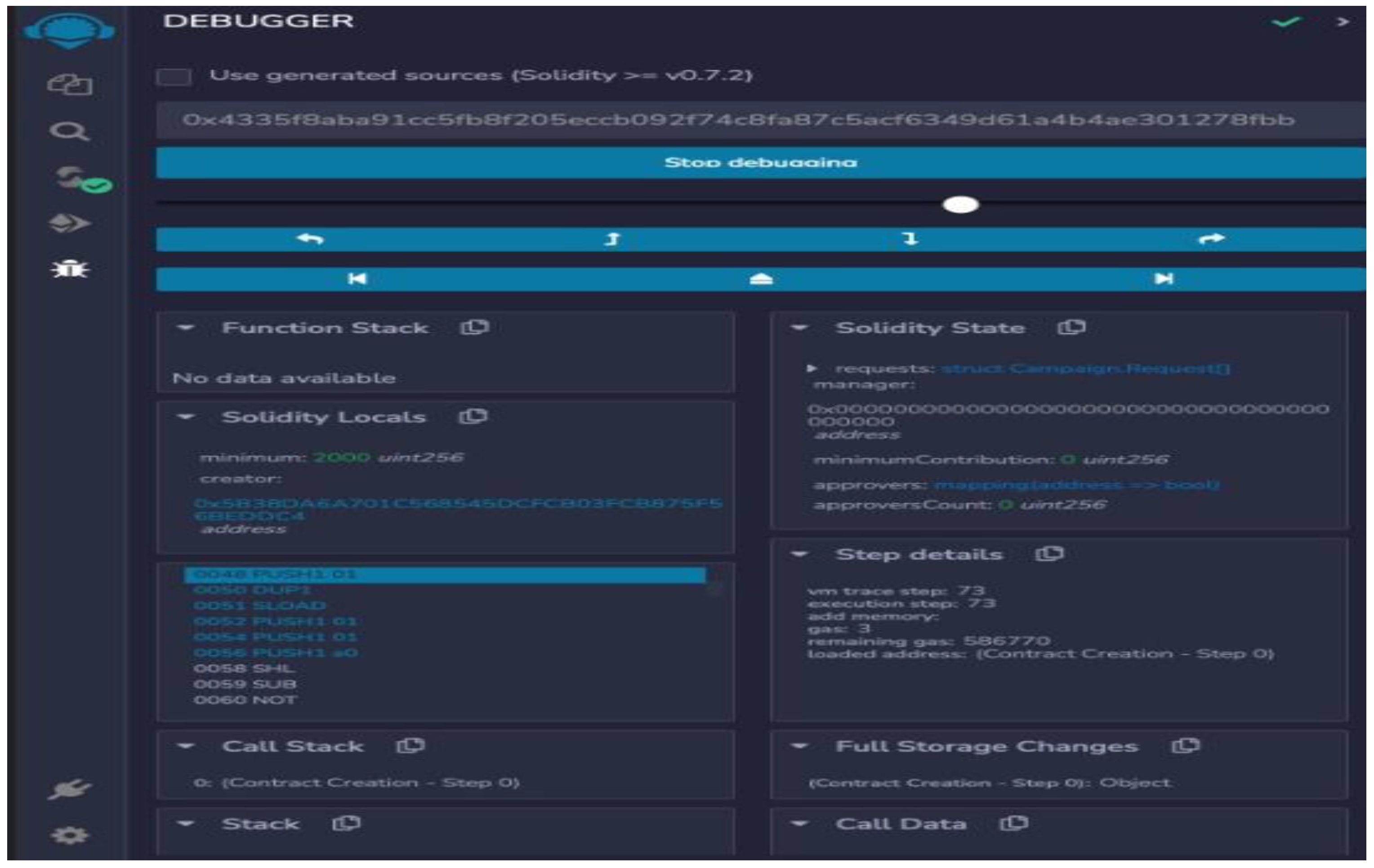

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 display the state of smart contracts that have been deployed and the cost of transactions on the Ethereum blockchain. The transaction cost in this instance is 589,671 gas, as can be observed. Therefore, creating a private blockchain in the SDN would be economical. With the aid of the Multi-chain blockchain development platform, a private blockchain for network security was created. By uploading our networking routes and controller information to the blockchain, followed by regular checks to see if the network routes have changed or not, the network is made more secure by performing security checks. Therefore, we only need to isolate that one malicious node from the network and avoid performing security checks on the entire network. Here, an attacker tries to provide bogus information to the controller in order to change the routing information. Routing attacks change how packets are routed on SDN by manipulating routing control information [

21]. As a result, multi-controller nodes employing multichain can detect a malicious node and an intrusion attempt to change the routing information.

4.2. Simulation Metrics

A description of the test parameters used is provided below:

- ❖

Bandwidth

- ❖

Throughput

- ❖

Latency (Delay)

- ❖

Jitter

Any network’s performance is determined by the bandwidth and the protocols being utilized. After adjusting some basic variables, including the number of devices in the network, the bandwidth, and the amount of time, the network was tested. The iPerf network tool is used to identify the network characteristics for two distinct types of networks. The aforementioned parameters are applied with the following constraints:

- ❖

Time: A brief test period of 180 s for each of the three networks was sufficient to produce the desired findings.

- ❖

Bandwidth: For all three networks, the bandwidth used to extract the TCP and UDP network packet characteristics was set to a constant value of 26 Mbps and 2 Mbps, respectively.

- ❖

No of Devices: The controller in topology one was the only network device modified. In the first type of architecture, the single-controller topology, we only need a single SDN controller. Specifically, we use three SDN controllers in a master–slave configuration for the multi-controller SDN topology.

4.3. Experimental Results

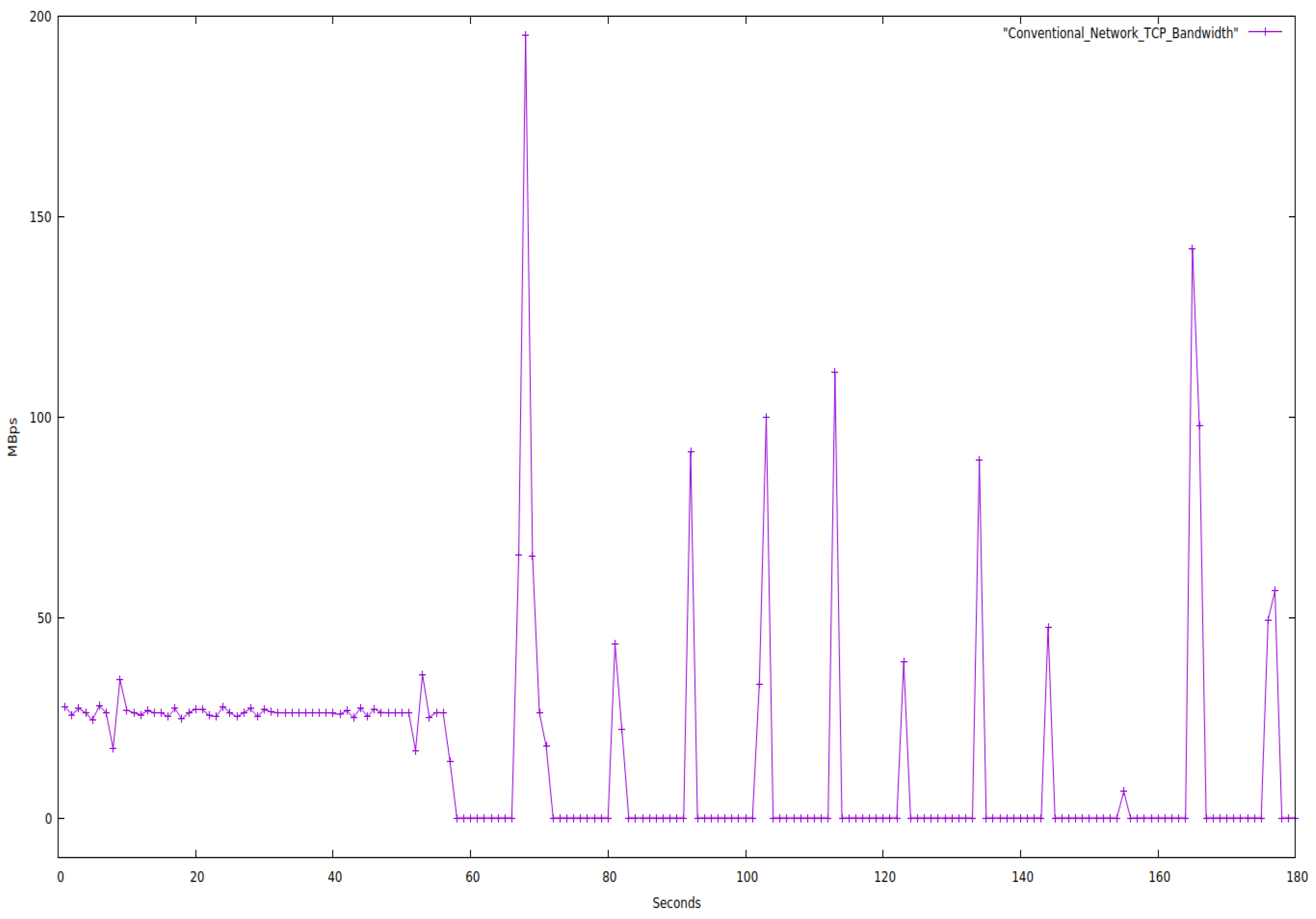

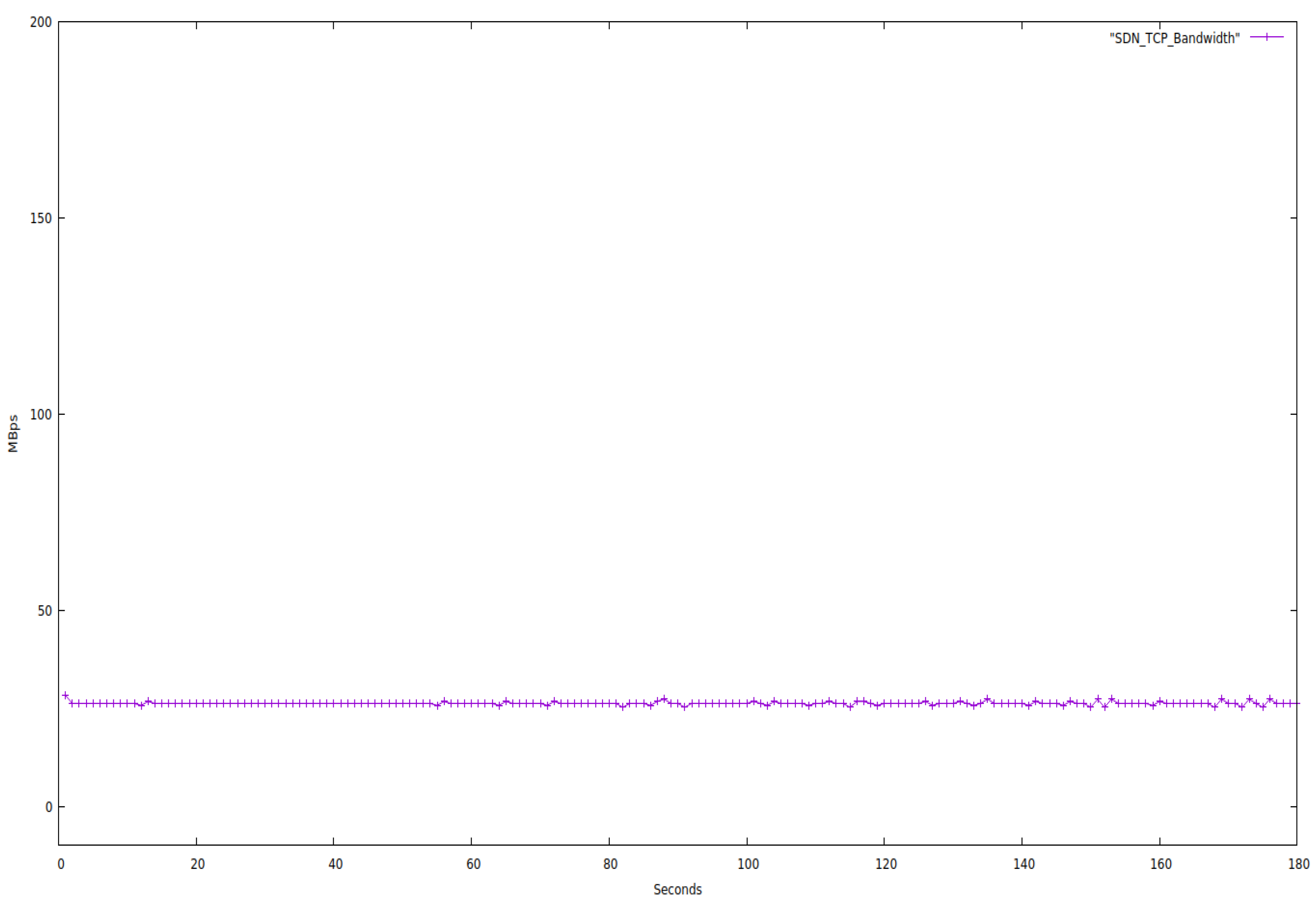

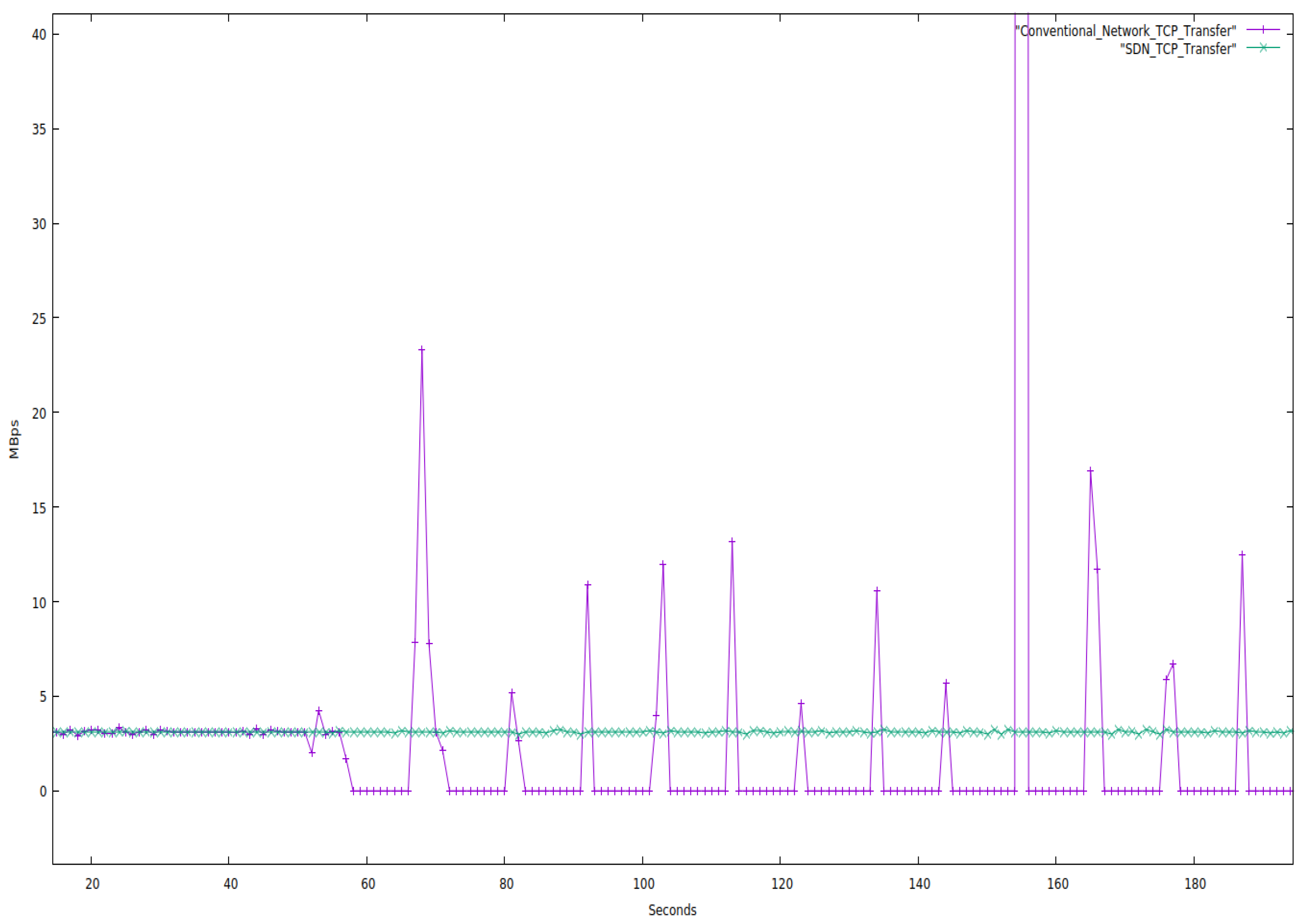

Traditional TCP Network vs. SDN TCP Network

We evaluated both networks for 180 s while restricting the bandwidth to 25 Mbps and only using TCP protocol packets. Below is a graph of the network properties.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 make it very evident that SDN offers more bandwidth stability than traditional networks.

Figure 7 clearly shows that throughput nearly stays constant for a constant bandwidth in an SDN network. In contrast, there is so much fluctuation in a traditional network that the transfer rate occasionally drops to zero and stays there for a while. We also noticed that SDN could transfer more data than the conventional network for the same period.

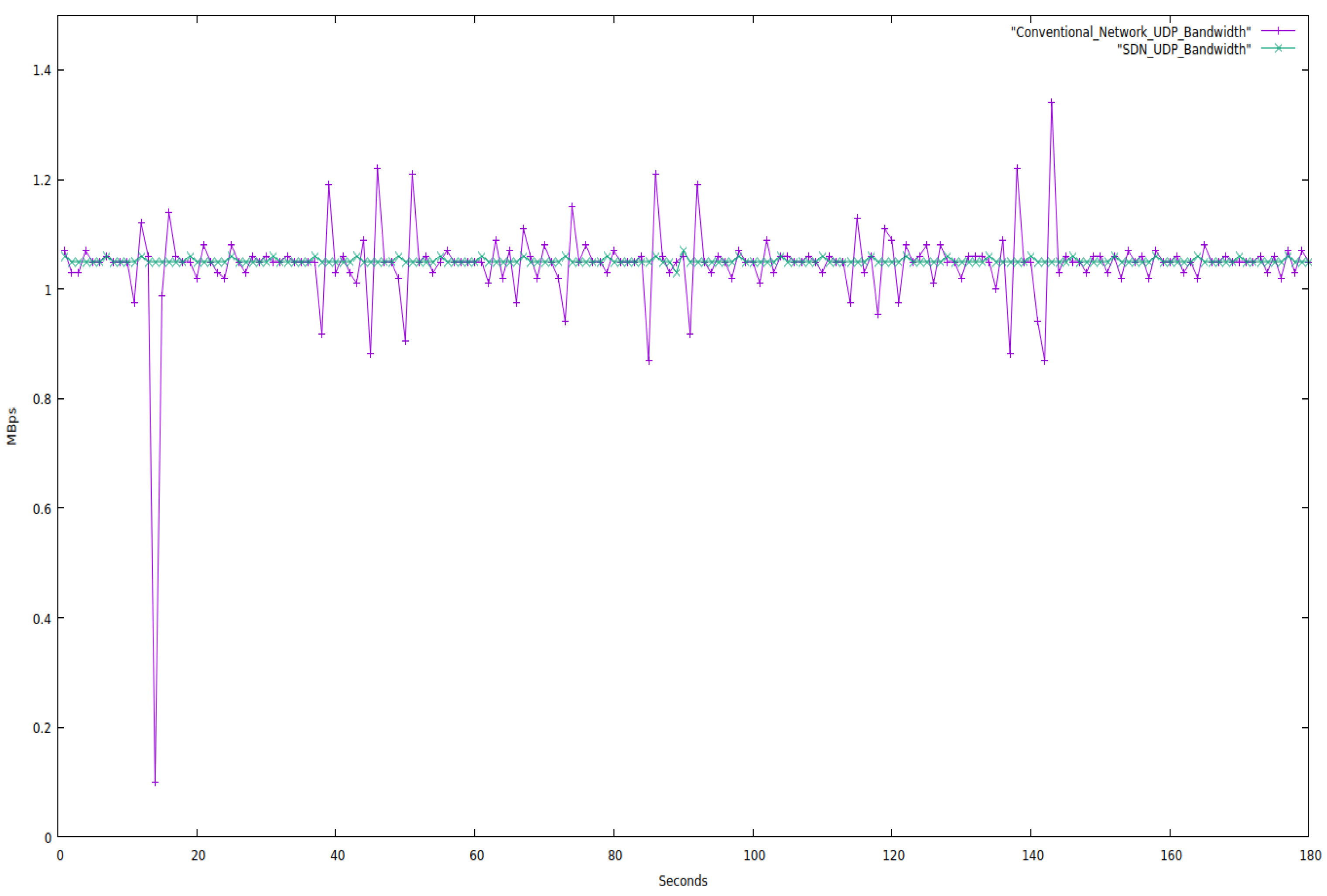

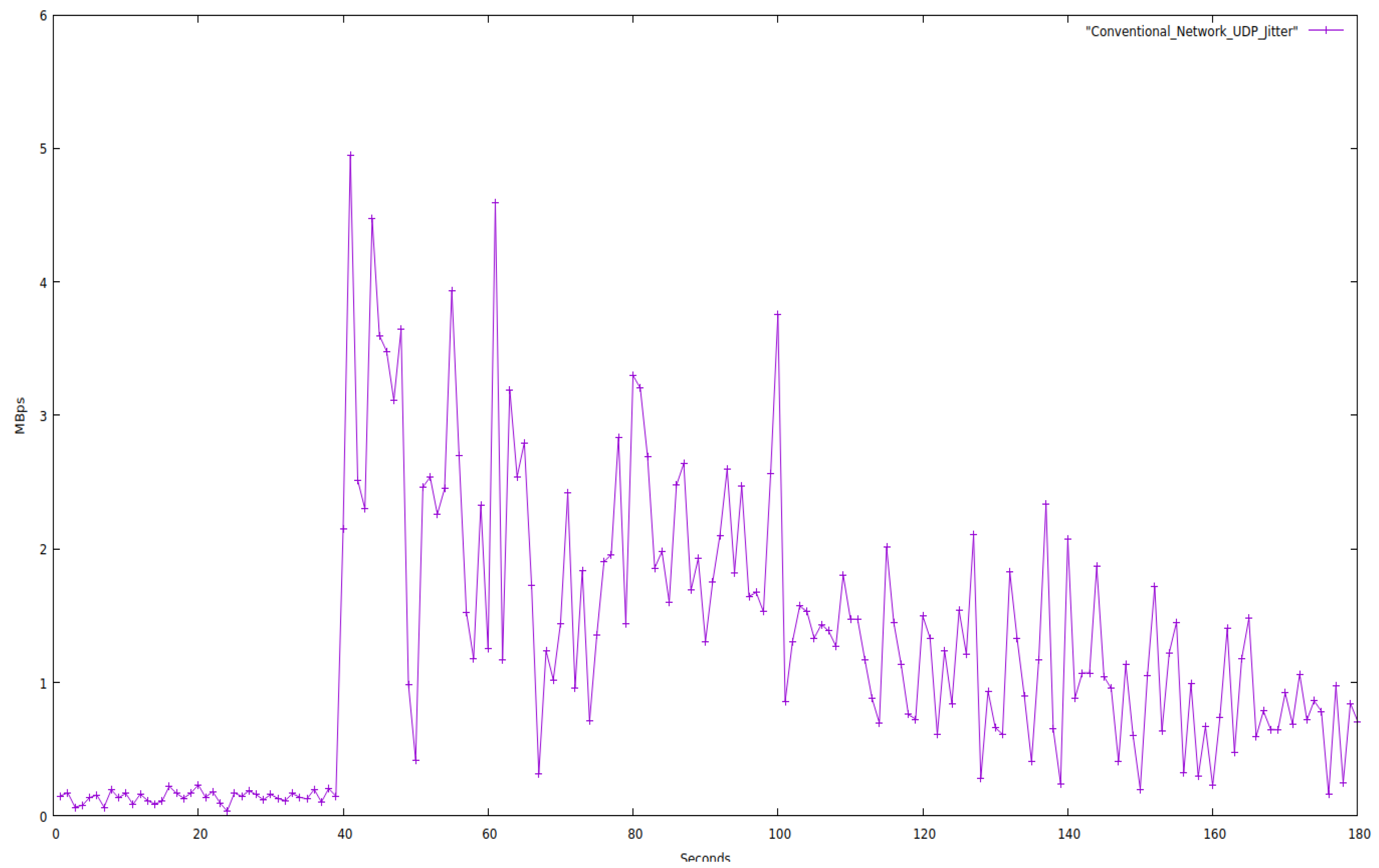

4.4. Traditional UDP Network vs. SDN UDP Network

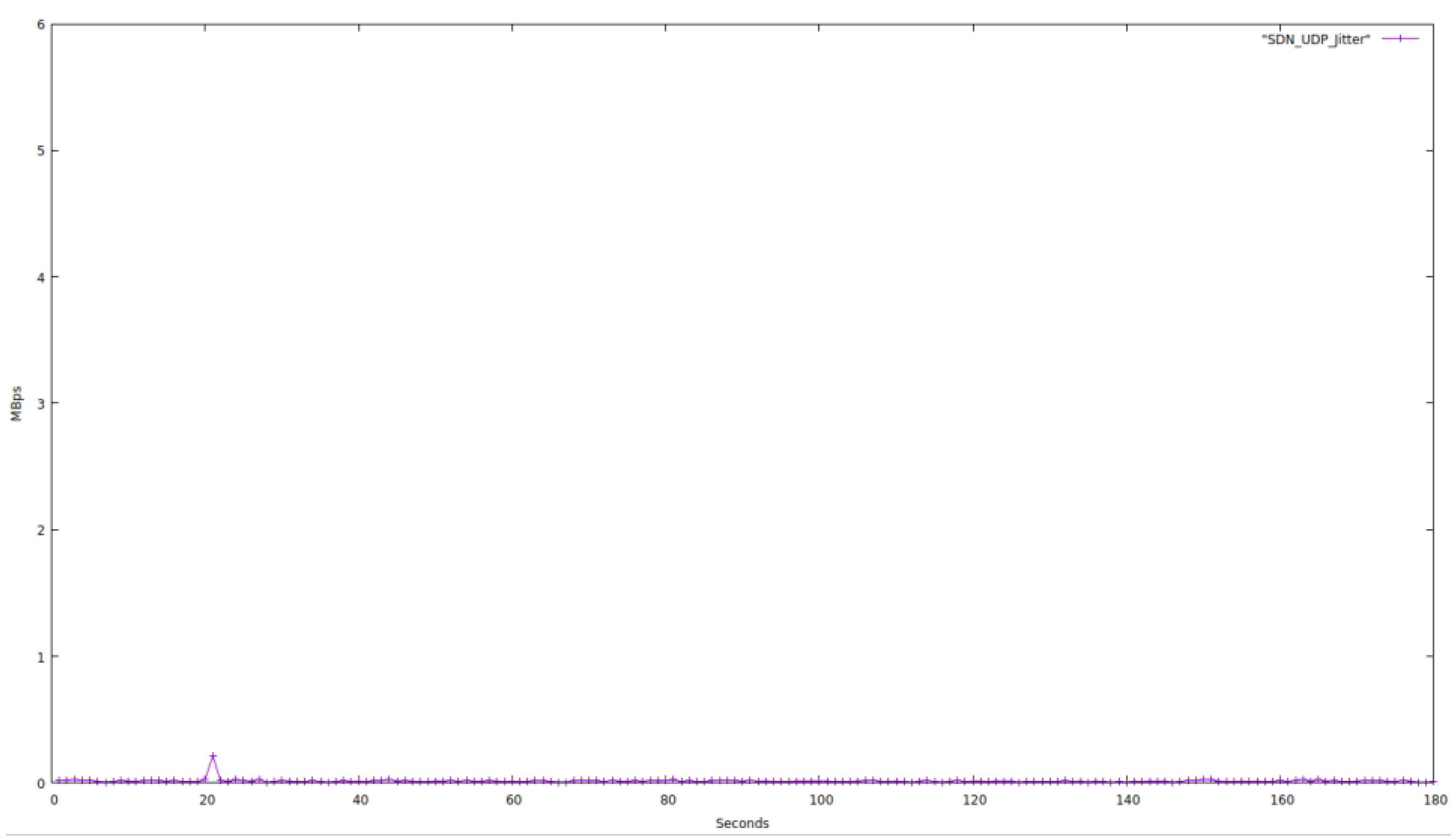

Both networks are evaluated for 180 s while restricting the bandwidth to 1.05 Mbps and solely using UDP protocol packets. The characteristics of the network are depicted in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

We fixed the bandwidth for the aforementioned tests, but how the network uses the bandwidth is up to it. With SDN, the bandwidth remains constant. SDN, i.e., supplies or provides us with a stable network. However, the traditional network’s bandwidth fluctuates significantly, demonstrating that conventional networks are not stable.

The throughput is shown in the above figure, and as we can see, it is constant for the entire testing period for SDN, but it abruptly drops to zero at 182 s. In contrast, we can see that for Traditional Network, the throughput fluctuates and is not even close to being a constant value. We can also see that it still transfers data after 182 s, i.e., it continues to transfer data even after the testing period has ended. This is concrete evidence that SDN is significantly faster than traditional networks.

According to our testing, the average jitter for SDN networks is 0.112 Mbps, which is a meager value. In contrast, the average jitter for Traditional networks was found to be much higher than the corresponding SDN networks. Jitter is the effect we experience when there is a delay in data transfer in a network. For a network to be good, the jitter should be as low as possible.

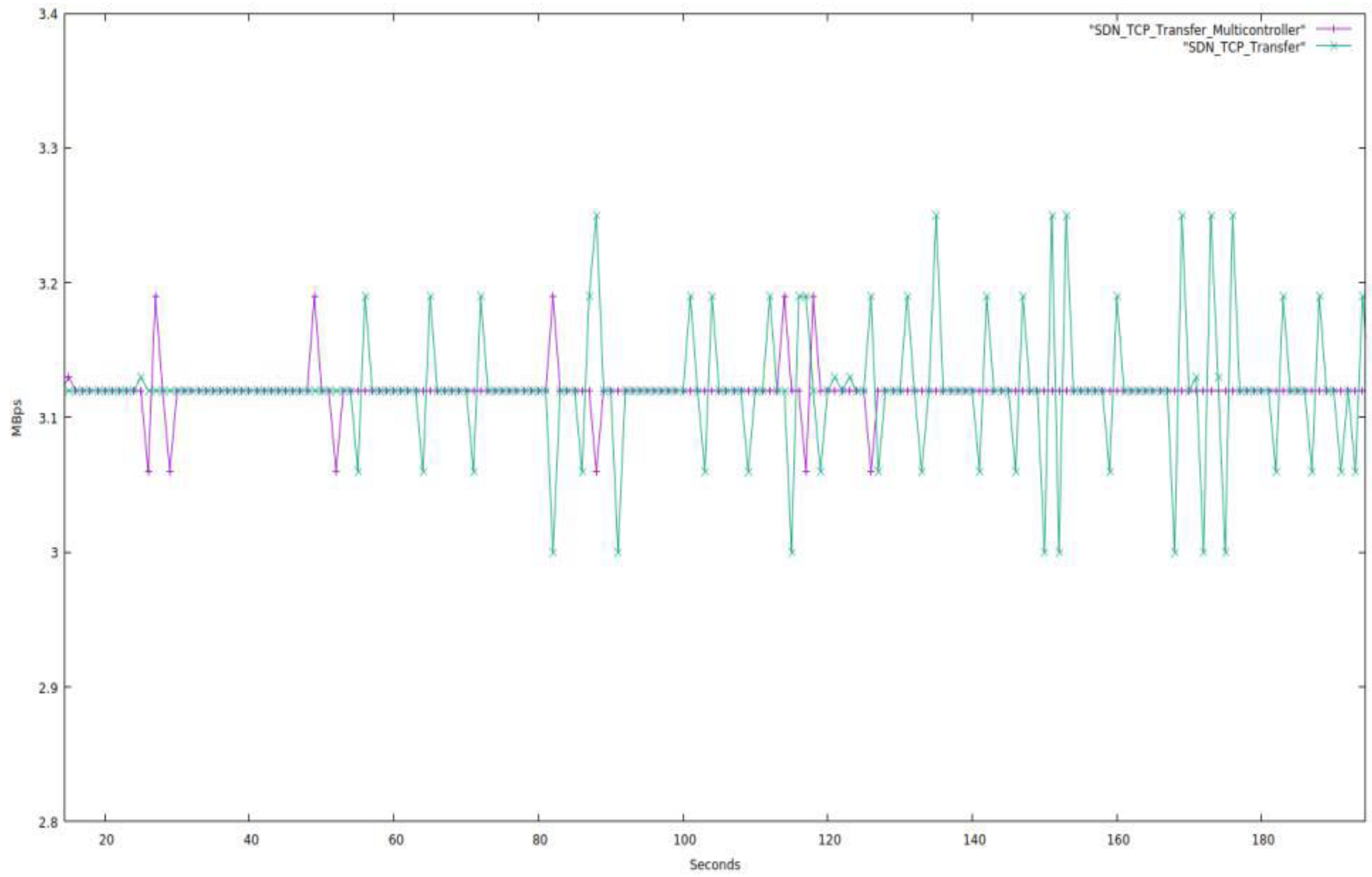

4.5. Single-Controller TCP SDN vs. Multi Controller TCP SDN

In this part, we contrast a topology with just one SDN controller with one with several (in this case, three) SDN controllers. This topology has 34 network devices, including 23 computers, 8 OpenFlow switches, and 3 SDN controllers. The single-controller topology has 32 network devices in total, including 23 computers, 8 OpenFlow switches, and one SDN controller. We tested both networks for 180 s while setting the bandwidth to 26.2 Mbps and using TCP protocol packets. The network characteristics are displayed next in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

Figure 12 shows that both networks’ bandwidth fluctuates in a manner that is essentially the same, with no topology experiencing more significant fluctuations than the others.

Figure 13 shows that both topologies’ data transfer rates are similar and that the multi-controller architecture performs somewhat better than the single-controller topology.

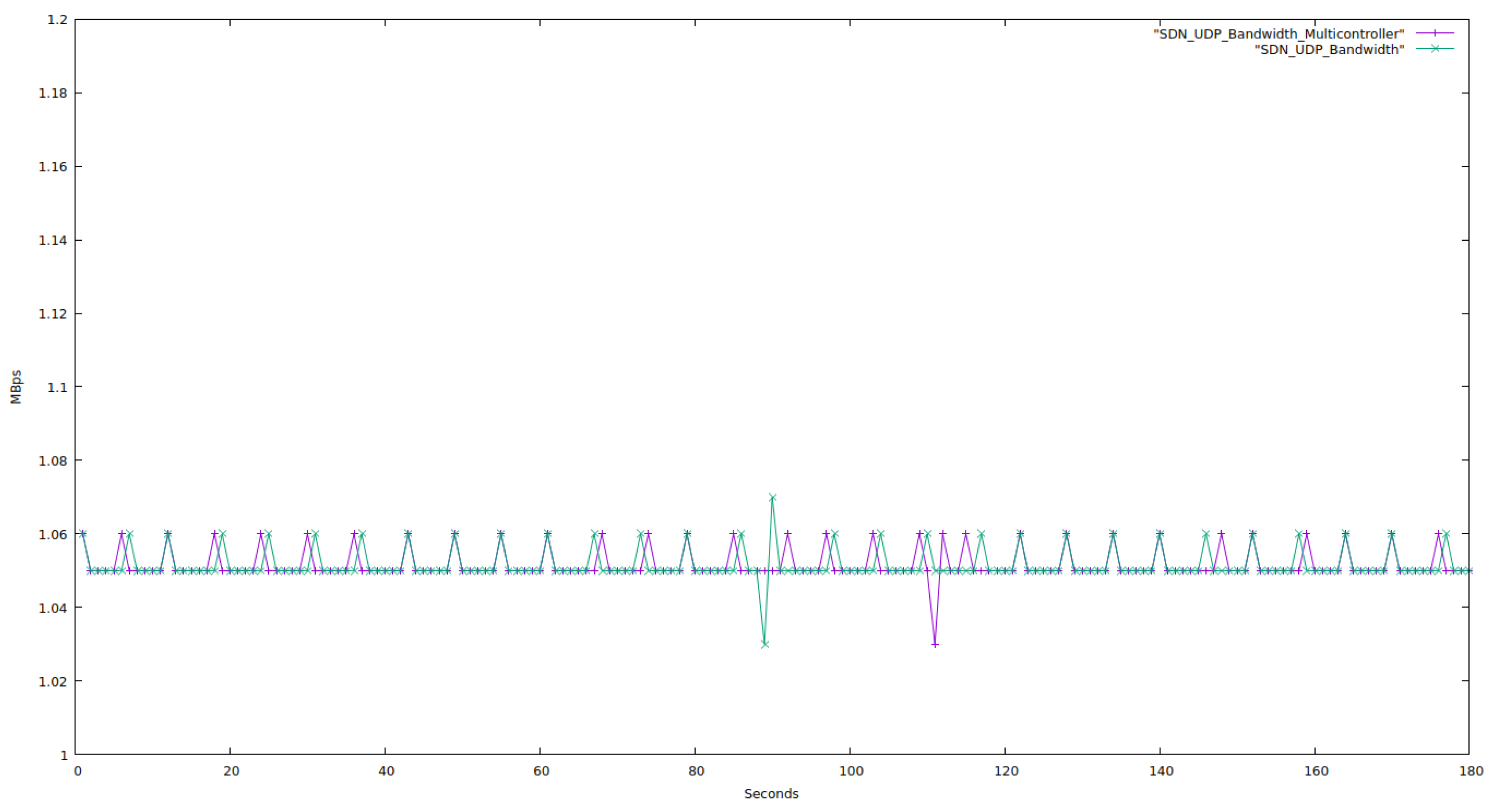

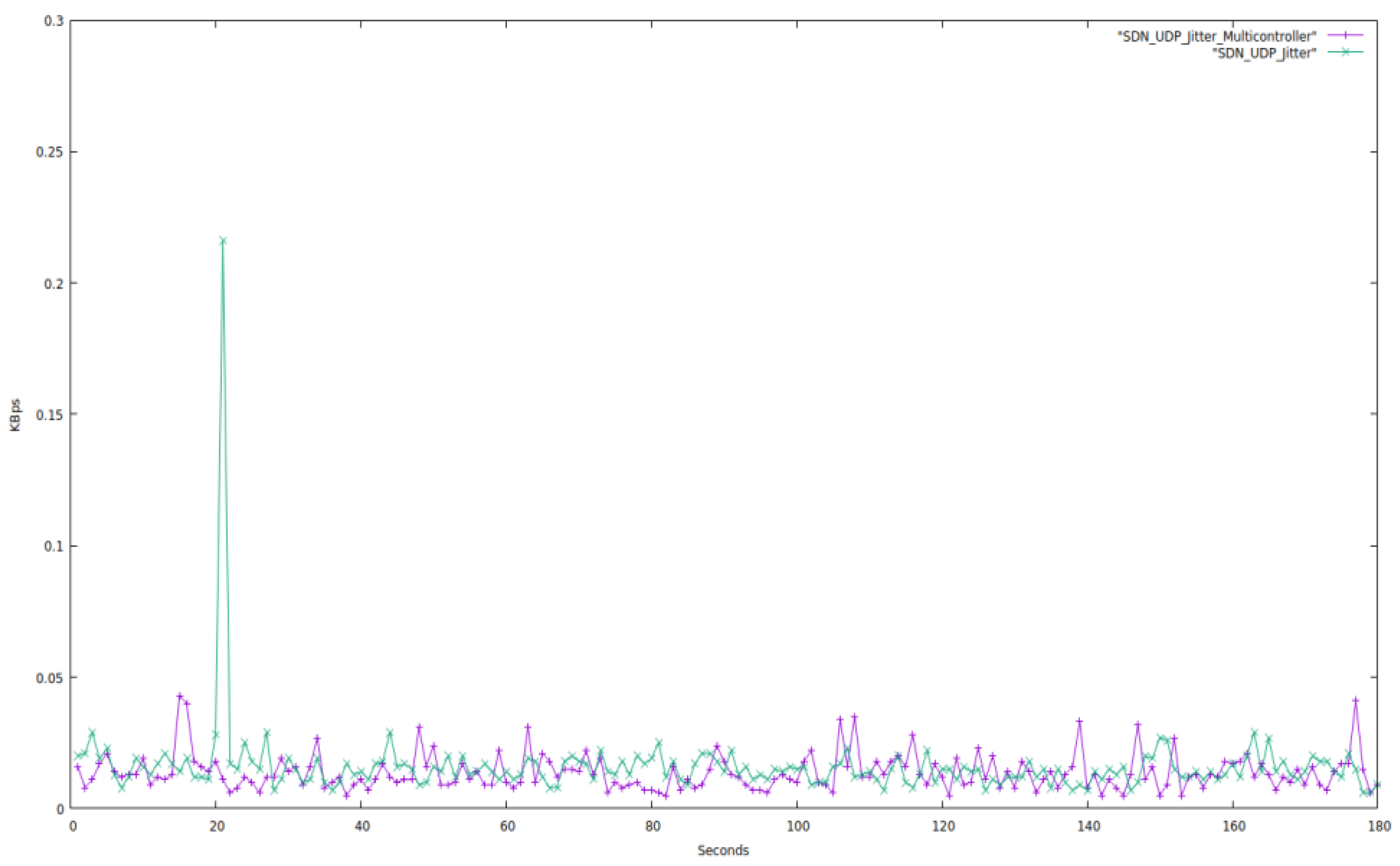

4.6. Single-Controller UDP SDN vs. Multi Controller UDP SDN

In this section, we contrast a topology with a single SDN controller with one with multiple (in this example, three) SDN controllers. In this topology, there are 41 network devices total, including 30 computers, 8 OpenFlow switches, and 3 SDN controllers. In the single-controller topology, there are 39 network devices total, including 30 computers, 8 OpenFlow switches, and one SDN controller. We tested both networks for 180 s while setting the bandwidth to 1.05 Mbps and exclusively using UDP protocol packets.

Figure 14 shows that both topologies—single-controller and multi-controller—show an average fluctuation of 0.01 Mbps, a very negligible fluctuation. As a result, we can conclude that both topologies perform exactly as they should. When compared to the single-controller test network, the multi-controller network performs somewhat better. It follows that a very big network will benefit from the multi-controller’s superior performance.

Figure 15 shows that there is little to no difference in the throughput of the two topologies, indicating that they are both transmitting data at nearly the same pace. This suggests that the two topologies behave at the same pace. Although when compared to the single-controller test network, the multi-controller network performs somewhat better. It follows that a very big network will benefit from the multi-controller’s superior performance.

It is evident from the aforementioned graph that the jitter for both topologies varies, but the average value of jitter for both topologies equals 0.02 Kbps for single-controller SDN and 0.0202 Kbps for multiple controller SDN, which is almost the same. The multi-controller routing information is added to the blockchain. As a result, we can state categorically that multi-controller network topology is superior to a single controller. However, the multi-controller performs better in terms of jitter fluctuation in the event of any breakdown. However, if a single controller quits functioning, the entire network fails.