Integrating the Porosity/Binder Index and Machine Learning Approaches for Simulating the Strength and Stiffness of Cemented Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objective and Scope

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

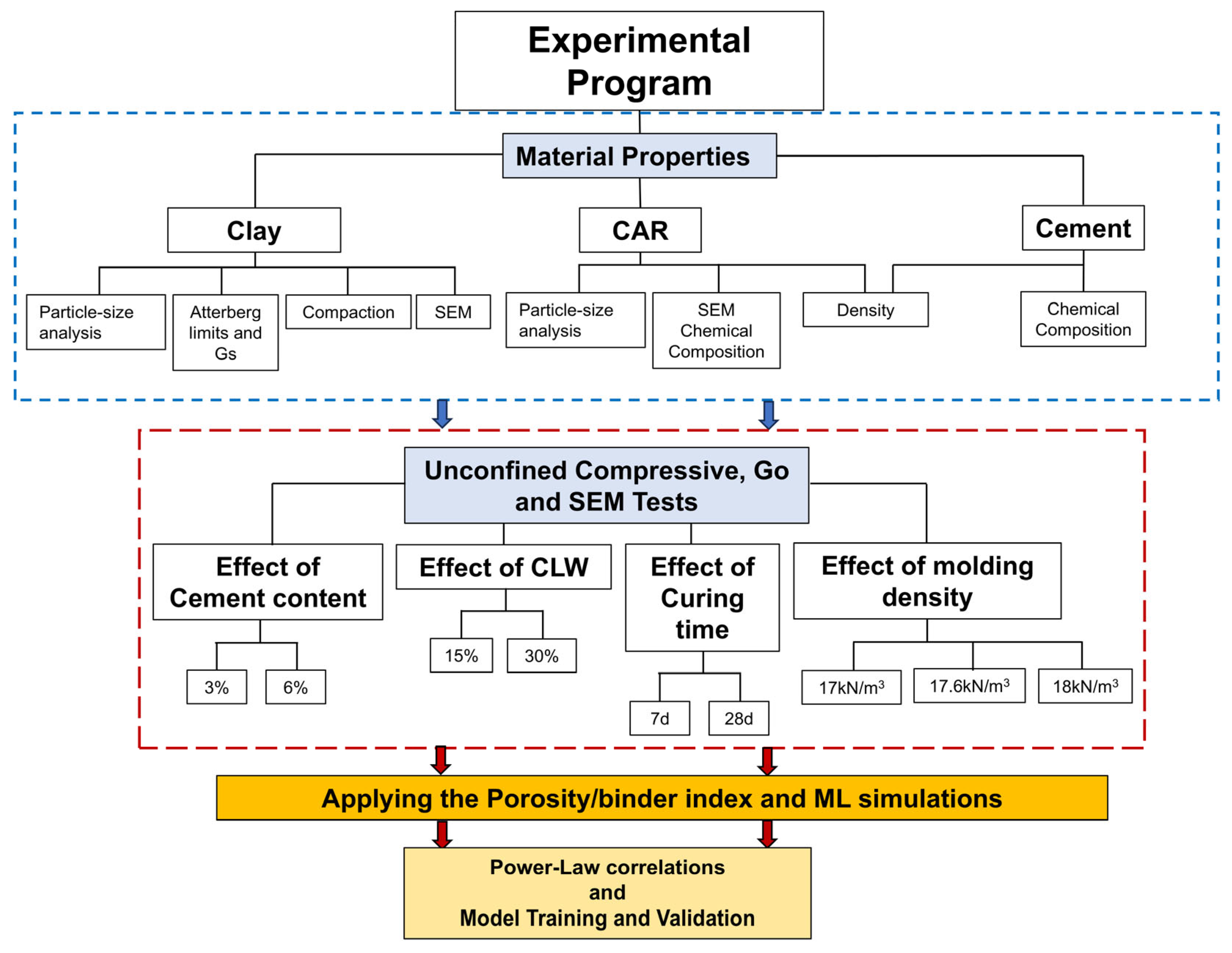

2.2. Experimental Program

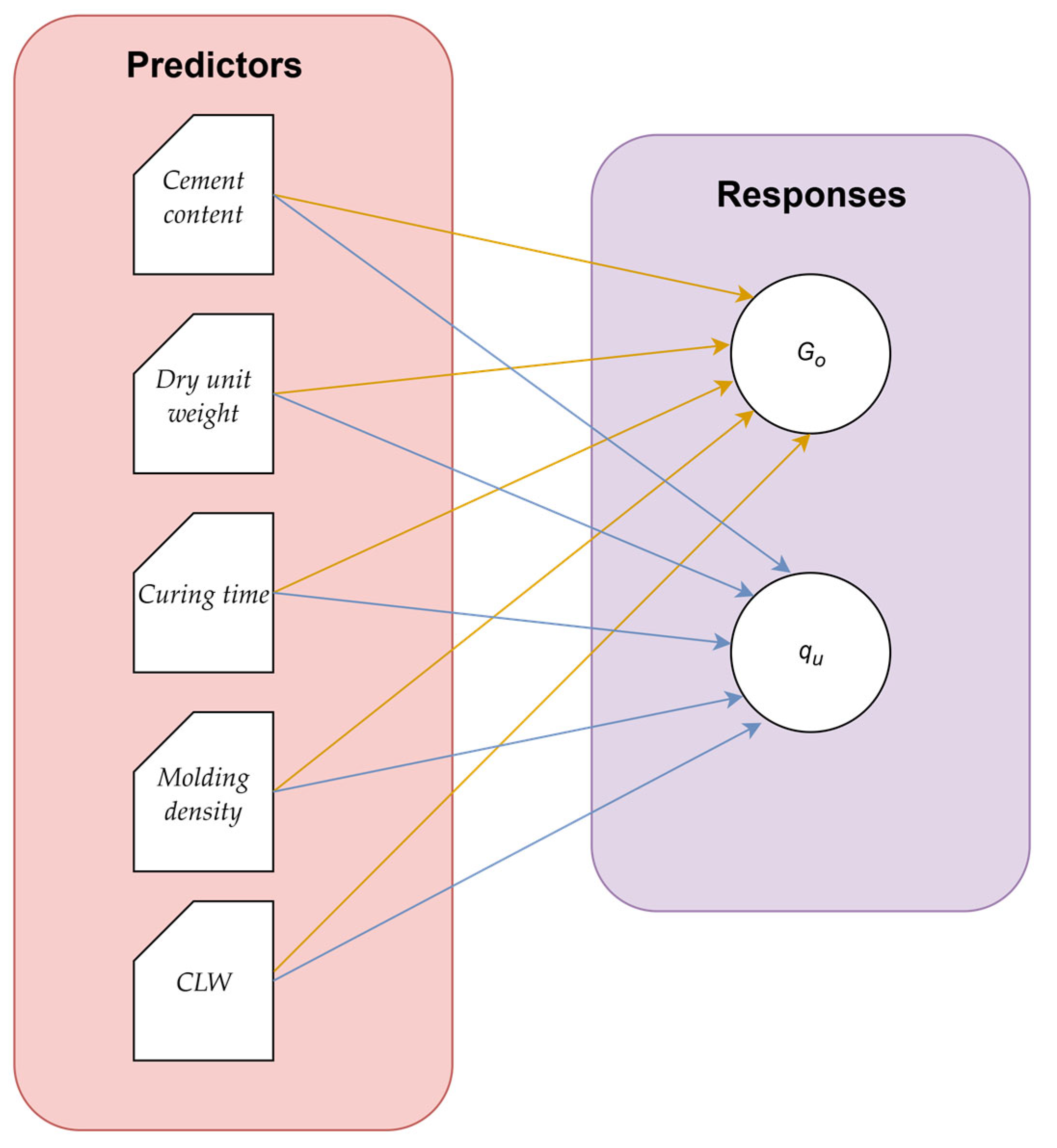

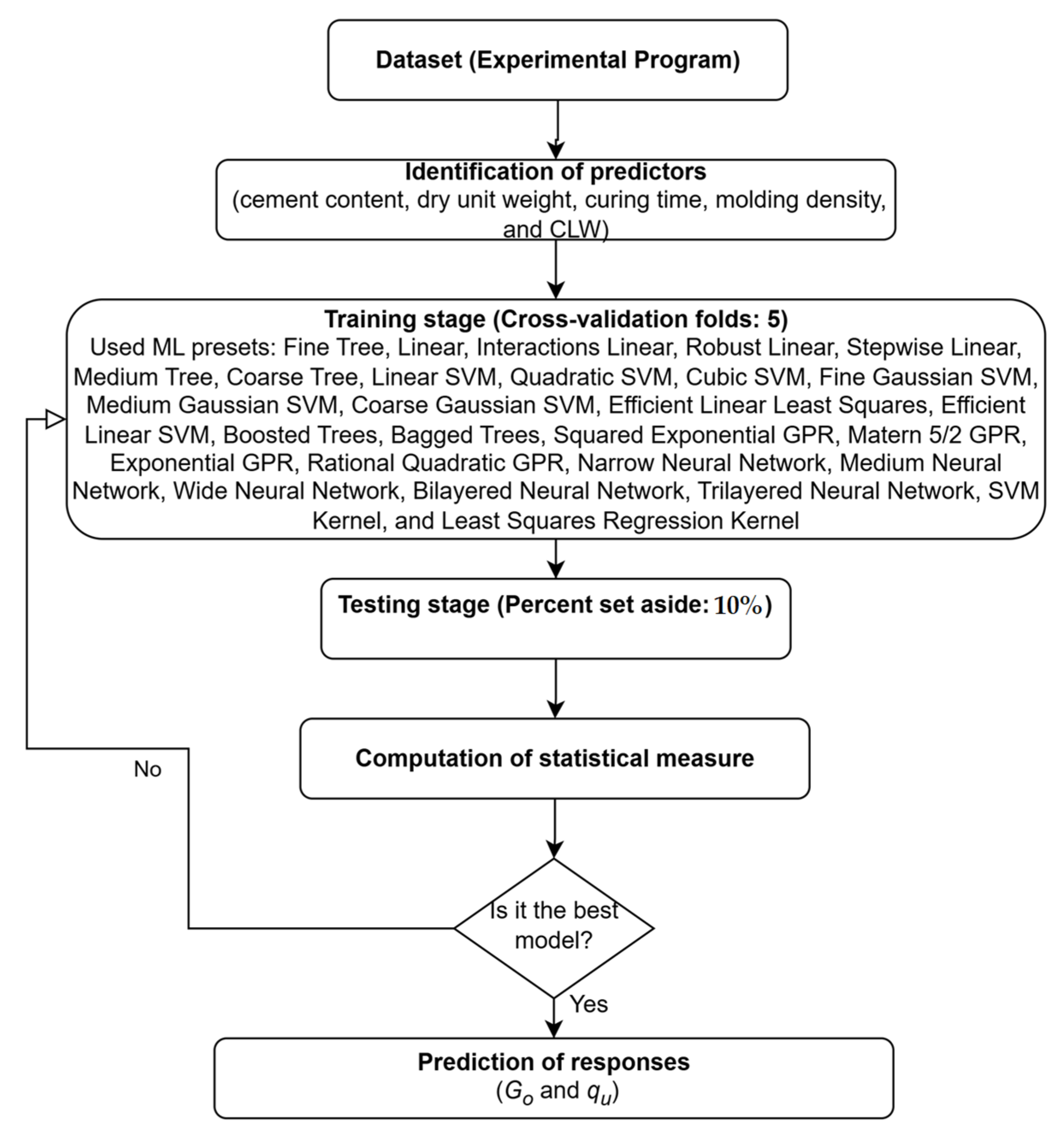

2.3. ML Methodology

- Square exponential kernel

- Exponential kernel

- Matern 5/2

- Rational quadratic:

3. Results and Discussion

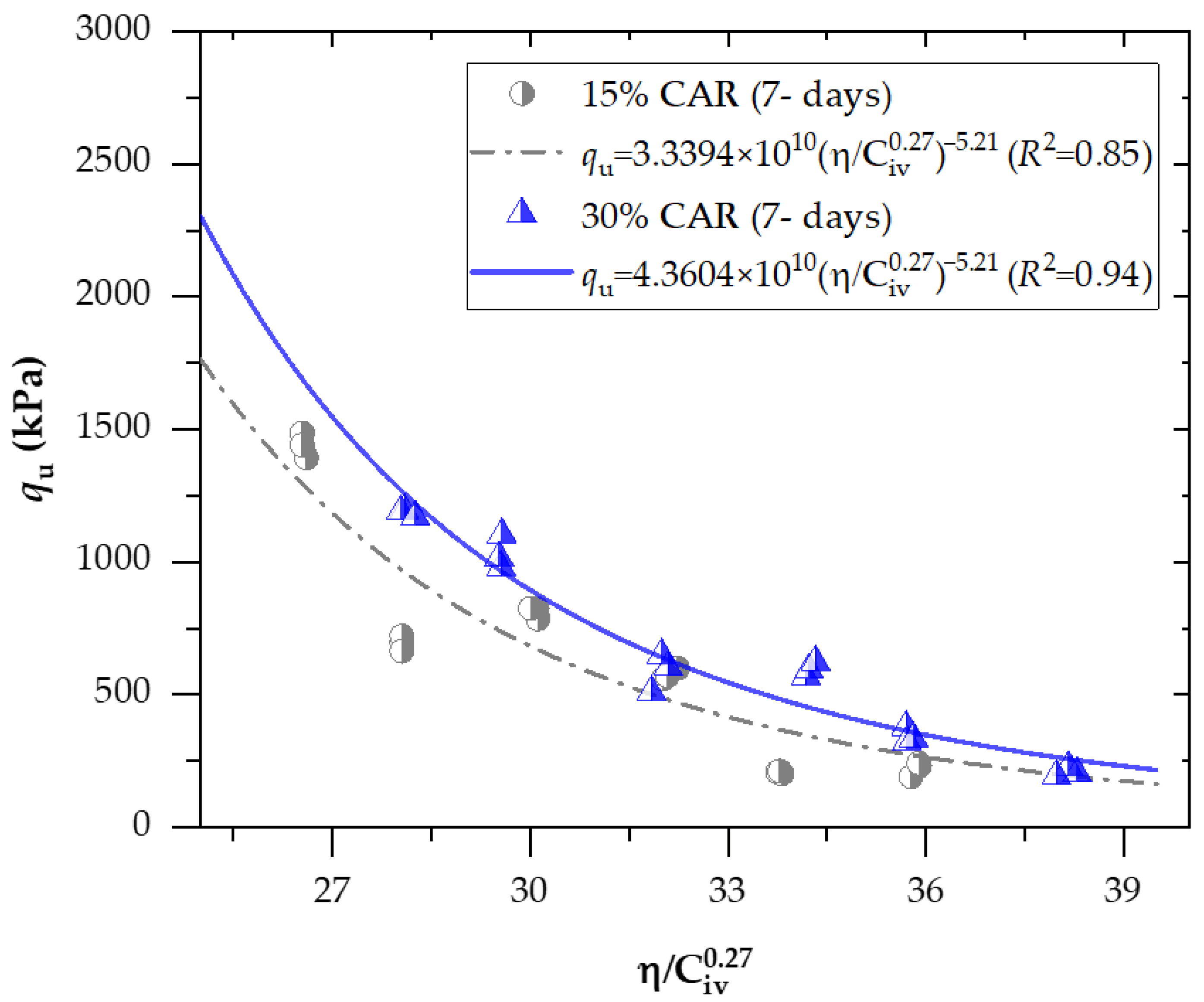

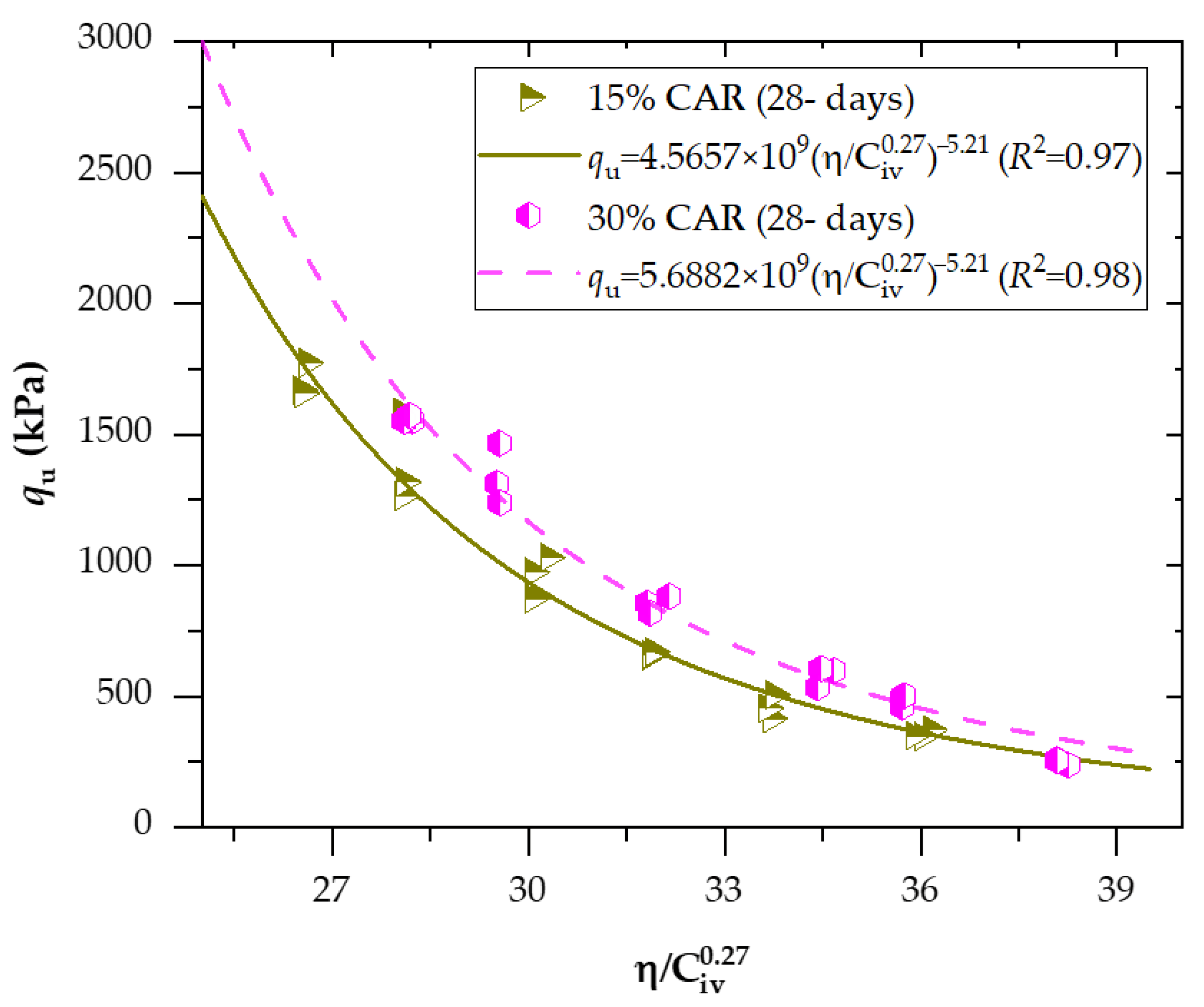

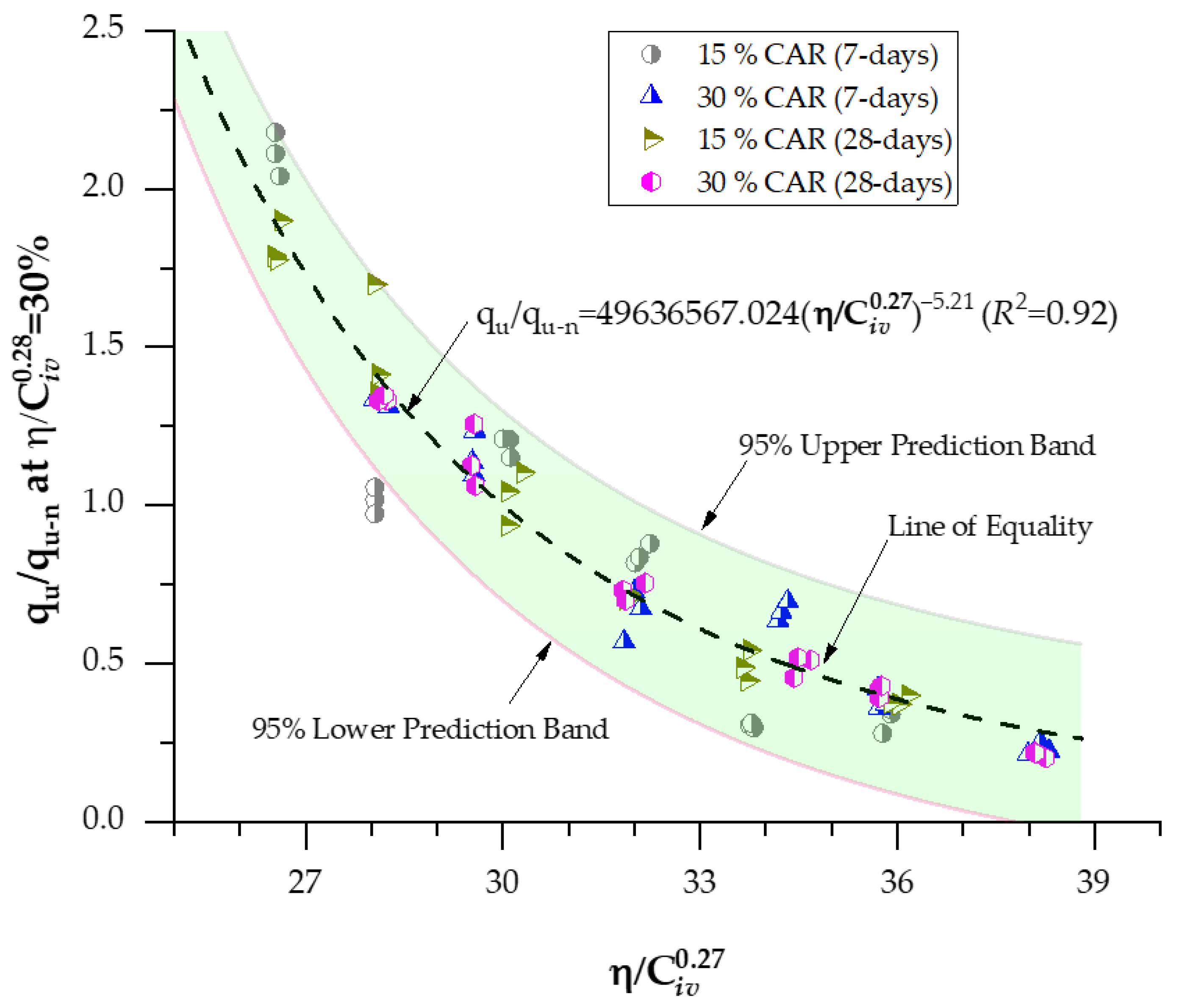

3.1. Effects of Porosity/Cement Index and Curing Periods on Strength and Stiffness for Soil−CAR−Cement Blends

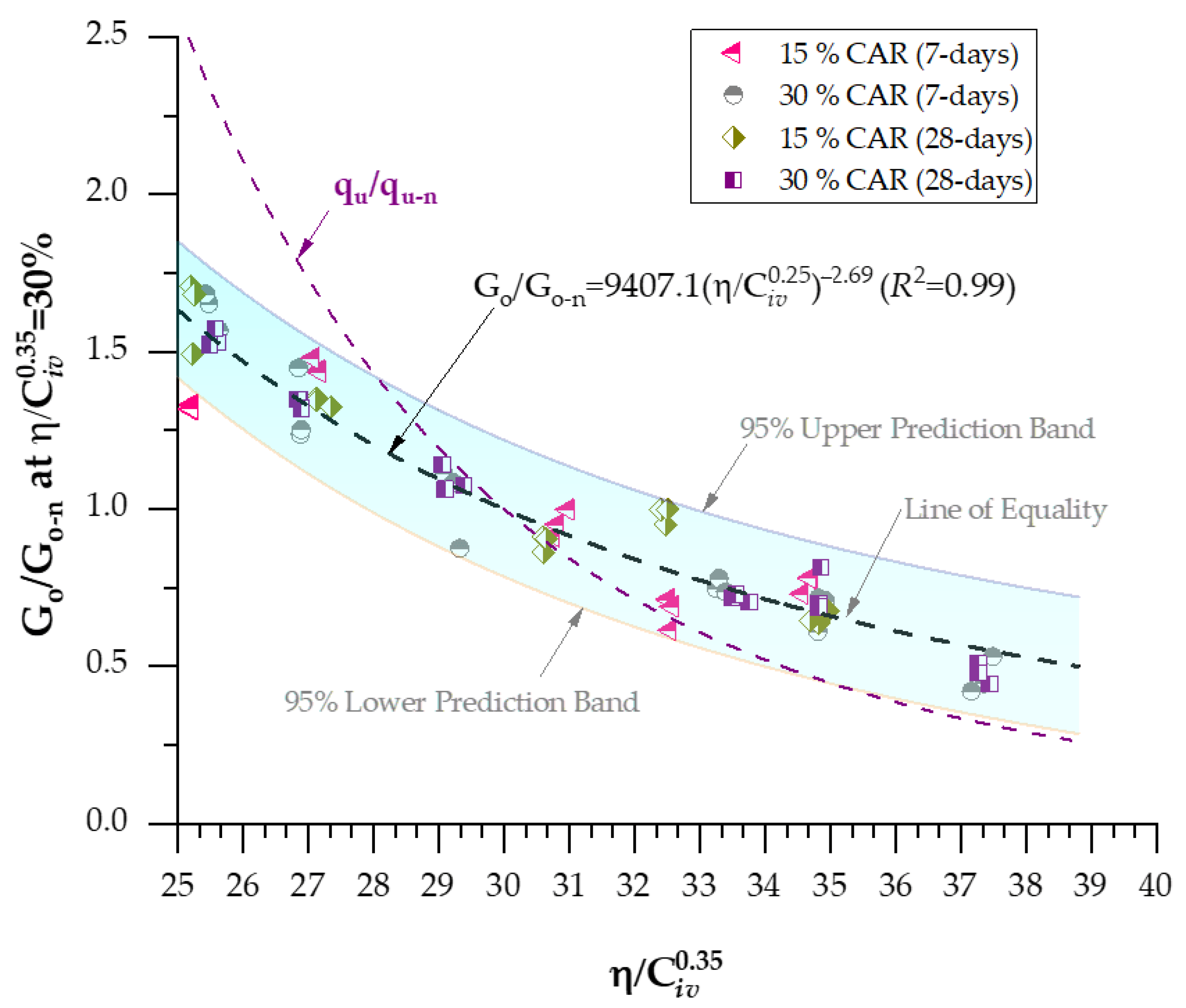

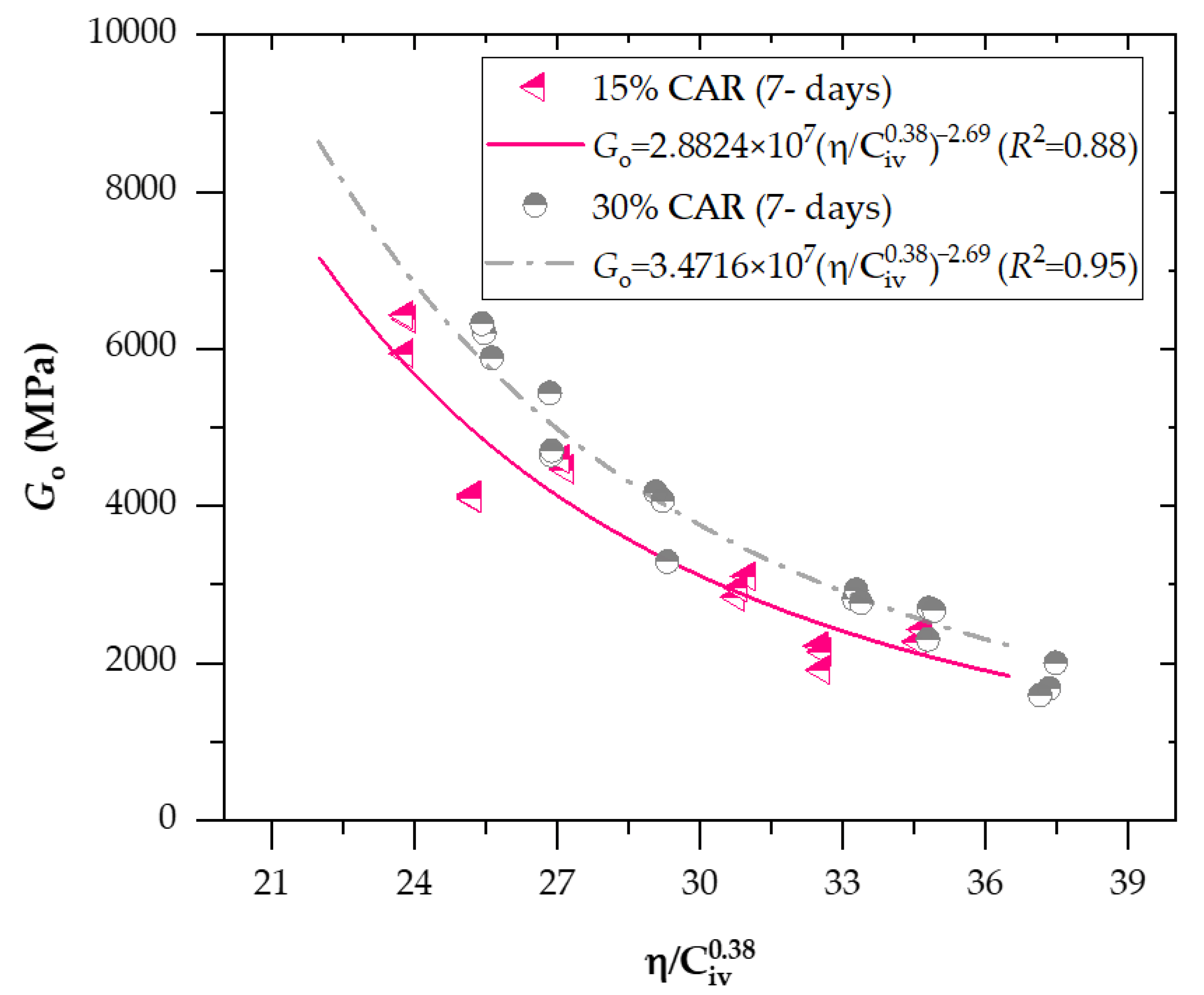

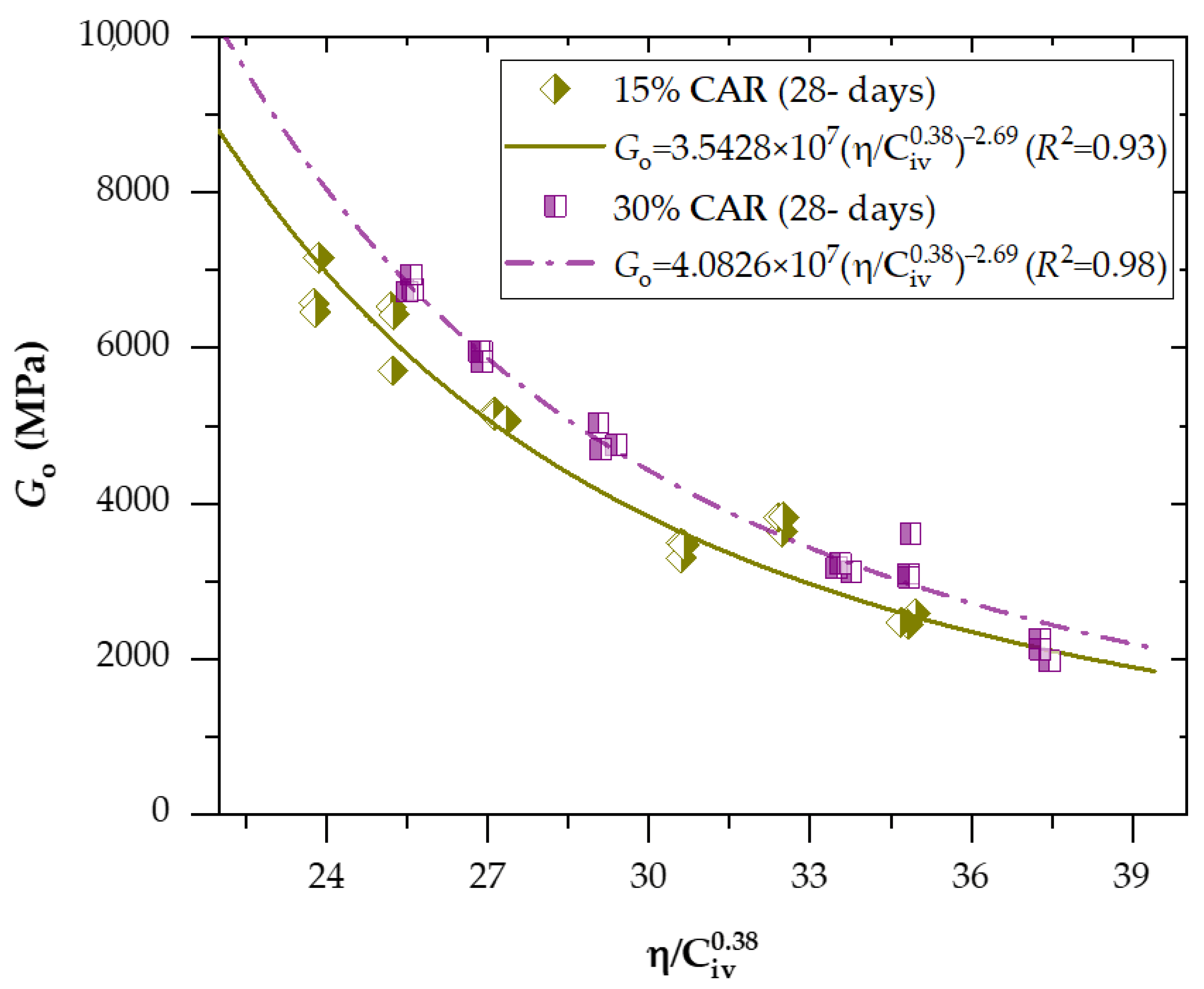

3.2. Effects of Porosity/Cement Index and Curing Periods on Stiffness for Soil−CAR−Cement Blends

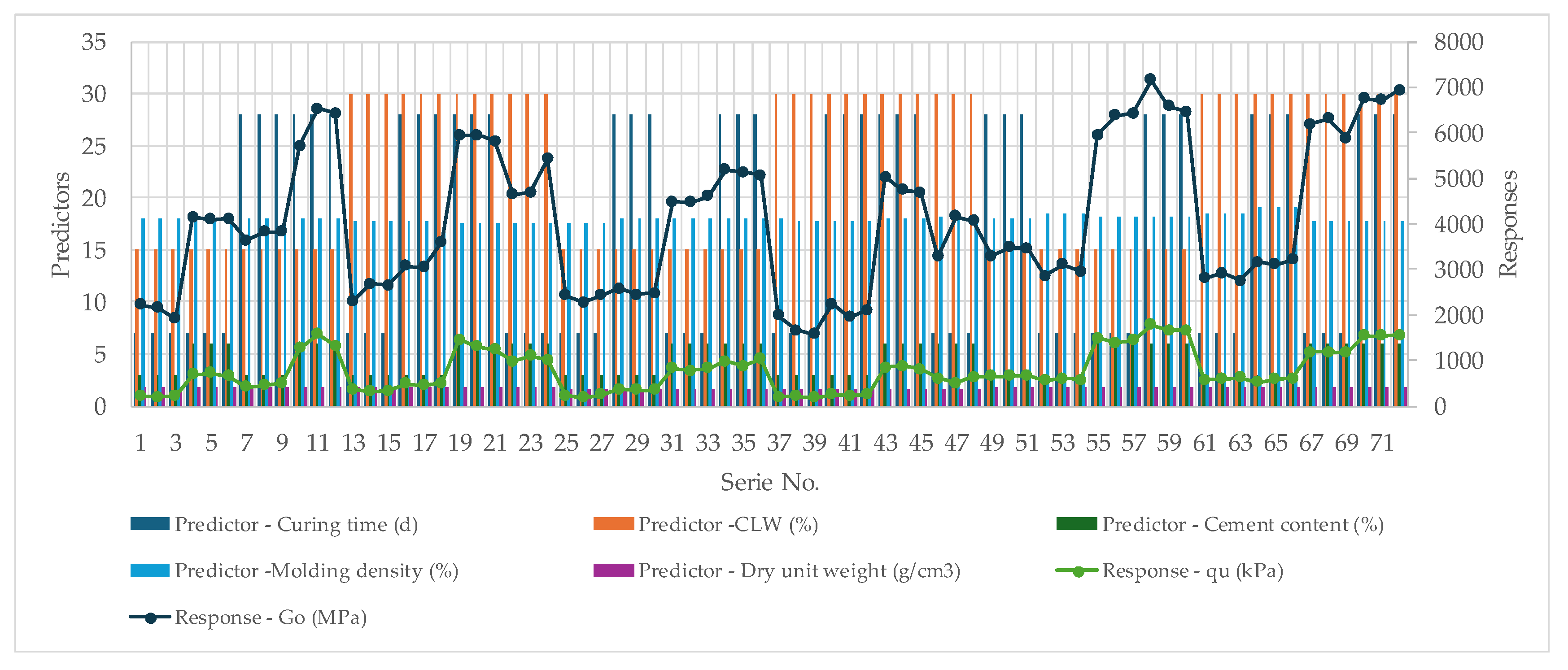

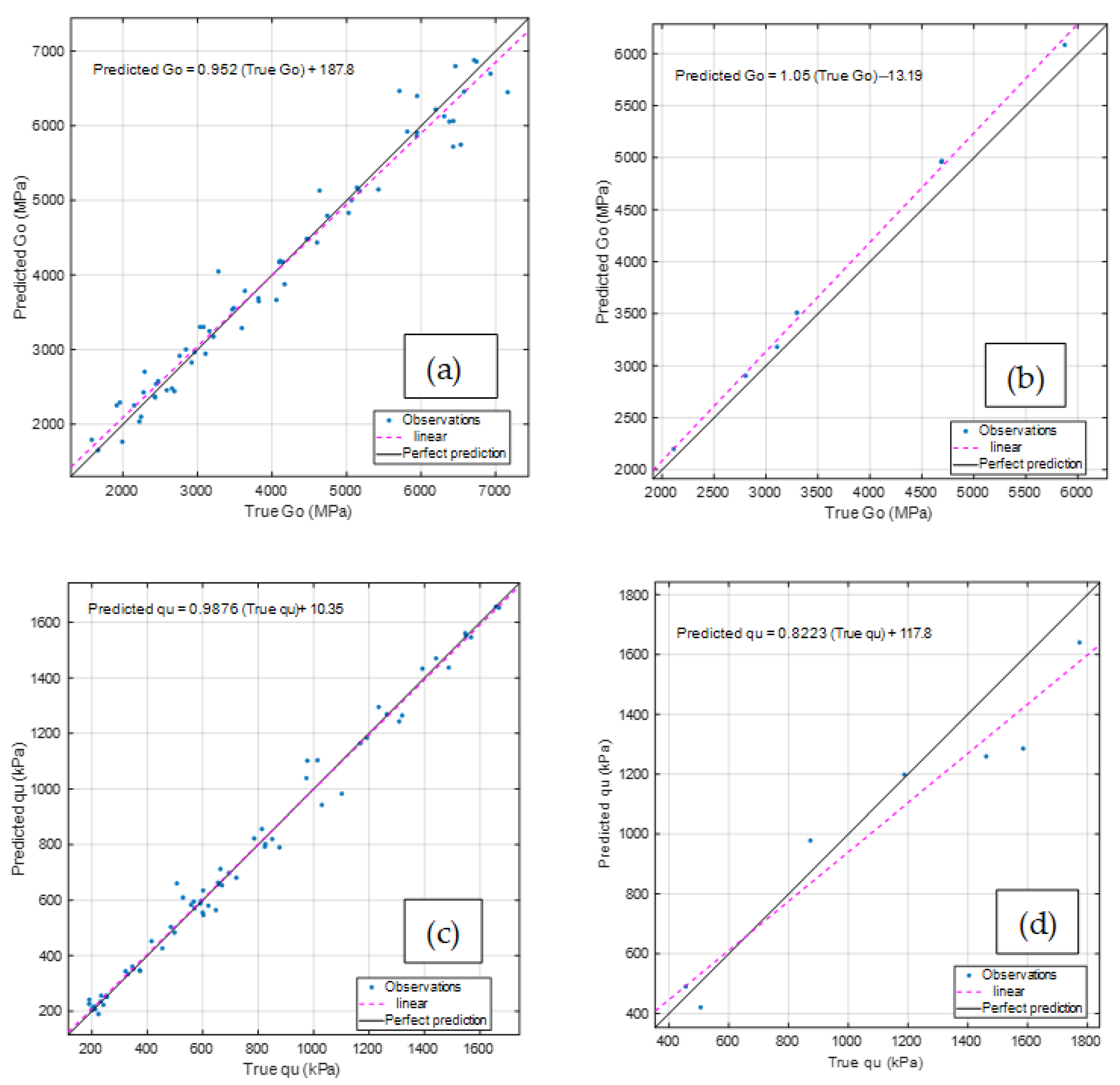

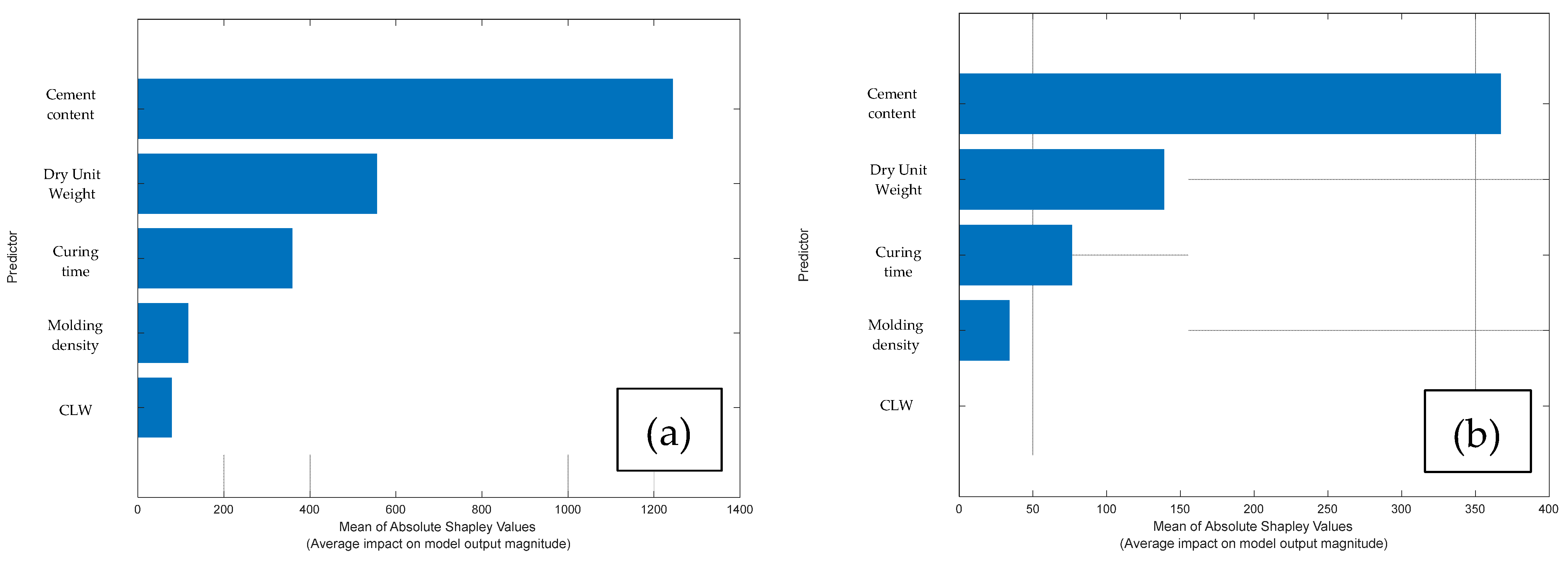

3.3. ML Application

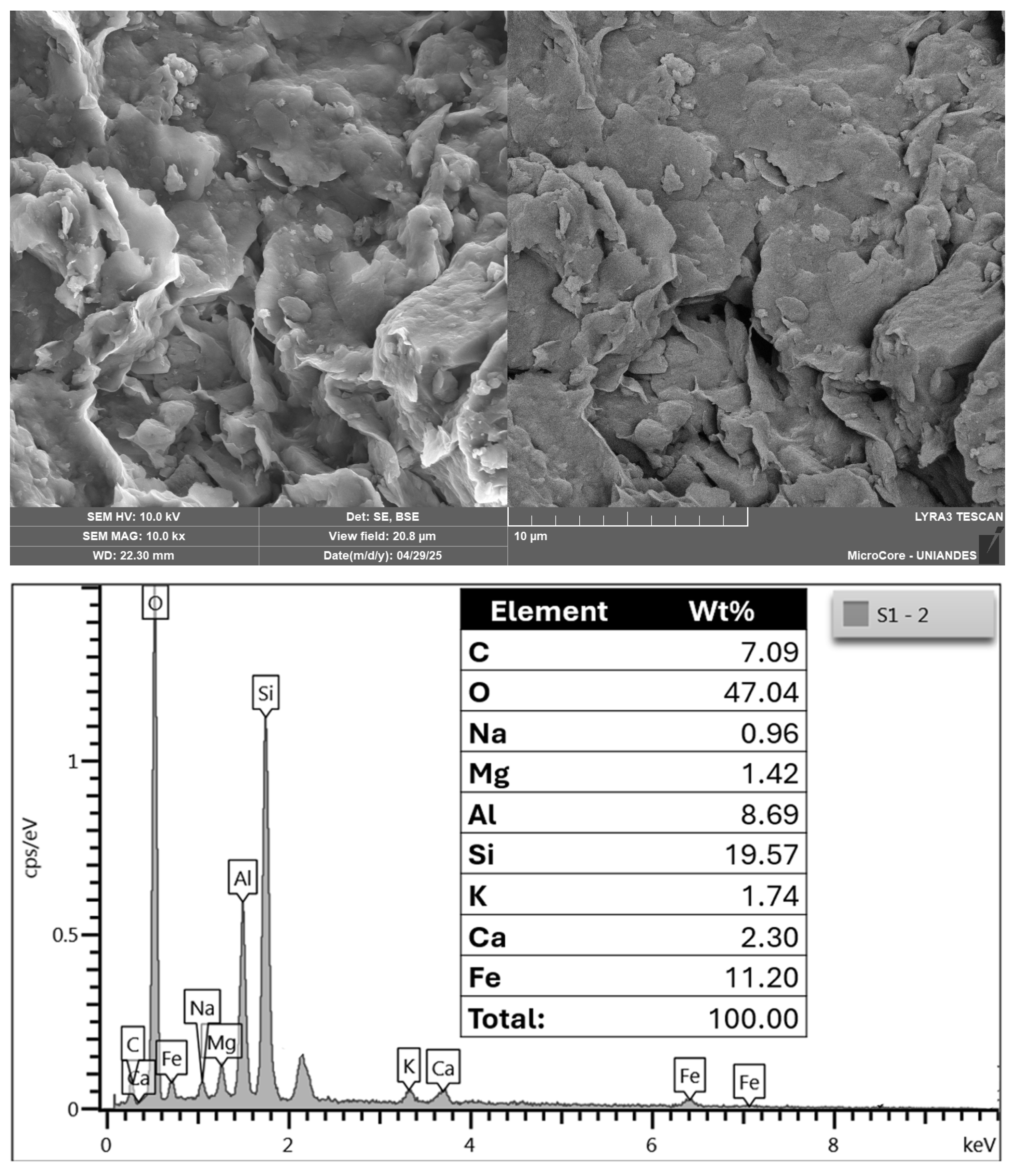

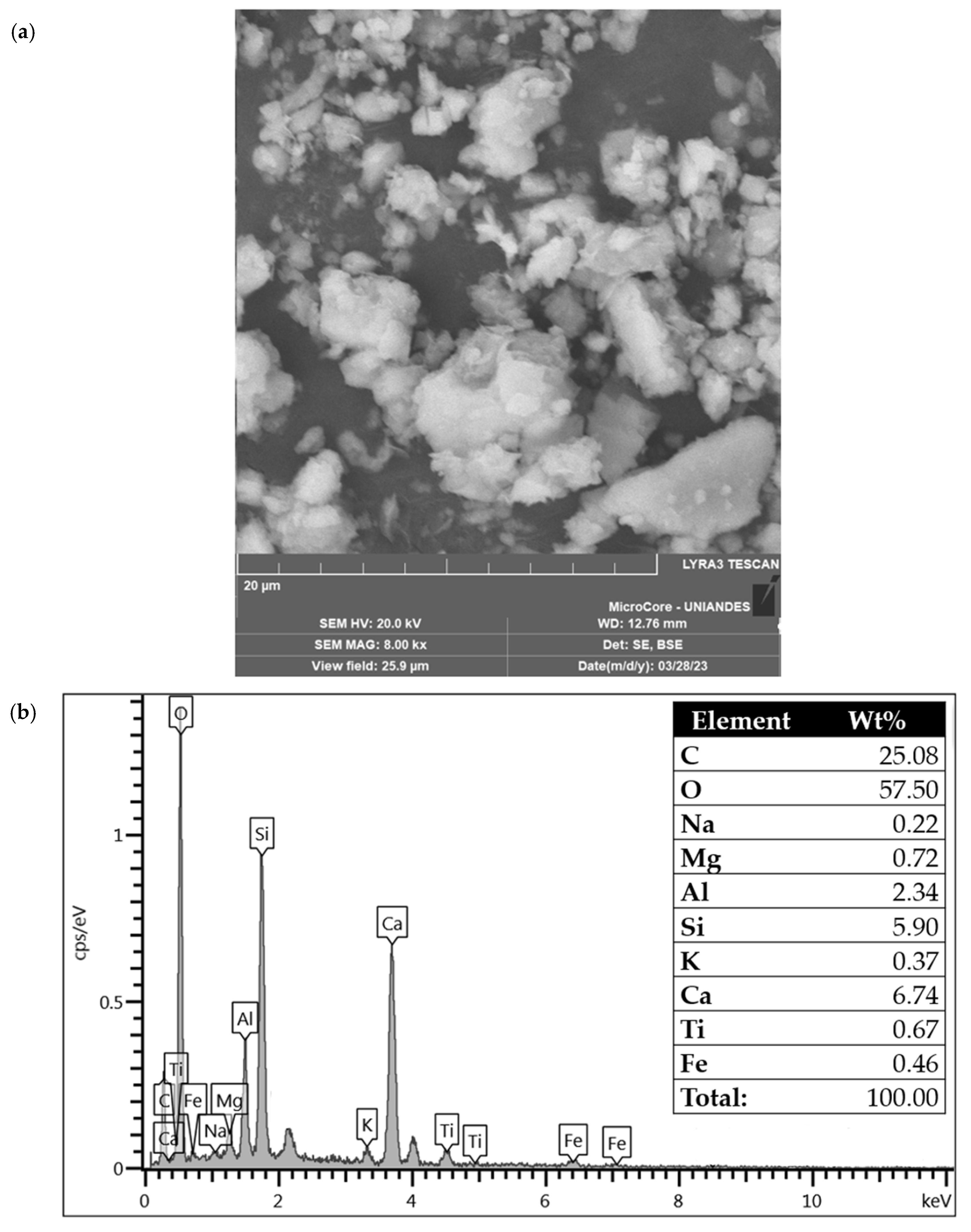

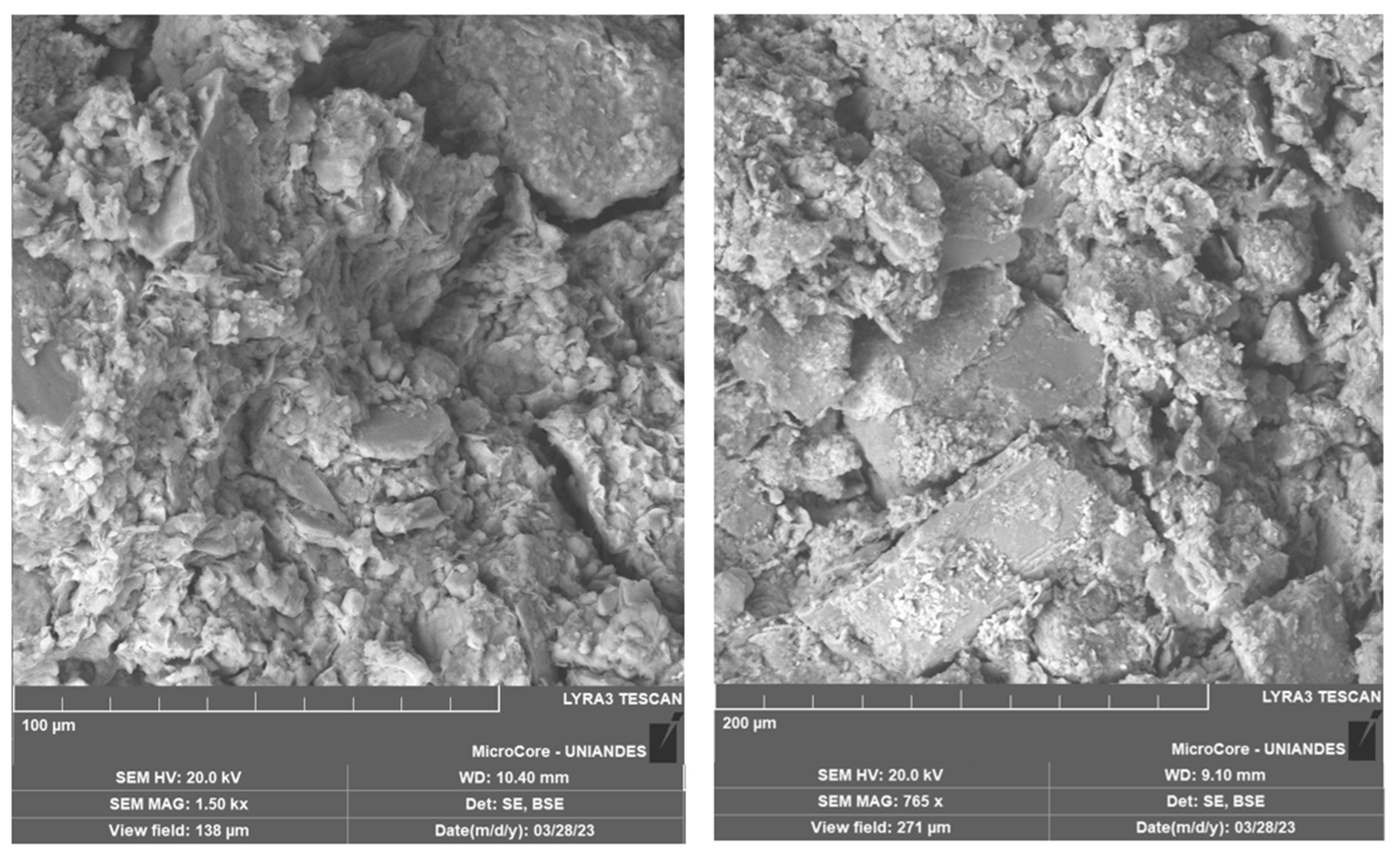

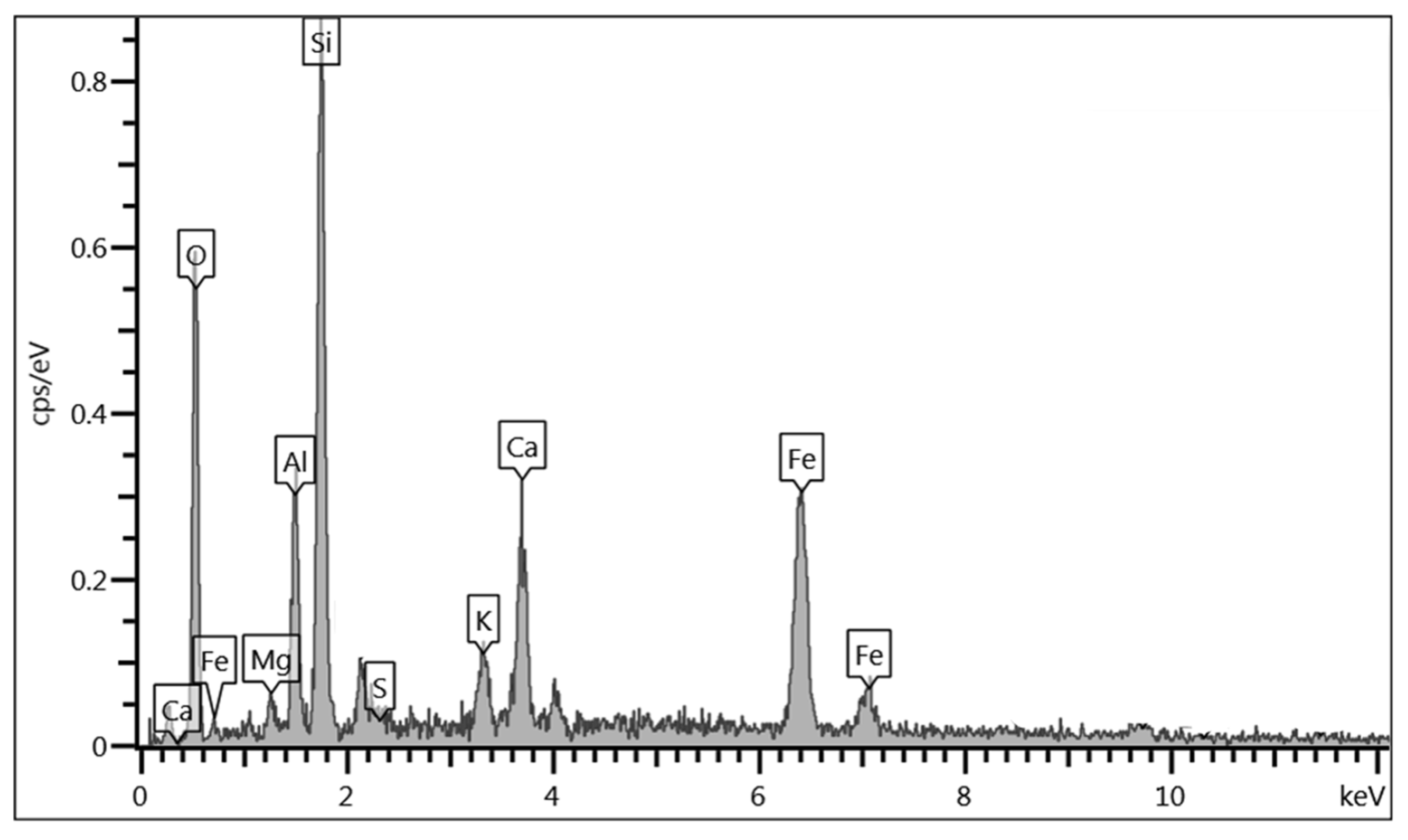

3.4. Microstructural Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gücek, S.; Gürer, C.; Žlender, B.; Taciroğlu, M.V.; Korkmaz, B.E.; Gürkan, K.; Bračko, T.; Macuh, B.; Varga, R.; Jelušič, P. Use of Lignin, Waste Tire Rubber, and Waste Glass for Soil Stabilization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie, A.; Yaghoubi, E.; Wasantha, P.L.P.; Van Staden, R.; Guerrieri, M.; Fragomeni, S. Mechanical and Physical Properties and Cyclic Swell-Shrink Behaviour of Expansive Clay Improved by Recycled Glass. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2204436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Pan, Y. Stabilization of Micaceous Residual Soil with Industrial and Agricultural Byproducts: Perspectives from Hydrophobicity, Water Stability, and Durability Enhancement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 430, 136450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, P.; Sharma, G.; Singh, R.M. Durability and Cost Analysis of a Soil Stabilized with Alkali-Activated Wastes: Fly Ash and Eggshell Powder. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 2961–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, S.; Hu, X.; Sarfraz, M.; Mohsin, M. Strategic Assessment of Energy Resources, Economic Growth, and CO2 Emissions in G-20 Countries for a Sustainable Future. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.d.J.A.; Ortega, R.T.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E. Experimental Stabilization of Clay Soils in Cartagena de Indias Colombia: Influence of Porosity/Binder Index. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.A.; Durán, A.P.; de la Rosa, Y.E.N. Sustainable Stabilization of Soil–RAP Mixtures Using Xanthan Gum Biopolymer. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blayi, R.A.; Sherwani, A.F.H.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Faraj, R.H.; Daraei, A. Strength Improvement of Expansive Soil by Utilizing Waste Glass Powder. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J.L.; Chai, J.; Sánchez, I. Strength and Microstructure of a Clayey Soil Stabilized with Natural Stone Industry Waste and Lime or Cement. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Pasche, E.; Specht, L.P.; Tanski, M. Key Parameters Controlling Dynamic Modulus of Crushed Reclaimed Asphalt Paving–Powdered Rock–Portland Cement Blends. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2018, 19, 1716–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blayi, R.A.; Sherwani, A.F.H.; Mahmod, F.H.R.; Ibrahim, H.H. Influence of Rock Powder on the Geotechnical Behaviour of Expansive Soil. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2021, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidigasu, S.S.R.; Lawer, K.A.; Gawu, S.K.Y.; Emmanuel, E. Waste Crushed Rock Stabilised Lateritic Soil and Spent Carbide Blends as a Road Base Material. Geomech. Geoengin. 2022, 17, 980–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasche, E.; Bruschi, G.J.; Specht, L.P.; Aragão, F.T.S.; Consoli, N.C. Fiber-Reinforcement Effect on the Mechanical Behavior of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement–Powdered Rock–Portland Cement Mixtures. Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.H.; Nahazanan, H.; Yusuf, B.; Toha, S.F.; Alnuaim, A.; El-Mouchi, A.; Elseknidy, M.; Mohammed, A.A. A Systematic Review of Machine Learning Techniques and Applications in Soil Improvement Using Green Materials. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.A.; Husain, O.; Abdulkareem, M.; Mohd Yunus, N.Z.; Jamaludin, N.; Mutaz, E.; Elshafie, H.; Hamdan, M. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Predicting the Compressive Strength of Soil and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag Mixtures. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Y.M.H.; Wudil, Y.S.; Zami, M.S.; Al-Osta, M.A. Machine Learning Approach for Assessment of Compressive Strength of Soil for Use as Construction Materials. Eng 2025, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Huo, W.; Yang, L. Efficient Machine Learning Method for Evaluating Compressive Strength of Cement Stabilized Soft Soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.I.; Hasan, M.; Islam, M.S.; Houda, M.; Abdallah, M.; Sobuz, M.H.R. Machine Learning Methods to Predict and Analyse Unconfined Compressive Strength of Stabilised Soft Soil with Polypropylene Columns. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2220492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, M.; Javed, I.; Ekinci, A. Evaluating the Strength, Durability and Porosity Characteristics of Alluvial Clay Stabilized with Marble Dust as a Sustainable Binder. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann Filho, H.C.; Consoli, N.C. Effect of Porosity/Cement Index on Behavior of a Cemented Soil: The Role of Dosage Change. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.A.; Diaz, K.C.; Royero, J.M.; Sierra, R.S.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E. Developing New Geomaterials: The Case of the Natural Rubber Latex Polymers in Soil Stabilization. Materials 2025, 18, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D4318-10; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- ASTM D854; Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Water Pycnometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM D698-12; Standard Test Method for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soils Using Standard Effort (12,400 Ft-Lbf/Ft3 (600 KN-m/m3)). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM D2487; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- Román Martínez, C.; Núñez de la Rosa, Y.E.; Estrada Luna, D.; Baldovino, J.A.; Bruschi, G.J. Strength, stiffness, and microstructure of stabilized marine clay-crushed limestone waste blends: Insight on characterization through porosity-to-cement index. Materials 2023, 16, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D1633-00(2007); Standard Test Methods for Compressive Strength of Molded Soil-Cement Cylinders. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007.

- ASTM C150; Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM C597-22; Standard Test Method for Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Consoli, N.C.; da Silva, A.; Barcelos, A.M.; Festugato, L.; Favretto, F. Porosity/Cement Index Controlling Flexural Tensile Strength of Artificially Cemented Soils in Brazil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta Baldovino, J.d.J.; Ekinci, A.; Bruschi, G.J. Novel Porosity-Water/Binder Index for Strength Prediction of Artificially Cemented Soils. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04023585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diambra, A.; Ibraim, E.; Festugato, L.; Corte, M.B. Stiffness of Artificially Cemented Sands: Insight on Characterisation through Empirical Power Relationships. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diambra, A.; Ibraim, E.; Peccin, A.; Consoli, N.C.; Festugato, L. Theoretical Derivation of Artificially Cemented Granular Soil Strength. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Párraga Morales, D.; Saldanha, R.B. A New Approach for Stabilization of Lateritic Soil with Portland Cement and Sand: Strength and Durability. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, B.Z.; Diambra, A.; Ibraim, E.; Festugato, L.; Consoli, N.C. Strength and Stiffness of Compacted Chalk Putty–Cement Blends. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 2955–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, G.J.; dos Santos, C.P.; Tonini de Araújo, M.; Ferrazzo, S.T.; Marques, S.F.V.; Consoli, N.C. Green Stabilization of Bauxite Tailings: Mechanical Study on Alkali-Activated Materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 06021007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Powder Rock | Type of Soil/Residue | Binder | w (%) | Molding γd (kN.m−3) | Strength (MPa) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volcanic rock dacite (30%) | Reclaimed asphalt pavement (70%) | Cement (3%) | 8 | 20.0 | 0.667 | [10] |

| Volcanic rock dacite (30%) | Reclaimed asphalt pavement (70%) | Cement (3%) | 8 | 21.0 | 1.385 | [10] |

| Volcanic rock dacite (30%) | Reclaimed asphalt pavement (70%) | Cement (3%) | 8 | 22.0 | 2.350 | [10] |

| Silicon natural rock powder (8%) | Expansive soil (MH) | - | 16.75 | 18.35 | 0.2435 | [11] |

| +Silicon natural rock powder (16%) | Expansive soil (MH) | - | 16.00 | 18.52 | 0.3036 | [11] |

| Silicon natural rock powder (24%) | Expansive soil (MH) | - | 16.75 | 18.35 | 0.363 | [11] |

| Granitic powder rock | Lateritic soil | Carbide Lime (3%) | 10.05 | 20.40 | 89.99% (CBR) | [12] |

| Granitic powder rock | Lateritic soil | Carbide Lime (5%) | 10.25 | 20.70 | 168.53% (CBR) | [12] |

| Granitic powder rock | Lateritic soil | Carbide Lime (7%) | 10.45 | 21.10 | 185.64% (CBR) | [12] |

| Granitic powder rock (30%) | - | Cement (3%) and PPF (0.5%) | 9.0 | 20.0 | 1200 (Mr) | [13] |

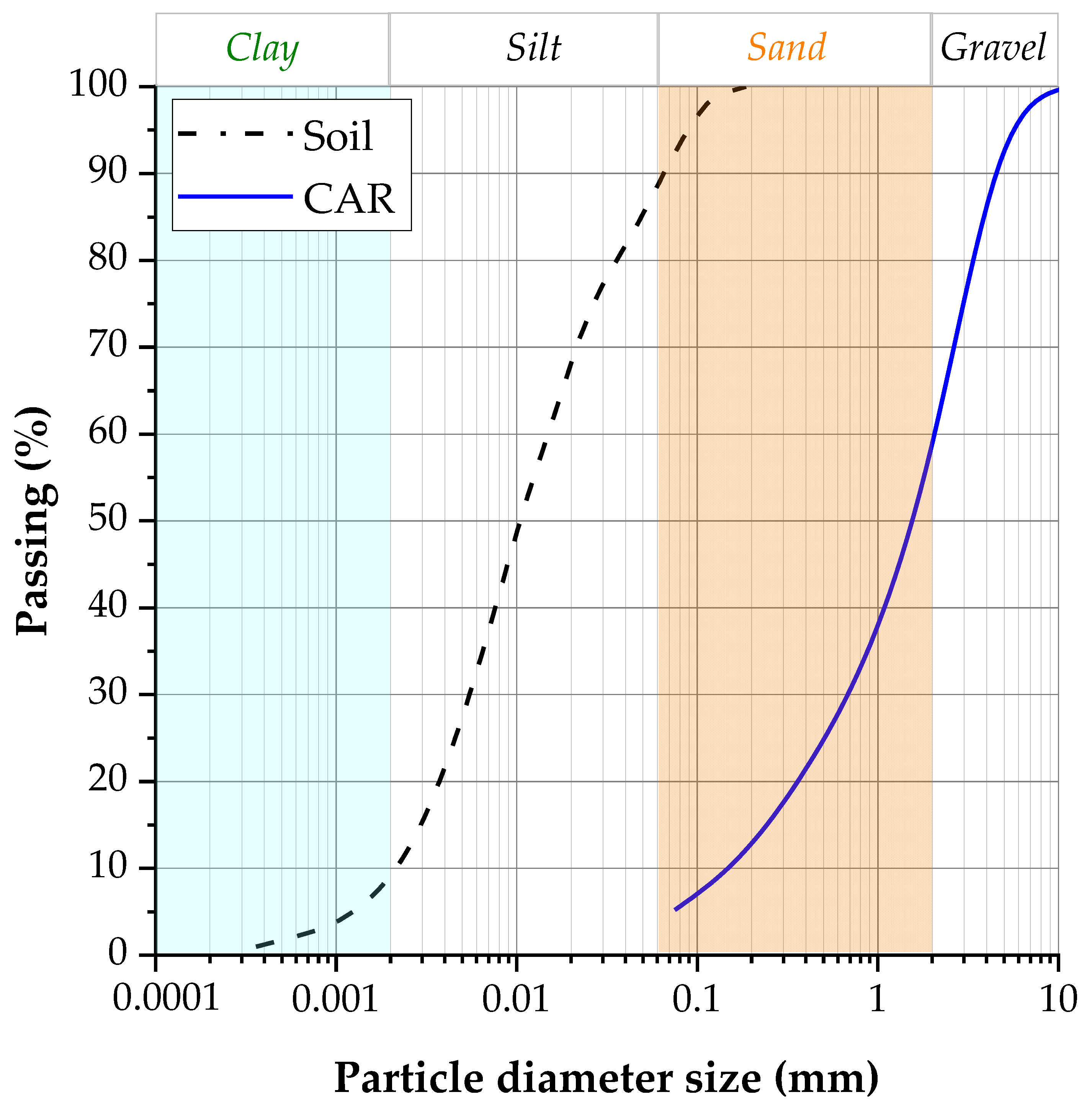

| Properties | Soil | CAR |

|---|---|---|

| LL Limit Liquid of soil, % | 42.00 | - |

| PL Plastic Limit of soil, % | 26.05 | - |

| PI Plastic Index of soil, %, (i.e., LL-PL) | 15.95 | - |

| Gravel particles (D-2 mm), % | 0 | 41 |

| Coarse sand particle size (0.6 mm- D-2 mm), % | 0 | 32 |

| Medium sand particle size (0.2 mm- D-0.6 mm), % | 0 | 13 |

| Fine sand particle size (0.06 mm- D-0.2 mm), % | 12 | 14 |

| Silt particle size (0.002 mm- D-0.06 mm), % | 78 | - |

| Clay particles size (D < 0.002 mm), % | 10 | - |

| Effective diameter (D10), mm | 0.0021 | 0.15 |

| Mean particle diameter (D50), mm | 0.011 | 1.6 |

| Uniformity coefficient of materials (Cu) | 7.14 | 13.67 |

| Coefficient of curvature of materials (Cc) | 0.96 | 1.59 |

| The specific gravity of the soil sample and CAR | 2.80 | 2.52 |

| Activity of clay, A [A = PI/(% < 0.002 mm)] | 1.60 | - |

| Color of raw materials | Black | Gray |

| Classification of raw materials (USCS) | CL | SW |

| Element | Soil Composition (%) | CAR Composition (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 66 | 9.0 |

| Al2O3 | 21.7 | 1.3 |

| SO3 | 5.0 | - |

| K2O | 3.1 | - |

| CaO | 3.0 | 72.4 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| TiO2 | 0.3 | - |

| MgO | - | 2.1 |

| Mn | - | 14.3 |

| Preset | qu | Go | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation | Testing | Validation | Testing | |||||

| RMSE (kPa) | R2 | RMSE (kPa) | R2 | RMSE (MPa) | R2 | RMSE (MPa) | R2 | |

| Fine Tree | 170.6 | 0.845 | 295.2 | 0.629 | 534.6 | 0.894 | 231.9 | 0.964 |

| Linear | 132.9 | 0.906 | 200.5 | 0.829 | 417.5 | 0.936 | 380.5 | 0.903 |

| Interactions Linear | 89.1 | 0.958 | 156.6 | 0.896 | 397.7 | 0.942 | 243.2 | 0.960 |

| Robust Linear | 135.0 | 0.903 | 192.0 | 0.843 | 425.8 | 0.933 | 390.2 | 0.898 |

| Stepwise Linear | 113.8 | 0.931 | 155.5 | 0.897 | 428.4 | 0.932 | 380.5 | 0.903 |

| Medium Tree | 220.3 | 0.742 | 393.3 | 0.341 | 688.5 | 0.825 | 290.6 | 0.943 |

| Coarse Tree | 433.7 | 0.000 | 621.6 | −0.646 | 1645.7 | 0.000 | 1264.2 | −0.070 |

| Linear SVM | 140.9 | 0.894 | 189.8 | 0.847 | 424.2 | 0.934 | 407.8 | 0.889 |

| Quadratic SVM | 83.9 | 0.963 | 171.6 | 0.875 | 436.8 | 0.930 | 312.2 | 0.935 |

| Cubic SVM | 254.2 | 0.656 | 140.1 | 0.916 | 2151.4 | −0.709 | 208.8 | 0.971 |

| Fine Gaussian SVM | 171.7 | 0.843 | 174.7 | 0.870 | 512.4 | 0.903 | 229.5 | 0.965 |

| Medium Gaussian SVM | 90.0 | 0.957 | 164.0 | 0.886 | 359.9 | 0.952 | 225.6 | 0.966 |

| Coarse Gaussian SVM | 193.6 | 0.801 | 293.6 | 0.633 | 564.7 | 0.882 | 377.7 | 0.905 |

| Efficient Linear Least Squares | 261.3 | 0.637 | 299.9 | 0.617 | 788.1 | 0.771 | 729.3 | 0.644 |

| Efficient Linear SVM | 372.9 | 0.261 | 544.4 | −0.262 | 1575.5 | 0.084 | 1365.0 | −0.247 |

| Boosted Trees | 127.3 | 0.914 | 302.7 | 0.610 | 460.4 | 0.922 | 175.9 | 0.979 |

| Bagged Trees | 155.6 | 0.871 | 340.1 | 0.507 | 584.7 | 0.874 | 273.3 | 0.950 |

| Squared Exponential GPR | 49.9 | 0.987 | 150.6 | 0.903 | 301.2 | 0.966 | 214.0 | 0.969 |

| Matern 5/2 GPR | 47.9 | 0.988 | 150.8 | 0.903 | 294.0 | 0.968 | 209.4 | 0.971 |

| Exponential GPR | 46.6 | 0.988 | 155.0 | 0.898 | 284.8 | 0.970 | 193.8 | 0.975 |

| Rational Quadratic GPR | 47.3 | 0.988 | 150.7 | 0.903 | 291.2 | 0.969 | 208.4 | 0.971 |

| Narrow Neural Network | 104.1 | 0.942 | 155.3 | 0.897 | 327.0 | 0.961 | 179.7 | 0.978 |

| Medium Neural Network | 71.6 | 0.973 | 150.5 | 0.903 | 1738.0 | −0.115 | 186.6 | 0.977 |

| Wide Neural Network | 93.0 | 0.954 | 151.4 | 0.902 | 1357.7 | 0.319 | 224.1 | 0.966 |

| Bilayered Neural Network | 67.0 | 0.976 | 152.2 | 0.901 | 761.0 | 0.786 | 205.7 | 0.972 |

| Trilayered Neural Network | 65.2 | 0.977 | 160.6 | 0.890 | 662.8 | 0.838 | 200.5 | 0.973 |

| SVM Kernel | 440.4 | −0.032 | 693.3 | −1.047 | 1678.9 | −0.041 | 1222.9 | −0.001 |

| Least Squares Regression Kernel | 210.9 | 0.764 | 323.7 | 0.554 | 738.0 | 0.799 | 456.4 | 0.861 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arrieta Baldovino, J.D.J.; Coronado-Hernandez, O.E.; Nuñez de la Rosa, Y.E. Integrating the Porosity/Binder Index and Machine Learning Approaches for Simulating the Strength and Stiffness of Cemented Soil. Materials 2025, 18, 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245504

Arrieta Baldovino JDJ, Coronado-Hernandez OE, Nuñez de la Rosa YE. Integrating the Porosity/Binder Index and Machine Learning Approaches for Simulating the Strength and Stiffness of Cemented Soil. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245504

Chicago/Turabian StyleArrieta Baldovino, Jair De Jesús, Oscar E. Coronado-Hernandez, and Yamid E. Nuñez de la Rosa. 2025. "Integrating the Porosity/Binder Index and Machine Learning Approaches for Simulating the Strength and Stiffness of Cemented Soil" Materials 18, no. 24: 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245504

APA StyleArrieta Baldovino, J. D. J., Coronado-Hernandez, O. E., & Nuñez de la Rosa, Y. E. (2025). Integrating the Porosity/Binder Index and Machine Learning Approaches for Simulating the Strength and Stiffness of Cemented Soil. Materials, 18(24), 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245504