Decoding GuaB: Machine Learning-Powered Discovery of Enzyme Inhibitors Against the Superbug Acinetobacter baumannii

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Datasets Preprocessing

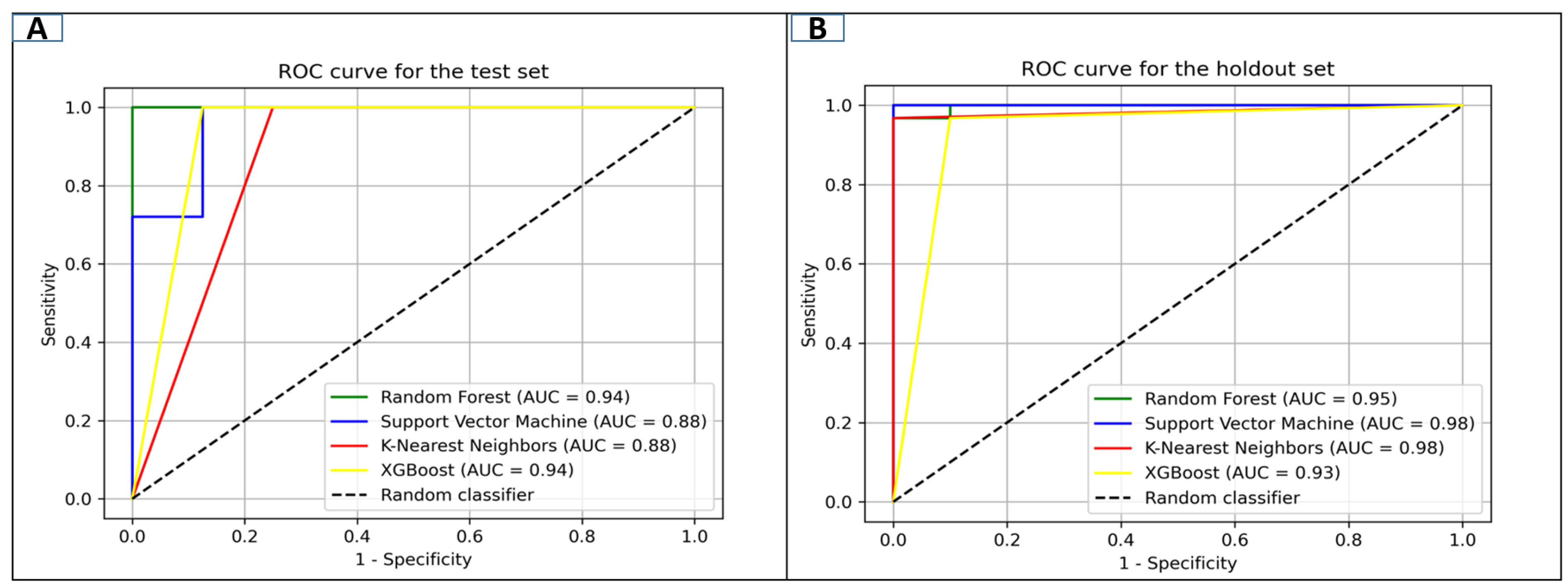

2.2. Model Development, Implementation, and Validation

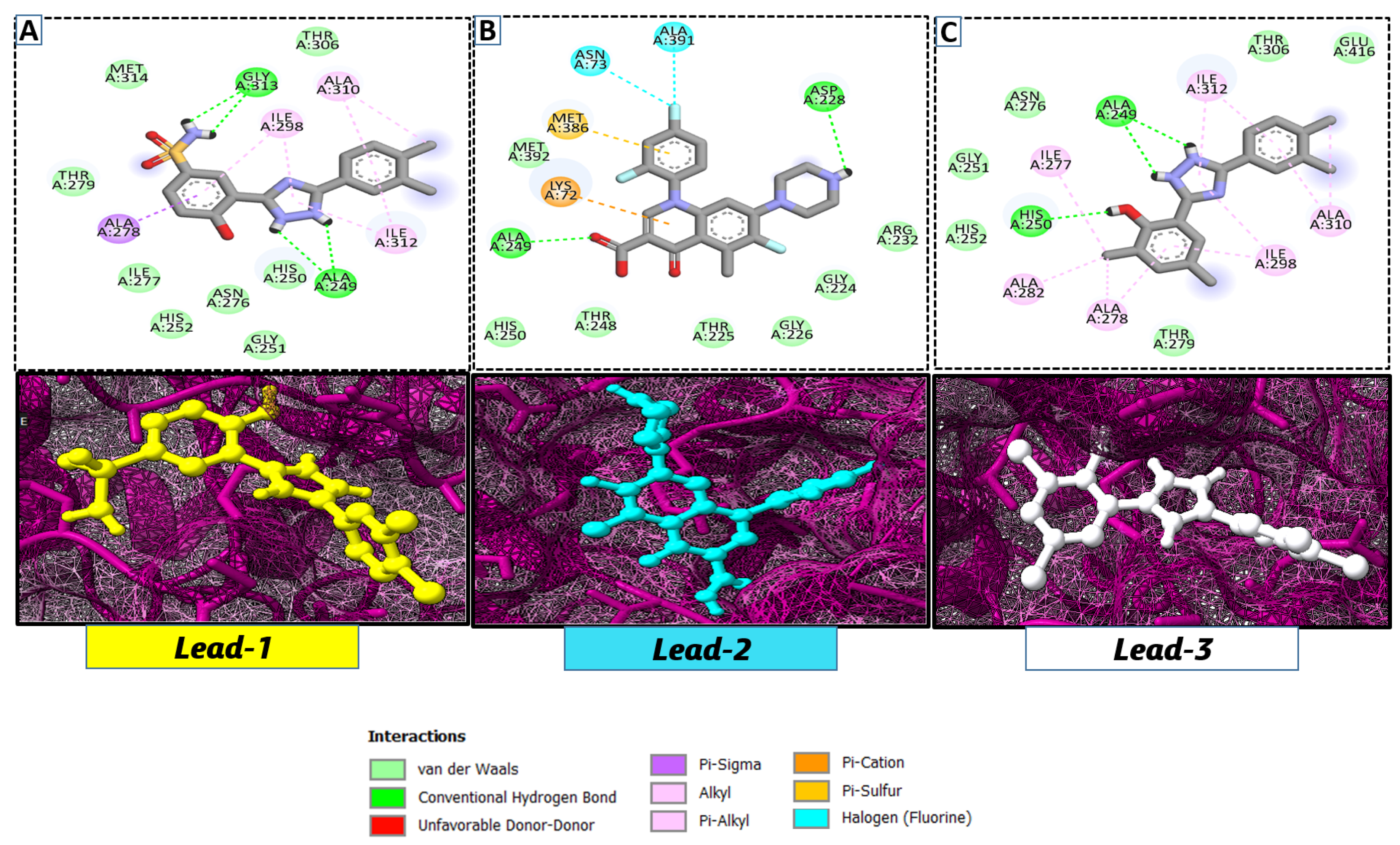

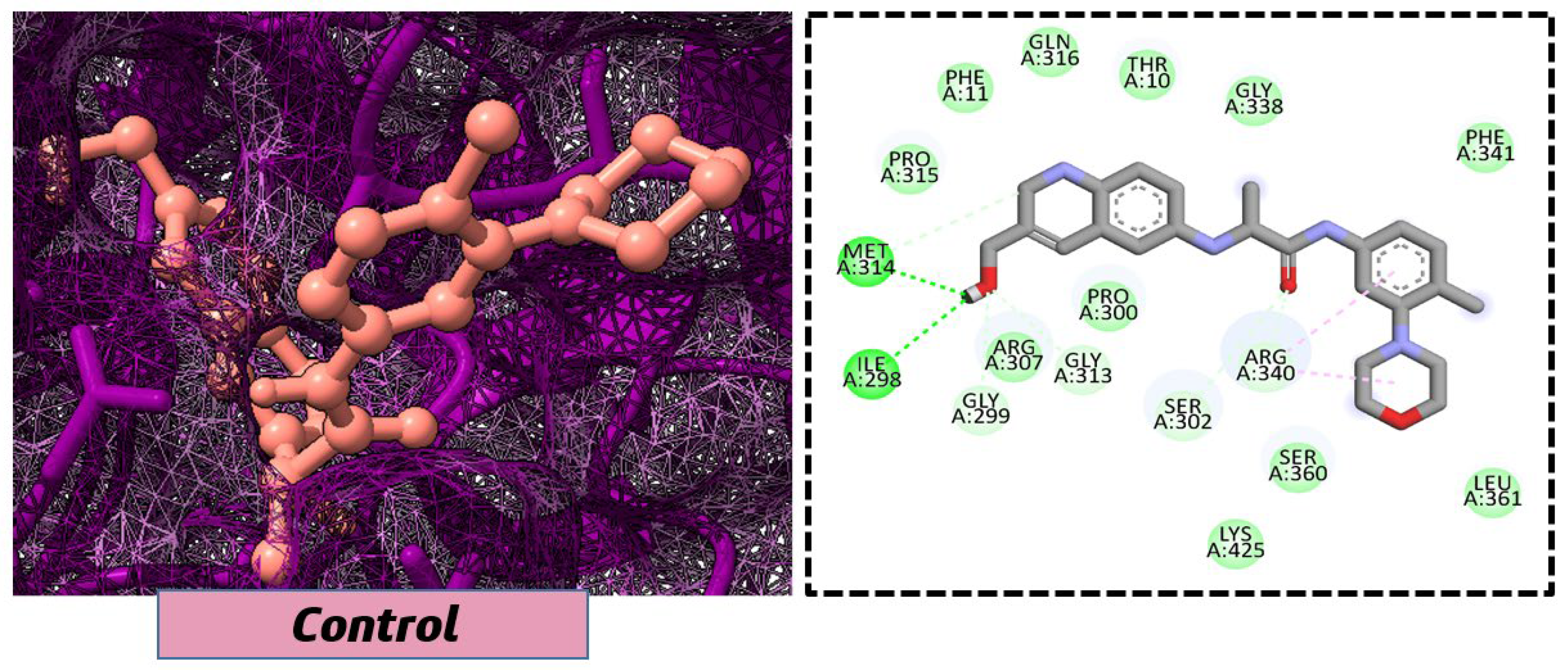

2.3. In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis

2.4. ADMET Properties and Lipinski Rule 5 Fulfillment Standards

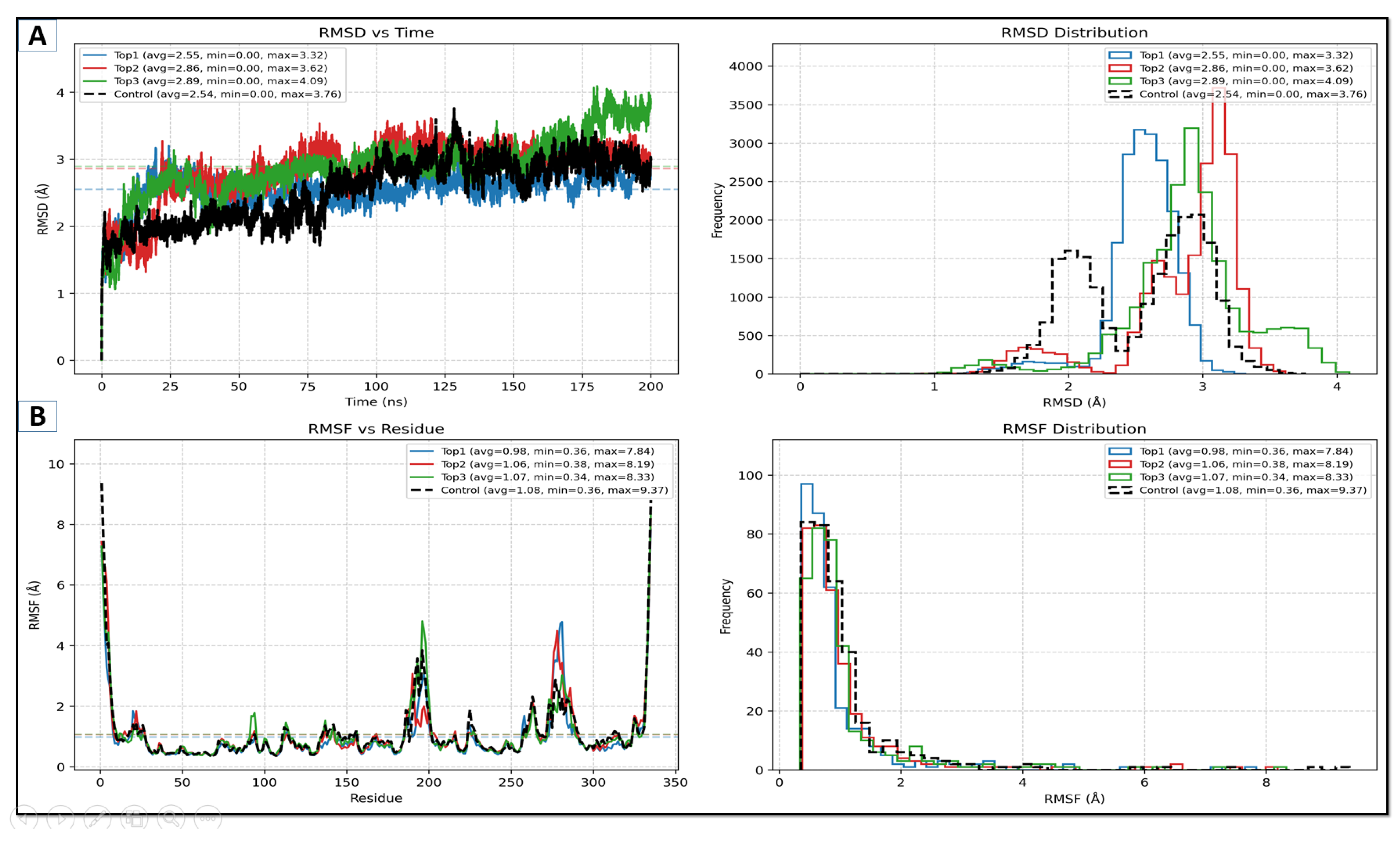

2.5. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

2.5.1. RMSD Alongside RMSF Studies

2.5.2. Rog and Beta Factor

2.5.3. SASA and Ligand RMSD

2.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Free-Energy Landscape (FEL) Analysis

2.7. RDF Assessment

2.8. Hydrogen Bonds Calculation

2.9. DCCM Analyses

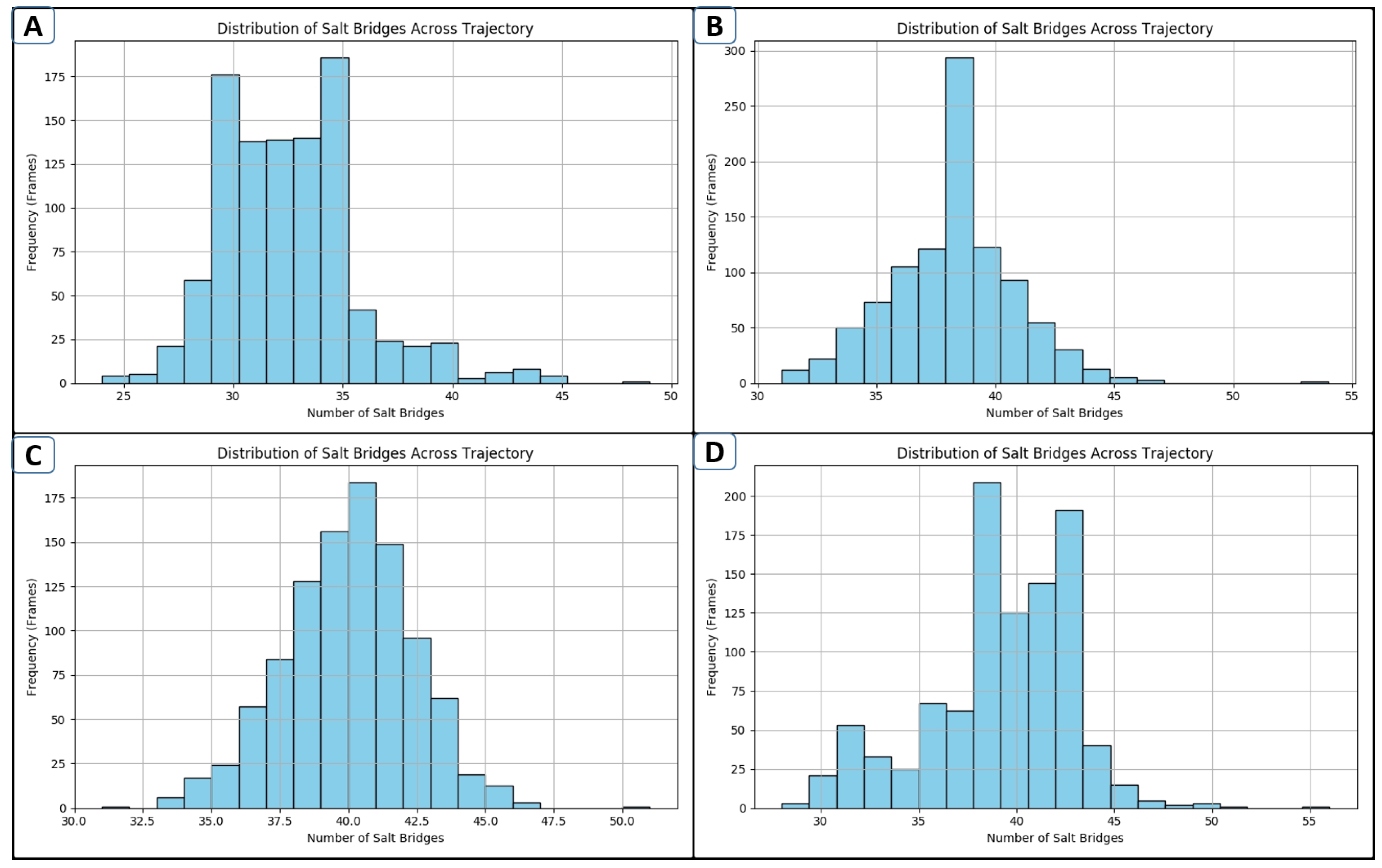

2.10. Salt-Bridge Analysis

2.11. Secondary-Structure Evaluation at the Binding of a Ligand

2.12. MMGB/PBSA, Along with Entropy Energy Estimation

3. Discussion

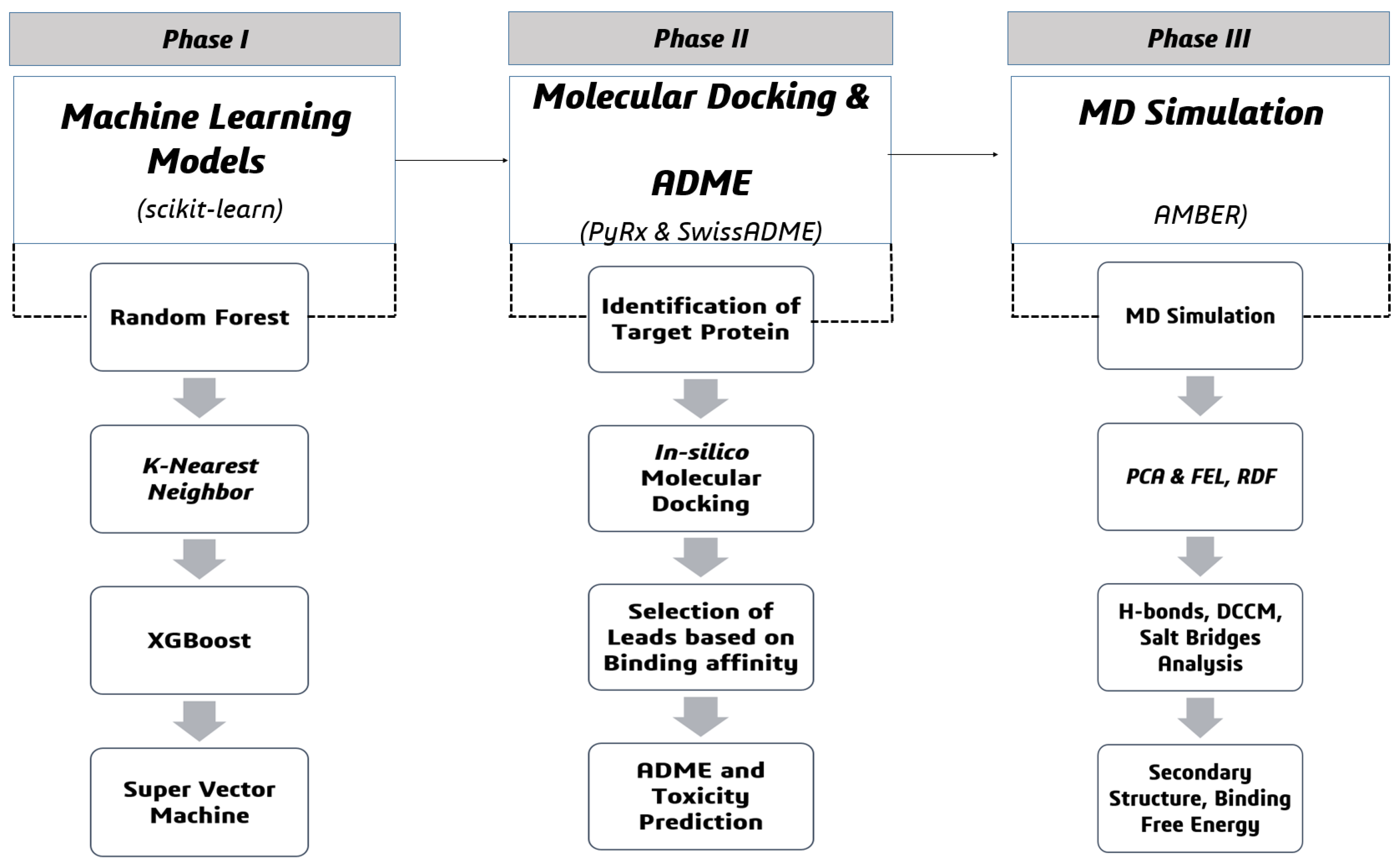

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Machine Learning-Guided Drug Design

4.1.1. Dataset Preparation and Cleaning

4.1.2. Descriptors Calculations and Feature Extraction

4.1.3. Conducting Objective Model Performance Testing

4.1.4. Machine Learning (ML) Model Development and Training

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs)

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Random Forest (RF)

XGBoost

4.2. Molecular Docking Phase

4.2.1. Identification and Preprocessing of the Target Receptor

4.2.2. Library Preparation and Molecular Docking

4.2.3. ADME Features Prediction

4.2.4. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

4.3. Post-Simulation Analysis

4.3.1. PCA and FEL

4.3.2. Radial Distribution Function (RDF)

4.3.3. An Analysis of H-Bonds

4.3.4. DCCM Analysis from MD Trajectories

4.3.5. Secondary-Structure Analysis

4.3.6. Salt-Bridge Assessment

4.3.7. Protein Solvent Environment: MMGB/PBSA and Entropy Energy Estimation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.R.; Gales, A.C.; Laxminarayan, R.; Dodd, P.C. Antimicrobial Resistance: Addressing a Global Threat to Humanity. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.E.; Hyun, D.; Jezek, A.; Samore, M.H. Mortality, Length of Stay, and Healthcare Costs Associated with Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections among Elderly Hospitalized Patients in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Miao, F.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Insights into the Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Outcomes of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in Critically Ill Children. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1282413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance, Epidemiology, Clinical Impact and Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman, R.E.; Sahl, J.W. Other Gram-Negative Bacteria: Acinetobacter, Burkholderia, and Moraxella. In Practical Handbook of Microbiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 613–618. [Google Scholar]

- Alhayek, A.; Abdelsamie, A.S.; Schönauer, E.; Camberlein, V.; Hutterer, E.; Posselt, G.; Serwanja, J.; Blöchl, C.; Huber, C.G.; Haupenthal, J.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of Synthesized and FDA-Approved Inhibitors of Clostridial and Bacillary Collagenases. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 12933–12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knejzlík, Z.; Doležal, M.; Herkommerová, K.; Clarova, K.; Klíma, M.; Dedola, M.; Zborníková, E.; Rejman, D.; Pichová, I. The Mycobacterial GuaB1 Gene Encodes a Guanosine 5′-monophosphate Reductase with a Cystathionine-β-synthase Domain. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5571–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, A. Therapeutic Strategies and Promising Vaccine for Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, E.M.; Aliagas, I.; Crawford, T.; Mao, J.; Harris, S.F.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, P.; Ma, F.; Clark, K. Discovery of GuaB Inhibitors with Efficacy against Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. mBio 2024, 15, e00897-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Agarwal, R.; Baker, M.B.; Baudry, J.; Bhowmik, D.; Boehm, S.; Byler, K.G.; Chen, S.Y.; Coates, L.; Cooper, C.J.; et al. Supercomputer-Based Ensemble Docking Drug Discovery Pipeline with Application to COVID-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 5832–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, K.; Sundaram, D.P.; Marimuthu, S.K. Innovations in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology; Academic Guru Publishing House: Bhopal, India, 2024; ISBN 8197059136. [Google Scholar]

- Satpathy, R. Artificial Intelligence Techniques in the Classification and Screening of Compounds in Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) Process. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. Drug Des. Dev. 2024, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, S.; Dhamercherla, S.; Jadav, S.S.; Babu, C.H.M.; Ahsan, M.J. Machine Learning in Drug Discovery: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 1947–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, M.A.; Mirza, M.U.; Adeel, M.M.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Tahir Ul Qamar, M.; Shahid, F.; Ahmad, S.; Alatawi, E.A.; Albalawi, G.M.; Allemailem, K.S.; et al. Structural Elucidation of Rift Valley Fever Virus L Protein towards the Discovery of Its Potential Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Moffat, J.G.; DuPai, C.; Kofoed, E.M.; Skippington, E.; Modrusan, Z.; Gloor, S.L.; Clark, K.; Xu, Y.; Li, S. Differential Effects of Inosine Monophosphate Dehydrogenase (IMPDH/GuaB) Inhibition in Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00102-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.; Devkar, S.; Gharat, K.; Kasbe, S.; Matharoo, D.K.; Pendse, S.; Bhosale, A.; Bhargava, A. Screening of Phytochemicals as Potential Inhibitors of Breast Cancer Using Structure Based Multitargeted Molecular Docking Analysis. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funari, R.; Bhalla, N.; Gentile, L. Measuring the Radius of Gyration and Intrinsic Flexibility of Viral Proteins in Buffer Solution Using Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2022, 2, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Almutary, A.G.; Alsahli, M.A.; Alnasser, S.; Rah, B. Tamarix Articulata Induced Prevention of Hepatotoxicity Effects of In Vivo Carbon Tetrachloride by Modulating Pro-Inflammatory Serum and Antioxidant Enzymes to Reverse the Liver Fibrosis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Fonseca, A.M.; Caluaco, B.J.; Madureira, J.M.C.; Cabongo, S.Q.; Gaieta, E.M.; Djata, F.; Colares, R.P.; Neto, M.M.; Fernandes, C.F.C.; Marinho, G.S. Screening of Potential Inhibitors Targeting the Main Protease Structure of SARS-CoV-2 via Molecular Docking, and Approach with Molecular Dynamics, RMSD, RMSF, H-Bond, SASA and MMGBSA. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 1919–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandfort, M.; Vantaux, A.; Kim, S.; Obadia, T.; Pepey, A.; Gardais, S.; Khim, N.; Lek, D.; White, M.; Robinson, L.J.; et al. Forest Malaria in Cambodia: The Occupational and Spatial Clustering of Plasmodium Vivax and Plasmodium Falciparum Infection Risk in a Cross-Sectional Survey in Mondulkiri Province, Cambodia. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, S.; Bayıl, I.; Rahman, M.A.; Mukerjee, N.; Maitra, S.; Islam, M.R.; Rajkhowa, S.; Ghosh, A.; Al-Hussain, S.A.; Zaki, M.E.A.; et al. Target Specific Inhibition of West Nile Virus Envelope Glycoprotein and Methyltransferase Using Phytocompounds: An in Silico Strategy Leveraging Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1189786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.S.; Altwaim, S.A.; El-Daly, M.M.; Hassan, A.M.; Al-Zahrani, I.A.; Bajrai, L.H.; Alsaady, I.M.; Dwivedi, V.D.; Azhar, E.I. Marine Fungal Diversity Unlocks Potent Antivirals against Monkeypox through Methyltransferase Inhibition Revealed by Molecular Dynamics and Free Energy Landscape. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.N.; Uversky, V.N. Biological Importance of Arginine: A Comprehensive Review of the Roles in Structure, Disorder, and Functionality of Peptides and Proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 257, 128646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.; Grishina, M.A.; Potemkin, V.A. The Influence of Hydrogen Atoms on the Performance of Radial Distribution Function-Based Descriptors in the Chemoinformatic Studies of HIV-1 Protease Complexes with Inhibitors. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2021, 18, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trong, D.N.; Long, V.C. Effects of Number of Atoms, Shell Thickness, and Temperature on the Structure of Fe Nanoparticles Amorphous by Molecular Dynamics Method. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9976633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, J.T.S.; Feghali, R.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Ramos, M.J.; Fernandes, P.A. The Importance of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds on the Translocation of the Small Drug Piracetam through a Lipid Bilayer. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konermann, L.; Aliyari, E.; Lee, J.H. Mobile Protons Limit the Stability of Salt Bridges in the Gas Phase: Implications for the Structures of Electrosprayed Protein Ions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 3803–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Feng, K.; Liu, J.; Ren, Y. Molecular Modeling Studies of Novel Naphthyridine and Isoquinoline Derivatives as CDK8 Inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 6355–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, A.J.; Ramalli, S.G.; Wallace, B.A. DichroWeb, a Website for Calculating Protein Secondary Structure from Circular Dichroism Spectroscopic Data. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, H.E.; Ahmad, S.; Kumer, A.; Bakri, Y. El In Silico and in Vitro Prediction of New Synthesized N-Heterocyclic Compounds as Anti-SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, F.; Nueda, A.; Lee, J.; Schenone, M.; Prunotto, M.; Mercola, M. Phenotypic Drug Discovery: Recent Successes, Lessons Learned and New Directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Girija, A.S.S.; Priyadharsini, J.V. Targeting NM23-H1-Mediated Inhibition of Tumour Metastasis in Viral Hepatitis with Bioactive Compounds from Ganoderma Lucidum: A Computational Study. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 82, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarinia, H.; Tajbakhsh, E.; Rostamian, M.; Momtaz, H. Design and Validation of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate against Acinetobacter baumannii Using Advanced Computational Methods. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, R.; Subbarao, N. Exploring the Interaction Mechanism between Potential Inhibitor and Multi-Target Mur Enzymes of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Using Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, Principal Component Analysis, Free Energy Landscape, Dynamic Cross-Correlation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 13497–13526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, F.F. Integrated Virtual Screening, Molecular Modeling and Machine Learning Approaches Revealed Potential Natural Inhibitors for Epilepsy. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapero, A.; Pacitto, A.; Singh, V.; Sabbah, M.; Coyne, A.G.; Mizrahi, V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B.; Abell, C. Fragment-Based Approach to Targeting Inosine-5′-Monophosphate Dehydrogenase (IMPDH) from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2806–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattabiraman, N.; Lobello, C.; Rushmore, D.; Mologni, L.; Wasik, M.; Basappa, J. A Novel Allosteric Inhibitor Targeting IMPDH at Y233 Overcomes Resistance to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Lymphoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, M.; Duran-Frigola, M.; Badia-i-Mompel, P.; Pauls, E.; Orozco-Ruiz, M.; Guitart-Pla, O.; Alcalde, V.; Diaz, V.M.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Brun-Heath, I. Bioactivity Descriptors for Uncharacterized Chemical Compounds. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, M.; Gerlach, J.Q.; Dziembała, I.; Kilcoyne, M. Calculating Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) Values from Glycomics Microarray Data Using GraphPad Prism. In Glycan Microarrays: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzehali, H.; Lotfi, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Kumar, P. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Modeling for Predication of Inhibition Potencies of Imatinib Derivatives Using SMILES Attributes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervin, L.H.; Trapotsi, M.-A.; Afzal, A.M.; Barrett, I.P.; Bender, A.; Engkvist, O. Probabilistic Random Forest Improves Bioactivity Predictions Close to the Classification Threshold by Taking into Account Experimental Uncertainty. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, J.H.; Ross, E.G. Evaluating Prediction Model Performance. Surgery 2023, 174, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varoquaux, G.; Colliot, O. Evaluating Machine Learning Models and Their Diagnostic Value. In Machine Learning for Brain Disorders; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 601–630. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, M. Optimization of Regression Models Using Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Study with Scikit-Learn. Int. Uni-Sci. Res. J. 2024, 5, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasih, A.; Previana, C.N. Implementation of GridSearchCV to Find the Best Hyperparameter Combination for Classification Model Algorithm in Predicting Water Potability. J. Artif. Intell. Eng. Appl. 2025, 4, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, F.S. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve: Overview and Practical Use for Clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2022, 75, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Iqbal, M.N.; Ibrahim, M.; Haq, I.U.; Alonazi, W.B.; Siddiqi, A.R. Computational Exploration of Novel ROCK2 Inhibitors for Cardiovascular Disease Management; Insights from High-Throughput Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking, DFT and MD Simulation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periwal, V.; Bassler, S.; Andrejev, S.; Gabrielli, N.; Patil, K.R.; Typas, A.; Patil, K.R. Bioactivity Assessment of Natural Compounds Using Machine Learning Models Trained on Target Similarity between Drugs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Panchal, S.; Chauhan, V.; Brahmbhatt, N.; Mevawalla, A.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M. Python-based Scikit-learn Machine Learning Models for Thermal and Electrical Performance Prediction of High-capacity Lithium-ion Battery. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyal, M.; Goyal, P. A Review on Analysis of K-Nearest Neighbor Classification Machine Learning Algorithms Based on Supervised Learning. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2022, 70, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadevi, P.; Das, R. An Extensive Analysis of Machine Learning Techniques with Hyper-Parameter Tuning by Bayesian Optimized SVM Kernel for the Detection of Human Lung Disease. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 97752–97770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shen, J.; Xiao, G.; Hong, H.; Lin, H.; Wu, F.; Liao, B.-Q. New Methods Based on Back Propagation (BP) and Radial Basis Function (RBF) Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for Predicting the Occurrence of Haloketones in Tap Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Ajmal, A.; Mahmood, A.; Khurshid, B.; Li, P.; Jan, S.M.; Rehman, A.U.; He, P.; Abdalla, A.N.; Umair, M.; et al. Identification of Novel Inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 as Therapeutic Options Using Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking and MD Simulation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1060076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Hadidi, T.N.; Hasoon, S.O. Software Defect Prediction Using Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with Optimization Hyperparameter. Al-Rafidain J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2024, 18, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.; Hammoudeh, Z.; Lowd, D. Adapting and Evaluating Influence-Estimation Methods for Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rauf, A.; Rashid, U.; Akram, Z.; Ghafoor, M.; Muhammad, N.; Al Masoud, N.; Alomar, T.S.; Naz, S.; Iriti, M. In Vitro and in Silico Antiproliferative Potential of Isolated Flavonoids Constitutes from Pistacia Integerrima. Zeitschrift Fur Naturforsch.-Sect. C J. Biosci. 2024, 79, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akshaya, J.; Rahul, G.; Karthigayan, S.R.; Rishekesan, S.V.; Harischander, A.; Kumar, S.S.; Soman, K.P. A Comparison between Steepest Descent and Non-Linear Conjugate Gradient Algorithms for Binding Energy Minimization of Organic Molecules. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 2484, p. 12004. [Google Scholar]

- Kondapuram, S.K.; Sarvagalla, S.; Coumar, M.S. Docking-Based Virtual Screening Using PyRx Tool: Autophagy Target Vps34 as a Case Study. In Molecular Docking for Computer-Aided Drug Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Takio, N.; Basumatary, D.; Yadav, M.; Yadav, H.S. Electrostatic and Van Der Waals Forces. In Biochemistry: Fundamentals and Bioenergetics; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2021; pp. 55–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, P.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, M.; Kapil, A.; Abdul Samath, E.; Kaur, P. Identification of Novel Natural MurD Ligase Inhibitors as Potential Antimicrobial Agents Targeting Acinetobacter baumannii: In Silico Screening and Biological Evaluation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 14051–14066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, Y.; Niu, T.; Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, H. DruglikeFilter 1.0: An AI Powered Filter for Collectively Measuring the Drug-Likeness of Compounds. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterres, H.; Park, S.; Zhang, H.; Perone, T.; Kim, J.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI High-throughput Simulator for Efficient Evaluation of Protein–Ligand Interactions with Different Force Fields. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, e4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Li, Z.; Song, L.F.; Li, P.; Merz, K.M., Jr. Parameterization of Monovalent Ions for the OPC3, OPC, TIP3P-FB, and TIP4P-FB Water Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Minkara, M.S. Comparative Assessment of Water Models in Protein–Glycan Interaction: Insights from Alchemical Free Energy Calculations and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 9459–9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger-Hoerschinger, V.J.; Waibl, F.; Molino, V.; Carter, H.; Fernández-Quintero, M.; Ramsey, S.; Roe, D.R.; Liedl, K.R.; Gilson, M.K.; Kurtzman, T. Quantifying Spatially Resolved Hydration Thermodynamics Using Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory [v1. 0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 6, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Mondal, S.; Purnaprajna, M.; Athri, P. Review of Electrostatic Force Calculation Methods and Their Acceleration in Molecular Dynamics Packages Using Graphics Processors. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 32877–32896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zheng, K.; Ren, L.; Cheng, J.; Feng, X.; Zhang, R. Molecular Screening of Natural Compounds Targeting KRAS (G12C): A Multi-Parametric Strategy against Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2025, 40, 2568121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, M.; Metson, J.; Ren, W.; Chatzittofi, M.; Yagi, K.; Sugita, Y.; Golestanian, R.; Laurino, P. Enzymes Can Activate and Mobilize the Cytoplasmic Environment across Scales. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, H.; Xue, B.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yue, X. Investigating the Binding Mechanism of AML Inhibitors Based on Panobinostat with HDAC3 Proteins Using Gaussian Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 26240–26252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Villellas, L.; Mikkelsen, C.C.K.; Galano-Frutos, J.J.; Marco-Sola, S.; Alastruey-Benedé, J.; Ibáñez, P.; Echenique, P.; Moretó, M.; De Rosa, M.C.; García-Risueño, P. ILVES: Accurate and Efficient Bond Length and Angle Constraints in Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025, 21, 8711–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Kong, C.; Sun, B.; Zhu, R. Application of Python-Based Abaqus Secondary Development in Laser Shock Forming of Aluminum Alloy 6082-T6. Micromachines 2024, 15, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, A.S.; Mansour, Y.; Aboul-ela, F. The Perturbed Free-energy Landscape: Linking Ligand Binding to Biomolecular Folding. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, B.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, J.; Jung, C.; Na, D. In Silico Methods and Tools for Drug Discovery. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 137, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafiq, M.; Chaouiki, A.; Suhartono, T.; Ko, Y.G. Albumin Protein Encapsulation into a ZIF-8 Framework with Co-LDH-Based Hierarchical Architectures for Robust Catalytic Reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 23984–23998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, M.; Kandaswamy, K.; Natesan, S.; Devarajan, R.D.; Ramakrishnan, S.G.; Kothandan, R. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Studies on Plasmepsin V of Malarial Parasite Plasmodium Vivax. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2020, 19, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.B.; Kumbhar, S.T. Identification of Potential CDK 8 Inhibitor from Pyrimidine Derivatives via In-Silico Approach. J. Med. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2023, 12, 6038–6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Yang, H.; Zhou, S.; Huang, F.; Wei, Z.; Peng, Z. Deoxythymidylate Kinase (DTYMK) Participates in Cell Cycle Arrest to Promote Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Progression Regulated by MiR-491-5p through TP53 and Is Associated with Tumor Immune Infiltration. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 14, 1546–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva Sharma, A.; Viswadevarayalu, A.; Bharathi, A.C.; Anand, K.; Ali, S.; Li, H.; Ibrahim, B.S.; Chen, Q. Unravelling the Distinctive Mode of Cooperative and Independent Interaction Mechanism of 1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate Ionic Liquid with Model Transport Proteins by Comprehensive Spectroscopic and Computational Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Bernal, G.; Vargas, R.; Martínez, A. Salt Bridge: Key Interaction between Antipsychotics and Receptors. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2023, 142, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miandad, K.; Ullah, A.; Bashir, K.; Khan, S.; Abideen, S.A.; Shaker, B.; Alharbi, M.; Alshammari, A.; Ali, M.; Haleem, A.; et al. Virtual Screening of Artemisia Annua Phytochemicals as Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Enzyme. Molecules 2022, 27, 8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Restrepo, A.; Rubi, J.M. Thermodynamic Insights into Symmetry Breaking: Exploring Energy Dissipation across Diverse Scales. Entropy 2024, 26, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | Model | SE | SP | Q+ | Q− | ACC | F1 Score | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing Set | Random Forest | 97 | 87 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 98 | 91 |

| Support Vector Machine | 96 | 75 | 92 | 89 | 93 | 96 | 83 | |

| K-Nearest Neighbor | 95 | 75 | 92 | 95 | 93 | 96 | 83 | |

| XGBoost | 91 | 87 | 96 | 92 | 96 | 97 | 91 | |

| Validation Set | Random Forest | 96 | 90 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 93 |

| Support Vector Machine | 96 | 97 | 95 | 90 | 97 | 98 | 93 | |

| K-Nearest Neighbor | 96 | 83 | 95 | 90 | 96 | 98 | 93 | |

| XGBoost | 95 | 90 | 96 | 90 | 95 | 96 | 86 |

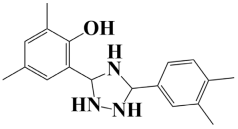

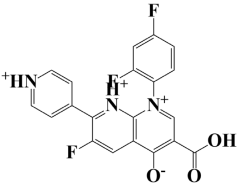

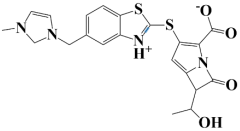

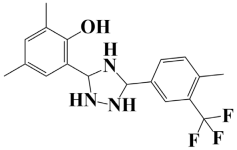

| S. # | Compound Rank | Binding Affinity | Chemical Name | Chemical Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

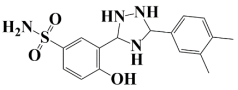

| 1. | Lead-1 | −8.1 kcal/mol | 3-(5-(3,4-dimethylphenyl)-1,2,4-triazolidin-3-yl)-4-hydroxybenzenesulfonamide |  |

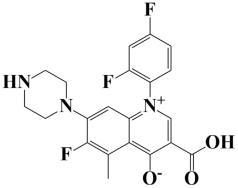

| 2. | Lead-2 | −7.6 kcal/mol | 3-carboxy-1-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-6-fluoro-5-methyl-7-(piperazin-1-yl)quinolin-1-ium-4-olate |  |

| 3. | Lead-3 | −7.5 kcal/mol | 2-(5-(3,4-dimethylphenyl)-1,2,4-triazolidin-3-yl)-4,6-dimethylphenol |  |

| 4. | Lead-4 | −7.4 kcal/mol | 3-carboxy-1-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-6-fluoro-7-(pyridin-1-ium-4-yl)-1,8-naphthyridin-1,8-diium-4-olate |  |

| 5. | Lead-5 | −7.2 kcal/mol | 6-(1-hydroxyethyl)-3-((5-((3-methyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)methyl)benzo[d]thiazol-3-ium-2-yl)thio)-7-oxo-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]hepta-2,4-diene-2-carboxylate |  |

| 6. | Lead-6 | −7.2 kcal/mol | 2,4-dimethyl-6-(5-(4-methyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,2,4-triazolidin-3-yl)phenol |  |

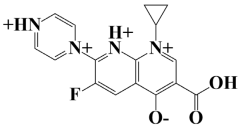

| 7. | Lead-7 | −7.2 kcal/mol | 3-carboxy-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-7-(pyrazin-1,4-diium-1-yl)-1,8-naphthyridin-1,8-diium-4-olate |  |

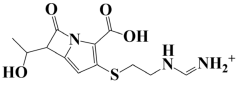

| 8. | Lead-8 | −7.1 kcal/mol | ((2-((2-carboxy-6-(1-hydroxyethyl)-7-oxo-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]hepta-2,4-dien-3-yl)thio)ethyl)amino)methaniminium |  |

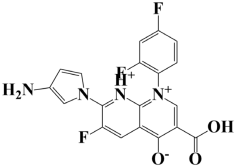

| 9. | Lead-9 | −7 kcal/mol | 7-(3-amino-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-3-carboxy-1-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-6-fluoro-1,8-naphthyridin-1,8-diium-4-olate |  |

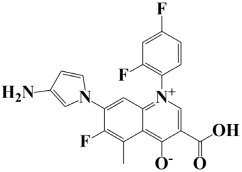

| 10. | Lead-10 | −7 kcal/mol | 7-(3-amino-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-3-carboxy-1-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-6-fluoro-5-methylquinolin-1-ium-4-olate |  |

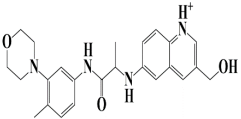

| 11. | Control | −7.5 kcal/mol | 3-(hydroxymethyl)-6-((1-((4-methyl-3-morpholinophenyl)amino)-1-oxopropan-2-yl)amino)quinolin-1-ium |  |

| ADME Properties | Toxicity Properties | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | G-I | Bioavailability Score | TPSA | Consensus Log Po/w | AMES Toxicity | hERG I Inhibitor | hERG II Inhibitor | ||||

| Lead-1 | High | 0.55 | 124.86 Å2 | 0.93 | No | No | No | ||||

| Lead-2 | High | 0.55 | 79.51 Å2 | 2.13 | No | No | No | ||||

| Lead-2 | High | 0.55 | 56.32 Å2 | 3.08 | No | No | No | ||||

| Control | High | 0.55 | 87.97 Å2 | 2.52 | No | No | Yes | ||||

| Lipinski’s Rule of 5 Profile | |||||||||||

| MW | MlogP | H-BA | H-BD | Lipinski | |||||||

| 348.42 g/mol | 1.21 | 7 | 5 | Yes, 0 Violations | |||||||

| 417.38 g/mol | −1.28 | 7 | 2 | Yes, 0 Violations | |||||||

| 297.39 g/mol | 3.08 | 4 | 4 | Yes, 0 Violations | |||||||

| 421.51 g/mol | 3.46 | 3 | 4 | Yes, 0 Violations | |||||||

| Lead-1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Acceptor | DonorH | Donor | Frames | Frac | AvgDist | AvgAng |

| LIG_336@N3 | GLY_200@H | GLY_200@N | 129 | 0.129 | 2.9266 | 162.2301 |

| HIE_137@ND1 | LIG_336@H1 | LIG_336@N2 | 14 | 0.014 | 2.8751 | 148.5278 |

| THR_166@OG1 | LIG_336@H2 | LIG_336@O | 8 | 0.008 | 2.8443 | 154.6046 |

| HIE_137@ND1 | LIG_336@H2 | LIG_336@O | 1 | 0.001 | 2.9215 | 161.8313 |

| ALA_136@O | LIG_336@H1 | LIG_336@N2 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.9384 | 155.4181 |

| PRO_187@O | LIG_336@H1 | LIG_336@N2 | 228 | 0.228 | 2.8765 | 157.7332 |

| GLY_186@O | LIG_336@HN | LIG_336@N3 | 63 | 0.063 | 2.8572 | 151.7532 |

| ASP_12@OD2 | LIG_336@H | LIG_336@N | 9 | 0.009 | 2.7906 | 149.4962 |

| MET_201@O | LIG_336@HN | LIG_336@N3 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.8301 | 166.6044 |

| ARG_194@NH1 | LIG_336@H2 | LIG_336@O2 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.9643 | 142.3263 |

| Technique | Energy Section | Lead-1 | Entropy | Lead-2 | Entropy | Lead-3 | Entropy | Control | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMGBSA | Van der Waals Energy (kcal/mol) | −111.64 (±7.21) | 12 | −98.71 (±5.36) | 11.4 | −96.37 (±5.01) | 11.5 | −100.88 (±6.07) | 11.8 |

| Electrostatic Energy (kcal/mol) | −35.01 (±5.37) | −38.49 (±4.36) | −32.52 (±3.67) | −38.19 (±6.50) | |||||

| Polar-Solvation Energy (SE) (kcal/mol) | 21.36 (±3.08) | 19.47 (±1.89) | 24.34 (±2.34) | 22.09 (±2.05) | |||||

| Non-Polar SE (kcal/mol) | −9.67 (±1.63) | −8.01 (±0.56) | −8.07 (±0.55) | −10.56 (±0.61) | |||||

| Gas Phase Energy (kcal/mol) | −146.65 (±8.44) | −137.2 (±8.69) | −128.89 (±7.80) | −139.07 (±9.03) | |||||

| Total Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | −134.96 (±7.56) | −125.74 (±7.00) | −112.62 (±6.30) | −127.54 (±6.21) | |||||

| MMPBSA | Van der Waals Energy (kcal/mol) | −111.64 (±7.21) | −98.71 (±5.36) | −96.37 (±5.01) | −100.88 (±6.07) | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy (kcal/mol) | −35.01 (±5.37) | −38.49 (±4.36) | −32.52 (±3.67) | −38.19 (±6.50) | |||||

| Polar Salvation Energy (SE) (kcal/mol) | 30.66 (±3.01) | 29.78 (±3.19) | 26.70 (±3.50) | 28.90 (±3.45) | |||||

| Non-Polar SE (kcal/mol) | −7.08 (±0.69) | −8.11 (±0.48) | −7.58 (±0.59) | −9.73 (±1.28) | |||||

| Gas Phase Energy (kcal/mol) | −146.65 (±8.44) | −137.2 (±8.69) | −128.89 (±8.09) | −139.07 (±9.79) | |||||

| Total (kcal/mol) | −123.07 (±7.13) | −115.53 (±7.59) | −109.77 (±6.58) | −119.9 (±6.37) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljasir, M.A.; Ahmad, S. Decoding GuaB: Machine Learning-Powered Discovery of Enzyme Inhibitors Against the Superbug Acinetobacter baumannii. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121842

Aljasir MA, Ahmad S. Decoding GuaB: Machine Learning-Powered Discovery of Enzyme Inhibitors Against the Superbug Acinetobacter baumannii. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121842

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljasir, Mohammad Abdullah, and Sajjad Ahmad. 2025. "Decoding GuaB: Machine Learning-Powered Discovery of Enzyme Inhibitors Against the Superbug Acinetobacter baumannii" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121842

APA StyleAljasir, M. A., & Ahmad, S. (2025). Decoding GuaB: Machine Learning-Powered Discovery of Enzyme Inhibitors Against the Superbug Acinetobacter baumannii. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121842