Classification Framework of Introduced Crabapple (Malus spp.) Cultivars Based on Morphological and Numerical Traits: Insights for Germplasm Conservation and Landscape Forestry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Trait Documentation

- Floral traits (23 indicators): inflorescence type, flower type (single, semidouble, double) (Figure 1), petal number, petal shape, petal margin, flower color, bud color, flower size, fragrance, sepal shape and margin (including eriocalyx type with hairy edge sensu Rehder 1927 [15]), pistil position, stamen fertility.

- Leaf traits (12 indicators): young leaf color, mature leaf shape (Figure 2), margin, venation, pubescence, petiole length, lamina texture.

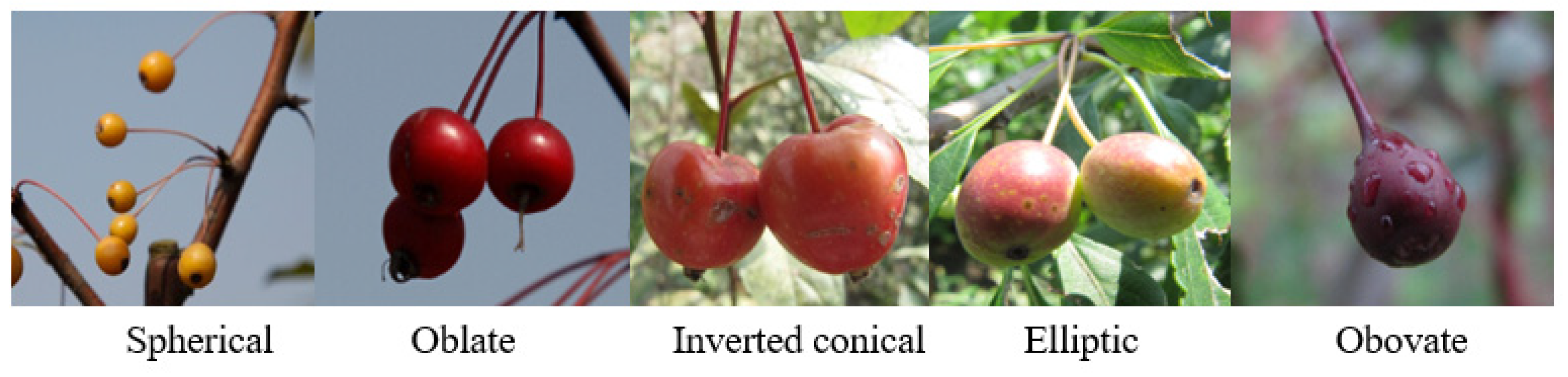

- Fruit traits (12 indicators): shape (Figure 3), size, surface gloss, color, fruit pedicel length and orientation, calyx persistence, seed number.

- Tree and bark traits (8 indicators): plant habit (tree, shrub), crown shape, branch density, thorn presence, bark color, trunk form.

2.3. Classification Criteria

2.4. Numerical Taxonomy

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Classification Framework

3.2. Key Diagnostic Traits

- Flower color was highly reliable for further subgrouping, with little annual variation.

- Fruit traits (shape, calyx persistence, pedicel orientation) provided auxiliary criteria, especially for distinguishing cultivars with similar floral morphology.

- Leaf characters, although variable under different environments, still contributed to the recognition of specific cultivars (e.g., M. ‘Adirondack’ with narrow elliptic leaves).

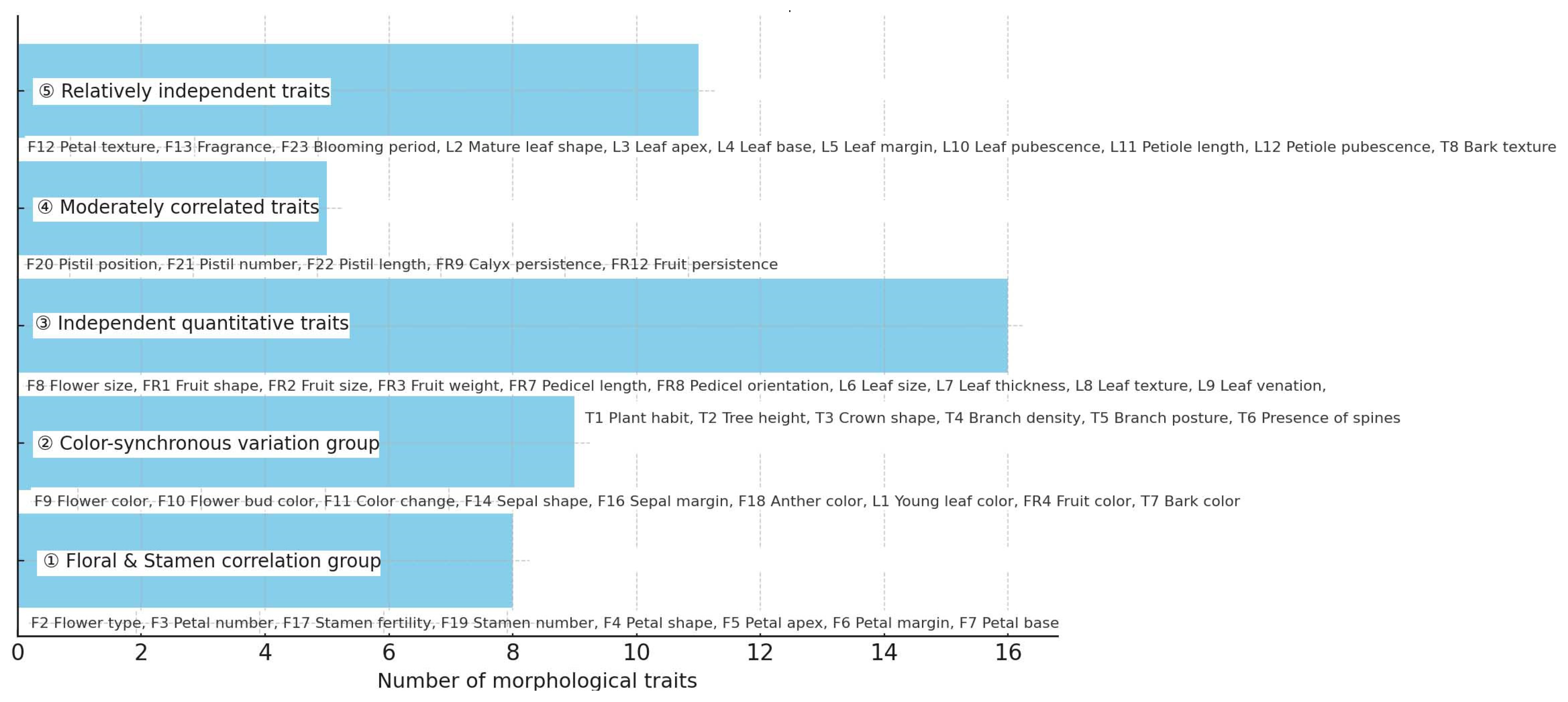

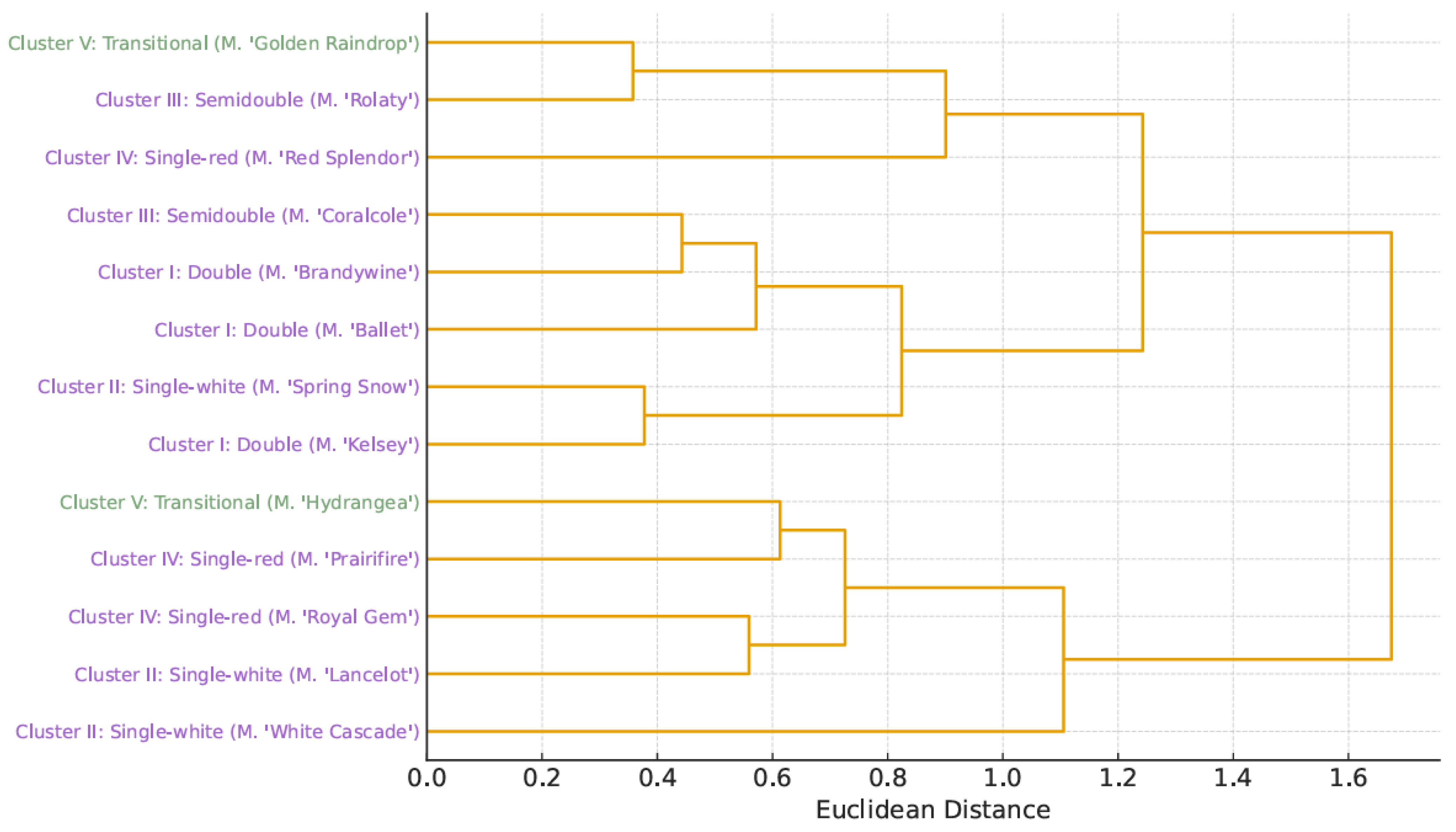

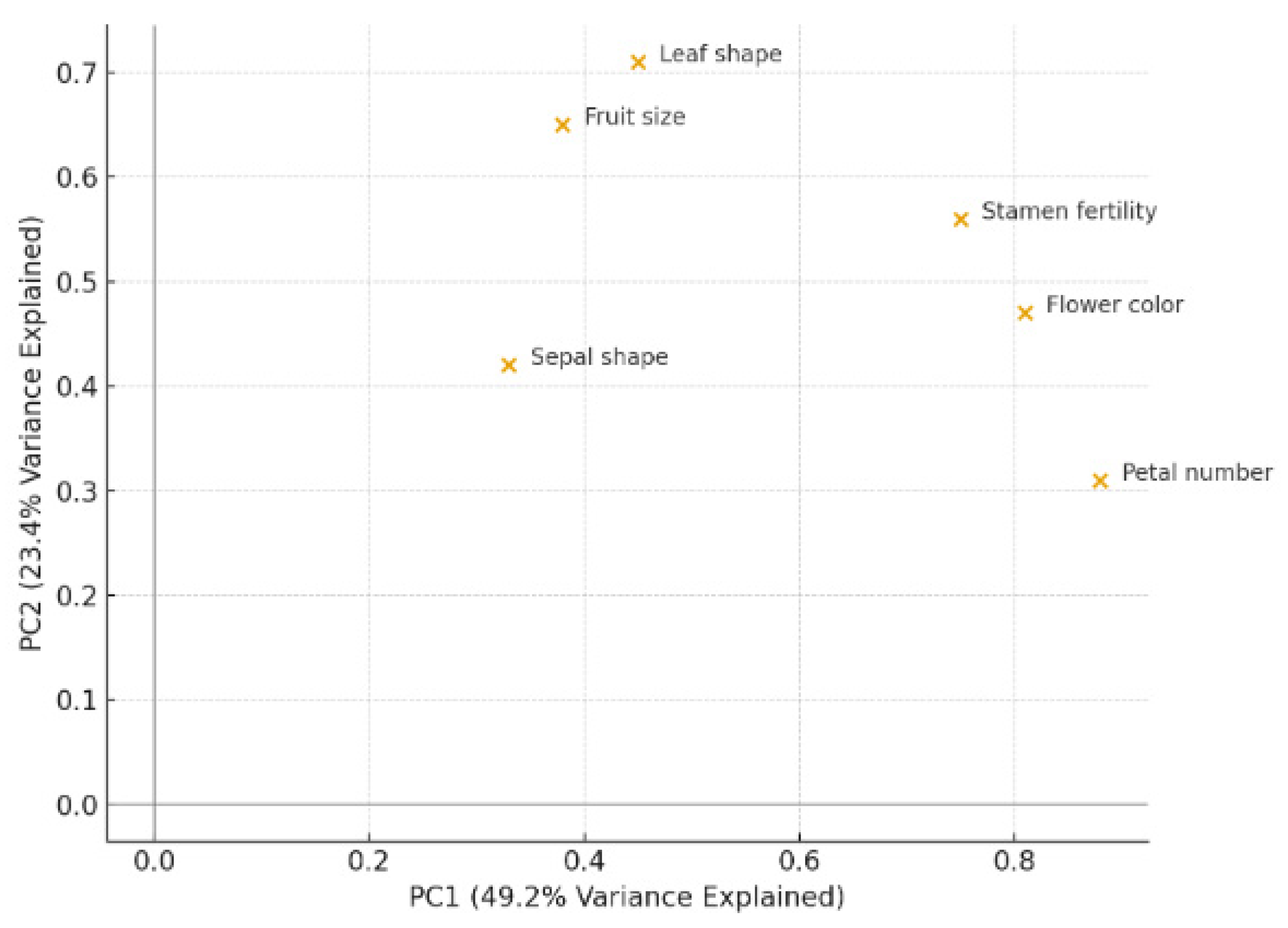

3.3. Numerical Taxonomy Analysis

3.4. Concordance with International Systems

3.5. International Comparison of Classification Approaches

4. Discussion

4.1. Horticultural and Forestry Validation of Classification

4.2. Implications for Germplasm Conservation and Nursery Practice

4.3. Contribution to Breeding Programs and International Germplasm Exchange

4.4. Toward a Globally Harmonized Classification Framework

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong, R.; Zhang, C.Y.; Feng, S.C. Ornamental Germplasm Resources of Crabapple and Their Utilization. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2019, 35, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Shen, X.; Zhou, D.; Fan, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, W.; Cao, F. Advances in the Classification of Crabapple Cultivars. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2018, 45, 380. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, T.; Fan, J.; Lu, X. ‘Yanyu Jiangnan’ Crabapple. HortScience 2023, 58, 588–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, T.; Fan, J.; Sun, T. ‘Yunjuan Yunshu’ Flowering Crabapple. HortScience 2023, 58, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W. ‘Yi Honglian’ Flowering Crabapple. HortScience 2022, 57, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.Q.; Sha, G.L.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.T.; Sun, J.L.; Ge, H.J.; Zhang, R.F. Breeding of a New Crabapple Cultivar ‘Datangqinhong’. China Fruits 2024, 48, 150–151. [Google Scholar]

- Goncharovska, I.; Vladimyr, K.; Antonyuk, G.; Dan, C.; Sestras, A.F. Flower and Fruit Morphological Characteristics of Different Crabapple Genotypes of Ornamental Value. Not. Sci. Biol. 2022, 14, 10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X. Progress in the Taxonomic Studies of the Genus Malus. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.M. The Breeding and Cultivating of 33 Europe Malus Species or Cultivars and Their Ornamental. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.W.; Jing, Q.; Jiang, J.H.; Liang, W.H.; Liang, C.F.; Guo, T.G. Studies on Dynamic Characteristics of the Pigment Components of Ornamental Crabapple Cultivars Groups in Flowering Process. Hortic. Plant J. 2014, 41, 1145. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N.; Jiang, W.; Wang, M. Landscape Characters of the Main Species of Malus and Chaenomeles. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2006, 22, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, S. Ornamental Crabapple: Present Status of Resources and Breeding Direction. In Proceedings of the International Apple Symposium, Shenyang, China; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ze, Q.G.; Guo, T.G. A Review on the Plant Taxonomic Study on the Genus Malus Miller. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 29, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.P.; Harris, S.A.; Juniper, B. Taxonomy of the Genus Malus Mill. (Rosaceae) with Emphasis on the Cultivated Apple, Malus domestica Borkh. Plant Syst. Evol. 2001, 226, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, A. Manual of Cultivated Trees and Shrubs Hardy in North America, Exclusive of the Subtropical and Warmer Temperate Regions; Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T. Crabapples–When You’re Choosing One of Those Apple Cousins, Make Flowers Your Last Consideration. Am. Hortic. 1996, 75, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dirr, M.A. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses; Stipes Pub LLC: Champaign, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fiala, J.L. Flowering Crabapples: The Genus Malus; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, D. The Flowering Crabapples. Bull. Pop. Inf. (Arnold Arbor. Harv. Univ.) 1936, 4, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yao, Y.; Kang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Qin, L. Relationship Between Volatile Aroma Components and Amino Acid Metabolism in Crabapple (Malus spp.) Flowers, and Development of a Cultivar Classification Model. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Zhou, T.; Fan, J.; Zhang, W. Macrostructure of Malus Leaves and Its Taxonomic Significance. Plants 2025, 14, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A. Traditional Morphometrics in Plant Systematics and Its Role in Palm Systematics. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 151, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.; Ignatov, A.; Ponomarenko, V.; Dorokhov, D.; Savelyev, N. Phylogeny of the Malus (apple tree) Species, Inferred from the Morphological Traits and Molecular DNA Analysis. Russ. J. Genet. 2002, 38, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Huang, B.; Han, X.; Wu, K.; Xu, M.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; Xu, L.-A. Pedigree Reconstruction and Genetic Analysis of Major Ornamental Characters of Ornamental Crabapple (Malus spp.) Based on Paternity Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Fan, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, G.; Cao, F. A Binary-Based Matrix Model for Malus Corolla Symmetry and Its Variational Significance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.B.; Ren, C.; Kwak, M.; Hodel, R.G.; Xu, C.; He, J.; Zhou, W.B.; Huang, C.H.; Ma, H.; Qian, G.Z. Phylogenomic Conflict Analyses in the Apple Genus Malus sl Reveal Widespread Hybridization and Allopolyploidy Driving Diversification, with Insights into the Complex Biogeographic History in the Northern Hemisphere. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1020–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Trait No. | Trait Name | Descriptor/Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floral traits (23) | F1 | Inflorescence type | Corymb/umbel/solitary |

| F2 | Flower type | Single/semidouble/double | |

| F3 | Petal number | Count of petals per flower | |

| F4 | Petal shape | Ovate/obovate/elliptic | |

| F5 | Petal apex | Rounded/emarginate/acute | |

| F6 | Petal margin | Entire/wavy/irregular | |

| F7 | Petal base | Narrow/broad/clawed | |

| F8 | Flower size | Diameter (cm) | |

| F9 | Flower color (anthesis) | White/pink/red/purple | |

| F10 | Flower bud color | Greenish/pink/red/purple | |

| F11 | Color change during flowering | Stable/fading/intensifying | |

| F12 | Petal texture | Thin/leathery/papery | |

| F13 | Flower fragrance | Absent/weak/moderate/strong | |

| F14 | Sepal shape | Lanceolate/ovate/triangular | |

| F15 | Sepal reflexion at anthesis | Reflexed/upright | |

| F16 | Sepal margin | Entire/serrulate/hairy (eriocalyx) | |

| F17 | Stamen fertility | Fertile/partially sterile | |

| F18 | Anther color | Yellow/red/purple | |

| F19 | Stamen number | Few (<10)/Medium (10–20)/Many (>20) | |

| F20 | Pistil position | Superior/inferior/semi-inferior | |

| F21 | Pistil number | Single/multiple | |

| F22 | Pistil length relative to stamens | Shorter/equal/longer | |

| F23 | Blooming period | Early/mid/late season | |

| Leaf traits (12) | L1 | Young leaf color | Green/reddish/purple |

| L2 | Mature leaf shape | Ovate/elliptic/lanceolate | |

| L3 | Leaf apex | Acute/acuminate/rounded | |

| L4 | Leaf base | Cuneate/rounded/cordate | |

| L5 | Leaf margin | Entire/serrated/doubly serrated | |

| L6 | Leaf size | Length × width (cm) | |

| L7 | Leaf thickness | Thin/medium/thick | |

| L8 | Leaf texture | Leathery/papery | |

| L9 | Leaf venation | Pinnate/curved/arcuate | |

| L10 | Leaf pubescence | Absent/sparse/dense | |

| L11 | Petiole length | Length in cm | |

| L12 | Petiole pubescence | Absent/sparse/dense | |

| Fruit traits (12) | FR1 | Fruit shape | Round/oblate/conical/elliptic |

| FR2 | Fruit size | Diameter (cm) | |

| FR3 | Fruit weight | g/fruit | |

| FR4 | Fruit color (mature) | Yellow/green/red/purple | |

| FR5 | Fruit surface gloss | Glossy/dull | |

| FR6 | Fruit skin thickness | Thin/thick | |

| FR7 | Fruit pedicel length | cm | |

| FR8 | Fruit pedicel orientation | Upright/drooping/spreading | |

| FR9 | Calyx persistence | Persistent/deciduous | |

| FR10 | Seed number per fruit | Count | |

| FR11 | Fruit maturation period | Early/mid/late | |

| FR12 | Fruit persistence on tree | Short/medium/long | |

| Tree and bark traits (8) | T1 | Plant habit | Tree/shrub |

| T2 | Tree height | m | |

| T3 | Crown shape | Upright/spreading/weeping/columnar | |

| T4 | Branch density | Sparse/medium/dense | |

| T5 | Branch posture | Upright/horizontal/pendulous | |

| T6 | Presence of spines | Present/absent | |

| T7 | Bark color | Gray/brown/reddish | |

| T8 | Bark texture | Smooth/fissured/peeling |

| Group | Subgroup | No. of Cultivars | Representative Cultivars | Key Diagnostic Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Single Flower Group (71) | Single-white (31) | 31 | M. ‘White Cascade’, M. ‘Marry Potter’, M. ‘Weeping Madonna’, M.‘Lancelot’, M. ‘Spring Snow’, M.‘Dolgo’, M.‘Fairytail Gold’, M. ‘Red Sentinel’, M. ‘King Arthur’, M. ‘Donald Wyman’, M. ‘Adirondack’, M. ‘Molten Lava’, ‘Sugar Tyme’, M. ‘Everest’, M. ‘Red Great’, M. ‘Spring Sensation’, M. ‘Guard’, M.‘Havest Gold’, M.‘Gorgeous’, M. ‘Winter Red’, M.‘Lollipop’, M.‘Firebird’, M. ‘David’, M. ‘Professor Sprenger’, M. ‘Cinderella’, M.×zumi ‘Calocarpa’, M. ‘Golden Raindrop’, M. ‘Hydrangea’, M. ‘Snow Drift’, M. ‘Sweet SugarTyme’, M.‘Almey’ | 5 petals, white corolla, simple ovate petals, weak fragrance |

| Single-red (40) | 40 | M. ‘Prairifire’, M. ‘Indian Magic’, M. ‘Velvet Pillar’, M. ‘Royal Beauty’, M. ‘Radiant’, M.‘ Profusion’, M. ‘Liset’, M. ‘Royal Raindrop’, M. × purpurea ‘Lemoinei’, M. ‘Purple Prince’,z M. ‘Red Splendor’, M. ‘Abundance’, M. ‘John Downie’, M. ‘Lisa’, M. ‘Rudolph’, M. ‘Red Baron’, M. ‘Thunderchild’, M. ‘Centurion’, M. ‘Eleyi’, M. ‘Louisa Contort’, M. ‘Show Time’, M. ‘Makamik’, M. ‘Cardinal’, M. × purpurea ‘Neville Copeman’, M. ‘Coralburst’, M. ‘Robinson’, M. ‘May’s Delight’, M. ‘Strawberry Jelly’, M. ‘Spring Sensation’, M. ‘Candymint’, M. ‘Pink Princess’, M. ‘Hopa’, M. ‘Royal Gem’, M.‘Butterball’, M.‘Regal’, M.‘Pink Spire’, M.‘Golden Hornet’, M.‘Flame’, M. ‘Red Jade’, M. Sylvestris, M.‘Indian Summer’ | 5 petals, pink/red/purple corolla, medium fragrance, variable sepal reflexion | |

| II. Semidouble Flower Group (2) | — | 2 | M. ‘Royalty’, M. ‘Coralcole’ | 6–10 petals, pink corolla, partial stamen sterility |

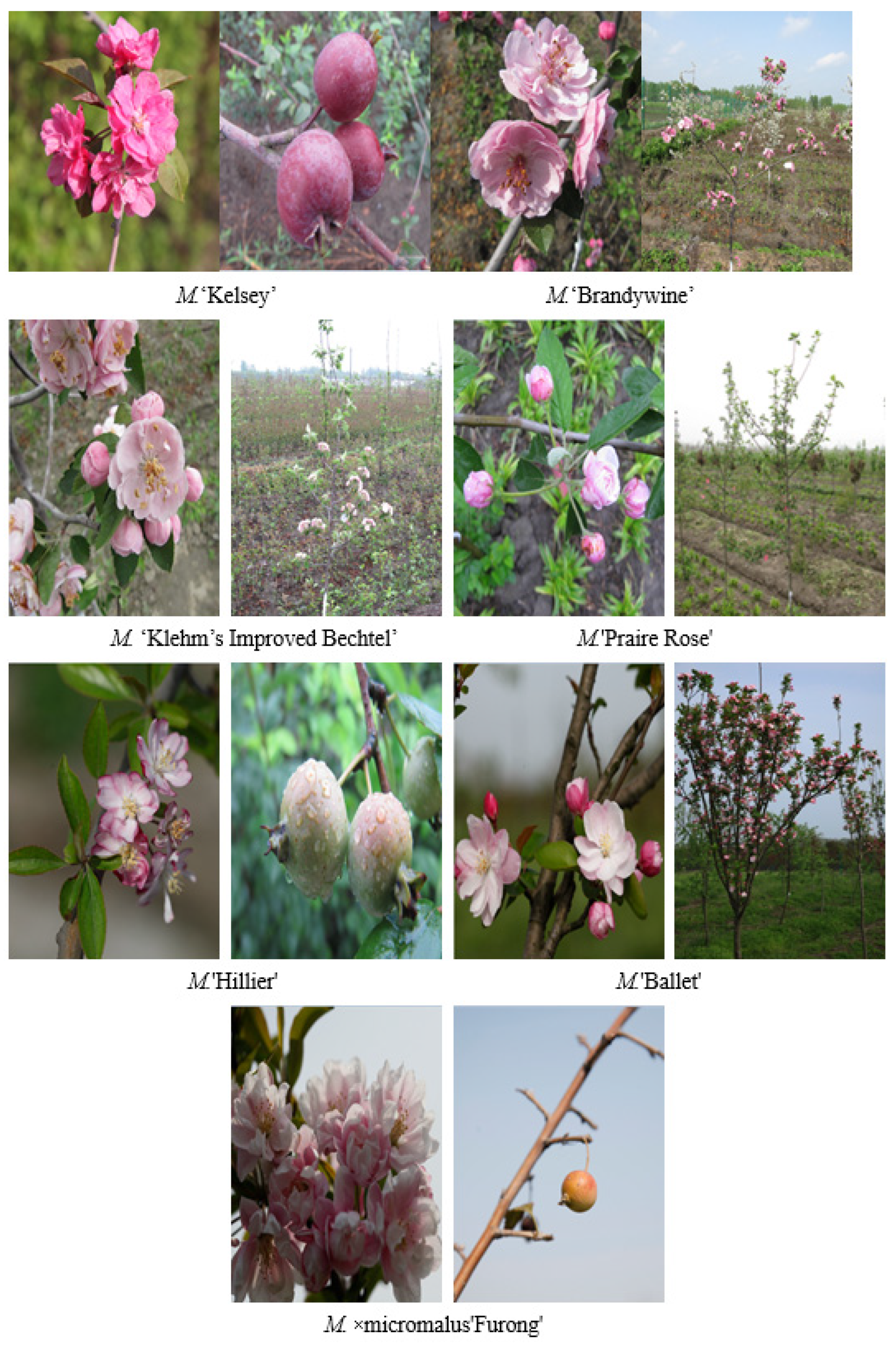

| III. Double Flower Group (7) | — | 7 | M. ‘Ballet’, M. ‘Brandywine’, M. ‘Kelsey’, M. ‘Klehm’s Improved Bechtel’, M. ‘Praire Rose’, M. ‘Hillier’, M. ×micromalus ‘Furong’ | >10 petals, double corolla, strong ornamental effect, reduced fertility |

| Group/Subgroup | Petal Number | Flower Color | Fragrance | Stamen Fertility | Sepal Reflexion | Fruit and Leaf Traits (Auxiliary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Single Flower Group | ||||||

| –Single-white (31) | 5 | White (pure to creamy) | Weak or absent | Fertile | Mostly reflexed | Fruits small (1–2 cm), leaves ovate with serrated margin |

| –Single-red (40) | 5 | Pink to deep red/purple | Weak to moderate | Fertile | Reflexed or upright | Fruits variable (1–3 cm), leaves often reddish when young |

| II. Semidouble Flower Group (2) | 6–10 | Light pink | Moderate | Partially sterile | Mostly upright | Fruits medium (2–3 cm), crown spreading |

| III. Double Flower Group (7) | >10 (often 12–20) | Pink, red, or purple | Moderate to strong | Sterile or nearly sterile | Mostly upright | Fruits rare or absent, leaves broad ovate |

| Region/System | Main Classification Basis | Limitations | This Study’s Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Emphasis on phylogenetic background and morphological traits (flower type, fruit traits, sepal persistence). | Nomenclatural inconsistencies; over-reliance on variable traits (leaf size, fruit yield). | Broader trait dataset (55 traits) combined with numerical taxonomy; reduced synonymy. |

| Europe | Descriptive manuals; focus on ornamental traits such as flower color, fruit size, and landscape value. | Lacks hierarchical framework; descriptive but subjective; cultivars often inconsistently classified. | Established a reproducible hierarchical system with clear diagnostic characters (flower type + color). |

| North America | Horticultural orientation; classification often tied to disease resistance, growth habit, and landscape adaptability. | Practical but weak in taxonomy; cultivars grouped by utility rather than morphology. | Provides a taxonomy-oriented but still horticulturally practical framework. |

| Japan | Emphasis on aesthetic features (floral density, cultural symbolism) in classification. | Cultural-horticultural approach; limited systematic studies; descriptors not standardized. | Offers standardized descriptors aligned with ICNCP, enabling cross-cultural comparison. |

| This Study | Morphological classification (flower type and color as primary criteria) validated by numerical taxonomy (R-type and Q-type clustering). | — | Provides an integrative, reproducible, and internationally comparable framework; reference model for global harmonization. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, M.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Ji, X. Classification Framework of Introduced Crabapple (Malus spp.) Cultivars Based on Morphological and Numerical Traits: Insights for Germplasm Conservation and Landscape Forestry. Forests 2025, 16, 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121792

He M, Zheng Y, Hu Y, Zhao P, Ji X. Classification Framework of Introduced Crabapple (Malus spp.) Cultivars Based on Morphological and Numerical Traits: Insights for Germplasm Conservation and Landscape Forestry. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121792

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Mei, Yutao Zheng, Yuan Hu, Pan Zhao, and Xiaofan Ji. 2025. "Classification Framework of Introduced Crabapple (Malus spp.) Cultivars Based on Morphological and Numerical Traits: Insights for Germplasm Conservation and Landscape Forestry" Forests 16, no. 12: 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121792

APA StyleHe, M., Zheng, Y., Hu, Y., Zhao, P., & Ji, X. (2025). Classification Framework of Introduced Crabapple (Malus spp.) Cultivars Based on Morphological and Numerical Traits: Insights for Germplasm Conservation and Landscape Forestry. Forests, 16(12), 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121792