Experimental Verification of a Method for Improving the Efficiency of an Evaporative Tower Using IEC

Abstract

1. Introduction

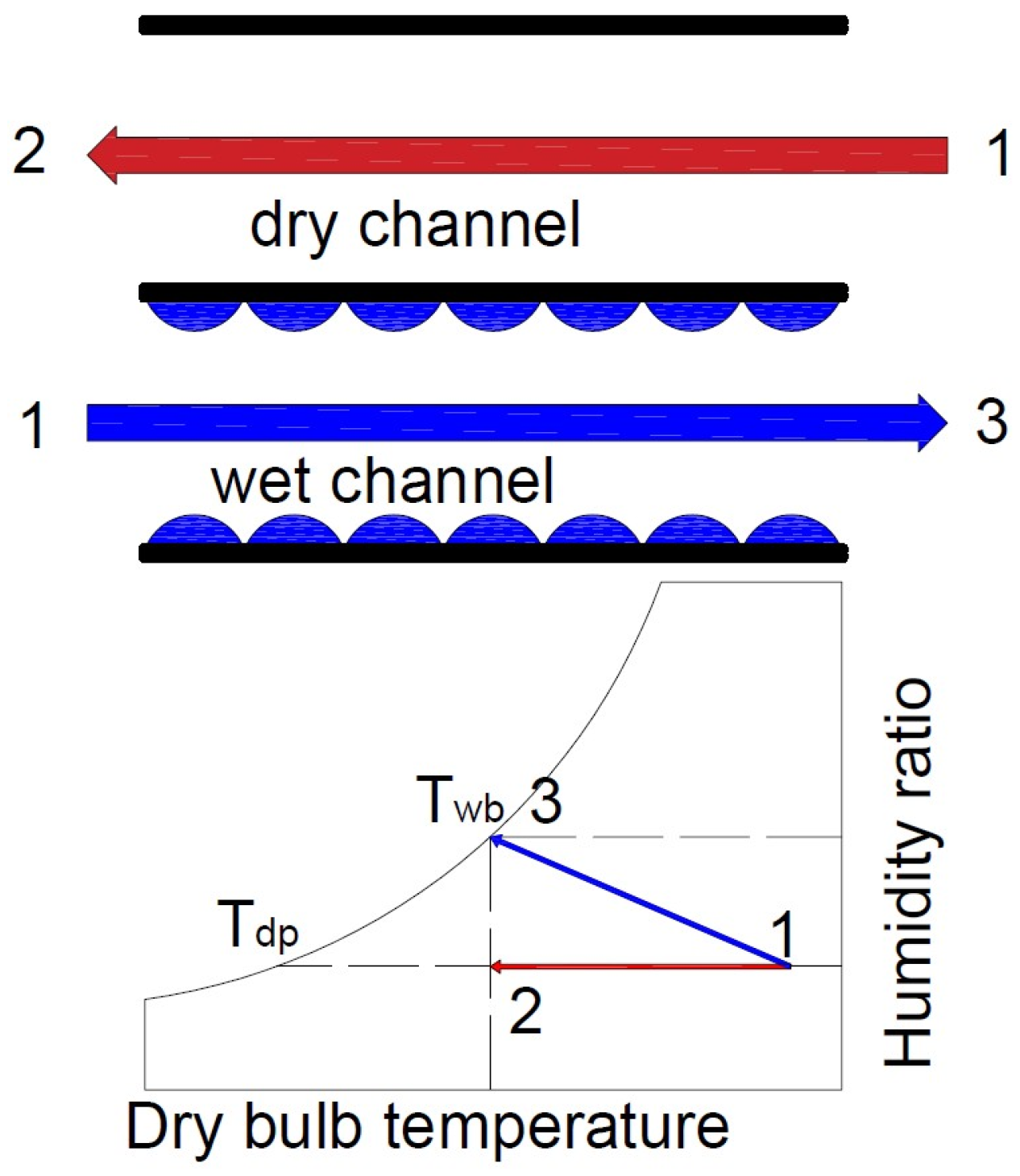

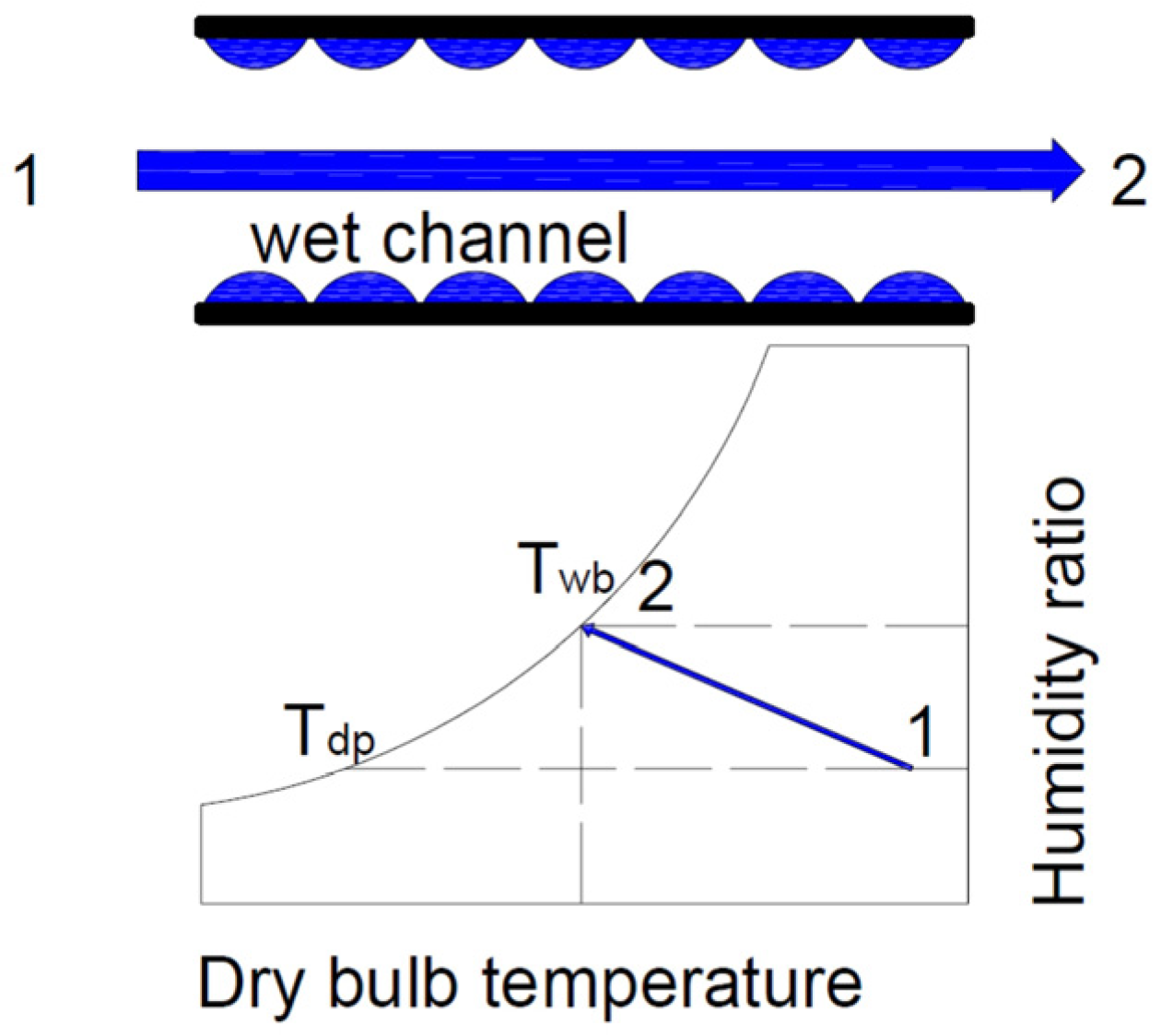

1.1. Evaporative Cooling Systems

1.2. Cooling Towers

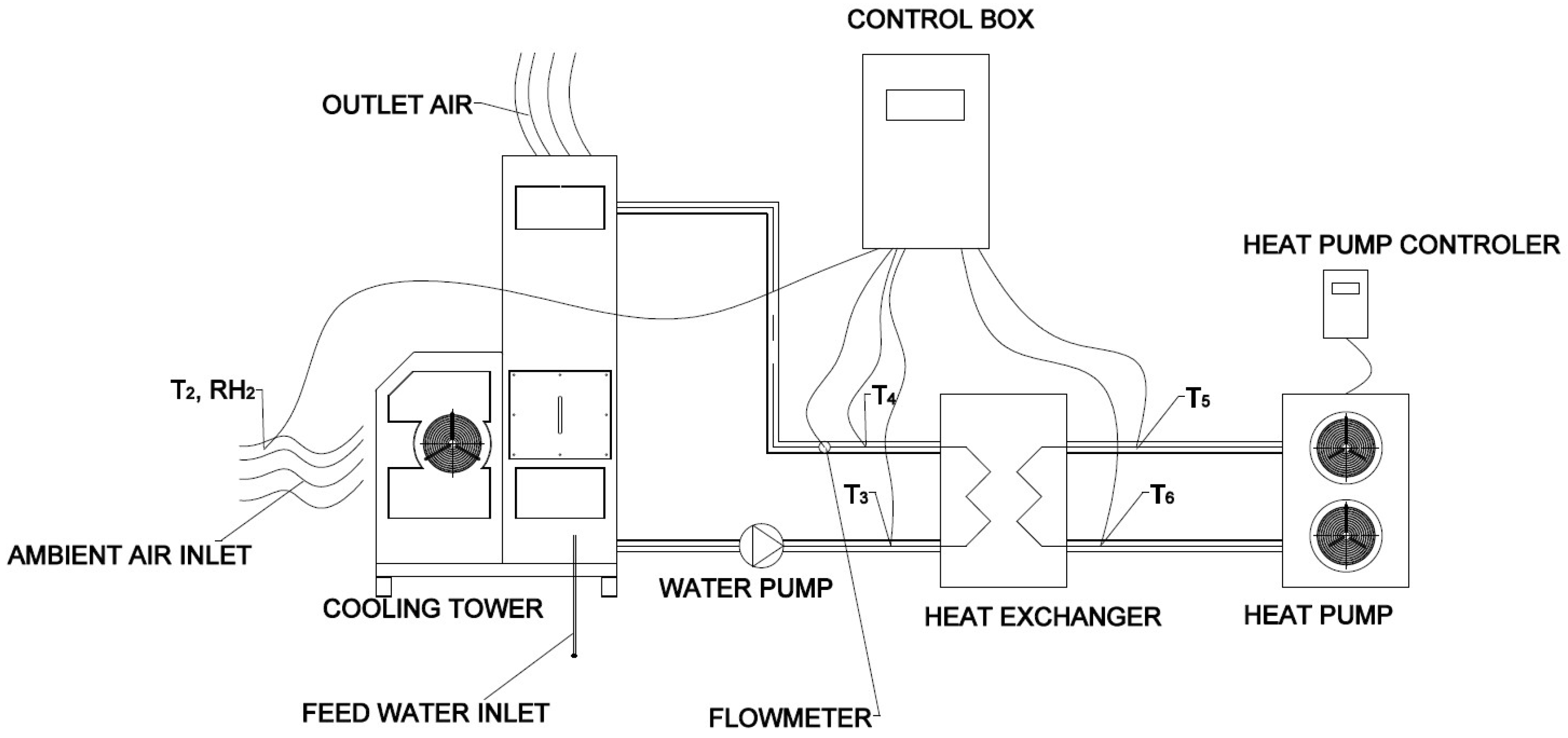

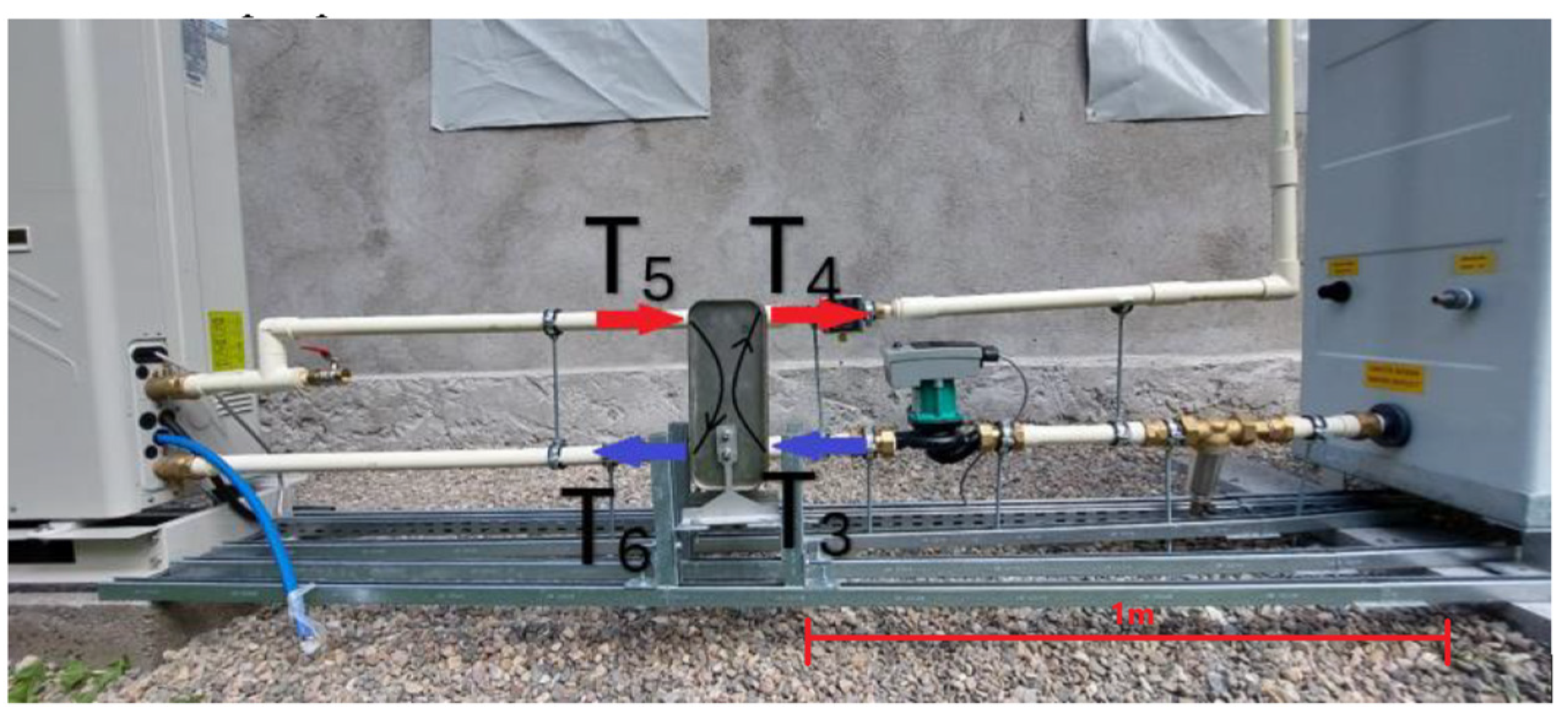

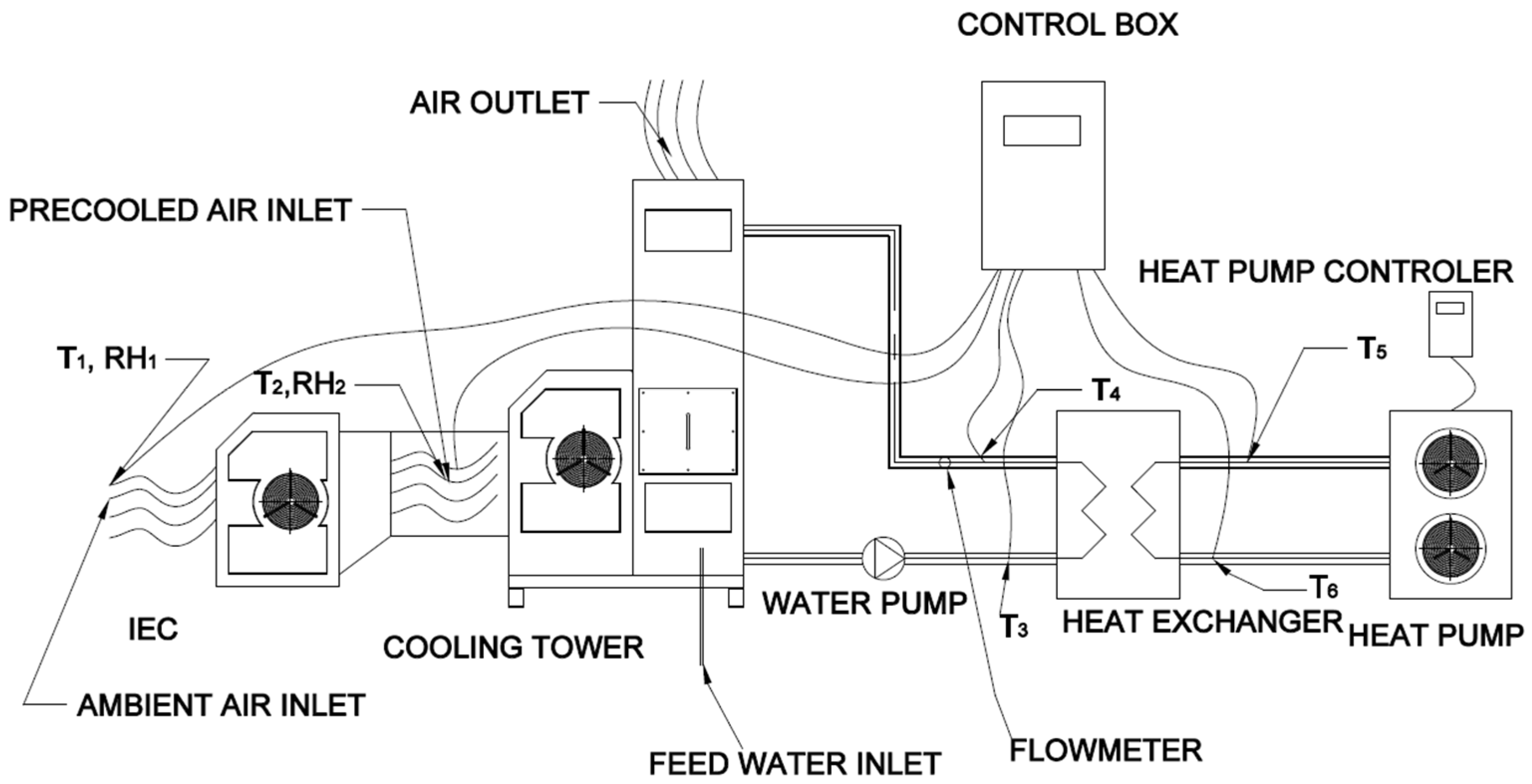

2. Description of the Experimental Stand and Research Methodology

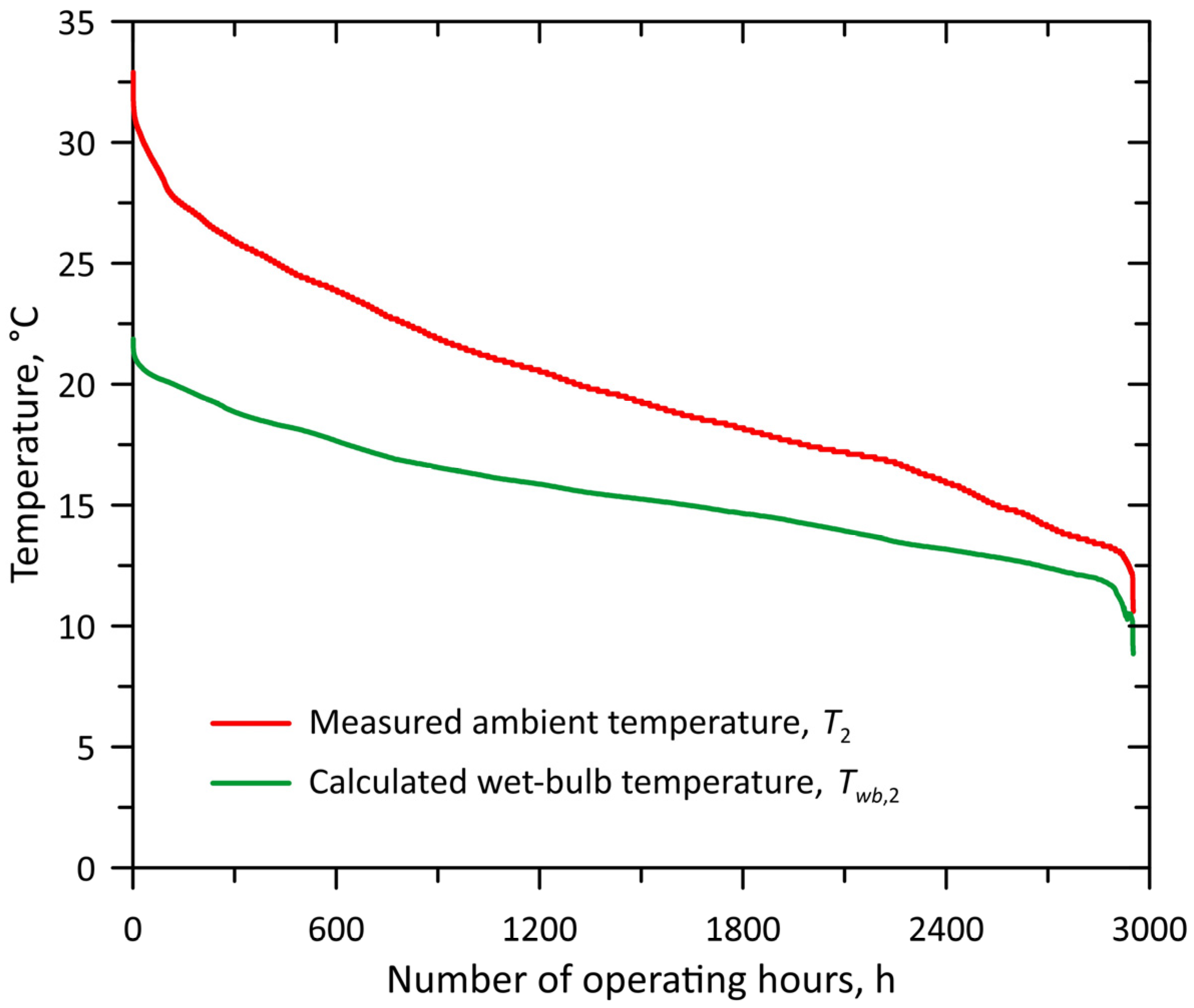

2.1. Stage I

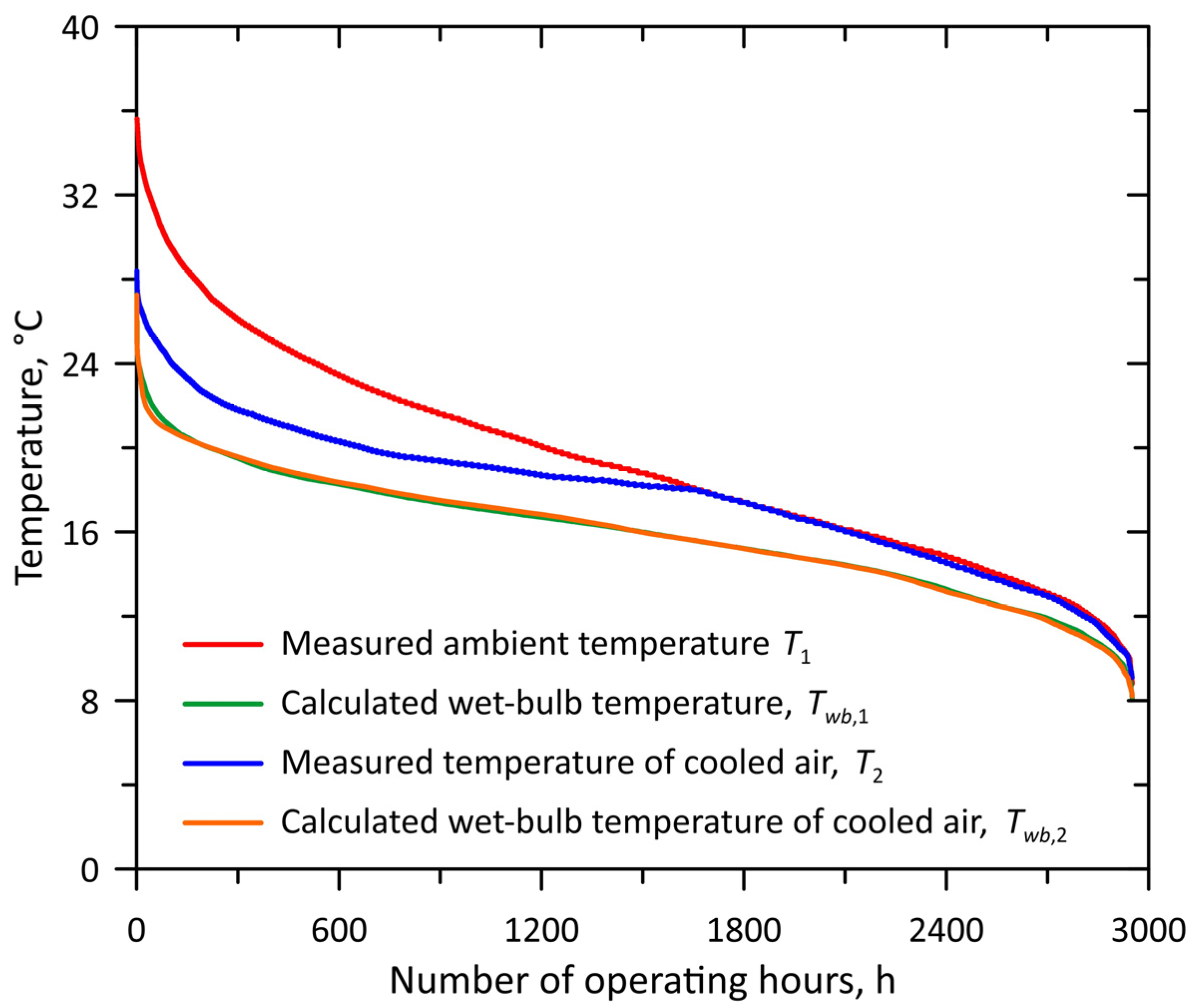

2.2. Stage II

2.3. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Test Under Increased Thermal Load—16 August 2024

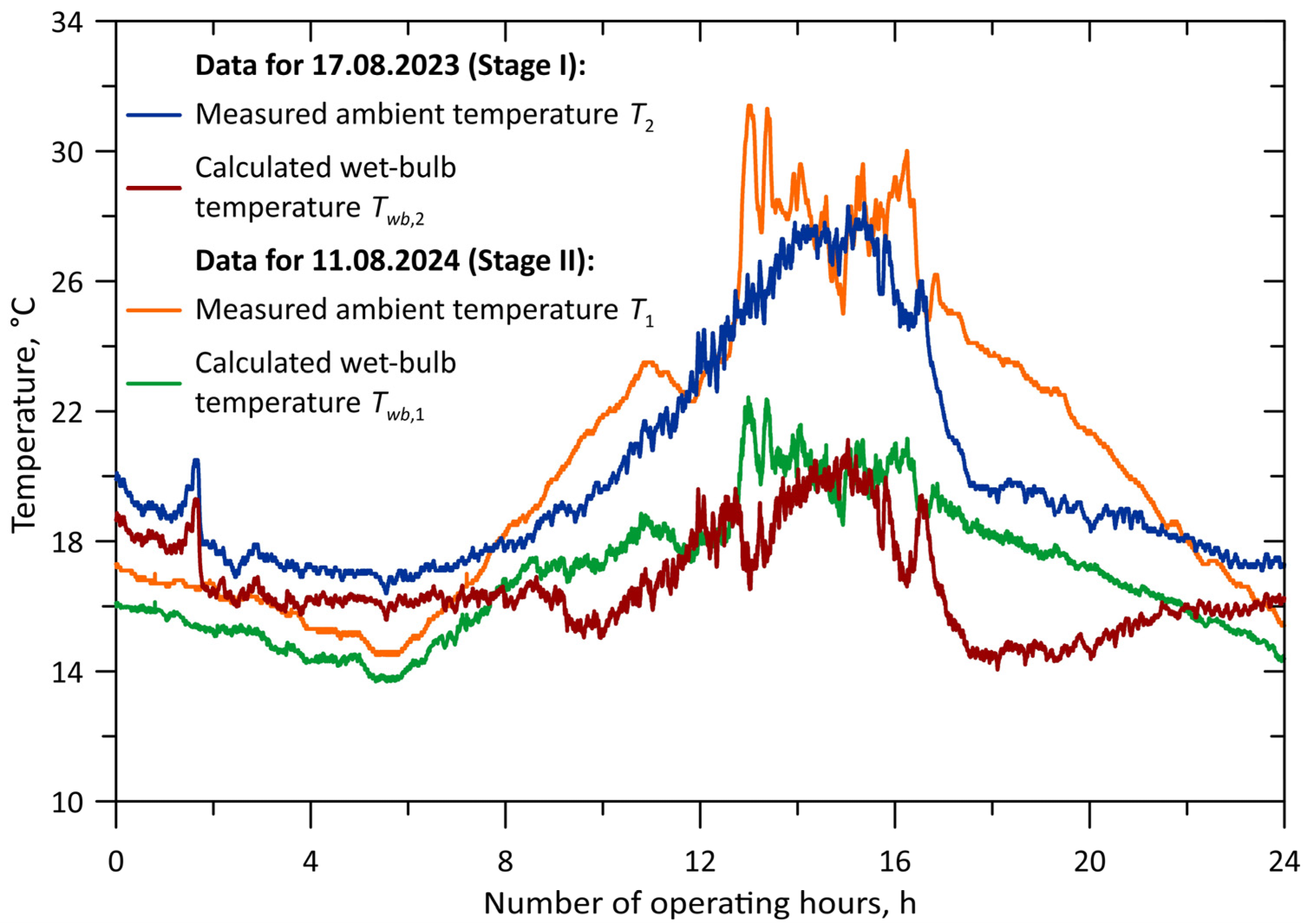

3.2. Comparison of Measurements for Selected Days of Stage I and Stage II

4. Analysis of Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Standalone HMX or MicroCore (CW3) modules installed at the cooling tower air inlet;

- A single fan driving the ambient air stream, which is then precooled and finally exhausted from the cooling tower, overcoming total pressure losses in the system.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

| DEC | Direct Evaporative Cooler |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HMX | Heat and Mass Exchanger |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| IEC | Indirect Evaporative Cooler |

| M-cycle | Maisotsenko Cycle |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| SCOP | Seasonal Coefficient of Performance |

| VCRS | Vapour-Compression Refrigeration System |

References

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Cooling. Opportunities for Energy-Efficient Air Conditioning, OECD/IEA, 2018. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- BITZER Kuehlmaschinenbau GmbH. Refrigerant Report 20; A-501-20 EN. Available online: https://www.bitzer.de (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Yang, Z.; Feng, B.; Ma, H.; Zhang, L.; Duan, C.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, Z. Analysis of lower GWP and flammable alternative refrigerants. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 126, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artusoa, P.; Marinetti, S.; Minetto, S.; Del Col, D.; Rossetti, A. Modelling the performance of a new cooling unit for refrigerated transport using carbon dioxide as the refrigerant. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 115, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.; Mancin, S.; Righetti, G.; Zilio, C. Hydrocarbon refrigerants HC290 (Propane) and HC1270 (Propylene) low GWP long-term substitutes for HFC404A: A comparative analysis in vaporisation inside a small-diameter horizontal smooth tube. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 124, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaji, H.S.; Mrabet, B.M. Development and experimental sensitivity analysis of a Maisotsenko-cycle water desalination system under diverse climate conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelidis, D.; Cichoń, A.; Pacak, A.; Drąg, P.; Drąg, M.; Worek, W.; Cetin, S. Water desalination through the dewpoint evaporative system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 229, 113757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafifar, M.; Gadalla, M. Innovative inlet air cooling technology for gas turbine power plants using integrated solid desiccant and Maisotsenko cooler. Energy 2015, 87, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafifar, M.; Gadalla, M. Analysis of Maisotsenko open gas turbine power cycle with a detailed air saturator model. Appl. Energy 2015, 149, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baakeem, S.; Orfi, J.; Mohamad, A.; Bawazeer, S. The possibility of using a novel dew point air cooling system (M-Cycle) for A/C application in Arab Gulf Countries. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, A.; Sayyaadi, H.; Mohammadhosseini, N. Comparative study of the conventional types of heat and mass exchangers to achieve the best design of dew point evaporative coolers at diverse climatic conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 158, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiei, A.; Akhlaghi, Y.G.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Yi, F.; Wang, Z. Can whole building energy models outperform numerical models, when forecasting performance of indirect evaporative cooling systems? Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 213, 112886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfani, S.; Karami, M. Transient simulation of solar desiccant/M-Cycle cooling systems in three different climatic conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchini, E.; Naldi, C. Energy saving obtainable by applying a commercially available M-cycle evaporative cooling system to the air conditioning of an office building in North Italy. Energy 2019, 179, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, F.; González, J.C.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; De Adana, M.R. Experimental energy performance assessment of a solar desiccant cooling system in Southern Europe climates. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 165, 114579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelidis, D.; Anisimov, S.; Worek, W.M. Performance study of the Maisotsenko Cycle heat exchangers in different air-conditioning applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 81, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorný, J.; Madejski, P.; Fišer, J. Sustainable air conditioning with a focus on evaporative cooling and the Maisotsenko cycle. Arch. Thermodyn. 2025, 46, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, M.; Xi, W.; Hu, E. Experimental Study on the Performance of a Dew-Point Evaporative Cooling System with a Nanoporous Membrane. Energies 2022, 15, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ahmad, W.; Sheikh, N.A.; Ali, H.; Kousar, R.; Rashid, T. Performance enhancement of a cross flow dew point indirect evaporative cooler with circular finned channel geometry. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Riffat, S. A state of the art review of evaporative cooling systems for building applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelidis, D.; Anisimov, S.; Worek, W.; Drag, P. Numerical analysis of a desiccant system with cross-flow Maisotsenko cycle heat and mass exchanger. Energy Build. 2016, 123, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hsu, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, S. Silica gel polymer composite desiccants for air conditioning systems. Energy Build. 2015, 101, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozubal, E.; Slayzak, S. Coolerado 5 Ton RTU Performance: Western Cooling Challenge Results; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2010.

- Cui, X.; Chua, K.J.; Islam, M.R.; Ng, K.C. Performance evaluation of an indirect pre-cooling evaporative heat exchanger operating in hot and humid climate. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 102, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Talukdar, P.; Jain, S. Energy savings in a building using regenerative evaporative cooling. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarinejad, G.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Delfani, S.; Esmaeelian, J. Experimental investigation of two-stage indirect/direct evaporative cooling system in various climatic conditions. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 2073–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Salomon, B.C.; Acharya, S.; Kozlov, A.; Chudnovsky, Y. Utilizing Reversed Brayton Cycle for Enhanced Cooling Tower Technology. Heat Transf. Eng. 2025, 46, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelidis, D.; Drag, M.; Drag, P.; Worek, W.; Cetin, S. Comparative analysis between traditional and M-Cycle based cooling tower. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 159, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, R. Performance Evaluation of a Maisotsenko Cycle Cooling Tower with Uneven Length of Dry and Wet Channels in Hot and Humid Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITA Cooling Technologies S.r.l.,Via del Benessere, 13, Siziano 27010, Pavia, IT. Available online: https://www.mitacoolingtechnologies.com/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Stull, R. Wet-bulb temperature from relative humidity and air temperature. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2011, 50, 2267–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wang, Y. A novel method to derive formulas for computing the wet-bulb temperature from relative humidity and air temperature. Measurement 2018, 128, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taler, D. Calculation and Experimental Research on Heat Exchangers; Wydawnictwo PK: Cracow, Poland, 2016. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

| Measured Parameter | Symbol | Location/Description | Resolution | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooled water temperature | , °C | Cooling tower outlet | 0.1 °C | 1.5% |

| Heated water temperature | , °C | Cooling tower inlet | 0.1 °C | 1.5% |

| Heated water temperature | , °C | Heat pump outlet | 0.1 °C | 1.5% |

| Cooled water temperature | , °C | Heat pump inlet | 0.1 °C | 1.5% |

| Ambient air temperature | , °C | Cooling tower air inlet | 0.1 °C | 1.5% |

| Relative humidity | RH, % | Cooling tower air inlet | 1 °C | 1.5% |

| Water flow rate | , m3/h | Cooling tower water loop | 0.1 m3/h | 0.1% |

| Research Methods | Description |

|---|---|

| Document examination method | A literature review was conducted, and existing research on evaporative cooling devices was analysed. |

| Experimental method | Measurements on the experimental stand were carried out and recorded. An analysis of the measured values was carried out. |

| Mathematical modelling | Based on the measurements, calculations were performed for quantities that could not be directly measured, such as SCOPCT. An analysis of the results obtained was carried out. |

| Parameter | Stage I | Stage II |

|---|---|---|

| , °C | 30.1 ± 1.5% | 30.6 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 25.1 ± 1.5% | 24.8 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 36.0 ± 1.5% | 35.3 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 30.0 ± 1.5% | 29.7 ± 1.5% |

| , kW | 17.3 ± 1.9% | 19.9 ± 1.9% |

| , kW | 18.2 ± 2.0% | 19.3 ± 1.7% |

| , °C | 19.0 ± 1.5% | 19.9 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 15.9 ± 1.5% | 17.1 ± 1.6% |

| Frequency, Hz | 31.7 ± 5.0% | 29.0 ± 5.0% |

| , mA | 380.4 ± 5.0% | 327.6 ± 5.0% |

| , m3/h | 2.9 ± 0.1% | 2.9 ± 0.1% |

| Stage I | Stage II | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity of cooling energy generated by the cooling tower , kWh | 51,050 ± 3.5% | 58,550 ± 3.7% |

| Electricity consumption of the cooling tower , kWh | 1115 ± 3.4% | 980 ± 3.1% |

| Quantity of heat energy generated by the heat pump , kWh | 53,460 ± 3.8% | 56,659 ± 3.9% |

| SCOPCT, kWh/kWh | 45.8 ± 2.2% | 59.7 ± 2.4% |

| Parameter | 1st Hour 10:45/11:45 | 2nd Hour 11:45/12:45 | 3rd Hour 12:45/13:45 | 4th Hour 13:45/14:45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| , °C | 25.1 ± 1.5% | 31.1 ± 1.5% | 30.9 ± 1.5% | 31.1 ± 1.5% |

| , % | 71.6 ± 5.0% | 52.4 ± 5.0% | 51.1 ± 5.0% | 48.3 ± 5.0% |

| , °C | 20.7 ± 1.5% | 21.2 ± 1.5% | 21.3 ± 1.5% | 21.6 ± 1.5% |

| ,% | 90.1 ± 5.0% | 90.6 ± 5.0% | 89.7 ± 5.0% | 86.9 ± 5.0% |

| , °C | 25.5 ± 1.5% | 25.3 ± 1.5% | 25.3 ± 1.5% | 25.3 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 34.9 ± 1.5% | 35.1 ± 1.5% | 35.1 ± 1.5% | 34.8 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 44.8 ± 1.5% | 45.4 ± 1.5% | 45.1 ± 1.5% | 45.1 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 34.7 ± 1.5% | 35.3 ± 1.5% | 35.1 ± 1.5% | 34.9 ± 1.5% |

| , kW | 32.8 ± 3.5% | 34.2 ± 3.5% | 35.1 ± 3.5% | 33.4 ± 3.5% |

| , kW | 30.7 ± 3.1% | 33.5 ± 3.1% | 32.3 ± 3.1% | 31.9 ± 3.1% |

| Parameter | Stage I | Stage II |

|---|---|---|

| , °C | 25.0 ± 1.5% | 25.0 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 30.2 ± 1.5% | 30.1 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 30.0 ± 1.5% | 29.9 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 35.0 ± 1.5% | 35.1 ± 1.5% |

| , kW | 17.4 ± 1.5% | 19.6 ± 1.9% |

| , kW | 18.2 ± 1.7% | 19.9 ± 2.1% |

| , °C | 20.1 ± 1.5% | 20.5 ± 1.5% |

| , °C | 16.6 ± 1.6% | 16.9 ± 1.6% |

| Frequency, Hz | 32.5 ± 5.0% | 29.3 ± 5.0% |

| , mA | 390.7 ± 5.0% | 378.1 ± 5.0% |

| , m3/h | 2.9 ± 0.1% | 2.9 ± 0.1% |

| Stage I | Stage II | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity of cooling energy generated by the cooling tower , kWh | 417.6 ± 3.4% | 470.4 ± 3.7% |

| Electricity consumption of the cooling tower , kWh | 9.4 ± 3.4% | 9.1 ± 3.1% |

| Quantity of heat energy generated by the heat pump, kWh | 436.8 ± 3.2% | 477.6 ± 3.3% |

| SCOPCT, kWh/kWh | 44.4 ± 2.2% | 51.7 ± 2.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jagieła, B.; Jaremkiewicz, M. Experimental Verification of a Method for Improving the Efficiency of an Evaporative Tower Using IEC. Energies 2026, 19, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020554

Jagieła B, Jaremkiewicz M. Experimental Verification of a Method for Improving the Efficiency of an Evaporative Tower Using IEC. Energies. 2026; 19(2):554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020554

Chicago/Turabian StyleJagieła, Bartosz, and Magdalena Jaremkiewicz. 2026. "Experimental Verification of a Method for Improving the Efficiency of an Evaporative Tower Using IEC" Energies 19, no. 2: 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020554

APA StyleJagieła, B., & Jaremkiewicz, M. (2026). Experimental Verification of a Method for Improving the Efficiency of an Evaporative Tower Using IEC. Energies, 19(2), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020554