4.1. The Dutch Policy Instrument Mix Supporting CEIs Across Governance Levels

To address the first research question, “What is the Dutch policy instrument mix that supports CEIs at different governance levels?,” this study examines the policy instrument mix that supports CEIs across national, regional, and municipal governance levels. The Dutch policy landscape for CEIs is shaped by each of these levels, with each contributing to the broader energy transition objectives.

At the national level, the DCA serves as a cornerstone policy instrument supporting CEIs. The DCA not only sets clear climate goals but also bridges national objectives with regional and municipal efforts, allowing flexibility for lower-level alignment. The DCA emerged from collaborative efforts involving over 100 stakeholders and functions as a principal planning instrument to guide national climate action and the sustainable energy transition [

66]. In doing so, the DCA tries to ensure that national objectives are flexible enough to align with local and regional realities while maintaining coherence across governance levels.

Table 2 outlines the key goals and ambitions of the DCA, highlighting commitments to emission reduction, renewable energy targets, and community ownership.

The DCA implementation process includes periodic evaluations and revisions to renewable energy goals. For instance, the 2021 coalition agreement revised the overall renewable energy target upwards to 120 TWh [

2]. This process operates within a five-year planning and review cycle, ensuring that the DCA remains aligns with both national and international climate commitments.

Table 3 outlines the key governance responsibilities within the DCA framework, detailing the roles of various stakeholders in ensuring their successful implementation.

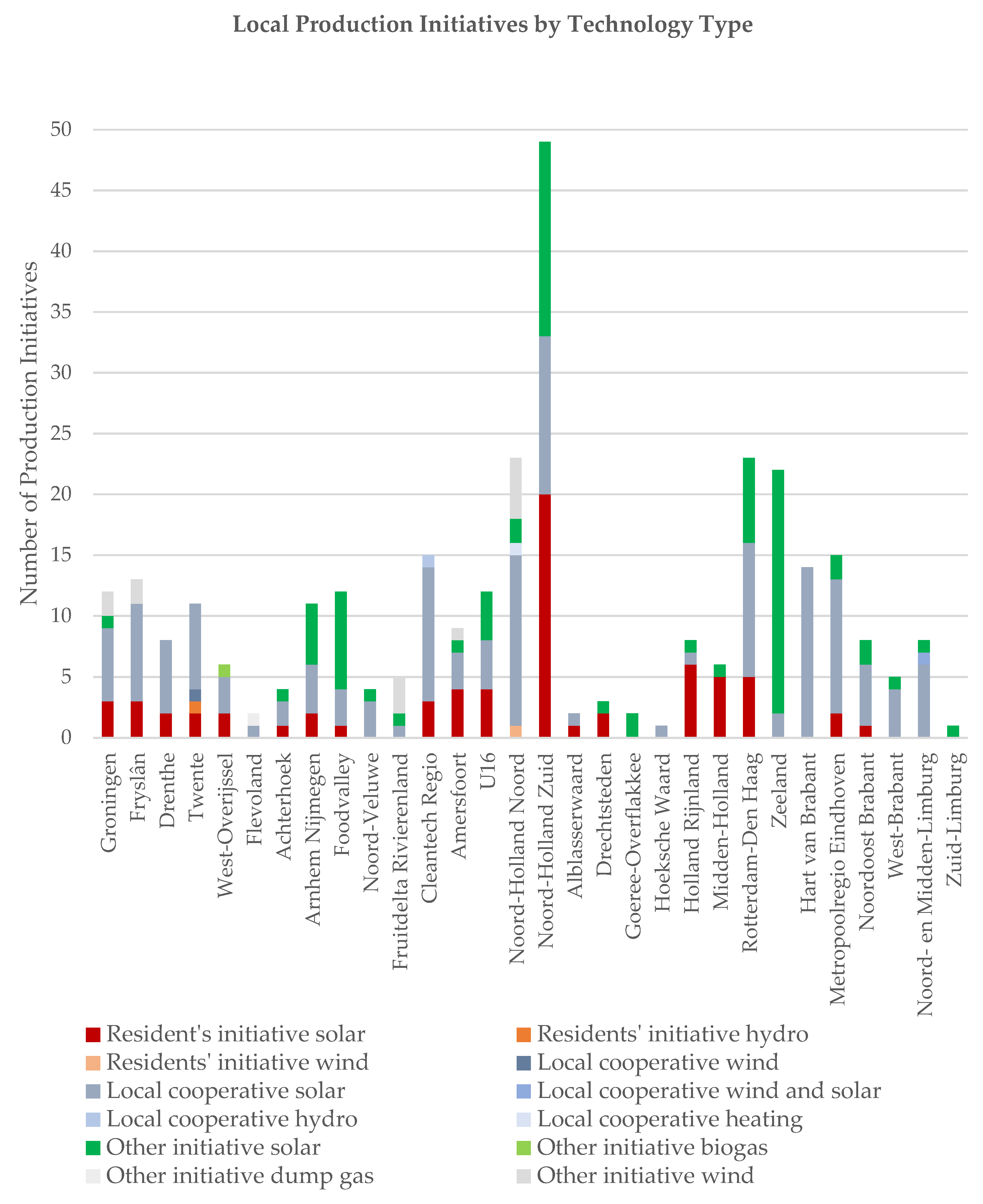

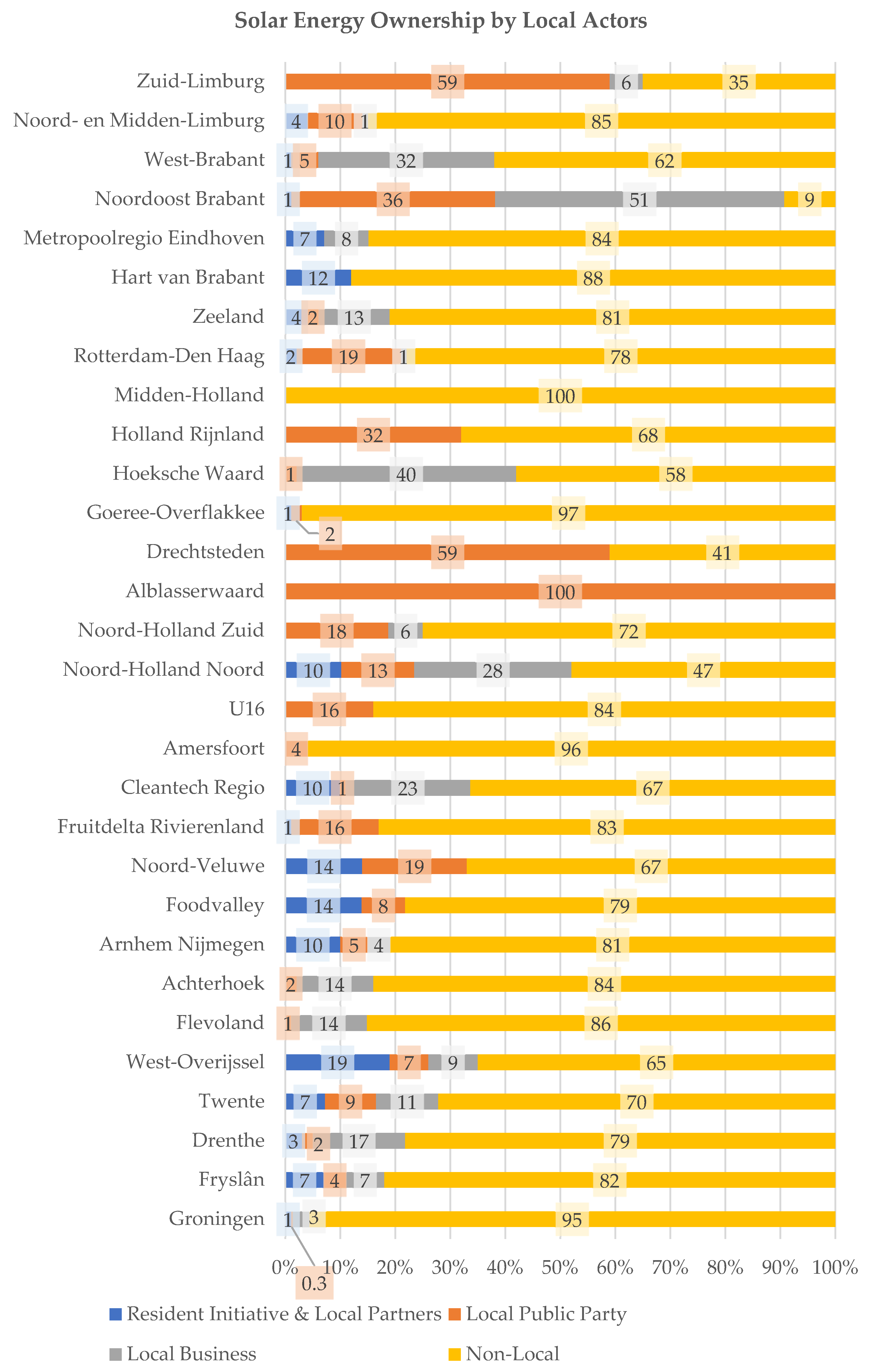

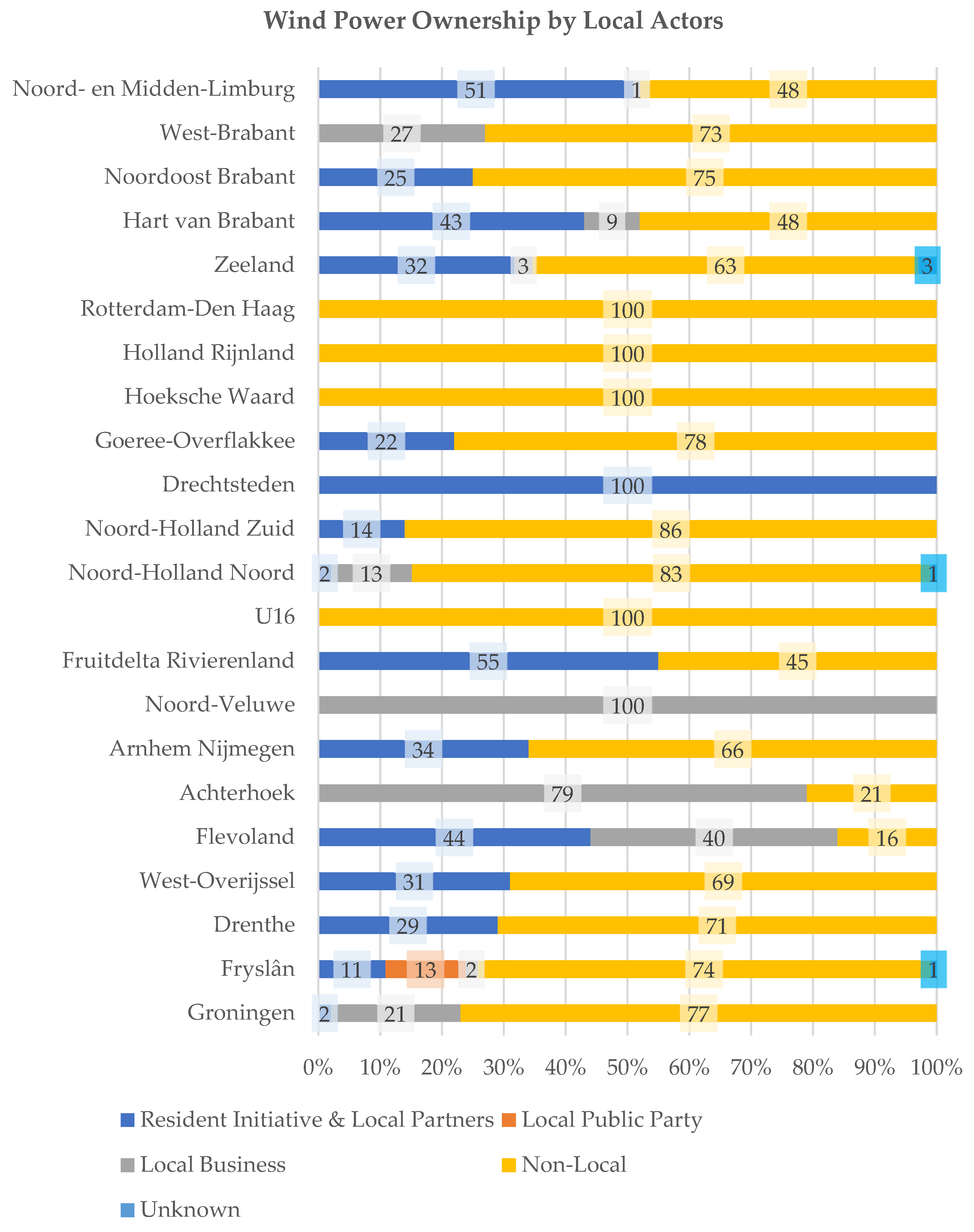

A significant policy mechanism within the DCA is the ambition for 50 percent local ownership of energy projects, driven by advocacy from national umbrella organizations like Energie Samen (s national umbrella organization for energy cooperatives in the Netherlands) to enhance the social acceptance of renewable energy, particularly land-based wind turbines. These negotiations highlighted the feasibility of community ownership, stressing adaptability and clarity in interpreting the 50 percent local ownership ambition [

64]. the Netherlands’ ambition on local ownership is notably ambitious but is not a legal requirement at the national level. While the national government holds legal authority to mandate this target, existing spatial planning laws allow municipalities to determine how local ownership is integrated into policies [

64]. This has led to ongoing debates regarding the potential legal enforcement of local ownership, particularly considering rising energy security concerns.

By comparison, Denmark’s Renewable Energy Act requires at least 20 percent community ownership for new wind projects and has been fairly successful in achieving its targeted level of local ownership [

67]. However, the conceptual model of the multi-tier implementation of a community-centric energy production as used in the Netherlands can support the better alignment of policy instruments that trickle down from national to regional and regional to local governments. The Dutch model for achieving local ownership aims to balance national targets and local realities. Nevertheless, despite its extensive framework, the DCA faces multiple implementation challenges (see

Table 4). In summary, these challenges illustrate that even with an overarching plan like the DCA, on-the-ground issues such as grid congestion, policy fragmentation, and financial constraints can impede progress. These issues underscore the need for stronger coordination across all levels of governance to resolve them and ensure that the policy instruments support CEIs across governance levels.

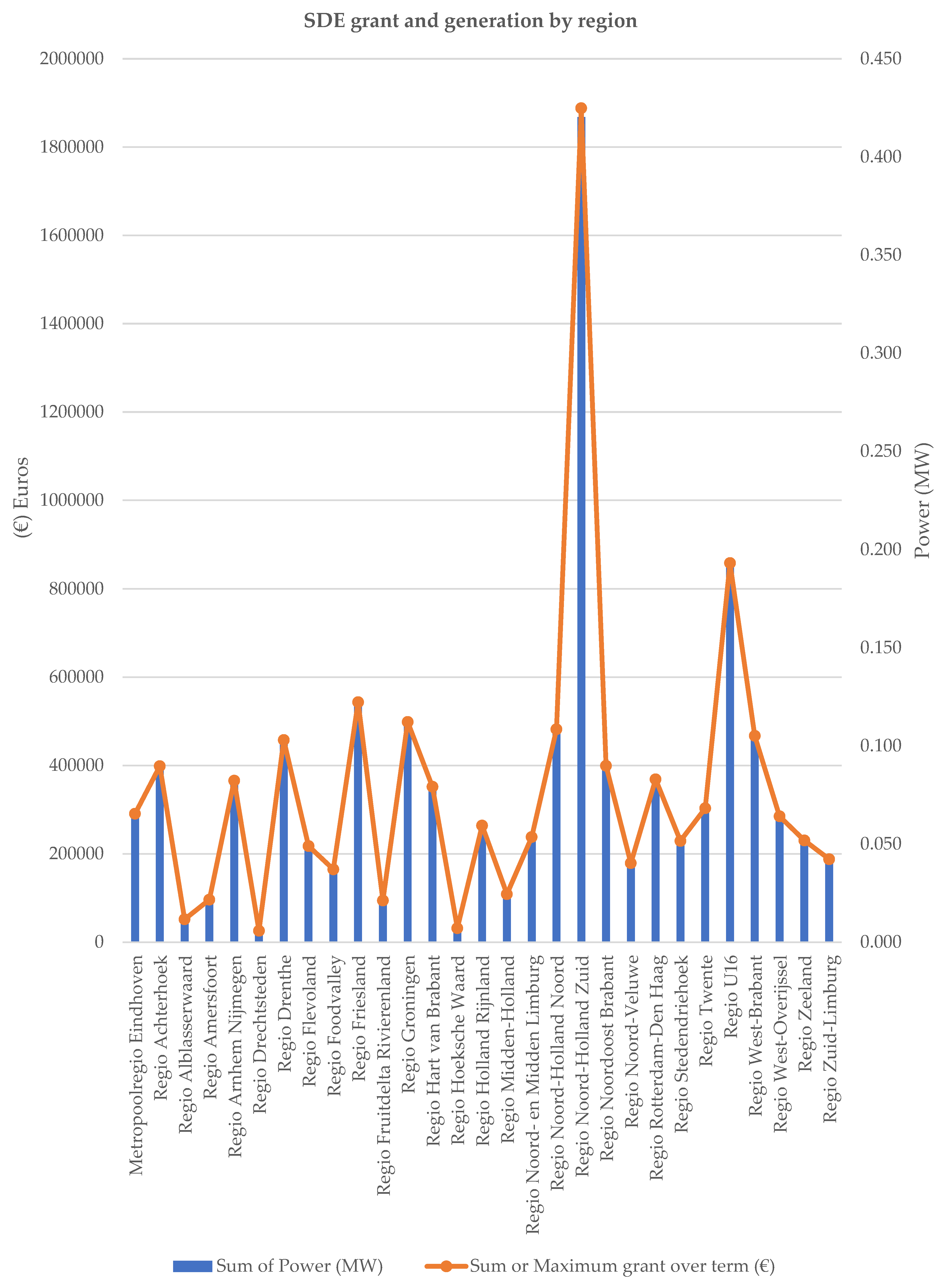

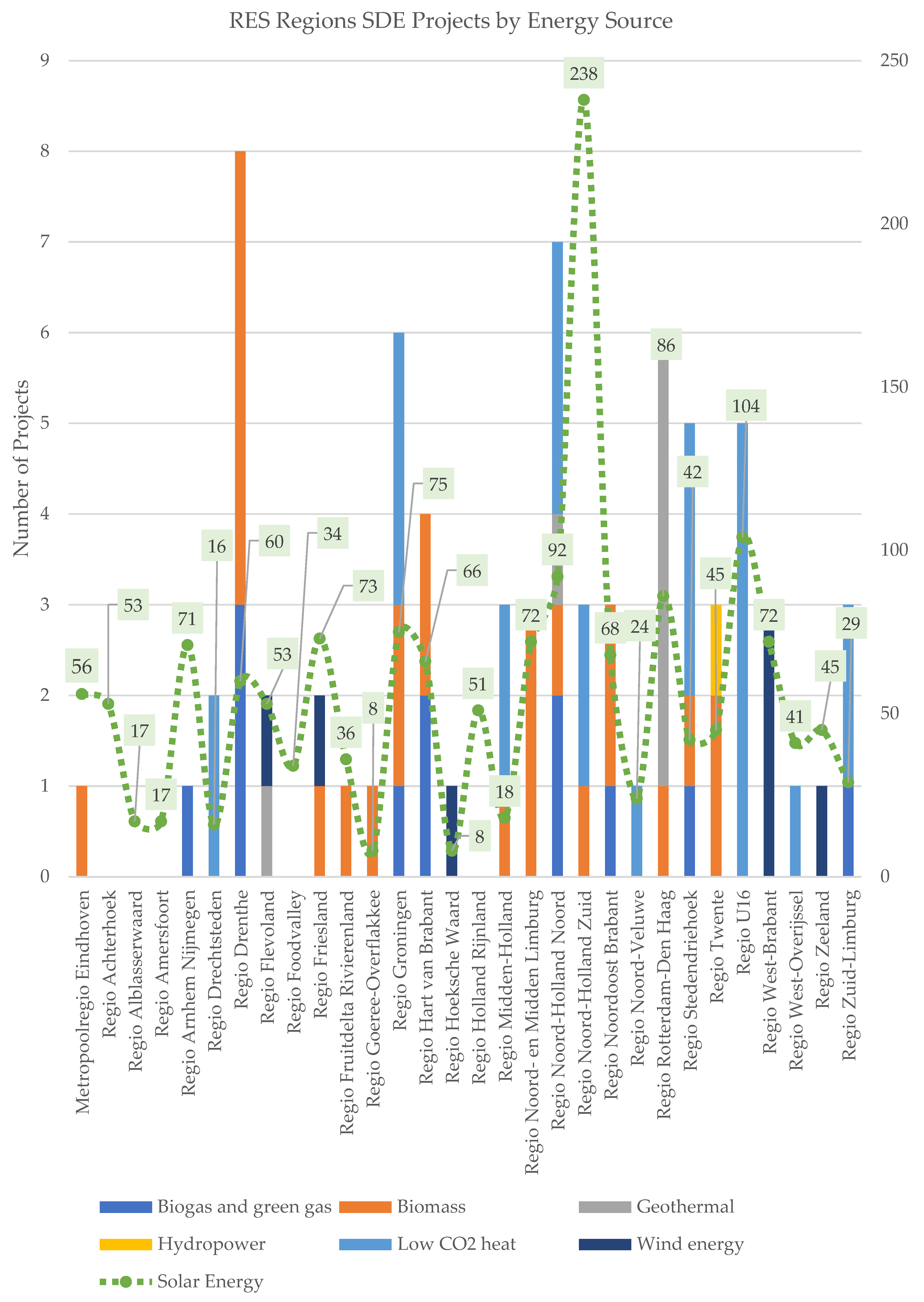

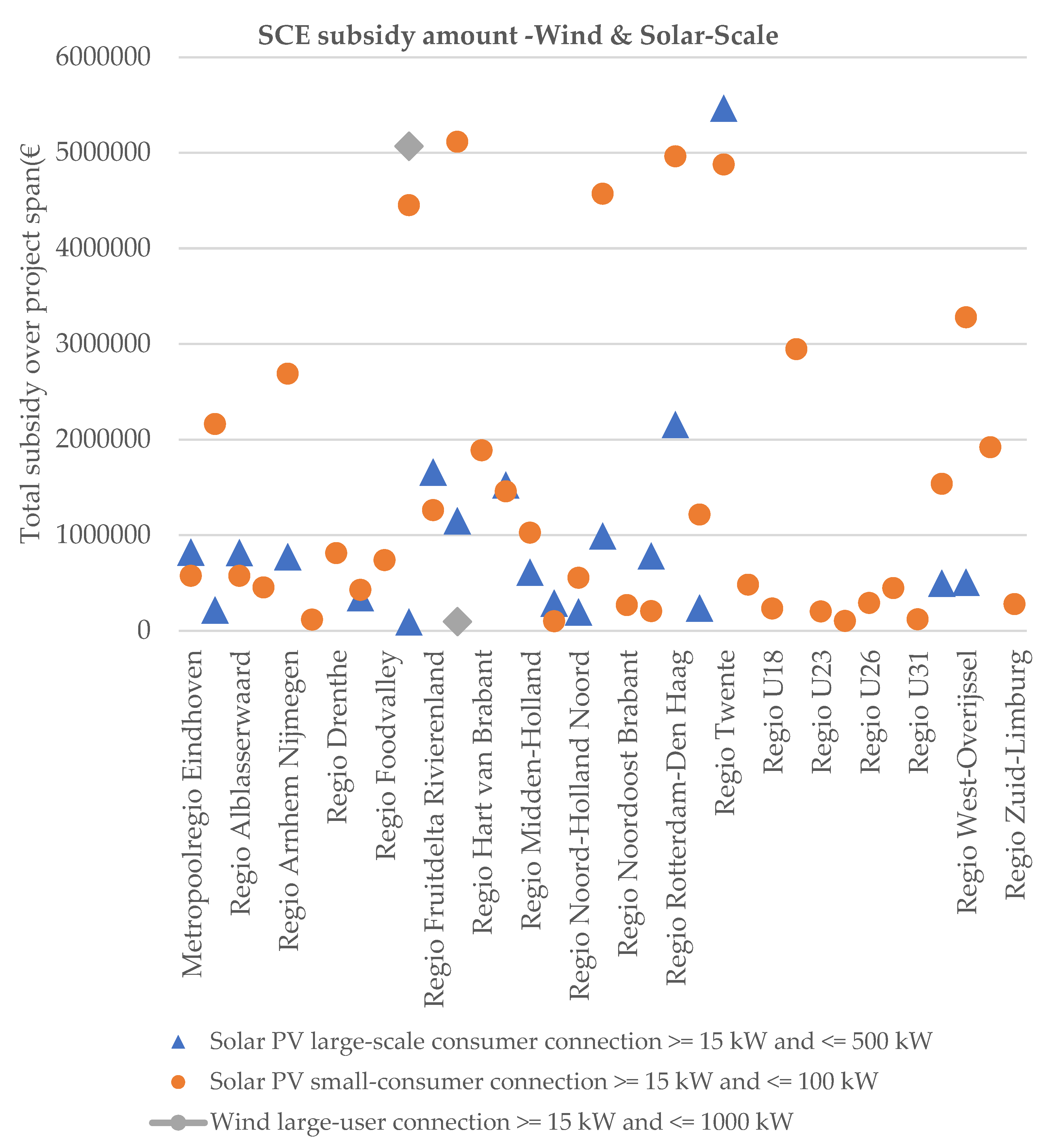

Several national subsidies play a vital role as economic instruments that stimulate renewable energy generation and local ownership.

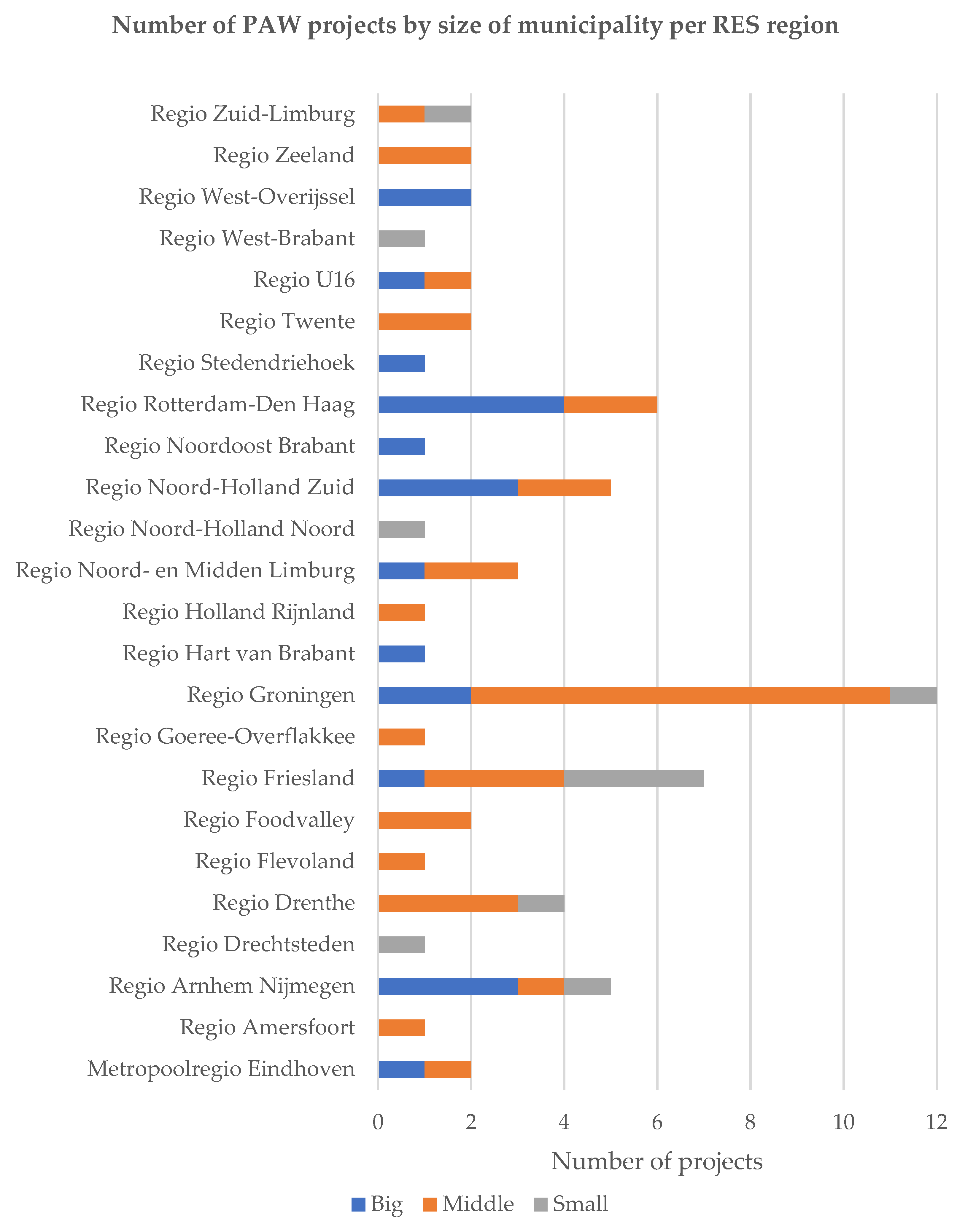

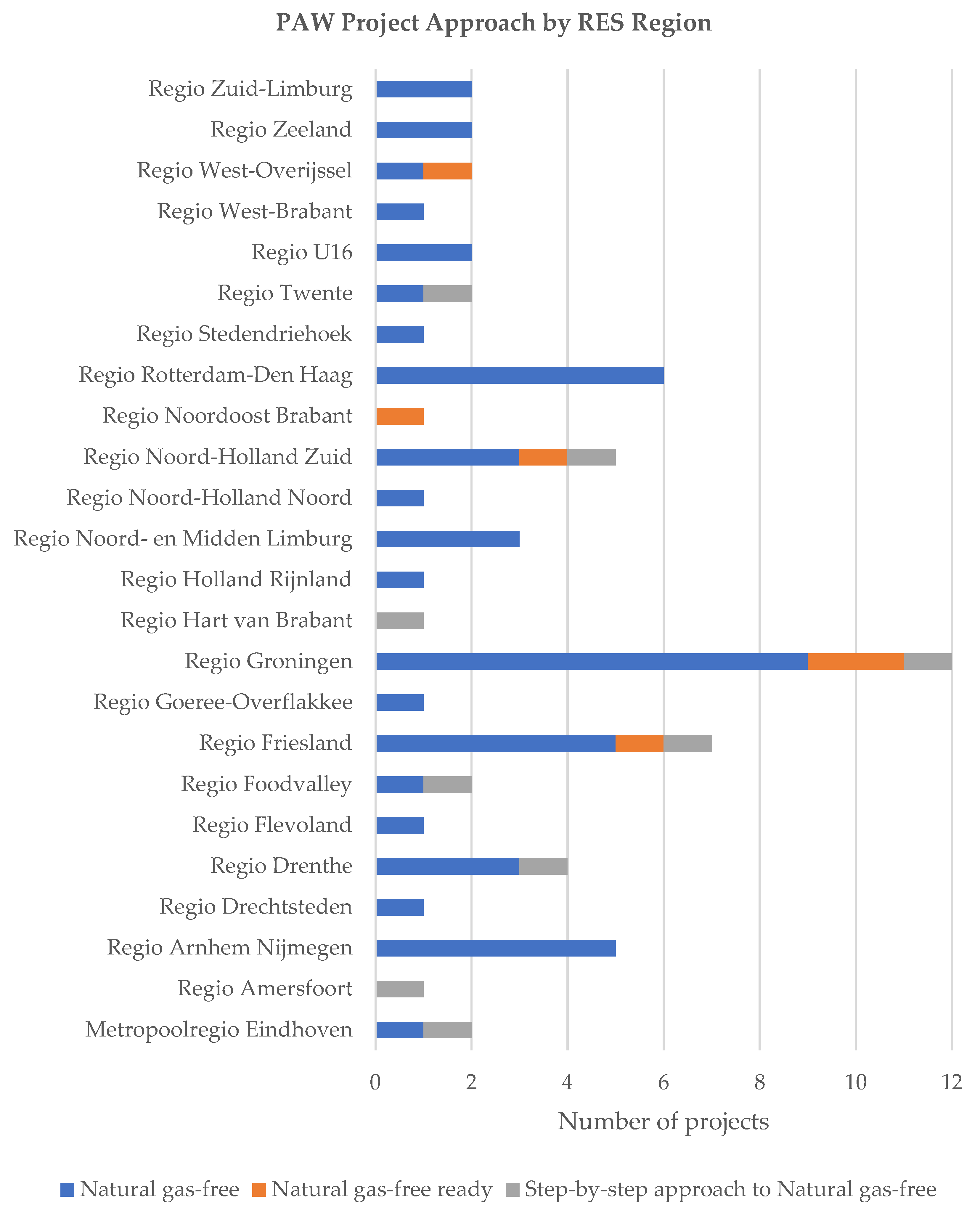

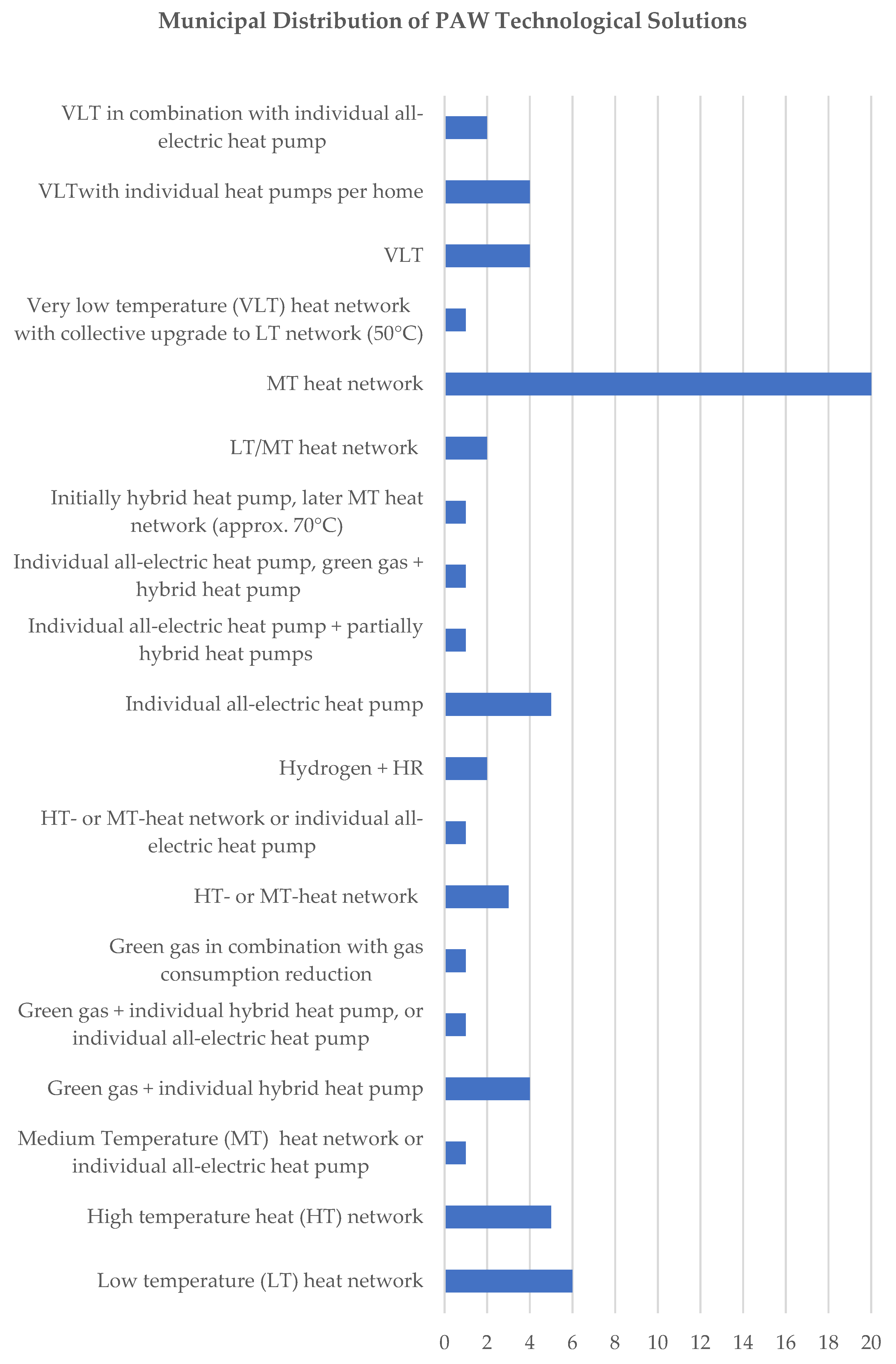

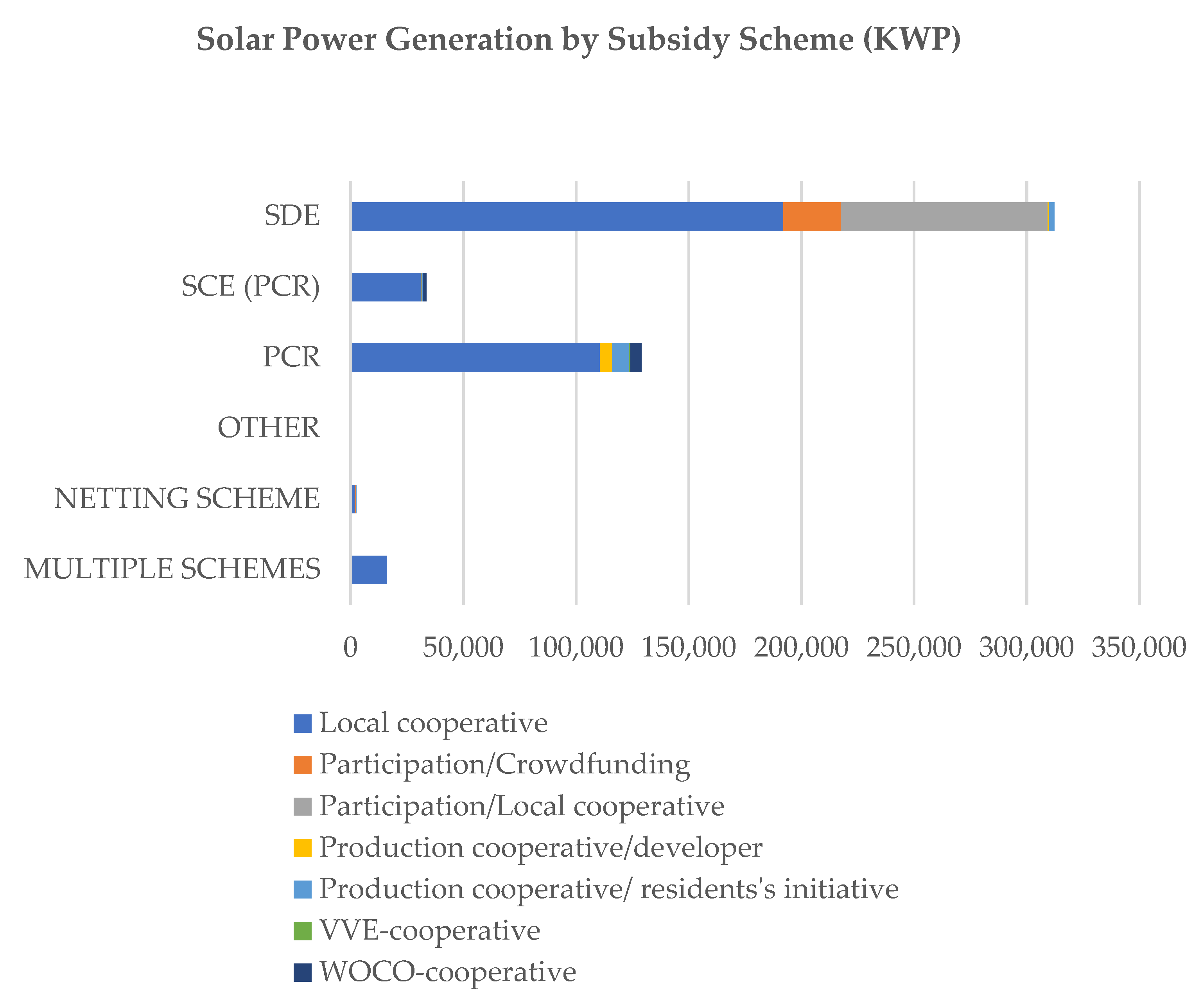

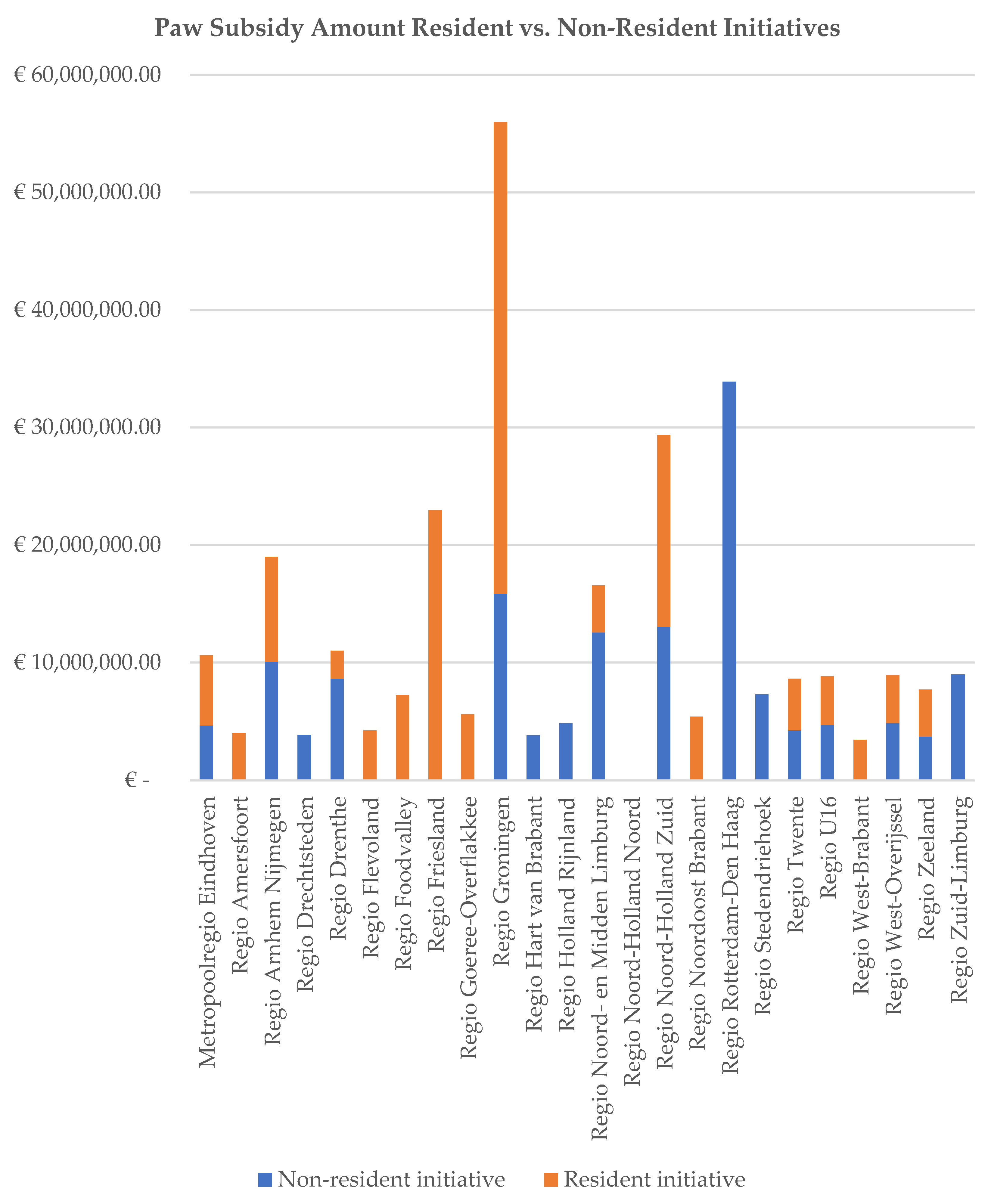

Table 5 provides an overview of key subsidy mechanisms. Together, the SDE++, SCE and PAW demonstrate how financial incentives are aligned with CEI goals, although their effectiveness depends on local uptake and grid capacity. Building on the DCA’s framework, the RES translates national targets into region-specific plans, ensuring that high-level goals are grounded in local realities across 30 energy regions of renewable energy. Each region develops strategies for renewable energy generation, heat utilization, and community participation, integrated into local and national policies.

Between 2019 and 2021, the RES Programme had an annual budget of EUR 22.5 million, with EUR 2.5 million allocated to stakeholder collaboration. In July 2021, the RES was adopted by municipal, provincial, and waterboard councils, defining projects to contribute to the national target of 35 terawatt-hours (TWh) energy from onshore sources. The National RES Programme is managed by a Commissioning Consultation Body, with guidance from a program council and an Administrative Consultation group. This ensures policy alignment and facilitates a biennial review cycle for updates toward 2030 and 2050 goals. the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) monitors RES progress under the 35 TWh target. In its latest report, it highlights that regions are on track to meet or exceed the 35 TWh goal, prompting discussions on increasing future targets [

2].

A core RES component is its flexible approach to local ownership, allowing regions to interpret the 50 percent local ownership ambition based on governance capacity and economic conditions. Oversight is maintained through municipal, provincial, and waterboard councils, supported by the National RES Programme. Despite its structured approach, challenges remain, particularly grid congestion, balancing regional flexibility with national coordination, and ensuring local ownership ambitions are realized.

In turn, municipalities develop energy transition visions that align with both the DCA and their regional RES, adapting broad goals to community-specific contexts. While the format varies across municipalities, these visions integrate technical–economic analyses, regional heating network strategies, and resident consultations to tailor policies to local needs. Transition Vision Documents (TVWs) serve as a cornerstone of municipal energy planning, developed through consultations with organizations, residents, and experts. For example, in Zeewolde, the municipality collaborates with the Nature and Environment Federation Flevoland and the Energy Desk to provide tailored advice on energy savings and sustainability. Community engagement is a key element, with municipalities employing public consultations, resident surveys, and workshops to ensure broad participation in decision-making.

Municipal energy transition plans also anticipate legislative changes, such as the Collective Heat Supply Act and the Municipal Heat Supply Instruments Act, which influence infrastructure and local decision-making. Flexibility is emphasized in these plans, allowing municipalities to accommodate multiple routes for natural gas-free heating and energy generation. Various financial instruments, including local sustainability funds and loans, are integrated into municipal policies to support community-led initiatives. Local ownership remains a central component, promoting community engagement and ensuring that the benefits of renewable energy projects remain within local economies. One-third of municipalities have adopted the 50 percent local ownership goal in various forms, as shown by several models (

Table 6). The 50 percent Local Ownership Model presents a legally binding requirement for local communities to hold a minimum stake, whereas the Flexible Local Ownership Model allows for more adaptable participation, with thresholds between 20 and 50 percent. The Voluntary Ownership Model, on the other hand, encourages local involvement but lacks a formal mandate, providing municipalities with the flexibility to choose their level of engagement based on local needs and conditions. This diversity reflects local innovation in policy but also indicates variability that could impact consistency across regions. One of the most widely adopted models is the 50 percent Ownership or Fund Model, which mandates a minimum of 50 percent local ownership for renewable energy projects, with the option to contribute to a sustainability or local fund when direct ownership is not feasible.

While the legal enforcement of the 50 percent local ownership goal is viewed as a strong policy tool to ensure consistent participation, there is also recognition that flexible models offer significant benefits in allowing municipalities to adapt to local conditions. In practice, the Flexible Local Ownership Model is seen as more suitable for fostering local engagement without imposing rigid requirements, allowing for tailored solutions that align with community capacities. However, the 50 percent Local Ownership Model with legal enforcement could provide a more consistent and standardized approach, especially in regions that require stronger mandates to overcome barriers to participation.

Regardless of the participation model, municipalities face significant challenges, particularly in transitioning the built environment away from natural gas. The heat transition presents financial and logistical obstacles, especially for smaller municipalities with limited resources. Deciding on heating alternatives for residential areas is a complex and resource-intensive task, requiring substantial funding, stakeholder coordination, and long-term planning. These factors complicate municipal energy transition implementation, highlighting the need for continued policy refinement and support.

Summary of Findings

In this section, we aimed to examine the Dutch policy instrument mix that supports CEIs at different governance levels, focusing on the policy processes, instrument mix, and dimensions. In sum, the Dutch policy instrument mix provides a multi-tiered framework for CEIs, aiming to align national climate targets and local implementation. While the DCA establishes overarching goals and financial mechanisms, the RES enables regional adaptation, and municipal visions ensure localized engagement. Subsidy schemes like SDE++ and SCE play crucial roles in financing renewable energy projects and CEIs, but their effectiveness depends on local uptake and grid capacity. However, these interactions between policy instruments at different governance levels can create trade-offs. While national goals set by the DCA provide a clear direction, the flexibility offered by the RES and municipal visions may result in misalignment or the inconsistent application of local ownership targets.

These findings extend beyond the Netherlands. Germany and Switzerland use decentralized support mechanisms that complement national policies, with local governments playing a vital role in sustaining community energy projects. However, local engagement in these countries can sometimes face barriers, particularly when national goals conflict with regional capabilities [

72]. In contrast, France follows a more centralized approach, where national energy targets are set top-down, but local energy initiatives face challenges due to a lack of strong local integration and limited financial support. As a result, community energy in France is less developed and often constrained by national policies that do not fully engage local actors [

73]. These examples highlight the trade-offs between national alignment and local adaptation, with the Dutch model offering a more coherent connection between national objectives and regional or municipal implementation, while countries like France struggle with top-down policies that limit local ownership and flexibility.

The following section explores these interactions and trade-offs further, illustrating how, despite efforts for policy alignment, the flexibility at the regional and local levels can lead to misalignment in achieving the national targets for local ownership and community participation. This comparison shows that while the Netherlands’ approach provides a clear framework, balancing national goals with regional flexibility remains a key challenge in implementing CEIs effectively.

4.2. Niche–Regime Interactions

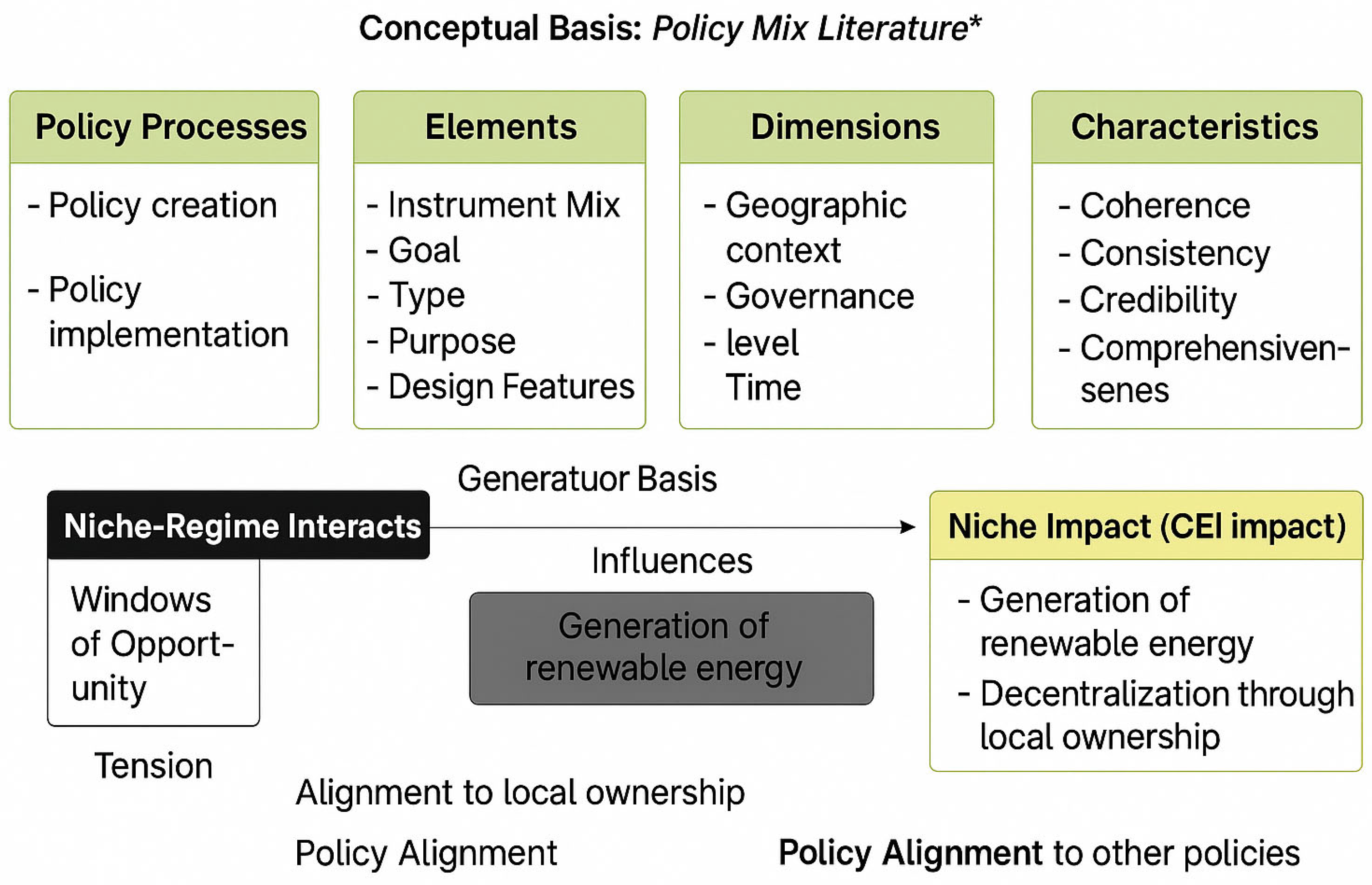

This section explores how the Dutch policy instrument mix aligns or misaligns across governance levels while also evaluating the internal characteristics of these instruments. The goal is to answer the following research question: Are the policy instruments supporting CEIs aligned or misaligned? We assess the extent to which these instruments coordinate goals, implementation, governance roles, and infrastructure integration, drawing on the core characteristics of consistency, credibility, comprehensiveness, and coherence.

4.2.1. Characteristics and Alignment of the Dutch Energy Policy Mix

The Dutch energy policy mix includes a range instruments deployed across multiple governance levels, from EU directives and national strategies to provincial plans and local initiatives. Ensuring vertical alignment across these levels is essential for translating national climate goals into effective action.

Table 7 outlines the characteristics of the key instruments at each governance level.

The DCA demonstrates strong consistency through its integrated design, linking emission reduction targets with structures like the Electricity Platform. By incorporating a continuous improvement cycle through integrated evaluation and monitoring, the DCA enhances policy stability. Its credibility is bolstered by data from institutions such as Statistics Netherlands, the main environmental and health institute RIVM, and PBL and its alignment with international frameworks like the Paris Agreement, the EU Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan, and the Environmental Planning Act. However, transparency gaps exist as progress is reported without clearly defined challenges, undermining trust in reporting. The DCA is comprehensive, it addresses economic, social, and environmental dimensions, but its 35 TWh target for renewable electricity has been critiqued as unambitious, given the existing 25 TWh capacity. Coherency is supported by clearly defined responsibilities and logical progression from climate problems to solutions, although there is some duplication with earlier instruments, such as the 2013 Energy Law.

The RES adapts national goals to regional context through collaborative planning and cost assessments. This alignment is evident in shared emission targets, the incorporation of local ownership, and structured stakeholder engagement mechanisms. Best practice examples, such as Groningen and Flevoland, show strong consistency. Groningen ties its RES to legacy documents and maintains local ownership ambitions across municipalities, while Flevoland coordinates effectively via its Flevoland Energy Agreement (FEA). However, the RES suffers from varying regional interpretations of local ownership, and the lack of a formal governance structure leads to incoherence in its implementation.

Monitoring practices have also been criticized for being more promotional than evaluative. Consequently, while the RES offers tailored approaches to meet national renewable energy goals, regional variability in policy execution and local ownership reveals a misalignment between the flexibility granted to regions and the national coherence needed for successful implementation. This regional flexibility underscores a tension between niche ambitions (community energy ownership) and regime constraints (national policy coherence and enforcement). The variability in policy execution across regions can be seen as regime-level resistance to fully incorporating CEIs, demonstrating a stretch-and-transform interaction where niches are attempting to disrupt the regime’s established systems.

At the municipal level, energy transition visions vary in scope, structure, and stakeholder involvement. Many municipalities develop comprehensive strategies encompassing environmental, spatial, and social dimensions. However, some municipalities employ flexible participation models without defined criteria, and many lack clearly assigned roles for CEIs, resulting in fragmented implementation. Despite this, most municipal visions align with their stated objectives, contributing to local consistency and coherence. The comprehensiveness of the policy mix varies by governance level, with national policies addressing broader issues and regional and municipal policies focusing on specific, localized challenges. This layered approach ensures a comprehensive policy mix across levels, though the dimensions differ slightly.

In summary, misalignments arise when local governments and community energy groups seek the flexibility to innovate beyond uniform national prescriptions, while national authorities prioritize consistency and standardization. This creates a trade-off between local autonomy and central coordination. Granting municipalities more leeway can encourage innovation tailored to specific community needs, but too much divergence can undermine the coherence of national policies.

These multi-level governance misalignments are not unique to the Dutch energy sector. Many countries face similar challenges in aligning national targets with local implementation. For instance, Austria’s approach to multi-level governance has generally achieved a good alignment of energy targets across governance levels, though there are still gaps in areas like data sharing and spatial planning [

74]. A key lesson is that aligning policy instruments vertically is essential for providing stability and fostering local action. Without such alignment, policy effectiveness suffers. This issue of misalignment also extends beyond energy to other sectors, such as transport, where conflicting priorities between national infrastructure investments and local mobility plans can hinder effective, coordinated action [

75].

4.2.2. Local Ownership Ambition

A significant misalignment exists in the interpretation and enforcement of the 50 percent local ownership ambition. While the DCA supports this goal through subsidy schemes and innovation programs, the lack of legal enforcement at the national level leads to inconsistencies at regional and municipal levels. Some municipalities have incorporated mandatory ownership requirements, while others rely on voluntary participation frameworks, resulting in unequal implementation across regions. This inconsistency in local ownership policies highlights the misalignment between national goals and local execution.

From an MLP, this reveals regime resistance to fully integrating the niche of community energy ownership, preventing a fit-and-conform relationship. The variability in policy enforcement, along with the use of voluntary models in some municipalities, suggests that CEIs are pushing the regime towards more participatory and community-centered practices, creating a stretch-and-transform dynamic. However, this fragmentedpolicy landscape limits the ability of CEIs to thrive and scale consistently. Additionally, RES guidance documents on local ownership lack enforceability, contributing to regional disparities in CEI ownership structures.

Comparative research from England, Scotland, and Wales shows that where local governments have ambition but lack full powers, policy mixes can fall short in comprehensiveness [

76]. Furthermore, while evidence confirms that emphasizing local ownership in energy projects can boost public support, approaches to enforce this ambition vary significantly. Unlike the Dutch voluntary approach, Denmark legally mandates at least 20 percent local ownership in all new wind projects [

77]. In contrast, Germany has not enacted a formal mandate but still achieved high community investment in renewables through supportive national policies (e.g., feed-in tariffs), which enabled cooperatives and citizen investors, aligning local interests with the national Energiewende strategy [

74]. However, when local authorities are empowered to choose their own participatory models, the lack of national support and resources (e.g., for grid expansion or enforcing ownership rules) can impede the success of CEIs.

4.2.3. Grid Infrastructure and Energy Planning

A well-coordinated approach to grid infrastructure and energy planning is crucial in a multi-level governance system. In the Netherlands, responsibilities for planning are distributed: the national government, together with the national transmission system operator, sets strategic directions for the electricity grid, while regional grid operators and local authorities manage distribution networks and spatial planning for energy projects. Close coordination among these levels is essential to prevent bottlenecks. However, there is a clear misalignment in the coordination between national, regional, and local governance levels in the Netherlands. The RES aims to optimize site selection for wind and solar projects, yet grid congestion significantly hampers renewable energy integration. While regions like Groningen align site selection with grid infrastructure to minimize costs, others experience significant delays in energy connections due to network congestion.

This situation illustrates a governance dilemma: local and regional actors have been very effective in driving the energy transition “from below”, but without proportional top-down investment and planning for grid upgrades, the system’s consistency and reliability are jeopardized. This creates trade-offs: enforcing uniform grid standards and centralized planning ensures stability and fairness (ensuring that every region meets the same safety and reliability criteria). However, an overly rigid approach could stifle local innovations, such as community micro-grids or energy storage projects. Conversely, highly decentralized planning could lead to fragmented solutions that complicate the nationwide balancing of supply and demand. Our study aligns with Olbrich et al.’s insight that a more integrated, “system-building” approach is needed. In tthe Netherlands, this could involve jointly planning energy infrastructure upgrades alongside renewable rollout and aligning legal frameworks to ensure local initiatives operate under consistent rules [

78].

The grid congestion issue exemplifies a regime-level constraint that hinders the integration of niche innovations into the existing energy system. This is a classic case of misalignment, where the energy system’s infrastructure—a key part of the regime—fails to accommodate the emerging needs of niches like community energy. This misalignment leads to a stretch-and-transform dynamic, where CEIs must either adapt to the constraints of the current infrastructure or push for regime change in the form of more robust energy planning and grid expansion.

These regime-level constraints in the Netherlands reflect a broader trend: many countries face challenges in synchronizing infrastructure upgrades with decentralized energy expansion. For example, in the United States, thousands of renewable projects are stuck in interconnection queues due to insufficient grid development [

79]. Similarly, an analysis of Germany’s net-zero transition policy mix revealed that sectoral silos and unclear linkages between policy elements undermined the overall credibility of the transition effort. Stakeholders faced uncertainty and feared wasted investments due to coordination gaps [

78]. In sum, when infrastructure governance remains centralized and uncoordinated with local renewable initiatives, policy goals are undermined by technical constraints. Similar integration issues arise in sustainable transport electrification, where the rollout of electric vehicle charging infrastructure must align with grid upgrades and local plans, further underscoring the need for coordinated planning across governance levels.

4.2.4. Governance Level Interactions: Tensions and Collaboration

The interactions between governance levels in the Dutch clean energy transition are characterized by both tensions and constructive collaboration. On the one hand, divergent interests and perspectives at different levels can lead to conflict. National government bodies are primarily focused on achieving aggregate targets, such as emission reduction and increasing the share of renewables, while local governments prioritize spatial planning concerns, community acceptance, and locally tailored benefits. Top-down directives, like assigning a wind farm quota to a region, can face bottom-up resistance when local stakeholders that feel their concerns—such as landscape esthetics, noise, or participation—are overlooked.

At the national level, regional coordinators and account managers facilitate high-level discussions, ensuring policy alignment. However, changing national laws requires coordinated regional advocacy, which poses additional challenges. Knowledge-sharing initiatives, like the Participatory Coalition, enhance coordination among CEI stakeholders and promote cross-regional policy learning. However, resistance at different governance levels leads to varying rates of adoption for the RES. The 2013 Energy Agreement introduced a centralized wind planning scheme, but its regional implementation varies. The RES, lacking a legal foundation, depends on inter-cooperation for success, making modifications to regional energy plans complex. Furthermore, unforeseen environmental and economic factors create additional policy tensions. For example, Groningen’s RES highlights the challenge of achieving housing cost neutrality without additional national funding, underlining the need for more financial and technical support. This points to a regime-level facilitation of niche-level innovations, where regional and national policies must align to support CEIs.

These challenges are not purely technical but are deeply rooted in governance issues that span multiple policy and political levels. The lack of detailed enforcement at the local level creates a regime-level constraint for CEIs, highlighting the difficulty of integrating these niche innovations into a policy regime that lacks clear guidelines for local-level implementation. In MLP terms, this is a classic example of misalignment, where CEIs—being niche innovations—are not adequately supported within the existing energy regime, preventing a smooth fit-and-conform integration. The absence of strong enforcement for local ownership ambitions reflects the regime’s resistance to fully integrating these transformative innovations at the local level, creating a stretch-and-transform dynamic. To address these challenges, greater legal clarity, infrastructure investment, and strengthened coordination between governance levels are needed to establish a cohesive and effective CEI support framework. Our findings, which underscore the importance of coherent action across national, regional, and local levels for CEI success, are consistent with broader international evidence. A global review by Leonhardt et al. highlights the critical need for coordination between levels of government to support community energy, noting that misaligned policies can hinder implementation in any country [

80].

The Dutch experience of tension between national renewable targets and local governments’ capacities is mirrored in other countries. In Germany, for example, some federal states imposed restrictive wind siting rules that clashed with national expansion goals, demonstrating how misaligned authority can stall implementation [

81]. On the other hand, when multi-level interactions are managed effectively, as seen in Austria’s coordinated regional and local implementation of climate measures, policy execution becomes more successful [

82]. Similar multi-level governance challenges and the need for cross-level collaboration are also evident in areas like climate adaptation and public transport policy, where unclear divisions of responsibility can impede progress [

75].

4.2.5. Summary of Findings

In summary, the Dutch policy instrument mix demonstrates strong alignment in overarching objectives, particularly in linking financial incentives to CEI development and integrating national goals into regional and municipal policies. However, misalignments persist in local ownership enforcement, grid infrastructure readiness, and regional governance structures, as noted in

Table 8. The DCA sets broad goals and lacks detailed enforcement at the local level, which may limit its effectiveness. This misalignment between high-level policy ambition and local policy execution highlights a key challenge in multi-level governance frameworks, where policies need to be operationalized at all levels for real impact. The misalignments observed in the policy mix—such as the inconsistent enforcement of local ownership requirements or grid infrastructure bottlenecks—highlight that a fragmented policy environment can undermine the success of decentralized energy initiatives, thereby slowing down the transition to a low-carbon energy system.