How Visual Style Shapes Tourism Advertising Effectiveness: Eye-Tracking Insights into Traditional and Modern Chinese Ink Paintings

Highlights

- Traditional ink ads boost aesthetic ratings and cultural resonance in nature contexts.

- Modern ink ads grab attention faster and perform better in urban settings.

- Visual style–destination congruence significantly affects ad effectiveness.

- Cultural familiarity drives traditional style preference; novelty fuels modern appeal.

- The findings expand Cultural Schema Theory and aesthetic processing in advertising.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Aesthetic processing and processing fluency: Aesthetic experience unfolds from early perception and attention to meaning formation and appraisal; when visual features align with internal schemas, fluency increases, enhancing liking and evaluation.

- (2)

- Style–content congruity (match-up): Messages are more persuasive when form fits semantics/context, improving comprehension and memory.

- (3)

- Environmental psychology (natural vs. urban): Attention Restoration Theory and Psychoevolutionary Theory suggest natural scenes elicit harmony/low arousal and restoration, whereas urban scenes afford stimulation and novelty seeking.

- (4)

- Cultural schemas and cross-cultural perception: Cultural background shapes gaze allocation and style interpretation, moderating the effectiveness of stylistic cues across audiences.

- (1)

- Insufficient style coverage and cultural evidence: Systematic, mechanism-focused comparisons of culturally artistic styles—especially traditional ink—are scarce; differences between traditional and modern ink along the attention–evaluation–intention pathway remain unclear.

- (2)

- Methodological siloing: Most studies rely on a single method (e.g., surveys), lacking an integrated view that combines objective process data (eye movements) with subjective judgments, obscuring the pathway from visual stimuli to psychological and behavioral outcomes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Visual Attention and Aesthetic Processing Mechanisms in Tourism Advertising

2.2. Tourism Intention and Advertising Effect Theory

2.3. Visual Style, Cultural Preference, and Perceptual Mechanisms

2.4. Destination Context (Natural vs. Urban) as a Theoretical Moderator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Experimental Design

3.3. Stimuli Materials

3.4. Instruments

3.5. Procedures

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Aesthetic Evaluation

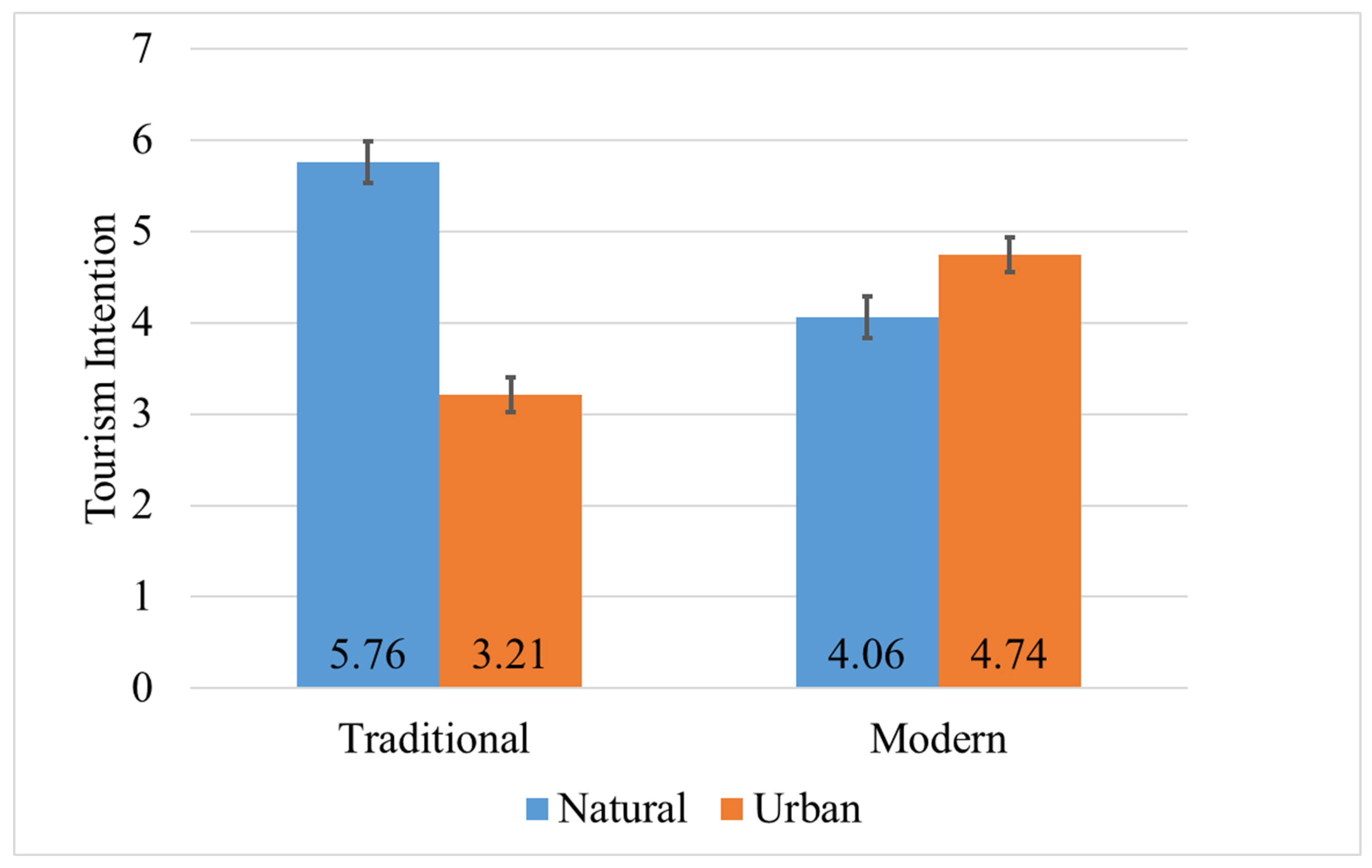

4.1.2. Tourism Intention

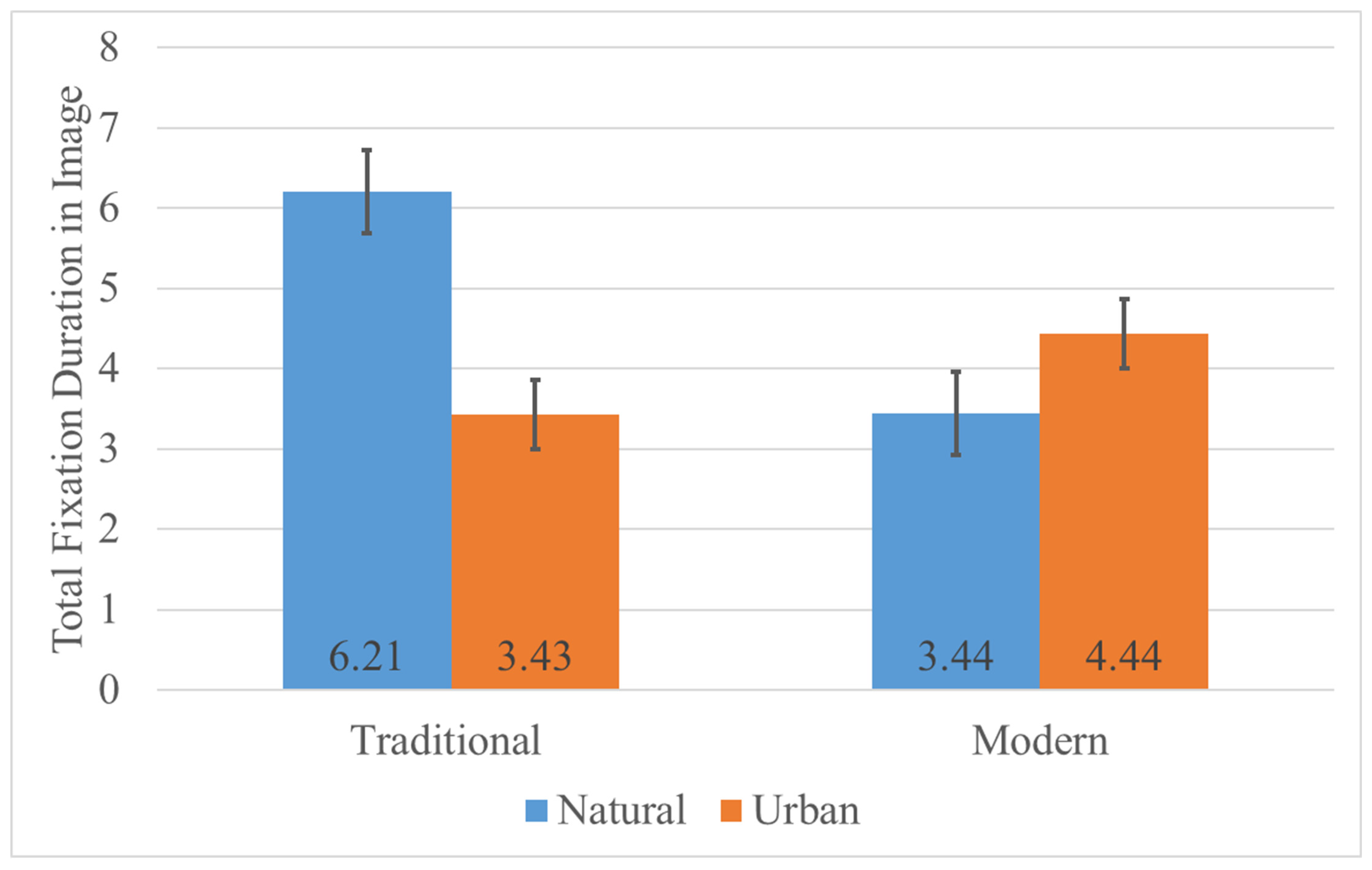

4.1.3. Total Fixation Duration

4.2. Qualitative Results

- (1)

- Perception of Visual Style Characteristics

- (2)

- Aesthetic Preference and Reasons

- (3)

- Feedback on Visual Elements

- (4)

- Emotional Connection and Cultural Meaning

- (5)

- Impact on Tourism Intention

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Xie, J.; Xie, M.; Shi, J. Image and Text Presentation Forms in Destination Marketing: An Eye-Tracking Analysis and a Laboratory Experiment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1024991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. A Review of Eye-Tracking Research in Marketing. In Review of Marketing Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 123–147. ISBN 978-0-7656-2092-7. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, H.; Belke, B.; Oeberst, A.; Augustin, D. A Model of Aesthetic Appreciation and Aesthetic Judgments. Br. J. Psychol. 2004, 95, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, T.; Tractinsky, N. Assessing Dimensions of Perceived Visual Aesthetics of Web Sites. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2004, 60, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y. Influence of Material and Decoration on Design Style, Aesthetic Performance, and Visual Attention in Chinese-Style Chairs. For. Prod. J. 2024, 74, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Hernández-Méndez, J.; Gómez Carmona, D. Measuring Advertising Effectiveness in Travel 2.0 Websites through Eye-Tracking Technology. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 200, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbus, A.L. Eye Movements and Vision; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1967; ISBN 978-1-4899-5381-0. [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist, K.; Nyström, M.; Andersson, R.; Dewhurst, R.; Halszka, J.; van de Weijer, J. Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-969708-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lohse, G.L. Consumer Eye Movement Patterns on Yellow Pages Advertising. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Ibáñez-Zapata, J.-Á. Evaluating Communication Effectiveness Through Eye Tracking: Benefits, State of the Art, and Unresolved Questions. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2023, 60, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K.; Rotello, C.M.; Stewart, A.J.; Keir, J.; Duffy, S.A. Integrating Text and Pictorial Information: Eye Movements When Looking at Print Advertisements. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2001, 7, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Saito, T.; Onuma, T. Eye-Tracking Research on Sensory and Consumer Science: A Review, Pitfalls and Future Directions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M.; Batra, R. The Stopping Power of Advertising: Measures and Effects of Visual Complexity. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010, 74, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism Image, Evaluation Variables and after Purchase Behaviour: Inter-Relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Ye, C.; Huang, Y. Does Destination Nostalgic Advertising Enhance Tourists’ Intentions to Visit? The Moderating Role of Destination Type. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Huang, Z.; Bao, J. A Model of Tourism Advertising Effects. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.-H.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Will Destination Image Drive the Intention to Revisit and Recommend? Empirical Evidence from Golf Tourism. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2021, 23, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Yin, M.; Cao, L.; Sun, S.; Wang, X. Predicting Emotional Experiences through Eye-Tracking: A Study of Tourists’ Responses to Traditional Village Landscapes. Sensors 2024, 24, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C. Destination Image and Its Functional Relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, S.; Lacoste-Badie, S.; Droulers, O. Face Presence and Gaze Direction In Print Advertisements. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigre Moura, F.; Gnoth, J.; Deans, K.R. Localizing Cultural Values on Tourism Destination Websites: The Effects on Users’ Willingness to Travel and Destination Image. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M. (Ed.) Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-203-01067-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, H. Cultural Schema Theory. In Theorizing About Intercultural Communication; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 401–418. ISBN 978-0-7619-2748-8. [Google Scholar]

- Skavronskaya, L.; Scott, N.; Moyle, B.; Le, D.; Hadinejad, A.; Zhang, R.; Gardiner, S.; Coghlan, A.; Shakeela, A. Cognitive Psychology and Tourism Research: State of the Art. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzotto, F.; Paolini, P.; Speroni, M.; Proll, B.; Retschitzegger, W.; Schwinger, W. Ubiquitous Access to Cultural Tourism Portals. In Proceedings of the 15th International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Zaragoza, Spain, 3 September 2004; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vasavada, F.; Kour, G. Heritage Tourism: How Advertising Is Branding the Intangibles? J. Herit. Manag. 2016, 1, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.Z.; Wilson, R. Translating Tourism Promotional Materials: A Cultural-Conceptual Model. Perspectives 2018, 26, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sparks, B.A. An Eye-Tracking Study of Tourism Photo Stimuli. J. Travel Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xue, F.; Barton, M.H. Visual Attention, Brand Personality and Mental Imagery: An Eye-Tracking Study of Virtual Reality (VR) Advertising Design. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Cao, Z.; Mao, Y.; Mohd Isa, M.H.; Abdul Nasir, M.H. Age-Related Differences in Visual Attention to Heritage Tourism: An Eye-Tracking Study. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2025, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A Systematic Review of the Attention Restoration Potential of Exposure to Natural Environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plutchik, R. Chapter 1—A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In Theories of Emotion; Plutchik, R., Kellerman, H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-0-12-558701-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination Positioning Analysis through a Comparison of Cognitive, Affective, and Conative Perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Ban, S.; Zhang, G. Design Criticism and Eye Movement Strategy in Reading: A Comparative Study of Design and Non-Design Students. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2024, 35, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolinski, S.; Strack, F. The Architecture of Intuition: Fluency and Affect Determine Intuitive Judgments of Semantic and Visual Coherence and Judgments of Grammaticality in Artificial Grammar Learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcadams, D.P. The Problem of Narrative Coherence. J. Constr. Psychol. 2006, 19, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, N. From Environmental Aesthetics to Narratives of Change. Contemp. Aesthet. (J. Arch.) 2012, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Scott, N.; Wu, Y. Tourism Destination Advertising: Effect of Storytelling and Sensory Stimuli on Arousal and Memorability. Tour. Rev. 2023, 79, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J.; Ilkka, I.; Ahmed Mohamed Sayed, K.; Jung, S.-G.; Jansen, B.J. How Does Personification Impact Ad Performance and Empathy? An Experiment with Online Advertising. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Wood, E. Familiarity and Novelty in Aesthetic Appreciation: The Case of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 105, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z. The Impact of Cover Image Authenticity and Aesthetics on Users’ Product-Knowing and Content-Reading Willingness in Social Shopping Community. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Fang, C.; Lin, H.; Chen, J. A Framework for Quantitative Analysis and Differentiated Marketing of Tourism Destination Image Based on Visual Content of Photos. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z. The Power of Visuals in Destination Advertising. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 107, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Lai, I.K.W.; Wong, J.W.C. How Museum Posters Arouse Curiosity and Impulse to Visit among Young Visitors: Interactive Effect of Visual Appeal and Textual Introduction. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamış, E.; Pınarbaşı, F. Unfolding Visual Characteristics of Social Media Communication: Reflections of Smart Tourism Destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Rahimi, R.; Qi, J. Exploring Visual Attention and Perception in Hospitality and Tourism: A Comprehensive Review of Eye-Tracking Research. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagalp, I.; Södergren, J. On Ads as Aesthetic Objects: A Thematic Review of Aesthetics in Advertising Research. J. Advert. 2024, 53, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Hui, M.K.; Zhou, L.; Li, S. Cultural Congruity and Extensions of Corporate Heritage Brands: An Empirical Analysis of Time-Honored Brands in China. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, S.M.M.; Song, B.; Shaari, N.; Perumal, V. Integration of Aesthetics and Creative Design: The Influence of Traditional Ru Porcelain on Product Design. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2025, 10, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J. The Influence of Design Aesthetics on Consumers’ Purchase Intention Toward Cultural and Creative Products: Evidence From the Palace Museum in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 939403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.G.; Gong, Z.H.; Reichert, T. The Impact of Visual Sexual Appeals on Attention Allocation within Advertisements: An Eye-Tracking Study. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 708–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; van Trijp, H. From Desktop to Supermarket Shelf: Eye-Tracking Exploration on Consumer Attention and Choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Research on Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Cultural and Creative Products—Metaphor Design Based on Traditional Cultural Symbols. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, Y.; Wu, T. The Use of Traditional Chinese Aesthetics in Modern Television Advertising and Consumer Perception. Stud. Art. Archit. 2024, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Mustafa, M.; Isa, M.H.M.; Mao, Y. Collision of Tradition and Visual Perception: Aesthetic Evaluation and Conservation Intent in Adapting Traditional Chinese Gates within Architectural Heritage. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M.; Muldrow, A.F.; Rosengren, S. Diversity and Inclusion in Advertising Research. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Style | Destination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Urban | Total | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Traditional | 5.47 | 0.50 | 4.44 | 0.75 | 4.96 | 0.82 |

| Modern | 3.23 | 0.81 | 4.25 | 0.68 | 3.74 | 0.90 |

| Total | 4.35 | 1.31 | 4.35 | 0.72 | 4.35 | 1.05 |

| Variable | I | J | Mean Difference (I−J) | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Traditional | Modern | 2.238 | 221.109 | <0.001 | 0.739 |

| Urban | Traditional | Modern | 0.194 | 1.462 | 0.230 | 0.0108 |

| Traditional | Natural | Urban | 1.025 | 88.837 | <0.001 | 0.532 |

| Modern | Natural | Urban | −1.019 | 87.757 | <0.001 | 0.529 |

| Style | Destination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Urban | Total | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Traditional | 5.76 | 0.48 | 3.21 | 0.75 | 4.48 | 1.43 |

| Modern | 4.06 | 0.57 | 4.74 | 0.63 | 4.40 | 0.69 |

| Total | 4.91 | 1.01 | 3.98 | 1.03 | 4.35 | 1.12 |

| Variable | I | J | Mean Difference (I−J) | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Traditional | Modern | 1.706 | 208.286 | <0.001 | 0.728 |

| Urban | Traditional | Modern | −1.537 | 98.874 | <0.001 | 0.559 |

| Traditional | Natural | Urban | 2.556 | 381.752 | <0.001 | 0.830 |

| Modern | Natural | Urban | −0.687 | 27.613 | <0.001 | 0.261 |

| AOI | Style | Destination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Urban | Total | |||||

| M (s) | SD | M (s) | SD | M (s) | SD | ||

| Image | Traditional | 6.21 | 1.60 | 3.43 | 1.03 | 4.82 | 1.94 |

| Modern | 3.44 | 1.40 | 4.44 | 1.22 | 3.94 | 1.40 | |

| Total | 4.82 | 2.05 | 3.94 | 1.23 | 4.38 | 1.74 | |

| Text | Traditional | 5.52 | 1.40 | 8.95 | 1.34 | 7.23 | 2.20 |

| Modern | 4.41 | 1.14 | 7.13 | 1.20 | 5.77 | 1.80 | |

| Total | 4.96 | 1.38 | 8.04 | 1.56 | 6.50 | 2.13 | |

| Variable | I | J | Mean Difference (I−J) | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Traditional | Modern | 2.777 | 68.175 | <0.001 | 0.466 |

| Urban | Traditional | Modern | −1.017 | 16.245 | <0.001 | 0.172 |

| Traditional | Natural | Urban | 2.785 | 104.853 | <0.001 | 0.573 |

| Modern | Natural | Urban | −1.008 | 13.744 | <0.001 | 0.150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, F.; Shao, X.; Tao, Z.; Romainoor, N.H.M.; Saat, M.K.M. How Visual Style Shapes Tourism Advertising Effectiveness: Eye-Tracking Insights into Traditional and Modern Chinese Ink Paintings. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2025, 18, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jemr18050042

Liu F, Shao X, Tao Z, Romainoor NHM, Saat MKM. How Visual Style Shapes Tourism Advertising Effectiveness: Eye-Tracking Insights into Traditional and Modern Chinese Ink Paintings. Journal of Eye Movement Research. 2025; 18(5):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jemr18050042

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Fulong, Xiheng Shao, Zhengwei Tao, Nurul Hanim Md Romainoor, and Mohammad Khizal Mohamed Saat. 2025. "How Visual Style Shapes Tourism Advertising Effectiveness: Eye-Tracking Insights into Traditional and Modern Chinese Ink Paintings" Journal of Eye Movement Research 18, no. 5: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jemr18050042

APA StyleLiu, F., Shao, X., Tao, Z., Romainoor, N. H. M., & Saat, M. K. M. (2025). How Visual Style Shapes Tourism Advertising Effectiveness: Eye-Tracking Insights into Traditional and Modern Chinese Ink Paintings. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 18(5), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jemr18050042