Effect of Subducting Baffle Structure in Solar Air Heaters: A CFD Insight into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Designing an SAH with subducting baffles fixed at a particular distance from the absorber plate.

- Conducting fluid flow and thermal analysis through a two-dimensional CFD simulation.

- Determining the Nusselt number and friction factor for evaluating the thermal and hydraulic performance and THP of the SAH.

- Recognizing optimal design parameters using a device efficiency study over different geometries.

- Producing correlations for Nu and f by considering all the parameters under investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

- Creating an SAH design with the help of AutoCAD 2019 software by merging subducting baffles.

- Determining the range of the design and operational parameters of the subducting baffle configuration.

- Numerical simulations were carried out for the developed model under different design and operational parameters in Ansys Fluent.

- The Reynolds number, Nusselt number, and friction factor were evaluated to determine the thermal and hydraulic performance and THP.

- Displaying and discussing the Nusselt number, friction factor, THP, and the enhancement of the thermal and friction characteristics of the SAH concerning design and operational parameters.

- Identifying the best parameters through detailed performance analysis.

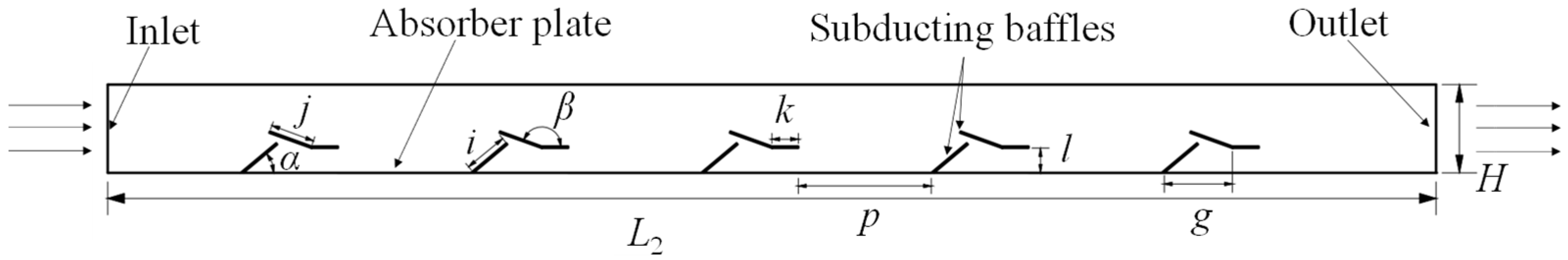

2.1. Geometry Design

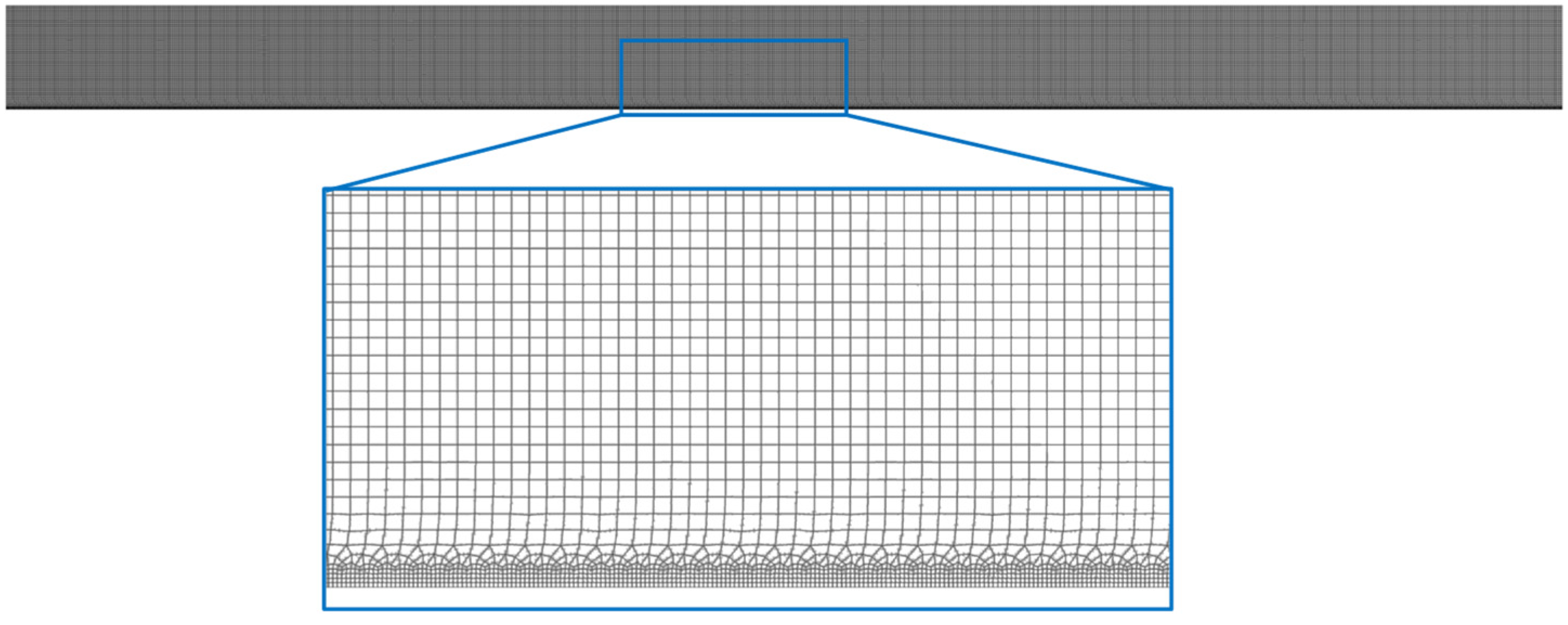

2.2. Grid Generation

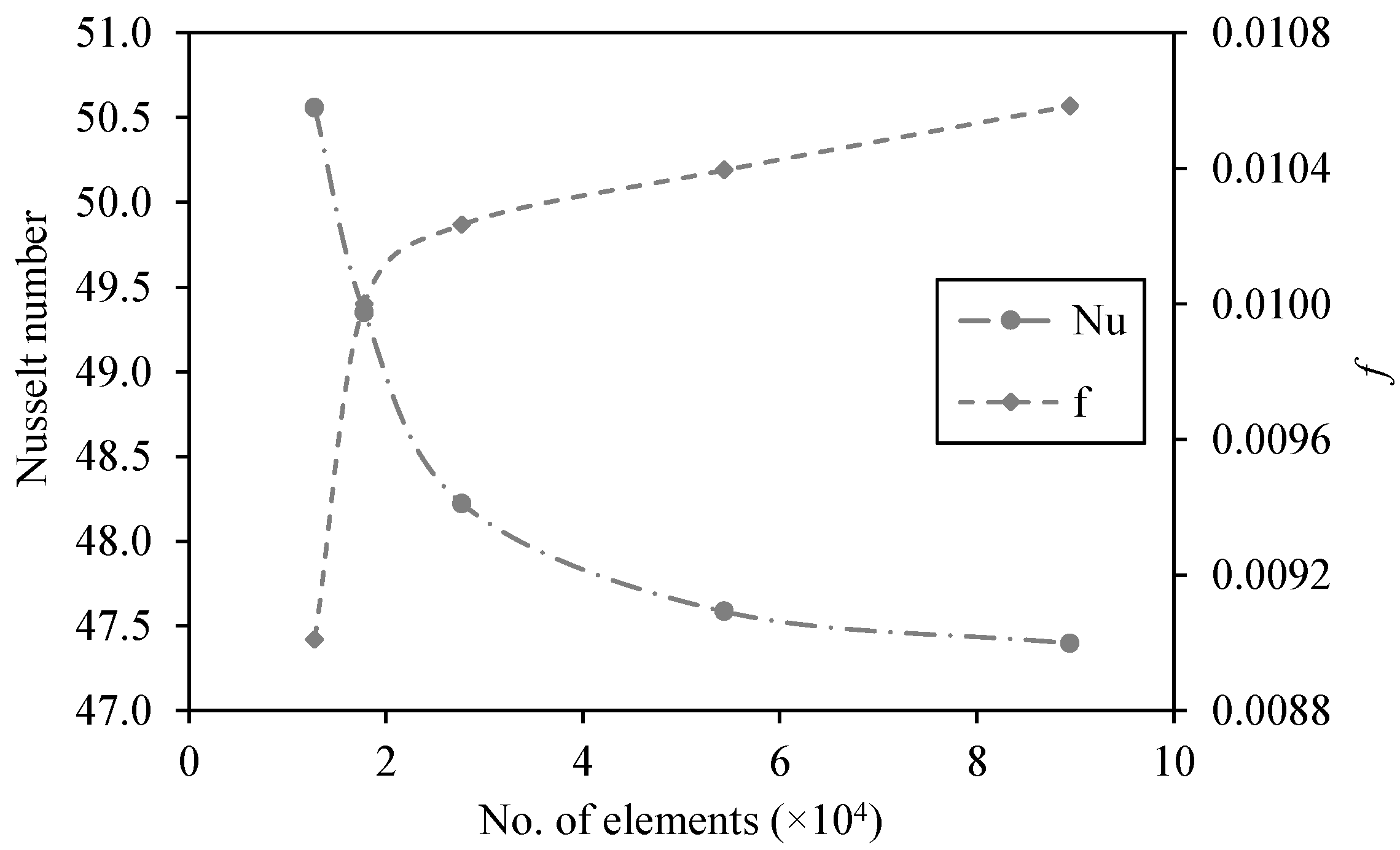

Grid Independence Test

2.3. Governing Equations

2.4. Boundary Conditions

2.5. Assumptions for CFD Analysis

- The present analysis uses a two-dimensional model; variations along the z-direction are neglected, as they are not critical for evaluating in-plane flow and heat transfer effects.

- The analysis utilizes a two-dimensional (2D) model, neglecting z-direction variations . This assumption is valid as out-of-plane effects are non-critical for evaluating the primary in-plane flow and heat transfer characteristics.

- A steady-state airflow is assumed to be maintained inside the duct. This simplifies the representation of airflow dynamics and focuses on a stabilized flow pattern.

- No change in the physical and chemical properties of both domains at the working temperature. This simplifies the calculation and upholds consistency in analysis by maintaining the same material property throughout the analysis.

- The side walls and the absorber plate are considered to be adiabatic. This reduced the convergence time by eliminating the external heat loss from the SAH and concentrating only on the internal heat transfer.

- Negligible radiation heat transfer in the duct. This excludes the radiation heat transfer, which is negligible when compared with other heat transfer modes in the duct and hence simplifies the calculation.

2.6. Solution Method and Turbulence Model

2.7. Post Processing of Results

2.8. Validation of CFD Results

3. Results and Discussion

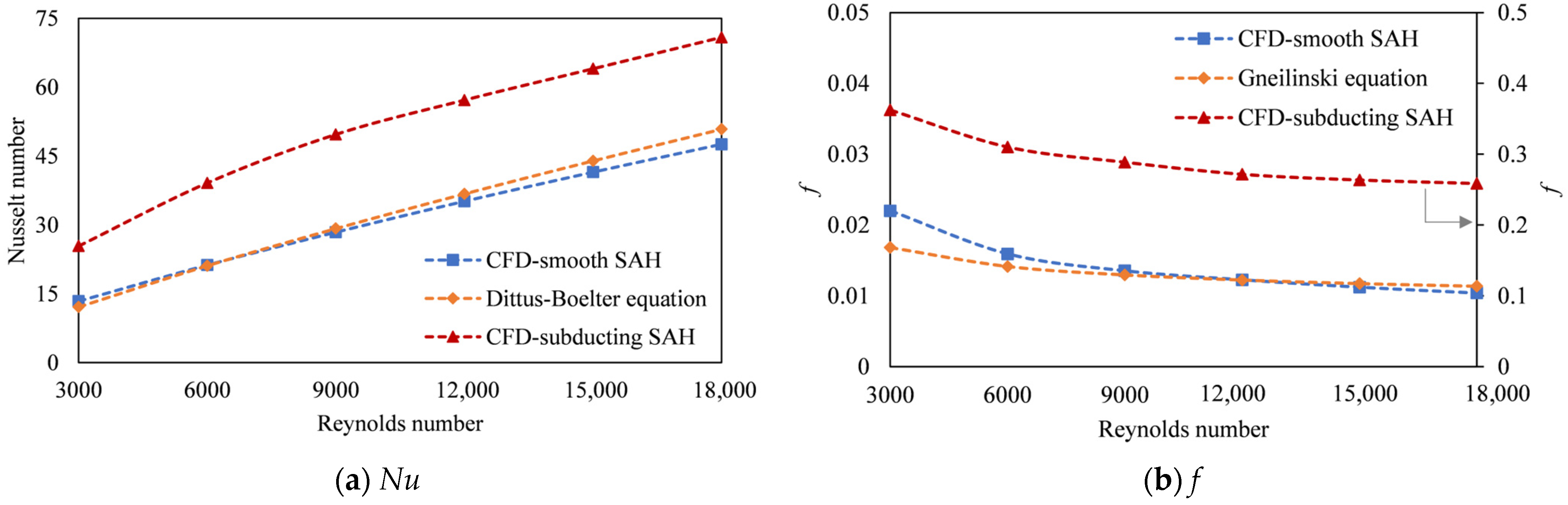

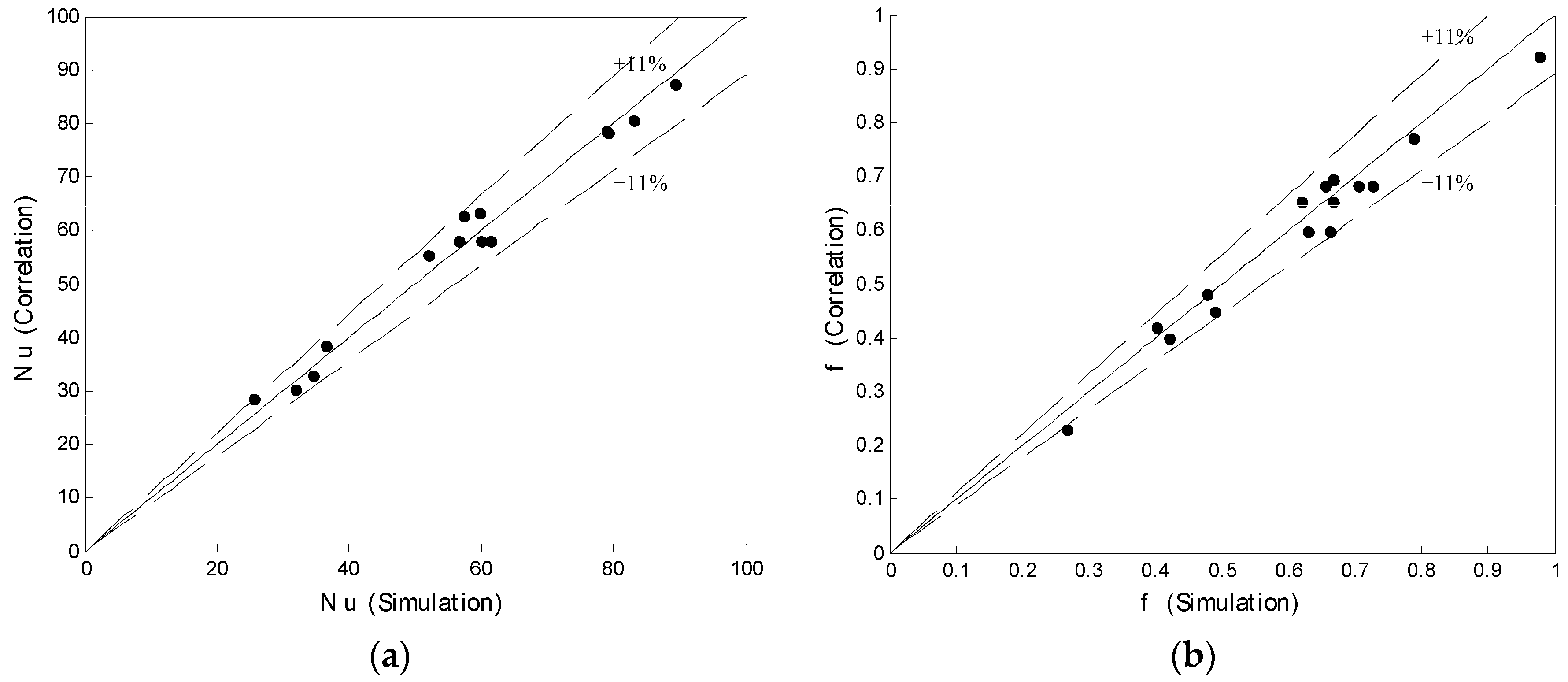

3.1. Validating the Computational Results

3.2. Effect of Pitch Angle (α)

3.2.1. Effect of α on Thermal Performance

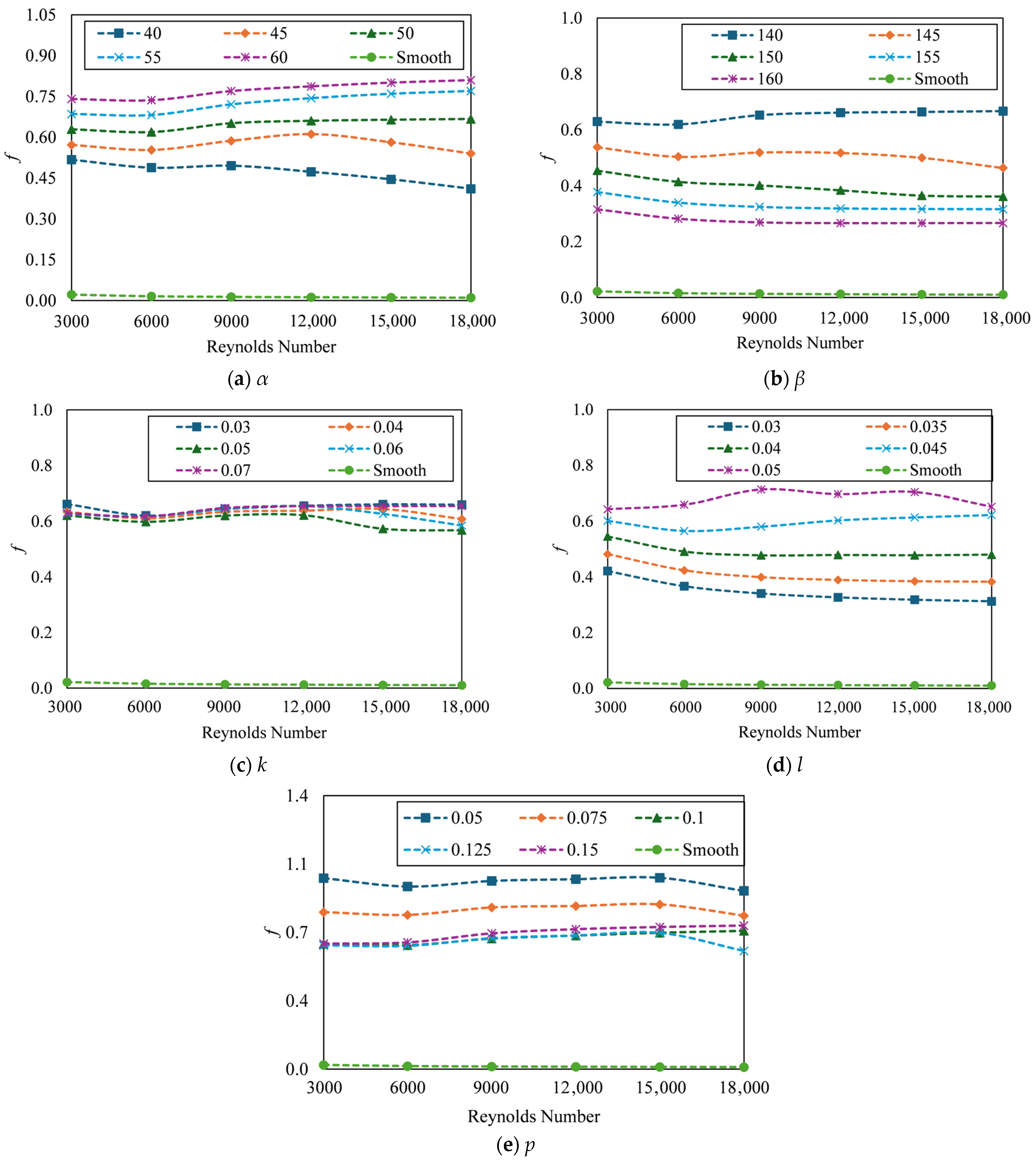

3.2.2. Effect of α on Hydraulic Performance

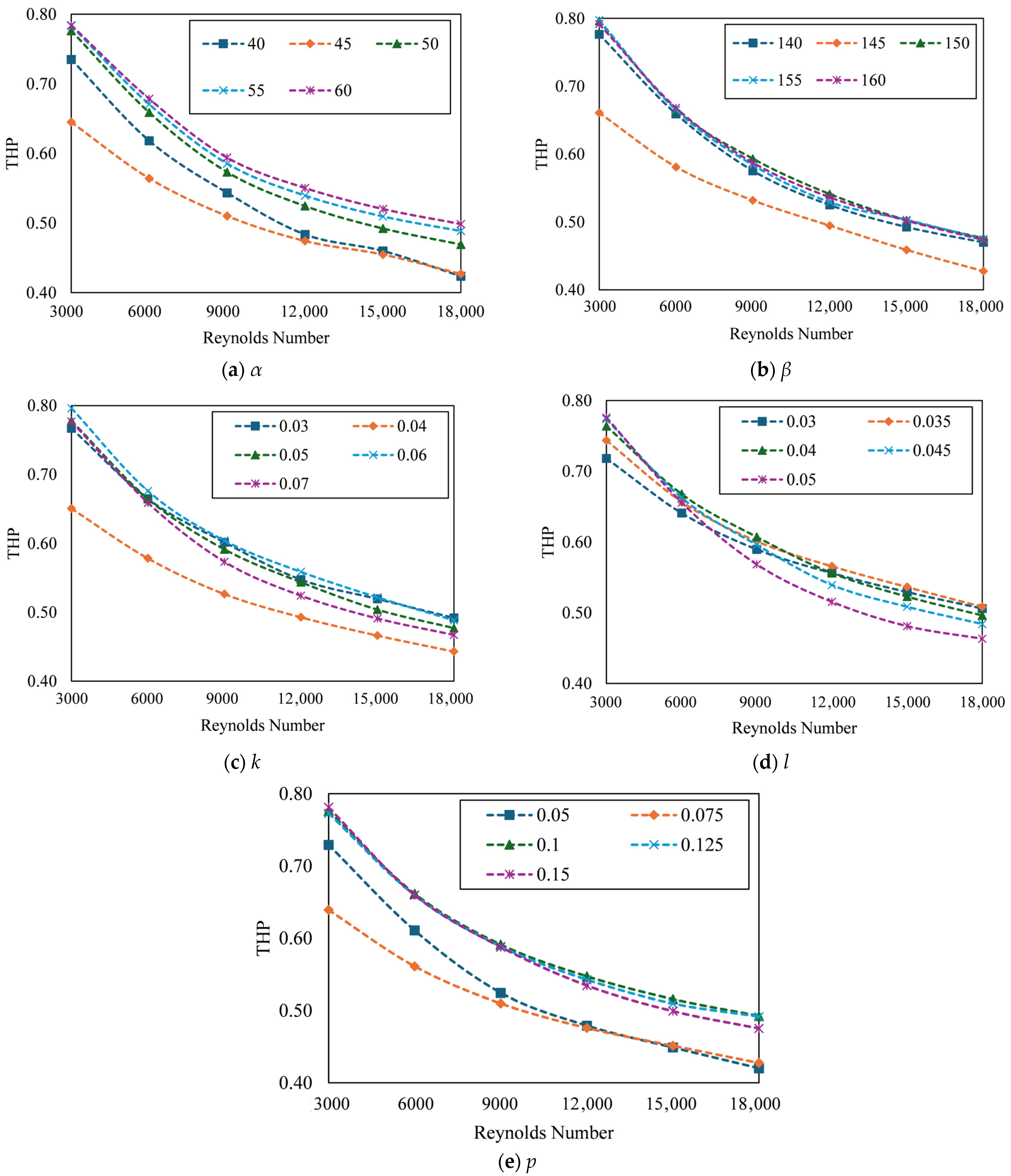

3.2.3. Effect of α on Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

3.3. Effect of Arm Angle (β)

3.3.1. Effect of β on Thermal Performance

3.3.2. Effect of β on Hydraulic Performance

3.3.3. Effect of β on Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

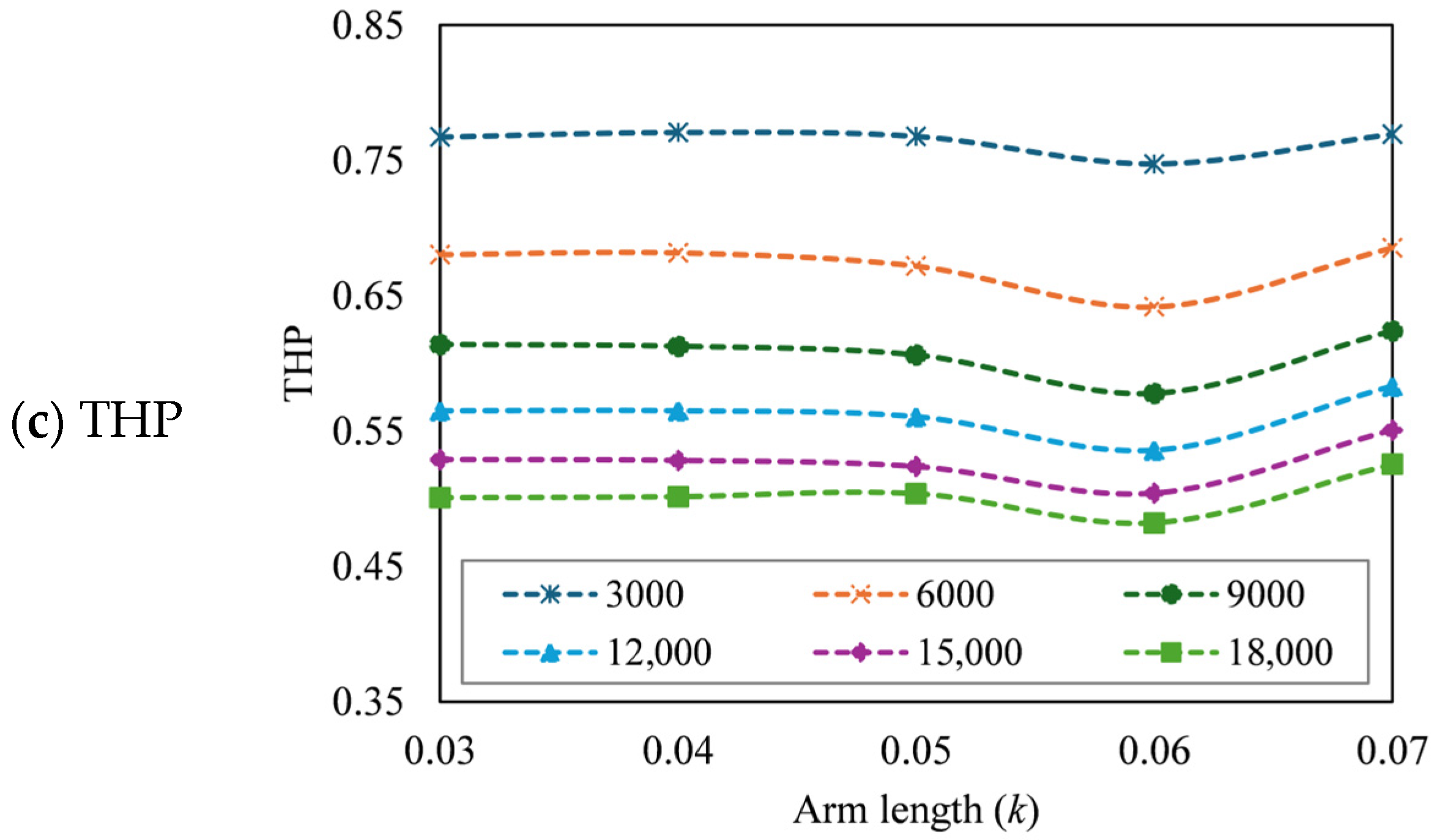

3.4. Effect of Arm Length (k)

3.4.1. Effect of k on Thermal Performance

3.4.2. Effect of k on Hydraulic Performance

3.4.3. Effect of k on Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

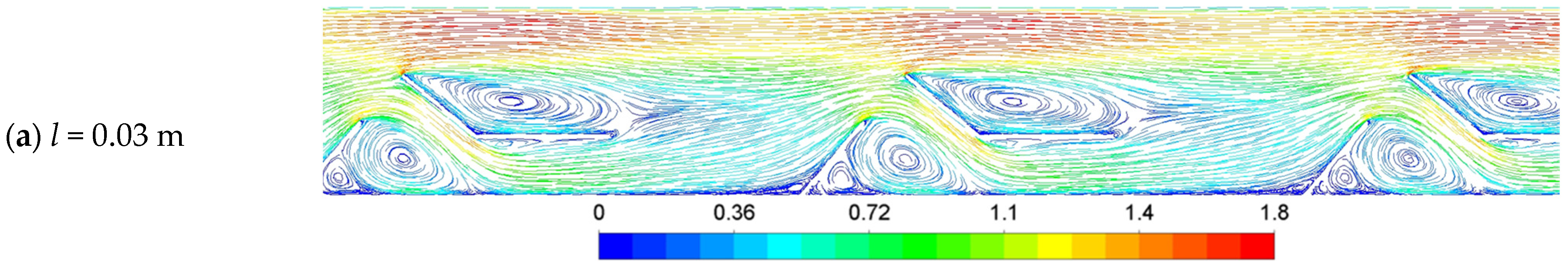

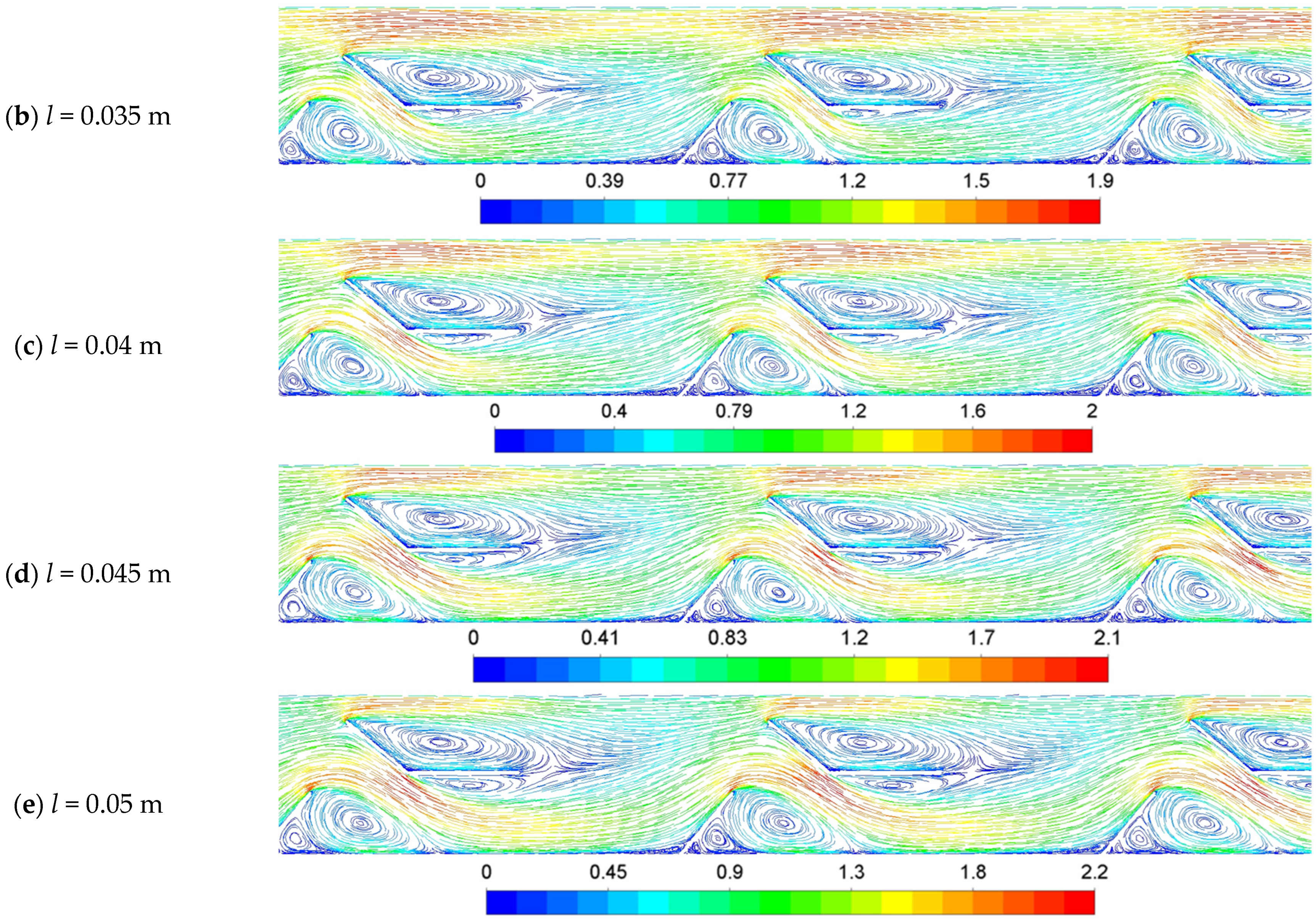

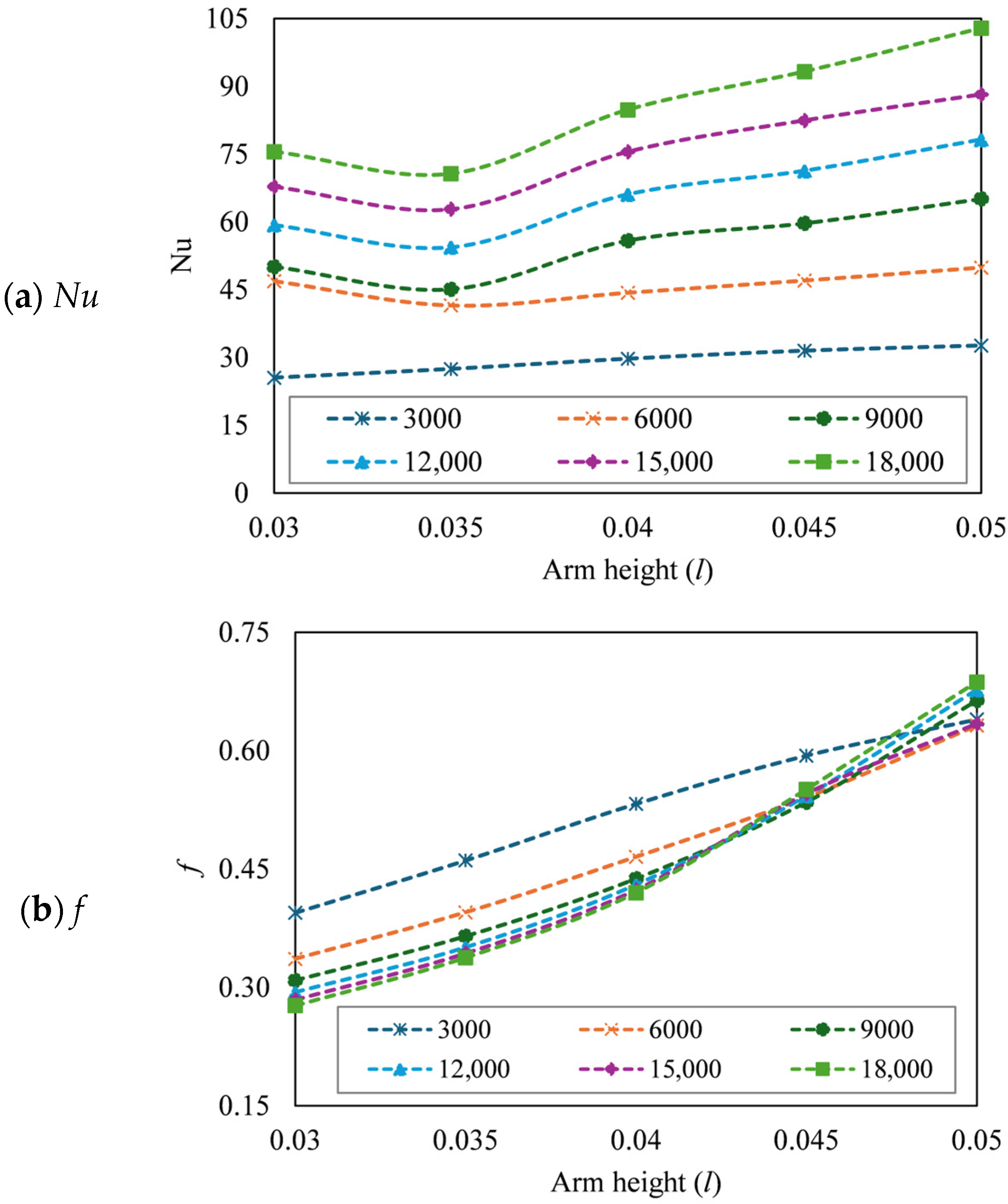

3.5. Effect of Arm Height (l)

3.5.1. Effect of l on Thermal Performance

3.5.2. Effect of l on Hydraulic Performance

3.5.3. Effect of l on Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

3.6. Effect of Pitch (p)

3.6.1. Effect of p on Thermal Performance

3.6.2. Effect of p on Hydraulic Performance

3.6.3. Effect of p on Thermo-Hydraulic Performance

3.7. Effect of Reynolds Number

3.7.1. Effect of Reynolds Number on Nu

3.7.2. Effect of Reynolds Number on f

3.7.3. Effect of Reynolds Number on THP

3.8. Development of Correlations

3.9. Comparison with Previous Studies

4. Conclusions

- The fluid flow characteristics of the SAH have changed due to the addition of a subducting baffle. Collectively, it contributed to improved heat transfer compared with the smooth absorber plate by promoting turbulence, disrupting the boundary layer, and facilitating control flow separation. This is clear because, in comparison to the smooth configuration, the Nu showed a 2.13-fold increase.

- The number of baffles in the SAH has decreased as a result of the increase in k and p. The Nu enhancement is not significantly affected by the increase in k, as it maintains the absorber area; however, it decreases the f. Nevertheless, the turbulence effect is diminished as a result of the reduction in the number of baffles due to the increase in p, which results in a reduction in Nu.

- The SAH has achieved the maximum Nu of 101.32 at k = 0.07 m, l = 0.05 m, p = 0.15 m, α = 60°, and β = 155° at Re = 18,000 while the maximum f was achieved at k = 0.07 m, l = 0.05 m, p = 0.05 m, α = 50°, and β = 155° at Re = 15,000. To consider the optimal conditions, the geometry of the SAH having a maximum THP of 0.798 at i = 0.05 m, j = 0.05 m, k = 0.07 m, l = 0.05 m, p = 0.15 m, α = 50°, and β = 155° at Re = 3000 is selected.

- When p (0.05 m) and R (3000) are at their lowest, the maximum thermal enhancement (Nu/Nus) of 2.58 is observed, while k and l are at their highest in the study range. Conversely, the friction enhancement (f/fs) of 87.76 is observed when the Re is at its maximum (18,000). The rate of increment in Nu/Nus is greater than that of f/fs. As a result of the greater increase in f/fs, the THP tends to decrease.

5. Future Research

- Reversal of airflow: In the current configuration, there is an additional option to operate with air in the reverse direction. This could also offer a substantial improvement in terms of thermal and pressure drop. Nevertheless, the thermal and flow characteristics must be identified by conducting a comprehensive analysis of the effect of geometry in the reverse direction.

- Experimental analysis: To investigate the geometry’s response to the changing natural environment, experimental analysis must be conducted with the optimal geometry of the current novel configuration. It is essential to validate the performance under real-world conditions in order to guarantee its reliability.

- Environmental and economic analysis: For economic and environmental reasons, the SAH must be analyzed to determine its impact on clean energy initiatives and sustainability, justifying investment and policy support.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature/Abbreviations

| Ac | absorber area, m2 | |

| C | constant | |

| D | hydraulic diameter, m | |

| F | friction factor | |

| f/fs | friction enhancement factor | |

| H | height of heater, m | |

| H | convective heat transfer, W/m2 K | |

| I | palm length, m | |

| J | forearm length, m | |

| K | arm length, m | |

| L | arm height, m | |

| L1 | length of entry section, m | |

| L2 | length of test section, m | |

| L3 | length of exit section, m | |

| mass flow rate, kg/s | ||

| Nu/Nus | heat transfer enhancement factor | |

| P | pitch, m | |

| P | pressure, N/m2 | |

| Pr | Prandtl number | |

| qw | heat flux, W/m2 | |

| T | temperature, K | |

| turbulence Intensity | ||

| RMS of velocity fluctuations, m/s | ||

| U | mean flow velocity, m/s | |

| v | air velocity, m/s | |

| W | width of heater, m | |

| Abbreviations | ||

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics | |

| Nu | Nusselt number | |

| Re | Reynolds number | |

| RNG | Renormalization group model | |

| SAH | Solar air heater | |

| SSAH | Smooth solar air heater | |

| THP | Thermo-hydraulic performance | |

| Subscript | ||

| out | outlet | |

| in | inlet | |

| p | plate | |

| m | mean | |

| s | smooth | |

| Greek letters | ||

| α | pitch angle, deg | |

| β | arm angle, deg | |

| ρ | air density, kg/m3 | |

| µ | dynamic viscosity, Nm2 | |

References

- Gupta, M.K.; Kaushik, S.C. Performance Evaluation of Solar Air Heater for Various Artificial Roughness Geometries Based on Energy, Effective and Exergy Efficiencies. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharwal, K.R.; Pawar, C.B.; Chaube, A. Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow Analysis of Artificially Roughened Ducts Having Rib and Groove Roughness. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 50, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J.S.; Datta, A.; Mondal, S. Numerical Analysis of a Solar Air Heater with Offset Transverse Ribs Placed near the Absorber Plate. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.S.; Bhagoria, J.L. A Numerical Investigation of Square Sectioned Transverse Rib Roughened Solar Air Heater. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 79, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saini, R.P. CFD Based Performance Analysis of a Solar Air Heater Duct Provided with Artificial Roughness. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpenko, M.; Stosiak, M.; Šukevičius, Š.; Skačkauskas, P.; Urbanowicz, K.; Deptuła, A. Hydrodynamic Processes in Angular Fitting Connections of a Transport Machine’s Hydraulic Drive. Machines 2023, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.S.; Bhagoria, J.L. A CFD Based Thermo-Hydraulic Performance Analysis of an Artificially Roughened Solar Air Heater Having Equilateral Triangular Sectioned Rib Roughness on the Absorber Plate. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2014, 70, 1016–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, A.; Varshney, L.; Verma, P. Effect of Roughness Parameters on Performance of Solar Air Heater Having Artificial Wavy Roughness Using CFD. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, I.; Barhdadi, F.-Z.; Amghar, K.; Daoudi, S.; Yahiaoui, R.; Ghoumid, K. Enhancing Performance in Solar Air Channels: A Numerical Analysis of Turbulent Flow and Heat Transfer with Novel Shaped Baffles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 251, 123561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Das, R.K.; Kulkarni, K. Computational and Experimental Assessment of Solar Air Heater Roughened with Six Different Baffles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 27, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, H.; Saffar-Avval, M.; Hajmohammadi, M.R. 3D Simulation and Parametric Optimization of a Solar Air Heater with a Novel Staggered Cuboid Baffles. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 205, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faujdar, S.; Agrawal, M. Computational Fluid Dynamics Based Numerical Study to Determine the Performance of Triangular Solar Air Heater Duct Having Perforated Baffles in V-down Pattern Mounted underneath Absorber Plate. Sol. Energy 2021, 228, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Akshayveer; Singh, A.P.; Singh, O.P. Investigations for Efficient Design of a New Counter Flow Double-Pass Curved Solar Air Heater. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompookham, T.; Eiamsa–ard, S.; Buanak, K.; Promvonge, P.; Maruyama, N.; Hirota, M.; Skullong, S.; Promthaisong, P. Thermal Performance Augmentation in a Solar Air Heater with Twisted Multiple V–Baffles. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 205, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedau, A.; Singal, S.K. Development of Nusselt Number and Friction Factor Correlations for Double-Pass Solar Air Heater Duct. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 234, 121227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menasria, F.; Zedairia, M.; Moummi, A. Numerical Study of Thermohydraulic Performance of Solar Air Heater Duct Equipped with Novel Continuous Rectangular Baffles with High Aspect Ratio. Energy 2017, 133, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, S.R.; Bhosale, A.C. Honeycomb-Shaped Artificial Roughness in Solar Air Heaters: CFD-Experimental Insights into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE 93-2003; Methods of Testing to Determine the Thermal Performance of Solar Collectors. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010.

- Hamad, R.F.; Alshukri, M.J.; Eidan, A.A.; Alsabery, A.I. Numerical Investigation of Heat Transfer Augmentation of Solar Air Heater with Attached and Detached Trapezoidal Ribs. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J.S.; Datta, A.; Mondal, S. Flow and Thermal Behavior of Solar Air Heater with Grooved Roughness. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Sharma, V.; Sanyal, D.; Das, P. A Conjugate Heat Transfer Analysis of Performance for Rectangular Microchannel with Trapezoidal Cavities and Ribs. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 138, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.-H.; Moon, K.-A.; Kim, S.-B.; Choi, H.-U. Analysis of Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow in a Solar Air Heater with Sequentially Placed Rectangular Obstacles on the Fin Surface. Energies 2025, 18, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqsair, U.F. Numerical Simulation and Optimization of a Chevron-Type Corrugated Solar Air Heater. Energies 2025, 18, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Goel, V.; Kumar, A. Investigation of Heat Transfer Augmentation and Friction Factor in Triangular Duct Solar Air Heater Due to Forward Facing Chamfered Rectangular Ribs: A CFD Based Analysis. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgakis, G.C.; Assanis, D.N. Comparison of linear and nonlinear RNG k-epsilon models for incompressible turbulent flows. Numer. Heat. Transf. Part B Fundam. 1999, 35, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsly, B.W.; Santhappan, J.S.; Chockalingam, M.P. Impact of Corrugated Duct and Heat Storage Element on the Performance of a Low-Cost Solar Air Heater under Forced Air Circulation: An Experimental Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 23866–23884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-U.; Choi, K.-H. CFD Analysis on the Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow of Solar Air Heater Having Transverse Triangular Block at the Bottom of Air Duct. Energies 2020, 13, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghana, B.; Tariku, F.; Bitsuamlak, G. Numerical Study of the Impact of Transverse Ribs on the Energy Potential of Air-Based BIPV/T Envelope Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.; Maithani, R.; Sharma, S. Investigation of Heat Transfer and Friction Characteristics of Solar Air Heater through an Array of Submerged Impinging Jets. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kim, M.-H. CFD Analysis on the Thermal Hydraulic Performance of an SAH Duct with Multi V-Shape Roughened Ribs. Energies 2016, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Bhagoria, J.L.; Narayanan, R. Experimental Analysis of Thermo-Hydraulic Performance of Quadratic Duct with Artificial Roughness on a Single Broad Heated Surface of the Absorber Plate of Solar Air Heater. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 72, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureini, S.G.; Azadani, L.N. Thermal Performance Enhancement of a Solar Air Heater with Different Roughness Layouts. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, J.S.; Maithani, R.; Chamoli, S. Experimental Investigation of Heat Transfer and Friction Factor Characteristics of Solar Air Heater Using Wavy Delta Winglets. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 117, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Hang, W.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A Novel In-Situ Sensor Calibration Method for Building Thermal Systems Based on Virtual Samples and Autoencoder. Energy 2024, 297, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Shi, L.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Yang, P.; Xiao, H.; Chen, D.; Zhao, P.; Shen, X. Virtual Sample Diffusion Generation Method Guided by Large Language Model-Generated Knowledge for Enhancing Information Completeness and Zero-Shot Fault Diagnosis in Building Thermal Systems. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2025, 26, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamoli, S.; Thakur, N.S. Heat Transfer Enhancement in Solar Air Heater with V-Shaped Perforated Baffles. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2013, 5, 023122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneissi, M.; Habchi, C.; Russeil, S.; Lemenand, T.; Bougeard, D. Heat Transfer Enhancement of Inclined Projected Winglet Pair Vortex Generators with Protrusions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 134, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Prajapati, D.R.; Samir, S. Heat Transfer and Friction Factor Correlations Development for Solar Air Heater Duct Artificially Roughened with ‘S’ Shape Ribs. Exp. Therm. Fluid. Sci. 2017, 82, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaci, C.-E.; Moummi, A.; Sanchez de la Flor, F.J.; Rodriguez Jara, E.A.; Rincon-Casado, A.; Ruiz-Pardo, A. Numerical and Experimental Study of the Heat Transfer and Hydraulic Performance of Solar Air Heaters with Different Baffle Positions. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundappa, M. Optimum Thermo-Hydraulic Performance of Solar Air Heater Provided with Cubical Roughness on the Absorber Surface. Exp. Heat. Transf. 2020, 33, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperski, J.; Nemś, M. Investigation of Thermo-Hydraulic Performance of Concentrated Solar Air-Heater with Internal Multiple-Fin Array. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 58, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Alsibiani, S. Employment of Roughened Absorber Palate and Jet Nozzles with Different Hole Shapes for Performance Boost of Solar-Air-Heaters. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 17, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Parameters | Range | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Pitch angle (α) | 40–60 | 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 | Degree |

| 2. | Arm angle (β) | 140–160 | 140, 145, 150, 155, 160 | Degree |

| 3. | Arm length (k) | 0.03–0.07 | 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, 0.07 | m |

| 4. | Arm height (l) | 0.03–0.05 | 0.03, 0.035, 0.04, 0.045, 0.05 | m |

| 5. | Pitch (p) | 0.05–0.15 | 0.05, 0.075, 0.10, 0.125, 0.15 | m |

| 6. | Reynolds number (Re) | 3000–18,000 | 3000, 6000, 9000, 12,000, 15,000, 18,000 | - |

| No. of Elements | Nu | % Deviation | f | % Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12,750 | 50.55797 | 2.450662 | 0.0090094 | 9.906361 |

| 17,814 | 49.3486 | 2.338449 | 0.0100000 | 2.28379 |

| 27,750 | 48.22098 | 1.336599 | 0.0102337 | 1.548408 |

| 54,375 | 47.58496 | 0.397594 | 0.0103947 | 1.790481 |

| 89,498 | 47.39651 | - | 0.0105842 | - |

| Researcher | Geometry of Roughness | Nu/Nus | f/fs | THP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bensasi et al. [39] | Rectangular baffle | - | - | 0.53–0.75 |

| Madhukeshwara Nanjundappa [40] | Cubical roughness | - | - | 0.67 |

| Jacek and Magdalena [41] | Multiple-fin array | - | - | 0.411 |

| Sameer Ali Alsibiani [42] | Rectangular pattern | 2.5–4.8 | 20–160 | 0.48–1.62 |

| Raisan et al. [18] | Trapezoidal ribs | 1.1–2.1 | 14.3–17.5 | 0.49–0.85 |

| Menasria et al. [35] | Rectangular baffle | 1.62–3.72 | 14–634 | 0.30–0.85 |

| Prasad et al. [3] | Transverse ribs | 1.15–1.55 | 1.4–7.67 | 0.72–1.04 |

| Present study | Subducting baffle | 1.36–2.58 | 14.33–87.76 | 0.42–0.798 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winsly, B.W.; Benjamin, P.A.; Chockalingam, M.P.; Santhappan, J.S.; Prabakaran, R.; Kim, S.C. Effect of Subducting Baffle Structure in Solar Air Heaters: A CFD Insight into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance. Energies 2025, 18, 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236223

Winsly BW, Benjamin PA, Chockalingam MP, Santhappan JS, Prabakaran R, Kim SC. Effect of Subducting Baffle Structure in Solar Air Heaters: A CFD Insight into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236223

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinsly, Beno Wincy, Prince Abraham Benjamin, Murugan Paradesi Chockalingam, Joseph Sekhar Santhappan, Rajendran Prabakaran, and Sung Chul Kim. 2025. "Effect of Subducting Baffle Structure in Solar Air Heaters: A CFD Insight into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance" Energies 18, no. 23: 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236223

APA StyleWinsly, B. W., Benjamin, P. A., Chockalingam, M. P., Santhappan, J. S., Prabakaran, R., & Kim, S. C. (2025). Effect of Subducting Baffle Structure in Solar Air Heaters: A CFD Insight into Thermo-Hydraulic Performance. Energies, 18(23), 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236223