Thermal Characterization of Paraffin-Based Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage and Improved Thermal Comfort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.3. Thermal Conductivity Measurements

2.4. Density Measurements

3. Results

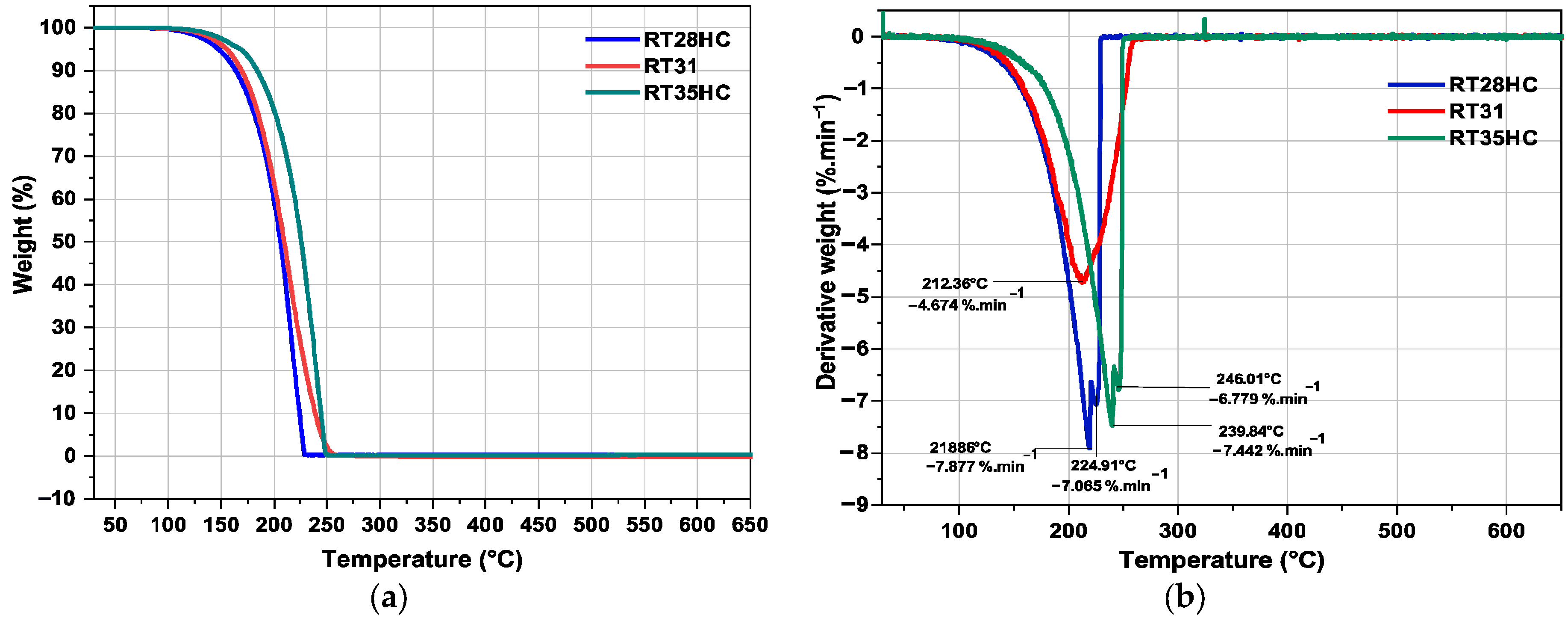

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis

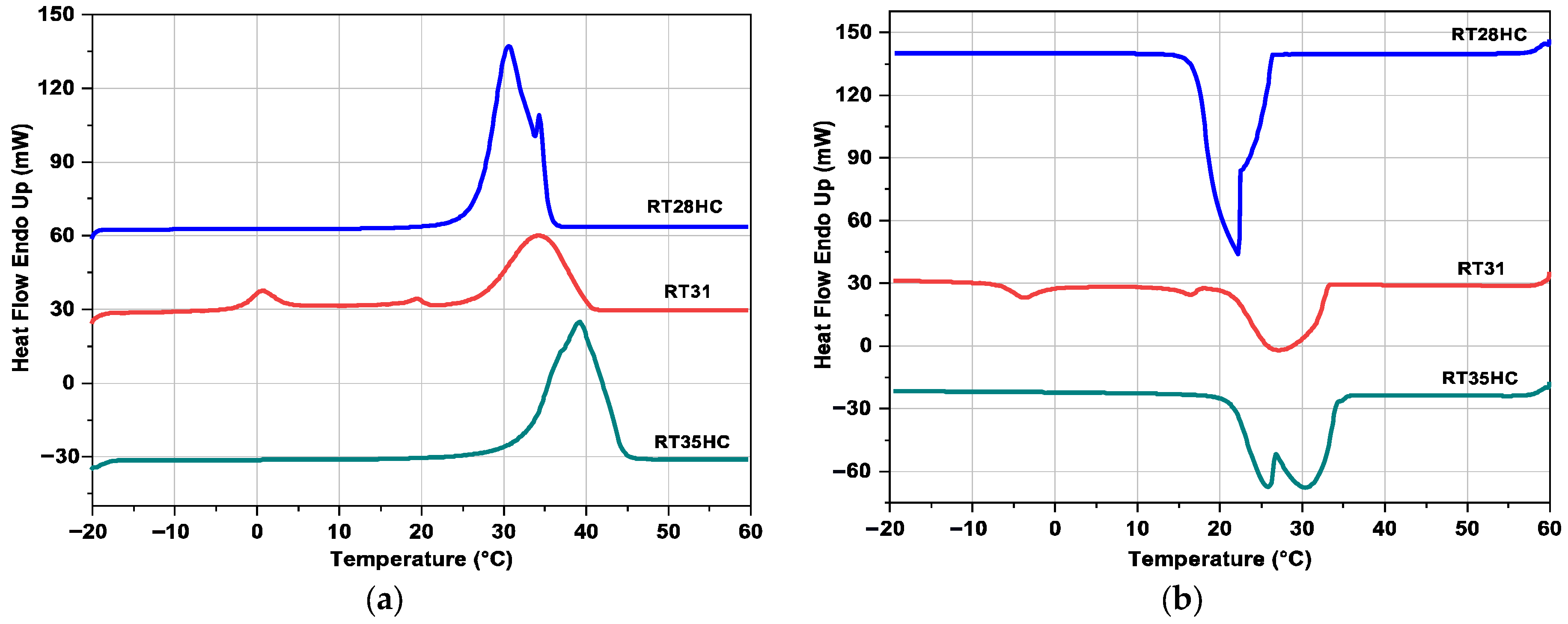

3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

3.2.1. Error Analysis

- Impact of thermal history: The enthalpy of fusion depends on the thermal history of the sample. A difference of up to 5 J·g−1 is frequently observed between the first and second heating.

- Influence of integration limits: The choice of integration limits can also lead to variations in the enthalpy of phase change. For paraffin, these variations can reach 1 to 4 J·g−1.

- Cup leakage: In order to avoid errors due to possible leakage from the cups, it is recommended that the samples be weighed before and after analysis. Loss of mass during heating can affect measurements and explain the scattered values reported in the literature.

- Repeatability and reproducibility: Short-term repeatability: when several successive analyses are carried out on the same sample, the values obtained remain coherent.Long-term reproducibility: On the other hand, if the sample is changed or the measurements are repeated after a long period, deviations may occur.Taking these precautions into account, it is then possible to compare the values obtained by varying the heating speed.

3.2.2. DSC Results at 10 °C·min−1

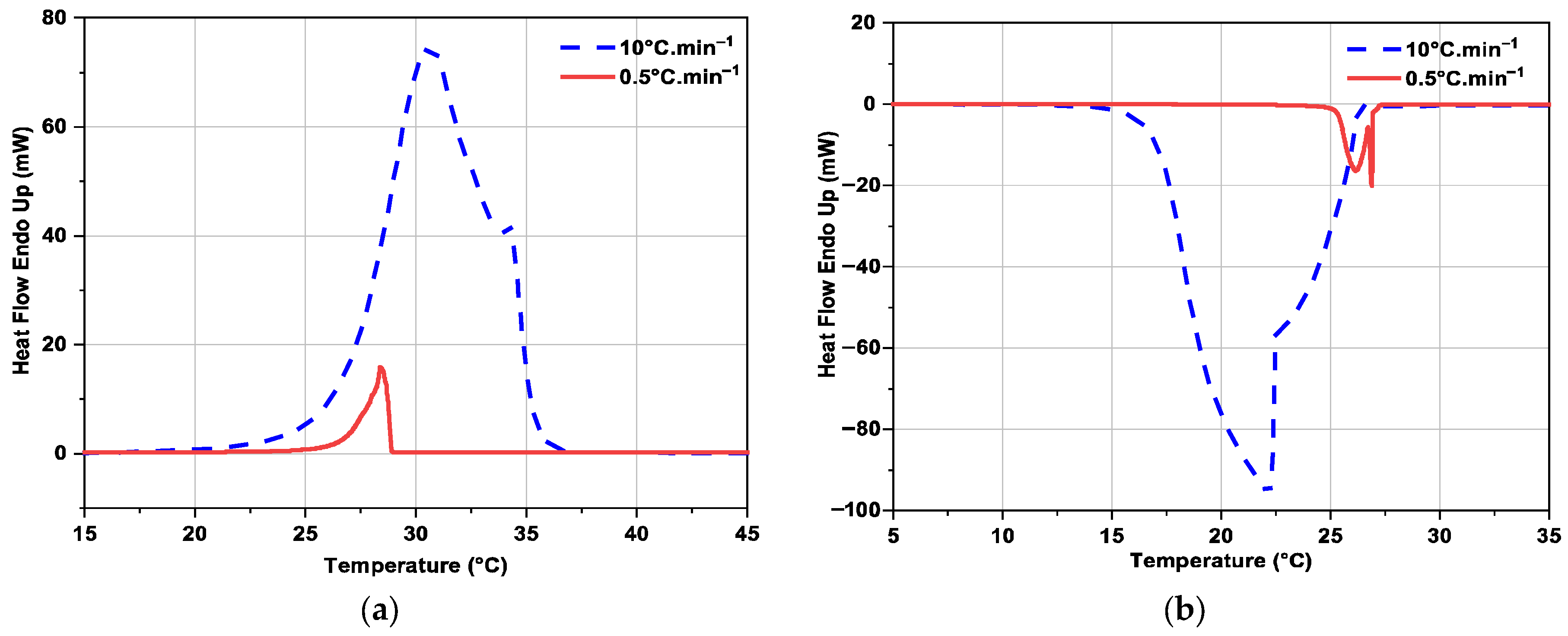

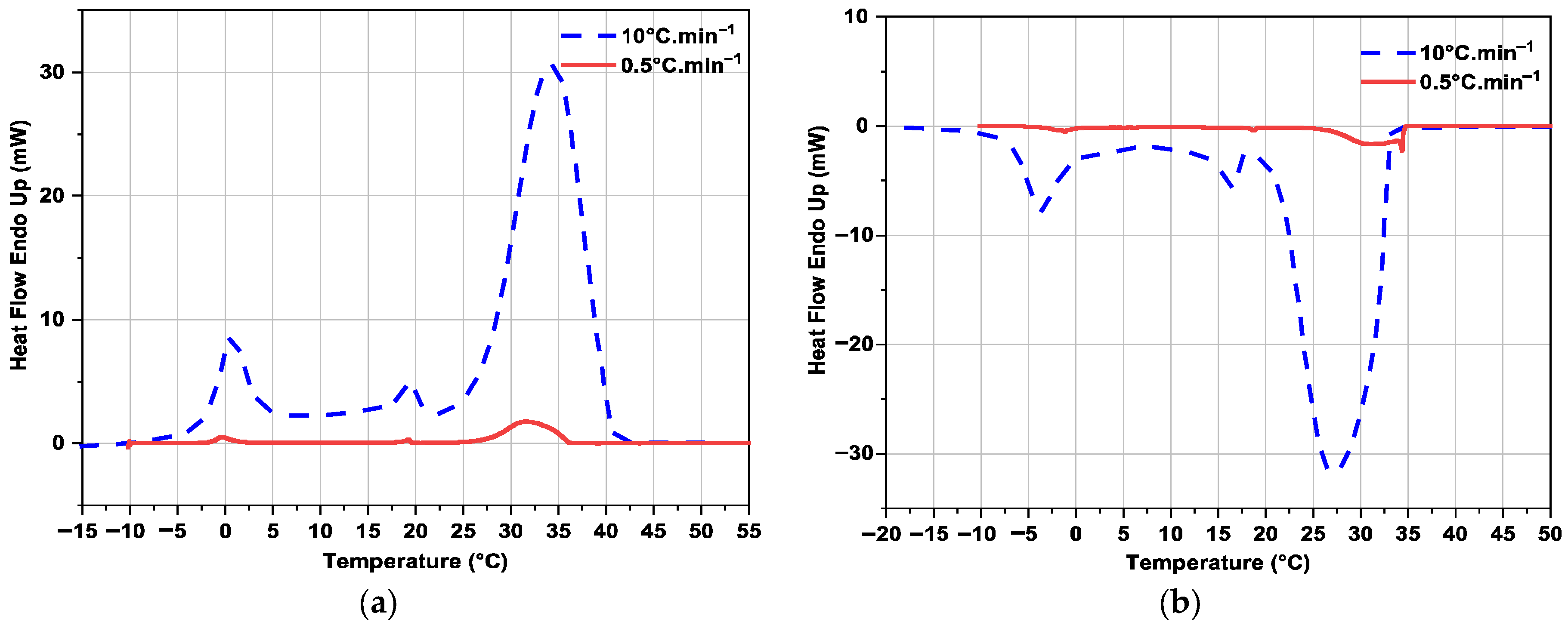

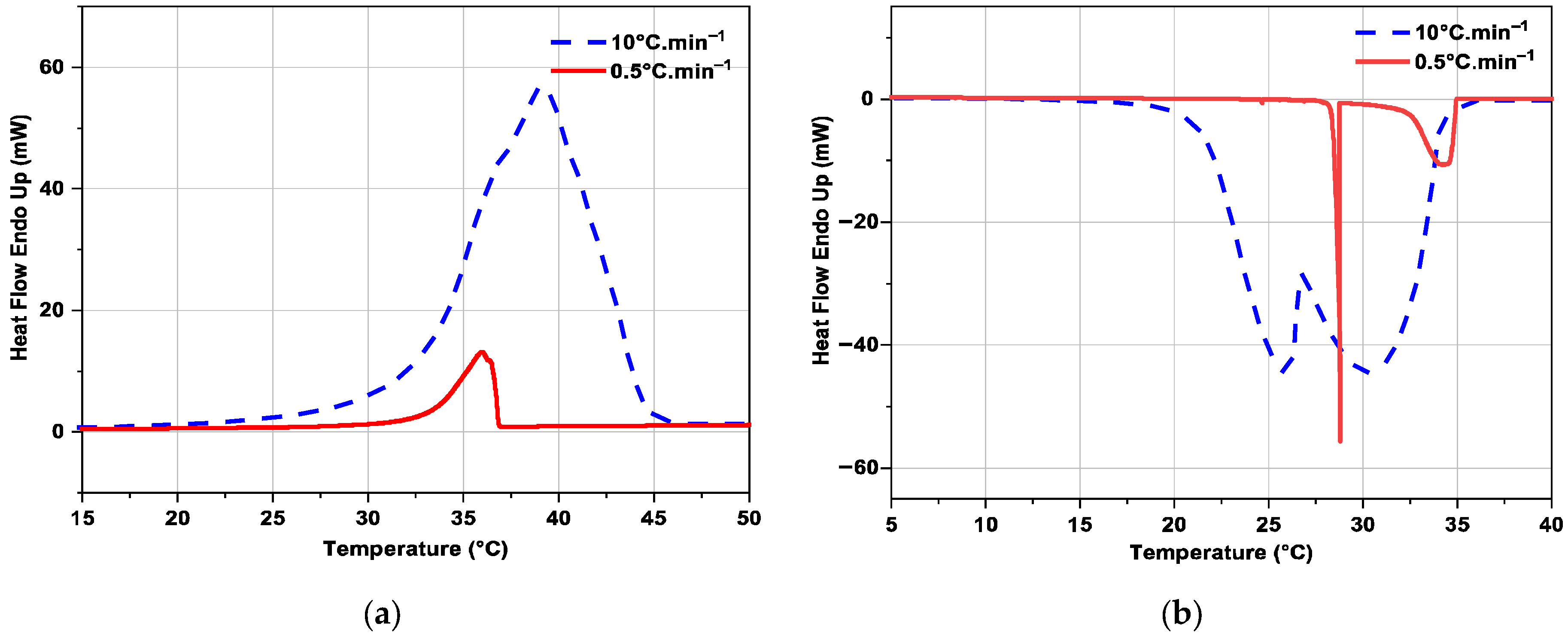

3.2.3. Influence of Heating or Cooling Rate on DSC Curves

| PCM | Reference | Rate | Tm (°C) | ΔHf (J·g−1) | Tc (°C) | ΔHc (J·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | Current work | 10 °C·min−1 | 26.5 | 225.1 ± 3.8 | 25.1 | 220.7 ± 3.7 |

| Current work | 0.5 °C·min−1 | 26.7 | 225.3 ± 3.8 | 26.4 | 224.3 ± 3.8 | |

| [47] | 0.5 °C·min−1 | 24.74 | 189.1 | 24.27 | 183.2 | |

| [47] | 2 °C·min−1 | 24.60 | 191.2 | 24.42 | 188.6 | |

| [47] | 5 °C·min−1 | 23.57 | 201.8 | 24.77 | 190.0 | |

| [48] | 0.5 °C·min−1 | 27.4 | 242.9 | 27.6 | 246.4 | |

| RT31 | Current work | 10 °C·min−1 | 27.0 | 111.9 ± 1.9 | 33.1 | 114.6 ± 2.0 |

| Current work | 0.5 °C·min−1 | 27.5 | 115.7 ± 2.0 | 34.5 | 115.4 ± 2.0 | |

| [42] | 5 °C·min−1 | 23.4 | 130.92 | 26.30 (peak) | 73.44 | |

| [43] | 10 °C·min−1 | 25.34 | 154.3 | - | - | |

| RT35HC | Current work | 10 °C·min−1 | 33.8 | 197.9 ± 3.4 | 34.1 | 196.2 ± 3.3 |

| Current work | 0.5 °C·min−1 | 33.5 | 199.2 ± 3.4 | 35.6 | 188.3 ± 3.2 | |

| [49] | 5 °C·min−1 | 33.94 | 242 | 33.92 | 244 | |

| [50] | 1 °C·min−1 | 34.06 | 255.88 | 31.71 | 260.79 |

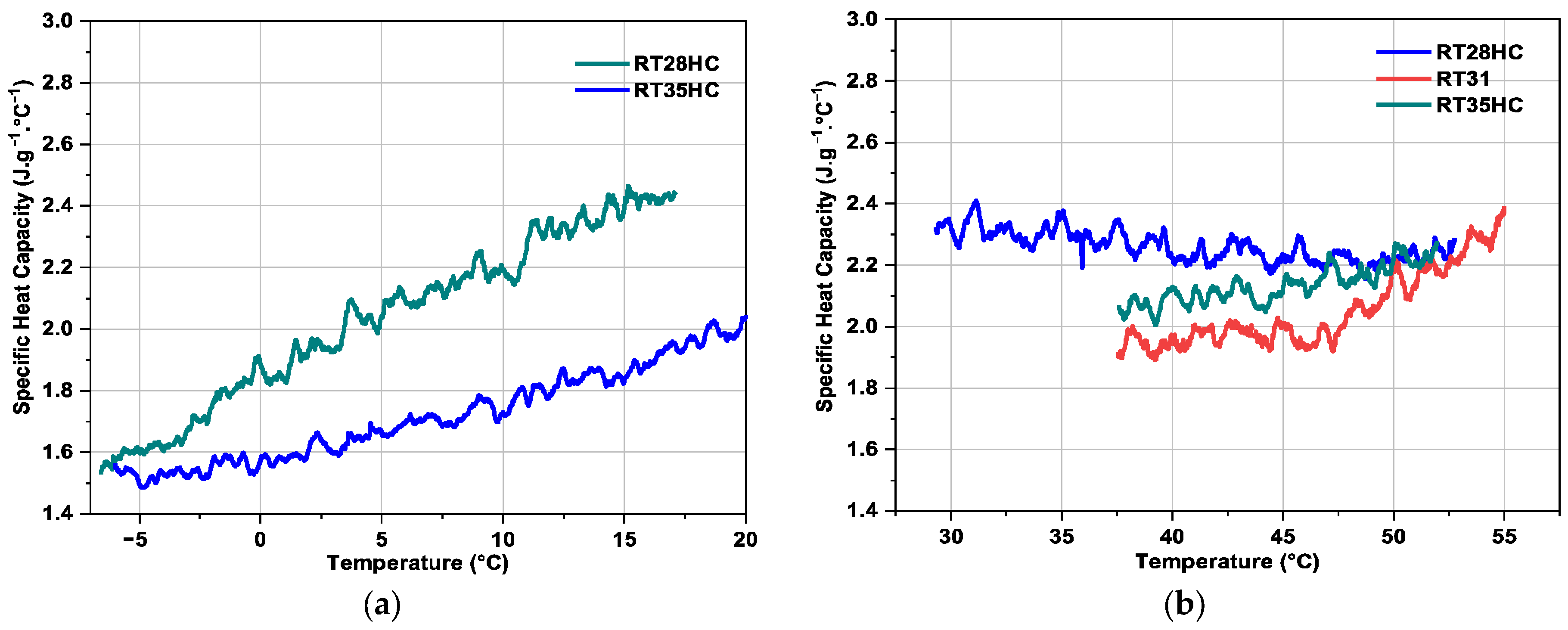

3.2.4. Specific Heat Capacity

3.3. Thermal Conductivity

3.4. Density Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UHI | Urban Heat Islands |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| PCM | Phase Change Materials |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| DTG | Thermogravimetric Analysis Derivative |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| Cp | Specific Heat Capacity (J·g−1·°C−1) |

| T | Temperature (°C) |

| ρ | Density (kg·m−3) |

| Tm | Melting Temperature (°C) |

| ΔHm | Melting Enthalpy (J·g−1) |

| TC | Crystallization Temperature (°C) |

| ΔHC | Crystallization Enthalpy (J·g−1) |

| λ | Thermal Conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) |

| α | Thermal Diffusivity (m2·s−1) |

References

- Montavez, J.P.; Rodriguez, A.; Jimenez, J.I. A study of the Urban Heat Island of Granada. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaviside, C.; Macintyre, H.; Vardoulakis, S. The Urban Heat Island: Implications for Health in a Changing Environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohamadi, P.; Che-Ani, A.I.; Maulud, K.N.A.; Tawil, N.M.; Abdullah, N.A.G. The Impact of Anthropogenic Heat on Formation of Urban Heat Island and Energy Consumption Balance. Urban Stud. Res. 2011, 2011, 497524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salami, H.A.; Dhaidan, N.S.; Abbas, H.H.; Al-Mousawi, F.N.; Homod, R.Z. Review of PCM charging in latent heat thermal energy storage systems with fins. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 51, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, H.; Cabeza, L.F. Heat and Cold Storage with PCM: An up to Date Introduction into Basics and Applications; Heat and Mass Transfer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiem, M. Contribution à la Caractérisation Thermophysique des Composites Mousses Métalliques/Matériaux à Changement de Phase Solide-Liquide. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paris Est Créteil, Créteil, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, R.; Islam, A.; Sharma, K. A review on the applications of PCM in thermal storage of solar energy. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regin, A.F.; Solanki, S.C.; Saini, J.S. Heat transfer characteristics of thermal energy storage system using PCM capsules: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2438–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tyagi, V.V.; Chen, C.R.; Buddhi, D. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change materials and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, C.; Khayet, M.; Ortiz De Zárate, J.M. Temperature-dependent thermal properties of solid/liquid phase change even-numbered n-alkanes: N-Hexadecane, n-octadecane and n-eicosane. Appl. Energy 2015, 143, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalba, B.; Marín, J.M.; Cabeza, L.F.; Mehling, H. Free-cooling of buildings with phase change materials. Int. J. Refrig. 2004, 27, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, N.; Sun, C.; Ma, Z.J.; Guo, S.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Wang, C. A review of incorporating PCMs in various types of concrete: Thermal and mechanical properties, crack control, frost-resistance, and workability. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.W.; Huang, M.J.; Smyth, M. Improving the heat retention of integrated collector/storage solar water heaters using Phase Change Materials Slurries. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2007, 28, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, G.; Ding, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, M. Experimental study on the thermal management performance of lithium-ion battery with PCM combined with 3-D finned tube. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 245, 122794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Chang, C.; Ju, H. Multi-objective passive design and climate effects for office buildings integrating phase change material (PCM) in a cold region of China. J. Energy Storage 2024, 82, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, R.; Jelle, B.P.; Gustavsen, A. Phase change materials for building applications: A state-of-the-art review. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikutegbe, C.A.; Farid, M.M. Application of phase change material foam composites in the built environment: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamrani, B.; Johannes, K.; Kuznik, F. Phase change materials integrated into building walls: An updated review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkizia, E.; Strunz, C.; Dauvergne, J.-L.; Goracci, G.; Peralta, I.; Serrano, A.; Ortega, A.; Alonso, B.; Zanoni, F.; Düngfelder, M.; et al. Study of paraffinic and biobased microencapsulated PCMs with reduced graphene oxide as thermal energy storage elements in cement-based materials for building applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A. An X-ray investigation of normal paraffins near their melting points. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Contain. Pap. Math. Phys. Character 1932, 138, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, J.; Denicolo, I.; Craievich, A. X-ray study of the “rotator” phase of the odd-numbered paraffins C17H36, C19H40, and C21H44. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 75, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, G.; Masic, N. Order in the rotator phase of n-alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirota, E.B.; King, H.E.; Singer, D.M.; Shao, H.H. Rotator phases of the normal alkanes: An x-ray scattering study. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5809–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholakova, D.; Denkov, N. Rotator phases in alkane systems: In bulk, surface layers and micro/nano-confinements. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 269, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Z.; Ocko, B.M.; Sirota, E.B.; Sinha, S.K.; Deutsch, M.; Cao, B.H.; Kim, M.W. Surface Tension Measurements of Surface Freezing in Liquid Normal Alkanes. Science 1993, 261, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Su, Y.; Wang, D. Confined crystallization of binary n-alkane mixtures: Stabilization of a new rotator phase by enhanced surface freezing and weakened intermolecular interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 15031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagazi, M.S.; Melaibari, A.A.; Khoshaim, A.B.; Abu-Hamdeh, N.H.; Alsaiari, A.O.; Abulkhair, H. Using Phase Change Materials (PCMs) in a Hot and Humid Climate to Reduce Heat Gain and Energy Consumption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinelabdein, R.; Omer, S.; Mohamed, E.; Gan, G. Free cooling using phase change material for buildings in hot-arid climate. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2018, 13, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, N. Évaluation de L’impact du Changement Climatique sur le CONFORT d’été des bâtiments à Basse Consummation; Centre d’études et d’expertise sur les risques, l’environnement; Cerema: Lyon, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Octobre 2022, le Mois le Plus Chaud à Paris… Depuis 1873! Available online: https://www.paris.fr/pages/temperatures-extremes-tempetes-tous-les-records-meteo-a-paris-20612 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Le Climat Futur en France, à quoi D’adapter? Available online: https://meteofrance.com/changement-climatique/quel-climat-futur/le-climat-futur-en-france (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ditmars, D.A.; Ishihara, S.; Chang, S.S.; Bernstein, G.; West, E.D. Enthalpy and Heat-Capacity Standard Reference Material: Synthetic Sapphire (Alpha-Al2O3) from 10 to 2250 K. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1982, 87, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, E.; Hiebler, S.; Mehling, H.; Redlich, R. Enthalpy of Phase Change Materials as a Function of Temperature: Required Accuracy and Suitable Measurement Methods. Int. J. Thermophys. 2009, 30, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesure de L’effusivité Thermique. Available online: https://www-techniques-ingenieur-fr.ezproxy.u-pec.fr/base-documentaire/mesures-analyses-th1/methodes-thermiques-d-analyse-42384210/mesure-de-l-effusivite-thermique-r2958/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Li, S.; He, L.; Lu, H.; Hao, J.; Wang, D.; Shen, F.; Song, C.; Liu, G.; Du, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Ultrahigh-performance solid-solid phase change material for efficient, high-temperature thermal energy storage. Acta Mater. 2023, 249, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techdata_-RT28HC. Available online: https://www.rubitherm.eu/media/products/datasheets/Techdata_-RT28HC_EN_09102020.PDF (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Techdata_-RT31. Available online: https://www.rubitherm.eu/media/products/datasheets/Techdata_-RT31_EN_18042024.PDF (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Techdata_-RT35HC. Available online: https://www.rubitherm.eu/media/products/datasheets/Techdata_-RT35HC_EN_09102020.PDF (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Lazaro, A.; Peñalosa, C.; Solé, A.; Diarce, G.; Haussmann, T.; Fois, M.; Zalba, B.; Gshwander, S.; Cabeza, L.F. Intercomparative tests on phase change materials characterisation with differential scanning calorimeter. Appl. Energy 2013, 109, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plaats, G. The Practice of Thermal Analysis; Mettler: Columbus, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, B. Thermal Analysis of Polymeric Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, C.; Santini, C.; Barbanera, M.; Giannoni, T.; Rubino, G.; Cotana, F.; Pisello, A.L. Phase change materials-impregnated biomass for energy efficiency in buildings: Innovative material production and multiscale thermophysical characterization. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Silva, L.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Sánchez, P. Influence of different suspension stabilizers on the preparation of Rubitherm RT31 microcapsules. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 390, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserved M-TII. All Rights Evaluation and Interpretation of Peak Temperatures of DSC Curves. Part 1: Basic Principles. Available online: https://www.mt.com/in/en/home/supportive_content/matchar_apps/MatChar_UC232.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Klimeš, L.; Charvát, P.; Mastani Joybari, M.; Zálešák, M.; Haghighat, F.; Panchabikesan, K.; El Mankibi, M.; Yuan, Y. Computer modelling and experimental investigation of phase change hysteresis of PCMs: The state-of-the-art review. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Huang, K.; Xie, H.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Cao, C. DSC test error of phase change material (PCM) and its influence on the simulation of the PCM floor. Renew. Energy 2016, 87, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laasri, I.A.; Charai, M.; Es-sakali, N.; Mghazli, M.O.; Outzourhit, A. Evaluating passive PCM performance in building envelopes for semi-arid climate: Experimental and numerical insights on hysteresis, sub-cooling, and energy savings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Kua, H.W.; Shah, K.W.; Hussein, G.F.; Zhang, B. Graphene nanoplatelets and copper foams for improving passive cooling performance of PCMs in Singapore’s tropical climate. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztop, H.F.; Gürgenç, E.; Gür, M. Thermophysical properties and enhancement behavior of novel B4C-nanoadditive RT35HC nanocomposite phase change materials: Structural, morphological, thermal energy storage and thermal stability. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 272, 112909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Jabbal, M.; Yan, Y. Thermophysical characteristics and application of metallic-oxide based mono and hybrid nanocomposite phase change materials for thermal management systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 181, 115999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wunderlich, B. Heat capacities of paraffins and polyethylene. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 9000–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahwaji, S.; Johnson, M.B.; Kheirabadi, A.C.; Groulx, D.; White, M.A. A comprehensive study of properties of paraffin phase change materials for solar thermal energy storage and thermal management applications. Energy 2018, 162, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faden, M.; Höhlein, S.; Wanner, J.; König-Haagen, A.; Brüggemann, D. Review of Thermophysical Property Data of Octadecane for Phase-Change Studies. Materials 2019, 12, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.D.; Sagara, K. Latent Heat Storage Materials and Systems: A Review. Int. J. Green Energy 2005, 2, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-E.; Jang, J.-W.; Kim, J.-K.; Wern, C.; Yi, S. Thermophysical Properties of Inorganic Phase-Change Materials Based on MnCl2·4H2O. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Zhang, T.Y.; Li, B.B.; Xue, Z.R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, D. Enhanced energy management performances of passive cooling, heat storage and thermoelectric generator by using phase change material saturated in metal foam. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 184, 107869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahan, N.; Fois, M.; Paksoy, H. Improving thermal conductivity phase change materials—A study of paraffin nanomagnetite composites. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 137, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Z.; Huang, S.; Huang, X.; Liang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, M.; Akrami, M.; Wen, C. Improving the melting performance of phase change materials using novel fins and nanoparticles in tubular energy storage systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mao, Z.; Song, B.; Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Sundén, B.; Wang, Y.-F. Enhancement of phase change materials by nanoparticles to improve battery thermal management for autonomous underwater vehicles. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 137, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Shu, L.; Yu, L.-P.; Zhu, L.; Song, L.-B.; Cao, Z.; Sun, L.-X. Preparation and thermal properties of exfoliated graphite/erythritol/mannitol eutectic composite as form-stable phase change material for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 178, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCM | Tm (°C) | Temperature Range (°C) | Latent Heat + Sensible Heat in the Temperature Range (J·g−1) | Density (kg·m−3) | Heat Conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | 27–29 | 21 to 36 | 250.0 ± 18.7 | 880 at 15 °C 770 at 40 °C | 0.2 |

| RT31 | 29–34 | 23 to 28 | 165.0 ± 12.4 | 830 at 15 °C 760 at 45 °C | 0.2 |

| RT35HC | 34–36 | 27 to 42 | 240.0 ± 18.0 | 880 at 25 °C 770 at 40 °C | 0.2 |

| PCM | Degradation Temperature (°C) | T5% (°C) | T25% (°C) | T50% (°C) | T100% (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | 81.3 | 147.4 | 187.2 | 205.9 | 229.2 |

| RT31 | 84.2 | 155.2 | 190.1 | 209.4 | 253.5 |

| RT35HC | 93.4 | 168.1 | 206.7 | 225.6 | 249.4 |

| PCM | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J·g−1) | Tc (°C) | ΔHc (J·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | 26.5 | 225.1 ± 3.8 | 25.1 | 220.7 ± 3.7 |

| RT31 | −2.0 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 33.1 | 114.6 ± 2.0 |

| 17.4 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 17.6 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | |

| 27.0 | 111.9 ± 1.9 | −0.2 | 15.2 ± 2.0 | |

| RT35HC | 33.8 | 197.9 ± 3.4 | 34.1 | 196.2 ± 3.3 |

| PCM | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J·g−1) | Tc (°C) | ΔHc (J·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | 26.7 | 225.3 ± 3.8 | 26.4 | 224.3 ± 3.8 |

| RT31 | −1.6 | 13.1 ± 0.3 | 34.5 | 115.4 ± 2.0 |

| 18.4 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 19.0 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | |

| 27.5 | 115.7 ± 2.0 | 1.4 | 16.2 ± 0.3 | |

| RT35HC | 33.5 | 199.2 ± 3.4 | 35.6 | 188.3 ± 3.2 |

| a | b | c | d | e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT28HC | |||||

| Solid | 1.6415 · 10−6 | −3.1957 · 10−5 | −4.4534 · 10−4 | 4.5437 · 10−2 | 1.8372 |

| Liquid | 8.9185 · 10−7 | −1.1392 · 10−4 | 5.1577 · 10−3 | −1.0234 · 10−1 | 3.1084 |

| RT31 | |||||

| Solid | - | - | - | - | - |

| Liquid | −2.6128 · 10−5 | 4.9156 · 10−3 | −3.4290 · 10−1 | 1.0531 · 101 | −1.1835 · 102 |

| RT35HC | |||||

| Solid | 2.0557 · 10−6 | −6.1754 · 10−5 | 7.8453 · 10−4 | 1.5286 · 10−2 | 1.5722 |

| Liquid | −1.7551 · 10−5 | 3.2106 · 10−3 | −2.1882 · 10−1 | 6.5977 | −7.2248 |

| PCM | RT28HC | RT31 | RT35HC |

|---|---|---|---|

| λ (W·m−1·K−1) | 0.344 ± 0.017 | 0.242 ± 0.012 | 0.422 ± 0.021 |

| α (mm2·s−1) | 0.074 ± 0.007 | 0.059 ± 0.005 | 0.114 ± 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferdjallah, L.; Fois, M.; Ibos, L. Thermal Characterization of Paraffin-Based Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage and Improved Thermal Comfort. Energies 2025, 18, 6331. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236331

Ferdjallah L, Fois M, Ibos L. Thermal Characterization of Paraffin-Based Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage and Improved Thermal Comfort. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6331. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236331

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerdjallah, Lydia, Magali Fois, and Laurent Ibos. 2025. "Thermal Characterization of Paraffin-Based Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage and Improved Thermal Comfort" Energies 18, no. 23: 6331. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236331

APA StyleFerdjallah, L., Fois, M., & Ibos, L. (2025). Thermal Characterization of Paraffin-Based Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage and Improved Thermal Comfort. Energies, 18(23), 6331. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236331