Synthetic Linear Lipopeptides and Lipopeptoids Induce Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress: In Vitro Cytotoxicity and SAR Evaluation Against Cancer Cell Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

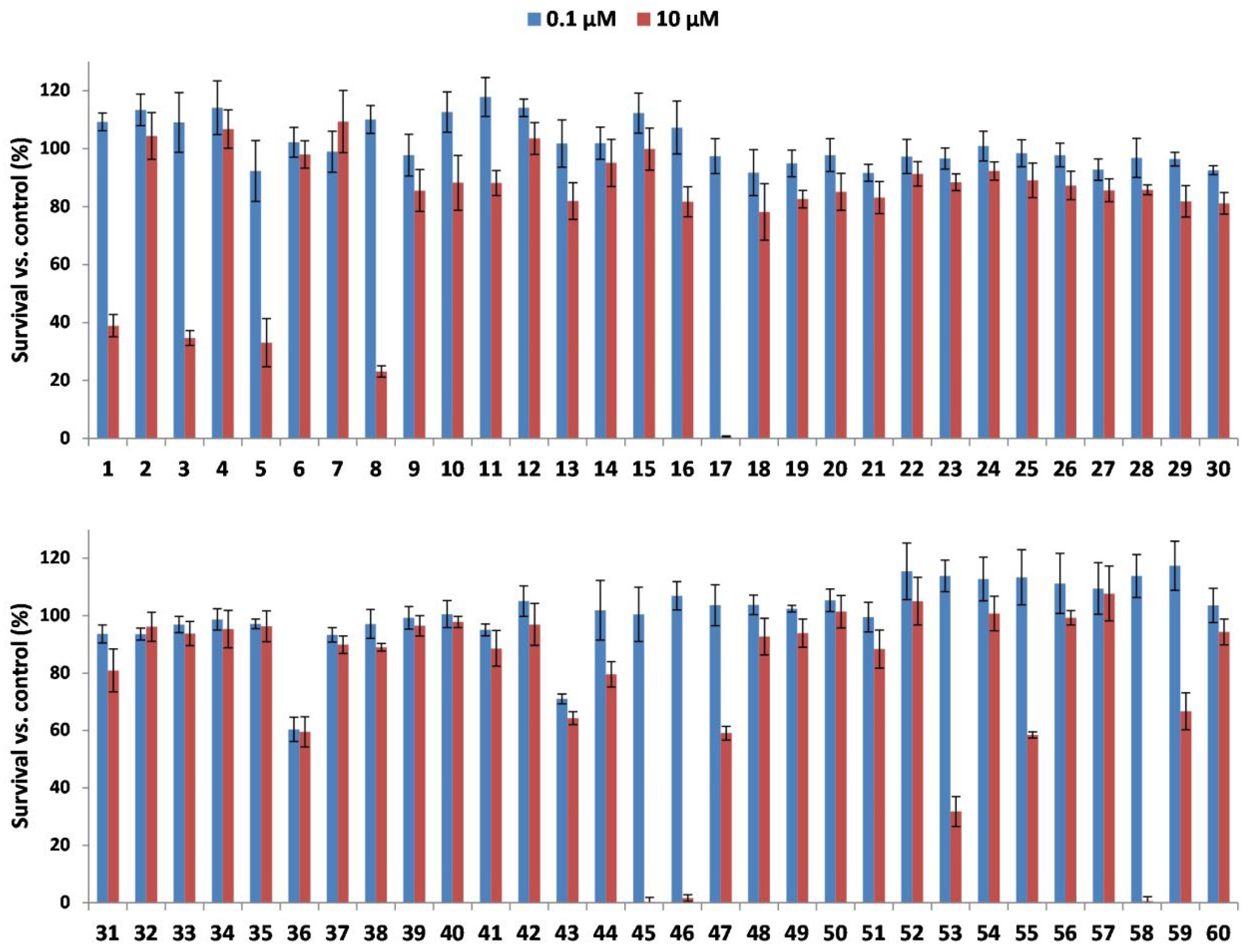

2.1. Cytotoxic Activity of LLPs

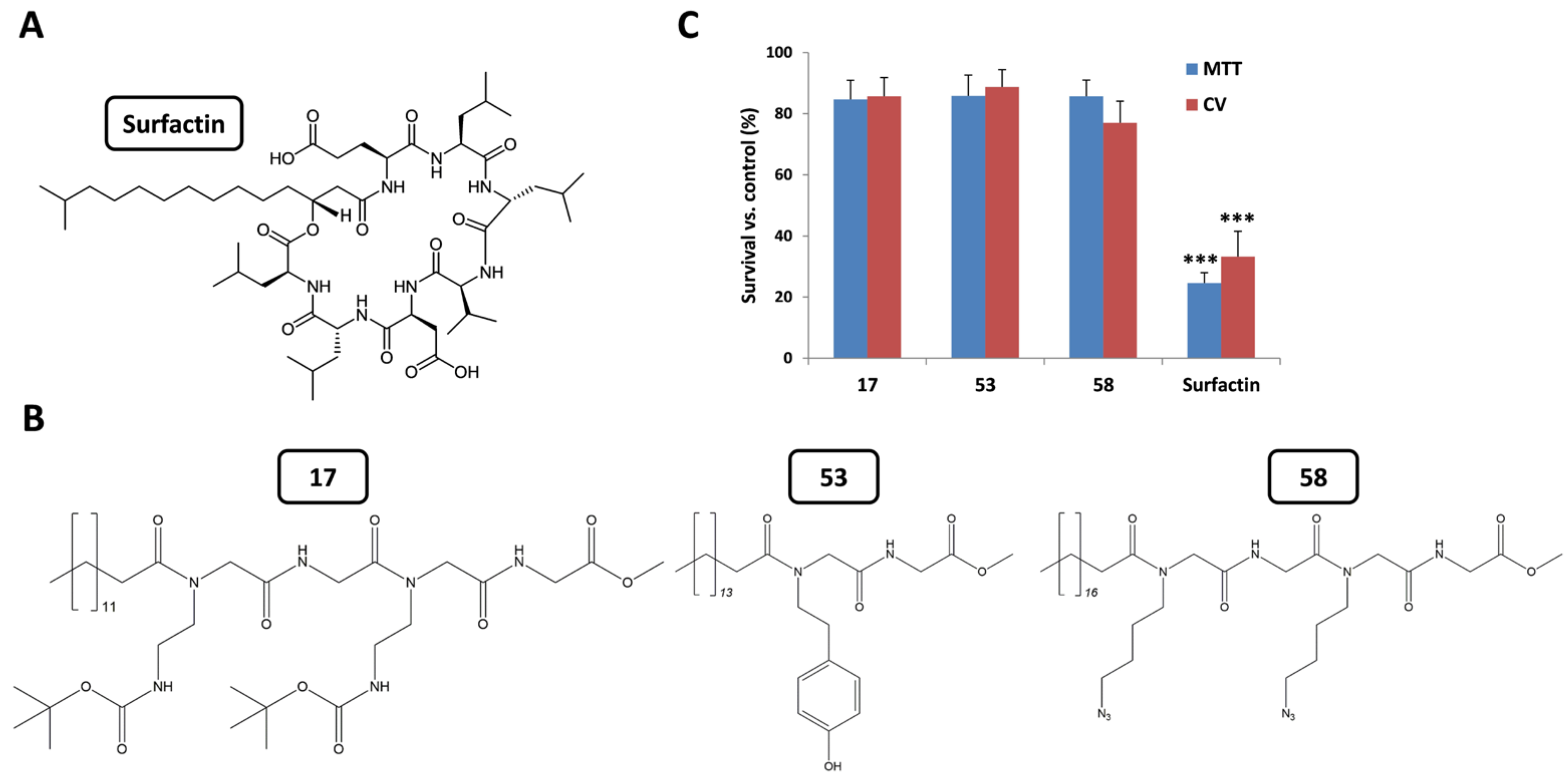

2.2. Evaluation of Cytotoxic Selectivity Against Normal Fibroblasts

2.3. Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis

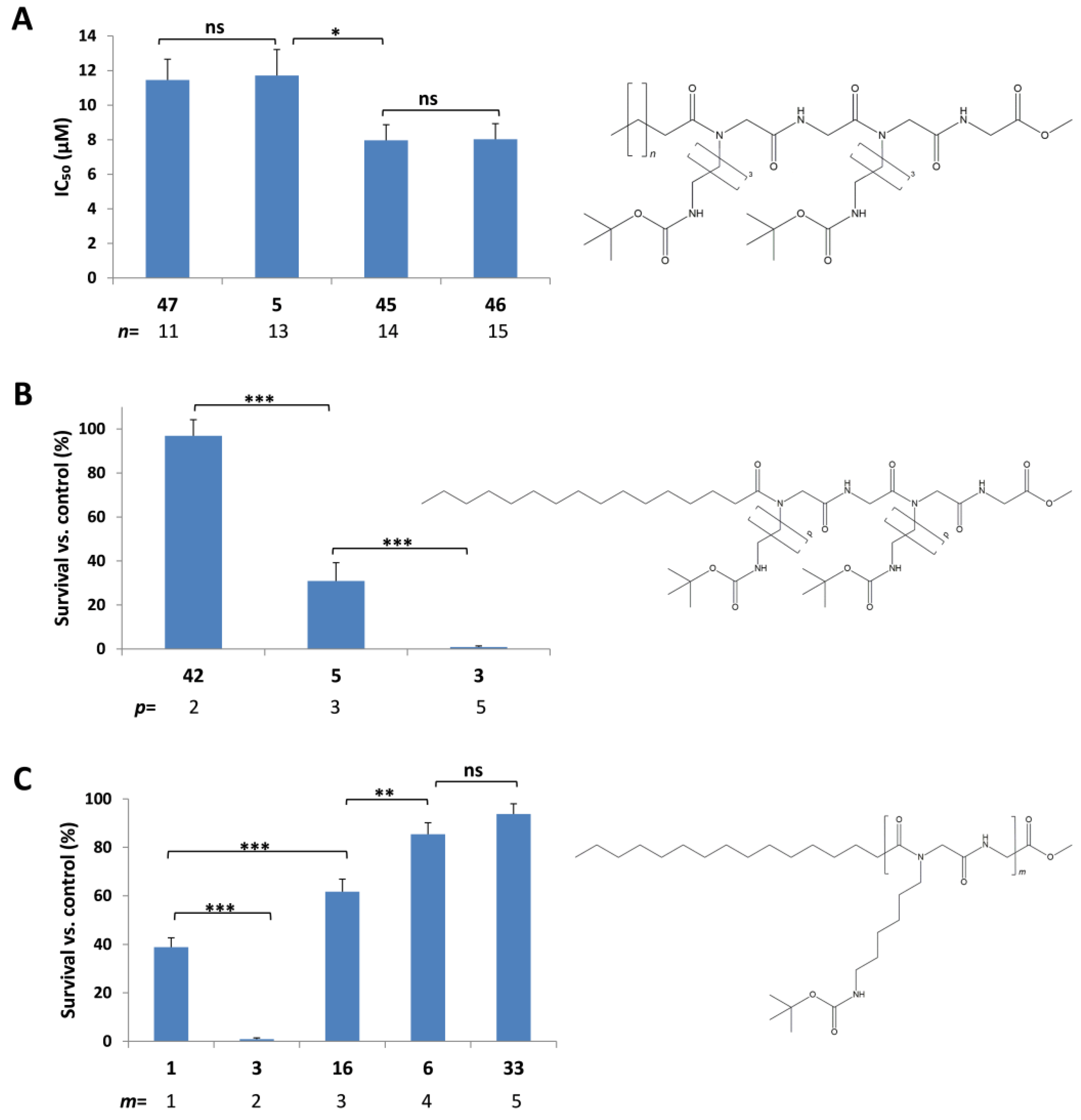

2.3.1. Effect of the C-Terminus Functional Group on Cytotoxic Activity

2.3.2. Effect of Lipophilic Tail Length on the Cytotoxic Activity

2.3.3. Effect of Alkyl Side Chain Length on the Cytotoxic Activity

2.3.4. Effect of Side Chain Functional Groups on the Cytotoxic Activity

2.3.5. Effect of Peptidic Core Length on the Cytotoxic Activity

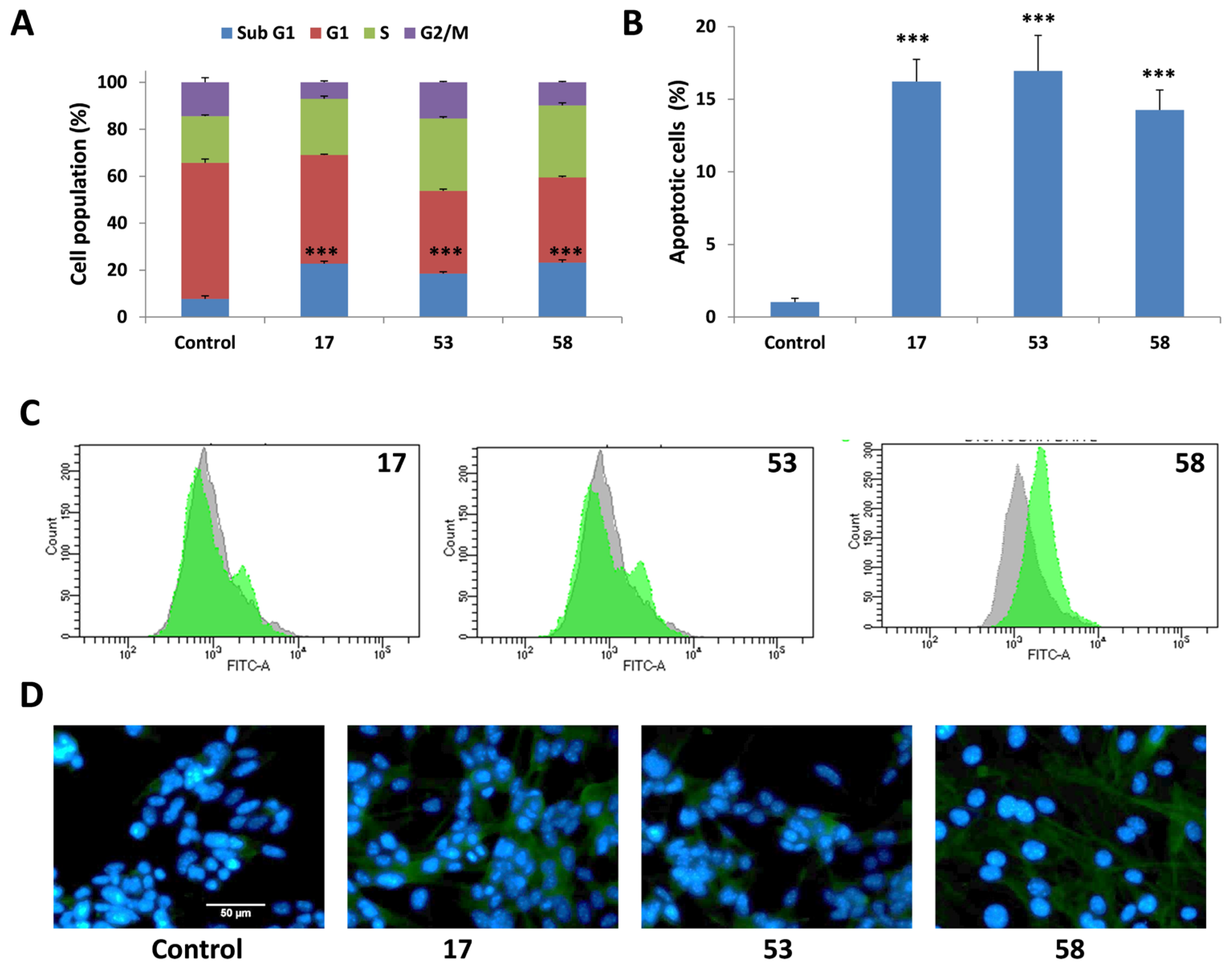

2.4. Mechanism of Action

2.4.1. Induction of sub-G1 Cell Cycle Arrest

2.4.2. Induction of Apoptosis Confirmed by Annexin v/PI Staining

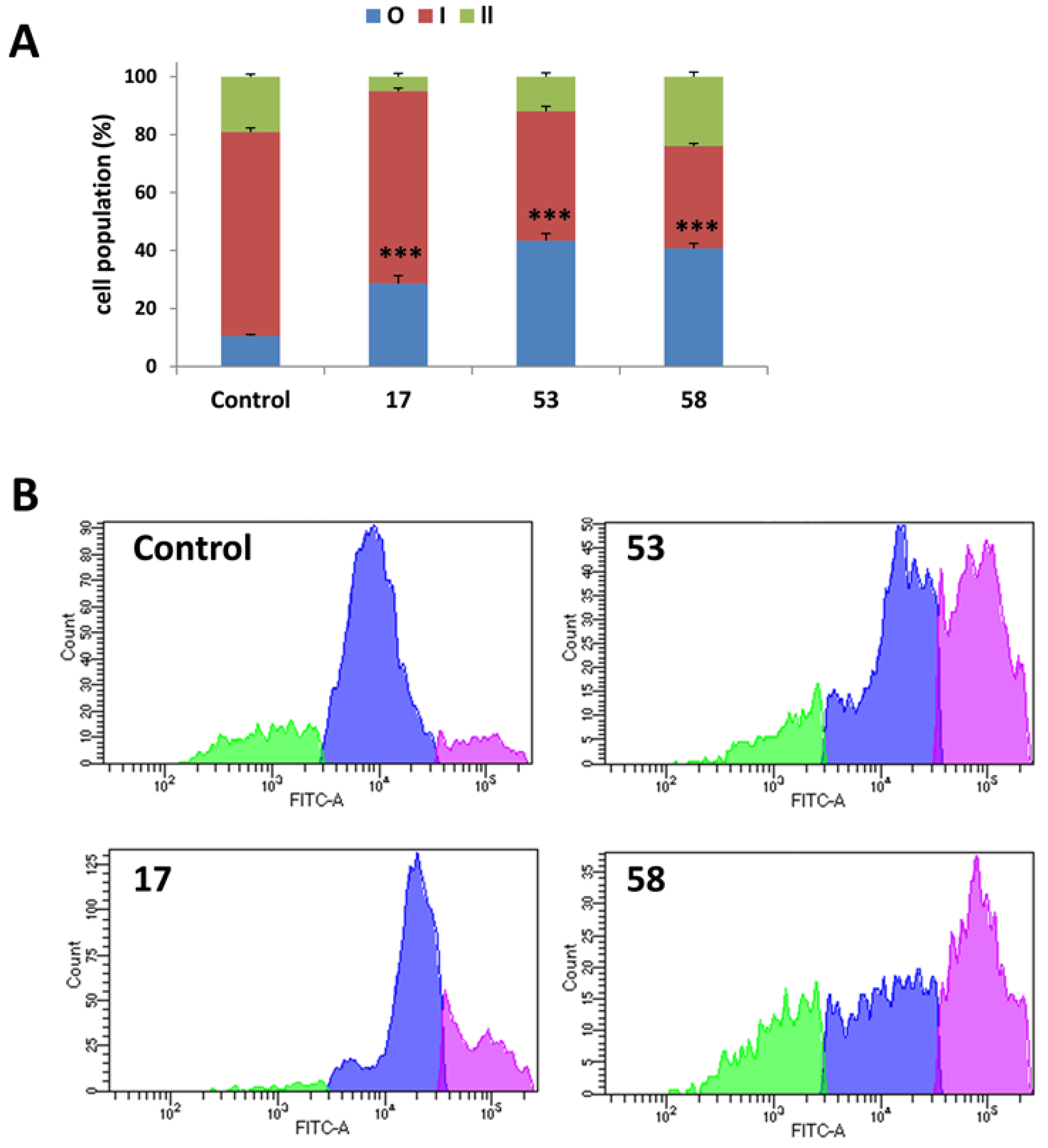

2.4.3. Activation of Caspases During LLP-Induced Apoptosis

2.4.4. Lack of Autophagy Induction

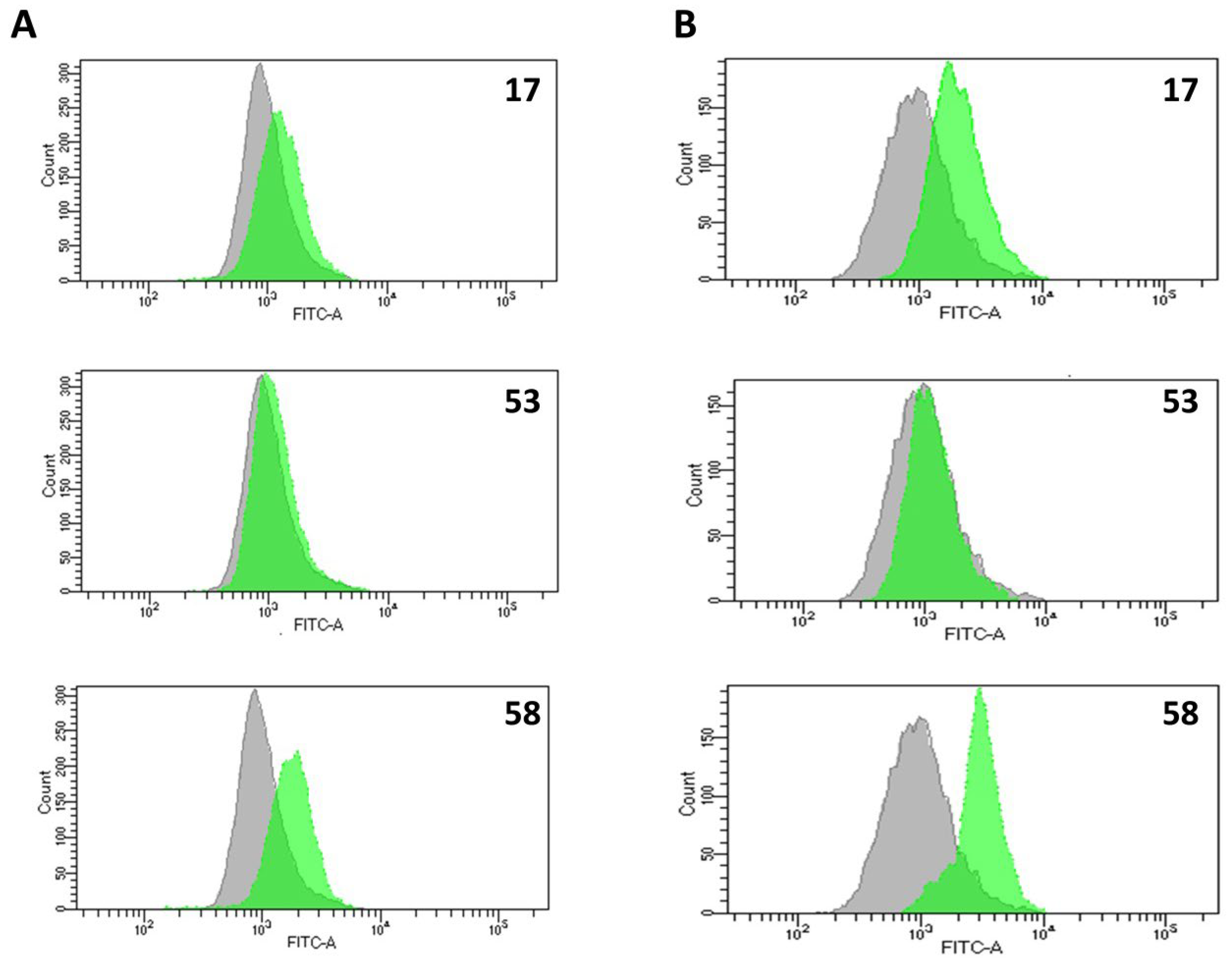

2.4.5. Effect of LLPs on Cell Proliferation

2.4.6. Generation of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (ROS/RNS) and Nitric Oxide (NO)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General

4.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

4.3. MTT and CV Assays

4.4. Cell Cycle Analysis

4.5. Apoptosis Evaluation by Annexin V-FITC/PI Staining

4.6. ApoStat Caspase Detection Assay

4.7. Immunofluorescence Detection of Cleaved Caspase-3

4.8. CFSE-Based Cell Proliferation Assay

4.9. Detection of ROS/RNS and NO Production

4.10. Autophagy Analysis by Acridine Orange (AO) Staining

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLP | Linear Lipopeptide/Linear Lipopeptoid |

| Ugi-4CR | Ugi four-component reaction |

| SAR | Structure–Activity Relationship |

| CV | Crystal Violet |

| LP | Lipopeptide/Lipopeptoid |

| IC50 | Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| ApoStat | FITC-conjugated pan-caspase inhibitor |

| CFSE | Carboxyfluorescein Succinimidyl Ester |

| AO | Acridine Orange |

| ROS/RNS | Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, U.; Dey, A.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Sanyal, R.; Mishra, A.; Pandey, D.K.; De Falco, V.; Upadhyay, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Chaudhary, A.; et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, D.; Li, C. Complications and comorbidities associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy: Rethinking drug design and delivery for anticancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 2901–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.L. Drug repurposing for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunarkar-Patil, P.; Kaleem, M.; Mishra, R.; Ray, S.; Ahmad, A.; Verma, D.; Bhayye, S.; Dubey, R.; Singh, H.N.; Kumar, S. Anticancer Drug Discovery Based on Natural Products: From Computational Approaches to Clinical Studies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, W.A.; Okda, T.M.; Abd El Wahab, S.M.; Ezz-ElDien, E.S.; AboulWafa, O.M. Developing new anticancer agents: Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and in silico study of several functionalized pyrimidine-5-carbonitriles as small molecules modulators targeting breast cancer. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 153, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Aouidate, A.; Wang, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yuan, S. Discovering Anti-Cancer Drugs via Computational Methods. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Garcia, C.; Colomer, I. Lipopeptides as tools in catalysis, supramolecular, materials and medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 710–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balleux, G.; Höfte, M.; Arguelles-Arias, A.; Deleu, M.; Ongena, M. Bacillus lipopeptides as key players in rhizosphere chemical ecology. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, S.M.; Rishi, N.; Singh, R. Microbial lipopeptides: Properties, mechanics and engineering for novel lipopeptides. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kwon, J.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.C. Immunomodulatory Role of Microbial Surfactants, with Special Emphasis on Fish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.A.M.; Nitschke, M. Bacterial-derived surfactants: An update on general aspects and forthcoming applications. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mukherji, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Reimer, L.; Stallforth, P. Lipopeptide-mediated bacterial interaction enables cooperative predator defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2013759118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Chávez, C.; Benaud, N.; Ferrari, B.C. The ecological roles of microbial lipopeptides: Where are we going? Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnif, I.; Ghribi, D. Review lipopeptides biosurfactants: Mean classes and new insights for industrial, biomedical, and environmental applications. Biopolymers 2015, 104, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.R.; Kanwar, S.S. Lipopeptides as the antifungal and antibacterial agents: Applications in food safety and therapeutics. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 473050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresti, L.; Cappello, G.; Pini, A. Antimicrobial Peptides towards Clinical Application-A Long History to Be Concluded. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Chen, Z.; Fan, S.; Chen, D.; Xue, H.; Shi, W.; He, J. Short lipopeptides specifically inhibit the growth of Propionibacterium acnes with a dual antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 2321–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.C.; Liu, H.H.; Chen, I.H.; Chen, H.W.; Chong, P.; Leng, C.H.; Liu, S.J. A purified recombinant lipopeptide as adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 349783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Freitas, F.; Coelho de Assis Lage, T.; Ayupe, B.A.L.; de Paula Siqueira, T.; de Barros, M.; Tótola, M.R. Bacillus subtilis TR47II as a source of bioactive lipopeptides against Gram-negative pathogens causing nosocomial infections. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohamadi, H.; de Anda, J.; Lee, M.W.; Schmidt, N.W.; Mandal, T.; Wong, G.C.L. How Cell-Penetrating Peptides Behave Differently from Pore-Forming Peptides: Structure and Stability of Induced Transmembrane Pores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 26095–26105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, T.T.T.; Liu, J.F.; Wu, C.Z.; Lin, W.N.; Chen, Y.L.; Lee, I.T. Surfactin from Bacillus subtilis induces apoptosis in human oral squamous cell carcinoma through ROS-regulated mitochondrial pathway. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 7253–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaraguppi, D.A.; Bagewadi, Z.K.; Patil, N.R.; Mantri, N. Iturin: A Promising Cyclic Lipopeptide with Diverse Applications. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, S.; Romo, T.D.; Grossfield, A. Selectivity and Mechanism of Fengycin, an Antimicrobial Lipopeptide, from Molecular Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morejón, M.C.; Laub, A.; Kaluđerović, G.N.; Puentes, A.R.; Hmedat, A.N.; Otero-González, A.J.; Rivera, D.G.; Wessjohann, L.A. A multicomponent macrocyclization strategy to natural product-like cyclic lipopeptides: Synthesis and anticancer evaluation of surfactin and mycosubtilin analogues. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 3628–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogineni, V.; Hamann, M.T. Marine natural product peptides with therapeutic potential: Chemistry, biosynthesis, and pharmacology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 81–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltrap, A.M.; Cergol, K.M.; Pang, A.; Britton, W.J.; Payne, R.J. Total synthesis of fellutamide B and deoxy-fellutamides B., C, and D. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 2382–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogle, L.M.; Gerwick, W.H. Somocystinamide A, a novel cytotoxic disulfide dimer from a Fijian marine cyanobacterial mixed assemblage. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, S.; Oz, F.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Carne, A.; Agyei, D. Production, characterization, and potential applications of lipopeptides in food systems: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves Filho, R.A.; Stark, S.; Westermann, B.; Wessjohann, L.A. The multicomponent approach to N-methyl peptides: Total synthesis of antibacterial (-)-viridic acid and analogues. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 2085–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, D.; Reguera, L.; Rennert, R.; Morgan, I.; Saoud, M.; Ricardo, M.G.; Valdés, L.; Coro-Bermello, J.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Rivera, D.G. Exploration of the Tertiary Amide Chemical Space of Dolastatin 15 Analogs Reveals New Insights into the Structure-Anticancer Activity Relationship. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockert, J.C.; Blázquez-Castro, A.; Cañete, M.; Horobin, R.W.; Villanueva, A. MTT assay for cell viability: Intracellular localization of the formazan product is in lipid droplets. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 2018, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmedat, A.N.; Morejon, M.C.; Rivera, D.G.; Pantelic, N.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluderovic, G.N. Cyclic Lipopeptides as Selective Anticancer Agents: In vitro Efficacy on B16F10 Mouse Melanoma Cells. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmedat, A.N.; Morejón, M.C.; Rivera, D.G.; Pantelić, N.Đ.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluđerović, G.N. In vitro anticancer studies of a small library of cyclic lipopeptides against the human cervix adenocarcinoma HeLa cells. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2024, 89, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małaczewska, J.; Kaczorek-Łukowska, E.; Kazuń, B. High cytotoxicity of betulin towards fish and murine fibroblasts: Is betulin safe for nonneoplastic cells? BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.W.; Austin, S.; Gamma, M.; Cheff, D.M.; Lee, T.D.; Wilson, K.M.; Johnson, J.; Travers, J.; Braisted, J.C.; Guha, R.; et al. Cytotoxic Profiling of Annotated and Diverse Chemical Libraries Using Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. SLAS Discov. 2020, 25, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aaraj, L.; Hayar, B.; Jaber, Z.; Saad, W.; Saliba, N.A.; Darwiche, N.; Ghaddar, T. The Effect of Different Ester Chain Modifications of Two Guaianolides for Inhibition of Colorectal Cancer Cell Growth. Molecules 2021, 26, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, K.A.; Lomax, J.E.; Raines, R.T. Cytosolic Delivery of Proteins by Bioreversible Esterification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14396–14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Deng, H.; Li, X.; Quan, Z.S. Application of Amino Acids in the Structural Modification of Natural Products: A Review. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 650569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifian, H.; Maharani, R.; Megantara, S.; Gazzali, A.M.; Muchtaridi, M. Amino-Acid-Conjugated Natural Compounds: Aims, Designs and Results. Molecules 2022, 27, 7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Lou, Y.; Wu, F. Improved Intracellular Delivery of Polyarginine Peptides with Cargoes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 2636–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajstura, M.; Halicka, H.D.; Pryjma, J.; Darzynkiewicz, Z. Discontinuous fragmentation of nuclear DNA during apoptosis revealed by discrete “sub-G1” peaks on DNA content histograms. Cytom. A 2007, 71, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, R.; Tantry, I.Q.; Ahmad, W.; Siddiqui, S.; Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Moinuddin; Hassan, M.I.; Habib, S.; et al. Apoptosis: A Comprehensive Overview of Signaling Pathways, Morphological Changes, and Physiological Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2024, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R. Caspases and Their Substrates. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2022, 14, a041012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelić, N.; Božić, B.; Zmejkovski, B.B.; Banjac, N.R.; Dojčinović, B.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluđerović, G.N. In Vitro Evaluation of Antiproliferative Properties of Novel Organotin (IV) Carboxylate Compounds with Propanoic Acid Derivatives on a Panel of Human Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2021, 26, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Virgilio, L.; Silva-Lucero, M.D.; Flores-Morelos, D.S.; Gallardo-Nieto, J.; Lopez-Toledo, G.; Abarca-Fernandez, A.M.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Luna-Muñoz, J.; Montiel-Sosa, F.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; et al. Autophagy: A Key Regulator of Homeostasis and Disease: An Overview of Molecular Mechanisms and Modulators. Cells 2022, 11, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.; de Oliveira, J.; da Silva Pontes, L.V.; de Souza Júnior, J.F.; Gonçalves, T.A.F.; Dantas, S.H.; de Almeida Feitosa, M.S.; Silva, A.O.; de Medeiros, I.A. ROS: Basic Concepts, Sources, Cellular Signaling, and its Implications in Aging Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1225578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S.M.; Sharma, N.S.; Karan, A.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Cordon, B.; Ma, B.; Xie, J. Nitric Oxide: Physiological Functions, Delivery, and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2303259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Ngai, S.C.; Goh, B.H.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; Chuah, L.H. Anticancer Activities of Surfactin and Potential Application of Nanotechnology Assisted Surfactin Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, S.; Zhao, X.; Shao, D.; Jiang, C.; Shi, J.; Sun, H. Potential of iturins as functional agents: Safe, probiotic, and cytotoxic to cancer cells. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5580–5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Feng, Y.Q.; Ren, J.; Jing, D.; Wang, C. Anti-tumor role of Bacillus subtilis fmbJ-derived fengycin on human colon cancer HT29 cell line. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Liu, Y.; Luesch, H. Systematic Chemical Mutagenesis Identifies a Potent Novel Apratoxin A/E Hybrid with Improved in Vivo Antitumor Activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janek, T.; Krasowska, A.; Radwańska, A.; Łukaszewicz, M. Lipopeptide biosurfactant pseudofactin II induced apoptosis of melanoma A 375 cells by specific interaction with the plasma membrane. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrasidlo, W.; Mielgo, A.; Torres, V.A.; Barbero, S.; Stoletov, K.; Suyama, T.L.; Klemke, R.L.; Gerwick, W.H.; Carson, D.A.; Stupack, D.G. The marine lipopeptide somocystinamide A triggers apoptosis via caspase 8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2313–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ondeyka, J.; Harris, G.H.; Zink, D.; Kahn, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bills, G.; Platas, G.; Wang, W.; Szewczak, A.A.; et al. Isolation, structure, and biological activities of Fellutamides C and D from an undescribed Metulocladosporiella (Chaetothyriales) using the genome-wide Candida albicans fitness test. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.G.; Dachavaram, S.S.; Reddy, B.R.; Kalyankar, K.B.; Rajan, W.D.; Kootar, S.; Kumar, A.; Das, S.; Chakravarty, S. Fellutamide B Synthetic Path Intermediates with in Vitro Neuroactive Function Shows Mood-Elevating Effect in Stress-Induced Zebrafish Model. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10534–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, G.; Bharti, R.; Das, A.K.; Sen, R.; Mandal, M. Resensitization of Akt Induced Docetaxel Resistance in Breast Cancer by ‘Iturin A’ a Lipopeptide Molecule from Marine Bacteria Bacillus megaterium. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z. Nonribosomal peptide synthase gene clusters for lipopeptide biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis 916 and their phenotypic functions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, T.; Aoki, R.; Hori, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Yoshida, K.I.; Taoka, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Yasueda, H.; Kondo, A.; Hasunuma, T. High-throughput evaluation of hemolytic activity through precise measurement of colony and hemolytic zone sizes of engineered Bacillus subtilis on blood agar. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2024, 9, bpae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubrich, F.; Bösch, N.M.; Chepkirui, C.; Morinaka, B.I.; Rust, M.; Gugger, M.; Robinson, S.L.; Vagstad, A.L.; Piel, J. Ribosomally derived lipopeptides containing distinct fatty acyl moieties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113120119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Herradura, P.; Pearson, A.; Mesleh, M.F.; Mascio, C.T.; Howland, K.; Steenbergen, J.; Thorne, G.M.; et al. Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of a Series of Semisynthetic Lipopeptides Leading to the Discovery of Surotomycin, a Novel Cyclic Lipopeptide Being Developed for the Treatment of Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5137–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Dai, X.; Qin, M.; Guo, Z. Identification of an amphipathic peptide sensor of the Bacillus subtilis fluid membrane microdomains. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Rational strain improvement for surfactin production: Enhancing the yield and generating novel structures. Microb. Cell. Fact. 2019, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Gao, L.; Bie, X.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Lu, F.; Zhao, H. Identification of novel surfactin derivatives from NRPS modification of Bacillus subtilis and its antifungal activity against Fusarium moniliforme. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.; Kumagawa, E.; Kamata, K.; Ago, H.; Sakai, N.; Hasunuma, T.; Taoka, N.; Ohta, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Engineering of acyl ligase domain in non-ribosomal peptide synthetases to change fatty acid moieties of lipopeptides. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fernandez, K.X.; Vederas, J.C.; Gänzle, M.G. Composition and activity of antifungal lipopeptides produced by Bacillus spp. in daqu fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2023, 111, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, D.; Phelan, A.; Murphy, C.D.; Cobb, S.L. Fengycin A Analogues with Enhanced Chemical Stability and Antifungal Properties. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4672–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théatre, A.; Cano-Prieto, C.; Bartolini, M.; Laurin, Y.; Deleu, M.; Niehren, J.; Fida, T.; Gerbinet, S.; Alanjary, M.; Medema, M.H.; et al. The Surfactin-Like Lipopeptides From Bacillus spp.: Natural Biodiversity and Synthetic Biology for a Broader Application Range. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 623701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolin, C.F.; Kumar, P.S.; Ngueagni, P.T. A review on new aspects of lipopeptide biosurfactant: Types, production, properties and its application in the bioremediation process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahidinasab, M.; Adiek, I.; Hosseini, B.; Akintayo, S.O.; Abrishamchi, B.; Pfannstiel, J.; Henkel, M.; Lilge, L.; Voegele, R.T.; Hausmann, R. Characterization of Bacillus velezensis UTB96, Demonstrating Improved Lipopeptide Production Compared to the Strain, B. velezensis FZB42. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, R.; Chowdhury, S.M.; Marshall, S.R.; Gneid, H.; Busschaert, N. Increasing membrane permeability of carboxylic acid-containing drugs using synthetic transmembrane anion transporters. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 13122–13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, T.; Mu, L.; Yang, X. Synthesis and biological activities of novel mitochondria-targeted artemisinin ester derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 39, 127912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J.; Edraki, N.; Kamat, S.P.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Kayani, Z.; Mirzaei, H.H.; Miri, R.; Erfani, N.; Nejati, M.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S.; et al. Long Chain Alkyl Esters of Hydroxycinnamic Acids as Promising Anticancer Agents: Selective Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2017, 65, 7228–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.X.; Chen, M.H.; Hu, X.Y.; Ye, R.R.; Tan, C.P.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Ester-Modified Cyclometalated Iridium (III) Complexes as Mitochondria-Targeting Anticancer Agents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-Zardini, H.; Saberian, E.; Jenča, A.; Ghanipour-Meybodi, R.; Jenča, A.; Petrášová, A.; Jenčová, J. From defense to offense: Antimicrobial peptides as promising therapeutics for cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1463088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, A.; Martínez, M.; Noguera, M.E.; Augusto, M.T.; Disalvo, A.; Santos, N.C.; Semorile, L.; Maffía, P.C. Role of amphipathicity and hydrophobicity in the balance between hemolysis and peptide-membrane interactions of three related antimicrobial peptides. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 141, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, X.; Kong, F.; Chen, P.; Pan, G. Improving cellular uptake of therapeutic entities through interaction with components of cell membrane. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.; Bellavita, R.; Braccia, S.; Galdiero, S. Hydrophobicity: The door to drug delivery. J. Pept. Sci. 2024, 30, e3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-García, C.; Colomer, I. New antimicrobial self-assembling short lipopeptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 6797–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamley, I.W. Lipopeptides: From self-assembly to bioactivity. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8574–8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocasio-Malavé, C.; Donate, M.J.; Sánchez, M.M.; Sosa-Rivera, J.M.; Mooney, J.W.; Pereles-De León, T.A.; Carballeira, N.M.; Zayas, B.; Vélez-Gerena, C.E.; Martínez-Ferrer, M.; et al. Synthesis of novel 4-Boc-piperidone chalcones and evaluation of their cytotoxic activity against highly-metastatic cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davarzani, Z.; Salehi, P.; Asghari, S.M.; Bararjanian, M.; Hamrahi Mohsen, A.; Dehghan Harati, H. Design, Synthesis, and Functional Studies on Noscapine and Cotarnine Amino Acid Derivatives as Antitumor Agents. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 45502–45509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.R.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Fang, K.; Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Xue, N.N.; Chen, M.; Guo, W.B.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of podophyllotoxin derivatives as selective antitumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 155, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Corona, A.V.; Valencia-Espinosa, I.; González-Sánchez, F.A.; Sánchez-López, A.L.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Garcia-Varela, R. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Cytotoxic Activity of Phenolic Compound Family Extracted from Raspberries (Rubus idaeus): A General Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaycı, B.; Şimşek Özek, N.; Aysin, F.; Özbek, H.; Kazaz, C.; Önal, M.; Güvenalp, Z. Evaluation of cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of the extracts and phenolic compounds of Astragalus globosus Vahl and Astragalus breviflorus DC. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, J.; Aboul-Enein, B.H.; Duchnik, E.; Marchlewicz, M. Antioxidative properties of phenolic compounds and their effect on oxidative stress induced by severe physical exercise. J. Physiol. Sci. 2022, 72, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kaushal, N.; Saleth, L.R.; Ghavami, S.; Dhingra, S.; Kaur, P. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and autophagy: Balancing the contrary forces in spermatogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Martin, V.; Plaza-Calonge, M.D.C.; Soriano-Lerma, A.; Ortiz-Gonzalez, M.; Linde-Rodriguez, A.; Perez-Carrasco, V.; Ramirez-Macias, I.; Cuadros, M.; Gutierrez-Fernandez, J.; Murciano-Calles, J.; et al. Gallic Acid: A Natural Phenolic Compound Exerting Antitumoral Activities in Colorectal Cancer via Interaction with G-Quadruplexes. Cancers 2022, 14, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuelli, L.; Benvenuto, M.; Di Stefano, E.; Mattera, R.; Fantini, M.; De Feudis, G.; De Smaele, E.; Tresoldi, I.; Giganti, M.G.; Modesti, A.; et al. Curcumin blocks autophagy and activates apoptosis of malignant mesothelioma cell lines and increases the survival of mice intraperitoneally transplanted with a malignant mesothelioma cell line. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 34405–34422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghtaderi, H.; Sepehri, H.; Attari, F. Combination of arabinogalactan and curcumin induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells in vitro and inhibits tumor growth via overexpression of p53 level in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 88, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori-Daloii, M.R.; Momeny, M.; Yousefi, M.; Shirazi, F.G.; Yaseri, M.; Motamed, N.; Kazemialiakbar, N.; Hashemi, S. Multifaceted preventive effects of single agent quercetin on a human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line (PC-3): Implications for nutritional transcriptomics and multi-target therapy. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganova, A.V.; Petrov, A.O.; Shastin, A.V.; Filatova, N.V.; Mumyatova, V.A.; Tarasov, A.E.; Lolaeva, A.V.; Malkov, G.V.J.C. Synthesis, Antibacterial Activity, and Cytotoxicity of Azido-Propargyloxy 1, 3, 5-Triazine Derivatives and Hyperbranched Polymers. Chemistry 2023, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kumar Thatipamula, R.; Narsimha, S.; Battula, K.; Chary, V.R.; Mamidala, E.; Reddy, N.V. Synthesis, anticancer and antibacterial evaluation of novel (isopropylidene) uridine-[1, 2, 3] triazole hybrids. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Hu, J.; Xu, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S. Sodium azide induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in PC12 cells through Pgc-1α-associated signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.H.; Wang, A.H.; Wang, C.L.; Mao, D.Z.; Lu, M.F.; Cui, Y.Q.; Jiao, R.Z. Surfactin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells through a ROS/JNK-mediated mitochondrial/caspase pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 183, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Bae, H.J.; Yi, H.; Yoon, S.H.; Koo, B.S.; Kwon, M.; Cho, J.Y.; Lee, C.E.; et al. Surfactin from Bacillus subtilis displays anti-proliferative effect via apoptosis induction, cell cycle arrest and survival signaling suppression. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.T.; Wee, Y.; Cheng, H.C.; Wu, C.Z.; Chen, Y.L.; Tuan, V.P.; Liu, J.F.; Lin, W.N.; Lee, I.T. Surfactin induces autophagy, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yan, L.; Xu, X.; Jiang, C.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lei, S.; Shao, D.; Huang, Q. Potential of Bacillus subtilis lipopeptides in anti-cancer I: Induction of apoptosis and paraptosis and inhibition of autophagy in K562 cells. AMB Express 2018, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, X.; Lei, S.; Shao, D.; Jiang, C.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lei, S.; Sun, H.; et al. Iturin A-like lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis trigger apoptosis, paraptosis, and autophagy in Caco-2 cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 6414–6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, G.; Bharti, R.; Dhanarajan, G.; Das, S.; Dey, K.K.; Kumar, B.N.; Sen, R.; Mandal, M. Marine lipopeptide Iturin A inhibits Akt mediated GSK3β and FoxO3a signaling and triggers apoptosis in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Lv, Y.; Lv, F.; Lu, Z. Fengycin inhibits the growth of the human lung cancer cell line 95D through reactive oxygen species production and mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Anticancer Drugs 2013, 24, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Ośko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczyńska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress-A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajare, S.N.; Subramanian, M.; Gautam, S.; Sharma, A. Induction of apoptosis in human cancer cells by a Bacillus lipopeptide bacillomycin D. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, S. Utilization of the Ugi Four-Component Reaction for the Synthesis of Lipophilic Peptidomimetics as Potential Antimicrobials; Martin Luther University: Halle, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krajnović, T.; Pantelić, N.; Wolf, K.; Eichhorn, T.; Maksimović-Ivanić, D.; Mijatović, S.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluđerović, G.N. Anticancer Potential of Xanthohumol and Isoxanthohumol Loaded into SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica Particles against B16F10 Melanoma Cells. Materials 2022, 15, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | B16F10 | HeLa | HT–29 | PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.5 ± 1.7 | 16.0 ± 1.1 | 17.1 ± 4.2 | 14.8 ± 3.5 |

| 3 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 12.0 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 0.5 |

| 8 | 6.8 ± 0.4 | 16.7 ± 3.9 | 10.7± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.4 |

| 17 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| 45 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 7.8 ± 0.6 |

| 46 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.4 |

| 47 | 11.5 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 1.3 | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.3 |

| 48 | >80 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 8.6 ± 1.5 | >80 |

| 53 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 19.2 ± 1.8 | 10.3 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 0.5 |

| 55 | 9.9 ± 0.1 | 15.4 ± 0.6 | 22.9 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 0.5 |

| 58 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.5 |

| 59 | 11.1 ± 1.2 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 11.8 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 0.2 |

| Surfactin | 40.4 ± 0.3 [35] | 76.2 ± 1.6 [36] | 46.1 ± 2.6 | 49.4 ± 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hmedat, A.; Stark, S.; Budragchaa, T.; Pantelić, N.Đ.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluđerović, G.N. Synthetic Linear Lipopeptides and Lipopeptoids Induce Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress: In Vitro Cytotoxicity and SAR Evaluation Against Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121840

Hmedat A, Stark S, Budragchaa T, Pantelić NĐ, Wessjohann LA, Kaluđerović GN. Synthetic Linear Lipopeptides and Lipopeptoids Induce Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress: In Vitro Cytotoxicity and SAR Evaluation Against Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121840

Chicago/Turabian StyleHmedat, Ali, Sebastian Stark, Tuvshinjargal Budragchaa, Nebojša Đ. Pantelić, Ludger A. Wessjohann, and Goran N. Kaluđerović. 2025. "Synthetic Linear Lipopeptides and Lipopeptoids Induce Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress: In Vitro Cytotoxicity and SAR Evaluation Against Cancer Cell Lines" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121840

APA StyleHmedat, A., Stark, S., Budragchaa, T., Pantelić, N. Đ., Wessjohann, L. A., & Kaluđerović, G. N. (2025). Synthetic Linear Lipopeptides and Lipopeptoids Induce Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress: In Vitro Cytotoxicity and SAR Evaluation Against Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121840