Bridging Financial and Operational Gaps in Supply Chain Finance: An Information Processing Theory Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

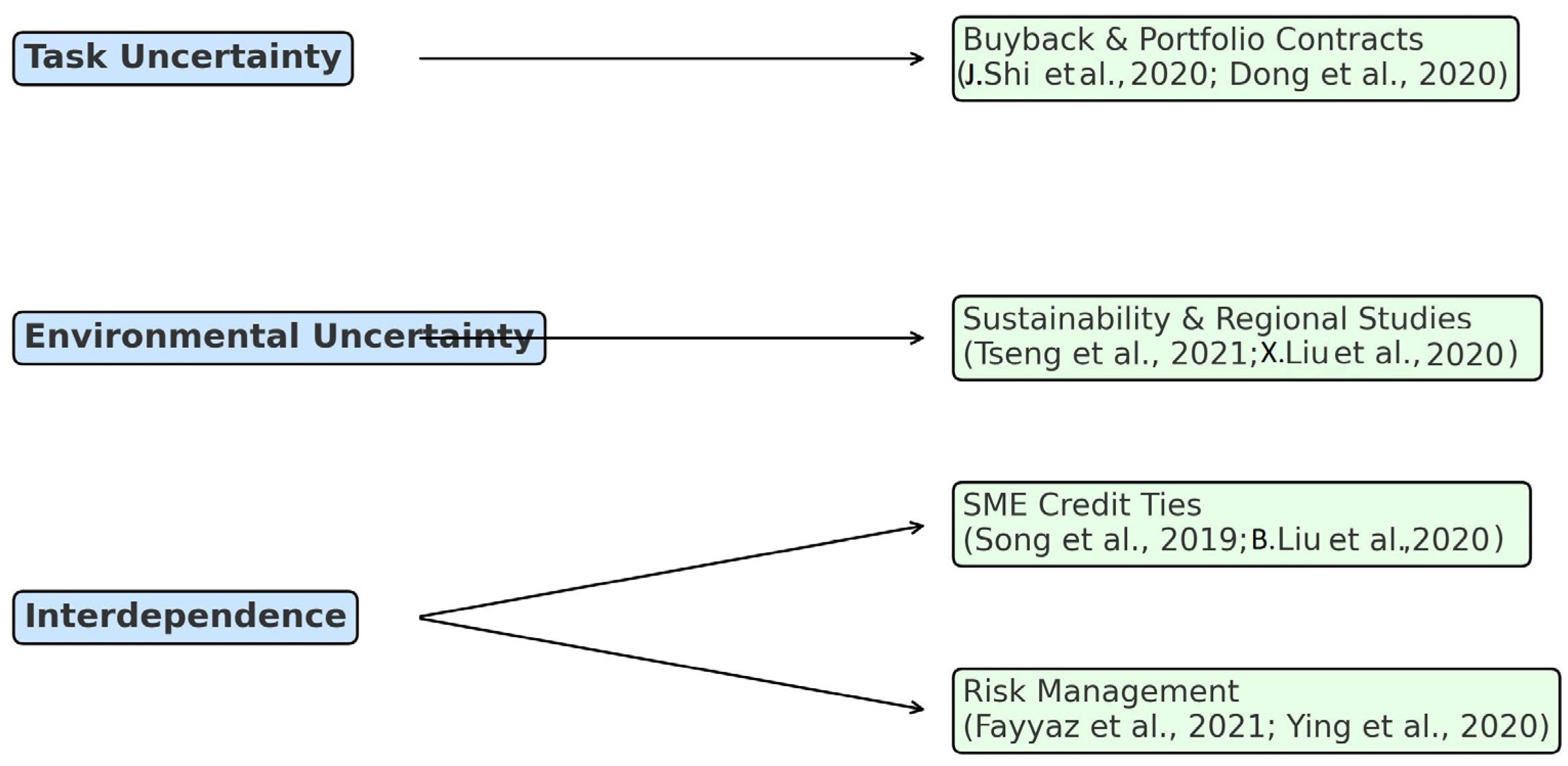

- Task features: Operational–financial coordination within models such as buyback contracts (J. Shi et al., 2020) or financing a portfolio (Dong et al., 2020).

- Environmental uncertainty: Sectoral/regional financing disparities, for example, rural SCF inefficiencies in China (X. Liu et al., 2020).

- Interdependence: Collaborative financing mechanisms, e.g., power-configured trade credit (B. Liu et al., 2020) and risk-sharing among actors (Ying et al., 2020).

2. Theories Used in Supply Chain Finance

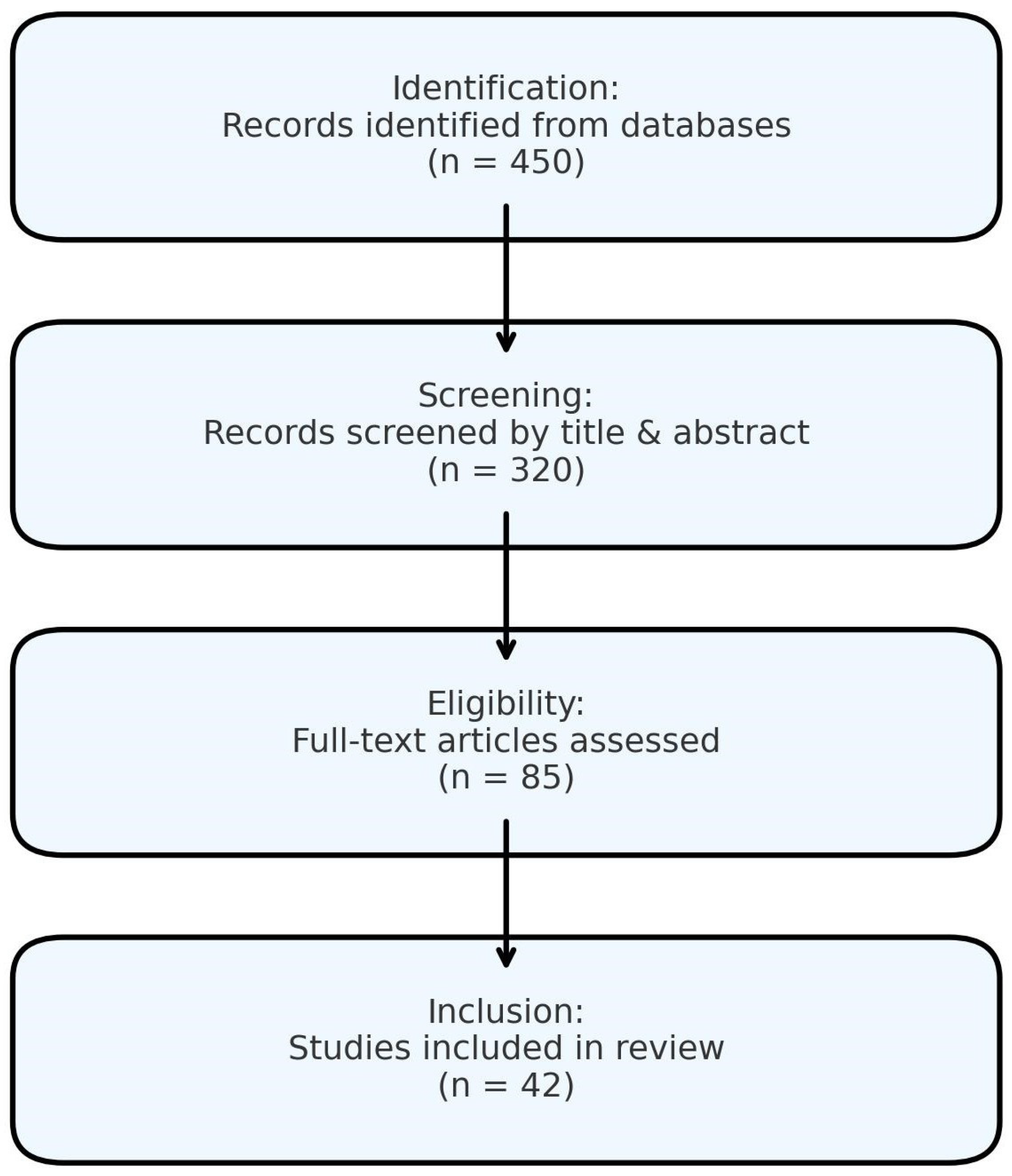

3. Methodology

- (i)

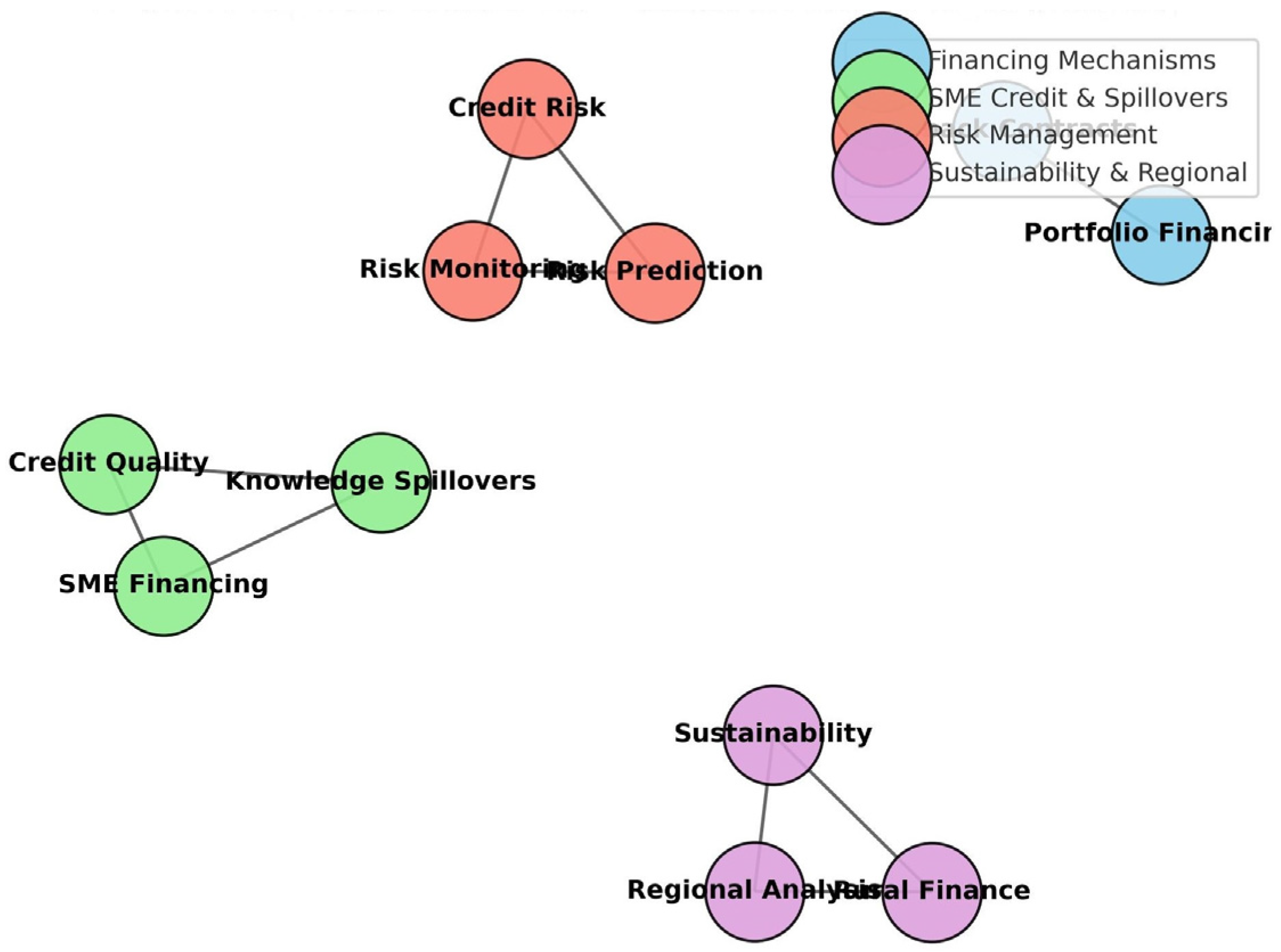

- Financing Mechanisms—research on buyback contracts and portfolio financing that connects operating choices with fiscal measures (J. Shi et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2020).

- (ii)

- SME Credit and Knowledge Spillovers—studies emphasizing the impact on SMEs’ credit quality of inter-organizational networks and knowledge access (Song et al., 2019; B. Liu et al., 2020).

- (iii)

- Risk Management—articles that deal with data-oriented strategies to forecast and manage credit and financing risks (Fayyaz et al., 2021; Ying et al., 2020).

- (iv)

- Regional and Environmental Analysis—research comparing SCF from geographical and environmental considerations, such as rural inefficiencies and interregional differences (Tseng et al., 2021; X. Liu et al., 2020).

- Financing Mechanisms. This body of literature examines how financing contracts and mechanisms can close operational and financial flows. For instance, buyback contracts treat capital-constrained newsvendor issues by coordinating finance and inventory (J. Shi et al., 2020), whereas portfolio financing introduces tax shield impacts in two-echelon supply chains (Dong et al., 2020).

- SME Constraints and Credit Access. A second consistent theme relates to the funding struggles of SMEs and the processes that can make them more credit-worthy. Spillovers of knowledge in supply chains enhance SME credit quality (Song et al., 2019), and power disparities between organizations influence trade credit in developing countries (B. Liu et al., 2020). Recent studies also highlight that SME credit quality is significantly affected by the strength of supply chain networks and information sharing structures (Ali et al., 2019). Regional differences are also essential, as demonstrated in Chinese rural SCF performance research (X. Liu et al., 2020).

- Risk Management. In the face of growing uncertainty in financial flows, some research emphasize predictive and preventive measures. Machine learning-based credit risk predictive models (Fayyaz et al., 2021) and text-mining tools to detect SCF risk determinants (Ying et al., 2020) are among the major contributions to this topic.

- Sustainability and Regional Differences. Another theme focuses on sustainability and regional considerations in SCF. Bibliometric studies illustrate high regional diversity in the adoption of SCF and reveal the importance of sustainable financing indicators in determining supply chain performance (Tseng et al., 2021).

- International Journal of Production Economics (IJPE)—25 articles.

- Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management (JPSM)—12 articles.

- International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management (IJPDLM)—5 articles.

- International Journal of Production Research (IJPR)—5 articles.

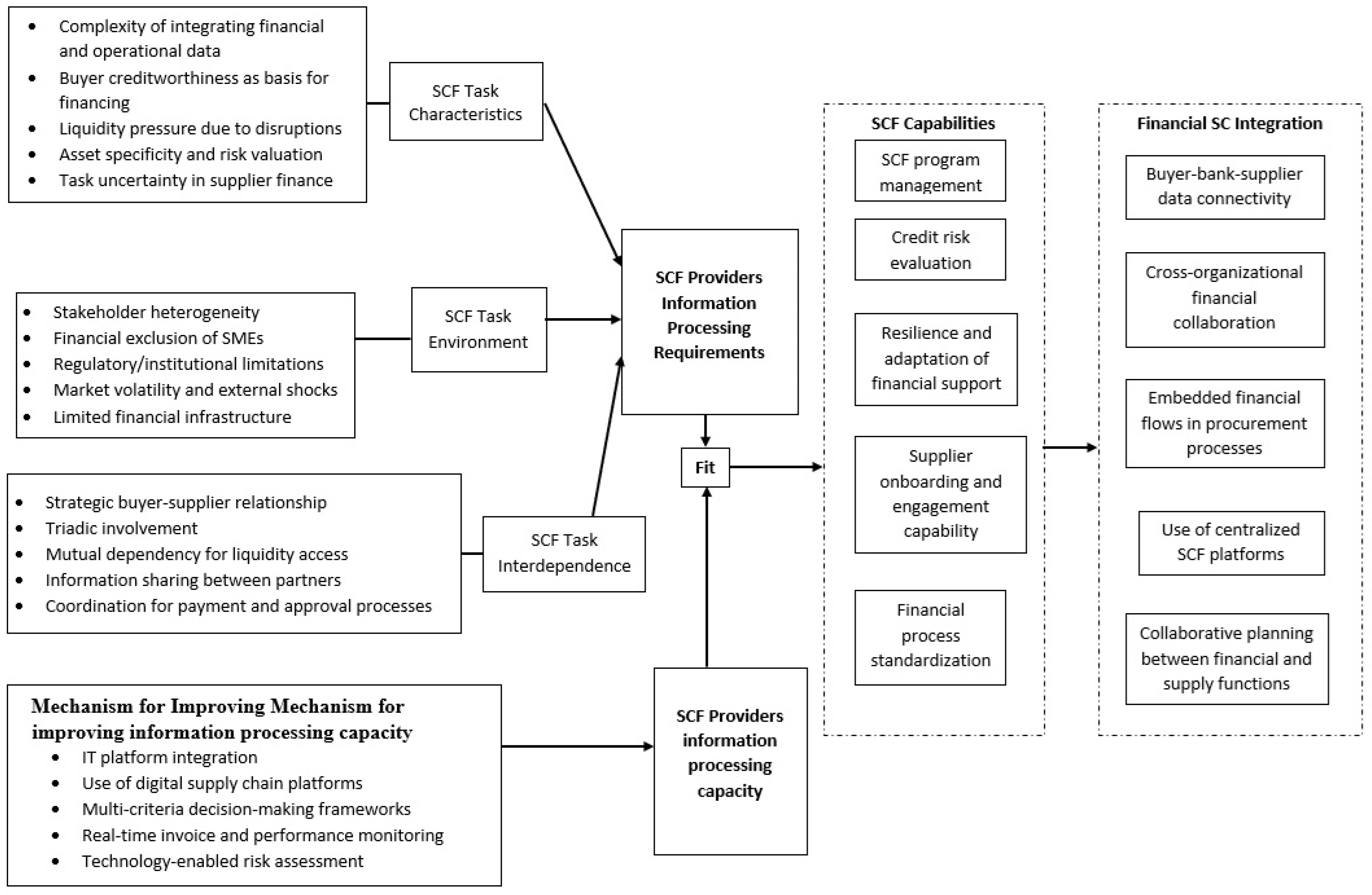

- (1)

- SCF Task Characteristics—the complexity and nature of tasks associated with SCF implementation and execution.

- (2)

- SCF Task Environment—external environmental aspects of uncertainty, regulation, or market volatility.

- (3)

- SCF Task Interdependence—the level of interdependence among SCF players (e.g., buyer, supplier, financier).

- (4)

- Mechanisms for Enhancing Information Processing Capacity—technological, structural, or process-related facilitators used to handle information flows.

- (5)

- SCF Capabilities—organizational competencies that enable effective SCF planning, decision-making, and implementation.

- (6)

- Financial Supply Chain (SC) Integration—the degree to which financial flows are coordinated and synchronized with physical and information flows within the supply chain.

4. Discussion

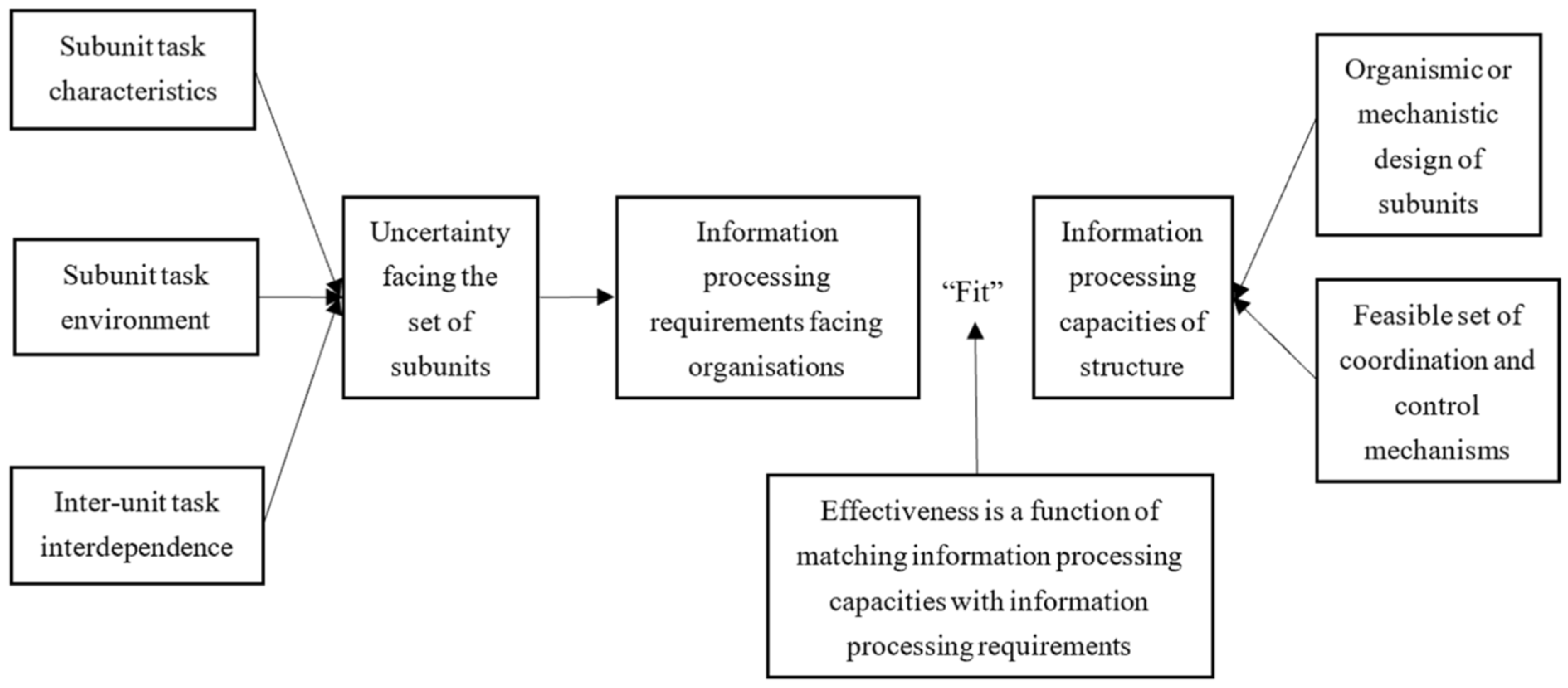

4.1. Derivation of the IPT-SCF Framework

4.2. SCF Providers’ Uncertainties and Requirements for Information Processing

4.2.1. Characteristics of the Task

4.2.2. Task Environment

4.2.3. Task Interdependence

4.3. Mechanisms for Enhancing Information Processing Capacity

4.4. Requirements–Processing Capacity Fit → SCF Capabilities

4.5. SCF Capabilities Facilitating Financial Supply Chain Integration

4.5.1. Mapping Financial Network Structures

4.5.2. Designing Financial Business Processes

4.5.3. Sharing Financial Information Systems

4.6. Methodological Directions for Testing the Framework

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, Z., Gongbing, B., & Mehreen, A. (2019). Supply chain network and information sharing effects of SMEs’ credit quality on firm performance: Do strong tie and bridge tie matter? Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(5), 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, C. (2019). Toward a supply chain finance (SCF) ecosystem—Proposing a framework and agenda for future research. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Chain Management, 25, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P., & Nair, S. K. (2012). Supply chain finance enabled early pay: Unlocking trapped value in B2B logistics. International Journal of Logistics System Management, 12, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2007). Principles of corporate finance (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill International Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, C., Meinlschmidt, J., & Foerstl, K. (2017). Managing information processing needs in global supply chains: A prerequisite to sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 53, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauffour, J.-P., & Malouche, M. (2011). Trade finance during the great trade collapse. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Du, J., He, W., & Siponen, M. (2022). Supply chain finance platform evaluation based on acceptability analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 243, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D. W., Lee, Y. H., Ahn, S. H., & Hwang, M. K. (2012). A framework for measuring the performance of service supply chain management. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 62(3), 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R., & Weick, K. (1984). Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems. Academy of Management Review, 9, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goeij, C., Gelsomino, L. M., Caniato, F., Moretto, A. M., & Steeman, M. (2020). Understanding SME suppliers’ response to supply chain finance: A transaction cost economics perspective. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 51(8), 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Iacono, U., Reindorp, M., & Dellaert, N. (2015). Market adoption of reverse factoring. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(3), 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G., Wei, L., Xie, J., Zhang, W., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Two-echelon supply chain operational strategy under portfolio financing and tax shield. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(4), 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, V. H., de Goeij, C., Gelsomino, L. M., & Woxenius, J. (2020). Supply chain finance is not for everyone. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 50(9–10), 775–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, I., Ar, I. M., Ozdemir, A. I., Medeni, I. T., & Medeni, T. (2021a). Assessing the feasibility of blockchain technology in industries: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(3), 746–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H., Li, G., Sun, H., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2017). An information processing perspective on supply chain risk management: Antecedents, mechanism, and consequences. International Journal of Production Economics, 185, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, M. R., Rasouli, M. R., & Amiri, B. (2021). A data-driven and network-aware approach for credit risk prediction in supply chain finance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(4), 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelsomino, L. M., Mangiaracina, R., Perego, A., & Tumino, A. (2016). Supply chain finance: A literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 46, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomm, M. L. (2010). Supply chain finance: Applying finance theory to supply chain management to enhance finance in supply chains. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 13, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q., Yang, Y., & Wang, S. (2014). Information and decision-making delays in MRP, KANBAN, and CONWIP. International Journal of Production Economics, 156, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C., Wei, J., & Wei, L. (2021a). Co-opetition, supplier capital constraints, and supply chain finance adoption. International Journal of Production Economics, 234, 108041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, M., Moretto, A. M., & Caniato, F. F. A. (2021). How to select a supply chain finance solution? Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 27(4), 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E. (2005). Supply chain finance: Some conceptual insights. Beiträge Zu Beschaffung Und Logistik, 16, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Fan, Z.-P., & Wang, X. (2019). The impact of transportation fee on the performance of capital-constrained supply chain under 3PL financing service. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 130, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X., Zhou, H., & Wang, J. (2021). Joint finance and order decision for supply chain with capital constraint of retailer considering product defect. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 157, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkakos, S. D., & Serrano, A. (2016). Supply chain finance for small and medium sized enterprises: The case of reverse factoring. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 46, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q., & He, J. (2019). Supply chain contract design considering the supplier’s asset structure and capital constraints. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 137, 106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q., & Xiao, Y. (2018). Retailer credit guarantee in a supply chain with capital constraint under push & pull contract. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 125, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Wang, Y., & Shou, Y. (2020). Trade credit in emerging economies: An interorganizational power perspective. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(4), 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zhang, J. Z., He, W., & Li, W. (2021). Mitigating information asymmetry in inventory pledge financing through the Internet of Things and blockchain. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(5), 1429–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Du, Y., Sun, J., Yang, R., & Yang, F. (2020). Performance of China’s rural supply chain finance: From the perspective of maximization of intermediate output. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(5), 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zhou, L., & Wu, Y.-C. J. (2015). Supply chain finance in China: Business innovation and theory development. Sustainability, 7, 14689–14709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q., Gu, J., & Huang, J. (2019). Supply chain finance with partial credit guarantee provided by a third-party or a supplier. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 135, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, A., Grassi, L., Caniato, F., Giorgino, M., & Ronchi, S. (2019). Supply chain finance: From traditional to supply chain credit rating. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., Guo, S., & Chu, J. (2021b). P2P supply chain financing, R&D investment and companies’ innovation efficiency. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(1), 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfohl, H.-C., & Gomm, M. (2009). Supply chain finance: Optimizing financial flows in supply chains. Logistics Research, 1, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza-Gharehbagh, R., Asian, S., Hafezalkotob, A., & Wei, C. (2021a). Reframing supply chain finance in an era of reglobalization: On the value of multi-sided crowdfunding platforms. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 149, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P., Miller, A., & Judge, W. (1999). Using information-processing theory to understand planning/performance relationships in the context of strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H., & Baumann, S. (2014). Managing behavioral risks in logistics-based networks: A project finance approach. IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 11, 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., Du, Q., Lin, F., Fung, R. Y. K., & Lai, K. K. (2020). Coordinating the supply chain finance system with buyback contract: A capital-constrained newsvendor problem. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 146, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Li, X., Chu, C., & Shi, V. (2021). Demand uncertainty and financing decisions in supply chains with capital constraints. Omega, 101, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Lu, Q., Yu, K., & Qian, C. (2019). How do knowledge spillover and access in supply chain network enhance SMEs’ credit quality? Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(2), 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Yu, K., & Lu, Q. (2018). Financial service providers and banks’ role in helping SMEs to access finance. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 48, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templar, S., Cosse, M., Camerinelli, E., & Findlay, C. (2012, September 5–7). An investigation into current supply chain finance practices in business: A case study approach. Logistics Research Network (LRN) Conference, Cranfield, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann, G., Turkulainen, V., Hartmann, E., & Bais, L. (2009). Integration in the global sourcing organization—An information processing perspective. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, A., Forza, C., & Perin, E. (2012). Organisation design strategies for mass customisation: An information-processing-view perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 50, 3860–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M. L., Bui, T. D., Lim, M. K., Tsai, F. M., & Tan, R. R. (2021). Comparing world regional sustainable supply chain finance using big data analytics: A bibliometric analysis. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(3), 657–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M., & Nadler, D. (1978). Information processing as an integrating concept in organizational design. Academy of Management Review, 3, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Yang, X., Zhuo, X., & Xiong, M. (2019). Joint logistics and financial services by a 3PL firm: Effects of risk preference and demand volatility. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 130, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C., Lai, K.-H., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2015). The role of IT-enabled collaborative decision making in inter-organizational information integration to improve customer service performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 159, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, D., Blome, C., Foerstl, K., & Henke, M. (2013a). Managing the innovation adoption of supply chain finance–empirical evidence from six European case studies. Journal of Business Logistics, 34, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, D., Blome, C., & Henke, M. (2013b). Focusing the financial flow of supply chains: An empirical investigation of financial supply chain management. International Journal of Production Economics, 145, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Chen, X., Jia, F., & Brown, S. (2018). Supply chain finance: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 204, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N., & He, X. (2020). Optimal trade credit with deferred payment and multiple decision attributes in supply chain finance. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 147, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H., Chen, L., & Zhao, X. (2020). Application of text mining in identifying the factors of supply chain financing risk management. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(4), 894–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Song, H., & Wu, Y. (2022). Digital finance, supply chain finance, and resilience in supply networks. International Review of Economics & Finance, 79, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year | Focus of Review | Theoretical Foundation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al. (2012) | Service supply chain performance measurement | Fuzzy-AHP framework | Financial aspects covered superficially; not SCF-specific |

| X. Liu et al. (2015) | Overview of SCF mechanisms and adoption | Non-explicit | Descriptive, lacks integrative framework |

| Gelsomino et al. (2016) | SCF solutions, adoption drivers, barriers | Transaction Cost Economics | Limited scope, does not integrate operational and financial flows |

| Xu et al. (2018) | SCF models in inventory/finance | Optimization models | Focused on operational modeling; fragmented without theoretical unification |

| Tseng et al. (2021) | Sustainable SCF through bibliometric analysis | Bibliometrics | Sustainability-specific, does not engage with broader SCF integration |

| SCF Component | Important Parameter | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SCF Task Characteristics | Complexity of integrating financial and operational data | Moretto et al. (2019); Xu et al. (2018) |

| Buyer creditworthiness as basis for financing | Lekkakos and Serrano (2016); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Liquidity pressure due to disruptions | Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Asset specificity and risk valuation | Xu et al. (2018); Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Task uncertainty in supplier finance | Wuttke et al. (2013a) | |

| SCF Task Environment | Stakeholder heterogeneity | Moretto et al. (2019) |

| Financial exclusion of SMEs | Lekkakos and Serrano (2016); Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Regulatory/institutional limitations | Song et al. (2018); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Market volatility and external shocks | Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Limited financial infrastructure | Gelsomino et al. (2016); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| SCF Task Interdependence | Strategic buyer–supplier relationship | Moretto et al. (2019); Lekkakos and Serrano (2016) |

| Triadic involvement (buyer–supplier–financier) | Gelsomino et al. (2016); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Mutual dependency for liquidity access | Wuttke et al. (2013a); Lekkakos and Serrano (2016) | |

| Information sharing between partners | Moretto et al. (2019); Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Coordination for payment and approval processes | Lekkakos and Serrano (2016); Wuttke et al. (2013a) | |

| Mechanisms for Improving Information Processing Capacity | IT platform integration | Gelsomino et al. (2016); Xu et al. (2018) |

| Use of digital supply chain platforms | Wuttke et al. (2013a); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Multi-criteria decision-making frameworks | Guida et al. (2021) | |

| Real-time invoice and performance monitoring | Gelsomino et al. (2016); Wuttke et al. (2013a) | |

| Technology-enabled risk assessment | Xu et al. (2018) | |

| SCF Capabilities | SCF program management capability | Moretto et al. (2019) |

| Credit risk evaluation using operational data | Xu et al. (2018); Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Resilience and adaptation of financial support | Wuttke et al. (2013a) | |

| Supplier onboarding and engagement capability | Lekkakos and Serrano (2016); Moretto et al. (2019) | |

| Financial process standardization | Gelsomino et al. (2016); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Financial SC Integration | Buyer–bank–supplier data connectivity | Lekkakos and Serrano (2016); Gelsomino et al. (2016) |

| Cross-organizational financial collaboration | Moretto et al. (2019) | |

| Embedded financial flows in procurement processes | Xu et al. (2018); Gelsomino et al. (2016) | |

| Use of centralized SCF platforms | Wuttke et al. (2013a); Xu et al. (2018) | |

| Collaborative planning between financial and supply functions | Moretto et al. (2019); Guida et al. (2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Divya, D.; Abraham, R.; Bhimavarapu, V.M.; Arunkumar, O.N. Bridging Financial and Operational Gaps in Supply Chain Finance: An Information Processing Theory Perspective. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090479

Divya D, Abraham R, Bhimavarapu VM, Arunkumar ON. Bridging Financial and Operational Gaps in Supply Chain Finance: An Information Processing Theory Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090479

Chicago/Turabian StyleDivya, D., Rebecca Abraham, Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu, and O. N. Arunkumar. 2025. "Bridging Financial and Operational Gaps in Supply Chain Finance: An Information Processing Theory Perspective" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090479

APA StyleDivya, D., Abraham, R., Bhimavarapu, V. M., & Arunkumar, O. N. (2025). Bridging Financial and Operational Gaps in Supply Chain Finance: An Information Processing Theory Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090479