1. Introduction

The acceleration of road transport electrification is fueled by policies and technology advancements. Precise prediction and analysis of EV energy consumption are central to vehicle range estimation, battery sizing, and grid impact assessment. Traditional physics-based models (power-balance and vehicle-dynamics equations) are interpretable but require detailed vehicle parameters and are sensitive to unmodeled factors. Data-driven AI models can ingest diverse telemetry (vehicle CAN (Controller Area Network), GPS (Global Positioning System), map, weather, traffic) and learn complex nonlinear mappings from observable features to instantaneous or trip-level energy use, enabling new applications such as energy-efficient routing, driver coaching, and predictive charging. However, building robust AI models faces challenges of data heterogeneity, domain shift, privacy, and explainability. Recent reviews and empirical studies demonstrate promising accuracy improvements using ML/DL, while also emphasizing careful dataset design and validation.

EVs emerged as a key player in sustainable transportation, offering the potential to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reliance on fossil fuels [

1]. With the global EV market projected to expand exponentially in the next decade, optimizing energy consumption and improving energy efficiency has become a critical area of research [

2]. The integration of AI into the analysis of EV energy consumption presents a transformative approach, enabling real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and intelligent decision-making for both vehicle operation and infrastructure management [

3].

EVs rely on electric energy stored in battery packs, whose efficiency and longevity are affected by multiple factors including driving behavior, environmental conditions, route characteristics, and vehicle load [

4]. Traditional methods of evaluating EV energy consumption, such as empirical testing and simulation-based approaches, often fail to capture the dynamic interactions between these factors. AI-based models, leveraging ML and DL algorithms, offer enhanced capabilities in capturing complex, non-linear relationships inherent to EV energy systems [

5].

AI techniques (

Table 1), particularly neural networks, support vector machines (SVMs), and ensemble learning methods, can predict energy consumption patterns, estimate battery degradation, and optimize energy usage under varying conditions [

6]. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been utilized to analyze spatiotemporal driving data, while recurrent neural networks (RNNs), including long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, excel in capturing temporal dependencies in vehicle energy profiles [

7].

Despite the promise of AI to enhance EV energy efficiency, several challenges persist. High-dimensional datasets from vehicle sensors, weather data, and traffic conditions require efficient feature extraction and real-time processing [

8]. Additionally, AI models must be generalizable across different vehicle types and driving environments to be practically applicable. However, the adoption of AI also presents opportunities for smart energy management systems, predictive maintenance, and adaptive eco-routing strategies [

9].

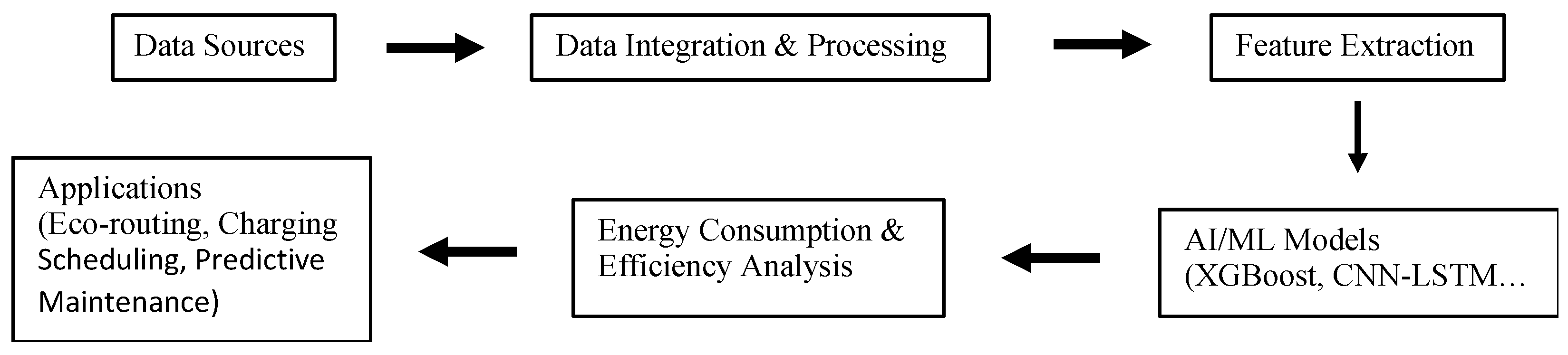

In

Figure 1, the AI-based framework integrates vehicle sensor data, driving patterns, and environmental factors to predict energy consumption and optimize efficiency.

Here, the conceptual framework figure for AI-based EV energy analysis shows the flow from data sources through preprocessing, AI/ML modeling, energy efficiency analysis, and final applications like eco-routing and predictive maintenance.

The Problem Statement can be formulated in two main orientations:

Instantaneous power demand estimation: Predict electrical power P(t) (W) at time t given a feature vector x(t) including vehicle state and contextual info.

Trip-level energy consumption: Predict total energy for a planned route between times t0 and t1.

where

(i) stands for a given trip between

and

where n is the number of different trips for the total available battery capacity

C.

Physics-based models are widely used in analyzing and predicting the energy consumption of EVs, as they rely on first-principles formulations of vehicle dynamics, aerodynamics, and thermodynamics. Despite their interpretability and strong grounding in physical laws, such models face several limitations when applied to real-world driving conditions. First, they are highly sensitive to parameter uncertainty. Factors such as tire rolling resistance coefficients, aerodynamic drag coefficients, auxiliary load power demand, and drivetrain efficiency maps are often assumed as static, though they vary significantly with temperature, vehicle age, and road conditions [

10,

11]. This limits their accuracy under diverse operating conditions.

Second, physics-based models struggle to capture stochastic and behavioral aspects of human driving. Driving style variability, traffic dynamics, and route-level irregularities introduce nonlinearities that are difficult to represent with deterministic equations [

12]. Additionally, the inclusion of external influences such as weather, road slope, and congestion requires complex parameterization that increases computational cost and reduces scalability for large-scale fleet-level energy prediction [

13].

Third, calibration and validation of physics-based models are resource-intensive. They require extensive experimental data collection, wind tunnel measurements, and chassis dynamometer tests, which limit their applicability in rapidly changing scenarios such as shared mobility or real-time eco-routing [

14]. Moreover, their reliance on predefined assumptions often leads to poor generalization when applied outside of controlled environments, e.g., urban stop-and-go traffic compared to highway driving [

15].

These limitations highlight the challenges of using purely physics-based approaches for EV energy prediction in complex, data-rich environments. To overcome such barriers, hybrid approaches that integrate physical modeling with data-driven methods have been proposed, offering improved adaptability, robustness, and predictive accuracy [

12,

14].

Despite its promise, the use of AI in analyzing energy consumption and energy efficiency of EVs faces several challenges. A major issue is the dependence on high-quality, large-scale datasets, which are often difficult to collect due to privacy concerns, proprietary vehicle data restrictions, and variations in driving conditions. Moreover, AI models, especially DL approaches, tend to operate as “black boxes,” making it difficult to interpret their predictions and build trust among engineers, regulators, and consumers. These models can also suffer from overfitting, where they perform well on training data but fail to generalize under real-world scenarios with diverse road, weather, and traffic conditions. Another challenge lies in the computational cost and energy demand of training complex AI models, which ironically undermines the goal of sustainability. Finally, integrating AI-based insights into EV design and control systems requires cross-disciplinary collaboration between data scientists, automotive engineers, and policymakers, a process that is often slowed down by differences in expertise, standards, and objectives.

How can advanced data-driven and physics-based approaches be integrated to accurately model, predict, and optimize the energy consumption and efficiency of EVs under real-world operating conditions?

We ask how AI, particularly ML and data-driven approaches, is applied to analyze driving behavior and patterns in EVs, and how those behaviors affect energy consumption and efficiency with data sources and feature engineering approaches, common modeling methods, evaluation metrics, and applications (eco-driving, personalized energy prediction, route/charging optimization). A conceptual figure and an illustrative synthetic plot can demonstrate the energy impact of “smooth” vs. “aggressive” driving.

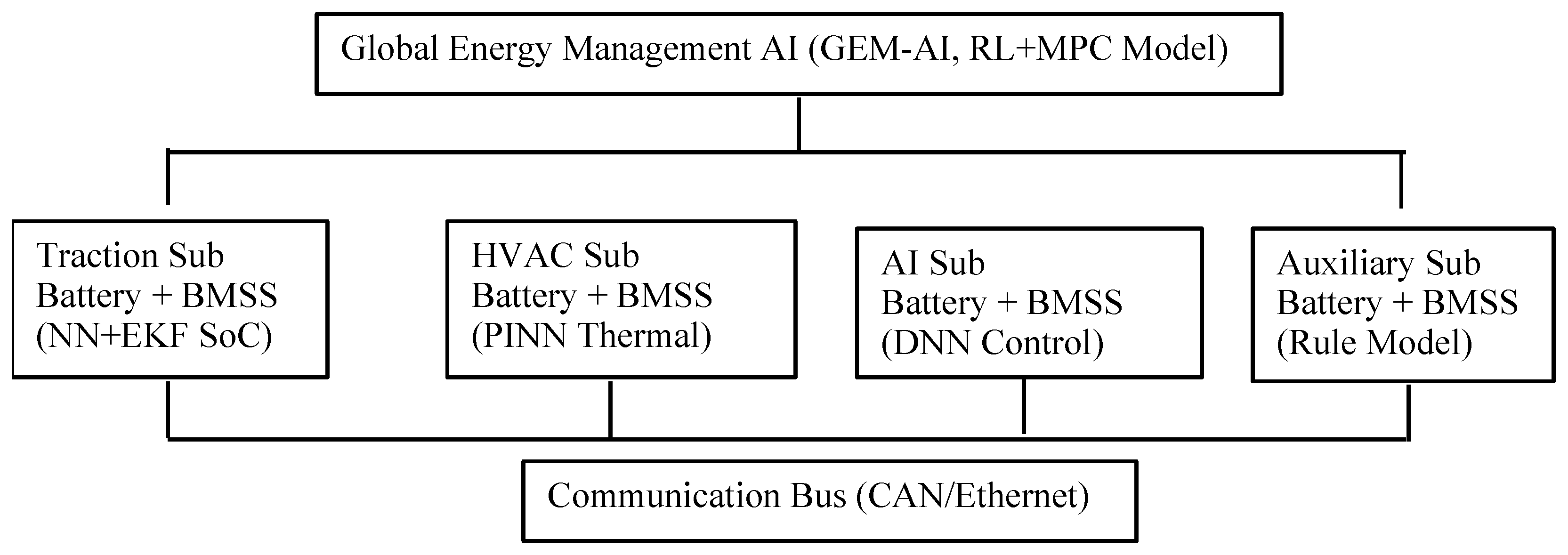

This research aims to study AI-based methodologies for analyzing EV energy consumption and optimizing energy efficiency. By integrating sensor data, historical driving patterns, and environmental conditions, the proposed approach seeks to provide actionable insights for drivers, fleet managers, and urban planners, ultimately contributing to sustainable and cost-effective EV operation. This research presents an in-depth analysis of the role of AI in EV energy consumption and efficiency assessment. It explores the limitations of traditional physics-based models and the challenges posed by current AI-driven approaches in accurately capturing dynamic energy behaviors, particularly under heterogeneous operating conditions. The study identifies unresolved issues in AI-based state estimation and range prediction, including inconsistencies in physical interpretability, data dependency, and cross-domain generalization. To address these challenges, the research introduces the concept of an Intelligent, Functionally Partitioned Battery System (IFPBS)—an innovative EV battery architecture composed of specialized sub-batteries dedicated to specific vehicle functions (e.g., traction, HVAC, AI, and auxiliary systems). This architecture aims to reduce AI computational impact on energy estimation, enhance range prediction accuracy, and optimize overall energy management efficiency through functional isolation and intelligent coordination among submodules.

2. Aspects of Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption and Efficiency Beyond the Reach of Physics-Based Models

Physics-based (first-principles) models describe the fundamental relationships between electrical, mechanical, and thermal phenomena in an EV. They can accurately model:

Battery electrochemistry (e.g., diffusion, reaction kinetics, Ohmic losses);

Powertrain dynamics (motor torque, inverter losses, drivetrain friction);

Aerodynamics and rolling resistance;

Thermal behavior (heat generation and dissipation).

These models are interpretable and grounded in physical laws, ideal for controlled prediction and design.

However, physics models struggle with complex, nonlinear, context-dependent, or stochastic processes that are difficult to model analytically. Physics-based models have long served as the foundation for analyzing and optimizing EV energy consumption. These models are grounded in first-principle formulations of thermodynamics, electrochemistry, and mechanics, providing analytical descriptions of energy transfer processes within traction systems, battery cells, and drivetrains. However, despite their accuracy under controlled or idealized conditions, physics-based models exhibit intrinsic limitations when applied to complex, real-world environments characterized by dynamic, stochastic, and human-influenced factors.

AI, through data-driven learning and adaptive inference, offers the capacity to overcome these limitations and provide predictive and prescriptive insights unattainable by classical physics formulations.

Table 2 shows the limits of physics models and the potential role of AI.

Table 3 shows examples of AI applications that fill the physics gaps.

In essence, while physics-based models remain indispensable for foundational understanding and first-principle validation, their descriptive power collapses in high-dimensional, stochastic, and behaviorally influenced systems. Artificial intelligence extends modeling capacity from deterministic causality to probabilistic inference, enabling the discovery of latent patterns and adaptive optimization strategies that are invisible to classical analytical methods. The future of EV energy consumption modeling thus lies in hybrid frameworks that combine the interpretability of physics with the adaptability of AI.

Physics models excel at understanding; AI excels at adapting.

Physics = Explainability, causality, and design insights;

AI = Pattern recognition, adaptability, and contextual optimization.

Together they form hybrid physics-informed AI systems, which leverage physical laws for reliability and AI for real-world adaptability.

A hybrid energy consumption model might combine both as:

where

fphysics captures deterministic components (speed, acceleration, slope, temperature);

fAI learns the residual patterns (driver habits, traffic, degradation).

2.1. Stochastic Driving Behavior and Human Influence

One of the primary limitations of physics-based models lies in their inability to accurately represent the stochastic nature of human driving behavior. Traditional models approximate driving cycles using predefined velocity–time profiles (e.g., WLTP (Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicle Test Procedure) or UDDS (Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule)), assuming average or standardized patterns of acceleration and deceleration. However, real-world driving involves context-dependent variability, including route familiarity, driver aggressiveness, and traffic-induced decision-making, none of which can be fully captured by deterministic equations of motion. AI models, particularly RNNs and transformer-based temporal predictors can learn hidden temporal dependencies between driver inputs, vehicle states, and environmental feedback [

16,

17]. This allows dynamic energy prediction and efficiency optimization tailored to individual driving patterns rather than population averages.

2.2. Environmental Variability and Nonlinear Coupling Effects

Environmental conditions such as ambient temperature, road grade, humidity, and wind drag exhibit nonlinear couplings that alter EV energy consumption. Physics-based models can account for these factors separately but fail to capture their complex interactions under transient conditions. For instance, the combined influence of humidity and low temperature can affect both aerodynamic drag and the internal resistance of the battery, resulting in nonlinear performance degradation that is difficult to represent through fixed-parameter thermodynamic models. AI approaches, such as Gaussian process regression and CNNs, can extract latent correlations from large-scale sensor data to model such multivariate dependencies without explicit analytical expressions [

18]. This enables improved adaptive energy management across heterogeneous environmental contexts.

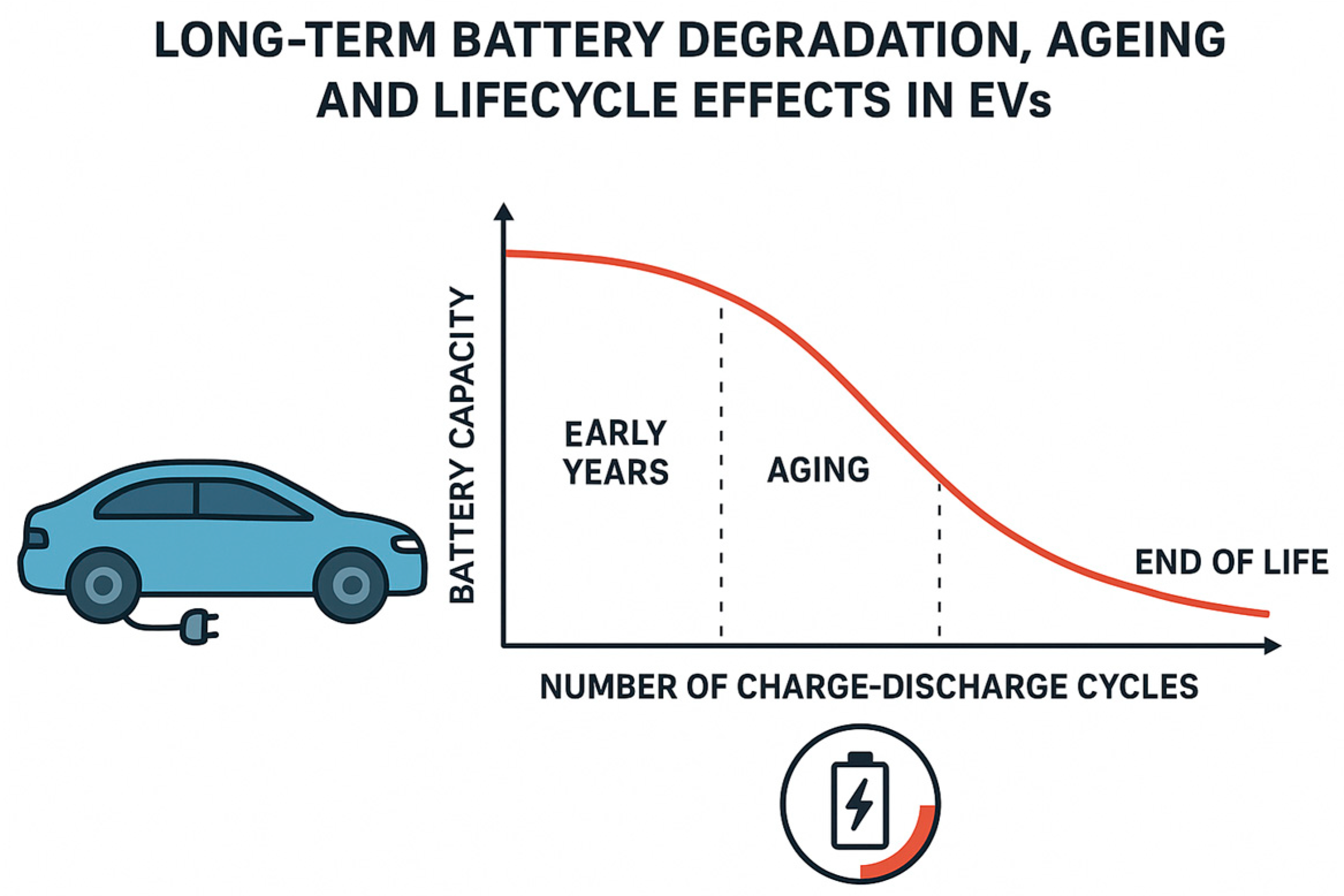

2.3. Degradation Dynamics and Unmodeled Aging Mechanisms

Battery degradation constitutes another domain where physics-based approaches reach their epistemic limits. Electrochemical-thermal-aging models (ECTA) can simulate capacity fade and impedance growth under certain operational profiles but often neglect unobserved microstructural degradation pathways such as electrode particle cracking, solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) inhomogeneity, and lithium plating at varying current densities. These processes are inherently path-dependent and exhibit high parametric uncertainty. ML frameworks, including physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and Bayesian inference models, can integrate partial physical laws with empirical data to infer degradation dynamics in real time [

19,

20]. This hybridization enhances the predictive reliability of remaining useful life (RUL) estimation under complex load and thermal histories.

2.4. Traffic, Infrastructure, and Systemic Interaction Effects

Energy consumption in EVs extends beyond the vehicle level to include system-level interactions within the transportation ecosystem. Traffic congestion, charging infrastructure density, and signal timing introduce spatial-temporal dependencies that cannot be represented in closed-form physical models. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) and graph neural networks (GNNs) have demonstrated superior performance in modeling these systemic effects, optimizing energy routing and load balancing at fleet and grid scales [

21,

22]. Through continuous learning from vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication data, AI enables cooperative optimization across heterogeneous agents, an inherently non-physical dimension that extends beyond the descriptive capacity of physics-based frameworks.

2.5. Cognitive Efficiency and Human–Machine Synergy

A further domain where physics models are fundamentally limited involves cognitive and behavioral adaptation in human–machine interaction. For instance, the efficiency of regenerative braking or eco-driving recommendations depends on the driver’s responsiveness, learning behavior, and cognitive load, none of which can be formulated as deterministic variables within Newtonian or thermodynamic systems. AI models employing RL and behavioral cloning can adaptively calibrate vehicle control parameters and feedback systems based on user-specific interaction data, enabling personalized energy efficiency optimization [

23].

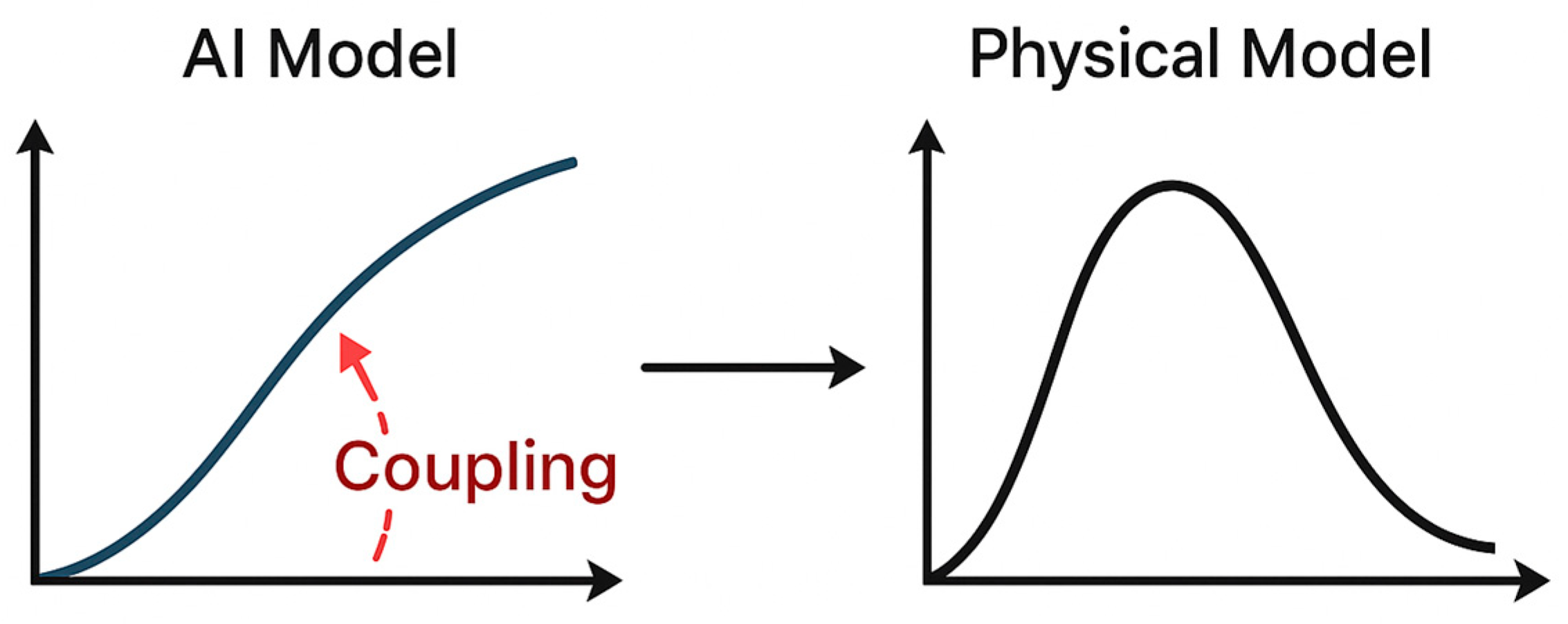

2.6. Synergistic Integration of AI and Physics

Rather than replacing physics-based models, AI complements them through hybrid or physics-informed ML frameworks. In such systems, physical laws provide structural priors or constraints, ensuring interpretability and physical consistency, while AI captures residual patterns unexplained by first-principles models. For instance, AI can learn correction functions for empirical losses in electric drivetrains or thermal dissipation, enhancing both accuracy and generalization.

3. Literature Review—AI in EV Energy Consumption and Efficiency Analysis

The integration of AI with traditional modeling frameworks marks a paradigm shift in EV energy research. By addressing the non-measurable, context-dependent, and time-evolving factors of EV operation, AI enables adaptive, real-world efficiency optimization that physics alone cannot achieve. This shift supports the emergence of intelligent energy management systems (IEMS) capable of learning from cumulative operational experience to enhance sustainability, safety, and performance throughout the EV life cycle.

AI methods (classical ML, DL, RL, and physics-informed ML) have rapidly become central for estimating, predicting, and optimizing energy consumption and efficiency in EVs. Research trends moved from purely data-driven and empirical formulas toward hybrid approaches that combine physical vehicle models with data-driven learning to improve generalization, interpretability, and robustness under limited data or domain shift [

24,

25,

26].

3.1. State-of-Charge (SoC) and State-of-Health (SoH) Estimation

Accurate SoC/SoH is foundational because energy estimates and range predictions depend heavily on battery state. DNNs (feed-forward, LSTM, CNN and ensemble methods (XGBoost/CatBoost) have been applied using current, voltage, temperature, and historical cycling features; results generally show improved accuracy over classical equivalent-circuit/extended Kalman filter approaches when properly trained and regularized [

27,

28]. Hybrid approaches that augment ML with online adaptation or metaheuristic tuning further improve robustness in varying thermal/usage conditions [

29]. However, models remain sensitive to dataset representativeness (cycling regimes, aging) and require explicit mechanisms to avoid overfitting and ensure extrapolation to new battery chemistries.

3.2. Trip-Level and Instantaneous Energy Consumption Prediction

Two main directions exist: (a) trip/route-level energy estimation (aggregate energy for a trip) and (b) instantaneous/segment-level prediction (power or energy per segment). Classical regression approaches (linear, SVR (Support Vector Regression)) give way to tree-based ensembles (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM (Gradient Boosting Machine)) and deep models (transformers, LSTMs, graph neural networks) that incorporate vehicle telemetry, speed profiles, elevation, traffic, HVAC (Heat Ventilation and Air Conditioning) use and environmental conditions. Large comparative studies show ensemble tree methods often perform best on tabular trip datasets, while sequence models excel at capturing temporal dependencies for high-resolution predictions [

30,

31]. Pretrained large models (transformer-based) are being explored for transfer learning to data-scarce contexts [

32].

3.3. Physics-Informed and Hybrid Modeling

Purely data-driven models can violate known physical constraints (energy conservation, vehicle dynamics). Physics-informed ML (PINNs and hybrid pipelines) integrates vehicle longitudinal dynamics, rolling/air drag, and battery electrochemistry constraints into the learning objective or architecture, improving extrapolation to unseen driving conditions and reducing required labeled data [

25,

33]. Recent works (as EV-PINN) demonstrated improved instantaneous power and cumulative energy predictions by embedding dynamics equations during training [

25]. This hybrid trend appears essential when deploying onboard where domain shift and safety are concerns.

3.4. Energy Management Systems and Control (Including RL)

AI is used at multiple control layers: supervisory energy management (power split in hybrid EVs, thermal management), eco-driving advisory, and charging scheduling. RL and model predictive control (MPC) augmented with learned models have been proposed for adaptive driving policies and real-time energy management. RL shows strong potential for personalized eco-driving strategies, but sample efficiency, safety constraints, and interpretability remain significant hurdles [

34].

3.5. Explainability, Uncertainty Quantification, and Real-World Deployment

Explainability and uncertainty quantification (UQ) are important for operator trust and safety. Methods such as Gaussian Processes for uncertainty, SHAP (SHapley Additive explanation)/feature-importance for interpretability, and Bayesian neural nets are being integrated into EV energy prediction pipelines. However, few real-world, large-scale deployment reports exist; bridging lab results to production requires careful dataset curation, domain adaptation, and calibrated UQ [

29].

3.6. Datasets, Benchmarks and Evaluation Practices

Progress is gated by dataset quality. Public datasets vary widely (vehicle types, sensors, geographic context). Recent systematic reviews emphasize the need for standardized benchmarks, common performance metrics (MAE (Mean Square Error), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), energy-percent error), and test protocols that include aging, HVAC use, road grade diversity and traffic levels to ensure fair comparisons [

25,

30].

3.7. Challenges and Open Problems

Key challenges remain:

Generalization & domain shift: models trained in one region or driving style do not always generalize. Physics constraints and transfer learning help but are not solved.

Data scarcity & label noise: high-resolution sensor data and battery labels (true SoC/SoH) are costly.

Interpretability & safety: for onboard control, provable safety and interpretable decisions are necessary.

Integration with grid and charging infrastructure: accurate vehicle energy forecasts are required for grid services and smart charging; coupling vehicle models with grid models is an open area.

Addressing these requires multidisciplinary approaches combining vehicle dynamics, battery science, ML, and software engineering [

24,

25,

26,

34].

3.8. Future Directions

Promising directions include: physics-informed pretraining for few-shot adaptation; graph/transformer architectures for spatio-temporal fleet modeling; RL with safe constraints for energy-aware driving; standardized benchmarks and open datasets annotated with HVAC, terrain, and aging; and tighter coupling between battery electrochemistry models and ML for long-horizon predictions [

25,

32,

33].

4. Energy Consumption in Electric Vehicles

EV energy consumption is a multifactorial outcome determined by vehicle dynamics, environment, and user behavior. With advances in predictive modeling and intelligent control, future EVs are expected to achieve higher efficiency and more accurate range predictions, ultimately improving adoption and sustainability.

Energy consumption in EVs is a critical performance metric that directly influences driving range, battery lifespan, and overall system efficiency. Unlike Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs), where fuel consumption is primarily determined by engine thermal efficiency, EV energy consumption is governed by electrochemical processes in the battery, electric drivetrain efficiency, auxiliary loads, and vehicle dynamics. Typically, EVs consume between 0.15–0.25 kWh per kilometer, depending on driving conditions, vehicle size, and environmental factors [

35,

36].

A key factor is the impact of cold weather on the driving ranges of EVs. In cold weather, driving ranges decrease because of the requirement to heat up the battery and the vehicle interior. In addition, low temperatures weaken the battery’s capacity to store and release energy. Consequently, measuring range losses necessitates empirical data gathered from real drivers. Data gathered from 4200 connected EVs across 5.2 million trips, and an online temperature tool for EV range is accessible in Ref [

37]. The energy consumption efficiency of the top-selling vehicles shows that the consumption efficiency of SUV models (Volvo and Jaguar) is greater than that of most sedan models and their consumption patterns.

Energy consumption for all vehicles in the study is lowest around 20–25 degrees Celsius, increasing at both lower and higher temperatures. The Volvo XC40 and Jaguar I-Pace generally show higher energy consumption compared to other models like the Tesla 3 Std and Tesla 3 LR. The Tesla 3 LR consistently demonstrates one of the lowest energy consumption rates across the tested temperature range [

37]. Temperature fluctuations significantly impact the energy efficiency of EVs, with optimal performance observed within a moderate temperature window.

From a physical perspective, EV energy consumption is primarily influenced by resistive forces such as aerodynamic drag, rolling resistance, and inertial loads during acceleration [

38]. Aerodynamic drag becomes the dominant factor at higher speeds, with energy consumption scaling approximately with the square of velocity [

39]. For instance, highway driving at 120 km/h can increase consumption by up to 30–40% compared to urban driving cycles [

40].

This diagram

Figure 2 illustrates the key factors influencing the range of an EV, categorized into three main areas:

Model: Vehicle characteristics like the year of manufacture and body shape play a role in determining range.

Battery: Battery specifications such as capacity (kWh), type, cooling mechanism, number of cells and modules, and voltage (V) are crucial for range.

Performance: Performance metrics like top speed (km/h), acceleration (0–100 km/h in seconds), curb weight (kg), and GVWR (kg) also impact the overall range.

EVs exhibit a nonlinear relationship between speed and energy consumption, where aerodynamic drag dominates at higher velocities, leading to increased battery discharge rates compared to urban driving conditions [

41]. For instance, the Tesla Roadster demonstrates superior efficiency at moderate highway speeds, achieving approximately 0.16 kWh/km, while energy consumption rises significantly beyond 120 km/h due to air resistance [

42]. In contrast, gasoline passenger cars typically exhibit peak efficiency near mid-range speeds but incur higher thermal and mechanical losses, averaging 7–9 L/100 km (≈0.65–0.80 kWh/km equivalent) under similar conditions [

43]. Unlike ICEVs, EVs maintain higher efficiency (80–90%) across varying loads, but their range diminishes more predictably with increasing speed, highlighting the trade-off between performance and endurance [

44]. This efficiency gap underscores EVs’ advantage in urban and peri-urban contexts, where regenerative braking and reduced idling losses further optimize energy usage [

45].

The optimal speed for energy efficiency differs significantly between EVs and gasoline-powered vehicles. EVs like the Tesla Roadster are generally more efficient at lower speeds, while gasoline cars tend to be most efficient at moderate highway speeds [

46].

On the other hand, regenerative braking provides EVs with an advantage in stop-and-go traffic by recovering a portion of kinetic energy, reducing net consumption [

47].

Environmental and operational conditions also play significant roles. Cold weather operation increases energy use due to reduced battery efficiency and heating demands, while hot climates increase cooling loads [

48]. Studies have shown that extreme temperatures can raise energy consumption by 15–40% depending on HVAC use [

49]. Furthermore, driving behavior—including aggressive acceleration and high-speed cruising—has been correlated with higher Wh/km usage, underlining the importance of eco-driving practices [

50].

In addition to physical modeling, data-driven methods are increasingly applied to predict and optimize EV energy consumption. ML models, such as Gradient Boosting and Recurrent Neural Networks, have been used to capture nonlinear dependencies between driving conditions, traffic flow, and energy demand [

31,

51]. These predictive models are particularly valuable for applications such as eco-routing, battery range estimation, and charging infrastructure planning.

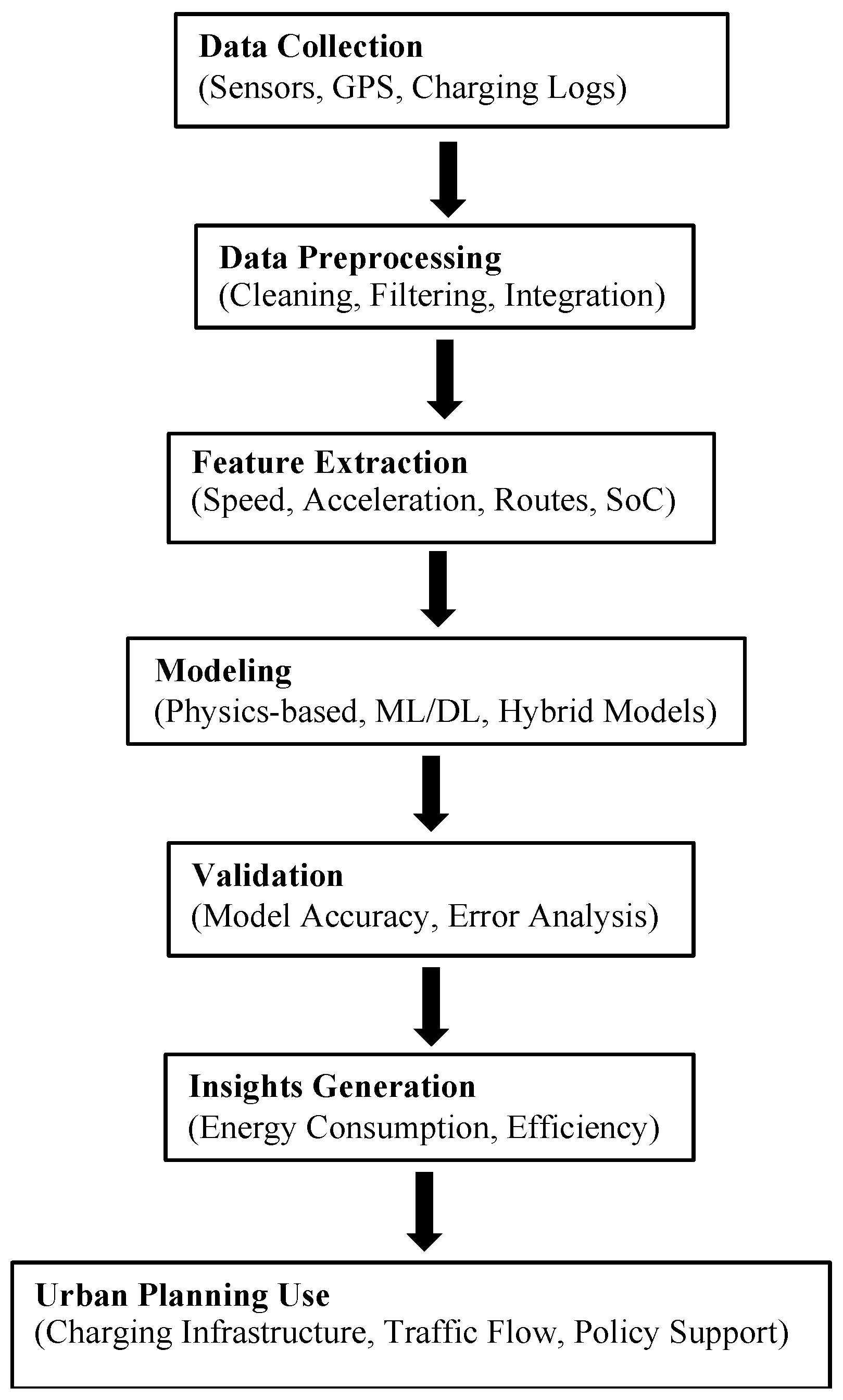

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate a framework for analyzing EV data, from gathering to potential applications, involving: The AI workflow in EVs emphasizes three key fundamental phases: data gathering, data processing, and possible application. The initial phase consists of gathering the necessary data to develop the energy model. The gathered data was separated into two categories: external conditions for warm temperature and for cold temperature readings. Warm temperature scenarios involve testing in the summer when the air temperature is between 18–26 °C, while cold temperature scenarios are conducted in the winter, with temperatures from −3 to 7 °C. The resulting data is subject to qualitative analysis and needs to be processed correctly. Data manipulation for developing AI models includes gathering, cleansing, and standardizing data to ready it for ML. This procedure also involves feature engineering, handling categorical variables, and dividing the data into training, validation, and test datasets. The models are subsequently trained on the training dataset, assessed on the validation dataset, and after modifying parameters if required, ultimately examined on the test set. The data that has been processed can be utilized to train new models. The chosen methods consist of linear regression, random forest, gradient boosting, and neural networks.

EV Data Gathering: Collecting various parameters like velocity, acceleration, battery metrics (voltage, current, SoC, temperature), ambient temperature, and location data. This data is used to derive distance and power/energy consumption.

Data Processing: Utilizing Python 3.9 with libraries like scikit-learn and TensorFlow for data cleaning, visualization, and the creation and validation of energy models. Model validation involves metrics such as residual plots, R2 score, and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

Potential Uses: The developed energy models can be applied to create energy maps, and generate road and simulation data, potentially integrating with tools like PTV Vissim (software) for traffic and mobility simulations.

5. Parameters Controlling Energy Consumption in Electric Vehicles

The energy consumption of EVs is influenced by a complex interplay of vehicle-specific, environmental, and operational parameters. Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing efficiency and extending driving range.

5.1. Vehicle Longitudinal Dynamics (Force Balance)

The total tractive force required from the EV’s motor is given by:

where

where

m = vehicle mass (including passengers),

a(t) = acceleration.

With Crr = rolling resistance coefficient, θ = road slope angle.

With ρ = air density, Cd = drag coefficient, Af = frontal area, v(t) = vehicle speed.

The mechanical power demanded at the wheels is:

The electric power drawn from the battery (considering drivetrain efficiency) is:

where

includes motor, inverter, gearbox, and battery efficiency.

- ◦

Battery Energy Consumption

Over a trip of duration T

This represents the total energy drawn from the battery.

Special Case—Constant Acceleration

If the EV accelerates from rest (v0 = 0) to v on a flat road (θ = 0), neglecting drag and rolling resistance for simplicity:

- ◦

Vehicle Dynamics Parameters:

Key factors include vehicle mass, aerodynamic drag coefficient (

Cd), and rolling resistance coefficient (

Crr). A heavier vehicle requires more energy during acceleration and hill climbing, while aerodynamic drag becomes significant at higher speeds. Rolling resistance, primarily a function of tire properties and road texture, affects consumption at lower speeds [

52].

The efficiency of the electric motor, power electronics, transmission, and battery system strongly determines the effective energy delivered to the wheels. Inverter switching losses, motor copper and iron losses, and battery charge/discharge efficiency directly influence consumption. Advanced power electronics and regenerative braking strategies can mitigate these losses [

53].

- ◦

Driving Behavior and Patterns:

Driving style, the parameter that depends the most on human factor, is characterized by acceleration aggressiveness, braking frequency, and cruising speed significantly impacts EV energy consumption. Studies show that aggressive driving can increase energy consumption by up to 30% compared to eco-driving strategies [

54]. Trip type (urban stop-and-go vs. highway cruising) also alters consumption due to differences in speed profiles and regenerative braking opportunities. Making this factor less human-dependent may well improve EV energy consumption efficiency.

- ◦

Environmental and Road Conditions:

External temperature, wind, and road gradient also play critical roles. Low temperatures reduce battery efficiency and increase auxiliary loads such as cabin heating, while uphill driving increases power demand due to gravitational forces [

55]. Headwinds amplify aerodynamic drag, further raising consumption.

Non-propulsion loads such as HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), infotainment, and lighting systems draw power directly from the traction battery. HVAC, in particular, is one of the largest contributors to increased energy demand in both hot and cold climates, potentially reducing driving range by 10–40% [

56].

- ◦

Energy Recovery Systems:

Regenerative braking improves energy efficiency by recapturing kinetic energy during deceleration. However, its effectiveness depends on traffic conditions, battery state-of-charge, and braking intensity [

57].

A holistic consideration of these parameters is essential for designing predictive models, optimizing control strategies, and enhancing vehicle energy efficiency in real-world applications.

Longitudinal dynamics describe how an EV moves forward or backward, governed by:

where

m is mass and

v is velocity.

Traditionally, this is modeled with physics based equations, but real-world conditions (traffic, driver behavior, road slope, tire wear, wind, etc.) make it complex.

AI corrects EV longitudinal dynamics by learning and compensating for model inaccuracies, adapting to real-world conditions, and improving predictive control for energy efficiency and safety.

AI does not “rewrite” the laws of physics, it corrects, adapts, and augments them. Specifically:

(a) Model Error Correction

Physics-based models are approximate. AI (ML, neural networks, Gaussian processes) learns the residual error between model predictions and measured vehicle data (CAN bus, GPS, accelerometers).

Example:

AI learns and corrects future predictions.

(b) Adaptive Estimation

AI dynamically adjusts parameters like rolling resistance coefficient, tire-road friction, and vehicle mass (which changes with load).

This makes longitudinal dynamics models self-calibrating in real time.

(c) Driver Behavior Prediction

(d) Road & Environment Adaptation

AI uses external data (road grade from GPS/HD (High Definition) maps, traffic flow, weather) to adjust longitudinal dynamics predictions.

E.g., predicting that drag increases in headwind and correcting expected energy consumption.

5.2. Control Applications

AI-enhanced longitudinal dynamics are crucial for:

Eco-driving: optimizing torque for minimum energy consumption.

Predictive cruise control: adjusting speed before inclines/declines.

Regenerative braking optimization: balancing comfort and energy recovery.

Autonomous driving: ensuring safe car-following and smooth acceleration.

5.3. Hybrid Modeling Approach

The most common setup is a Physics + AI hybrid model:

using data-driven insights.

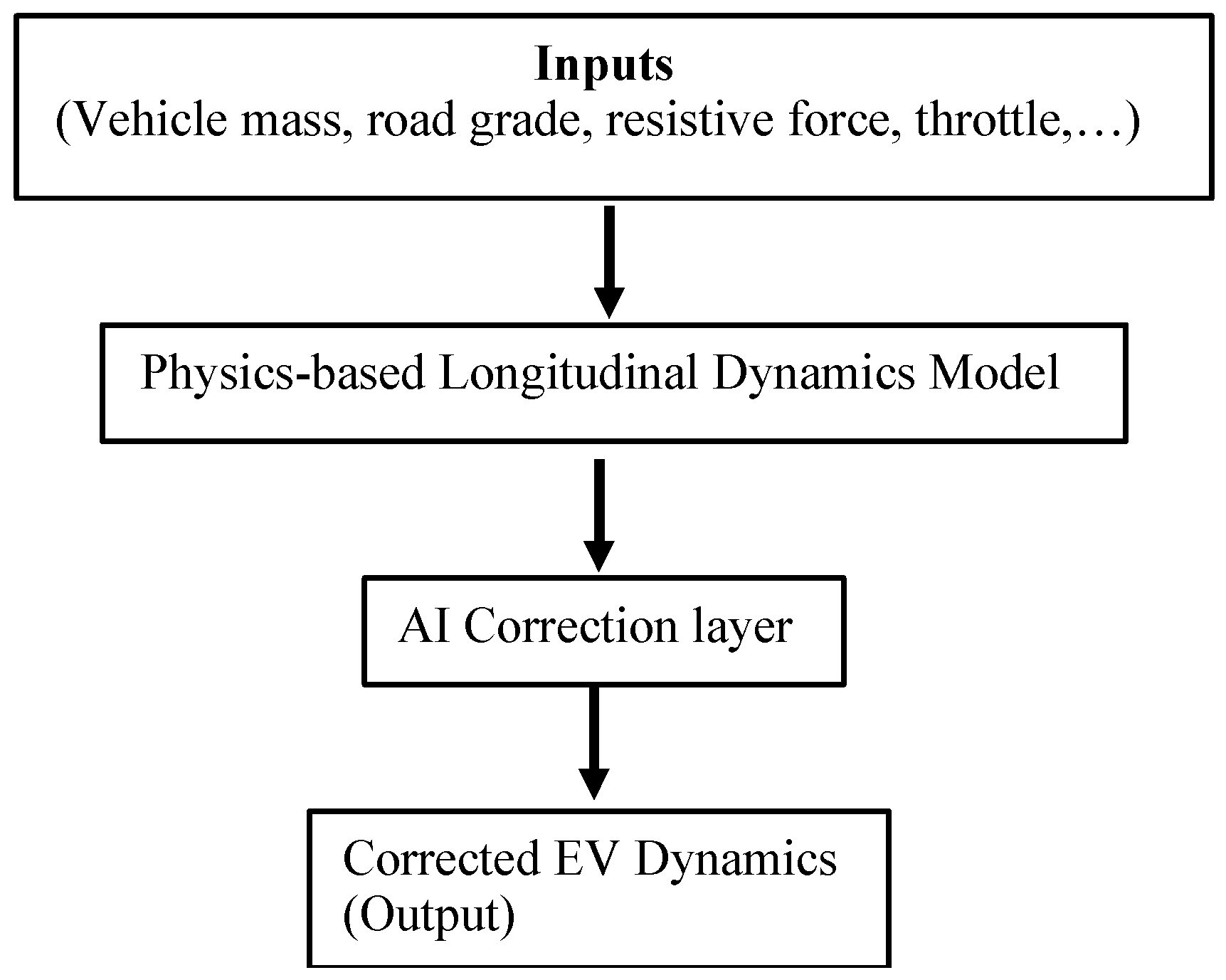

This diagram

Figure 5 illustrates a system for correcting EV dynamics using AI on top of a physics-based model:

Inputs: The system takes various inputs like vehicle mass, road grade, resistive forces, and throttle.

Physics-based Longitudinal Dynamics Model: These inputs are fed into a traditional physics-based model that simulates the vehicle’s longitudinal dynamics.

AI Correction Layer: An AI correction layer is applied to refine the output of the physics-based model, likely addressing discrepancies or improving accuracy in real-world scenarios.

Corrected EV Dynamics (Output): The final output is the corrected EV dynamics, representing a more accurate and robust understanding of the vehicle’s behavior.

6. AI in Electric Vehicle Energy Efficiency

AI Algorithms in the Analysis of Energy Consumption and Energy Efficiency of EVs.

AI has emerged as a transformative tool in the analysis and optimization of energy consumption and energy efficiency in EVs. Traditional physics-based models, while accurate in controlled environments, often struggle to capture the complexity of real-world driving conditions such as variable traffic, road topology, weather, and driver behavior. AI algorithms can address these limitations by learning from large datasets, adapting to uncertainties, and providing real-time predictions.

6.1. Machine Learning Algorithms

Supervised Learning approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RFs), and Gradient Boosted Trees are widely applied to predict energy consumption based on historical trip data. These algorithms map input variables (speed profiles, ambient temperature, battery SoC, route elevation) to energy demand, providing accurate short-term predictions.

SVMs: Effective in nonlinear feature spaces but computationally heavy for large datasets.

RFs & Gradient Boosted Trees: Robust against overfitting and suitable for heterogeneous data, making them common in EV fleet analysis.

Example: RF-based energy models outperform physics-only models in trip-level predictions under mixed traffic conditions.

6.2. Deep Learning Algorithms

DNNs, CNNs, and RNNs/LSTMs are increasingly used for time-series modeling of EV energy consumption.

DNNs: Capture complex nonlinear relationships among vehicle parameters.

CNNs: Extract spatial features from driving maps, road grades, and traffic density to improve energy estimation.

RNNs/LSTMs: Model temporal dependencies in driving cycles, enabling more precise range predictions over long trips.

Example: LSTM-based models outperform traditional regression by accounting for sequential speed variations in urban traffic.

6.3. Reinforcement Learning (RL)

RL optimizes EV energy efficiency by dynamically adjusting control policies such as acceleration, regenerative braking, and eco-routing.

Model-Free RL (Q-learning, Deep Q-Networks): Learn optimal driving strategies without explicit knowledge of vehicle physics.

Model-Based RL: Incorporates simplified dynamics for faster convergence and better generalization.

Applications:

Eco-driving assistants that suggest speed and braking patterns.

Energy-efficient route planning integrating traffic, elevation, and charging station availability.

6.4. Hybrid AI–Physics Models

Combining AI algorithms with physics-based models offers both interpretability and adaptability. AI corrects residual errors in physical models, while physics provides constraints that prevent unrealistic predictions.

Grey-box models: Hybrid approaches where physics provides the backbone and ML adjusts parameters dynamically.

Transfer Learning: AI models trained on one vehicle type can be adapted to others with fewer data requirements.

6.5. Challenges and Research Directions

Despite successes, AI in EV energy analysis faces challenges:

Data Dependence: High-quality, large-scale datasets are required but often proprietary.

Generalization: Models trained on specific vehicles or regions may not generalize globally.

Explainability: Black-box DL models limit trust in safety-critical applications.

Integration: Combining AI predictions with real-time onboard control systems requires lightweight, computationally efficient algorithms.

EVs are increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of sustainable transportation, yet their widespread adoption remains challenged by energy efficiency and range limitations. AI has emerged as a powerful enabler for optimizing EV energy consumption by leveraging real-time data, predictive modeling, and adaptive control mechanisms. AI-driven methods can model complex, nonlinear interactions between driving behavior, environmental conditions, and vehicle dynamics, outperforming conventional physics-based models in terms of accuracy and adaptability [

32].

This diagram

Figure 6 illustrates the role of AI in optimizing various aspects of EVs and their integration with smart grids:

EV Battery Management and Route Optimization: AI enhances battery R&D, manages battery performance (state estimation, charging control, range estimation), and optimizes EV routing based on charging needs.

EV Charging Station (EVCS) Optimization: AI assists in optimal placement of EVCS and manages energy and congestion at charging stations through smart charging strategies.

EV Integration with Smart Grid: AI facilitates Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) and Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) interactions, enabling energy scheduling, addressing battery degradation issues, and modeling consumer charging habits for efficient grid integration.

Overall Control Systems: AI serves as a central intelligence connecting and optimizing the control systems for EVs, EVCS, and smart grid integration, leading to a more efficient and sustainable electric transportation ecosystem.

ML and DL techniques have been extensively applied to enhance EV energy efficiency across multiple domains. For instance, AI models have been deployed to improve eco-driving recommendations, optimize route planning, and predict short-term energy demand [

31]. RL has shown promise in dynamic energy management by continuously adapting power distribution between traction motors, regenerative braking, and auxiliary loads [

58]. Furthermore, AI-powered predictive control has enabled advanced thermal management systems to minimize battery energy loss while maintaining safety and durability [

59].

Another critical application of AI lies in smart charging strategies. By integrating EV energy consumption data with grid conditions, AI algorithms can schedule charging to reduce peak demand, optimize charging cost, and enhance battery lifespan [

60]. Additionally, AI-based digital twins and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication facilitate system-level energy optimization by coordinating multiple EVs within fleets or smart cities [

61].

Despite these advances, challenges remain regarding data availability, generalizability across vehicle types, and real-time deployment of computationally intensive models. Addressing these barriers will require hybrid approaches that integrate AI with physics-based constraints, as well as standardized frameworks for data sharing and model validation [

6]. Nevertheless, AI has proven to be a transformative tool in improving EV energy efficiency and accelerating the transition toward sustainable mobility.

Future directions include federated learning for privacy-preserving fleet data analysis, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) for better interpretability, and RL for real-time adaptive eco-driving.

7. Data Collection for EV Energy Consumption Analysis

Data collection forms the cornerstone of accurate energy consumption analysis in EVs. Effective collection, preprocessing, and integration of multi-source data enable researchers and practitioners to model consumption under diverse real-world conditions. Unlike laboratory experiments that provide controlled insights, real-world data acquisition accounts for variability in driving behavior, road topology, traffic conditions, and environmental influences [

62]. The accuracy and reliability of EV energy models depend heavily on the quality and comprehensiveness of collected datasets.

Data Sources

Data collection for EV energy consumption typically integrates three main categories:

- ◦

Vehicle-Embedded Sensors and CAN Bus Data

Modern EVs are equipped with a CAN bus, which records high-frequency signals, including speed, torque demand, current, voltage, and SoC [

63]. This data provides granular insights into the energy consumption profile of individual trips.

- ◦

External Environmental and Contextual Data

Weather Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and road infrastructure databases supply information about temperature, humidity, wind, road grade, and traffic conditions. For example, cold temperatures increase auxiliary loads for cabin heating, which may elevate energy consumption by up to 30% in winter climates [

64].

- ◦

Geospatial and Route Data

GPS traces and geographic information system (GIS) layers capture route geometry, elevation profiles, and stop–go traffic dynamics. These data streams are vital for understanding consumption variations across urban, highway, and mixed driving conditions [

65].

Data Preprocessing

Collected raw data often suffers from missing values, noise, and synchronization issues. Preprocessing typically involves:

Data cleaning (removal of outliers, filling gaps),

Resampling and alignment (synchronizing different sampling frequencies, e.g., CAN vs. GPS), and

Feature engineering (deriving higher-order metrics such as regenerative braking efficiency or powertrain losses).

Importance for Modeling and Prediction

Comprehensive datasets enhance the robustness of both physics-based and data-driven models. For instance, integrating CAN bus data with external environmental variables significantly reduces prediction error in ML models for energy consumption [

66]. Furthermore, high-resolution route data allows eco-routing algorithms to optimize path selection based on predicted energy demand.

Figure 7 shows EV energy consumption data collection framework as AI is revolutionizing data collection for EV energy consumption analysis by improving data quality, enhancing feature extraction, and enabling predictive insights. These capabilities are pivotal for designing efficient, sustainable EV ecosystems.

Accurate data collection is key in the analysis the energy consumption and efficiency of EVs. With the proliferation of advanced sensors, telematics, and connected infrastructures, AI has emerged as a transformative tool to process, refine, and optimize heterogeneous data streams. This section discusses how AI-driven data collection frameworks enhance the granularity, accuracy, and predictive utility of EV energy consumption analysis.

Energy consumption in EVs is influenced by complex, interdependent factors such as driving behavior, traffic conditions, terrain, vehicle load, and climate control systems [

67]. Traditional data acquisition methods, primarily relying on on-board diagnostics (OBD-II) or standardized driving cycles, often fail to capture the variability of real-world conditions [

61,

68]. Recent advancements in IoT, vehicular networks, and AI-enabled data processing provide unprecedented opportunities for real-time, high-fidelity data collection.

AI techniques, including ML and DL, are increasingly integrated into data pipelines to ensure adaptive filtering, feature extraction, and anomaly detection [

30]. This enables not only accurate modeling of EV energy demand but also the development of intelligent energy management systems (EMS) that improve efficiency.

7.1. AI-Enhanced Data Collection Framework

AI contributes to EV data collection through three primary mechanisms:

Sensor Fusion and Preprocessing—Multiple heterogeneous sensors (CAN bus, GPS, accelerometers, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), weather stations) generate large datasets. AI algorithms filter noise, synchronize signals, and integrate multi-modal data [

69].

Dynamic Feature Extraction—Instead of relying solely on static datasets, AI models learn contextual patterns such as speed fluctuations, road gradient, and ambient temperature to derive energy-relevant features [

31].

Anomaly and Fault Detection—AI-driven monitoring detects irregularities in battery voltage, regenerative braking performance, or charging efficiency, which are critical for accurate energy modeling [

70].

7.2. Case Applications

Eco-Routing Systems: AI-enhanced data collection supports dynamic route optimization, minimizing energy usage based on predictive models [

71].

Battery Health Monitoring: Continuous data-driven analysis enables early detection of degradation patterns, improving both safety and efficiency [

72].

Predictive Energy Demand Modeling: ML models use real-time data to estimate trip-level consumption, outperforming traditional physics-only models [

73].

7.3. Challenges and Future Directions

While AI strengthens EV data collection, several challenges remain:

Future directions include federated learning for decentralized data collection and edge-AI deployment to reduce latency and improve scalability.

Here is a conceptual framework (

Figure 8) for AI-enabled Data Collection in EV Energy Consumption Analysis:

Data Sources: CAN bus, GPS, accelerometer, weather, traffic, charging infrastructure.

AI Processing Layer: Sensor fusion → Feature extraction → Anomaly detection → Prediction models.

Applications: Eco-routing, battery health monitoring, energy efficiency optimization.

8. AI in Electric Vehicle Battery State of Charge Estimation

8.1. The Principle

Accurate estimation of the State of Charge (SoC) is critical for the safe, reliable, and efficient operation of EVs. Traditional model-based techniques, such as Coulomb counting and equivalent circuit models (ECM)

, often suffer from cumulative errors, dependency on initial conditions, and sensitivity to battery aging effects [

75]. To address these challenges, AI techniques—including ML, DL, and hybrid physics-informed methods—are increasingly adopted for SoC estimation.

ML approaches such as support vector regression (SVR), Gaussian process regression (GPR), and random forests (RF) have demonstrated superior generalization capabilities under varying load and environmental conditions [

76]. These methods learn nonlinear input-output mappings from historical voltage, current, and temperature data, thereby improving accuracy compared to traditional observers and Kalman filters.

DL architectures, including LSTM and CNNs, have shown significant promise in modeling the temporal dependencies of battery signals [

77]. LSTMs are particularly effective in capturing long-term sequence patterns in current and voltage time series, which are crucial for dynamic SoC estimation under real-world driving cycles. CNNs, on the other hand, enable efficient feature extraction from multi-dimensional sensor inputs, supporting real-time estimation [

78].

Recent research highlights the potential of hybrid physics-informed AI models, which combine ECM or electrochemical models with DL networks to constrain predictions within physically plausible limits [

20]. This integration enhances robustness, interpretability, and adaptability to battery degradation. Furthermore, RL methods are emerging to optimize online SoC estimation strategies in real-time control systems [

79].

The adoption of AI-driven SoC estimation not only improves range prediction accuracy but also enhances battery management system (BMS) efficiency, thermal management, and overall EV reliability. These advancements are expected to play a pivotal role in addressing range anxiety and accelerating EV adoption worldwide.

The diagram

Figure 9 shows the AI-based SoC estimation framework with the flow from inputs → AI model → SoC output → BMS integration.

Estimating Battery State of Charge (SoC) in EVs is crucial for range prediction, energy management, and driver confidence. While AI methods (ML, DL, hybrid models) have shown promise compared to physics-based and equivalent circuit models, several issues and challenges remain.

Key Issues with AI in EV SoC Estimation

AI improves SoC estimation by handling nonlinearities, dynamic conditions, and sensor noise, but struggles with data availability, generalization, battery aging, explainability, and real-time deployment. A promising direction is hybrid models that integrate physics-based approaches with AI to achieve accuracy, robustness, and interpretability.

Diagram/figure showing the AI-based SoC estimation pipeline (data → AI model → SoC prediction → feedback with battery).

Data Dependence & Quality

- ◦

AI models require large, high-quality datasets (voltage, current, temperature, usage patterns).

- ◦

EV battery data is often proprietary, incomplete, or inconsistent across different manufacturers.

- ◦

Noise in real-world data (sensor drift, communication errors) can reduce accuracy.

Generalization & Transferability

- ◦

AI models trained on one battery chemistry (e.g., Li-ion NMC) or vehicle model may not generalize well to others.

- ◦

SoC estimation performance often degrades under unseen conditions (extreme temperatures, fast charging, aging effects).

Battery Aging & Degradation

- ◦

Battery internal resistance, capacity, and electrochemical properties change with aging.

- ◦

AI models may fail to adapt unless continual learning or online updating is integrated.

Explainability & Trust

- ◦

Many AI approaches (e.g., DNNs) are black-box models, making it difficult to understand why a certain SoC estimate is produced.

- ◦

Lack of explainability limits adoption in safety-critical automotive applications where verification and certification are mandatory.

Real-Time Constraints

- ◦

SoC estimation must be fast and computationally efficient for onboard use.

- ◦

Some advanced AI models (e.g., LSTMs, transformers) are computationally heavy, straining low-power automotive controllers.

Overfitting & Robustness

- ◦

AI models can overfit to specific driving/charging profiles in training data.

- ◦

Performance may drop under dynamic driving cycles (urban stop-and-go vs. highway), different users, or varying climates.

Integration with Physics Models

- ◦

Pure AI models sometimes ignore the physical constraints of batteries.

- ◦

Hybrid approaches (physics-informed AI) are emerging, but balancing data-driven flexibility with physical consistency remains a challenge.

Safety & Reliability Concerns

- ◦

Incorrect SoC estimation can lead to range anxiety, unexpected shutdowns, or battery over-discharge/over-charge risks.

- ◦

Automakers require robust fault tolerance, which AI models must prove before large-scale adoption.

8.2. Data Learning Applications in State of Charge (SoC) Evolution of EVs

8.2.1. Overview

Accurate estimation of the SoC of an EV battery is essential for reliable range prediction, energy management, and battery life extension. This study employs a hybrid data-driven and model-based approach integrating Coulomb counting, Extended Kalman Filtering (EKF), and Neural Network (NN)-based data learning to enhance SoC prediction accuracy under varying driving conditions.

8.2.2. Coulomb Counting Method

The Coulomb counting method estimates the SoC by integrating the current over time, representing the balance between charge and discharge processes. The fundamental relationship is given by:

where

SoC(t) is the state of charge at time t,

Cn is the nominal capacity of the battery (Ah),

I(τ) is the instantaneous current (A), positive during discharge, negative during charge.

However, this approach is sensitive to current sensor bias and integration drift, motivating its fusion with model-based estimators.

8.2.3. Extended Kalman Filter for SoC Estimation

The EKF is implemented to fuse measurements (voltage, current, temperature) with a battery model, compensating for measurement noise and model uncertainty. The dynamic equations for the nonlinear battery system are expressed as:

where

xk = [SoCk,VRC,k]T is the state vector (SoC and RC circuit voltage),

uk = Ik is the input (current),

yk = Vk is the measured terminal voltage,

wk, are process and measurement noise with covariances Qk, Rk.

The prediction and update steps are as follows:

Update:

where F

k and H

k are Jacobians of f(⋅) and h(⋅), linearized about the current state.

8.2.4. Neural Network Data Learning for SoC Evolution

A neural network model is trained to learn nonlinear dependencies between sensor inputs (I,V,T) and true SoC evolution. The model aims to minimize prediction error while compensating for drift in Coulomb counting and bias in model-based estimation.

Let the dataset be {(Xi,yi)}i=1N, where Xi = [Ii,Vi,Ti,ti] and yi = SoCi.

The NN estimates SoC as:

where

fθ is a neural network parameterized by weights

θ.

The objective function for supervised learning is the Mean Squared Error (MSE):

To enhance robustness, a regularization term is added:

where

λ is the weight decay coefficient.

Optimization is performed using the Adam optimizer, with early stopping based on validation error.

8.2.5. Fusion Strategy

The final SoC estimate combines outputs from Coulomb Counting (CC), EKF, and NN through a weighted fusion:

where α, β ∈ [0, 1] are optimized empirically to minimize overall estimation error under diverse drive cycles (e.g., UDDS, WLTC).

8.2.6. Suggested Hyperparameter Configuration

Table 4 shows the suggested hyperparameter configuration.

8.2.7. Evaluation Metrics

Performance is assessed using:

Experimental validation is conducted using real EV drive cycles with synchronized voltage, current, and temperature data.

8.2.8. Implementation

All models can for example be implemented in Python 3.9 (PyTorch, NumPy) and executed on a Tesla V100 GPU platform. The EKF model is integrated with the data pipeline using SciPy’s nonlinear solvers, enabling real-time sequential data learning for SoC evolution.

Below is listed the main technical challenges when SoH information is included inside a deep-learning SoC estimator for EVs, the explanation of why each matters, and practical mitigations/design choices that can be used (architectures, data, training tricks, runtime constraints).

Key challenges

Strong coupling between SoC and SoH—as capacity fades (SoH↓) the mapping from measured voltage/current/temperature to SoC changes. A model trained on “fresh” cells will mis-predict SoC on aged cells unless you explicitly model SoH or adapt [

80].

Label scarcity and noisy ground truth—accurate SoC and SoH labels require controlled lab tests (full charge/discharge cycles, coulomb counting baseline, capacity tests, or EIS). Large, diverse labelled datasets covering cells, chemistries, temperatures, and real driving profiles are rare [

72].

Non-stationarity / domain shift (aging, environment, duty cycle)—the battery’s electrochemical behavior drifts with calendar/cycling aging and different usage (fast charge, regen, temperature). Models must handle distribution shift between training and deployment [

62].

Confounding factors (temperature, load, hysteresis, relaxation)—the same SoC at different temperatures or after different current histories produces different voltages; aging changes internal resistance and open-circuit voltage curves—these interactions complicate direct mapping [

81].

Heterogeneous fleets & cell variability—cell manufacturer differences, pack balancing, and cell-to-cell variability mean a model trained on one pack may not generalize to another [

72].

Real-time constraints & BMS compute—BMS hardware has limited CPU/memory; large DL models or heavy inference pipelines (e.g., large Transformers) may be infeasible without compression or edge/cloud partitioning [

81].

Explainability & safety/regulatory requirements—SoC errors can affect range estimation and safety. Black-box DL without uncertainty estimates or explainability is risky for certification [

82].

Simultaneous estimation tradeoffs—joint SoC–SoH estimation is attractive but raises multi-task tradeoffs: naively training one network can let one task dominate the loss and hurt the other. Proper loss balancing and architecture are required [

83].

Imbalanced ageing modes/long-tail events—rare but critical conditions (rapid degradation modes, cell faults) are underrepresented in training data yet they are the ones you most need the model to recognize [

72].

Measurement noise & sensor quality—current/voltage/temperature sensors on vehicles are noisy, quantized, and sometimes delayed; models must be robust to this [

81].

Short list of promising research directions/low-hanging fruit

Physics-informed DL to improve extrapolation to unseen aging regimes [

84].

Transfer learning across chemistries/packs (pretrain on large lab datasets, fine-tune per fleet) [

72].

Active fleet learning (send only high-uncertainty episodes for lab testing) to address long-tail events [

85].

Multimodal SOH signals (voltage curves + EIS + impedance features) fused with DL for stronger SOH cues [

62].

9. AI in EV Driving Behavior and Patterns for Energy Consumption and Efficiency

9.1. The Principle

The relationship between acceleration and energy consumption in EVs can be expressed with a square dependence because the power demand grows with the square of acceleration.

To accelerate, an EV must produce a tractive force F proportional to the acceleration a:

where m is the vehicle mass.

The power demand P is then:

where v is velocity.

Since energy consumption over a time interval is the integral of power, and acceleration strongly influences v, the instantaneous energy consumption can be approximated as quadratic in acceleration:

Simplified Dependence

Thus, we can express the energy consumption as:

where k is a proportionality constant depending on the vehicle mass, efficiency, drivetrain, and driving conditions.

This is why aggressive driving (high acceleration) significantly increases energy consumption compared to smooth driving (low acceleration).

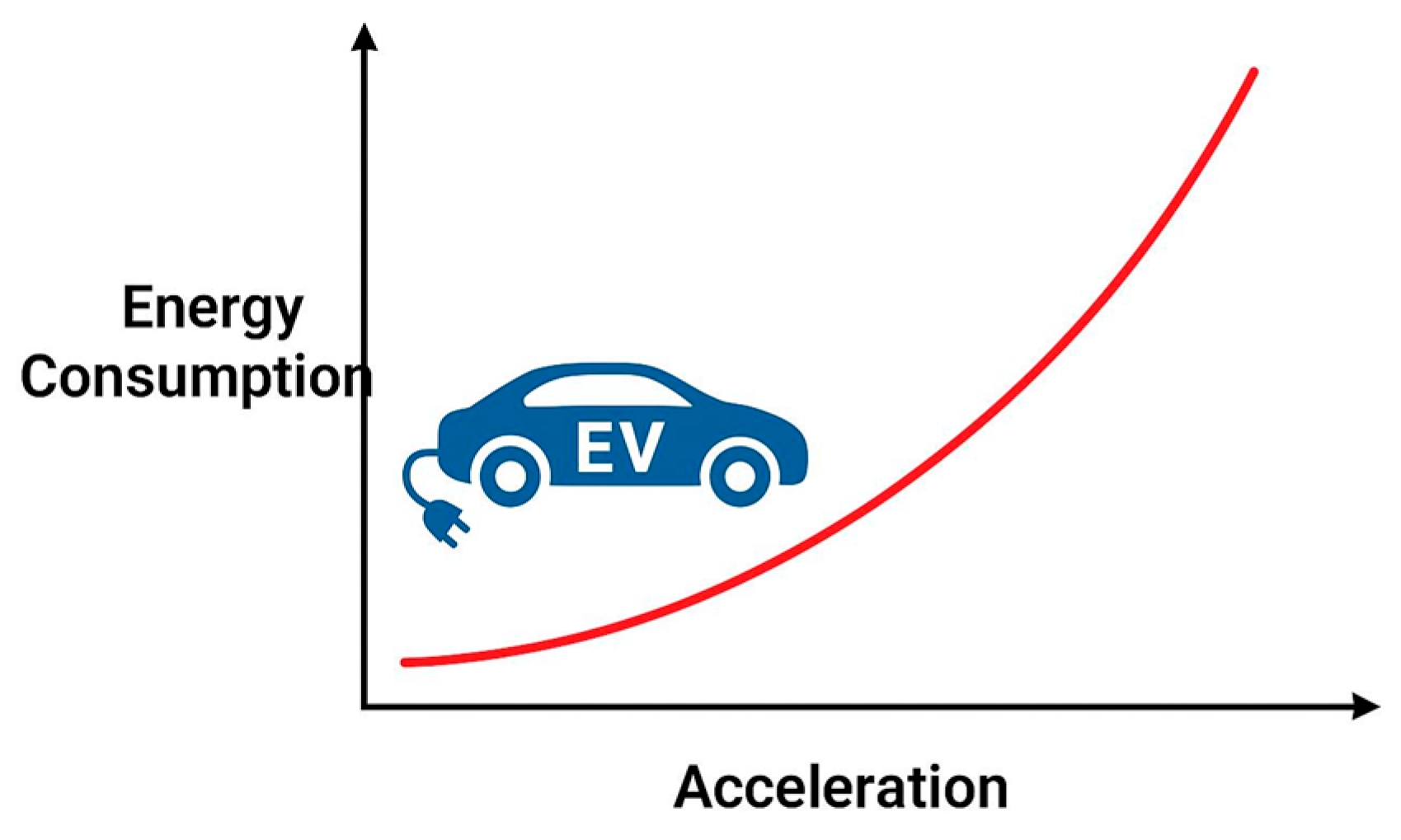

Illustrative plot

Figure 10 shows synthetic energy consumption vs. acceleration from smooth (eco) to aggressive driving equivalent to high acceleration. The plot demonstrates the U-shaped acceleration dependence and the consistent energy penalty associated with aggressive driving.

Driving behavior and traffic patterns are critical determinants of the energy consumption and efficiency of EVs. Unlike ICEVs, EVs exhibit highly nonlinear relationships between driving dynamics, battery performance, and energy use, making conventional rule-based estimations less accurate. AI techniques, particularly ML and DL, have shown significant potential in analyzing driver behavior, predicting energy demand, and optimizing driving strategies for improved efficiency.

Driving behavior including acceleration, braking frequency, route selection, and speed variation directly affects battery discharge rates and regenerative braking efficiency [

86]. For instance, aggressive acceleration and frequent stop-and-go patterns in urban driving conditions significantly increase energy consumption compared to smoother driving behaviors [

87]. AI-driven behavioral models use data from vehicle sensors, GPS, and telematics to detect and classify driving styles, enabling real-time prediction and personalized eco-driving recommendations [

88].

Pattern recognition methods such as CNNs and RNNs have been employed to model temporal dependencies in driver behavior, extracting latent features that correlate with energy efficiency [

89]. For example, recurrent architectures like LSTMs can capture long-term driving habits to forecast trip-level energy use under varying traffic and environmental conditions [

90]. Furthermore, RL approaches have been adopted to optimize real-time driving decisions such as throttle input and regenerative braking levels toward minimizing total energy expenditure [

91].

AI systems also enable integration of large-scale traffic and mobility data to contextualize driving patterns within real-world operating conditions. By fusing driver-specific profiles with external factors such as congestion levels, road grade, and weather conditions, AI can provide holistic energy consumption models that outperform purely physics-based approaches [

92]. Such models are being applied in eco-routing systems that recommend energy-efficient routes tailored to individual driving behavior, yielding energy savings of up to 15% [

93].

Overall, AI-driven analysis of driving behavior and patterns represents a transformative approach to enhancing EV efficiency. By leveraging real-world behavioral data, adaptive learning, and predictive analytics, these models not only improve accuracy in consumption forecasting but also actively guide drivers and fleets toward sustainable practices.

AI methods play a central role in quantifying and acting on the coupling between driving behavior and EV energy use. Combining domain knowledge (vehicle physics) with flexible data-driven models offers the best tradeoff between accuracy and generalization for practical systems (eco-coaching, range prediction, fleet optimization).

Understanding driver behavior and its relation to energy consumption is critical for maximizing EV range, improving energy efficiency, and designing driver assistance and fleet management systems. AI enables the extraction of meaningful patterns from vehicle telematics (CAN bus), GPS traces, and environmental/contextual data (traffic, road geometry, weather) and can predict instantaneous or trip-level energy use, infer driving styles, and recommend energy-efficient actions.

9.1.1. Data Sources and Feature Engineering

Typical inputs:

Vehicle bus data: instantaneous power, current, voltage, motor torque, gear state, regenerative braking events.

GNSS/GPS: speed, heading, elevation, trip length, stop/start events.

Inertial sensors: acceleration, jerk, yaw rates critical to quantify driving aggressiveness.

External/contextual: traffic density, road grade, ambient temperature, weather, speed limits, time of day.

Feature engineering commonly extracts:

Statistical features: mean/median/max/min speed, acceleration percentiles.

Time-series features: spectral or wavelet descriptors, autocorrelation lags.

Event counts: number of harsh brakes/accelerations, stop durations.

Route features: average gradient, road type mix (urban/highway), intersection density.

9.1.2. Modeling Approaches

Supervised regression: Random Forests, Gradient Boosting (XGBoost/LightGBM), and neural networks (MLP (MultiLayer Perception), CNNs on spectrograms, LSTMs/Transformer encoders for sequences) predict energy per km or trip energy.

Sequence models: LSTM/CNN–LSTM or Transformer architectures model temporal dependencies for instantaneous power prediction.

Clustering/Unsupervised: k-means, hierarchical clustering, and Gaussian mixture models identify driving style archetypes (e.g., calm, normal, aggressive).

Hybrid physics + ML: combine physics-based vehicle energy models (rolling resistance, aerodynamic drag, powertrain efficiencies) with ML corrections for unmodeled effects and driver behavior.

RL: for eco-driving policies (e.g., speed profiles, predictive regenerative braking) that directly optimize energy objectives subject to driving constraints.

9.1.3. Evaluation Metrics and Validation

Key metrics:

Trip-level: mean absolute error (MAE) Wh/km, RMSE Wh, relative error (%).

Instantaneous-level: RMSE of instantaneous power (W), time-aligned error metrics.

Driver/style classification: accuracy, F1, confusion matrices.

Validation strategies: cross-vehicle, cross-route holdouts, and temporal splits to test generalization across drivers, vehicle models, and routes.

9.1.4. Insights: How Driving Patterns Affect Energy and Efficiency

Aggressive driving (high peak accelerations, frequent speed changes) increases energy consumption through larger kinetic energy losses and less opportunity for regenerative braking.

Smooth driving reduces peak power demands, allows more effective regenerative braking, and keeps the drivetrain within efficient operating points.

Speed dependence: energy per km often presents a U-shaped dependence on average speed: high at very low speeds (stop-and-go losses) and high at high speeds (aerodynamic drag). Driving style shifts this curve up or down.

Regenerative braking & route topology: effective regeneration depends on traffic and route profiles; hilly routes can be energy-neutral or beneficial if regen is captured, but aggressive uphill accelerations hurt efficiency.

Temperature & auxiliaries: HVAC and battery thermal management can substantially affect energy use; driver choices (e.g., preconditioning, window use) interplay with driving behavior.

9.1.5. Applications and Systems

Personalized energy prediction: models that adapt to driver-specific patterns achieve better range estimation and better route/charge recommendations.

Eco-driving assistance: real-time feedback or AR/HUD (Augmented Reality / Heated Up Display) cues to reduce accelerations and smooth throttle.

Fleet management: driver scoring and coaching to reduce energy costs across fleets.

Energy-aware routing: recommending routes that minimize energy rather than distance or time.

9.1.6. Practical Considerations & Challenges

Data privacy and labeling: linking telematics to drivers must respect privacy; ground truth energy measurements require careful synchronization.

Generalization: models trained on one vehicle type may not transfer to another due to different mass, aero, and powertrain efficiencies.

Interpretability: fleet operators often prefer explainable models for driver coaching and regulatory compliance.

Integration with physics: pure data models can be brittle; hybrid models combine domain knowledge for robustness.

9.2. Integration of Driving Behavior in AI-Based Energy Consumption Analysis for EVs

Driving behavior significantly influences the energy consumption of EVs, introducing variability that cannot be fully explained by physical models alone. Traditional energy models rely primarily on vehicle dynamics, road grade, and ambient conditions, while AI-based models can incorporate behavioral and contextual data—such as acceleration aggressiveness, braking frequency, route choice, and traffic interaction—into energy prediction frameworks [

94,

95]. This integration enhances the model’s ability to generalize across diverse driving contexts and user profiles.

AI-based inclusion of driving behavior enables adaptive and personalized EV energy consumption prediction, bridging the gap between driver variability and physical modeling. Future work should integrate federated learning to preserve driver privacy and expand behavioral clustering for personalized eco-driving recommendations.

9.2.1. Feature Representation of Driving Behavior

Driving behavior is quantified through telematics data collected from onboard sensors (CAN bus, GPS, IMU). Common behavioral features include:

Acceleration Patterns: Mean and variance of longitudinal acceleration ax and jerk, jx = dax/dt, indicators of aggressive driving.

Braking Intensity: Distribution of negative acceleration events and regenerative

braking ratio

Speed Variability: Coefficient of variation in speed CVv = σv/μv.

Stop-and-Go Frequency: Derived from speed zero-crossings per unit distance.

Route Topology and Traffic Density: Captured through GPS traces and map APIs, influencing driving smoothness.

These features are standardized using z-score normalization before being fed into learning architectures.

9.2.2. AI Model Integration

The driving behavior features are fused with vehicle dynamics and environmental parameters to form the input tensor for AI models. The structure is often multimodal:

where X

veh includes current, voltage, and speed; X

env covers temperature, road grade, and traffic flow; and X

beh represents behavioral indicators.

Neural architectures for behavior-integrated modeling typically include:

The predicted energy consumption Ê is expressed as:

where f

θ represents the parameterized deep model trained on historical energy consumption labels E

t.

9.2.3. Training and Loss Function Design

The learning objective minimizes the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) or RMSE:

For behavior-aware models, an auxiliary behavior regularization term can be added to penalize unrealistic driver patterns:

where λ controls the influence of behavior regularization derived from empirical distributions of driving styles (eco, normal, aggressive).

9.2.4. Model Evaluation and Interpretability

Model evaluation uses cross-driver validation to ensure generalization. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME analysis quantifies the contribution of behavioral features to predicted consumption, revealing that acceleration aggressiveness and stop frequency often dominate [

98]. Real-world deployments show that incorporating driving behavior can reduce energy prediction error by up to 15–25% compared to models without behavioral inputs [

99].

10. Proportion of Operational Energy by Category in EVs Including AI

10.1. Typical Operational Energy Categories

These percentages describe how the battery energy used while driving is commonly partitioned among consumers on the vehicle (ranges vary strongly with temperature, driving pattern, and autonomy level):

Propulsion (motor + drivetrain losses)—≈65–85% of operational energy. This is the dominant use (depends on speed, grade, aerodynamics) [

100].

HVAC (heating, ventilation, air-conditioning, cabin thermal)—≈2–33% (very weather-dependent: low in mild climates, large in extreme cold/hot; some studies show HVAC can approach ~30% or more under real conditions) [

101].

Battery thermal management (cooling/heating battery pack)—≈1–8% (depends on ambient and battery management strategy) [

102].

Auxiliaries (lights, pumps, power steering, windshield, pumps, cabin preconditioning, infotainment baseline)—≈1–8% (lighting/infotainment are small individually but add up) [

103].

On-board electronics, sensors & compute (ECUs, connectivity, Advanced Drier-Assistance Systems (ADAS), perception & AI compute)—≈0.5–20% depending on level of autonomy and computing hardware:

- ◦

For standard consumer BEV (no heavy autonomy): ~0.5–3% (infotainment + body Electronic Control Unit (ECUs) + telematics) [

104].

- ◦

For Level 2 Automation (L2)–L3 ADAS (moderate compute): 5–500 W (small % of battery) [

105].

- ◦

For Full autonomy (L4/L5) with high-power perception stacks (multiple LiDARs/cameras + centralized GPUs/accelerators): hundreds to >1000 W, i.e., ~5–20% (or more in worst case). Recent surveys and measurements report on-board compute budgets in the hundreds to low thousands of watts for full perception/planning stacks [

105].

Rule of thumb: unless the vehicle carries a full autonomy sensor/compute stack, propulsion + HVAC will consume the large majority (≈70–95%) of operational battery energy [

100].

10.2. Example Breakdowns

10.2.1. Typical Passenger EV (Mild Weather, Non-Autonomous)

Assume propulsion dominates; infotainment & ECUs small.

Propulsion: 78%

HVAC (AC moderate): 6%

Battery thermal management: 3%

Auxiliaries (lights, pumps, infotainment baseline): 6%

On-board compute/telemetry (no heavy AI): 1–2%

This matches vehicle modelling studies and auxiliary power surveys [

100].

10.2.2. EV with Heavy On-Board Autonomy Stack (L4 Capability, Active Sensors, Edge AI)

On-board computer and sensors become substantial:

Note: in aggressive cold/heavy HVAC use or very high compute loads, AI + HVAC combined can rival propulsion for short intervals (affecting range noticeably) [

99].