1. Introduction

Research on PID controllers, their modifications, and extensions plays a crucial role in process control. The reason for this is simple. This algorithm, no matter the industry, country, or region, can be found in the majority of control loops in the processing industry [

1,

2]. Some reviews identify that even over 95% [

3,

4] of control loops use it. Despite the fact that it is so common, only about half of PID loops operate properly, while the rest are either incorrectly designed, not well-tuned, or never tuned. Therefore, a significant number of loops operate in manual mode (MAN), which means that automatic control (AUTO) is hardly used. This occurs due to sensor or actuator errors [

5]. This happens despite the well-known fact that poorly operating controllers bring financial losses [

6]. The use of the PID algorithm is not limited to single-input–single-output (SISO) configuration. There exist a large number of structures and control templates that enhance the PID concept, enabling its wider applicability [

7]. Recent plant-wide control systems use a decomposition to coordinate the action of several control loops and calculation blocks. Simultaneously, the PID tuning task is established, starting from Ziegler–Nichols experiments [

8] up to the SIMC (Skogestad Internal Model Control) approach [

9], which is effective and common in industry.

The simplified PID algorithm comes from the coordination of three elements: proportional, integral and derivative actions. They allow one to obtain fast proportional reactions and the incorporation of history included in the integrating term and accompanied by simple prediction delivered by the derivative term. The PIDA algorithm adds an acceleration term to the control rule. Feedback control system with this controller delivers a faster and smoother response than the one achievable by the PID in the case of third-order systems. The idea behind its design is to add an extra zero [

10]. In conclusion, theoretical analysis [

11,

12] and robustness [

13,

14] for PIDA controllers is already addressed in the literature.

The fourth term demands more tuning attention and requires modified tuning schemes [

15]. As the new algorithm is introduced, researchers try to compare it with existing PID control first [

16] or similar PIDD

2 [

17] structures. They highlight potential benefits of its applications but at the cost of higher precision needed for higher-order systems [

18]. Once the algorithm is introduced, we desire to pbtaom clear tuning rules that would allow its effective utilization and popularization. The IMC (Internal Model Control) tuning constitutes such an example as it allows tuning the PIDA algorithm for demanding, higher-order integral processes [

19] or time-delayed plants [

11].

On the other hand, PIDA educational tools support teaching and simulation-based understanding [

20]. This aspect emphasizes the importance of proper education in the development and popularization of new concepts. Recently, PIDA controllers have been used in various applications, such as control of anesthesia depth [

21], which demonstrates PIDA’s potential in areas beyond engineering. Comparison between PID and PIDA algorithms shows the advantage of PIDA in specific applications [

19]. Such comparative studies mostly focus on controller performance [

22], measured using classical control performance assessment (CPA) indexes, like mean square error (MSE) or mean absolute error (MAE). The reason is clear. Everyone wants to reach and sustain the highest performance.

The second issue is control system energy awareness and energy consumption by control actions themselves [

23,

24]. We have to be aware that each control system consumes energy itself. It is the energy spent at the execution of control actions in the form of power supply to actuating elements, like pumps, motors, or valves. This energy directly depends on certain control strategy and controller tuning. In large-scale control systems with multiple controllers, the aggregated value of the energy spent on plant actuation matters [

25].

In most cases, researchers are addressing the wear and tear actuators’ perspective and their repair costs [

26]. This work highlights a completely different perspective of control system operation energy awareness. Thus, common control key performance indicators (KPIs) should be enhanced. There exist three measures: quadratic manipulated variable (QMV), valve travel

, and valve stroke

[

26,

27].

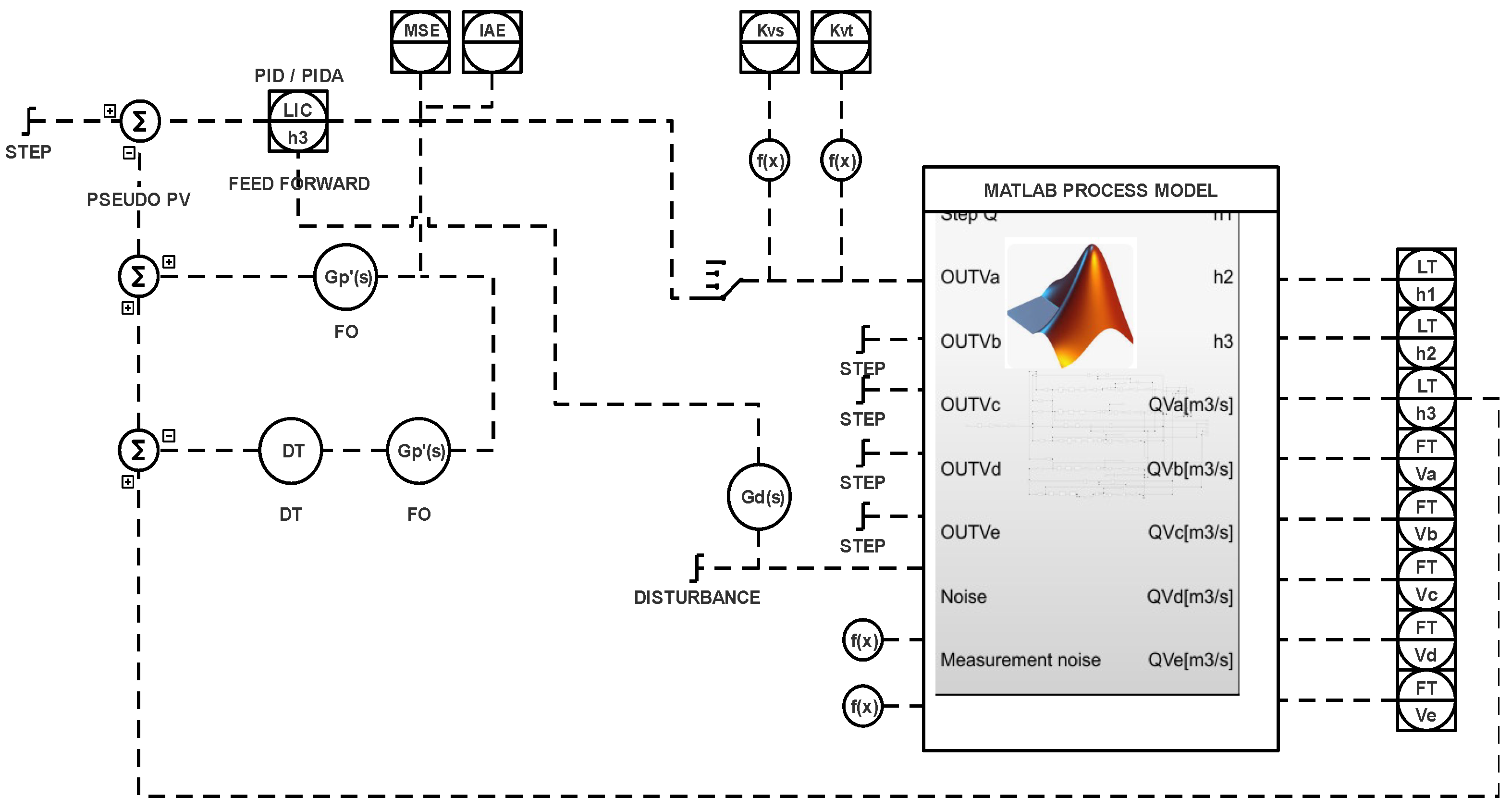

This paper introduces industrial standard of the Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) environment [

28,

29] to assess PIDA control. It combines a part of the simulated system, and the rest is realized in the real hardware. The most common configuration is that the plant is simulated (for instance, in Matlab/Simulink), while the controller is implemented in physical PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) or DCS (Distributed Control System) hardware [

30]. Such an approach allows one to assess almost real control performance, allowing the fast migration of the developed strategy to the real process, as the hardware is already programmed, and we only need to move it to the target destination. The HIL approach is also used to address cyber-security issues [

31] or energy awareness [

32].

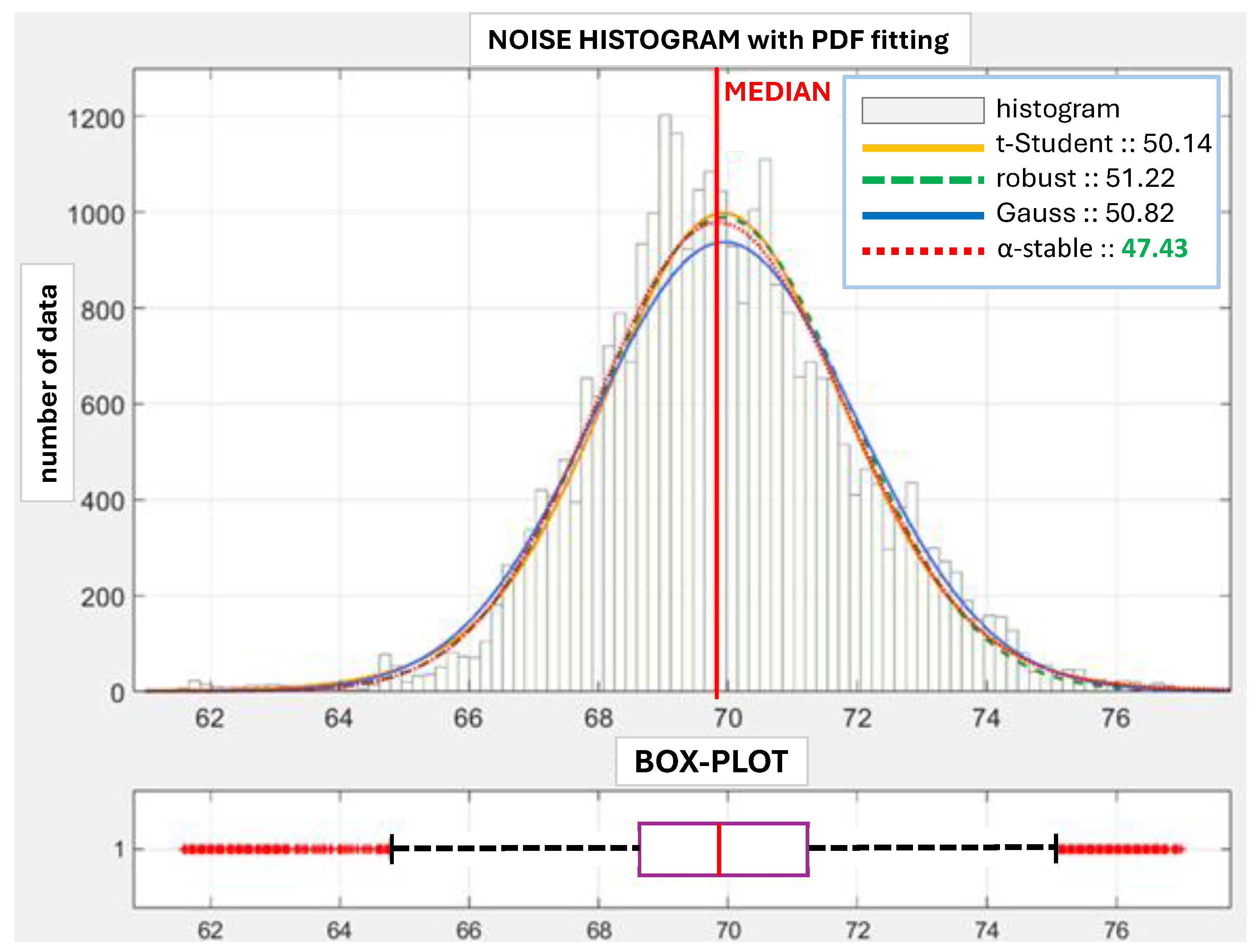

Despite the effectiveness of the PIDA algorithm, its implementation in the process industry is rare. It is difficult to answer the question of why, as there might be many answers, for instance, the lack of dedicated PIDA blocks in control systems, the need to make custom designs, insufficient tuning competences, a poor understanding of its advantages, and the lack of knowledge about its existence. This paper addresses some of these issues. It shows how PIDA algorithms can be implemented within an industrial control system. It shows how we can safely prepare the algorithm before on-site implementation using HIL simulations. Moreover, it shows the design and construction of an entire HIL environment. It shows how to reflect reality more closely through tail-aware noise identification. Finally, it addresses practical process industry aspects, not the academic approach.

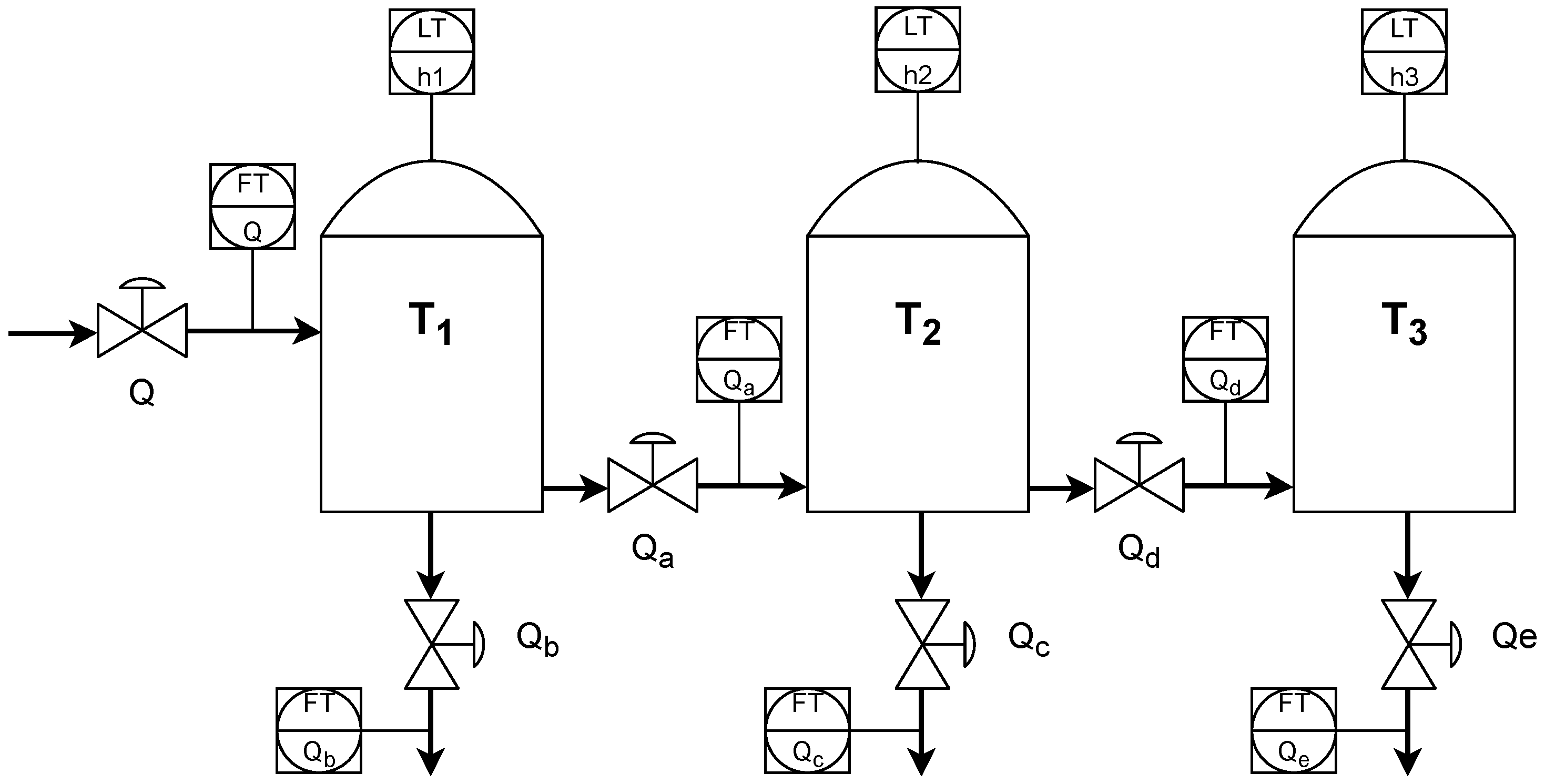

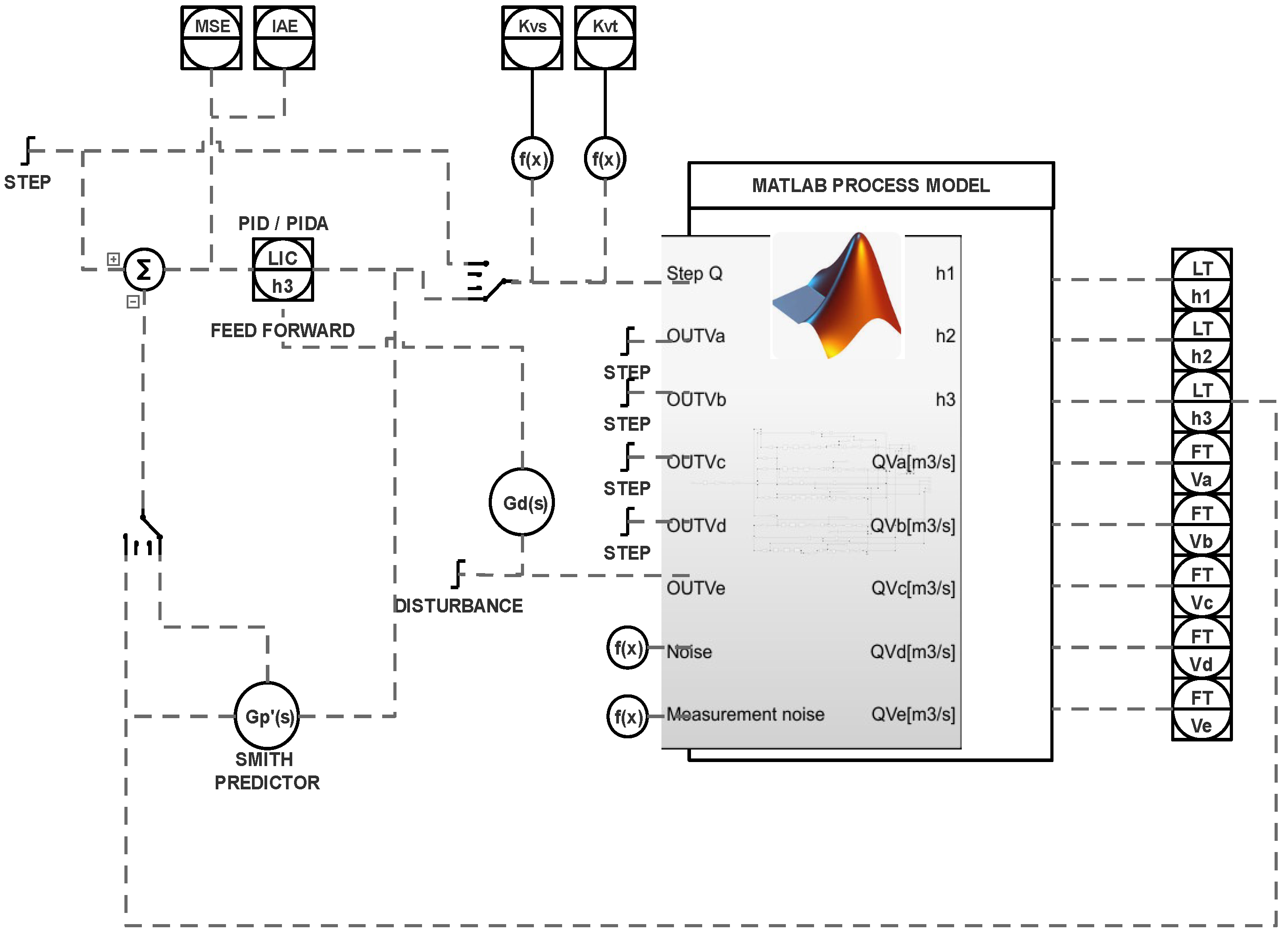

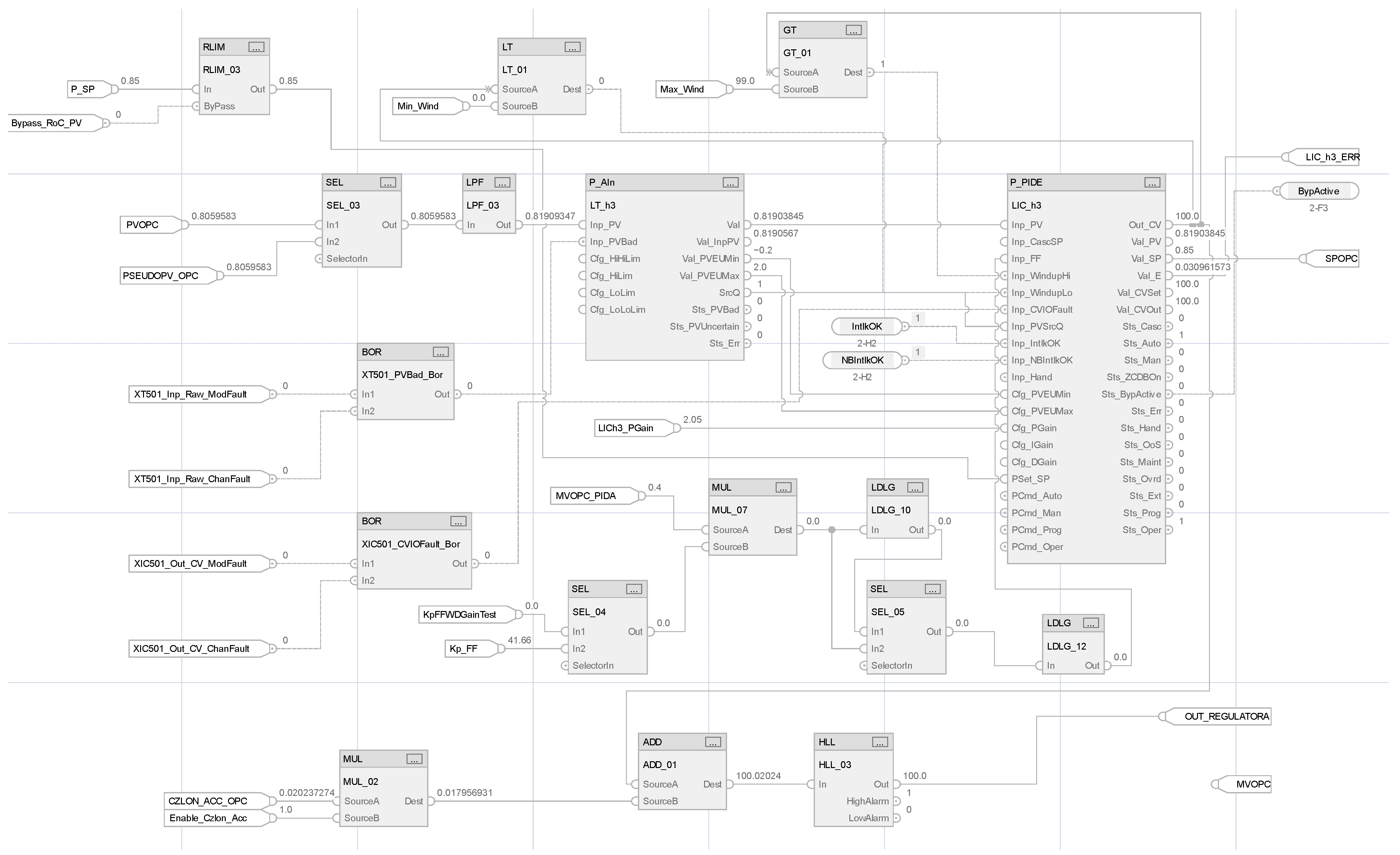

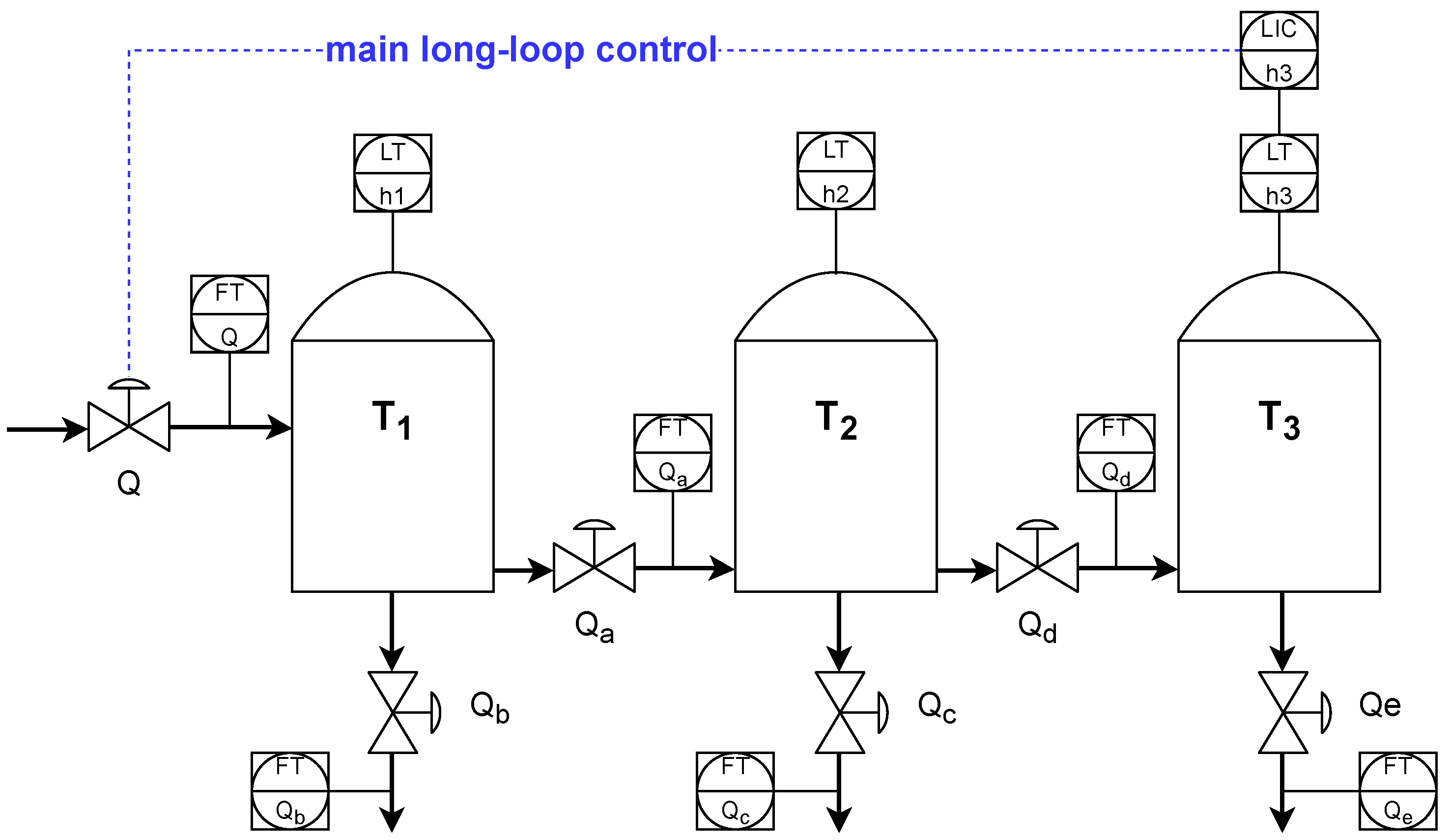

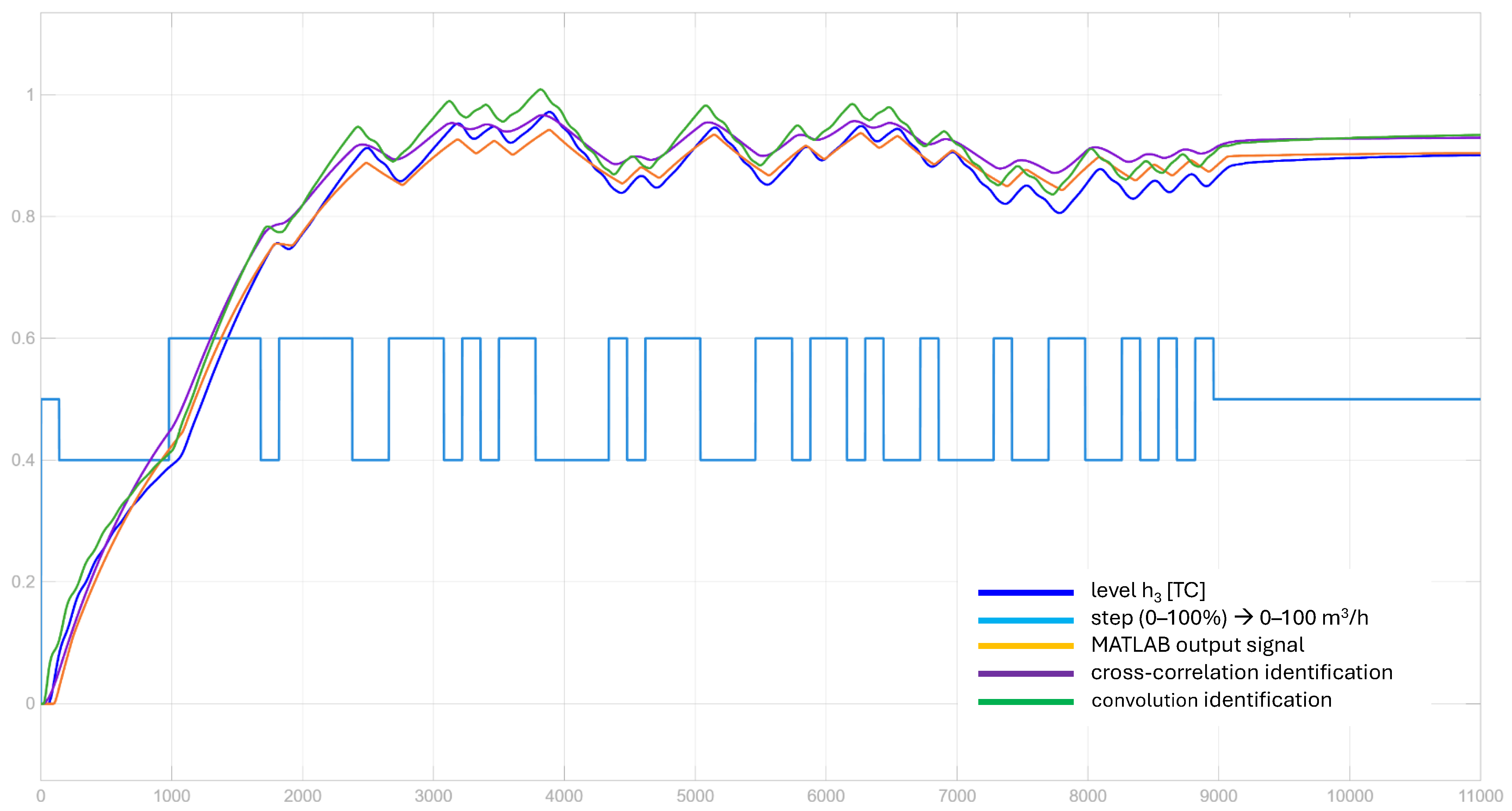

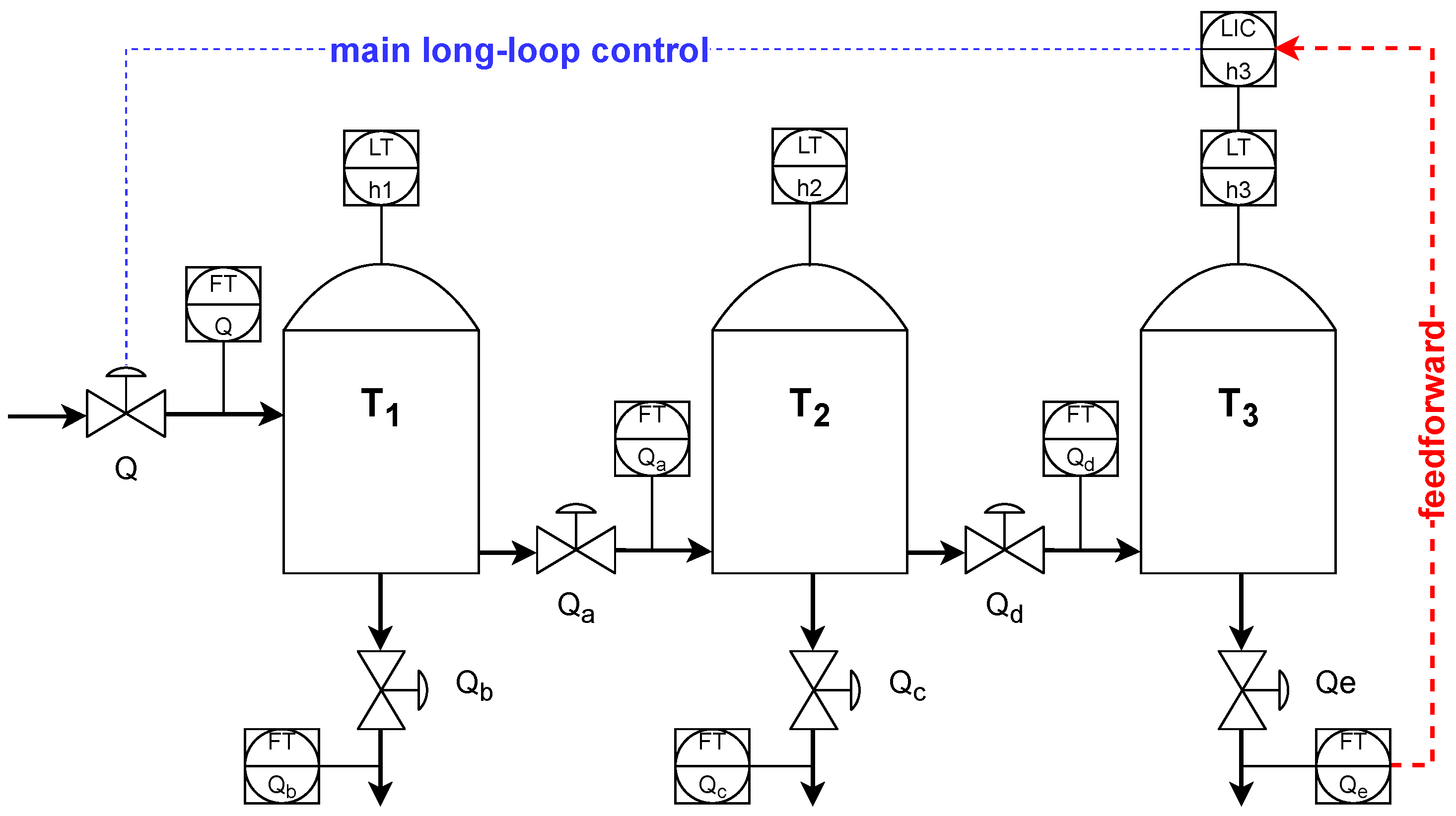

A dedicated control system with a PIDA algorithm is used to control an industrial integrating process that consists of three cascaded tanks. The real process is identified using correlation and frequency identification with a PRBS experiment. While the identified real plant is modeled and simulated with Matlab/Simulink, the PIDA algorithm is programmed in a PAC/DCS Allen–Bradley Control Logix 81ES (3MB BPCS memory, 1.5MB Safety memory) controller with the

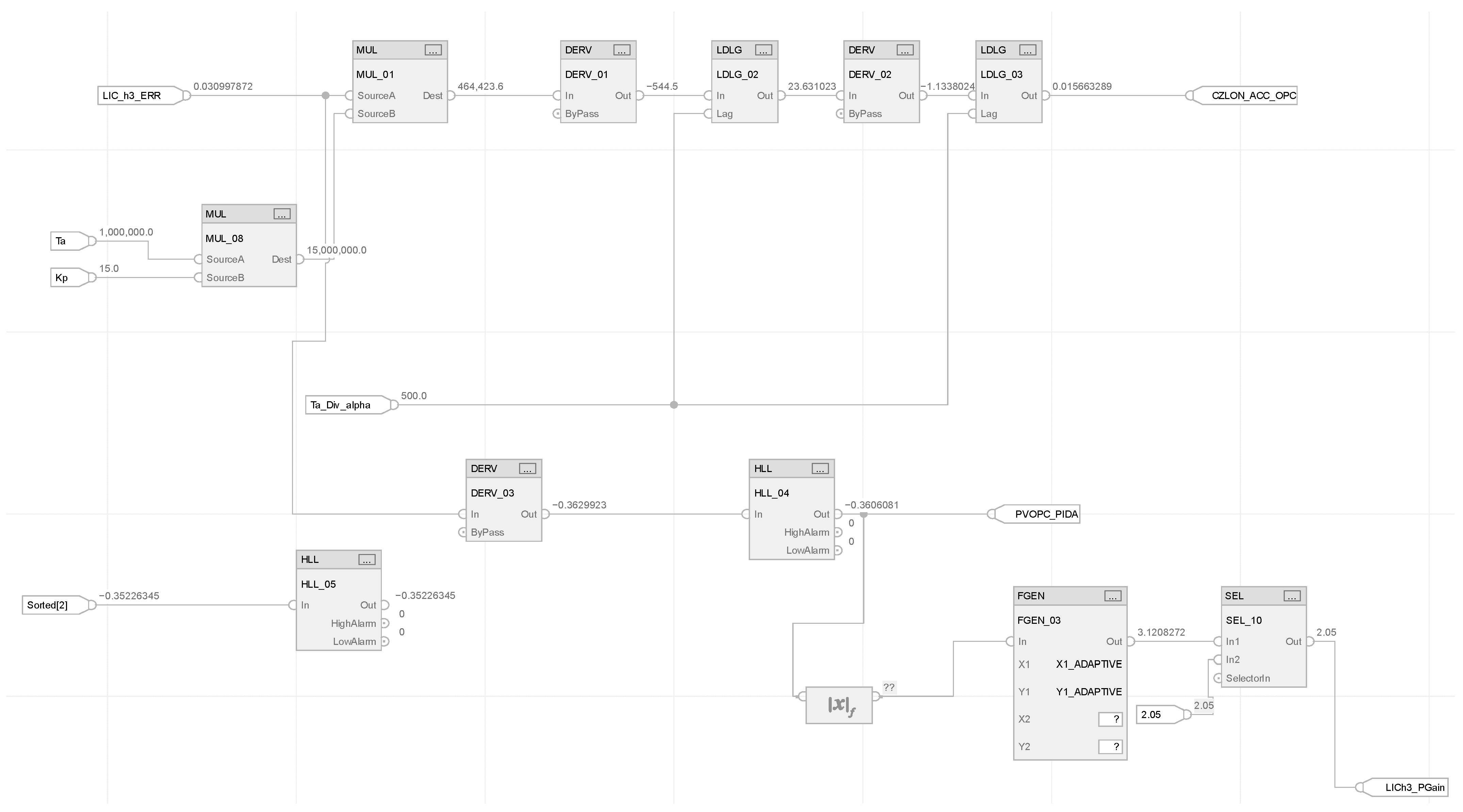

P_PIDE algorithm accompanied by an acceleration term, a process variable (PV) filter, a Smith predictor, and a disturbance compensation (static and dynamic) using the feedforward concept. Control quality assessment is performed using PV and manipulated variables (MVs). It makes controller analysis energy-aware [

33].

The HIL simulation must be put into the industrial control system design context. The design must be safe and reliable. Best practices suggest following three stages:

Dynamic simulation of the entire control system inside the simulator, like Matlab/Simulink;

Hardware-in-the-Loop simulation with real control hardware and a simulated process;

Programming of the HIL validated system in target plant hardware for fine-tuning and commissioning.

As shown above, HIL simulations allow one to safely obtain the control structure and its tuning, which can be uploaded to the target system and run with high confidence. This research shows how to carry this out for a PIDA control system. It shows how the PIDA algorithm can be programmed in the real industrial system, as there is no standard block. Additional techniques such as disturbance decoupling, filtering, and the Smith predictor are also addressed. This study explains how they can work together and what they contribute. Moreover, it shows how the simulation environment can be made more accurate using tail-aware noise models. Finally, the aspect of the energy spent on control actions is highlighted.

This paper focuses on engineering aspects of PIDA implementation. Industrial applications are subject to many challenges that must be solved before successful use. This paper addresses Hardware-in-the-Loop simulations. This stage is crucial for any industrial application of a new control strategy or algorithm, as it is the best practice approach. It allows for minimizing risks before the connection of the new concept control scheme or algorithm to the real, in this case, large-scale, industrial plant.

The control system in Matlab is not the same as the control system in DCS. The description of how the HIL validation is carried out for the new control algorithm constitutes the contribution of this paper. The paper also shows how the PIDA algorithm can be programmed in a DCS. Additionally, it should be remembered that HIL experiments are not frequent in the process industry, so the propagation of this knowledge matters.

Energy as such, as well as energy awareness of the control system, is a very practical issue, though rarely addressed in the research. Showing how better control diminishes energy consumption for control actions is very practical and can only be validated in practice. This paper shows how to do it.

The narration starts with

Section 2 that describes the methods and algorithms utilized. This is followed by

Section 2, which describes the HIL simulation environment. The results are provided in

Section 4, while the entire document is concluded in

Section 5, which also identifies open issues for further analysis.

5. Conclusions and Further Research

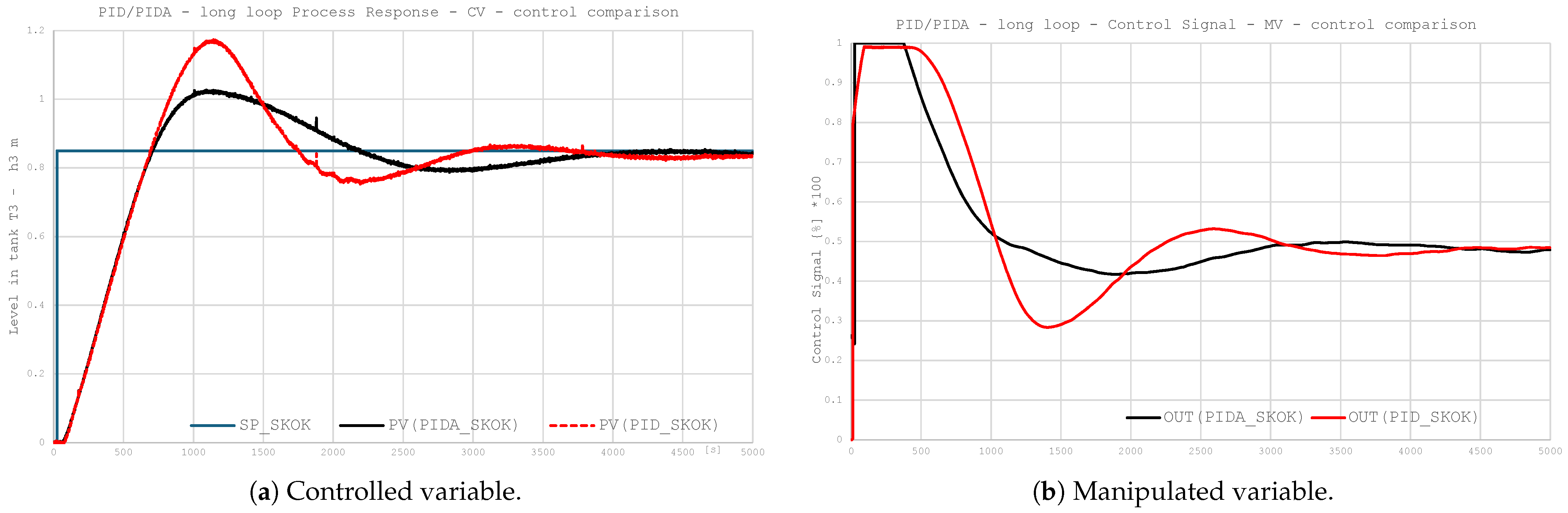

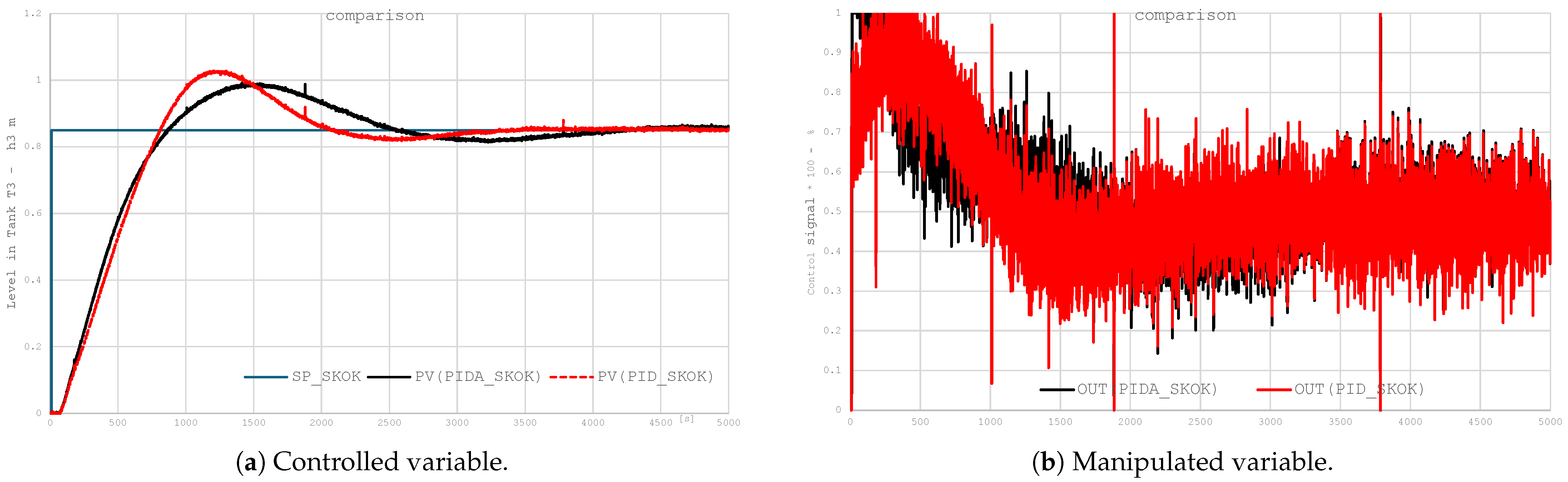

The aim of this research is to compare the quality of control achieved by a classical PID and its extended PIDA version for a system with large inertia and long delays. Secondly, the HIL simulation is considered as a crucial step in industrial control system design.

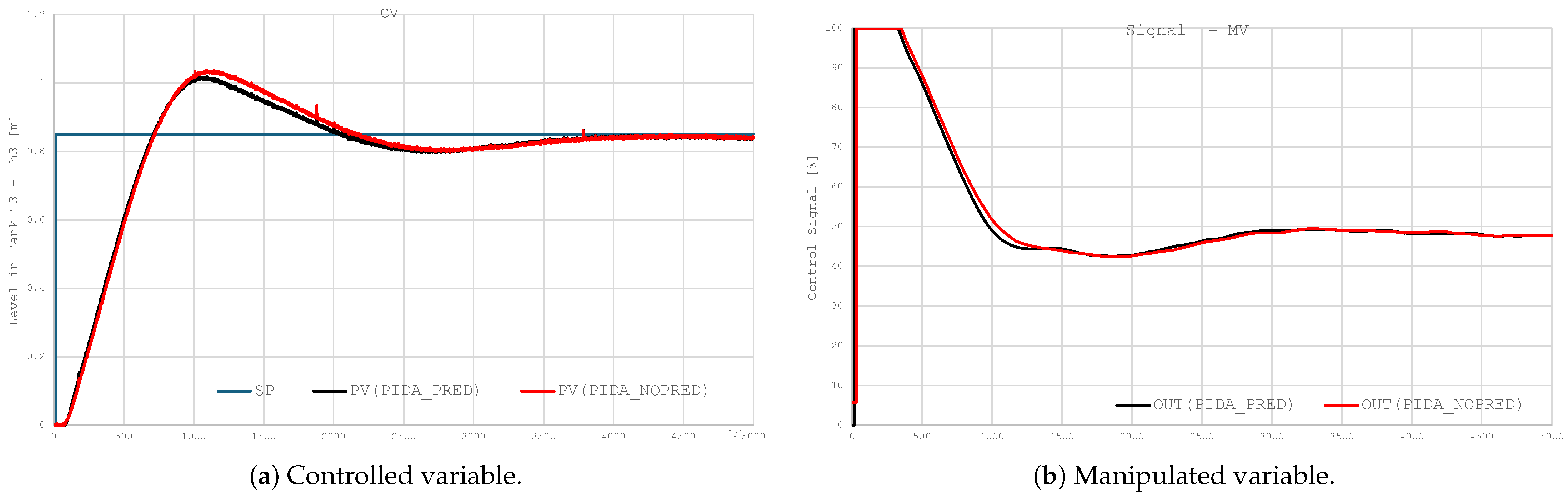

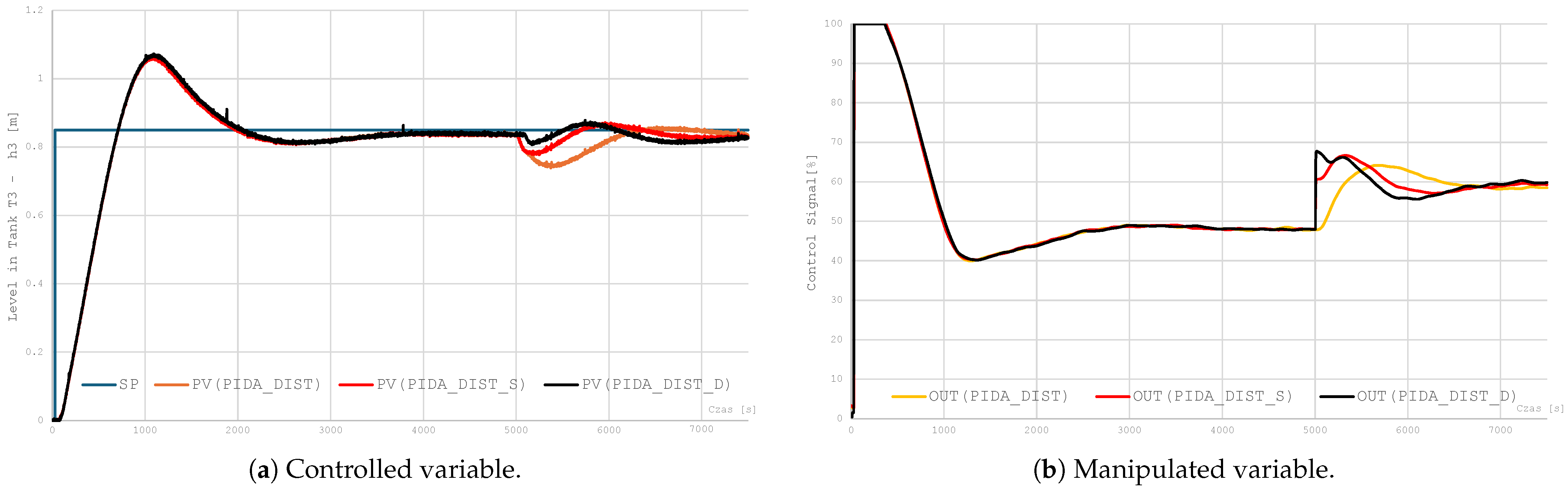

The PIDA controller, by introducing an acceleration term (a second derivative of control error), enables active shaping of the closed-loop system’s transfer function by generating additional transfer function zeros, which translates into increased phase margin, reduced oscillations, and improved damping of the object’s dynamics. An analysis of the results shows the superiority of the PIDA controller over the classic PID controller. The PIDA controller allows us to achieve lower overshoot values and a smoother approach to the setpoint, i.e., with shorter rise times and minimized oscillations. However, the introduction of an acceleration term requires the use of advanced signal filtering, which mitigates actuators’ energy consumption and makes the design process energy-aware.

The complex structure of the PIDA controller significantly increases the number of parameters requiring tuning: in addition to the standard dynamic parameters of the PID controller , , and , it is also necessary to select the gain of the acceleration term , differential filtering constant , and parameters of the PV filters. The implementation of the PIDA controller in the DCS system is carried out exclusively on the basis of standard function blocks available in the software, which significantly facilitates its programming and at the same time reduces the risk of implementation errors. The algorithm is expanded with additional differentiation and filtering maintaining readability of the control code.

The overall results clearly confirm the effectiveness of the PIDA controller as a control tool for plants with complex dynamics and processes sensitive to overshoot. The work highlights the active influence of PIDA control on the shaping of control signals, reducing energy consumption for control-related actions and the wear and tear of actuators.

The research also shows that HIL simulations can be effectively used as a testing platform to evaluate new control techniques, shortening the design time and making the whole implementation process safer and more reliable.

One of the key directions for further research is the development of standardized methods for PIDA controller auto-tuning, taking into account the multidimensional characteristics of the parameter space and controller energy awareness. The introduction of such methods would allow for a wider use of the PIDA controller in industrial applications, where the complex tuning task requiring expert knowledge remains a limitation.