A Hybrid Energy Storage System and the Contribution to Energy Production Costs and Affordable Backup in the Event of a Supply Interruption—Technical and Financial Analysis †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Energy Storage Systems

- Minimizing the variability of energy production.

- Enhancing the reliability of energy supply.

- Maximizing the utilization of wind and solar resources.

- Contributing for grid stability.

- Creating opportunities for additional revenue.

- Reducing operational and maintenance costs.

- Contributing to sustainability goals.

2.1. Types of Storage Systems

Comparison of Storage Batteries

2.2. Case Implementation

- South Australia—Hornsdale Power Reserve [40]: This project uses Tesla lithium-ion batteries systems. It ensures grid stability and provides backup power with rapid response to fluctuations in renewable energy production.

- Morocco—Noor Complex [41]: It is one of the biggest solar energy installations equipped with thermal energy storage. Using parabolic collectors, they focus on the sunlight to generate power and heat. Surplus heat is stored in molten-salt reservoirs, and it is used at night or on overcast days allowing for electricity production.

- Australia—Yandin wind farm [42]: It is one of the biggest wind installations in Western Australia. It incorporates an energy storage system based on lithium-ion battery to ensure grid reliability and optimize the renewable energy production.

- Switzerland—Nant de Drance [43]: It is a pumped-storage hydroelectric project located in the Swiss Alps. This system uses a pair of artificial reservoirs on different elevation planes. The water is pumped upwards during the period of surplus production, and it is released to produce energy when it is needed, enhancing the stability and the fluctuation of the renewable energy.

- Portugal: In Portugal, the most common storage facilities are based on electric pumping, as is the case with the Baixo Sabor (downstream), Alto Rabagão, Vilarinho das Furnas, Torrão, Baixo Sabor (upstream), Frades I and II, Salamonde II, Foz do Tua, Aguieira, Alqueva, and Vendas Novas III units. From the point of view of battery storage, the facilities in Évora (lithium ions) [44] and Alcoutim [45] are noteworthy.

3. Implementation of the Case Study

3.1. Overview of the Wind Farm

3.2. Energy Quantification

3.2.1. Hybridization

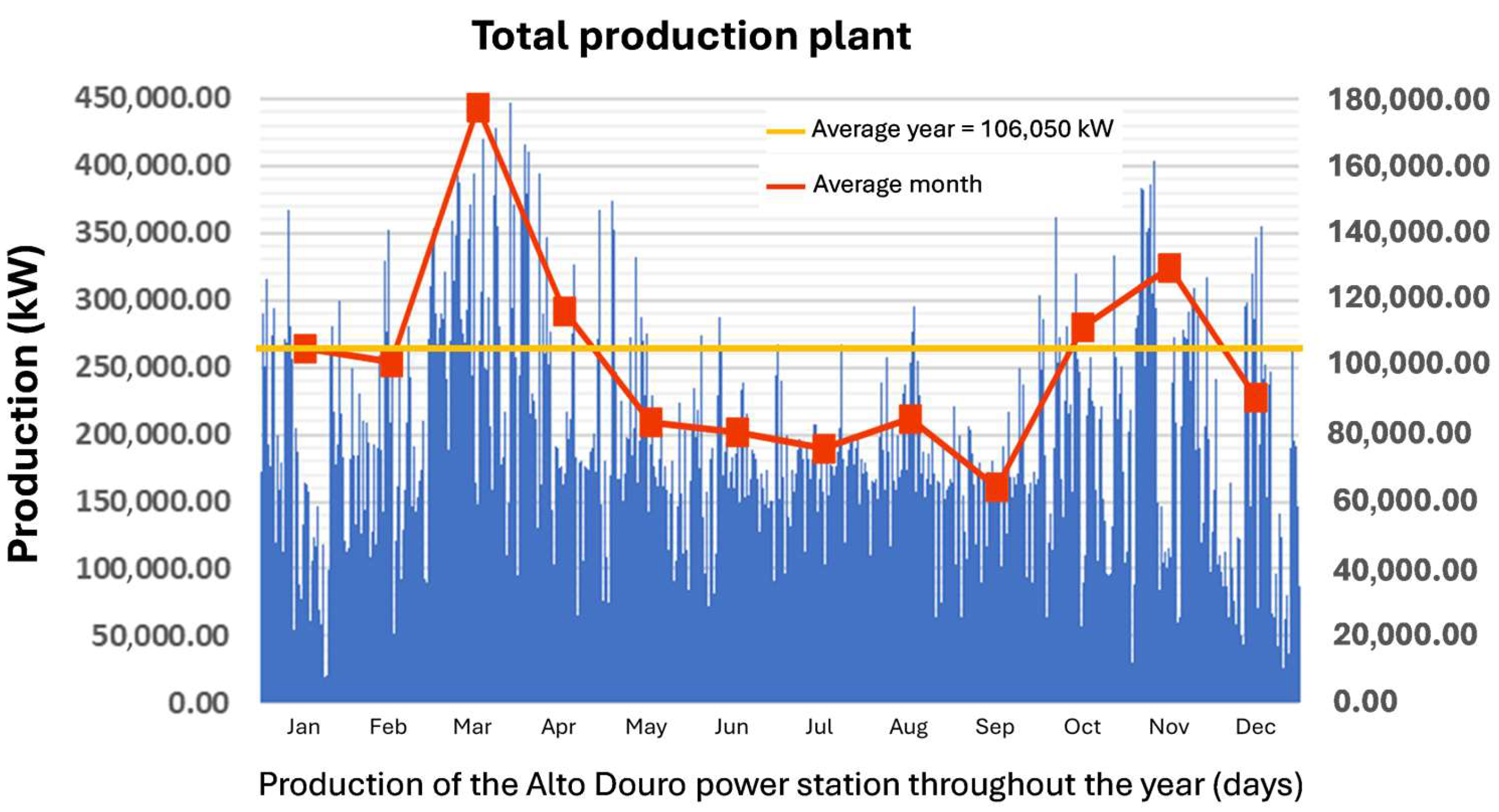

3.2.2. Total Production

4. Simulation of Storage System Performance

4.1. Curtailment

- Scenario A—This is considered a very optimistic scenario. It does not consider the limitation of daily cycles. Priority is given to releasing the stored energy as quickly as possible. The main objective is to discharge the batteries whenever feasible, particularly during low production periods when output falls below the export limit.

- Scenario B—This is the most realistic scenario. It assumes that the batteries are fully charged before the discharged process is carried out. In this case, unlike scenario A, the limits of the storage cycles are respected. With this procedure, it is possible to extend the life cycle of batteries as much as possible [58]. This is a scenario which, although it presents slightly lower profits than scenario A, is essentially aimed at satisfying the daily charge/discharge cycles of the batteries.

- The complete charge/discharge cycles of the batteries may not be carried out in full. This is due to varying weather conditions which, although they can lead to incomplete charging of the batteries, lead to more advantageous operating conditions, i.e., cases in which there may not be any cuts for a long time.

- The energy charged in a 15 min period will be considered to correspond to the maximum charge cycle, even if it is less than the battery’s capacity in that period. This phenomenon is not very relevant, as it will occur sporadically.

- The absence of a daily cycle limit which, if exceeded, will lead to a decrease in battery efficiency or even damage. On the other hand, these batteries will only be used for storing curtailment, so we cannot consider this a disadvantage as they will not be overused to achieve this goal.

4.2. Battery Storage Price Arbitrage

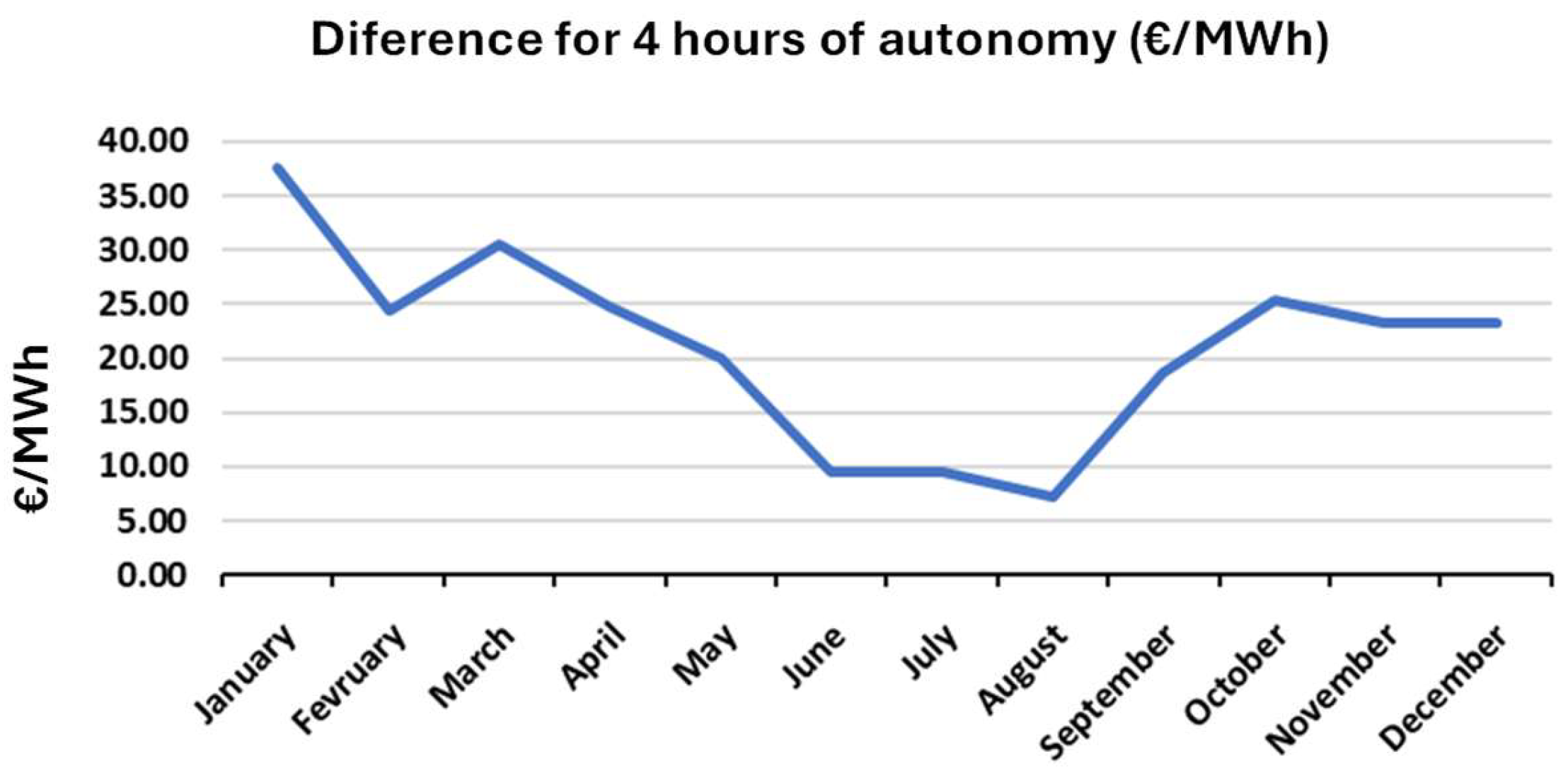

4.2.1. Battery with 4 h of Autonomy

4.2.2. Battery with 2 h of Autonomy

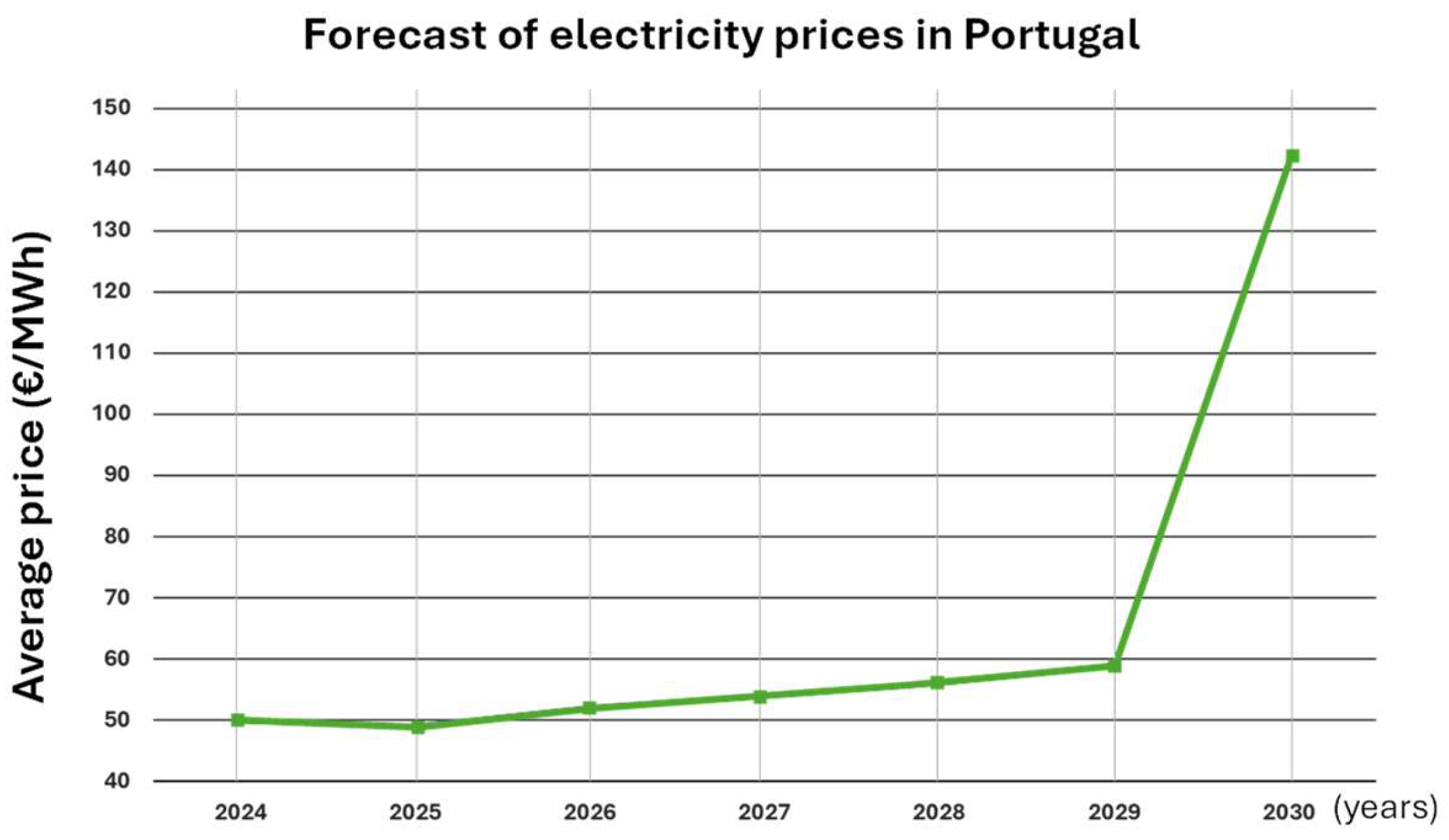

4.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of the Project

4.2.4. Evaluation of the Future Curtailment

4.3. Curtailment as an Accessible Backup

5. Conclusions

- The idea that lithium-ion batteries, currently used in hybrid power plants (wind and solar farms) to store surplus energy, are the most suitable technology was reinforced. The choice validates this assumption due to their high energy storage capacity, their modularity, which is fundamental to the project’s growth, and their long-life cycle, and the knowledge of Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) and Operational and Maintenance Costs (OPEX), or discount rate used. This decision is in line with many other similar projects that highlight the advantages of using lithium-ion batteries.

- Based on the data collected, it can also be concluded that the combined energy produced by the wind farm rarely exceeds the limits for export to the national grid over the course of a year. The average curtailment rate is around 2.5% of the total energy produced and is in line with European renewable energy projects [69] in the Nordic energy system [70] and with wind curtailment in the US, Canada, and China [71]. These are also in line with the results obtained by the system dynamics model developed by [72], which estimates a reduction of between 500 and 3000 GWh by 2030, i.e., a curtailment between 2.5 and 14%.

- Batteries with shorter daily operating cycles have proved to be the most cost-effective, if the operating conditions are the same: energy storage capacity, power capacity, and the same daily charge−discharge cycles. This is because the surplus energy limit is rarely reached, albeit in large quantities, which makes a battery with a high energy capacity and fast charge−discharge cycles the most suitable for the project, in line with various installations and scientific literature, which validates the energy producer’s choice (Finerge). The greatest profit is obtained from the one that operates with the highest energy capacity and the shortest autonomy time.

- The efficiency of the battery selected is extremely important. This is due not only to the profit that can be made in the price arbitrage process for the project viability, but also to the strong dependence of efficiency on the performance of the selected battery. At this stage of the project, efficiency was considered the most important variable in the study, rather than CAPEX and OPEX.

- An additional conclusion is that energy storage will become a very important advantage for supplying energy to priority organizations, and when properly integrated into the national grid, can serve as a support for the restart protocol or as an accessible backup, if parameters such as power and energy capacity, integration, and others are specified. In the event of a blackout on 28 April 2025, the existence of small producers or even national producers has become very important in personal terms, since systems like [9] can continue to benefit from solar energy as well as energy stored overnight. On the other hand, it facilitates price arbitrage by taking advantage of fluctuations in daily electricity [73].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APREN—Associação Portuguesa de Energias Renováveis. Anuário 2024 APREN, July 2024. Available online: https://www.apren.pt/pt/publicacoes/apren/anuario-apren-2024 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Kaldellis, J.K.; Zafirakis, D. Optimum energy storage techniques for the improvement of renewable energy sources-based electricity generation economic efficiency. Energy 2007, 32, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, G.R. Are renewable energy technologies cost competitive for electricity generation? Renew. Energy 2021, 180, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, O.; Kuznietsov, M.; Hutsol, T.; Mudryk, K.; Herbut, P.; Vieira, F.M.C.; Mykhailova, L.; Sorokin, D.; Shevtsova, A. Modeling a Hybrid Power System with Intermediate Energy Storage. Energies 2023, 16, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finerge Homepage. Available online: https://www.finerge.pt/pt/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Dumlao, S.M.G.; Ishihara, K.N. Impact assessment of electric vehicles as curtailment mitigating mobile storage in high PV penetration grid. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Europeu Conselho da União Europeia. Acordo de Paris Sobre Alterações Climáticas. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pt/policies/climate-change/paris-agreement/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Pereira, F.; Caetano, N.S.; Felgueiras, C. Increasing energy efficiency with a smart farm-An economic evaluation. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Pereira, F.; da Silva, A.F.; Caetano, N.; Felgueiras, C.; Machado, J. Electrification of a Remote Rural Farm with Solar Energy-Contribution to the Development of Smart Farming. Energies 2023, 16, 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Santos, A.A.; da Silva, A.F.; Caetano, N.S.; Felgueiras, C. Automation, Project and Installation of Photovoltaic System in a Rural Farm, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Energy and Environment Research (ICEER 2022) Environmental Science and Engineering, Porto, Portugal, 12–16 September 2022; Caetano, N.S., Felgueiras, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 493–503. [CrossRef]

- Atawi, I.E.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Magableh, A.M.; Albalawi, O.H. Recent Advances in Hybrid Energy Storage System Integrated Renewable Power Generation: Configuration, Control, Applications, and Future Directions. Batteries 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Feng, Y.; Zanocco, C.; Flora, J.; Majumdar, A.; Rajagopal, R. Solar and battery can reduce energy costs and provide affordable outage backup for US households. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 1025–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APREN. Apagão Elétrico de 28 de Abril de 2025 Statement. Available online: https://www.apren.pt/contents/communicationpressrelease/apren-apagao-statement-pt.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sayed, E.T.; Olabi, A.G.; Alami, A.H.; Radwan, A.; Mdallal, A.; Rezk, A.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Renewable Energy and Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Oliveira, M. Curso Técnico Instalador de Energia Solar Fotovoltaica, 2nd ed.; Publindústria: Porto, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, N.A.; Jenkins, J.D.; Edington, A.; Mallapragada, D.S.; Lester, R.K. The design space for long-duration energy storage in decarbonized power systems. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, P.E.; Thornton, H.E. The climatological relationships between wind and solar energy supply in Britain. Renew. Energy 2016, 87, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Perron, J. Energy storage systems—Characteristics and comparisons. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney, M.S.; Tepe, Y. Classification and assessment of energy storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, C.; Xavier, C.; Magalhães, A.; Pereira, F.A.D.S.; Santos, A. Comprehensive Analysis of an Energy Storage System for the Alto Douro Wind Power Plant, Encompassing Wind and Solar Energy Integration: A Study of Technical and Financial Aspects. Preprints 2023, 2023111576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrouche, S.O.; Rekioua, D.; Rekioua, T.; Bacha, S. Overview of energy storage in renewable energy systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 20914–20927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Wilberforce, T.; Ramadan, M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Alami, A.H. Compressed air energy storage systems: Components and operating parameters—A review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Al-Hadhrami, L.M.; Alam, M.M. Pumped hydro energy storage system: A technological review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, A.; Galán-Casado, S.; Caballero, Á.; Serena, S. Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani-Sanij, A.R.; Tharumalingam, E.; Dusseault, M.B.; Fraser, R. Study of energy storage systems and environmental challenges of batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetokun, B.B.; Oghorada, O.; Abubakar, S.J. Superconducting magnetic energy storage systems: Prospects and challenges for renewable energy applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwayemi, T.M.; Tomomewo, S.O.; Choudhary, S.; Boakye-Danquah, D.K. Hybrid Energy Storage Systems for Renewable Integration: Combining Batteries, Supercapacitors, and Flywheels. Int. J. Latest Technol. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2025, 14, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Kaur, H.; Thakur, A.; Thakur, R.C.; Dosanjh, H.S. Hybrid Lithium Electrolytes as Potential Electrolytes for Energy Storage Devices: A Pathway to Sustainable and High-Efficiency Solutions. Top. Catal. 2025, 68, 2356–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wei, Y.-L.; Cao, P.-F.; Lin, M.-C. Energy storage system: Current studies on batteries and power condition system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3091–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, D.A.J.; Moseley, P.T. Energy Storage with Lead–Acid Batteries. In Electrochemical Energy Storage for Renewable Sources and Grid Balancing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C. Lead-acid battery energy-storage systems for electricity supply networks. J. Power Sources 2001, 100, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Lippert, M. Chapter 14–Nickel–Cadmium and Nickel–Metal Hydride Battery Energy Storage. In Electrochemical Energy Storage for Renewable Sources and Grid Balancing; Moseley, P.T., Garche, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Cao, J.; Gu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F.; Lin, Z. Research on sodium sulfur battery for energy storage. Solid State Ion. 2008, 179, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Savinell, R.F. Flow Batteries. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2010, 19, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jin, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, A.; Liu, M.; Chen, B.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Q. Applications of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Grid-Scale Energy Storage Systems. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2020, 26, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.L.; Nazar, L.F. Sodium and sodium-ion energy storage batteries. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2012, 16, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, B.; Pode, R. Potential of lithium-ion batteries in renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaralizadeh, S.; Banerjee, P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Famouri, P. Battery Energy Storage Systems: A Review of Energy Management Systems and Health Metrics. Energies 2024, 17, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurecon. Hornsdale Power Reserve. Available online: https://hornsdalepowerreserve.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Aurecon-Hornsdale-Power-Reserve-Impact-Study-year-1.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- World Bank Group. Morocco: Noor Ouarzazate Concentrated Solar Power Complex. Available online: https://ppp.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/MoroccoNoorQuarzazateSolar_WBG_AfDB_EIB.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Power Technology. Yandin Wind Farm, Shire of Dandaragan, Australia. Available online: https://www.power-technology.com/projects/yandin-wind-farm-shire-of-dandaragan-australia/?cf-view (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Nant de Drance. Nant de Drance, One of Europe’s Most Powerful Pumped Storage Power Plants. Available online: https://www.nant-de-drance.ch/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Observatório da Energia. Armazenamento de Energia em Portugal. 2021. Available online: https://www.observatoriodaenergia.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ESTUDO-ARMAZENAMENTO-DE-ENERGIA_Texto_Final_revisto-OBS-v2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Galp/Powin. Galp e Powin Instalam Sistema de Baterias de Energia de Grande Escala em Portugal. 2025. Available online: https://www.galp.com/corp/Portals/0/Comunicados_Media/2024/Fevereiro/07_02_2024_PR_GALP_Powin_PT.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Felgueiras, C.; Magalhães, A.; Xavier, C.; Pereira, F.; Santos, A.A.; da Silva, A.F.; Silva, P.; Caetano, N.; Machado, J. An Energy Storage System for the Alto Douro Wind Power Plant: A Technical Study. In Renewable Energy Towards Decarbonization (ICEER 2024); Environmental Science and Engineering; Caetano, N., Felgueiras, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.T. Análise Técnico-Financeira de um Sistema de Armazenamento de Energia Para a Central Eólica do Alto Douro, Sobre Equipada (Eólica) e Hibridizada (Solar). Master’s Thesis, ISEP, Polytechnic of Porto (P.Porto), Porto, Portugal, 2023. Available online: https://recipp.ipp.pt/entities/publication/0ea3fde5-8674-4efe-a74b-eae32e6b2ff9 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Kim, A.K. Recent development in fire suppression systems. Fire Saf. Sci. 2001, 5, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4MW Platform. 2024. Vestas Wind Systems A/S. Available online: https://www.vestas.com/content/dam/vestas-com/global/en/brochures/onshore/4MW_Platform_Brochure.pdf.coredownload.inline.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Technical Documentation Wind Turbine Generator Systems Cypress 158-50/60Hz, Rev. 07-Doc-0075288-EN. 2021. General Electric Company, Renewable Energy. Available online: https://commissiemer.nl/projectdocumenten/013935_3516_B5.6_GE_General_Description_Cypress-158_AVG_conform.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Lente, G.; Ősz, K. Barometric formulas—Various derivations and comparisons to environmentally relevant observations. ChemTexts 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA Homepage, Mapas e Gráficos. Available online: https://www.ipma.pt/pt/oclima/monitorizacao/index.jsp?selTipo=m&selVar=tt&selAna=me&selAno=-1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Liu, B.; Ma, X.; Guo, J.; Li, H.; Jin, S.; Ma, Y.; Gong, W. Estimating hub-height wind speed based on a machine learning algorithm—Implications for wind energy assessment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 3181–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). ArcGIS Web Application. Nasa.gov. Available online: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/ (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Repsol, Quantos kWh Consome uma Família em Portugal. Available online: https://www.repsol.pt/particulares/assessoramento/quantos-kwh-consome-uma-familia/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- REN, Preços Mercado Spot—Portugal e Espanha Homepage. Available online: https://mercado.ren.pt/PT/Electr/InfoMercado/InfOp/MercOmel/paginas/precos.aspx (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos (ERSE)—Atividade. Available online: https://www.erse.pt/atividade/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Curry, C. Lithium-Ion Battery Costs and Market—Squeezed Margins Seek Technology Improvements & New Business Models; Bloomberg New Energy Finance: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://roar-assets-auto.rbl.ms/documents/36549/BNEF-Lithium-ion-battery-costs-and-market.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Park, W.-H.; Abunima, H.; Glick, M.B.; Kim, Y.-S. Energy Curtailment Scheduling MILP Formulation for an Islanded Microgrid with High Penetration of Renewable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Baek, S.-M.; Park, J.-W. Selection of Inertial and Power Curtailment Control Methods for Wind Power Plants to Enhance Frequency Stability. Energies 2022, 15, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kies, A.; Schyska, B.U.; Von Bremen, L. Curtailment in a Highly Renewable Power System and Its Effect on Capacity Factors. Energies 2016, 9, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baringa Homepage, Portugal: Wholesale Electricity Market Report. Available online: https://www.baringa.com/en/industries/energy-resources/power-market-projections/portugal-wholesale-electricity-market-report/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- OMIE. Relatório Anual 2024 da Evolução do Mercado da Eletricidade. Available online: https://www.omie.es/sites/default/files/2025-02/informe-anual-pt.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Cole, M.; Campos-Gaona, D.; Stock, A.; Nedd, M. A Critical Review of Current and Future Options for Wind Farm Participation in Ancillary Service Provision. Energies 2023, 16, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, J. Expresso, Apagão de Abril: Um Sinal de Alarme Para o Sistema Elétrico Nacional. 2025. Available online: https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2025-05-07-apagao-de-abril-um-sinal-de-alarme-para-o-sistema-eletrico-nacional-90af258f (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Jing, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, A.; Meng, X. Construction of pumped storage power stations among cascade reservoirs to support the high-quality power supply of the hydro-wind-photovoltaic power generation system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 323, 119239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, B.; Qureshi, W.A.; Nair, N.K.C. Renewable generation and its integration in New Zealand power system. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Miao, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Tan, H. A black-start strategy for active distribution networks considering source-load bilateral uncertainty and multi-type resources. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 238, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METIS Studies, Study S11. Effect of High Shares of Renewables on Power Systems, Technical Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329060624_Effect_of_high_shares_of_renewables_on_power_systems/figures?lo=1 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Nycander, E.; Söder, L.; Olauson, J.; Eriksson, R. Curtailment analysis for the Nordic power system considering transmission capacity, inertia limits and generation flexibility. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 942–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.; Bird, L.; Carlini, E.M.; Eriksen, P.B.; Estanqueiro, A.; Flynn, D.; Fraile, D.; Lázaro, E.G.; Martín-Martínez, S.; Hayashi, D.; et al. C-E (curtailment—Energy share) map: An objective and quantitative measure to evaluate wind and solar curtailment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M. Renewable energy curtailment: A problem or an opportunity? Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskas, N.; Kapustin, V. Battery Scheduling Optimization and Potential Revenue for Residential Storage Price Arbitrage. Batteries 2024, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliamentary Research Service. Portugal’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan. 2025. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/729408/EPRS_BRI(2022)729408_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Dumlao, S.M.G.; Ishihara, K.N. Dynamic Cost-Optimal Assessment of Complementary Diurnal Electricity Storage Capacity in High PV Penetration Grid. Energies 2021, 14, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time of Register [h] | Armamar | Armamar II | Serra da Nave | Testos II | Chavães | Serra de Sampaio-Ranhados | Sendim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00:15 | 10 | 0 | 5970 | 2080 | 550 | 1060 | 320 |

| 00:30 | 10 | 90 | 6120 | 2160 | 750 | 1300 | 760 |

| 00:45 | 100 | 130 | 7090 | 2120 | 800 | 1050 | 840 |

| 01:00 | 60 | 140 | 7090 | 1880 | 900 | 1710 | 1040 |

| 01:15 | 160 | 30 | 6700 | 1400 | 630 | 2400 | 680 |

| 01:30 | 240 | 150 | 5740 | 1400 | 1150 | 1440 | 2360 |

| 01:45 | 490 | 20 | 5980 | 1560 | 1890 | 2350 | 2560 |

| 02:00 | 90 | 0 | 7370 | 1640 | 1460 | 2670 | 1040 |

| 02:15 | 20 | 0 | 6930 | 1640 | 1120 | 2550 | 680 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Wind Speed [m/s] | Air Density (ρ) [kg/m3] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.050 | 1.067 | 1.074 | 1.075 | 1.082 | 1.097 | 1.100 | 1.104 | 1.112 | 1.120 | 1.136 | 1.150 | |

| Electrical Power for the Vestas Model in kW | ||||||||||||

| 3.0 | 62.0 | 64.0 | 64.9 | 65.0 | 65.6 | 66.8 | 67.0 | 67.5 | 68.4 | 69.4 | 71.3 | 73.0 |

| 3.1 | 77.6 | 79.9 | 80.9 | 81.0 | 81.7 | 83.1 | 83.4 | 83.9 | 85.0 | 86.1 | 88.2 | 90.0 |

| 3.2 | 93.2 | 95.8 | 96.8 | 97.0 | 97.8 | 99.5 | 99.8 | 100.4 | 101.6 | 102.8 | 105.1 | 107.0 |

| 3.3 | 108.8 | 111.7 | 112.8 | 113.0 | 113.9 | 115.8 | 116.2 | 116.9 | 118.2 | 119.6 | 122.0 | 12.0 |

| 3.4 | 124.4 | 127.5 | 128.8 | 129.0 | 130.0 | 132.2 | 132.6 | 133.3 | 134.8 | 136.3 | 138.9 | 141.0 |

| 3.5 | 140.0 | 143.4 | 144.8 | 145.0 | 146.1 | 148.5 | 149.0 | 149.8 | 151.4 | 153.0 | 155.8 | 158.0 |

| 3.6 | 159.4 | 163.1 | 164.6 | 164.8 | 166.1 | 168.8 | 169.4 | 170.3 | 172.0 | 173.7 | 176.7 | 179.2 |

| 3.7 | 178.8 | 182.7 | 184.4 | 184.6 | 186.1 | 189.2 | 189.8 | 190.7 | 192.6 | 194.4 | 197.7 | 200.4 |

| 3.8 | 198.2 | 202.4 | 204.2 | 204.4 | 206.0 | 209.5 | 210.2 | 211.2 | 213.2 | 215.2 | 218.7 | 221.6 |

| 3.9 | 217.6 | 222.1 | 223.9 | 224.2 | 226.0 | 229.8 | 230.6 | 231.7 | 233.8 | 235.9 | 239.7 | 241.8 |

| 4.0 | 237.0 | 241.8 | 243.7 | 244.0 | 246.0 | 250.2 | 251.0 | 252.1 | 254.4 | 256.6 | 260.6 | 261.0 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Wind Speed [m/s] | Air Density (ρ) [kg/m3] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.050 | 1.067 | 1.074 | 1.075 | 1.082 | 1.097 | 1.100 | 1.104 | 1.112 | 1.120 | 1.136 | 1.150 | |

| Electrical Power for the GE Model in kW | ||||||||||||

| 3.0 | 58.0 | 58.7 | 59.4 | 60.0 | 60.3 | 62.6 | 63.0 | 63.4 | 64.2 | 65.0 | 66.6 | 67.0 |

| 3.1 | 75.0 | 75.8 | 76.7 | 77.4 | 77.7 | 80.1 | 80.6 | 81.1 | 82.0 | 83.0 | 84.8 | 85.2 |

| 3.2 | 92.0 | 93.0 | 94.0 | 94.8 | 95.1 | 97.7 | 98.2 | 98.8 | 99.9 | 101.0 | 102.9 | 103.4 |

| 3.3 | 109.0 | 110.1 | 111.2 | 112.2 | 112.6 | 115.3 | 115.8 | 116.4 | 117.7 | 119.0 | 121.1 | 121.6 |

| 3.4 | 126.0 | 127.3 | 128.5 | 129.6 | 130.0 | 132.8 | 133.4 | 134.1 | 135.6 | 137.0 | 139.2 | 139.8 |

| 3.5 | 143.0 | 144.4 | 154.8 | 147.0 | 147.4 | 150.4 | 151.0 | 151.8 | 153.4 | 155.0 | 157.4 | 158.0 |

| 3.6 | 164.8 | 166.3 | 167.9 | 169.2 | 169.6 | 173.9 | 173.6 | 174.5 | 176.2 | 178.0 | 180.9 | 181.6 |

| 3.7 | 186.6 | 188.3 | 190.0 | 191.4 | 191.9 | 195.5 | 196.2 | 197.2 | 199.1 | 201.0 | 204.4 | 205.2 |

| 3.8 | 208.4 | 210.2 | 212.0 | 213.6 | 214.1 | 218.0 | 218.8 | 219.8 | 221.9 | 224.0 | 227.8 | 228.8 |

| 3.9 | 230.2 | 232.2 | 234.1 | 235.8 | 236.4 | 240.6 | 241.4 | 242.5 | 244.8 | 247.0 | 251.3 | 252.4 |

| 4.0 | 252.0 | 254.1 | 256.2 | 258.0 | 258.6 | 263.1 | 264.0 | 265.2 | 267.6 | 270.0 | 274.8 | 276.0 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Month | Day | Hour | Irradiation [Wh/m2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ⋮ | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 1.1 |

| 1 | 1 | 9 | 199.3 |

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 802.7 |

| 1 | 1 | 11 | 1331.3 |

| 1 | 1 | 12 | 1688.6 |

| 1 | 1 | 13 | 1809.8 |

| 1 | 1 | 14 | 1682.6 |

| 1 | 1 | 15 | 1402.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 16 | 921.2 |

| 1 | 1 | 17 | 320.6 |

| 1 | 1 | 18 | 1.5 |

| 1 | 1 | 19 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | ⋮ | 0.0 |

| Month | Day | Hour | Irradiation [Wh/m2] | Production per Panel [Wh] | Production [kWh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ⋮ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 9 | 55.0 | 25.4 | 7424.6 |

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 223.0 | 102.9 | 30,103.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 11 | 370.0 | 170.7 | 49,947.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 12 | 469.0 | 216.3 | 63,311.7 |

| 1 | 1 | 13 | 503.0 | 232.0 | 67,901.5 |

| 1 | 1 | 14 | 467.0 | 215.4 | 63,041.7 |

| 1 | 1 | 15 | 390.0 | 179.9 | 52,647.3 |

| 1 | 1 | 16 | 256.0 | 118.1 | 34,558.2 |

| 1 | 1 | 17 | 89.0 | 41.0 | 12,014.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | 19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1 | ⋮ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Production [kWh] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Armamar | Armamar II | Serra da Nave | Testos II | Chavães | Serra de Sampaio Ranhados | Sendim | Overproduction Equipment 43 MW | Hybridization 180 MW | Total | Curtailment [kWh] |

| 09:00 | 27,200 | 9200 | 37,460 | 47,840 | 17,520 | 25,800 | 19,560 | 32,769.9 | 5535.0 | 222,884.9 | 0.0 |

| 09:15 | 23,870 | 9200 | 38,510 | 47,560 | 15,420 | 27,290 | 20,640 | 23,618.8 | 5535.0 | 211,643.8 | 0.0 |

| 09:30 | 21,470 | 9630 | 40,460 | 46,440 | 19,870 | 24,010 | 15,120 | 17,629.0 | 5535.0 | 200,164.0 | 0.0 |

| 09:45 | 20,190 | 9160 | 38,180 | 42,560 | 21,660 | 21,620 | 11,760 | 16,269.3 | 5535.0 | 187,934.3 | 0.0 |

| 10:00 | 19,240 | 7940 | 37,060 | 38,880 | 23,440 | 20,770 | 14,080 | 22,036.6 | 35,424.1 | 218,870.7 | 0.0 |

| 10:15 | 21,710 | 4990 | 35,470 | 35,040 | 22,690 | 24,270 | 18,000 | 35,192.0 | 35,424.1 | 232,786.1 | 0.0 |

| 10:30 | 24,400 | 5380 | 34,600 | 39,040 | 25,640 | 26,760 | 25,080 | 40,818.2 | 35,424.1 | 257,142.3 | 3942.2 |

| 10:45 | 23,000 | 6830 | 34,180 | 42,240 | 26,940 | 28,340 | 25,640 | 24,439.0 | 35,424.1 | 247,033.1 | 0.0 |

| 11:00 | 22,540 | 6550 | 32,220 | 42,920 | 23,820 | 27,060 | 25,040 | 18,308.9 | 42,804.1 | 241,263.0 | 0.0 |

| 11:15 | 24,050 | 6420 | 25,510 | 43,640 | 23,110 | 28,470 | 24,160 | 28,601.7 | 42,804.1 | 246,765.8 | 0.0 |

| 11:30 | 23,140 | 7700 | 27,400 | 42,240 | 24,670 | 30,310 | 29,840 | 25,259.1 | 42,804.1 | 253,363.2 | 163.2 |

| 11:45 | 22,860 | 8310 | 32,350 | 43,040 | 26,990 | 31,040 | 30,720 | 22,798.6 | 42,804.1 | 260,912.7 | 7712.7 |

| 12:00 | 20,650 | 9160 | 31,860 | 40,400 | 28,120 | 32,290 | 33,040 | 21,274.7 | 46,678.6 | 263,473.3 | 19,273.2 |

| 12:15 | 20,430 | 9160 | 29,320 | 35,200 | 23,660 | 30,960 | 28,880 | 11,559.2 | 46,678.6 | 235,847.8 | 0.0 |

| 12:30 | 18,890 | 6480 | 26,240 | 33,080 | 17,940 | 30,380 | 23,000 | 16,269.3 | 46,678.6 | 218,957.9 | 0.0 |

| 12:45 | 13,720 | 4350 | 28,200 | 32,280 | 18,580 | 31,880 | 21,680 | 30,304.0 | 46,678.6 | 227,672.6 | 0.0 |

| 13:00 | 18,960 | 4440 | 29,520 | 31,800 | 18,920 | 31,840 | 23,320 | 25,259.1 | 65,866.6 | 249,925.7 | 0.0 |

| 13:15 | 22,710 | 6040 | 27,280 | 33,200 | 20,650 | 31,860 | 26,360 | 16,269.3 | 65,866.6 | 251,135.9 | 0.0 |

| 13:30 | 21,060 | 5710 | 29,490 | 31,080 | 19,680 | 32,720 | 21,160 | 28,601.7 | 65,866.6 | 256,368.3 | 3168.3 |

| 13:45 | 23,180 | 4610 | 34,190 | 32,080 | 22,820 | 32,760 | 24,760 | 39,543.7 | 65,866.6 | 279,810.3 | 26,610.3 |

| 14:00 | 23,390 | 3910 | 35,050 | 34,160 | 27,060 | 32,230 | 34,640 | 49,818.2 | 85,608.1 | 317,866.3 | 64,666.3 |

| 14:15 | 24,020 | 7580 | 35,020 | 34,280 | 27,940 | 33,790 | 33,160 | 41,925.0 | 85,608.1 | 323,323.1 | 70,123.1 |

| 14:30 | 24,540 | 8130 | 34,950 | 37,640 | 24,360 | 34,020 | 30,680 | 41,925.0 | 85,608.1 | 321,853.1 | 68,653.1 |

| 14:45 | 29,530 | 8010 | 35,170 | 39,080 | 24,640 | 33,980 | 34,560 | 41,925.0 | 85,608.1 | 332,503.1 | 79,303.1 |

| 15:00 | 29,920 | 10,770 | 28,590 | 35,200 | 23,370 | 33,760 | 39,000 | 41,925.0 | 45,202.6 | 287,737.6 | 34,537.6 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Price (€/MWh) | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average charge | 52.55 | 120.90 | 74.31 | 62.23 | 64.25 | 90.58 | 87.19 | 93.36 | 93.95 | 75.32 | 49.83 | 59.16 |

| Average discharge | 90.15 | 145.23 | 104.84 | 87.00 | 84.57 | 100.13 | 96.65 | 100.56 | 112.54 | 100.58 | 73.16 | 82.48 |

| Average price | 69.35 | 134.23 | 89.92 | 76.96 | 76.09 | 95.59 | 93.80 | 97.86 | 104.15 | 89.77 | 63.26 | 72.20 |

| Difference | 37.60 | 24.34 | 30.53 | 24.77 | 20.05 | 9.55 | 9.46 | 7.20 | 18.60 | 25.26 | 23.32 | 23.32 |

| Profit per discharge | 81.14 | 130.71 | 94.36 | 78.30 | 76.11 | 90.12 | 86.98 | 90.50 | 101.29 | 90.52 | 65.84 | 74.23 |

| Feasibility of price arbitrage | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Price (€/MWh) | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average charge | 48.78 | 117.81 | 71.57 | 60.70 | 62.50 | 87.98 | 90.30 | 91.75 | 91.64 | 73.28 | 51.09 | 60.07 |

| Average discharge | 93.54 | 151.96 | 105.85 | 94.08 | 90.31 | 101.52 | 99.87 | 102.96 | 120.96 | 109.27 | 77.27 | 83.14 |

| Average price | 66.35 | 134.23 | 89.96 | 76.96 | 76.09 | 96.59 | 93.80 | 97.86 | 104.15 | 89.85 | 63.26 | 72.20 |

| Difference | 43.76 | 34.15 | 34.28 | 33.37 | 27.81 | 13.54 | 9.58 | 10.72 | 29.31 | 35.99 | 26.17 | 23.07 |

| Profit per discharge | 84.19 | 136.76 | 95.27 | 84.67 | 81.28 | 91.37 | 89.89 | 92.23 | 108.86 | 93.34 | 69.54 | 74.82 |

| Feasibility of price arbitrage | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Battery Autonomy | Average Monthly Profit per Discharge (€/MWh) | Curtailment/Price Arbitrage Profits (€) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 66.04136 | 49,123 |

| 2 h | 84.77681 | 61,731 |

| +5% Plant Production (€) | +5% Battery Efficiency (€) | +5% Curtailment (−5% Exportation Limit) (€) |

|---|---|---|

| 75,527 | 84,838 | 70,962 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Felgueiras, C.; Magalhães, A.; Xavier, C.; Pereira, F.; Silva, A.F.d.; Caetano, N.; Martins, F.F.; Silva, P.; Machado, J.; Santos, A.A. A Hybrid Energy Storage System and the Contribution to Energy Production Costs and Affordable Backup in the Event of a Supply Interruption—Technical and Financial Analysis. Energies 2026, 19, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020306

Felgueiras C, Magalhães A, Xavier C, Pereira F, Silva AFd, Caetano N, Martins FF, Silva P, Machado J, Santos AA. A Hybrid Energy Storage System and the Contribution to Energy Production Costs and Affordable Backup in the Event of a Supply Interruption—Technical and Financial Analysis. Energies. 2026; 19(2):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020306

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelgueiras, Carlos, Alexandre Magalhães, Celso Xavier, Filipe Pereira, António Ferreira da Silva, Nídia Caetano, Florinda F. Martins, Paulo Silva, José Machado, and Adriano A. Santos. 2026. "A Hybrid Energy Storage System and the Contribution to Energy Production Costs and Affordable Backup in the Event of a Supply Interruption—Technical and Financial Analysis" Energies 19, no. 2: 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020306

APA StyleFelgueiras, C., Magalhães, A., Xavier, C., Pereira, F., Silva, A. F. d., Caetano, N., Martins, F. F., Silva, P., Machado, J., & Santos, A. A. (2026). A Hybrid Energy Storage System and the Contribution to Energy Production Costs and Affordable Backup in the Event of a Supply Interruption—Technical and Financial Analysis. Energies, 19(2), 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020306