1. Introduction

Energy transition is a central theme in contemporary research, and in particular, energy vectors that can assist in energy transition have frequently been discussed in recent years. Polluting air emissions pose a crucial challenge to human and environmental health, and a large percentage of emissions comes from the automotive sector. New alternative fuels and vehicles are needed to reduce our dependence on petroleum products and to lower the carbon footprint of the transportation sector. Most alternative fuels on the market today represent a great potential; however, they are estimated to be just a temporary energy transition. Instead, hydrogen could become our primary zero-carbon transportation fuel in the near future [

1].

Hydrogen could be an important energy carrier playing a significant role in energy transition of the present and near future. It is, thus, important to point out the main properties of hydrogen. On the one hand, in fact, hydrogen is recognized as the most abundant element in the universe, but on the other, several issues regarding its storage and transport still need to be solved to fully employ it in automotive applications [

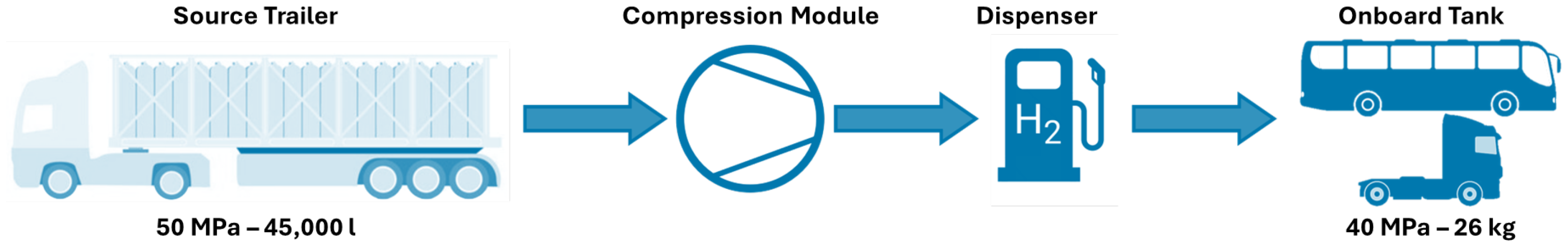

2]. One of the main challenges of working on auxiliary systems that support these alternative vehicles concerns the design of a compression system for refueling. As depicted in

Figure 1, the compression module is the key element in conveying hydrogen from a source to onboard tanks. Hydrogen is, in fact, the element with the lowest density (0.089 kg/m

3 at atmospheric pressure and 0 °C [

3]) and therefore requires either large storage volumes or high compression to be consistent with automotive applications (storage in liquid form would allow the use of smaller tanks, but it requires cooling to temperatures below −253 °C, making the process energy-wasting) [

4]. Depending on the type of application, hydrogen for refueling is usually stored in a pressure range between 35 and 70 MPa.

The main issue is that gas compression from hydrogen production to onboard tanks is generally costly and energy-intensive. Considering production at 2 MPa, the theoretical energy to compress hydrogen isothermally from 0.2 MPa to 35 MPa is approximately 1.05 kWh/kg and about 1.36 kWh/kg to reach 70 MPa [

5]. However, the calculation becomes more complex when considering factors such as a polytropic transformation, different stages of compression, and a correction factor for real gases, leading to a less favorable estimate. The energy consumption for hydrogen compression in practical scenarios can be greater than 5.6 kWh/kg if a pressure of 70 MPa is reached [

6]. Moreover, in real-world applications, there are numerous factors that increase these theoretical values, such as friction, temperature increase or pressure drops during transportation [

7]. The main challenge is therefore to develop systems with cost and energy efficiency, making fueling affordable.

Mechanical compressors are the predominant choice among the assortment of compressors employed for this task. These compressors act by reducing the volume of the chamber in which hydrogen gas is contained. The two most common types are reciprocating piston compressors and reciprocating diaphragm compressors [

8]. Reciprocating piston compressors (RPCs) are a consolidated technology where the reciprocating motion of a piston in a cylinder compresses the gas. RPC systems in a multi-stage configuration have the capability to compress hydrogen to elevated pressures. However, oil-free RPC systems have several limitations. First, the presence of moving components increases both production and maintenance costs and produces noise and vibration. In addition, these moving parts generate extra heat, which complicates the heat management processes. The main drawback of hydrogen reciprocating compressors, however, is embrittlement. RPCs are, in fact, susceptible to embrittlement, which often results in frequent seal ring failures due to non-uniform pressure distribution [

9].

Instead, reciprocating diaphragm compressors (RDCs) operate by deforming an elastic diaphragm to compress hydrogen. A conventional method for mechanical compressors involves consuming about 5 kWh/kg of energy during the compression process [

9]. Recent studies, however, have been developing control methods and models to improve the efficiency of these systems [

10,

11,

12].

It is important to note that mechanical compressors are not the only technology on the market or in development for hydrogen compression [

13]. As seen above, the low energy density of hydrogen results in energy-wasting transformations through mechanical compressors. Conversely, non-mechanical hydrogen compressors offer solutions with limited moving parts, compact designs, and safe operations. Although these solutions are still in the development stage, it is important to acknowledge their promising designs. One promising alternative involves ionic liquid compressors, which use ionic liquid instead of a conventional piston mechanism. Ionic liquid has two basic properties: virtually unmeasurable vapor pressure and a high temperature range for the liquid phase. The latter, together with the low solubility of some gases (such as hydrogen), makes ionic liquids suitable for use as compression barriers. An ionic liquid piston compressor can achieve a specific energy consumption of approximately 2.8 kWh/kg when compressing hydrogen from 0.5 MPa to 100 MPa in five steps [

14]. This level of efficiency is remarkable, as it represents only about 25% of the specific energy consumption required by a reciprocating compressor [

9]. However, this technology provides a mass flow rate that is nearly one-third of the target rate for a fast refueling process [

15]. Another drawback of this technology is its complex design, which is still under development [

16,

17].

Another alternative involves electrochemical hydrogen compressors, which operate based on the same basic principles as those of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). At elevated pressures, high-pressure electrochemical compression faces significant challenges due to hydrogen backscattering through the membrane, resulting in reduced system performance. Therefore, although several studies have shown that this system has the potential to reach pressures up to 100 MPa, it is not convenient from a practical and energetic point of view [

18]. Recent studies have shown that electrochemical compressors are better suited for low-pressure applications, with a maximum limit of 10–20 MPa in order to achieve the optimal energy consumption and avoid critical operating temperatures [

19,

20].

Metal hydride compressors efficiently compress hydrogen without moving parts, such as pistons or diaphragms. Metal hydrides are used to absorb and desorb hydrogen simply through heat and mass transfer in the reaction system. However, the system’s efficiency is relatively low (below 25%), as it is limited by the heat transfer between the heating/cooling fluid and the metal hydride alloy. A two-stage compressor generally requires about 10 kWh/kg of energy, including unavoidable thermal losses [

21,

22].

The development of new green solutions is possible precisely because of the presence of various hydrogen compression technologies, including hydraulic-based systems. The latter have been widely studied and optimized to provide an effective and robust alternative that overcomes the limitations of traditional methods. Recent research shows that employing hydraulic power in different application contexts can significantly improve the efficiency, reliability and scalability of compressors [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Thus, this article presents an overview of an innovative hydrogen compression technology using hydraulic power. The goal is to identify alternatives to conventional methods that can address the previously mentioned limitations. It is in this context that the H2REF-DEMO project started. H2REF-DEMO is a project co-funded by the European Union’s “Horizon. Europe” programme under the “Clean Hydrogen Partnership” (grant agreement no. 101101517) [

27], involving several companies and research centers. The project aims to further develop and scale up by a factor of five the innovative compression concept developed in the former H2REF project [

28]. The former project investigated the capability of hydrogen compression through hydraulic power, focusing on passenger vehicle refueling. Scaling up of the system is necessary to handle large-vehicle refueling applications that require hydrogen delivery rates of hundreds of kilograms per hour, such as refueling stations for bus fleet depot, trucks or trains. The basic principle is exploiting hydraulic power to compress hydrogen through hydro-pneumatic bladder accumulators. Pumping oil into the accumulator deforms the bladder containing H

2 causing a consequent gas compression and allowing it to be conveyed to the vehicle tank. The decision to use this technology also relied on its intrinsic characteristics, including the energy density, robustness, and proven reliability.

The following paragraphs present the basic functioning and subsequent development of this hydro-pneumatic compression system in detail. We exploited a lumped parameter numerical model to support the system design and decision-making process.

2. Hydrogen Compression Using Hydro-Pneumatic Accumulators and Hydraulic Power Units

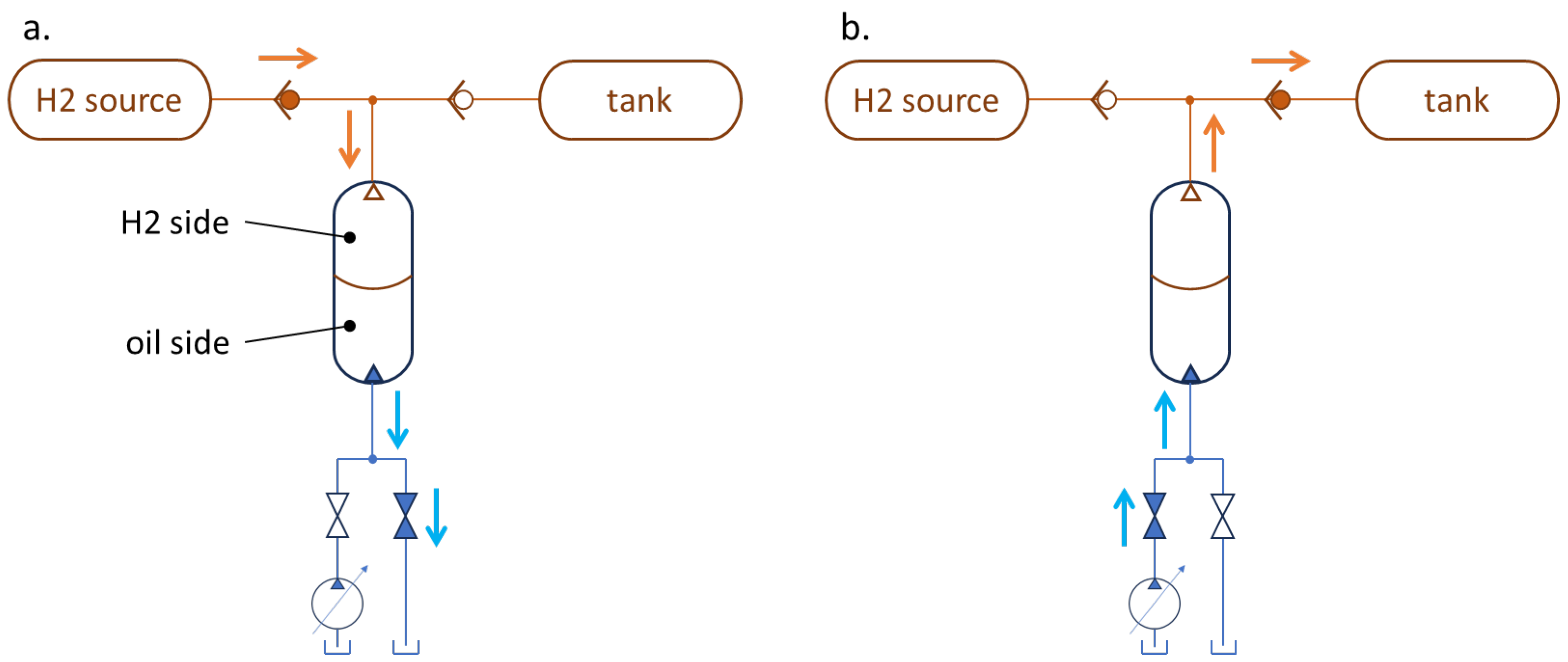

The starting point for the development of this new hydrogen compression system involves the use of bladder accumulators that can expand and contract with the help of hydraulic fluid entering and exiting the accumulator. These bladder accumulators must have two separate inputs, one for oil and one for gas.

Figure 2 illustrates the basic operation of the simplified system consisting of a hydrogen source, a hydraulic accumulator, and a pressurized tank. Assuming a very-high volume hydrogen source, we considered the source pressure

to be nearly constant during compression.

The oil side of the accumulator discharges to the hydraulic tank through an on/off valve, which allows natural flow of gas from the source to the bladder until it is completely filled at (a). The oil pumping phase inside the accumulator can start once the bladder is filled with gas. As the bladder volume decreases, the hydrogen pressure increases from to the tank pressure, . Once this threshold pressure is exceeded, the outlet check valve opens, allowing hydrogen to enter the onboard tank as the bladder compression continues (b). Of course, the tank pressure increases due to the introduction of hydrogen in each cycle. This pressure increase impedes the natural flow from the hydrogen source to the tank, making it necessary to use one or more compression modules.

Note that the preceding description is only a simplified and qualitative functioning of the underlying concept of the new hydrogen compression system for refueling. In fact, at this stage, we have neglected the thermal aspect of compression and the actual compression ratio. However, these aspects will be crucial for the correct functioning of the complete system.

The achievable compression ratio in a single compression stage (as the simplified system depicted in

Figure 2) has been limited to 3 due to technological issues. In fact, greater values resulted in critical temperatures for hydrogen due to the heat of compression during experimental tests. However, these temperatures are not critical for the gas itself [

15] but rather for the elastic bladder material, causing blistering and hydrogen permeation through porosity. Consequently, rapid gas decompression tests were conducted at CETIM, using different materials for the bladder. The material that was less sensitive to permeation and undamaged after the test was selected based on these results. Taking the case study of compression from a hydrogen source at 5 MPa to an onboard tank that needs to reach approximately 40 MPa for a complete refueling [

15] as reference, we must consider using at least two compression units through hydro-pneumatic accumulators. For simplicity, we will refer to these two compression units as Elementary Compression Units 1 and 2 (ECU1 and ECU2, respectively). It is important to note that we consider 5 MPa to be the worst-case scenario, representing the minimum pressure level in an empty H

2 source trailer. An additional pre-compression step must be implemented if the source pressure drops below this minimum value.

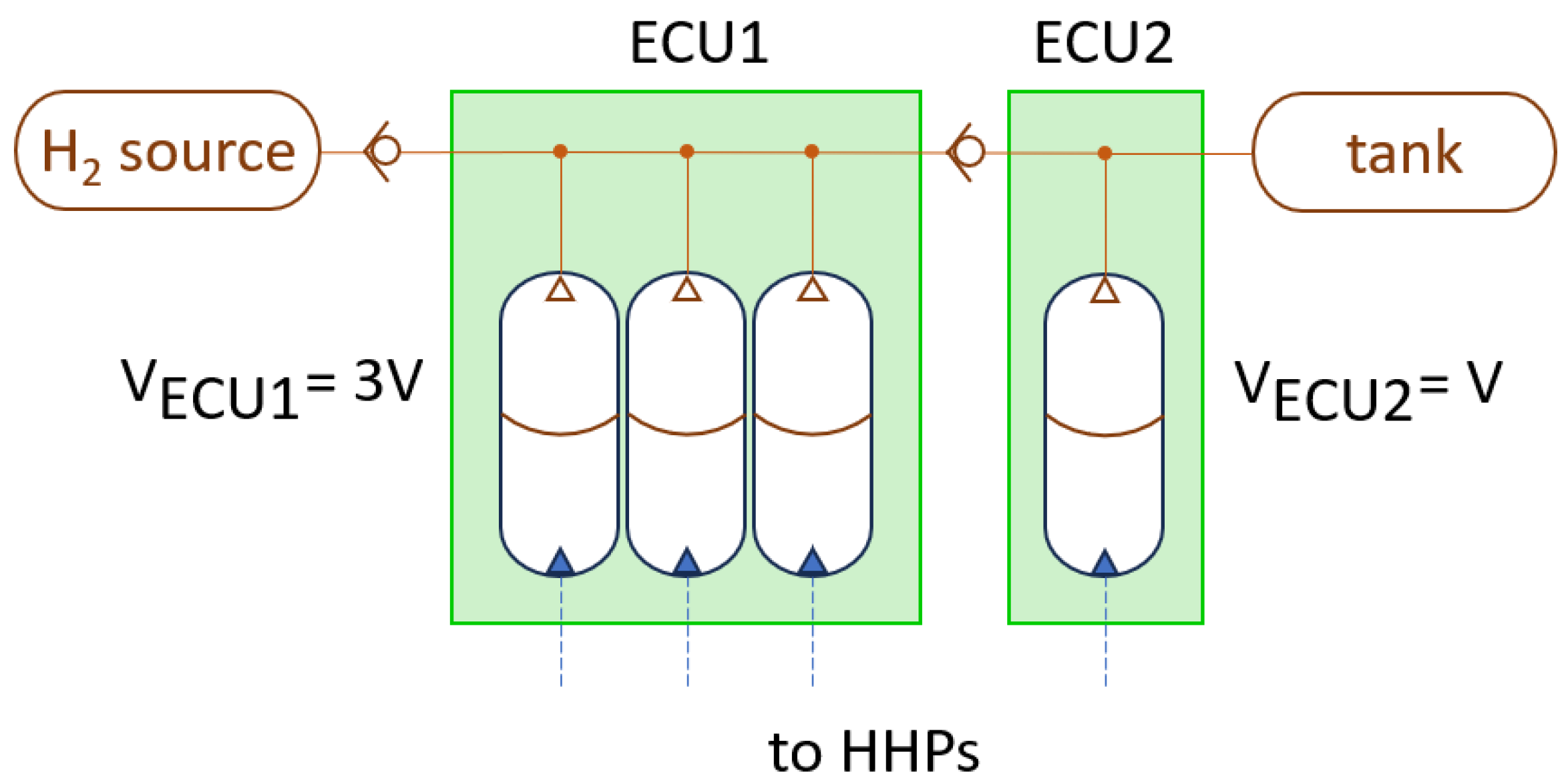

However, using the same number of accumulators in both compression units does not allow for synchronized movement. In fact, with equal volumes, ECU1 requires more cycles to fill the ECU2 accumulators at the intermediate pressure. This results in a highly discontinuous flow because it is necessary to wait for all of the ECU2 accumulators to fill before completing the compression and conveying H2 into the vehicle tank. Thus, we considered a layout where the number of accumulators in ECU1 and ECU2 allows synchronized movement of the units. It was necessary to evaluate how many accumulators are needed to compress H2 from ECU1 to ECU2 while maintaining a compression ratio limited to about 3.0.

The result depends on the compression capability of the accumulators. Of course, the bladder cannot be compressed to zero volume, so there will always be a dead volume. Using as reference a bladder accumulator catalog [

29], we considered a volumetric compression ratio

.

H

2 volumes before (state 1, Equation (

1)) and after (state 2, Equation (

2)) the first compression are as follows, where

N is the number of accumulators associated to each element of the second stage and

is the volumetric compression ratio.

Note that we considered that the quantity of H2 executed by stage 1 after the first compression to occupy the dead volume of ECU1 and the expanded unit of ECU2.

Considering the compression to be a polytropic process where

[

30], it is possible to evaluate the volumetric compression ratio

referred to the maximum compression ratio we want to achieve (i.e.,

) in Equations (

3)–(

6).

Then, it is possible to correlate the number of accumulators with the volumetric capability by replacing

and

with the values defined for the first compression.

Using

, as previously defined, ensure that three accumulators provide sufficient compression capability to slightly overcome the maximum compression ratio of 3.0.

Since the choice of three accumulators is only an approximation of the calculated value, it is necessary to sacrifice the actual volumetric capability of the units to never exceed the actual limit of a ratio of 3.0. It is also possible to calculate the actual

required with three accumulators in ECU1 for each ECU2 accumulator by rearranging Equation (

7).

Note that this calculated value is nearly the exact compression ratio limit that is considered to avoid critical temperatures. Partners in the project are conducting experimental tests to confirm that a 3:1 accumulator ratio allows for the synchronization of the stage and the desired compression ratio.

Figure 3 shows the resulting scheme for ECU1 and ECU2, with the hydraulic part omitted for clarity. Therefore, it is possible to synchronize the units and fully fill the second stage by compressing the first stage using three accumulators in ECU1 for each accumulator in ECU2.

3. H2REF-DEMO Layout for Hydrogen Compression

We could then design the refueling system layout starting from the theoretical study concerning the correct number of accumulators to obtain the desired compression ratio between the stages.

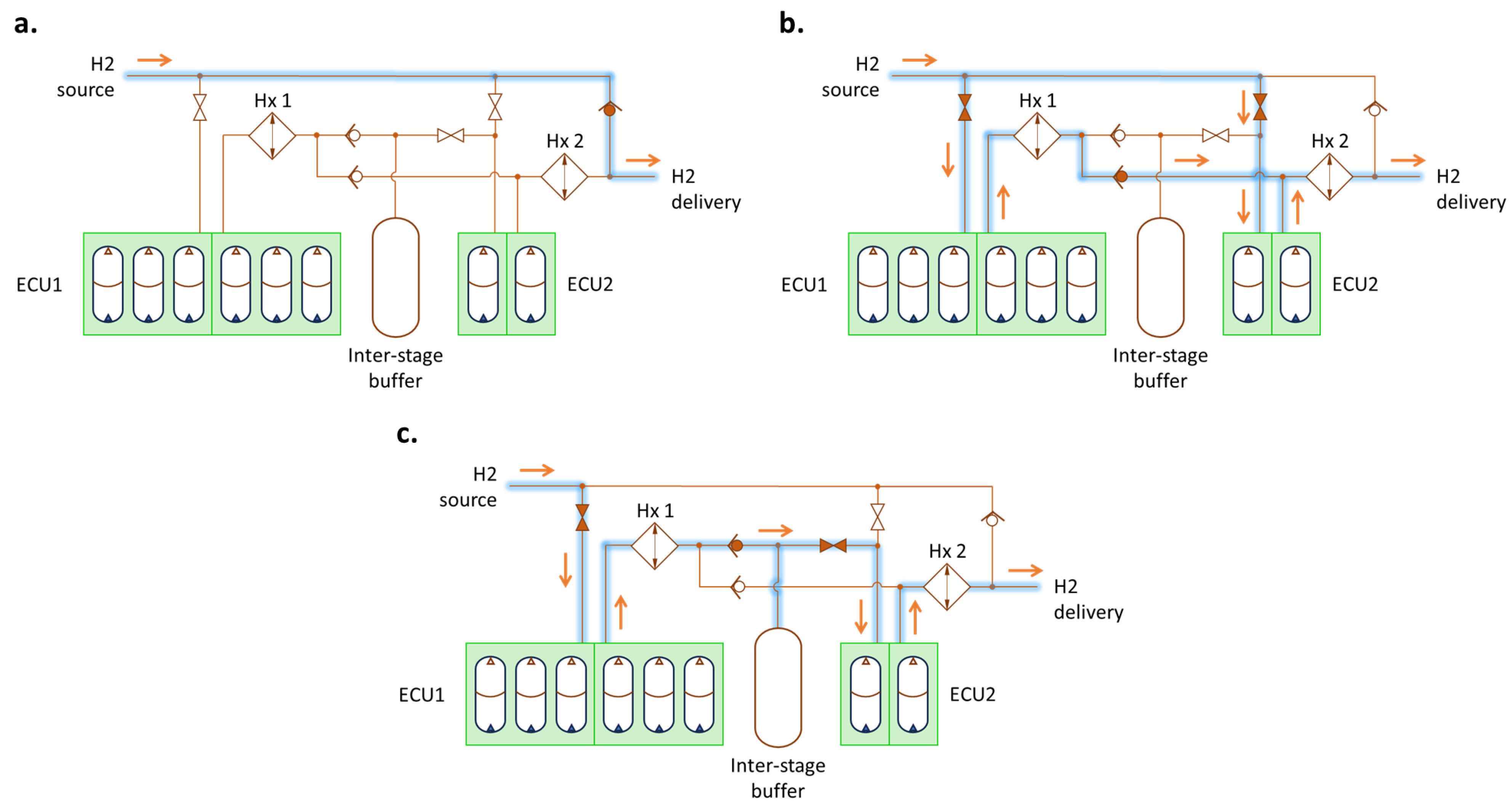

Figure 4a depicts the final version of the considered layout, which includes all the functional valves and features necessary for the correct functioning of the system. As mentioned, this is just the final version of the system layout, which was obtained through an iterative optimization process involving numerical simulations.

Referring to

Figure 4a, we can identify the main subgroups of the systems, namely:

H2 source, which is a high-volume reservoir tank of hydrogen pressurized at the desired initial pressure. The high volume allows the initial pressure to remain nearly constant throughout the refueling cycle.

ECU1, which consists of two sets of three accumulators each (Type I [

31], shell consisting entirely of metal) to achieve the desired compression as shown in the previous paragraph. Having two sets allows for alternating movement (one set compressing and one set expanding), resulting in a more constant outlet flow rate.

ECU2, which consists of two sets of one accumulator each (Type I [

31], shell consisting entirely of metal) to achieve the desired compression as shown in the previous paragraph. Thus, there is one ECU2 accumulator for every three ECU1 accumulators.

Inter-stage buffer, positioned between ECU1 and ECU2, which intervenes when two compression stages are needed, managing the excess or deficient flow rate from ECU1 to ECU2. We selected a Type II [

31] pressure vessel, which consists of a metallic inner liner and an outer wrapping of synthetic material.

Hydraulic power pack (HPP), which manages the oil entering and exiting the accumulators. We selected three pumps for ECU1 (one for each compressing accumulator) and two pumps for ECU2.

Heat exchanger (Hx) 1 and 2, and corresponding chillers. Hydrogen cooling is a fundamental aspect because the gas heats up when compressed and must be cooled down before another compression or before being conveyed to the onboard tank to satisfy safety regulations [

15].

Vehicle tank. We considered a 2 × 625-L tank, which is a standard heavy vehicle tank. This is a Type IV [

31] tank consisting of a non-metallic inner liner made of composite materials and an outer wrapping made up of carbon fiber.

Note that we used I and II in

Figure 4a to distinguish the two sets of accumulators in ECU1 and ECU2.

Concerning the accumulators in ECU1 and ECU2, we selected a 130-L accumulator from the Hydac catalog [

29] as reference. This accumulator seemed to satisfy all functional requirements in terms of operating conditions.

We selected the inter-stage buffer volume as a trade-off point between reducing pressure oscillations (larger volumes result in smaller oscillations) and avoiding significant increases in energy consumption (larger volumes result in greater energy consumption). We could make this choice thanks to a sensitivity analysis done through numerical simulations.

Table 1 shows the main parameters of the final H2REF-DEMO layout.

The main subgroups of the H2REF-DEMO layout listed above were then connected via hydraulic and pneumatic pipes to enable all working modes and ensure the complete functioning of the system.

The different working modes and an overview of the control logic that manages them are presented in the following paragraph.

Figure 4b depicts a simplified version of the layout of the H2REF-DEMO compression system, where the compression units ECU1 and ECU2 have been simplified, as well as the corresponding hydraulic power packs.

4. H2REF-DEMO Functioning

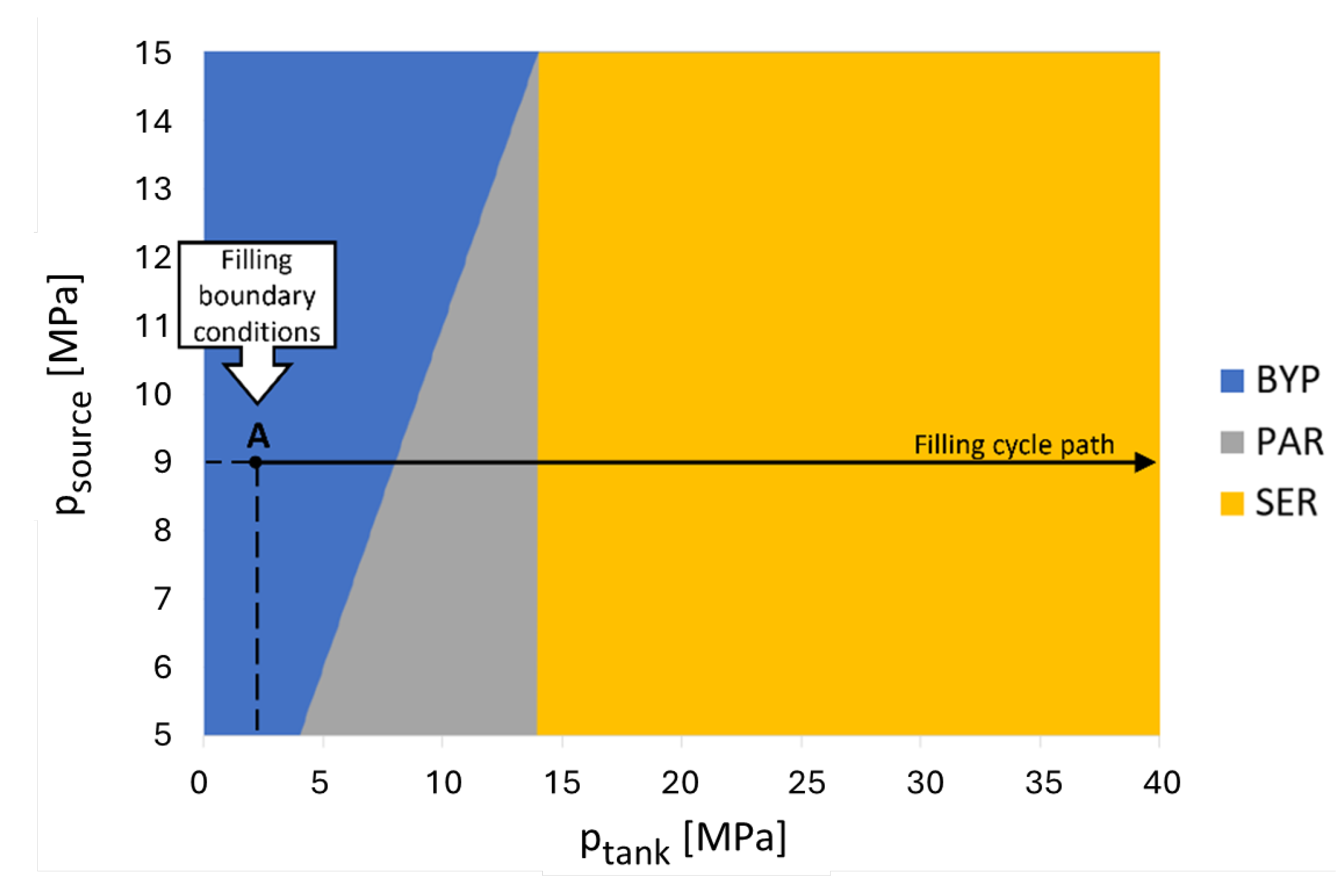

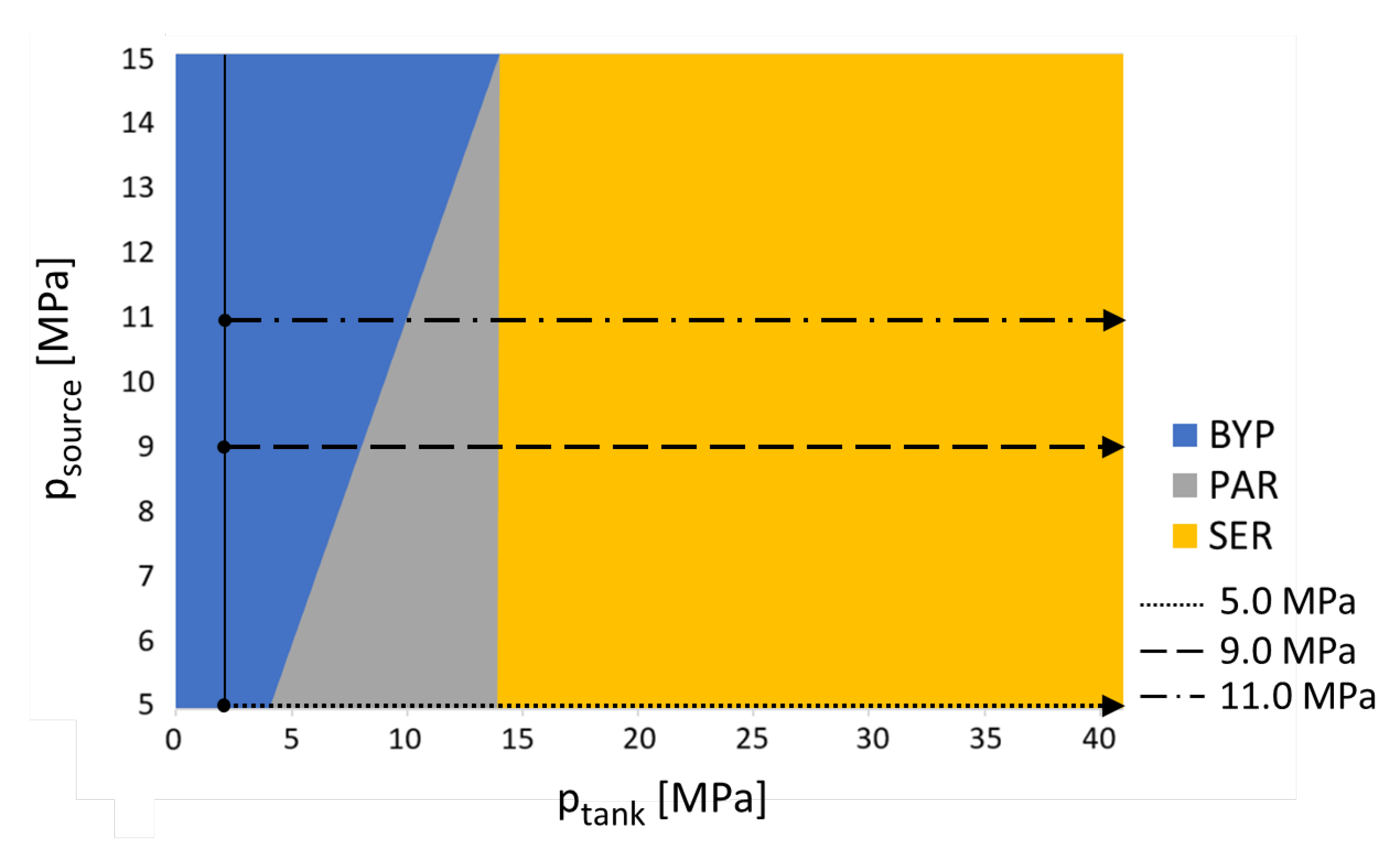

The three main working modes considered for the H2REF-DEMO can be identified as follows:

Bypass mode, which happens when the source pressure

is higher than the actual onboard tank pressure

allowing the natural flow from the former to the latter. Note that the flow rate must be controlled not to exceed the feasible values defined by the refueling protocols [

15].

Parallel mode, which happens when a single stage of compression is sufficient to convey H2 from the source to the vehicle tank. ECU1 and ECU2 work independently in parallel at their maximum volumetric efficiency in a non-synchronized way to grant the maximum outlet flow rate.

Serial mode, which happens when two stages are needed to complete the hydrogen compression from the source to the vehicle tank. In this mode, the two compression units work in series and the control logic must ensure the synchronization between the ECU2 expansion and the ECU1 compression, as the outlet flow rate of ECU1 is the inlet flow rate ECU2. The inter-stage buffer must manage the underflow or overflow from ECU1 to ECU2.

Parallel mode lasts until a threshold pressure

is reached in the vehicle tank. Beyond this threshold, Serial mode is engaged. The threshold pressure must be adjusted so that the compression ratio does not reach critical values in both ECU1 (Equation (

9)) and ECU2 (Equation (

10)).

In this way, it is possible to keep the gas temperatures in the accumulators controlled below the critical temperature, which should not be exceeded for the aforementioned reasons. Since we had to ensure a safe and robust threshold pressure throughout the possible pressure range, we considered the worst-case scenario, which occurs when greater compression ratios are needed (i.e., for low source pressure). However, we chose a compression ratio slightly lower than the maximum one (i.e., 3) to guarantee safe and reliable operation and to avoid exceeding that value during mode transitions.

Considering a source pressure of 5 MPa as the worst-case scenario and 2.8 as the compression ratio, Equation (

11) reports the calculated threshold pressure.

In this design phase, we thus selected a constant pressure of 14 MPa as threshold pressure, as also reported in

Table 1. As mentioned, this value ensures that the maximum compression ratio of both ECU1 and ECU2 is not exceeded with any possible pressure source. Naturally, the tank filling is faster during Parallel mode because all the accumulators in ECU1 and ECU2 convey H

2, while only the accumulators in ECU2 do so in Serial mode.

Figure 5 depicts the layout scheme highlighting the hydrogen path in the different working modes (i.e., Bypass, Parallel and Serial mode). Note that we have reported the compact version of the layout for the sake of simplicity.

5. System Model and Layout Performance for a Refueling Cycle

As anticipated, we developed and exploited a numerical model to make some choices regarding the layout design. In fact, we proceeded with the step-by-step creation and modification of a lumped parameter numerical model of the system concurrently with its design process. The software used for modeling the considered system is the commercial software Simcenter Amesim® (version 2304), specific for the lumped parameter simulation of multi-domain systems. This approach not only provided a design support tool capable of assessing the effect of various modifications, but also served as a virtual tool for evaluating the system performance with reasonable accuracy, since many details of the single components and a realistic control logic have been implemented in the model. After defining the final system layout, it was possible to assess its performances in terms of average hydrogen flow, energy consumption, and compliance with the several system constraints during a refueling cycle.

5.1. Accumulators

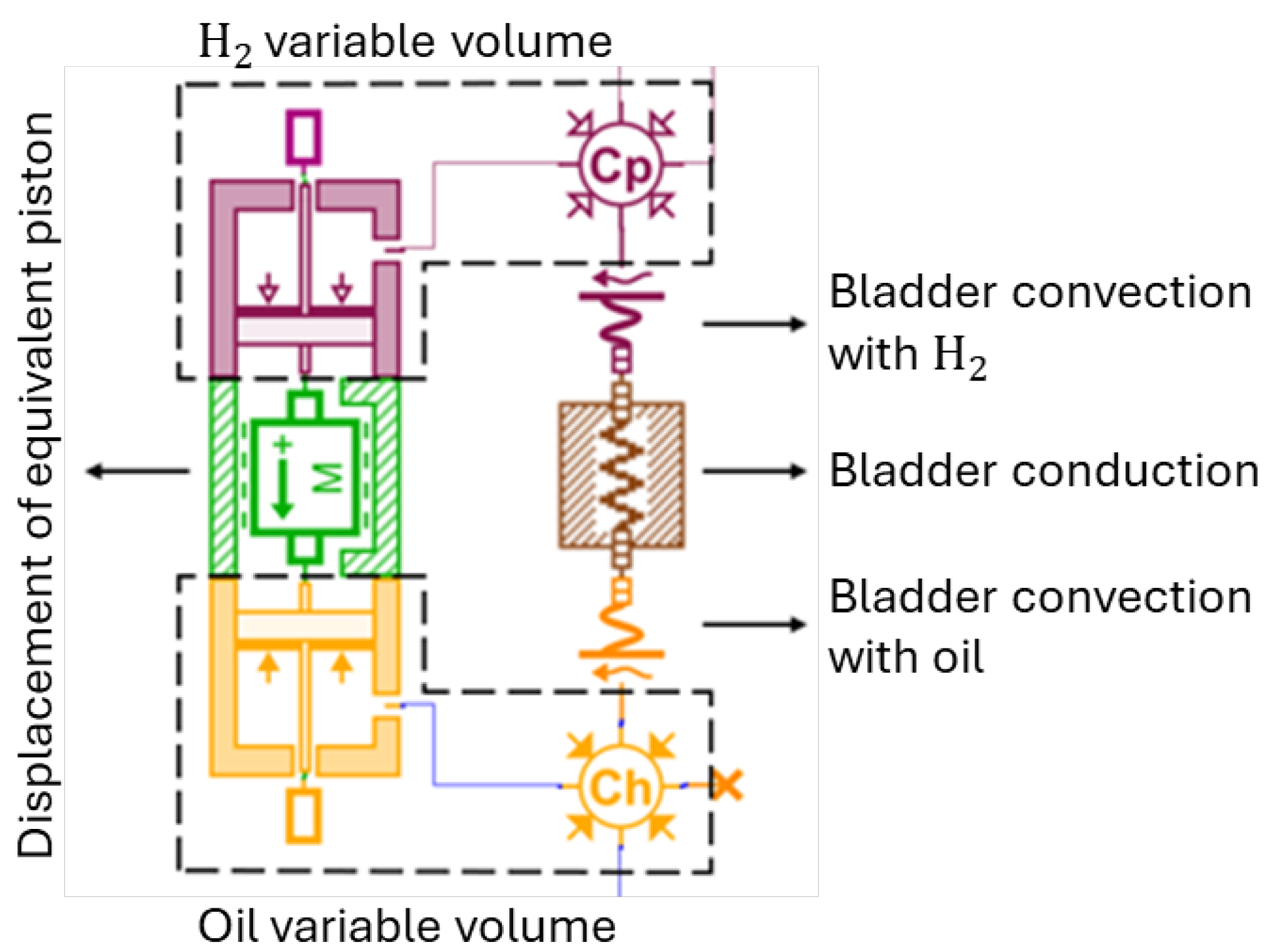

We modeled the accumulator with two variable volumes: one on the oil side and one on the H2 side, which expand and compress reciprocally. Since we opted for a lumped parameter approach, we had to simplify the complex movement and deformation of the bladder responsible for expansion and compression.

For this reason, we explored two approaches to model the accumulators: one using an equivalent linear actuator and the other using an actual elastic diaphragm that separates the chambers and is parametrized with the mass of the bladder. The displacement of the actuator or the deformation of the diaphragm is generated by the oil delivered by the pump. Testing these two different approaches revealed that the small inertia of the bladder influences the dynamic pressure by several orders of magnitude less than stationary forces. This led to completely similar results from the two models. Thus, we could thus decide to use the equivalent linear actuator without losing reliability.

We also added an additional element to model the bladder capability to exchange heat flux via convection with the H

2 and oil ports and via conduction through the bladder thickness itself (

Figure 6). The general formulations behind the models to calculate the heat flow

h are reported in Equations (

12) and (

13).

Radial conduction through a cylinder with length

l, thickness

, conduction coefficient of the material

and temperature difference

:

Convection using as reference a flat plane geometry and calculation of the heat flow

h as function of the convective coefficient

(expressed through the Nusselt number and conduction coefficient), the equivalent area

and the temperature difference

:

In this way, it is possible to consider the contribution of the mineral oil to the cooling of the hydrogen side in the model. This turned out to be a critical aspect that, if neglected, will lead to the calculation of very high hydrogen temperatures inside the accumulators.

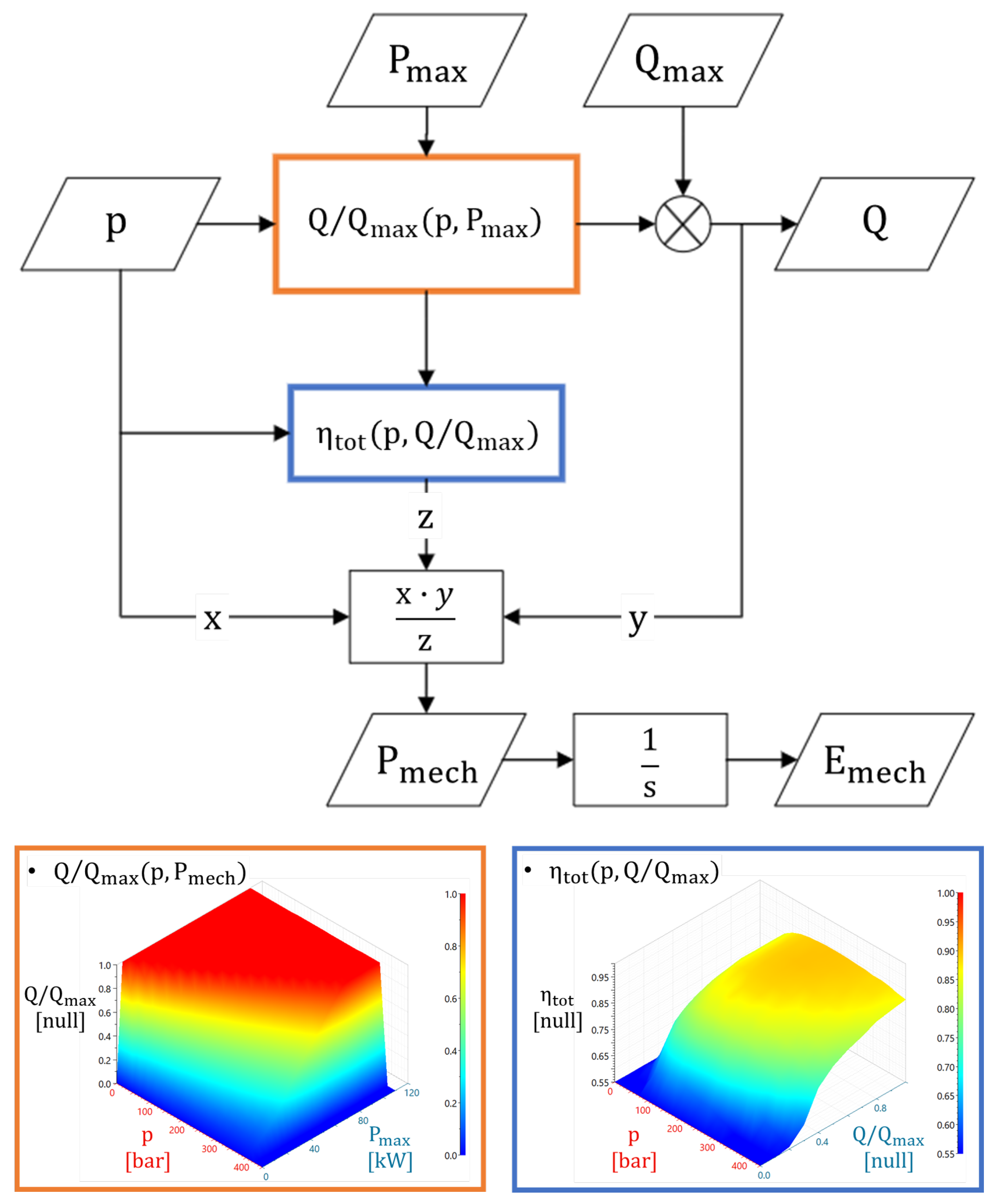

5.2. Pumps and Fluid Power Generator Groups

We considered hydraulic variable displacement pumps to be flow rate generators whose flow rate depends on the displacement regulation. The speed of the pump shaft was considered constant. Displacement control follows a constant power logic. We define the maximum available hydraulic power as reported in Equation (

14):

where

is the hydraulic power,

Q is the volumetric flow rate and

is the pressure difference. Considering relative pressure (tank pressure equals to 0 MPa),

is equal to

, which is the maximum pressure at the pump delivery. The displacement and the delivered flow rate remains at their maximum value until the actual power

reaches the value

. Then, they decrease according to the hyperbola curve of the constant maximum power

. Once the system reaches the maximum pressure

(defined by the pump catalog), the displacement is regulated not to exceed that pressure level. Note that the maximum hydraulic power equals the mechanical power (

Table 1) in an ideal case where the efficiency of the pumps is 1.

Figure 7 graphically illustrates the constant power logic, where

V is the pump displacement and

n the rotational speed of the shaft.

However, it was also important to include the pumps efficiency maps in the model, since the efficiency of hydraulic pumps are influenced by both the operating conditions and the displacement regulation. The latter, in particular, has a strong and negative impact on the pump efficiency especially for displacements lower than 70% of the maximum value.

We considered reference efficiency maps available in the data sheet of some commercial pumps with the appropriate size chosen for the system and tested different combinations. This analysis led us to choose the correct pump size: smaller pumps operating at high displacements, in fact, are preferable to larger pumps that operate at lower displacement, especially for ECU2 where the system reaches higher pressure.

We selected three 180 cc/rev pumps [

32] for ECU1, which needs a higher flow rate to fill the two sets of three accumulators each, and two 71 cc/rev pumps [

33] for ECU2, which operates at a higher pressure and is not designed for low displacements with low efficiencies.

Figure 8 shows how we used pump efficiency maps in the numerical model to evaluate the correct flow rate

Q to deliver towards the accumulators and the compression energy consumption. Starting from the pressure signal

p measured at the pump delivery, the fixed maximum power at the shaft of the pump

and the maximum flow rate

for the selected pump at the desired rotational speed, it is possible to evaluate the actual fractional displacement

(Equation (

15)) and thus the correct flow rate

Q (Equation (

16)) by considering the efficiency at the selected operating point in the 3D maps.

It is also possible to evaluate the total efficiency

(Equation (

17)) from the 3D maps. This value can be used to calculate the actual mechanical power

and energy

for compression, as reported in Equations (

18) and (

19).

We adapted this approach to the different pumps we considered in ECU1 and ECU2, using the corresponding maps [

32,

33].

5.3. Heat Exchangers

Since the type and geometry of the necessary heat exchangers were initially unknown in this first phase, we decided to exploit the model to gain useful information for the sizing of the heat exchangers. This task was assigned to HRS, a partner of the H2REF-DEMO project, which is specialized in hydrogen refueling stations.

Considering a perfect heat exchange with an external temperature source allowed maintaining a desired temperature at the points where these ideal heat exchangers are placed in the model. Note that the desired cooled temperature of the hydrogen is a key design parameter because it determines whether it is possible to perform a fast refueling or not [

15].

In this way, it was possible to estimate the average and maximum heat power

involved in the perfect heat exchange to obtain the desired temperatures. Heat exchangers are considered highly efficient to simplify the discussion. Equation (

20) depicts the calculation of the total work

of the heat exchangers using a coefficient of performance (

) of 3.

The heat exchanger work was then used to evaluate the specific cooling energy during the H2 compression. Moreover, since the model calculates the instantaneous volumetric and mass flow rates, it was also possible to determine the hot/cold fluid mass flow rates involved in the heat exchange. As anticipated, the model was also used to obtain the necessary information to correctly size the heat exchangers and then select the appropriate equipment (heat exchangers and chillers) on the market.

In the model, as well as in the real system, we considered two heat exchangers: one between the two ECUs (called inter-stage heat exchanger) and one upstream the dispensing of hydrogen. The model results also allowed us to compare different positions of the heat exchanger, upstream or downstream the inter-stages buffer, showing the differences of these two design solutions. Positioning the intermediate heat exchanger upstream the inter-stage buffer turned out to be the best solution because it ensures better temperature control and reduces pressure oscillations within the buffer. Moreover, an upstream heat exchanger avoids storing the hydrogen at high temperature after the first compression. Of course, the model of the two heat exchangers can be improved with thermodynamic and heat transfer details once the components have been correctly selected.

Finally, the inter-stage buffer and the final bus tank can naturally exchange heat flow with the external air. We modeled this aspect considering both conduction through the different material layers and convection with the external air and internal hydrogen.

5.4. Fluids/Materials

5.4.1. Hydrogen

Hydrogen was modeled following the Redlich–Kwong–Soave state equation [

34] available in Amesim

®. This model has been validated against the NIST table of properties for Nitrogen (a demo is available in the Help of Amesim

® [

35]).

5.4.2. Mineral Oil

The reference mineral oil is an industrial ISOVG46 oil. This oil has a viscosity grade 46, i.e., its kinematic viscosity is 46 cSt at 40 °C. It is also referenced as HLP46 oil. Amesim

® provides a model that determines the absolute viscosity, specific heat, thermal conductivity, expansion coefficient, density and Bulk Modulus of the fluid as a function of temperature levels using tables [

35]. The dependency on pressure is considered in the so-called equivalent fluid model [

36] implemented in the software. In fact, the system calculates the oil properties as the average properties of liquid, free air if present (pressure lower than the saturation pressure of the gas present in the liquid), liquid vapor if present (pressure at the vapor pressure level), weighted on the volumes of liquid, free air and vapor. Aeration is treated using a modified and dynamic Henry’s law. The vapor mass fraction that appears during cavitation is pressure-dependent only (same behavior as the gas in the aeration model) and follows a polynomial law.

5.4.3. Solid Materials

The elastomer of the bladder was chosen based on experimental tests performed by CETIM (in Senlis, France) and Hydac (in Sulzbach/Saar, Germany) which are partners of the project. The bladder material is characterized with properties listed in a dedicated data file in the model. The density

[kg/m

3], the specific heat at constant pressure

[J/kg/K], and the thermal conductivity

[W/m/K] are described in the file using polynomial regression expressions. The steel used for the accumulator shells and buffer bottles has constant density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity. These properties were provided by Faber [

37], the manufacturer of the shells.

5.5. Control Logic

5.5.1. Accumulator Control

Figure 9a depicts the compression cycle of ECU1a with a source pressure of 5 MPa, which occurs in a series of controlled steps.

Initially, the system starts with filling the accumulator with oil (1). Once the predetermined buffer pressure is reached within the accumulator, the pressure activates a check valve, allowing hydrogen to flow into the buffer (2). Once the accumulator is completely filled with oil, the system starts to fill it with hydrogen from the source while discharging the oil. This process continues until the accumulator is fully filled with gas (3). After the completion of this phase, the system enters a waiting period. During this time, the system remains inactive until the ECU1b bladder is fully compressed (4).

Accumulator control logic is an essential component of our simulation model. It is the set of rules, algorithms and decision processes that manage the correct functioning of the accumulator filling and emptying phases. The logic must switch the hydraulic valves on and off in response to signals from pressure and flow sensors, ensuring the just-presented synchronization of phases.

However, a complete compression of the accumulator is not always necessary. In fact, the control logic should define the compression rate according to different needs (controlling the H

2 maximum temperature, obtaining a nearly constant pressure inside the buffer, ensuring synchronization). For example, in Serial mode, ECU1 can reduce its volumetric efficiency to maintain a constant buffer pressure and decrease fluctuations of the system’s internal pressure even with increased source pressure. Partial compression could lead to more efficient synchronization between the compression units during sequential work.

Figure 9b shows the decrease in ECU1 compression as the source pressure increases (e.g., 9 MPa).

5.5.2. System Control

We developed the control logic to manage the H2REF-DEMO system taking as input the sensor signals (such as pressure and flow counters) and considering as outputs the various system actuations (such as valve supply currents). A simplified control flowchart for the H2REF-DEMO functioning is shown in

Figure 10, where it is possible to identify the main decisions (diamonds) and states (rectangles). Of course, this is just a qualitative flowchart, streamlined to be as clear as possible.

After an initialization phase, during which we must verify that the system is ready to start (with source and tank connected), the control logic enters the filling subgraph and chooses the correct working mode to use in the “check filling” state, as a consequence of the boundary conditions (i.e., source and tank pressure). This check must be performed continuously to ensure that the system switches to the correct working mode when needed.

The control logic selects Bypass mode entering in the corresponding state if the

allows the H

2 to be naturally conveyed to the tank by pressure difference with

. If this condition is not satisfied, the decision to use Parallel or Serial mode is based on whether

is greater than or less than

(Equation (

11)). In this work, in fact, only one compression stage is used until a fixed threshold pressure is reached, independent of the filling conditions. The logic exits the filling loop and returns the system to its idle state once the refueling is completed or if any generic failure or anomaly occurs.

Figure 11 shows the working areas of the three modes under consideration, implementing the strategy with constant threshold pressure. Each point in the plane shows the current boundary conditions of the filling, and each horizontal line represents a filling cycle. Selecting a fixed threshold pressure of 14 MPa, therefore, results in a vertical straight line that serves as the boundary between Parallel and Serial mode.

This strategy optimizes the system for the worst-case scenario of low source pressure.

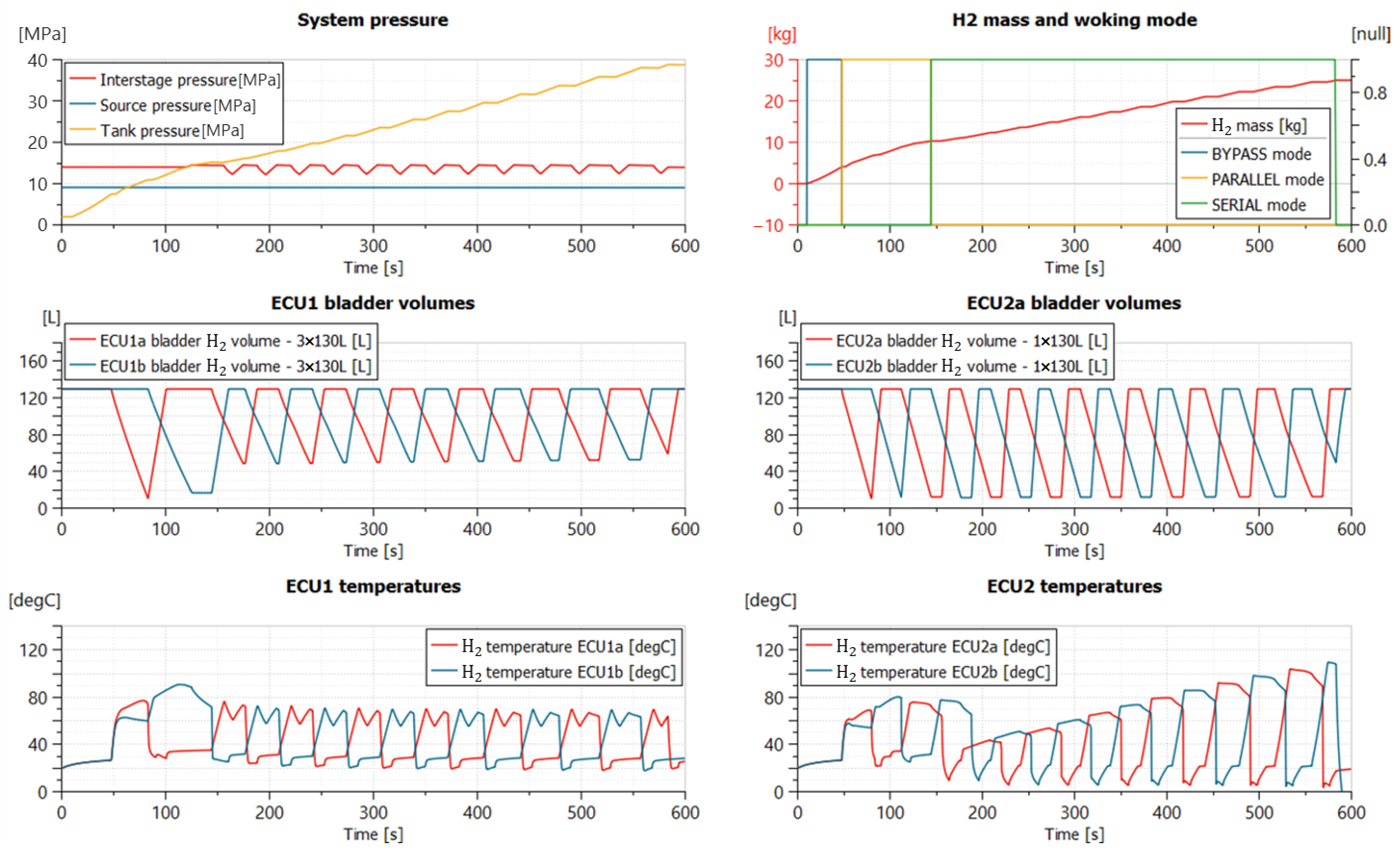

6. Results

We report in this section the main results obtained with the just-presented numerical model of the H2REF-DEMO system simulating the complete refueling of a 1250-L Type IV [

31] tank with 25 kg of H

2. We considered different source pressures (i.e., 5, 9, 11 MPa) in the simulations to analyze the system behavior at different conditions. The system, in fact, must ensure the complete refueling within the target cycle time and with competitive energy consumption under all possible working conditions.

Figure 12 depicts an example of the main numerical results obtained for a refueling cycle simulation. In particular, these data relate to the filling of the 1250-L onboard tank using a 9 MPa H

2 source. The onboard tank is initially almost empty at 2 MPa. Specifically, the main data of interest are:

H2 side volumes of the bladder for ECU1 and ECU2 accumulators,

System pressures, namely:

- –

Source pressure,

- –

Inter-stage pressure,

- –

Onboard tank pressure.

Inner temperatures of ECU1 and ECU2 accumulators,

H2 mass injected into onboard tank and flags indicating the actual mode of the system.

The “System pressure” graph of

Figure 12 clearly illustrates the function of the inter-stage buffer, which must manage the exceeding or missing flow rate between ECU1 and ECU2 causing pressure oscillations.

The “H

2 mass and working mode” graph shows how Serial mode is the predominant filling mode during this refueling cycle. This aspect is emphasized at high source pressure, where Parallel mode can only work within a restricted pressure range from the source to the fixed threshold pressure (i.e., 14 MPa). The choice of a constant threshold pressure also impacts the volumetric efficiency of ECU1, as depicted in the “ECU1 bladder volumes” graph. The selected pressure of 14 MPa, in fact, as stated in the paper, provides a good balance for low pressure source as the ECU1 compression ratio (Equation (

9)) is close to 2.5 ÷ 3. This leads to an almost complete utilization of the ECU1 volumetric efficiency. However, for higher source pressure, the ECU1 volumetric efficiency must drop to meet the fixed threshold pressure, as ECU1 can only compress the hydrogen from the source pressure to this threshold pressure itself.

For example, in the case study with

MPa reported in

Figure 11, the ECU1 volumetric ratio equals to

. This lower ratio results in partial fillings and incomplete compressions of ECU1 bladders in Serial mode, as shown in the “ECU1 bladder volumes” graph already-mentioned.

Table 2 reports the main key performance indicators of the H2REF-DEMO system obtained, simulating a complete refueling cycle starting from the previously mentioned different source pressure (i.e., 5, 9, 11 MPa). We considered both the main performances, such as H

2 flow rate and energy consumption, and the system’s main constraints regarding hydrogen temperatures, which must not exceed fixed values to meet the safety and material requirements [

15].

Analysis of the system behavior at different conditions highlights how the low source pressure scenario represents the worst-case condition, as it takes longer refueling time and requires more overall energy consumption, of course. It was important to validate the performance of the system in the worst-case condition and then to evaluate the advantages in the other situations. Higher source pressures, in fact, ensure both a longer Bypass mode duration and a lower total compression ratio.

We thus obtained encouraging results, both meeting all the system constraints regarding the hydrogen temperatures and proving the system’s performance is competitive compared with the standard technologies. The goal in this first phase, in fact, was not to demonstrate that this system is effectively better than other technologies, but rather that it can achieve competitive consumptions given this specific application and its constraints on refueling time. Moreover, the model can be improved with an optimized logic and further details that we are still missing in this phase, which can make it more accurate regarding the actual energy consumption and more precise for a direct comparison with other technologies.

Figure 13 also shows a comparison between the three considered refueling cycles by using the graph introduced in

Figure 11.

It is easy to note how the three cycles have different Bypass and Parallel phases. In particular, again, the higher the source pressure, the longer the Bypass phase, resulting in a shorter Parallel mode. This occurs because the selected threshold pressure for switching between Parallel and Serial mode was set as constant (i.e., 14 MPa), thus causing an equal Serial mode in all the three simulations.

Note that this is not a digital twin model validated against experimental results of the complete system obtained from the final layout. Instead, it is a numerical tool used properly to support the design and the decision making concerning the main subsystem and components, and the definition and verification of the control logic. In a second phase, when the compression system will be ready to operate, the model can be improved with further details to become a real digital twin. In fact, we are already working to make the model able to interface directly with the PLC controller that will manage the real system. All these aspects can be topics of future work.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented an innovative concept layout for hydrogen compression and refueling using hydro-pneumatic bladder accumulators on which the European project H2REF-DEMO is based.

Starting from the system requirements, as shown, we concurrently designed and developed the system layout and its lumped parameter model. This integrated approach facilitated informed decisions on the system functioning, hardware sizing, and working parameter values. Once we completed the numerical model also integrating the control logic, it was possible to virtually test the compression system under various working conditions to ensure its correct functioning throughout the possible scenarios.

In particular, we reported in this paper the main results concerning three refueling cycles of a 1250-L onboard tank with 25 kg of hydrogen at different source pressures. The results highlighted how the system and the developed control logic adapts to different scenarios, ensuring good numerical results in terms of maximum hydrogen temperatures, average H2 flow rate (and thus refueling time, which is close to 10 min for all the conditions), and most importantly, energy consumption. It is, in fact, mandatory to achieve competitive values of compression and cooling consumption to justify an innovative refueling method with respect to the standard and already-available ones.

Another important aspect to highlight is the modularity of the H2REF-DEMO presented layout. It possible, in fact, to add another compression unit upstream the presented system to compress H2 from the production, usually at 2 MPa, directly to the vehicle tank, while consistently keeping the compression ratio below critical values.

The numerical simulation, however, also highlighted some limits of the actual control logic. The threshold pressure value that defines the transition from Parallel to Serial mode seems to be the main aspect requiring optimization. A constant value, in fact, can be optimized for just one source pressure as done for the worst-case scenario, leading to partial fillings and thus to the non-use of the full volumetric efficiency of the system in all the other pressure values.

We are thus already testing different solutions, with variable threshold pressure optimized according to the current source pressure value. The optimization of this threshold pressure, however, is not a straightforward activity as it must consider as an objective function the improvement of the system consumption, which may not happen by exploiting the full volumetric potential of the system. This new strategy must also be tested and compared with the previous ones to assess the best choice for the KPIs while maintaining a logic that is easy to implement and debug for the next stage of the work in the project, which aims to create the physical refueling station. For these reasons, this optimization will be the subject of an upcoming, ongoing work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli ), B.Z., M.R., E.N., M.B. (Massimo Borghi) and F.B.; methodology, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli), B.Z., M.R. and E.N.; software, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli), B.Z. and M.R.; formal analysis, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli), B.Z., M.R., E.N. and F.B.; investigation, P.K. (Pavel Kučera), P.K. (Peter Kloft), F.E., L.B. and E.S.; data curation, P.K. (Pavel Kučera), P.K. (Peter Kloft), F.E., L.B. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli) and B.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.N., M.B. (Massimo Borghi), F.B., P.K. (Pavel Kučera), P.K. (Peter Kloft), F.E., L.B., R.M. and E.S.; visualization, A.F., M.B. (Matteo Bertoli) and E.N.; supervision, M.B. (Massimo Borghi) and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the H2REF-DEMO project. The H2REF-DEMO project is co-funded by the European Union’s “Horizon. Europe” programme under the “Clean Hydrogen Partnership” (grant agreement No. 101101517).

![Energies 18 06333 i001 Energies 18 06333 i001]()

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all the partners of the project for their important support, which was essential for the completion of this paper. In particular, we thank CETIM (French Technical Center for Mechanical Industries) and Hydac for their precious expertise and work on the bladder of the hydro-pneumatic accumulators. We also thank Faber who provided us with all the fundamental info concerning the gas cylinders and buffers present in the system. Our gratitude extends to H2Nova and HRS for their proven experience in designing hydrogen systems. Their contributions significantly assisted us in determining the final layout. Last but not least, we are also grateful to our colleagues of UTC (Université de Technologie de Compiègne), who provided support during both the design and modeling phases of the system.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Frederic Barth was employed by the company H2Nova. Author Pavel Kučera was employed by the company Faber Industrie. Author Peter Kloft was employed by the company HYDAC Technology GmbH. Author Francis Eynard, Louis Butstraen and Remi Marthelot were employed by the company Hydrogen Refueling Solutions. Author Emmanuel Sauger was employed by the company Technical Center of Mechanical Industries. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cunanan, R.; Tran, M.K.; Lee, Y.; Kwok, S.; Leung, V.; Fowler, M. A Review of Heavy-Duty Vehicle Powertrain Technologies: Diesel Engine Vehicles, Battery Electric Vehicles, and Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles. Clean Technol. 2021, 3, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.M. Encyclopedia of Geochemistry: A Comprehensive Reference Source on the Chemistry of the Earth; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; Press/Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tahan, M.R. Recent advances in hydrogen compressors for use in large-scale renewable energy integration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35275–35292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, M. DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Record; Tech. Report 9013; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Hydrogen Gas Compression for Efficient Storage: Balancing Energy and Increasing Density. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosiak, M.; Karpenko, M. Dynamics of Machines and Hydraulic Systems: Mechanical Vibrations and Pressure Pulsations; Synthesis Lectures on Mechanical Engineering (SLME); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Young, C.; MacKinnon, C.; Layzell, D. The Techno-Economics of Hydrogen Compression. Transit. Accel. Tech. Briefs 2021, 1, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sdanghi, G.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Towards Non-Mechanical Hybrid Hydrogen Compression for Decentralized Hydrogen Facilities. Energies 2020, 13, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Dong, T. Improvement of hydrogen reciprocating compressor efficiency: A novel capacity control system and its multi-objective optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jia, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, B.; Peng, X. Effect of hydraulic oil compressibility on the volumetric efficiency of a diaphragm compressor for hydrogen refueling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 92, 15224–15235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, G.; Shen, L.; Liao, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of hydraulic oil viscosity on the operational performance of ultra-high-pressure hydrogen diaphragm compressors. Energy 2025, 330, 136955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.; Muthukumar, P.; Dalal, A. A review on non-mechanical hydrogen compressors for hydrogen refuelling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 145, 292–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IC50-P/60 Ionic Compressor; Catalogue. Linde: Dublin, Irland, 2021.

- J2601/2_202307; Fueling Protocol for Gaseous Hydrogen Powered Heavy Duty Vehicles. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023.

- Sun, H.; Zhou, H.; Dong, P.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, S. Study on the control of piston motion trajectory in ionic liquid hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 112, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liao, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Feng, J.; Peng, X. Multi-objective optimization of the gas valve and liquid piston in the ionic liquid hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 118, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornheim, M.; Baetcke, L.; Akiba, E.; Ares, J.R.; Autrey, T.; Barale, J.; Baricco, M.; Brooks, K.; Chalkiadakis, N.; Charbonnier, V.; et al. Research and development of hydrogen carrier based solutions for hydrogen compression and storage. Prog. Energy 2022, 4, 042005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansores, G.M.; García, J.L.; Arriaga, L.G.; Cruz, J.C.; Gurrola, M.P. Research progress on components and design variables in electrochemical hydrogen compressor: An analytical review. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2025, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Keuschnigg, C.; Grabner, B.; Macherhammer, M.; Trattner, A. Investigation of favourable operating conditions for electrochemical hydrogen compressors by 3D CFD simulation and single cell tests. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 185, 150251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Review of the current technologies and performances of hydrogen compression for stationary and automotive applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 102, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Hwang, W.S.; Choi, H. Can hydrogen fuel vehicles be a sustainable alternative on vehicle market?: Comparison of electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 143, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrukovs, V.; Bezrukovs, V.; Konuhova, M.; Bezrukovs, D.; Kaldre, I.; Berzins, A. R&D of a Hydraulic Hydrogen Compression System for Refuelling Stations. Latv. J. Phys. Tech. Sci. 2023, 60, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, Q.; Xiong, W.; Peng, X. Experimental investigation on the hydraulic-driven piston compressor for hydrogen under varied operating conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 74, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Ren, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Jia, X.; Peng, X. Thermodynamic performance optimization of two-stage hydraulic-driven piston hydrogen compressors based on variable speed control method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 145, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah Koojehri, M.; Singh, A.; Munshi, S.; McTaggart-Cowan, G. Exergy Analysis of an On-Vehicle Floating Piston Hydrogen Compression System for Direct-Injection Engines. Energies 2025, 18, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H2REF-DEMO Grant Agreement, Project N. 101101517. 2023. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101101517 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- European Commission. Development of a Cost Effective and Reliable Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicle Refuelling System; H2REF Final Public Report, Project N. 671463; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hydac. Bladder Accumulator Technology; Catalogue; Hydac: Sulzbach, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vacca, A.; Franzoni, G. Hydraulic Fluid Power: Fundamentals, Applications, and Circuit Design; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Shi, Z.; Lin, J. Review of common hydrogen storage tanks and current manufacturing methods for aluminium alloy tank liners. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2024, 7, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch Rexroth. Electro-Hydraulic Control with Proportional Solenoid EP, A4VSG Series; Catalogue; Bosch Rexroth: Lohr am Main, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch Rexroth. Axial Piston Variable Pump, A4VBO Series; Catalogue; Bosch Rexroth: Lohr am Main, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soave, G. Equilibrium constants from a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1972, 27, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Help Manual, Simcenter Amesim. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/simcenter/systems-simulation/amesim/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Technical Bulletin B117: HYD Advanced Fluid Properties, Simcenter Amesim. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/simcenter/systems-simulation/amesim/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Faber Industrie. Hydrogen Storage and Transportation; Catalogue; Faber Industrie: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).