High Rate of Inappropriate Utilization of an Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Prospective Analysis of Patient Perceptions and Contributing Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

- Explore patients’ motivations for utilizing emergency services and their subjective assessment of urgency;

- Identify structural and psychological barriers to accessing regular outpatient eye care;

- Compare patient-reported urgency with the urgency as assessed by treating ophthalmologists.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Questionnaire Structure and Administration

2.3. Physician Urgency Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations and Data Protection

2.6. Generative AI Disclosure

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

3.2. Symptom Characteristics

3.3. Perceived vs. Clinical Urgency

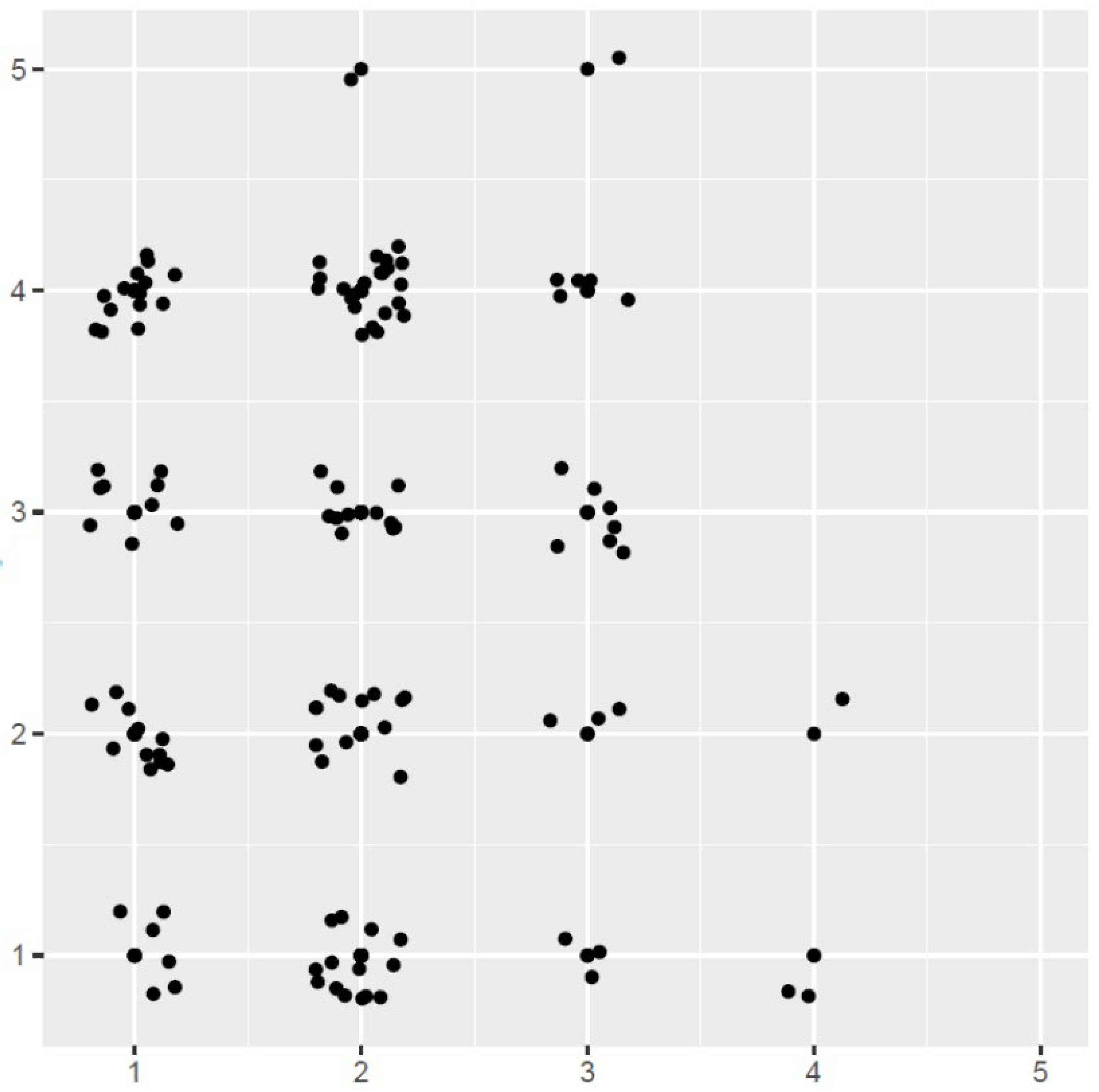

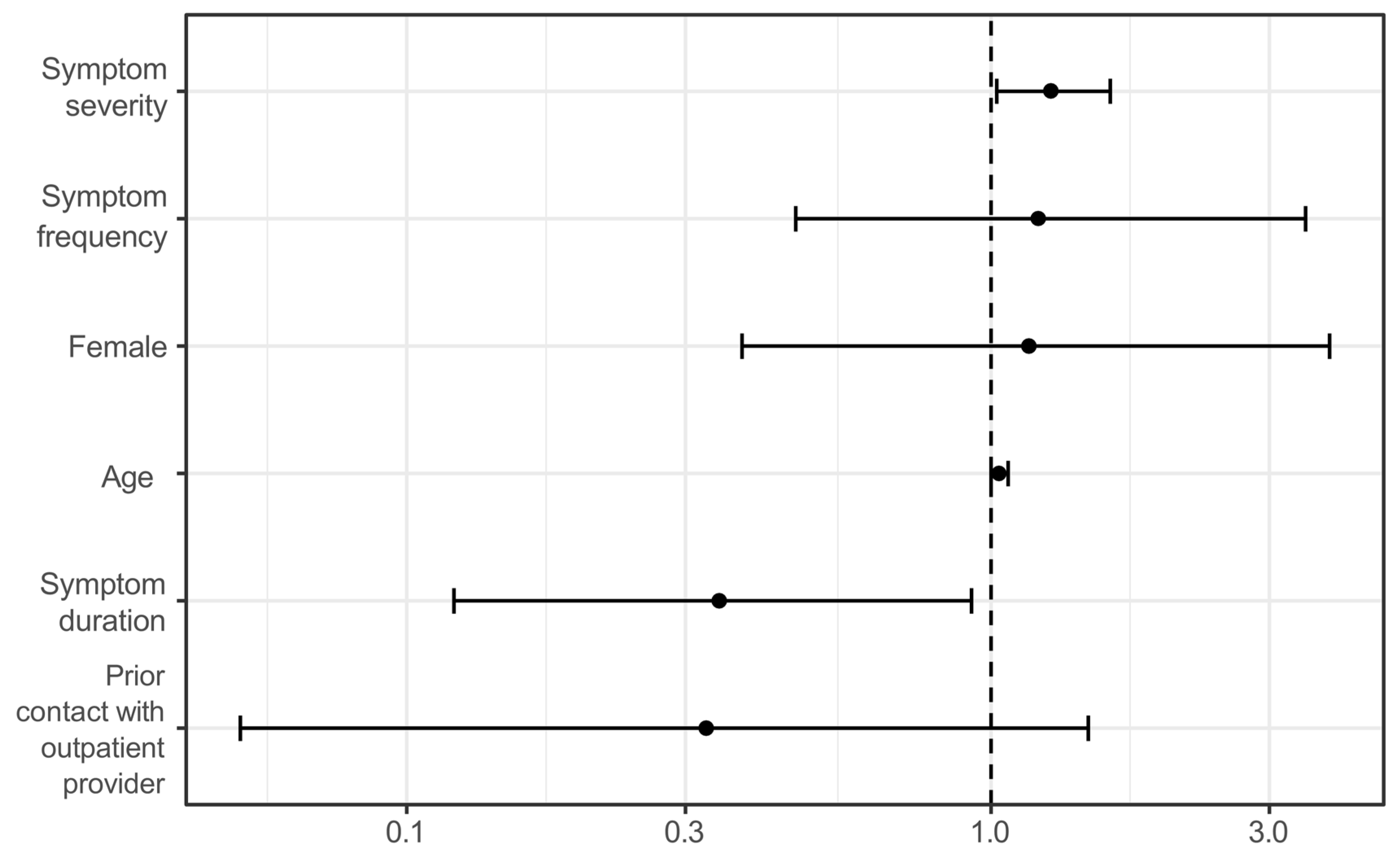

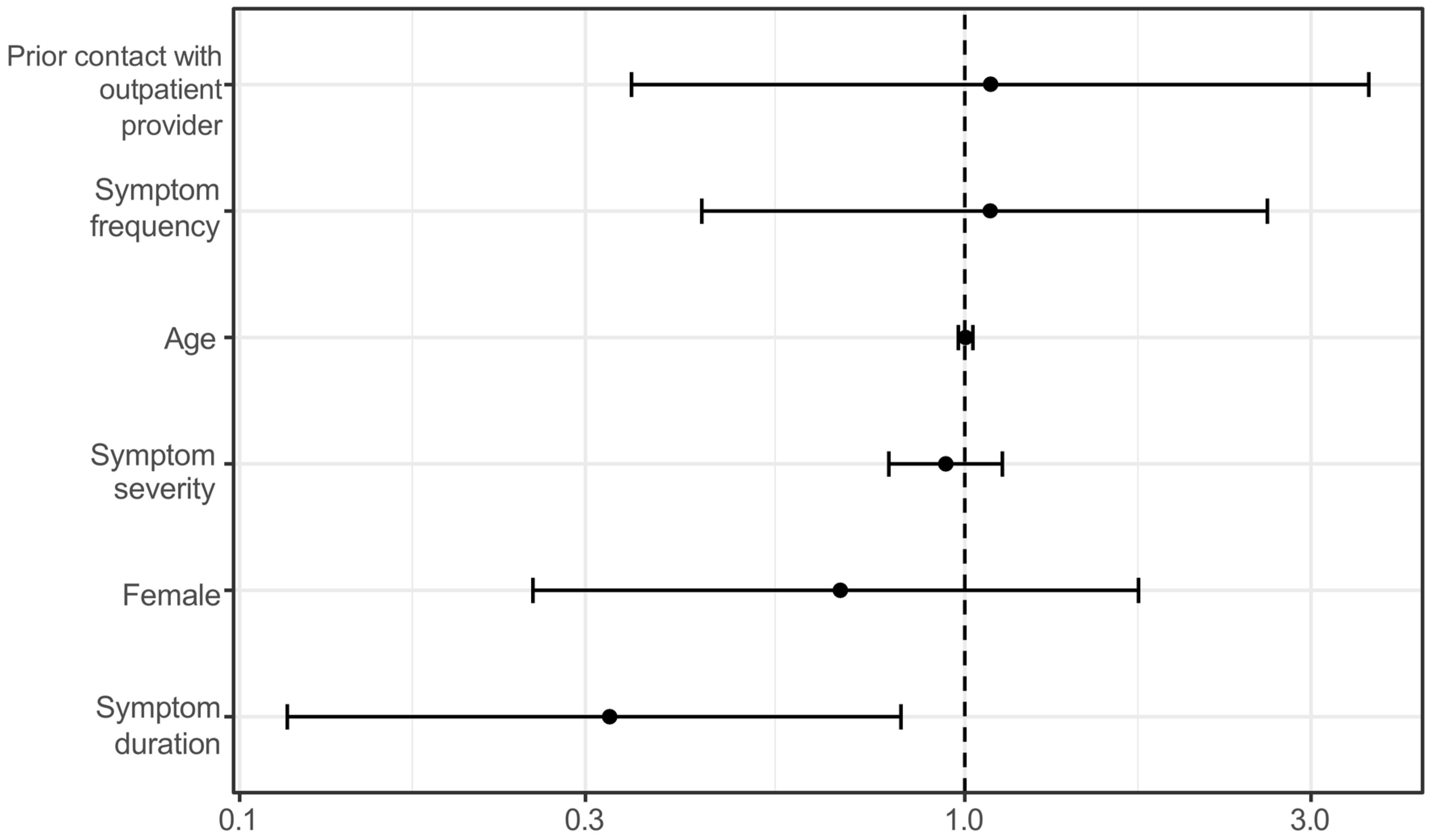

3.4. Determinants of Urgency Assessment

3.5. Additional Influencing Factors

3.6. Access to Care and Knowledge of Alternatives

4. Discussion

4.1. Inappropriate Utilization of Ophthalmic Emergency Services in Freiburg

4.2. Factors Contributing to Inappropriate Utilization

4.3. Comparison with International Studies

4.4. Contrasting the German Healthcare System with International Settings

4.5. Limitations and Contextual Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

| Symptom | Symptom Present—Mean/Median | Symptom Absent—Mean/Median | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 2.59/3 | 2.88/3 | Slightly lower urgency when present. |

| Trauma | 3.14/4 | 2.63/3 | Markedly higher urgency when present. |

| Vision loss | 3.15/3 | 2.66/3 | Higher urgency when present. |

| Swelling | 2.33/2 | 2.90/3 | Lower urgency when present. |

| Redness | 2.34/2 | 3.07/3 | Lower urgency when present. |

| Double vision | 2.00/2 | 2.77/3 | Higher urgency, limited cases. |

References

- Kheterpal, S.; Perry, M.E.; McDonnell, P.J. General Practice Referral Letters to a Regional Ophthalmic Accident and Emergency Department. Eye 1995, 9, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, S.; Ioannidis, A.; Masaoutis, P.; Verma, S. Patterns of Ophthalmological Complaints Presenting to a Dedicated Ophthalmic Accident & Emergency Department: Inappropriate Use and Patients’ Perspective. Emerg. Med. J. 2008, 25, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Carvalho, R.; José, N.K. Ophthalmology Emergency Room at the University of São Paulo General Hospital: A Tertiary Hospital Providing Primary and Secondary Level Care. Clinics 2007, 62, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, J.; Isom, R.F.; Schiffman, J.C.; Ajuria, L.; Huang, L.C.; Gologorsky, D.; Banta, J.T. Utilization of Ophthalmology-Specific Emergency Department Services. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 33, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Hsu, C.-A.; Hsiao, S.-H.; Chu, D.; Yen, J.-C. Utilization of Emergency Ophthalmology Services in Taiwan: A Nationwide Population Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, I.; Thomas, M.G.; Shirodkar, A.-L.; Kuht, H.J.; Ku, J.Y.; Chaturvedi, R.; Beer, F.; Patel, R.; Rana-Rahman, R.; Anderson, S.; et al. Patterns of Attendances to the Hospital Emergency Eye Care Service: A Multicentre Study in England. Eye 2022, 36, 2304–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.Z.; Nakayama, L.F.; Bergamo, V.C.; Regatieri, C.V.S. Ophthalmology Emergency Department Visits in a Brazilian Tertiary Hospital over the Last 11 Years: Data Analysis. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2023, 86, e20230067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, S.; Jackson, E.; Fenton, M. An Audit of the Ophthalmic Division of the Accident and Emergency Department of the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, Dublin. Ir. Med. J. 2001, 94, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gesetz zur Stärkung der Versorgung in der Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (GKV-VSG). 2015. Vol. §75 Abs. 1a SGB V.; BGBl. I 2015, S. 1211. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/gesetze-und-verordnungen/detail/gkv-versorgungsstaerkungsgesetz.html (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Frick, J.; Möckel, M.; Schmiedhofer, M.; Searle, J.; Erdmann, B.; Erhart, M.; Slagman, A. Questionnaire for the utilization of the Emergency Department: Implications for the patient survey. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed. 2019, 114, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempere-Selva, T.; Peiró, S.; Sendra-Pina, P.; Martínez-Espín, C.; López-Aguilera, I. Inappropriate Use of an Accident and Emergency Department: Magnitude, Associated Factors, and Reasons—An Approach with Explicit Criteria. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2001, 37, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, T.R. Contributing Factors of Frequent Use of the Emergency Department: A Synthesis. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 35, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, H.; Böhringer, D.; Wacker, K.; Niedenhoff, P.J.L.; Mittelviefhaus, H.; Reinhard, T. Duration of Consultations in an Outpatient Ophthalmology Unit. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, N.; Wübker, A.; Wuckel, C. Waiting Times for Outpatient Treatment in Germany: New Experimental Evidence from Primary Data. Jahrbücher Natl. Stat. 2018, 238, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Augustin, J.; Lischka, T. Parameters for measuring the regional healthcare situation: A comparison of different healthcare parameters by the example of ophthalmologic care in the metropolitan region Hamburg. Ophthalmologe 2021, 118, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health Literacy in Europe: Comparative Results of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altin, S.V.; Stock, S. The Impact of Health Literacy, Patient-Centered Communication and Shared Decision-Making on Patients’ Satisfaction with Care Received in German Primary Care Practices. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Perceived Urgency (By Patient) | Mean/Median/Max Symptom Severity |

|---|---|

| Immediate | 5/7/9 |

| Within 1 h | 4/5/7 |

| Within a few days | 3/4.5/6 |

| Within weeks | 2/4/4.5 |

| Within months | 10/10/10 |

| Patient-Rated Urgency | Physician-Rated Urgency (Mean) | Physician-Rated Urgency (Median) |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate (5) | 2.78 | Within a few days (3) |

| Within 1 h (4) | 2.72 | Within a few days (3) |

| Within 1–2 days (3) | 2.89 | Within a few days (3) |

| Within weeks (2) | 1.33 | Within months (1) |

| Within months (1) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siegel, H.; Widmer, V.A.; Kammrath Betancor, P.; Böhringer, D.; Reinhard, T. High Rate of Inappropriate Utilization of an Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Prospective Analysis of Patient Perceptions and Contributing Factors. Medicina 2025, 61, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071163

Siegel H, Widmer VA, Kammrath Betancor P, Böhringer D, Reinhard T. High Rate of Inappropriate Utilization of an Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Prospective Analysis of Patient Perceptions and Contributing Factors. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071163

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiegel, Helena, Vera Anna Widmer, Paola Kammrath Betancor, Daniel Böhringer, and Thomas Reinhard. 2025. "High Rate of Inappropriate Utilization of an Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Prospective Analysis of Patient Perceptions and Contributing Factors" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071163

APA StyleSiegel, H., Widmer, V. A., Kammrath Betancor, P., Böhringer, D., & Reinhard, T. (2025). High Rate of Inappropriate Utilization of an Ophthalmic Emergency Department: A Prospective Analysis of Patient Perceptions and Contributing Factors. Medicina, 61(7), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071163