Odor Impact of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Statistical Analysis of Annual Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

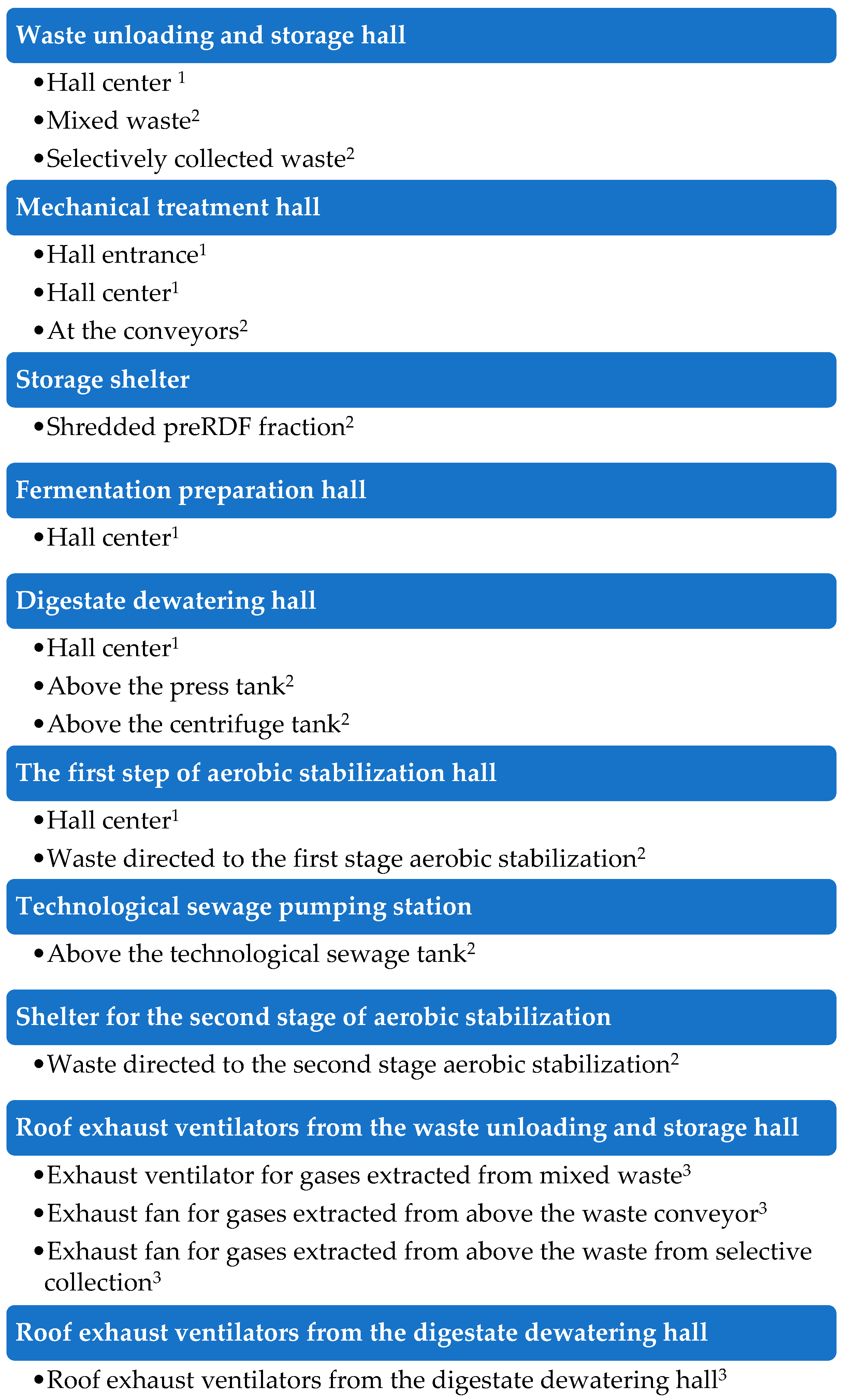

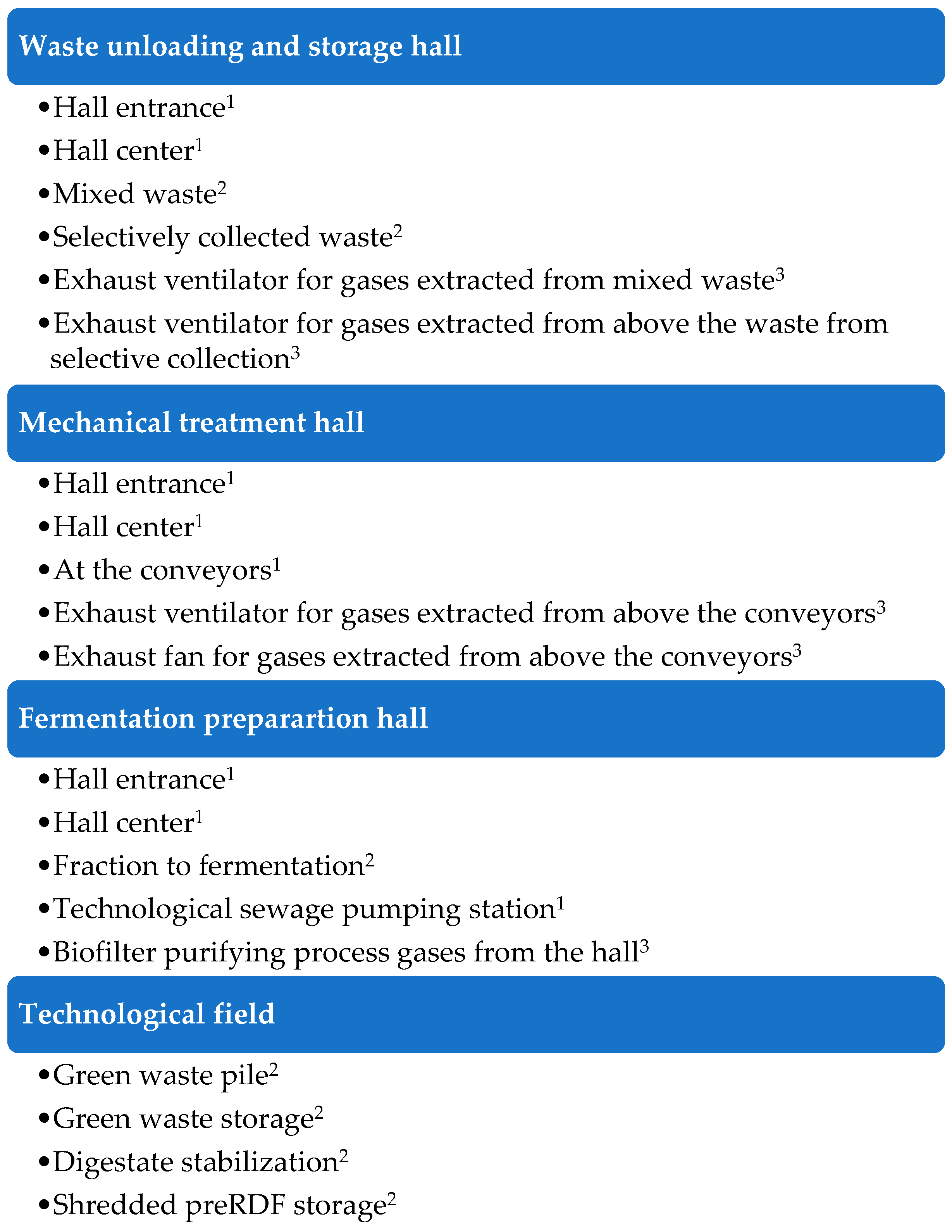

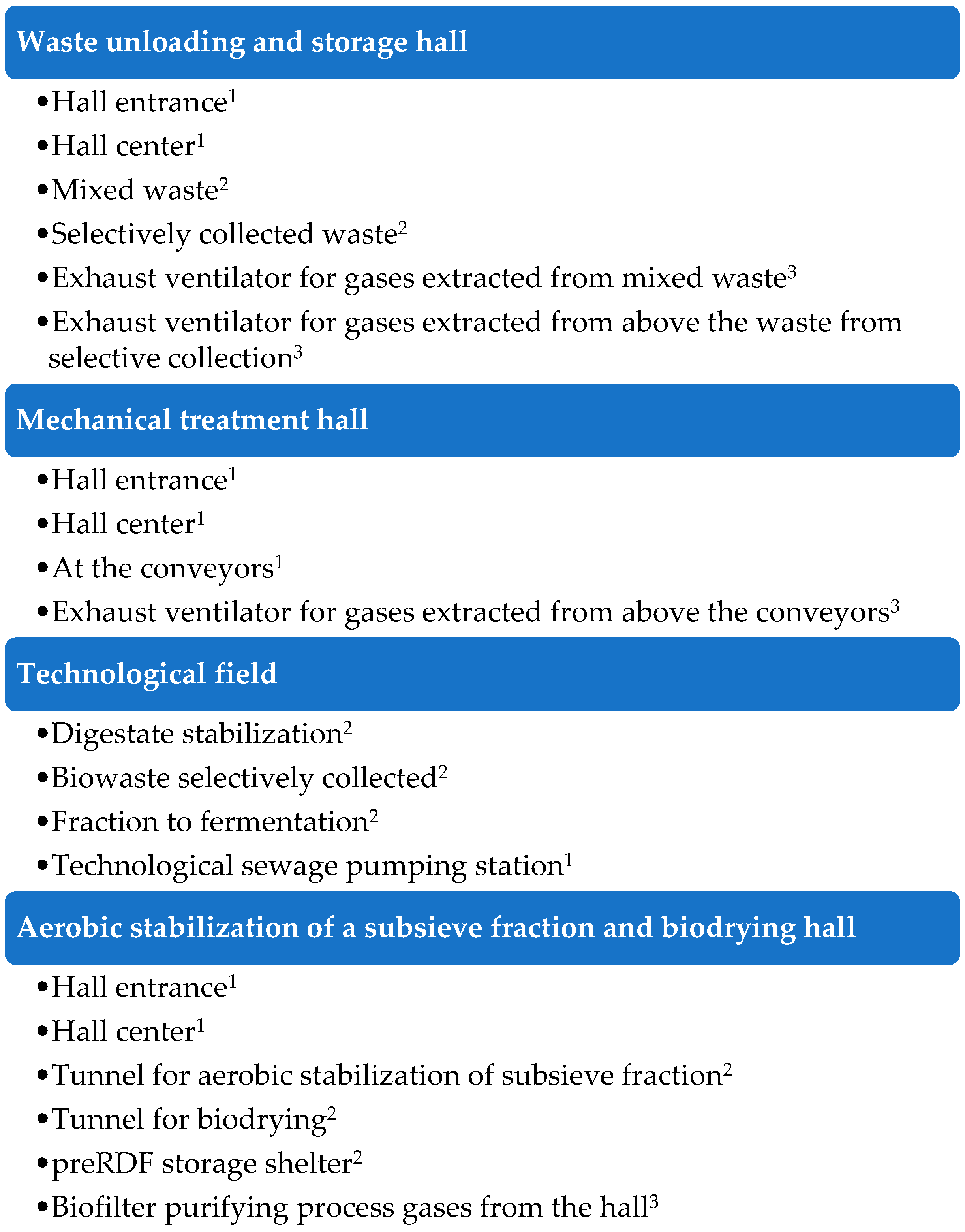

2. Materials and Methods

- Odor concentration

- ZYES means the dilution ratio (–) at which the odor was perceptible;

- ZNO means the dilution ratio (–) at which the odor was imperceptible.

- Odorant concentrations

- Microclimate parameters: T and RH of the air

- Measurement point characteristics

- Statistical analysis of the results obtained

- y—the predicted value of the dependent variable,

- β0—the y-intercept (value of y when all other parameters are set to 0),

- β1X1—the regression coefficient (β1) of the first independent variable (X1) (the effect that increasing the value of the independent variable has on the predicted y value),

- βnXn—the regression coefficient of the last independent variable,

- ε—model error (how much variation there is in our estimate of y).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlation Analysis and PCA with Multivariate Regression

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic Digestion |

| BAT | Best Available Techniques |

| cod | Odor Concentration |

| C | Odorant Concentration |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| MWBP | Municipal Waste Biogas Plant |

| OAV | Odor Activity Value |

| ODT | Odor Detection Threshold |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PID | Photoionization Detector |

References

- Kanani, M.J.B. Step toward sustainable development through the integration of renewable energy systems with, fuel cells: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 70, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.P.; Camiloti, P.R.; Sauer, I.L.; Mady, C.E.K. Exergy Analysis of a Biogas Plant for Municipal Solid Waste Treatment and Energy Cogeneration. Energies 2025, 18, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Montgomery, P. A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Changes for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malav, L.C.; Yadav, K.K.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, G.K.; Krishnan, S.; Rezania, S.; Kamyab, H.; Pham, Q.B.; Yadav, S.; et al. A review on municipal solid waste as a renewable source for waste-to-energy project in India: Current practices, challenges, and future opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckebosch, E.; Drouillon, M.; Vervaeren, H. Techniques for transformation of biogas to biomethane. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bioenergy Association. Global Bioenergy Statisticks; WBA: Stockholms, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grando, R.L.; de Souza Antune, M.A.; da Fonseca, F.V.; Sánchez, A.; Barrena, R.; Font, X. Technology overview of biogas production in anaerobic digestion plants: A European evaluation of research and development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruga, P.; Krzywonos, M.; Wilk, M. Treatment of By-Products Generated from Anaerobic Digestion of Municipal Solid Waste. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 4933–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ibrahimi, M.; Khay, I.; El Maakoul, A.; Bakhouya, M. Techno-economic and environmental assessment of anaerobic co-digestion plants under different energy scenarios: A case study in Morocco. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.H. Technical-economical analysis of anaerobic digestion process to produce clean energy. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-E.; Loveridge, S.; Joshi, S. Local acceptance and heterogeneous externalities of biorefineries. Energy Econ. 2017, 67, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Smith, W.W.; McEwen, W.R. Not in My Backyard: Personal Politics and Resident Attitudes toward Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soland, M.; Steimer, N.; Walter, G. Local acceptance of existing biogas plants in Switzerland. Energy Pol. 2013, 61, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.M.; Le-Minh, N.; Alvarez-Gaitan, J.P.; Moore, S.J.; Stuetz, R.M. Emissions of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) throughout wastewater biosolids processing. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 622–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sówka, I.; Pawnuk, M.; Grzelka, A.; Pielichowska, A. The use of ordinary kriging and inverse distance weighted interpolation to assess the odour impact of a poultry farming plant. Sci. Rev. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2020, 29, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzi, V.; Riva, C.; Scaglia, B.; D’Imporzano, G.; Tambone, F.; Adani, F. Anaerobic digestion coupled with digestate injection reduced odour emissions from soil during manure distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighravwe, D.E.; Babatunde, D.E. Evaluation of landfill gas plant siting problem: A multi-criteria approach. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, M.; Kulig, A.; Lelicińska-Serafin, K. Odour Nuisance at Municipal Waste Biogas Plants and the Effect of Feedstock Modification on the Circular Economy—A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.; Stevenson, R.; Stuetz, R. The impact of malodour on communities: A review of assessment techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 500, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kośmider, J.; Mazur-Chrzanowska, B.; Wyszyński, B. Odours [Odory]; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Piringer, M.; Schauberger, G. Dispersion Modelling for Odour Exposure Assessment. In Odour Impact Assessment Handbook; Belgiorno, V., Naddeo, V., Zarra, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2013; pp. 125–174. [Google Scholar]

- Naddeo, V.; Belgiorno, V.; Zarra, T. Odour Characterization and Exposure Effects. In Odour Impact Assessment Handbook; Belgiorno, V., Naddeo, V., Zarra, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13725: 2003; Air Quality-Determination of Odour Concentration by Dynamic Olfactometry. European Committee for Standardization, CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- Sarkar, U.; Hobbs, S.E. Odour from municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills: A study on the analysis of perception. Environ. Int. 2002, 27, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewska, M.; Kulig, A.; Lelicińska-Serafin, K. Olfactometric testing as a method for assessing odour nuisance of biogas plants processing municipal waste. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2020, 46, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, E.; Lim, M.H.; Zhang, L.; Sedlak, D.L. Odorous compounds in municipal wastewater effluent and potable water reuse systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9347–9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.D.; Jeon, S.B.; Choi, W.J.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, M.H.; Oh, K.J. A novel assessment of odor sources using instrumental analysis combined with resident monitoring records for an industrial area in Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 74, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.B.; Gilley, J.; Woodbury, B.; Kim, K.H.; Galvin, G.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.L.; Li, X.; Snow, D.D. Odorous VOC emission following land application of swine manure slurry. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 66, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabue, S.; Scoggin, K.; McConnell, L.; Maghirang, R.; Razote, E.; Hatfield, J. Identifying and tracking key odorants from cattle feedlots. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 4243–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Yan, L.; Chen, H.; Shao, H.; Meng, T. Assessment of odor activity value coefficient and odor contribution based on binary interaction effects in waste disposal plant. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 103, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielberg, A.; Liu, D.; Adamsen, A.P.S.; Hansen, M.J.; Jonassen, K.E.N. Odorant Emissions from Intensive Pig Production Measured by Online Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5894–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gębicki, J.; Szulczyński, B.; Byliński, H.; Kolasińska, P.; Dymerski, T.; Namieśnik, J. Application of Electronic Nose to Ambient Air Quality Evaluation With Respect to Odour Nuisance in Vicinity of Municipal Landfills and Sewage Treatment. In Electronic Nose Technologies and Advances in Machine Olfaction; Albastaki, Y., Albalooshi Bahrajn, F., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, L.; Sironi, S.; Del Rosso, R.; Céntola, P.; Il Grande, M. A comparative and critical evaluation of odour assessment methods on a landfill site. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 7050–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Amano, S.; Merecka, B.; Kośmider, J. Difference in the odor concentrations measured by the triangle odor bag method and dynamic olfactometry. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, M. Methods of Assessing Odour Emissions from Biogas Plants Processing Municipal Waste. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanes-Vidal, V.; Hansen, M.N.; Adamsen, A.P.S.; Feilberg, A.; Petersen, S.O.; Jensen, B.B. Characterization of odor released during handling of swine slurry: Part I. Relationship between odorants and perceived odor concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 2997–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazy, V.; de Guardia, A.; Benoist, J.C.; Daumoin, M.; Lemasle, M.; Wolbert, D.; Barrington, S. Odorous gaseous emissions as influence by process condition for the forced aeration composting of pig slaughterhouse sludge. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, C.A.; De Guardia, A.; Couvert, A.; Le Roux, S.; Soutrel, I.; Daumoin, M.; Benoist, J.C. Chemical and odor characterization of gas emissions released during composting of solid wastes and digestates. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; Chen, M.L.; Ye, A.D.; Chou, M.S.; Shen, S.H.; Mao, I.F. The relationship of odor concentration and the critical components emitted from food waste composting plants. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 8246–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.; Guariano, M.; Bacenetti, J. Measurements techniques and models to assess odor annoyance: A review. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewska, M.; Kulig, A.; Lelicińska-Serafin, K. Odour Emissions of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Impact of Technological Factors, Air Temperature and Humidity. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union (EU). Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/1147 of 10 August 2018 establishing Best Available Techniques (BAT) Conclusions for Waste Treatment, Under Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council; Publications Office of the European Union (OP): Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nasal Ranger—Field Olfactometer. Available online: https://www.fivesenses.com/equipment/nasalranger/nasalranger/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ISO 4120:2004; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Triangle Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Sadegh, N.; Uniacke, J.; Feilberg, A.; Kofoed, M.V.W. Assessment of transient hydrogen sulfide peak emissions caused by biogas plant operation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 142920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serie | Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Biogas Plant A | Biogas Plant B | Biogas Plant C | |

| 1 | 11 July 2019 | 18 July 2019 | 5 July 2019 |

| 2 | 25 July 2019 | 1 August 2019 | 18 July 2019 |

| 3 | 8 August 2019 | 12 August 2019 | 1 August 2019 |

| 4 | 22 August 2019 | 23 August 2019 | 12 August 2019 |

| 5 | 5 September 2019 | 11 September 2019 | 23 August 2019 |

| 6 | 3 October 2019 | 10 October 2019 | 19 September 2019 |

| 7 | 17 October 2019 | 14 November 2019 | 10 October 2019 |

| 8 | 7 November 2019 | 25 November 2019 | 14 November 2019 |

| 9 | 21 November 2019 | 16 December 2019 | 25 November 2019 |

| 10 | 30 December 2019 | 16 January 2020 | 16 December 2020 |

| 11 | 30 January 2020 | 6 February 2020 | 16 January 2020 |

| 12 | 12 February 2020 | 10 February 2020 | 6 February 2020 |

| 13 | 27 May 2020 | 11 March 2020 | 11 March 2020 |

| 14 | 17 June 2020 | 3 June 2020 | 3 June 2020 |

| 15 | 17 December 2020 | 24 June 2020 | 24 June 2020 |

| Parameter | Biogas Plant A | Biogas Plant B | Biogas Plant C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biogas installation treatment capacity | apr. 30,000 Mg/a | apr. 20,000 Mg/a | |

| Type of methane fermentation | dynamic mesophilic | dynamic mesophilic | static mesophilic |

| Kind of feedstock for fermentation process | biodegradable waste mechanically separated from the stream of mixed municipal waste | municipal biowaste collected selectively | |

| Deodorization methods | chemical scrubber, photocatalytic oxidation, and oxybiofilter | chemical scrubber, biofilter | water scrubber and biofilter |

| No. | Parameter | Unit | Source Type | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH3SH | ppm | cubic source | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 2 | CH3SH | ppm | surface source | 0.65 | 2.68 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 3 | CH3SH | ppm | organized source | 0.63 | 2.25 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 4 | H2S | ppm | cubic source | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | H2S | ppm | surface source | 0.45 | 1.85 | 0 | 12.4 | 0 |

| 6 | H2S | ppm | organized source | 0.38 | 1.65 | 0 | 11.12 | 0 |

| 7 | NH3 | ppm | cubic source | 1.77 | 1.61 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| 8 | NH3 | ppm | surface source | 15.56 | 27.44 | 0 | 100 | 3 |

| 9 | NH3 | ppm | organized source | 9.05 | 22.66 | 0 | 100 | 2 |

| 10 | VOC | ppm | cubic source | 1.31 | 1.32 | 0 | 5.36 | 0.78 |

| 11 | VOC | ppm | surface source | 3.60 | 3.94 | 0.1 | 19.42 | 2.16 |

| 12 | VOC | ppm | organized source | 2.20 | 1.79 | 0.19 | 8.28 | 1.9 |

| 13 | cod | ou/m3 | cubic source | 14.14 | 17.90 | 2 | 105 | 6 |

| 14 | cod | ou/m3 | surface source | 145.78 | 208 | 4 | 649 | 38 |

| 15 | cod | ou/m3 | organized source | 81.28 | 176.11 | 4 | 649 | 16 |

| No. | Parameter | Unit | Point Type | The Highest Average Value | The Lowest Average Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH3SH | ppm | emission points | Biogas Plant A (1.75 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (0.001 ppm) |

| 2 | CH3SH | ppm | cubature points | Biogas Plant A (0.01 ppm) | Biogas Plant B (0.001 ppm) |

| 3 | CH3SH | ppm | points under cover | Biogas Plant A (1.54 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (0.031 ppm) |

| 4 | H2S | ppm | emission points | Biogas Plant A (1.62 ppm) | Biogas Plant B and C (0 ppm) |

| 5 | H2S | ppm | cubature points | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | H2S | ppm | points under cover | Biogas Plant A (1.48 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (0.012 ppm) |

| 7 | NH3 | ppm | emission points | Biogas Plant A (22.62 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (0.996 ppm) |

| 8 | NH3 | ppm | cubature points | Biogas Plant A (2.47 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (0.832 ppm) |

| 9 | NH3 | ppm | points under cover | Biogas Plant A (27.89 ppm) | Biogas Plant C (3.75 ppm) |

| 10 | VOC | ppm | emission points | Biogas Plant C (63.30 ppm) | Biogas Plant B (1.51 ppm) |

| 11 | VOC | ppm | cubature points | Biogas Plant C (65.51 ppm) | Biogas Plant B (1.29 ppm) |

| 12 | VOC | ppm | points under cover | Biogas Plant C (65.93 ppm) | Biogas Plant A (1.45 ppm) |

| 13 | cod | ou/m3 | emission points | Biogas Plant A (81.28 ou/m3) | Biogas Plant C (6.39 ou/m3) |

| 14 | cod | ou/m3 | cubature points | Biogas Plant B (19.43 ou/m3) | Biogas Plant C (5.20 ou/m3) |

| 15 | cod | ou/m3 | points under cover | Biogas Plant B (149.18 ou/m3) | Biogas Plant C (48.64 ou/m3) |

| Biogas Plant A | Biogas Plant B | Biogas Plant C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 |

| CH3SH | 0.067 | 0.610 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | −0.003 |

| H2S | 0.073 | 0.746 | 1.31 × 10−5 | 0.012 | 0 | 1.11 × 10−16 |

| NH3 | 0.994 | −0.106 | 0.995 | −0.098 | 0.999 | −0.0388 |

| VOC | 0.043 | 0.246 | 0.098 | 0.995 | 0.039 | 0.999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wiśniewska, M.; Lelicińska-Serafin, K.; Kulig, A.; Manczarski, P. Odor Impact of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Statistical Analysis of Annual Results. Energies 2026, 19, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010058

Wiśniewska M, Lelicińska-Serafin K, Kulig A, Manczarski P. Odor Impact of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Statistical Analysis of Annual Results. Energies. 2026; 19(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiśniewska, Marta, Krystyna Lelicińska-Serafin, Andrzej Kulig, and Piotr Manczarski. 2026. "Odor Impact of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Statistical Analysis of Annual Results" Energies 19, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010058

APA StyleWiśniewska, M., Lelicińska-Serafin, K., Kulig, A., & Manczarski, P. (2026). Odor Impact of Municipal Waste Biogas Plants—Statistical Analysis of Annual Results. Energies, 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010058