Three-Electrode Dynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy as an Innovative Diagnostic Tool for Advancing Redox Flow Battery Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

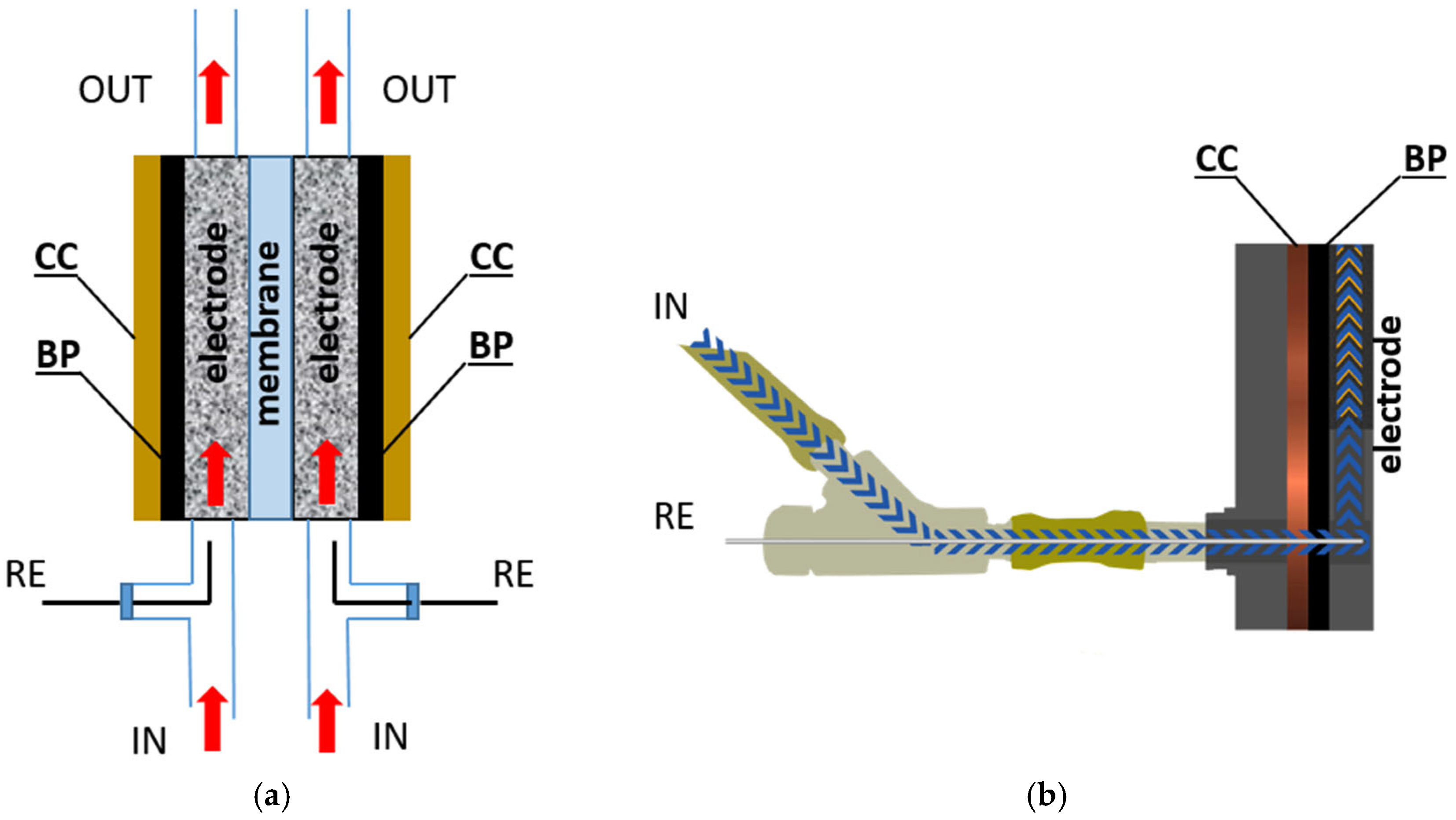

2.1. Redox Flow Battery

2.2. Accelerated Electrodes Aging

2.3. Electrochemical Study

2.4. XPS Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

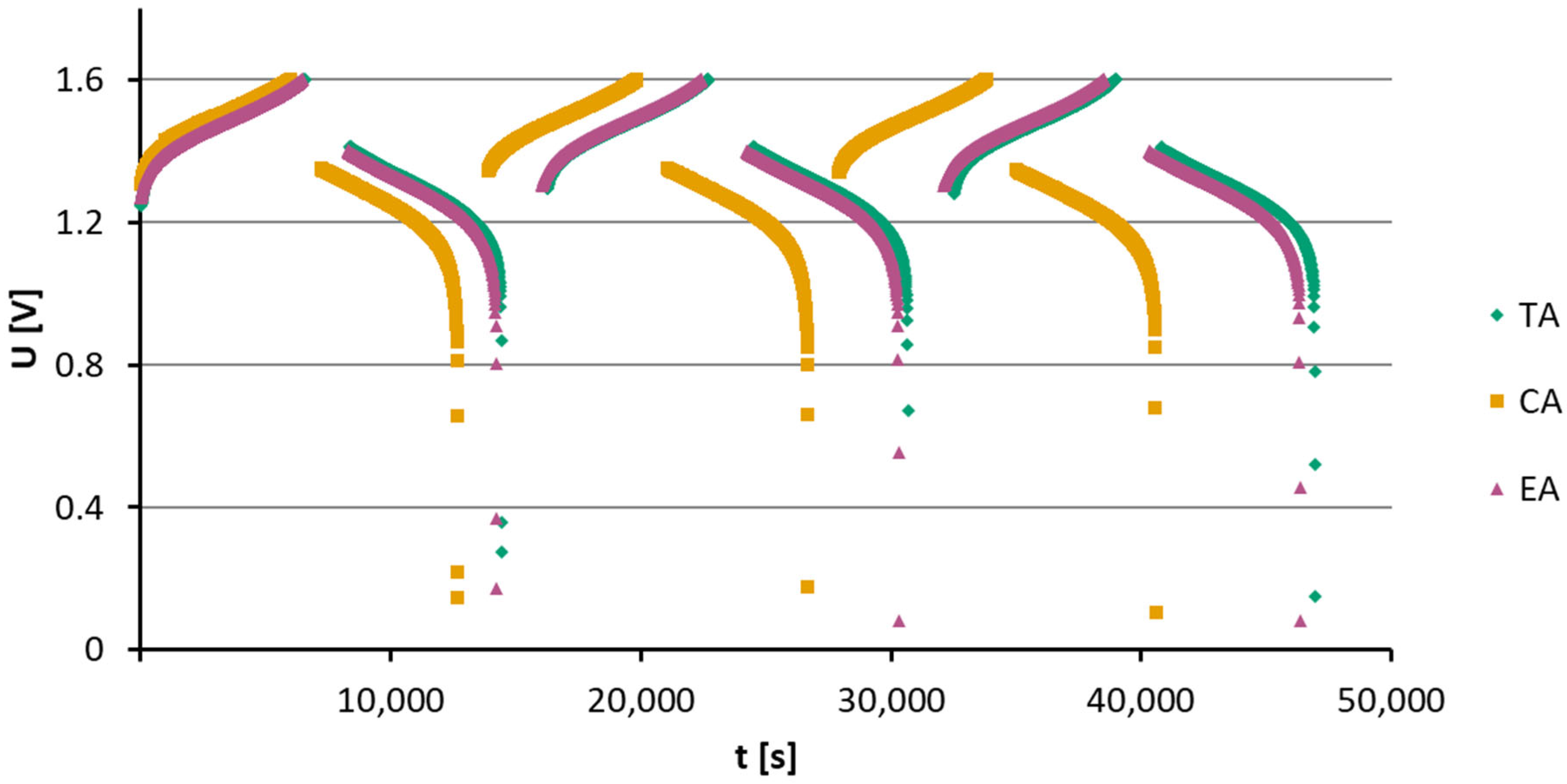

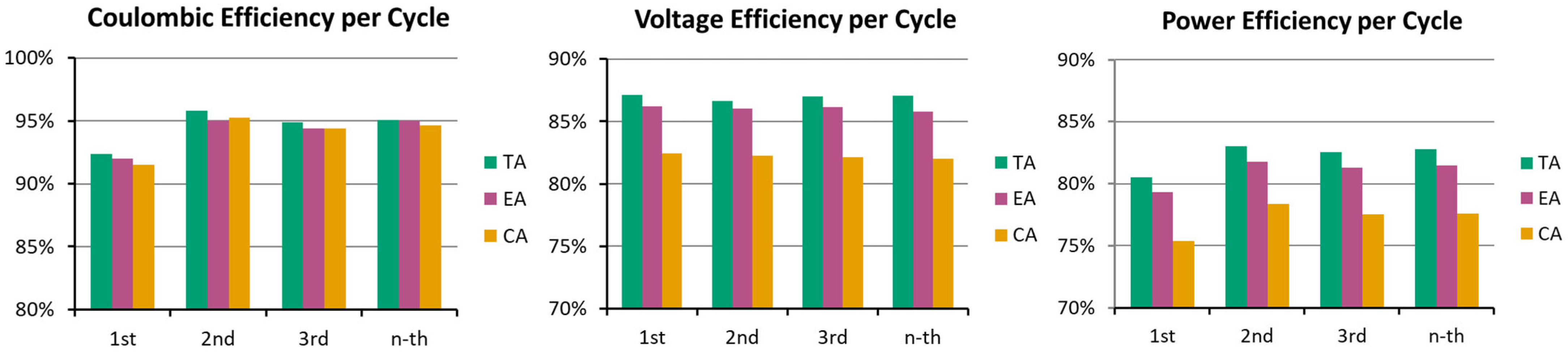

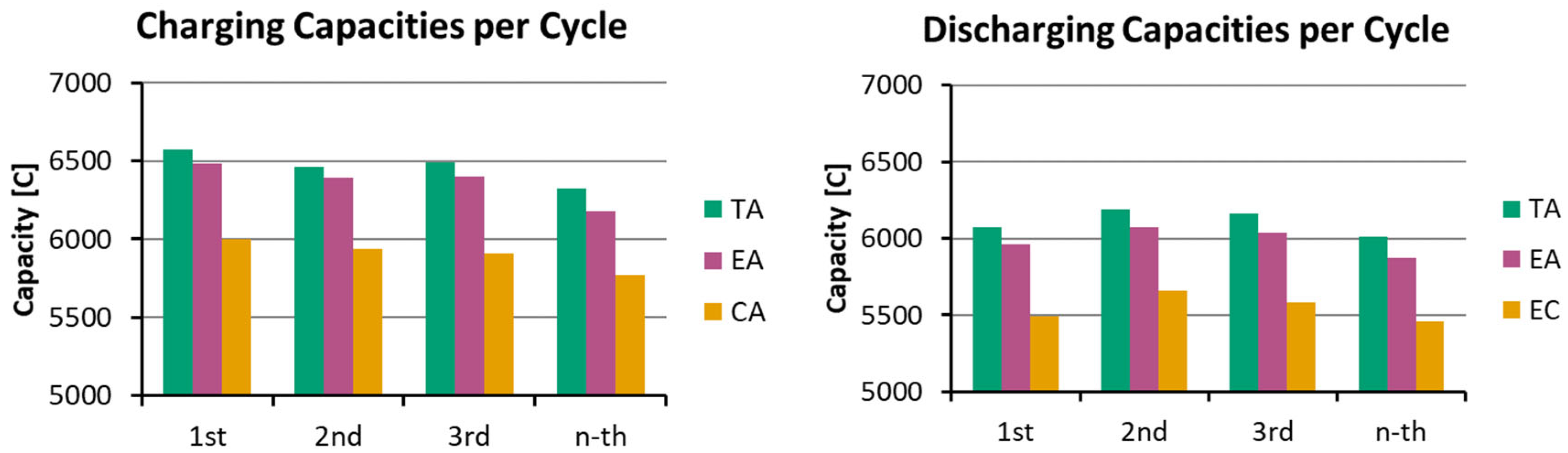

3.1. Dry Resistance and Cell Performance During Initial Cycling

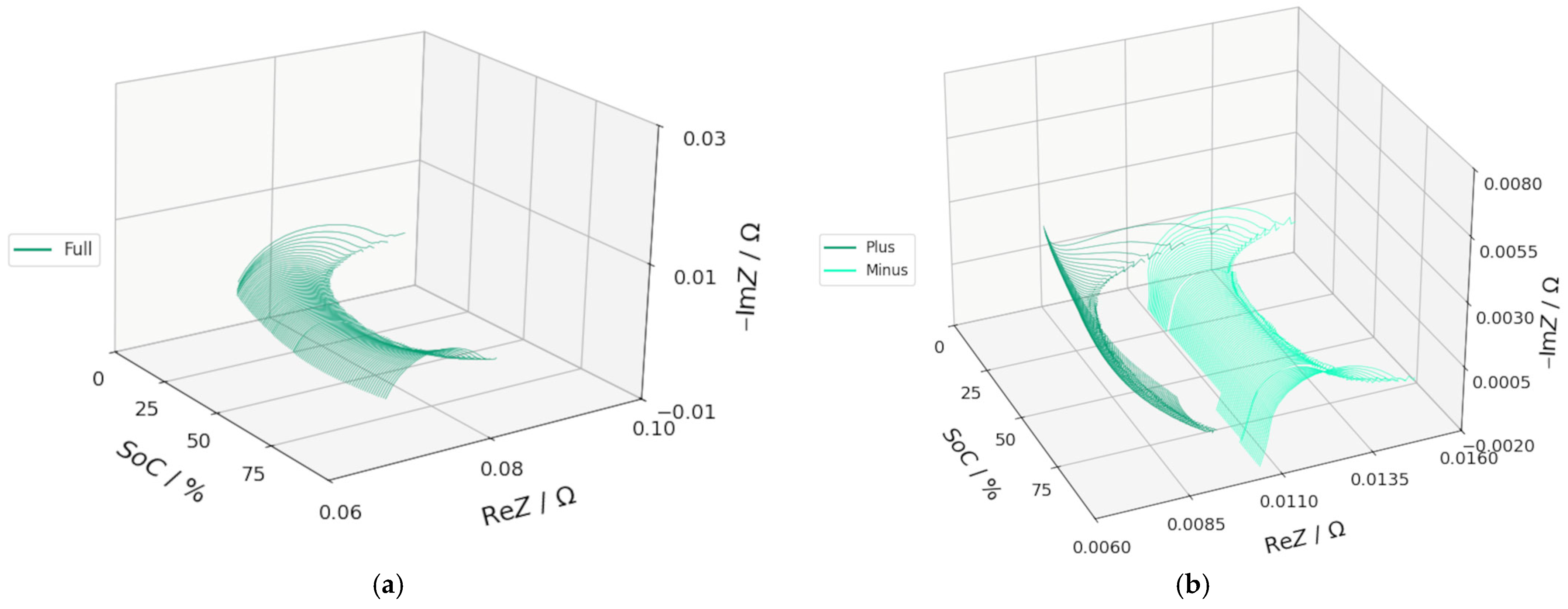

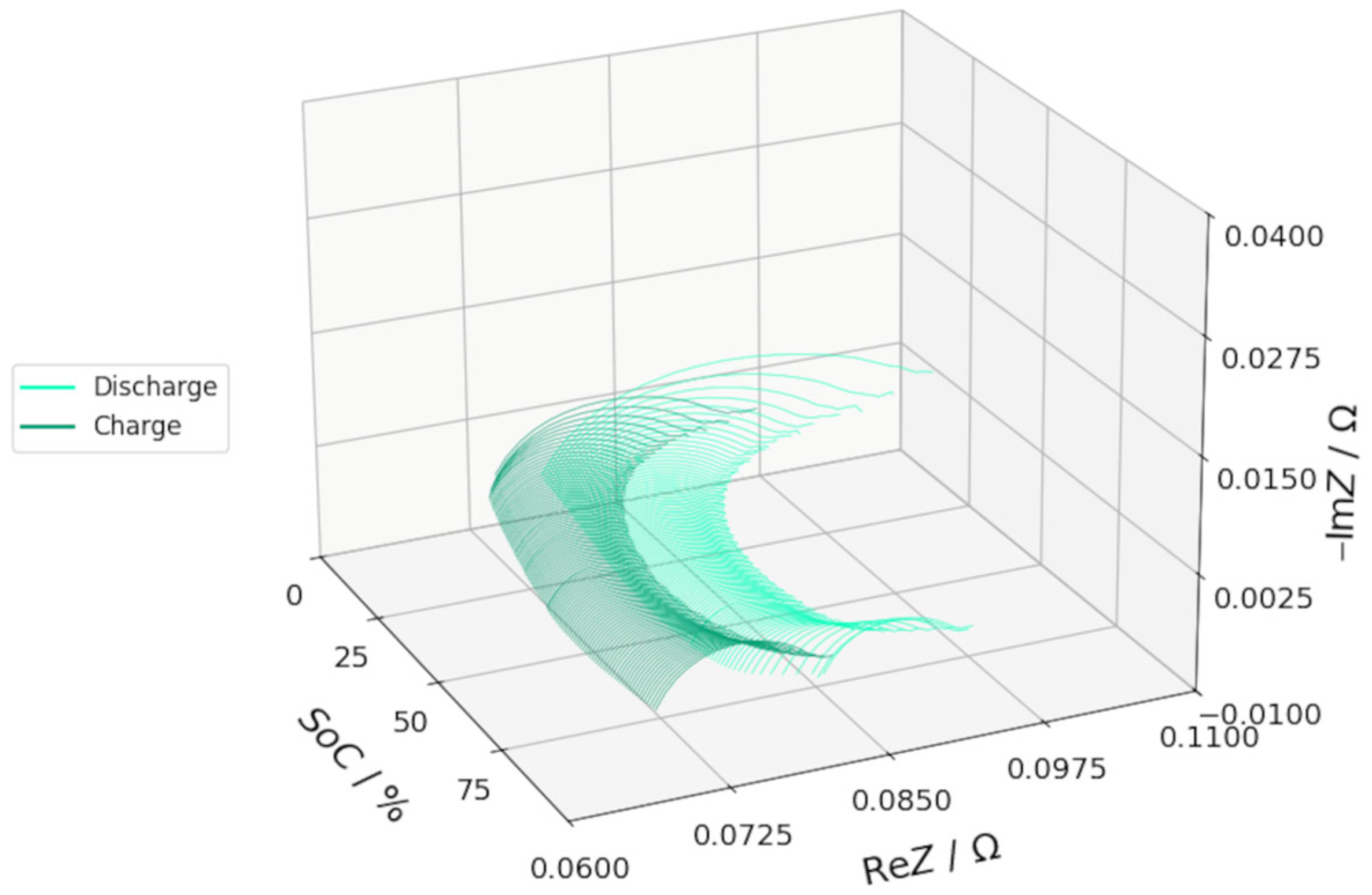

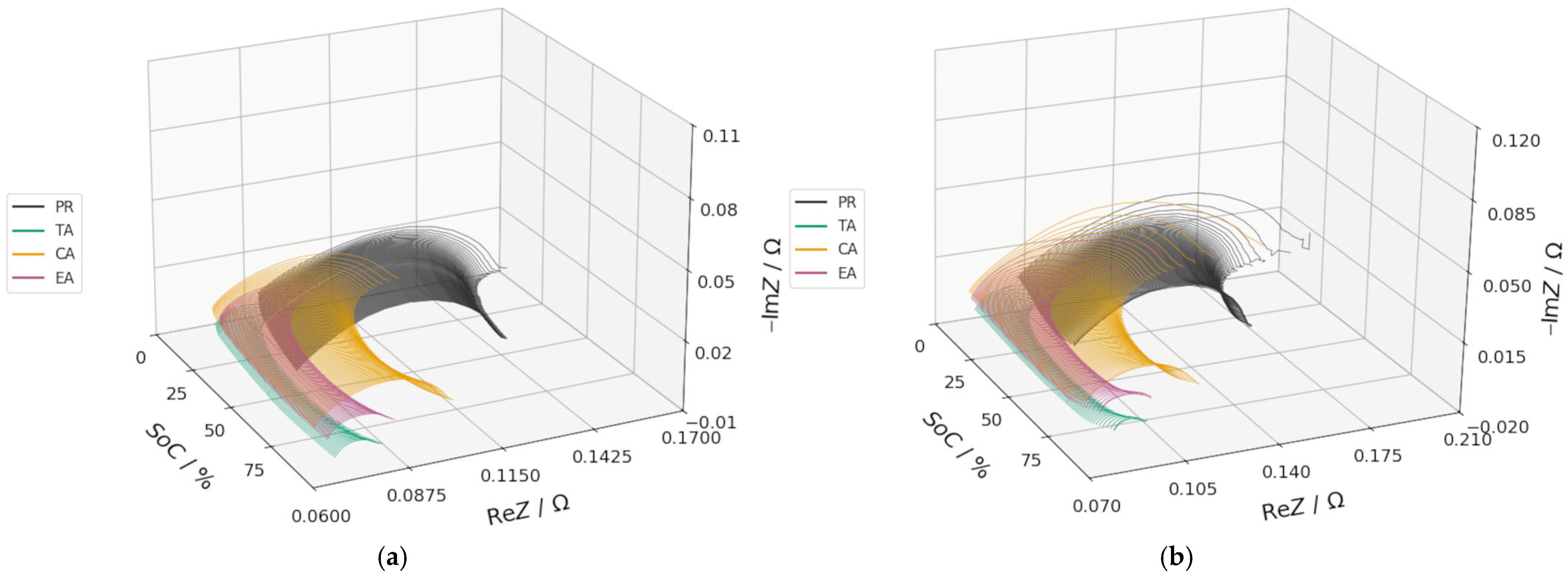

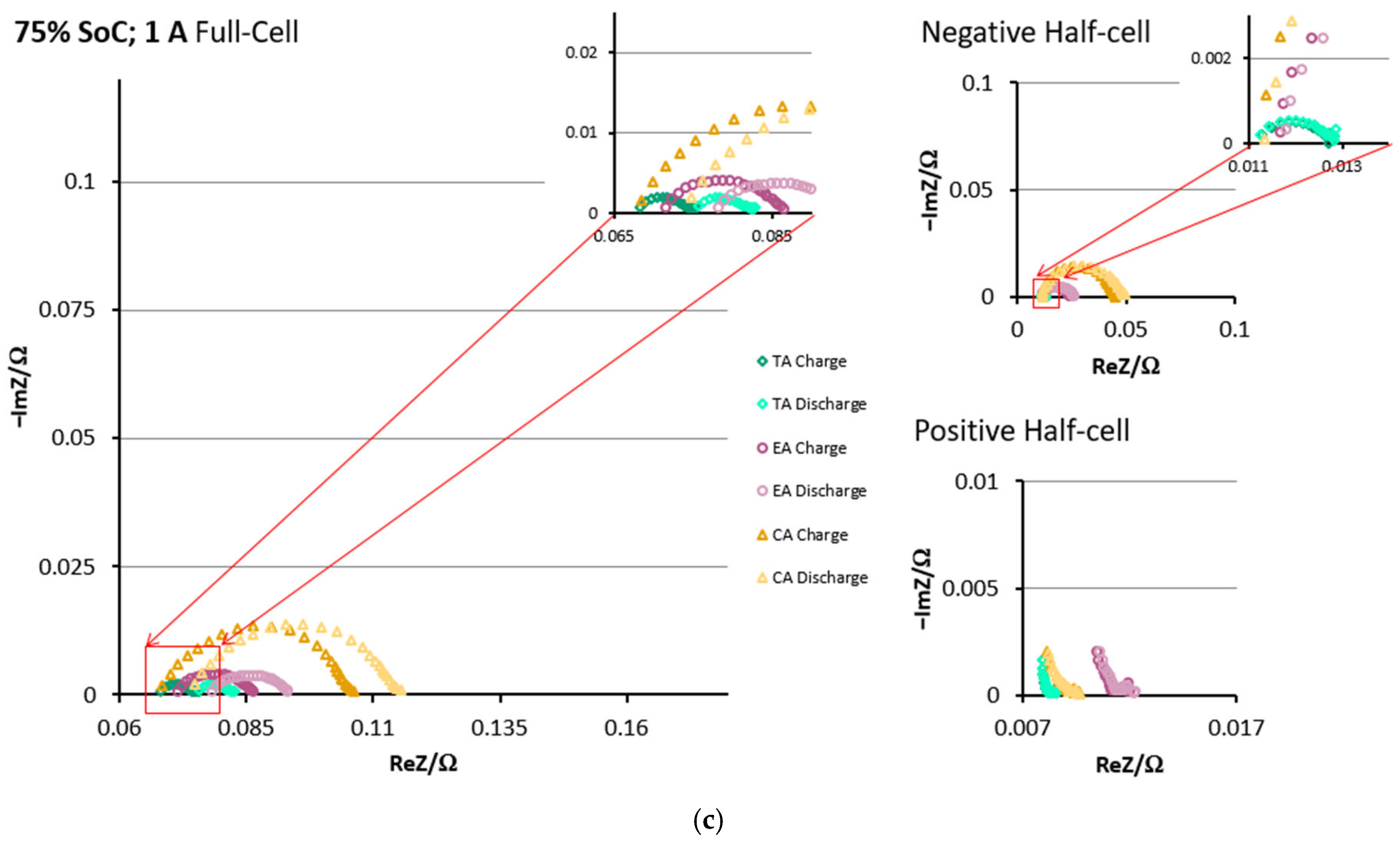

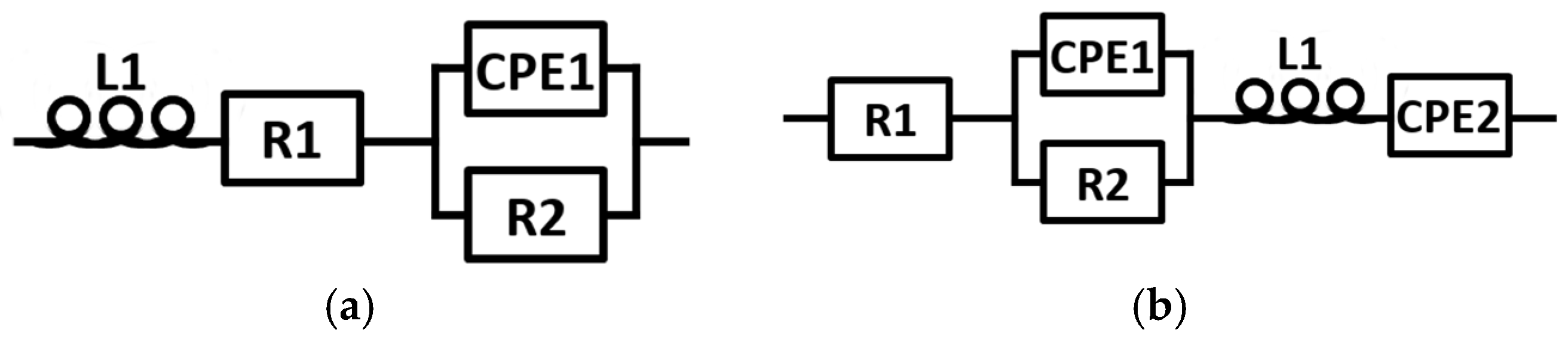

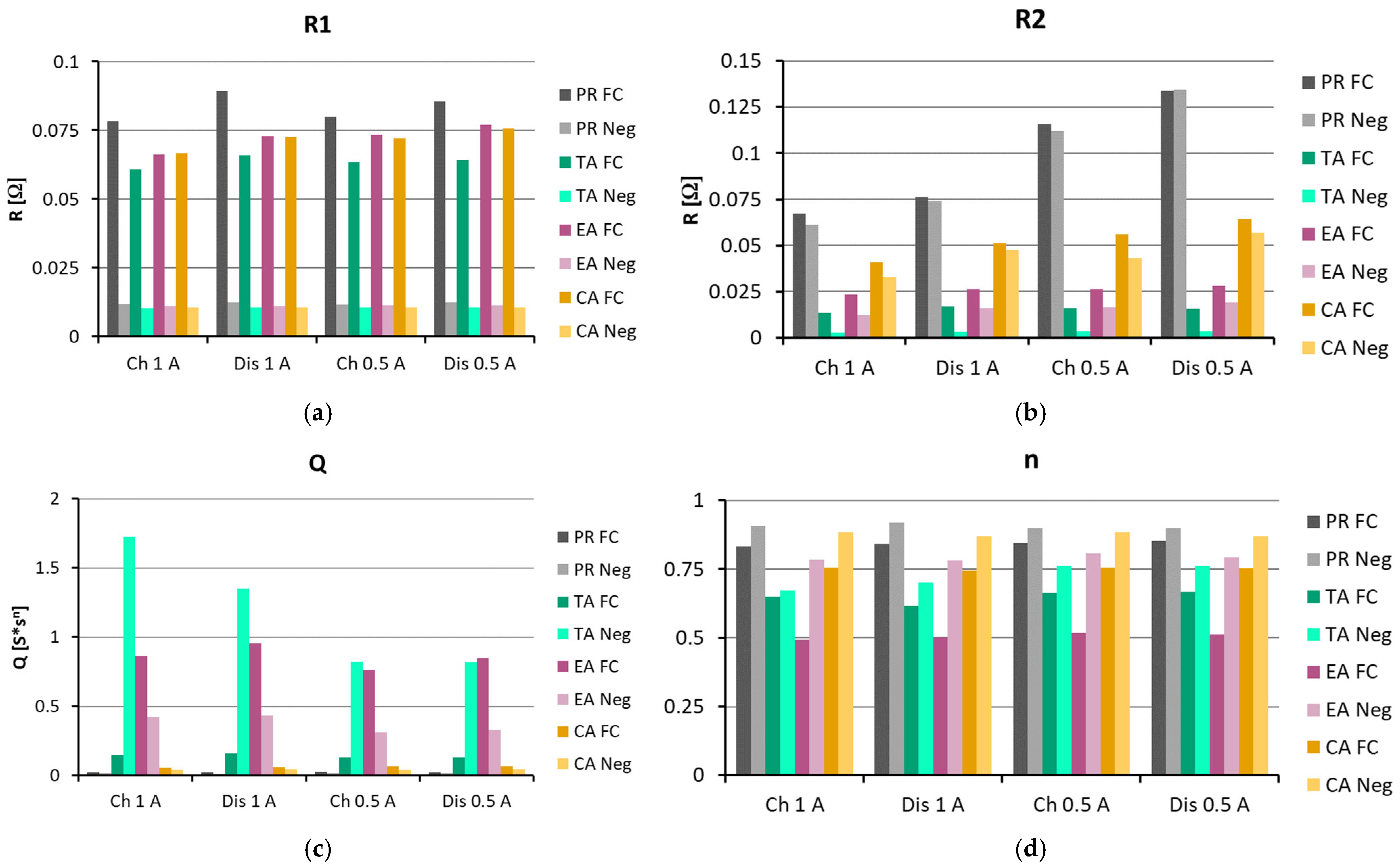

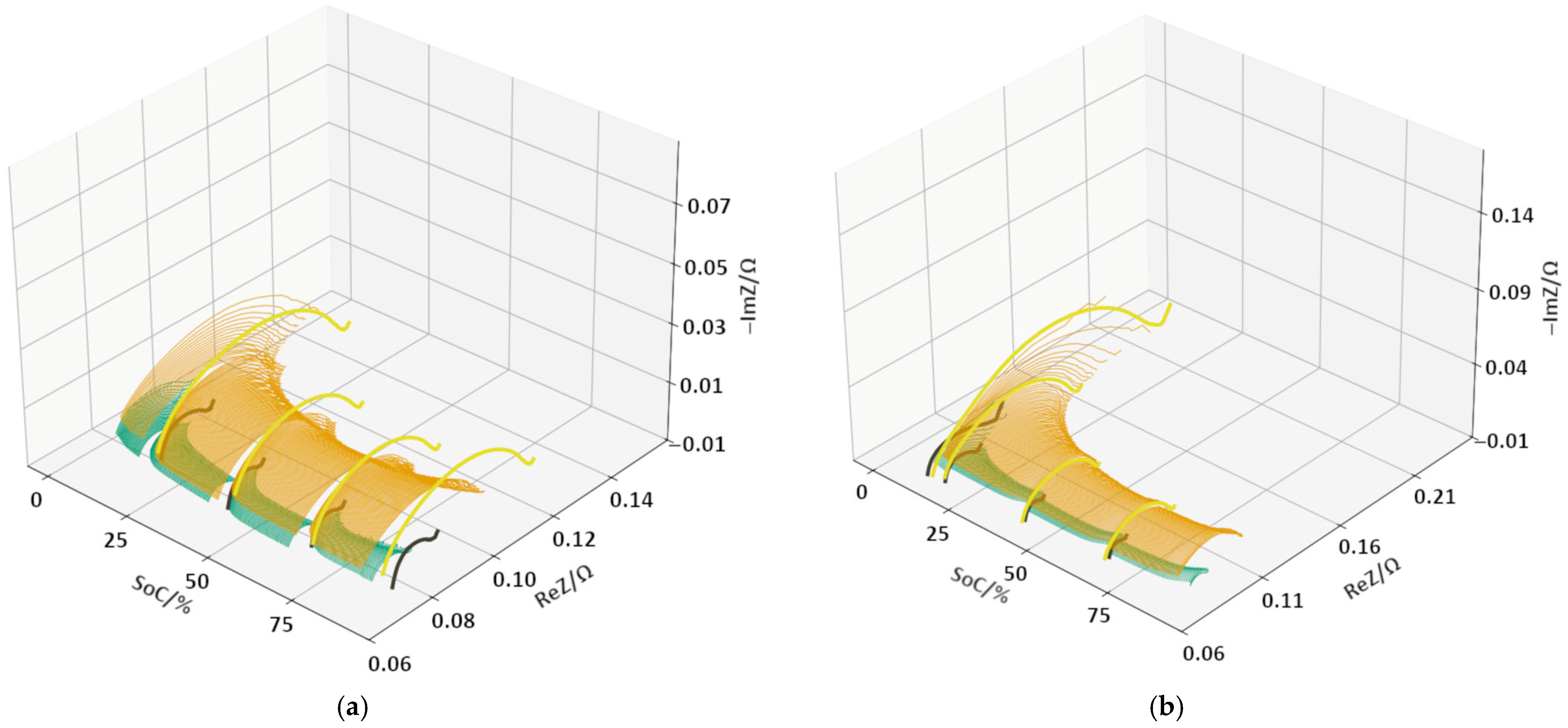

3.2. DEIS Analysis During Charging and Discharging

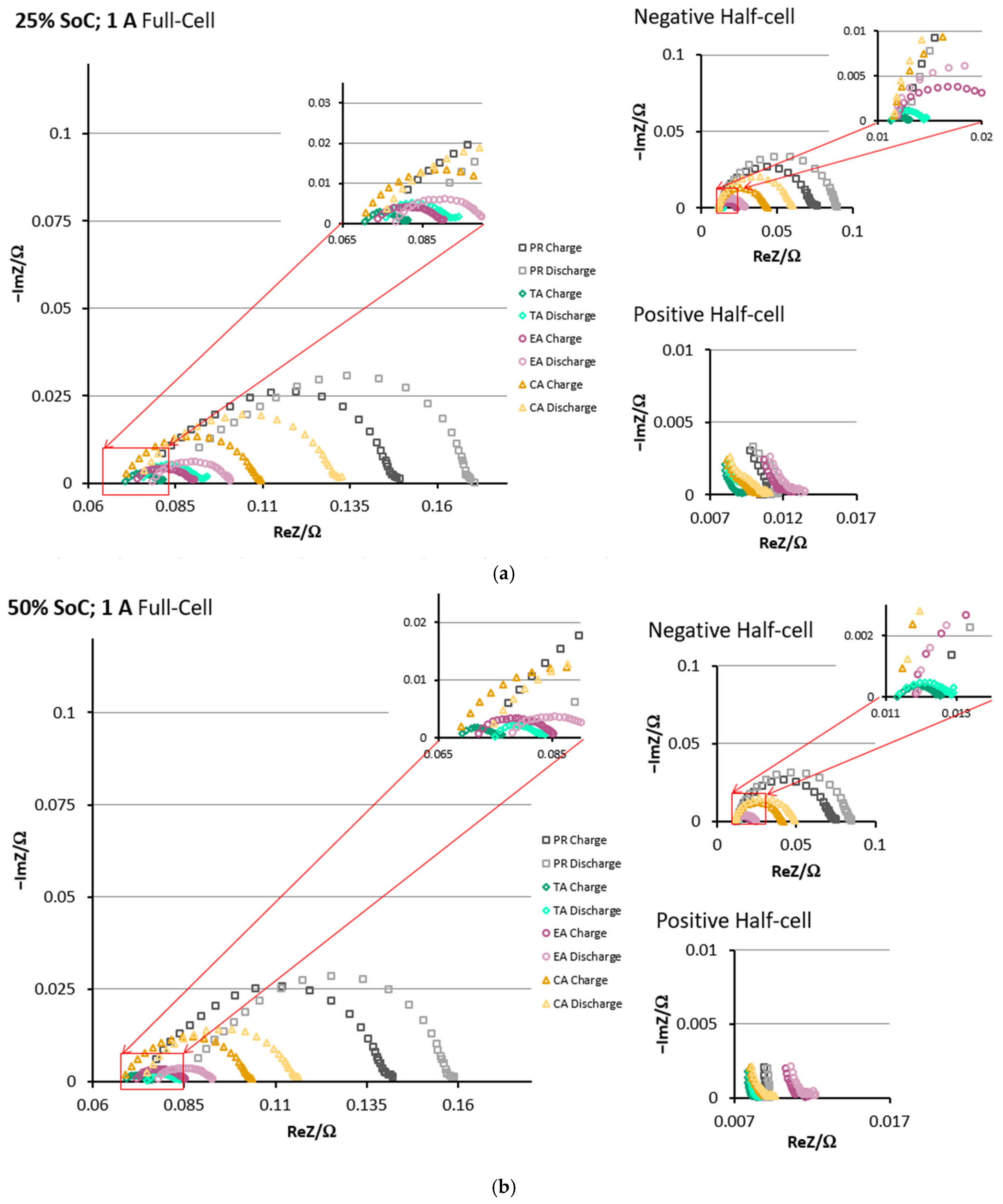

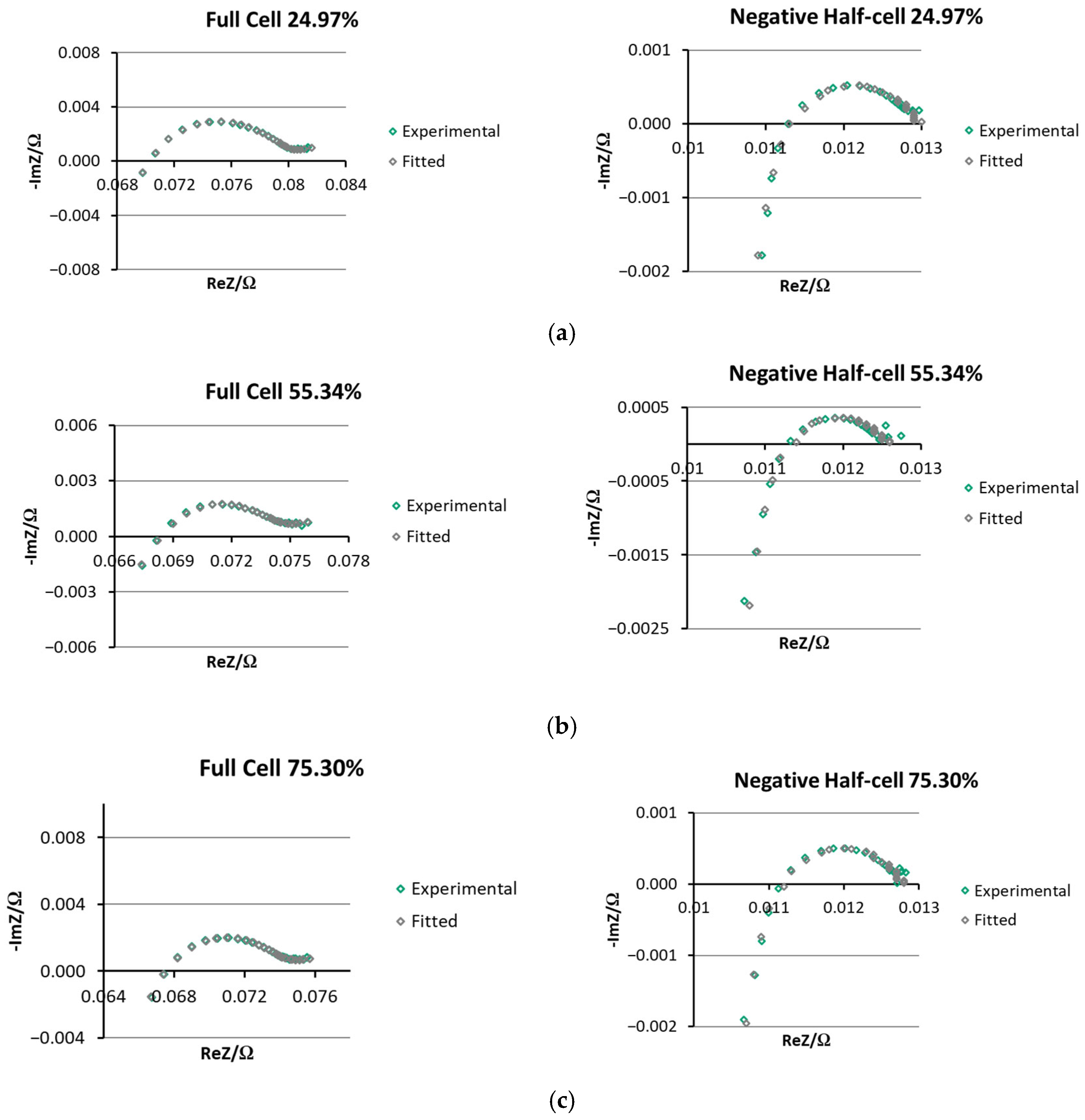

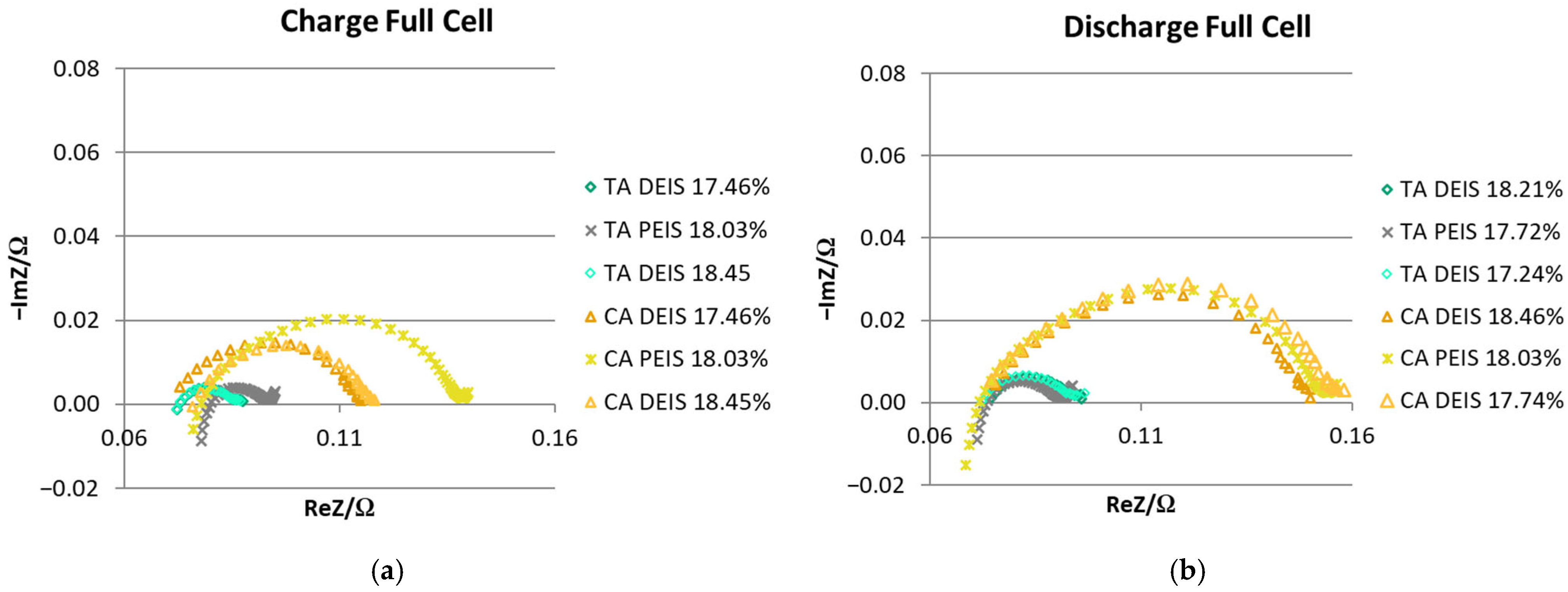

3.3. EIS Comparison

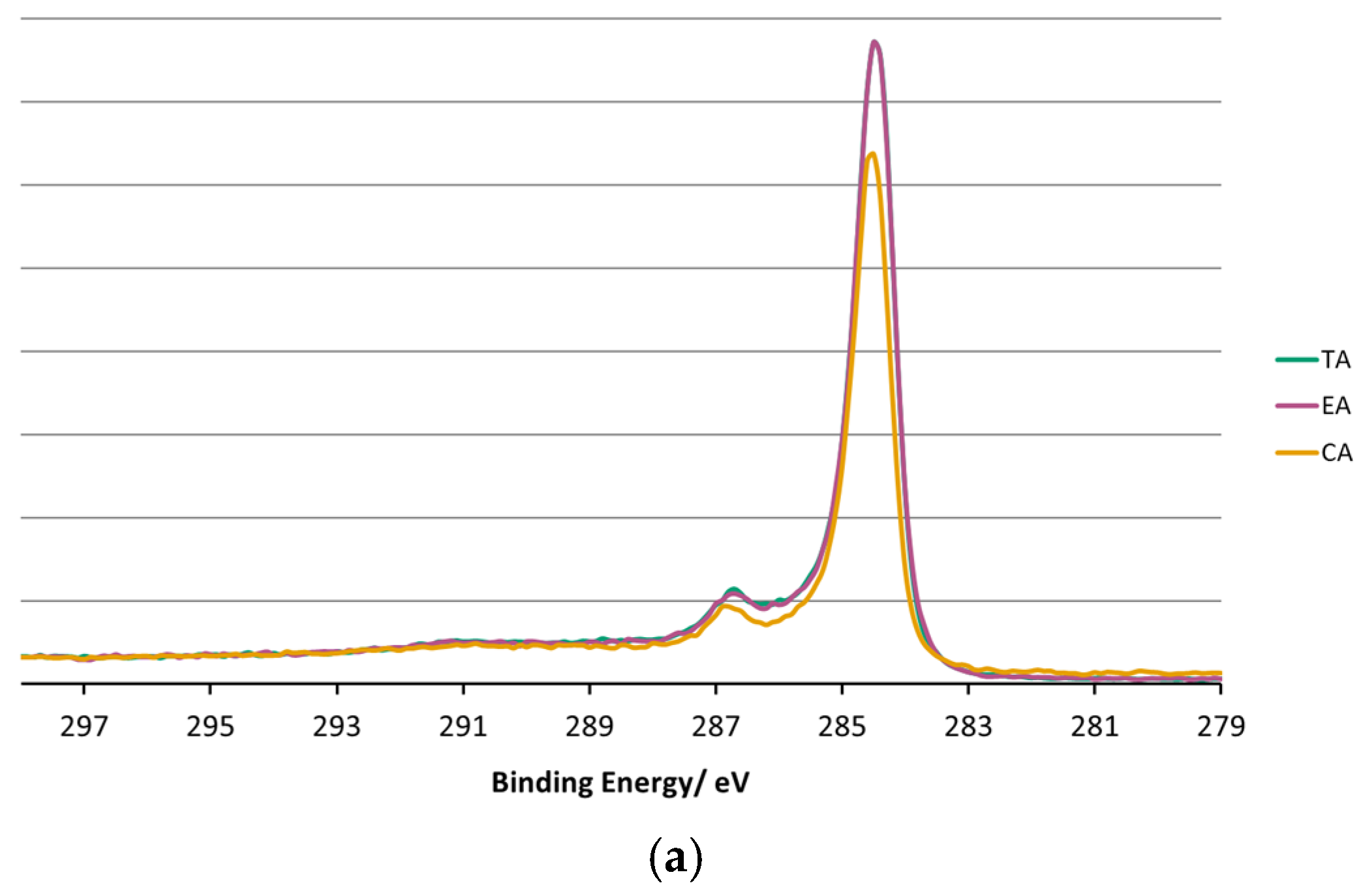

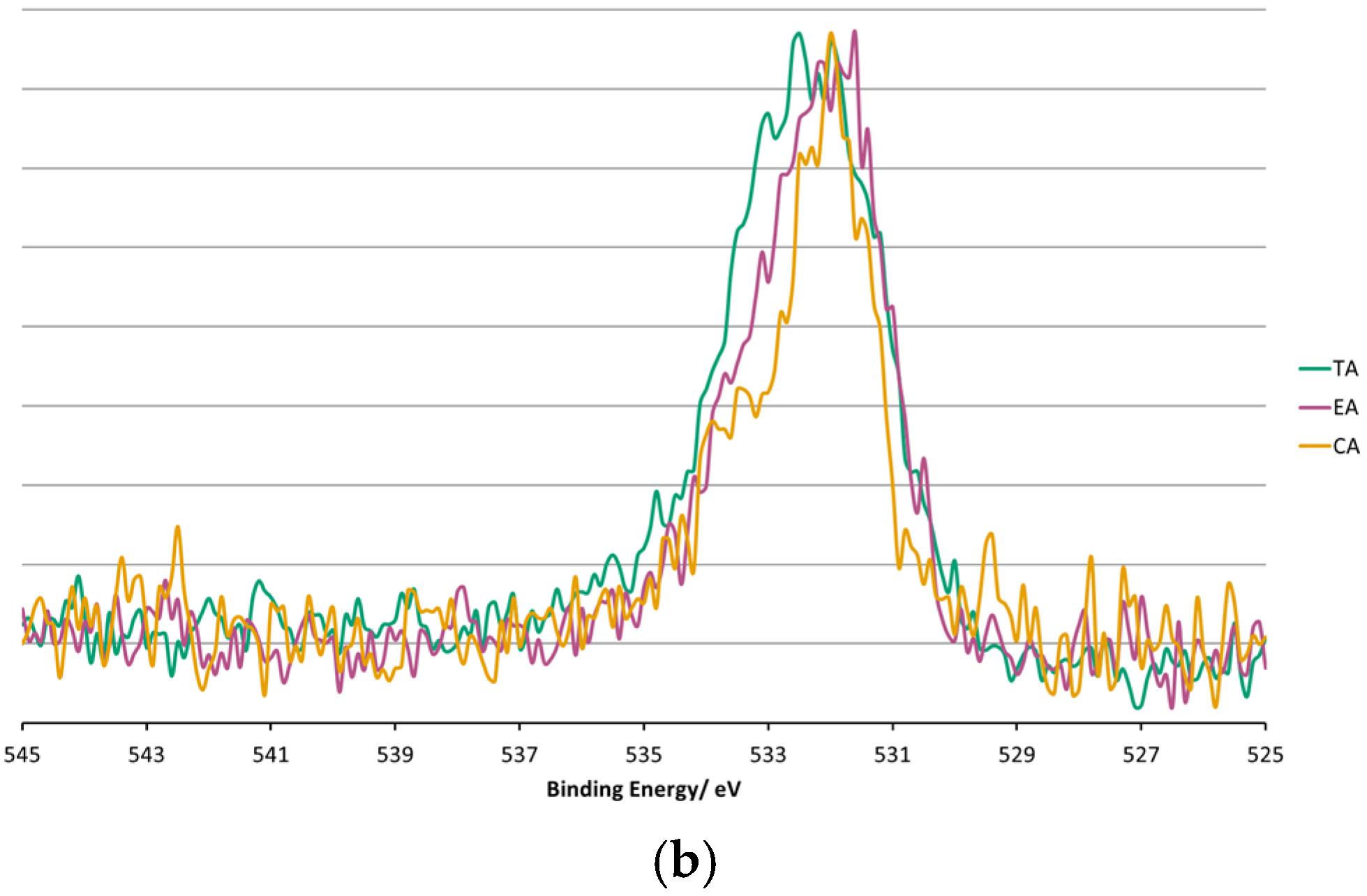

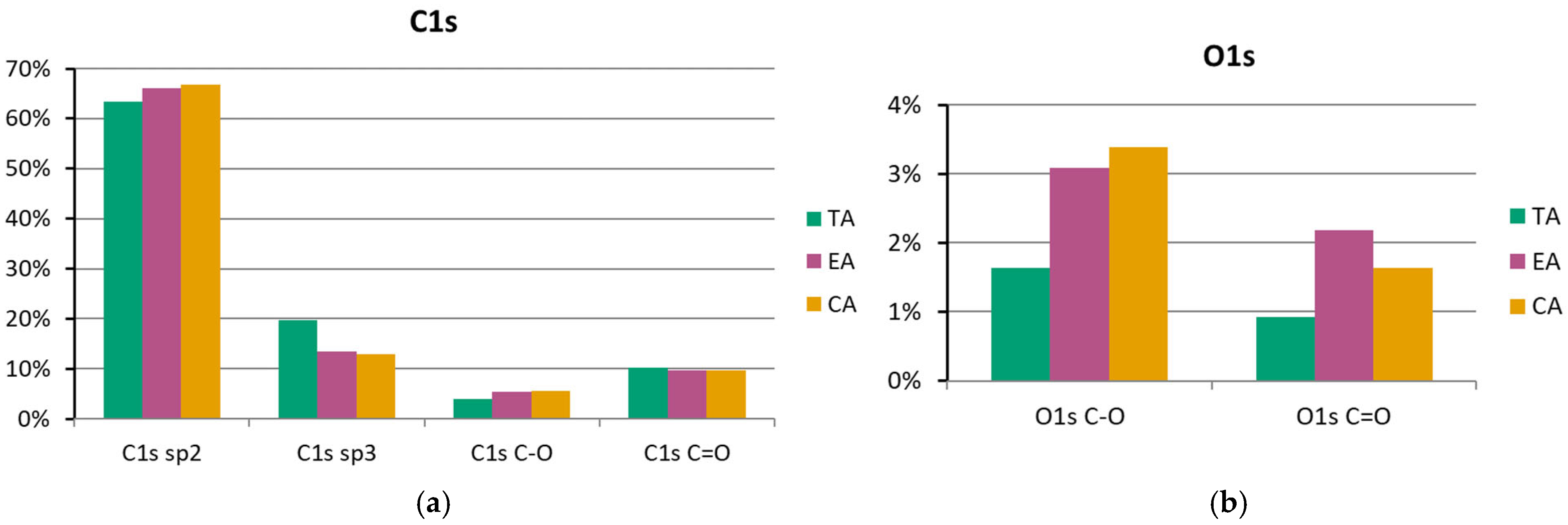

3.4. XPS Surface Chemistry Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vanadium Flow Battery Energy Storage—Invinity. Available online: https://invinity.com/vanadium-flow-batteries/?_gl=1*1q4g5a3*_up*MQ..&gclid=CjwKCAiAxc_JBhA2EiwAFVs7XOTDJZ1SfcRmGZs_4O6WNilnqdYS_RjOF1od1DK6esq_sj6_fY04lBoC8KEQAvD_BwE&gbraid=0AAAAACkMUkeHrbQ9yX7pmP3m1dPHjQ6uq (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Vanadium Redox Flow Battery (VRFB)|Long-Duration Energy Storage|Sumitomo Electric. Available online: https://sumitomoelectric.com/products/flow-batteries?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Yuan, X.Z.; Song, C.; Platt, A.; Zhao, N.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Fatih, K.; Jang, D. A review of all-vanadium redox flow battery durability: Degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 6599–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiss, R.; Meiser, C.; Goh, F.W.T. Steady-State Measurements of Vanadium Redox-Flow Batteries to Study Particular Influences of Carbon Felt Properties. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Chemical modification of graphite electrode materials for vanadium redox flow battery application—Part II. Acid treatments. Electrochim. Acta 1992, 37, 2459–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, A.M.; Clement, J.T.; Veith, G.M.; Zawodzinski, T.A.; Mench, M.M. High performance electrodes in vanadium redox flow batteries through oxygen-enriched thermal activation. J. Power Sources 2015, 294, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, Q.; Yan, C.; Qiao, Y. Corrosion behavior of a positive graphite electrode in vanadium redox flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 8783–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Tichter, T.; Khadke, P.; Zeis, R.; Roth, C. Deconvolution of electrochemical impedance data for the monitoring of electrode degradation in VRFB. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 336, 135510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, I.; Bruns, M.; Langner, J.; Fetyan, A.; Melke, J.; Roth, C. Degradation of all-vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFB) investigated by electrochemical impedance and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Part 2 electrochemical degradation. J. Power Sources 2016, 325, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreiro, S.N.; Jacquemond, R.R.; Boz, E.B.; Forner-Cuenca, A.; Bentien, A. Investigation of the positive electrode and bipolar plate degradation in vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, X.; Huang, C.; Huang, Q.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y. Experimental Validation of Side Reaction on Capacity Fade of Vanadium Redox Flow Battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 010521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhao, T.S.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, X.L.; Zhang, Z.H. In-situ investigation of hydrogen evolution behavior in vanadium redox flow batteries. Appl. Energy 2017, 190, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiss, R.; Pritzl, A.; Meiser, C. Parasitic Hydrogen Evolution at Different Carbon Fiber Electrodes in Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A2089–A2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, I.; Przyrembel, D.; Schweer, J.; Fetyan, A.; Langner, J.; Melke, J.; Weinelt, M.; Roth, C. Electroless chemical aging of carbon felt electrodes for the all-vanadium redox flow battery (VRFB) investigated by Electrochemical Impedance and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 246, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, M.; Zackin, B.I.; Sabarirajan, D.C.; Taspinar, R.; Artyushkova, K.; Liu, F.; Zenyuk, I.V.; Agar, E. Impact of Corrosion Conditions on Carbon Paper Electrode Morphology and the Performance of a Vanadium Redox Flow Battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A353–A363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.; Eifert, L.; Köble, K.; Jaugstetter, M.; Bevilacqua, N.; Fahy, K.F.; Tschulik, K.; Bazylak, A.; Zeis, R. Investigating the Influence of Treatments on Carbon Felts for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmler, N.; Bron, M. Recent Progress in our Understanding of the Degradation of Carbon-Based Electrodes in Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries—Current Status and Next Steps. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowiak, J.; Bącalski, W.; Lentka, G.; Peljo, P.; Ślepski, P. Three modes of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements performed on vanadium redox flow battery. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzelt, G. Pseudo-reference Electrodes. In Handbook of Reference Electrodes; Inzelt, G., Lewenstam, A., Scholz, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 331–332. ISBN 978-3-642-36188-3. [Google Scholar]

- AJ Torriero, A. Understanding the Differences between a Quasi-Reference Electrode and a Reference Electrode. Med. Anal. Chem. Int. J. 2019, 3, 000144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, K.K.; Jones, S. Platinum as a reference electrode in electrochemical measurements. Platin. Met. Rev. 2008, 52, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifert, L.; Jusys, Z.; Behm, R.J.; Zeis, R. Side reactions and stability of pre-treated carbon felt electrodes for vanadium redox flow batteries: A DEMS study. Carbon N. Y. 2020, 158, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifert, L.; Banerjee, R.; Jusys, Z.; Zeis, R. Characterization of Carbon Felt Electrodes for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries: Impact of Treatment Methods. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A2577–A2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, B.; Seteiz, K.; Heizmann, P.A.; Koch, S.; Büttner, J.; Ouardi, S.; Vierrath, S.; Fischer, A.; Breitwieser, M. Rapid wet-chemical oxidative activation of graphite felt electrodes for vanadium redox flow batteries. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 32095–32105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbon (C), Z = 6, & Carbon Compounds. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/pl/en/home/materials-science/learning-center/periodic-table/non-metal/carbon.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Klocek, J. Processing and Investigation of Thin Films with Incorporated Carbon Species for Possible Application as Low-k Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, der Brandenburgischen Technischen Universität Cottbus, Brandenburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hałas, E.; Bącalski, W.; Gaweł, Ł.; Ślepski, P.; Krakowiak, J. Three-Electrode Dynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy as an Innovative Diagnostic Tool for Advancing Redox Flow Battery Technology. Energies 2026, 19, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010256

Hałas E, Bącalski W, Gaweł Ł, Ślepski P, Krakowiak J. Three-Electrode Dynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy as an Innovative Diagnostic Tool for Advancing Redox Flow Battery Technology. Energies. 2026; 19(1):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010256

Chicago/Turabian StyleHałas, Eliza, Wojciech Bącalski, Łukasz Gaweł, Paweł Ślepski, and Joanna Krakowiak. 2026. "Three-Electrode Dynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy as an Innovative Diagnostic Tool for Advancing Redox Flow Battery Technology" Energies 19, no. 1: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010256

APA StyleHałas, E., Bącalski, W., Gaweł, Ł., Ślepski, P., & Krakowiak, J. (2026). Three-Electrode Dynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy as an Innovative Diagnostic Tool for Advancing Redox Flow Battery Technology. Energies, 19(1), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010256