Adjunctive Procedures in Immediate Implant Placement: Necessity or Option? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Development and Registration

2.2. Criteria Definition for PICOS Framework

- Population: Adults requiring a single dental implant in a post-extraction socket in the esthetic area (maxillary or mandibular premolar-to-premolar region);

- Intervention: Use of any biomaterial, grafting material, and grafting technique as an adjunctive approach during IIP;

- Comparison: IIP without the use of any adjunctive material/approach;

- Outcomes

- Primary: Implant survival rate; clinically assessed and patient-reported esthetic outcomes;

- Secondary: Soft and hard tissue dimensional changes, keratinized tissue changes and self-reported post-operative pain.

- Study Design: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs).

2.3. Literature Search Restrictions

- Eligibility criteria

- Population: Human participants aged ≥18 years; Patients receiving single immediate dental implants within the esthetic area.

- Comparison: Immediate implant placement performed without the use of any grafting nor adjunctive material.

- Outcomes: Studies reporting on at least one of the review’s primary or secondary outcomes.

- Study design: RCTs; studies published in English; minimum of 10 participants per study group; Minimum follow-up of 6 months after IIP.

2.4. Information Sources, Search Strategies and Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment and Certainty Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

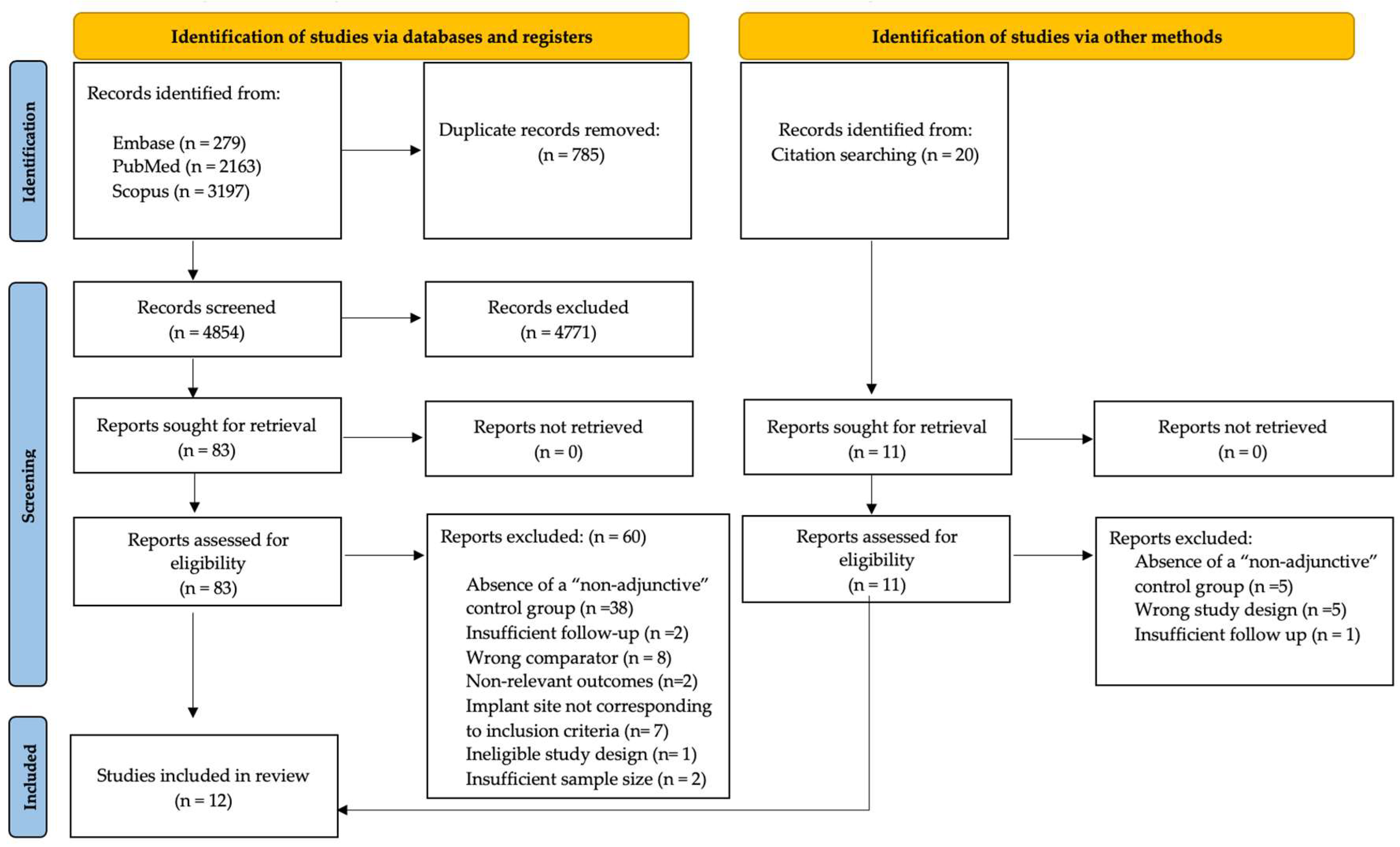

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Study Design and Study Population

3.2.2. Type of Intervention

- Xenografts

| Author (Year) | Country (Setting) | Participants (N) Gender, Smoking | Mean Age (Year) Mean ± SD | Follow-Up in Months | Reason(s) for Extraction | Socket Morphology | Intervention(s) | Implant Characteristics | Timing and Type of Provisionalization | Measurements Methods | Outcomes | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft | ||||||||||||

| Cardaropoli et al. (2014) [17] | Italy (Turin, Private Practice) | 52 15 M, 11 F (Test) 14 M, 12 F (Control) Smokers: included smokers < 10 cig/day (requested to stop smoking before and after surgery) | 42 ± 14 years (Test) 44 ± 13 years (Control) | 12 | Crown/root fracture, endodontic treatment failure, advanced caries | Second premolar to second premolar, with intact buccal plate (maxillary and mandibular) | Flapless extraction, with elevation of the interdental papillae only when necessary Bone-to-implant gap filled with DBBM blended with collagen and covered with a porcine-derived collagen membrane, secured with single sutures. | Brand: Biomet 3i (Osseotite Tapered Certain); Type: NR; Macrodesign: conical/tapered; Surface: Osseotite; Connection: NR; Length: 11.5–15 mm; Diameter: 3.25–5 mm; Position: crestal “flush” | Titanium healing abutment positioned at the end of the surgery Provisional crown cemented at 3 months | Cast-based measurement at the time of implant insertion (T0) and 12 months later (T12) Examiner calibration: NR | Survival rate, ridge width, ridge height | Ridge preservation with DBBM blended with collagen reduced soft tissue alterations and improved esthetic stability compared with IIP alone |

| Bittner et al. (2020) [47] | USA (Columbia Universy) | 32 9 M, 23 F Smokers: excluded | 52.3 ± 4 years Age range: 26–86 years | 12 | Caries, fracture, poor endodontic prognosis | First premolar to first premolar, with intact buccal bone plate (maxillary) | DBBM blended with collagen | Brand: Zimmer Biomet (Certain); Type: NR; Macrodesign: NR; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 8.5–15 mm; Diameter: 3.25–5.0 mm; Position: platform at the buccal crest or 1 mm below | Implants with Insertion torque > 20 N/cm restored with an immediate full-contour screw-retained provisional occlusion (n = 22). Implants with primary stability ≤ 20 Ncm restored with customized healing abutment (n = 10). | Clinical Measurements CBCT Digital Cast Analysis Examiner calibration and blinding: N | Horizontal and vertical soft tissue dimensional changes, post-operative complications | DBBM blended with collagen with immediate implants showed no major differences, except slightly less horizontal changes and better distal papilla stability at 12 months |

| Mastrangelo et al. (2018) [44] | Italy (Multicenter, private practice) | 108 (102 analysed) 31 M, 20 F (Test) 32 M, 19 F (Control) Smokers: included; n: 48 %24.3 | 44 ± 6.7 years Age range: 18–72 years | 36 | NR | Premolars (maxillary) | Small full-thickness labial flaps were repositioned to completely cover the implant DBBM plus pericardium membrane | Brand: Dentaurum (tioLogic); Type: NR; Macrodesign: NR; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 11–13 mm; Diameter: 3.7–4.2 mm; Position: implant head 1–2 mm below the most apical bone peak; slightly palatal. | Standard titanium abutment and removable prosthesis | X-ray Clinical measurement Examiner calibration and blinding: both calibration and blinding applied | Survival rate, peri-implant marginal bone loss, PES, PPD post-operative complications | The use of an anorganic bovine bone substitute with a resorbable collagen barrier around the single immediate postextractive implant does not influences marginal bone loss and probing depth but seems to improve the esthetic outcomes after a 3-year follow-up. |

| Jacobs et al. (2020) [45] | USA (University of North Carolina) | 33 8 (42%) M, 11 (58%) F (Test) 6 (43%) M, 8 (57%) F Smokers: excluded | 53 ± 20 (Test) 65 ± 14 (Control) | 10 | NR | First premolar to first premolar, with no adjacent edentulous spaces (maxillary) | DBBM blended with collagen | Brand: Dentsply Sirona (OsseoSpeed TX Profile); Type: NR; Macrodesign: sloped-platform; Surface: OsseoSpeed; Connection: NR; Length: 11–15 mm; Diameter: 4.5 mm; Position: implant–abutment interface aligned with the facial osseous crest; ~2 mm palatal to the mucosal zenith | Bonded pontic Natural crown An interim acrylic single-tooth removable partial denture 12 weeks after implant placement screw-retained provisionalization | PVS impression of the maxillary anterior sextant Quantitative photographic analysis using standardized digital photographs CBCT Examiner calibration and blinding: blinding applied | PES Vertical and horizontal hard tissue changes Vertical soft tissue changes | Mucosal and hard tissue changes after flapless immediate placement of sloped-platform implants did not differ significantly whether or not DBBM blended with collagen was added to the facial extraction gap |

| Girlanda et al. (2019) [39] | Brasil (Dental Clinic of Paulista University) | 22 4 M, 18 F Smokers: excluded | Age range: 21 to 58 years | 6 | NR | Incisors, with intact buccal alveolar wall (maxillary) | DBBM blended with collagen with a flapless approach | Brand: Biomet 3i (Full Osseotite Tapered Certain); Type: NR; Macrodesign: tapered; Surface: Full Osseotite; Connection: internal hexagon; Length: NR; Diameter: 4.1 mm; Position: implant shoulder 3 mm apical to the buccogingival margin; palatal position | Temporary abutment for 3 months, followed by fixed prosthesis | CBCT and 3D Imaging Clinical measurement with standardize stent Examiner calibration and blinding: both calibration and blinding applied | soft tissue height. buccal GAP bone tissue, width | In the anterior maxilla, flapless immediate implant placement with DBBM blended with collagen and immediate provisionalization resulted in superior preservation of both hard and soft tissues compared to sites without biomaterial |

| Grassi et al. (2019) [40] | Italy (University of Bari) | 45 Flap-graft 6 M, 9 F Flap-nograft 6 M, 8 F Noflap-nograft 6 M, 9 F Smokers: included smokers < 10 cig/day | 47.3 ± 12.9 years | 6 | NR | Premolars, with more than 4 mm of apical bone and no more than a 3 mm loss in the buccal bone plate (maxillary) | 15 Flap-graft, 14 Flap-nograft 15 Noflap-nograft, residual space between the implant surface and socket walls grafted with cortical bone of equine origin, fully enzyme deantigenized | Brand: Bone System (“2P” Implant, Italy); Type: NR; Macrodesign: cylindrical; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 10–13.5 mm; Diameter: 4.1 mm; Position: implant shoulder 1 mm apical to the palatal marginal bone level | Healing screw placed at 6 months. Impressions for final restoration taken after 3 weeks, full zirconia crowns delivered 1 week later | CBCT Examiner calibration and blinding: blinding applied, measurements assessed by a a sigle experience examiner | Horizontal and vertical hard tissue dimensional changes, surgical intra-operative and post-operative complications Pain and discomfort (VAS) | Noflap-nograft surgery for post-extraction implants when sufficient buccal bone is present allows for a reduced and well-accepted surgical intervention that provides satisfactory results in terms of ‘jump space’ filling and dimensional bone preservation |

| Fettouh et al. (2023) [46] | Egypt (Cairo University) | 40 4 (20%) M, 16 (80%) F (Test) 9 (50%) M, 11 (60%) F (Control) Smokers: excluded | 37.4 ± 7.8 (Test) 35.5 ± 9.9 (Control) | 12 | NR | From premolar to premolar, thick gingival phenotype, intact but thin labial plate of bone extending 7 mm (≤1 mm) and intact palatal bone extending at least 6 mm apically | Flapless approach with DBBM | Brand: Bone System (“2P” Implant, Italy); Type: NR; Macrodesign: cylindrical; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 10–13.5 mm; Diameter: 4.1 mm; Position: implant shoulder 1 mm apical to the palatal marginal bone level | Immediate anatomical customized healing abutment Removable prosthesis with no interference with the soft tissue and no loading over the customized healing abutment. | CBCT Radiographic measurements of horizontal and vertical labial bone dimensions Examiner calibration and blinding: blinding applied | FMPS (%), FMBS (%), Pain VAS, Radiographic measurements of horizontal and vertical labial bone dimensions Horizontal labio-palatal bone width | Flapless IIP with or without DBBM in the labial gap is effective in preserving the alveolar bone dimension |

| Alloplastic graft | ||||||||||||

| Daif et al. (2013) [38] | Egypt (Cairo University) | 28 18 F, 10 M Smokers: NR | 34 years Age range: 22–48 years | 6 | Trauma, extensive dental caries, endodontic failure | Premolars (mandibular) | Porous beta-TCP | Brand: Zimmer (TSV); Type: bone-level; Macrodesign: tapered screw-vent; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length:11.5 or 13 mm; Diameter: 3.7 or 4.1 mm; Position: platform equicrestal or 1.5 mm subcrestal to the labial crest; labial gap ≥ 1.5 mm | Cover screw for 3 months Gingival former for 2 weeks | CT scan and 3D imaging Examiner calibration and blinding: NR | Bone density | Poor-phase multiporous beta-TPC seems to enhance the bone density when inserted into the gaps around immediate dental implants |

| Naji et al. (2021) [41] | Egypt (University of Mansoura) | 48 Flap with graft 5 M, 11 F Flap without graft 7 M, 9 F Flapless without graft 6 M, 10 F Smokers: excluded | 41.5 Age range: 28 to 55 years | 6 | NR | Premolars with intact socket walls, a horizontal gap > 2 mm in size, and a buccal bone plate thickness ≥ mm (maxillary) | 16 Flap without graft, 14 flap with graft, 15 flapless without graft Alloplastic nanocrystalline calcium sulphate bone graft covered with an absorbable collagen membrane | Brand: Neo Biotech; Type: NR; Macrodesign: two-piece tapered screw-type, threaded; Surface: SLA; Connection: NR; Length: 11.5 or 13 mm; Diameter: 3.7 mm; Position: implant shoulder 1 mm subcrestal to the buccal crest | Healing abutments | CBCT Examiner calibration and blinding: blinding applied | Pain (NRS) Horizontal hard tissue dimensions | Flapless without graft shows similar buccal bone preservation as flap with graft when the bone plate is intact and gap > 2 mm |

| Mixed graft | ||||||||||||

| El Ebiary et al. (2023) [43] | Egypt (Cairo University) | 24 3 M (25%) 9 F (75%) (Test) 6 M (50%) 6 F (50%) (Control) Smokers: NR | 20 to 50 years Mean (SD) 30.5 (9.6) Test 33.8 (12.5) Control | 6 | Non-restorable upper anterior teeth | Incisors and canines, with completely intact labial plate and interproximal bone levels (maxillary) | 50% DBBM and 50% autogenous bone | Brand: Implant Direct (Legacy); Type: NR; Macrodesign: tapered con buttress threads progressivi e tre cutting grooves; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 13–16 mm; Diameter: 3.7–4.2 mm; Position: traiettoria palatale; jumping gap 2–3 mm | 3D-printed screwed temporary restoration | Clinical measurement Examiner calibration and blinding: NR | PES | Grafting the jumping distance utilizing the Dual Zone Grafting technique helps achieve a better esthetic outcom |

| Connective Tissue Graft (CTG) | ||||||||||||

| Guglielmi et al. (2022) [42] | Italy (Milan, Dental Department of San Raffaele Hospital) | 30 17 F, 13 M Smokers: included smokers < 10 cig/day (requested to stop smoking before and after surgery) | 53.4 ± 12.2 years Age range: 34–74 years) | 6 | root fracture, caries, root resorption, or endodontic failure. | From second premolar to second premolar with intact buccal plate or presenting a maximum of 3 mm of buccal dehiscence; The distance between interdental bone crest and buccal bone crest ≤ 3 mm after tooth extraction. | CTG The buccal flap was coronally advanced to tightly adapt to the healing abutment. | Brand: Winsix (KE; BioSAF IN Srl); Type: NR; Macrodesign: NR; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: 9–15 mm; Diameter: 3.8 or 4.5 mm (endo-osseous 4.0/4.7 mm); Position: implant shoulder 1 mm apical to the buccal bone crest | healing abutments No implant-supported temporary restorations were used for the first 6 months. | Clinical measurements CBCT Soft tissue measurements (3D scanner) Examiner calibration and blinding: both calibration and blinding applied | KT width thickness of buccal bone wall (BC thick) S-IC, internal horizontal buccal gap dimension S-OC, horizontal buccal crest dimension R-B, vertical distance between the implant shoulder to top of the buccal bone crest. horizontal buccal bone resorption (HBBR) vertical buccal bone resorption (VBBR) osseous ridge width (ORW) Soft tissue contour Soft tissue thickness VAS score. | The adjunct of a CTG at the time of IIP, without bone grafting, does not influence vertical bone resorption. The use of CTG seems to reduce the horizontal changes of the alveolar ridge that occur. |

| Socket Shield Technique (SST) | ||||||||||||

| Venkatraman et al. (2023) [49] | India (New Delhi, Centre for Dental Education and Research) | 22 14 (64%) M, 8 (36%) F Smokers: excluded | 28.4 ± 4.7 years Age range: 18 to 45 years | 12 | Trauma, endodontic failure and unrestorable teeth | Incisor, with thick gingival phenotype and 3 to 5 mm of available bone apical to the existing root | SST | Brand: Adin (Touareg S); Type: NR; Macrodesign: NR; Surface: NR; Connection: NR; Length: NR; Diameter: NR; Position: implant placed 2 mm apical to the labial cortical bone level; palatal trajectory with 1–2 mm horizontal distance to the labial shield (SST) or to the labial wall (CT) | Immediate provisional screw-retained crowns fabricated on temporary abutments within 48 h of implant placement | Superimposition of 3D scans Clinical measurement Examiner calibration and blinding: blinding applied | Soft tissues dimensional changes PES | Volumetric changes in buccal soft tissue after IIP in the maxillary incisor area are inevitable, however such changes are reduced when using the SST |

- Alloplastic grafts

- Mixed grafts

- Connective tissue grafts (CTG)

| Author (Year) | Implant Survival (%) | Hard Tissue Measurements (mm, Mean ± SD) | Ridge Dimensions (mm, Mean ± SD) | Soft Tissue Measurements | KT (mm, Mean ± SD) | PES (mm, Mean ± SD) | % FMPS, FMBS (mm, Mean ± SD) | PPD (mm, Mean ± SD) | Pain (VAS) (Mean ± SD) | Post op Complications (n of Cases) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft | ||||||||||

| Cardaropoli et al. (2014) [17] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 96.15 | NR | Cast based measurements Ridge width: ΔT0–12 months: 1.92 ± 1.02 * Ridge height: ΔT0–12 months: −1.69 ± 1.72 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | NR | Cast based measurements Ridge width: ΔT0–12 months: 0.69 ± 0.68 * Ridge height: ΔT0–12 months: −0.58 ± 0.76 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Bittner et al. (2020) [47] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | NR | NR | Casts digital superimposition (measurements at 3 and 4 mm from the T0-FGM) Δhorizontal dimensional changes T0–12 months: 3 mm = −1.01 ± 0.45; 4 mm = −0.80 ± 0.33 Stent measurement Δvertical dimensional change T0–12 months: Mesial −0.9 ± 1.4; Distal −1.4 ± 1.1 (p = 0.02) * Buccal −1.3 ± 1.5 Δsoft tissue tickness (at 3, 4 and 8 mm from the T0–FGM) T0–12 months 3 mm: 0.35 mm 4 mm: 0.40 mm 8 mm: −0.10 mm | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | NR | NR | Casts digital superimposition (measurements at 3 and 4 mm from the T0-FGM) Δhorizontal dimensional changes T0–12 months: 3 mm = −0.84 ± 0.64; 4 mm = −0.64 ± 0.62 Stent measurement Δvertical dimensional change T0–12 months: Mesial −0.6 ± 1.2 Distal −0.4 ± 1.2 * Buccal −0.9 ± 1.2 Δsoft tissue tickness (at 3, 4 and 8 mm from the T0-FGM) T0–12 months 3 mm: 0.70 mm 4 mm: 0.80 mm 8 mm: 0.50 mm | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | |

| Mastrangelo et al. (2018) [44] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 98.2 | PA xrays Δmarginal bone level (T0–T36): –0.28 ± 0.304 Mesial ΔT0–T36: −0.32 ± 1.13 * Distal ΔT0–T36: −0.17 ± 1.09 * | NR | NR | NR | T36: 9.70 ± 2.02 * | ΔT0–T36: 1.40 ± 1.619 | NR | NR | Poor surgical complications in both gropus (17 patients in total) At 36 months: inflammation in 56 patients, 2 peri-implantitis (no distinctions between groups) | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 98.3 | PA xrays Delta marginal bone level (T0–T36): −0.25 ± 0.362 Mesial ΔT0–T36: −0.16 ± 0.66 * Distal ΔT0–T36: −0.24 ± 0.73 * | NR | NR | NR | T36: 8.14 ± 1.90 * | ΔT0–T36: 1.69 ± 1.345 | NR | NR | ||

| Jacobs et al. (2020) [45] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 97% (overall) | CBCT measurements Vertical CEJ/Crown margin to crest T0: 2.95 10 months: 2.26 ± 0.77 Horizontal 1 mm subcrestal T0: 0.96 10 months: 1.47 ± 0.85 Midimplant T0: 0.84 10 months: 1.30 ± 1.28 1 mm from apex T0: 1.13 10 months: 1.90 ± 2.07 | NR | Clinical measurement Δvertical dimensional change, T0–T10 months Mesial papilla 0.57 ± 0.59 Distal papilla 0.79 ± 0.75 Midfacial aspect 0.92 ± 0.67 | NR | 10 months: 8.2 ± 1.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 97% (overall) | CBCT measurements Vertical CEJ/Crown margin to crest T0: 3.46 10 months: 2.02 ± 1.04 Horizontal 1 mm subcrestal T0: 1.02 10 months: 1.63 ± 0.71 Midimplant T0: 0.99 10 months: 1.83 ± 1.17 1 mm from apex T0: 0.77 10 months: 2.54 ± 2.01 | NR | Clinical measurement Δvertical dimensional change Mesial papilla 0.33 ± 0.46 Distal papilla 0.49 ± 0.62 Midfacial aspect 0.94 ± 1.13 | NR | 10 months: 8.3 ± 2.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Girlanda et al. (2019) [39] | Control Group | |||||||||

| NR | CBCT measurements Buccolingual measurement 1 mm apical to crest Baseline 6.75 ± 0.27; 6 months 6.07 ± 0.24 * 3 mm apical to crest Baseline 6.83 ± 0.28; 6 months 6.15 ± 0.24 * 5 mm apical to crest Baseline 6.86 ± 0.27; 6 months 6.18 ± 0.24 * Buccal GAP Baseline: 2.45 ± 0.52; 6 months 2.17 ± 0.46 | NR | Clinical measuremen, distance from the reference point on the stent to the gingival margin Vertical dimensional change Mesial Baseline 8.55 ± 1.57; 6 months 9.55 ± 1.57 * Distal Baseline 8.36 ± 1.57; 6 months 9.35 ± 1.43 * Buccal Baseline 10.82 ± 1.54; 6 months 11.82 ± 1.54 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| NR | CBCT measurements Buccolingual measurement 1 mm apical to crest Baseline 7.04 ± 0.49; 6 months 6.57 ± 0.45 * 3 mm apical to crest Baseline 7.12 ± 0.49; 6 months 6.65 ± 0.45 * 5 mm apical to crest Baseline 7.15 ± 0.49; 6 months 6.69 ± 0.45 * Buccal GAP Baseline 2.55 ± 0.52; 6 months 2.29 ± 0.48 | NR | Clinical measuremen, stent Vertical dimensional change Mesial Baseline 8.45 ± 1.81; 6 months 8.36 ± 1.75 * Distal Baseline 8.45 ± 1.75; 6 months 8.35 ± 1.54 * Buccal Baseline 11.82 ± 2.32; 6 months 11.82 ± 2.32 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Grassi et al. (2019) [40] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal bone level changes A-EA Flap-nograft: ΔT0–T6 = −0.1 (1.2) Noflap-nograft: ΔT0–T6 = −0.3 (1.5) M-EM Flap-nograft: ΔT0–T6 = −1.2 (0.8) Noflap-nograft: ΔT0–T6 = −0.8 (0.8) B-EB Flap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −1.1 (0.9) * Noflap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −1.0 (1.1) B-IB Flap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −1.8 (0.6) Noflap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −2.0 (0.9) Vertical bone level changes C-P Flap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −0.2 (0.6) Noflap-nograft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6= −0.1 (0.6) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Flap-nograft 4 h = 45.3 ± 10.3 * 24 h = 75.1 ± 9.8 * 3 days = 29.8 ± 10.8 * 7 days = 9.3 ± 4.9 * Noflap-nograft 4 h = 35.2 ± 13.4 * 24 h = 53.2 ± 12.1 * 3 days = 18.2 ± 11.3 * 7 days = 5.4 ± 3.8 * | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal bone level changes A-EA Flap-graft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −0.2 (1.1) M-EM Flap-graft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −0.4 (0.7) B-EB Flap-graft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −0.4 (0.8)* B-IB Flap-graft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −2.3 (0.8) Vertical bone level changes C-P Flap-graft: post-surgery ΔT0–T6 = −0.3 (0.7) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Flap-graft 4 h = 49.5 ± 15.2 * 24 h = 71.4 ± 11.2 * 3 days = 31.6 ± 9.8 * 7 days = 10.2 ± 5.3 * | NR | |

| Fettouh et al. (2023) [46] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal labial bone thickness (at three levels below the labial bone crest) ΔT0–1 year: 0 mm: 2.1 ± 1.5 2 mm: 1.9 ± 1.5 5 mm: 1.6 ± 1.6 ΔLabio-palatal bone width T0-1 year 0 mm: −0.7 ± 2.05 2 mm: −0.7 ± 2.05 5 mm: −0.8 ± 2.19 Vertical Crestal bone level change, ΔT0–1year: −1.2 ± 0.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | FMPS (%) Baseline: 17.1 ± 2.7 1 year: 11.8 ± 3.4 FMBS (%) Baseline: 9.6 ± 2.1 1 year: 6.6 ± 2.6 | NR | VAS 24 h: 61.8 ± 9.5 3 days: 41.8 ± 6.3 7 days: 5.8 ± 3.5 | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal labial bone plate thickness (at three levels below the labial bone crest) Delta Baseline—1 year: 0 mm: 1.7 ± 1.10 2 mm: 1.7 ± 1.20 5 mm: 1.7 ± 1.30 Labio-palatal bone width ΔT0–1year (0 mm):−0.6 ± 0.5 (2 mm): −0.6 ± 0.3 (5 mm): −0.5 ± 0.4 Vertical Crestal bone level change, ΔT0–1year: −0.1 ± 1.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | FMPS (%) Baseline: 16.3 ± 1.9 1 year: 11.9 ± 1.9 FMBS (%) Baseline: 9.8 ± 2.0 1 year: 7.4 ± 2.0 | NR | VAS 24 h: 60 ± 10.9 3 days: 39.3 ± 7.8 7 days: 5.8 ± 3.5 | NR | |

| Alloplastic graft | ||||||||||

| Daif et al. (2013) [38] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | Bone density (Hounsfield units) CT scan 6 months: 1245 ± 165 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | Bone density (Hounsfield units) CT scan 6 months: 1490 ± 358 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 (Mild soft tissue infection) | |

| Naji et al. (2021) [41] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal dimension of buccal alveolar bone Flap without graft ΔT0–T6 = 0.91 ± 0.54 * Flapless without graft ΔT0–T6 = 0.24 ± 0.11 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 days (NRS) Flap without graft: 3.71 ± 0.76 * Flapless without graft: 0.71 ± 0.49 * | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal dimension of buccal alveolar bone Flap with graft ΔT0–T6 = 0.37 ± 0.09 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 days (NRS) Flap with graft: 5.14 ± 0.69 * | NR | |

| Mixed graft | ||||||||||

| El Ebiary et al. (2023) [43] | Control Group | |||||||||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Immediate post-operative: 11.75 ± 1.71 6 months: 11.17 ± 1.53 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Immediate post-operative: 11.58 ± 1.16 6 months: 12.42 ± 1.44 * | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Connective Tissue Graft(CTG) | ||||||||||

| Guglielmi et al. (2022) [42] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal Bone Dimensions, HBBR 1–5 mm below the most coronal point of the buccal osseous ridge) HBBR 1: −1.59 ± 0.54 mm * HBBR 2: −1.13 ± 0.40 mm * HBBR 3: −0.96 ± 0.37 mm * HBBR 4: −0.79 ± 0.34 mm * HBBR 5: −0.78 ± 0.34 mm * Vertical Bone Dimensions VBBR: −0.66 (0.75) mm | CBCT measurements Osseous ridge width (1–5 mm below the most coronal point of the buccal osseous ridge) ORR 1 (mm): −2.09 ± 0.53 * ORR 2 (mm): −1.66 ± 0.79 ORR 3 (mm): −1.45 ± 0.76 ORR 4 (mm): −1.13 ± 0.59 ORR 5 (mm): −1.06 ± 0.49 | 3D scanner measurements Buccal soft tissue contour changes (ΔSTC baseline-6 months) (at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mm apical to the baseline gingival margin) STC 1: −1.94 ± 0.83 * STC 2: −1.85 ± 0.78 * STC 3: −1.57 ± 0.63 * STC 4: −1.30 ± 0.64 * STC 5: −1.08 ± 0.80 * STC Volume (mm3;): 0.16 ± 0.42 * Soft tissue thickness (ΔSTT baseline-6 months) (at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mm respectively apical to the baseline and 6 M gingival margin) STT 1: −0.16 ± 0.61 * STT 2: 0.12 ± 0.70 * STT 3: 0.81 ± 0.96 * STT 4: 0.88 ± 0.88 * STT 5: 0.11 ± 0.76 * | KTW, 6 months Mean KTW: 3.64 ± 1.29 mm Gain in KTW: 0.14 ± 1.28 mm | NR | NR | NR | VAS, 1 week 1.07 ± 0.70 * | 0 | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | CBCT measurements Horizontal Bone Dimensions, HBBR 1–5 mm below the most coronal point of the buccal osseous ridge) HBBR 1: −1.36 ± 1.17 mm HBBR 2: −0.89 ± 0.70 mm HBBR 3: −0.73 ± 0.53 mm HBBR 4: −0.69 ± 0.39 mm HBBR 5: −0.66 ± 0.45 mm Vertical Bone Dimensions VBBR: −0.66 (0.53) mm | CBCT measurements Osseous ridge width (1–5 mm below the most coronal point of the buccal osseous ridge) ORR 1 (mm): −1.16 ± 0.50 * ORR 2 (mm): −1.03 ± 0.66 ORR 3 (mm): −0.95 ± 0.60 ORR 4 (mm): −1.05 ± 0.68 ORR 5 (mm): −0.94 ± 0.56 | 3D scanner measurements Buccal soft tissue contour changes (ΔSTC baseline-6 months) (at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mm apical to the baseline gingival margin) STC 1: −0.32 ± 0.97 * STC 2: −0.04 ± 0.74 * STC 3: 0.11 ± 0.66 * STC 4: 0.18 ± 0.70 * STC 5: 0.13 ± 0.81 * STC Volume (mm3): 6.76 ± 8.94 * Soft tissue thickness (ΔSTT baseline-6 months) (at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mm respectively apical to the baseline and 6 M gingival margin) STT 1: 1.47 ± 1.08 * STT 2: 2.04 ± 1.18 * STT 3: 2.42 ± 1.63 * STT 4: 2.07 ± 1.22 * STT 5: 1.33 ± 1.17 * | KTW, 6 months Mean KTW: 4.53 ± 1.36 mm Gain in KTW: 0.60 ± 1.71 mm | NR | NR | NR | VAS, 1 week: 2.73 ± 1.62 * | 0 | |

| Socket Shield Technique(SST) | ||||||||||

| Venkatraman et al. (2023) [49] | Control Group | |||||||||

| 100 | NR | NR | 3D scanner measurements, soft tissue volumentric change T0–T12 months: −0.643 ± 0.35 mm * | NR | T0: 8.91 ± 1.30 T12: 11.18 ± 1.40 * | NR | NR | NR | 0 | |

| Test Group | ||||||||||

| 100 | NR | NR | 3D scanner measurements, soft tissue volumentric change T0–T12 months: −0.1520 ± 0.86 mm * | NR | T0: 9.73 ± 1.27 T12: 12.91 ± 0.83 * | NR | NR | NR | 0 | |

- Socket shield technique (SST)

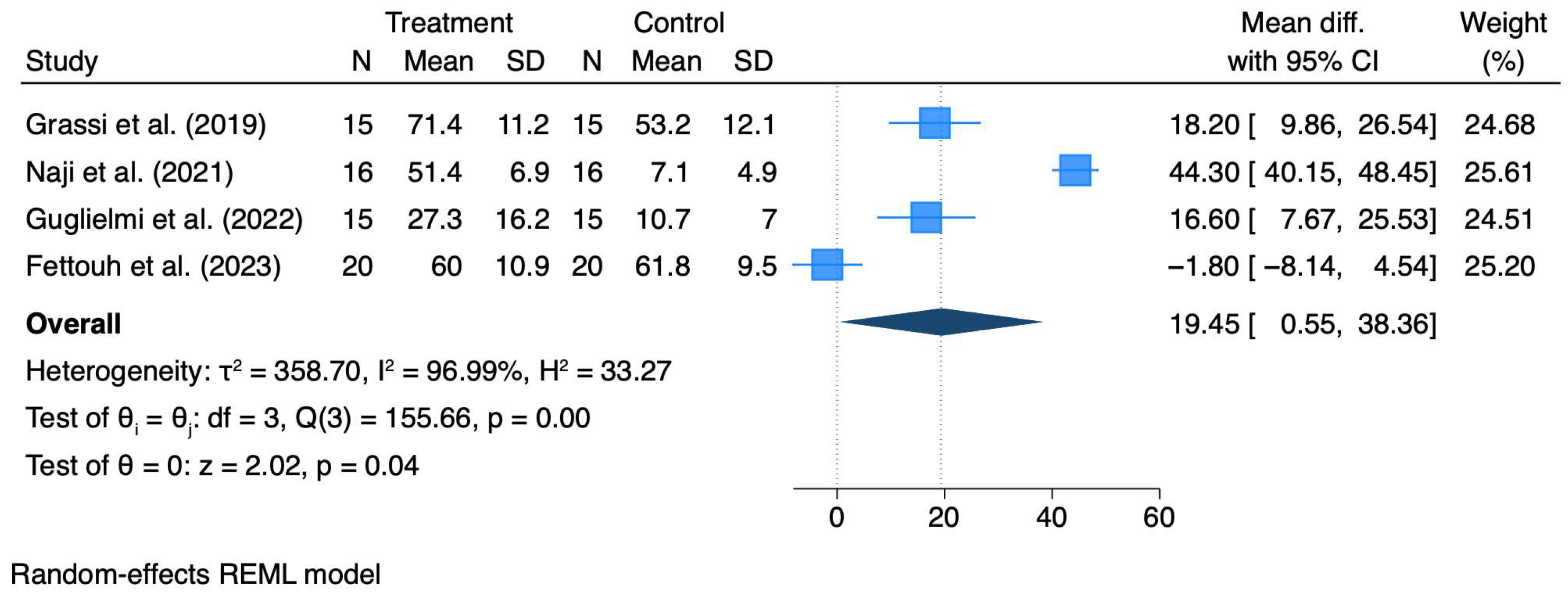

3.3. Quantitative Synthesis

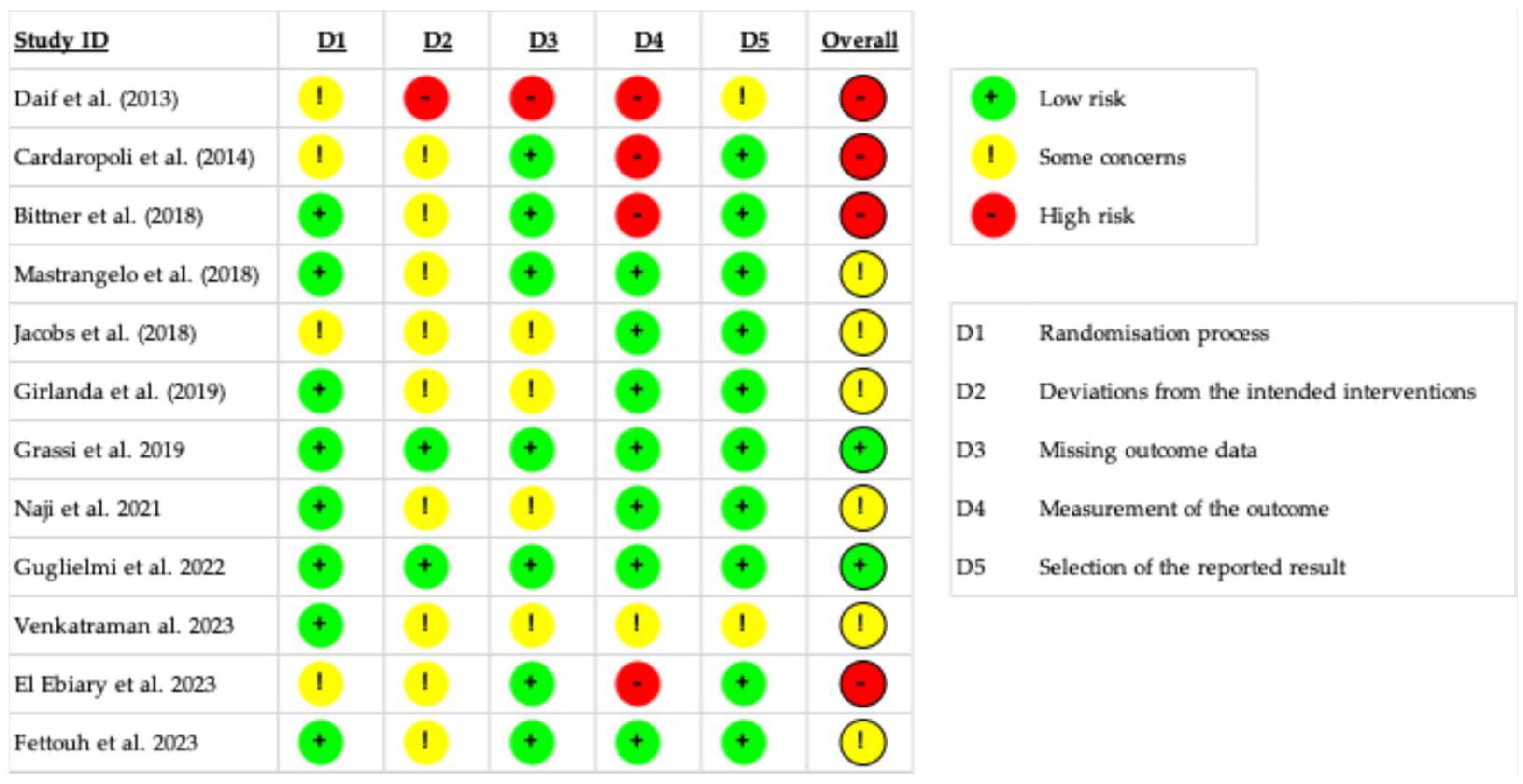

3.4. Risk of Bias Quality Assessment

3.5. Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.6. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lang, N.P.; Pun, L.; Lau, K.Y.; Li, K.Y.; Wong, M.C.M. A systematic review on survival and success rates of implants placed immediately into fresh extraction sockets after at least 1 year. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S5), 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoletti, F.; Sanz, M. Immediate implants at fresh extraction sockets: From myth to reality. Periodontol. 2000 2014, 66, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Buser, D. Esthetic outcomes following immediate and early implant placement in the anterior maxilla—A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.D.J.; Chen, S.T. Esthetic outcomes of immediate implant placements. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2008, 19, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; Wennström, J.L.; Lindhe, J. Modeling of the buccal and lingual bone walls of fresh extraction sites following implant installation. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignoletti, F.; Discepoli, N.; Müller, A.; De Sanctis, M.; Muñoz, F.; Sanz, M. Bone modelling at fresh extraction sockets: Immediate implant placement versus spontaneous healing. An experimental study in the beagle dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.L.; Wong, T.L.T.; Wong, M.C.M.; Lang, N.P. A systematic review of post-extractional alveolar hard and soft tissue dimensional changes in humans. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S5), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merheb, J.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W. Critical buccal bone dimensions along implants. Periodontol. 2000 2014, 66, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discepoli, N.; Vignoletti, F.; Laino, L.; de Sanctis, M.; Muñoz, F.; Sanz, M. Fresh extraction socket: Spontaneous healing vs. immediate implant placement. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticelli, D.; Berglundh, T.; Lindhe, J. Hard-tissue alterations following immediate implant placement in extraction sites. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2004, 31, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discepoli, N.; Vignoletti, F.; Laino, L.; De Sanctis, M.; Muñoz, F.; Sanz, M. Early healing of the alveolar process after tooth extraction: An experimental study in the beagle dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.G.; Sukekava, F.; Wennström, J.L.; Lindhe, J. Ridge alterations following implant placement in fresh extraction sockets: An experimental study in the dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, V.; Araújo, M.G.; Buser, D. Clinical relevance of dimensional bone and soft tissue alterations post-extraction in esthetic sites. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementini, M.; Agostinelli, A.; Castelluzzo, W.; Cugnata, F.; Vignoletti, F.; De Sanctis, M. The effect of immediate implant placement on alveolar ridge preservation compared to spontaneous healing after tooth extraction: Radiographic results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementini, M.; Castelluzzo, W.; Ciaravino, V.; Agostinelli, A.; Vignoletti, F.; Ambrosi, A.; De Sanctis, M. The effect of immediate implant placement on alveolar ridge preservation compared to spontaneous healing after tooth extraction: Soft tissue findings from a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; Lindhe, J. Ridge preservation with the use of Bio-Oss collagen: A 6-month study in the dog. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardaropoli, D.; Gaveglio, L.; Gherlone, E.; Cardaropoli, G. Soft tissue contour changes at immediate implants: A randomized controlled clinical study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2014, 34, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Lindhe, J.; Alcaraz, J.; Sanz-Sanchez, I.; Cecchinato, D. The effect of placing a bone replacement graft in the gap at immediately placed implants: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hürzeler, M.B.; Zuhr, O.; Schupbach, P.; Rebele, S.F.; Emmanouilidis, N.; Fickl, S. The socket-shield technique: A proof-of-principle report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.; Chen, S.; Martin, W.; Levine, R.; Buser, D. Consensus statements and recommended clinical procedures regarding optimizing esthetic outcomes in implant dentistry. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rouck, T.; Collys, K.; Wyn, I.; Cosyn, J. Instant provisionalization of immediate single-tooth implants is essential to optimize esthetic treatment outcome. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyssens, L.; De Lat, L.; Cosyn, J. Immediate implant placement with or without connective tissue graft: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Shi, J.Y.; Buti, J.; Lai, H.C.; Tonetti, M.S. Buccal bone thickness and mid-facial soft tissue recession after various surgical approaches for immediate implant placement: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of controlled trials. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, J.; Yusuf, N.; El-Khadem, A.; Scholten, R.J.P.M.; Jenniskens, K. Efficacy of bone-substitute materials use in immediate dental implant placement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2021, 23, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanauskaite, A.; Sadilina, S.; Schwarz, F.; Cafferata, E.A.; Strauss, F.J.; Thoma, D.S. Soft-tissue volume augmentation during early, delayed, and late dental implant therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis on professionally determined esthetics and self-reported patient satisfaction on esthetics. Periodontol. 2000 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, F.; Montero, E.; Laleman, I.; de Albornoz, A.C.; Yousfi, H.; Sanz-Sánchez, I. Esthetic and patient-reported outcomes in immediate implants with adjunctive surgical procedures to increase soft tissue thickness/height: A systematic review. Periodontol. 2000 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; Clark, J.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Brennan, S.; Akl, E.A.; Hultcrantz, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Xia, J.; Davoli, M.; Rojas, M.X.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Flottorp, S.; et al. The development methods of official GRADE articles and requirements for claiming the use of GRADE—A statement by the GRADE guidance group. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 159, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; Debeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. The Comparison of Percentages in Matched Samples. Biometrika 1950, 37, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses Testing for heterogeneity. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daif, E.T. Effect of a multiporous beta-tricalicum phosphate on bone density around dental implants inserted into fresh extraction sockets. J. Oral Implant. 2013, 39, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girlanda, F.F.; Feng, H.S.; Corrêa, M.G.; Casati, M.Z.; Pimentel, S.P.; Ribeiro, F.V.; Cirano, F.R. Deproteinized bovine bone derived with collagen improves soft and bone tissue outcomes in flapless immediate implant approach and immediate provisionalization: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 3885–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, F.R.; Grassi, R.; Rapone, B.; Alemanno, G.; Balena, A.; Kalemaj, Z. Dimensional changes of buccal bone plate in immediate implants inserted through open flap, open flap and bone grafting and flapless techniques: A cone-beam computed tomography randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, B.M.; Abdelsameaa, S.S.; Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Said Ahmed, W.M. Immediate dental implant placement with a horizontal gap more than two millimetres: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, D.; Di Domenico, G.L.; Aroca, S.; Vignoletti, F.; Ciaravino, V.; Donghia, R.; de Sanctis, M. Soft and hard tissue changes after immediate implant placement with or without a sub-epithelial connective tissue graft: Results from a 6-month pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ebiary, S.O.; Atef, M.; Abdelaziz, M.S.; Khashaba, M. Guided immediate implant with and without using a mixture of autogenous and xeno bone grafts in the dental esthetic zone. A randomized clinical trial. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, F.; Gastaldi, G.; Vinci, R.; Troiano, G.; Tettamanti, L.; Gherlone, E.; Lo Muzio, L. Immediate Postextractive Implants With and Without Bone Graft: 3-year Follow-up Results From a Multicenter Controlled Randomized Trial. Implant. Dent. 2018, 27, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.; Zadeh, H.; De Kok, I.; Cooper, L. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating Grafting the Facial Gap at Immediately Placed Implants. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettouh, A.I.A.; Ghallab, N.A.; Ghaffar, K.A.; Mina, N.A.; Abdelmalak, M.S.; Abdelrahman, A.A.G.; Shemais, N.M. Bone dimensional changes after flapless immediate implant placement with and without bone grafting: Randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, N.; Planzos, L.; Volchonok, A.; Tarnow, D.; Schulze-Späte, U. Evaluation of Horizontal and Vertical Buccal Ridge Dimensional Changes After Immediate Implant Placement and Immediate Temporization With and Without Bone Augmentation Procedures: Short-Term, 1-Year Results A. Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Quirynen, M. Dental cone beam computed tomography: Justification for use in planning oral implant placement. Periodontol. 2000 2014, 66, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, N.; Jain, V.; Nanda, A.; Koli, D. Comparison of Soft Tissue Volumetric Changes and Pink Esthetics After Immediate Implant Placement with Socket Shield and Conventional Techniques: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 36, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosyn, J.; De Lat, L.; Seyssens, L.; Doornewaard, R.; Deschepper, E.; Vervaeke, S. The effectiveness of immediate implant placement for single tooth replacement compared to delayed implant placement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46 (Suppl. S21), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happe, A.; Schmidt, A.; Neugebauer, J. Peri-implant soft-tissue esthetic outcome after immediate implant placement in conjunction with xenogeneic acellular dermal matrix or connective tissue graft: A randomized controlled clinical study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happe, A.; Debring, L.; Schmidt, A.; Fehmer, V.; Neugebauer, J. Immediate Implant Placement in Conjunction with Acellular Dermal Matrix or Connective Tissue Graft: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Volumetric Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2022, 42, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, J.; Seyssens, L.; Christiaens, V.; Cosyn, J. Immediate implant placement with or without immediate provisionalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.L.; George, F.; Wang, I.C.; Suárez López del Amo, F.; Kinney, J.; Wang, H.L. A randomized controlled trial to compare aesthetic outcomes of immediately placed implants with and without immediate provisionalization. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegenthaler, M.; Strauss, F.J.; Gamper, F.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Jung, R.E.; Thoma, D.S. Anterior implant restorations with a convex emergence profile increase the frequency of recession: 12-month results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürhauser, R.; Florescu, D.; Benesch, T.; Haas, R.; Mailath, G.; Watzek, G. Evaluation of soft tissue around single-tooth implant crowns: The pink esthetic score. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belser, U.C.; Grütter, L.; Vailati, F.; Bornstein, M.M.; Weber, H.; Buser, D. Outcome evaluation of early placed maxillary anterior single-tooth implants using objective esthetic criteria: A cross-sectional, retrospective study in 45 patients with a 2- to 4-year follow-up using pink and white esthetic scores. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | № of Participants (Studies) | Effect (95% CI or Mean ± SD) | Quality of Evidence (GRADE) | Summary/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implant survival rate | 484 (12 RCTs) | 96–100% in both groups; no significant differences | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁◯ | Stable survival across all biomaterials; downgraded for indirectness (short follow-up, small samples). |

| Clinically assessed esthetic outcomes (PES/WES) | 164 (4 RCTs) | PES improved by +1.0–1.7 points (Mastrangelo 2018 + 1.56; El Ebiary 2023 + 1.25; SST + 1.7) | Low ⨁⨁◯◯ | Significant in some studies but inconsistent; non-standardized scoring; esthetic benefit possible but uncertain. |

| Patient-reported esthetic outcomes (PROMs) | — (none with validated PROMs) | Not reported | Very Low ⨁◯◯◯ | No validated PROMs; serious indirectness and reporting bias. |

| Hard tissue dimensional changes | 340 (8 RCTs) | Xenografts: Δridge width −0.7 mm vs. −1.9 mm (control); CTG: ΔHBBR −1.36 mm vs. −1.59 mm | Low ⨁⨁◯◯ | Moderate ridge preservation with grafts; downgraded for heterogeneity and small samples. |

| Soft tissue dimensional changes/contour stability | 212 (5 RCTs) | CTG: Δcontour −0.3 mm vs. −1.9 mm (control); SST: Δvolume −0.15 mm vs. −0.64 mm (control) | Low ⨁⨁◯◯ | Consistent trend toward contour improvement; limited sample sizes and variable methodology. |

| Keratinized tissue width (KTW) | 60 (2 RCTs) | CTG: KTW 4.53 ± 1.36 mm vs. 3.64 ± 1.29 mm (control); gain ≈ +0.6 mm | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁◯ | KTW gain limited to CTG studies; reliable CBCT/3D measurements but small sample. |

| Post-operative morbidity (pain, VAS/NRS) | 150 (4 RCTs, meta-analysis) | MD = +19.45 mm VAS (95% CI 0.55–38.36; p = 0.04); e.g., Grassi 2019 24 h: 71.4 ± 11.2 vs. 53.2 ± 12.1 mm | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁◯ | Adjunctive procedures increase short-term pain; heterogeneity high (I2 ≈ 97%) but direction consistent. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Rubertis, I.; Fratini, A.; Carra, M.C.; Annunziata, M.; Discepoli, N. Adjunctive Procedures in Immediate Implant Placement: Necessity or Option? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 5427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235427

De Rubertis I, Fratini A, Carra MC, Annunziata M, Discepoli N. Adjunctive Procedures in Immediate Implant Placement: Necessity or Option? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235427

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Rubertis, Isabella, Adriano Fratini, Maria Clotilde Carra, Marco Annunziata, and Nicola Discepoli. 2025. "Adjunctive Procedures in Immediate Implant Placement: Necessity or Option? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Materials 18, no. 23: 5427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235427

APA StyleDe Rubertis, I., Fratini, A., Carra, M. C., Annunziata, M., & Discepoli, N. (2025). Adjunctive Procedures in Immediate Implant Placement: Necessity or Option? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Materials, 18(23), 5427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235427