1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the causative agent of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), a severe and highly contagious disease marked by a substantial mortality rate. According to the 2023 report by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), in the neighborhood of 1.3 million individuals were newly infected with HIV, and approximately 39.9 million people and 630,000 deaths from AIDS-related illnesses (

https://www.unaids.org, accessed on 1 January 2025). Traditionally, vaccination has proven to be the most potent strategy in preventing infectious diseases. However, despite extensive and relentless research endeavors, the scientific community has yet to develop a safe and efficacious vaccine against HIV [

1]. Consequently, the reliance on pharmacological interventions, particularly highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), stands as the primary strategy for the management of AIDS [

2]. While significant strides have been made in improving treatment options, the ongoing quest for a definitive therapeutic solution remains an urgent and critical priority.

Currently, HIV therapeutics approved by FDA encompass reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), integrase inhibitors, capsid inhibitors (e.g., lenacapavir), and entry inhibitors. [

3]. One kind of entry inhibitor known as a fusion inhibitor (FI) functions by preventing the early stage for infection fusion. As the first peptide fusion inhibitor, Enfuvirtide (T20) received FDA approval in 2003 to treat HIV-1 infections [

4]. In recent years, Sifuvirtide received approval for clinical phase III trials, and Albuvirtide received approval in China [

5]. It implies that the use of peptide-based fusion inhibitors in HIV-1 treatment is becoming increasingly popular.

The membrane fusion process of HIV-1 with its host cell, a key step in viral entry mediated by the envelope glycoprotein, has been meticulously characterized (

Figure 1). The envelope glycoprotein (Env), which consists of the transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 and the surface glycoprotein gp120, plays a central role in mediating HIV-1 infection of target cells. Within gp41, the N-terminal heptad repeat (NHR) and C-terminal heptad repeat (CHR) regions play critical roles [

6]. Initially, gp120 binds to the CD4 receptor on host cell membrane, followed by interaction with either the CXCR4 or CCR5 co-receptors. This triggers the gp41 region exposure, previously concealed within gp120, and initiates a cascade of conformational changes. The NHR forms a coiled-coil core through interactions among three molecules, known as the N-Trimer, which then facilitates the anti-parallel binding of three CHR molecules to its hydrophobic grooves, resulting in the formation of the six-helix bundle (6-HB) [

7]. N36 is a well-characterized peptide fragment corresponding to the NHR region of gp41 (residues 546–581), while C34 is a peptide derived from the CHR region (residues 628–661). These two peptides spontaneously associate in vitro to form a stable 6-HB structure, serving as a canonical model for studying Env-mediated fusion and evaluating the activity of fusion inhibitors. The fusion pore hinges on this structural transition, which bridges the viral envelope with the host cell membrane and ultimately facilitates membrane fusion. Consequently, the 6-HB represents not only a pivotal therapeutic target but also the primary molecular source for designing HIV-1 peptide-based fusion inhibitors. By targeting the 6-HB intermediate or directly disrupting 6-HB formation, peptide-based fusion inhibitors can effectively block HIV-1 entry into host cells, offering a promising therapeutic strategy against HIV-1 infection [

8].

It is worth noting that, within 6-HB structural arrangement, the CHR domains are partitioned into two distinct regions: a buried hydrophobic interface involved in binding and exposed hydrophilic regions accessible to solvent [

9]. Structural studies have revealed a remarkable tolerance for sequence variability in the CHR motifs of the HIV-1 6-HB, provided the amphiphilic nature of the helices driving the coiled-coil assembly remains intact. Through the implementation of approaches such as salt bridges, helix-favoring amino acids, and hydrophobic mutations in buried residues, researchers have developed α-helix-constrained C-peptides [

8,

10]. These peptides exhibit significantly enhanced bundle stability compared to their parent CHR regions, even though nearly 50% of the native residues were replaced. Furthermore, incorporating membrane-anchored small molecules into peptide tails is a further method to enhance the antiviral ability of peptide inhibitors. Recent research has demonstrated that lipid-conjugated C-peptides exhibit significantly increased α-helicity and enhanced binding capability to NHR region [

8].

Capitalizing on the modifiable nature of the 6-HB α-helical structure and the design advantages of artificial peptides, we engineered novel artificial peptides by replicating the CHR helix topology through integration of custom-engineered amphipathic α-helical motifs and a lipid-targeting membrane anchor. As a result, the top-performing compound, EK35S-Palm, effectively targets the NHR region to prevent endogenous 6-HB formation, exhibiting robust antiviral efficacy against HIV-1, while demonstrating better metabolic stability than T20. This artificial-peptide design strategy holds significant promise for developing novel antivirals targeting the HIV-1 membrane fusion process.

2. Design

In the heptad-repeat region, understanding molecular interactions—such as hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonding—is critical, as these non-covalent forces drive the 6-HB formation [

11]. Artificial peptides can be rationally designed according to the CHR domain distribution rules, exhibiting excellent anti-HIV-1 activity by binding to the NHR domain through non-covalent interactions. Building on this, Shi et al. [

12] introduced partial natural CHR sequences at the 5HR, viz. (AEELAKK)

5, N-terminus and mutated (

a,

d) positions within the heptad-repeat rules, resulting in the artificial peptide PBD-m4HR, which exhibited comparable activity to natural C-peptides. This suggests that rule-based mutagenesis introduces key residues that enable the α-helical artificial peptides, which have no homology to the HIV-1 envelope protein, to mimic the CHR active conformation and enhance binding with the NHR region to exert effective anti-HIV-1 activity. Thus, the heptad-repeat rules provide crucial insights for our first round in designing artificial peptides.

Covalent bonding of lipid molecules such as fatty acids, cholesterol, and pentacyclic triterpenoids on peptides enhances the lipophilicity, which can be anchored to “lipid rafts” mediating the viral membrane fusion, effectively increasing the local drug concentration near the target region [

13,

14]. Research demonstrates that multiple peptide-conjugated fusion inhibitors, such as C34-conjugated cholesterol, DP20-conjugated fatty acids, and P26-conjugated pentacyclic tricyclic compounds, exhibit not only significantly enhanced anti-HIV-1 activity but also improved pharmacokinetic properties [

13,

15,

16]. For de novo-designed amphiphilic α-helical peptides, the introduction of membrane-anchored small molecules can further stabilize the helical active conformation and enhance the antiviral activity by anchoring to the membrane fusion region. Therefore, the membrane-anchor strategies are the core tactic in our second round of optimizing artificial peptides.

Based on the heptad-repeat rules, the first round of artificial-peptide design was conducted as follows: (i) Alanine (Ala) residues at the (

a,

e) positions in (AEELAKK)

n were mutated to Isoleucine (Ile) residues to provide hydrophobic interaction encapsulated in the NHR pocket domain [

17]; (ii) the 6-HB crystal structure reveals that the CHR region hovering outside interacts with the NHR through key residues at the (

a,

d,

e) positions, while the residues at the (

b,

c,

f,

g) positions are the non-target binding regions [

18]. Therefore, we introduced double E-K salt bridges at the (

b,

f) and (

c,

g) positions to stabilize the artificial helix structure, immobilized hydrophobic amino acid residues at (

a,

d) positions, and introduced nonpolar, polar, and aromatic amino acid residues at (

e) positions, respectively, in order to search for the strongest binding to the target (e.g., hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, etc.). Through the first design round, we proposed to obtain the most appropriate artificial-peptide sequence matching the target with potential anti-HIV-1 activity (

Table 1).

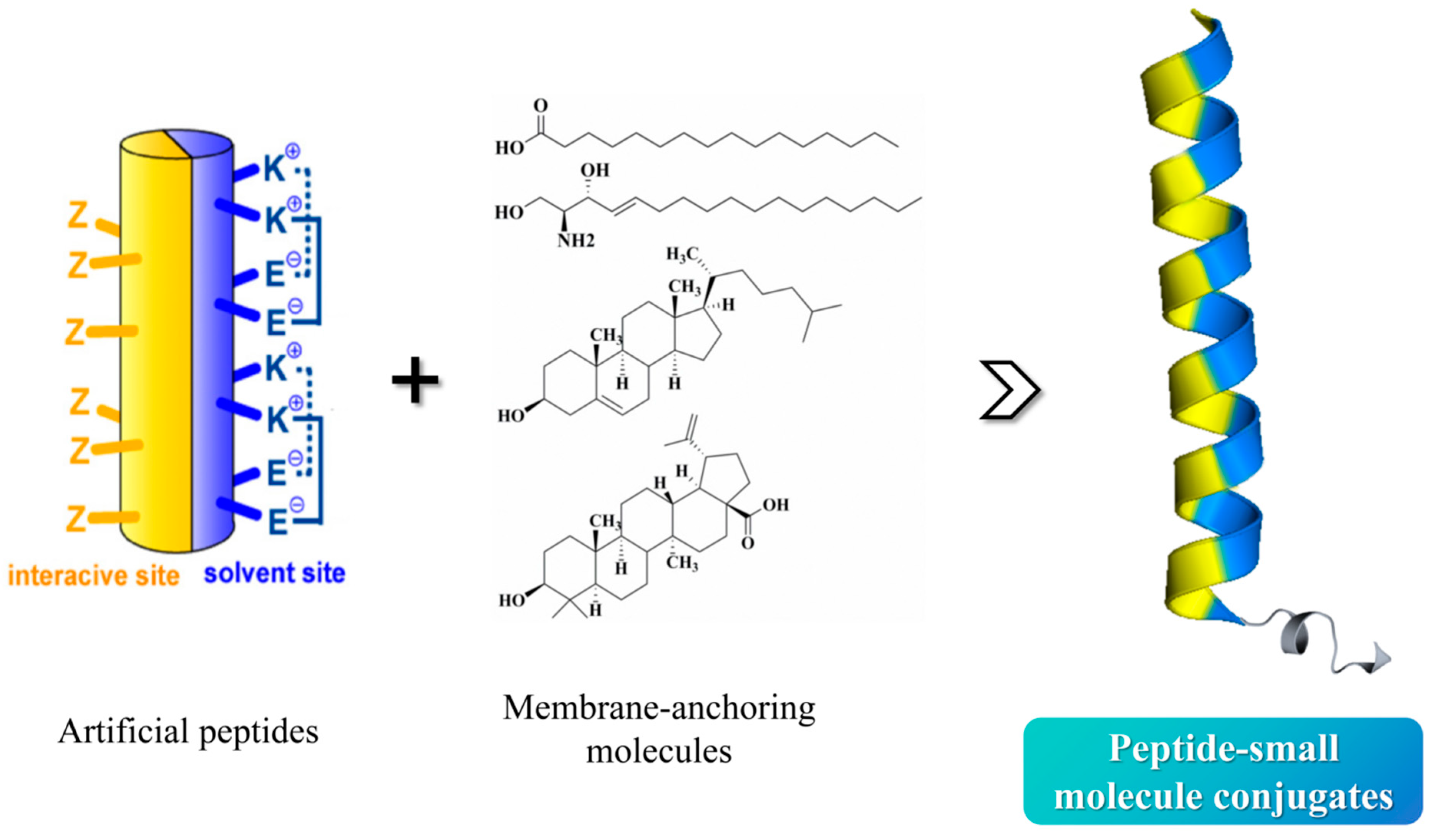

For the second round of artificial-peptide design, in an attempt to improve the peptide membrane affinity to achieve targe enrichment effect, we chose oleanolic acid, cholesterol, and palmitic acid as the membrane-anchoring molecules to modify the above peptides (

Figure 2): (i) Pep-OApc: the carboxyl group at the C3 position of oleanolic acid was protected by allyl group and the hydroxyl group at the C28 position was protected by pentynyl group, named OApc, and the azide group was strategically incorporated at the peptide N-terminus, the Pep-OApc was finally obtained via click chemistry; (ii) Pep-Chol: the Cys residue was introduced at the peptide C-terminus, and the hydroxyl group at the C3 position of cholesterol was condensed with bromoacetic acid to obtain cholesteryl bromoacetate. The bromine atom attacks the Cys sulfhydryl group of the peptide to obtain the Pep-Chol; (iii) Pep-palm: palmitic acid is able to condense with the peptide on the solid phase resin to obtain the Pep-palm. We intend to carry out HIV-1 inhibitory activity screening and mechanism exploration on the above obtained peptide–small-molecule conjugates, aiming to identify novel anti-HIV-1 lead compounds, and finally to establish a mature and effective methodology to expedite the development of innovative peptide-based fusion inhibitors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Compounds Synthesis

All peptides, and EK35S-Palm, were synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase synthesis techniques. The synthesis was performed on Fmoc-protected rink amide resin with Fmoc-protected amino acids. Coupling reactions were carried out using O-benzotriazol-1-yl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU, GL Biochem, Shanghai, China), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt, GL Biochem, Shanghai, China), and diisopropylethylamine (DIEA, J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) solution. The Fmoc protective group was removed with 20% piperidine/DMF, and the resin was cleaved using a reagent mixture containing trifluoroacetic acid/m-cresol/thioanisole/water [5:0.2:0.2:0.1 (v/v/v/v)].

EK35S-OApc Synthesis [

16]: Briefly, the purified azido-peptide precursor (1.0 equiv, 0.005 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of H

2O, followed by the addition of triterpene derivatives (1.2 equiv, 0.006 mmol) dissolved in 1 mL of tert-butyl alcohol (J&K Scientific, Beijing, China). Subsequently, CuSO

4·5H

2O (J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) (1.0 equiv, 0.005 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) (5.0 equiv, 0.025 mmol) were added to the mixture, which was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The reaction progress was monitored by analytical RP-HPLC (Shimadzu analytical HPLC system, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

EK35S-Chol Synthesis [

20]: Briefly, 20 mg of the purified peptide precursor, which included a Cys residue added to the C-terminus via a β-alanine linker, was dissolved in 300 μL of DMSO (J&K Scientific, Beijing, China). To this solution, 1.5 mg of cholest-5-en-3-yl bromoacetate (J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) dissolved in 200 μL of tetrahydrofuran (THF, J&K Scientific, Beijing, China) was added, followed by the addition of 7 μL of DIEA. The mixture was stirred at room temperature, and the reaction progress was monitored by analytical RP-HPLC.

All crude peptides were purified using preparative RP-HPLC (Shimadzu preparative HPLC system, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), and the purity of the peptides was confirmed to be ≥95% by analytical RP-HPLC (Shimadzu analytical HPLC system, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The molecular weights of the compounds were characterized using Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS, Autoflex III, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

4.2. HIV-1 Env-Mediated Cell–Cell Fusion Assay [18]

Briefly, the fluorescent reagent Calcein AM (abcam, Shanghai, China) was used to label H9/HIV-1 IIIB cells (obtained from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region New Drug Screening Engineering Research Center in Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot, China). First, 2.5 μL of Calcein AM was used to stain 2 × 105 H9/HIV-1 IIIB cells. After labeling at 37 °C for 30 min, the cells were washed twice with PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and resuspended in fresh RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Next, 50 μL of diluted peptides and 50 μL of a mixture containing 2 × 105 H9/HIV-1 IIIB cells/mL were added to a 96-well cell culture plate and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, 1 × 105 MT-2 cells were added to the mixture and cultured at 37 °C for 2 h. The fused cells were quantified using an inverted fluorescence microscope. The IC50 values were calculated using CalcuSyn software (Version 2.0).

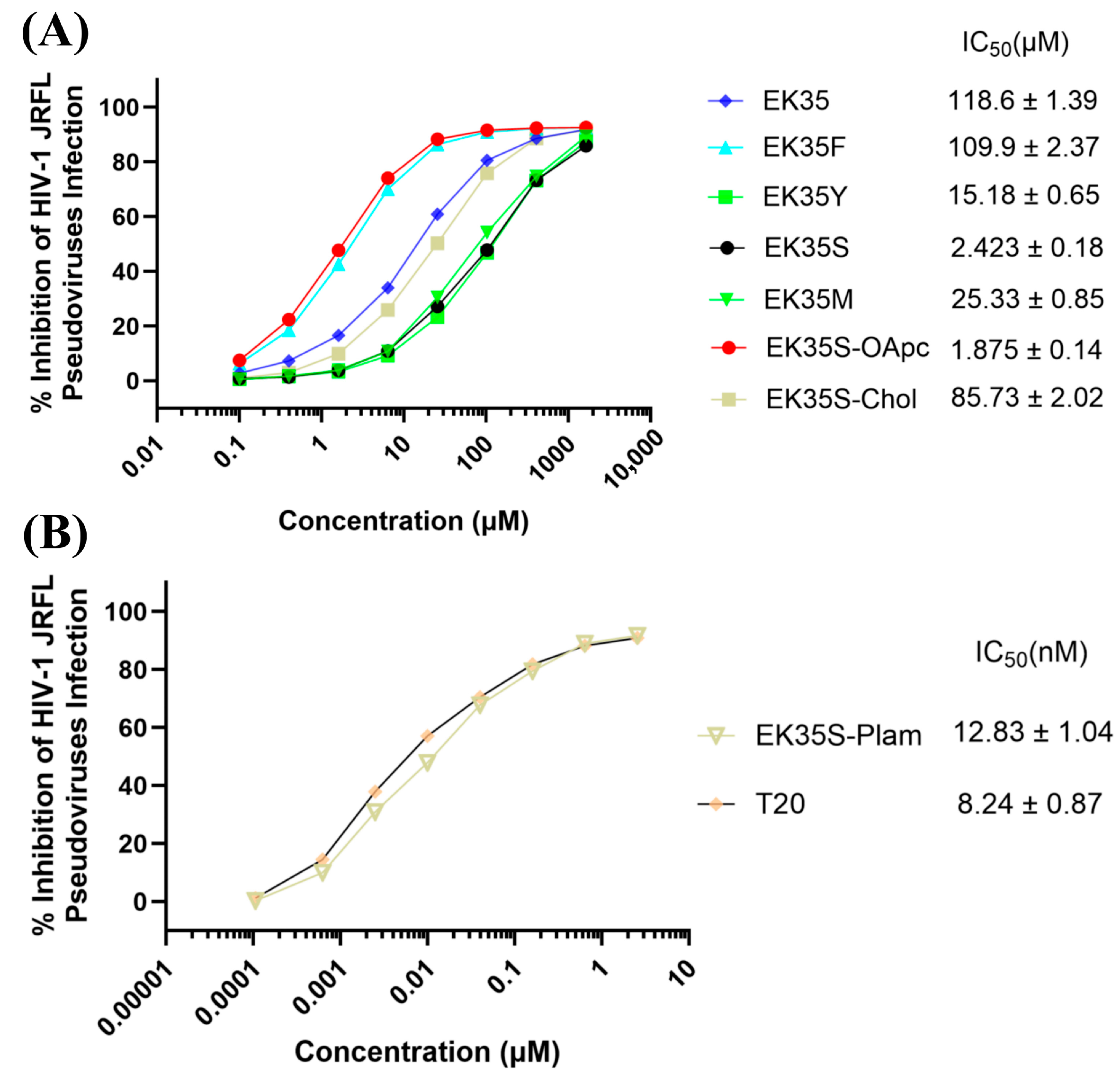

4.3. Neutralization Assay of HIV-1 Pseudovirus [21]

Briefly, U87 CD4+ CCR5+ cells (obtained from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region New Drug Screening Engineering Research Center in Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot, China) (1 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 h to allow cell adherence. Serial dilutions of the test peptides were prepared, and each dilution was mixed with the HIV-1 pseudovirus derived from the JFRL macrophagic strain (subtype B). After incubating the virus-peptide mixtures at 37 °C for 30 min to allow interaction, the mixtures were transferred to the pre-seeded U87 CD4+ CCR5+ cells. At 12 h post-infection, the culture medium was refreshed to remove unbound viruses and excess peptides. Forty-eight hours post-infection, the cells were lysed using Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and the luminescence intensity (reflecting luciferase activity) was quantified using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, E4030) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.4. Cytotoxicity Assays

Briefly, 100 μL of cell suspension (1 × 105 cells/mL) was dispensed into individual wells of a 96-well culture plate, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 h. Subsequently, 5 μL of serially diluted peptide preparations was added to each test well. Meanwhile, a blank control group (without peptide) and a positive control group (supplemented with 5 μL of 10% Triton X-100) were set up, and all groups were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Afterward, 10 μL of Cell Counting Kit-8 solution (Yeasen, Shanghai, China)was added to each well, and the plate was further incubated for 2 h. Finally, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

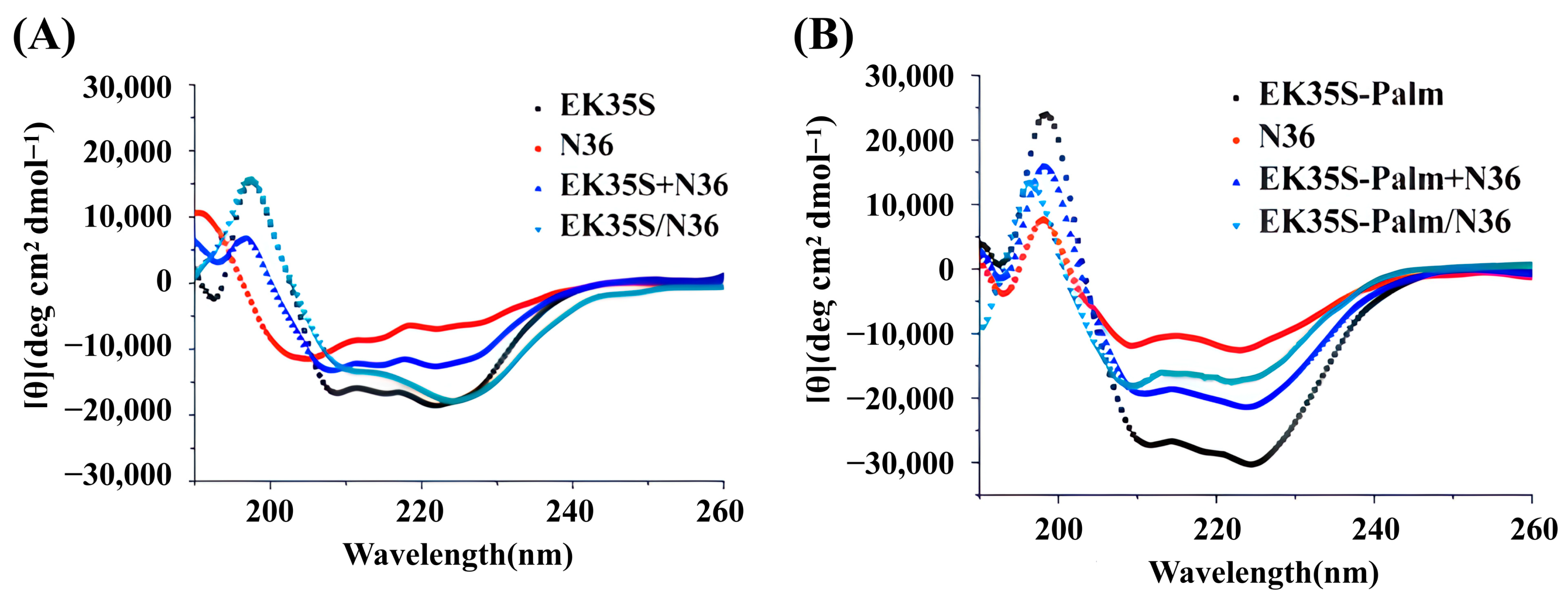

4.5. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy Analysis

Peptides, as well as their equimolar mixtures, were prepared at a final concentration of 20 μM in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The secondary structure of the peptides was analyzed using a circular dichroism (CD) spectrometer (J-1500, JASCO Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with the following parameters: 1.0 nm bandwidth, 180–260 nm wavelength range, 0.1 nm resolution, 0.2 nm data pitch, and 200 nm/min scanning speed.

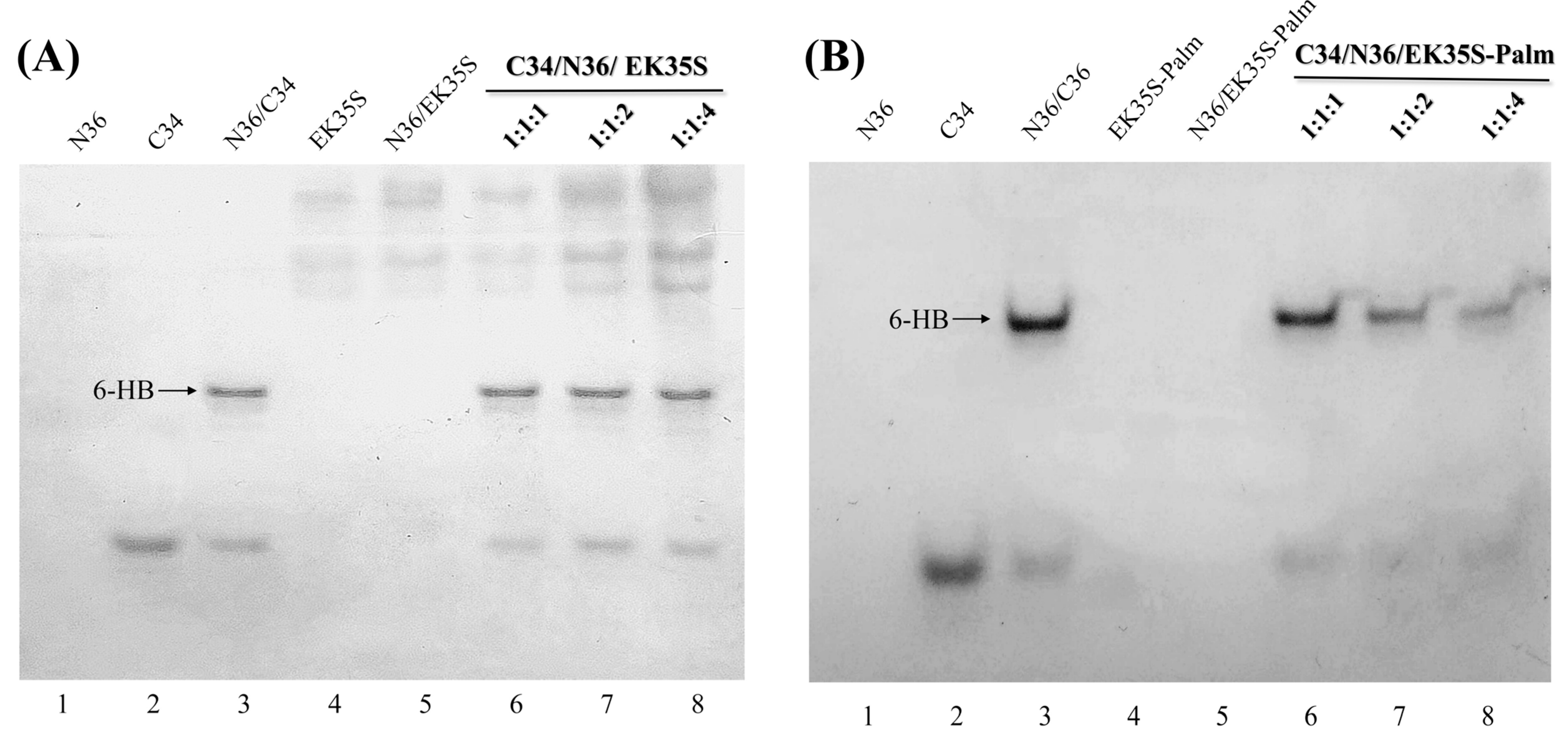

4.6. Methods for Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (N-PAGE)

Peptides, as well as their equimolar mixtures, were prepared at a final concentration of 100 μM in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the peptide solutions were mixed with methyl green loading buffer in a 1:1 ratio, and 20 μL of each sample was loaded into the wells of the gel. Gel electrophoresis was performed at room temperature, initially at a constant voltage of 90 V for 0.5 h, followed by 150 V for 2–3 h. The gels were then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 (Bio-Rad, Shanghai, China), and images were captured using the ChampGel 6000 Imaging System (Sage Creation Ltd., Beijing, China).

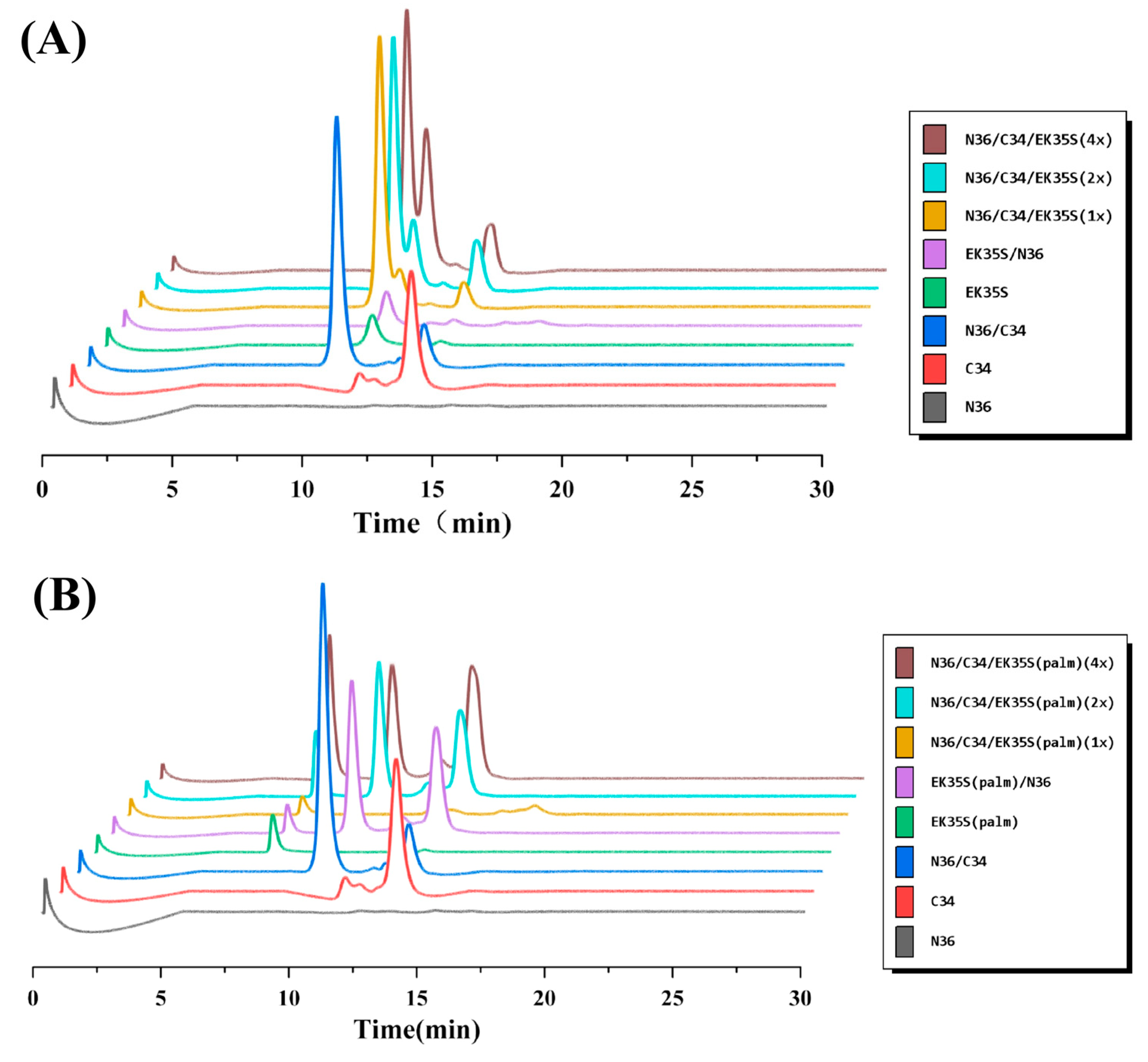

4.7. Methods for Size-Exclusion High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (SE-HPLC)

EK35S and EK35S-Palm, as well as their equimolar mixtures, were prepared at a final concentration of 100 μM in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The peptide or peptide mixture was then applied to a 300 mm × 7.8 mm Phenomenex BioSep-SEC-S2000 column, which was pre-equilibrated with PBS (pH 7.4). The elution was performed at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and the fractions were monitored at 210 nm.

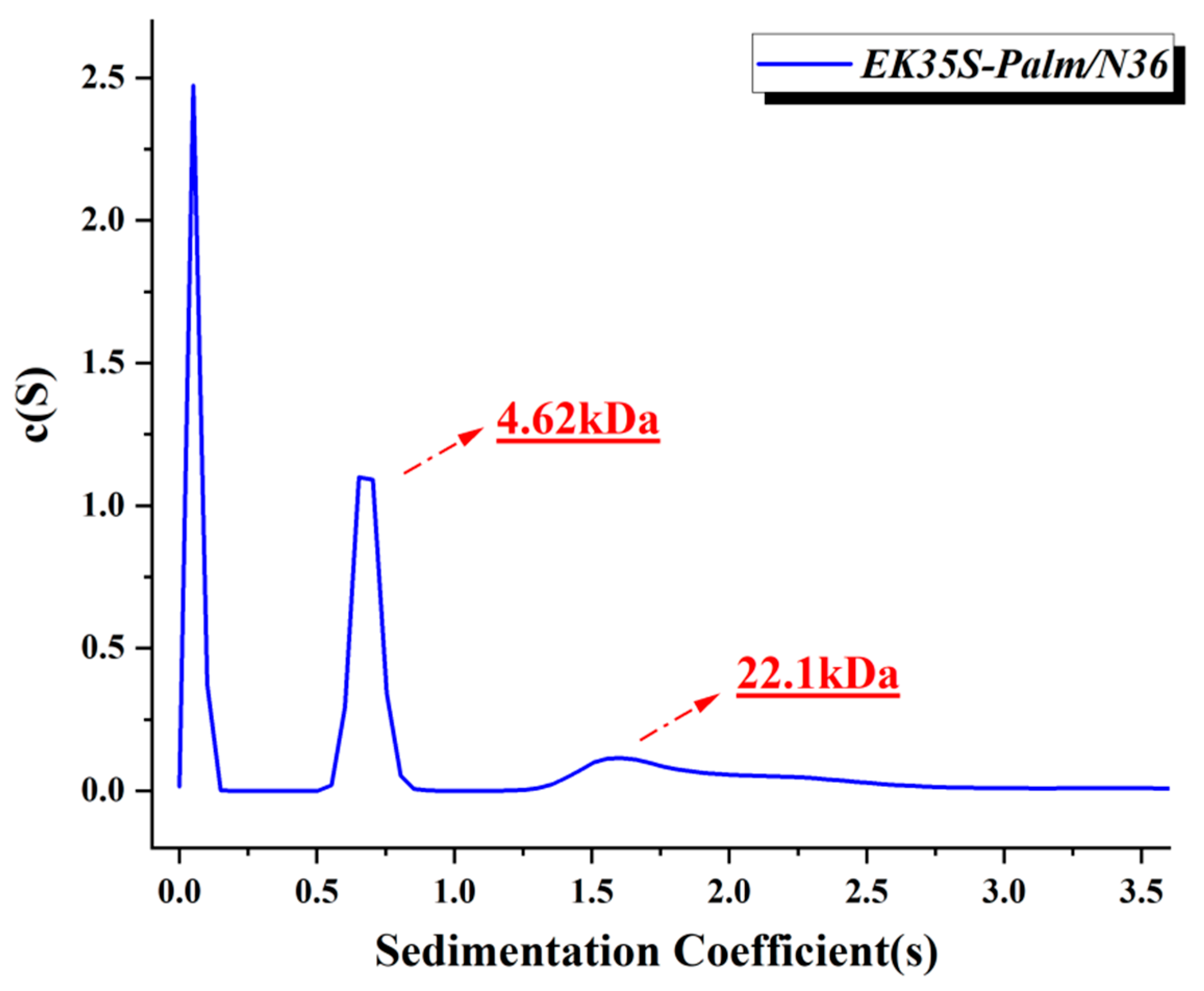

4.8. Methods for Sedimentation Velocity Analysis (SVA) [18]

An analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter ProteomeLab XL-A, Brea, CA, USA) was used for the sedimentation velocity analysis experiments. In brief, EK35S-palm was incubated with N36 in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 30 min. All samples were prepared at a final concentration of 200μM and were initially scanned at 5000 rpm for 10 min to identify the appropriate wavelength for data collection. Data were collected at 60,000 rpm at a wavelength of 280 nm. Sedimentation coefficient distribution, c(s), and molecular mass distribution, c(M), were calculated using the SEDFIT program (Beckman Coulter ProteomeLab XL-A, Brea, CA, USA).

4.9. Molecular Docking [18]

Molecular docking was performed using Schrödinger molecular modeling software (Schrödinger, New York, NY, USA). The initial monomer of the HIV-1 gp41 core structure was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1AIK), and each NHR region of the 6-HB was extracted as the receptor, designated as the ABC chain. The main structures of the EK35S and EK35S-Palm peptides, serving as ligands, were constructed using the Build Biopolymer from Sequence module with the OPLS_4 force field. Molecular docking was carried out using the Protein-Protein Docking (Piper) module in Schrödinger (Version 2021-2). The resulting docking conformations were analyzed and visualized using PyMOL software (Version 2.0).

4.10. Phase I Metabolic Stability Assay

Experiments were carried out using the Phase I Metabolic Stability Research Kit (IPHASE, Suzhou, China). Solution A in the kit was pre-incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and solution B was prepared from PBS (100 mM), the subject (or positive substrate), and liver microsomes. The above two were mixed and immediately placed in a 37 °C water bath for incubation. The incubation solution is quantitatively removed from the incubation system at preset time points (0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60 min), and an equal volume of termination solution is added. Each sample was run in parallel three times. The substrate remaining amount at each time point was determined by RP-HPLC (Shimadzu preparative HPLC system, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), the substrate remaining percentage was calculated, and the slope k was determined by linear regression analysis to calculate the Elimination half-life and Hepatic microsomal intrinsic clearance.