Beyond Isolation: Social Media as a Bridge to Well-Being in Old Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

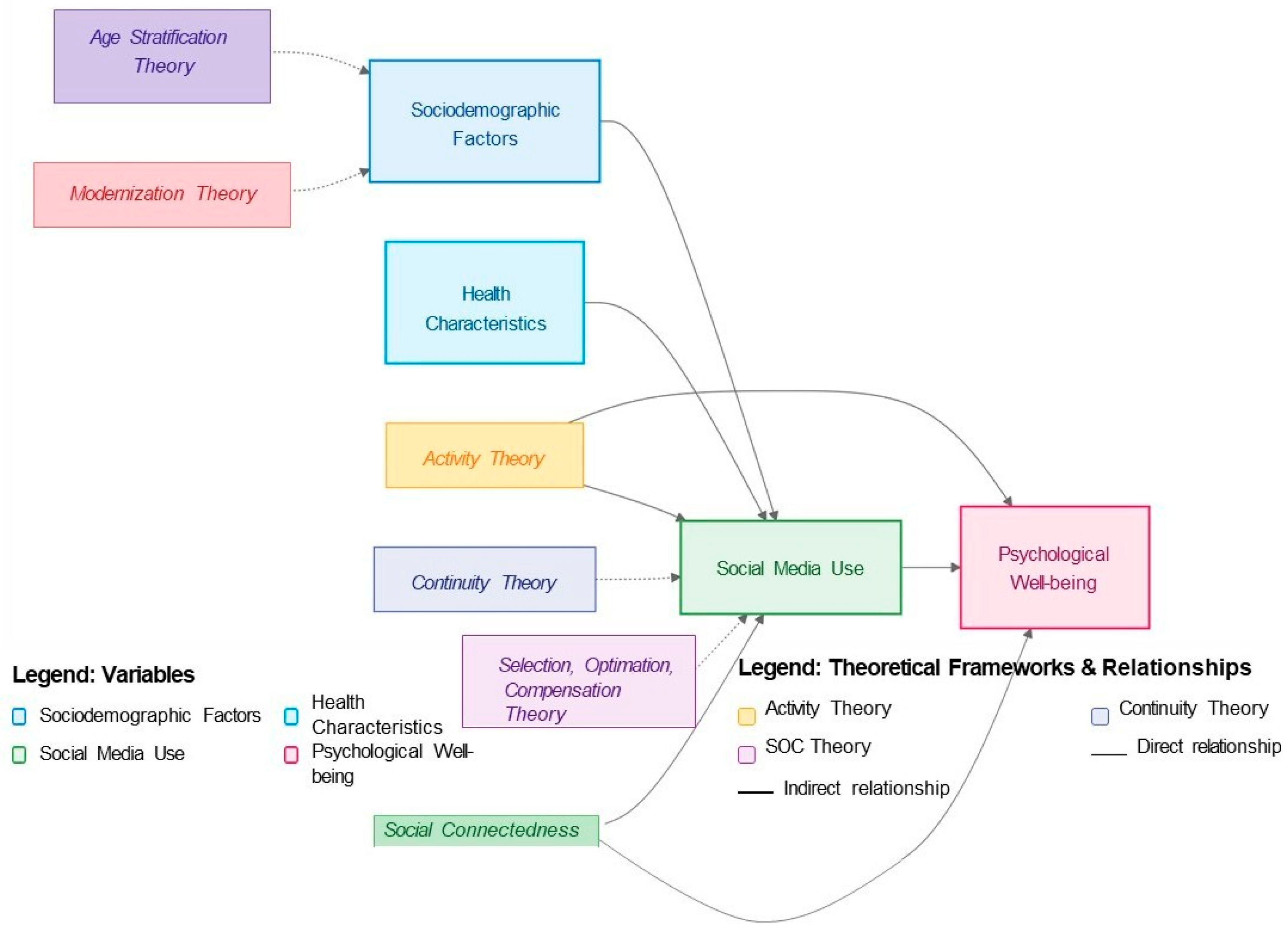

- Identify the main social media used by Brazilian older adults and their usage patterns;

- Analyze the relationship between sociodemographic and health characteristics with social media use;

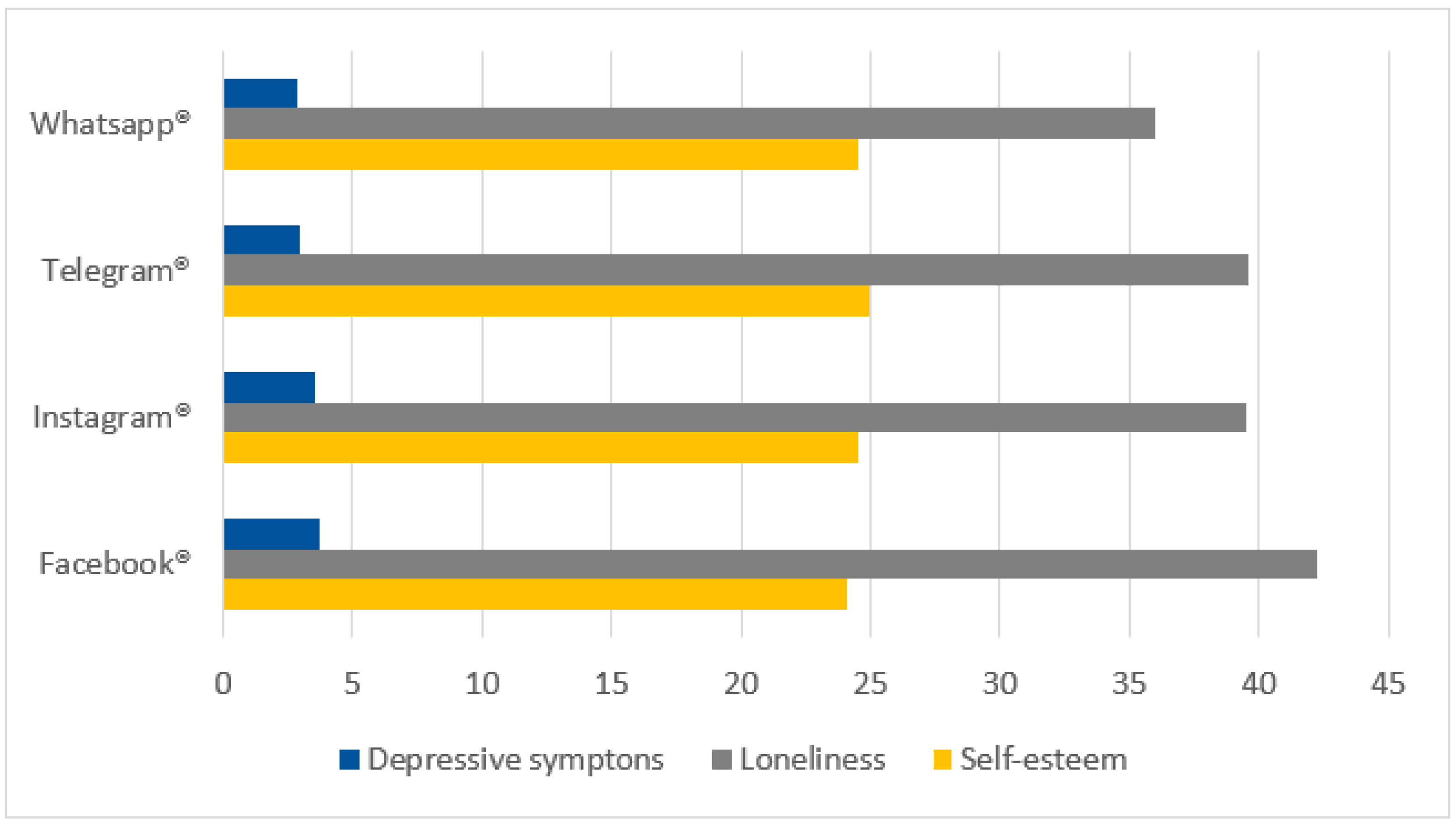

- Investigate the association between social media use and indicators of psychological well-being (self-esteem, loneliness, and depressive symptoms);

- Examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social media usage patterns by older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics: means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages to characterize the sample;

- Student’s t-test and ANOVA: for comparisons between groups in continuous variables [32];

- Chi-square test: for associations between categorical variables [33];

- Multivariate logistic regression: to identify predictors of intensive social network use, controlling for confounding variables [34];

- Pearson correlation analysis: to examine relationships between social network use and health/well-being variables [35].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profile of Participants

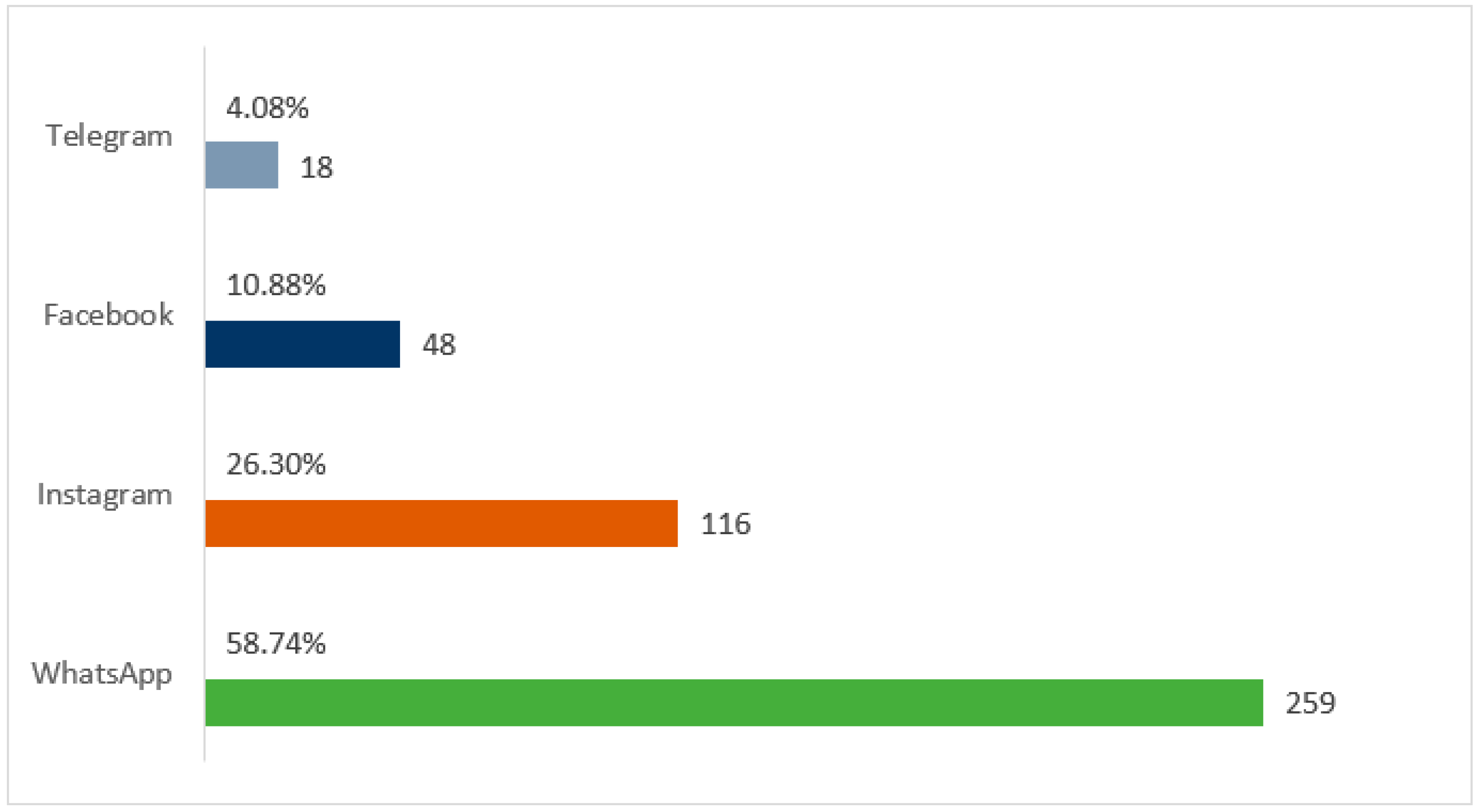

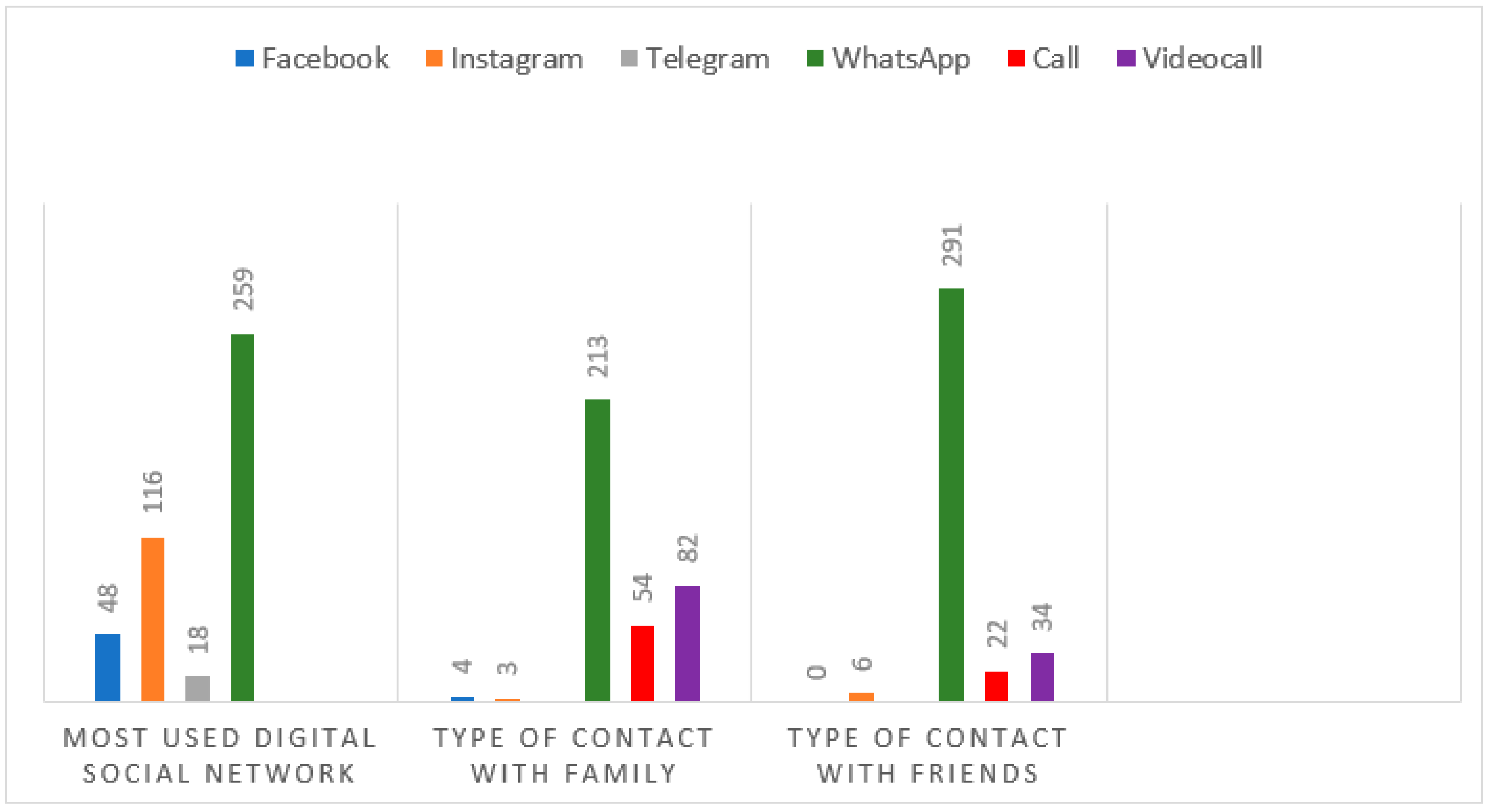

3.2. Social Media Usage Patterns

3.3. Impact in the Use Social Media During the Pandemic

- 86.85% of participants reported being in social isolation;

- 40.82% maintained virtual contact with family;

- 27.89% maintained both in-person and virtual contact with family;

- 75.06% maintained virtual contact with friends, mainly via WhatsApp® (65.99%).

3.4. Relationship Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Social Media Use

- Age and platform preference: younger participants (60–69 years) tended to use Instagram® more, while older ones preferred WhatsApp®;

- Education and frequency of use: higher education was associated with more frequent social media use;

- Income and platform diversity: participants with higher income used a greater variety of social networks.

3.5. Health Aspects and Their Relationship with Social Media Use

- A total of 84.13% of participants regularly used medications.

- Hypertension (46.71%);

- Back problems (40.59%);

- Insomnia (34.01%);

- Anxiety or panic disorder (32.20%).

- 49.89% of participants had the disease;

- 96.83% were vaccinated, with 75.82% having received four doses of the vaccine.

3.6. Income and Activities of Participants

3.7. Social Media Use and Social Contact During the Pandemic

3.8. Relationship Between Social Media Use and Health Aspects

3.9. Impact of COVID-19 on Social Media Use

- Participants who had COVID-19 increased their social media use by an average of 2.3 h/week (p < 0.01);

- Having family members who contracted COVID-19 was associated with an increase of 1.8 h/week in social media use (p < 0.05);

- 88.21% of participants reported using social media to obtain information about the pandemic.

3.10. Barriers and Facilitators in Social Media Use

3.11. Social Media Usage Patterns by Age Group

- Participants aged 60–69 were more likely to use multiple platforms (p < 0.01);

- Facebook® use was more prevalent among those aged 70–79 (p < 0.05);

- Participants aged 80 or older showed a strong preference for WhatsApp® (p < 0.001).

3.12. Relationship Between Social Media Use and Well-Being Indicators

- Life satisfaction (r = 0.31, p < 0.001);

- Perception of social support (r = 0.28, p < 0.001);

- Depressive symptoms (r = −0.22, p < 0.01).

3.13. Use of Social Media for Health Purposes

3.14. Impact of Social Isolation on Social Media Use

- 72.32% increased their frequency of social media use;

- 58.49% reported that social media were “very important” in dealing with isolation;

- 45.17% started using new platforms or digital features.

3.15. Association Between Socioeconomic Characteristics and Usage Patterns

- Higher education (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.13);

- Monthly income above 5 MW (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.24–2.49);

- Residing in an urban area (OR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.45–3.12);

- Having more than three devices connected to the internet (OR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.36–2.71).

3.16. Perceptions of the Impact of Social Media on Well-Being

- Social connection (78.23%);

- Access to information (72.56%);

- Entertainment (68.93%).

- Privacy (32.20%);

- Sleep quality (18.37%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Usage Patterns and Sociodemographic Factors

4.2. Impact of the Pandemic on Social Media Use

4.3. Social Networks, Health, and Well-Being

4.4. Barriers and Facilitators

5. Conclusions

6. Implications and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations—Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. United Nations. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo 2022—Base dos Dados. Available online: https://basedosdados.org/dataset/08a1546e-251f-4546-9fe0-b1e6ab2b203d?table=ebd0f0fd-73f1-4295-848a-52666ad31757&utm_term=censoibge2022&utm_campaign=Trend+do+Censo+2022&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc&hsa_acc=9488864076&hsa_cam=21101952202&hsa_grp=160 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Seifert, A.; Cotten, S.R.; Xie, B. A Double Burden of Exclusion? Digital and Social Exclusion of Older Adults in Times of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e99–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurostat. Digital Economy and Society Statistics—Households and Individuals—Statistics Explained—Eurostat. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Digital_economy_and_society_statistics_-_households_and_individuals (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Vogels, E.A. The Online Resource for Massachusetts Poverty Law Advocates. 2023. Available online: https://www.masslegalservices.org/content/digital-divide-persists-even-americans-lower-incomes-make-gains-tech-adoption (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Mariano, J.; Marques, S.; Ramos, M.R.; Gerardo, F.; da Cunha, C.L.; Girenko, A.; Alexandersson, J.; Stree, B.; Lamanna, M.; Lorenzatto, M.; et al. Too old for technology? Stereotype threat and technology use by older adults. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, C.; Whitehead, J.; Shah, R.; Adams, A.M.; Dooley, D.; Spreng, R.N.; Aunio, A.-L.; Dubé, L. Social Prescription Interventions Addressing Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Meta-Review Integrating On-the-Ground Resources. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Charness, N.; Fingerman, K.; Kaye, J.; Kim, M.T.; Khurshid, A. When Going Digital Becomes a Necessity: Ensuring Older Adults’ Needs for Information, Services, and Social Inclusion During COVID-19. In Older Adults and COVID-19, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, S.T.; Luijkx, K.G.; Rijnaard, M.D.; Nieboer, M.E.; van der Voort, C.S.; Aarts, S.; van Hoof, J.; Vrijhoef, H.J.; Wouters, E.J. Older Adults’ Reasons for Using Technology while Aging in Place. Gerontology 2016, 62, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, E.; Baber, F.; Corbett, E.; Ellis, D.; Gillison, F.; Barnett, J. The use of technology to address loneliness and social isolation among older adults: The role of social care providers. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.; Vitali, M.M.; Bousfield, A.B.d.S.; Camargo, B.V. Teoria das Representações Sociais e Modelo STAM: Aceitação da Internet entre Idosos. Psicol. Teor. e Pesqui. 2024, 40, e40303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.L.; Borim, F.S.A.; Fontes, A.P.; Rabello, D.F.; Cachioni, M.; Batistoni, S.S.T.; Yassuda, M.S.; de Souza-Júnior, P.R.B.; de Andrade, F.B.; Lima-Costa, M.F. Factors associated with perceived quality of life in older adults. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 52 (Suppl. 2), 16s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havighurst, R.J. Successful Aging. Gerontologist 1961, 1, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. Changes in Internet Use When Coping With Stress: Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.C. A Continuity Theory of Normal Aging. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, B.; Laumann, E.O. The health benefits of network growth: New evidence from a national survey of older adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 125, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltes, M.M.; Carstensen, L.L. The process of successful aging: Selection, optimization, and compensation. In Understanding Human Development: Dialogues with Lifespan Psychology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Ajrouch, K.J.; Manalel, J.A. Social Relations and Technology: Continuity, Context, and Change. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, igx029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowgill, D.O. Aging and Modernization; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1972; 331p, ISBN 0390213187. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, S.J.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N.; Rogers, W.A. Designing for Older Adults; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T. Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support, and Health. In Social Epidemiology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Anderson, W.A.; McCullough, B.M. Impact of Internet Use on Loneliness and Contact with Others Among Older Adults: Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, M.W.; Johnson, M.; Foner, A. Aging and Society: A Sociology of Age Stratification; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hargittai, E.; Dobransky, K. Old Dogs, New Clicks: Digital Inequality in Internet Skills and Uses among Older Adults. Can. J. Commun. 2017, 42, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, A. Technology and the Challenge of Aging. In Technologies for Active Aging; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; 438p, ISBN 978-1-5063-8670-6. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, G.M.; Quaresma, M.R.; Ferreira, L.M. Adaptação cultural e validação da versão brasileira da escala de autoestima de Rosenberg. Rev. Bras. Cir. Plást. 2004, 19, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, S.M.; de Andrade, V.S.; Midgett, A.H.; de Carvalho, R.G.N. Evidências de validade da Escala Brasileira de Solidão UCLA. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 65, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.P.; Almeida, S.A. Confiabilidade da versão brasileira da Escala de Depressão em Geriatria (GDS) versão reduzida. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 1999, 57, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. RA Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D.W. A note on consistency of non-parametric rank tests and related rank transformations. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2012, 65, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Medica. 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandei, S. Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochem. Medica. 2014, 24, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekwegh, T.; Cobb, S.; Adinkrah, E.K.; Vargas, R.; Kibe, L.W.; Sanchez, H.; Waller, J.; Ameli, H.; Bazargan, M. Factors Associated with Telehealth Utilization among Older African Americans in South Los Angeles during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nef, T.; Ganea, R.L.; Müri, R.M.; Mosimann, U.P. Social networking sites and older users—A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.S.-S.; McGill, K.; Malden, S.; Wilson, C.; Pearce, C.; Kaner, E.; Vines, J.; Aujla, N.; Lewis, S.; Restocchi, V.; et al. Examining the social networks of older adults receiving informal or formal care: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnes, M.; Løe, I.C.; Kalseth, J. Exploring the impact of information and communication technologies on loneliness and social isolation in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerson, A. Successful Aging in a Time of Wildfires Field Project. In Proceedings of the 105th Annual Meeting American Meteorogical Society, New Orleans, LA, USA, 12–16 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Martel, J.; Dembicki, J.; Bubric, K. Applying Human Factors to Modify and Design Healthcare Workspaces and Processes in Response to COVID-19. Ergon. Des. Q. Hum. Factors Appl. 2025, 33, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, A.; Hargittai, E. A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 3937–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülür, G.; Macdonald, B. Rethinking social relationships in old age: Digitalization and the social lives of older adults. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanandini, D. Social Transformation in Modern Society: A Literature Review on the Role of Technology in Social Interaction. J. Ilm. Ekotrans Erud. 2024, 4, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhai, Y.; Shahzad, F. Mapping the terrain of social media misinformation: A scientometric exploration of global research. Acta Psychol. 2025, 252, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J. The causal effect of Internet use on rural middle-aged and older adults’ depression: A propensity score matching analysis. Digit Health 2025, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, I.; Coelho, F.; Rando, B.; Abreu, A.M. A Comparative Study of Short-Term Social Media Use with Face-to-Face Interaction in Adolescence. Children 2025, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, B.; Apuke, O.D.; Nor, Z.M. The intrinsic and extrinsic factors predicting fake news sharing among social media users: The moderating role of fake news awareness. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.B.; Courtney, A.L.; Liang, D.; Swinchoski, A.; Goodson, P.; Denny, B.T. Social support and adaptive emotion regulation: Links between social network measures, emotion regulation strategy use, and health. Emotion 2024, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. About BeConnected|Be Connected|Every Australian Online. 2023. Available online: https://beconnected.esafety.gov.au/about-beconnected (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Infocomm Media Development Authority. Silver Infocomm Junctions. 2024. Available online: https://www.imda.gov.sg/multiple-language/seniorsgodigital/stories/silver-infocomm-junctions (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Older Adults Technology Services (OATS). Welcome to Senior Planet—Senior Planet from AARP. 2024. Available online: https://seniorplanet.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Jafar, Z.; Quick, J.D.; Rimányi, E.; Musuka, G. Social Media and Digital Inequity: Reducing Health Inequities by Closing the Digital Divide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age Group | |

| 60 to 69 years | 360 (81.63%) |

| 70 to 79 years | 68 (15.42%) |

| 80 years or older | 13 (2.95%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 363 (82.31%) |

| Male | 78 (17.69%) |

| Skin Color | |

| White | 386 (87.53%) |

| Mixed | 33 (7.48%) |

| Black | 14 (3.18%) |

| Yellow | 6 (1.36%) |

| Indigenous | 2 (0.45%) |

| Marital Status | |

| With Partner | 256 (58.05%) |

| Without Partner | 185 (41.95%) |

| Education | |

| Mean years of schooling | 17.46 ± 5.84 |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Monthly income of the older adult | |

| 1 MW | 46 (10.43%) |

| 2 MW | 50 (11.33%) |

| 3 to 5 MW | 140 (31.75%) |

| 6 to 9 MW | 94 (21.32%) |

| 10 MW or more | 101 (22.90%) |

| Don’t know | 10 (2.27%) |

| Daily activities | |

| Domestic activities | 136 (30.84%) |

| Paid work | 84 (19.05%) |

| Paid work and others | 89 (20.18%) |

| Sports and dance | 57 (12.92%) |

| Volunteer work | 56 (12.70%) |

| None | 19 (4.31%) |

| Predictor | Outcome | Beta (Β)/OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of social media use | Number of comorbidities | β = 0.18 | <0.01 |

| Use of social media for health information seeking | Presence of chronic diseases | OR = 1.45 (1.22–1.73) | <0.001 |

| Greater engagement in social media | Better perception of quality of life | β = 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Facilitators | n (%) | Barriers | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintaining contact with family/friends | 389 (88.21%) | Privacy concerns | 201 (45.58%) |

| Access to information | 312 (70.75%) | Technical difficulties | 178 (40.36%) |

| Entertainment | 287 (65.08%) | Lack of interest in some platforms | 156 (35.37%) |

| Learning new skills | 201 (45.58%) | Excessive time spent online | 134 (30.39%) |

| Sharing experiences | 189 (42.86%) | Exposure to negative news | 112 (25.40%) |

| Indicator | Correlation Coefficient (R) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Social support | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.22 | <0.01 |

| Purpose | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Seeking health information | 312 (70.75%) |

| Sharing health experiences | 189 (42.86%) |

| Contact with health professionals | 156 (35.37%) |

| Participation in online support groups | 134 (30.39%) |

| Scheduling appointments/exams | 112 (25.40%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, R.M.; Menezes, J.D.d.S.; Pompeo, D.A.; Diniz, M.A.A.; Lima, G.S.; Ribeiro, P.C.P.S.V.; André, J.C.; Ribeiro, R.d.C.H.M.; Rodrigues, R.A.P.; Kusumota, L. Beyond Isolation: Social Media as a Bridge to Well-Being in Old Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060882

Ribeiro RM, Menezes JDdS, Pompeo DA, Diniz MAA, Lima GS, Ribeiro PCPSV, André JC, Ribeiro RdCHM, Rodrigues RAP, Kusumota L. Beyond Isolation: Social Media as a Bridge to Well-Being in Old Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060882

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Renato Mendonça, João Daniel de Souza Menezes, Daniele Alcalá Pompeo, Maria Angélica Andreotti Diniz, Gabriella Santos Lima, Patrícia Cruz Pontífice Sousa Valente Ribeiro, Júlio César André, Rita de Cássia Helú Mendonça Ribeiro, Rosalina Aparecida Partezani Rodrigues, and Luciana Kusumota. 2025. "Beyond Isolation: Social Media as a Bridge to Well-Being in Old Age" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060882

APA StyleRibeiro, R. M., Menezes, J. D. d. S., Pompeo, D. A., Diniz, M. A. A., Lima, G. S., Ribeiro, P. C. P. S. V., André, J. C., Ribeiro, R. d. C. H. M., Rodrigues, R. A. P., & Kusumota, L. (2025). Beyond Isolation: Social Media as a Bridge to Well-Being in Old Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060882