Abstract

Because of rain attenuation, the equivalent baseband transfer function of large bandwidth radio-links will not be ideal. We report the results concerning radio links to/from satellites orbiting in GeoSurf satellite constellations located at Spino d’Adda, Prague, Madrid, and Tampa, which are all sites in different climatic regions. By calculating rain attenuation and phase delay with the Synthetic Storm Technique, we have found that in a 10-GHz bandwidth centered at 80 GHz (W-Band)—to which we refer to as “ultra-wideband-, both direct and orthogonal channels will introduce significant amplitude and phase distortions, which increase with rain attenuation. Only “narrow-band” channels (100~200 MHz) will not be affected. The ratio between the probability of bit error with rain attenuation and the probability of bit error with no rain attenuation increases with rain attenuation. The estimated loss in the signal-to-noise ratio can reach 3~4 dB. All results depend on the site, Tampa being the worst. To confirm these findings, future work will need a full Monte Carlo digital simulation.

1. GeoSurf Satellite Constellations

The GeoSurf satellite constellations belong to the family of Walker Star Constellations, and they emulate the geostationary orbit with zenith paths for ground stations located at any latitude [1]. The GeoSurf constellations could be a good choice for future worldwide internet radio links because they have most of the advantages of current GEO (Geostationary), MEO (Medium Earth Orbit), and LEO (Low Earth Orbit) satellite constellations without having most of their drawbacks, as seen in Table 1 of [1].

Table 1.

Geographical coordinates, altitude (km), rain height (km), and number of years of continuous rain rate measurements at the indicated sites.

In [2], we compared the tropospheric attenuation of GeoSurf zenith paths with those of GEO, MEO, and LEO satellites. In [3], we compared the relationship between the annual average probability distribution of exceeding a given rain attenuation (dB) and the carrier frequency (GHz) in the GeoSurf paths at sites in different climatic regions with different rainfall statistics. All these studies refer to narrow-band channels, i.e., channels with negligible linear (amplitude and phase) distortions.

In this paper, we estimate the transfer function and linear distortions (amplitude and phase) that are likely to be found in ultra-wideband radio-links to/from satellites orbiting in GeoSurf constellations working at very high frequencies.

As a practical example, we consider a 10-GHz bandwidth centered at 80 GHz (W-Band). We study this very ultra-wideband—we refer to it as “ultra-wideband” to distinguish it from the actual “wideband” which, for the present study, should be considered as “narrowband”—because we think it might be useful in future worldwide internet radio links using spread spectrum modulation and Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) [4,5,6,7,8,9], once high-frequency ultra-wideband technology, now developed at lower frequencies [10], will also be available at W-Band.

CDMA can provide a large processing gain and can be designed without considering issues related to the frequency and access coordination which, together with the advantages of the GeoSurf constellations [1], can be an effective choice to provide high bit rates to users. For example, with a 5-GHz baseband, impulses with raised cosine spectrum and roll-off factor (in the following, we refer to these impulses as the Nyquist impulses), and a coded information bit rate of 50 Mbits per second, being the chip-rate 5 Gbits per second with , the CDMA processing gain would be dB, which is enough to protect a carrier from the interference due to the other CDMA carriers.

The vast literature on what today is termed “wideband” communication systems never refers to rain attenuation, or to the ultra-wideband radio links here supposed, but only to radio links in clear-sky conditions (e.g., faded by multipath, obstructions, etc.), both for terrestrial and satellite systems [4,11,12,13,14,15]; therefore, we are discussing these topics here for the first time, as our previous study involving rain attenuation and phase delay referred to narrow-band satellite systems and deep-space communications [16].

The purpose of this paper is to determine the amplitude and phase distortions produced by rain attenuation in very large bandwidths, in systems specially designed for using double-sideband suppressed-carrier (DSB-SC) modulation, i.e., bipolar phase-shift keying (BPSK), in both quadrature channels (QPSK). We assume that the total signal-to-noise ratio of the Gaussian channel is greater than the minimum required to provide a probability of bit error smaller than the maximum value tolerated by users. In these conditions, we estimate how the in-band attenuation and phase delay due to rainfall affect the baseband digital signal. We evaluate both the output of a direct channel (e.g., the cosine channel) and the interference coming from the quadrature channel (the sine channel, referred to as the orthogonal). Because this the first approach to the topic, we use the average transfer function of direct and orthogonal channels.

For illustrating the general characteristics of linear distortions in very large bandwidths, we report the results concerning the sites listed in Table 1, located in different climatic regions, already studied in [3]. We have considered these specific sites because of the availability of rain-rate time series (mm/h), with rain rate averaged in 1-min intervals, continuously recorded on-site for several years.

After this introduction, in Section 2, we recall the classical theory that transforms a passband transfer function (radio frequency) into the baseband equivalent transfer functions in DSB-SC of direct and orthogonal channels. In Section 3, we show how to calculate attenuation, phase shift, and time delay due to rainfall in zenith paths with the SST. In Section 4, we calculate passband and baseband transfer functions. In Section 5, we report long-term results concerning the transfer functions. In Section 6, we estimate how the non-ideal equivalent baseband transfer function of the direct channel, and the presence of interference coming from the orthogonal channel, may affect the probability of bit error in the direct channel. Finally, in Section 7, we briefly conclude and indicate future work.

2. Passband and Equivalent Baseband Transfer Functions

We review the classical theory of passband (radio frequency) and baseband equivalent transfer functions of direct and orthogonal channels in DSB-SC modulation, applied to orthogonal carriers (QPSK).

Because for the baseband (modulating) signal and the modulation is linear, we can assume that a sinusoidal signal modulates the (direct) carrier , i.e., we can study the transfer function of the equivalent linear direct and orthogonal channels by using the frequency response. Therefore, the modulated signal is given by [18]:

In Equation (1), and are the angular frequencies (radians per second). The two addends are the two side-bands at the angular frequency (lower side-band) and (upper side-band). A similar representation holds for the quadrature (orthogonal) carrier modulated by a sinusoidal signal.

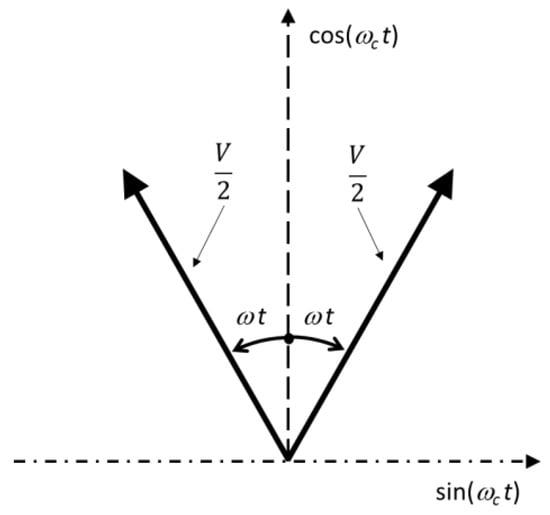

In a Cartesian plane in which the phasors (vectors) at angular speed are fixed (non-rotating), the two side-bands of Equation (1) can be represented by two vectors rotating in phase counterclockwise (upper side-band, positive rotation) and clockwise (lower side-band, negative rotation) with angular speed and , respectively, as seen in Figure 1 [18,19].

Figure 1.

Cartesian plane in which the phasors (vectors) at angular speed are fixed (non-rotating). The two side-bands of Equation (1) can be represented by two vectors rotating in phase counterclockwise (upper side-band, positive rotation) and clockwise (lower side-band, negative rotation) with angular speed and , respectively.

The theory of coherent demodulation followed by a low-pass (base-band) filter (a matched filter) shows that the demodulated signal (direct channel) can be calculated as the sum of the projections of the two side-band vectors on the cosine axis (), and that the projections on the sine axis give the interfering signal that the cosine channel produces in the orthogonal channel ( baseband. Of course, the reverse holds also for a signal modulating .

If the channel is ideal (e.g., radio frequency transfer function is a complex constant), from Figure 1 we can see that the projections on the cosine axis give the undistorted modulating signal . In the orthogonal channel, the coherent demodulator using gives a zero-output signal because the two projections on the sine axis of the vectors shown in Figure 1 are equal in amplitude and opposite in sign. Of course, this is the reason why we can use the sine channel to transmit another signal because in these ideal conditions there is no cross-interference. Interference can arise when the radio frequency transfer function is not ideal, as we show next.

Let the radio frequency transfer function be:

In Equation (2) and are the real and imaginary parts of , and is the generic radio frequency.

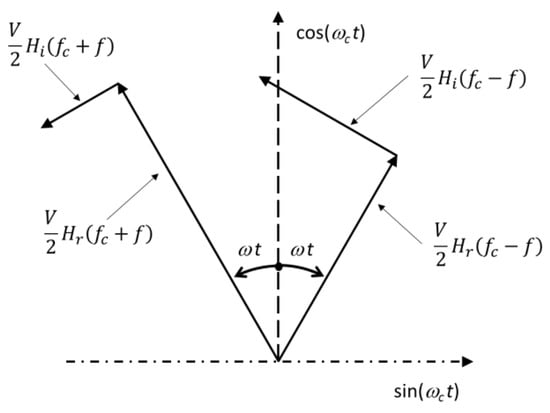

Let us assume that if , there would be a constant phase that would not affect the general analysis. Therefore, the modulated signal at the output of this transfer function is that which is drawn in Figure 2, in which acts on the two side-bands in phase (real axis), while acts on them by producing orthogonal side-bands (imaginary axis). By defining the equivalent baseband transfer function of the direct channel as:

and the equivalent baseband transfer function that couples it to the orthogonal channel:

in which is the baseband frequency, from Figure 2 we calculate the output of the two coherent demodulators by projecting the two side-bands on the cosine axis (direct channel) and on the sine axis (interference). In other words, is the baseband transfer function that couples the cosine channel to the sine channel, therefore producing an output signal in the sine channel due to modulating signal in the cosine channel.

Figure 2.

Cartesian plane in which the phasors (vectors) at angular speed are fixed (non-rotating). The two side-bands of Equation (1) are shown at the output of the medium transfer function. acts on the two side-bands in phase (real axis), while acts on them by producing orthogonal side-bands (imaginary axis).

The projections on the cosine axis give [19]:

The projections on the sine axis give:

The equivalent baseband transfer function that affects the cosine channel because of a modulating signal in the sine channel is given by:

Notice a change of sign in Equation (7) compared to Equation (6).

Now, from Equations (6) and (7), we notice that only if is an odd function of frequency about so that , and only if is an even function of frequency about so that .

In the next section, we calculate these transfer functions for channels faded by rain.

3. Attenuation, Phase Shift, and Time Delay Due to Rainfall in Zenith Paths

When the Synthetic Storm Technique is applied to zenith paths, as those in GeoSurf constellations, the rain attenuation time series lasts exactly as the rain-rate time series, as discussed in [17], as it can be read in Equations (18) and (29) of [17].

The vertical (zenith) structure of precipitation is modelled with two layers of precipitation of different depths. Starting from the ground there is rain (hydrometeors in the form of raindrops with a water temperature of called layer A), followed by a melting layer (melting hydrometeors at 0 °C) called layer B above the rainfall layer and reaching a height of 0 °C. The vertical rain rate R (mm/h, averaged in 1 min) in layer A is assumed to be uniform and given by that which is measured at the ground, i.e., by the rain gauge, . By assuming basic physical hypotheses, calculations show that the vertical precipitation rate in the melting layer, termed “apparent rain rate”, is also uniform and given by [20].

The height of the rainfall above sea level to be used in the simulation is the latest estimate of the ITU-R [21]. The layer B depth is 0.400 km, regardless of the latitude and longitude. Notice that the ITU-R assumes that the depth of the melting layer is 0.360 km, while in the Synthetic Storm Technique, its value is 0.400 km, fixed many years before the ITU-R [20]. Table 2 reports the local precipitation heights for the indicated sites.

Table 2.

Local precipitation height (km) at the indicated sites to be used in the Synthetic Storm Technique. Notice that the depth of Layer B is 0.400 km, which, if added to the local precipitation height of layer A, gives the local precipitation height. For example, at the latitude and longitude of Spino d’Adda, the ITU-R gives 3.341 km, which becomes 3.257 km after subtracting its altitude of 0.084 km.

Now, according to Equation (29) of [17], the rain attenuation (dB) in the zenith path is given by the time-series:

In Equation (1), and are the constants that give the specific rain attenuation - measured in mm/h and in dB per 1 km—in the two layers from the rain rate R measured at the ground, calculated at in layer A and at in layer B.

Similarly, the phase shift (°) in the zenith path is given by the time-series:

The constants , , , and are given in [22]. The time delay (ps) is given by:

In Equation (10), is measured in GHz. See [16] for the application of the time delay due to rainfall in a narrow-band radio links in deep-space communications.

Now, because the relationship between or and is monotonic, the on-site probability distribution is transformed directly into the , of the zenith path through the variable transform given by Equation (9).

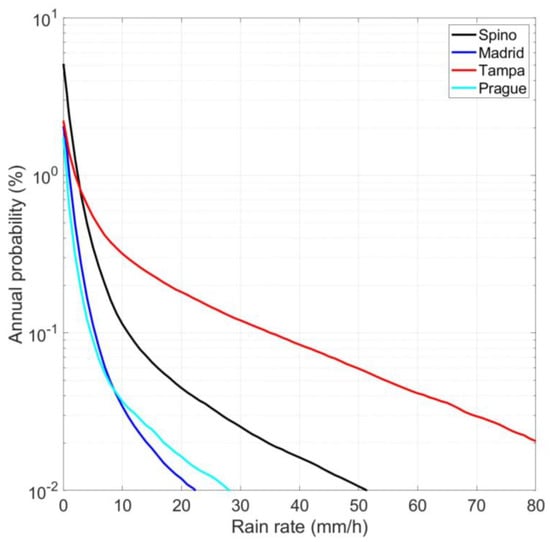

Figure 4 of [3] shows the annual average probability distribution for the sites listed in Table 1. Figure 3 shows the annual probability distribution . The different climatic conditions are clearly evident.

Figure 3.

Annual probability distributions (%) at Spino d’Adda, Madrid, Tampa, and Prague.

Now, from and , the transfer function can be calculated at any time , as we will do in Section 4. Notice that, as is averaged in 1 min, and are also “averaged” in 1 min so that the transfer function refers to 1 min and therefore is changing very slowly compared to any digital signal. In other words, every minute the channel can be considered affected by the same in-band rain attenuation and phase delay. Moreover, we assume that at any time the channel SNR is larger than the minimum required by the probability of bit error constraint; therefore, the rain attenuation to be compensated with power control, or with other techniques, is that measured at the highest frequency of the upper side-band, i.e., at 85 GHz in our exercise. Because our purpose is to study transfer functions, we assume the channel is still working as required; in other words, outages are not considered as they are not directly related to transfer functions.

4. Passband and Baseband Transfer Functions

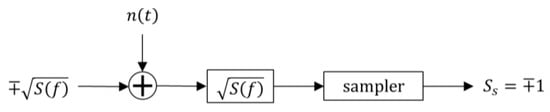

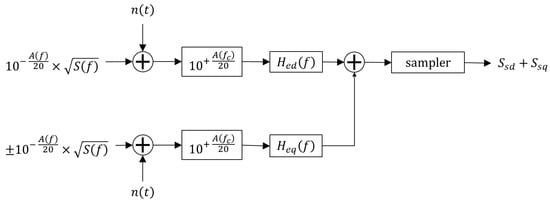

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the baseband receiver in ideal and in rain conditions. is the two-sided spectrum of the Nyquist impulse, is the matched filter, and is the receiver total additive Gaussian white noise.

Figure 4.

Baseband receiver in ideal conditions. is the two-sided spectrum of the Nyquist impulse, is its matched filter, and is the receiver total additive Gaussian white noise.

Figure 5.

Quadrature baseband receiver in rain attenuation. is the two-sided spectrum of the Nyquist reference impulse assumed to be positive, is the matched filter, and is the receiver total additive Gaussian white noise.

In the ideal case (Figure 4), at the output of the sampler, a hard decision gives by sampling the impulse peak at the sampling time .

In the rain attenuation case (Figure 5), and in the following, we suppose that, at any time , the received signal is amplified by multiplying it by to get rid of the variable rain attenuation at the carrier frequency GHz (this is not related to the outage condition discussed above). By doing so, we leave only the in-band signal variations about the carrier frequency, which is the effect we aim to study. At the output of the sampler, before the hard decision, there is the algebraic sum of direct and orthogonal channel samples found at the reference time , corresponding to the peak value of the direct and orthogonal channel impulses present simultaneously. In general, however, both values are affected by self- and orthogonal-channel interference due to the tails of the previous and following impulses, an issue that is beyond the purpose of this paper (see Section 6).

In the following, we consider the relative phase shift (degrees):

(this definition sets and the relative time delay:

Defined the normalized magnitude of the passband transfer function , at time as:

the real and imaginary parts of are given by

From Equation (14), Equation (5) (direct channel), and Equation (7) (orthogonal channel interference), we can calculate the baseband equivalent transfer functions.

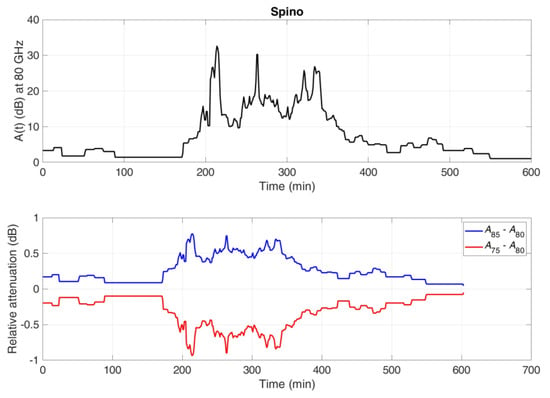

An example illustrates calculations and findings. Figure 6 shows an SST-simulated rain attenuation event at Spino d’Adda at 80 GHz and the relative rain attenuation at the extremes of the 10-GHz bandwidth centered at 80 GHz. In this particular event, the maximum rain attenuation is 32.6 dB and at the extremes of the bandwidth, it can change by about dB. This behavior is, of course, due to the increase in rain attenuation with frequency, and this fact can produce amplitude distortions in baseband signals.

Figure 6.

SST-simulated rain attenuation event at Spino d’Adda at 80 GHz (8 May 2000, starts at 0:48 AM local time). Upper panel: Rain attenuation at 80 GHz (circular polarization). Lower panel: Relative attenuation at the extreme of a 10-GHz bandwidth.

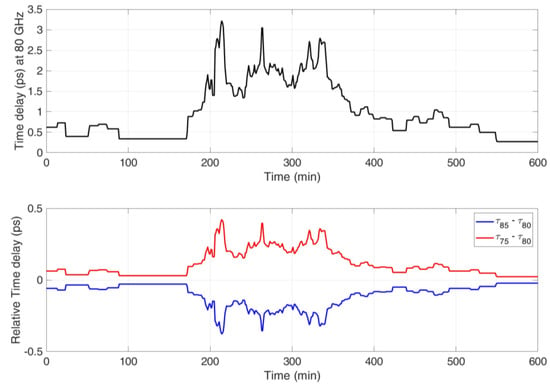

Figure 7 shows the time delay at 80 GHz and the relative time delay at the extremes of the bandwidth. The time delay is very small, as was also shown in [16], but more importantly, it is not a constant across the bandwidth, and this fact can produce phase distortions in the baseband signal.

Figure 7.

SST-simulated rain attenuation event at Spino d’Adda at 80 GHz GHz (8 May 2000, starts at 0:48 AM local time). Upper panel: Time delay at 80 GHz (circular polarization). Lower panel: Relative time delay at the extreme of a 10-GHz bandwidth.

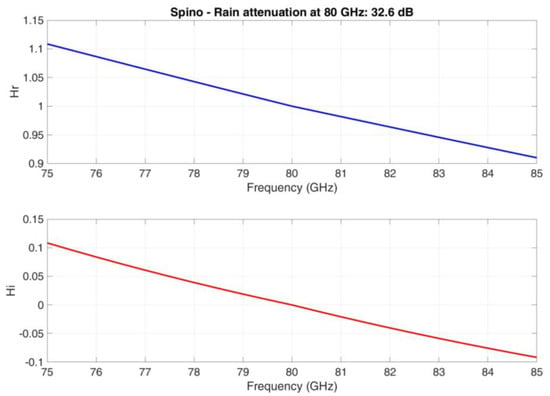

For this particular rain event, we have calculated the instantaneous (1-min) passband transfer function at the time of maximum rain attenuation. Figure 8 shows the real and imaginary parts of the passband transfer function, as shown in Equation (12).

In Figure 8, we can observe that is neither a constant nor an even function about ; therefore, the output of the direct channel is distorted in amplitude. is, to a first approximation, a linear odd function; therefore, the output of the direct channel should be lightly distorted in phase at this particular time. As for the interference produced by the orthogonal channel on the direct channel (cosine), it will be present because also in this channel, , as observed, is not an even function. might produce a small phase distortion.

In the next section, we report averages and standard deviations of passband and equivalent baseband transfer functions for several rain attenuation ranges. These data will be needed to compensate, on average, for these linear distortions.

5. Long-Term Results

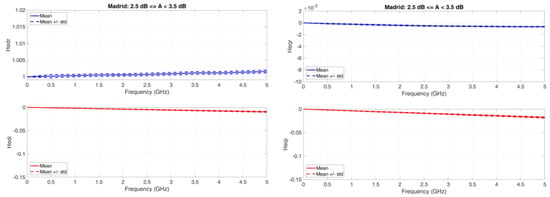

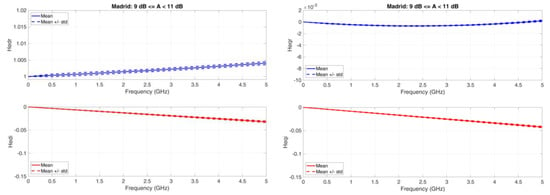

By applying the theory of Section 2 to all rain events collected at the sites of Table 1, in this section, we show the average and standard deviations of passband and equivalent baseband transfer functions for several rain attenuation ranges for Spino d’Adda. The results concerning the other sites are reported in Appendix A.

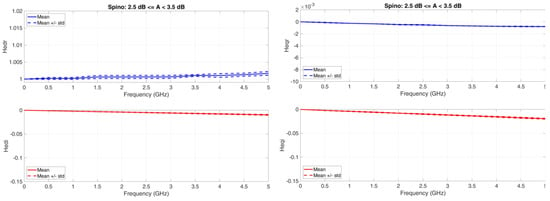

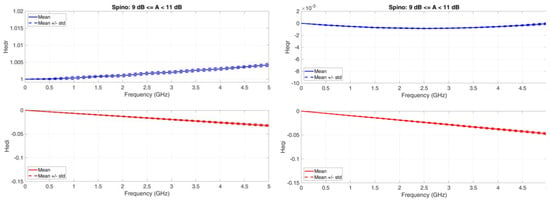

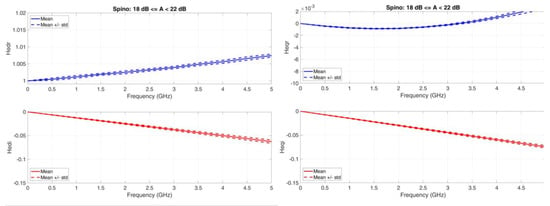

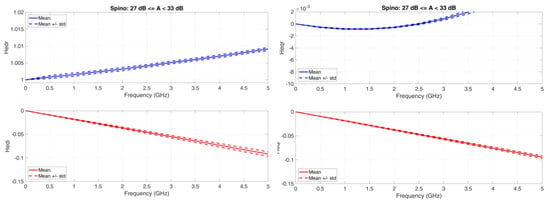

Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the equivalent baseband transfer functions for rain attenuation centered at 3, 10, 20, and 30 dB to show the differences as attenuation increases. Notice that in these Figures we have always adopted the same scales to allow comparisons.

Figure 9.

Spino d’Adda. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the cross-channel.

Figure 10.

Spino d’Adda. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the cross-channel. A < 11 dB.

Figure 11.

Spino d’Adda. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the cross-channel. A < 22 dB.

Figure 12.

Spino d’Adda. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the cross-channel. A < 33 dB.

We can observe the following general features.

: it is not constant; it increases with attenuation range; the standard deviation is small. It will produce different amplitude distortions in different attenuation ranges.

: it is practically a straight line, but its slope increases (more negatives) with attenuation range; the standard deviation is small. It will produce different phase distortions and, therefore, different time delays as the attenuation range increases.

: it is of the order of of ; it is not constant; it increases with attenuation range; the standard deviation is small. It will produce different amplitude distortions in different attenuation ranges.

: it is practically a straight line, but its slope increases (more negative) with attenuation range; the standard deviation is small. Its magnitude is larger than . It will produce different phase distortions and different time delays as the attenuation range increases.

In conclusion, both the direct channel and the cross channel will introduce amplitude and phase distortions, which depend on attenuation range, in a 10-GHz bandwidth centered ta 80 GHz. Only the channels defined here as narrow band ( MHz) will not be affected. In the next Section, we will present and discuss the likely effects on the probability of bit error.

6. Probability of Bit Error

We estimate how the non-ideal equivalent baseband transfer function of the direct channel, and the presence of interference coming from the orthogonal channel, affect the probability of bit error in the direct channel. We compare the ideal case, i.e., no rain attenuation, to the case with rain attenuation. We assume a Nyquist impulse with roll-off factor and consider only the amplitude and phase distortions due to two simultaneous impulses present in the direct and orthogonal channels. In other words, we do not consider the interference due to several contiguous impulses in the direct and cross-channels. As we assume , the tails of these contiguous impulses should be at a minimum; however, only a full Monte Carlo simulation with actual random sequences of bits would give a clearer insight into the effects of these linear distortions. This issue will be the topic of future work.

For assessing how the non-ideal equivalent baseband transfer function of the direct channel and the presence of interference affect the probability of bit error in the direct channel, we have calculated the ratio between the probability of bit error with rain attenuation, and probability of bit error , , , with no rain attenuation:

In other words, with , we compare the probability of bit error due to the SNR in ideal conditions to that due to the SNR in rain conditions, by assuming the same system noise. Usually , and rarely .

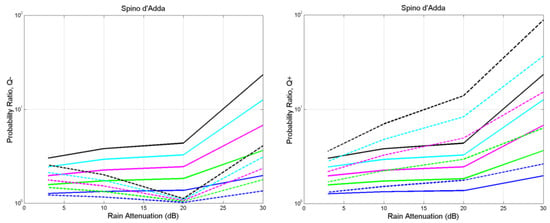

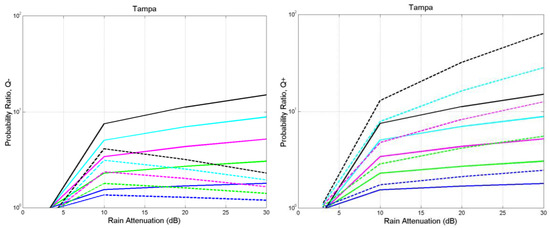

For these calculations, we have first considered the average transfer functions. Figure 13 shows the results obtained in two cases: (a) without interference and (b) with interference due to an impulse with the opposite sign of that of the direct channel (assumed positive); and with interference due to an impulse with the same sign of that of the direct channel, at Spino d’Adda. In other words, these two cases, at least for the average transfer functions, give the lower and upper bounds to . Appendix B shows similar results for the other sites.

Figure 13.

Spino d’Adda. Probability ratio between the probability of bit error with rain and the probability of bit error with no rain (ideal case): , , , . Direct case: continuous lines; with interference: dashed lines. Left: negative interfering impulse; Right: positive interfering impulse.

We can observe the following general features. With no interference, increases as rain attenuation increases. With interference, there are significant differences as tends to decrease when the impulses are of different signs and tends to increase when the impulses are of the same sign, which was not expected, therefore implying a significant amplitude distortion of the interfering impulse coming from the cross channel, as seen in Equation (7). In other words, at the sampling time , the interfering impulse may not be at its maximum value.

When the impulses are of opposite sign, approaches a minimum value at dB. With impulses of equal sign, at , at , and at . In all cases, increases as decreases.

Now, as a decade increase in the probability of bit error means an equivalent reduction of roughly 1 dB in the SNR [18,19], we can conclude that, considering only average transfer functions, the linear distortions due to rain can give rise to an average loss of dB in the radio link budget in a 10-GHz bandwidth.

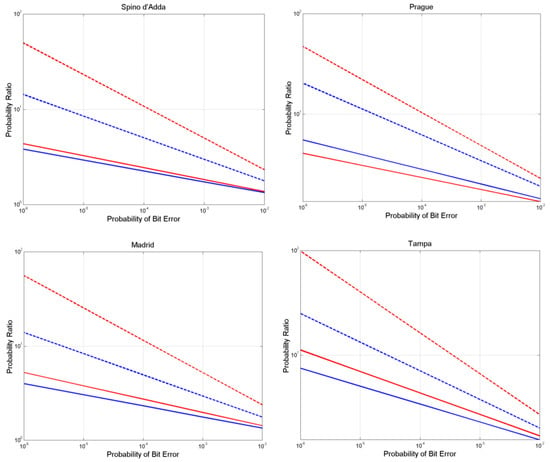

If we consider the SNR variations of standard deviation about the average SNR (i.e., the SNR gets smaller) more loss is found in the direct channel with no interference. Figure 14 shows the findings. Now, we can notice that even without interference, at . At Tampa, it can even reach, for dB at , therefore giving and an SNR loss of about 2 dB just for these variations. If we also consider interference, the loss can reach dB.

Figure 14.

Probability ratio between the probability of bit error with rain and the probability of bit error with no rain (ideal case) vs. probability of bit error in the direct channel with no interference, according to the average SNR (continuous lines) and standard deviation of SNR (dashed lines), at Spino d’Adda, Prague, Madrid, Tampa. Blue lines, dB; red lines, dB.

7. Conclusions

Because of rain attenuation, the equivalent baseband transfer functions of ultra-wideband radio-links to/from satellites orbiting in GeoSurf satellite constellations will not be ideal. We have evaluated both the output of a direct channel and the interference coming from the orthogonal channel.

By calculating the rain attenuation and phase delay with the Synthetic Storm Technique, we have found that in a 10-GHz bandwidth centered at 80 GHz, possibly used in future internet services with spread-spectrum coding techniques, both direct and orthogonal channels will introduce significant amplitude and phase distortions, both increasing with rain attenuation. Only “narrow band” channels ( MHz) will not be significantly affected.

We have found that the ratio between the probability of bit error with rain attenuation and the probability of bit error with no rain attenuation increases as rain attenuation increases. If interference is present, there are significant differences as tends to decrease when the impulses are of different signs and tends to increase when the impulses are of the same sign, an unexpected result that should be due to a significant amplitude distortion of the interfering impulse coming from the orthogonal channel.

We have found that, considering only average transfer functions and no interference from the cross channel, the linear distortions can give rise to an average loss of dB in the SNR radio link budget. If the cross-channel interference is also considered, the loss can reach dB. All results depend on the site, Tampa being the worst one.

Future work will run a full Monte Carlo digital simulation to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and C.R.; methodology, E.M. and C.R.; software, E.M. and C.R.; investigation, E.M. and C.R.; data curation, E.M. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and C.R.; writing—review and editing, E.M. and C.R.; visualization, E.M. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Roberto Acosta, at NASA years ago, for providing the rain rate data of Tampa; Ondrej Fiser, Institute of Atmospheric Physics in Prague, for providing the rain rate data of Prague; and José Manuel Riera, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, for providing the rain rate data of Madrid.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Long-Term Equivalent Baseband Transfer Functions at Madrid, Prague, and Tampa

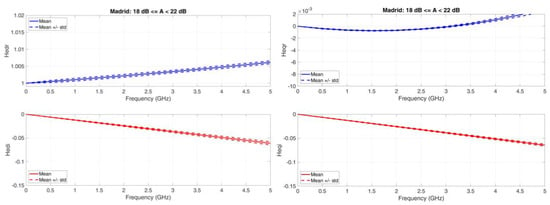

Madrid. Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4 show the equivalent baseband transfer functions for rain attenuation centered at 3, 10, 20, and 30 dB.

Figure A1.

Madrid. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A2.

Madrid. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 11 dB dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

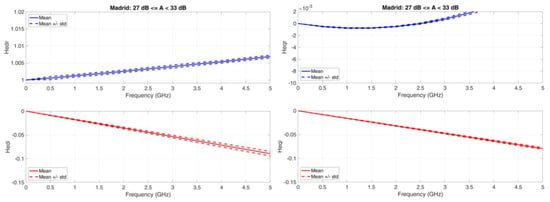

Figure A3.

Madrid. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 22 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A4.

Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 33 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

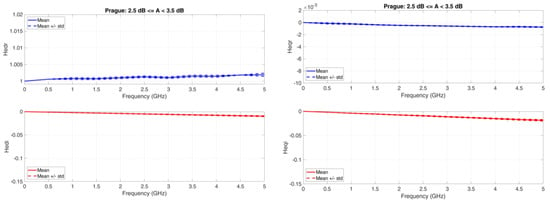

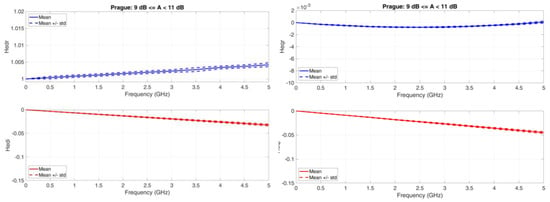

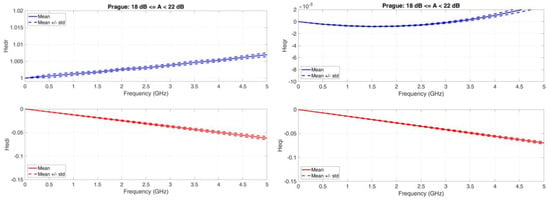

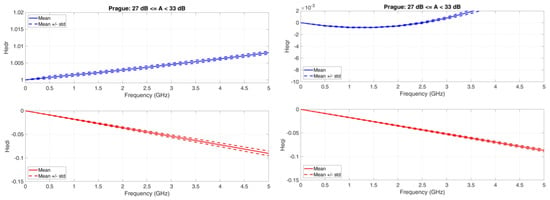

Prague. Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7 and Figure A8 show the equivalent baseband transfer functions for rain attenuation centered at 3, 10, 20, and 30 dB.

Figure A5.

Prague. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A6.

Prague. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 11 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A7.

Prague. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 22 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A8.

Prague. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 33 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

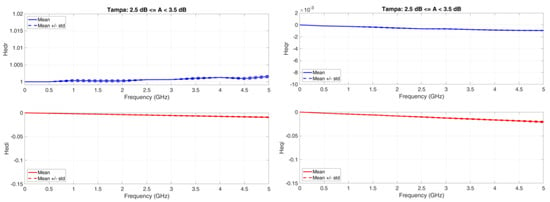

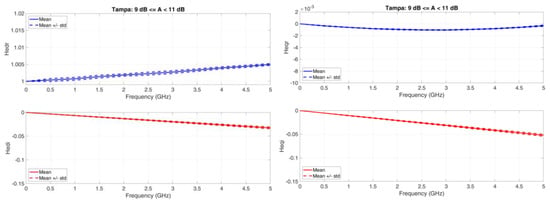

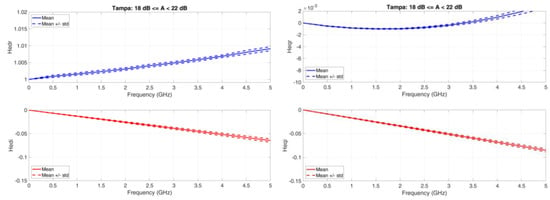

Tampa. Figure A9, Figure A10, Figure A11 and Figure A12 show the equivalent baseband transfer functions for rain attenuation centered at 3, 10, 20, and 30 dB.

Figure A9.

Tampa. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 3.5 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A10.

Tampa. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 11 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A11.

Tampa. Average value (continuous line) and ±1 no standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 22 dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

Figure A12.

Tampa. Average value (continuous line) and standard deviation (dashed lines) baseband equivalent transfer functions in the range A < 33 dB. dB. Left column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the direct channel; Right column: Real (upper panel) and Imaginary (lower panel) transfer functions of the orthogonal channel.

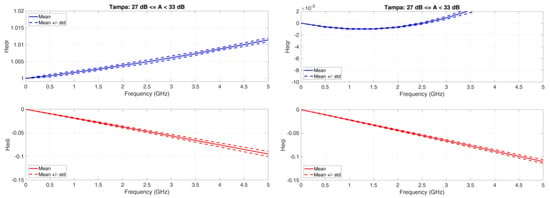

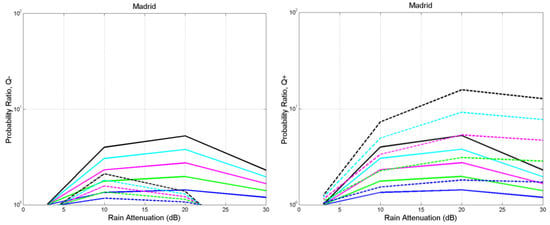

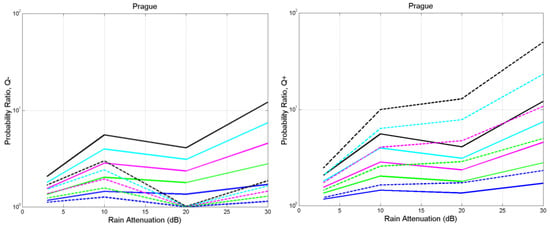

Appendix B. Long-Term Probability Ratio at Madrid, Prague, and Tampa

Figure A13, Figure A14 and Figure A15 show the probability ratio versus rain attenuation for Madrid, Prague and Tampa, respectively.

Figure A13.

Madrid. Probability ratio between the probability of bit error with rain and the probability of bit error with no rain (ideal case): , , , . Direct case: continuous lines; with interference: dashed lines. Left: negative interfering impulse; Right: positive interfering impulse.

Figure A14.

Prague. Probability ratio between the probability of bit error with rain and the probability of bit error with no rain (ideal case): , , , . Direct case: continuous lines; with interference: dashed lines. Left: negative interfering impulse; Right: positive interfering impulse.

Figure A15.

Tampa. Probability ratio between the probability of bit error with rain and the probability of bit error with no rain (ideal case): , , , . Direct case: continuous lines; with interference: dashed lines. Left: negative interfering impulse; Right: positive interfering impulse.

References

- Matricciani, E. Geocentric Spherical Surfaces Emulating the Geostationary Orbit at Any Latitude with Zenith Links. Future Internet 2020, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C.; Luini, L. Tropospheric Attenuation in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C. Outage Probability versus Carrier Frequency in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations with Radio-Links Faded by Rain. Telecom 2022, 3, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S. Fading Dispersive Communication Channels; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Turin, G.L. Introduction to spread spectrum antimultipath techniques and their application to urban digital radio. Proc. IEEE 1980, 68, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickholtz, R.; Schilling, D.; Milstein, L. Theory of spread-spectrum communications—A tutorial. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1982, 30, 855–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viterbi, A.J. CDMA Principles of Spread Spectrum Communications; Addinson-Wesly: Reading, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, E.H.; Jabbari, B. Spreading codes fir direct sequence CDMA and wideband CDMA celluar networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 1998, 36, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeravalli, V.V.; Mantravadi, A. The coding-spreading trade-off in CDMA systems. IEEE Trans. Sel. Areas Commun. 2002, 20, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsusaki, Y.; Masafumi, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Susumu, N.; Kamei, M.; Hashimoto, A.; Kimura, T.; Tanaka, S.; Ikeda, T. Development of a Wide-Band Modem for a 21-GHz Band Satellite Broadcasting System. In Proceedings of the IEEE Radio and Wireless Symposium, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 19–23 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, D. The Mobile Radio Propagation Channel; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M.K.; Alouini, M.S. Digital Communication over Fading Channels: A Unified Approach to Performance Analysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein, L.G.; Andersen, J.B.; Bertoni, H.L.; Kozono, S.; Michelson, D.G. (Eds.) Special Issue on Channel and Propgation Modeling for Wireless Systems Design. J. Sel. Areas Communictions 2002, 20, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A. Wireless Communications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fontan, F.; Pastoriza-Santos, V.; Machado, F.; Poza, F.; Witternig, N.; Lesjak, R. A Wideband Satellite Maritime Channel Model Simulator. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2022, 70, 214–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. A Relationship between Phase Delay and Attenuation Due to Rain and Its Applications to Satellite and Deep-Space Tracking. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2009, 57, 3602–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Physical-mathematical model of the dynamics of rain attenuation based on rain rate time series and a two-layer vertical structure of precipitation. Radio Sci. 1996, 31, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M. Information, Transimission, Modulation and Noise, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Int.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carassa, F. Comunicazioni Elettriche; Bollati Boringhieri: Turin, Italy, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani, E. Rain attenuation predicted with a two-layer rain model. Eur. Tranactions Telecommun. 1991, 2, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendation ITU-R P.839-4. Rain Height Model for Prediction Methods; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori, D. Computed transmission through rain in the 1-400 GHz frequency range for spherical and elliptical drops and any polarization. Alta Frequenza. 1981, 50, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).