The 3D Printing of Flexible Materials: Technologies, Materials, and Challenges

Abstract

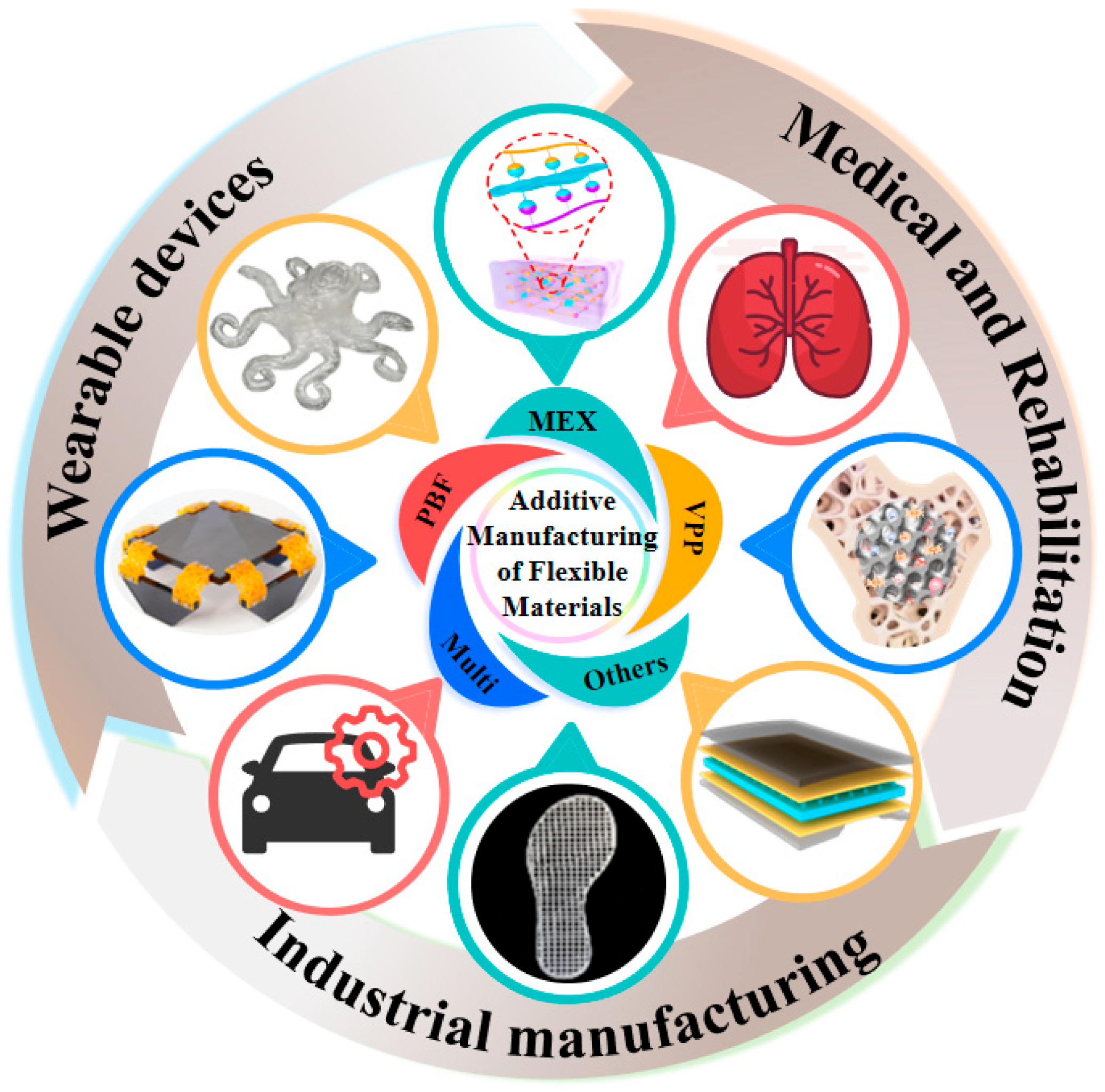

1. Introduction

2. Advances in 3D Printing of Flexible Materials

2.1. 3D Printing Technologies

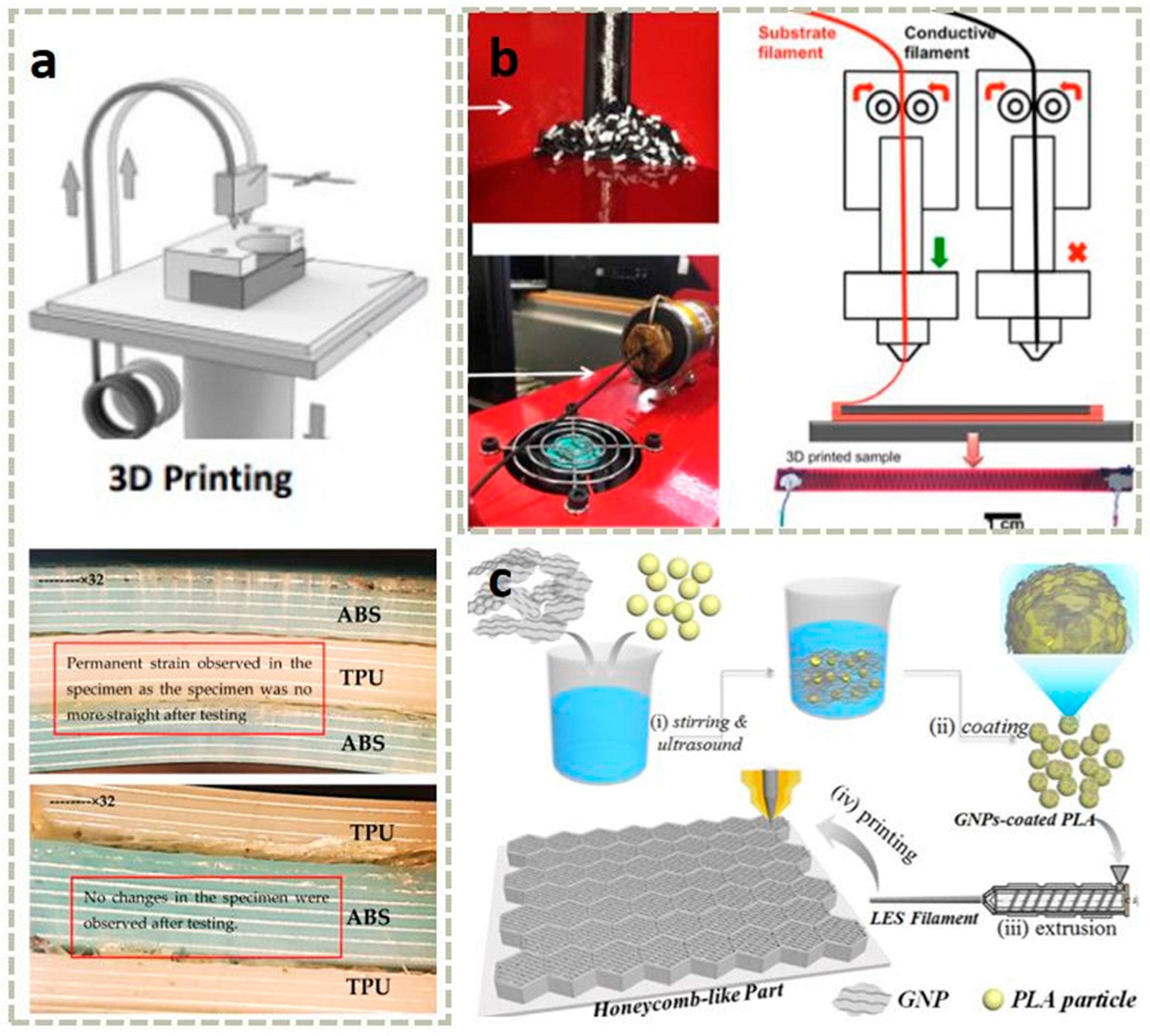

2.1.1. Material Extrusion

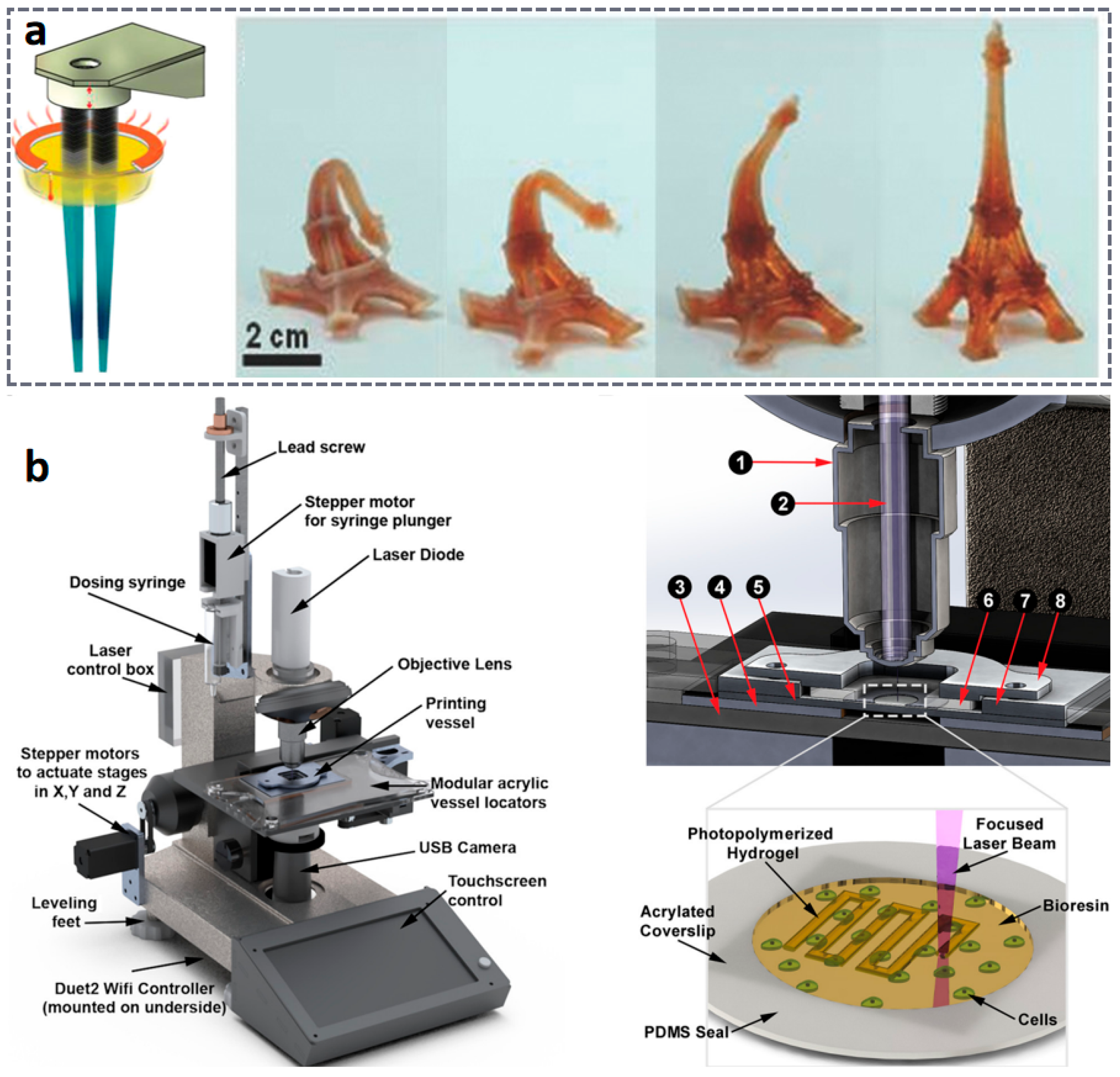

2.1.2. Vat Polymerization

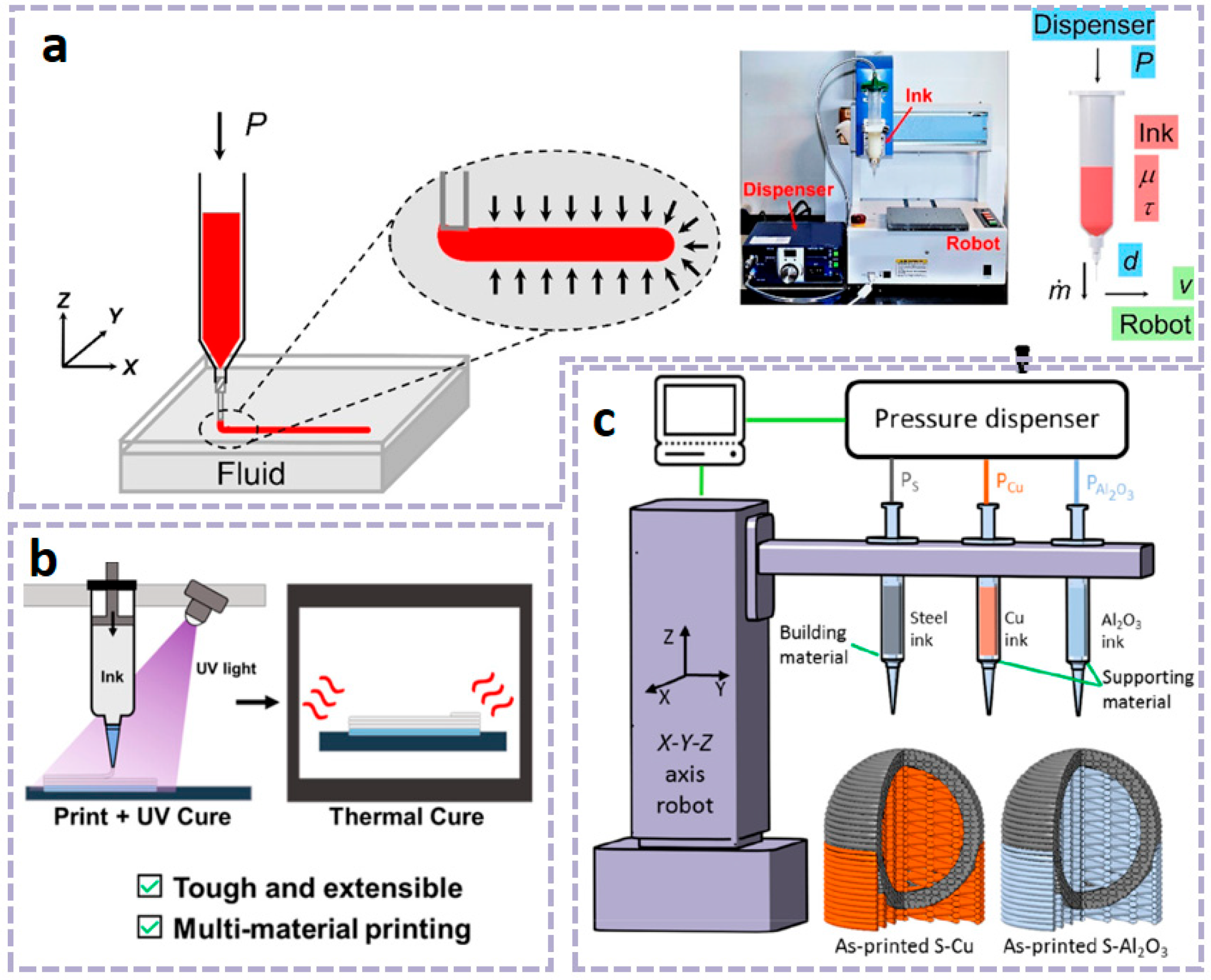

2.1.3. Other 3D Printing Technologies

2.1.4. Multi-Technology

2.2. Flexible Materials

2.2.1. Thermoplastic Flexible Materials

2.2.2. Light-Cured Flexible Resin Material

2.2.3. Hydrogel-Based Flexible Materials

2.2.4. Flexible Composites

- Elastomer-based composites

- Hydrogel composites

- Light-cured flexible resin composites

3. Challenges Towards 3D Printed Flexible Materials

3.1. Challenges Towards Material Extrusion 3D Printed Flexible Materials

3.2. Challenges Towards Vat Polymerization 3D Printed Flexible Materials

- (i)

- Material Innovation Optimization

- (ii)

- Multi-Material System Development

- (iii)

- Process Optimization and Intelligent Post-Processing

3.3. Challenges Towards Other 3D Printed Flexible Materials

3.4. Challenges Towards Economic Cost

4. Summary

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| TPE | Thermoplastic elastomers |

| VPP | Vat Polymerization |

| BJT | Binder Jetting |

| PLA | Poly Lactic Acid |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| HME | Hot-melt extrusion |

| LCDs | Liquid crystal displays |

| DMD | Digital micromirror devices |

| BCC | Body-centered cubic |

| TPA | Thermoplastic polyamide elastomers |

| PEGDA | Polyethylene glycol |

| PNIPAM | poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) |

| NAM | N-isopropylacrylamide |

| HEMA | Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| DES | Diethyl siloxane |

| NFC | Near-field communication |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| PPY | Polypyrrole |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| TPU | Thermoplastic polyurethane |

| PBF | Powder Bed Fusion |

| MEX | Material Extrusion |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| CNFs | Cellulose nanofibrils |

| SIFS | Solidification |

| MWCNT | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| TPC | Thermoplastic copolyester |

| PEBA | Polyether Block Amide |

| GelMA | Methylacryloylated gelatin |

| CNC | Cellulose nanocrystals |

| TFEA | 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl acrylate |

| AA | Acrylic acid |

| AFE | Automatic fiber embedding |

| HA | Hydroxyapatite |

| UA | Acrylic urethane |

| IPNs | Interpenetrating polymer networks |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Bose, S.; Ke, D.; Sahasrabudhe, H.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Additive Manufacturing of Biomaterials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 93, 45–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, S.F.S.; Gharehkhani, S.; Mehrali, M.; Yarmand, H.; Metselaar, H.S.C.; Kadri, N.A.; Abu Osman, N.A. A review on powder-based additive manufacturing for tissue engineering: Selective laser sintering and inkjet 3D printing. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 033502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Yao, F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Sewvandi, G.A.; Yang, D.; Hu, D. Additive Manufacturing of Piezoelectric Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2005141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramian, A.; Razavi, N.; Sadeghian, Z.; Berto, F. A review of additive manufacturing of cermets. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 33, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.W.; Choong, Y.Y.C.; Kuo, C.N.; Low, H.Y.; Chua, C.K. 3D printed electronics: Processes, materials and future trends. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 127, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Han, W.; Lin, H.; Li, R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W. 3D Printed Flexible Strain Sensors: From Printing to Devices and Signals. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Singh, R. Material issues in additive manufacturing: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 25, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.Y.; Noroozi, R.; Hossain, M.; Shi, H.H.; Tariq, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Umer, R. Additive manufacturing of sustainable biomaterials for biomedical applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, J.W.; Idacavage, M.J. 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Pang, H.; Chen, Y. Functional PDMS Elastomers: Bulk Composites, Surface Engineering, and Precision Fabrication. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2304506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, O.; Shepherd, T.; Moroney, C.; Foster, L.; Venkatraman, P.D.; Winwood, K.; Allen, T.; Alderson, A. Review of Auxetic Materials for Sports Applications: Expanding Options in Comfort and Protection. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, T.J.; Pikul, J.; Shepherd, R.F. 3D printing of soft robotic systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, R.L.; Lewis, J.A. Printing soft matter in three dimensions. Nature 2016, 540, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniasadi, H.; Abidnejad, R.; Fazeli, M.; Lipponen, J.; Niskanen, J.; Kontturi, E.; Seppala, J.; Rojas, O.J. Innovations in hydrogel-based manufacturing: A comprehensive review of direct ink writing technique for biomedical applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 324, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Du, C.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W.; Ren, T.; Sun, Z.; Lu, Y.; Nie, Z.; et al. Approaching intrinsic dynamics of MXenes hybrid hydrogel for 3D printed multimodal intelligent devices with ultrahigh superelasticity and temperature sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.W.; Lee, S.J.; Ko, I.K.; Kengla, C.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shan, Y.; Chen, J.; Su, R.; Zhao, L.; He, R.; Li, Y. Piezoelectricity Promotes 3D-Printed BTO/β-TCP Composite Scaffolds with Excellent Osteogenic Performance. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausladen, M.M.; Gorbea, G.D.; Francis, L.F.; Ellison, C.J. UV-Assisted Direct Ink Writing of Dual-Cure Polyurethanes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Cheng, J.; Ye, H.; Sakhaei, A.H.; Yuan, C.; Rao, P.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; et al. Mechanically Robust and UV-Curable Shape-Memory Polymers for Digital Light Processing Based 4D Printing. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lin, K.; Chen, L.; Yang, D.; Ge, Q.; Wang, Z.; Peng, S.; Guo, Q.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Self-Powered Wireless Flexible Ionogel Wearable Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 14768–14776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, E.; Cheng, C.; Zhu, J.; Yang, P.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Panahi Sarmad, M.; et al. Direct Ink Writing 3D Printing Elastomeric Polyurethane Aided by Cellulose Nanofibrils. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 28142–28153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh Alghamdi, S.; John, S.; Roy Choudhury, N.; Dutta, N.K. Additive Manufacturing of Polymer Materials: Progress, Promise and Challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, Z.; Mahmoudpour, M.; Rahimpour, E.; Jouyban, A. Nanomaterial based PVA nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical sensing: Advances toward designing the ideal flexible/wearable nanoprobes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 305, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; Cheng, L.; Huo, M.; Yin, J.; Hao, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, P.; et al. Additive manufacturing of structural materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 145, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Tai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, W.; et al. Recent advances in nanofiber-based flexible transparent electrodes. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 032005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, P.; Wang, H.; Qin, G.; Hang, R.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Yao, X. DLP-printable hydrogel with integrated tear resistance and low hysteresis for flexible strain sensingclick to copy article link. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 10987–10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Meng, J.; Bao, X.; Huang, Y.; Yan, X.P.; Qian, H.L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. Direct-Ink-Write 3D Printing of Programmable Micro-Supercapacitors from MXene-Regulating Conducting Polymer Inks. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2203683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, A.D.; Busbee, T.A.; Boley, J.W.; Raney, J.R.; Chortos, A.; Kotikian, A.; Berrigan, J.D.; Durstock, M.F.; Lewis, J.A. Hybrid 3D Printing of Soft Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.Y.; Arif, Z.U.; Tariq, A.; Hossain, M.; Khan, K.A.; Umer, R. 3D printing of magneto-active smart materials for advanced actuators and soft robotics applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 205, 112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, A.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Ghasemi, I.; Khodaei, M.; Baniassadi, M.; Abrinia, K.; Baghani, M. 3D printing super stretchable propylene-based elastomer. Mater. Lett. 2024, 361, 136075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, A.; Su, P.C.; Kim, J.H.; Ng, C.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.; Noh, J.; Subramanian, A.S.; Yoon, Y.J. 4D printing materials for vat photopolymerization. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 44, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Chu, P.K.; Gelinsky, M. 3D printing of hydrogels: Rational design strategies and emerging biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 140, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, T.; Morais, M.; Silvestre, S.; Carlos, E.; Coelho, J.; Almeida, H.V.; Barquinha, P.; Fortunato, E.; Martins, R. Direct Laser Writing: From Materials Synthesis and Conversion to Electronic Device Processing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2402014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Daobing, C.; Yan, Z.; Shifeng, W.; Chunze, Y.; Yusheng, S. Research status and prospect of additive manufacturing of intelligent materials. Cailiao Gongcheng 2022, 50, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, Y.; Rosen, D.W. Intelligent additive manufacturing and design state of the art and future perspectives. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Jining, D.; Shoukat, K.; Shoukat, M.U.; Nawaz, S.A. A Human-Machine Interaction Mechanism: Additive Manufacturing for Industry 5.0-Design and Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Han, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xue, L.; Liu, S. Additive Manufacturing Provides Infinite Possibilities for Self-Sensing Technology. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2400816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Saleh, T.; Jahan, M.P.; McGarry, C.; Chaudhari, A.; Huang, R.; Tauhiduzzaman, M.; Ahmed, A.; Al Mahmud, A.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; et al. Review of Intelligence for Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing: Current Status and Future Prospects. Micromachines 2023, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapa, M.T.; Sivasankarapillai, G.; Lalevee, J.; Laborie, M.P. Direct Ink Writing and Photocrosslinking of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose into Stable 3D Parts Using Methacrylation and Blending. Polymers 2025, 17, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, R.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W.; Zhao, W. Ultra-elastic conductive silicone rubber composite foams for durable piezoresistive sensors via direct ink writing three-dimensional printing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 504, 158733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Campbell, R.R.; Periyasamy, M.; Hickner, M.A. Additive manufacturing of silicone-thermoplastic elastomeric composite architectures. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 4409–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqerrout, S.; Wu, D.; Yu, F.; Liu, W.; Han, Y.; Lyu, J.; Jing, Y.; Yang, X. Recycling catfish bone for additive manufacturing of silicone composite structures. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Xu, F.; Fang, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Sun, D. Direct Ink Writing of Liquid Metal on Hydrogel through Oxides Introduction. Langmuir 2024, 40, 19830–19838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Tang, R.; Zheng, X.; Chen, G.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Peng, B. Structurally regulated hydrogel evaporator with excellent salt-resistance for efficient solar interfacial water evaporation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Xuan, F. Strain sensing behavior of FDM 3D printed carbon black filled TPU with periodic configurations and flexible substrates. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 74, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y. 3D Printing of Carbon Nanotube (CNT)/Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Functional Composites and Preparation of Highly Sensitive, Wide-range Detectable, and Flexible Capacitive Sensor Dielectric Layers via Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.; Kim, J.; Cao, L. A Comparative Analysis of Chemical, Plasma and In Situ Modification of Graphene Nanoplateletes for Improved Performance of Fused Filament Fabricated Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites Parts. Polymers 2022, 14, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.M.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, C.-L. Influence of printing angle and surface polishing on the friction and wear behavior of DLP-printed polyurethane. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 45, 112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Cho, S. Comparative Studies on Polyurethane Composites Filled with Polyaniline and Graphene for DLP-Type 3D Printing. Polymers 2020, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.H.; Won, J.C.; Lim, W.B.; Lee, J.H.; Min, J.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Huh, P. Highly Flexible and Photo-Activating Acryl-Polyurethane for 3D Steric Architectures. Polymers 2021, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prak, D.J.L.; Costello, P.; Novack, M.; Baker, B.W.; Cowart, J.S.; Durkin, D.P. Evaluating the thermal, mechanical and swelling behavior of novel silicone and polyurethane additively manufactured O-rings in the presence of organic liquids and military fuels. J. Elastomers Plast. 2024, 56, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Yu, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Meng, J.; Ma, H.; He, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Reed-Inspired Three-Dimensional Printed Microcolumn Array Reinforced Hierarchically Structured Composites for Efficient Noise Reduction. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 10706–10717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Abbas, N.; Kwon, Y.S.; Kim, D. Transforming biofabrication with powder bed fusion additive manufacturing technology: From personalized to multimaterial solutions. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 10, 4349–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, A.U.H.; Wei, D. Advancements in Additive Manufacturing of Tantalum via the Laser Powder Bed Fusion (PBF-LB/M): A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2023, 16, 6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Li, L. Recent progress and scientific challenges in multi-material additive manufacturing via laser-based powder bed fusion. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2021, 16, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandra, A.; Li, K.; Spurling, D.; Ronan, O.; Nicolosi, V. Aerosol Jet Printed MXene Microsupercapacitors for Flexible and Washable Textile Energy Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 23, e10255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, H.; Das, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, Z.S. Multitasking MXene Inks Enable High-Performance Printable Microelectrochemical Energy Storage Devices for All-Flexible Self-Powered Integrated Systems. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolhosseinzadeh, S.; Schneider, R.; Verma, A.; Heier, J.; Nuesch, F.; Zhang, C. Turning Trash into Treasure: Additive Free MXene Sediment Inks for Screen-Printed Micro-Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, N.M.; Carve, M.; Kaslin, J.; Wlodkowic, D. Characterization of 3D-Printed Moulds for Soft Lithography of Millifluidic Devices. Micromachines 2018, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, D.A.; Herzberger, J.; Long, T.E.; Williams, C.B. Ultraviolet-Assisted Direct Ink Write to Additively Manufacture All-Aromatic Polyimides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 34828–34833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R. 3D printing of multi-scalable structures via high penetration near-infrared photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, P.; Yesuf, M.B.; Govindarajan, R.; Niju, S.; Periyasamy, S.; Rabba, Z.A.; Pandiyarajan, T.; Kadier, A.; Mani, D.; Alemayehu, E. Combined ozone, photo, and electrocoagulation technologiesAn innovative technique for treatment of distillery industrial wastewater. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 29, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Kuang, X.; Roach, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Hamel, C.M.; Lu, C.; Qi, H.J. Integrating digital light processing with direct ink writing for hybrid 3D printing of functional structures and devices. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 40, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.C.; Critchley, S.E.; Rencsok, E.M.; Kelly, D.J. A comparison of different bioinks for 3D bioprinting of fibrocartilage and hyaline cartilage. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.C.; Ames, D.C.; Mueller, J. Multimaterial extrusion 3D printing printheads. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2025, 22, 5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyappa, R.; Ching, T.; Hashimoto, M. Embedded Ink Writing (EIW) of Polysiloxane Inks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20–23565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Chi, B.; Li, B.; Gao, Z.; Du, Y.; Guo, J.; Wei, J. Fabrication of highly conductive graphene flexible circuits by 3D printing. Synth. Met. 2016, 217, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; So, H. 3D-printing-assisted flexible pressure sensor with a concentric circle pattern and high sensitivity for health monitoring. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, Z.; Kong, S.; Tang, S.; Feng, D.; Li, B. Wide-response-range and high-sensitivity piezoresistive sensors with triple periodic minimal surface (TPMS) structures for wearable human-computer interaction systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 287, 111840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kado Abdalkader, R.; Konishi, S.; Fujita, T. Development of a flexible 3D printed TPU-PVC microfluidic devices for organ-on-a-chip applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.I.; Wu, W.; Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F. Bio-inspired hybrid composite fabrication 3D-printing approach for multifunctional flexible wearable sensors applications. Compos. Struct. 2025, 362, 119064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q. 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced TPU metamaterials for flexible multifunctional sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrisiswadi, H.; Atsani, S.I.; Sari, W.P.; Herianto, H. Design and parameters optimisation of fused deposition modelling (FDM) technology in the fabrication of sensorised soft pneumatic actuator. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 9811–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyanes, A.; Det-Amornrat, U.; Wang, J.; Basit, A.W.; Gaisford, S. 3D scanning and 3D printing as innovative technologies for fabricating personalized topical drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2016, 234, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Wang, J.; Senthil, T.; Wu, L. Mechanical and thermal properties of ABS/montmorillonite nanocomposites for fused deposition modeling 3D printing. Mater. Des. 2016, 102, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado, A.R.; Shemelya, C.M.; English, J.D.; Lin, Y.; Wicker, R.B.; Roberson, D.A. Characterizing the effect of additives to ABS on the mechanical property anisotropy of specimens fabricated by material extrusion 3D printing. Addit. Manuf. 2015, 6, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.C.; Tandon, G.P.; Bradford, R.L.; Koerner, H.; Baur, J.W. Process-structure-property effects on ABS bond strength in fused filament fabrication. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Espin, M.; Puigoriol-Forcada, J.M.; Garcia-Granada, A.-A.; Lluma, J.; Borros, S.; Reyes, G. Mechanical property characterization and simulation of fused deposition modeling Polycarbonate parts. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Latteri, A.; Del Curto, B.; Lo Russo, A.; Recca, G.; Fare, S. Engineering thermoplastics for additive manufacturing: A critical perspective with experimental evidence to support functional applications. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. 2017, 15, E10–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Ognibene, G.; Portuesi, S.; Blanco, I.; Rapisarda, M.; Pergolizzi, E.; Recca, G. Comparison of Ultem 9085 Used in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) with Polytherimide Blends. Materials 2018, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.C.; Li, D.Y.; Farooqui, A.; Huang, S.H. Development of a cost-effective technology for fabricating high-performance plastic gears. Wear 2025, 576, 206135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, U.; Southee, D.; Johnson, A. Investigating the Reliability and Dynamic Response of Fully 3D-Printed Thermistors. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, A. Investigation of the Effect of Exposure to Liquid Chemicals on the Strength Performance of 3D-Printed Parts from Different Filament Types. Polymers 2025, 17, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.J.; Golias, C.J.; Vaske, T.J.; Young, S.A.; Chen, Q.; Goodbred, L.; Rong, L.; Cheng, X.; Penumadu, D.; Advincula, R.C. Correlating viscosity and die swell in 3D printing of polyphenylsulfone: A thermo-mechanical optimization modus operandi. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 194, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, I.R.; Koloor, S.S.; Kumar, D.; Yahya, M.Y. On Laminated Object Manufactured FDM-Printed ABS/TPU Multimaterial Specimens: An Insight into Mechanical and Morphological Characteristics. Polymers 2022, 14, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharari, M.; Chen, B.; Shu, W. 3D Printing of Highly Stretchable and Sensitive Strain Sensors Using Graphene Based Composites. Proceedings 2018, 2, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Peng, Z.; Jing, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E. Preparation of Highly Efficient Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Polylactic Acid/Graphene Nanocomposites for Fused Deposition Modeling Three-Dimensional Printing Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 15565–15575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Huang, B.; Zhang, X.; Ge, S.S.; Wei, X. 3D Printed Flexible Piezoelectric Sensor with Enhanced Performance for Gait Recognition. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 6015–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, K.; Isreb, A.; Alhnan, M.A. A flexible-dose dispenser for immediate and extended release 3D printed tablets. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 96, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, M.A.S.R.; Maguire, A.; Pottackal, N.T.; Thakur, M.S.H.; Ikram, M.M.; Hart, A.J.; Ajayan, P.M.; Rahman, M.M. Direct Ink Writing: A 3D Printing Technology for Diverse Materials. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Willenbacher, N. Phase-Change-Enabled, Rapid, High-Resolution Direct Ink Writing of Soft Silicone. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Chen, C.; Yu, A.; Feng, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhou, R.; Zhuang, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Multilayer Step-like Microstructured Flexible Pressure Sensing System Integrated with Patterned Electrochromic Display for Visual Detection. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 19488–19496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Ramirez, A.B.; Akbarnia, N.; Croiset, E.; Prince, E.; Fuller, G.G.; Kamkar, M. Direct Ink Writing of Conductive Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2415507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; De Marzi, A.; Huang, K.; He, R.; Colombo, P. Zhaozhou Bridge inspired embedded material extrusion 3D printing of Csf/SiC ceramic matrix composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Quinn, B.; Lebel, L.L.; Therriault, D.; L’Espérance, G. Multi-Material Direct Ink Writing (DIW) for Complex 3D Metallic Structures with Removable Supports. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 8499–8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Gao, Y.; Pan, L.; Xuan, F. All Digital Light Processing-3D Printing of Flexible Sensor. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yu, S.; Wang, R.; Ge, Q. Digital light processing based multimaterial 3D printing: Challenges, solutions and perspectives. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Sullivan, K.; Priye, A. Multi-Resin Masked Stereolithography (MSLA) 3D Printing for Rapid and Inexpensive Prototyping of Microfluidic Chips with Integrated Functional Components. Biosensors 2022, 12, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Wu, Q.; Clancy, T.; Fan, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. 3D-Printed Strain-Gauge Micro Force Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 6971–6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Duvedi, R.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Batish, A. Navigating the frontier: Additive Manufacturing’s role in synthesizing piezoelectric materials for flexible electronics. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2025, 38, 1598–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarek, M.; Layani, M.; Cooperstein, I.; Sachyani, E.; Cohn, D.; Magdassi, S. 3D Printing of Shape Memory Polymers for Flexible Electronic Devices. Adv. Mater. 2015, 28, 4449–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Ji, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Bai, J. Highly flexible, thermally stable, and static dissipative nanocomposite with reduced functionalized graphene oxide processed through 3D printing. Part B Eng. 2021, 208, 108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, M.; Song, K.H. Development of Hydrogels Fabricated via Stereolithography for Bioengineering Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.R.; Goyanes, A.; Basit, A.W.; Gaisford, S. Fabrication of drug-loaded hydrogels with stereolithographic 3D printing. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 532, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Cohn, D. Temperature and pH responsive 3D printed scaffolds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 9514–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zips, S.; Hiendlmeier, L.; Weiss, L.J.K.; Url, H.; Teshima, T.F.; Schmid, R.; Eblenkamp, M.; Mela, P.; Wolfrum, B. Biocompatible, Flexible, and Oxygen-Permeable Silicone-Hydrogel Material for Stereolithographic Printing of Microfluidic Lab-On-A-Chip and Cell-Culture Devices. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Gomri, C.; Benkhaled, B.T.; Habib, M.; Dupuis, R.; Petit, E.; Richard, J.; Segala, A.; Lichon, L.; Nguyen, C.; et al. Efficient PFAS Removal Using Reusable and Non-Toxic 3D Printed Porous Trianglamine Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2410720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventisette, I.; Mattii, F.; Dallari, C.; Capitini, C.; Calamai, M.; Muzzi, B.; Pavone, F.S.; Carpi, F.; Credi, C. Gold-Hydrogel Nanocomposites for High-Resolution Laser-Based 3D Printing of Scaffolds with SERS-Sensing Properties. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 4497–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Sun, H.; Wu, X.; Fang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Z. Study of Magnetic Hydrogel 4D Printability and Smart Self-Folding Structure. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2401602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Gallardo, A.; Lopez, D.; Elvira, C.; Azzahti, A.; Lopez Martinez, E.; Cortajarena, A.L.; Gonzalez Henriquez, C.M.; Sarabia Vallejos, M.A.; Rodriguez Hernandez, J. Smart pH-Responsive Antimicrobial Hydrogel Scaffolds Prepared by Additive Manufacturing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, L.J.Y.; Islam, A.B.; DasGupta, R.; Iyer, N.G.; Leo, H.L.; Toh, Y.C. A 3D printed microfluidic perfusion device for multicellular spheroid cultures. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viray, C.M.; van Magill, B.; Zreiqat, H.; Ramaswamy, Y. Stereolithographic Visible-Light Printing of Poly(l-glutamic acid) Hydrogel Scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, H.K.; Karumuri, R.T.; Prajapati, A.R.; Rajpurohit, S.R. Specific energy absorption during compression testing of ABS and FPU parts fabricated using LCD-SLA based 3D printer. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Feng, J.; Yu, L.; Lin, Z.; Guo, Q.; Huang, J.; Mao, J.; et al. 3D printing of micro-nano devices and their applications. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentinčič, J.; Prijatelj, M.; Jerman, M.; Lebar, A.; Sabotin, I. Characterization of a Custom-Made Digital Light Processing Stereolithographic Printer Based on a Slanted Groove Micromixer Geometry. J. Micro Nano-Manuf. 2020, 8, 010911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fan, X.; Dong, L.; Jiang, C.; Weeger, O.; Zhou, K.; Wang, D. Voxel Design of Grayscale DLP 3D-Printed Soft Robots. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2309932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Deng, X.; Wang, P.; Yu, C.; Kiratitanaporn, W.; Wu, X.; Schimelman, J.; Tang, M.; Balayan, A.; Yao, E.; et al. Rapid bioprinting of conjunctival stem cell micro-constructs for subconjunctival ocular injection. Biomaterials 2021, 267, 2309932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, C.K.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. In-situ ultrasonic monitoring for Vat Photopolymerization. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Morde, R.S.; Mariani, S.; La Mattina, A.A.; Vignali, E.; Yang, C.; Barillaro, G.; Lee, H. 4D Printing of a Bioinspired Microneedle Array with Backward-Facing Barbs for Enhanced Tissue Adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, A.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, Y.T.; Song, J.Y.; Park, S.H.; Ha, C.W. Improving the Reliability of Digital Light Processing Printing Using a Digital Micromirror Device Grayscale-Gaussian Correction Method. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 22–13753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menassol, G.; van der Sanden, B.; Gredy, L.; Arnol, C.; Divoux, T.; Martin, D.K.; Stephan, O. Gelatine–collagen photo-crosslinkable 3D matrixes for skin regeneration. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 1738–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yue, L.; Liang, S.; Montgomery, S.; Lu, C.; Cheng, C.M.; Beyah, R.; Zhao, R.R.; Qi, H.J. Multi-Color 3D Printing via Single-Vat Grayscale Digital Light Processing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2112329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.S.; Kim, J.W.; Recker, E.A.; Nymick, J.M.; Shi, M.; Stolpen, F.A.; Ju, J.; Page, Z.A. Multicolor Digital Light Processing 3D Printing Enables Dissolvable Supports for Freestanding and Non-Assembly Structures. ACS Cent. Sci. 2025, 11, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, C.; Tao, T.; Feng, S.; Huang, L.; Asundi, A.; Chen, Q. Micro Fourier Transform Profilometry (μFTP): 3D shape measurement at 10,000 frames per second. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 102, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y. A Novel 3D Seam Extraction Method Based on Multi-Functional Sensor for V-Type Weld Seam. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 182415–182424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Jang, S.; Kuss, M.A.; Alimi, O.A.; Liu, B.; Palik, J.; Tan, L.; Krishnan, M.A.; Jin, Y.; Yu, C.; et al. Digital Light Processing 4D Printing of Poloxamer Micelles for Facile Fabrication of Multifunctional Biocompatible Hydrogels as Tailored Wearable Sensors. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 7580–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, C.; Gong, H.; Nie, Q.; Long, Y. 3D printing highly stretchable conductors for flexible electronics with low signal hysteresis. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2022, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Ye, H.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Ge, Q. Stretchable Ultraviolet Curable Ionic Conductive Elastomers for Digital Light Processing Based 3D Printing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2202088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Rong, Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, P.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, X. DLP printing PEG-based gels with high elasticity and anti-dryness for customized flexible sensors. Polymer 2025, 319, 128049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Geng, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Lan, D.; Fan, B. Designing MXene hydrogels for flexible and high-efficiency electromagnetic wave absorption using digital light processing 3D printing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.F.; Li, H.; He, X.; Yuan, C.; Liu, J.; Magdassi, S.; et al. 3D printing of highly stretchable hydrogel with diverse UV curable polymers. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaba4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Xu, W.; He, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Feng, P. Layered co-continuous structure in bone scaffold fabricated by laser additive manufacturing for enhancing electro-responsive shape memory properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Li, R.; Kang, J.; Luo, M.; Yuan, T.; Han, C. Achieving superelastic shape recoverability in smart flexible CuAlMn metamaterials via 3D printing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 195, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaee, M.; Crane, N.B. Binder jetting: A review of process, materials, and methods. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Cai, J.; Zhang, B.; Qu, X. Key technology of binder jet 3D printing. J. Mater. Eng. 2023, 51, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafaei, A.; Elliott, A.M.; Barnes, J.E.; Li, F.; Tan, W.; Cramer, C.L.; Nandwana, P.; Chmielus, M. Binder jet 3D printing-Process parameters, materials, properties, modeling, and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 119, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2021, 8, 703–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeta, I.; Dutton, B.; Leach, R.K.; Piano, S. Finite element modelling of defects in additively manufactured strut-based lattice structures. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkal, E.; Banerjee, D.; Barto, R.; Sabolsky, K.; Sierros, K.A.; Sabolsky, E.M. 3D printing by direct ink writing (DIW) of UV-curable elastomers with embedded sensors for soft robotic and flexible electronic applications. Flex. Print. Electron. 2025, 10, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhou, M.; Drummer, D. Effects of Fumed Silica on Thixotropic Behavior and Processing Window by UV-Assisted Direct Ink Writing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, S.; Willems, E.; Soete, J.; Inokoshi, M.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J.; Zhang, F. UV-Curing Assisted Direct Ink Writing of Dense, Crack Free, and High Performance Zirconia Based Composites With Aligned Alumina Platelets. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, C.M.; Wyckoff, C.; Parvulescu, M.J.S.; Rueschhoff, L.M.; Dickerson, M.B. UV-assisted direct ink writing of Si3N4/SiC preceramic polymer suspensions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 3374–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Fu, K.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z. Efficiency Manipulation of Filaments Fusion in UV-Assisted Direct Ink Writing. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijender; Kumar, A. Flexible and wearable capacitive pressure sensor for blood pressure monitoring. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2021, 33, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelayo, F.; Blanco, D.; Fernandez, P.; Gonzalez, J.; Beltran, N. Viscoelastic Behaviour of Flexible Thermoplastic Polyurethane Additively Manufactured Parts: Influence of Inner-Structure Design Factors. Polymers 2021, 13, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fateri, M.; Carneiro, J.F.; Frick, A.; Pinto, J.B.; de Almeida, F.G. Additive Manufacturing of Flexible Material for Pneumatic Actuators Application. Actuators 2021, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, E.; Jimenez, M.; Romero, L.; del Mar Espinosa, M.; Dominguez, M. Characterization of the resistance to abrasive chemical agents of test specimens of thermoplastic elastomeric polyurethane composite materials produced by additive manufacturing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Cong, W.; Hu, Z.; Huang, K. Additive manufacturing of thermoplastic matrix composites using fused deposition modeling: A comparison of two reinforcements. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 3733–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, L.; Kumar, N.K.; Abd Rahim, S.Z.; Rasidi, M.S.M.; Rennie, A.E.W.; Rahman, R.; Kanani, A.Y.; Azmi, A.A. A review on the potential of polylactic acid based thermoplastic elastomer as filament material for fused deposition modelling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2841–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, V.; Massimo, G.; Manuela, G. Additive manufacturing of flexible thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU): Enhancing the material elongation through process optimisation. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 2877–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.N.; Abdullah, J.; Shuib, R.K.; Aziz, I.; Namazi, H. 4D printing of polylactic acid (PLA)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) shape memory polymer—A review. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 012402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.M.; Sonawane, R.Y.; More, A.P. Thermoplastic polyurethane for three-dimensional printing applications: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2023, 34, 2061–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.S.; Verma, N.; Yesu, A.; Banerjee, S.S. Material extrusion additive manufacturing of TPU blended ABS with particular reference to mechanical and damping performance. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z.; Ghazaly, M.M.; Muhamad, A.; Haslyanti, M.; Ali, M.A.M.; Kasim, M.S.; Sued, M.K. Solution for Pes Planus Discomfort Using Corrective Personalized Orthotic Insole via Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 6th Mechanical Engineering Research Day (MERD), Melaka, Malaysia, 31 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilinska, K.; Kozun, M.; Pezowicz, C. Elastic Properties of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Fabricated Using Multi Jet Fusion Additive Technology. Polymers 2025, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Dou, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, F.; Jing, S. Additive manufacture of programmable multi-matrix continuous carbon fiber reinforced gradient composites. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 89, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.S.; Dominguez Calvo, A.; Molina, S.I. Materials with enhanced adhesive properties based on acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) blends for fused filament fabrication (FFF). Mater. Des. 2019, 182, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.R.G.; Farrow, I.R.; Trask, R.S. Compressive behaviour of 3D printed thermoplastic polyurethane honeycombs with graded densities. Mater. Des. 2019, 162, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, Y.; Sun, L.; Guo, X. Multimaterial Metamaterial Inverse Design via Machine Learning for Tailorable and Reusable Energy Absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 38203–38214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagac, M.; Schwarz, D.; Petru, J.; Polzer, S. 3D printed polyurethane exhibits isotropic elastic behavior despite its anisotropic surface. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Korlos, A.; Velidakis, E.; Mountakis, N.; Charou, C.; Myftari, A. Strain Rate Sensitivity of Polycarbonate and Thermoplastic Polyurethane for Various 3D Printing Temperatures and Layer Heights. Polymers 2021, 13, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Z.; Ozer, N.E.; Akan, T.; Kılıcarslan, M.A.; Karaagaclıoglu, L. The impact of different surface treatments on repair bond strength of conventionally, subtractive-, and additive-manufactured denture bases. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 36, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrover Monserrat, B.; Llumà, J.; Jerez Mesa, R.; Travieso Rodriguez, J.A. Study of the Influence of the Manufacturing Parameters on Tensile Properties of Thermoplastic Elastomers. Polymers 2022, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crupano, W.; Adrover Monserrat, B.; Llumà, J.; Jerez Mesa, R. Investigating mechanical properties of 3D printed polylactic acid/poly-3-hydroxybutyrate composites Compressive and fatigue performance. Heliyon 2024, 18, e38066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, Z.; Yousef, S.; Tatariants, M.; Krugly, E.; Ciuzas, D.; Danilovas, P.P.; Baltusnikas, A.; Martuzevicius, D. Fibrous PEBA-graphene nanocomposite filaments and membranes fabricated by extrusion and additive manufacturing. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 121, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Kong, C.I.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.; Moon, S.Y. High-flux CO2 separation using thin-film composite polyether block amide membranes fabricated by transient-filler treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Deo, K.A.; Lee, H.P.; Soukar, J.; Namkoong, M.; Tian, L.; Jaiswal, A.; Gaharwar, A.K. 3D Printed Electronic Skin for Strain, Pressure and Temperature Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Song, Y.; Liu, P. Transparent and Flexible Amphiphobic Coatings with Excellent Fold Resistance via Solvent-Free Coating and Photocuring of Fluorinated Liquid Nitrile–Butadiene Rubber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26498–26504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, X.; Li, Q.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y. Synergistic improvement of mechanical and piezoelectric properties of the flexible piezoelectric ceramic composite and its high-precision preparation. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 27923–27932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Jia, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F. 3D Printing of Photocuring Elastomers with Excellent Mechanical Strength and Resilience. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, 1800873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Alfaro, A.; Mitoudi-Vagourdi, E.; Dimov, I.; Picchio, M.L.; Lopez-Larrea, N.; de Lacalle, J.L.; Tao, X.; Serrano, R.R.M.; Gallastegui, A.; Vassardanis, N.; et al. Light-Based 3D Multi-Material Printing of Micro-Structured Bio-Shaped, Conducting and Dry Adhesive Electrodes for Bioelectronics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2306424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.R.; Gong, M.S. Preparation of epoxy/polyelectrolyte IPNs for flexible polyimide-based humidity sensors and their properties. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 178, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Jeon, W.; Lee, S.; Onoue, S.; Hwang, H.D.; Gierschner, J.; Kwon, M.S. A Multicomponent Visible-Light Initiating System for Rapid and Deep Photocuring through UV-Opaque Polyimide Films. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 1741–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, G. Poly(dimethyl siloxane) bimodal brush: Simple method of preparation and performance enhancement of omniphobic coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, X. 3D-printed flexible sensors for food monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 146011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachyani Keneth, E.; Kamyshny, A.; Totaro, M.; Beccai, L.; Magdassi, S. 3D Printing Materials for Soft Robotics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 33, 2003387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Sun, F. Photocured Materials with Self-Healing Function through Ionic Interactions for Flexible Electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26694–26704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, K.; Zheng, H.; Kripalani, D.R.; Zeng, Z.; Jarlov, A.; Chen, J.; Bai, L.; Ong, A.; Du, H.; et al. Additively Manufactured Dual-Faced Structured Fabric for Shape-Adaptive Protection. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, A.T.; Miandashti, Z.Z.; Momeni, S.A. Impact of structural characteristics on energy-absorption of 3D-printed thermoplastic polyurethane line-oriented structures. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Hussain, C.M. 3D-Printed Hydrogel for Diverse Applications: A Review. Gels 2023, 9, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Tang, R.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Photocuring 3D Printing of Hydrogels: Techniques, Materials, and Applications in Tissue Engineering and Flexible Devices. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, 2300661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.D.; Tang, G.P.; Chu, P.K. Cyclodextrin-Based Host–Guest Supramolecular Nanoparticles for Delivery: From Design to Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloxin, A.M.; Kloxin, C.J.; Bowman, C.N.; Anseth, K.S. Mechanical Properties of Cellularly Responsive Hydrogels and Their Experimental Determination. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3484–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wei, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Pei, X.; Wu, D.; et al. Peptide-based rigid nanorod-reinforced gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels for osteochondral regeneration and additive manufacturing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkes Burkey, C.; Shepherd, R.F. Volumetric 3D Printing of Endoskeletal Soft Robots. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2402217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Tyagi, P.; Agate, S.; McCord, M.G.; Lucia, L.A.; Pal, L. Highly tunable bioadhesion and optics of 3D printable PNIPAm/cellulose nanofibrils hydrogels. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 234, 115898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bethel, K.; Singh, M.; Zhang, J.; Ashkar, R.; Davis, E.M.; Johnson, B.N. Comparison of Bulk- vs Layer-by-Layer-Cured Stimuli-Responsive PNIPAM–Alginate Hydrogel Dynamic Viscoelastic Property Response via Embedded Sensors. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 5596–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hu, Y.; Feng, H. Investigation of 3D-printed PNIPAM-based constructs for tissue engineering applications: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 17727–17750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, B.; Paulsen, S.J.; Corbett, D.C.; Sazer, D.W.; Fortin, C.L.; Zaita, A.J.; Greenfield, P.T.; Calafat, N.J.; Gounley, J.P.; Ta, A.H.; et al. Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels. Science 2019, 364, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhu, W.; Holmes, B.; Zhang, L.G. Biologically Inspired Smart Release System Based on 3D Bioprinted Perfused Scaffold for Vascularized Tissue Regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1600058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, F.; Li, Y.; Shen, G.; Lee, J.C. Incorporating Wireless Strategies to Wearable Devices Enabled by a Photocurable Hydrogel for Monitoring Pressure Information. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2300855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, L.; Lu, S.; Zhu, T.; Da, X.; Li, Y.; Bu, H.; Gao, G.; Ding, S. Highly Stretchable Organogel Ionic Conductors with Extreme-Temperature Tolerance. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3257–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, G.; Zheng, J. A tough and piezoelectric poly(acrylamide/N,N-dimethylacrylamide) hydrogel-based flexible wearable sensor. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 6800–6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Li, H.; Rong, Y.; Fei, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; An, J.; Huang, X. High-tear resistant gels crosslinked by DA@CNC for 3D printing flexible wearable devices. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 135711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Rong, Y.; Qin, G.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhang, X.; Hang, R.; Yao, X.; Huang, X. 3D printable eutectogels with good swelling resistance and electrochemical stability for underwater sensing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 709, 136108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.N.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, Z.L. Recent advances in 3D printing of tough hydrogels: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 238, 109895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valveza, S.; Santosa, P.; Parentea, J.M.; Silvaa, M.P.; Reis, P.N.B. 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced PLA composites: A short review. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020, 25, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.M.; Bernalte, E.; Crapnell, R.D.; Whittingham, M.J.; Muñoz, R.A.A.; Banks, C.E. Advances in additive manufacturing for flexible sensors: Bespoke conductive TPU for multianalyte detection in biomedical applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 42, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Medora, E.; Ren, Z.; Cheng, M.; Namilae, S.; Jiang, Y. Coaxial direct ink writing of ZnO functionalized continuous carbon fiber-reinforced thermosetting composites. Compos. Sc. Technol. 2024, 256, 110782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Chen, S.; Feng, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, R.; Gao, J.; Cui, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. Anisotropic 3D-Printed Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Liquid Metal Elastomer for Synergistic Enhancement of Electrical Conductivity, Thermal Performance, and Leakage Resistance. Adv. Mater. 2025, e11498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez del Rio, J.; Pascual Gonzalez, C.; Martinez, V.; Luis Jimenez, J.; Gonzalez, C. 3D-printed resistive carbon-fiber-reinforced sensors for monitoring the resin frontal flow during composite manufacturing. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 317, 112422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnageham Sidharthan, S.; Keloth Paduvilan, J.; Velayudhan, P.; Kalarikkal, N.; Zapotoczny, S.; Thomas, S. Development of Silicone Rubber-Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Composites for Strain-Sensing Applications: Morphological, Mechanical, Electrical, and Sensing Properties. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 4406–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimene, D.; Kaunas, R.; Gaharwar, A.K. Hydrogel Bioink Reinforcement for Additive Manufacturing: A Focused Review of Emerging Strategies. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1902026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guvendiren, M.; Molde, J.; Soares, R.M.D.; Kohn, J. Designing Biomaterials for 3D Printing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1679–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loessner, D.; Meinert, C.; Kaemmerer, E.; Martine, L.C.; Yue, K.; Levett, P.A.; Klein, T.J.; Melchels, F.P.W.; Khademhosseini, A.; Hutmacher, D.W. Functionalization, preparation and use of cell-laden gelatin methacryloyl–based hydrogels as modular tissue culture platforms. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 727–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; He, J.; Lin, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. 3D gel-printing of hydroxyapatite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; McKeon, L.; Garcia, J.; Pinilla, S.; Barwich, S.; Möbius, M.; Stamenov, P.; Coleman, J.N.; Nicolosi, V. Additive Manufacturing of Ti3C2-MXene-Functionalized Conductive Polymer Hydrogels for Electromagnetic-Interference Shielding. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, 2106253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, T.J.; Jallerat, Q.; Palchesko, R.N.; Park, J.H.; Grodzicki, M.S.; Shue, H.; Ramadan, M.H.; Hudson, A.R.; Feinberg, A.W. Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo Woo, S.; Yunjin, J.; Sunghoon, K. Photocurable Polymer Nanocomposites for Magnetic, Optical, and Biological Applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2015, 21, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Chen, H.F.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, J.H.; Lu, M.C.; Chiu, C.W. Photocurable 3D-printed AgNPs/Graphene/Polymer nanocomposites with high flexibility and stretchability for ECG and EMG smart clothing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, V.S.D.; Strating, T.; Schnelting, G.H.M.; Dijkstra, P.; Tietema, M.; Xu, J.; Woortman, A.J.J.; Loos, K.; Jager, J.; Folkersma, R. Biobased Acrylate Photocurable Resin Formulation for Stereolithography 3D Printing. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, A.P.; Davidson, M.D.; Zlotnick, H.M.; Kolibaba, T.J.; Killgore, J.P.; Burdick, J.A. Additive manufacturing of highly entangled polymer networks. Science 2024, 385, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelma, J.; Rolland, J. Rethinking digital manufacturing with polymers. Science 2017, 358, 1384–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obst, P.; Riedelbauch, J.; Oehlmann, P.; Rietzel, D.; Launhardt, M.; Schmölzer, S.; Osswald, T.A.; Witt, G. Investigation of the influence of exposure time on the dual-curing reaction of RPU 70 during the DLS process and the resulting mechanical part properties. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmann, A.; Oehlmann, P.; Scheffler, T.; Kagermeier, L.; Osswald, T.A. Thermal curing kinetics optimization of epoxy resin in Digital Light Synthesis. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Francos, X.; Konuray, O.; Ramis, X.; Serra, À.; De la Flor, S. Enhancement of 3D-Printable Materials by Dual-Curing Procedures. Materials 2020, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, J.F.; Aliheidari, N.; Poetschke, P.; Ameli, A. Bidirectional and Stretchable Piezoresistive Sensors Enabled by Multimaterial 3D Printing of Carbon Nanotube/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposites. Polymers 2019, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhameni, A.; Cheng, R.; Farrow, T. A Precision Method for Integrating Shock Sensors in the Lining of Sports Helmets by Additive Manufacturing. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2022, 6, 5000704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganiello, C.; Naso, D.; Cupertino, F.; Fiume, O.; Percoco, G. Investigating the Potential of Commercial-Grade Carbon Black-Filled TPU for the 3D Printing of Compressive Sensors. Micromachines 2019, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaroni, C.; Vitali, L.; Lo Presti, D.; Silvestri, S.; Schena, E. Fully Additively 3D Manufactured Conductive Deformable Sensors for Pressure Sensing. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohimer, C.J.; Petrossian, G.; Ameli, A.; Mo, C.; Pötschke, P. 3D printed conductive thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube composites for capacitive and piezoresistive sensing in soft pneumatic actuators. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyr, G.; DeSimone, J.M. Review of high-performance sustainable polymers in additive manufacturing. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, A.; Yeazel, T.R.; Asheghali, D.; Petersen, S.R.; Dort, S.; Gall, K.; Becker, M.L. Fabrication of Biomedical Scaffolds Using Biodegradable Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11238–11304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolitha, B.S.; Jayasekara, S.K.; Tannenbaum, R.; Jasiuk, I.M.; Jayakody, L.N. Repurposing of waste PET by microbial biotransformation to functionalized materials for additive manufacturing. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 50, kuad010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, B.; James, J.; Grohens, Y.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. Additive Manufacturing of Poly (ε-Caprolactone) for Tissue Engineering. JOM 2020, 72, 4127–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kade, J.C.; Dalton, P.D. Polymers for Melt Electrowriting. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Pillay, S.; Ning, H. Innovative continuous polypropylene fiber composite filament for material extrusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, I.L.; Mondini, A.; Del Dottore, E.; Filippeschi, C.; Pignatelli, F.; Mazzolai, B. 3D printed composites from heat extruded polycaprolactone/sodium alginate filaments and their heavy metal adsorption properties. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 2472–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, P.K.; Fan, F.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Liao, P.B.; Huang, C.F.; Shen, Y.K.; Ruslin, M.; Lee, C.H. Bioactivity and Bone Cell Formation with Poly-ε-Caprolactone/Bioceramic 3D Porous Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.J.; Jeong, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.J.; Jo, J.; Shanmugasundaram, A.; Kim, H.; Choi, E.; Lee, D.W. 3D-printed cardiovascular polymer scaffold reinforced by functional nanofiber additives for tunable mechanical strength and controlled drug release. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza, M.; Rezende, R.A.; da Silva, J.V.L.; Bartolo, P.J.; Sabino, M.A. Chitosan Microlayer on the Photografting Modified Surface of PLA, PCL and PLA/PCL Bioextruder Scaffolds. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Advanced Research in Virtual and Physical Prototyping, Leiria, Portugal, 1–5 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peluso, V.; De Santis, R.; Gloria, A.; Castagliuolo, G.; Zanfardino, A.; Varcamonti, M.; Russo, T. Design of 3D Additive Manufactured Hybrid Scaffolds for Periodontal Repair Strategies. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 6817–6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskova, A.O.; Mosnackova, K.; Musiol, M.; Opalek, A.; Buckova, M.; Rychter, P.; Andicsova, A.E. Electrospun Nisin-Loaded Poly(ε-caprolactone)-Based Active Food Packaging. Materials 2022, 15, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroz, W.; Szafraniec, J.; Kurek, M.; Jachowicz, R. 3D Printing in Pharmaceutical and Medical Applications—Recent Achievements and Challenges. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Shou, W.; Makatura, L.; Matusik, W.; Fu, K. 3D printing of polymer composites: Materials, processes, and applications. Matter 2022, 5, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenfield, S.J.; Awad, A.; Goyanes, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. 3D Printing Pharmaceuticals: Drug Development to Frontline Care. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, K.; Chen, Z. Current Status and Prospects of Additive Manufacturing of Flexible Piezoelectric Materials. J. Inorg. Mater. 2024, 39, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, M.; Hussein, H.; Aiche, G.; Haddab, Y.; Lutz, P.; Rubbert, L.; Renaud, P. Characterization of bistable mechanisms for microrobotics and mesorobotics: Comparison between microfabrication and additive manufacturing. J. Micro-Bio Robot. 2019, 15, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Goh, B.; Oh, Y.; Chung, H. Topology optimization for multi-axis additive manufacturing considering overhang and anisotropy. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 301, 110443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, B.; Ma, P. Advances in mechanical properties of flexible textile composites. Compos. Struct. 2023, 303, 116350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.Z.; Liu, J.S.; Lu, J.Q. Digital Light Processing 3D Printing Technology in Biomedical Engineering: A Review. Macromol. Biosci. 2025, 25, e2500101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Akram, T.; Chen, H.; Chen, S. On the Evolution of Additive Manufacturing (3D/4D Printing) Technologies: Materials, Applications, and Challenges. Polymers 2022, 14, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Luo, S.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Photo-curing 3D printing technique and its challenges. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, U.; Abrol, A.; Vora, N.P.; Tiwari, A.; Shanker, S.K.; Selvaraj, S.K. Performance evaluation of 3D printing technologies: A review, recent advances, current challenges, and future directions. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Longyu, C.; Zhengyu, L. A comparative review of multi-axis 3D printing. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 120, 1002–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marak, Z.R.; Tiwari, A.; Tiwari, S. Adoption of 3d printing technology: An innovation diffusion theory perspective. Int. J. Innov. 2019, 7, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.; Zapciu, A.; Amza, C.; Baciu, F.; Marinescu, R. FDM process parameters influence over the mechanical properties of polymer specimens: A review. Polym. Test. 2018, 69, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Xiao, X.; Yue, R. Process parameter optimization for fused deposition modeling using response surface methodology combined with fuzzy inference system. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 73, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Korolovych, V.; Lyu, Y.; Aslarus, J.; Flores-Hernandez, D.R.; Pajovic, S.; Heller, W.T.; Sihver, L.; Boriskina, S.V. Warpage-Resistant, Under-Extrusion-Free, High-Surface-Quality Additive Manufacturing Process for Polyethylene-Based Composite Radiation Shielding Material. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 12304–12320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golhin, A.P.; Tonello, R.; Frisvad, J.R.; Grammatikos, S.; Strandlie, A. Surface roughness of as-printed polymers: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 987–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyan, M.; Amu Darko, J.N.O.; Issaka, E.; Abban, O.J. Advances in fused deposition modeling on process, process parameters, and multifaceted industrial application: A review. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 012401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Qin, Q.H. The improvement of void and interface characteristics in fused filament fabrication-based polymers and continuous carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 1047–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlegenov, Y.; Wong, Y.S.; Hong, G.S. A dynamic model for nozzle clog monitoring in fused deposition modelling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancharaiah, T.; Ranga Raju, D.; Ramachandra Raju, V. An experimental investigation on surface quality and dimensionalaccuracy of FDM components. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.; Hussain, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Kakakhail, H.; Riaz, A.A.; Khan, I.; Ahmad, S.; Akram, W.; Eldin, S.M.; et al. Experimental investigation and Taguchi optimization of FDM process parameters for the enhancement of tensile properties of Bi-layered printed PLA-ABS. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 1995–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafaghani, A.A.; Qattawi, A. Investigating the effect of fused deposition modeling processing parameters using Taguchi design of experiment method. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 36, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, N.; Senthil, P.; Vinodh, S.; Jayanth, N. A review on composite materials and process parameters optimisation for the fused deposition modelling process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyavahare, S.; Teraiya, S.; Panghal, D.; Kumar, S. Fused deposition modelling: A review. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Zharylkassyn, B.; Seisekulova, A.; Akhmetov, M.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Optimisation of Strength Properties of FDM Printed Parts-A Critical Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, V.; Malagutti, L.; Mollica, F. FDM 3D Printing of Polymers Containing Natural Fillers: A Review of their Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, B.; Cui, C.; Guo, Y.; Yan, C. A critical review of fused deposition modeling 3D printing technology in manufacturing polylactic acid parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 2877–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samykano, M.; Selvamani, S.K.; Kadirgama, K.; Ngui, W.K.; Kanagaraj, G.; Sudhakar, K. Mechanical property of FDM printed ABS: Influence of printing parameters. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 2779–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Khodaei, M.; Xiang, H.; Baniassadi, M.; Abrinia, K.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M.; Baghani, M. 3D printed elastomers with superior stretchability and mechanical integrity by parametric optimization of extrusion process using Taguchi Method. Mater. Res. Express 2025, 12, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Gold, S.A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: II. Materials, dimensional accuracy, and surface roughness. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Compel, W.S.; Lewicki, J.P.; Tortorelli, D.A. Optimal design of fiber reinforced composite structures and their direct ink write fabrication. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 353, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valino, A.D.; Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H., Jr.; Chen, Q.; Messman, J.; Advincula, R.C. Advances in 3D printing of thermoplastic polymer composites and nanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 98, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, C.; Carnelli, D.; Tervoort, E.; Studart, A.R. 3D Printing of Emulsions and Foams into Hierarchical Porous Ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 9993–9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Arrieta-Escobar, J.A.; Hassan, A.; Zaman, U.K.U.; Siadat, A.; Yang, G. Optimizing Process Parameters of Direct Ink Writing for Dimensional Accuracy of Printed Layers. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 10, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevcik, M.J.; Bjerke, G.; Wilson, F.; Kline, D.J.; Morales, R.C.; Fletcher, H.E.; Guan, K.; Grapes, M.D.; Seetharaman, S.; Sullivan, K.T.; et al. Extrusion parameter control optimization for DIW 3D printing using image analysis techniques. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloo, S.; Kumar, M.; Lakshmi, N. A Modified Whale Optimization Algorithm Based Digital Image Watermarking Approach. Sens. Imaging 2020, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yun, J.; Kim, S.I.; Ryu, W. Maximising 3D printed supercapacitor capacitance through convolutional neural network guided Bayesian optimisation. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2022, 18, e2150231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Su, X. Moire Effect in PMP Using DLP and Its Influence on Phase Measurement. J. Sichuan Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2003, 40, 882–887. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, M.; Hu, L.; Dong, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, K.; Wang, D. Modeling and spatio-temporal optimization of grayscale digital light processing 3D-printed structures with photobleaching resins. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 99, 104659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.M.; Demoly, F.; Zhou, K.; Qi, H.J. Pixel-Level Grayscale Manipulation to Improve Accuracy in Digital Light Processing 3D Printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Ha, C.W. Strategy for minimizing deformation of DLP 3D printed parts using sub-build plate. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 2340–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xiong, G.; Fang, Q.; Shen, Z.; Wang, D.; Dong, X.; Wang, F.Y. A Dual Neural Network for Defect Detection With Highly Imbalanced Data in 3-D Printing. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 8078–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; He, X.; Li, H.; Ye, H.; Yang, X.; Wei, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Centrifugal multimaterial 3D printing of multifunctional heterogeneous objects. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jackson, J.A.; Ge, Q.; Hopkins, J.B.; Spadaccini, C.M.; Fang, N.X. Lightweight Mechanical Metamaterials with Tunable Negative Thermal Expansion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 175901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yang, C.; Fang, N.X.; Lee, H. Rapid multi-material 3D printing with projection micro-stereolithography using dynamic fluidic control. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, W.; Mille, L.S.; Ching, T.; Luo, Z.; Tang, G.; Garciamendez, C.E.; Lesha, A.; Hashimoto, M.; Zhang, Y.S. Digital Light Processing Based Bioprinting with Composable Gradients. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, 2107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, C.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Chen, Y.W.; Wang, F.M. Mechanical performance and aging resistance analysis of zinc oxide-reinforced polyurethane composites. Rsc Adv. 2025, 15, 28358–28366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembecka-Wójciga, K.; Jankowska, M.; Lepcio, P.; Sevriugina, V.; Korčušková, M.; Czeppe, T.; Zubrzycka, P.; Ortyl, J. Optimization of Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticle-Enhanced Photocurable Resins for High-Resolution 3D Printing Ceramic Parts. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2400951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Xing, H.; Sun, Q.; Xu, J. Three-Dimensional Printing of Large Objects with High Resolution by Dynamic Projection Scanning Lithography. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Liu, P.; Quoc Bui, T.; Duan, H. Shape memory polymers structure with different printing direction: Effect of fracture toughness. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 127, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajurahim, N.A.N.; Mahmood, S.; Ngadiman, N.H.A.; Sing, S.L. Biomaterials for tissue engineering scaffolds: Balancing efficiency and eco-friendliness through life cycle assessment. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 16, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Hong, Y.; Liang, R.; Zhang, X.; Liao, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, C.; Peng, Z.; et al. Rapid printing of bio-inspired 3D tissue constructs for skin regeneration. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; et al. One-Step Digital Light Processing 3D Printing of Robust, Conductive, Shape-Memory Hydrogel for Customizing High-Performance Soft Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 68131–68143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhong, J.; Weng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Z.; Miao, J. 3D Printing Mechanically Robust and Transparent Polyurethane Elastomers for Stretchable Electronic Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 6479–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.C.; Chen, L.H.; Chu, C.P.; Chao, W.C.; Liao, Y.C. Photo curable resin for 3D printed conductive structures. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, B.; Frey, M.; Raouf Fahmy, A.; Scharla, M.V.; Hanemann, T. Development of a Multi-Material Stereolithography 3D Printing Device. Micromachines 2020, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curti, C.; Kirby, D.J.; Russell, C.A. Stereolithography Apparatus Evolution: Enhancing Throughput and Efficiency of Pharmaceutical Formulation Development. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taormina, G.; Sciancalepore, C.; Messori, M.; Bondioli, F. 3D printing processes for photocurable polymeric materials: Technologies, materials, and future trends. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2018, 16, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra Cascon, W.; Krishnamurthy, V.R.; Att, W.; Revilla Leon, M. 3D printing parameters, supporting structures, slicing, and post-processing procedures of vat-polymerization additive manufacturing technologies: A narrative review. J. Dent. 2021, 109, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.N.; Stefaniak, A.B.; Knepp, A.K.; LeBouf, R.F.; Martin, S.B.J., Jr.; Ranpara, A.C.; Burns, D.A.; Virji, M.A. Potential for Exposure to Particles and Gases throughout Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing Processes. Buildings 2022, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanna, M.; Binder, K.W.; Murphy, S.V.; Kim, J.; Qasem, S.A.; Zhao, W.; Tan, J.; El Amin, I.B.; Dice, D.D.; Marco, J.; et al. In Situ Bioprinting of Autologous Skin Cells Accelerates Wound Healing of Extensive Excisional Full-Thickness Wounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbelen, L.; Dadbakhsh, S.; Van den Eynde, M.; Strobbe, D.; Kruth, J.P.; Goderis, B.; Van Puyvelde, P. Analysis of the material properties involved in laser sintering of thermoplastic polyurethane. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 15, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chu, M.; Hariri, F.; Vedula, G.; Naguib, H.E. Binder Jetting Fabrication of Highly Flexible and Electrically Conductive Graphene/PVOH Composites. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, B.; Schoen, M.A.W.; Trudel, S.; Qureshi, A.J.; Mertiny, P. Rheology-Assisted Microstructure Control for Printing Magnetic Composites-Material and Process Development. Polymers 2020, 12, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Liao, K.W.; Lin, C.C.; Tsai, M.C.; Cheng, C.W. Predicting magnetic characteristics of additive manufactured soft magnetic composites by machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 114, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Ning, J.; Xin, B.; Dun, Y.; Yan, W. Manipulating molten pool dynamics during metal 3D printing by ultrasound. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2022, 9, 021416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fei, C.; Yang, S.; Hou, C.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wu, H.; Quan, Y.; Zhao, T.; et al. Coding Piezoelectric Metasurfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2209173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Yu, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, J.; Xu, L.; Li, N.; Xu, J. Mxene hybrid conductive hydrogels with mechanical flexibility, frost-resistance, photothermoelectric conversion characteristics and their multiple applications in sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 3DP | Printing Accuracy | Material Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material extrusion (MEX) | DIW | 100–250 μm | Silicone Rubber, Hydrogel, PU Resin, elastomer composite materials | User-friendly operation, strong design capabilities, complex multi-scale architecture, low cost | The preparation of printing inks with high rheology is required, which have low printing resolution and flow channels prone to clogging | [14,39,40,41,42,43,44] |

| FDM | TPU (thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer), TPE (Thermoplastic Elastomer), Flexible PLA, Soft PLA | Multi-material structures, low-cost materials, complex structures | The printable material range is narrow, printing speed is fast, surfaces between layers are rough, and flow channels are prone to clogging | [45,46,47] | ||

| Vat photopoly-merization (VPP) | DLP | 10–100 μm | Standard Flexible, Elastic Resin Rubber-Like Resin | High resolution, fast printing speed, large build volume, wide material range, high precision, and high accuracy | High process costs, material limitations, and limited availability of photocurable flexible materials | [48,49,50] |

| SLA | Simple, fast manufacturing with high precision, capable of producing complex structures with numerous detailed features | Post-processing is required, the slurry requires high viscosity, and there are few photo-curable flexible materials available | [51,52] | |||

| Other | PBF | 50–200 μm | TPUpowder, Thermoplastic polyamide elastomer, Blended Powders | Low cost, no need for supporting materials | Inhalation risk, rough surfaces requiring complex post-processing, messy powder residue, and high costs | [53,54,55] |

| BJT | 50–150 μm | TPU Flexible polyurethane resin, nylon powder, flexible adhesive | High production efficiency, no supporting structures required, and relatively low cost | The anisotropy of the sample is significant, limiting material selection | [56,57,58] | |

| Multi-technology | SLA/ other | 25–500 μm | PDMS | Complex processes, require different processes tailored to various materials | 3D printing has the capability to manufacture complex shapes and enable customization, while conventional or other technologies provide high resolution, material properties, or functional characteristics | [59] |

| UV/ DIW | 5–580 μm | Silicone Rubber | [60,61,62,63] | |||

| FDM/electrospinning | ---- | PCL | [64] | |||

| Material Type | 3D Printing | Application Scenarios | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermoplastic flexible materials | TPU, TPS SBS, TPC TPA, PEBA | FDM FFF SLS | Functional components, footwear and apparel, soft robots, industrial parts | High elasticity and flexibility; High wear resistance and fatigue resistance; Strong functionality and good overall resilience; Diverse wire options | Poor long-term creep resistance; Limited high temperature resistance; The difficulty of printing is high; Yilasi, precision control is difficult; Supporting is extremely difficult to handle; Poor surface finish | [145,146,150,159,162,163] |

| Light-cured flexible resin material | PUA, PEGDA UV-PDMS, PC, Silicone Resin, NBR, epoxy resin, PI, etc. | DLP SLA | Medical models, precision components | Extremely high printing accuracy; The printing speed is fast; No need to deal with mechanical feeding issues | Insufficient durability; Poor long-term stability, prone to aging; The post-processing procedure is cumbersome and poses hygiene risks; The material cost is relatively high | [168,169,170,171,172,173,174] |