Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- The initial step involves the identification of design strategies that facilitate the transfer of DfMA principles from the context of standard prefabricated elements to individual architecture.

- −

- The subsequent analysis will examine the impact of the aforementioned strategies on three key areas: energy efficiency, emission reduction, and design innovation.

- −

- The third element of the research focuses on the identification of barriers to implementation in relation to digital technologies, the organization of processes, and the design culture within the construction industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage 1—Literature Review

2.1.1. Prefabrication of Timber Construction

2.1.2. Design for CNC Manufacturing of Engineered Wood Structures

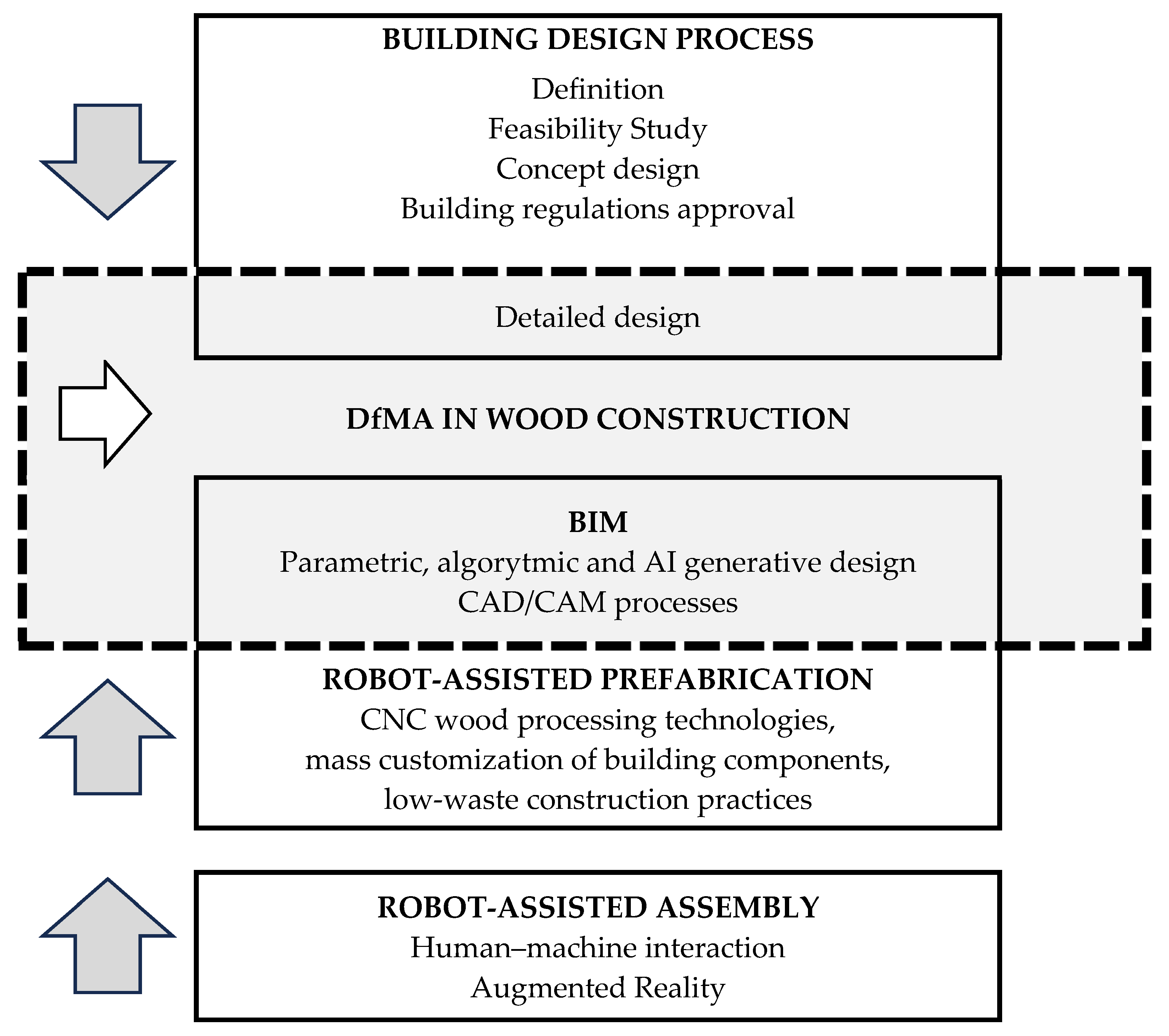

- Integration of DfMA in design engineering practice.

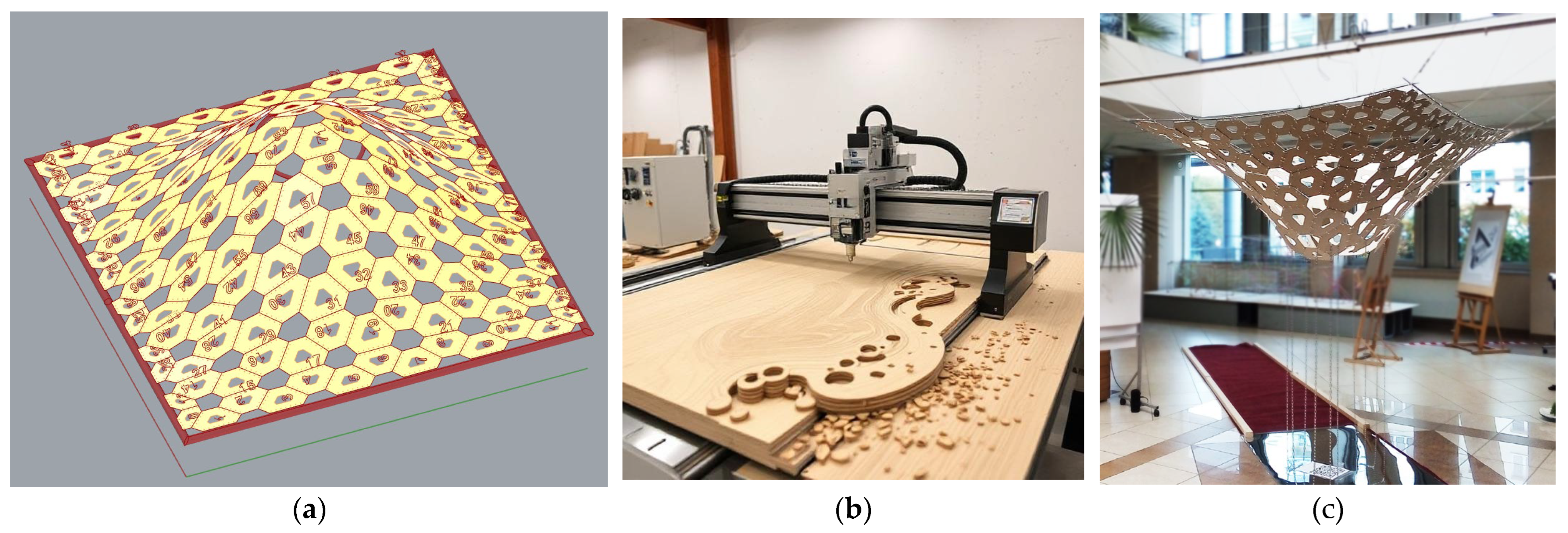

- Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a cornerstone of DfMA, serving as a digital platform that integrates design, manufacturing, and assembly processes. BIM facilitates comprehensive design reviews, construction feasibility assessments, and cost simulations through three-dimensional modeling, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions throughout the project life cycle [16]. By providing a virtual representation of the building, BIM allows for the identification of potential design conflicts and inefficiencies early in the process, reducing errors and rework. This methodology supports the production of prefabricated modules by ensuring designs are optimized for manufacturing and assembly, contributing to cost savings and faster project delivery. For example, BIM has been used to streamline the design of prefabricated non-structural components, such as timber frame walls and plumbing systems, in residential buildings [16]. The integration of BIM with DfMA principles enhances coordination among project stakeholders, improving overall project efficiency and sustainability (Figure 2a–c).

2.1.3. Design of Engineered Wood Structures and Energy Savings

- DfMA and BIM for Sustainable Infrastructure Construction

- Integration of DfMA and BIM for Reductions in On-Site Labor, Materials, Waste, and Carbon Emissions

- Prefabrication Enhancing Carbon Reduction and Infrastructure Sustainability

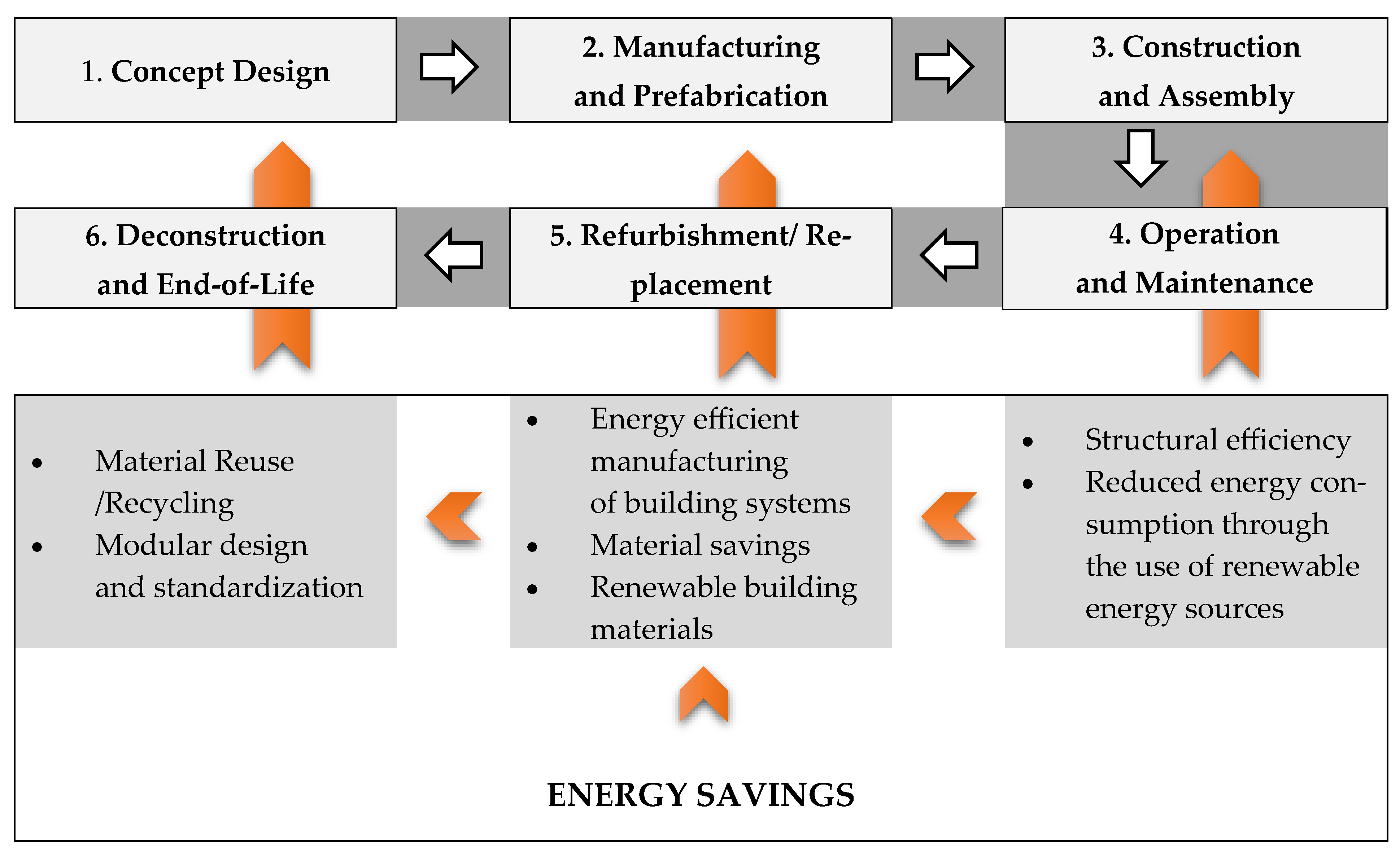

- Life Cycle Stages in Timber Construction: Enhancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality

- Concept Design

- 2.

- Manufacturing and Prefabrication

- 3.

- Construction and Assembly

- 4.

- Operation and Maintenance

- 5.

- Refurbishment/Replacement

- 6.

- Deconstruction and End-of-Life

2.1.4. Parametric Design of Engineered Wood Construction

2.1.5. Environmental Benefits of DfMA

- Shorter Construction Periods and Lower Expenses

- 2.

- Boosted Environmental Sustainability

- 3.

- Promoting Recyclability for a Circular Economy

- 4.

- Reducing Material Waste for Responsible Production

- 5.

- Enhancing Energy Efficiency for Clean Energy and Climate Goals

- 6.

- Enabling Lifecycle Adaptability for Sustainable Innovation

- Superior Quality Assurance;

- Heightened Safety and On-Site Productivity;

- Expanded Design Versatility.

2.1.6. MdFA Principles in Wood Engineering

- Design Simplification: Streamlines component geometries and connections to minimize fabrication errors and material waste, crucial for non-standard forms where complexity can escalate costs.

- Standardization: Introduces repeatable elements like joint types or dimensions amid variability, enabling economies of scale and easier quality control in timber production.

- Modularization: Divides structures into prefabricated units for off-site assembly, improving logistics and reducing on-site time for intricate, non-standard designs.

- Production and Process Optimization: Refines workflows through automation and supply chain integration, boosting overall efficiency and adaptability in realizing custom timber builds.

2.2. Stage 2—Buildings Review

3. Results

3.1. Results of Stage 1—Literature Review

3.1.1. Design Simplification

- Reduced Material Waste: Simplified designs minimize off-cuts and excess material use during CNC fabrication.

- Energy Efficiency: Less complex components require less energy for machining and assembly.

- Recyclability: Simplified wooden parts are easier to disassemble and recycle, supporting a circular economy.

3.1.2. Standardization

- Reduced Material Waste: Standardized components optimize material use, minimizing waste in production.

- Energy Efficiency: Mass production of standard parts reduces energy-intensive custom fabrication.

- Lifecycle Adaptability: Standardized wooden components can be reused or repurposed in other projects, extending material lifecycle.

3.1.3. Modularization

- Reduced Material Waste: Modular units are prefabricated with minimal on-site cutting, reducing waste.

- Energy Efficiency: Off-site fabrication and compact transport of modules lower energy use compared to traditional construction.

- Lifecycle Adaptability: Modular wooden systems allow disassembly and reconfiguration, reducing demolition waste and supporting reuse.

3.1.4. Production and Process Optimization

- Reduced Material Waste: Optimized CNC cutting patterns minimize timber waste.

- Energy Efficiency: Automated CNC processes reduce energy consumption compared to manual fabrication.

- Recyclability: High-precision components ensure quality, reducing rework and enabling easier disassembly for recycling.

3.2. Results of Stage 2—Buildings Review

3.2.1. Non-Standard Structures in Engineering Wood Construction

3.2.2. Application of Parametric Design and CNC Manufacturing in DfMA Sub-Processes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rankohi, S.; Carbone, C.; Iordanova, I.; Bourgault, M. Design-for-Manufacturing-and-Assembly (DfMA) for the Construction Industry: A Review. Modul. Offsite Constr. MOC Summit Proc. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Tan, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Gao, S.; Xue, F. Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) in Construction: The Old and the New. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 17, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Mills, G.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Li, B.; Huang, J. Digital-Enabled Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) in Offsite Construction: A Modularity Perspective for the Product and Process Integration. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2023, 19, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, D.; Lorca, F.; Carpio, M. Using the DfMA Approach in the Early Integration of Actors for the Design of an Industrialized Timber Building—CASE STUDY. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering 2025, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 June 2025; pp. 882–890. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri, S.; Lei, Z.; Odo, N. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Construction: A Holistic Review of Current Trends and Future Directions. Buildings 2024, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Costin, A. BIM and Ontology-Based DfMA Framework for Prefabricated Component. Buildings 2023, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widanage, C.; Kim, K.P. Integrating Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) with BIM for Infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2024, 167, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, C.L.C.; Bautista, C.R.; Dela Cruz, O.G.; Dela Cruz, R.L.C.; De Pedro, J.P.Q.; Dungca, J.R.; Lejano, B.A.; Ongpeng, J.M.C. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) and Design for Deconstruction (DfD) in the Construction Industry: Challenges, Trends and Developments. Buildings 2023, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, B.; Fingrut, A.; Li, J. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) of Standardized Modular Wood Components. Technol. Archit. Des. 2023, 7, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, S.; Chenaghlou, M.R.; Rahimian, F.P.; Edwards, D.J.; Dawood, N. Integrated BIM and DfMA Parametric and Algorithmic Design Based Collaboration for Supporting Client Engagement within Offsite Construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuvayanond, W.; Prasittisopin, L. Design for Manufacture and Assembly of Digital Fabrication and Additive Manufacturing in Construction: A Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Wettling, C.; Mourgues Alvarez, C.; Guindos Bretones, P. IDM for the Conceptual Evaluation Process of Industrialized Timber Projects. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankohi, S.; Bourgault, M.; Iordanova, I.; Carbone, C. Towards Integrated Implementation of IPD and DFMA for Construction Projects: A Review. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 27 July 2022; pp. 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Krigsvoll, G.; Johansen, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Carbon Emission of Global Construction Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, B. Structural Materials. In The Ecology of Building Materials; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 199–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wasim, M.; Vaz Serra, P.; Ngo, T.D. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly for Sustainable, Quick and Cost-Effective Prefabricated Construction–a Review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 3014–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, O.; Warman, E.A.; Tilley, S. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly: Concepts, Architectures and Implementation; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Jin, R.; Lu, W. Design for Manufacture and Assembly in Construction: A Review. Build. Res. Inf. 2020, 48, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D. Building Materials Made of Wood Waste a Solution to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Materials 2021, 14, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyanov, S.; Lukina, A.; Tuzhilova, M. Transformation of the Role of Wood as a Building Material. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Materials Physics, Building Structures & Technologies in Construction, Industrial and Production Engineering–MPCPE; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dukarska, D.; Mirski, R. Wood-Based Materials in Building. Materials 2023, 16, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub-French, S.; Poirier, E.A.; Calderon, F.; Chikhi, I.; Zadeh, P.; Chudasma, D.; Huang, S. Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) for Mass Timber Construction; BIM TOPiCS Research Lab, University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Monier, V.; Bignon, J.C.; Duchanois, G. Use of Irregular Wood Components to Design Non-Standard Structures. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 671, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, C.; Zhang, W. DfMA: Towards an Integrated Strategy for a More Productive and Sustainable Construction Industry in Australia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Design for Manufacture and Assembly-Oriented Parametric Design of Prefabricated Buildings. Autom. Constr. 2018, 88, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, R.; Habermann, K.J. Energy-Efficient Architecture: Basics for Planning and Construction; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thiede, S. Energy Efficiency in Manufacturing Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Su, C. Measuring Energy Consumption Efficiency of the Construction Industry: The Case of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, E.; Saidur, R.; Mekhilef, S. A Review on Energy Saving Strategies in Industrial Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hořínková, D. Advantages and Disadvantages of Modular Construction, Including Environmental Impacts. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1203, p. 032002. [Google Scholar]

- Jarnehammar, A.; Green, J.; Kildsgaard, I.; Iverfeldt, Å.; Foldbjerg, P.; Hayden, J.; Oja, A. Barriers and Possibilities for a More Energy Efficient Construction Sector. SECURE–Sustainable Energy Communities in Urban Areas in Europe, an Intelligent Energy Europe Project. 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter-Foldbjerg/publication/267205790_Barriers_and_possibilities_for_a_more_energy_efficient_construction_sector/links/547ed6730cf2d2200edeace4/Barriers-and-possibilities-for-a-more-energy-efficient-construction-sector.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Norouzi, M.; Chàfer, M.; Cabeza, L.F.; Jiménez, L.; Boer, D. Circular Economy in the Building and Construction Sector: A Scientific Evolution Analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A. Efficiency in the Construction Industry. In Housing Urban America; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri, S.; Odo, N.; Naqvi, S.A.W.; Lei, Z. Integrating Design for Manufacturing and Assembly Principles in Modular Home Construction: A Comprehensive Framework for Enhanced Efficiency and Sustainability. Buildings 2024, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X. Benefit Evaluation of Energy-Saving and Emission Reduction in Construction Industry Based on Rough Set Theory. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2021, 28, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Chang, W.-S.; Shih, S.-G. Building Massing Optimization in the Conceptual Design Phase. Comput. Aided Des. Appl. 2015, 12, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, L.; Kenny, J.C.; Alexi, E.V.; Chovghi, F.; Mitterberger, D.; Dörfler, K. Building (with) Human–Robot Teams: Fabrication-Aware Design, Planning, and Coordination of Cooperative Assembly Processes. Constr. Robot. 2025, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Tan, T.; Yu, B.; Li, J.; Fingrut, A. AR-Assisted Assembly in Self-Build Construction with Discrete Components. In Proceedings of the 30th EG-ICE International Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering, London, UK, 4–7 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Gu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z. Automatic Assembly of Prefabricated Components Based on Vision-Guided Robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, Q.; Du, J. Robot-Enabled Construction Assembly with Automated Sequence Planning Based on ChatGPT: RoboGPT. Buildings 2023, 13, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D. End of the Line—Approaches and Insights to Timber Waste Management; Ramboll: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- David, M.-N.; Miguel, R.-S.; Ignacio, P.-Z. Timber Structures Designed for Disassembly: A Cornerstone for Sustainability in 21st Century Construction. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Ott, S.; Winter, S. Recycling and End-of-Life Scenarios for Timber Structures. In Materials and Joints in Timber Structures: Recent Developments of Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesnere, G.; Atstaja, D.; Cudecka-Purina, N.; Susniene, R. The Potential of Wood Construction Waste Circularity. Environments 2024, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak-Niedziółka, K.; Starzyk, A.; Łacek, P.; Mazur, Ł.; Myszka, I.; Stefańska, A.; Kurcjusz, M.; Nowysz, A.; Langie, K. Use of Waste Building Materials in Architecture and Urban Planning—A Review of Selected Examples. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.; Olenchuk, A. Life Cycle Assessment and Building Information Modeling Integrated Approach: Carbon Footprint of Masonry and Timber-Frame Constructions in Single-Family Houses. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.; Resler, M.; Koda, E.; Walasek, D.; Vaverková, M.D. Energy Saving and Green Building Certification: Case Study of Commercial Buildings in Warsaw, Poland. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzyk, A.; Donderewicz, M.; Rybak-Niedziółka, K.; Marchwiński, J.; Grochulska-Salak, M.; Łacek, P.; Mazur, Ł.; Voronkova, I.; Vietrova, P. The Evolution of Multi-Family Housing Development Standards in the Climate Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Issues. Buildings 2023, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.; Szlachetka, O.; Jeleniewicz, K.; Piotrowski, M. External Wall Systems in Passive House Standard: Material, Thermal and Environmental LCA Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, P.; Bailis, R.; Dermawan, A.; Kittner, N.; McCord, R. SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy–How Access to Affordable and Clean Energy Affects Forests and Forest-Based Livelihoods. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 206–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Rathore, K. Renewable Energy for Sustainable Development Goal of Clean and Affordable Energy. Int. J. Mater. Manuf. Sustain. Technol. 2023, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardana, J.; Sandanayake, M.; Jayasinghe, J.; Kulatunga, A.K.; Zhang, G. Sustainability Drivers and Sustainable Development Goals-Based Indicator System for Prefabricated Construction Adoption—A Case of Developing Economies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardana, J.; Sandanayake, M.; Zhang, G. Case Analysis of Australian Prefabricated Projects Advancing Sustainability in the Urban Built Environment. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-6569961/v1 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Schröder, P.; Antonarakis, A.S.; Brauer, J.; Conteh, A.; Kohsaka, R.; Uchiyama, Y.; Pacheco, P. SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production–Potential Benefits and Impacts on Forests and Livelihoods. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 386–418. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobadi, M. Implementing Circular Economy Strategies in Prefabricated Timber Construction in Response to Climate Change. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shadravan, A.; Parsaei, H.R. Impacts of Industry 4.0 on Smart Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (IEOM Society); IEOM Society Manila: Manila, Philippines, 2023; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tsavdaridis, K.D.; Katenbayeva, A. Reusable Timber Modular Buildings, Material Circularity and Automation: The Role of Inter-Locking Connections. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 110965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenório, M.; Ferreira, R.; Belafonte, V.; Sousa, F.; Meireis, C.; Fontes, M.; Vale, I.; Gomes, A.; Alves, R.; Silva, S.M.; et al. Contemporary Strategies for the Structural Design of Multi-Story Modular Timber Buildings: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, K. Automated Manufacturing for Timber-Based Panelised Wall Systems. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, J.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. New Paradigms of the Automatic: Robotic Timber Construction in Architecture. In Advancing Wood Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kunic, A.; Angeletti, D.; Marrone, G.; Naboni, R. Design and Construction Automation of Reconfigurable Timber Slabs. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premrov, M.; Žegarac Leskovar, V. Innovative Structural Systems for Timber Buildings: A Comprehensive Review of Contemporary Solutions. Buildings 2023, 13, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filion, M.-L.; Ménard, S.; Carbone, C.; Bader Eddin, M. Design Analysis of Mass Timber and Volumetric Modular Strategies as Counterproposals for an Existing Reinforced Concrete Hotel. Buildings 2024, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, A.; Blanchet, P.; Lehoux, N.; Cimon, Y. Collaboration Enables Innovative Timber Structure Adoption in Construction. Buildings 2018, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; Menges, A. Icd/Itke Research Pavilion: A Case Study of Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Computational Design. In Proceedings of the Computational Design Modelling: Proceedings of the Design Modelling Symposium Berlin 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Menges, A.; Knippers, J. Architecture Research Building: ICD/ITKE 2010–2020; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Menges, A. Design Computation and Material Culture. In Lineament: Material, Representation and the Physical Figure in Architectural Production; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Knippers, J.; Kropp, C.; Menges, A.; Sawodny, O.; Weiskopf, D. Integrative Computational Design and Construction: Rethinking Architecture Digitally. Civ. Eng. Des. 2021, 3, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinand, Y. Innovative Timber Constructions. J. Int. Assoc. Shell Spat. Struct. 2009, 50, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gamerro, J.; Bocquet, J.-F.; Weinand, Y. Future Challenges and Need for Research in Timber Engineering. In Proceedings of the 8 th Workshop of COST Action FP1402 “Basis of Structural Timber Design-from Research to Standards”; COST Action: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weinand, Y. Timber Fabric Structures: Innovative Wood Construction. In Advancing Wood Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Willmann, J.; Knauss, M.; Bonwetsch, T.; Apolinarska, A.A.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Robotic Timber Construction—Expanding Additive Fabrication to New Dimensions. Autom. Constr. 2016, 61, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinarska, A.A.; Knauss, M.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. The Sequential Roof. In Advancing Wood Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Krieg, O.D.; Lang, O. Adaptive Automation Strategies for Robotic Prefabrication of Parametrized Mass Timber Building Components. In Proceedings of the ISARC. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction; IAARC Publications: Edinburgh, UK, 2019; Volume 36, pp. 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Apolinarska, A.; Bärtschi, R.; Furrer, R.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Mastering the ‘Sequential Roof’—Computational Methods for Integrating Design, Structural Analysis, and Robotic Fabrication. In Advances in Architectural Geometry 2016; Adriaenssens, M.P.S., Gramazio, F., Kohler, M., Menges, A., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zollikon, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamke, M. CITA: Working for and with Material Performance. Serbian Archit. J. 2013, 13, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.; Tamke, M.; Ayres, P.; Nicholas, P. CITA Works; Riverside Architectural Press: Cambridge, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, M.R. CITA Complex Modelling; Riverside Architectural Press: Cambridge, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carpo, M. Parametric Notations: The Birth of the Non-Standard. Archit. Des. 2016, 86, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatah gen Schieck, A.; Hanna, S. Embedded, Embodied, Adaptive: Architecture and Computation; Emergent Architecture Press (UCL): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sheine, J.; Fretz, M.; O’Halloran, S.; Gershfeld, M.; Stenson, J. Mass Timber Panelized Workforce Housing in Oregon, US; University of Oregon: Eugene, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen, P.; Tidwell, P. Liina Shelter, Wood Program. In The Design-Build Studio; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tidwell, P.; Heikkinen, P. Timber Joints at the Aalto University Wood Program: Designing Through Experimentation. In Rethinking Wood: Future Dimensions of Timber Assembly; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 38–65. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen, P. Wood Program 30 Years. In Proceedings of the Aalto ARTS Student Show; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, J. Parawood: Framework for on-Site Robotic Timber Fabrication. Ph.D. Thesis, Istanbul Bilgi University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gatóo, A.; Ramage, M.H.; Bakker, R. Ephemeral Walls for Natural, Flexible Living. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 1402, p. 012035. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T.; Feldmann, A.; Ramage, M.; Chang, W.-S.; Harris, R.; Dietsch, P. Design Parameters for Lateral Vibration of Multi-Storey Timber Buildings. In Proceedings of the International Network on Timber Engineering Research Meeting 49, Graz, Austria; The University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2016; pp. 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Kacar, E. Robotic Timber Construction-Study on Robotic Fabrication Methods of Computational Designed Timber Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, K.; Eppinger, C.; Rossi, A.; Braun, M.; Brieden, M.; Seim, W.; Eversmann, P. Redefining Material Efficiency: Computational Design, Optimization and Robotic Fabrication Methods for Planar Timber Slabs. In Proceedings of the Design Modelling Symposium Berlin; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 516–527. [Google Scholar]

- Nawari, N. BIM Standardization and Wood Structures. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2012, 2012, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, W.W. Standardization in the Lumber Industry: Trade Journals, Builder’s Guides and the American Home. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tamke, M.; Thomsen, M.R. Designing Parametric Timber. In Proceedings of the 26th eCAADe Conference, Antwerpen, Belgium, 17–19 September 2008; pp. 609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Mork, J.H. Parametric Timber Detailing A Parametric Toolkit Customized for Detailing Fabrication-Ready Timber Structures. 2020. Available online: https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2673875/Mork%20John%20Haddal_PhD.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Stefańska, A.; Cygan, M.; Batte, K.; Pietrzak, J. Applications of Timber and Wood-Based Materials in Architectural Design Using Multi-Objective Optimisation Tools. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K.; Peltokorpi, A.; Lavikka, R.; Seppänen, O. To Prefabricate or Not? A Method for Evaluating the Impact of Prefabrication in Building Construction. Constr. Innov. 2024, 24, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.J.; Alvarez, M.; Groenewolt, A.; Menges, A. Towards Digital Automation Flexibility in Large-Scale Timber Construction: Integrative Robotic Prefabrication and Co-Design of the BUGA Wood Pavilion. Constr. Robot. 2020, 4, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.K.; Winkler, J. Timber Construction in Poland: An Analysis of Its Contribution to Sustainable Development and Economic Growth. Drew. Pr. Nauk. Doniesienia Komun. 2025, 68, 00041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staib, G.; Dörrhöfer, A.; Rosenthal, M. Components and Systems: Modular Construction–Design, Structure, New Technologies; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thajudeen, S.; Elgh, F.; Lennartsson, M. Applying a DFMA Approach in the Redesign of Steel Bracket—A Case Study in Post and Beam System. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 25–31 July 2022; pp. 564–575. [Google Scholar]

- Piętocha, A.; Li, W.; Koda, E. The Vertical City Paradigm as Sustainable Response to Urban Densification and Energy Challenges: Case Studies from Asian Megacities. Energies 2025, 18, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Mills, G.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, K. BIM-Enabled Sustainability Assessment of Design for Manufacture and Assembly. In Proceedings of the 38th ISARC, Dubai, UAE, 2 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Starzyk, A.; Marchwiński, J.; Milošević, V. Circular Wood Construction in a Sustainable Built Environment: A Thematic Review of Gaps and Emerging Topics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunjata, V.; Simanjuntak, M.R.A.; Sulistio, H.; Ardani, J.A. The Implementation of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Indonesian Construction Industry: Major Barriers and Driving Factors. Plan. Malays. 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzyk, A.; Cortiços, N.D.; Duarte, C.C.; Łacek, P. Timber Architecture for Sustainable Futures: A Critical Review of Design and Research Challenges in the Era of Environmental and Social Transition. Buildings 2025, 15, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak-Stępniak, A. The economic advantages of the use of prefabrication technology by developers in the polish housing market. Zesz. Nauk. UPH Ser. Adm. Zarządzanie 2023, 60, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, Z. The Prefabrication of Glued Timber Houses for Residential Construction in Poland. Drew. Pr. Nauk. Doniesienia Komun. 2025, 68, 00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołacz, K. From Structure to Social Fabric: Comparing Participatory and Conventional Residential Design in the Context of Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weththasinghe, K.K.; Wong, P.S.P. Towards Developing Partnership Models for Leveraging Design for Manufacture and Assembly for School Buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Manag. Procure. Law. 2024, 177, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsbrekke, M.H.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; Beitnes, S.; Holm, T.; Meyer-Habighorst, C.; Dudzińska-Jarmolińska, A.; Łatała, K.; Jasińska, K. Thinking with Co-Creation: Meaningful Engagement and Regeneration in Deeper Adaptation to Climate Change. Misc. Geogr. 2025, 29, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages of Building Design Process | DfMA Integration Priority |

|---|---|

| 1. Definition | low |

| 2. Feasibility study | medium |

| 3. Concept design | high |

| 4. Building regulations approval | low |

| 5. Detailed design | high |

| 6. Design of prefabricated building systems | high |

| DfMA Benefit | Related SDG | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement and optimization of processes | SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Optimizes manufacturing and assembly, leading to efficient resource use and sustainable industrialization. |

| Reduced Material Waste | SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Minimizes waste through efficient design and manufacturing processes. |

| Energy Efficiency | SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Reduces energy consumption in production and throughout the prefabricated wooden elements lifecycle. |

| Recyclability | SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Facilitates recycling by designing products that are easy to disassemble and made from recyclable materials. |

| Lifecycle Adaptability | SDG 9 and SDG 12 | Supports SDG 9 by fostering innovation in product design and SDG 12 by extending prefabricated wooden structure life, reducing resource use and waste. |

| Project Name | Year | Architect | Manufacturing Company | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Research Pavilion at University of Stuttgart, Germany | 2012 | University of Stuttgart Institutes ICD/ITKE | Ochs GmbH, Kirchberg, Germany |

| 2. | Church Pavilion “Himmelgrün”, Germany | 2015 | Bayer | |

| 3. | Temporary School Mobi:Space, Trier, Germany | 2018 | GbR Architekten | |

| 4. | Kita Mikado daycare center, Darmstadt, Germany | 2020 | Ramona Buxbaum Architekten | |

| 5. | Sunderland Aquatic Centre, UK | 2011 | RedBoxDesignGroup Architects | Wiehag, Altheim, Austria |

| 6. | Ascent Tower, Milwaukee, USA | 2022 | Korb + Associates Architects | |

| 7. | Gaia Building at NTU, Singapore | 2022 | Toyo Ito & Associates | |

| 8. | Garbe Solid Timber Hall, Straubing-Sand, Germany | 2024 | Köster GmbH (structural); WIEHAG (timber design) | |

| 9. | Fondation Louis Vuitton Museum, Paris, France | 2014 | Frank Gehry | Hess Timber, Kleinheubach, Germany |

| 10. | Bunjil Place, Casey, Australia | 2018 | Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp (FJMT) | |

| 11. | Wooden Sphere Steinberg am See | 2019 | Hess Timber | |

| 12. | Boola Katitjin, Murdoch University | 2023 | Lyons, Silver Thomas Hanley | |

| 13. | The Den, Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, UK | 2019 | Haworth Tompkins | Xylotek, Bristol, UK |

| 14. | ABBA Arena, London, UK | 2022 | Stufish Entertainment Architects | |

| 15. | Osnaburgh Pavilions, Regents Place, London, UK | 2022 | Nex Architecture | |

| 16. | Rafter Walk—Canada Water Boardwalk, London, UK | 2024 | Asif Khan MBE | |

| 17. | Haesley Nine Bridges Golf Clubhouse, South Korea | 2010 | Shigeru Ban | Blumer Lehmann, Gossau, Switzerland |

| 18. | Maggie’s Centre, Manchester, UK | 2016 | Foster + Partners | |

| 19. | Cambridge Mosque, UK | 2019 | Marks Barfield Architects | |

| 20. | Maggie’s Centre, Leeds, UK | 2020 | Heatherwick Studio | |

| 21. | Wisdome Stockholm, Sweden | 2023 | Elding Oscarson |

| Key Focus and Contributions on DfMA of Timber Structures | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| • Biomimetic and computational design for non-standard timber structures, • Testing and evaluating of timber structures (real-life research pavilions), • Robotic fabrication of wood plate morphologies, • Self-shaping wood systems. • Integration of DfMA through co-design methods for multi-storey timber buildings, digital fabrication, and innovative material-efficient techniques. | ICD)/ITKE (University of Stuttgart, Germany) |

| • Computational design and robotic fabrication for non-standard timber structures, such as mono-material wood walls using slit elements for insulation without adhesives or metals. • Integration of DfMA through digital prefabrication, adaptive joining techniques for reclaimed materials, and tools like COMPAS FAB for robotic planning in timber assembly. | Gramazio Kohler Research (ETH Zurich, Switzerland) |

| • Computational architecture and robotic processes for complex, non-standard timber forms, including hybrid material systems and performative structures. Research on DfMA processes of modular, digitally fabricated timber components that support scalable assembly and material efficiency. | Centre for Information Technology and Architecture (CITA, Royal Danish Academy, Denmark) |

| • Conducts research on digital-enabled DfMA in offsite construction, with case studies in prefabricated timber structures using robotic fabrication and parametric modeling (e.g., NURBS in Rhino). Emphasizes modularity, standardized interfaces, and process alignment for non-standard designs to improve efficiency and reduce complexity in timber projects. | Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction (The Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment UCL, UK) |

| • Development and testing of non-standard structural timber innovations with CNC, robotic equipment, and CLT presses • Research of advanced wood products, seismic performance, and DfMA-oriented prefabrication to advance mass timber assembly in sustainable building systems. | TallWood Design Institute (Collaborative between Oregon State University and University of Oregon, USA) |

| • Interdisciplinary hub for wood architecture, structural engineering, and material science, focusing on industrial building with timber. Projects explore non-standard designs through salvaged wood reuse, surface treatments, and Design for Adaptability (closely related to DfMA), promoting holistic prefabrication and assembly strategies for durable, innovative structures. | Wood Program (Department of Architecture, Aalto University, Finland) |

| • Research on on-site parametric robotic fabrication for timber and developing semi-autonomous systems for non-standard house structures. • DfMA of transportable robotic units, AI-interpreted hand-drawn instructions, and prototypes that integrate design, fabrication, and assembly for efficient, carpenter-friendly processes. | Emerging Technologies and Design Research Group (Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark) |

| • Cross-disciplinary research on plant-based materials for zero-carbon architecture, including innovative multi-storey timber structures. • Fluid dynamics, engineering, and design integration to enable DfMA in non-standard forms, • Research on transformation of building practices with sustainable, high-performance timber systems. | Centre for Natural Material Innovation (University of Cambridge, UK) |

| Leading Construction Material/Technology | Count |

|---|---|

| Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) Used in panel systems, walls, floors, and modular construction. | 10 |

| Glued Laminated Timber (Glulam) Used in beams, frames, trusses, and load-bearing structures. | 11 |

| Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) Used in shell structures, beams, CNC-milled elements, and composite shells. | 9 |

| Hybrid systems of CLT + Glulam Combining CLT panels with glulam beams for hybrid structures. | 5 |

| Project Name | Engineered Wood Technology Used in the Project | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Research Pavilion at University of Stuttgart, | CNC-milled Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) with innovative shell structures | bio-inspired morphology for reduced complexity | use of standard plywood and fibers | segmented timber shell | robotic fabrication and molding |

| 2. | Church Pavilion “Himmelgrün” | Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) with prefabricated panel systems | simple elliptical form | glued-laminated beams as standard components | modular structure | efficient timber construction processes |

| 3. | Temporary School Mobi:Space | Lightweight modular timber frame with CLT panels | cubic structure | standard modular units | modular structure | quick assembly optimization |

| 4. | Kita Mikado daycare center | Glulam beams combined with CLT for walls and floors | re-use of elements | standardized components | modular re-used structure | optimized for assembly and re-use |

| 5. | Sunderland Aquatic Centre | Glue-laminated timber (glulam) frames with integrated connections | simple plan layout | standard timber beams | modular roof structure | efficiency of structural system |

| 6. | Ascent Tower | Timber frame with natural wood cladding, likely glulam and solid wood | hybrid structure | standard mass timber elements | prefab mass timber floors | offsite fabrication optimization |

| 7. | Gaia Building at NTU | CNC-cut LVL with parametric design and shell structures | streamlined design | standard mass engineered timber | modular timber components | DFMA and sustainable processes |

| 8. | Garbe Solid Timber Hall | Prefabricated CLT or timber panels for fast onsite assembly | simple hall design | standard timber | modular timber assembly | sustainable construction optimization |

| 9. | Fondation Louis Vuitton | Combination of glulam beams and CLT floor/wall panels | modular design | standard glulam and steel | cladding panels | CNC production |

| 10. | Bunjil Place | Experimental LVL shells with CNC fabrication | interlocking gridshell structure | standard glulam | timber grid shell modular | efficient timber fabrication |

| 11. | Wooden Sphere | Heavy timber frames with glulam and hybrid engineered wood composites | simple spherical form | standard glulam | modular segments | optimized for large scale |

| 12. | Boola Katitjin | Glulam and LVL for bending strength in curved elements | simplified structure | standard mass engineered timber | modular timber elements | efficient mass timber processes |

| 13. | The Den | CLT walls and roof with glulam supports | lightweight design | standard timber | mobile modular auditorium | adaptable assembly |

| 14. | ABBA Arena | Panelized CLT construction for modular, scalable design | simplified structure | standard timber | demountable modules | optimized for relocation |

| 15. | Osnaburgh Pavilions | Hybrid timber structure combining CLT and glulam beams | simplified lattice | standard timber | prefab lattice structure | innovative timber engineering |

| 16. | Rafter Walk | Glulam trusses with LVL secondary framing | winding simple path | standard timber | segmented boardwalk | innovative timber engineering |

| 17. | Haesley Nine Bridges Golf Clubhouse | CLT floor and wall panels paired with glulam framing | simplified structure | timber lattice | modular structure | innovative timber engineering |

| 18. | Maggie’s Centre | Engineered timber shell structure using LVL | simplified structure | standard timber | modular structure | sustainable and cost-effective materials |

| 19. | Cambridge Mosque | CNC-routed LVL with parametric design | simplified structure | timber lattice | modular structure | innovative timber engineering |

| 20. | Maggie’s Centre | Advanced prefabrication using CLT and glulam | simplified structure | standard prefab elements | modular structure | innovative timber engineering |

| 21. | Wisdome | Cross laminated timber with sustainable insulation materials | simplified free-form | standard LVL and CLT | modular dome elements | innovative timber engineering |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

| DfMA Sub-Processes | Application in Prefabricated Wooden Construction | Application of Parametric Design and CNC Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Design Simplification | Reduces complexity by minimizing the number of parts, simplifying geometries, and eliminating unnecessary features to streamline manufacturing and assembly | Parametric design tools generate optimized wooden components with simple, uniform geometries (e.g., standardized beams or panels). CNC technology ensures precise cutting, reducing errors and material overuse. |

| Standardization | Uses common components, materials, and processes to achieve economies of scale and reduce variability | Parametric tools design standardized wooden elements (e.g., cross-laminated timber panels) with consistent dimensions, fabricated by CNC for high precision and compatibility across projects. |

| Modularization | Designs products as independent, interchangeable modules for easy assembly and reconfiguration | Parametric design enables efficient prefabrication of modular wooden units (e.g., pre-assembled wall or floor modules) tailored for specific projects, CNC ensuring precise joints for rapid on-site assembly. |

| Production and Process Optimization | Streamlines manufacturing and assembly processes by aligning designs with advanced production technologies | Optimization of CNC cutting paths and assembly sequences for wooden components, CNC technology guided by parametric design, leveraging automation for precision and efficiency. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golański, M.; Juchimiuk, J.; Podlasek, A.; Starzyk, A. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment. Energies 2025, 18, 6332. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236332

Golański M, Juchimiuk J, Podlasek A, Starzyk A. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6332. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236332

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolański, Michał, Justyna Juchimiuk, Anna Podlasek, and Agnieszka Starzyk. 2025. "Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment" Energies 18, no. 23: 6332. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236332

APA StyleGolański, M., Juchimiuk, J., Podlasek, A., & Starzyk, A. (2025). Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) in Timber Construction: Advancing Energy Efficiency and Climate Neutrality in the Built Environment. Energies, 18(23), 6332. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236332