Core-Shell Structured Electro- and Magneto-Responsive Materials: Fabrication and Characteristics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Fabrication and Field Response

2.1. Electrostatic Attraction

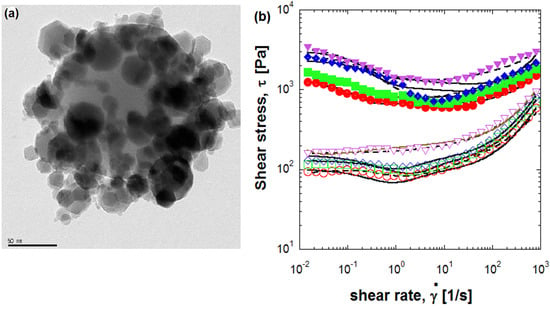

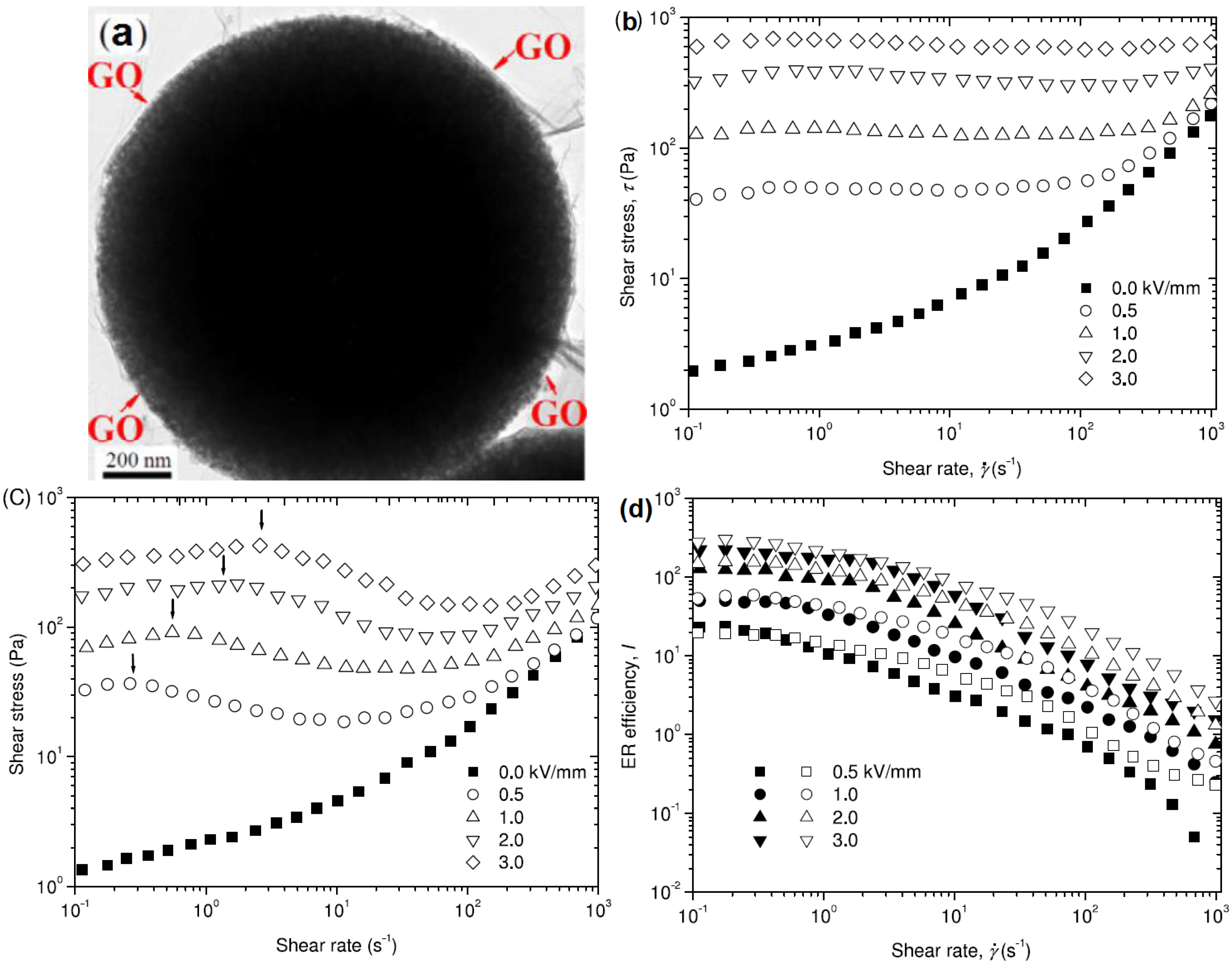

2.2. Self-Assembly Method

2.3. Solvent Casting Method

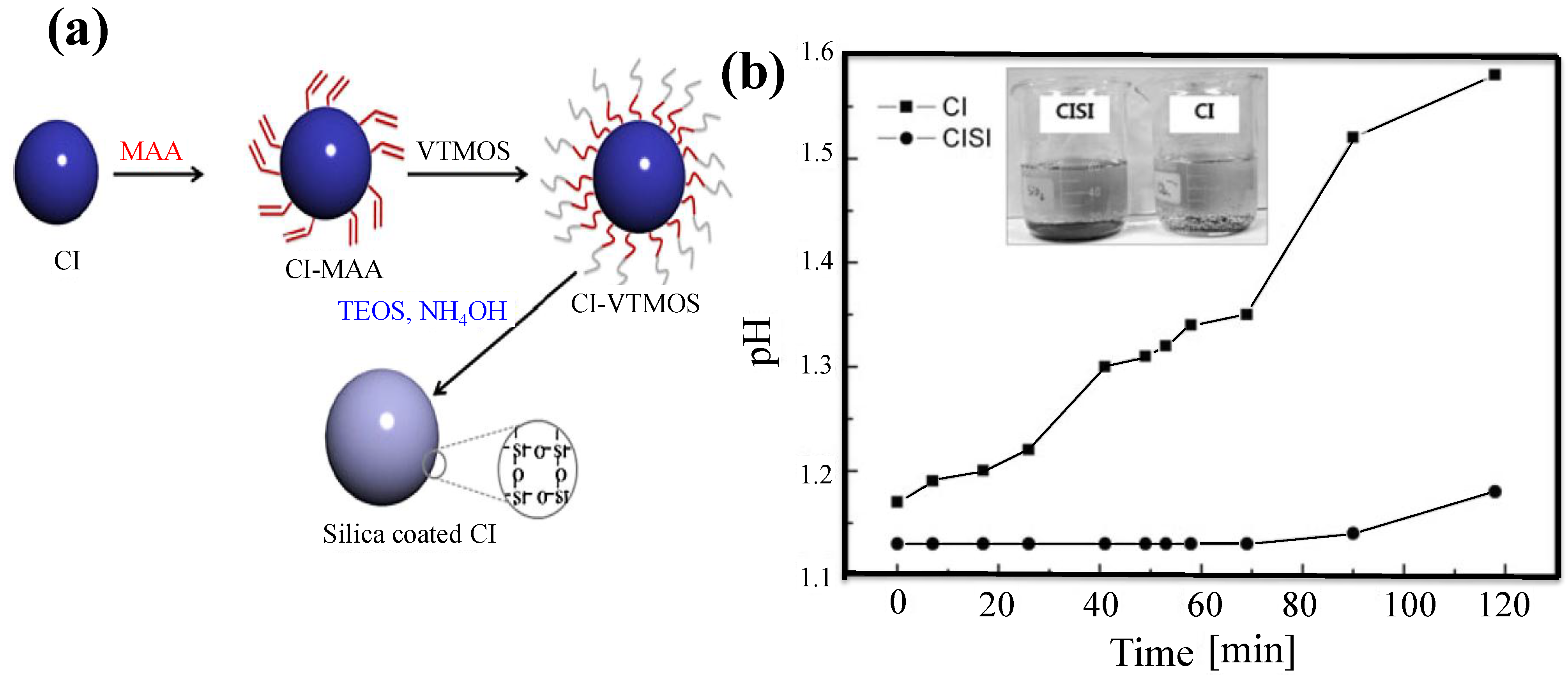

2.4. Sol-Gel Method

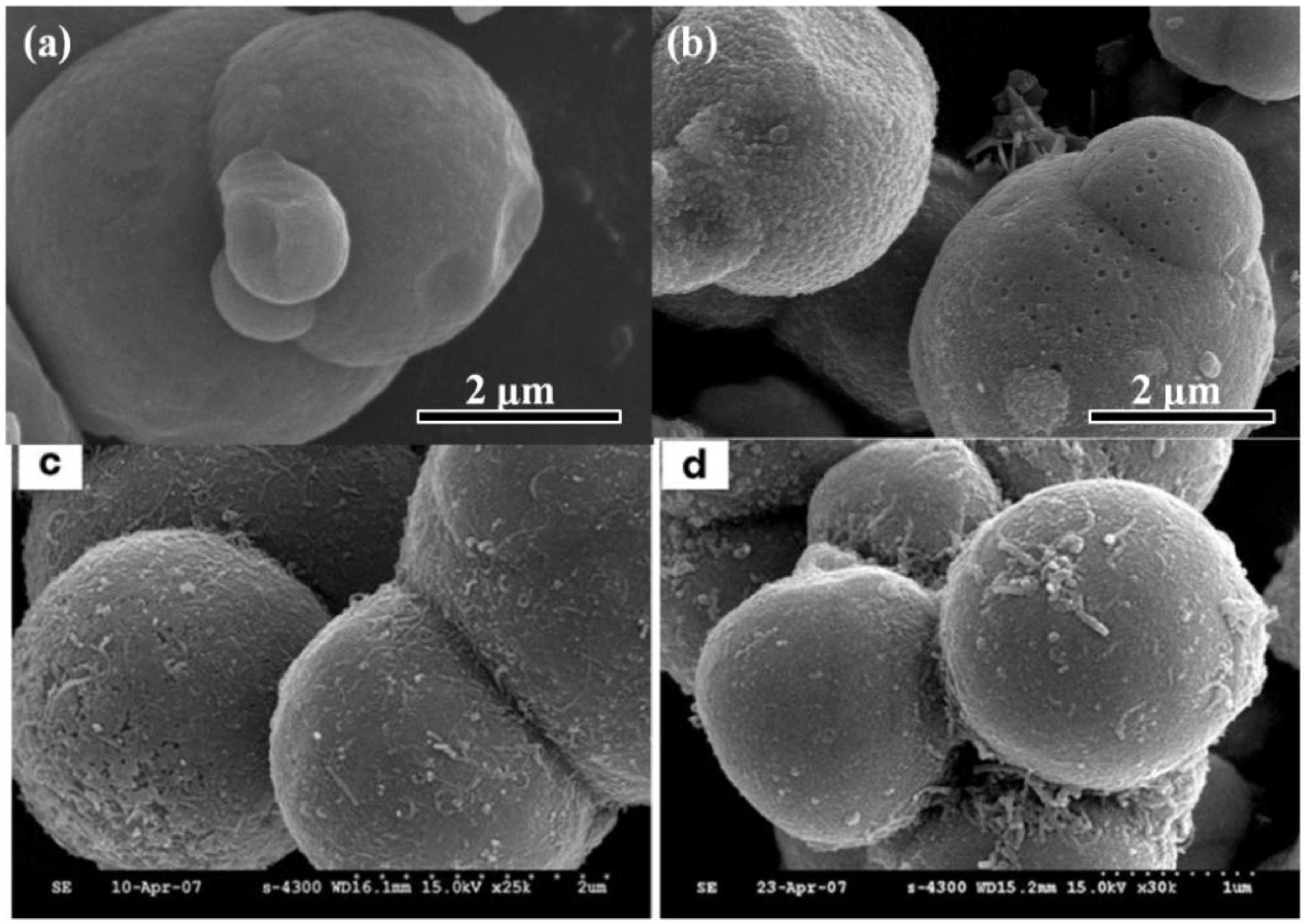

2.5. Eco-Friendly Pickering Emulsion Polymerization

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhuri, R.G.; Paria, S. Core/shell nanoparticles: Classes, properties, synthesis mechanisms, characterization, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2373–2433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Yi, L.X.; Zhao, N.; Tang, A.W.; Gao, M.Y.; Tang, Z.Y. Synthesis and shape-tailoring of copper sulfide/indium sulfide-based nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13152–13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballauff, M.; Lu, Y. “Smart” nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization and applications. Polymer 2007, 48, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.; Ow, H.; Wiesner, U. Fluorescent core-shell silica nanoparticles: Towards “Lab on a Particle” architectures for nanobiotechnology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 1028–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgueirino-Maceira, V.; Correa-Duarte, M.A. Increasing the complexity of magnetic core/shell structured nanocomposites for biological applications. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 4131–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Vivekchand, S.R.C.; Biswas, K.; Govindaraj, A. Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials. Dalton Trans. 2007, 34, 3728–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Ning, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. One-step synthesis of porous graphene-based hydrogels containing oil droplets for drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Zhao, X.P. Core/shell nanocomposite based on the local polarization and its electrorheological behavior. Langmuir 2005, 21, 6553–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.B.; Wen, W.J.; Sheng, P. Smart electroresponsive droplets in microfluidics. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 11589–11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vicente, J.; Klingenberg, D.J.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, R. Magnetorheological fluids: A review. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 3701–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Jhon, M.S. Electrorheology of polymers and nanocomposites. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.M.; Choi, S.B. Control of an ER haptic master in a virtual slave environment for minimally invasive surgery applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 065012:1–065012:10. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J. Magnetorheology: Materials and application. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 5246–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, D.J. Magnetorheology: Applications and challenges. AlChE J. 2001, 47, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.G.; Zhu, W.Q. A stochastic optimal semi-active control strategy for ER/MR dampers. J. Sound Vib. 2003, 259, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.Y.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Jang, J. Graphene size control via a mechanochemical method and electroresponsive properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 5531–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.L.; Park, B.J.; Choi, H.J. Colloidal graphene oxide/polyaniline nanocomposite and its electrorheology. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5596–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.Y.; Jang, J. Highly stable, concentrated dispersions of graphene oxide sheets and their electro-responsive characteristics. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 7348–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.B.; Wang, X.X.; Chang, R.T.; Zhao, X.P. Polyaniline decorated graphene sheet suspension with enhanced electrorheology. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, B.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Yunus, W.; Hussein, M.Z. Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(ethylene glycol) polymer nanocomposites: Effects of graphene nanoplatelets. Polymers 2014, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.Y.; Kang, T.J. Electrorheological response of inorganic-coated multi-wall carbon nanotubes with core-shell nanostructure. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 3726–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.D.; Choi, H.J. Electrorheological fluids: Smart soft matter and characteristics. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 11961–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.L.; Liu, Y.D.; Choi, H.J. Graphene oxide coated core-shell structured polystyrene microspheres and their electrorheological characteristics under applied electric field. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 6916–6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.D.; Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J. Core-Shell structured semiconducting PMMA/polyaniline snowman-like anisotropic microparticles and their electrorheology. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12849–12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Shui, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, X. Enhanced dielectric polarization and electro-responsive characteristic of graphene oxide-wrapped titania microspheres. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 045702:1–045702:11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.T.; Cho, M.S.; Jang, I.B.; Choi, H.J.; Jhon, M.S. Magnetorheology of carbonyl-iron suspensions with submicron-sized filler. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2004, 40, 3033–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machovsky, M.; Mrlik, M.; Kuritka, I.; Pavlinek, V.; Babayan, V. Novel synthesis of core-shell urchin-like ZnO coated carbonyl iron microparticles and their magnetorheological activity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacik, M.; Pavlinek, V.; Saha, P.; Svrcinova, P.; Filip, P.; Stejskal, J. Rheological properties of magnetorheological suspensions based on core-shell structured polyaniline-coated carbonyl iron particles. Smart Mater. Struct. 2010, 19, 115008:1–115008:6. [Google Scholar]

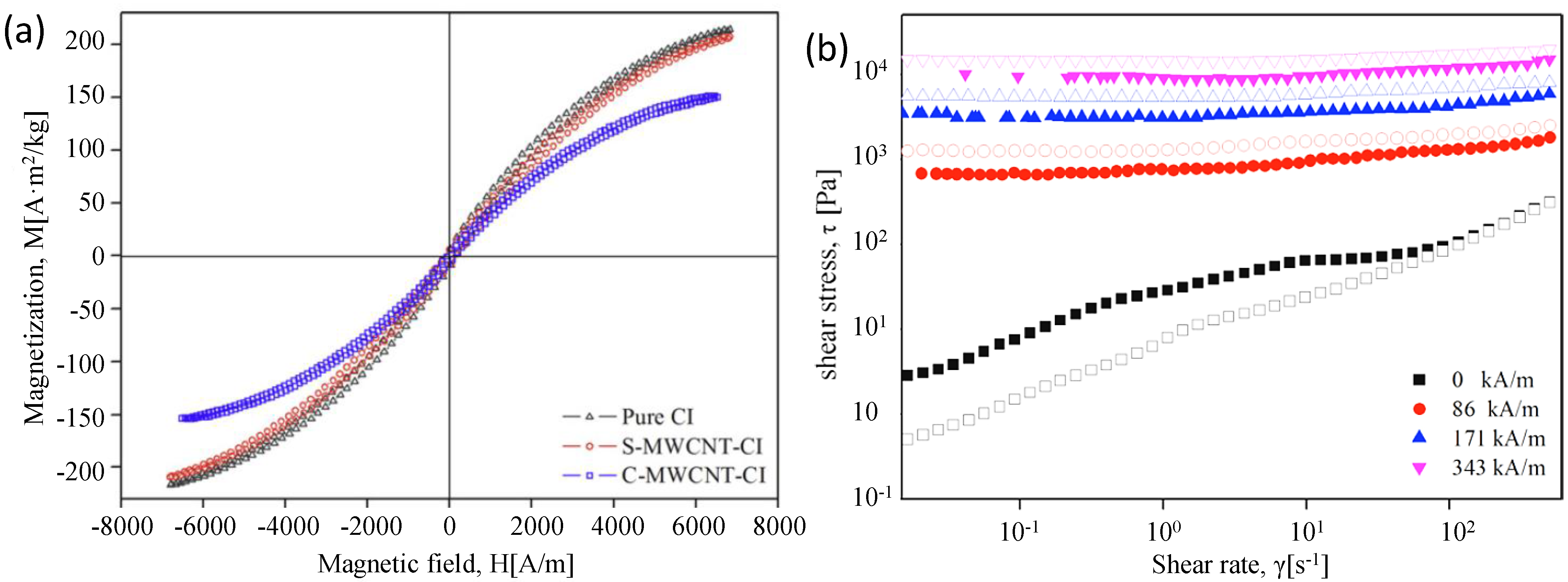

- Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J.; Seo, Y. Sequential coating of magnetic carbonyliron particles with polystyrene and multiwalled carbon nanotubes and its effect on their magnetorheology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J. Noncovalent self-assembly of carbon nanotube wrapped carbonyl iron particles and their magnetorheology. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A301:1–07A301:3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.L.; Choi, H.J. Self-assembly of graphene oxide coated soft magnetic carbonyl iron particles and their magnetorheology. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 17B508:1–17B508:3. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.D.; Choi, H.J.; Choi, S.B. Controllable fabrication of silica encapsulated soft magnetic microspheres with enhanced oxidation-resistance and their rheology under magnetic field. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2012, 403, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.D.; Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J. Core-shell-structured silica-coated magnetic carbonyl iron microbead and its magnetorheology with anti-acidic characteristics. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2011, 289, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, M.; Kamino, A.; Okamura, J.; Shinkai, S. Noncovalent self-assembly of carbon nanotubes for construction of “cages”. Nano Lett. 2002, 2, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; He, M.; Xu, X.J.; Zhang, L.N.; Yu, J.P. Self-assembly of graphene oxide on the surface of aluminum foil. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.F.; Choi, H.J. Fabrication of multiwalled carbon nanotube-wrapped magnetic carbonyl iron microspheres and their magnetorheology. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.F.; Liu, Y.D.; Choi, H.J. Carbon nanotube coated magnetic carbonyl iron microspheres prepared by solvent casting method and their magneto-responsive characteristics. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2012, 412, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.T.; Jiang, F.J. Towards high sedimentation stability: Magnetorheological fluids based on CNT/Fe3O4 nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

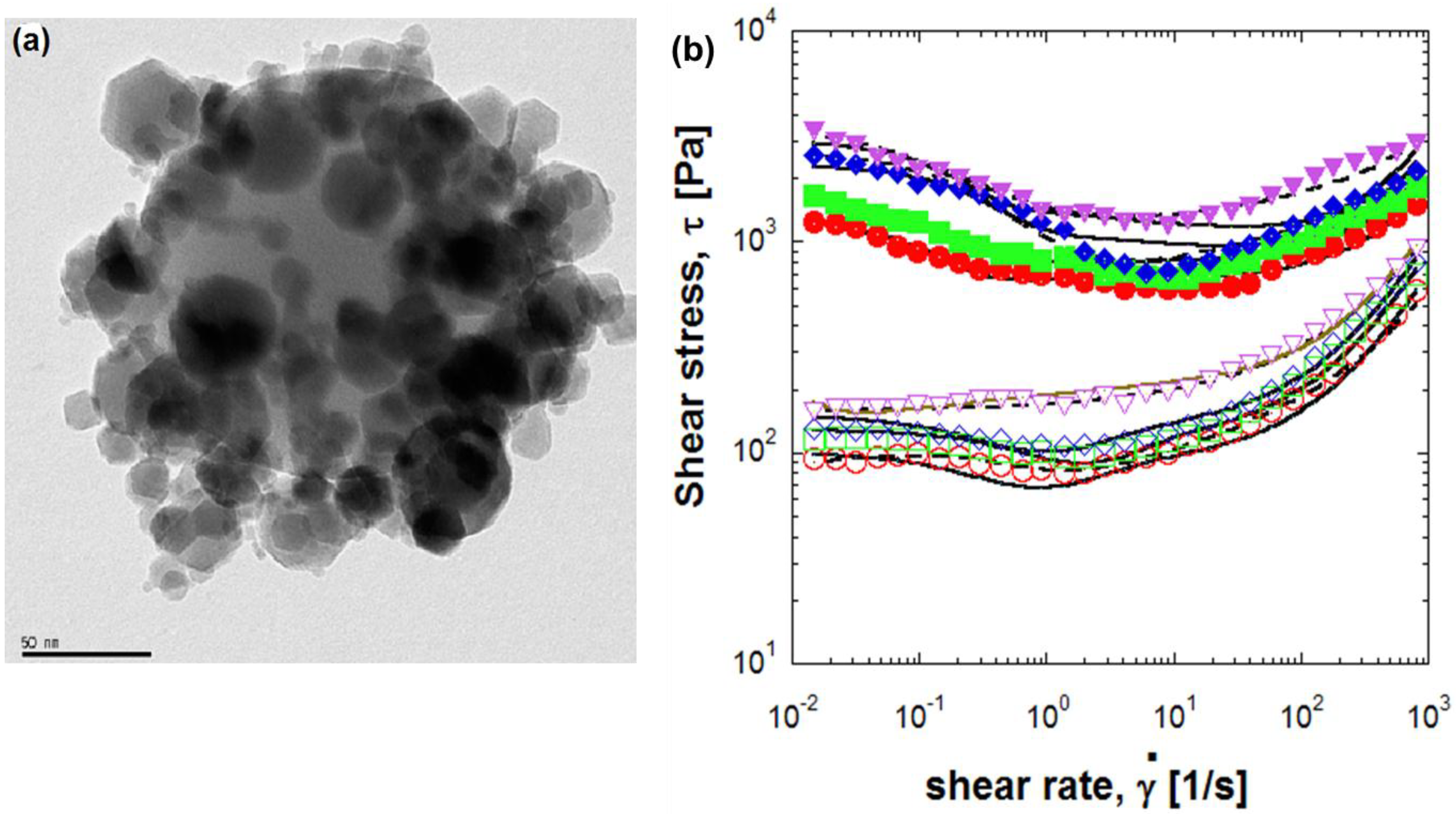

- Kim, Y.J.; Liu, Y.D.; Seo, Y.; Choi, H.J. Pickering-emulsion-polymerized polystyrene/Fe2O3 composite particles and their magnetoresponsive characteristics. Langmuir 2013, 29, 4959–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, C.; Yang, H.; Green, P.F. Electrorheology of suspensions containing interfacially active constituents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 8925–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, C.; Yang, H.; Green, P.F. Electrorheology of polystyrene filler/polyhedral silsesquioxane suspensions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2148–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glotzer, S.C.; Solomon, M.J.; Kotov, N.A. Self-assembly: From nanoscale to microscale colloids. AlChE J. 2004, 50, 2978–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Jiang, R.; Xiao, L.; Li, W. A novel magnetically separable gamma-Fe2O3/crosslinked chitosan adsorbent: Preparation, characterization and adsorption application for removal of hazardous azo dye. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, W.; Shen, X.; Diao, G.W. Fabrication of core-shell alpha-Fe2O3/Li4Ti5O12 composite and its application in the lithium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 4514–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.S.; Hu, J.S.; Liang, H.P.; Cao, A.M.; Song, W.G.; Wan, L.J. Self-assembled 3D flowerlike iron oxide nanostructures and their application in water treatment. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.F.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, H.J. Synthesis of core-shell structured PS/Fe3O4 microbeads and their magnetorheology. Polymer 2009, 50, 2290–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, B.D.; Park, J.H.; Kwon, M.H.; Park, O.O. Rheological properties and dispersion stability of magnetorheological (MR) suspensions. Rheol. Acta 2001, 40, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.S.; Choi, H.J.; Jhon, M.S. Shear stress analysis of a semiconducting polymer based electrorheological fluid system. Polymer 2005, 46, 11484–11488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, K.P.S.; Meheust, Y.; Schjelderupsen, B.; Fossum, J.O. Electrorheological suspensions of laponite in oil: Rheometry studies. Langmuir 2008, 24, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.P.; Seo, Y. Modeling and analysis of electrorheological suspensions in shear flow. Langmuir 2012, 28, 3077–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.P.; Choi, H.J.; Seo, Y. Analysis of the flow behavior of electrorheological fluids with the aligned structure reformation. Polymer 2011, 52, 5695–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.P.; Choi, H.J.; Seo, Y. A simplified model for analyzing the flow behavior of electrorheological fluids containing silica nanoparticle-decorated polyaniline nanofibers. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 4659–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.P.; Choi, H.J.; Seo, Y. Modeling and analysis of an electrorheological flow behavior containing semiconducting graphene oxide/polyaniline composite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 457, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H.J.; Zhang, W.L.; Kim, S.; Seo, Y. Core-Shell Structured Electro- and Magneto-Responsive Materials: Fabrication and Characteristics. Materials 2014, 7, 7460-7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7117460

Choi HJ, Zhang WL, Kim S, Seo Y. Core-Shell Structured Electro- and Magneto-Responsive Materials: Fabrication and Characteristics. Materials. 2014; 7(11):7460-7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7117460

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyoung Jin, Wen Ling Zhang, Sehyun Kim, and Yongsok Seo. 2014. "Core-Shell Structured Electro- and Magneto-Responsive Materials: Fabrication and Characteristics" Materials 7, no. 11: 7460-7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7117460

APA StyleChoi, H. J., Zhang, W. L., Kim, S., & Seo, Y. (2014). Core-Shell Structured Electro- and Magneto-Responsive Materials: Fabrication and Characteristics. Materials, 7(11), 7460-7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7117460