Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Refrigerated Spaces: A Comparative Study of Experiments, CFD Predictions and Heat Load Software Accuracy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Refrigerator Model

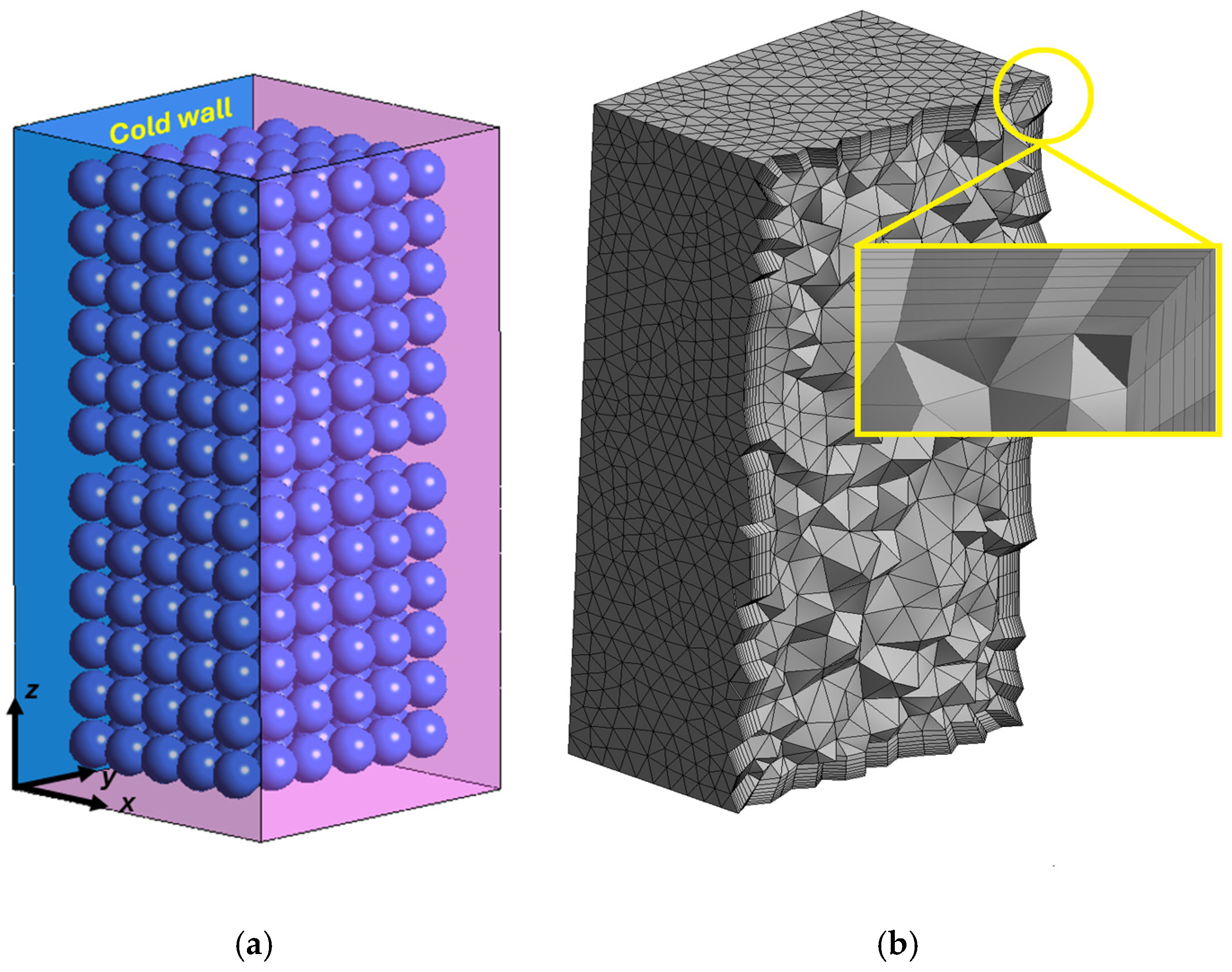

2.2. The CFD Model

2.3. CFD Set-Up

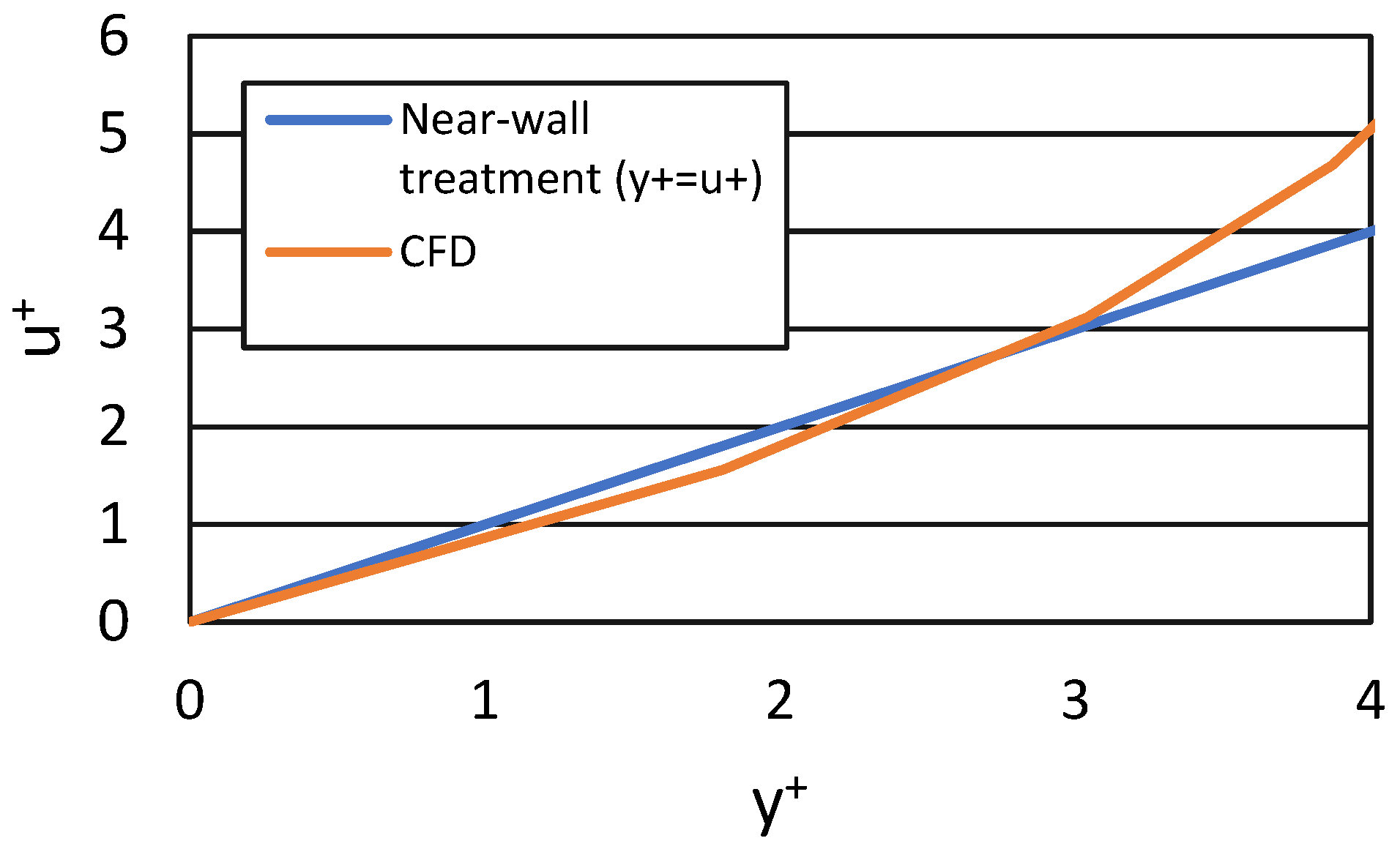

2.3.1. Turbulence

2.3.2. Buoyancy

2.3.3. Radiation

2.3.4. Boundary Conditions

2.3.5. Grid Generation

2.3.6. Grid Independence Study

2.3.7. Numerical Solution Algorithm and Solver Settings

3. Results and Discussion

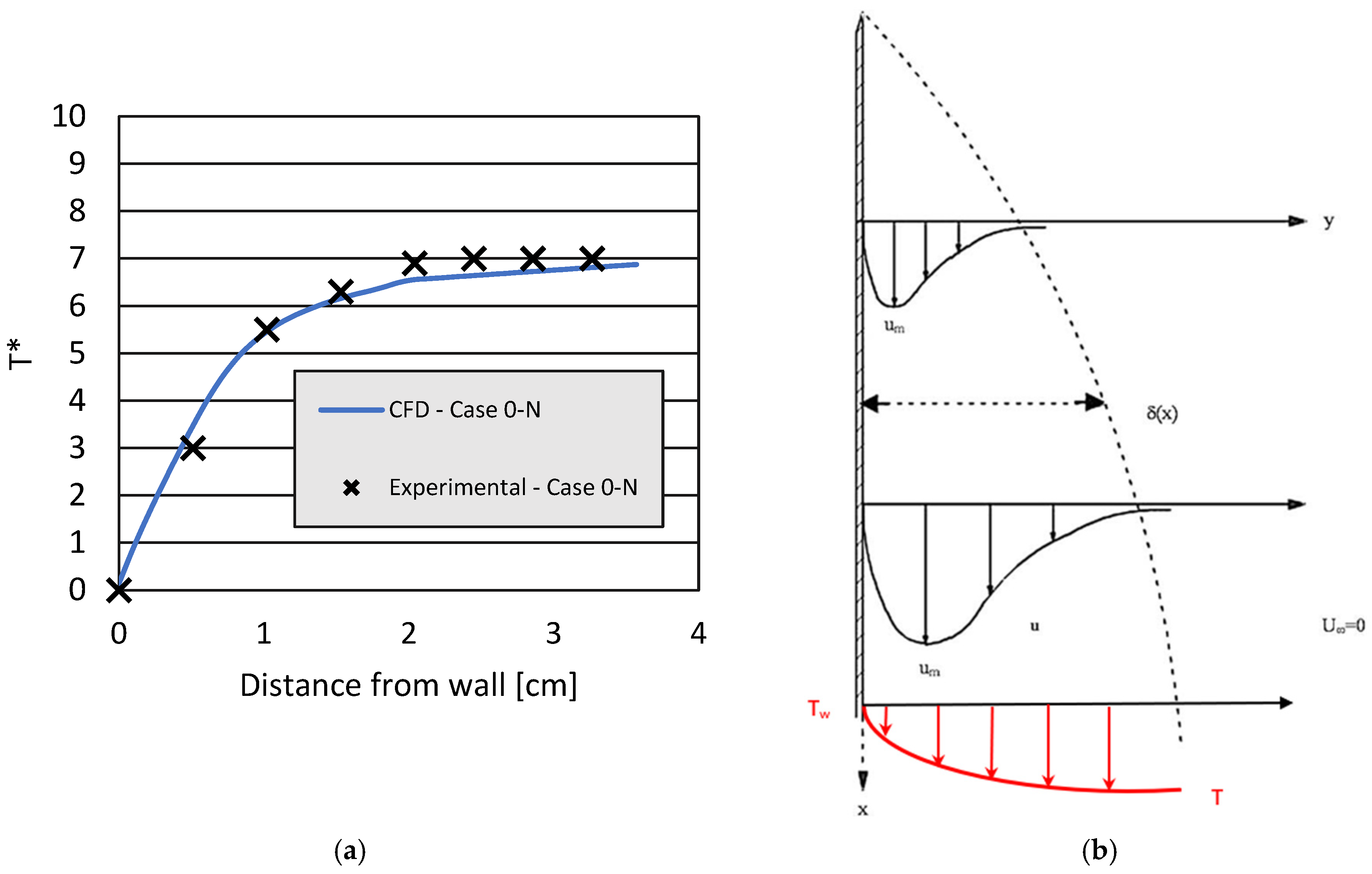

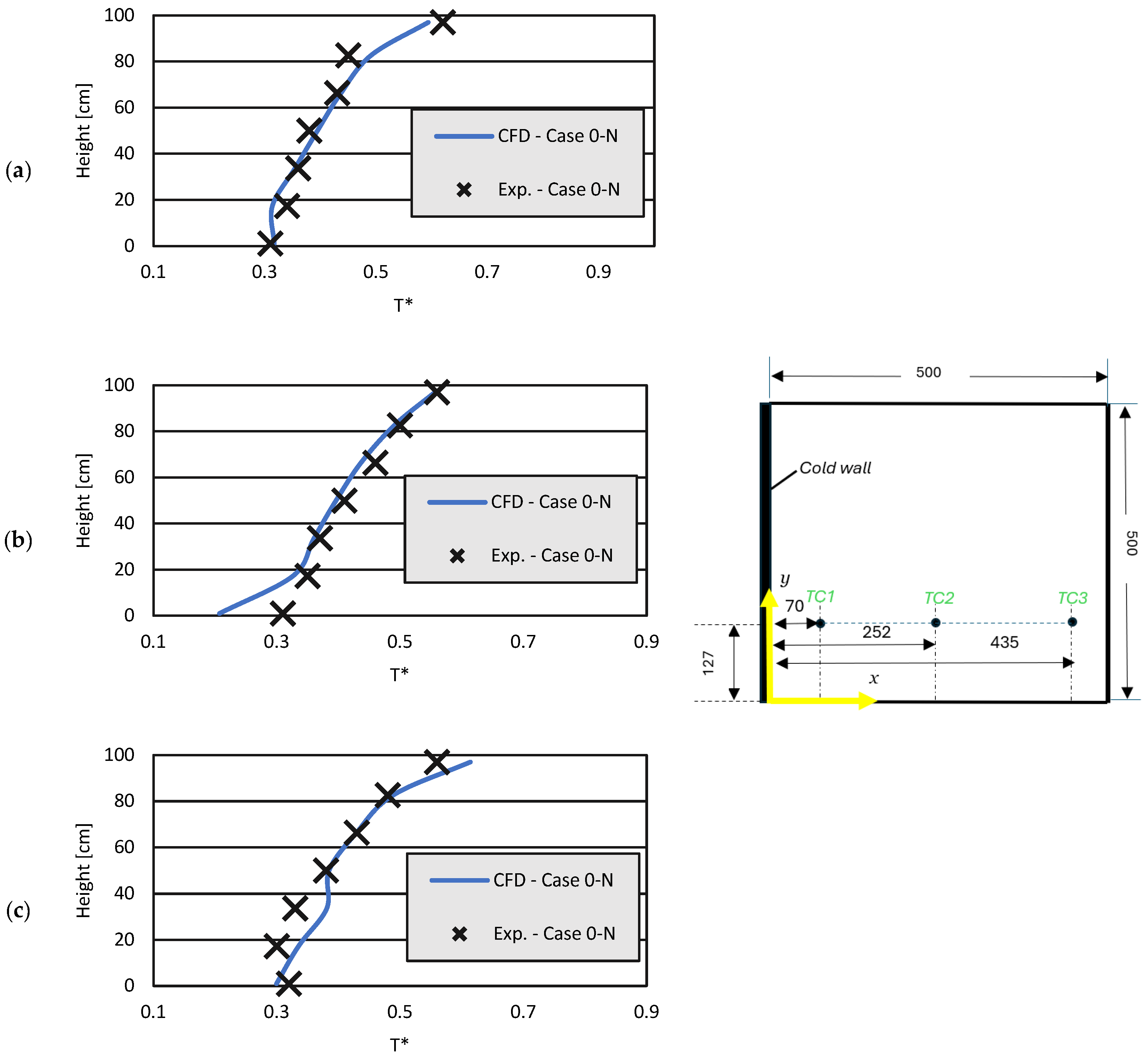

3.1. Case 0-N

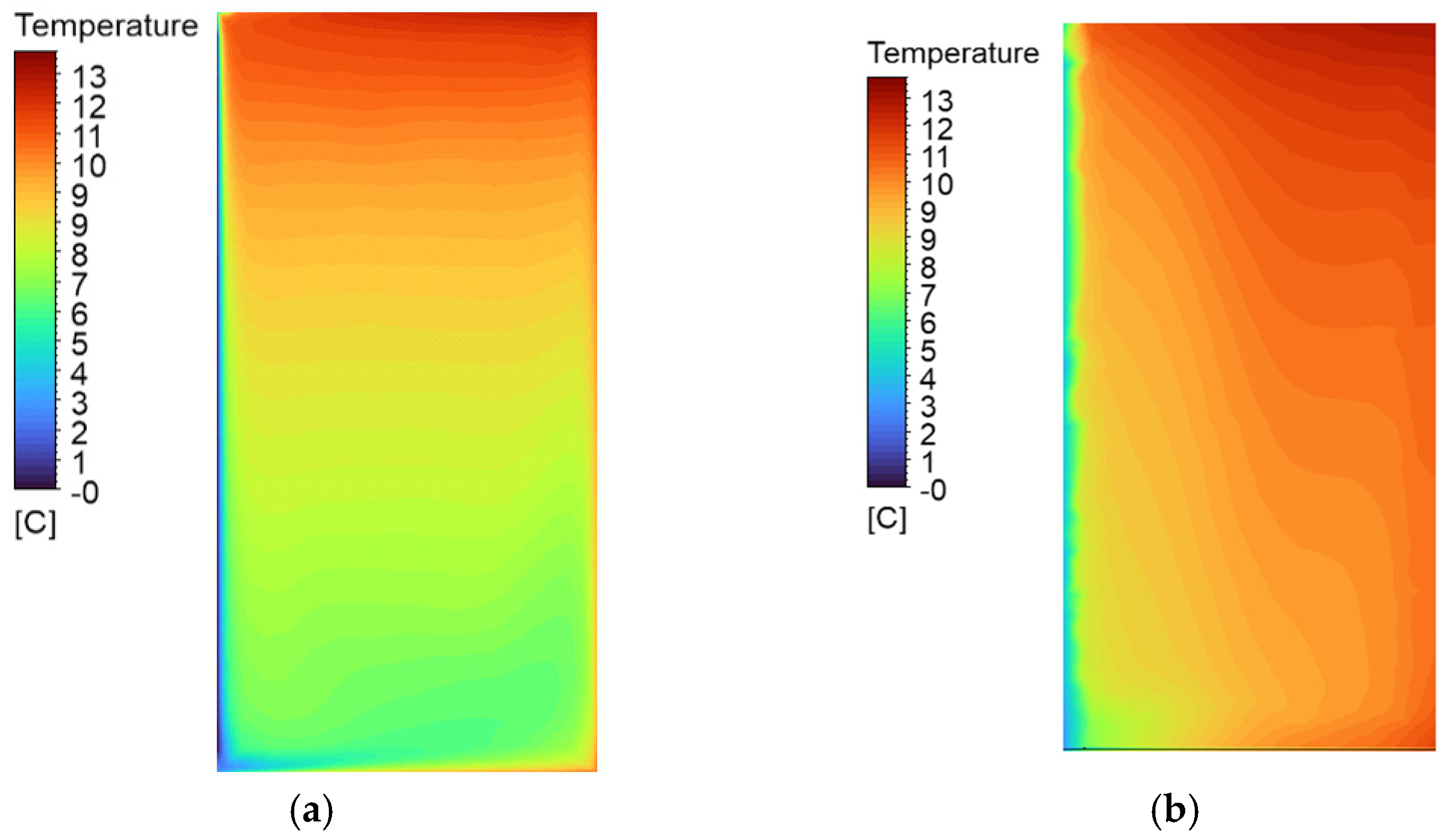

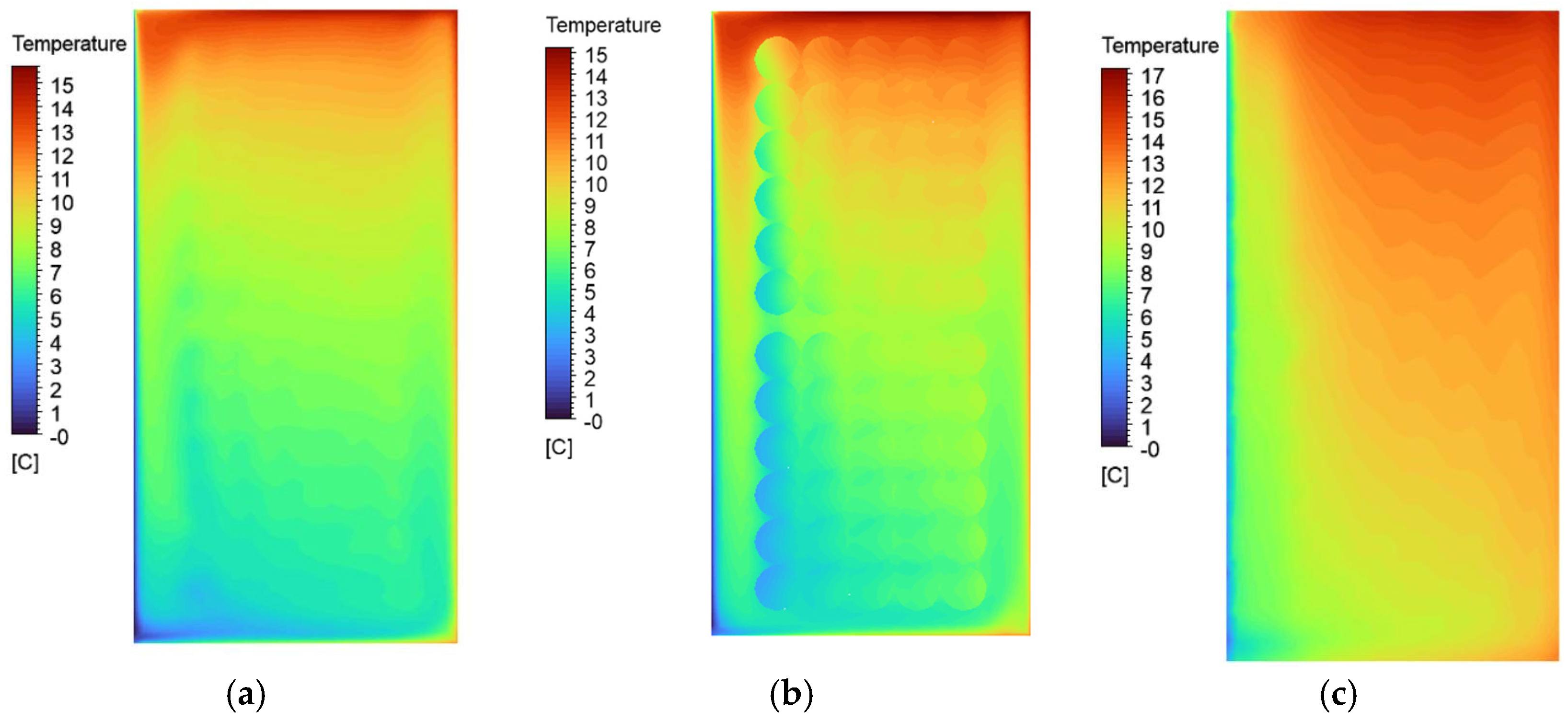

3.1.1. Temperatures

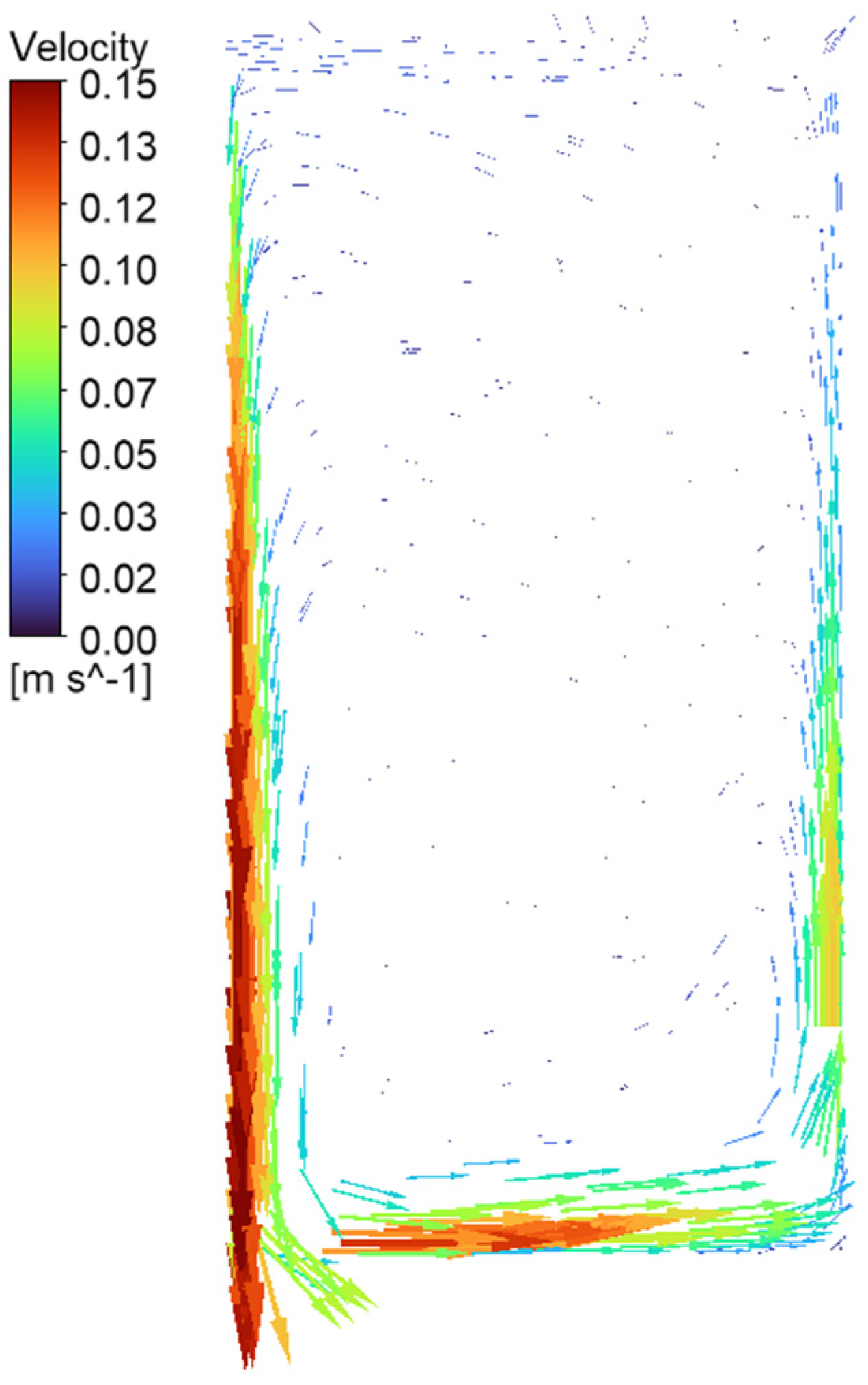

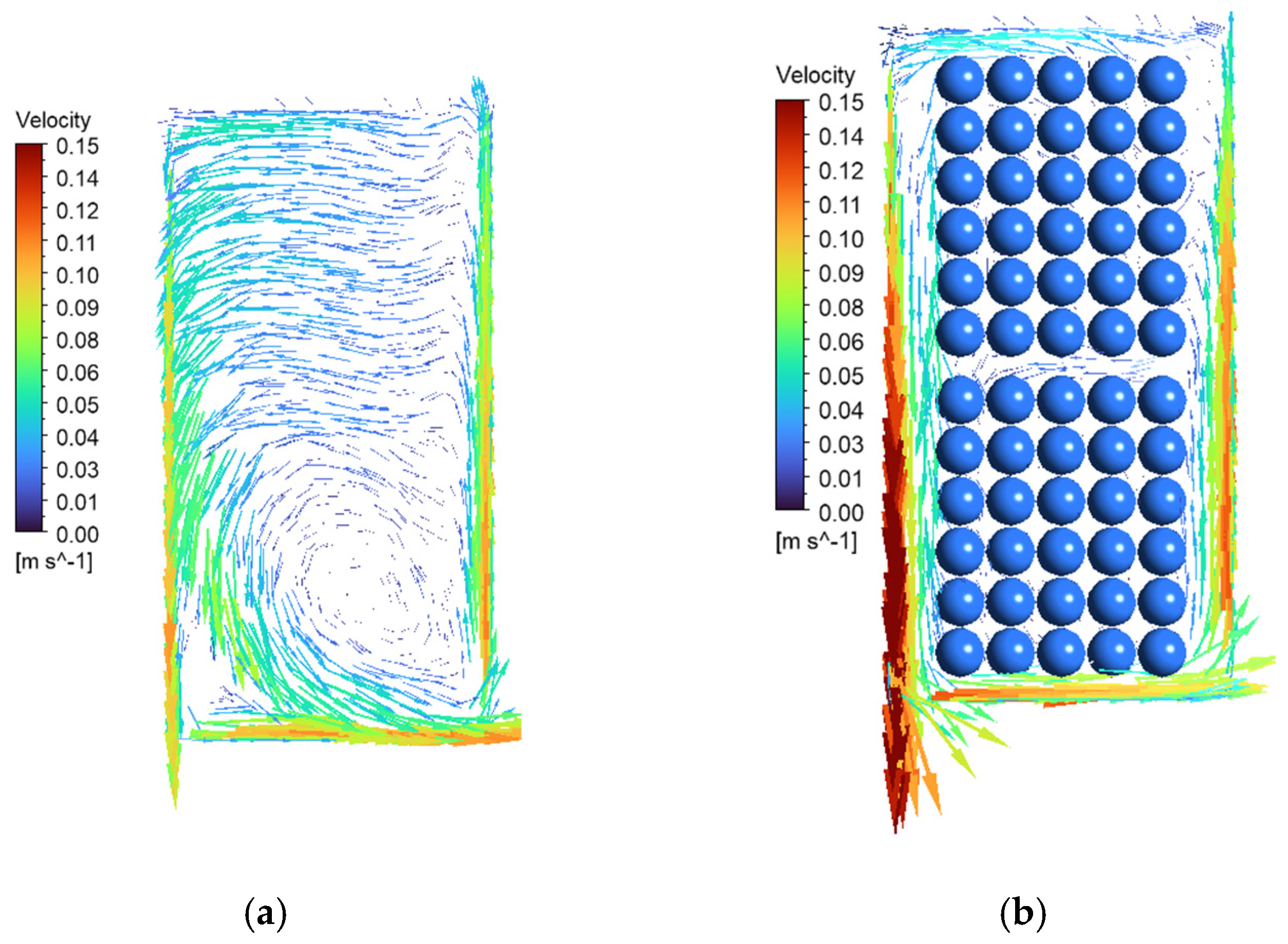

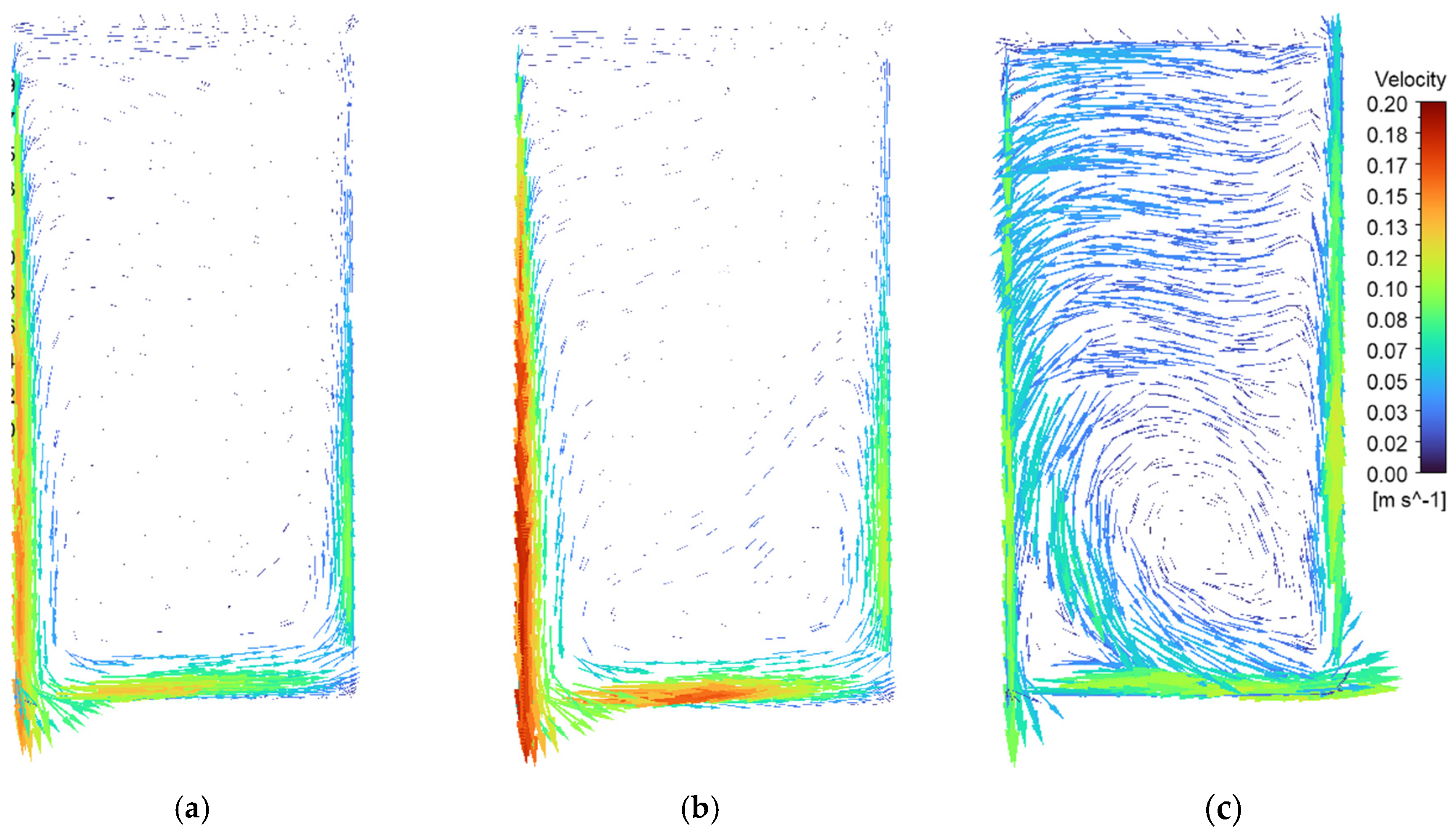

3.1.2. Air Velocity

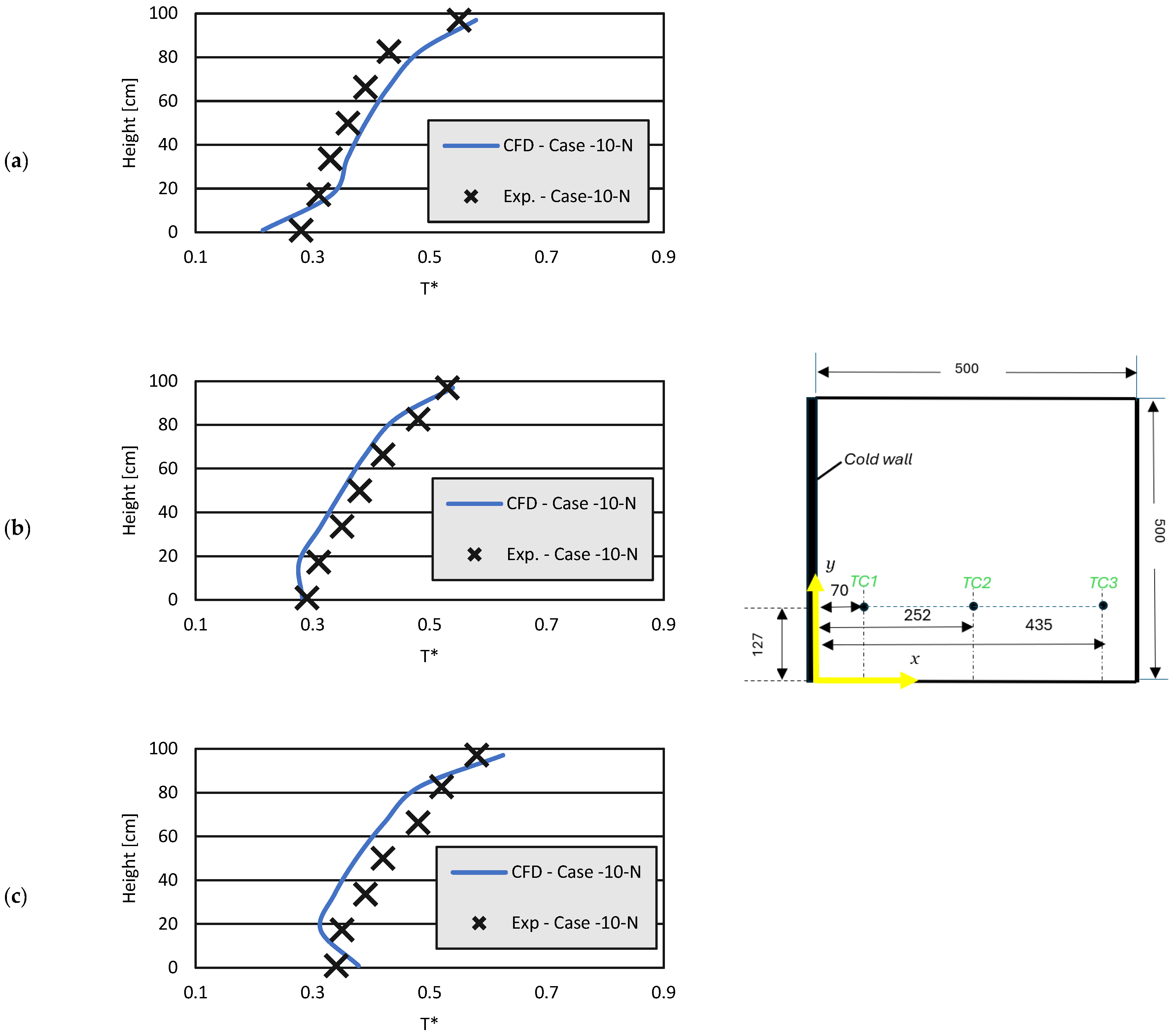

3.2. Case −10-N

3.2.1. Temperatures

3.2.2. Air Velocity

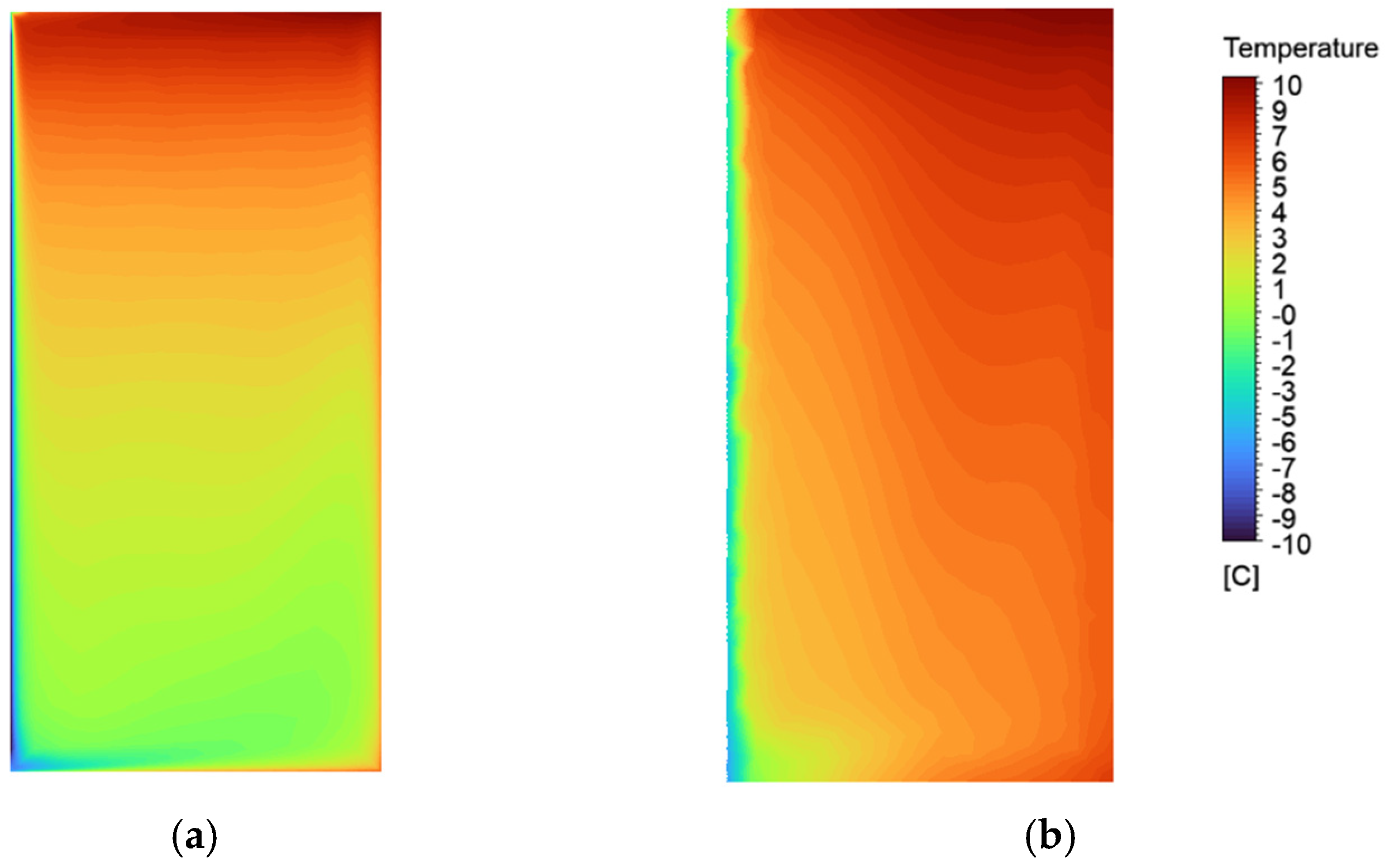

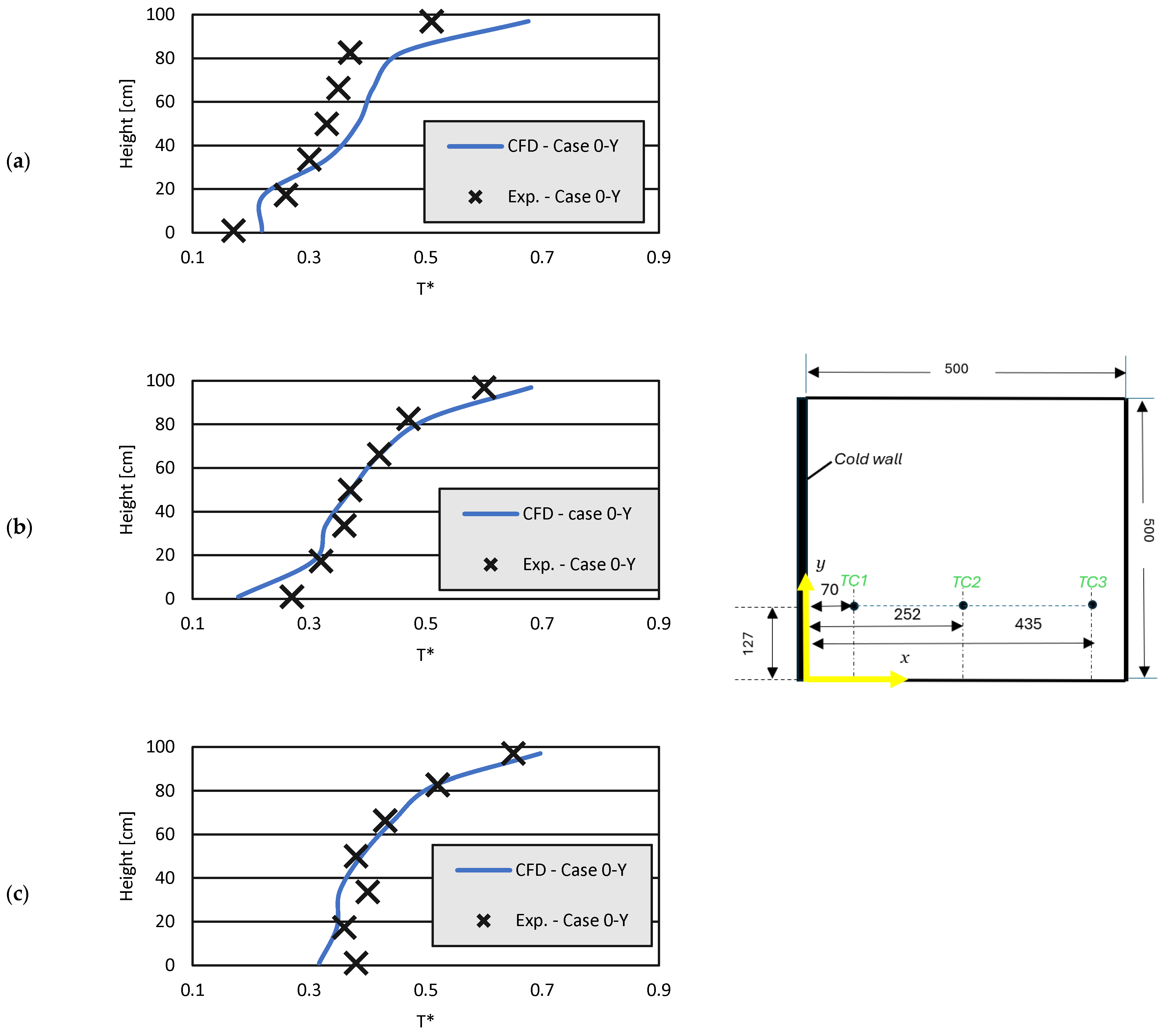

3.3. Case 0-Y

3.3.1. Temperatures

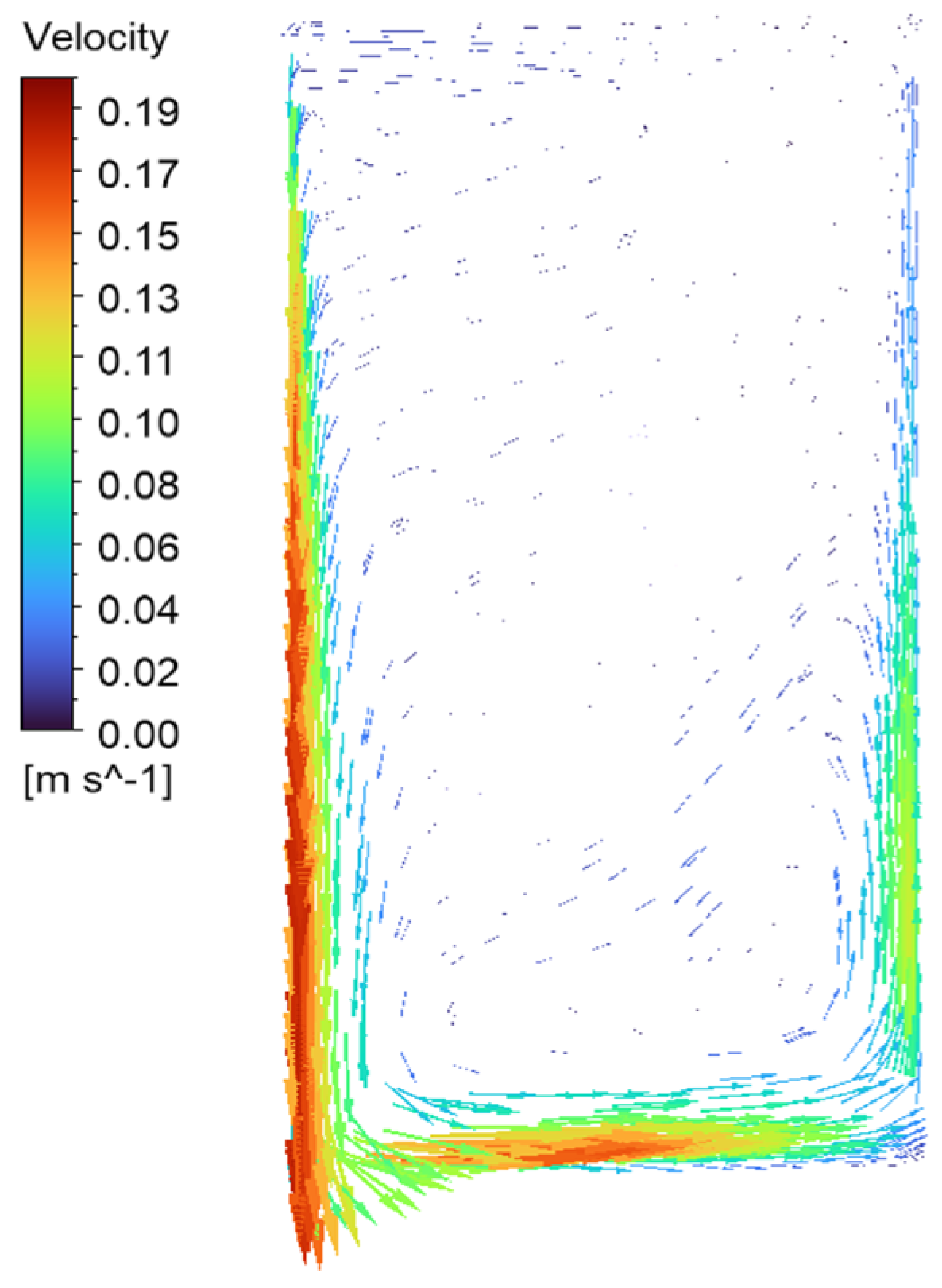

3.3.2. Air Velocity

3.4. Heat Transfer

Reference Temperatures

4. Tools for Estimating Heat Loads in Cold Rooms

- Enclosure surfaces;

- Product cooling;

- Product respiration;

- Infiltration of surrounding air;

- Electric lighting;

- Heat of people;

- Fans of air coolers.

4.1. Considered Software for Heat Load Estimation

4.2. Limitations of Heat Load Calculation Software Compared to CFD

4.3. Software Heat Load Calculations

5. Conclusions

- Case 0-N shows an air temperature difference of 54% between the top and bottom zones of the refrigerator and velocities of 0.15 m/s near to the cold wall. Strong velocity gradients are found between the peripheral zones and the central zone where the air is nearly stagnated.

- Case 10-N presents a maximum temperature of 8.7 °C, which is lower than the 12.3 °C found in case 0-N but still unacceptable for the conservation of sensitive foods like dairy products, for example. Air velocities are 26% higher than in case 0-N at the same zone near the cold wall. Despite the great Ra compared to case 0-N, a laminar flow regime still holds in this case.

- The highest air temperatures are observed in case 0-Y, with 14 °C being found at the top of the cavity.

- The prediction of heat transfer coefficients is strongly dependent on the expression used for its calculation. Convection coefficients oscillate between 1.3 and 2.8 W/m2 °C for case 0-N. The calculated radiation coefficients appear to show more consistent results among the different expression methods used. Figures between 4.2 and 4.4 W/m2 °C are reported for the same case.

- When comparing the results for the heat gain estimation from software normally used for cold room design, high discrepancies are shown. Percentage differences of 102% were found when comparing one of these tools with CFD simulations. This discrepancy in simulation results may introduce a considerable amount of uncertainty in the process of sizing an evaporator.

- -

- Experimental Validation of CFD Results

- -

- Humidity and Moisture Transfer Analysis

- -

- Optimization of Airflow and Evaporator Placement

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHRAE | The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| TAWA | Temperature Area-Weighted Average |

| TC | Thermocouple |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning |

References

- Laguerre, O.; Ben Amara, S.; Flick, D. Experimental Study of Heat Transfer by Natural Convection in a Closed Cavity: Application in a Domestic Refrigerator. J. Food Eng. 2004, 70, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, E. Why Identifying the Warm and Cold Zones in Your Fridge is the Actual Key to Meal Prep Success. Available online: https://www.wellandgood.com/food/fridge-warm-cold-zones (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kinoshita, D.; Gashe, J. 21st Brazilian Congress of Mechanical Engineering. In COBEM 2011; ABCM: Natal, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, H. CFD simulation of velocity and temperature distribution inside refrigerator compartment. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 4199–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A. Convection Heat Transfer; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Vahl Davis, G. Natural convection of air in a square cavity: A bench Mark Numerical Solution. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1983, 3, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amara, S.; Laguerre, O.; Charrier-Mojtabi, M.-C.; Lartigue, B.; Flick, D. Piv measurement of the flow field in a domestic refrigerator model: Comparison with 3D simulations. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, O. Heat transfer and air flow in a domestic refrigerator. In Mathematical Modeling of Food Processing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 453–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logeshwaran, S.; Chandrasekaran, P. CFD analysis of natural convection heat transfer in a static domestic refrigerator. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1130, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I.A. State-of-the-art CFD simulation: A review of techniques, validation methods, and application scenarios. J. Recent Trends Mech. 2024, 9, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeng, J.; Gonçalves, J.M. Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Heat Storage Material Integration in Household Refrigerators. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 173, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunker, L.; Tassou, S.; Raeisi, A. Numerical study of the thermal performance of well freezer cabinets. Refrig. Sci. Technol. 2014, 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Lian, Y. Numerical Investigation of Heat Transfer and Flow Field in Domestic Refrigerators. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2013, 55546, V01AT03A003. [Google Scholar]

- Muneeshwaran, M.; Yang, C.-M.; Nawaz, K.; Wang, C.-C. Understanding Airflow Pattern and Temperature Distribution in Domestic Refrigerators–A Review Analyzing Recent Developments and Bridging Knowledge Gaps. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiwar, A.; Khute, N. Cooling load calculation of a room with different design temperature by analytical method and analysed by ANSYS (fluent). Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2025, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tore, H.; Kilicarslan, A. Numerical and experimental investigation of condensation phenomenon in a commercial condenser with different outdoor air temperatures and refrigerants. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnig, D.; Reindl, D.; Klein, S.A. Semi-empirical method for representing domestic refrigerator/freezer compressor calorimeter test data. ASHRAE Trans. 2000, 106 Pt 2. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, H.; Armstrong, P. Reciprocating and screw compressor semi-empirical models for establishing Minimum Energy Performance Standards. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 90, 012077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Al-Abadi, A.; Wu, W.A. Combined Computational Fluid Dynamics and Thermal–Hydraulic Modeling Approach for Improving the Thermal Performance of Corrugated Tank Transformers: A Comparative Study. Energies 2024, 17, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Dai, Y.; Hu, H.A. Simplified Cooling Load Calculation Method Based on Equivalent Heat Transfer Coefficient for Large Space Buildings with a Stratified Air-Conditioning System. Energy Build. 2023, 293, 113370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwocha, C.L.; Tsige, A.A.; Fadiji, T.; Opara, U.L. CFD-Based Analysis of the Cooling Capacity of a Refrigerated Container as a Function of Produce Loading Temperature. Acta Hortic. 2022, 1349, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Davies, G.F.; Evans, J.A.; Maidment, G.G.; Wood, I.D. Theoretical Modelling and Experimental Investigation of a Thermal Energy Storage Refrigerator. Energy 2013, 55, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ama Gonzalo, F.; Santamaria, B.; Burgos, M.J.M. Assessment of Building Energy Simulation Tools for Heating and Cooling Load Predictions: Annual, Monthly and Hourly Comparisons. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghelli, J.M.; Nascimento, A.A.; Mariano, F.P. Thermal Comfort Analysis of HVAC Systems Using Full CFD Open-Source Software. Preprints 2024, 2024102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.A.; Rasul, M.G.; Khan, M.M.K. Thermal Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Building Using an Integrated Energy and Computational Fluid Dynamics (IE-CFD) Approach. Energy Rep. 2022, 8 (Suppl. S16), 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çengel, Y.A. Heat Transfer: A Practical Approach; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, S.; Salvetti, M.V.; Rodriguez, I.; Lehmkuhl, O. Progress in engineering turbulence modelling and measurement. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2025, 115, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivoli, R.; Pugh, D.; Goktepe, B.; Bowen, P.J. Modeling of Roughness Effects on Generic Gas Turbine Swirler via a Detached Eddy Simulation Low-y+ Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, H.; Hultmark, G.; Rahnama, S.; Maccarini, A.; Afshari, A. Performance Evaluation of Active Chilled Beam Systems for Office Buildings–A Literature Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lança, M.; Cabral, D.; Gomes, J. Thermal Performance of Three Concentrating Collectors with Bifacial Photovoltaic Cells Part I–Experimental and Computational Fluid Dynamics Study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2023, 238, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, O.; Flick, D. Heat Transfer by Natural Convection in Domestic Refrigerators. J. Food Eng. 2003, 62, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L.; Incropera, F.P. Fund. of Heat and Mass Transfer, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Lage, J.L.; Junqueira, S.L.M.; Franco, A.T. Berkovsky-Polevikov Correlations for Natural Convection in a Nonhomogeneous Enclosure Filled With a Fluid and Disconnected-Conducting Solid Particles. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2012, 44779, 609–615. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Saidur, R.; Masjuki, H.H. Effects of operating variables on heat transfer and energy consumption of a household refrigerator-freezer during closed door operation. Energy 2009, 34, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Handbook-Refrigeration; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, I. 3-Interphase Transport and Transfer Coefficients. In Modelling in Transport Phenomena; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 35–57. ISBN 9780444530219. [Google Scholar]

- Acikgoz, O.; Kincay, O. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of the Correlation between Radiative and Convective Heat-Transfer Coefficients at the Cooled Wall of a Real-Sized Room. Energy Build. 2015, 108, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo Costa, N.; Garcia, J. Applying design of experiments to a compression refrigeration cycle. Cogent Eng. 2015, 2, 992216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciconkov, R. Computer Program for Load Calculation of Coldrooms, with Incorporated Databases and Recommendations. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2020, UDC 664.045.5, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- HVACR Advisors. Available online: https://hvacradvisors.com/Home/Apps (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- KeepRite Refrigeration. Available online: https://loadcalc.k-rp.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Intarcon. Available online: https://client360.intarcon.com/en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Foster, A.M.; Barrett, R.; James, S.J.; Swain, M.J. Measurement and prediction of air movement through doorways in refrigerated rooms. Int. J. Refrig. 2002, 25, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Gao, Y.; Shao, S.; Xu, H.; Tian, C. Development of an unsteady analytical model for predicting infiltration flow rate through the doorway of refrigerated rooms. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 129, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, R.; Gaspar, P.D.; Silva, P.D. 3D and transient numerical modelling of door opening and closing processes and its influence on thermal performance of Cold Rooms. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Code | Cold Wall Temperature | Existence of Spheres Inside the Model? |

|---|---|---|

| Case 0-N | 0 °C | No |

| Case −10-N | −10 °C | No |

| Case 0-Y | 0 °C | Yes |

| Dimensions | TC Column 1 | TC Column 2 | TC Column 3 | TC Row 4 | TC Row 5 | TC Row 6 | Plane 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | 0–500 | 7 | 252 | 435 | 5;10;15;20;25;30;35;40;45;150;300;400;450;500 | - | ||

| y | 0–500 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 250 | 250 | 250 | y = 250 |

| z | 0–1000 | 2;17;34;50;66;83;97 | 100 | 500 | 900 | - | ||

| Zone | Case 0-N/Case −10-N/Case 0-Y |

|---|---|

| Cold wall | NWT/NWT/NWT |

| Side walls | NWT/NWT/NWT |

| Top and bottom walls | NWT/NWT/NWT |

| Spheres | n.a./n.a./NWT |

| Zone | Case 0-N/Case −10-N/Case 0-Y |

|---|---|

| Cold wall | Prescribed wall temperature + convection + radiation/Prescribed wall temperature + convection + radiation/Prescribed wall temperature + convection + radiation |

| Side walls | Convection + radiation/Convection + radiation/Convection + radiation |

| Top and bottom walls | Convection + radiation/Convection + radiation/Convection + radiation |

| Spheres | Adiabatic/Adiabatic/Adiabatic |

| Wall Type | Material | Heat Transfer Coefficient (Outer Surface) [W/m2 °C] | Emissivity (Inner Surface) | Emissivity (Outer Surface) | Thermal Conductivity [W/m °C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side walls | XPS + Glass | 3.5 | 0.85 | 0.8 | 0.09 |

| Top and bottom wall | XPS + PVC | 2.5 | 0.90 | 0.8 | 0.08 |

| Cold wall | Aluminum + XPS | Calculated | 0.31 | 0.8 | 0.07 |

| Number of Elements | Element Max Size [m] | TAWA [°C] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFD | Experimental | ΔTAWA [°C] | ||

| 181,442 | 0.02 | 7.82 | 8.01 | 0 |

| 72,734 | 0.03 | 7.81 | −0.01 | |

| 55,456 | 0.04 | 7.75 | −0.07 | |

| 24,254 | 0.06 | 7.64 | −0.18 | |

| Case 0-N | |||||||||

| Author(s)/method | Ra | Nu | Heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2 °C)] | Heat flux rate [W] | Reference temperature [°C] | ||||

| Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | ||||

| Convection | Incropera and Dewitt [32] | 5.16 × 108 | 78 | 2.2 | - | 9.1 | - | 8.2 | - |

| Vertical flat plates | 5.16 × 108 | 89 | 2.5 | - | 10.2 | - | 8.2 | - | |

| Çengel [26] | 5.16 × 108 | 100 | 2.8 | - | 11.5 | - | 8.2 | - | |

| Qiu et al. [33] | 5.16 × 108 | 56 | 1.6 | - | 6.5 | - | 8.2 | - | |

| Hasanuzzaman et al. [34] | n.a. | 33 | 1.3 | - | 5.3 | - | 8.2 | - | |

| ASHRAE [35] | n.a. | n.a. | 1.6 | - | 14.2 (a) | - | 8.2 | - | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | 3.2 | - | 13.1 | - | 8.2 | - | |

| Radiation | Laguerre and Flick [1] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.2 | - | 22.9 | - | 11.2 |

| Tosun [36] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.4 | - | 24.2 | - | 11.2 | |

| Acikgoz and Kincay [37] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.3 | - | 23.7 | - | 11.2 | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | - | 3.8 | - | 21.2 | - | 11.2 | |

| Case −10-N | |||||||||

| Author(s)/method | Ra | Nu | Heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2 °C)] | Heat flux rate [W] | Reference temperature [°C] | ||||

| Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | ||||

| Convection | Incropera and Dewitt [32] | 7.43 × 108 | 86 | 2.4 | - | 14.1 | - | 1.8 | - |

| Vertical flat plates | 7.43 × 108 | 97 | 2.7 | - | 16.1 | - | 1.8 | - | |

| Çengel [26] | 7.43 × 108 | 111 | 3.1 | - | 18.4 | - | 1.8 | - | |

| Qiu et al. [33] | 7.43 × 108 | 63 | 1.8 | - | 10.3 | - | 1.8 | - | |

| Hasanuzzaman et al. [34] | n.a. | 33 | 1.3 | - | 7.7 | - | 1.8 | - | |

| ASHRAE [35] | n.a. | n.a. | 1.6 | - | 21.8 (a) | - | 1.8 | - | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | 4.2 | - | 25.1 | - | 1.8 | - | |

| Radiation | Laguerre and Flick [1] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 3.8 | - | 26.5 | - | 5.4 |

| Tosun [36] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.1 | - | 28.1 | - | 5.4 | |

| Acikgoz and Kincay [37] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.3 | - | 29.8 | - | 5.4 | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | - | 3.8 | - | 29.4 | - | 5.4 | |

| Case 0-Y | |||||||||

| Author(s)/method | Ra | Nu | Heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2 °C)] | Heat flux rate [W] | Reference temperature [°C] | ||||

| Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | Conv. | Rad. | ||||

| Convection | Incropera and Dewitt [32] | 4.91 × 108 | 77 | 2.2 | - | 8.4 | - | 7.8 | - |

| Vertical flat plates | 4.91 × 108 | 88 | 2.5 | - | 9.6 | - | 7.8 | - | |

| Çengel [26] | 4.91 × 108 | 98 | 2.8 | - | 10.7 | - | 7.8 | - | |

| Qiu et al. [33] | 4.91 × 108 | 55 | 1.6 | - | 6.0 | - | 7.8 | - | |

| Hasanuzzaman et al. [34] | n.a. | 33 | 1.3 | - | 5.1 | - | 7.8 | - | |

| ASHRAE [35] | n.a. | n.a. | 1.6 | - | 9.76 (a) | - | 7.8 | - | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | 5.7 | - | 22.4 | - | 7.8 | - | |

| Radiation | Laguerre and Flick [1] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.4 | - | 22.9 | - | 11.5 |

| Tosun [36] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.4 | - | 22.9 | - | 11.5 | |

| Acikgoz and Kincay [37] | n.a. | n.a. | - | 4.3 | - | 22.2 | - | 11.5 | |

| CFD prediction | n.a. | n.a. | - | 3.1 | - | 17.8 | - | 11.5 | |

| Software | Main Application | Type of Calculation | Level of Detail | Equipment Selection | Cost | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVACR WICF | Walk-in coolers and freezers (small and medium cold rooms) | Total heat load (transmission, infiltration, product) | Basic to intermediate | Yes, based on generic data | Usually paid | Complies with DOE (USA) standards; recommended for quick design of cold rooms. |

| KR LoadCalc | Cold rooms and refrigerated warehouses | Total heat load | Basic | Yes, linked to KeepRite products | Free (with registration) | Aimed at contractors; limited to the brand’s equipment portfolio. |

| Intarcon Client360 | Commercial and industrial refrigeration systems | Total heat load + system optimization | Intermediate to advanced | Yes, within Intarcon’s portfolio | Free (for clients) | User-friendly interface; integrated with European regulations. |

| Parameters | HVACR WICF | KR LoadCalc | Intarcon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floor type | On-grade | On-grade | On-grade |

| Exterior temperature (°C) | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Indoor temperature (°C) | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| Insulation thermal conductivity [W/m °C] | 0.07 to 0.09 | 0.07 to 0.09 | 0.07 to 0.09 |

| Product weight (kg/24 h) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Internal load (W) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Operation time (h) | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Software/Method | HVACR WICF | KR LoadCalc | Intarcon | CFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat flux rate [W] | 26.0 | 11.0 | 22.6 | 34.3 |

| Percentage difference [%] | 24.5 | 102.9 | 41.1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lança, M.; Garcia, J.; Gomes, J. Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Refrigerated Spaces: A Comparative Study of Experiments, CFD Predictions and Heat Load Software Accuracy. Energies 2025, 18, 6280. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236280

Lança M, Garcia J, Gomes J. Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Refrigerated Spaces: A Comparative Study of Experiments, CFD Predictions and Heat Load Software Accuracy. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6280. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236280

Chicago/Turabian StyleLança, Miguel, João Garcia, and João Gomes. 2025. "Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Refrigerated Spaces: A Comparative Study of Experiments, CFD Predictions and Heat Load Software Accuracy" Energies 18, no. 23: 6280. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236280

APA StyleLança, M., Garcia, J., & Gomes, J. (2025). Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Refrigerated Spaces: A Comparative Study of Experiments, CFD Predictions and Heat Load Software Accuracy. Energies, 18(23), 6280. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236280