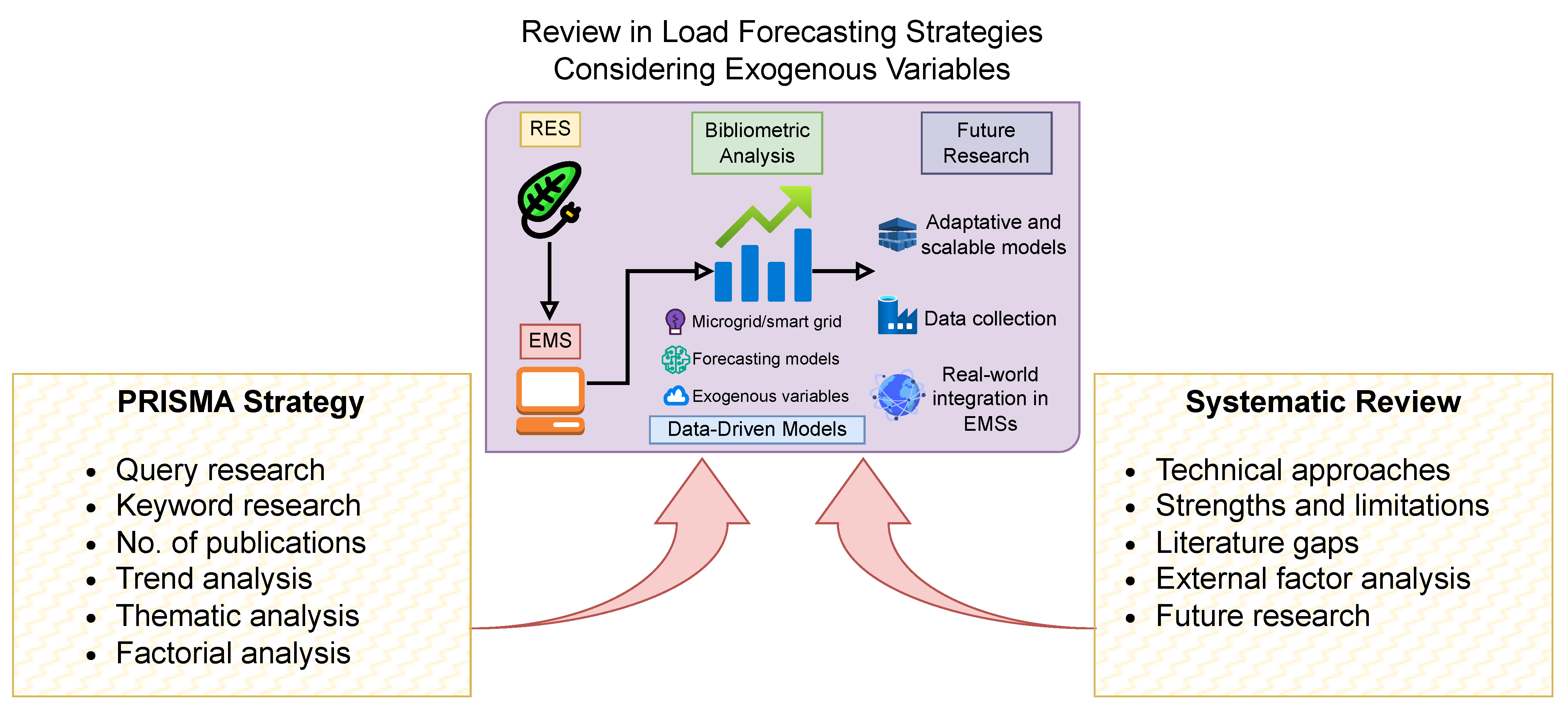

Data-Driven Load Forecasting in Microgrids: Integrating External Factors for Efficient Control and Decision-Making

Abstract

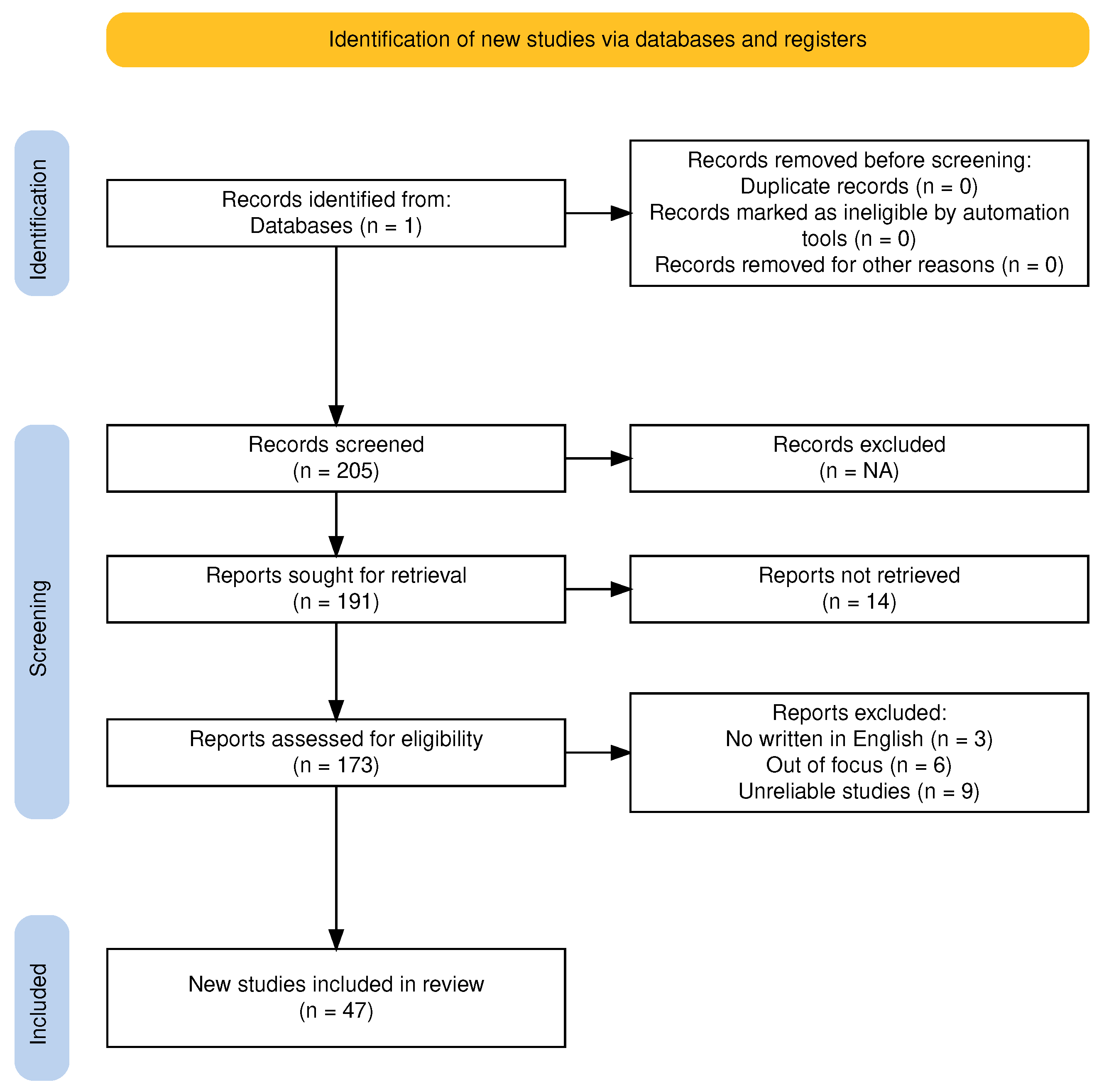

1. Introduction

2. Related Review Articles

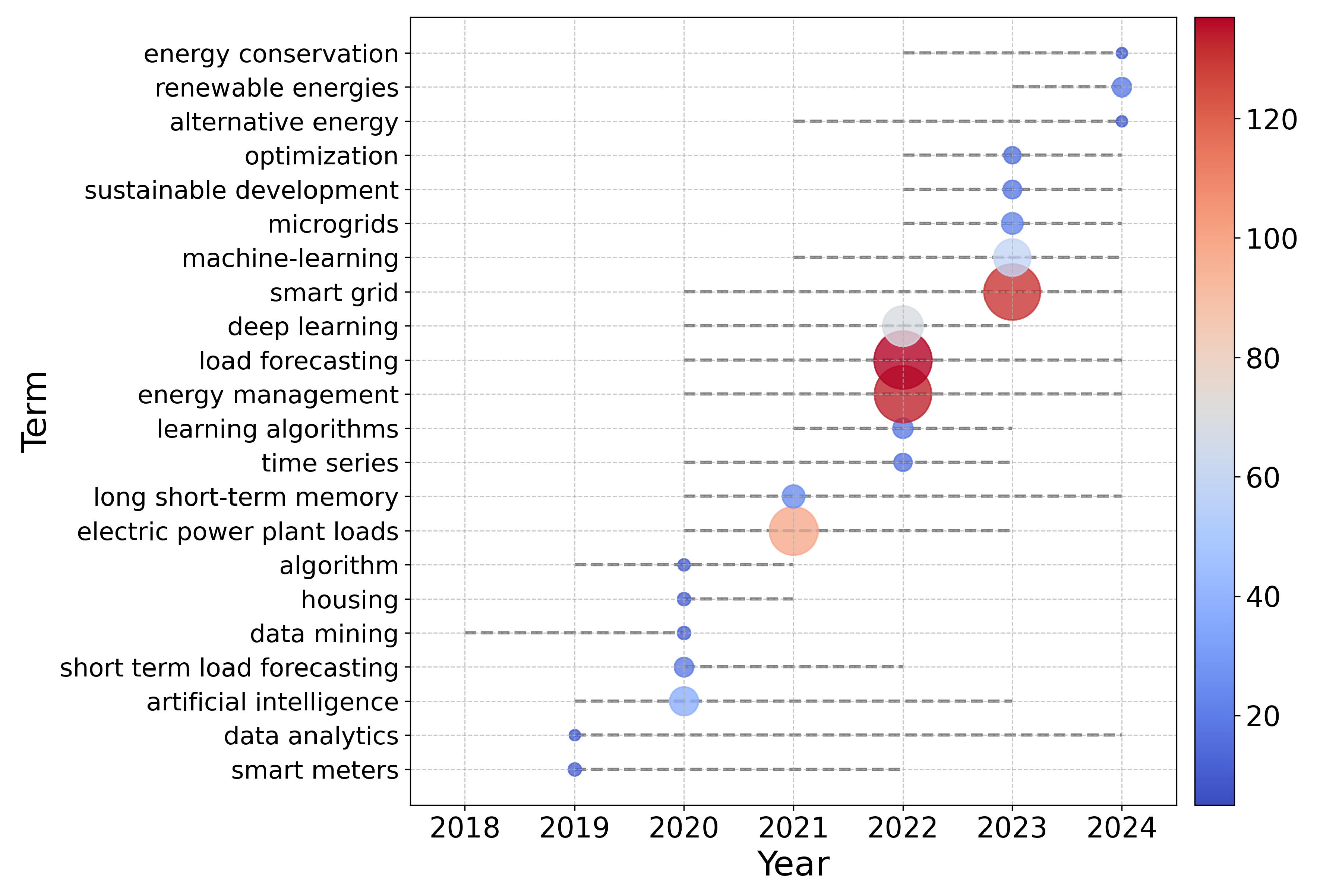

3. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1. Trend Topics Analysis

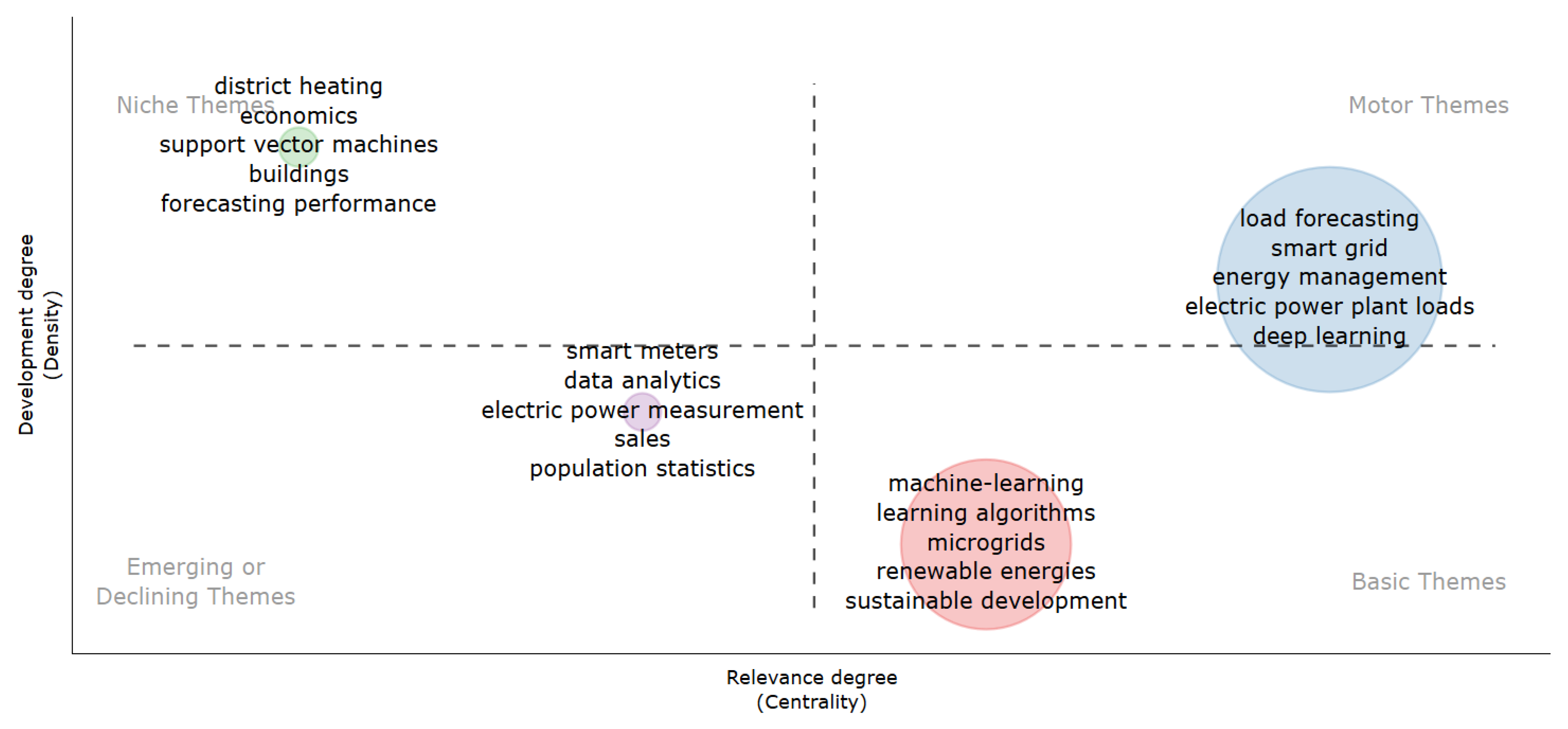

3.2. Thematic Analysis

- (i)

- Niche themes, located in the upper left quadrant, exhibit a high degree of development but relatively low relevance. They are specialized and well-developed research areas, yet not central to the overall research field. Notable topics in this quadrant include “district heating”, “economics”, “support vector machines”, “buildings”, and “forecasting performance”. These areas are highly specialized and well-developed, often yielding cutting-edge advances within their respective niches.

- (ii)

- Motor themes, found in the upper right quadrant, are characterized by both high centrality and high density, which indicates that they are conceptually well developed and strongly connected to other themes in the field, making them the main drivers of the research field. Keywords such as “load forecasting”, “smart grid”, “energy management”, “electric power plant loads”, and “deep learning” exhibit high centrality, meaning they serve as key drivers of progress in the field. Additionally, they present medium-to-high density, which suggests that the number of studies addressing these topics is increasing. This highlights their strategic importance and potential for continued growth within the domain.

- (iii)

- Emerging or declining themes, located in the lower left quadrant of the thematic map, are characterized by low development and low relevance. This behavior can be interpreted as emerging or declining themes. That is, new themes with few citations but potential for growth correspond to emerging themes. In contrast, more general topics that are not the focus of research and no longer generate citations, but instead represent more conceptual and well-known ideas, correspond to declining themes. The thematic map of load forecasting for electrical microgrids reveals emerging or declining themes, with terms such as “smart meters”, “data analysis”, “electric energy measurement”, “sales”, and “population statistics” appearing with low frequency. Themes such as data analysis and sales are considered declining topics in load forecasting due to the maturity of data-driven methodologies and the emergence of advanced tools. Smart meters and electric energy measurement are emerging topics, with smart meters gaining importance due to their role in data collection and in enabling advanced EMSs in smart grids. Electric energy measurement remains relevant, but it is evolving as newer technologies, such as IoT sensors and smart meters, gain precedence.

- (iv)

- Basic themes, located in the lower right quadrant, have high relevance but a lower degree of development. They are fundamental to the field and represent well-developed and mature tools that underpin research; however, they are not the main drivers of new explorations in the research field. This quadrant includes topics such as “machine learning”, “learning algorithms”, “microgrids”, “renewable energies”, and “sustainable development”. These areas are fundamental and vital for developing sustainable and intelligent energy systems.

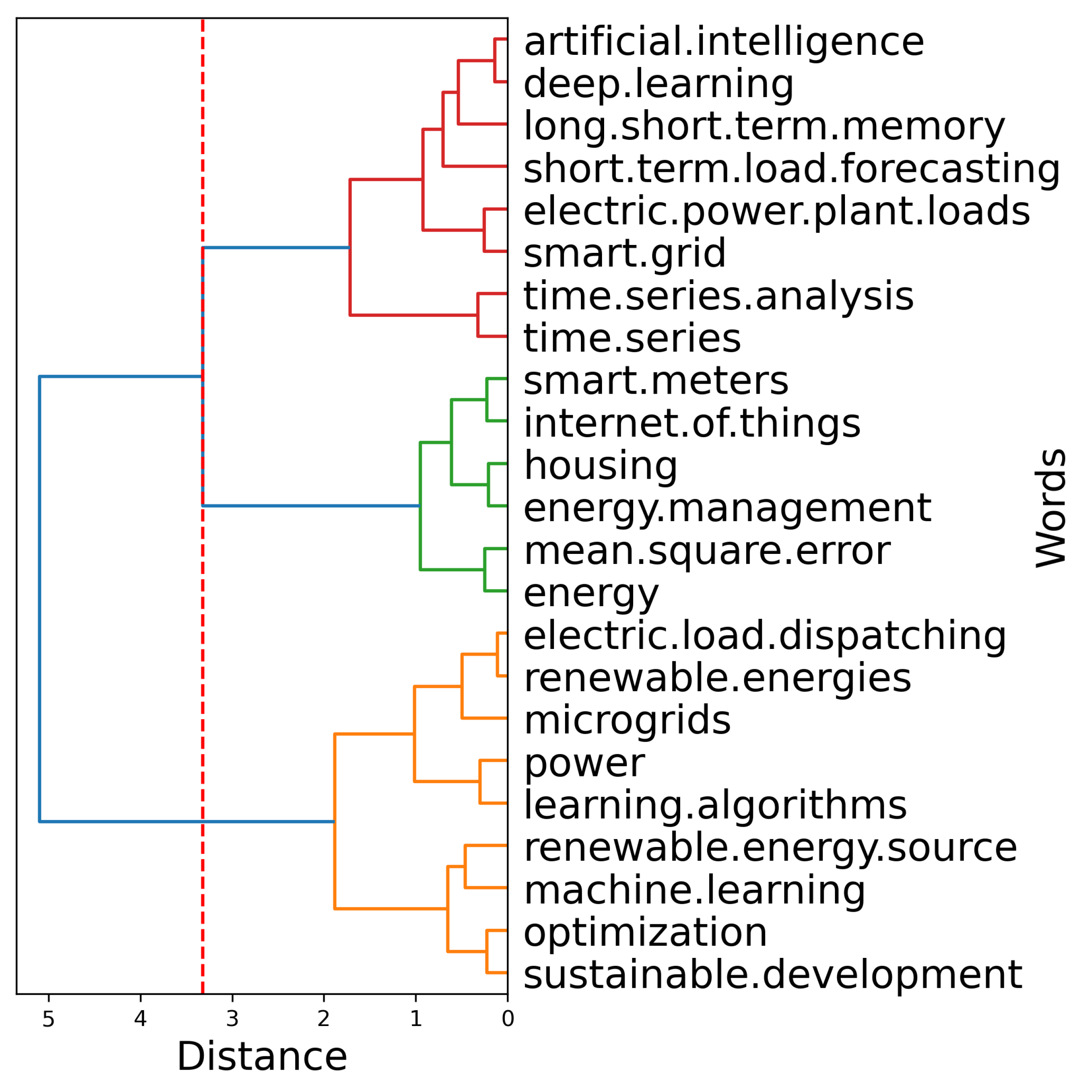

3.3. Factorial Analysis

- (i)

- The red cluster focuses on advanced computational methods and technologies for load forecasting. Keywords such as “artificial intelligence”, “deep learning”, “long-short-term memory”, “short-term load forecasting”, “electric power plant loads”, “smart grid”, “time-series analysis”, “smart meters”, and “internet of things” emphasize an intense research focus on applying ML techniques to improve load forecasting. Additionally, the integration of the smart grid and IoT underscores the importance of combining these technologies with smart grid infrastructure to enhance data collection, prediction accuracy, and control.

- (ii)

- The green cluster centers on EMSs and evaluation metrics. Keywords such as “housing”, “energy management”, “mean square error”, “energy”, and “electric load dispatching” indicate research on practical aspects of EMSs and the optimization of electric load dispatching. The use of mean squared error suggests a focus on evaluating model forecast accuracy using this statistical measure.

- (iii)

- The orange cluster addresses RESs, microgrids, and optimization techniques. Keywords such as “renewable energies”, “microgrids”, “power”, “learning algorithms”, “renewable energy source”, “machine learning”, “optimization”, and “sustainable development” indicate the research field focuses on integrating RESs into microgrids and using ML techniques. Terms such as sustainable development and optimization further underscore efforts to achieve sustainable EMS practices through modern data-driven mechanisms.

3.4. Summary and Implications of the Bibliometric Analysis

- (i)

- Growing prominence of AI-based techniques: Terms such as “machine learning”, “deep learning”, and “long short-term memory” show strong upward trends, confirming a shift from traditional statistical models toward more flexible and adaptable, data-driven approaches.

- (ii)

- Sustainability as a central theme: Terms such as “renewable energies”, “sustainable development”, and “optimization” highlight the importance of coordinating forecasting activities with more general sustainability goals.

- (iii)

- Persistent relevance of core concepts: The fact that topics such as “load forecasting”, “smart grid”, and “energy management” are constantly at the forefront shows how fundamental they are to this field.

- (iv)

- Underexplored areas: The term “computational complexity” is missing in the factorial analysis and thematic maps, which indicates a lack of computational complexity characterization in the development of more sophisticated load forecasting approaches.

- (v)

- Interdisciplinary integration: Clustering patterns underscore the necessity for cross-disciplinary collaboration by revealing how several domains (including housing, economics, optimization, and IoT) converge in the load forecasting research field.

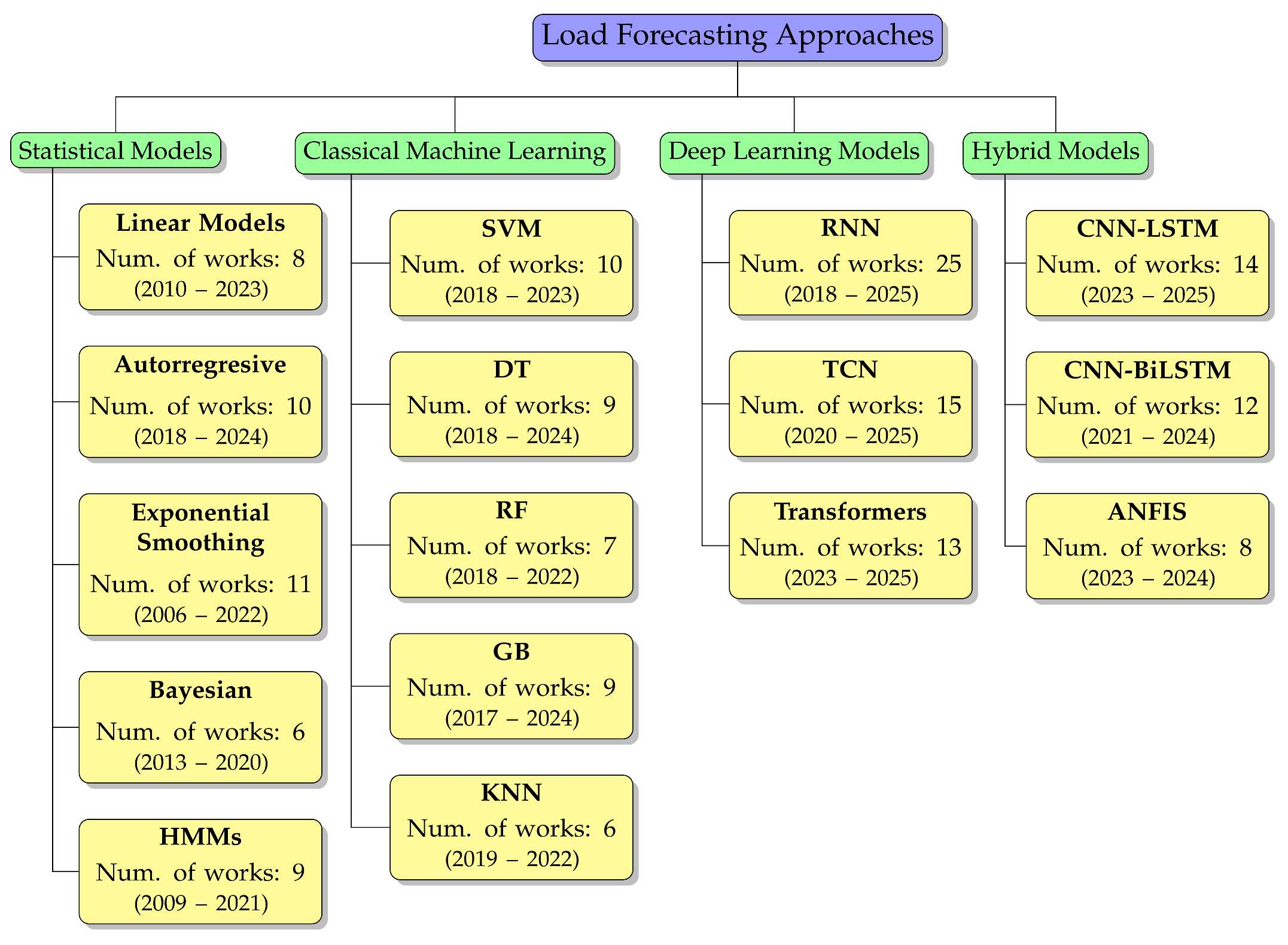

4. Load Forecasting Strategies

- (i)

- Traditional statistical models, which include time-series approaches such as ARIMA, exponential smoothing, and linear regression techniques that rely on historical demand data and often assume linear or stationary behavior;

- (ii)

- Classical machine learning techniques, which introduce more flexible, data-driven algorithms like DT, SVM, and ensemble methods that do not require strong assumptions about the data distribution; and

- (iii)

- Deep learning and hybrid models, which encompass advanced architectures such as LSTM, CNN, and hybrid systems that combine AI with traditional statistical models to model nonlinear, high-dimensional, and dynamic energy systems more effectively.

4.1. Traditional Statistical Models

4.2. Classical Machine Learning Models

4.3. Advanced Load Forecasting Methods

4.3.1. Deep Learning Models

4.3.2. Hybrid Models

5. Influence of Exogenous Variables on Load Forecasts in Microgrids

5.1. Remaining Challenges and Future Research Avenues

5.1.1. Standardization of Databases

5.1.2. Characterization of the Computational Complexity

5.1.3. Challenges in Extending and Generalizing Forecasting Models

5.1.4. Practical Implementation of the Load/Demand Forecasting Models in Real-World Scenarios

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lanka, V.V.S.; Roy, M.; Suman, S.; Prajapati, S. Renewable Energy and Demand Forecasting in an Integrated Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2021 Innovations in Energy Management and Renewable Resources (52042), Kolkata, India, 5–7 February 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jin, X.; Shi, P.; Chew, X. Real-time load forecasting model for the smart grid using bayesian optimized CNN-BiLSTM. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1193662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachache, R.; Labrahmi, M.; Grilo, A.; Chaoub, A.; Bennani, R.; Tamtaoui, A.; Lakssir, B. Energy Load Forecasting Techniques in Smart Grids: A Cross-Country Comparative Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.Y.; Aurangzeb, S.; Aleem, M.; Chilwan, A.; Awais, M. Demand-side load forecasting in smart grids using machine learning techniques. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onteru, R.R.; Sandeep, V. An intelligent model for efficient load forecasting and sustainable energy management in sustainable microgrids. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călin, A.-M.; Cotfas, D.T.; Cotfas, P.A. A Review of Smart Photovoltaic Systems Which Are Using Remote-Control, AI, and Cybersecurity Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbak, H.; Mahmoud, M.; Metwally, K.; Fouda, M.M.; Ibrahem, M.I. Load Forecasting Techniques and Their Applications in Smart Grids. Energies 2023, 16, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Islam, S.N.; Mahmud, M.A.; Haque, M.E.; Dong, Z.Y. Energy forecasting in smart grid systems: Recent advancements in probabilistic deep learning. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 4461–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Koukaras, P.; Tsalikidis, N.; Ioannidis, D.; Tjortjis, C. Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques and Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Ismail, I.; Jameel, S.M.; Romlie, F.; Danyaro, K.U.; Shukla, S. Deterioration of Electrical Load Forecasting Models in a Smart Grid Environment. Sensors 2022, 22, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro-Costas, M.; Villanueva, D.; Eguía-Oller, P.; Martínez-Comesaña, M.; Ramos, S. Load Forecasting with Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, W.; Zheng, X. A Deep Learning Method for Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting in Smart Grid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 55785–55797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Yu, C.; Liu, X.; Yuan, K.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J. A novel data-driven multi-energy load forecasting model. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 955851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Saga, R.; Cai, H.; Ma, Z.; Yu, S. Advanced Integration of Forecasting Models for Sustainable Load Prediction in Large-Scale Power Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Lin, Y.; Wang, R.; Fan, Y. Review of multiple load forecasting method for integrated energy system. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1296800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.; Araújo, G.; Moraes, R.; Vasques, F.; Portugal, P. Short-Term Electrical Demand Forecast Modeling Considering External Influences: A Comprehensive Study. Preprints 2024, 2024061550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, J.O.; Piepho, H.P.; Schulz-Streeck, T. A comparison of random forests, boosting and support vector machines for genomic selection. BMC Proc. 2011, 5, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Baratchi, M.; Bäck, T.; Hoos, H.H.; Limmer, S.; Olhofer, M. Towards Time-Series Feature Engineering in Automated Machine Learning for Multi-Step-Ahead Forecasting. Eng. Proc. 2022, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M.; Wang, J. Deep learning-based feature engineering methods for improved building energy prediction. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, K.; Marino, D.L.; Manic, M. Deep neural networks for energy load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Edinburgh, UK, 19–21 June 2017; pp. 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Electric load forecasting in smart grids using Long-Short-Term-Memory based Recurrent Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 51st Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 22–24 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohan, M.J.A.; Faruque, M.O.; Foo, S.Y. Forecasting of Electric Load Using a Hybrid LSTM-Neural Prophet Model. Energies 2022, 15, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.M.; Megahed, A.I.; Abbasy, N.H. Short-Term Individual Household Load Forecasting Framework Using LSTM Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), Ankara, Turkey, 21–23 October 2021; pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalaq, A.; Edwards, G. A Review of Deep Learning Methods Applied on Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Cancun, Mexico, 18–21 December 2017; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, N.; Kütt, L.; Raja, H.A.; Ahmadiahangar, R.; Rosin, A.; Husev, O. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for Residential Load Forecasting: A Comparative Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 62nd International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University (RTUCON), Riga, Latvia, 15–17 November 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Liao, J.; Niu, Q.; Shen, N.; Bao, Y. Deep learning-driven hybrid model for short-term load forecasting and smart grid information management. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oqaibi, H.; Bedi, J. A data decomposition and attention mechanism-based hybrid approach for electricity load forecasting. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 4103–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, W.; Wang, F. Hybrid Decomposition-Deep Learning Model for Energy Load Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th Eurasia Conference on IOT, Communication and Engineering (ECICE), Yunlin, Taiwan, 27–29 October 2023; pp. 557–562. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, V.S.K.; Saravanan, T.; Velusudha, N.T.; Selwyn, T.S. Smart Grid Management System Based on Machine Learning Algorithms for Efficient Energy Distribution. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 387, 02005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Biswas, P.; Al Nasim, M.D.A.; Gupta, K.D. Power Plays: Unleashing Machine Learning Magic in Smart Grids. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Vlasov, A.; Selivanov, K.; Muraviev, K.; Shakhnov, V. Prospects and Challenges of the Machine Learning and Data-Driven Methods for the Predictive Analysis of Power Systems: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Nishtar, Z. Real-Time Load Forecasting and Adaptive Control in Smart Grids Using a Hybrid Neuro-Fuzzy Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Shojaeighadikolaei, A.; Hashemi, M. Combating Uncertainties in Wind and Distributed PV Energy Sources Using Integrated Reinforcement Learning and Time-Series Forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, E.; Yaghoubi, E.; Maghami, M.R.; Rahebi, J.; Zareian Jahromi, M.; Ghadami, R.; Yusupov, Z. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Model Predictive Control in Microgrids: Moving Beyond Traditional Methods. Processes 2025, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.R.N.; Lengua, M.A.C. Predicting demand in changing environments: A review on the use of reinforcement learning in forecasting models. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2025, 14, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinzadeh, H.; Sadrarhami, H.; Hayati, M.M.; Majidi-Gharehnaz, H.; Abapour, M.; Gharehpetian, G.B. Review and Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Techniques for Smart Grid Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th CSI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP), Babol, Iran, 21–22 February 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardabili, S.; Mosavi, A.; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R. Advances in Machine Learning Modeling Reviewing Hybrid and Ensemble Methods. In Engineering for Sustainable Future; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, R.; Cui, C.; Towey, D.; Zhou, L.; Tian, J.; Wang, J. Short-Term Electricity-Load Forecasting by Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.16202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, K.; Abbasi, U.; Adnan, M.; Iqbal, S.; Gasim Mohamed, S.E. A comprehensive survey on load forecasting hybrid models: Navigating the Futuristic demand response patterns through experts and intelligent systems. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Bhandari, B.; Cheng, L. AI-empowered methods for smart energy consumption: A review of load forecasting, anomaly detection and demand response. Int. J. Precis. Eng.-Manuf.-Green Technol. 2024, 11, 963–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal, L.G.; Bennekrouf, M.; Bettayeb, B.; Sahnoun, M. Technologies and strategies for optimizing the potato supply chain: A systematic literature review and some ideas for application in the algerian context. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 234, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Mifta, Z.; Papiya, S.J.; Roy, P.; Dey, P.; Salsabil, N.A.; Chowdhury, N.U.R.; Farrok, O. A state-of-the-art comparative review of load forecasting methods: Characteristics, perspectives, and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Cheng, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. Advancing regional heat load forecasting through sophisticated data-driven methodologies integrated with robust adversarial training strategies. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, V.K.Z.; Li, Y.; Kek, X.Y.; Shafiee, E.; Lin, Z.; Wen, B. A review of recent hybridized machine learning methodologies for time series forecasting on water-related variables. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 132909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Azami, M.W.; Wahyudi Farid, I.; Priananda, C.W.; Musthofa, A. Electric Load Forecasting On Smart Energy Meter (SEM) Using Linear Regression. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronics, Intelligent Manufacture and Industrial Automation (ICAMIMIA), Surabaya, Indonesia, 14–15 November 2023; pp. 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supapo, K.R.M.; Santiago, R.V.M.; Pacis, M.C. Electric load demand forecasting for Aborlan-Narra-Quezon distribution grid in Palawan using multiple linear regression. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 9th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Manila, Philippines, 1–3 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Sharma, A. A Comparison of Short-Term Load Forecasting Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Singapore, 22–25 May 2018; pp. 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getanda, V.B.; Kihato, P.K.; Hinga, P.K.; Oya, H. Grey and Linear Regression Models in Load Forecasting for Enhanced Smart Grid Management-Smart Grid Modelling. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica, Nairobi, Kenya, 23–27 August 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, A.; Carpinelli, G.; De Falco, P.; Hong, T. Short-term industrial load forecasting: A case study in an Italian factory. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Turin, Italy, 26–29 September 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.Y.; Alam, A.K.M.R. Short term load forecasting using multiple linear regression for big data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 November–1 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Gui, M.; Baran, M.E.; Willis, H.L. Modeling and forecasting hourly electric load by multiple linear regression with interactions. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES General Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 25–29 July 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Quanming, Z.; Qiang, Y.; Ruiguang, M.; Mi, Z.; Wei, Y. A Medium and Long Term Load Characteristic Index Forecasting Method Considering Load Influencing Factors. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Chengdu, China, 23–25 November 2020; pp. 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Kaitwade, N.; Seraphim, B.I. Power Consumption Forecast for Load Management in Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Recent Trends in Advance Computing (ICRTAC), Chennai, India, 14–15 December 2023; pp. 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, J.; Ezzine, L.; Aman, Z.; Moussami, H.E.; Lachhab, A. Forecasting of demand using ARIMA model. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 1847979018808673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inala, K.P.; Gaddam, S.; Etti, S.; Kashetty, P.; Karangula, J.; Anaparthi, N. Machine Learning Algorithms for Load Forecasting in Smart Grid. In Proceedings of Third International Symposium on Sustainable Energy and Technological Advancements; Panda, G., Basu, M., Siano, P., Affijulla, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmanini, C.; Sarma, N.; Gezegin, C.; Ozgonenel, O. Short term load forecasting based on ARIMA and ANN approaches. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, C.; Rodríguez, F.; Moreno, J.C.; Da Costa Mendes, P.R.; Normey-Rico, J.E.; Guzmán, J.L. The Comparison Study of Short-Term Prediction Methods to Enhance the Model Predictive Controller Applied to Microgrid Energy Management. Energies 2017, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, M.; Hair, A. Empowering Smart Cities: SARIMA Forecasting of Power Consumption in Tetouan’s Urban Grid. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Fez, Morocco, 16–17 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforov, C.; Arghira, N.; Stamatescu, G.; Stamatescu, I.; Făgărăsan, I.; Iliescu, S.S. Efficient Load Forecasting Model Assessment for Embedded Building Energy Management Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics (AQTR), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 19–21 May 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Dubey, A.; Kumar, A.; García-Díaz, V.; Kumar Sharma, A.; Kanhaiya, K. Study and analysis of SARIMA and LSTM in forecasting time series data. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedrowski, R.; Nelson, J.; Nair, A.S.; Ranganathan, P. Short-Term Seasonal Energy Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology (EIT), Rochester, MI, USA, 3–5 May 2018; pp. 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Jalil, N.A.; Ahmad, M.H.; Mohamed, N. Electricity load demand forecasting using exponential smoothing methods. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 22, 1540–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.W.; Snyder, R.D. Forecasting intraday time series with multiple seasonal cycles using parsimonious seasonal exponential smoothing. Omega 2012, 40, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özger, Y.E.; Akpınar, M.; Musayev, Z.; Yaz, M. Elektrik Yükünün Genetik Algoritma Temelli Holt-Winters Üstel Düzeltme Yönteminiyle Tahmini. Sak. Univ. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 2, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, A.; Ali, R.F.; Almaghthawi, A.; Taib, S.M.; Alghamdi, A.; Ghaleb, E.A.A. Short term residential load forecasting using long short-term memory recurrent neural network. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 12, 5589–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Li, Y.; Dong, S.; Lu, X.; Ye, H.; Hu, B. Short Term Load Forecasting for Holidays Based on Exponential Smoothing of Correlative Correction. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon), Jinan, China, 21–22 September 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Xiong, D.; Wang, P.; Chen, J. A Study on Exponential Smoothing Model for Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2012 Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Shanghai, China, 27–29 March 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrezak, L.; Mourad, M.; Djalel, D. Very short-term electricity demand forecasting using adaptive exponential smoothing methods. In Proceedings of the 2014 15th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA), Hammamet, Tunisia, 21–23 December 2014; pp. 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetunkov, I.; Kourentzes, N.; Ord, J.K. Complex exponential smoothing. Nav. Res. Logist. (NRL) 2022, 69, 1108–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.F. Forecast modeling a time series of water reservoir levels using exponential smoothing method. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.05199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, G.; Liu, C.; Sahoo, D.; Kumar, A.; Hoi, S. ETSformer: Exponential Smoothing Transformers for Time-series Forecasting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.01381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.B.; Ha, S.K.; Park, J.W.; Kweon, D.J.; Kim, K.H. Hybrid load forecasting method with analysis of temperature sensitivities. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2006, 21, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, A.; Carpinelli, G.; De Falco, P. A Bayesian-based approach for the short-term forecasting of electrical loads in smart grids.: Part I: Theoretical aspects. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Capri, Italy, 22–24 June 2016; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, A.; Carpinelli, G.; De Falco, P. A Bayesian-based approach for the short-term forecasting of electrical loads in smart grids.: Part II: Numerical applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Capri, Italy, 22–24 June 2016; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.; Saguna, S.; Mitra, K.; Åhlund, C. BayesForSG: A bayesian model for forecasting thermal load in smart grids. In SAC ’16: Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Pisa, Italy, 4–8 April 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2135–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, A.; Caramia, P.; Carpinelli, G.; Di Fazio, A.R.; Varilone, P. A Bayesian-Based Approach for a Short-Term Steady-State Forecast of a Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 1760–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessani, M.; Massignan, J.A.; Santos, T.M.; London, J.B.; Maciel, C.D. Multiple households very short-term load forecasting using bayesian networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 189, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Park, J.; Kundur, D. Trends in Short-Term Renewable and Load Forecasting for Applications in Smart Grid. In Smart City 360°; Leon-Garcia, A., Lenort, R., Holman, D., Staš, D., Krutilova, V., Wicher, P., Cagáňová, D., Špirková, D., Golej, J., Nguyen, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.-x.; Kou, B.-e.; Zhang, Y.-y. Mid-long Term Load Forecasting Using Hidden Markov Model. In Proceedings of the 2009 Third International Symposium on Intelligent Information Technology Application, Nanchang, China, 21–22 November 2009; Volume 3, pp. 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henselmeyer, S.; Grzegorzek, M. Short-term load forecasting with discrete state Hidden Markov Models. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M. Modeling electricity load curves with hidden Markov models for demand-side management status estimation. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2017, 27, e2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roça, I.L.; Carvalho, P.M.S. Solving Ill-Conditioned State-Estimation Problems in Distribution Grids with Hidden-Markov Models of Load Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermias, J.P.; Teknomo, K.; Monje, J.C.N. Short-term stochastic load forecasting using autoregressive integrated moving average models and Hidden Markov Model. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies (ICICT), Karachi, Pakistan, 30–31 December 2017; pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, V.; Mazuelas, S.; Lozano, J.A. Probabilistic Load Forecasting Based on Adaptive Online Learning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3668–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Bhowmik, P.S. Hidden Markov Model Based Islanding Prediction in Smart Grids. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 4181–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, A.; Khan, M.R.A.; Michael, S.; Tonkoski, R. Forecasting Data Center Load Using Hidden Markov Model. In Proceedings of the 2018 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Fargo, ND, USA, 9–11 September 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Khan, Z.A.; Mujeeb, S.; Abbas, S.; Javaid, N. Short-Term Electricity Price and Load Forecasting using Enhanced Support Vector Machine and K-Nearest Neighbor. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth HCT Information Technology Trends (ITT), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirate, 20–21 November 2019; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebekhulu, E.; Onumanyi, A.J.; Isaac, S.J. Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Energy Demand–Supply Prediction in Smart Grids. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Fan, W.; Wang, Y.; Mo, W. Application of SVM Method with Meteorological Factors in Power Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Dali, China, 28–30 July 2023; pp. 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.S.; Prilepok, M.; Misak, S.; Snasel, V. Intelligent system for power load forecasting in off-grid platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 19th International Scientific Conference on Electric Power Engineering (EPE), Brno, Czech Republic, 16–18 May 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashawyah, D.A.; Qaisar, S.M. Machine Learning Based Short-Term Load Forecasting for Smart Meter Energy Consumption Data in London Households. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th International Conference on Electronics and Information Technologies (ELIT), Lviv, Ukraine, 19–21 May 2021; pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, J.; Javaid, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ullah, S.; Javaid, N. An Optimized Linear-Kernel Support Vector Machine for Electricity Load and Price Forecasting in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Advances in the Emerging Computing Technologies (AECT), Al Madinah Al Munawwarah, Saudi Arabia, 10 February 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathumitha, R.; Rathika, P.; Manimala, K. SVM-based regression for forecasting building power energy consumption using smart meter data. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Cheng, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z. Research on Medium-Long Term Power Load Forecasting Method Based on Load Decomposition and Big Data Technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Smart Grid and Electrical Automation (ICSGEA), Changsha, China, 9–10 June 2018; pp. 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Javaid, N.; Mangla, F.U.; Munir, M.; Ihsan, F.; Javaid, A.; Asif, M. An Approximate Forecasting of Electricity Load and Price of a Smart Home Using Nearest Neighbor. In Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems; Barolli, L., Hussain, F.K., Ikeda, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquthami, T.; Zulfiqar, M.; Kamran, M.; Milyani, A.H.; Rasheed, M.B. A Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Load Forecasting in Smart Grid. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 48419–48433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiboaca-Ciupageanu, M.E.; Costinas, S.; Ion, G.; Stan, A. Machine Learning Algorithms for Load Forecasting Based on Big Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on ENERGY and ENVIRONMENT (CIEM), Bucharest, Romania, 26–27 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, N.; Kang, C. Constructing Probabilistic Load Forecast From Multiple Point Forecasts: A Bootstrap Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Singapore, 22–25 May 2018; pp. 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Franchini, G.; Giangrande, P.; Mandelli, G.; Fenili, L. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Medium-Term Load Forecasting in Smart Commercial Building. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE), Oshawa, ON, Canada, 18–20 August 2024; pp. 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Cho, S.B. Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy 2019, 182, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaprakdal, F.; Bal, F. Comparison of Robust Machine-learning and Deep-learning Models for Midterm Electrical Load Forecasting. Eur. J. Tech. (EJT) 2022, 12, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, S.; Ţopa, V.; Cziker, A. Industrial load forecasting using machine learning in the context of smart grid. In Proceedings of the 2019 54th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Bucharest, Romania, 3–6 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzumdar, A.; Modi, C.; Vyjayanthi, C. An Efficient Regional Short-Term Load Forecasting Model for Smart Grid Energy Management. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 The 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Vadhera, S. Random Forest and Xgboost Technique for Short-Term Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Sustainable Technology for Power and Energy Systems (STPES), Srinagar, India, 4–6 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Zeng, X.; Kong, Y.; Sun, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Short-Term Load Forecasting for Industrial Customers Based on TCN-LightGBM. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Xu, Y.; Tang, X. Short-and mid-term load forecasting using machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2017 China International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Beijing, China, 25–27 October 2017; pp. 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, Z.; Gantassi, R.; Choi, Y. Enhancing Short-Term Electric Load Forecasting for Households Using Quantile LSTM and Clustering-Based Probabilistic Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 77257–77268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanthi, P.; Priyadarsini, K. A Comparative Study of the Performance of Machine Learning based Load Forecasting Methods. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems (ICAIS), Coimbatore, India, 25–27 March 2021; pp. 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, D.; Refaat, S.S.; Abu-Rub, H. Performance Evaluation of Distributed Machine Learning for Load Forecasting in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2020 Cybernetics & Informatics (K&I), Velke Karlovice, Czech Republic, 29 January–1 February 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, K.; Mittal, R.; Nisha; Tripathi, M.M. A Multi-Phase Ensemble Model for Long Term Hourly Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA), Bangkok, Thailand, 16–21 April 2020; pp. 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.Y.; Lai, C.C. Toward Improved Load Forecasting in Smart Grids: A Robust Deep Ensemble Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 4292–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Khan, Z.A.; Noshad, Z.; Javaid, S.; Javaid, N. Short Term Load and Price Forecasting using Tuned Parameters for K-Nearest Neighbors. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth HCT Information Technology Trends (ITT), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 20–21 November 2019; pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, T.; Javaid, N. Short-Term Electricity Load and Price Forecasting using Enhanced KNN. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan, 16–18 December 2019; pp. 266–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimal, S.; Javaid, N.; Islam, T.; Khan, W.Z.; Aalsalem, M.Y.; Sajjad, H. An Efficient CNN and KNN Data Analytics for Electricity Load Forecasting in the Smart Grid. In Web, Artificial Intelligence and Network Applications; Barolli, L., Takizawa, M., Xhafa, F., Enokido, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Kang, Z.; Fu, J. Deep Learning based Short Term Load Prediction in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Shenzhen, China, 13–15 November 2020; pp. 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Cao, Z.; Wan, C.; Xu, S. An Ensemble Wavelet Deep Learning Approach for Short-term Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Chengdu, China, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadlou, M.; Naderi, M.S.; Abedi, M.; Esmaeili, S.; Amini, M. A Comprehensive Deep Learning Method for Short-Term Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tehran, Iran, 17–19 May 2022; pp. 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semero, Y.K.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D.; Wei, D. An Accurate Very Short-Term Electric Load Forecasting Model with Binary Genetic Algorithm Based Feature Selection for Microgrid Applications. Electr. Power Components Syst. 2018, 46, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Ahmed, S.; Alamaniotis, M. Deep Neural Network Based Methodology for Very-Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), Corfu, Greece, 18–20 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradzadeh, A.; Moayyed, H.; Zakeri, S.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Aguiar, A.P. Deep Learning-Assisted Short-Term Load Forecasting for Sustainable Management of Energy in Microgrid. Inventions 2021, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Perez, J.M.; Perez-Juarez, M.A. An Insight of Deep Learning Based Demand Forecasting in Smart Grids. Sensors 2023, 23, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, W.; Xu, Q.; Aurangzeb, M.; Iqbal, S.; Dar, S.H.; Elbarbary, Z. Empowering data-driven load forecasting by leveraging long short-term memory recurrent neural networks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Yao, Z. A novel approach to predict buildings load based on deep learning and non-intrusive load monitoring technique, toward smart building. Energy 2024, 312, 133456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Hemamalini, S. Long short-term memory-based forecasting of uncertain parameters in an islanded hybrid microgrid and its energy management using improved grey wolf optimization algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 3640–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, P.; Rafiq, H.; Rodriguez-Ubinas, E.; Palpanas, T. New Forecasting Metrics Evaluated in Prophet, Random Forest, and Long Short-Term Memory Models for Load Forecasting. Energies 2024, 17, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fente, D.N.; Kumar Singh, D. Weather Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2018 Second International Conference on Inventive Communication and Computational Technologies (ICICCT), Coimbatore, India, 20–21 April 2018; pp. 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparin, A.; Lukovic, S.; Alippi, C. Deep learning for time series forecasting: The electric load case. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2022, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Zhou, K.; Yang, S. Load demand forecasting of residential buildings using a deep learning model. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 179, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Shao, H.; Ma, X.; de Silva, C.W. A Stacked GRU-RNN-Based Approach for Predicting Renewable Energy and Electricity Load for Smart Grid Operation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7050–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.; Arifin, Z.; Sudiarto, B.; Jufri, F.H.; Haramaini, Q.; Garniwa, I. Comparison of Medium-Term Load Forecasting Methods (Splitted Linear Regression and Artificial Neural Networks) in Electricity Systems Located in Tropical Regions. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Clean and Green Energy Engineering (CGEE), Istanbul, Turkey, 28–30 August 2022; pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaoudi, M.; Refaat, S.S.; Chihi, I.; Trabelsi, M.; Abu-Rub, H.; Oueslati, F.S. Short-Term Electric Load Forecasting Based on Data-Driven Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 The 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 2565–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Ullah, A.; Ul Haq, I.; Hamdy, M.; Maria Maurod, G.; Muhammad, K.; Hijji, M.; Baik, S.W. Efficient Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Effective Energy Management. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalou, I.; Mouhni, N.; Abdali, A. Multivariate time series prediction by RNN architectures for energy consumption forecasting. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, F.; Biswal, M. Medium-Term Load Forecasting Using ANN and RNN in Microgrid Integrating Renewable Energy Source. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON), Bangalore, India, 3–5 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaprakdal, F.; Varol Arısoy, M. A multivariate time series analysis of electrical load forecasting based on a hybrid feature selection approach and explainable deep learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Hu, W. Short-Term Load Forecasting for Community Battery Systems based on Temporal Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 17–19 December 2021; Volume 2, pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Jia, L. Temporal Convolutional Network Based Short-term Load Forecasting Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 9th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference (DDCLS), Liuzhou, China, 20–22 November 2020; pp. 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levikari, S.; Nykyri, M.; Kärkkäinen, T.J.; Honkapuro, S.; Silventoinen, P. Load Forecasting in Nordic Residential Buildings. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Lappeenranta, Finland, 6–8 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, S. Short-term load forecasting of power system based on time convolutional network. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Symposium on Next Generation Electronics (ISNE), Zhengzhou, China, 9–10 October 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chuan, L.; Jun, W.; Wei, S.; Yan, H.; Zhu, D.; Liu, F. Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Method Based on Time Convolutional Neural Network for HPLC High Frequency Data Acquisition. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Energy Systems and Electrical Power (ICESEP), Wuhan, China, 21–23 June 2024; pp. 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Wu, G.; Chen, H.; Xie, T.; Tang, X.; Wang, R. Application of temporal convolutional neural network combined with autoencoder in short-term bus load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Shanghai, China, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, K. Integrated Forecasting Models Based on LSTM and TCN for Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Control and Robotics (EECR), Wuhan, China, 24–26 February 2023; pp. 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z. Short-term Power Load Forecasting Based on Temporal Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Information, Control, and Communication Technologies (ICCT), Astrakhan, Russian, 3–7 October 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, L.; Scherer, R.; Woźniak, M.; Zhang, P.; Wei, W. Short-Term Load Forecasting Based on Adabelief Optimized Temporal Convolutional Network and Gated Recurrent Unit Hybrid Neural Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 66965–66981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, K.; Huang, R.; Lin, Q.; Xie, L. A novel method for the short-term power load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Power Electronics Systems and Applications (PESA), Hong Kong, 20–22 September 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Liu, Z.W. Short-Term Residential Load Forecasting Based on Smart Meter Data Using Temporal Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 5423–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, W.; Huo, C.; Bai, H.; Gao, J.; He, J.; Ma, S.; Liu, T. A Method of Load Forecasting Based on Temporal Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), Chengdu, China, 28–31 May 2021; pp. 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Chunguang, H.; Gang, Z. Medium and Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Based on Parallel Temporal Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 12th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems (ICPES), Guangzhou, China, 23–25 December 2022; pp. 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Si, C. Improved composite model using metaheuristic optimization algorithm for short-term power load forecasting. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, D. Electricity Load Forecasting Based on Patch Channel-Mixing Transformer Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Electronic Engineering and Informatics (EEI), Chongqing, China, 28–30 June 2024; pp. 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Short-term Forecasting of Multienergy Loads in Integrated Energy System Based on Improved Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 39th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Dalian, China, 7–9 June 2024; pp. 1389–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, W.; Luan, J. Improving Load Forecasting Accuracy through Data Augmentation and TCNs-Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Power System and Green Energy Conference (PSGEC), Shanghai, China, 22–24 August 2024; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, K. Probabilistic Multi-Energy Load Forecasting for Integrated Energy System Based on Bayesian Transformer Network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Yin, W. Short-Term Load Forecasting Method Based on Improved Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Smart Grids and Energy Systems (SGES), Zhengzhou, China, 25–27 October 2024; pp. 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, W.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Dai, L.; Chen, Z. Probabilistic Multienergy Load Forecasting Based on Hybrid Attention-Enabled Transformer Network and Gaussian Process-Aided Residual Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 8379–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Rehman, A.; Shah, H.A.; Diyan, M.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.M. SmartFormer: Graph-based transformer model for energy load forecasting. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 73, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J. Load Forecasting for Commercial Buildings Using BiLSTM–Transformer Network and Cyber–Physical Cognitive Control Systems. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Jose, B.A. Short Term Load Forecasting And Anomaly Detection in Residential Power Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Informatics, Communication and Energy Systems (SPICES), Kottayam, India, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, B. Vanilla Transformers are Transfer Capability Teachers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Crossformer: Transformer Utilizing Cross-Dimension Dependency for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Long, G.; Jiang, J.; Chang, X.; Zhang, C. Connecting the Dots: Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Hu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, X.; Alhazmi, M. Short-term electricity load forecasting based on large language models and weighted external factor optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao Huy, T.H.; Vo, D.N.; Nguyen, K.P.; Huynh, V.Q.; Huynh, M.Q.; Truong, K.H. Short-Term Load Forecasting in Power System Using CNN-LSTM Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 Asia Meeting on Environment and Electrical Engineering (EEE-AM), Hanoi, Vietnam, 13–15 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Han, L.; Qu, X. Bus Load Forecasting Based on Maximum Information Coefficient and CNN-LSTM Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing and Computer Applications (ICIPCA), Changchun, China, 11–13 August 2023; pp. 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Research on Short-Term Power Load Forecasting of CNN-LSTM Based on Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Science (EIECS), Changchun, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y. Electricity Load Forecasting Based on CNN-LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Automation and Computer Engineering (ICEACE), Changchun, China, 29–31 December 2023; pp. 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Ru, H.; Wang, G.; Fu, X.; Zhou, G.; Yang, C. Research on power load forecasting of PCA-CNN-LSTM based on sliding window. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on New Energy and Power Engineering (ICNEPE), Huzhou, China, 24–26 November 2023; pp. 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H. Power Load Forecasting Based on CNN-LSTM Combination Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Image Processing and Computer Applications (ICIPCA), Shenyang, China, 28–30 June 2024; pp. 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubasinghe, O.; Zhang, X.; Chau, T.K.; Chow, Y.H.; Fernando, T.; Iu, H.H.C. A Novel Sequence to Sequence Data Modelling Based CNN-LSTM Algorithm for Three Years Ahead Monthly Peak Load Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 1932–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Guo, M.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Short-term load forecasting of industrial park considering time correlation under data-driven. In Proceedings of the 2024 Sixth International Conference on Next Generation Data-driven Networks (NGDN), Shenyang, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yu, H.; Xu, C.; Du, C. Multi-Feature Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting Based On Improved CNN-LSTM Combined Forecasting Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd Asia Power and Electrical Technology Conference (APET), Shanghai, China, 28–30 December 2023; pp. 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yin, S. Load Prediction Model of Integrated Energy System Based on CNN-LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Dali, China, 28–30 July 2023; pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhu, Q. Short-term electric load forecasting method based on hybrid ensemble deep learning framework. In Proceedings of the 2024 43rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 6352–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.; Bakeer, A. Generative Adversarial Network and CNN-LSTM Based Short-Term Power Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG), Tallinn, Estonia, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Bao, T. Short-Term Electricity Load Forecasting Based on NeuralProphet and CNN-LSTM. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 76870–76879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, T.; Xiong, B.; Ye, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, N. Short-term load forecasting of power system based on attention mechanism CNN-BiLSTM. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25–27 November 2022; pp. 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, B.S.; Adytia, D.; Aditya, I.A. Time Series Forecasting of Electricity Load Using Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM with an Attention Approach: A Case Study in Bali, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications (ICoDSA), Bandung, Indonesia, 9–10 August 2023; pp. 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, M.; Han, J.; Hu, H.; Yan, Q. Load Forecasting Method of Integrated Energy System Based on CNN-BiLSTM with Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (SPIES), Shanghai, China, 25–28 September 2021; pp. 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Wan, T.; Huang, Z. Research on CNN-BiLSTM Power Load Forecasting Based on VMD Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), Dali, China, 11–13 October 2023; pp. 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Bi, S.; Li, X.; Yin, X. Optimal Electric Heating Load Dispatch Strategy with CNN-BiLSTM-Attention and IGDT Interactive Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th New Energy and Energy Storage System Control Summit Forum (NEESSC), Hohhot, China, 29–31 August 2024; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Chen, X.; Ling, J.; Xu, Q. Short-Term Load Forecasting Based on Radam Optimized CNN-BiLSTM-AE Hybrid Model. In Proceedings of the 2022 Power System and Green Energy Conference (PSGEC), Shanghai, China, 25–27 August 2022; pp. 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, B.; Fernandez, R.I.; Gollapudi, V.; Li, X. Short-Term Aggregated Residential Load Forecasting using BiLSTM and CNN-BiLSTM. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Sakheer, Bahrain, 20–21 November 2022; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MA, W.; Duan, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, S. Short-Term Load Prediction of CNN-BILSTM Based on GWO Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon), Jinan, China, 21–22 September 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Qi, Y.; Wu, B. Short-term Photovoltaic Load Forecast Using RFE-CNN-BILSTM. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Dali, China, 28–30 July 2023; pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Zhong, Y. Short-Term Smart Grid Load Forecasting Based on CNN-BiLSTM with Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Energy, Power and Grid (ICEPG), Guangzhou, China, 27–29 September 2024; pp. 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Liu, Q. Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Based on CNN-BiLSTM-Attention Neural Network with ISSA Optimized. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML), Chongqing, China, 19–21 July 2024; pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, H. Short-term wind power load forecasting based on ISSA-CNN-BiLSTM. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Technology (ICEPET), Chengdu, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindra, H.; Sara, I.D.; Adriman, R. Daily Peak Load Forecast of Banda Aceh City Using Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) Method. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Computer System, Information Technology, and Electrical Engineering (COSITE), Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 2–3 August 2023; pp. 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Du, H.; Lei, Y.; Shan, M. Short-term Load Forecasting of Power System Based on Weighted Improved Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System and Random Forest. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024; pp. 2024–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, F.; Osman, A.; Hassan, M.S. ANFIS-Based Deployment for Precise Electricity Load Forecasting: A Netherlands Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Communications, Signal Processing, and their Applications (ICCSPA), Istanbul, Turkiye, 8–11 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitou, H.; Atillah, M.A.; Boudaoud, A.; Aqil, M. Load forecasting using fuzzy logic, artificial neural network, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system approaches: Application to South-Western Morocco. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 14, 7067–7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urošević, V. Determining the model for short-term load forecasting using fuzzy logic and ANFIS. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 11457–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlan, M.S.; Markus, E.D. Short Term Load Forecasting for Transnet Port in East London South Africa. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 572, 03001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, A.; Kissaoui, M.; Bahatti, L.; Raihani, A.; Errakkas, K.; Atifi, Y. Hybrid model for microgrid short term load forecasting based on machine learning. IFAC-Pap. 2024, 58, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Gao, X.; Guo, D.; Shang, E. Research on Short-term Load Forecasting Method Based on ANFIS-BPNN-LSSVM. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing and Intelligent Computing (SPIC), Guangzhou, China, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Revach, G.; Shlezinger, N. Adaptive Kalmannet: Data-Driven Kalman Filter with Fast Adaptation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 5970–5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Das, A.; Guler, S.I. Hybrid hidden Markov LSTM for short-term traffic flow prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.04954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Park, J. Scalable Hybrid HMM with Gaussian Process Emission for Sequential Time-series Data Clustering. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.01917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Giacoumidis, E.; Billah, S.M.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Sahu, P.; Richter, A.; Faerber, M.; Kaefer, T. Machine Learning in Short-Reach Optical Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. Photonics 2024, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latrach, A.; Malki, M.L.; Morales, M.; Mehana, M.; Rabiei, M. A critical review of physics-informed machine learning applications in subsurface energy systems. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 239, 212938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboussalah, A.M.; Li, X.; Chi, C.; Patel, R. The AI Black-Scholes: Finance-Informed Neural Network. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, Y.; Yang, S. Mid-long term load forecasting model based on support vector machine optimized by improved sparrow search algorithm. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, P.; Cao, W.N.; Wu, Q. Preview on structures and algorithms of deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Actiev Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), Chengdu, China, 19–21 December 2014; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoul, E.; Tuo, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, T.; Ling, M.; Li, X. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Short-Term Distribution System Load Forecasting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, G.; Hamrouche, B.; de Vilmarest, J. Frugal day-ahead forecasting of multiple local electricity loads by aggregating adaptive models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.08192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner, M.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Q.; Blažič, B.; Štruc, V. A Global Modeling Approach for Load Forecasting in Distribution Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.00493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Ahsan, M.; Hasanat, S.M.; Haris, M.; Yousaf, H.; Raza, S.F.; Tandon, R.; Abid, S.; Ullah, Z. Short-Term Load Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review and Simulation Study with CNN-LSTM Hybrids Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 111858–111881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Sohel, M.; Mohammad, N.; Sunny, M.S.H.; Dipta, D.R.; Hossain, E. A comprehensive review of the load forecasting techniques using single and hybrid predictive models. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 134911–134939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Bogarra, S.; Riaz, M.N.; Phyo, P.P.; Flynn, D.; Taha, A. From time-series to hybrid models: Advancements in short-term load forecasting embracing smart grid paradigm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskin, C.S.; Turgut, O.; Westgaard, S.; Cerit, A.G. Time series forecasting of domestic shipping market: Comparison of SARIMAX, ANN-based models and SARIMAX-ANN hybrid model. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2022, 14, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhe, F.G.Y.; Mbey, C.F.; Boum, A.T.; Ele, P.; Kakeu, V.J.F. A hybrid model for forecasting the consumption of electrical energy in a smart grid. J. Eng. 2022, 2022, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Kong, X.; Yue, L.; Liu, C.; Khan, M.A.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H. Short-term electrical load forecasting using hybrid model of manta ray foraging optimization and support vector regression. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, I.K.; Teimeh, M.; Adekoya, A.F.; Nyarko-Boateng, O. Forecasting electricity consumption of residential users based on lifestyle data using artificial neural networks. ICTACT J. Soft Comput. 2020, 10, 2107–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hong, T.; Fang, S.C. Benchmarking robustness of load forecasting models under data integrity attacks. Int. J. Forecast. 2018, 34, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.F.; Mohammed, O. Household load forecasting based on a pre-processing non-intrusive load monitoring techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Austin, TX, USA, 4–6 April 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, M.S.; Nikoo, M.R.; Chen, M.; Gandomi, A.H. Capturing complex electricity load patterns: A hybrid deep learning approach with proposed external-convolution attention. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 57, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, N.A.N.M.; Yusoff, S.H.B.; Gunawan, T.S.; Hanifah, M.S.A.; Zabidi, S.A.; Sapihie, S.N.M. Energy Management System of a Microgrid Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th International Conference on Smart Instrumentation, Measurement and Applications (ICSIMA), Bandung, Indonesia, 30–31 July 2024; pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Adnan, M.; Mohamed, S.E.G.; Tariq, M. A hybrid deep learning framework for short-term load forecasting with improved data cleansing and preprocessing techniques. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yin, X.; Chung, C.Y.; Rayeem, S.K.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Managing Massive RES Integration in Hybrid Microgrids: A Data-Driven Quad-Level Approach with Adjustable Conservativeness. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 7698–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Scope/Focus | Methods Covered | Strengths | Limitations/Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Broad review (smart grids/microgrids) | Traditional to AI-based methods | Comprehensive theoretical treatment | Omits exogenous variables; no clear ML vs DL taxonomy |

| [35] | Systematic + bibliometric (RL focus) | Reinforcement learning methods | Bibliometric approach | Narrow focus; limited comparative set; exogenous variables not analyzed |

| [36] | DL and hybrid models | Deep learning and hybrid approaches | Technical breakdown of methods | No bibliometrics; comparative tables lack refs/applications |

| [37] | Ensembles and hybrids | Ensemble/hybrid methods | Assesses sustainability/reliability | Narrow scope; lacks cluster/taxonomy analysis |

| [38] | Short-term forecasting emphasis | Traditional, DL, hybrid; short-term methods | Dataset compilation; specialized DB search | Limited exogenous analysis; mostly descriptive |

| [39] | Societal-impact oriented review | Theoretical methods up to 2024 | Thorough societal discussion | Exogenous variables not main focus; some model families excluded |

| [40] | Forecasting + anomaly detection | Forecasting and anomaly detection | Expands scope beyond prediction | Limited bibliometrics; shallow exogenous treatment |

| [41] | Systematic + bibliometric; localized case studies | Application-aware forecasting methods | Detailed bibliometric analysis | Highly localized (limits global generalizability) |

| [42] | Classification by horizon (short/med/long) | Models mapped to horizon-specific tasks | Clarifies horizon use-cases | Less evaluative; long-term forecasting underrepresented |

| Model Type | Description | Works | Metrics | Forecast Horizon | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | Simple linear model: | [45] | MAPE < 6% | Short | Interpretable, fast | Cannot capture nonlinearities |

| MLR | Multiple predictors estimated by least squares | [46,47,48,49,50,51,52] | MAPE < 4.5%; up to 0.99 | Short–Long | Multi-driver modeling | Degrades in long-term horizons |

| ARIMA | autorregresive + integrative + moving-average (p,d,q) | [3,47,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] | MAPE approx 7% | Short–Medium | Captures autocorrelation and trends | Limited with strong seasonality |

| SARIMA | ARIMA with seasonal terms | [53,54,55,56,57] | MAPE < 5% | Short | Good for periodic data | No exogenous terms by default |

| SARIMAX | SARIMA plus exogenous variables | [3,60] | MAPE approx 6% | Medium–Long | Models external drivers | Needs high-quality exogenous data |

| Holt–Winters (HWT) | Exponential smoothing with level/trend/seasonality (alpha, beta, gamma) | [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] | MAPE 2–13% | Short–Medium | Adaptive and efficient | Weaker for multi-seasonality |

| Bayesian models | Probabilistic inference giving posterior distributions | [73,74,75,76,77,78] | approx. 80% acc with 10% training data | Short | Good with sparse data; uncertainty quantification | Sensitive to priors; may be outperformed with large data |

| HMMs | Hidden states with transition and emission probabilities | [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] | Accuracy > 90% in some short-term studies; MAPE < 8% | Short–Medium | Models latent regimes; robust to noise | State design critical; needs data for stable transitions |

| Model Type | Description | Works | Metrics | Forecast Horizon | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVR | SVM for regression with epsilon-insensitive loss and kernels (C, epsilon) | [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,96] | MAPE < 4% (short); weekly acc 90%; RMSE 1208 MW | Short, weekly | Good nonlinear fit; robust with tuning | Sensitive to kernel/hyperparams; poor scaling |

| DT | Single decision tree; interpretable splits | [87,88,90,97,98,99,100] | Errors < 3.4% (short with weather) | Short | Interpretable; fast | Prone to overfitting; less stable |

| RF | Ensemble of trees; averages predictions | [98,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,110,111] | MAPE 3–19% (medium-long); best 1.7% reported | Short–Medium | Robust baseline; handles mixed features | May be outperformed by tuned boosting; inference cost |

| GB/XGBoost | Sequential boosting of trees; focus on residual errors | [101,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] | XGBoost: MAPE 1% (short examples) | Short–Medium | Often top accuracy; flexible loss | Sensitive to tuning; risk of overfitting |

| KNN/EKNN | Instance-based; average of k nearest neighbors | [91,95,96,112,113] | MAPE < 17% typical; down to 3% for 1–12 h; EKNN +12% acc | Short–Medium | Simple; interpretable | Prediction cost grows with data; sensitive to metric |

| Model Type | Description | Works | Metrics | Forecast Horizon | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCNN | Feedforward DNN trained via backpropagation | [59,65,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,124,134] | MAPE ≈ 1.68%; errors < 300 kWh | Short-term | Simple; nonlinear mapping | Needs feature engineering; limited temporal capture |

| LSTM | RNN with memory cells and gates | [12,65,116,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,128,130,131,132,133] | MAPE 1.4%, 0.98 | Short–Long | Captures long-term dependencies | Sensitive to tuning; heavy compute |

| GRU | Simplified LSTM with fewer gates | [122,127,128,129,131,132,133] | MAPE ≤ 2%, > 0.9 | Short–Medium | Fast training; compact structure | Slightly lower accuracy; limited memory depth |

| TCN/CNN | 1D dilated CNN for temporal data | [26,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149] | MAPE 1.65%; RMSE 3 kWh | Short–Medium | Fast, efficient; good local capture | Limited long-term receptive field |

| Transformer | Self-attention for long dependencies | [150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161] | MAPE < 3%; +5–10% vs. ARIMA | Short–Long | Long-range modeling; parallel | Data-hungry; high compute |

| CNN-LSTM | CNN feature extraction + LSTM sequence modeling | [163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175] | MAPE ≈ 3%; PCA-CNN-BiLSTM 1.07% | Short–Medium | Spatial-temporal synergy | Complex; long-term performance drops |

| CNN-BiLSTM | Bidirectional LSTM for dual temporal context | [176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187] | MAPE 1–3%; 0.9943 | Medium–Long | Robust; uses past/future data | More complex; high cost |

| Attention/ Metaheuristic Hybrids | Attention or optimization-enhanced CNN-BiLSTM (SSA, ISSA, GWO) | [183,186,187] | MAPE ↓ by 1–2% vs. base model | Short–Long | Enhanced feature weighting; faster convergence | Higher complexity; tuning overhead |

| ANFIS | Neuro-fuzzy inference model (5-layer hybrid) | [188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,211] | MAPE 0.6–1.7%; WOA-ANFIS-RF 0.99% | Short-term | Nonlinear + rule-based; interpretable | Difficult scaling; sensitive to rules |

| Hybrid Transformers | Probabilistic or multi-branch transformer models | [151,152,153,154,155,156,157] | MAPE < 3%; improved uncertainty quantification | Short–Long | Handles uncertainty; scalable | Very high training cost; low interpretability |

| Large Language Model | GPT-based adaptive self-tuning mechanism | [162] | MAE ↑ 90.7% and RMSE ↑ 88.5% including exogenous variables | Short-term | Manages extreme scenarios efficiently; scalable framework adaptable to other regions | current validation is restricted to a single regional and operational setting |

| Work | Weather | Socioeconomic | Cultural | Forecast Horizon | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | WS | H | SR | AP | CC | P | EA | PG | EP | CH | S | L | ||

| Traditional statistical Models | ||||||||||||||

| Supapo et al. [46] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Kapoor et al. [47] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Bracale et al. [49] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Saber et al. [50] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Hong et al. [51] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Hao et al. [52] |  |  |  |  | mid–long | |||||||||

| Fattah et al. [54] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Tarmanini et al. [56] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Hernández et al. [57] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Bensalah et al. [58] |  |  |  |  | short–mid | |||||||||

| Kumar Dubey et al. [60] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Kedrowski et al. [61] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Abd Jalil et al. [62] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Taylor et al. [63] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Özger et al. [64] |  | med | ||||||||||||

| Muneer et al. [65] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Shi et al. [66] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Abderrezak et al. [68] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Souza et al. [70] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Woo et al. [71] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Nanda et al. [75] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Bracale et al. [76] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Bessani et al. [77] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Henselmeyer et al. [80] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Niu et al. [81] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Roça et al. [84] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Álvarez et al. [86] |  |  | short–mid | |||||||||||

| Classical Machine Learning Models | ||||||||||||||

| Ali et al. [87] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Liu et al. [89] |  |  |  | short | ||||||||||

| Jahan et al. [90] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Bashawyah et al. [91] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Masood et al. [92] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Mathumitha et al. [93] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Chen et al. [94] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | mid–long | ||||||

| Alquthami et al. [96] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Hussain et al. [99] |  |  |  | mid | ||||||||||

| Kim et al. [100] |  | short–long | ||||||||||||

| Syed et al. [109] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||

| Zhang et al. [98] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Tiboaca et al. [97] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||

| Yaprakdal et al. [101] |  |  |  |  |  | mid | ||||||||

| Ungureanu et al. [102] |  |  | short–mid | |||||||||||

| Muzumdar et al. [103] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Singh et al. [104] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Wang et al. [105] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Su et al. [106] |  |  |  |  | short–mid | |||||||||

| Masood et al. [107] |  |  |  | short | ||||||||||

| Prashanthi et al. [108] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Bhatia et al. [110] |  | long | ||||||||||||

| Su et al. [111] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Nawaz et al. [95] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Khan et al. [112] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Ashfaq et al. [113] |  |  |  | short | ||||||||||

| Aimal et al. [114] |  |  |  | short | ||||||||||

| Bashawyah et al. [91] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Deep Learning Models | ||||||||||||||

| Zhu et al. [115] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Sayadlou et al. [117] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Yaprakdal et al. [135] |  |  |  | mid | ||||||||||

| Song et al. [116] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Yordanos et al. [118] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Gonzalez et al. [119] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Waheed et al. [122] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Krishna et al. [124] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||

| Manandhar et al. [125] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Hong et al. [12] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Fente et al. [126] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Gasparin et al. [127] |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||||

| Wen et al. [128] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short–mid | |||||||

| Xia et al. [129] |  |  |  | short | ||||||||||

| Massaoudi et al. [131] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Zuo et al. [136] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Gu et al. [137] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | ||||||

| Levikari et al. [138] |  |  |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||

| Liu et al. [140] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Tian et al. [141] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Zuo et al. [142] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Liu et al. [143] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Shi et al. [144] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Lu et al. [145] |  |  |  |  | short | |||||||||

| Yue et al. [148] |  |  | short–mid | |||||||||||

| Hybrid Models | ||||||||||||||

| Xiong et al. [164] |  | short | ||||||||||||

| Zhang et al. [166] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Han et al. [167] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Rubasinghe et al. [169] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Sun et al. [171] |  |  | short | |||||||||||

| Zhou et al. [173] |  |  | short | |||||||||||