Closed Loop of Polyurethanes: Effect of Isocyanate Index on the Properties of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols Obtained by Glycolysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Manufacturing of Rigid PUR Foams for Chemical Recycling

2.2. Chemolysis of PUR Foams and Biofoams

2.3. Manufacturing of Rigid PUR Foams Based of Repolyol and Rebiopolyol

2.4. Characterization of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols

2.5. Characterization of Polyurethane Foams and Biofoams

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wieczorek, K.; Bukowski, P.; Stawiński, K.; Ryłko, I. Recycling of Polyurethane Foams via Glycolysis: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Hyldmo, H.; Rye, S.A.; Vela-Almeida, D. A globally just and inclusive transition? Questioning policy representations of the European Green Deal. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 89, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Teitge, J.; Mielke, J.; Schütze, F.; Jaeger, C. The European Green Deal—More Than Climate Neutrality. Intereconomics 2021, 56, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowicz, M.; Isbrandt, M. Effect of New Eco-Polyols Based on PLA Waste on the Basic Properties of Rigid Polyurethane and Polyurethane/Polyisocyanurate Foams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Westman, Z.; Richardson, K.; Lim, D.; Stottlemyer, A.L.; Farmer, T.; Gillis, P.; Vlcek, V.; Christopher, P.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Opportunities in Closed-Loop Molecular Recycling of End-of-Life Polyurethane. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 6114–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, R.; Boaretti, C.; Lorenzetti, A.; Roso, M.; Penzo, D.; Dal Lago, E.; Modesti, M. Chemical Recycling of Polyurethane Waste via a Microwave-Assisted Glycolysis Process. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 4655–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Członka, S.; Kairytė, A.; Miedzińska, K.; Strąkowska, A. Polyurethane composites reinforced with walnut shell filler treated with perlite, montmorillonite and halloysite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kura, M. Biopolyolysis—A new biopathway for recycling waste polyurethane foams. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutrzenka Trzebiatowska, P.; Beneš, H.; Datta, J. Evaluation of the glycerolysis process and valorisation of recovered polyol in polyurethane synthesis. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 139, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Luo, H.; Lv, S.; Chen, P. Glycolysis recycling of waste polyurethane rigid foam using different catalysts. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiran, R.; Ghaderian, A.; Reghunadhan, A.; Sedaghati, F.; Thomas, S.; Haghighi, A.H. Glycolysis: An efficient route for recycling of end of life polyurethane foams. J. Polym. Res. 2021, 28, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurańska, M.; Benes, H.; Kockova, O.; Kucała, M.; Malewska, E.; Schmidt, B.; Michałowski, S.; Zemła, M.; Prociak, A. Rebiopolyols—New components for the synthesis of polyurethane biofoams in line with the circular economy concept. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Li, J.K. Glycolysis of rigid polyurethane from waste refrigerators. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 75, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Fernández, R.; Amundarain, I.; Asueta, A.; García-Fernández, S.; Arnaiz, S.; Miazza, N.L.; Montón, E.; Rodríguez-García, B.; Bianca-Benchea, E. Recovery of Green Polyols from Rigid Polyurethane Waste by Catalytic Depolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, J. Effect of glycols used as glycolysis agents on chemical structure and thermal stability of the produced glycolysates. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 109, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutrzenka Trzebiatowska, P.; Dzierbicka, A.; Kamińska, N.; Datta, J. The influence of different glycerine purities on chemical recycling process of polyurethane waste and resulting semi-products. Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepkowski, L.; Ryszkowska, J.; Auguścik, M.; Przekurat, S. Viscoelastic polyurethane foams suitable for multiple washing processes. Polimery 2018, 63, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, M.; Costantini, F.; dal Lago, E.; Piovesan, F.; Roso, M.; Boaretti, C.; Lorenzetti, A. Valuable secondary raw material by chemical recycling of polyisocyanurate foams. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 156, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-93/C-89052/03; Polietery Do Poliuretanów–Metody Badań–Oznaczanie Liczby Hydroksylowej. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Polska, 1993.

- BN-69/6110-29; Oznaczanie Liczby Aminowej w Żywicach Poliamidowych i Trójetylenoczteroaminie. Zjednoczenie Przemysłu Farb i Lakierów: Warszawa, Polska, 1969.

- PN-81/C-04959; Oznaczanie Zawartości Wody Metodą Karla Fischera w Produktach Organicznych i Nieorganicznych. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Polska, 1981.

- ASTM D7487-18; Standard Practice for Polyurethane Raw Materials: Polyurethane Foam Cup Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- EN 14315-1:2013; Thermal Insulating Products for Buildings—In-Situ Sprayed Rigid Polyurethane (PUR) and Polyisocyanurate (PIR) Foam Products—Part 1: Specification for the Spray Applied System Before Application. CEN: Brussels, Polska; Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Polska, 2013.

- ISO 845:2006; Cellular Plastics and Rubbers—Determination of Apparent Density. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 4590:2016; Rigid Cellular Plastics—Determination of the Volume Percentage of Open Cells and of Closed Cells. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 844:2021; Rigid Cellular Plastics—Determination of Compression Properties. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Jin, X.; Guo, N.; You, Z.; Tan, Y. Design and performance of polyurethane elastomers composed with different soft segments. Materials 2020, 13, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuranska, M.; Malewska, E.; Polaczek, K.; Prociak, A.; Kubacka, J. A Pathway toward a New Era of Open-Cell Polyurethane Foams—Influence of Bio-Polyols Derived from Used Cooking Oil on Foams Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Ref1.1 | Ref0.9 | Ref0.7 | Ref0.5 | Bio1.1 | Bio0.9 | Bio0.7 | Bio0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF-551, g | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biopolyol, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Polycat 9, g | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| L6988, g | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Water, g | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Index NCO | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Component | rRef1.1/PU | rRef0.9/PU | rRef0.7/PU | rRef0.5/PU | rBio1.1/PU | rBio0.9/PU | rBio0.7/PU | rBio0.5/PU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rRef1.1, g | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rRef0.9, g | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rRef0.7, g | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rRef0.5, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rBio1.1, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rBio0.9, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| r.Bio0.7, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| rBio0.5, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Polycat 9, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L6988, g | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Water, g | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Index NCO | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

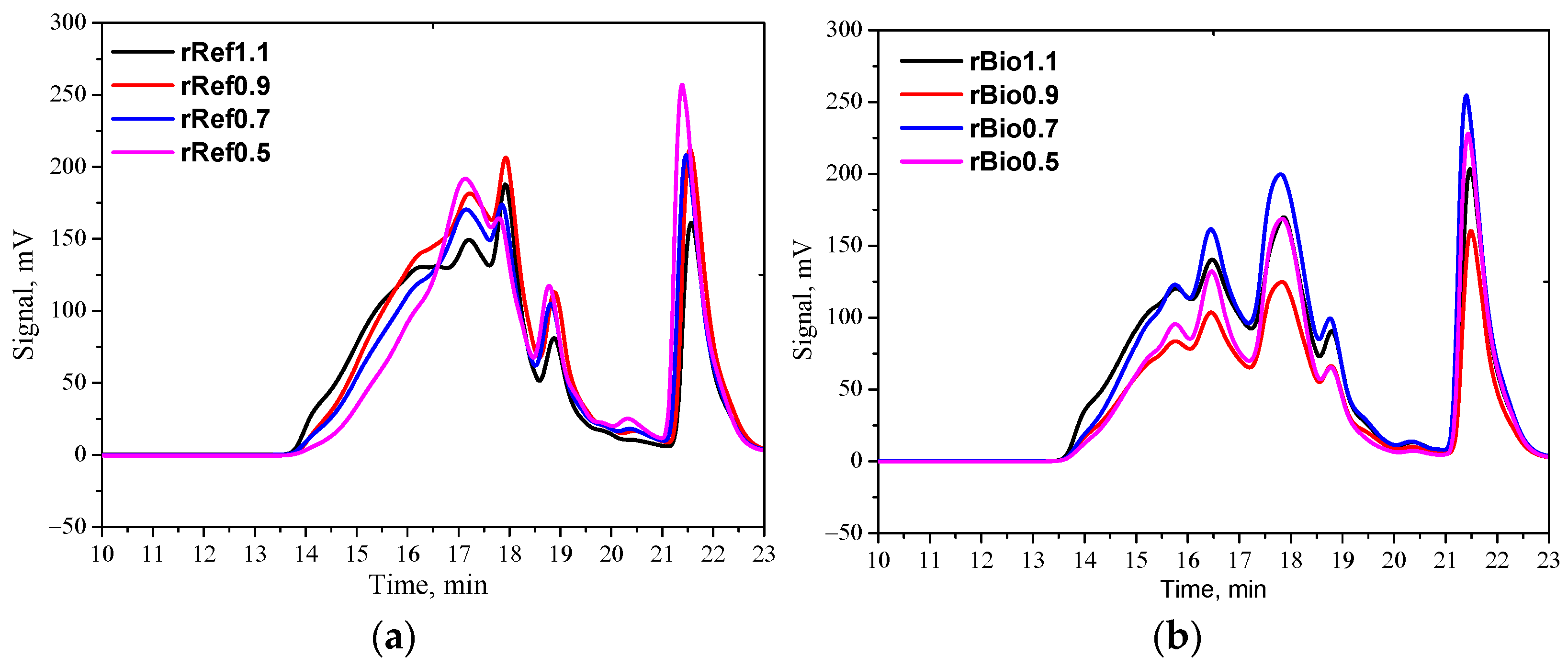

| Symbol | Mn, g/mol | Mw, g/mol | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| rRef1.1 | 393 | 707 | 1.80 |

| rRef0.9 | 358 | 634 | 1.77 |

| rRef0.7 | 352 | 624 | 1.78 |

| rRef0.5 | 318 | 556 | 1.75 |

| rBio1.1 | 372 | 716 | 1.92 |

| rBio0.9 | 352 | 676 | 1.92 |

| rBio0.7 | 346 | 653 | 1.89 |

| rBio0.5 | 332 | 638 | 1.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurańska, M.; Malewska, E.; Sędzimir, J.; Ożóg, H.; Put, A.; Kowalik, N.; Kucała, M. Closed Loop of Polyurethanes: Effect of Isocyanate Index on the Properties of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols Obtained by Glycolysis. Materials 2025, 18, 5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245503

Kurańska M, Malewska E, Sędzimir J, Ożóg H, Put A, Kowalik N, Kucała M. Closed Loop of Polyurethanes: Effect of Isocyanate Index on the Properties of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols Obtained by Glycolysis. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245503

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurańska, Maria, Elżbieta Malewska, Julia Sędzimir, Hubert Ożóg, Aleksandra Put, Natalia Kowalik, and Michał Kucała. 2025. "Closed Loop of Polyurethanes: Effect of Isocyanate Index on the Properties of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols Obtained by Glycolysis" Materials 18, no. 24: 5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245503

APA StyleKurańska, M., Malewska, E., Sędzimir, J., Ożóg, H., Put, A., Kowalik, N., & Kucała, M. (2025). Closed Loop of Polyurethanes: Effect of Isocyanate Index on the Properties of Repolyols and Rebiopolyols Obtained by Glycolysis. Materials, 18(24), 5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245503