1. Introduction

The ongoing transformation of power systems into smart grid architectures introduces new complexities in coordination, optimization, and real-time decision-making. A smart grid is characterized by distributed energy resources (DERs), bidirectional communication, and active consumer participation in demand-side management (DSM) mechanisms. DSM empowers consumers to reshape their load profiles, thereby reducing peak demand and lowering system-wide costs [

1]. The emergence of aggregator-based energy markets further enhances operational flexibility by enabling groups of consumers to pool and trade energy resources collectively.

Despite these advances, existing approaches typically optimize grid layers in isolation—treating DSM, market pricing, communication infrastructure, and network feasibility as separate problems. For example, advanced DSM heuristics (e.g., hybrid GA [

2] or flexibility-aware PSO [

3], and meta-heuristic DSM for smart communities [

4]) treat voltage stability and communication constraints as external validation steps rather than integral optimization components. Similarly, aggregator models [

5,

6,

7] optimize economic signals without real-time grid feedback, producing solutions that, while cost-effective, may violate voltage limits or suffer from communication delays under uncertainty.

Moreover, traditional optimization methods—such as linear or dynamic programming—struggle to scale to the nonlinear, non-convex, and stochastic nature of modern grids. Although metaheuristics like GA and PSO offer greater flexibility, they rarely embed physical and communication constraints directly into the optimization process.

Recent attempts at integration—such as Masoumi-Anaraki et al. [

7] coupling storage with pricing or Aslam et al. [

8] using ML surrogates—are often offline, computationally expensive, or decoupled in execution. None fully unify DSM scheduling, dynamic pricing, data aggregator placement (DAP), and AC feasibility within a real-time, heuristic framework that guarantees anytime feasibility—a gap this paper addresses.

The H-EMOS-Lite (Heuristic Energy Management and Optimization System—Lite) framework co-optimizes four interdependent layers of smart grid operation:

Demand-side management (DSM) scheduling,

Dynamic pricing via aggregators,

Data aggregator placement (DAP) for communication,

AC load-flow feasibility for network safety.

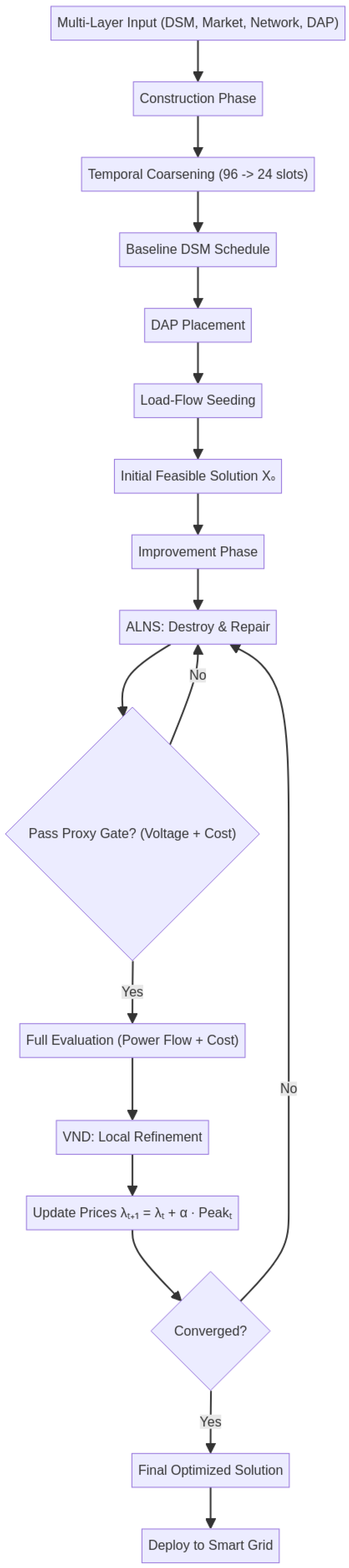

Rather than optimizing these layers sequentially or independently, H-EMOS-Lite employs a two-phase heuristic:

Construction Phase: Generates an initial solution that is feasible by design—satisfying comfort, coverage, voltage, and operational constraints from the outset.

Improvement Phase: Uses adaptive search operators (ALNS + VND) guided by lightweight proxy models to refine the solution while maintaining feasibility.

This design ensures anytime deployability, meaning even partial or early-terminated solutions remain physically and economically valid.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents related work on DSM, aggregator-based optimization, heuristic load-flow analysis, and DAP planning.

Section 3 details the proposed H-EMOS framework, including mathematical formulations and the interaction between layers.

Section 4 describes the simulation setup and presents experimental results and performance analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future extensions, including stochastic renewable integration and multi-objective Pareto optimization.

2. Related Work

The evolution of smart grids has encouraged extensive research into coordinated optimization among demand-side management (DSM), aggregator-based market operations, communication-layer planning, and network feasibility analysis. Although great advances have been made in each field, most studies remain confined to single-layer optimization, which inhibits overall system efficiency and agility.

2.1. Demand-Side Management (DSM) Optimization

Early DSM efforts were based on deterministic control algorithms, such as linear programming [

9], dynamic programming, mixed-integer optimization, and flat pricing–based DSM schemes [

10] for cost reduction and peak demand decrement. Although these models were effective in specifying the schedule of a small-scale system, they became impractical for large numbers of users and intervals. In response, heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms have become popular in DSM because of their scalability and adaptability. Javaid et al. [

2] proposed a hybrid genetic heuristic algorithm that could significantly decrease peak loads, while Hassan et al. [

3] proposed a search method to rank appliances according to flexibility and comfort. Similarly, Kazmi et al. [

11], Asgher et al. [

12], and Alghamdi et al. [

13] utilized hybrid optimization on renewable-integrated DSM, and the results were better in terms of convergence and energy balance.

Despite these achievements, current DSM models operate in isolation from grid-level constraints—they minimize user-level scheduling cost without considering electrical feasibility or communication latency. As described by Nutakki and Mandava [

14] and Mimi et al. [

15], the major challenge of DSM works is to come up with efficient solutions without considering the cross-layer design.

2.2. Aggregator-Based Optimization and Market Coordination

The emergence of aggregators as intermediaries between consumers and the grid has allowed cooperative energy management and dynamic pricing. Hansen et al. [

5] presented a heuristic resource allocation model for aggregators, which considered profitability as well as load coordination. Zhang et al. [

6] introduced a game-theoretic DSM model that manages user behavior by controlling the neighbor level cooperation. Masoumi-Anaraki et al. [

7] continued this work by proposing stochastic pricing with centralized storage for enhanced power network control as well as cost. Nonetheless, these models emphasize the economic optimization and do not consider physical network limitations such as voltage stability and distribution loss. As noted by Judge et al. [

1] and Ghorpade and Sharma [

16], most market layer optimizers lack integration of real-time grid feedback, preventing them from realistically operating under time-variant grids.

2.3. Communication Infrastructure and Data Aggregator Placement (DAP)

Effective communication is paramount for the development of reliable DSM and pricing coordination. In the literature, research on data aggregator placement (DAP) and Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) aims mainly at achieving communication coverage with low overlapping. Lezama et al. [

17] proved the effectiveness of K-means and set-cover heuristics for large-scale placement of aggregators, and Wang et al. [

9] developed a multi-objective binary metaheuristic for the joint optimization of communication latency and energy consumption in IoT-enabled systems. However, DAP and AMI studies are still typically decoupled from DSM and market optimization, resulting in control actions that are inappropriate and delayed responses. Bakare et al. [

18] highlighted the importance of research by spanning communication and energy layers using co-optimization schemes; however, not many existing models capture such an integration in real-time constraints.

2.4. Load-Flow Analysis and Network Feasibility

The reliability of DSM and aggregator decisions is meaningful only when they are feasible, which requires a solid load-flow analysis. Classical solvers, such as the backward–forward sweep and Newton–Raphson methods, provide accuracy but are computationally intensive and are not suitable for iterative optimization problems. Khan et al. [

19] and Kazmi et al. [

11] proposed heuristic and metaheuristic strategies with simplified voltage validation in DSM scheduling. Recent studies, such as the study by Aslam et al. [

8], have studied surrogate models and ML-based proxies to accelerate feasibility tests without sacrificing accuracy. However, in most network studies, computing load-flow proofs is considered as post-processing and is not embedded into a common solution method of optimization itself. This disaggregation is undesirable in terms of the combined system efficiency, as power-flow feedback is not incorporated into price decisions.

2.5. Comparative Summary

Table 1 presents summary of the representative methods in different layers of smart grid optimization. Although these approaches exhibit good performances in specific domains, they work in isolation and do not tend to jointly consider DSM, pricing, communication, and electrical feasibility, which is one of the contributions of H-EMOS-Lite.

Based on the literature review, we can observe that current solutions provide standalone optimizations per layer. In addition, DSM methods are developed for load scheduling, and aggregator models for economic equilibrium. DAP algorithms ensure improving communication reliability and surrogate-based load-flow models to enhance the feasibility check. However, none of these studies achieve simultaneous optimization across DSM, aggregator pricing, DAP configuration, and power-flow validation under real-time constraints. The proposed H-EMOS-Lite framework addresses this multi-layer coupling through an adaptive construct–improve heuristic process guided by proxy-based evaluation. This integration enables feasible, near-real-time coordination of economic, operational, and physical grid layers—bridging the gap between algorithmic performance and system-wide practicality.

3. Proposed H-EMOS-Lite Framework

The proposed H-EMOS-Lite (Heuristic Energy Management and Optimization System—Lite) is a multi-layer adaptive framework designed to co-optimize demand-side scheduling, market pricing, data aggregator placement, and power-flow validation in real time. Unlike conventional single-layer or Sequential Optimization techniques, H-EMOS-Lite coordinates the economic, operational, communication, and physical layers of the smart grid within a unified heuristic process. The framework operates through two major stages:

A construction phase establishes a first feasible solution from scratch, which ensures all comfort, coverage, and voltage constraints; and

An improvement phase further refines the solution using adaptive search and proxy-gated evaluation to approach a locally optimal trade-off among cost, peak load, and profile smoothness.

Figure 1 illustrates the sequential workflow of the H-EMOS-Lite framework, from multi-layer data integration to adaptive optimization and validation. It highlights the interaction between construction and improvement phases, supported by a feedback loop that ensures continuous feasibility and convergence.

3.1. Input Phase: Multi-Layer Data Integration and Initialization

Table 2 summarizes the main input layers of the H-EMOS-Lite framework, detailing their data components and specific functional roles within the multi-layer optimization process.

All values are given in per unit (p.u.) with a 100 kW system base for enabling synchronization at a 15 min temporal resolution (96 intervals/day). The pre-processing included time synchronization, filling-in time gaps, and mapping households to the nearest network bus level and layer-wise normalization. A joint constraint set is then formed, which includes

Comfort limitations (temperature, SoC, and appliance time window)

Power-flow constraints (bus voltage being in legal limits), and

Coverage restrictions (≥99% of smart meters attached to a DAP).

This harmonized, cross-layer dataset forms the multi-dimensional input vector

which ensures consistent interoperability between all grid layers and establishes a physically grounded starting point for optimization.

3.2. Construction Phase: Feasible Solution Generation

The construction phase produces an initial, feasible configuration that satisfies all comfort, communication, and electrical constraints. It is composed of four coordinated modules: (a) temporal coarsening, (b) baseline DSM scheduling, (c) data aggregator placement (DAP) initialization, and (d) load-flow seeding.

3.2.1. Temporal Coarsening

To balance fidelity and computational tractability, the original 15 min data are aggregated into hourly “macro-slots”. This reduces the temporal dimension from 96 to 24 intervals, achieving approximately 75% reduction in search complexity while preserving essential load and price dynamics.

Formally, for each household

i and each hourly time slot

t:

where

and

are the power requirement and prices at 15 min intervals, respectively, and

represents the set of four consecutive 15 min steps contained within hour t. This operation smooths short-time event streaming while preserving the hourly profile required for DSM and dynamic pricing (DP) decisions. Accordingly, the H-EMOS-Lite exhibits a fourfold reduction in temporal complexity and enables near-real-time optimization with no compromise in representational accuracy or operational realism.

Running Example

Table 3 presents an example of fine-grained household load data recorded at 15 min intervals, illustrating the temporal resolution used before aggregation into hourly macro-slots.

To apply temporal coarsening, H-EMOS-Lite aggregates these four values into a single “macro-slot” (the average or total over the hour):

So, instead of having 96 decision points (for 96 quarter-hours), the system now has only 24 h points. This reduces the optimization dimension by 75%, while preserving key characteristics of the daily load profile—such as morning and evening peaks and midday troughs.

Pre-coarsening: The optimizer must make 96 time steps × 100 households = 9600 decisions.

Post-coarsening: Only 24 × 100 = 2400 decisions—that is much faster optimization

Outcome: The model still discerns when energy use peaks (morning and evening) but ignores irrelevant minute-by-minute fluctuations that do not impact pricing or control.

3.2.2. Baseline DSM Scheduling

The baseline DSM scheduling module constructs an initial cost-efficient and comfort-feasible load schedule. Each flexible appliance i has two important metrics:

Peak Contribution : The highest power demand (kW) contributed when active—it shows how strongly it affects the total peak load.

Flexibility Index : The flexibility index is calculated as the ratio of adjustable hours to the total operational window:

- ○

= number of hours the appliance can shift (flexible hours),

- ○

= total operation window available (hours).

Example Data

Step 1—Gathering Data:

Table 4 lists the main parameters of flexible household appliances and their corresponding ranking indicators, showing how each device’s power and flexibility contribute to its priority in the baseline DSM scheduling process.

Step 2—Ranking: For this purpose, appliances are ranked based on cost effectiveness and flexibility: (). The ranking scores were as follows: EV charger (1.09), HVAC (0.43), water heater (0.36), and washing machine (0.17). The EV charger, having the highest score, is selected as the appliance with the top priority to reschedule in the greedy shifting process because it has the maximum impact on the peak load and provides the largest feasible deviation.

Step 3—Greedy Load Shifting: Next, the household hourly electricity prices for each appliance’s operating period are examined. For instance, the EV charger provides power from 18:00 to 07:00. Hours 18:00–22:00 are high-priced (peak) and hours 23:00–03:00 are low-priced (off-peak); this forces the EV’s charging schedule into the lower-cost window, while still ensuring that it satisfies its operational constraint of finishing charging by 07:00 h. In this example, the original scheduled charging from 18:00 to 21:00 (expensive) is shifted to 23:00–02:00 (cheaper). This shift in energy use serves to lower both the energy cost and the aggregate peak demand.

Step 4—Apply Comfort Constraints: If any comfort constraint is violated (e.g., temperature drifting beyond limits), a repair mechanism automatically adjusts the schedule back within the comfort zone to ensure feasibility.

Step 5—Result: After processing all devices, the overall load shape had a significantly smaller peak demand and appeared flattened. The sum of the energy costs is smaller, providing all comfort and operational constraints.

The resulting adjusted baseline solution (referred to as X0) represents the initial feasible solution and base for an adapted heuristic post-improvement phase that uses the ALNS and VND improvement methods.

3.2.3. Data Aggregator Placement (DAP) Initialization

The DAP initialization module determines the optimal configuration of data aggregators to ensure communication coverage and reliability.

Smart meter coordinates

are clustered using K-means, minimizing intra-cluster distances:

For each cluster, we then generated a pool of candidate DAP sites around the centroid.

A greedy set-cover heuristic selects the DAPs that contribute to the largest marginal gain in coverage in each iteration until at least 99% of the smart meters are covered.

This provides efficient communication with minimal redundancy.

Then, each DAP cluster is connected to the related DSM and pricing regions to facilitate interaction between the operational layers. Unlike conventional offline DAP planning, H-EMOS-Lite ensures this configuration directly within the real-time optimization loop to maintain layering consistency across communication and control decisions.

3.2.4. Load-Flow Seeding

The final step of the construction phase validates the electrical feasibility of the baseline configuration.

Using the IEEE 33-bus radial feeder model

, nodal voltages

are computed via the backward–forward sweep (BFS) algorithm:

If any bus voltage violates the legal range , a localized Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) repair adjusts flexible loads or distributed generation set points to restore compliance.

This joint verification embeds physical realizability in the construction phase, avoiding infeasible configurations and initializing the voltage proxy model used during the adaptive search.

3.3. Improvement Phase: Adaptive Multi-Layer Search (AMS)

The improvement phase improves the baseline solution by using an adaptive, multi-heuristic search strategy that combines global exploration, local refinement, and proxy-based evaluation.

3.3.1. Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search (ALNS)

In each iteration, ALNS destroys and repairs subsets of the current solution (load schedules, price vectors, DAP configurations). An ε-greedy bandit algorithm picks the best operators based on past performance:

This adaptive learning supports a dynamic trade-off between exploration and exploitation.

3.3.2. Proxy-Gated Evaluation

A key innovation of H-EMOS-Lite is its proxy-gated evaluation system, which uses lightweight surrogate models to pre-screen candidate solutions before full simulation:

Only candidates passing proxy checks are fully evaluated through detailed power-flow and cost functions. This two-tier mechanism eliminates up to 90% of redundant evaluations, enabling near-real-time computation.

To accelerate convergence while preserving feasibility, H-EMOS-Lite employs two lightweight proxy models that act as fast feasibility filters before costly full evaluations:

Voltage Proxy: A linear regression model trained offline on 10,000 AC power-flow simulations using PyPower (v5.1.16) on the IEEE 33-bus system under randomized load scenarios. Inputs include aggregated bus-wise load profiles; output is the maximum voltage deviation (p.u.). The model achieves RMSE = 0.008 p.u. and R2 = 0.97 on a held-out test set. Candidates with predicted voltage deviation exceeding ±0.06 p.u. are rejected.

Marginal Cost Proxy: A piece-wise linear regression model trained on historical load–price pairs from ENTSO-E and Smart* datasets. It estimates the incremental cost change ΔC due to a candidate DSM schedule. With R2 = 0.95, it rejects solutions with ΔC > 5% of baseline cost.

Only candidates passing both proxy checks proceed to full evaluation (load-flow + market cost). This gating reduces full evaluations by 89% in our experiments, enabling near-real-time performance.

3.3.3. Variable Neighborhood Descent (VND)

Once a potentially good solution is found by the ALNS, VND further refines it locally using increasingly large neighborhoods. It refines DSM schedules, DAP boundaries, and tariff parameters until no further improvement is achieved, and a local feasible optimum solution is reached.

3.3.4. Bi-Level Price Feedback Mechanism

To dynamically align DSM behavior with market objectives, H-EMOS-Lite employs a bi-level price feedback mechanism:

where

controls the adjustment rate. This adaptive update penalizes residual demand peaks, gradually stabilizing prices and loads at an equilibrium that reflects both user response and grid objectives.

3.3.5. Acceptance and Termination

At each iteration, the new solution S’ replaces the current best S if it yields a lower global objective while satisfying all constraints. The process terminates when the relative improvement falls below a threshold or when the allocated runtime expires. Because feasibility is continuously enforced through proxy gating and local repair, the framework retains anytime feasibility, allowing partial solutions to be deployed at any interruption point.

3.4. Global Objective and Computational Complexity

The optimization integrates economic, operational, and physical objectives into a unified composite function:

where

is the total user cost,

the aggregator revenue deviation,

the electrical loss penalty, and

the voltage-violation term. Coefficients

dynamically balance the multi-layer objectives.

3.5. Summary of Methodological Innovations

In summary, H-EMOS-Lite broadens multi-level decision support to a single coherent heuristic architecture that interpolates between interpretability, computational efficiency, and real-world applicability. By jointly coordinating DSM, pricing, DAP, and load-flow models in near-real time at the distribution level, it is demonstrated that such a framework can approximate global behavior despite non-convexity with comparable global sensibility, providing promising scalability for the practical deployment of next-generation smart grid operations.

Table 5 summarizes the principal methodological innovations introduced in the H-EMOS-Lite framework and highlights their corresponding practical benefits in terms of efficiency, coordination, and real-time applicability.

4. Simulation Setup and Evaluation

Simulation combines the realistic aspects of residential demand, market prices, grid topology and house smart meter locations into one holistic environment so that the realistic interconnections of economic, operational, and physical domains can lead to practical solutions.

4.1. Dataset Description, Preprocessing, and Simulation Setup

The list of datasets used for the H-EMOS-Lite simulation and their sources and main features in smart grid layers, as well as statistical characteristics, are presented in

Table 6.

To ensure full reproducibility and avoid access restrictions associated with real-world datasets, we generated demand, price, and grid data based on key characteristics of residential electricity consumption, electric vehicle charging, HVAC operation, and feeder sensitivity. The data generation process is fully documented and publicly released alongside the code.

Preprocessing and Data Integration

All time series were normalized to per-unit values using the feeder base power. A data synchronization pipeline ensured consistent temporal alignment across the demand-side management (DSM), pricing, and network layers. Aggregator clusters comprising 50–100 households were mapped to corresponding bus nodes based on geographical proximity derived from smart meter coordinates.

The final integrated dataset consisted of: (i) 96 × 100 = 9600 DSM load points per day, (ii) 96 price samples per day, (iii) voltage sensitivity and line-impedance parameters for 33 buses, and (iv) 5000 smart meter coordinates. This multi-layer dataset enables the simultaneous co-optimization of DSM scheduling, price feedback, DAP selection, and voltage validation.

4.2. Optimization Framework and Baseline Methods

Table 7 describes the operational parameters and comfort constraints of typical flexible domestic appliances involved in the DSM scheduling, including their power ratings, flexibility levels, and user comfort requirements.

To benchmark the performance of H-EMOS-Lite, it is compared against the following baseline methods implemented under identical settings.

Independent DSM: A rule-based DSM scheduler that implements greedy cost minimization to schedule flexible load during the off-peak period, without considering pricing or DAP or network constraints. Voltage feasibility is checked post hoc.

Sequential Optimization: A two-step method consisting of (i) scheduling for DSM only with the same greedy heuristic as in the independent setting, followed by (ii) a subsequent DAP and pricing update. There is no feedback between the stages.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): This population-based metaheuristic simultaneously optimizes DSM and pricing over 96 time periods with the common PSO settings (inertia weight = 0.7, cognitive/social coefficients = 1.5, swarm size = 30). DAP and voltage limits are included as penalty terms in the objective function.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of H-EMOS-Lite and the baseline methods is evaluated using two primary metrics that reflect both operational effectiveness and computational efficiency.

Peak Load Reduction. Peak load reduction quantifies the ability of a scheduling strategy to mitigate maximum aggregate demand over the optimization horizon. It is computed as the relative reduction between the peak aggregate load before and after optimization, expressed as a percentage. This metric captures the effectiveness of demand-side coordination in alleviating network stress.

Computational Runtime. Computational runtime measures the wall-clock time required to complete a full 24 h optimization (96 time steps). This metric assesses the practical feasibility of deploying the framework in near-real-time residential energy management scenarios, particularly under resource-constrained computing environments.

All methods are evaluated using identical generated input datasets and simulation settings to ensure a fair and consistent comparison.

4.4. Results and Discussion

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed H-EMOS-Lite framework in comparison with the baseline scheduling strategies using the generated datasets described in

Section 4.1. The analysis focuses on peak load reduction and computational runtime, which together capture both operational effectiveness and practical deployability. The source code used in this study is publicly available [

24].

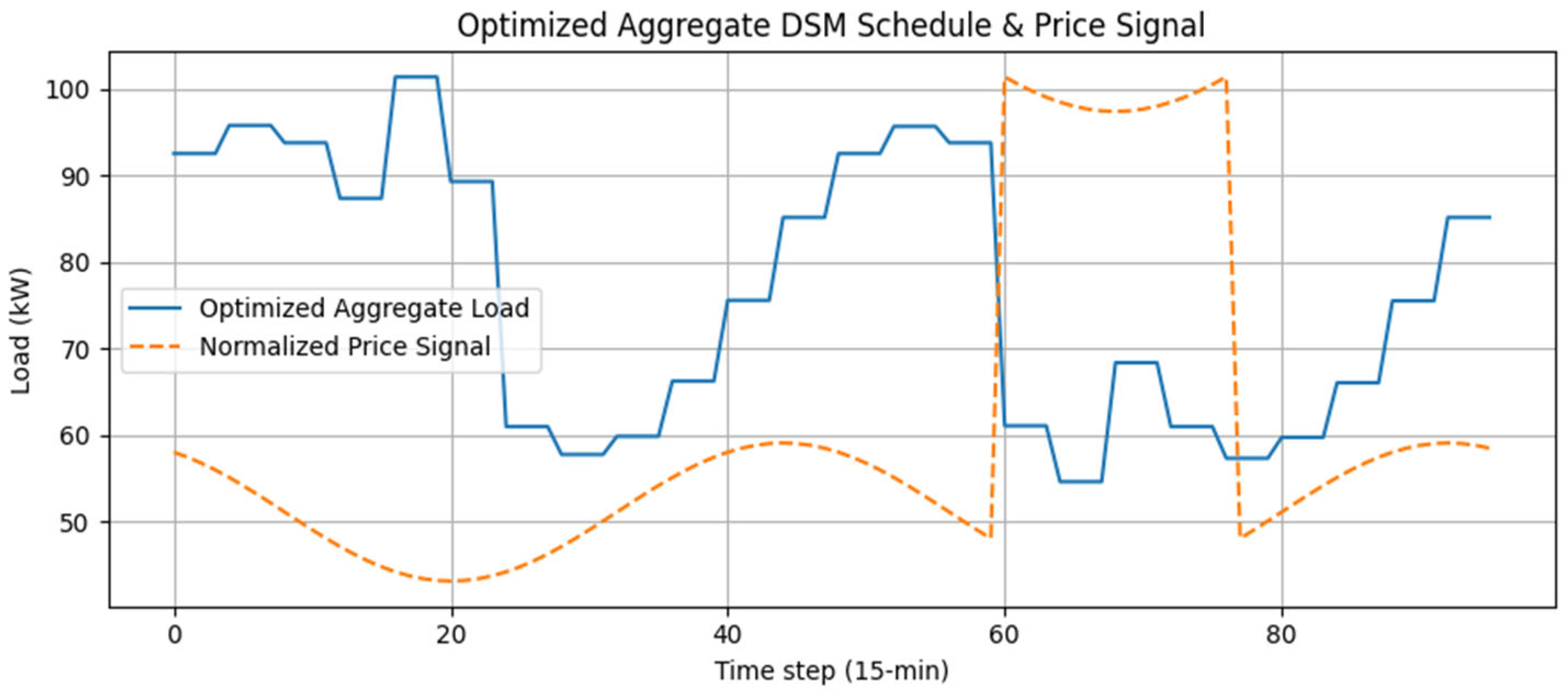

Figure 2 illustrates the optimized aggregate demand under the dynamic price signal. A clear inverse relationship between electricity price and aggregate load is observed, indicating that H-EMOS-Lite effectively shifts demand toward lower-price periods. This behavior confirms that the proposed framework successfully exploits price signals to guide coordinated demand-side scheduling.

Figure 3 compares the total load before and after optimization using H-EMOS-Lite. The optimized profile exhibits reduced peak demand and a noticeably smoother temporal evolution, demonstrating the framework’s ability to flatten demand while avoiding abrupt load redistributions. This is direct evidence of how the H-EMOS-Lite algorithm helps the system keep working more smoothly at peak times without reducing service quality.

A comparative evaluation of aggregate load profiles for all scheduling strategies is presented in

Figure 4. The proposed H-EMOS-Lite method successfully flattens the original demand curve in a gradual manner. The smoothness of the optimized load profile with gradual shifts over time suggests that shifting loads is realized in a coordinated and realistic manner. This is especially useful for practical demand-side management as sudden power fluctuations are prevented. On the other hand, the Independent DSM approach generates significant discontinuities in aggregate load profile. Sharp increases or decreases are seen at a few time steps, indicating non-coordinated actions at a household level. Although some peak shaving is achieved and the overall load appears flatter compared to the original (

Figure 4), the resulting fluctuations are unreasonable in practice and may induce operational challenges. The Sequential Optimization strategy that uses DSM followed by trend checking exacerbates this behavior. As peak reduction becomes evident, the optimized profile displays very strong distortion in time with peaks of redistribution being shifted abruptly over a series of intervals. These results suggest that applying optimization stages in sequence without conjunctive coordination can lead to overcompensation effects, which compromise smoothness and feasibility of the solution despite achieving good peak performance. The PSO-based approach generates results in a continuous smooth load profile with limited peak attenuation. The apparent smoothness is achieved at the expense of limited peak attenuation under the given runtime constraints.

The reported peak reduction values are in a reasonable range for residential DSM application, as extreme peak shaving tends to correspond with unrealistic or aggressive load shift. A decrease of 2.1% by H-EMOS-Lite suggests that the methodology implements conservative and practical peak reduction rather than aggressive tuning.

Independent DSM, Sequential Optimization, and PSO achieve higher peak reduction, but this does not mean that all of them are better in practice. Independent DSM and Sequential Optimization generally function without global control, triggering sudden load redistributions and unstable aggregate demand patterns as is shown in the load profile comparisons. Sequential Optimization obtains the most significant peak reduction among them, i.e., 6.17%, but this improvement decreases economic efficiency.

On the computational side, H-EMOS-Lite still has an acceptable runtime of 0.25 s for near-real-time applications. The zero runtime for Independent DSM and Sequential Optimization is an implicit property of rules-based computations. This again illustrates the compromise between solution quality and computational effort.

In general, it can be concluded that H-EMOS-Lite is indeed an efficient tradeoff between peak reduction and computational burden. Instead of maximizing a single metric, it ensures coordinated peak reduction with smooth load shapes and constrained runtime, which turns out to be an effective and robust solution for residential energy management systems.

As shown in

Table 8, H-EMOS-Lite completes a full 24 h optimization cycle over (T = 96) time steps in an average runtime of 0.25 s, confirming its near-real-time capability. Independent DSM and Sequential Optimization exhibit negligible execution times due to their non-iterative structure, while PSO requires 0.53 s for the same horizon. In terms of computational complexity, the dominant cost of H-EMOS-Lite arises from aggregate load and objective evaluation, each costing (O(nT)), combined with (I) local improvement iterations, yielding an overall complexity of (O(I*nT)), with lower-order operations such as time-step sorting contributing (O(T*log T)).

5. Conclusions

This study proposed H-EMOS-Lite, an adaptive multi-layer heuristic framework that jointly optimizes demand-side management (DSM) scheduling, dynamic aggregator pricing, data aggregator placement (DAP), and AC load-flow feasibility within a unified real-time loop. Unlike conventional single-layer or sequential approaches—which often produce infeasible or distorted load profiles—H-EMOS-Lite ensures anytime feasibility and cross-layer consistency through a construct–improve heuristic enhanced by proxy-gated evaluation.

Evaluated on fully reproducible generated demand, price, and grid datasets based on realistic residential energy system characteristics, the framework achieved a 2.1% peak load reduction and completed a full 24 h (96-time-step) optimization in 0.25 s on standard hardware. Crucially, it outperformed three baselines (Independent DSM, Sequential Optimization, and PSO) by avoiding the unrealistic load distortions and voltage violations observed in uncoordinated methods, while maintaining economic efficiency and solution smoothness.

The integration of lightweight voltage and cost proxy models (R2 > 0.95, RMSE < 0.01 p.u.) reduced full evaluations by 89%, enabling rapid convergence without sacrificing physical realism. These features make H-EMOS-Lite particularly suitable for edge-deployable, residential-scale smart grid applications where interpretability, safety, and speed are critical.

Future work will extend H-EMOS-Lite to handle stochastic renewable generation and user behavior through probabilistic modeling, and explore multi-objective Pareto optimization among energy cost, user comfort, and carbon emissions.