Effects of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions on Glycemic Control in U.S. Hispanic Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

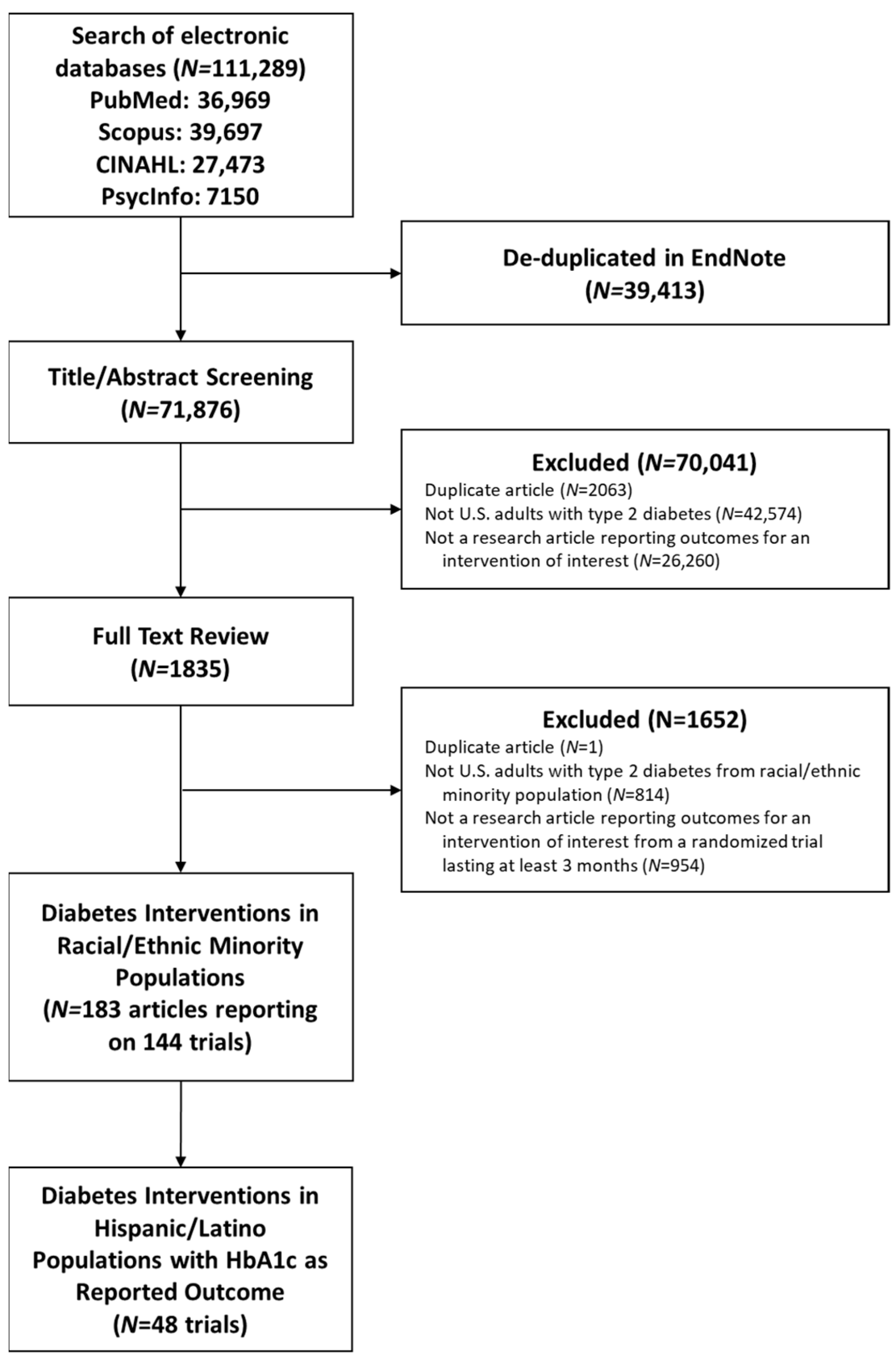

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Review

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguayo-Mazzucato, C.; Diaque, P.; Hernandez, S.; Rosas, S.; Kostic, A.; Caballero, A.E. Understanding the growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic population living in the United States. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2019, 35, e3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Minority Health. Hispanic/Latino Health. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/hispaniclatino-health (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Office of Minority Health. Diabetes and Hispanic Americans. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/diabetes-and-hispanic-americans (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Lopez, J.M.S.; Bailey, R.A.; Rupnow, M.F.T. Demographic Disparities Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in 2011: Diabetes Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Hypoglycemia Events. Popul. Health Manag. 2015, 18, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Gujral, U.P.; Quarells, R.C.; Rhodes, E.C.; Shah, M.K.; Obi, J.; Lee, W.-H.; Shamambo, L.; Weber, M.B.; Narayan, K.M.V. Disparities in diabetes prevalence and management by race and ethnicity in the USA: Defining a path forward. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, S.; Swan, M.; Smaldone, A. Does diabetes self-management education in conjunction with primary care improve glycemic control in Hispanic patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2015, 41, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.A.; Billimek, J.; Lee, J.-A.; Sorkin, D.H.; Olshansky, E.F.; Clancy, S.L.; Evangelista, L.S. Effect of diabetes self-management education on glycemic control in Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, E.; Chan, V.W.-S.; Manuel, L.; Sidani, S. A systematic literature review of diabetes self-management education features to improve diabetes education in women of Black African/Caribbean and Hispanic/Latin American ethnicity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 92, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkisian, C.A.; Brown, A.F.; Norris, K.C.; Wintz, R.L.; Mangione, C.M. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American, or Latino adults. Diabetes Educ. 2003, 29, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.; O’Connell, S.S.; Thomas, C.; Chimmanamada, R. Telehealth Interventions to Improve Diabetes Management Among Black and Hispanic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparit. 2022, 9, 2375–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIMHD Research Framework Details. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/nimhd-research-framework (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Falk, E.M.; Staab, E.M.; Deckard, A.N.; Uranga, S.I.; Thomas, N.C.; Wan, W.; Karter, A.J.; Huang, E.S.; Peek, M.E.; Laiteerapong, N. Effectiveness of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions to Improve Glycemic Control in U.S. Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, R.; Sander, G.; Timothy, L. Modern Epidemiology; R2 Digital Library; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2008; Available online: https://www.r2library.com/Resource/Title/0781755646 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Aponte, J.; Jackson, T.D.; Wyka, K.; Ikechi, C. Health effectiveness of community health workers as a diabetes self-management intervention. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2017, 14, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, C.; Layne, J.E.; Munoz-Orians, L.; Gordon, P.L.; Walsmith, J.; Foldvari, M.; Roubenoff, R.; Tucker, K.L.; Nelson, M.E. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamany, S.; Walker, E.A.; Schechter, C.B.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Davis, N.J.; Ortega, F.M.; Carrasco, J.; Basch, C.E.; Silver, L.D. Telephone Intervention to Improve Diabetes Control: A Randomized Trial in the New York City A1c Registry. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosch, D.L.; Uy, V.; Ochoa, S.; Mangione, C.M. Evaluation of a behavior support intervention for patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieft, A.E.; Llabre, M.M.; McCalla, J.R.; Gutt, M.; Mendez, A.J.; Gellman, M.D.; Goldberg, R.B.; Schneiderman, N. Effects of a Multicomponent Life-Style Intervention on Weight, Glycemic Control, Depressive Symptoms, and Renal Function in Low-Income, Minority Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Results of the Community Approach to Lifestyle Modification for Diabetes Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, P.H.; Larme, A.C.; Meyer, J.; Marsh, G.; Correa, A.; Pugh, J.A. Patient choice in diabetes education curriculum. Nutritional versus standard content for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmas, W.; Findley, S.E.; Mejia, M.; Batista, M.; Teresi, J.; Kong, J.; Silver, S.; Fleck, E.M.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Carrasquillo, O. Results of the northern Manhattan diabetes community outreach project: A randomized trial studying a community health worker intervention to improve diabetes care in Hispanic adults. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, T.; Steers, W.N.; Wenger, N.S.; Duru, O.K.; Mangione, C.M. Effect of a community-based diabetes self-management empowerment program on mental health-related quality of life: A causal mediation analysis from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasquillo, O.; Lebron, C.; Alonzo, Y.; Li, H.; Chang, A.; Kenya, S. Effect of a Community Health Worker Intervention Among Latinos with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: The Miami Healthy Heart Initiative Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón, A.M.; Calderón, J.L.; Perez, A.; Millar, C.; McLaughlin-Middlekauff, J.; Sangasubana, N.; Alvarez, G.; Arce, L.; Hardigan, P.; Rabionet, S.E. A community-based pilot study of a diabetes pharmacist intervention in Latinos: Impact on weight and hemoglobin A1c. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortmann, A.L.; Gallo, L.C.; Garcia, M.I.; Taleb, M.; Euyoque, J.A.; Clark, T.; Skidmore, J.; Ruiz, M.; Dharkar-Surber, S.; Schultz, J.; et al. Dulce Digital: An mHealth SMS-Based Intervention Improves Glycemic Control in Hispanics with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, B.S.; Brodsky, I.G.; Lawless, K.A.; Smolin, L.I.; Arozullah, A.M.; Smith, E.V.; Berbaum, M.L.; Heckerling, P.S.; Eiser, A.R. Implementation and evaluation of a low-literacy diabetes education computer multimedia application. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisler, M.; Choi, H.; Palmisano, G.; Mase, R.; Richardson, C.; Fagerlin, A.; Montori, V.M.; Spencer, M.; An, L.C. Comparison of community health worker-led diabetes medication decision-making support for low-income Latino and African American adults with diabetes using e-health tools versus print materials: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161 (Suppl. 10), S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, R.; Stoddard, P.J.; Gonzales, E.N.; Villagran-Flores, M.; Thomson, J.; Bayard, P.; Palos Lucio, A.G.; Schillinger, D.; Bertozzi, S.; Gonzales, R. An automated telephone nutrition support system for Spanish-speaking patients with diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2014, 8, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujan, J.; Ostwald, S.K.; Ortiz, M. Promotora diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2007, 33, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Amico, K.R.; Cruz, N.; O’Connell, A.A.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Kalichman, S.C.; Wolf, S.A.; Fisher, J.D. A brief culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2010, 37, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezio, E.A.; Cheng, D.; Balasubramanian, B.A.; Shuval, K.; Kendzor, D.E.; Culica, D. Community Diabetes Education (CoDE) for uninsured Mexican Americans: A randomized controlled trial of a culturally tailored diabetes education and management program led by a community health worker. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 100, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, M.C.; Ockene, I.S.; Restrepo, A.; White, M.J.; Borg, A.; Olendzki, B.; Scavron, J.; Candib, L.; Welch, G.; Reed, G. Randomized trial of a literacy-sensitive, culturally tailored diabetes self-management intervention for low-income latinos: Latinos en control. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, S.K.; Martin, M.A.; Swider, S.M.; Tumialán Lynas, C.M.; Janssen, I.; Avery, E.F.; Powell, L.H. Mexican American trial of community health workers: A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixta, C.S.; Ostwald, S. Texas-Mexico border intervention by promotores for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008, 34, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.A.; Bermudez-Millan, A.; Damio, G.; Segura-Perez, S.; Chhabra, J.; Vergara, C.; Feinn, R.; Perez-Escamilla, R. A randomized, controlled trial of a stress management intervention for Latinos with type 2 diabetes delivered by community health workers: Outcomes for psychological wellbeing, glycemic control, and cortisol. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 120, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ayala, G.X.; Ibarra, L.; Cherrington, A.L.; Parada, H.; Horton, L.; Ji, M.; Elder, J.P. Puentes hacia una mejor vida (Bridges to a Better Life): Outcome of a Diabetes Control Peer Support Intervention. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13 (Suppl. 1), S9–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burner, E.; Lam, C.N.; DeRoss, R.; Kagawa-Singer, M.; Menchine, M.; Arora, S. Using Mobile Health to Improve Social Support for Low-Income Latino Patients with Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of the Feasibility Trial of TExT-MED + FANS. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2018, 20, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Villa, F.; Piette, J.D. Spanish diabetes self-management with and without automated telephone reinforcement: Two randomized trials. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Garcia, A.A.; Kouzekanani, K.; Hanis, C.L. Culturally competent diabetes self-management education for Mexican Americans: The Starr County border health initiative. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.A.; Blozis, S.A.; Kouzekanani, K.; Garcia, A.A.; Winchell, M.; Hanis, C.L. Dosage effects of diabetes self-management education for Mexican Americans: The Starr County Border Health Initiative. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; García, A.A.; Winter, M.; Silva, L.; Brown, A.; Hanis, C.L. Integrating education, group support, and case management for diabetic Hispanics. Ethn. Dis. 2011, 21, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McEwen, M.M.; Pasvogel, A.; Murdaugh, C.; Hepworth, J. Effects of a Family-based Diabetes Intervention on Behavioral and Biological Outcomes for Mexican American Adults. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philis-Tsimikas, A.; Fortmann, A.; Lleva-Ocana, L.; Walker, C.; Gallo, L.C. Peer-led diabetes education programs in high-risk Mexican Americans improve glycemic control compared with standard approaches: A Project Dulce promotora randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramal, E.; Champlin, A.; Bahjri, K. Impact of a Plant-Based Diet and Support on Mitigating Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Latinos Living in Medically Underserved Areas. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, M.C.; Olendzki, B.; Reed, G.W.; Gumieniak, O.; Scavron, J.; Ockene, I. Diabetes self-management among low-income Spanish-speaking patients: A pilot study. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2005, 29, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.S.; Kieffer, E.C.; Sinco, B.; Piatt, G.; Palmisano, G.; Hawkins, J.; Lebron, A.; Espitia, N.; Tang, T.; Funnell, M.; et al. Outcomes at 18 Months From a Community Health Worker and Peer Leader Diabetes Self-Management Program for Latino Adults. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobert, D.J.; Strycker, L.A.; King, D.K.; Barrera, M.; Osuna, D.; Glasgow, R.E. Long-term outcomes from a multiple-risk-factor diabetes trial for Latinas: ¡Viva Bien! Transl. Behav. Med. 2011, 1, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, D.; Pasvogel, A.; Barrera, L. A feasibility study of a culturally tailored diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2007, 9, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.D.; Fletcher, J.; Sigal, I.; Giftos, J.; Schechter, C.; Walker, E.A. A collaborative approach to control hypertension in diabetes: Outcomes of a pilot intervention. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2011, 2, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, R.S.; Teresi, J.A.; Goland, R.; Izquierdo, R.; Palmas, W.; Eimicke, J.P.; Ebner, S.; Shea, S.; IDEATel Consortium. Glycemic control and health disparities in older ethnically diverse underserved adults with diabetes: Five-year results from the Informatics for Diabetes Education and Telemedicine (IDEATel) study. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.R.; Christison-Lagay, J.; Villagra, V.; Liu, H.; Dziura, J. Managing the space between visits: A randomized trial of disease management for diabetes in a community health center. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babamoto, K.S.; Sey, K.A.; Camilleri, A.J.; Karlan, V.J.; Catalasan, J.; Morisky, D.E. Improving diabetes care and health measures among hispanics using community health workers: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2009, 36, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Damio, G.; Chhabra, J.; Fernandez, M.L.; Segura-Pérez, S.; Vega-López, S.; Kollannor-Samuel, G.; Calle, M.; Shebl, F.M.; D’Agostino, D. Impact of a community health workers-led structured program on blood glucose control among latinos with type 2 diabetes: The DIALBEST trial. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, L.; Riley, B.B.; Hernandez, R.; Quinn, L.T.; Gerber, B.S.; Castillo, A.; Day, J.; Ingram, D.; Wang, Y.; Butler, P. Medical assistant coaching to support diabetes self-care among low-income racial/ethnic minority populations: Randomized controlled trial. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 36, 1052–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.; Allen, N.A.; Zagarins, S.E.; Stamp, K.D.; Bursell, S.-E.; Kedziora, R.J. Comprehensive diabetes management program for poorly controlled Hispanic type 2 patients at a community health center. Diabetes Educ. 2011, 37, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.; Zagarins, S.E.; Santiago-Kelly, P.; Rodriguez, Z.; Bursell, S.-E.; Rosal, M.C.; Gabbay, R.A. An internet-based diabetes management platform improves team care and outcomes in an urban Latino population. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.A.; Benitez, A.; Locklin, C.A.; Gao, Y.; Lee, S.M.; Quinn, M.T.; Solomon, M.C.; Sánchez-Johnsen, L.; Burnet, D.L.; Chin, M.H. Little Village Community Advisory Board. Picture Good Health: A Church-Based Self-Management Intervention Among Latino Adults with Diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.A.; Brown, S.A.; Horner, S.D.; Zuñiga, J.; Arheart, K.L. Home-based diabetes symptom self-management education for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, N.; Moynihan, V.; Nilo, A.; Singer, K.; Bernik, L.S.; Etiebet, M.-A.; Fang, Y.; Cho, J.; Natarajan, S. The Mobile Insulin Titration Intervention (MITI) for Insulin Adjustment in an Urban, Low-Income Population: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, J.G.; Bessesen, D.H.; Byers, T.E.; Christian, K.K.; Goldstein, M.G.; Bock, B.C. Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ell, K.; Katon, W.; Xie, B.; Lee, P.-J.; Kapetanovic, S.; Guterman, J.; Chou, C.-P. One-year postcollaborative depression care trial outcomes among predominantly Hispanic diabetes safety net patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Smith, M.; Rosenmoss, S.; Marshall, M.B.; Waxman, E. Comprehensive Diabetes Self-Management Support From Food Banks: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, B.; Arellano, L.M.; Velásquez, R. (Eds.) The Handbook of Chicana/o Psychology and Mental Health; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuman, A.N.; Scholl, J.C.; Wilkinson, K. Rural Hispanic Populations at Risk in Developing Diabetes: Sociocultural and Familial Challenges in Promoting a Healthy Diet. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Amirehsani, K.A.; Wallace, D.C.; McCoy, T.P.; Silva, Z. A Family-Based, Culturally-Tailored Diabetes Intervention for Hispanics and Their Family Members. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.N.; Steinbach, J.; Nelson, A.; Shih, W.; D’Avila, M.; Castilla, S.; Jordan, M.; McCarthy, W.J.; Hayes-Bautista, D.; Flores, H. Incorporating an Increase in Plant-Based Food Choices into a Model of Culturally Responsive Care for Hispanic/Latino Children and Adults Who Are Overweight/Obese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Lyles, C.; Marshall, M.B.; Prendergast, K.; Smith, M.C.; Headings, A.; Bradshaw, G.; Rosenmoss, S.; Waxman, E. A Pilot Food Bank Intervention Featuring Diabetes-Appropriate Food Improved Glycemic Control Among Clients In Three States. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canedo, J.R.; Miller, S.T.; Schlundt, D.; Fadden, M.K.; Sanderson, M. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Diabetes Quality of Care: The Role of Healthcare Access and Socioeconomic Status. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparit. 2018, 5, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainous, A.G.; Diaz, V.A.; Koopman, R.J.; Everett, C.J. Quality of care for Hispanic adults with diabetes. Fam. Med. 2007, 39, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Location | Enrolled in Trial/Screened for Eligibility, N | Follow-Up, Months | Control Arm | Intervention Arm | Level | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual/Behavioral | |||||||

| Aponte 2017, [16] | South Bronx, NY, USA | 180/236 | 6 | Usual care | Diabetes education including group sessions, home visits, and phone calls, delivered by a CHW | individual | behavioral |

| Castaneda 2002, [17] | Boston, MA, USA | 62/100 | 4 | Usual care | Supervised high-intensity progressive resistance training | individual | behavioral |

| Chamany 2015, [18] | South Bronx, NY, USA | 941/9389 | 12 | Printed self-management educational materials | Educational materials plus self-management support provided via phone by diabetes educators | individual | behavioral |

| Frosch 2011, [19] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | 201/2438 | 6 | Printed self-management educational materials | Self-management education video with a workbook and telephone coaching by a diabetes nurse educator | individual | behavioral |

| Moncrieft 2016, [20] | Miami, FL, USA | 111/340 | 6 | Usual care | Lifestyle intervention plus cognitive behavioral and social learning approaches to address depressive symptoms with individual and group sessions led by therapists | individual | behavioral |

| Noël 1998, [21] | Southwest TX, USA | 596/NR | 6 | Assigned to either standard diabetes education curriculum or a nutritional focused program | Given the choice between standard diabetes education curriculum or nutrition focused program | individual | behavioral |

| Palmas 2014, [22] | New York, NY, USA | 360/836 | 12 | Usual care, educational materials, and quarterly phone calls | Diabetes education including group sessions, home visits, and phone calls, delivered by a CHW | individual | behavioral |

| Sugiyama 2015, [23] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | 516/NR | 6 | Lectures on unrelated geriatrics topic | Group diabetes self-care sessions led by health educator | individual | behavioral |

| Individual/Behavioral + Sociocultural | |||||||

| Carrasquillo 2017, [24] | Miami-Dade County, FL, USA | 300/863 | 12 | Usual care and mailed diabetes education materials | Home visits, phone calls, coaching, patient navigation, culturally relevant education, and group exercise sessions, delivered by CHW | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Castejón 2013, [25] | Broward County, FL, USA | 84/NR | 3 | Usual care | Culturally tailored pharmacist counseling on medication, nutrition, exercise, and self-care | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Fortmann 2017, [26] | San Diego and Riverside Counties, CA, USA | 126/825 | 6 | Usual care | Culturally tailored text messaging program providing education, motivation, and support | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Gerber 2005, [27] | Chicago, IL, USA | 244/313 | 12 | Multiple-choice diabetes quizzes delivered via computer kiosk in clinic waiting room | Diabetes education program delivered via computer kiosk in clinic waiting room, including culturally tailored lessons and patient testimonials | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Heisler 2014, [28] | Detroit, MI, USA | 188/391 | 3 | Educational materials reviewed with CHW | Community-informed, personally tailored, interactive computerized diabetes medication decision aid reviewed with CHW | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Khanna 2014, [29] | Oakland, CA, USA | 75/78 | 3 | Waitlist | Automated, interactive phone calls providing culture-concordant education and feedback on diet | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Lujan 2007, [30] | Southwest TX, USA | 150/160 | 6 | Usual care | Culturally specific group classes led by promotoras and telephone follow-up | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Osborn 2010, [31] | CT, USA | 118/NR | 3 | Usual care | Brief, culturally tailored self-management intervention delivered by medical assistant | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Prezio 2013, [32] | Dallas, TX, USA | 180/1800 | 12 | Waitlist | Culturally adapted diabetes management and education program led by CHW | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Rosal 2011, [33] | MA, USA | 252/1176 | 4 | Usual care | Culturally tailored diabetes self-management program led by health educator, nutritionist, and/or lay leader | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Rothschild 2014, [34] | Chicago, IL, USA | 144/NR | 12 | Usual care and mailed education materials | Culturally appropriate self-management education delivered via CHW home visits | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Sixta 2008, [35] | Webb County, TX, USA | 131/761 | 6 | Waitlist | Promotores-led culturally sensitive diabetes self-management course | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Wagner 2016, [36] | Hartford, CT, USA | 107/NR | 3 | Single group diabetes education session | Culturally sensitive, manualized group sessions led by CHW focused on relaxation techniques, stress management, and psychoeducation | individual | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral | |||||||

| Ayala 2015, [37] | Imperial County, CA, USA | 336/1202 | 6 | Usual care | Peer support intervention | individual, interpersonal | behavioral |

| Burner 2018, [38] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | 44/745 | 3 | Text message education program | Text message education program for both individual with diabetes and a designated support person | individual, interpersonal | behavioral |

| Lorig 2008, [39] | San Francisco Bay Area, CA, USA | 533/765 | 6 | Peer-led self-management program | Peer-led self-management program plus automated telephone reinforcement | individual, interpersonal | behavioral |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Sociocultural | |||||||

| Brown 2002, [40] | Starr County, TX, USA | 256/NR | 6 | Waitlist | Culturally tailored diabetes self-management education and group support sessions led by nurses, dietitians, and CHWs | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Brown 2005, [41] | Starr County, TX, USA | 216/NR | 3 | Compressed version of diabetes self-management education and support | Extended version of diabetes self-management education and support program | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Brown 2011, [42] | Starr County, TX, USA | 83/NR | 6 | Diabetes self-management education and support | Diabetes self-management education and support plus nurse case management | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| McEwen 2017, [43] | AZ, USA | 157/929 | 3 | Waitlist | Family-based, culturally tailored education and social support group sessions, home visits, and telephone calls delivered by nurse educator and promotora | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Philis-Tsimikas 2011, [44] | San Diego, CA, USA | 207/310 | 4 | Usual care | Culturally tailored education program utilizing trained peer-educators or promotoras | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Ramal 2018, [45] | San Bernardino County, CA, USA | 38/68 | 6 | Diabetes self-management education | Diabetes self-management education plus group support | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Rosal 2005, [46] | Springfield, MA, USA | 25/NR | 6 | Usual care | Culturally specific and literacy sensitive group diabetes education led by nurse, nutritionist, and assistant | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Spencer 2018, [47] | Detroit, MI, USA | 222/1049 | 6 | Usual care | Culturally tailored diabetes self-management education, home visits, group sessions, and phone calls, delivered by CHW | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Toobert 2011, [48] | Denver, CO, USA | 280/7945 | 6 | Usual care | Culturally adapted group lifestyle intervention targeting multiple health behaviors | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Vincent 2007, [49] | Tucson, AZ, USA | 20/60 | 3 | Usual care | Culturally tailored self-management education and support led by promotoras | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Health Care System | |||||||

| McKee 2011, [50] | Bronx, NY, USA | 55/1268 | 6 | Usual care | Health behavior counseling by home health nurses and telemetry unit for home blood pressure and glucose measurements transmitted to primary care clinicians | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, health care system |

| Weinstock 2011, [51] | New York, NY, USA; Syracuse, NY, USA | 1665/NR | 12 | Usual care | Home telemedicine unit to videoconference with a diabetes educator for self-management education, review of home blood glucose and blood pressure measurements, and goal setting | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, health care system |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Sociocultural + Health Care System | |||||||

| Anderson 2010, [52] | Middletown, CT, USA | 295/1754 | 6 | Usual care | Case management via telephone calls delivered by nurses in addition to mailed low literacy educational materials | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Babamoto 2009, [53] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | 318/1352 | 6 | Usual care | Culturally sensitive diabetes self-management education delivered by CHWs via individual sessions and phone calls | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Pérez-Escamilla 2015, [54] | Hartford, CT, USA | 211/NR | 6 | Usual care | Counseling and culturally adapted diabetes education led by CHW | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Ruggiero 2014, [55] | Chicago, IL, USA | 270/888 | 6 | Culturally sensitive educational booklet | Culturally sensitive self-care coaching by medical assistants in clinic and over the phone | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Welch 2011, [56] | Springfield, MA, USA | 46/67 | 12 | Diabetes education materials reviewed with clinic support staff | One-on-one education sessions with diabetes nurse or dietitian using clinical decision support dashboard | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Welch 2015, [57] | Western MA, USA | 399/868 | 6 | Usual care | One-on-one education sessions with diabetes nurse or dietitian using clinical decision support dashboard | individual, interpersonal | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Individual + Interpersonal + Community/Behavioral + Sociocultural + Health Care System | |||||||

| Baig 2015, [58] | Chicago, IL, USA | 100/211 | 6 | One-time lecture | Culturally sensitive church-based self-management group education delivered by trained lay leader | individual, interpersonal, community | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| García 2015, [59] | Central TX, USA | 72/NR | 6 | Waitlist | Diabetes self-management education via culturally tailored home sessions by nurse | individual, interpersonal, community | behavioral, sociocultural, health care system |

| Other Level/Domain Combinations | |||||||

| Levy 2015, [60] | New York, NY, USA | 61/132 | 3 | Usual care | Text message reminders to measure fasting blood glucose with results monitored by nurse and used for insulin titration | interpersonal | health care system |

| Christian 2008, [61] | Denver, CO, USA; Pueblo, CO, USA | 310/322 | 12 | Usual care and education materials | Computer-based assessment of diet and physical activity habits and readiness to change with tailored feedback report for patient and physician to use with motivational interviewing | individual | behavioral, health care system |

| Ell 2011, [62] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | 387/1803 | 12 | Usual care and depression educational pamphlets for patient and family | Socioculturally adapted collaborative care for depression and diabetes including psychotherapy and/or antidepressants, plus telephone symptom monitoring and relapse prevention | individual, interpersonal | sociocultural, health care system |

| Seligman 2018, [63] | Detroit, MI, USA; Houston, TX, USA; Oakland, CA, USA | 568/5329 | 6 | Waitlist | Diabetes self-management classes, individual check-ins with educator, and food delivery via food bank | individual, community | behavioral, physical |

| Trials | Total N | HbA1c Weighted Mean Difference (95% Cl) | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All trials | 48 | 9185 | −0.32 (−0.44 to −0.20) | 68% |

| >50% participants prefer Spanish | 35 | 5888 | −0.34 (−0.47 to −0.21) | 51% |

| Single-level | 23 | 4627 | −0.25 (−0.40 to −0.10) | 50% |

| Single-domain | 12 | 3197 | −0.32 (−0.46 to −0.18) | 0% |

| Single-level and single-domain | 9 | 2534 | −0.34 (−0.51 to −0.17) | 0% |

| Multi-level | 25 | 4558 | −0.39 (−0.57 to −0.21) | 73% |

| Multi-domain | 36 | 5988 | −0.31 (−0.46 to −0.16) | 74% |

| Multi-level and multi-domain | 22 | 3895 | −0.41 (−0.61 to −0.21) | 74% |

| Intervention level/domain combinations * | ||||

| Individual/Behavioral | 8 | 2492 | −0.33 (−0.50 to −0.16) | 0% |

| Individual/Behavioral + Sociocultural | 13 | 1820 | −0.24 (−0.46 to −0.01) | 59% |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral | 3 | 663 | −0.26 (−0.55 to 0.03) | 13% |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Sociocultural | 10 | 1311 | −0.54 (−0.89 to −0.19) | 75% |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Health Care | 2 | 633 | −0.34 (−0.56 to −0.12) | 0% |

| Individual + Interpersonal/Behavioral + Sociocultural + Health Care | 6 | 1111 | −0.46 (−0.85 to −0.08) | 68% |

| Individual + Interpersonal + Community/Behavioral + Sociocultural + Health Care | 2 | 136 | −0.39 (−0.95 to 0.18) | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bianco, L.; Uranga, S.I.; Rodriguez, A.W.; Shetty, R.; Staab, E.M.; Franco-Galicia, M.I.; Deckard, A.N.; Thomas, N.C.; Wan, W.; Alexander, J.T.; et al. Effects of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions on Glycemic Control in U.S. Hispanic Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091345

Bianco L, Uranga SI, Rodriguez AW, Shetty R, Staab EM, Franco-Galicia MI, Deckard AN, Thomas NC, Wan W, Alexander JT, et al. Effects of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions on Glycemic Control in U.S. Hispanic Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091345

Chicago/Turabian StyleBianco, Laura, Sofía I. Uranga, Alexander W. Rodriguez, Raj Shetty, Erin M. Staab, Melissa I. Franco-Galicia, Amber N. Deckard, Nikita C. Thomas, Wen Wan, Jason T. Alexander, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions on Glycemic Control in U.S. Hispanic Populations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091345

APA StyleBianco, L., Uranga, S. I., Rodriguez, A. W., Shetty, R., Staab, E. M., Franco-Galicia, M. I., Deckard, A. N., Thomas, N. C., Wan, W., Alexander, J. T., Baig, A. A., & Laiteerapong, N. (2025). Effects of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions on Glycemic Control in U.S. Hispanic Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091345