Comparison of Direct and Indirect Control Strategies Applied to Active Power Filter Prototypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

| No. | Control Strategies of the APF Prototypes | Abbreviation of the Implemented Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Developed on the principle of instantaneous powers (PQ) | FAP-0S |

| 2 | Developed on the principle of synchronous algorithm (DQ) | FAP-0US |

| 3 | Developed on the principle of maximum (MAX) | FAP-0IA |

| 4 | Developed on the principle of indirect control (CI) | FAP-0ET |

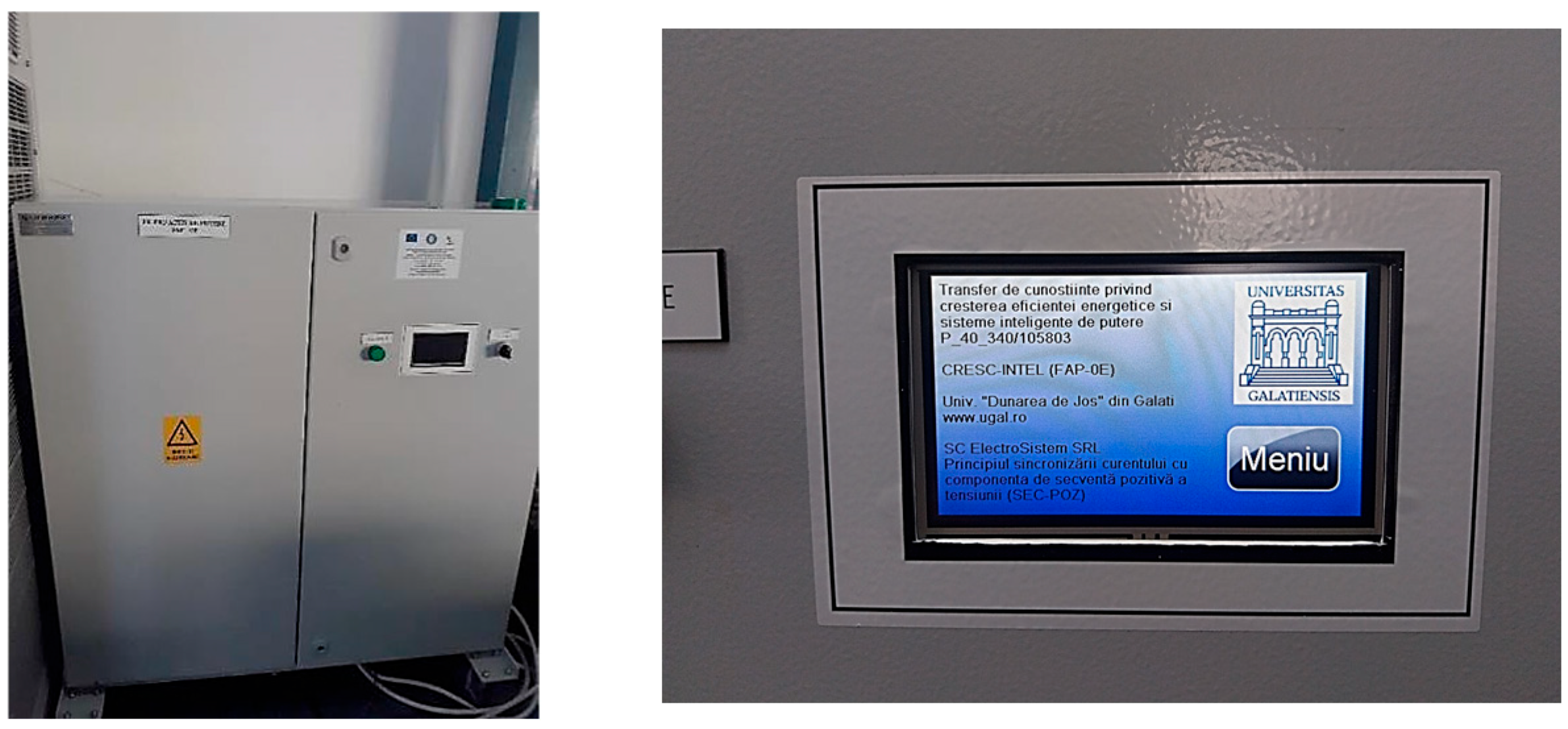

| 5 | Developed on the principle of synchronization of current with the voltage positive-sequence component (SEC-POZ) | FAP-0E |

| 6 | Developed on the low-pass filter separating polluting components method (LPF) | FAP-0SE |

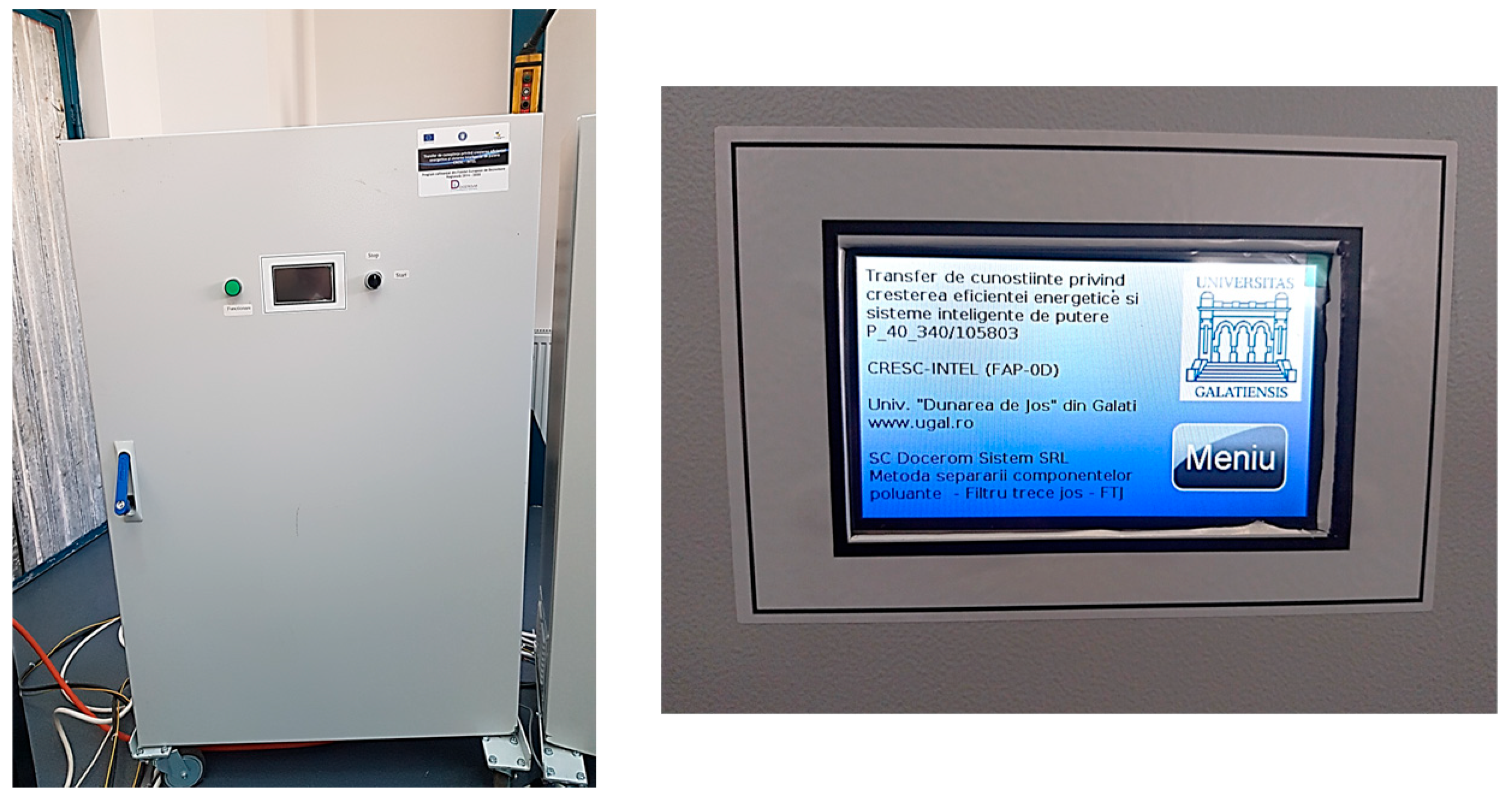

| 7 | Developed on the band-stop (notch) filter separating polluting components method (BSF) | FAP-0D |

- The validation of shunt active power filter control strategies implemented on industrial prototypes.

- Demonstration of the applicability of both experimental and prototype systems across a wide range of electrical parameters.

- Implementation of power systems in real-time using versatile, reconfigurable electronic circuits based on FPGA technology.

- Comparative analysis of various active power filter control strategies under both direct and indirect operation modes.

- Identification of the most efficient compensation solution based on distortion analyses of the implemented control strategies on the industrial active power filter prototypes.

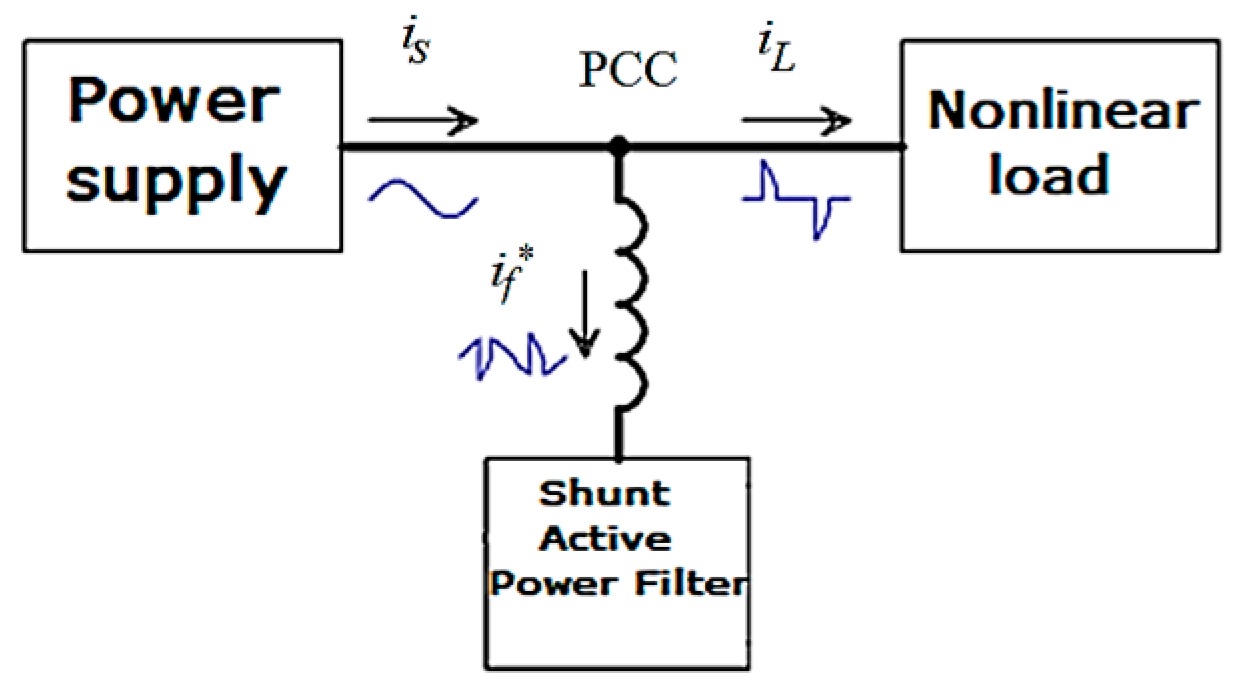

2. Materials and Methods

- Polluting Component Separation Control—Band-Stop Filter (BSF, FAP-0SE): In this strategy, the load currents are processed through a band-stop filter designed to remove the fundamental frequency, resulting in reference currents that correspond to the harmonic components for all three phases [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

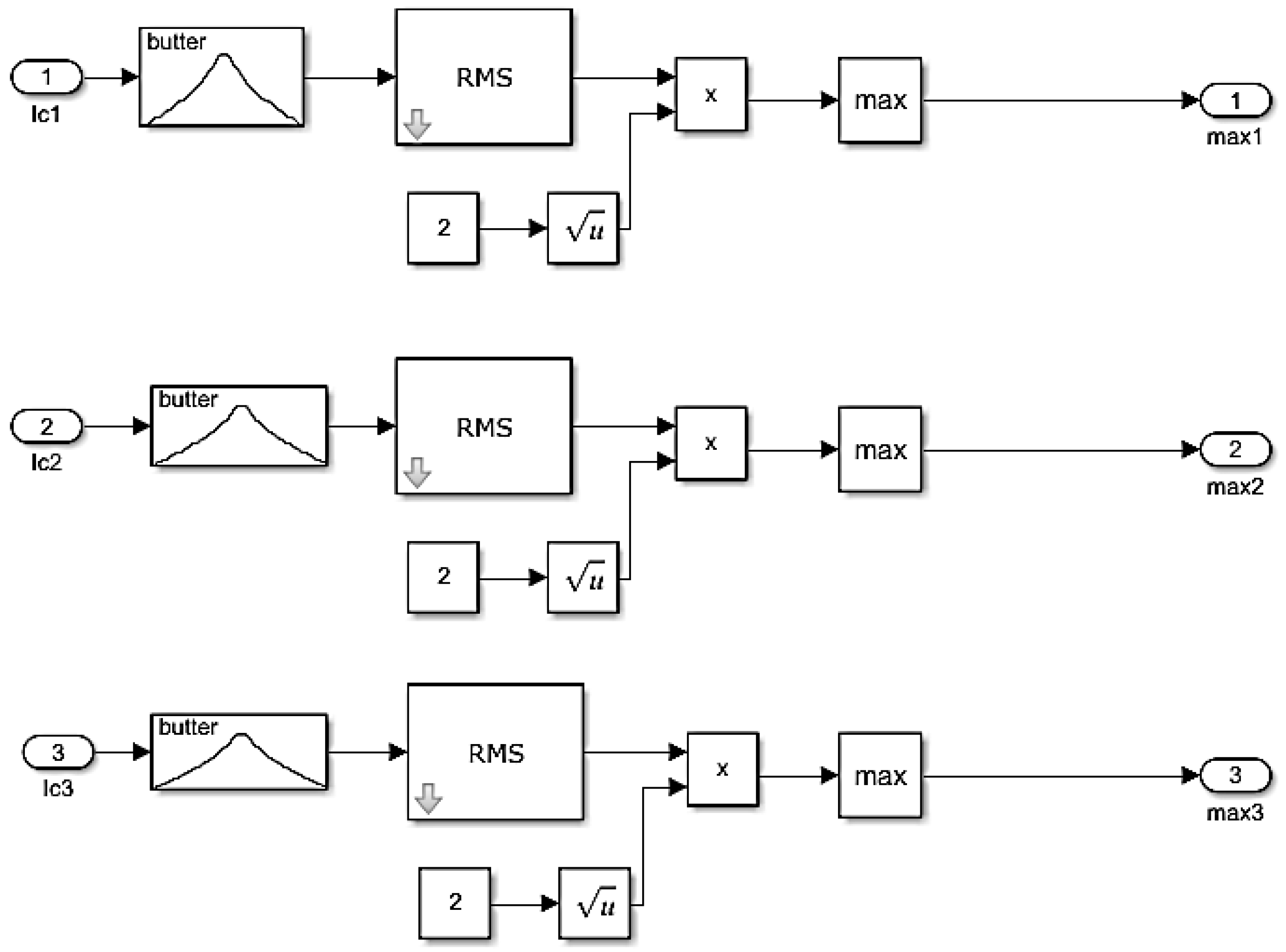

- Maximum Principle Control (MAX, FAP-0IA): This strategy filters the distorted load current to extract its fundamental component. The alternating current generated by the active filter is made to follow the reference signal obtained from the current reference generator. In this method, the distorted load current passes through a band-pass filter tuned to the fundamental frequency (50 Hz), which introduces zero gain attenuation and a 180° phase shift. As a result, the filter output equals the fundamental component of the load current but is phase-shifted by 180°. By adding the load current to this phase-shifted fundamental component, the reference current waveform required to compensate only for the harmonic distortion is obtained. Additionally, to provide the reactive power demanded by the load, the signal from the band-pass filter is synchronized with the corresponding source phase voltage. Consequently, the active filter current leads its voltage, supplying the required reactive power while absorbing the real power needed to maintain constant DC-link voltage and compensate for switching losses [73,74,75,76].

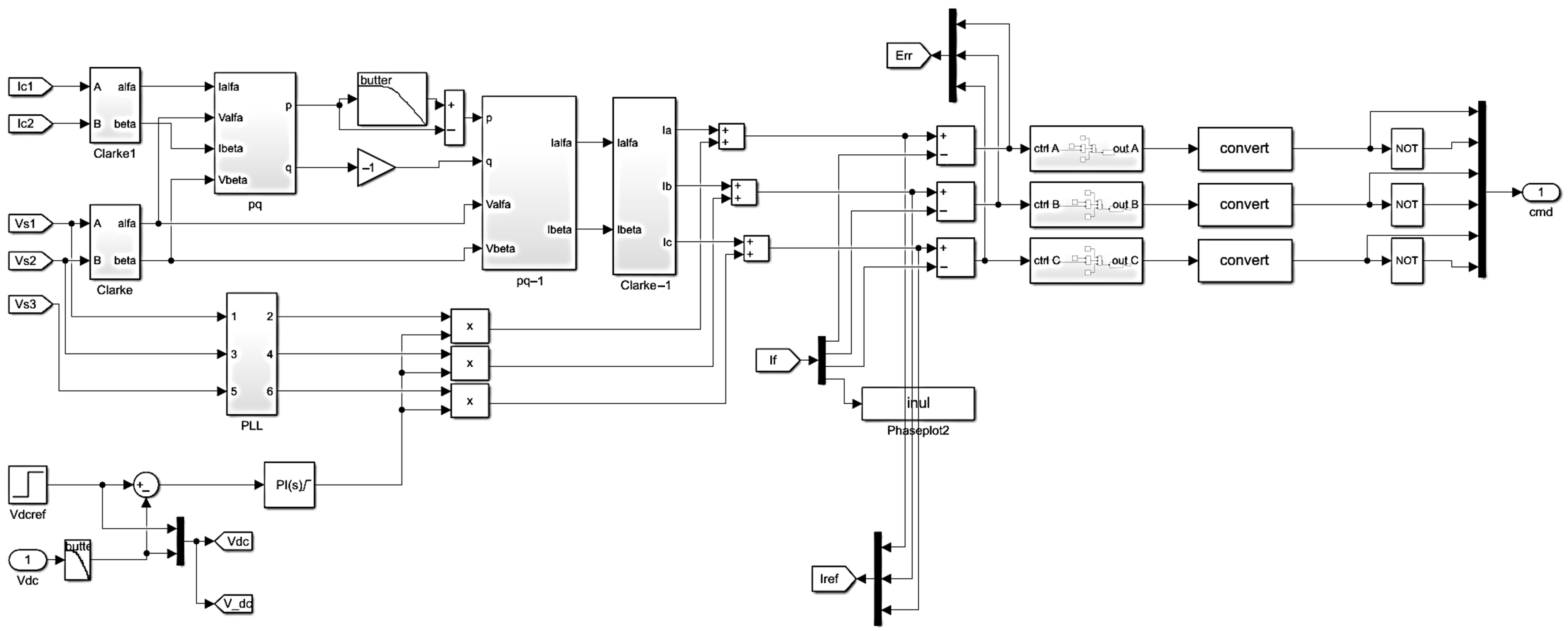

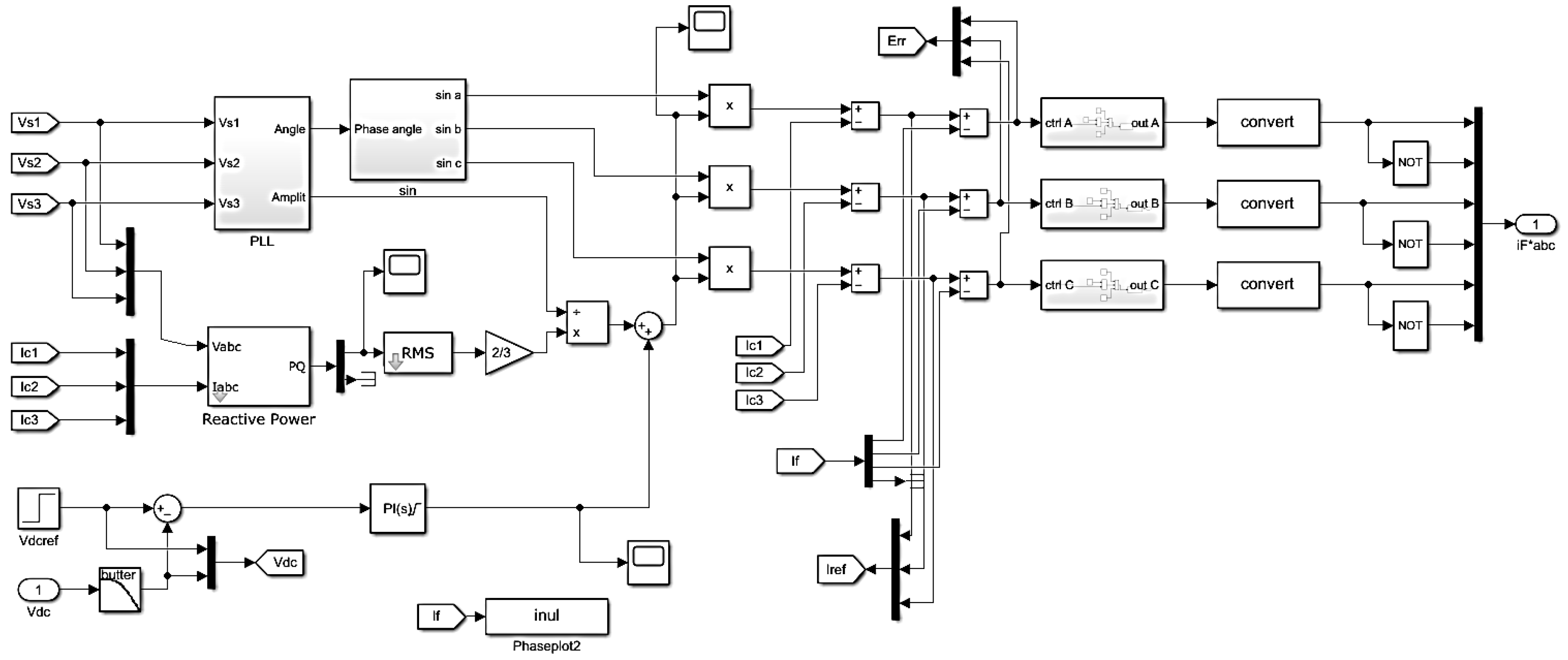

- Instantaneous Power Control (PQ, FAP-0S): This method compensates for harmonic currents in both balanced and unbalanced voltage conditions by using the instantaneous power theory. The control algorithm calculates the instantaneous active and reactive powers of the load and determines the appropriate compensating currents that the active filter must inject. By doing so, the harmonic and reactive power components are effectively mitigated, ensuring that the supply current remains as close as possible to a sinusoidal waveform and in phase with the source voltage [9,77,78,79,80,81].

- Synchronous Reference Frame Control (DQ, FAP-0US): This method uses the synchronous DQ reference frame to extract the harmonic components of the load current. By transforming the three-phase load currents into the rotating DQ frame, the harmonic and reactive components can be separated from the fundamental active component. The active power filter then injects the compensating currents to cancel out these distortions, ensuring that the supply current remains sinusoidal and in phase with the source voltage. This approach is effective for both balanced and unbalanced loads, providing precise harmonic mitigation in dynamic conditions [82,83,84,85,86,87,88].

- Control based on Separation of Polluting Components—Low-Pass Filter (LPF, FAP-0D): This method employs a low-pass filter to extract the fundamental component of the load current, isolating it from the harmonic (polluting) components. The active power filter then injects currents that compensate for the harmonics, ensuring that the supply current remains sinusoidal and in phase with the grid voltage. This approach is particularly useful for effectively reducing harmonic distortion while maintaining the reactive power requirements of the load [89,90,91].

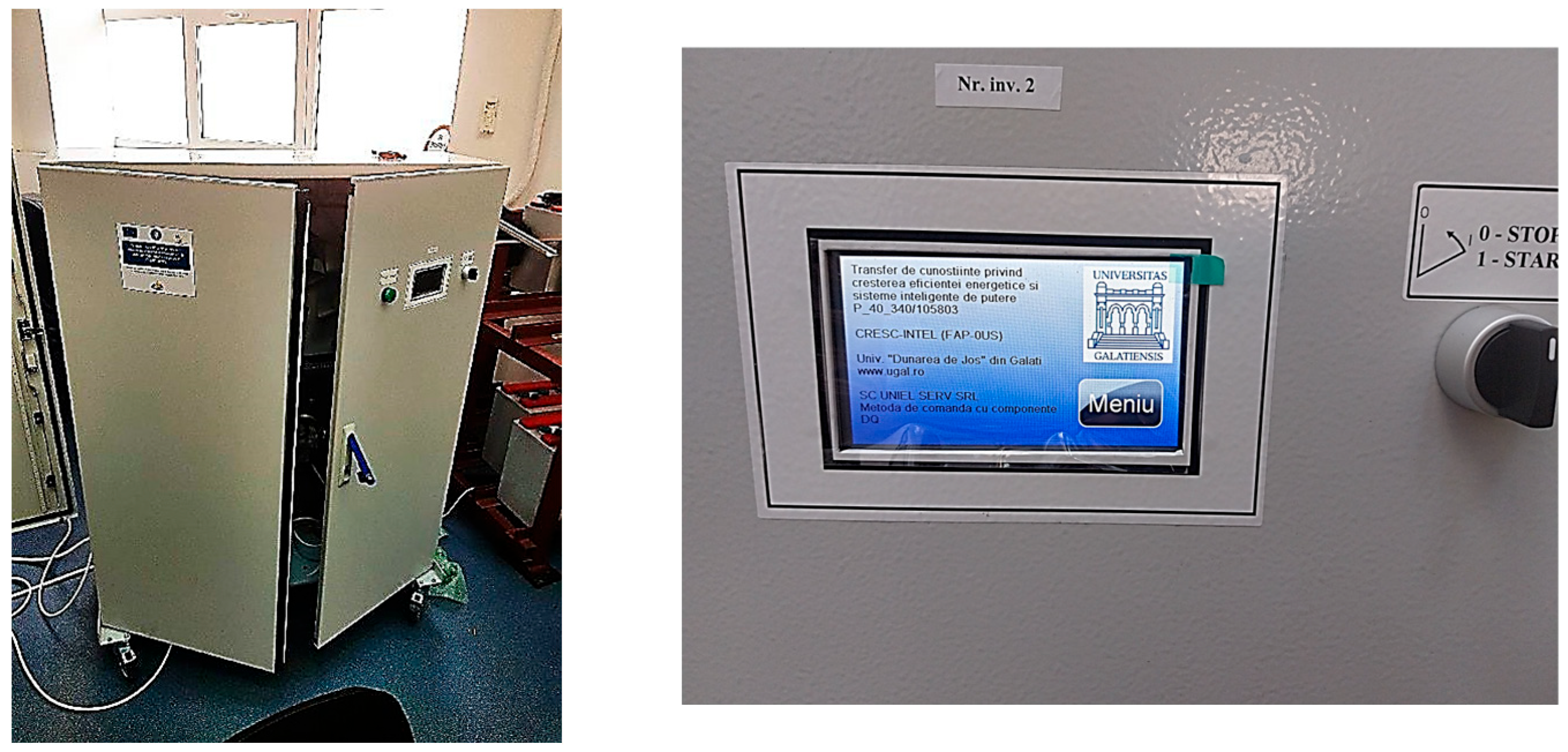

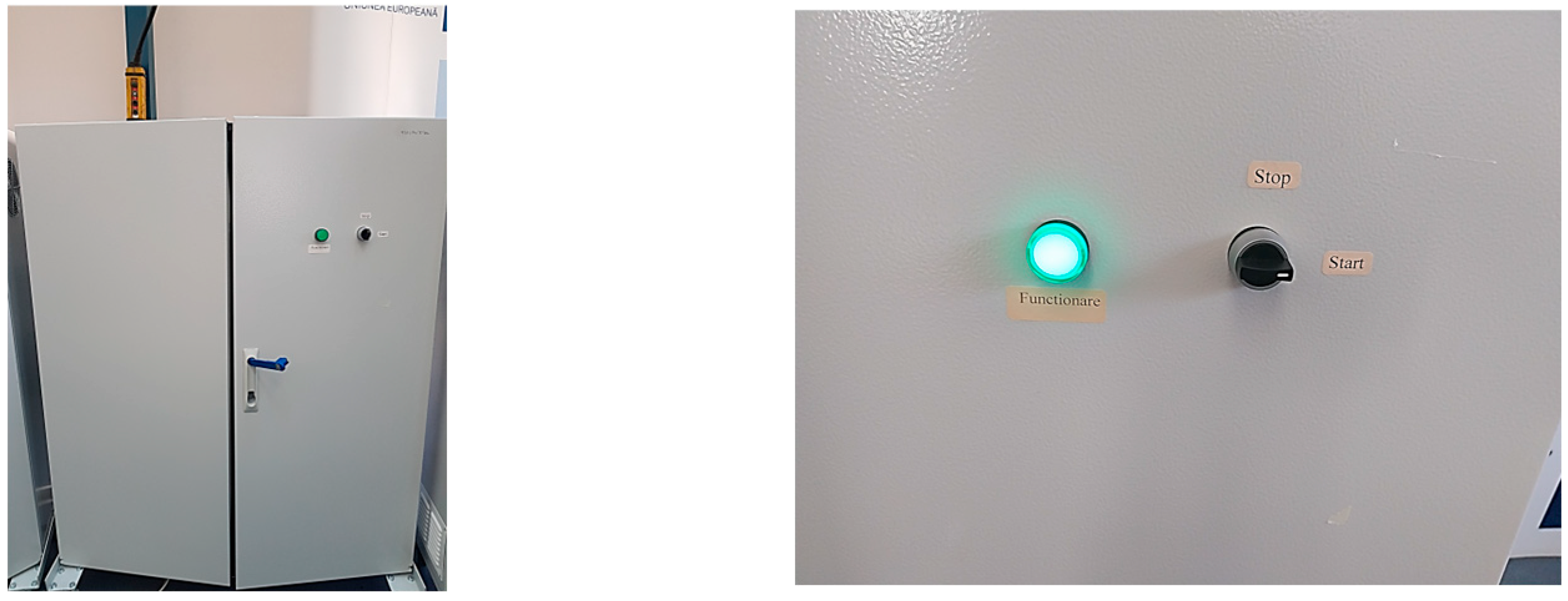

3. Main Technical Data of the SAPF Prototypes

4. Numerical Results

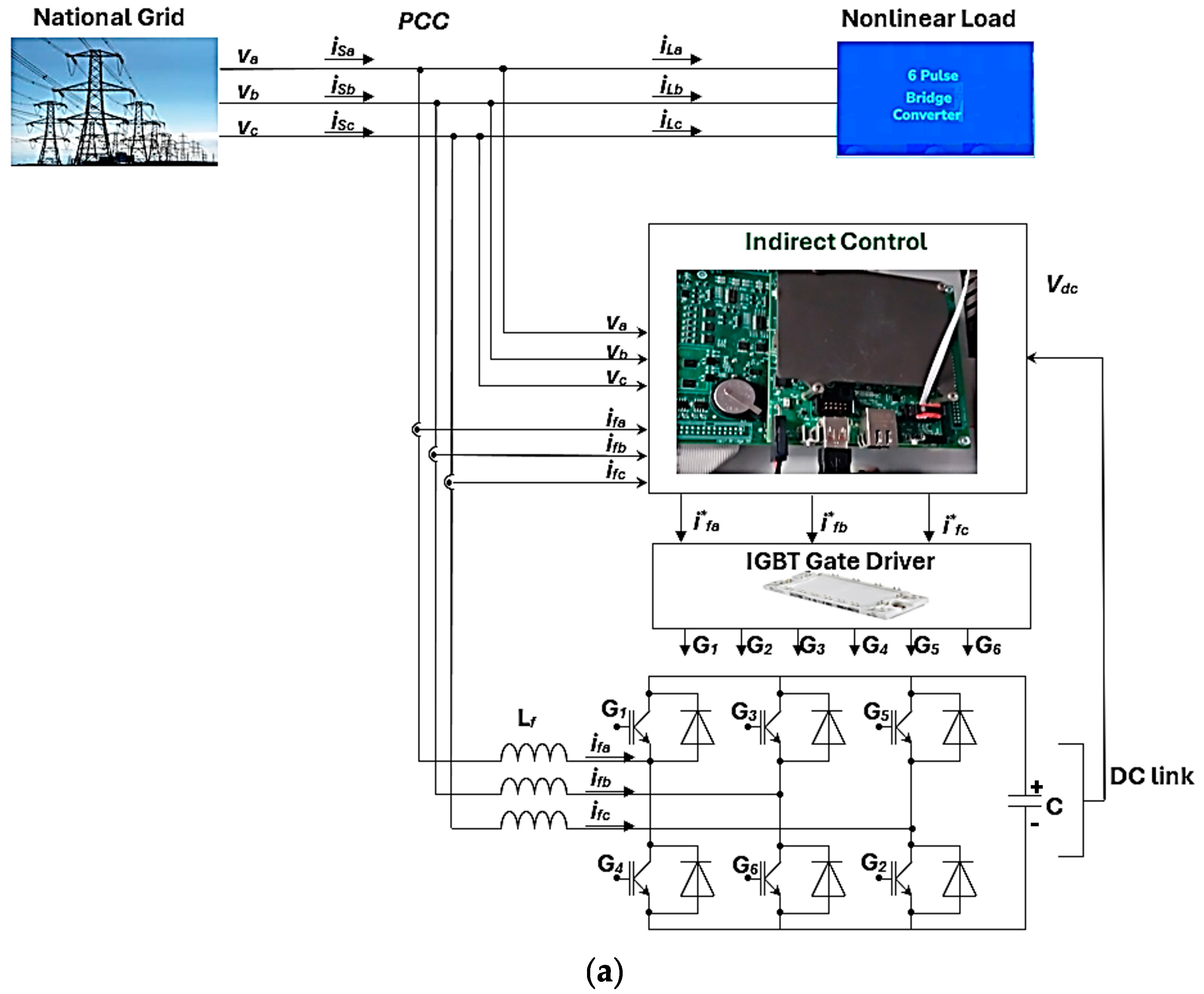

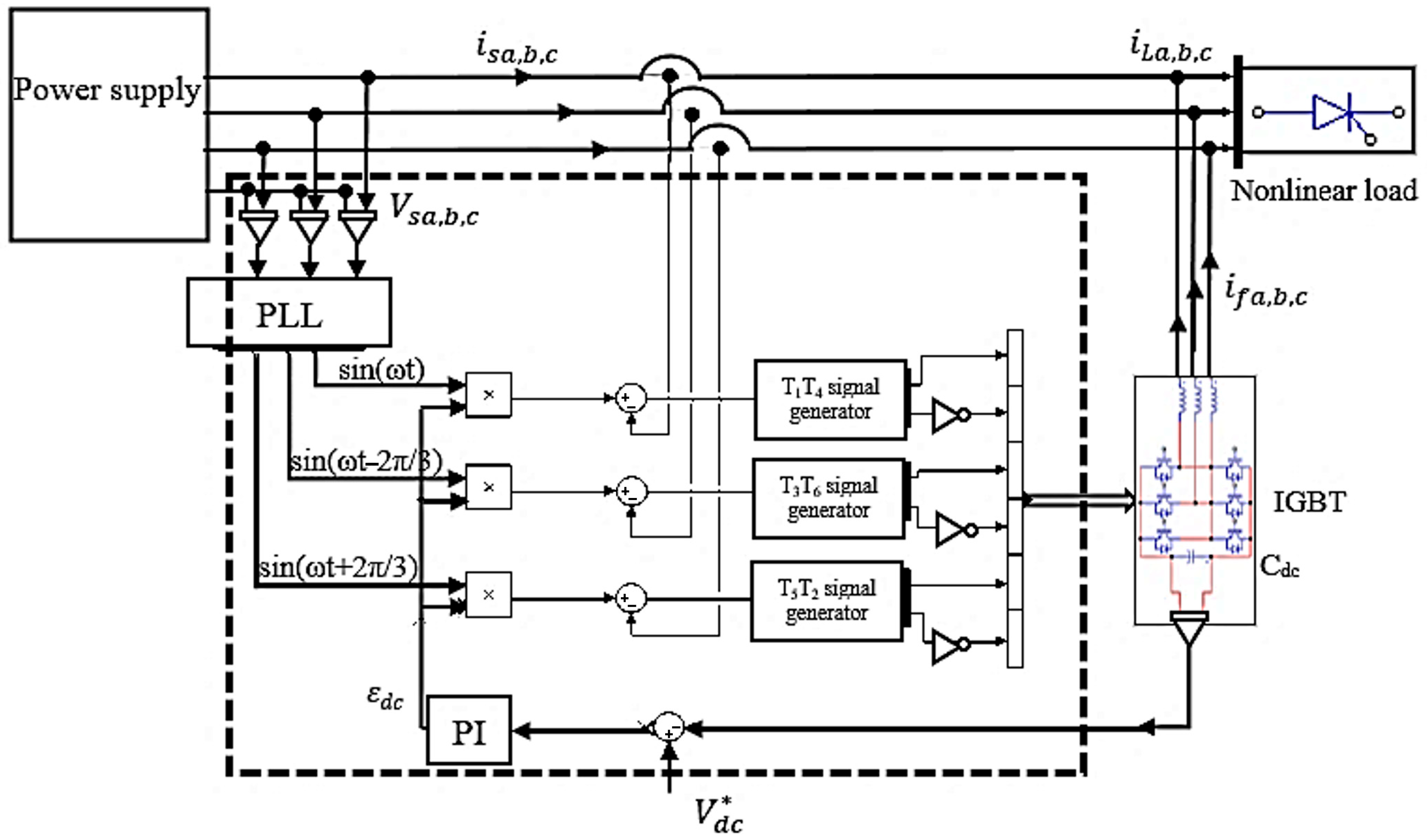

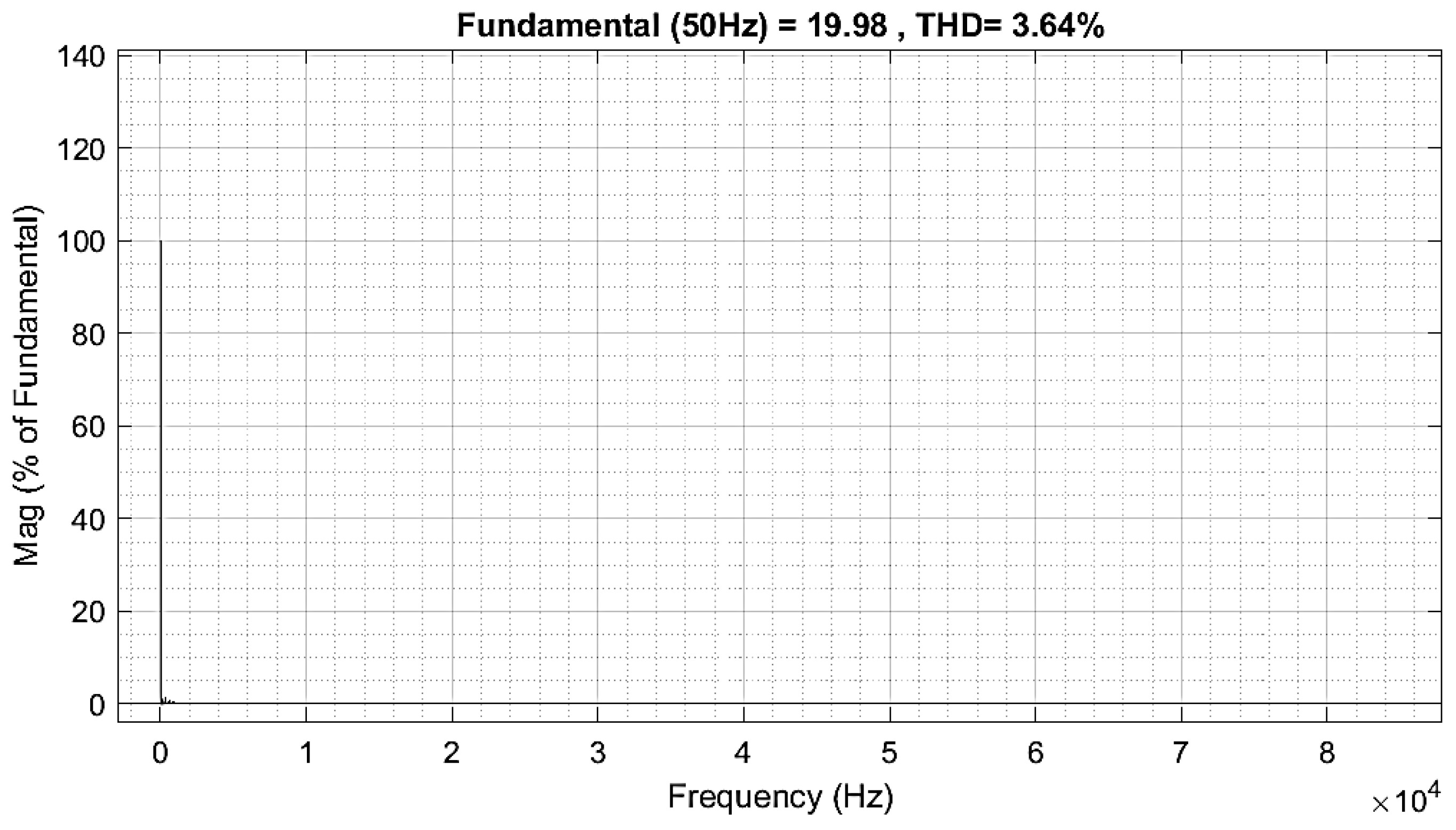

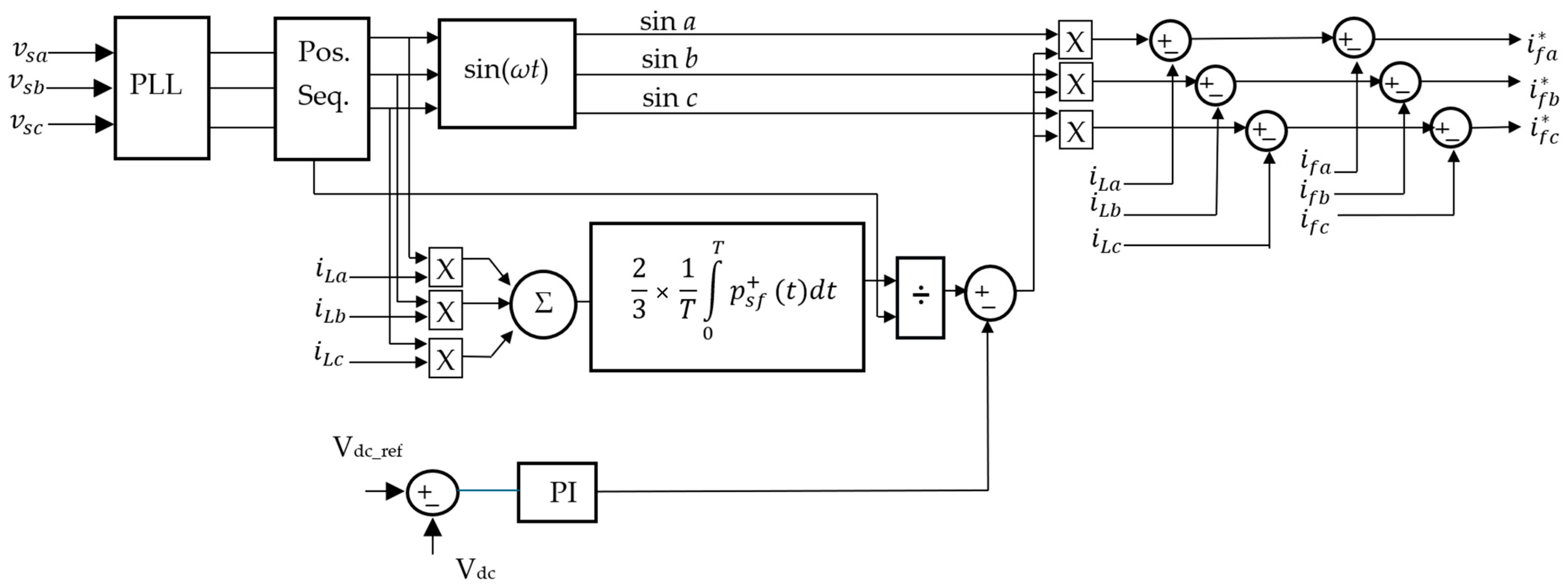

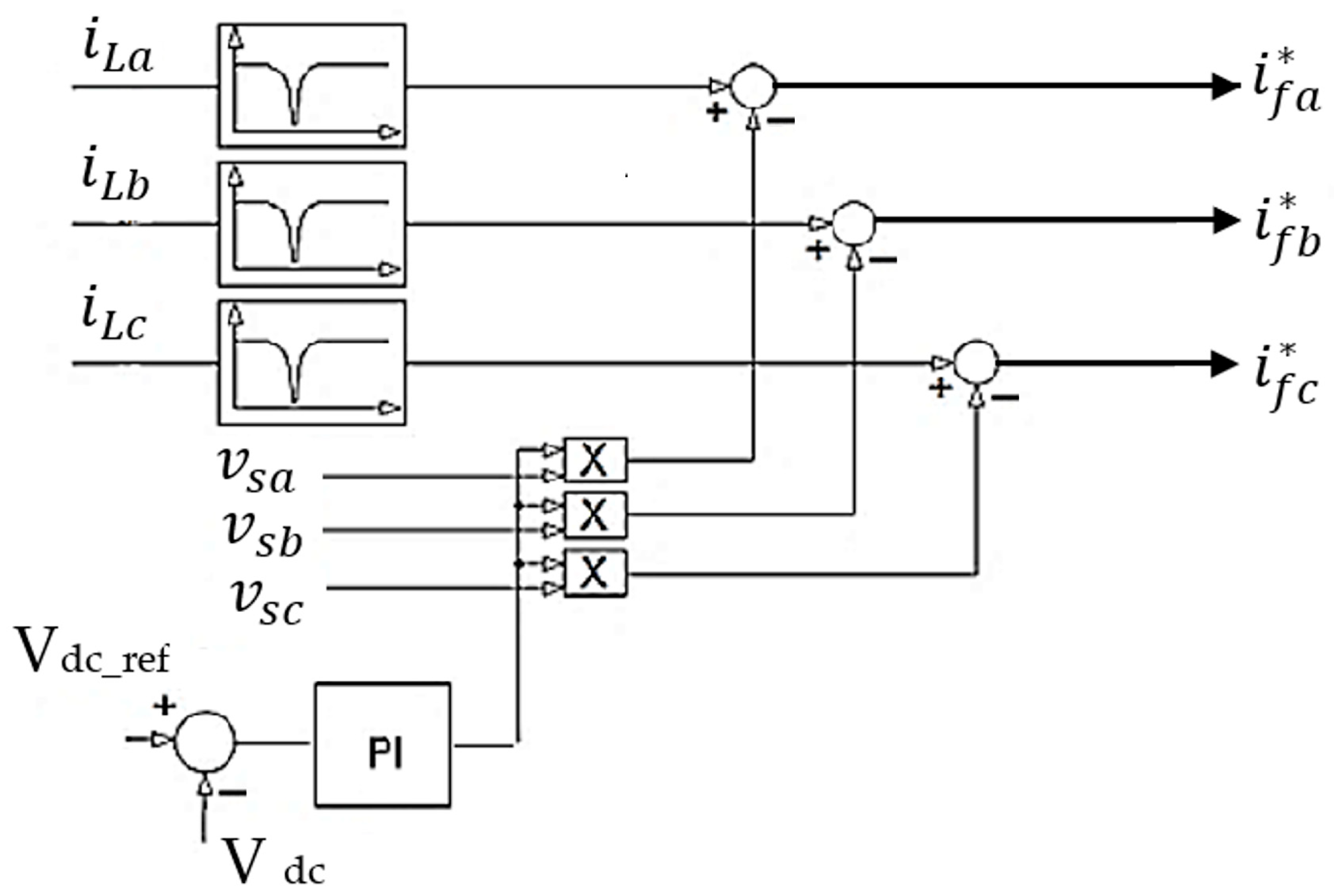

4.1. Indirect Control

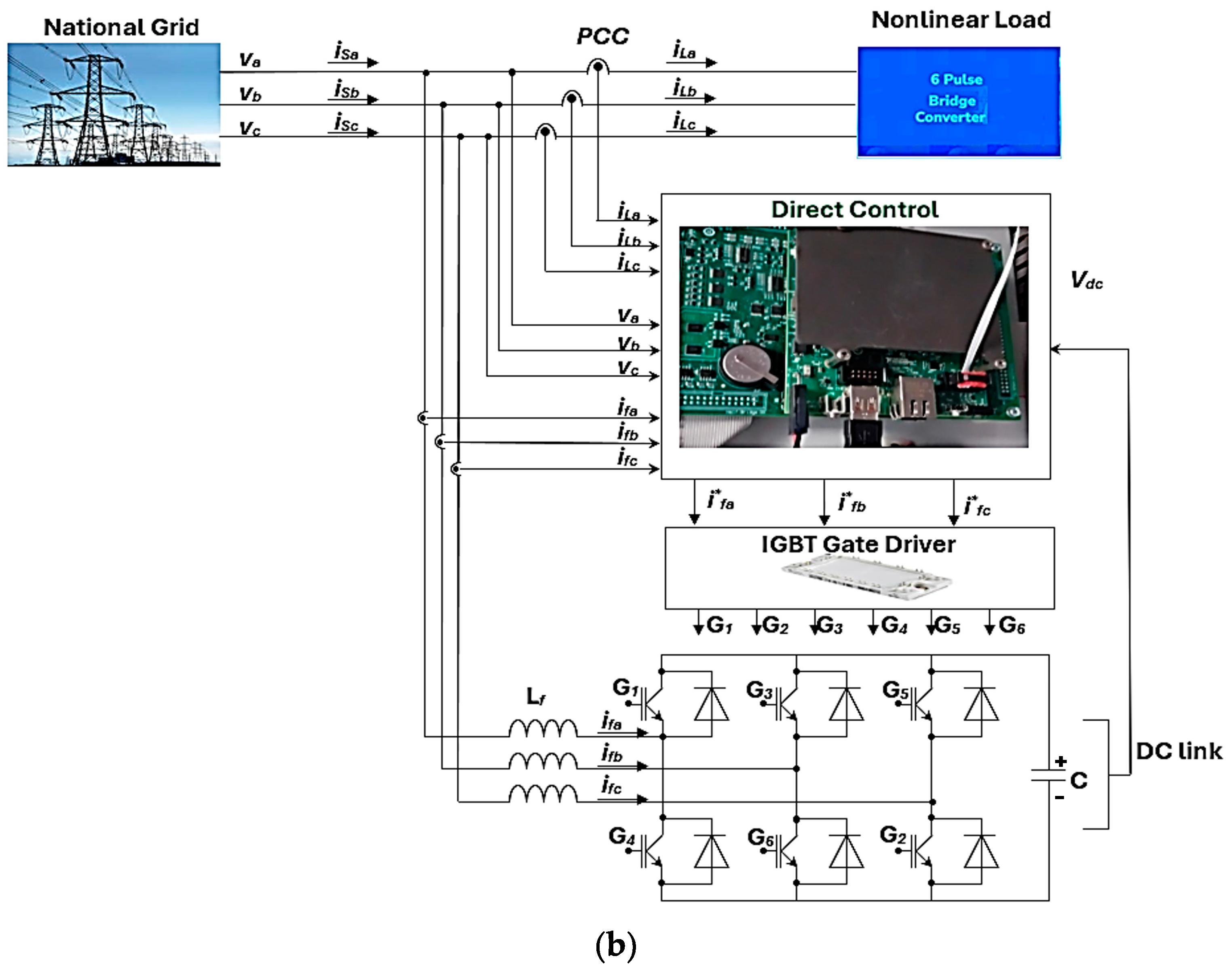

4.2. Direct Control of Active Power Filters

4.2.1. Instantaneous Power (PQ)-Based Control

4.2.2. Synchronous Algorithm (DQ)-Based Control

4.2.3. Maximum Principle (MAX)-Based Control

4.2.4. Principle of Current Synchronization with the Voltage Positive-Sequence Component (SEC-POZ) Based Control

4.2.5. Band-Stop Filter (Notch Filter)-Based Control

4.2.6. Direct Control: Low-Pass Filter (LPF)-Based Control

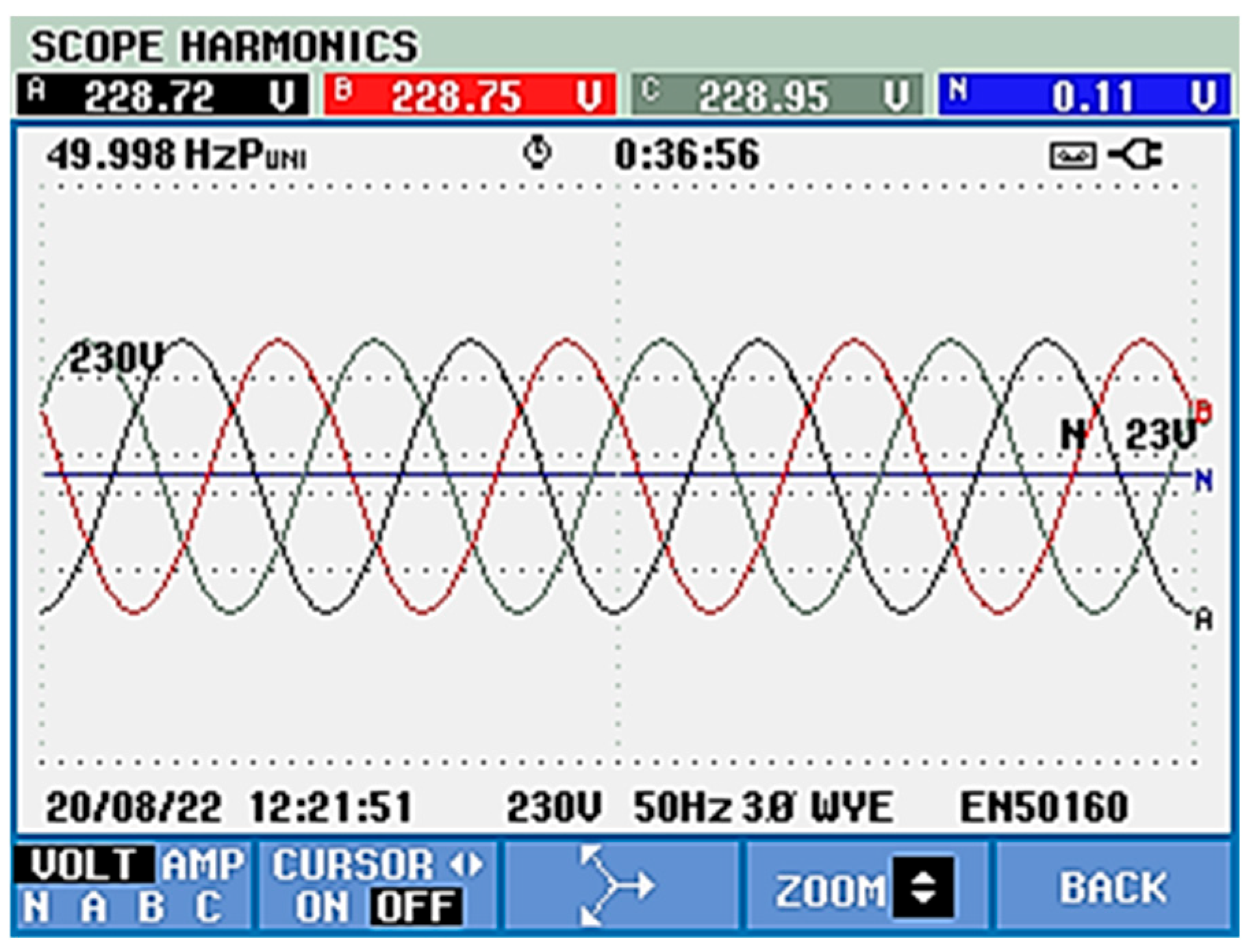

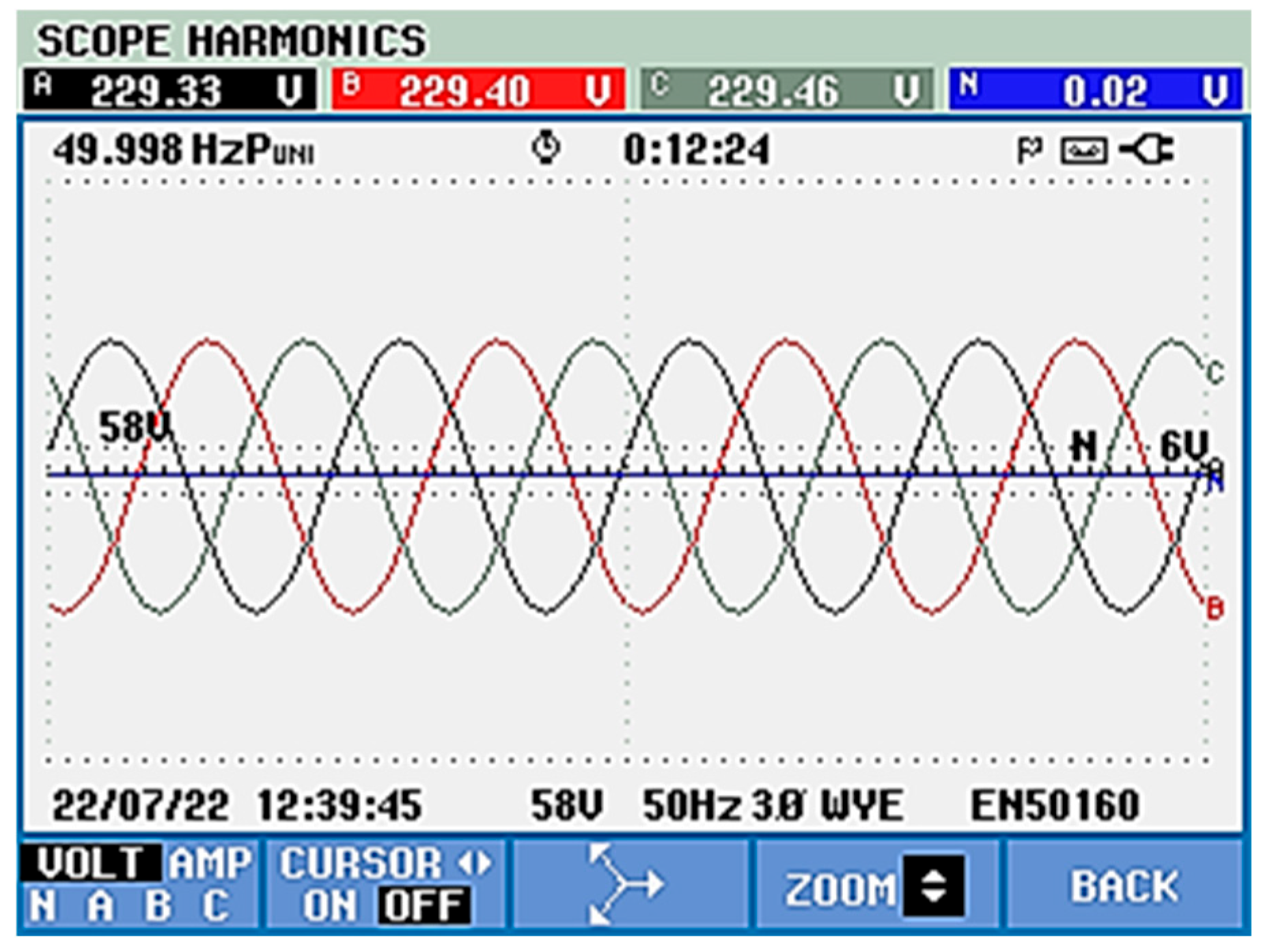

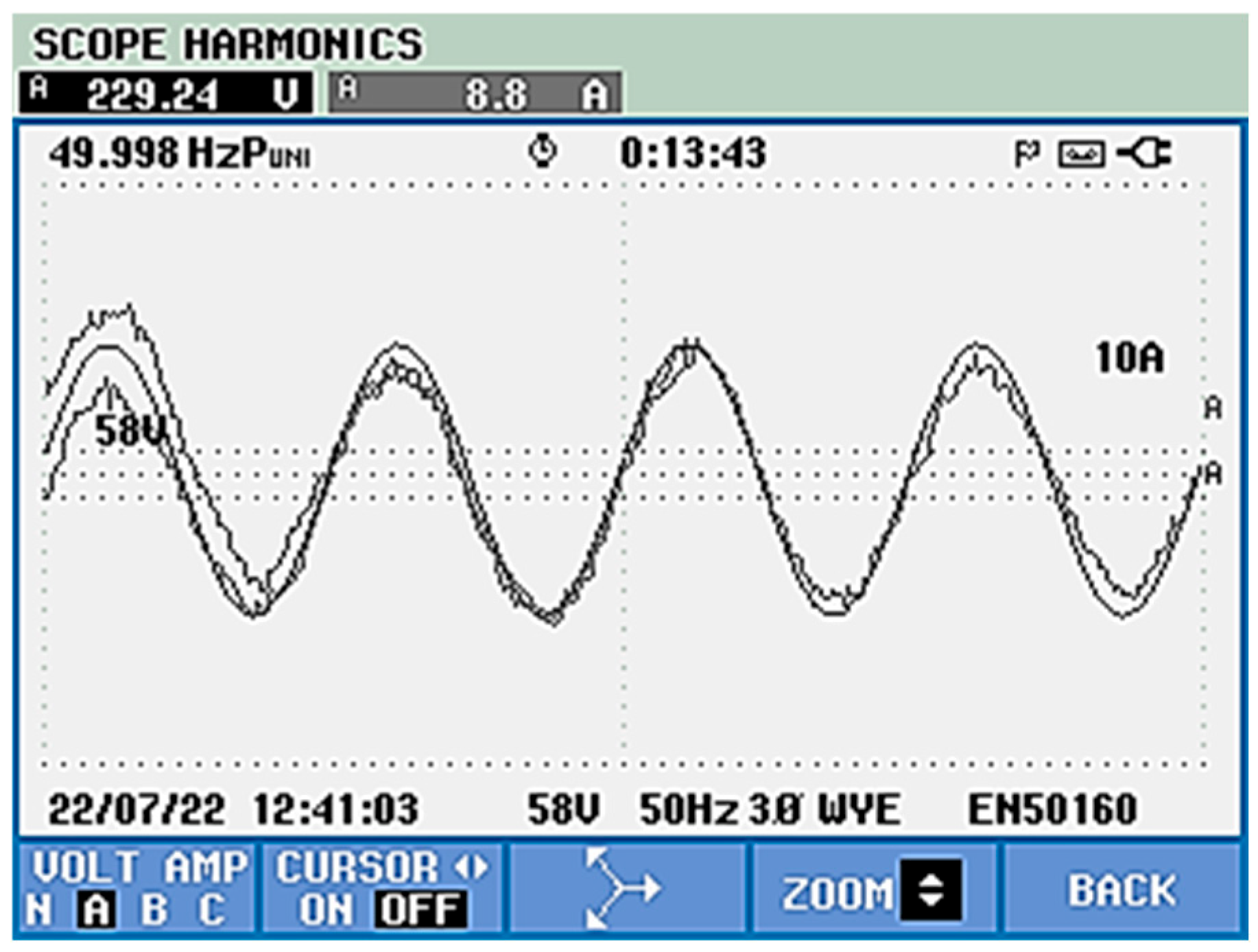

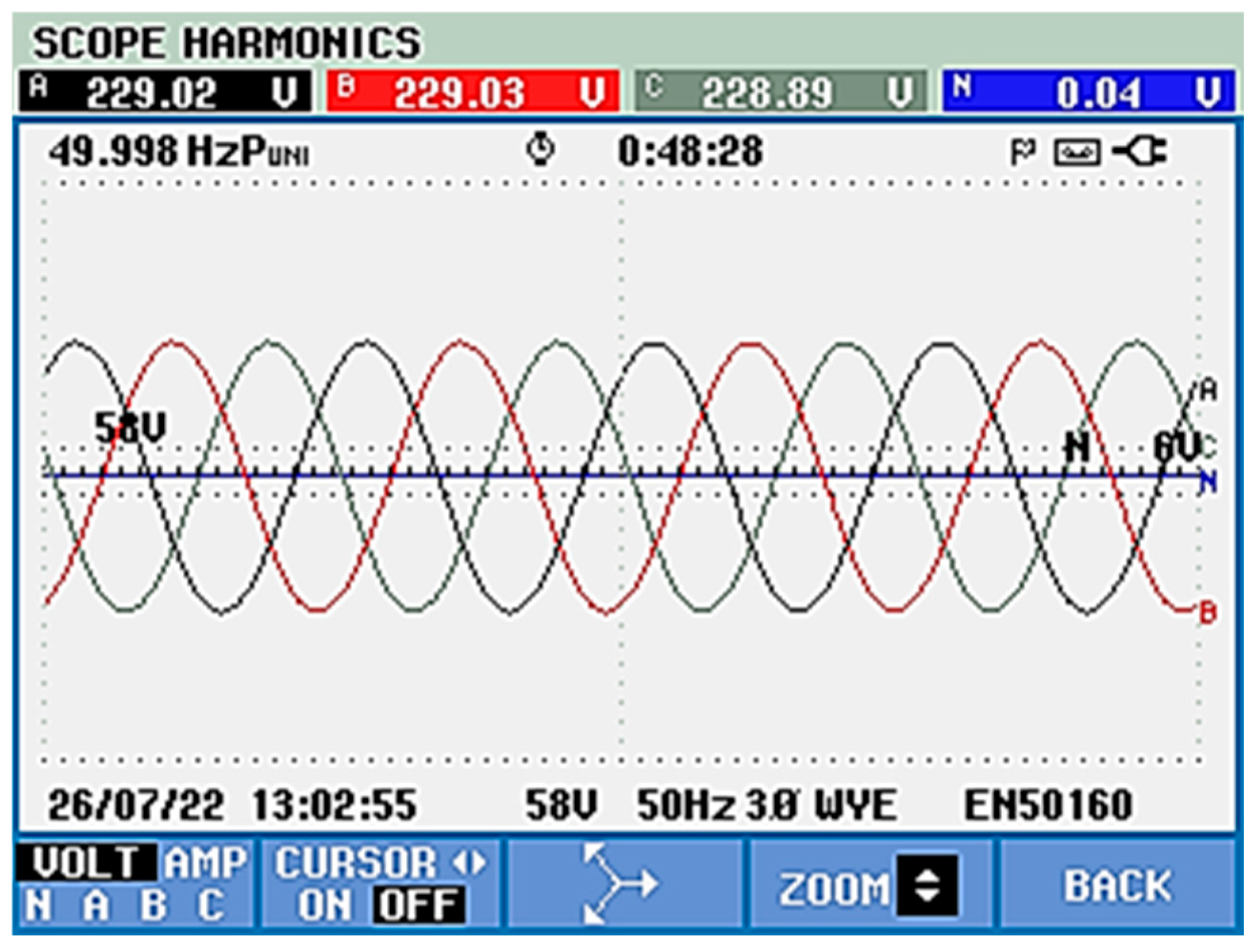

5. Experimental Results

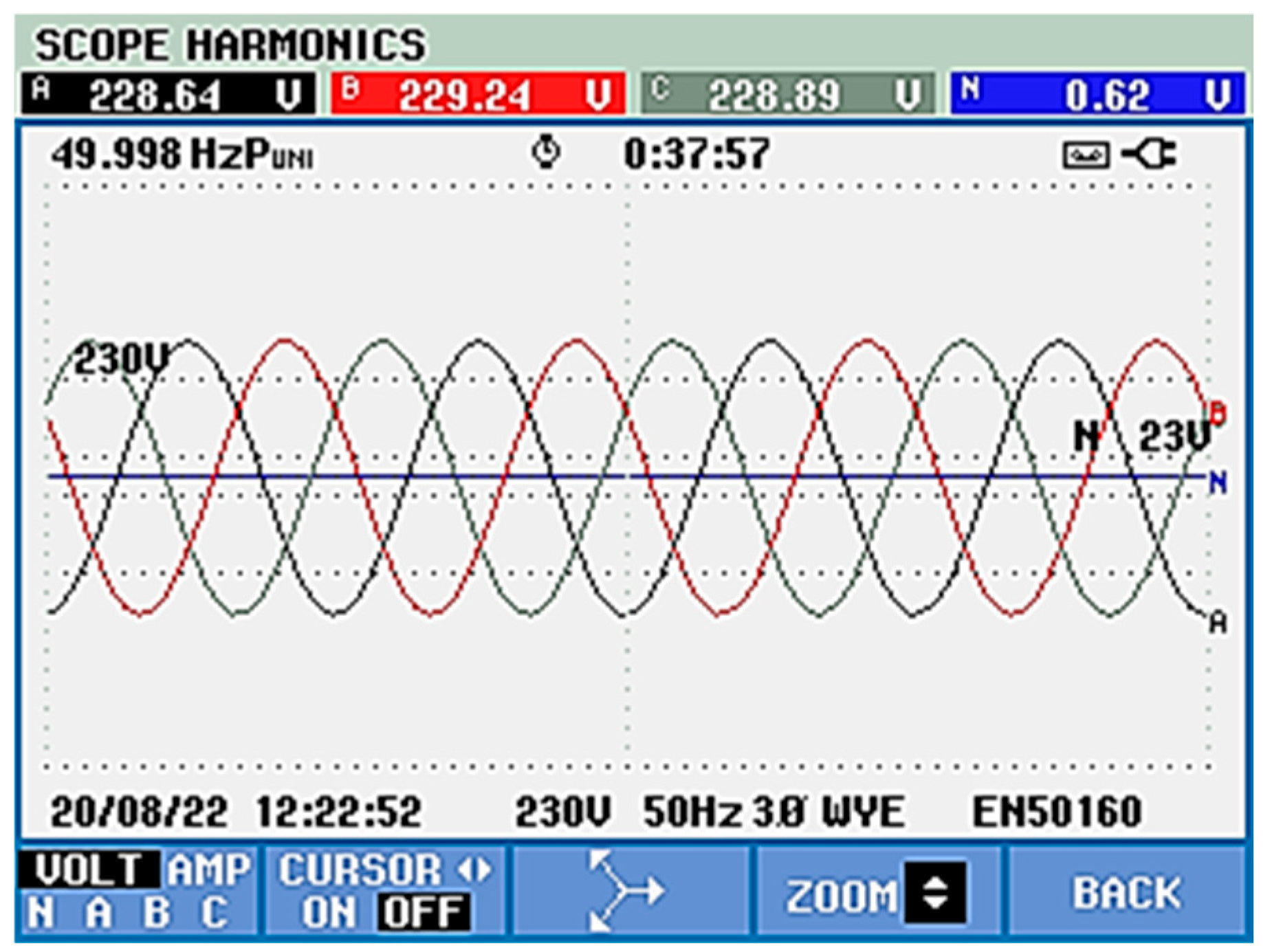

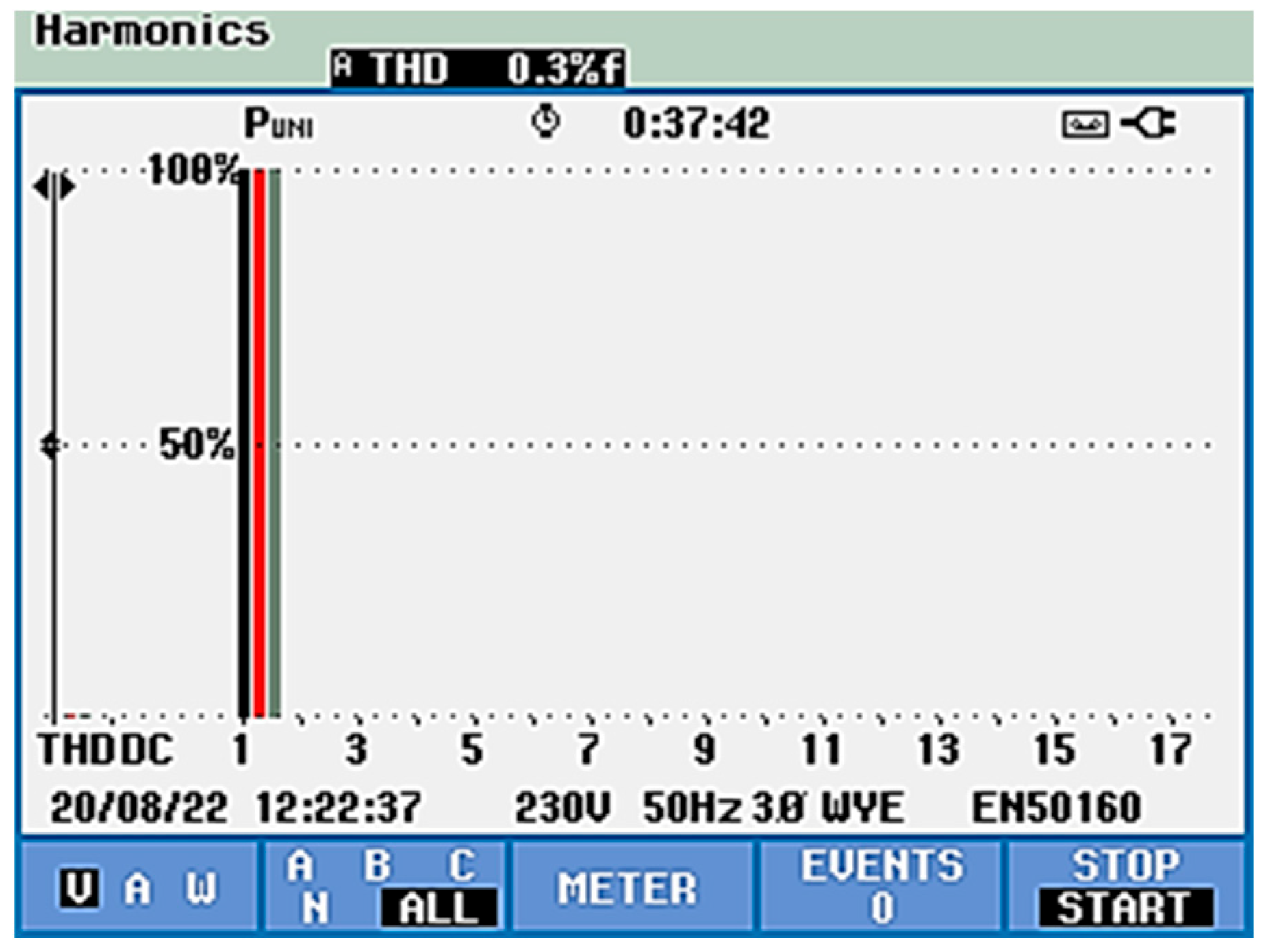

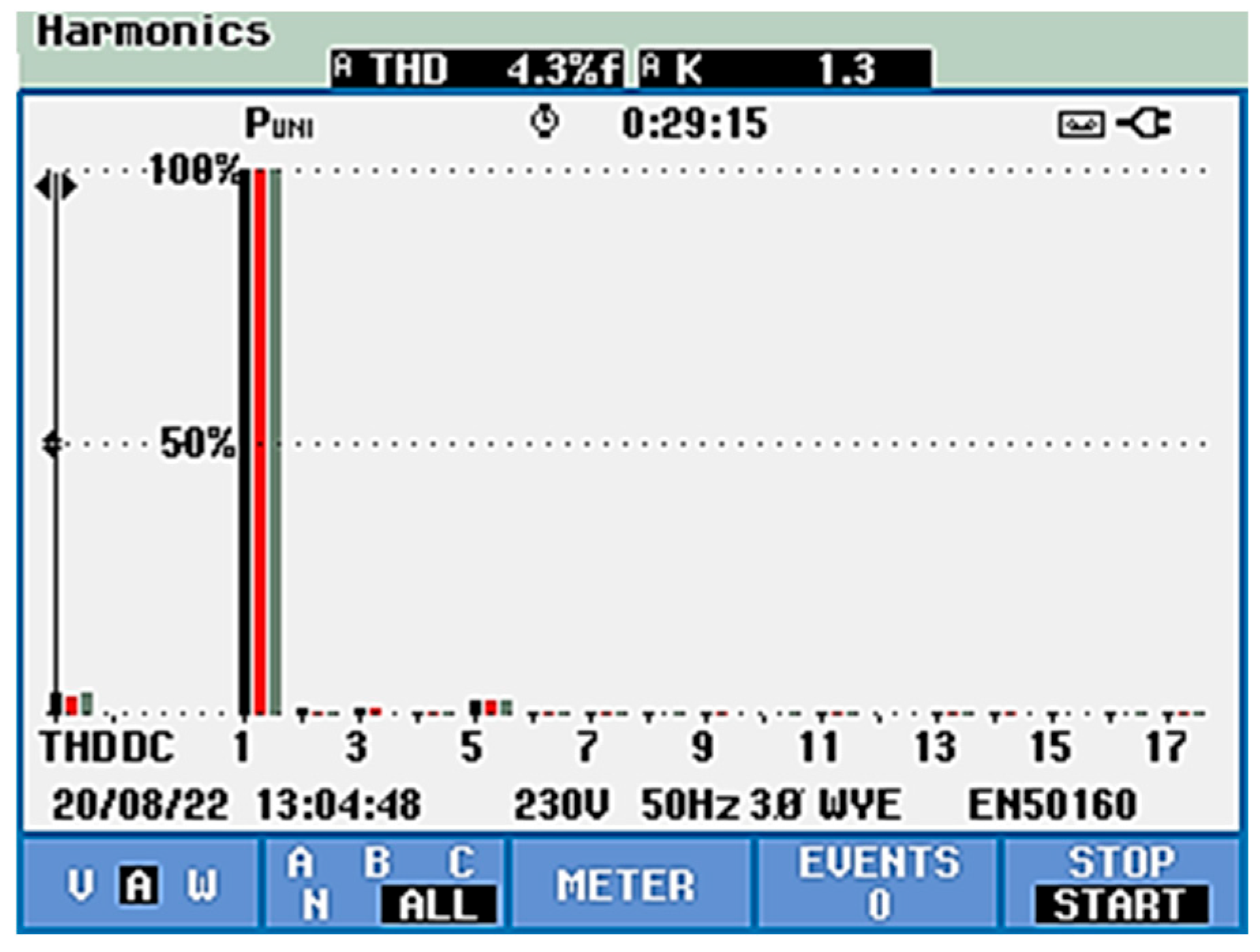

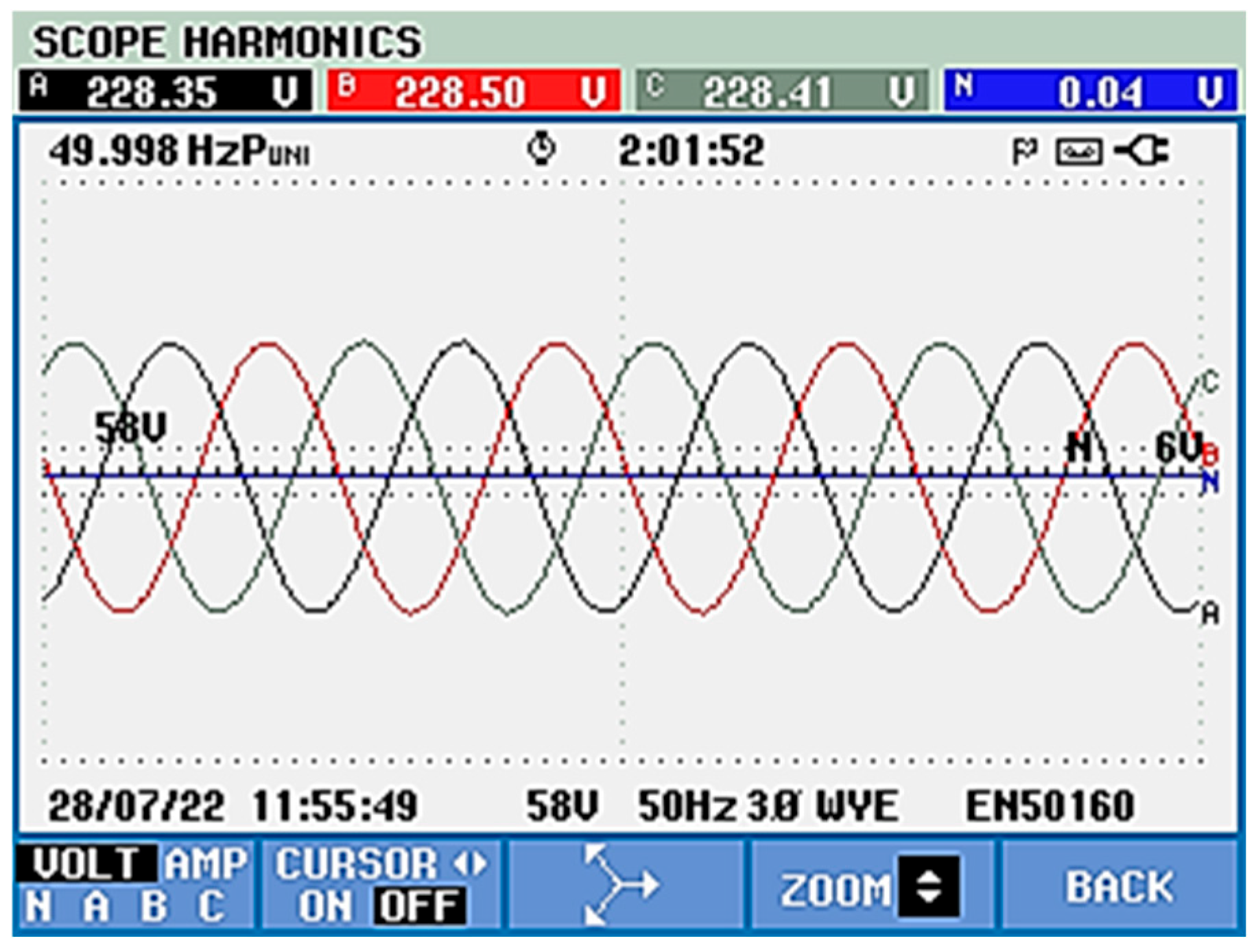

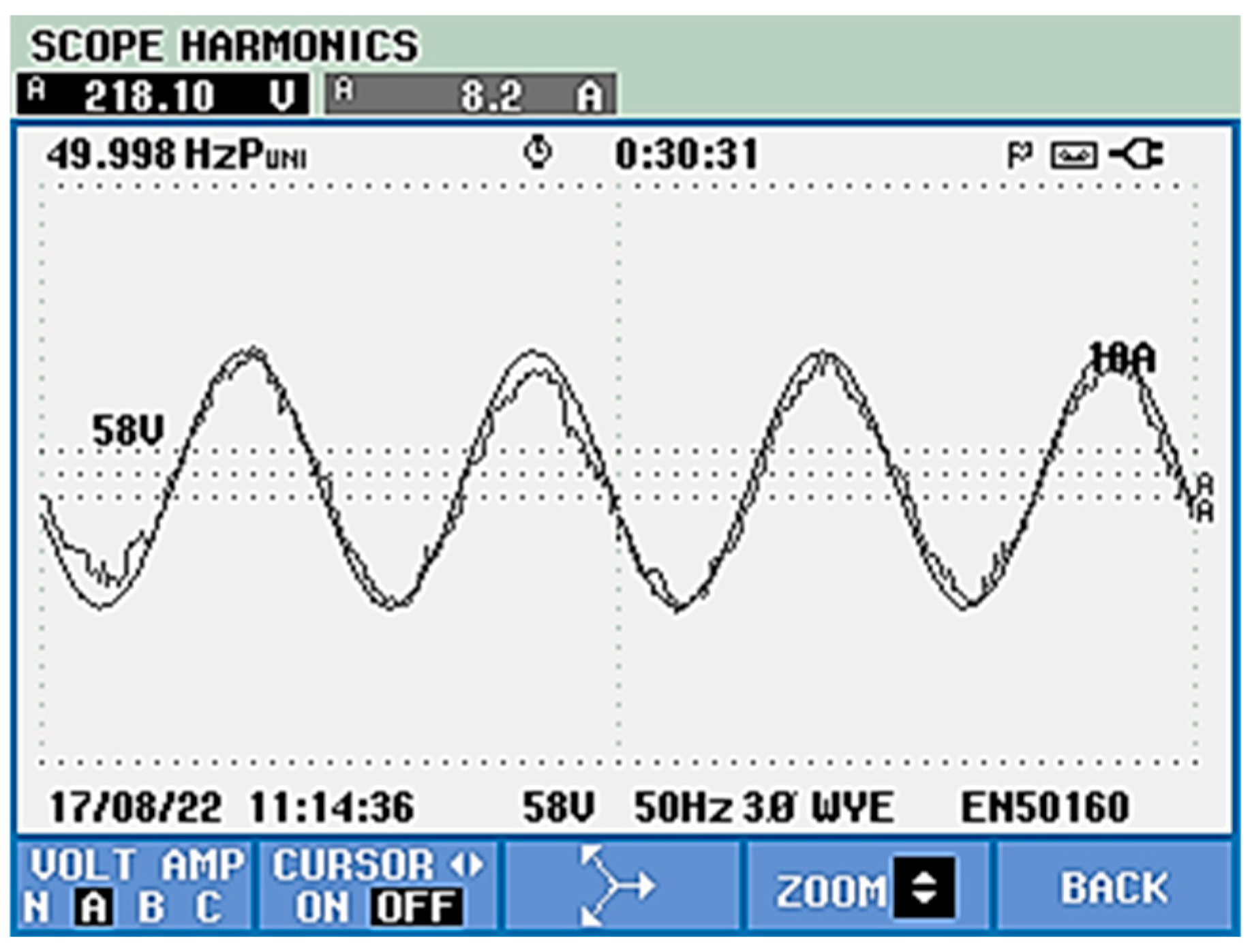

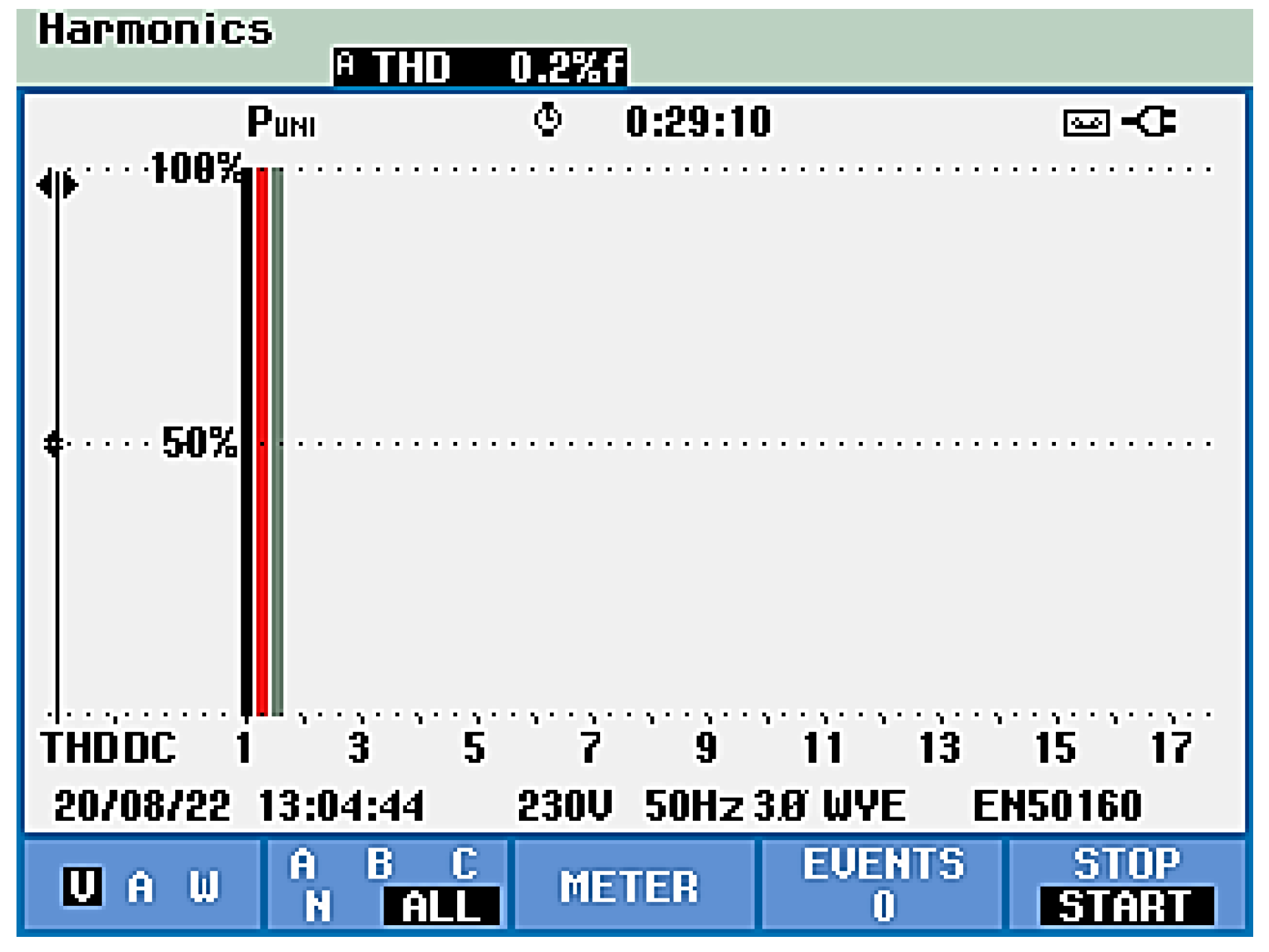

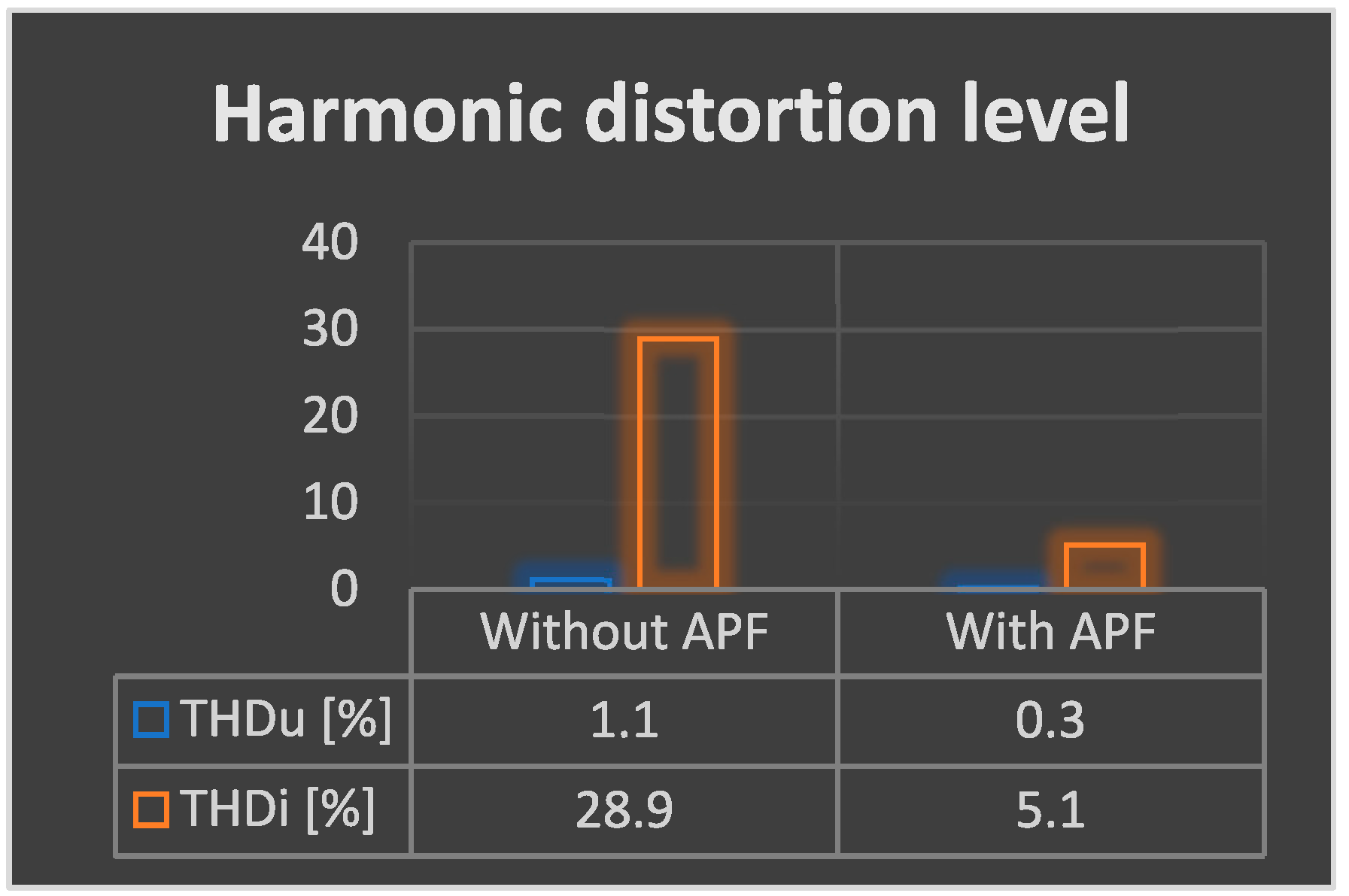

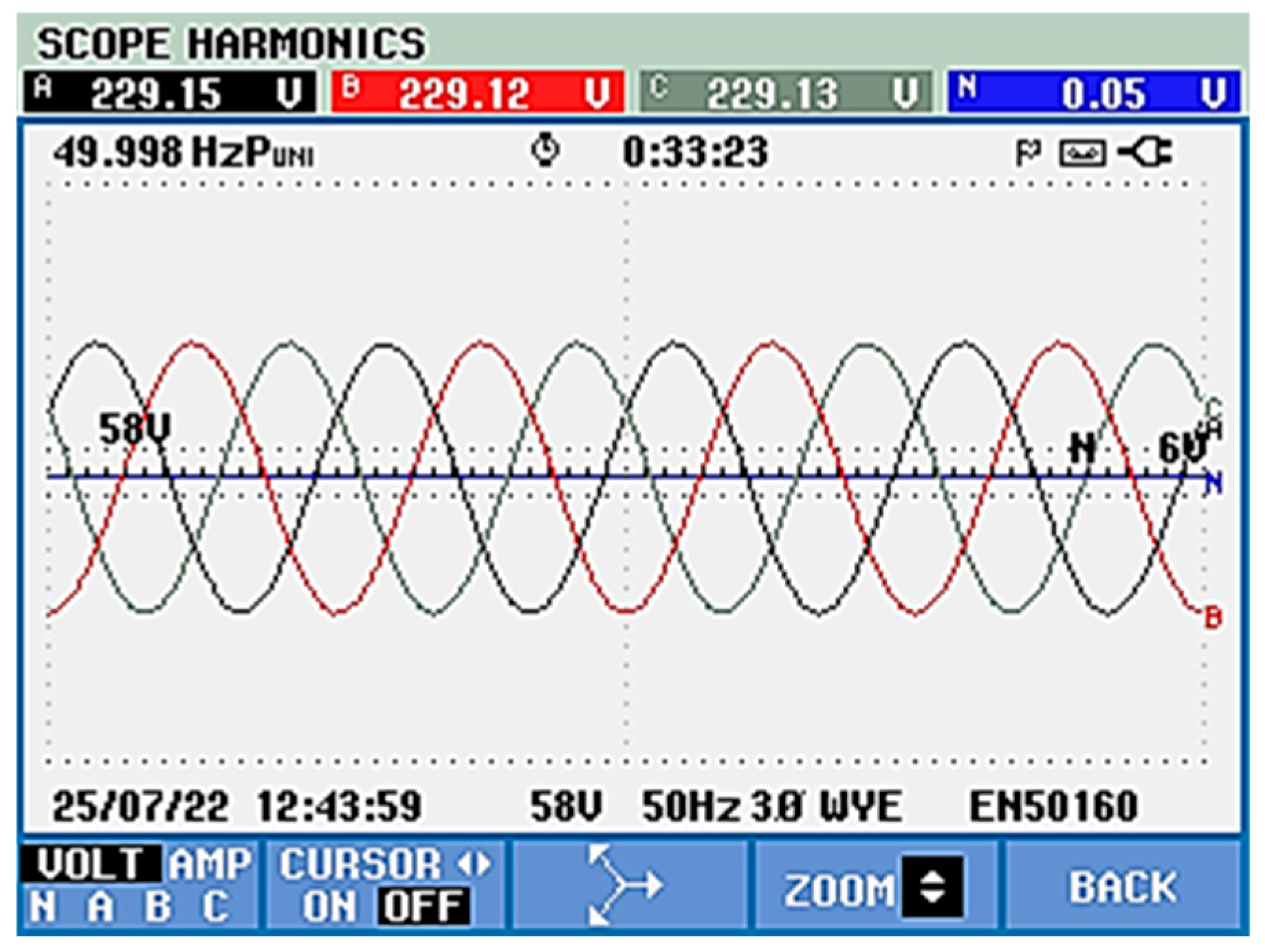

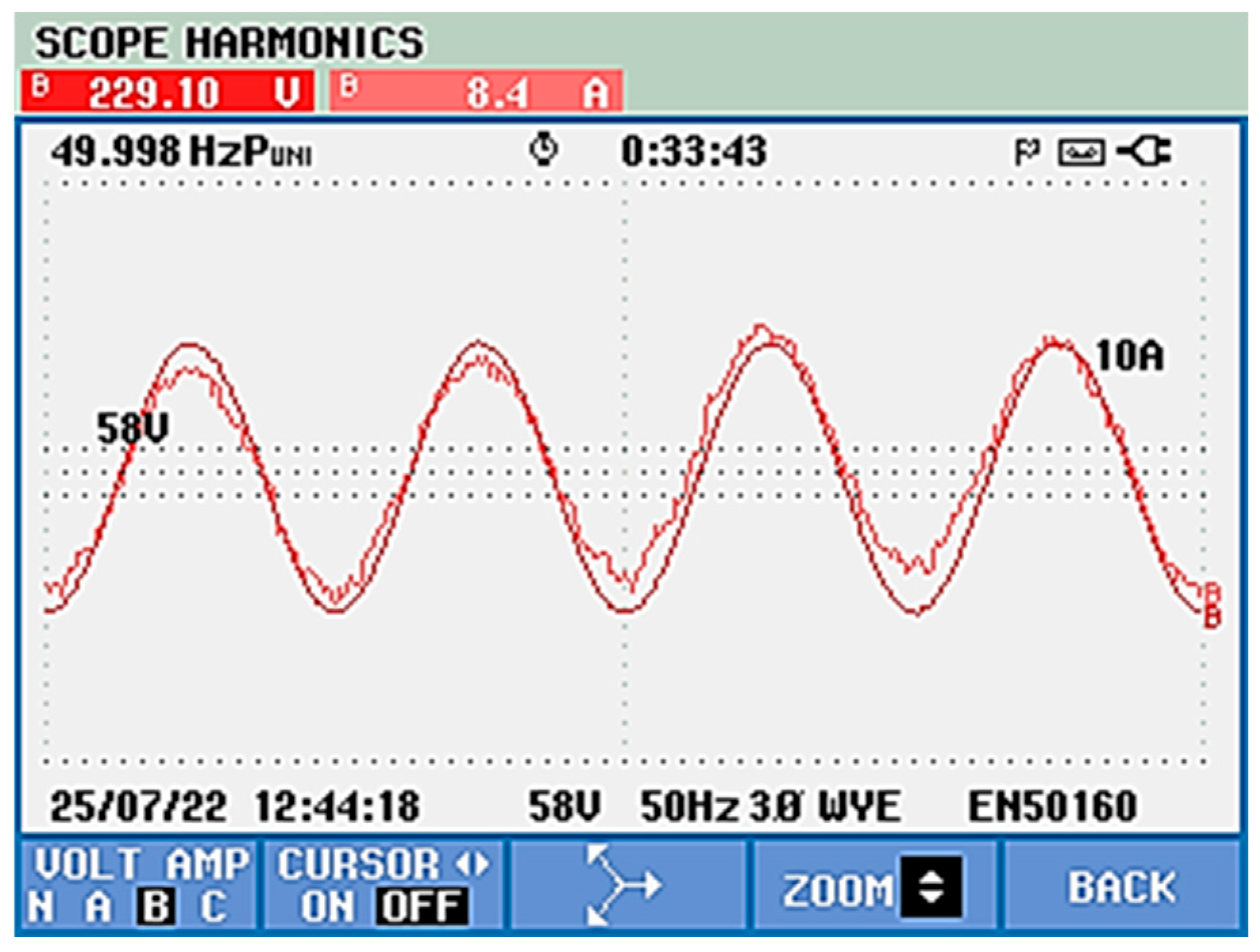

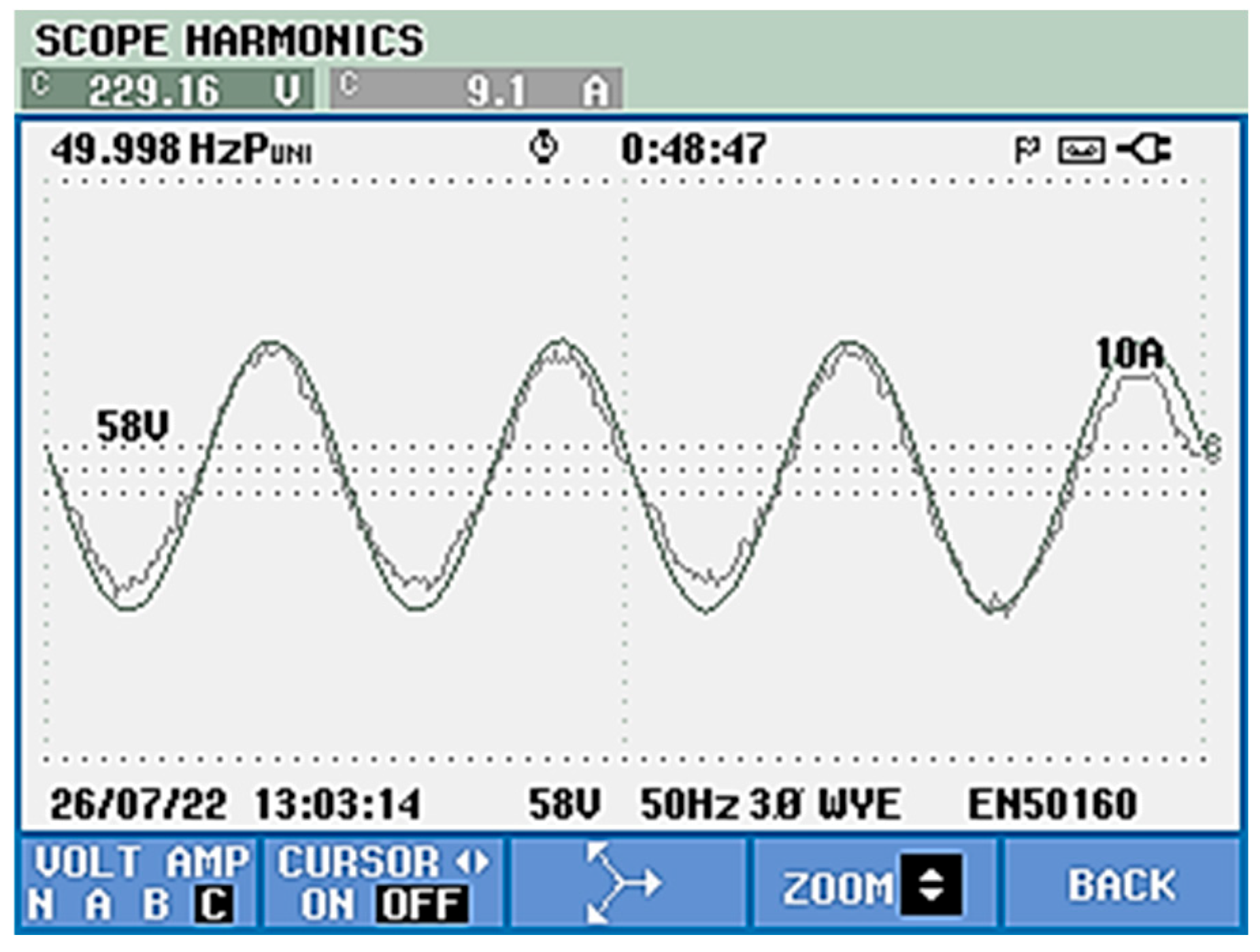

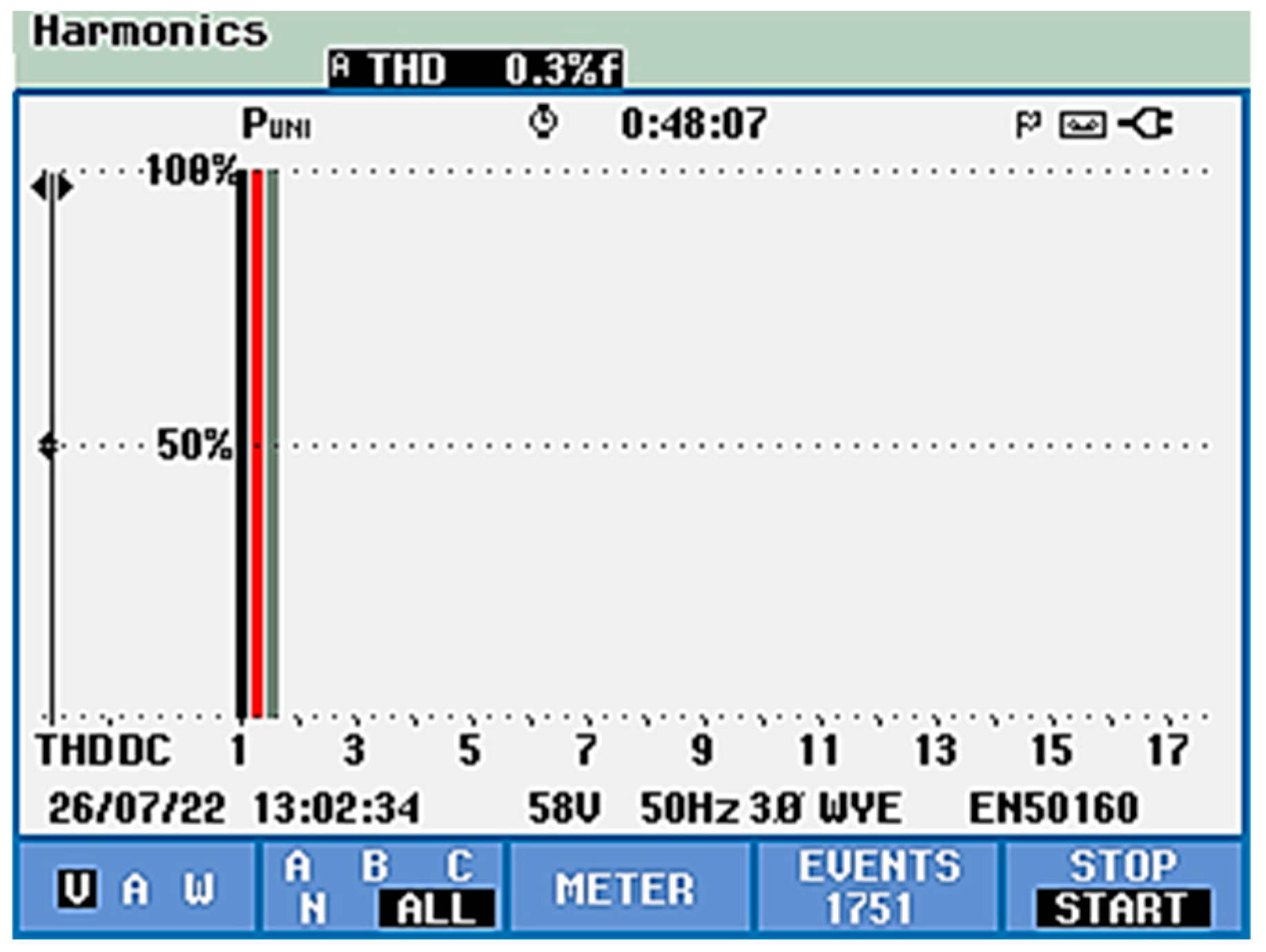

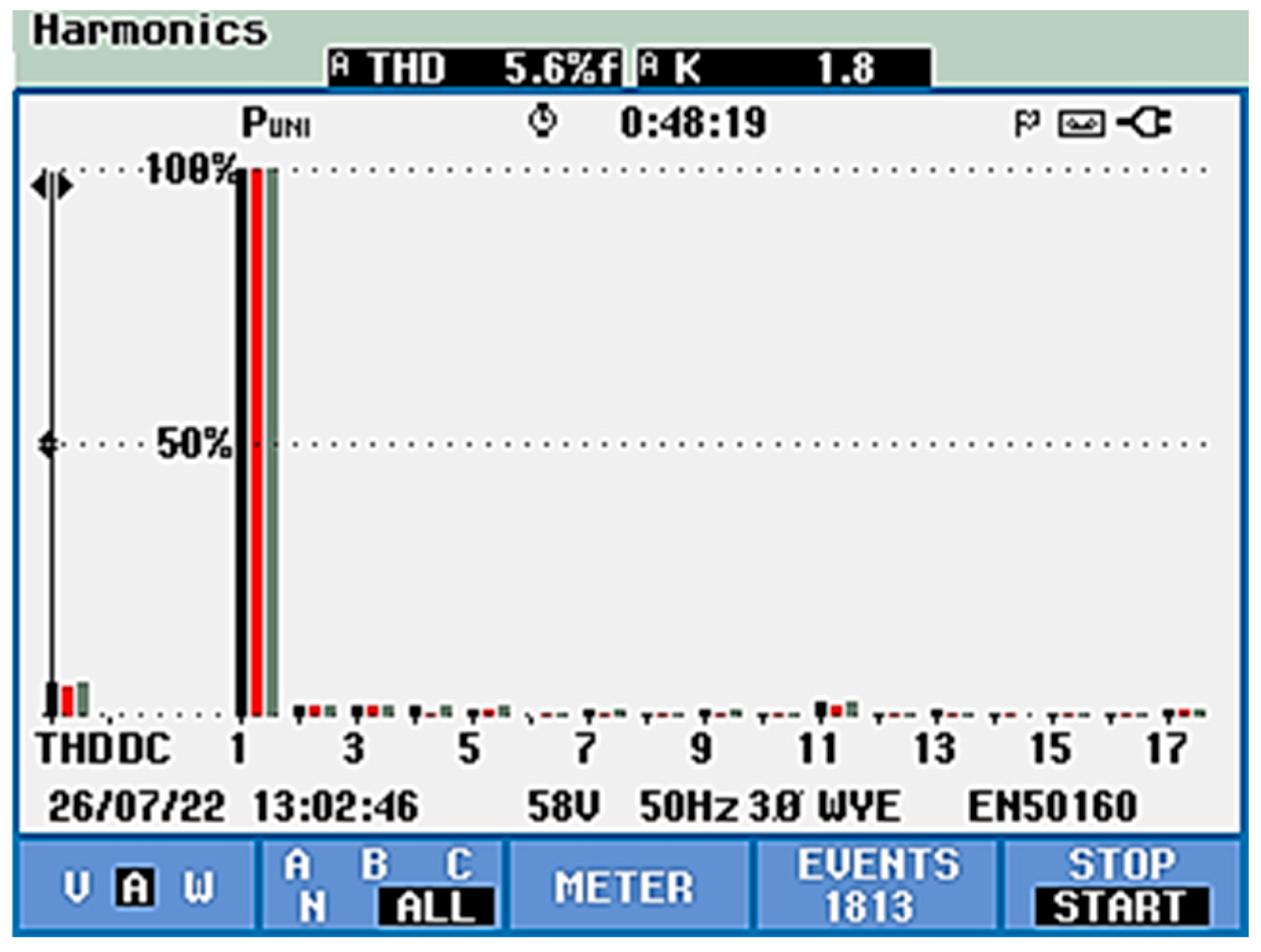

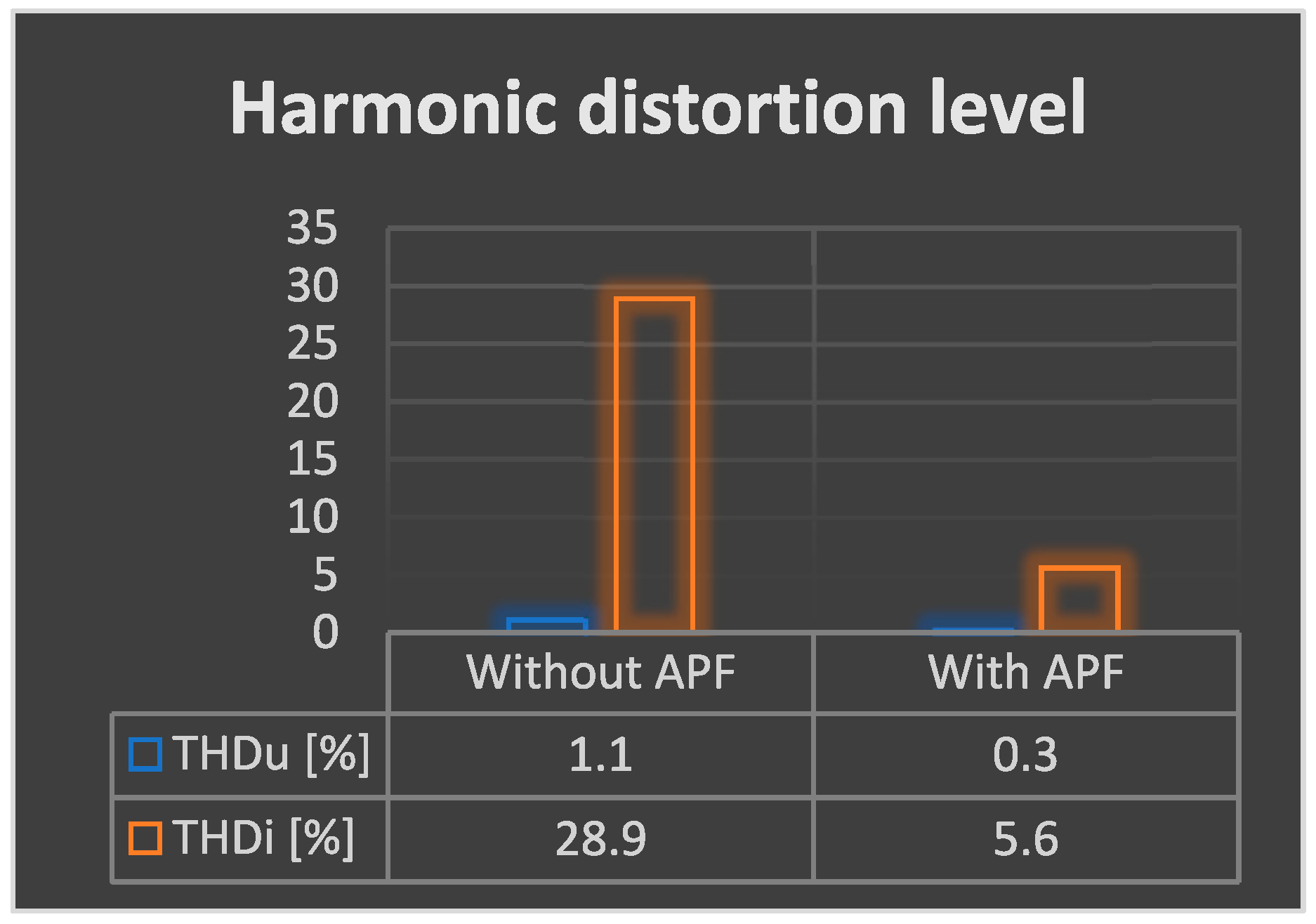

5.1. Indirect Control [53]

- a.

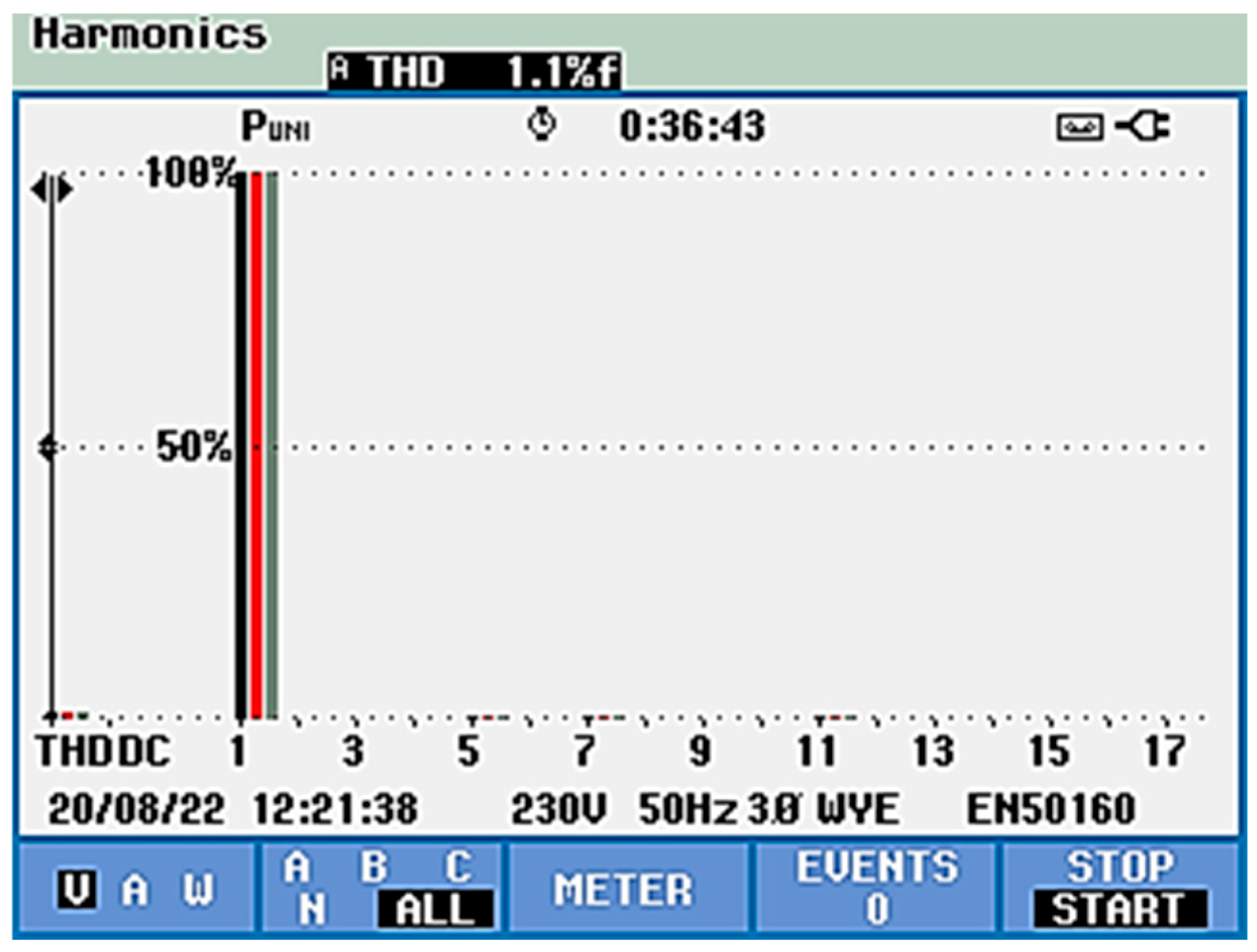

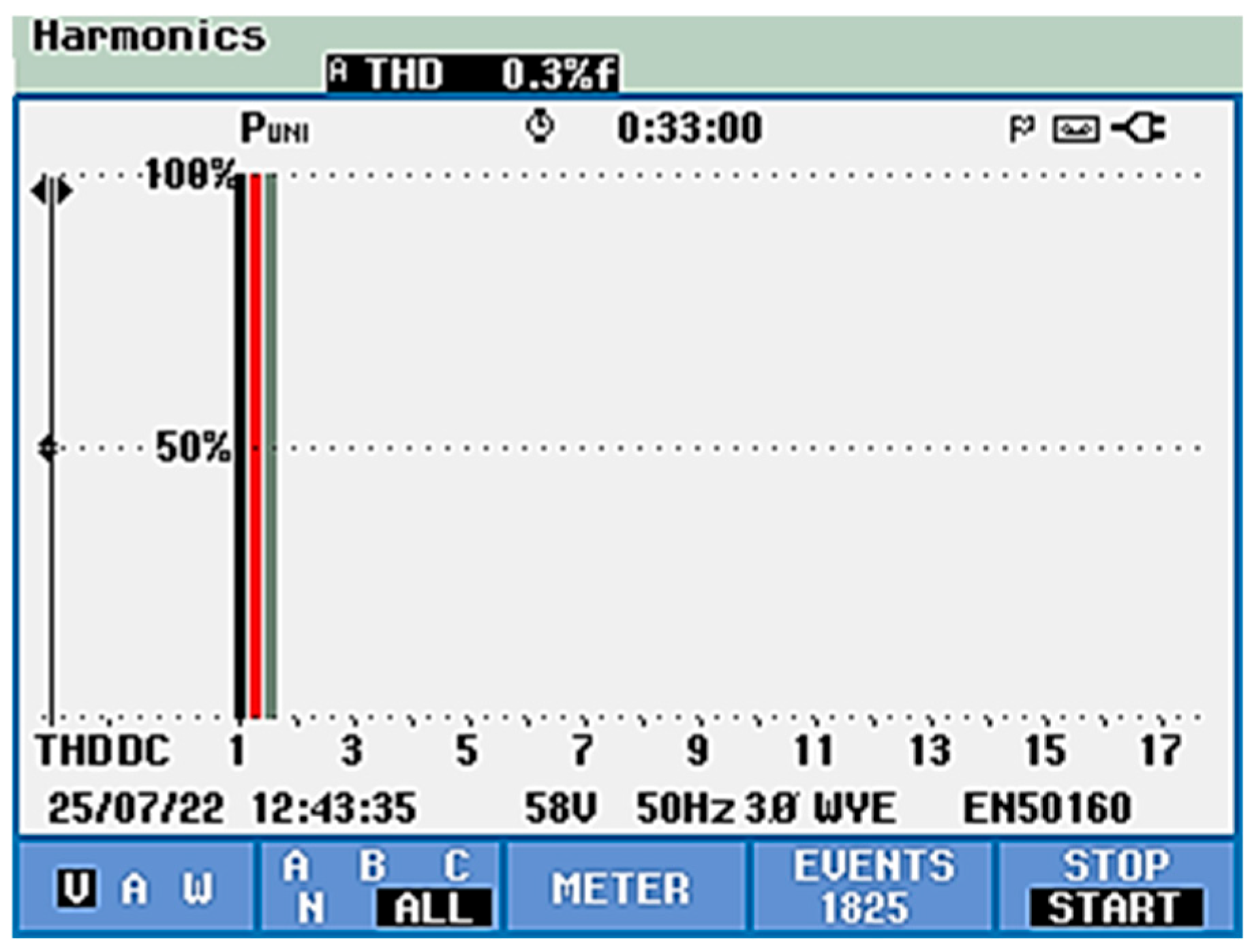

- Experimental Results Without the APF Connected

- b.

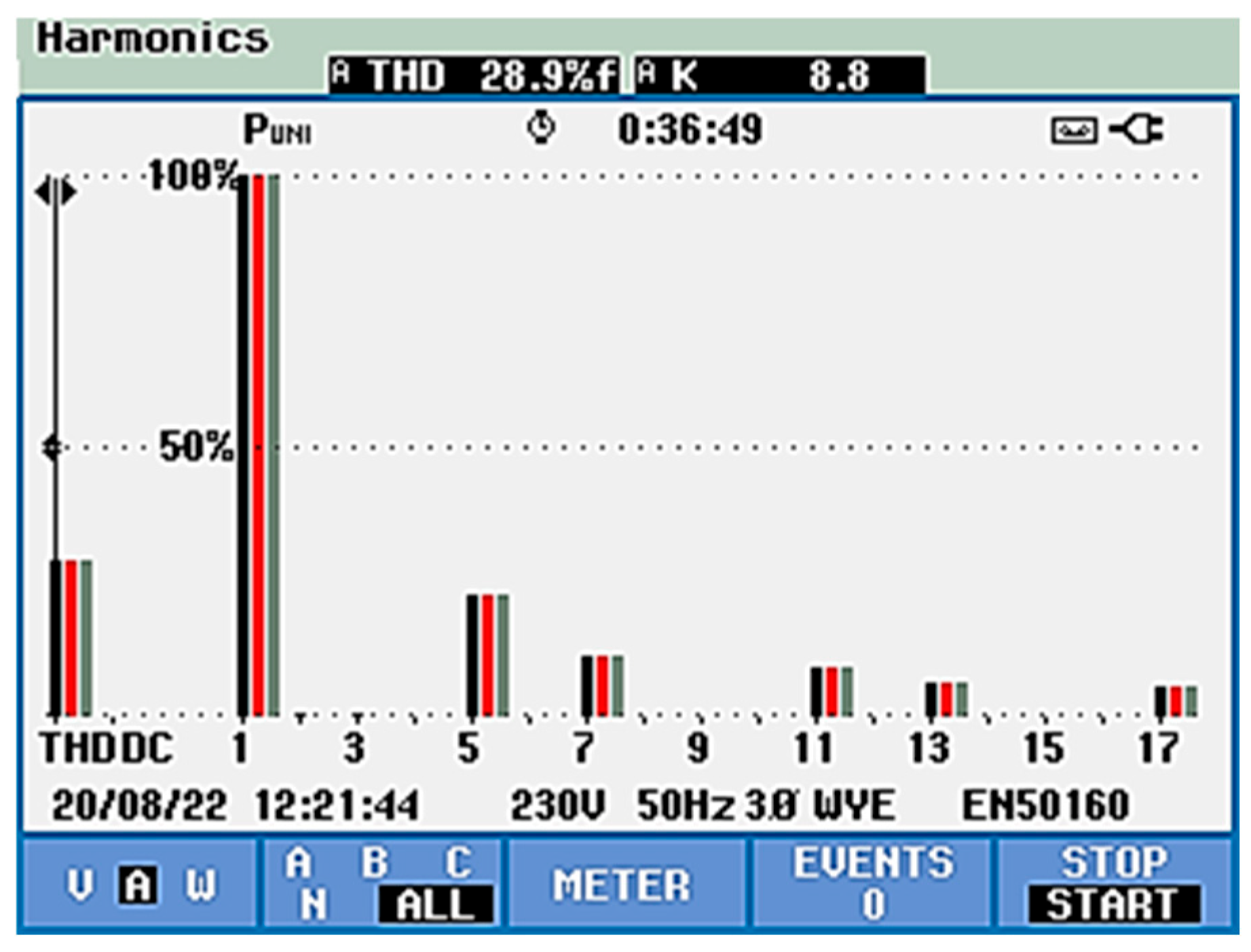

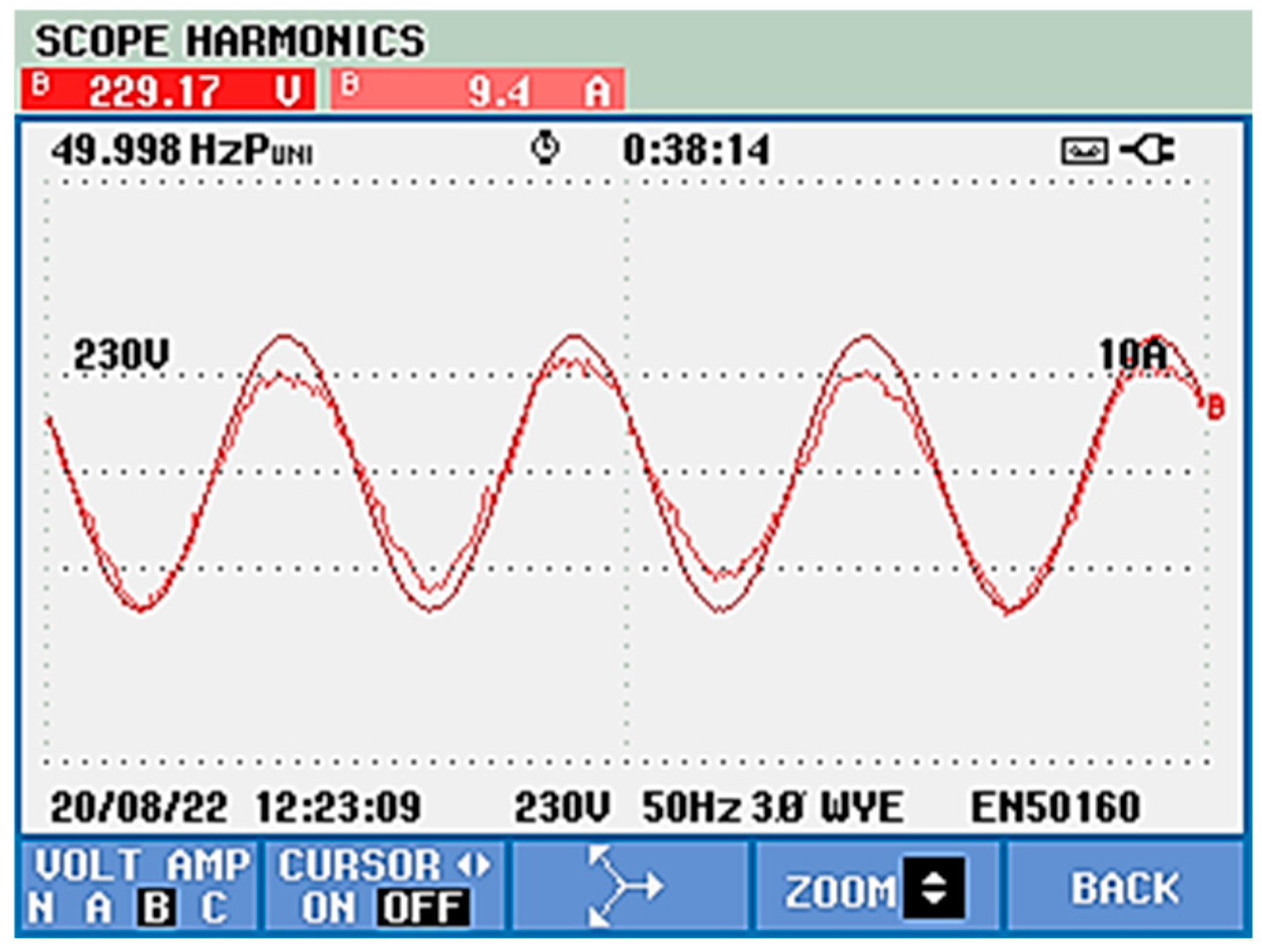

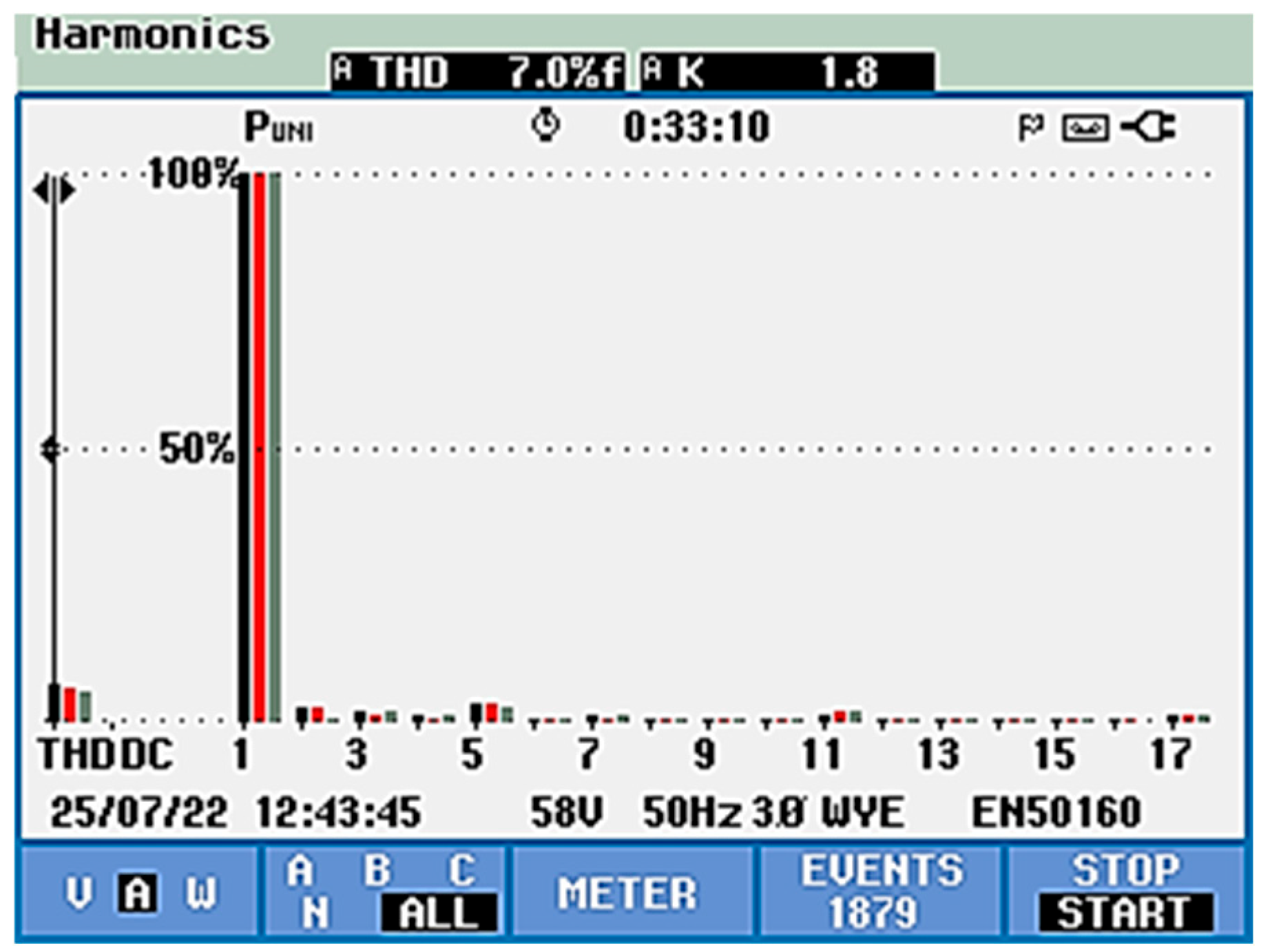

- Experimental Results with the APF Connected

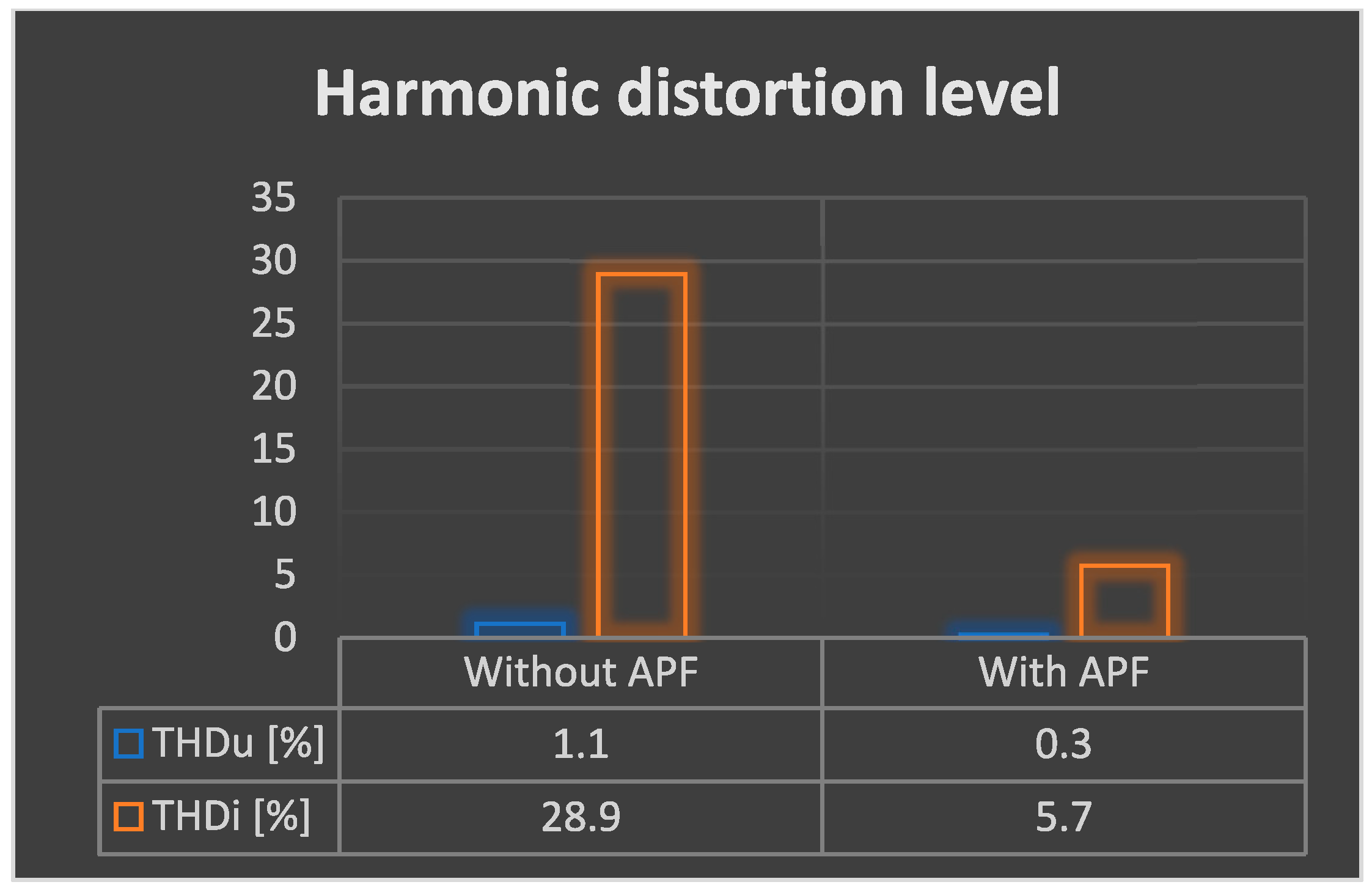

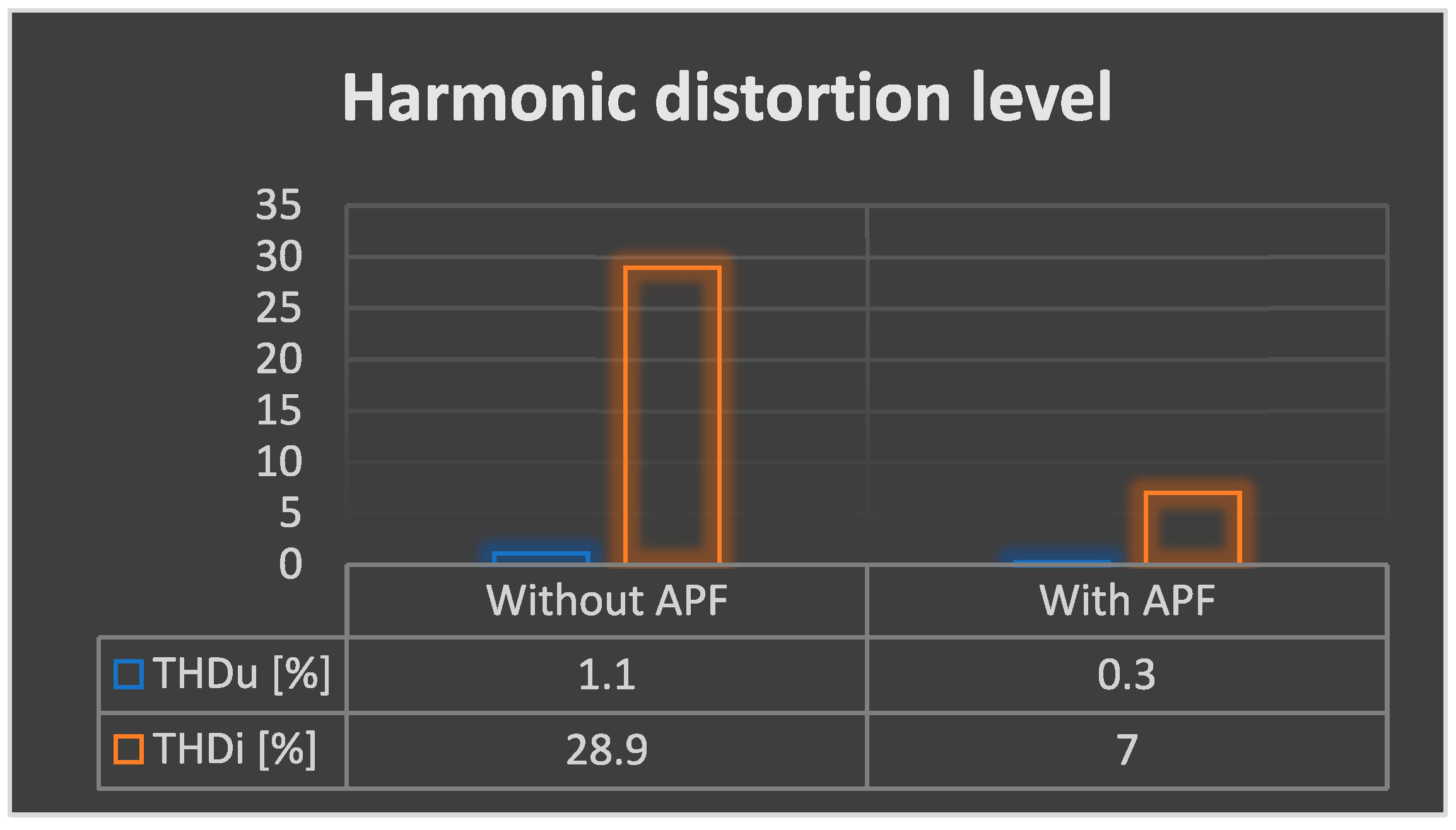

- THDu (phase voltage) decreased from 1.1% to 0.3%

- THDi (phase current) decreased from 28.9% to 4.3%

5.2. Direct Control

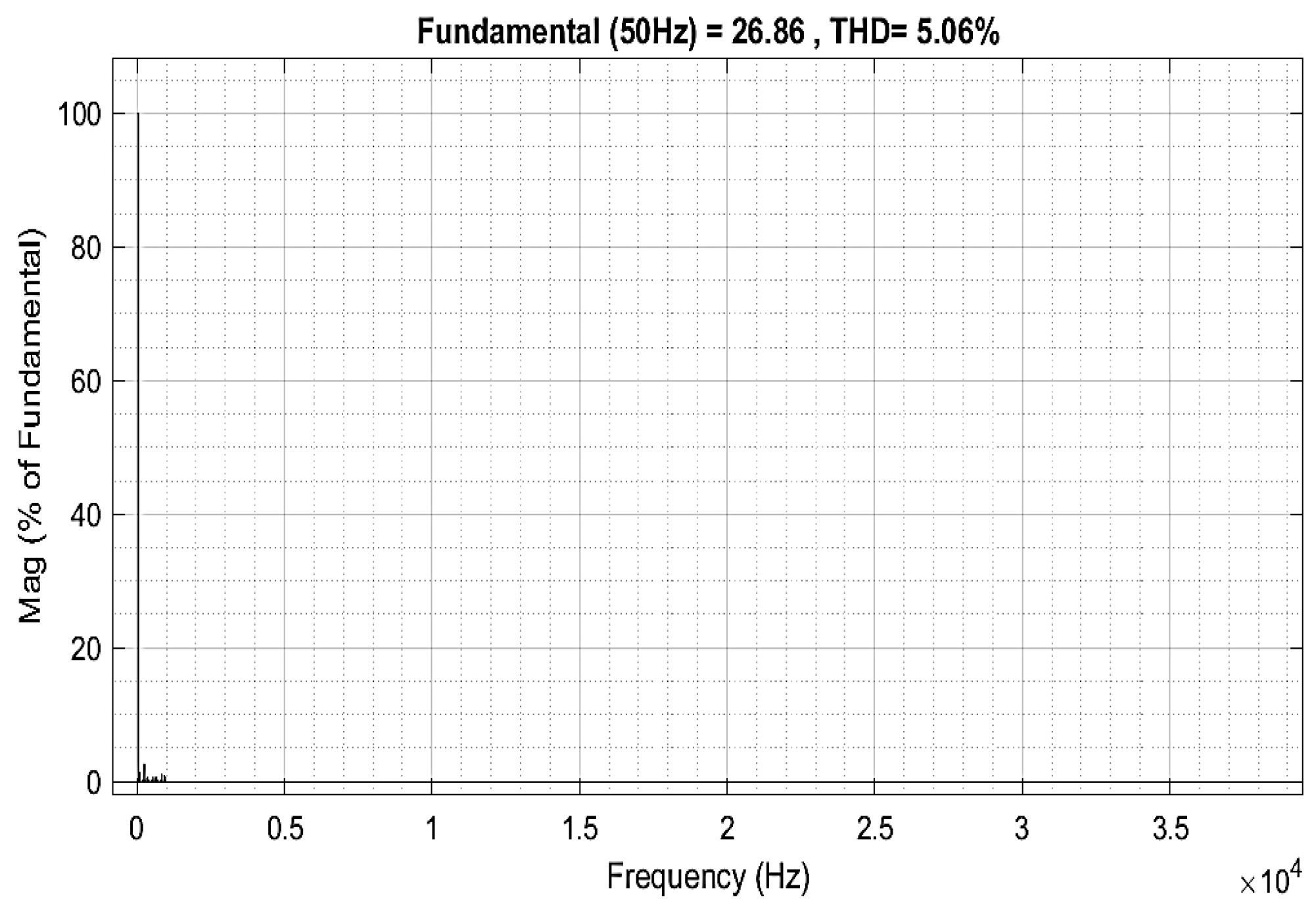

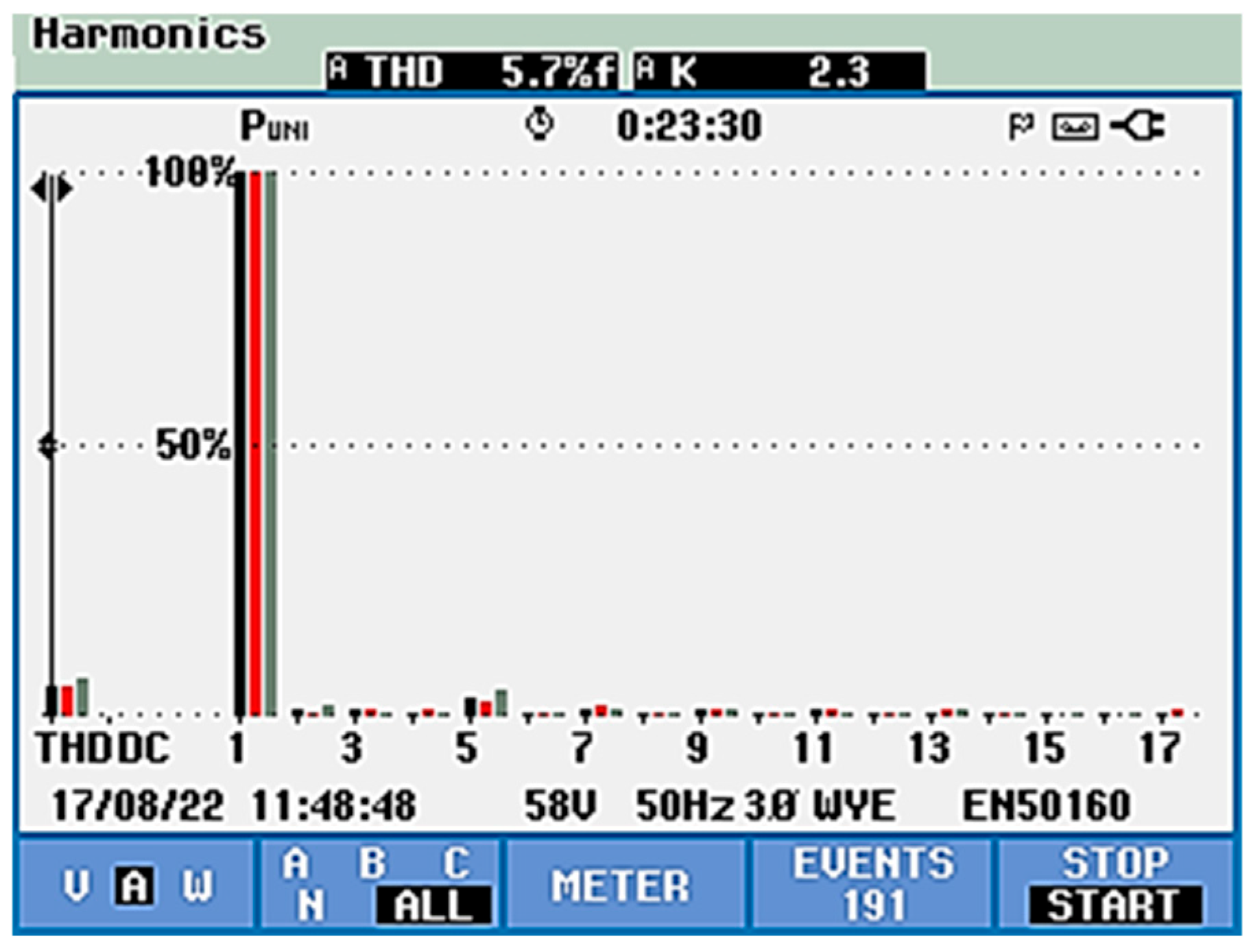

5.2.1. PQ Control

- Phase voltage THDu: reduced from 1.1% to 0.3%

- Phase current THDi: reduced from 28.9% to 5.7%

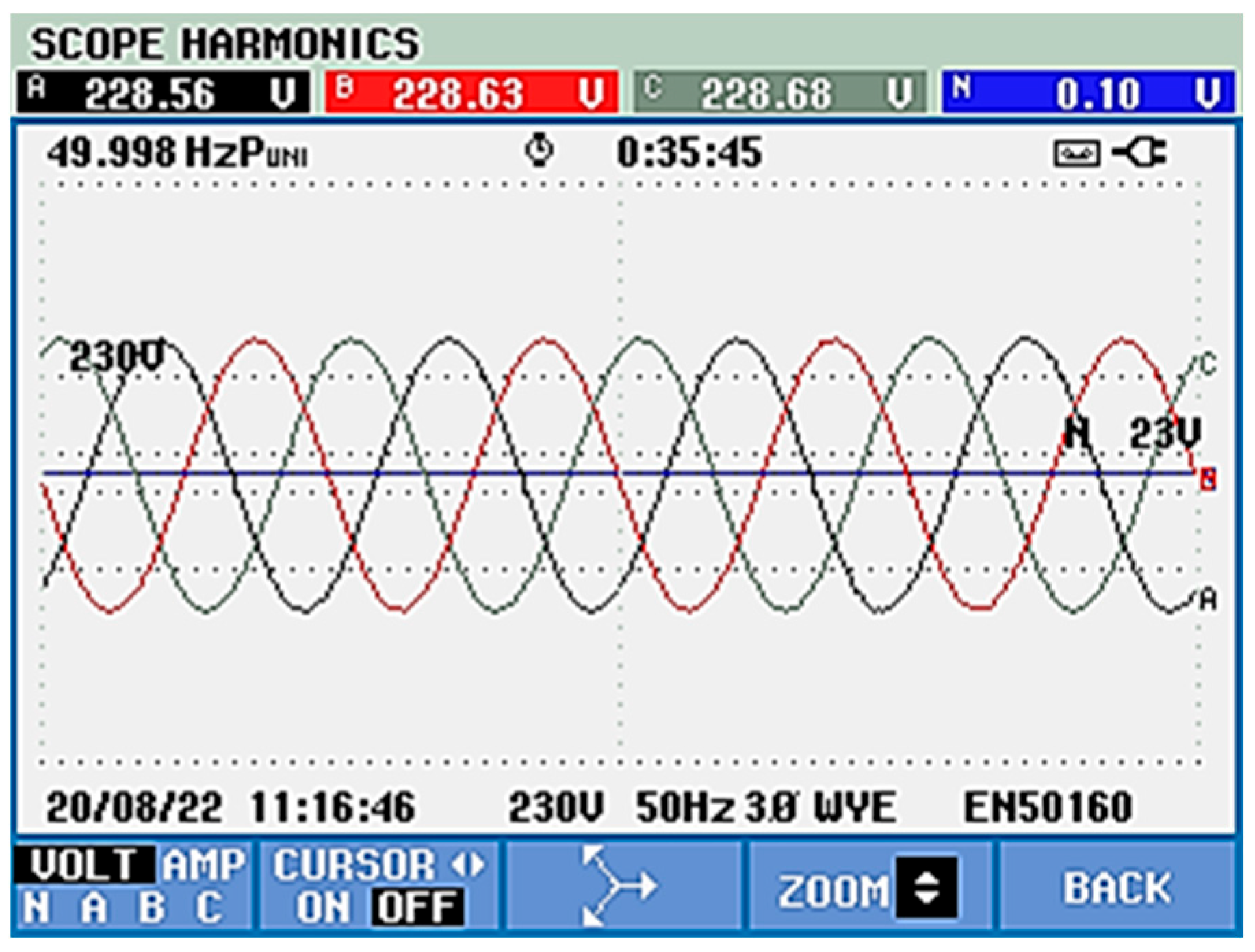

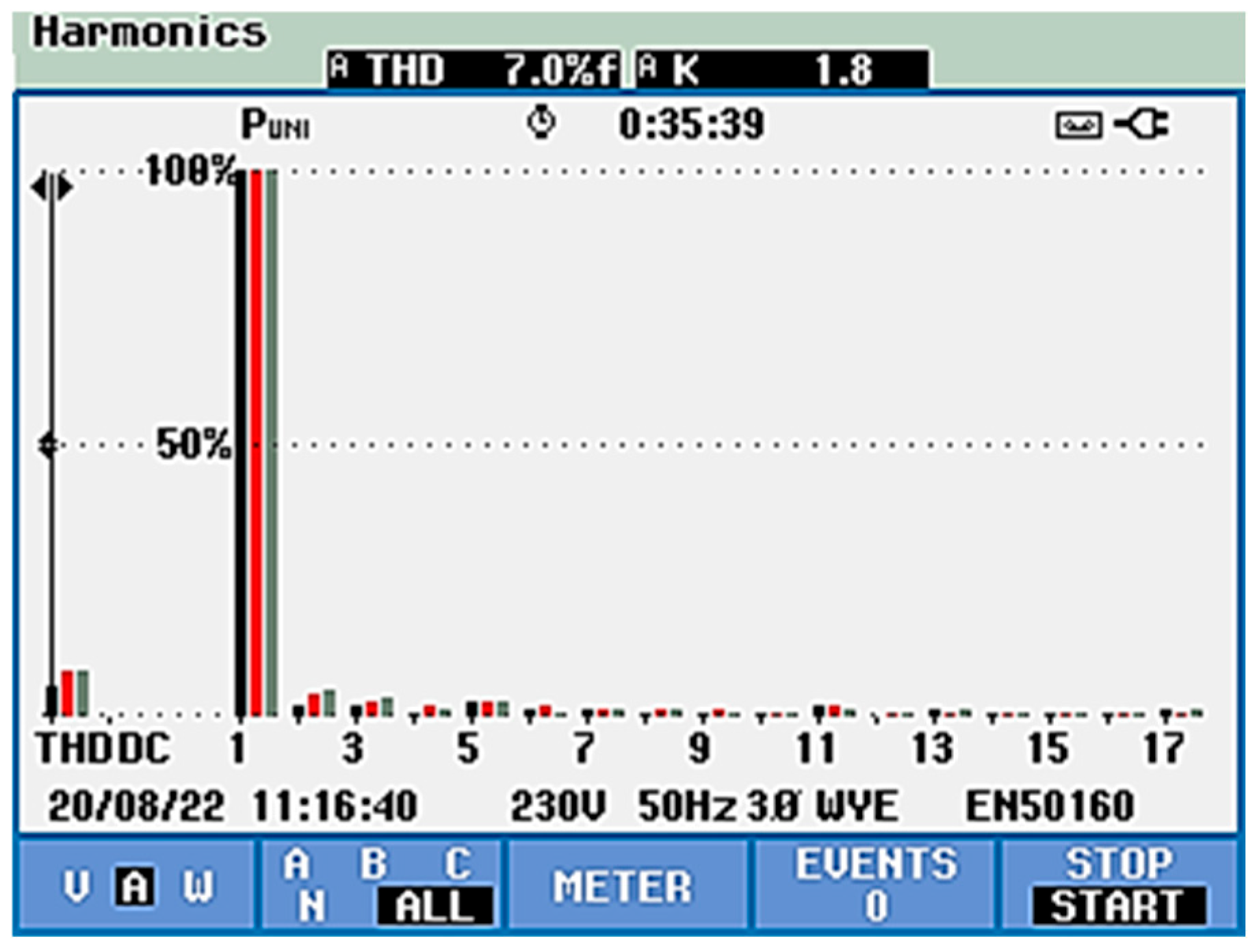

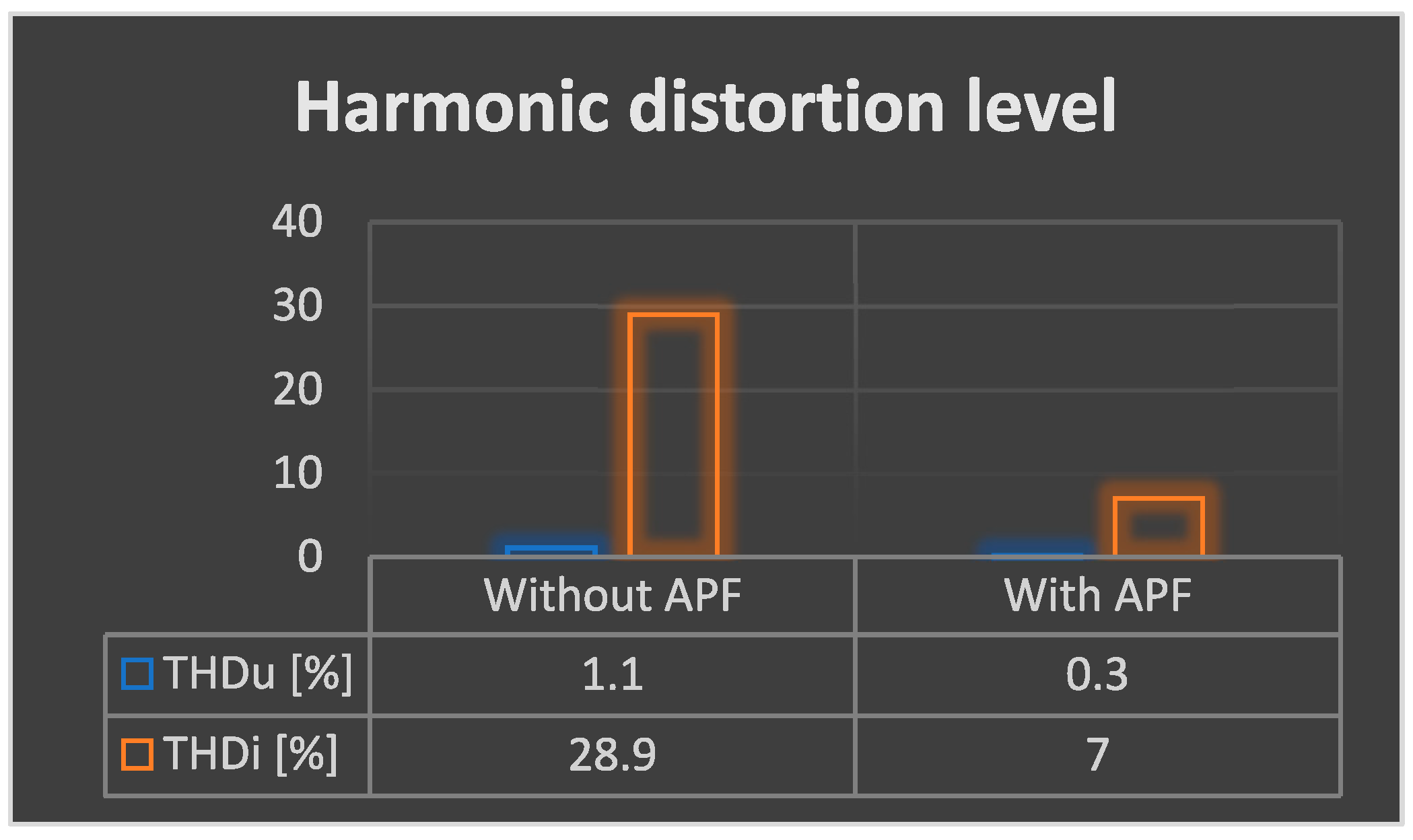

5.2.2. DQ Control

- -

- TDHU—from 1.1% to 0.3%,

- -

- TDHI—from 28.9% to 7%.

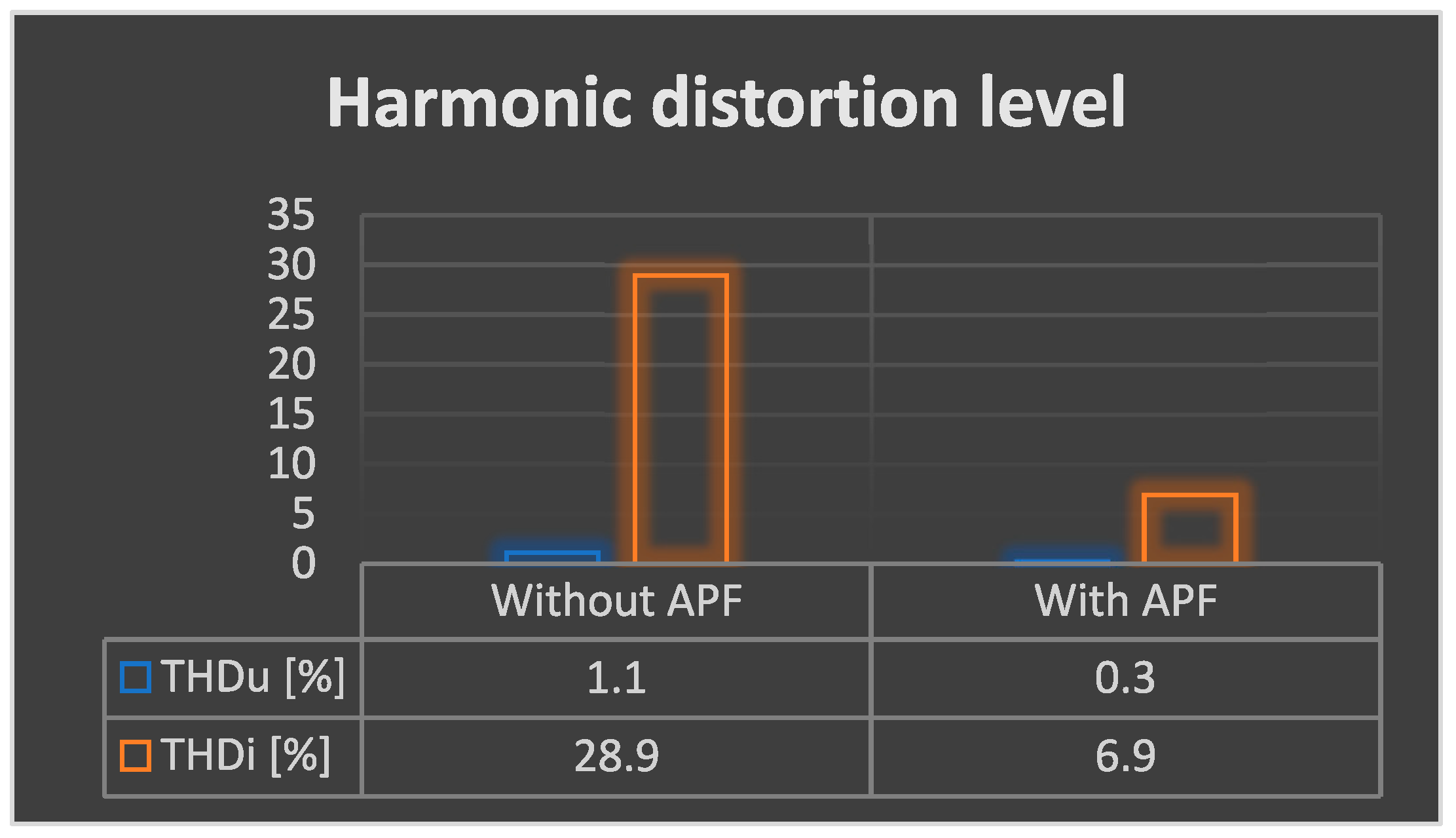

5.2.3. Principle of Maximum (MAX) Control Method

- -

- THDu decreases from 1.1% to 0.3%,

- -

- THDi decreases from 28.9% to 6.9%.

5.2.4. Synchronization of Current with the Voltage Positive-Sequence Component, SEC-POS

5.2.5. Low-Pass Filter Separating Polluting Components Control Method

5.2.6. Band-Stop (Notch) Filter Separating Polluting Components Control Method (Notch Control)

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APF | Active power filter |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FPGA | Field-programmable gate array |

| PCC | Point of Common Coupling |

| PLL | Phase-locked loop |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| SAPF | Shunt active power filter |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion |

| PQ | Instantaneous powers |

| DQ | Synchronous algorithm |

| MAX | Maximum principle |

| CI | Indirect control |

| SEC-POZ | Positive sequence |

| SRF | synchronous reference frame |

| LPF | Low-pass filter |

| BSF | Band-stop filter |

References

- Pinto, J.G.; Exposto, B.; Monteiro, V.; Monteiro, L.F.C.; Couto, C.; Afonso, J.L. Comparison of current-source and voltage-source Shunt Active Power Filters for harmonic compensation and reactive power control. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012-38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 5161–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.A.; Elgenedy, M.A.; Williams, B.W. Model Predictive Current Control for Low-cost Shunt Active Power Filter. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buso, S.; Malesani, L.; Mattavelli, P. Comparison of current control techniques for active filter applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1998, 45, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Pontt, J.; Silva, C.A.; Correa, P.; Lezana, P.; Cortes, P.; Ammann, U. Predictive current control of a voltage source inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2007, 54, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.A.; HassanniaKheibari, M.; Sadeghi, G. Control of a shunt Active Power Filter with Voltage Source Model to Improve the Power Quality Performance. Int. J. Ind. Electron. Control Optim. 2024, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldoire, A.; Phulpin, T.; Alali, M.A.E. Losses and Efficiency Evaluation of the Shunt Active Filter for Renewable Energy Generation. Electronics 2025, 14, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybko, M.; Brovanov, S.; Udovichenko, A. DC-Link Capacitance Estimation for Energy Storage with Active Power Filter Based on 2-Level or 3-Level Inverter Topologies. Electricity 2025, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.-W.; Xu, J.; Al-Shamma’a, A.A.; Farh, H.M.H.; Aboudrar, I.; Oubail, Y.; Alaql, F.; Alfraidi, W. Optimized Energy Management Strategy for an Autonomous DC Microgrid Integrating PV/Wind/Battery/Diesel-Based Hybrid PSO-GA-LADRC Through SAPF. Technologies 2024, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.-Z.; Akagi, H.; Nabae, A. Study of active power filters using quad series voltage source PWM converters for harmonic compensation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1990, 5, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Abeed, A.; Rabby, K.M.; Rahaman, H.; Hossain, A.; Al Nur, R.; Kabir, A.; Mahbub, U. Series active power filter implementation using P-Q theory. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 18–19 May 2012; pp. 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Mahela, O.; Gafoor Shaik, A. Topological aspects of power quality improvement techniques: A comprehensive overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.; Verdelho, P.; Marques, G. An Instantaneous Active and Reactive Current Component Method for Active Filters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2000, 15, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Agarwal, P. Design Simulation and Experimental Investigations, on a Shunt Active Power Filter for Harmonics, and Reactive Power Compensation. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2003, 31, 671–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Al-Haddad, K.; Chandra, A. A review of active filters for power quality improvement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1999, 46, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Su, W.-F.; Lu, S.-L.; Chen, C.-L.; Huang, C.-L. Operation strategy of hybrid harmonic filter in demand-side system. In Proceedings of the IAS ‘95. Conference Record of the 1995 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Thirtieth IAS Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 October 1995; pp. 1862–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Divan, D. Synchronous frame-based controller implementation for a hybrid series active filter system. In Proceedings of the IAS ‘95. Conference Record of the 1995 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Thirtieth IAS Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 October 1995; pp. 2531–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, W.; Samotyj, M.; Noyola, A. Survey of active power line conditioning methodologies. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1990, 5, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Garcia, J.; Moran, L. Control system for three phase active power filter which simultaneously compensates power factor and unbalanced loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1995, 42, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Agarwal, P.; Gupta, H.O. Simulation and Experimental Investigations on a Shunt Active Power Filter for Harmonics and Reactive Power Compensation. IETE Tech. Rev. 2003, 20, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Al-Haddad, K.; Chandra, A. Computer-aided modeling and simulation of active power filters. Electr. Mach. Power Syst. 1999, 27, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Fernandes, B.; Dubey, G. An instantaneous reactive voltampere compensator and harmonic suppressor system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1999, 14, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 519–2014 (Revision of IEEE Std 519–1992); IEEE Recommended Practice and Requirement for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–29.

- IEC 61000-3-2 Consolidated Version—IEC 61000-3-2:2018+AMD1:2020+AMD2:2024 CSV, IEC 61000-3-2, IEC 61000-3-2:2018; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 3–2: Limits—Limits for Harmonic Current Emissions (Equipment Input Current ≤ 16 A per Phase). IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Akagi, H.; Kanazawa, Y.; Nabae, A. Instantaneous reactive power compensators comprising switching devices without energy storage components. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1984, IA-20, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichan, M.; Abrishamifar, A.; Fazeli, M.; Arefian, M. A modified synchronous detection method with power factor control and suitable performance under non-ideal grid voltage applicable for three phase active power filters. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tehran, Iran, 20–22 May 2014; pp. 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyuk, M.; Tan, A.; İnci, M.; Tumay, M. A notch filter based active damping of llcl filter in shunt active power filter. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), Novi Sad, Serbia, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, D.; Bakhshai, A.; Joos, G.; Mojiri, M. An adaptive notch filtering approach for harmonic and reactive current extraction in active power filters. In Proceedings of the 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics, Orlando, FL, USA, 10–13 November 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, J.; Cajhen, R.; Seliger, M.; Jereb, P. Active power filter for nonlinear AC loads. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1994, 9, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, T.; Okuma, S.; Uchikawa, Y. A study on the theory of instantaneous reactive power. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1990, 37, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, H.-L. Performance comparison of the three-phase active power filter algorithms. IEE Proc.—Gener. Transm. Distrib. 1995, 142, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Divan, D.M. Simple topologies for single-phase AC line conditioning. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the 1991 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Dearborn, MI, USA, 28 September 1991–4 October 1991; pp. 911–917. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey, D.A.; Al-Zamel, A.M.A.M. Single-phase active power filters for multiple nonlinear loads. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1995, 10, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, Z.; Sabanovic, A. Active filter control using a sliding mode approach. In Proceedings of the 1994 Power Electronics Specialist Conference—PESC’94, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–25 June 1994; pp. 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Saetieo, S.; Devaraj, R.; Torrey, D.A. The design, implementation of a three-phase active power filter based on sliding mode control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1995, 31, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, S.; Mohan, N. Comparison of frequency, time domain neural network controllers for an active power filter. In Proceedings of the IECON ‘93—19th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics, Maui, HI, USA, 15–19 November 1993; pp. 1099–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Xie, S. Review of the control strategies applied to active power filters. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Electric Utility Deregulation, Restructuring and Power Technologies, Hong Kong, China, 5–8 April 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrasa, M.; Pouresmaeil, E.; Zabihi, S.; Rodrigues, E.M.G.; Catalão, J.P.S. A control strategy for the stable operation of shunt active power filters in power grids. Energy 2016, 96, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Ren, Y.; Cao, Q.; Wang, L.; Yin, J. A Modified Control Strategy for Three-Phase Four-Switch Active Power Filters Based on Fundamental Positive Sequence Extraction. Processes 2024, 12, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakria, D.; Laouid, A.A.; Korich, B.; Beladel, A.; Teta, A.; Mohammedi, R.D.; Elsayed, S.K.; Ali, E.; Aeggegn, D.B.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. An optimized shunt active power filter using the golden Jackal optimizer for power quality improvement. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litrán, S.P.; Salmerón, P. Analysis and design of different control strategies of hybrid active power filter based on the state model. IET Power Electron. 2012, 5, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znaczko, P.; Chamier-Gliszczynski, N.; Kaminski, K. Experimental Study of Solar Hot Water Heating System with Adaptive Control Strategy. Energies 2025, 18, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Experimental Test Bench APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/0FAP0L_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Principle of Synchronization of Current with the Voltage Positive-Sequence Component (SEC-POZ) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/1_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Low-Pass Filter Separating Polluting Components Method (LPF) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/2_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Principle of Maximum (MAX) Control STRATEGY IMPLEMENTED on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/3_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Principle of Instantaneous Powers (PQ) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/4_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Principle of Synchronous Algorithm (DQ) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/5_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Band-Stop (Notch) Filter Separating Polluting Components Method (BSF) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/6_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Principle of Indirect Control (CI) Control Strategy Implemented on the APF Prototype. Available online: http://cresc-intel.ugal.ro/images/Filme/7_UGAL.mp4 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Gaiceanu, M.; Epure, S.; Solea, R.C.; Buhosu, R.; Vlad, C. Low-Voltage Test Bench Experimental System for Current Harmonics Mitigation. Energies 2025, 18, 5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiceanu, M.; Epure, S.; Solea, R.C.; Buhosu, R. Power Quality Improvement with Three-Phase Shunt Active Power Filter Prototype Based on Harmonic Component Separation Method with Low-Pass Filter. Energies 2025, 18, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, G.; Ionut, E.S.; Constantin, S.R.; Razvan, B. Unification of the Implementation and Testing of Control Algorithms for Three-Phase, Low-Voltage, Parallel-Type Active Power Filters, in Experimental Stand and in Prototypes, Active Power Filters. Patent 137988 A2, 25 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, G.; Ionut, E.S.; Constantin, S.R.; Razvan, B.; Alexandru, D.; Iulian, G. Experimental System for Implementing and Testing Parallel-Type Three-Phase Low-Voltage Active Electronic Power Filters, Has Programmable Three-Phase Electrical Loads and Some Interface Inductances Provided Between Voltage Inverter and Common Source-Polluting Load Connection Point. Patent RO137368-A2, 21 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, D.; Peng, Z.; Shao, D.; Liu, J. Indirect Current Control Method Based on Reference Current Compensation of an LCL-Type Grid-Connected Inverter. Energies 2022, 15, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govil, V.K.; Tripathi, S.M.; Sahay, K. Real-time assessment of PV-DSTATCOM for grid power quality enhancement using an indirect current control strategy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrillaga, J.; Watson, N.R.; Murray, N.J. Modeling and simulation of the propagation of harmonics in electric power networks. I. Concepts, models, and simulation techniques. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1996, 11, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepziba, J.R.; Balaji, G. A modified hysteresis current controller with DFCEA for current harmonic mitigation using PV-SHAPF. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2023, 47, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, R. Indirect current controlled shunt active power filter for power quality improvement. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 62, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Han, S.; Yan, G. Parallel filtering scheme for fast symmetrical component extraction based on asynchronous coordinate transformation. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1206248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Lu, Z. Flexible power regulation and current-limited control of the grid-connected inverter under unbalanced grid voltage faults. IEEE Trans. Industrial Electron. 2017, 64, 7425–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, B.; Teng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X. A harmonic current detection algorithm for aviation active power filter based on generalized delayed signal superposition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Robina, P.; Rouzbehi, K.; Gordillo, F.; Pou, J. Grid-Following Voltage Source Converters: Basic Schemes and Current Control Techniques to Operate with Unbalanced Voltage Conditions. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Ni, L. Performance and harmonic detection algorithm of phase locked Loop for parallel APF. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Said, M.; Ghoniem, R.M.; Barakat, A.F. Implementation of an Electronically Based Active Power Filter Associated with a Digital Controller for Harmonics Elimination and Power Factor Correction. Electronics 2022, 11, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Sahoo, S.; Rath, D. Harmonics Reduction Using Adaptive Notch Filter Based Active Power Filter. Dogo Rangsang Res. J. 2020, 10, 75–85. Available online: https://www.journal-dogorangsang.in/no_2_may_20/13.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Singh, B.; Kant, K.; Arya, S.R. Notch filter-based fundamental frequency component extraction to control distribution static compensator for mitigating current-related power quality problems. IET Power Electron. 2015, 8, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Zhao, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. High-Frequency Harmonic Suppression Strategy and Modified Notch Filter-Based Active Damping for Low-Inductance HPMSM. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Palanisamy, K.; Paramasivam, S. A Technical Review on Control Strategies for Active Power Filters. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Emerging Trends and Innovations In Engineering And Technological Research (ICETIETR), Ernakulam, India, 11–13 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, S.H.; Radzi, M.A.M.; Mailah, N.F.; Wahab, N.I.A.; Jidin, A.; Lada, M.Y. Adaptive notch filter under indirect and direct current controls for active power filter. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2020, 9, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, W.; Guerrero, J.M. Asymmetrical grid fault ride-through strategy of three-phase grid-connected inverter considering network impedance impact in low-voltage grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobotaru, M.; Rosse, A.; Bede, L.; Karanayil, B.; Agelidis, V.G. Adaptive Notch filter based active damping for power converters using LCL filters. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 7th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunbul, A.; Alduraibi, A.; Zare, F. Harmonics Mitigation Filter for High-Power Applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 111406–111418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awamry, A.; Zheng, F.; Kaiser, T.; Khaliel, M. Robust Peak Detection Techniques for Harmonic FMCW Radar Systems: Algorithmic Comparison and FPGA Feasibility Under Phase Noise. Signals 2025, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.; Kütt, L.; Iqbal, M.N.; Shabbir, N.; Raja, H.A.; Sardar, M.U. A Review of Harmonic Detection, Suppression, Aggregation, and Estimation Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, B.; Xiu, L. A fast positive-sequence component extraction method with multiple disturbances in unbalanced conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 8820–8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanov, D.; Djagarov, N.; Enchev, G.; Djagarova, J.; Blaabjerg, F. Harmonic Compensation in Ship Power System Using Peak Detection Control Strategy Based Shunt Active Power Filter. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.E.; Melin, P.E.; Espinosa, E.; Baier, C.R.; Pesce, C.; Cormack, B. A Low-Cost Evaluation Tool for Synchronization Methods in Three-Phase Power Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X. Improved PR Control Without Load Current Sensors and Phase-Locked Loops for APFs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, Z.; Beladel, A.; Kouzou, A.; Rodriguez, J.; Abdelrahem, M. Four-Wire Three-Level NPC Shunt Active Power Filter Using Model Predictive Control Based on the Grid-Tied PV System for Power Quality Enhancement. Energies 2024, 17, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ibacache, R.; Carvajal, R.; Herrera-Hernández, R.; Agüero, J.C.; Silva, C.A. A Complex-Valued Stationary Kalman Filter for Positive and Negative Sequence Estimation in DER Systems. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, G.; Silviu, E.; Razvan, S.; Razvan, B. Static Power Equipment for the Active Elimination of Harmonics from the National Energy Grid. Ann. Mar. Sci. 2024, 8, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S.F.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S.; Irshad, S.M. A developed DQ control method for shunt active power filter to improve power quality in transformers. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karchi, N.; Kulkarni, D. LMS Adaptive FIR Filter-Predictive Controller Based On D-Q Control Theory for Grid-Connected Solar PV System. In Proceedings of the Second Global Conference on Recent Developments in Computer and Communication Technologies (GC-RDCT 2022), Mangalore, India, 27–29 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, M.B.; Patel, N.D.; Bhavsar, P.R.; Vaghamshi, A.L.; Mali, S.D.; Patni, V.N.; Jaradi, P.K.; Trivedi, T.; Gupta, C. Implementation of Shunt Active Power Filter using DSP Controller based on Synchronous Reference Frame for Harmonic Mitigation. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 4565–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Mekhilef, S. Current harmonics compensation with three-phase four-wire shunt hybrid active power filter based on modified D–Q theory. IET Power Electron. 2015, 8, 2265–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pote, M.S.; Dhande, N. Power Quality Control Strategy Using D-Q Theory for Single Phase Inverter in Generation System Using MATLAB. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2021, 7, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Samal, P.; Panda, A.K.; Guerrero, J.M. Implementation of bio-inspired flower pollination algorithm in distribution system harmonic mitigation scheme. In Proceedings of the 2021 1st International Conference on Power Electronics and Energy (ICPEE), Bhubaneswar, India, 2–3 January 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Harun, I.I. Harmonic Mitigation using Shunt Active Power Filter Based on Synchronous Reference Frame Theory. Bachelor Thesis, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Sarawak, Malaysia, July 2023. Available online: https://ir.unimas.my/id/eprint/43095/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Ionescu, F.; Nitu, S.; Rosu, E. Preocupari Actuale in Domeniul Electronicii de Putere; Editura SECOREX: Bucharest, Romania, 2001; ISBN 973-85298-3-2. [Google Scholar]

- Makaras, R.; Goolak, S.; Lukoševičius, V. Investigation of the Influence of Filter Approximation on the Performance of Reactive Power Compensators in Railway Traction Drive Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Ávila, E.; Arévalo, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Espinoza, J.L.; Albornoz-Vintimilla, E.; Jurado, F. Improving V2G Systems Performance with Low-Pass Filter and Fuzzy Logic for PV Power Smoothing in Weak Low-Voltage Networks. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 61000-6-2; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 6-2: Generic Standards—Immunity Standard for Industrial Environments. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN 61000-6-4; Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—Part 6-4: Generic Standards—Emission Standard for Industrial Environments. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN 50178; Electronic Equipment for Use in Power Installations. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Marshall, D.; van Wyk, J. An evaluation of the real-time compensation of fictitious power in electric energy networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1991, 6, 1774–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabae, A.; Nakano, H.; Togasawa, S. An instantaneous distortion current compensator without any coordinate transformation. In Proceedings of the IEEJ International Power Electronics Conference-Yokohama, Yokohama, Japan, 3–7 April 1995; pp. 1651–1655. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Mekhilef, S.; Mokhlis, H. DQ-axis Synchronous Reference Frame based P-Q Control of Grid Connected AC Microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GUCON), Greater Noida, India, 2–4 October 2020; pp. 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, S.; Papachristodoulou, A.; Kosmatopoulos, E.B. Adaptive pulse width modulation design for power converters based on affine switched systems. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2018, 30, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intermittent Effects | Steady State Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Load current () |

|

|

| Rated Voltage | 400 V ±10% [V] | ||

| Rated frequency | 50 [Hz] | ||

| Rated current | 125 [A] | ||

| Phase numbers | 3 Phase + PE | ||

| Degree of protection | IP21 | ||

| Cooling | Forced cooling | ||

| Compliance standards | EN 61000-6-2 [92], EN 61000-6-4 [93], EN 50178 [94] | ||

| Control method | LabVIEW FPGA, principle of instantaneous powers (PQ) | ||

| Communication interface | ETHERNET; RS 232; RS 485; CAN; USB. | ||

| Harmonic range | 1–50 (50–2500 Hz/50 Hz) | ||

| Dimensions (L × W × H) mm | 1020 × 370 × 1170 | ||

| Main circuit fuses | Yinrong RT18L-125 100 A | ||

| Auxiliary circuit fuses | Schrack AM417506 C16/1N | ||

| Climatic conditions | Ambient temperature | Relative humidity | Atmospheric pressure |

| Operational | 5–40 °C | 5–85% | 86–106 kPA |

| Storage | −25–55 °C | 5–95% | 86–106 kPA |

| Transport | −25–70 °C | 95% | 70–106 kPA |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 4.3 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 5.7 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 7 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 6.9 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 5.1 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 7 |

| Without Active Power Filter | With Active Power Filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage level test 230 Vac | THDU [%] | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| THDI [%] | 28.9 | 5.6 |

| No. | Control Strategies of the APF Prototypes | THDu [%] | THDi [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Developed on the principle of instantaneous powers (PQ) | 0.3 | 5.7 |

| 2 | Developed on the principle of synchronous algorithm (DQ) | 0.3 | 7 |

| 3 | Developed on the principle of maximum (MAX) | 0.3 | 6.9 |

| 4 | Developed on the principle of indirect control (CI) | 0.3 | 4.3 |

| 5 | Developed on the principle of synchronization of current with the voltage positive-sequence component (SEC-POZ) | 0.2 | 5.1 |

| 6 | Developed on the low-pass filter separating polluting components method (LPF) | 0.3 | 7 |

| 7 | Developed on the band-stop (notch) filter separating polluting components method (BSF) | 0.3 | 5.6 |

| Control Type | Instantaneous Power Theory (p–q) | Synchronous Reference Frame (d–q) | Maximum Detection | Positive Sequence Synchronization | Low-Pass Filter-Based | Indirect Control | Notch Filter Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Power decomposition in α–β frame | Transformation to d–q rotating frame | Extracts maximum values of distorted current | Extracts fundamental positive-sequence | Filters harmonics using LPF | Uses a reference estimation + error correction | Filters specific frequency (50/60 Hz) |

| Domain | Time domain (α–β components) | Synchronous rotating frame | Time domain | Frequency domain (sequence components) | Time domain | Hybrid (model + feedback) | Frequency domain |

| Harmonic Compensation | High (for 3-phase 3-wire) | High (especially for unbalanced systems) | Moderate | Good (depends on extraction accuracy) | Moderate to High | Depends on controller | Excellent for targeted harmonics |

| Reactive Power Compensation | Yes | Yes | Not directly | Not directly | Not directly | Yes | Not directly |

| Reference Current Accuracy | High (if balanced) | Very High (even if unbalanced) | Moderate | High (with PLL) | Moderate | Moderate to High | Very High (for known freq.) |

| Computational Complexity | Moderate | High (due to transformations & PLL) | High (requires sequence extraction) | Low | Medium | Medium | |

| Real-Time Capability | Good | Can be limited by PLL performance | Very Good | Dependent on synchronization speed | Very Good | Good | Good |

| Dynamic Response | Moderate | High (if PLL is fast) | Fast | Slower (due to sequence extraction) | Slower (depends on filter order) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sensitivity to Grid Distortion | High | Lower (if proper synchronization) | High | Low | Moderate | Varies | Low |

| Implementation Difficulty | Moderate | Complex | Easy | Complex | Easy | Moderate | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaiceanu, M.; Epure, S.; Solea, R.C.; Buhosu, R.; Vlad, C.; Marin, G.-A. Comparison of Direct and Indirect Control Strategies Applied to Active Power Filter Prototypes. Energies 2025, 18, 6337. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236337

Gaiceanu M, Epure S, Solea RC, Buhosu R, Vlad C, Marin G-A. Comparison of Direct and Indirect Control Strategies Applied to Active Power Filter Prototypes. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6337. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236337

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaiceanu, Marian, Silviu Epure, Razvan Constantin Solea, Razvan Buhosu, Ciprian Vlad, and George-Andrei Marin. 2025. "Comparison of Direct and Indirect Control Strategies Applied to Active Power Filter Prototypes" Energies 18, no. 23: 6337. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236337

APA StyleGaiceanu, M., Epure, S., Solea, R. C., Buhosu, R., Vlad, C., & Marin, G.-A. (2025). Comparison of Direct and Indirect Control Strategies Applied to Active Power Filter Prototypes. Energies, 18(23), 6337. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236337