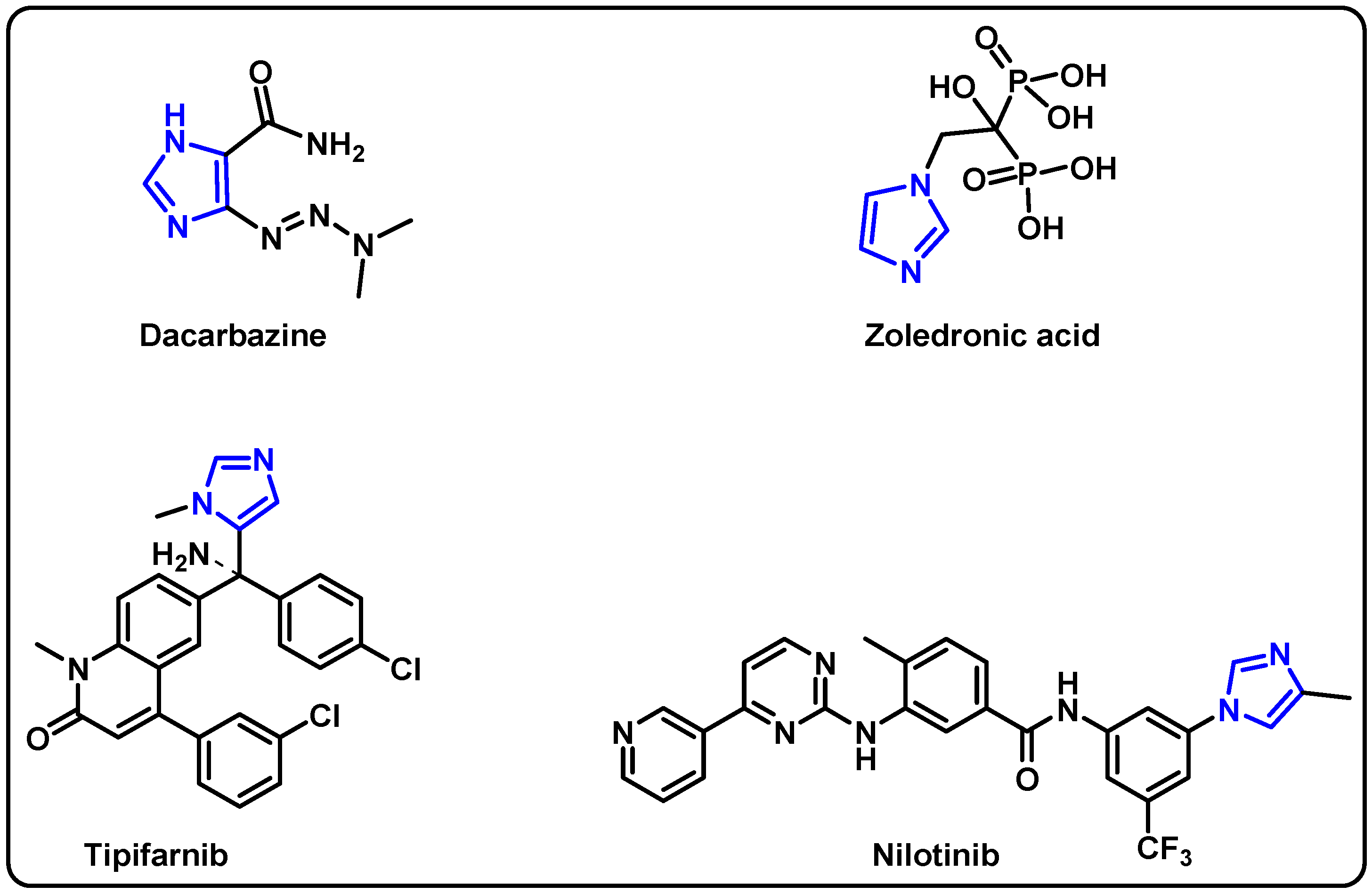

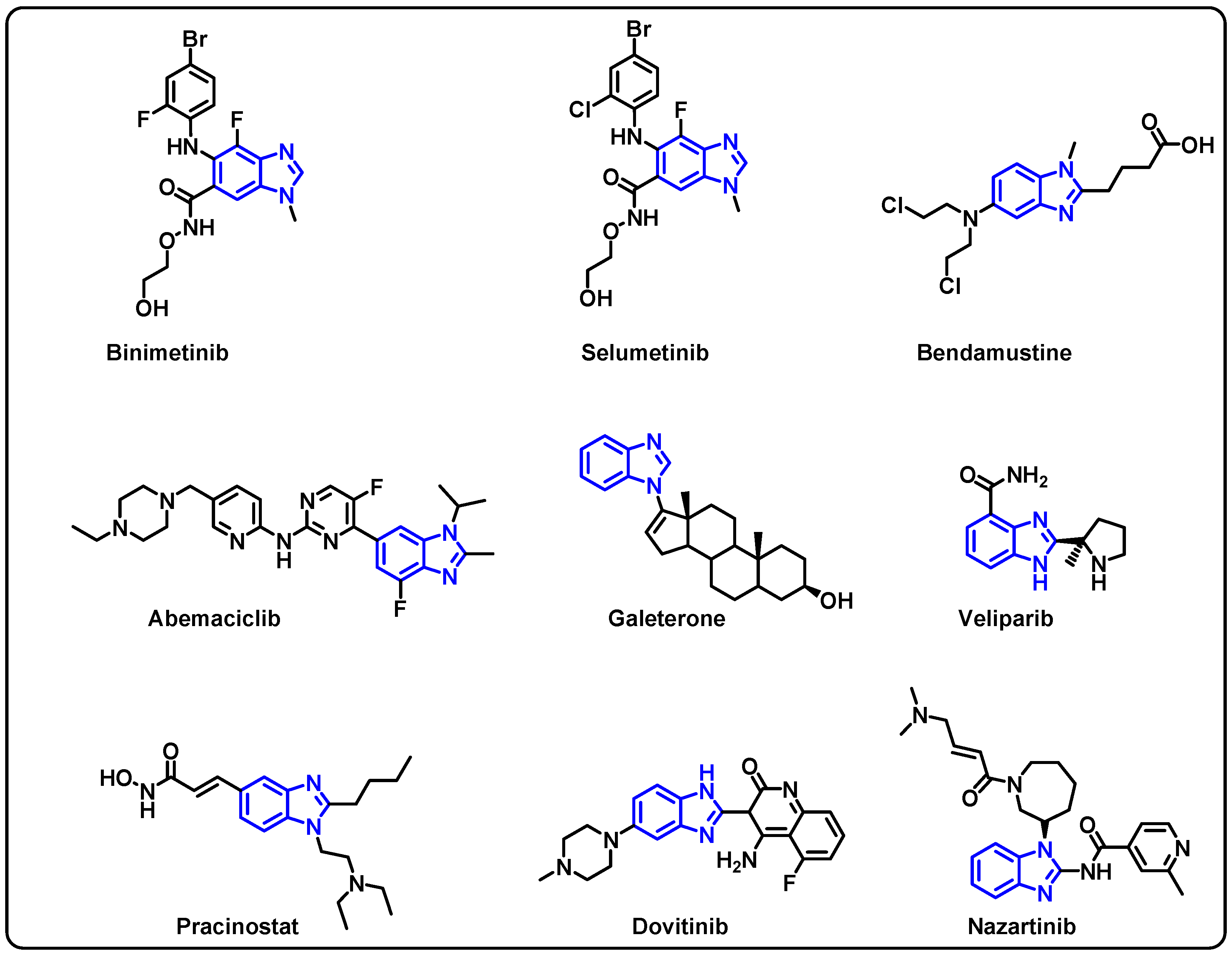

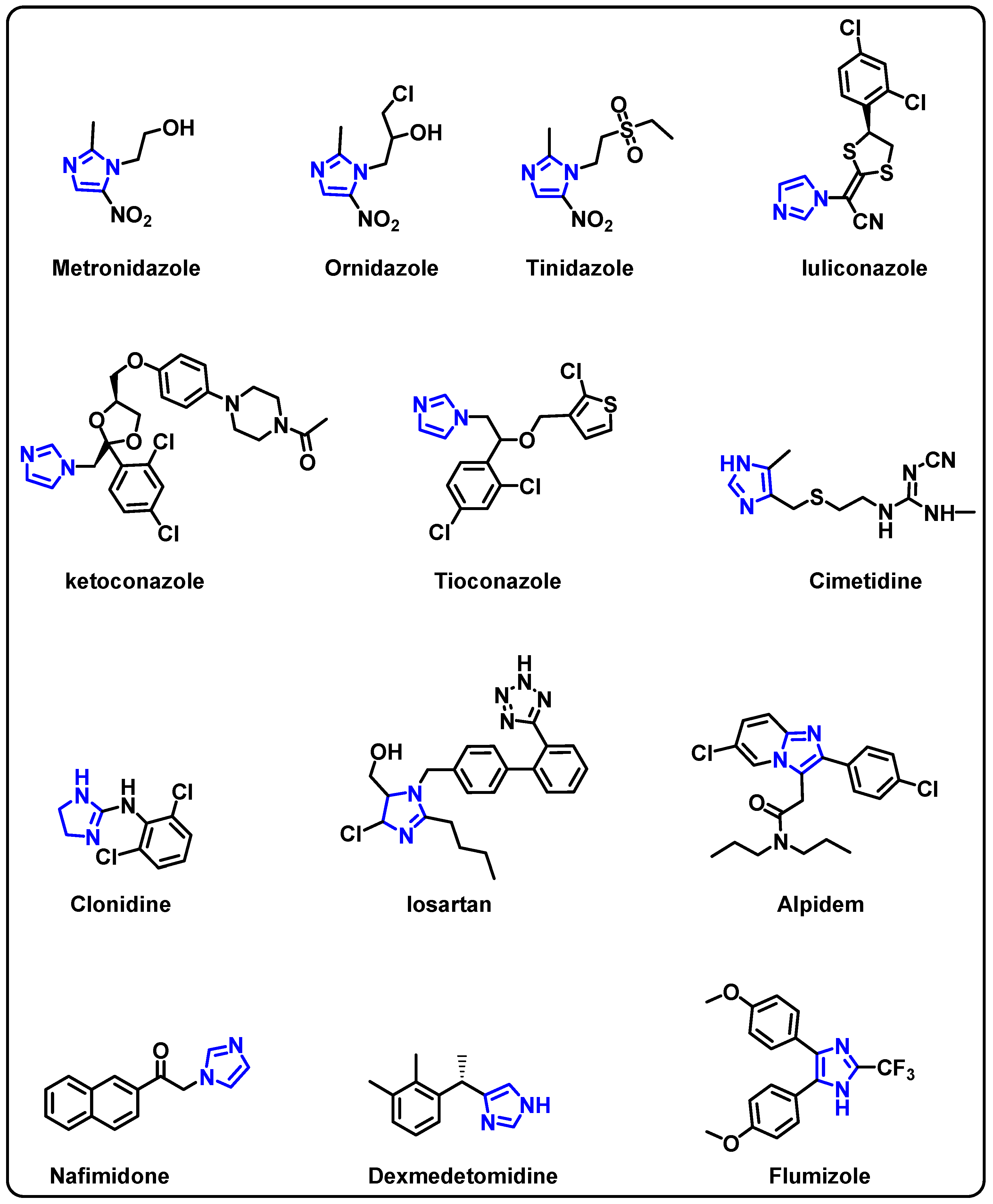

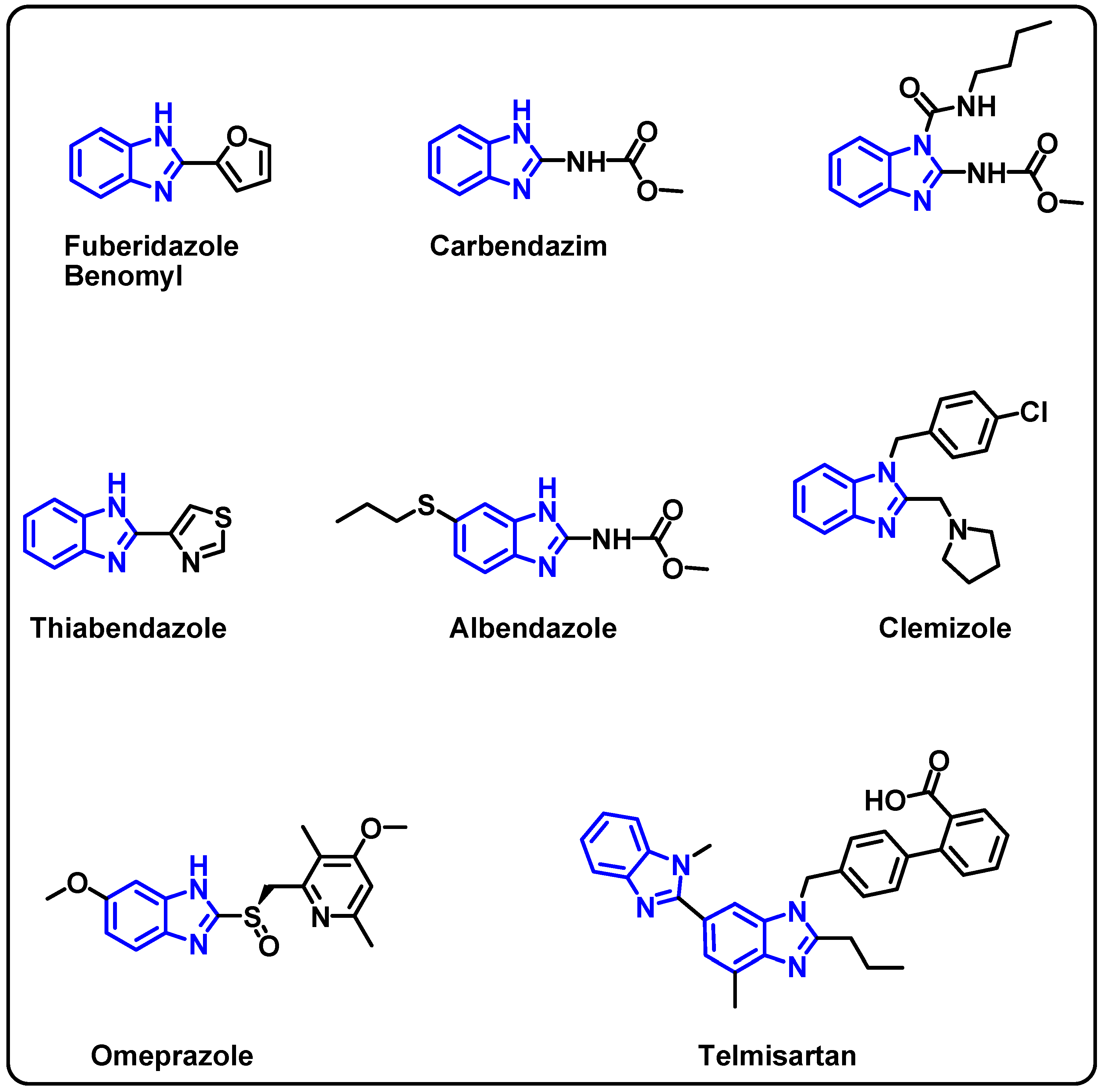

Insight into the Anticancer Potential of Imidazole-Based Derivatives Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

2.1. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Inhibitors

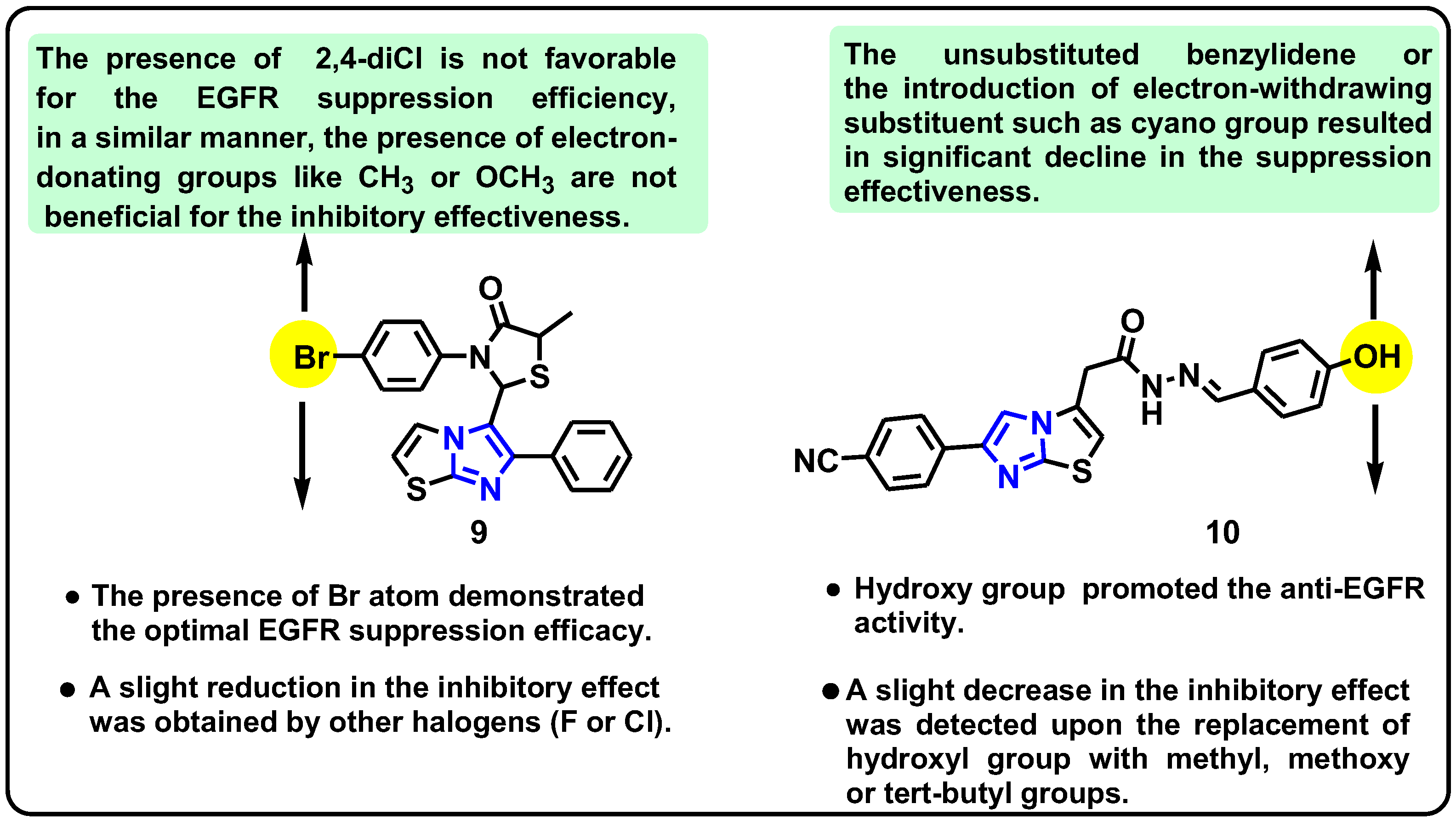

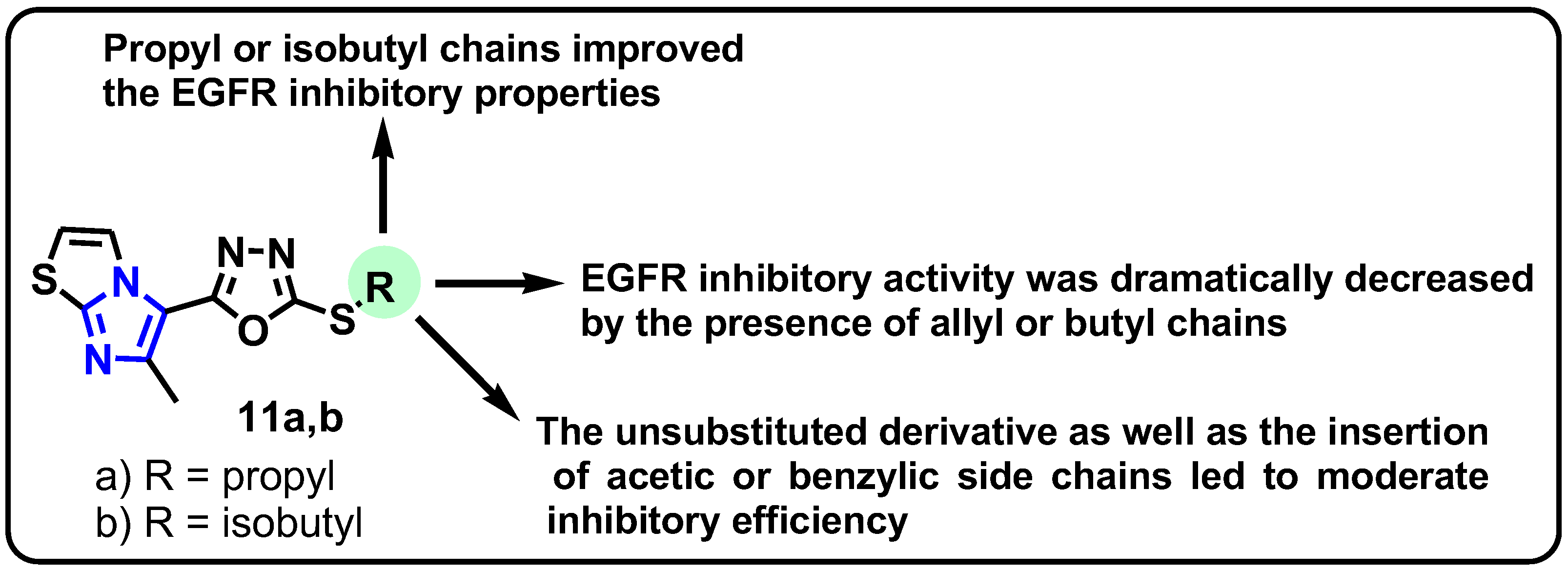

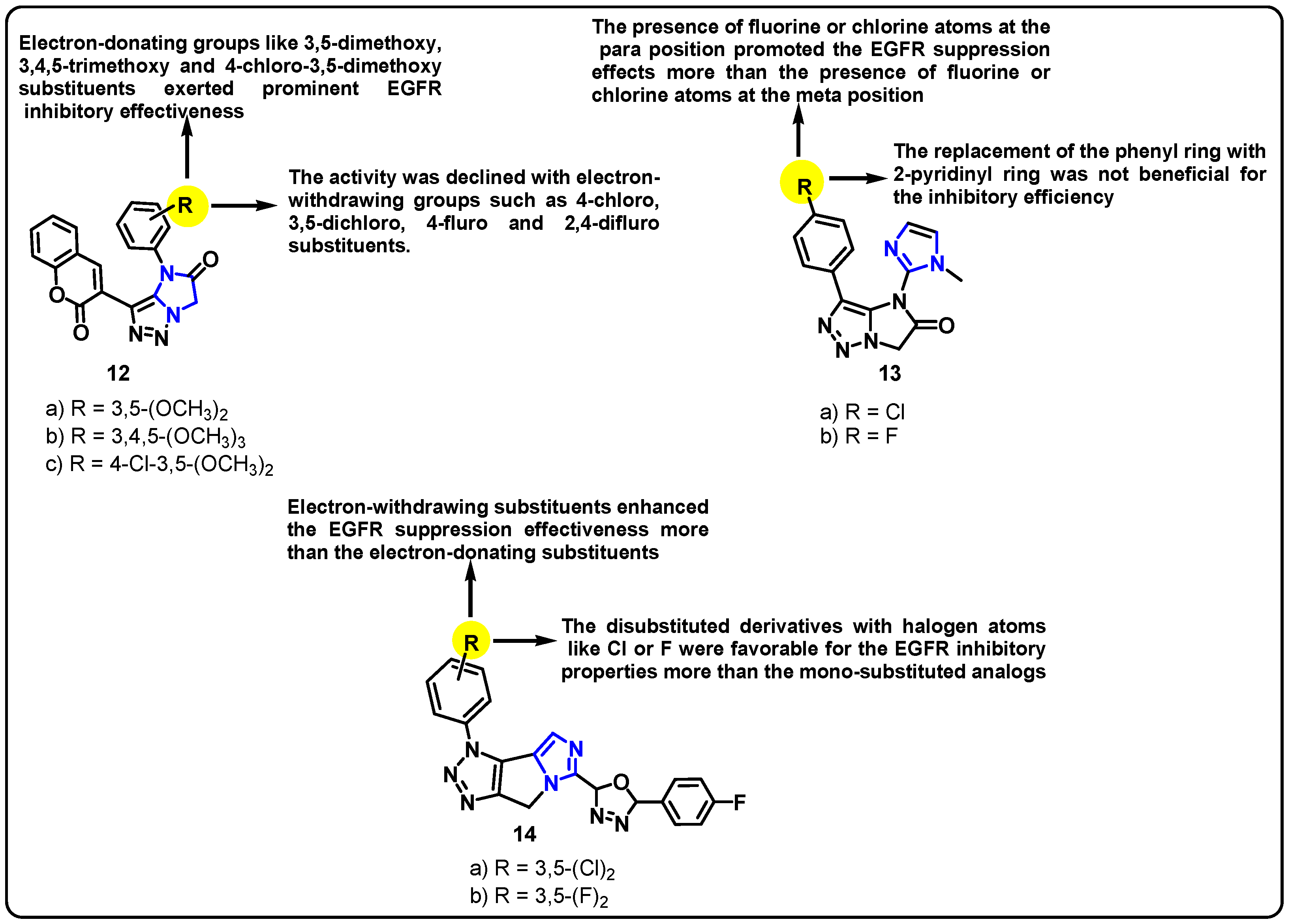

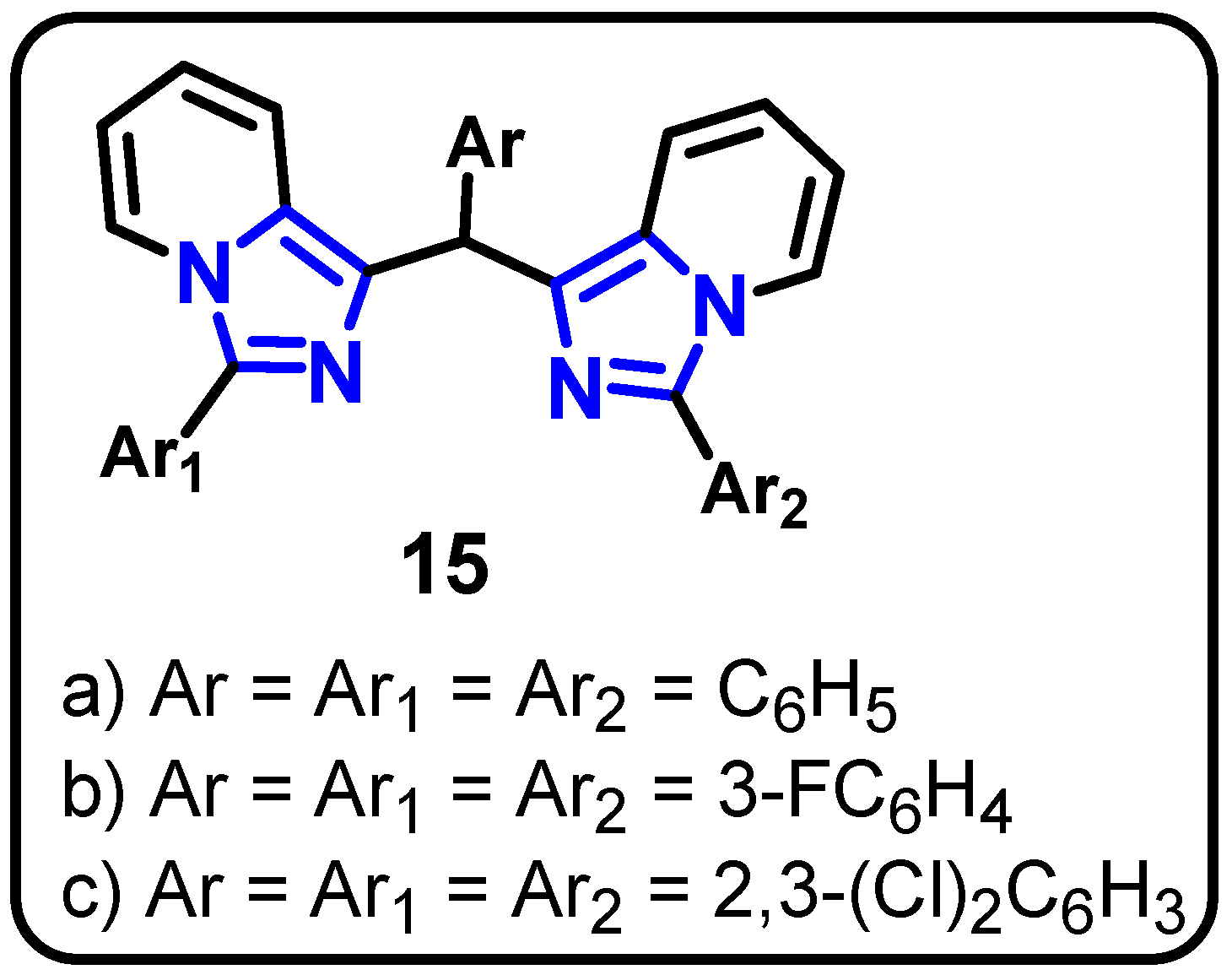

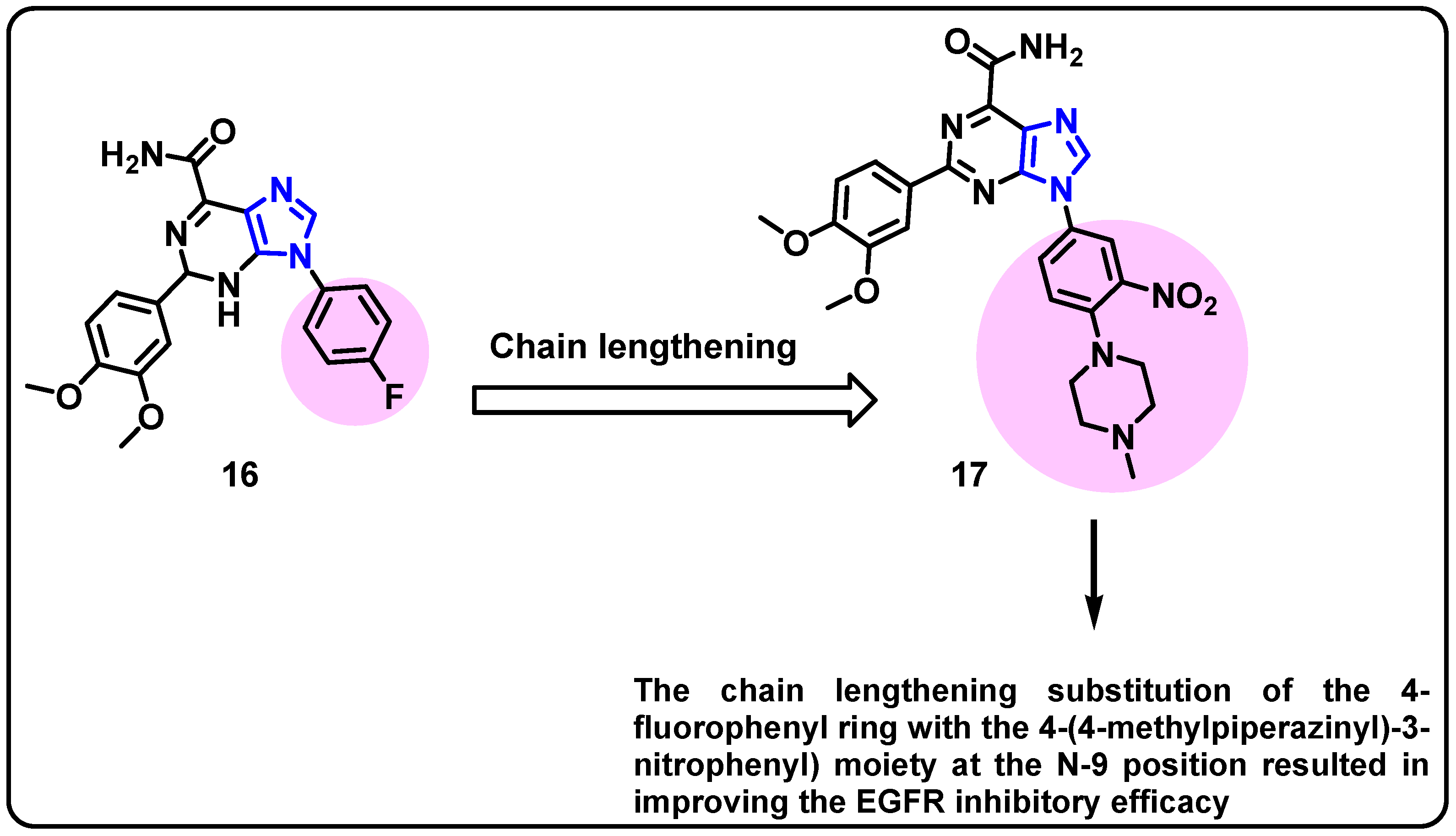

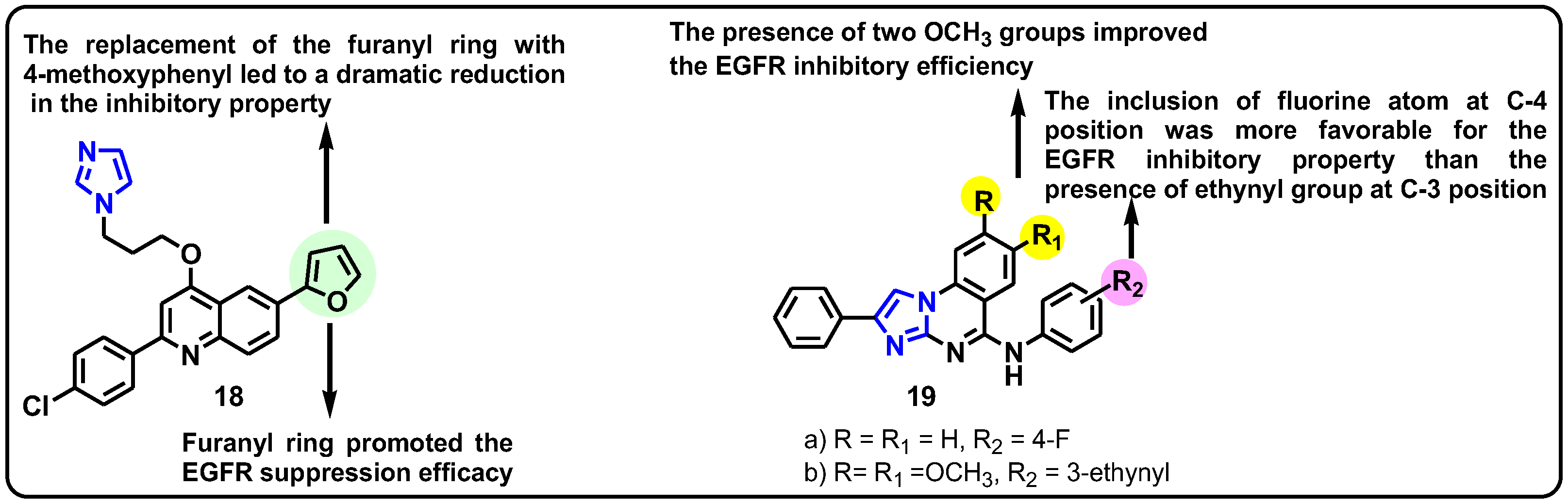

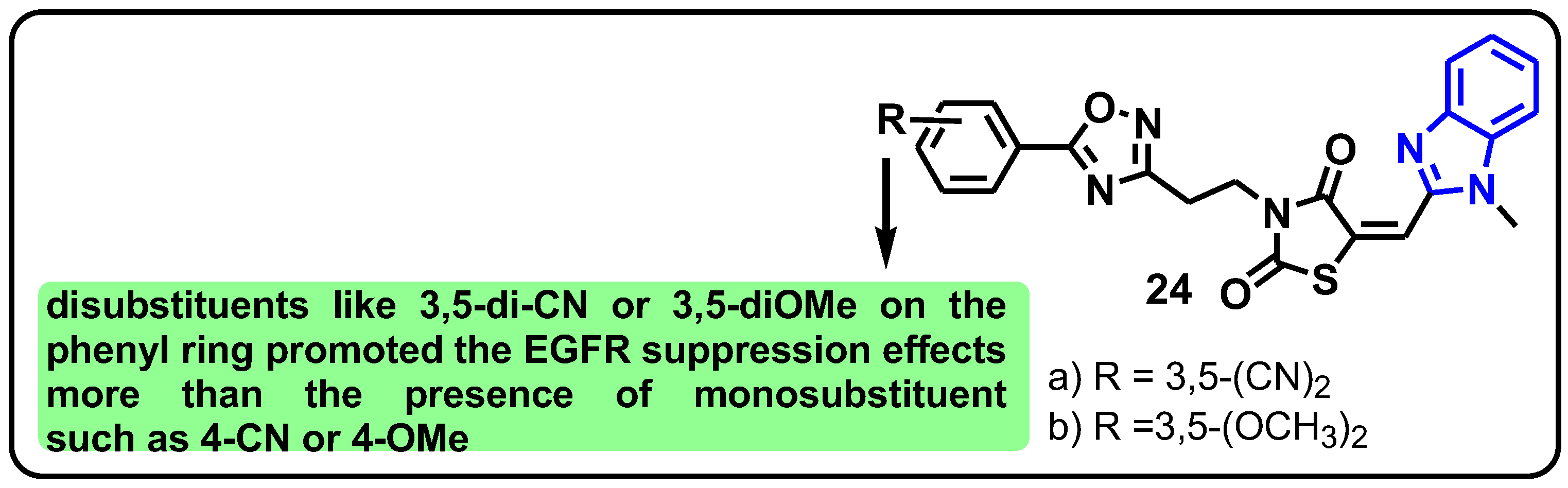

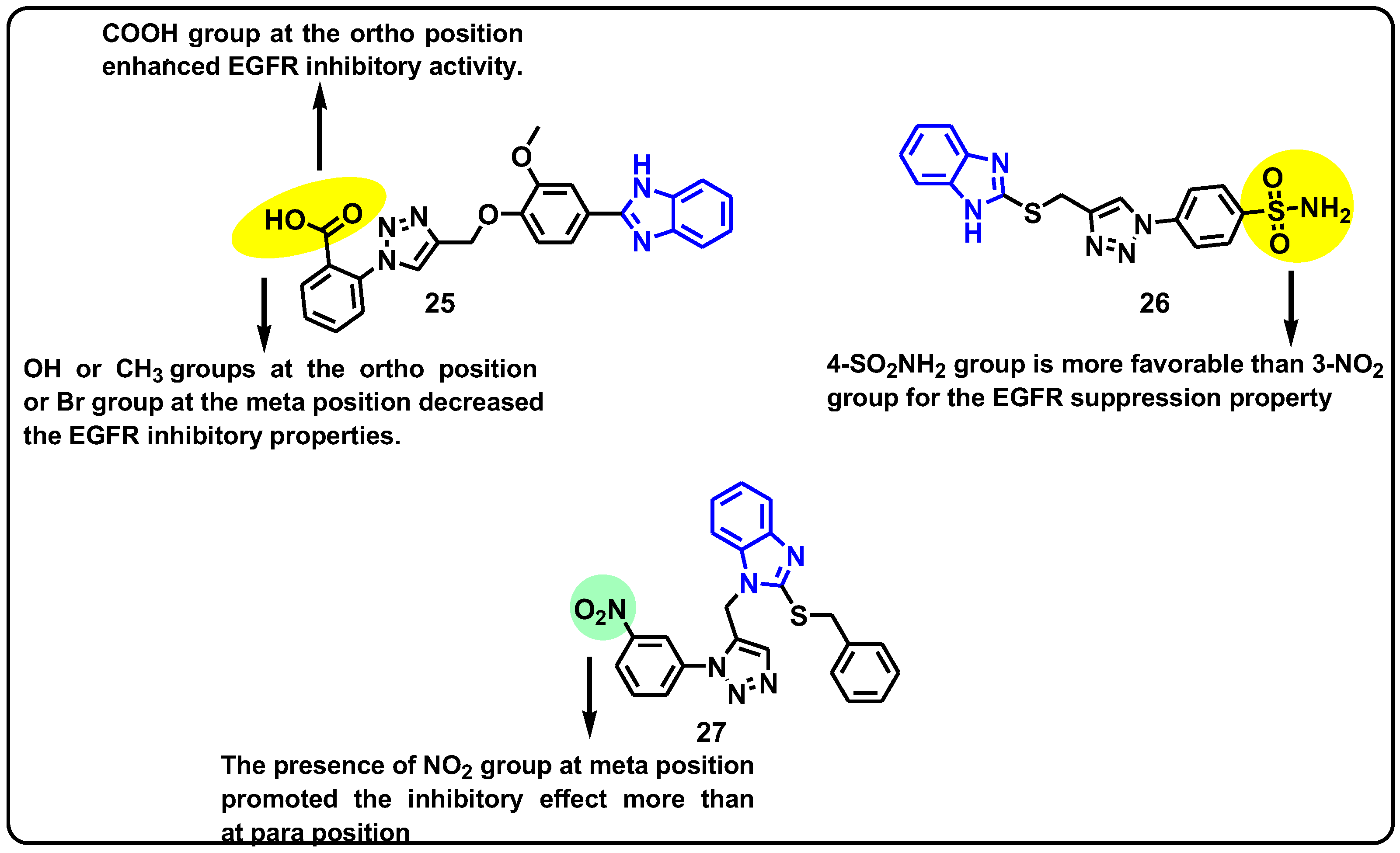

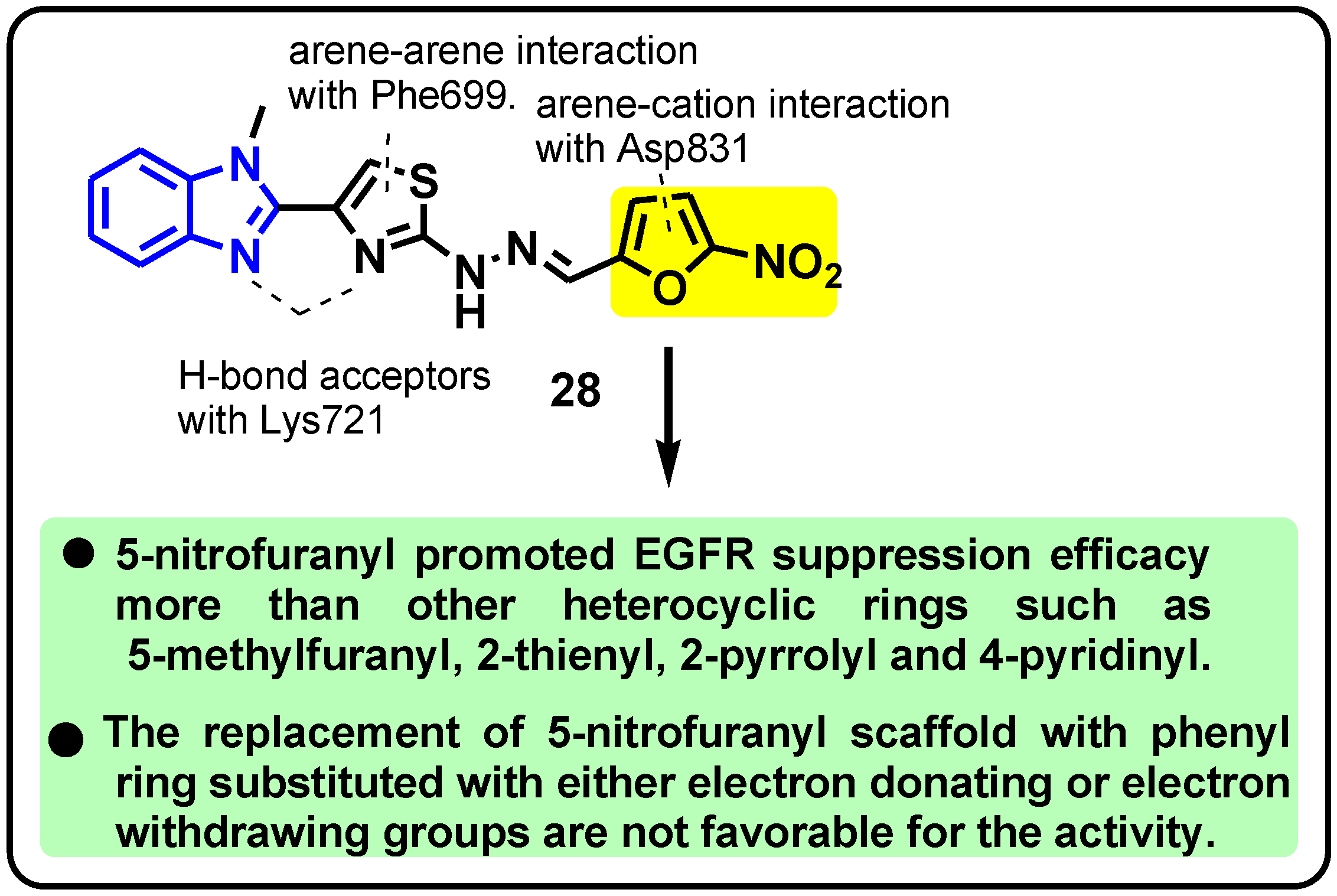

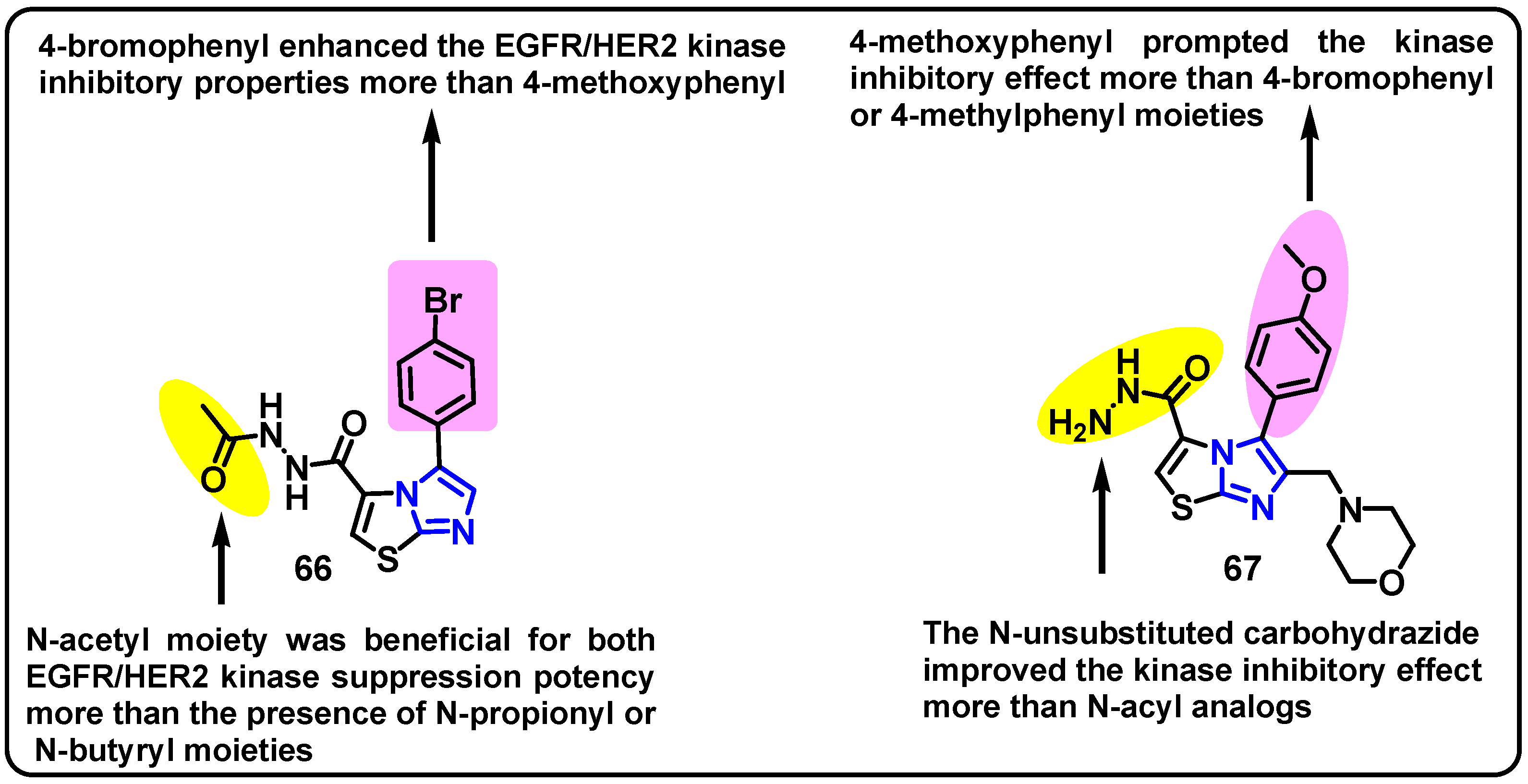

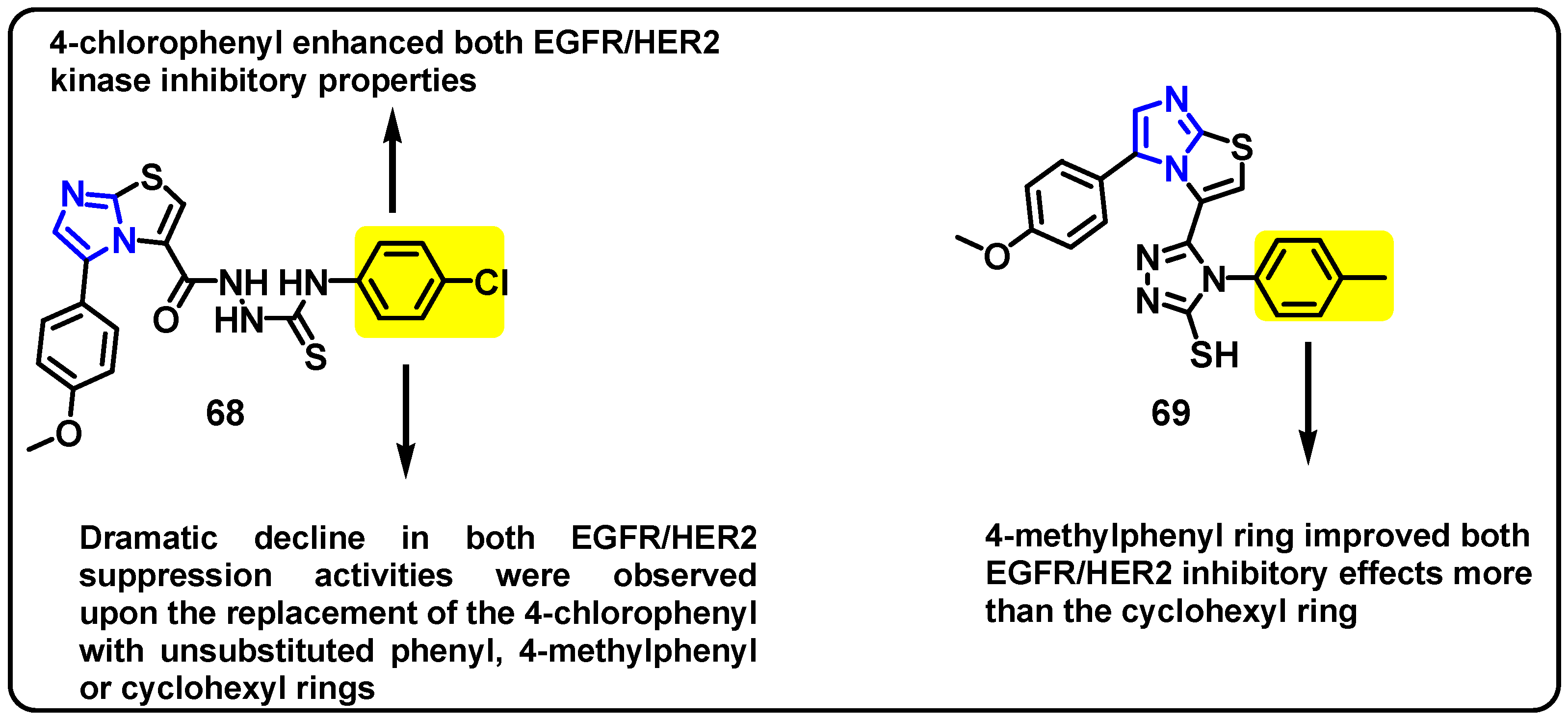

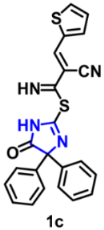

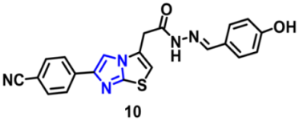

2.1.1. Imidazole-Based Derivatives as EGFR Kinase Inhibitors

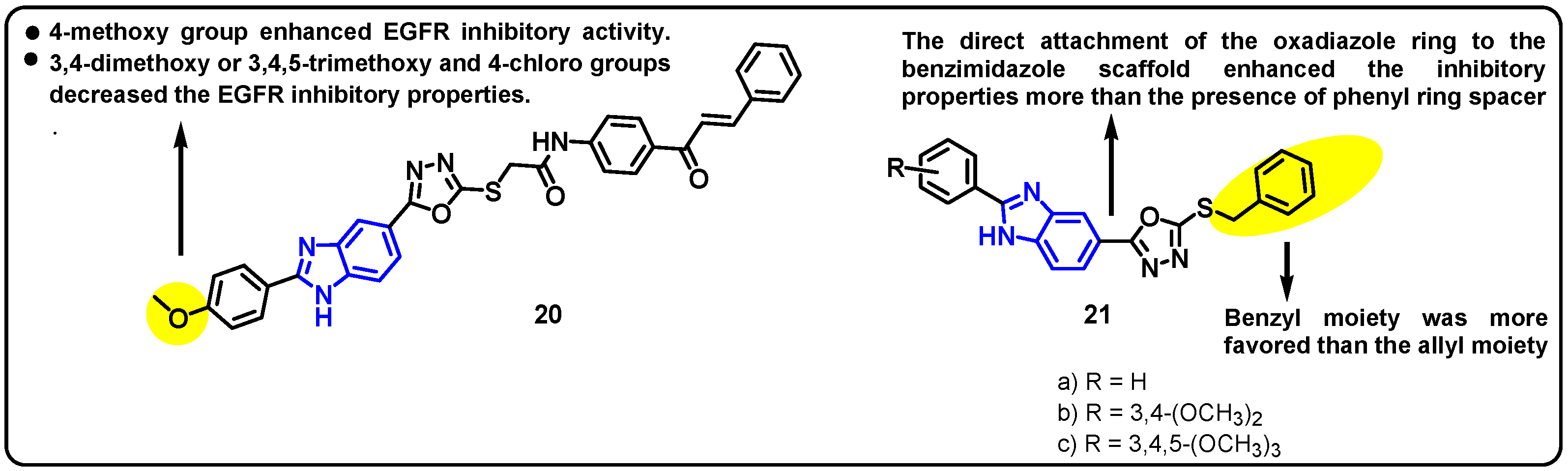

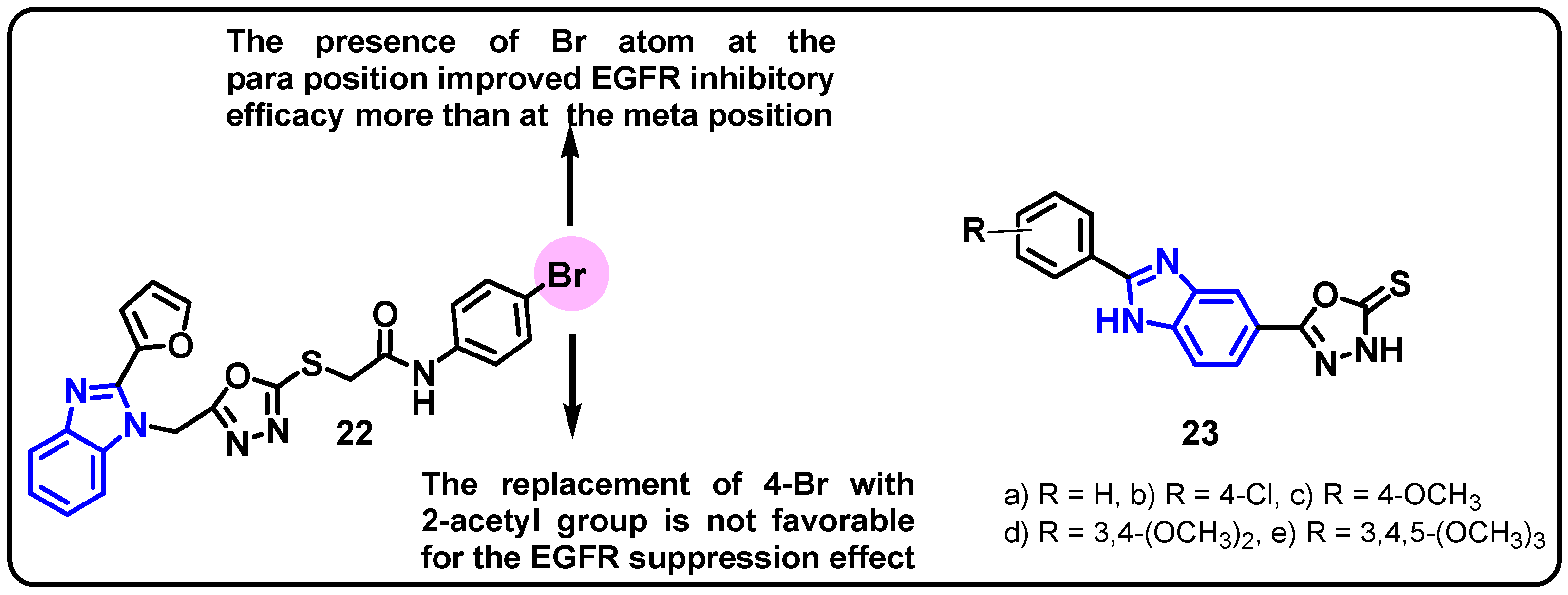

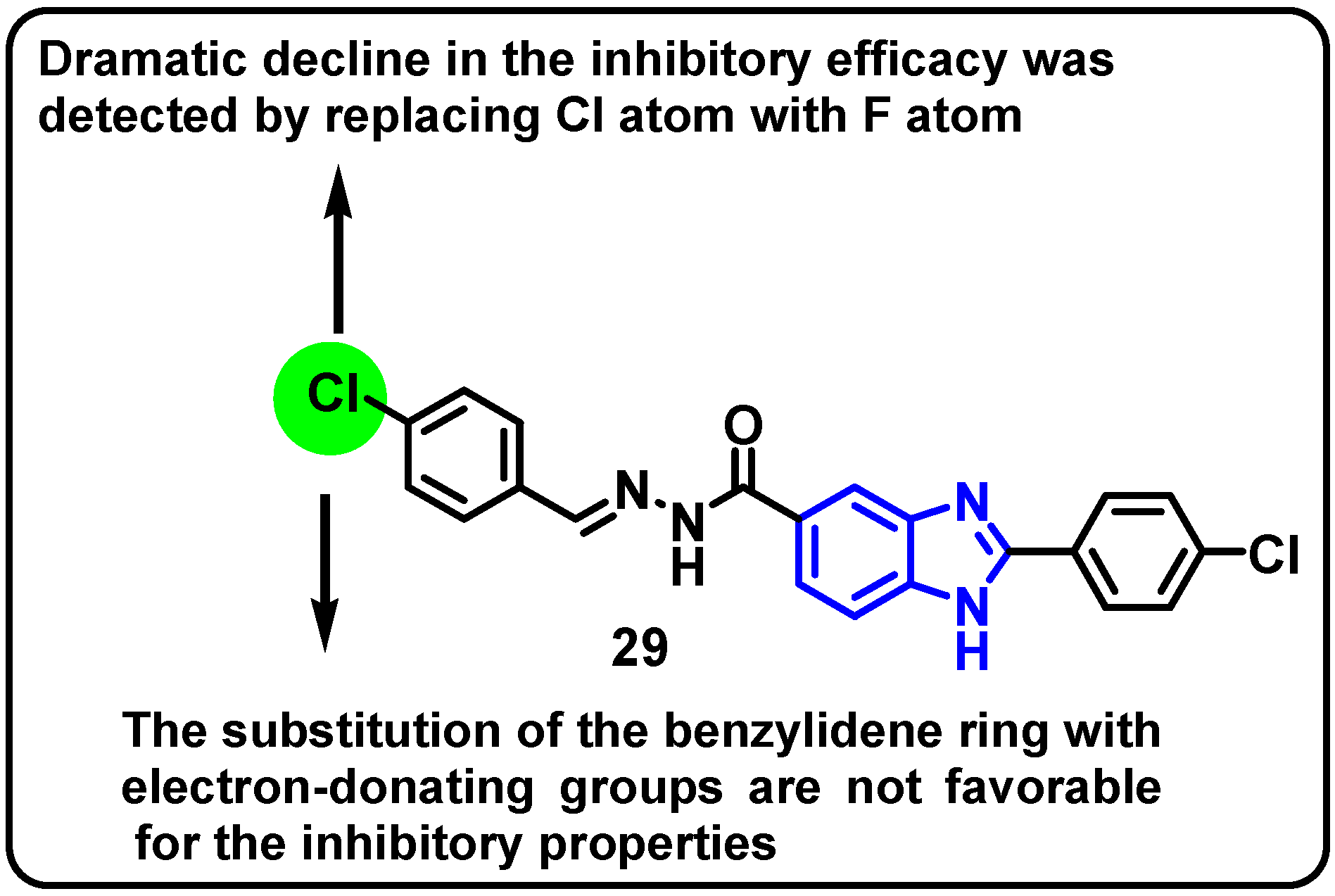

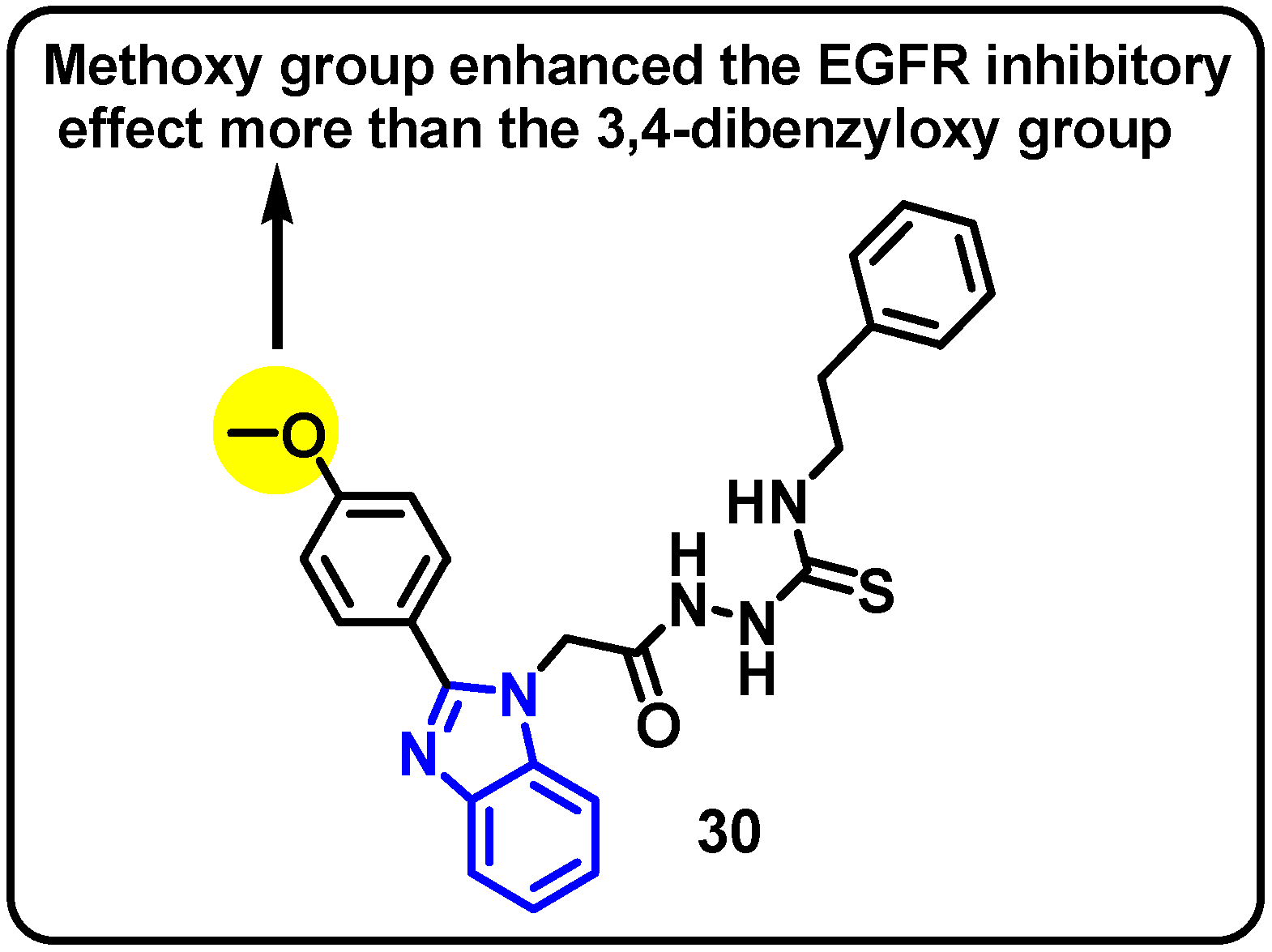

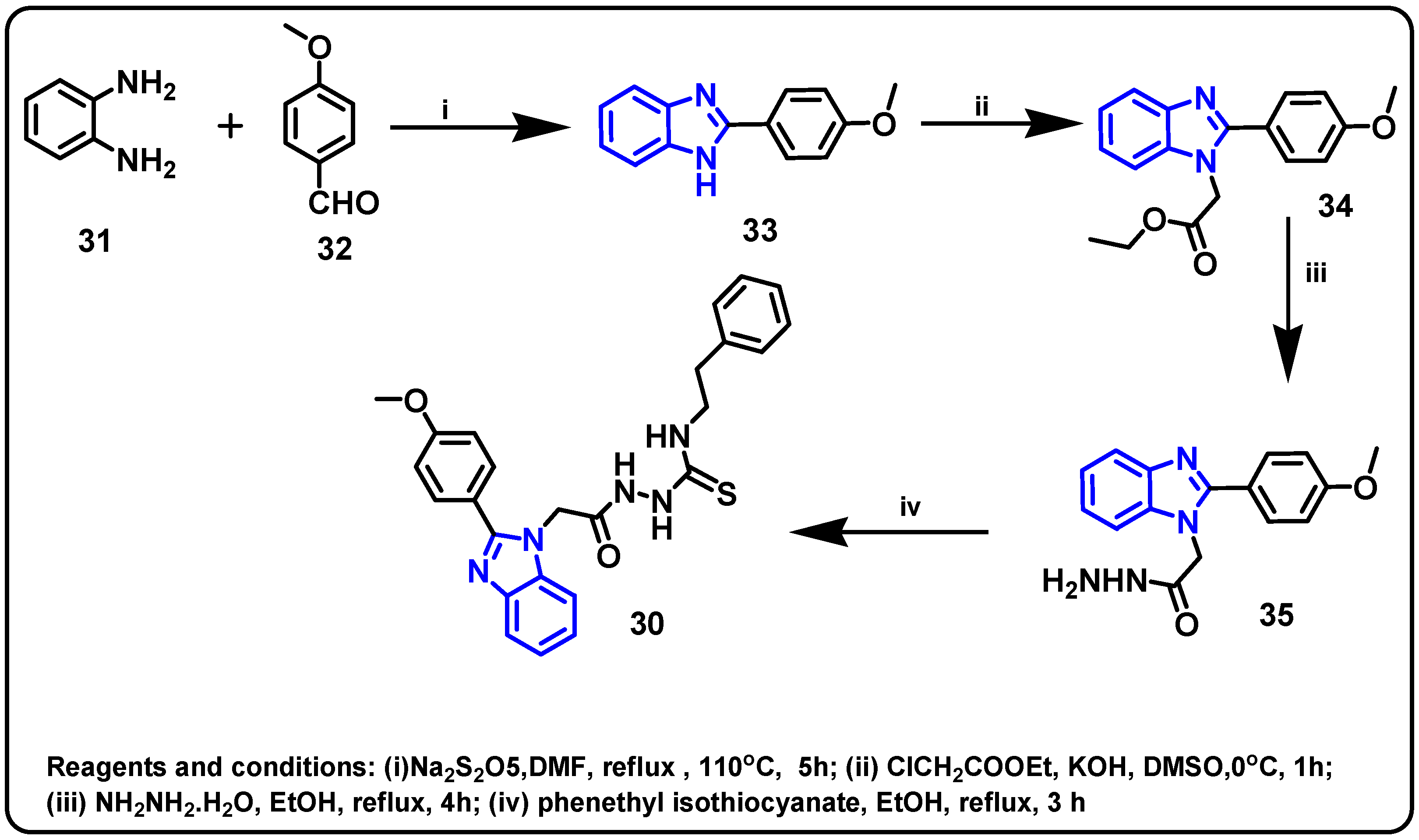

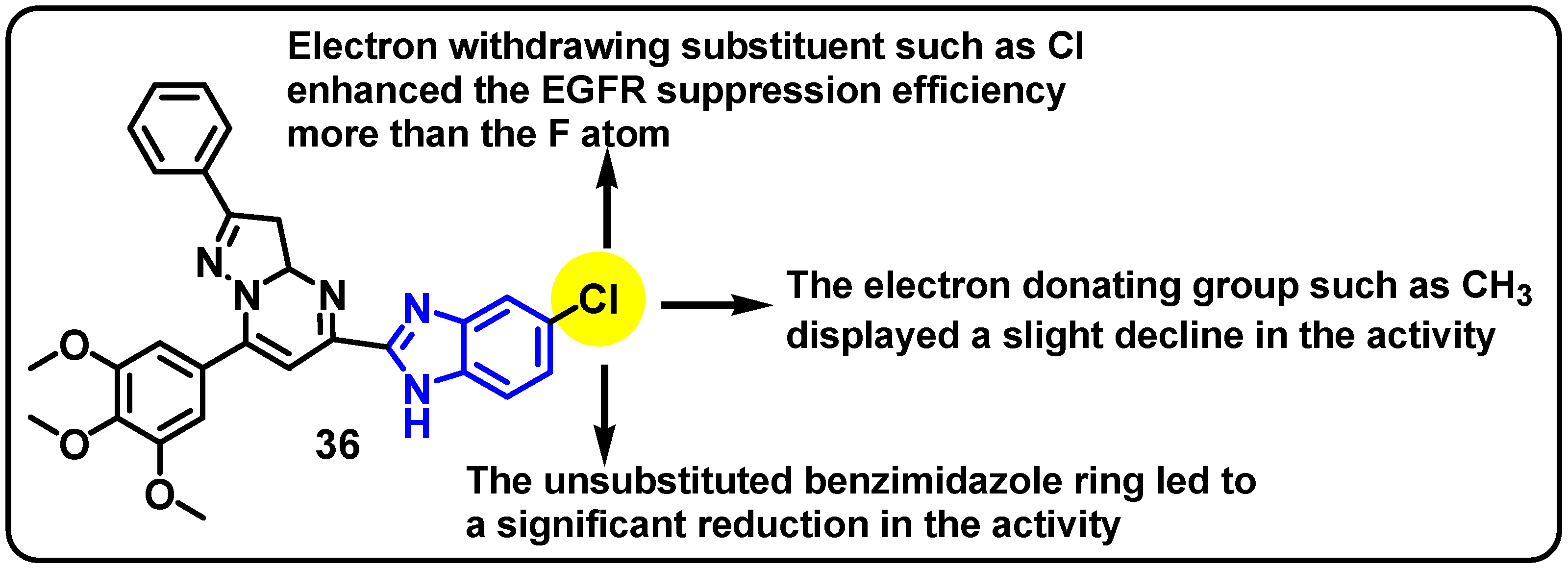

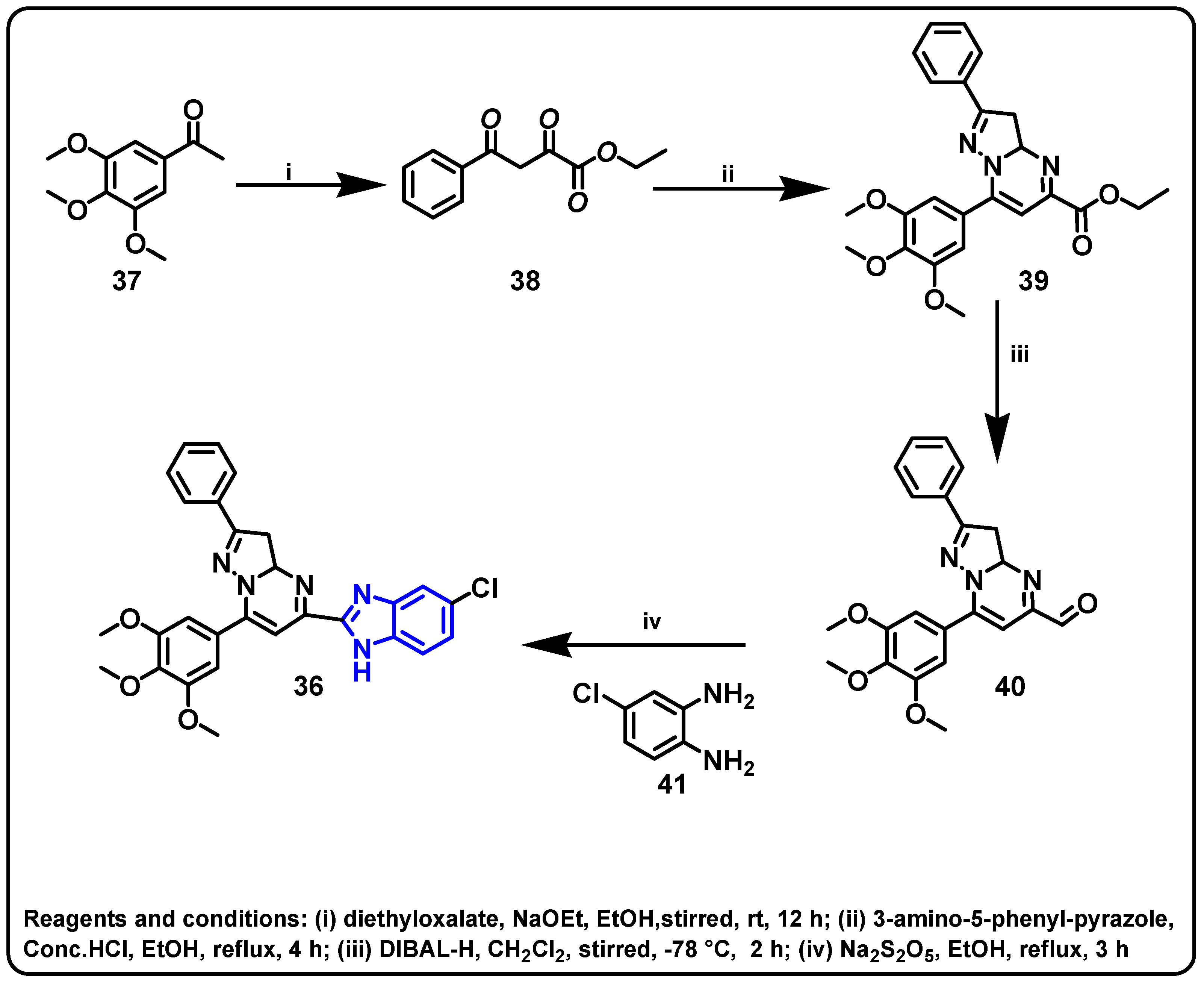

2.1.2. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as EGFR Kinase Inhibitors

2.2. Vascular Endothelia Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR) Inhibitors

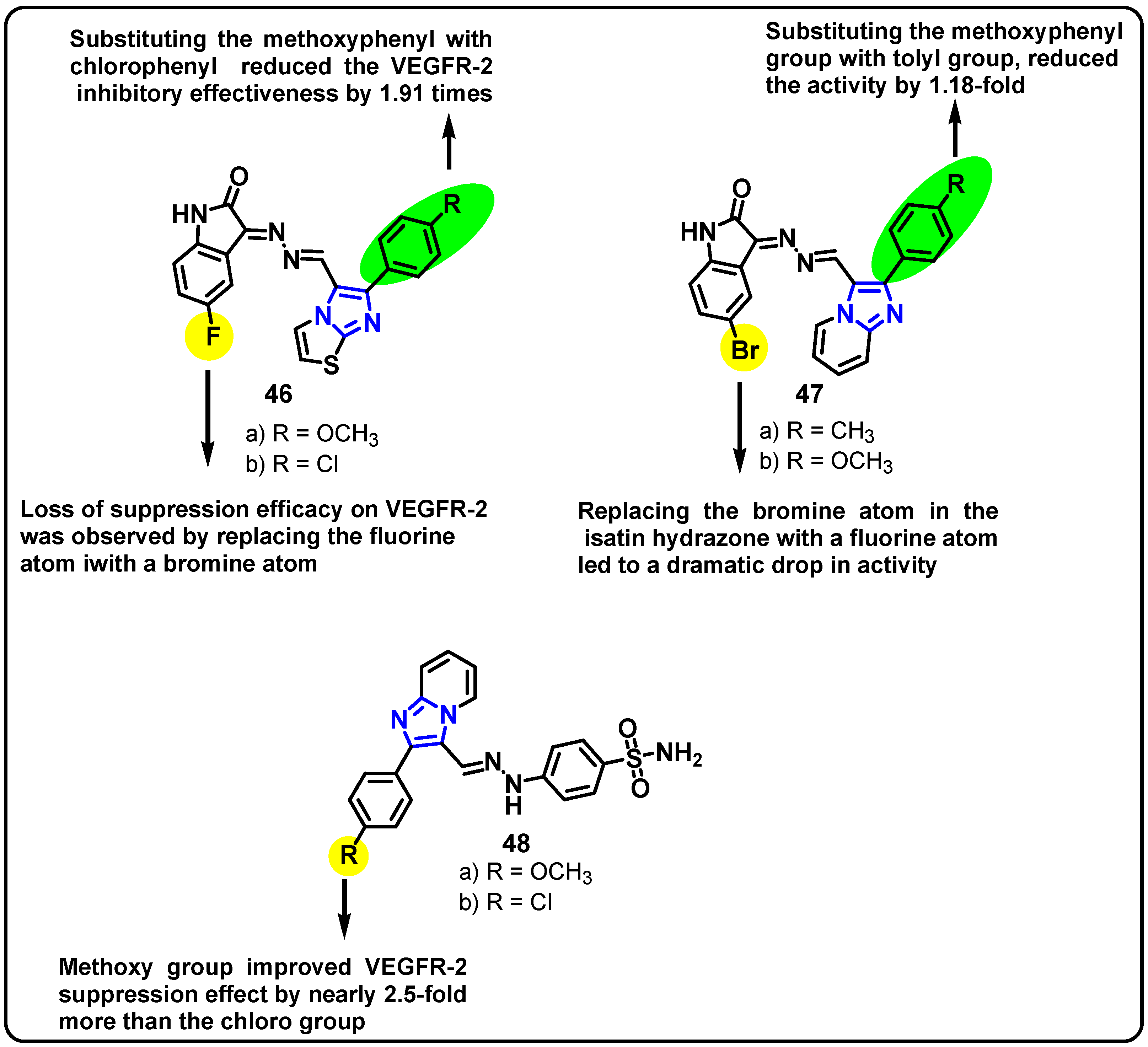

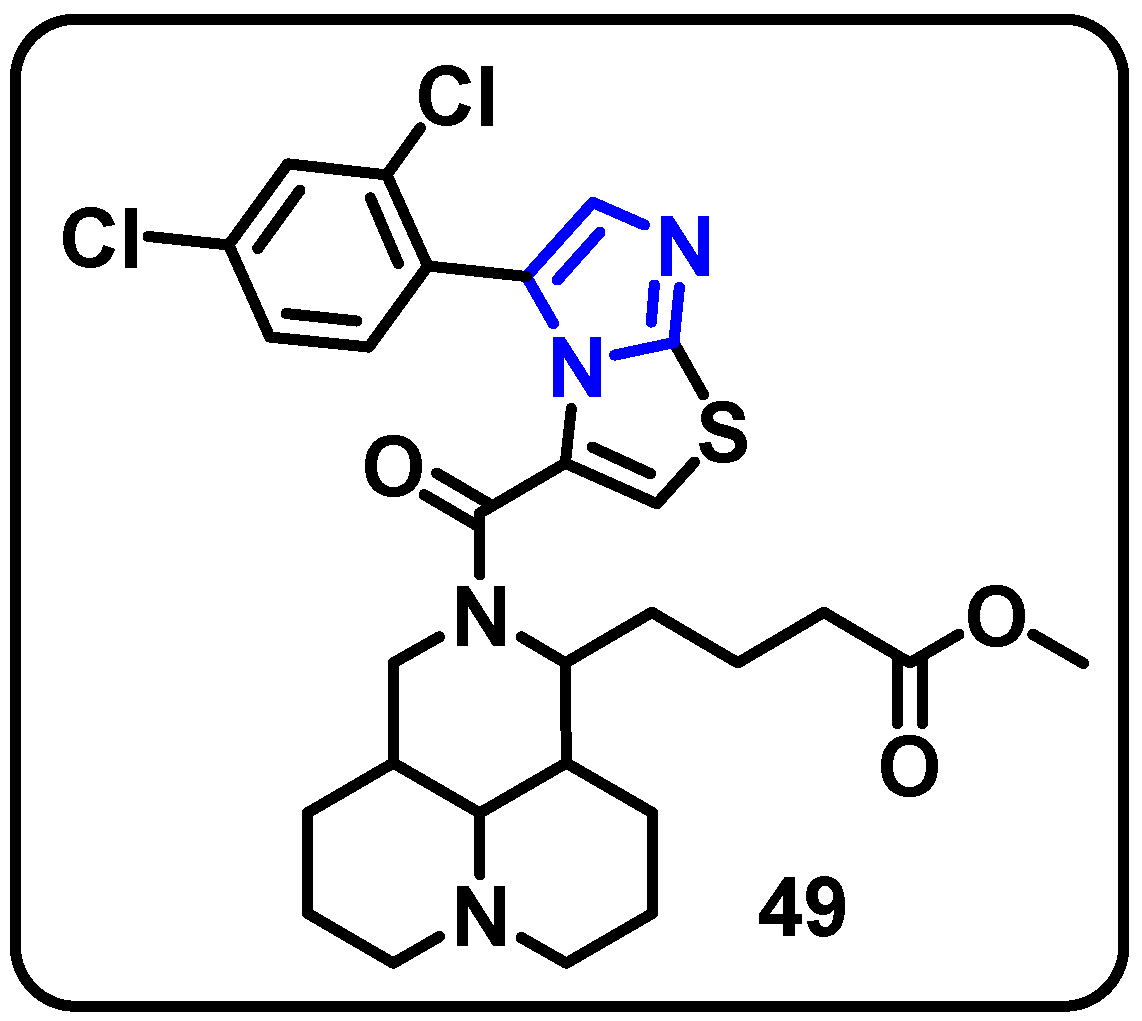

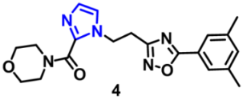

2.2.1. Imidazole-Based Derivatives as VEGFR-2 Kinase Inhibitors

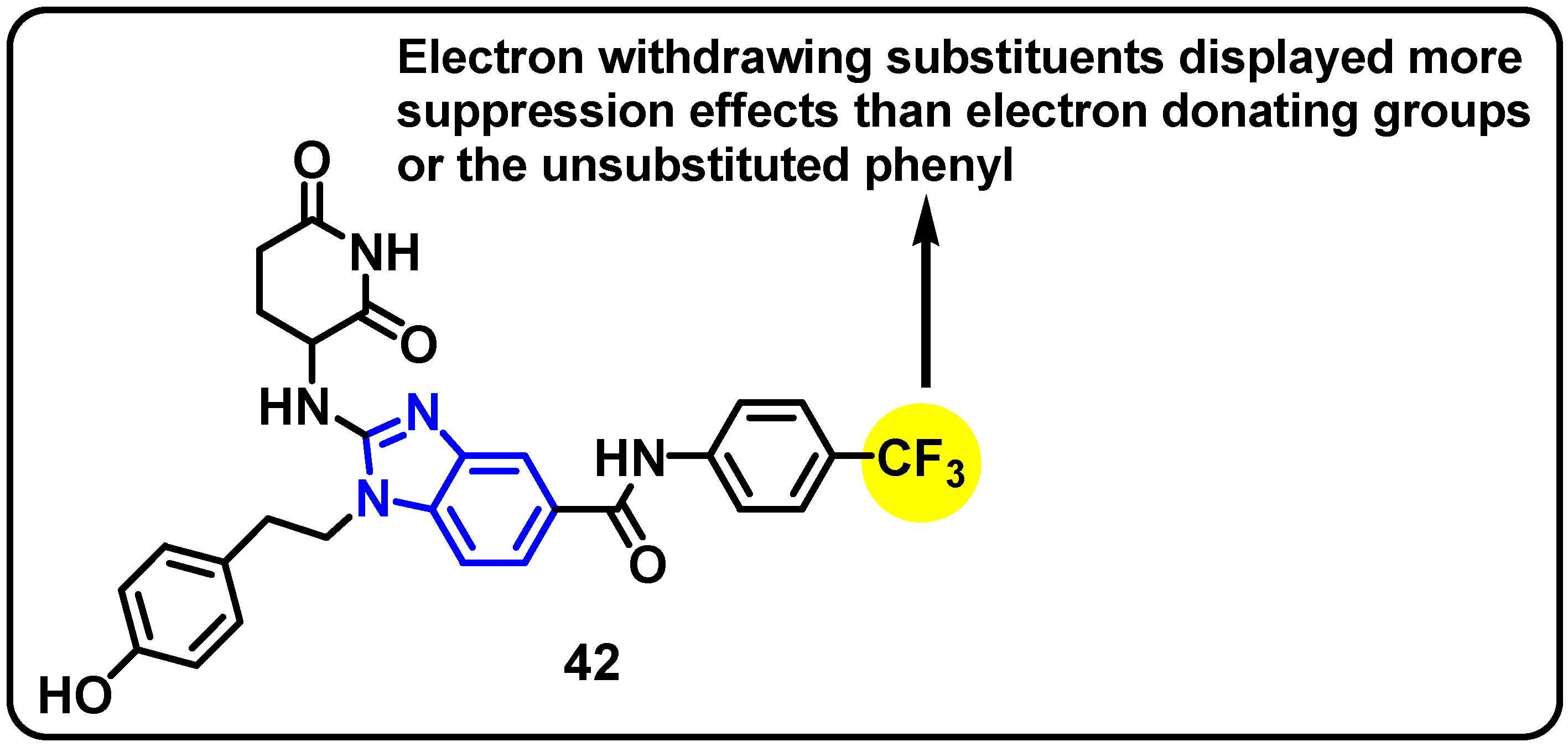

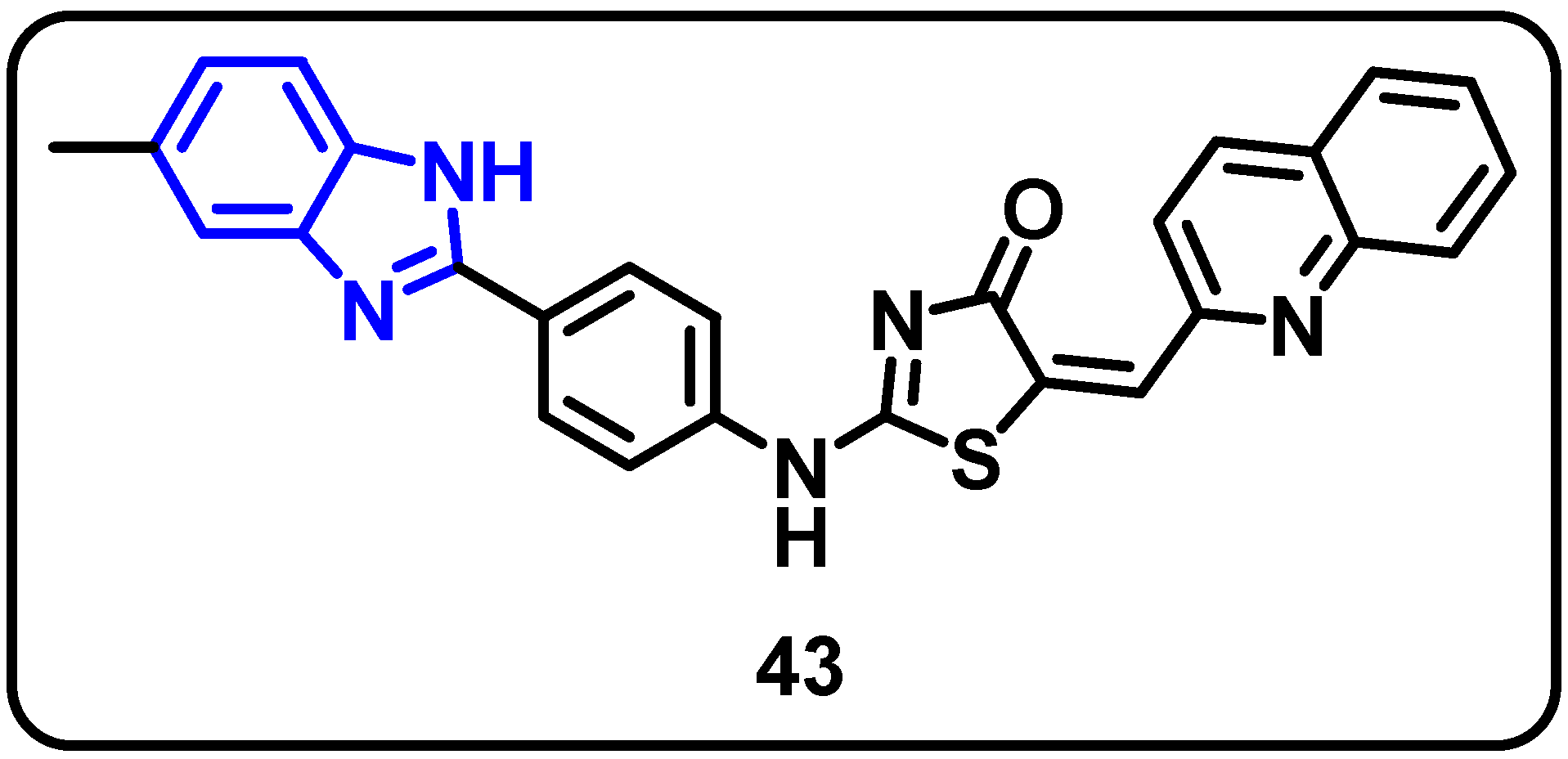

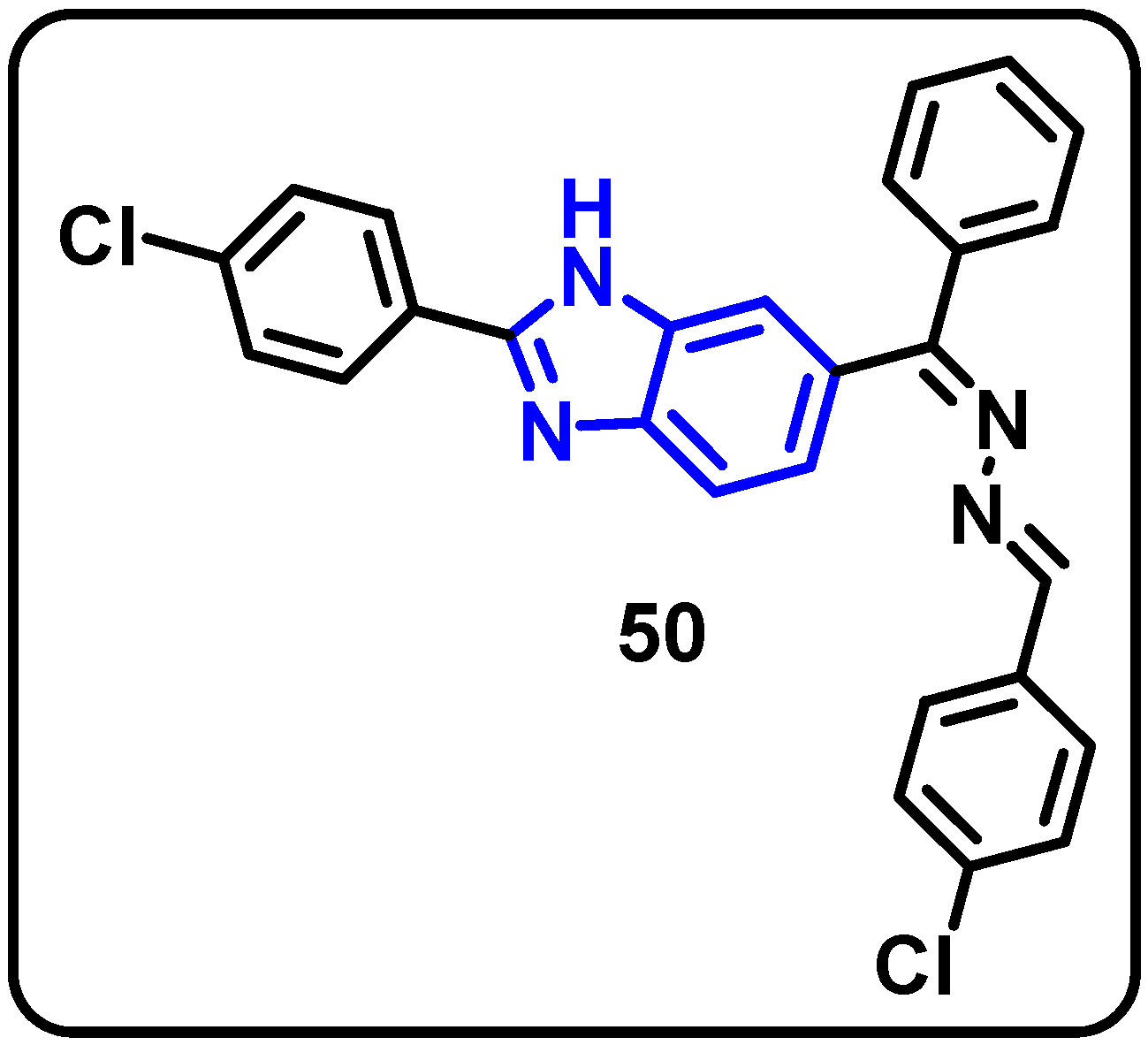

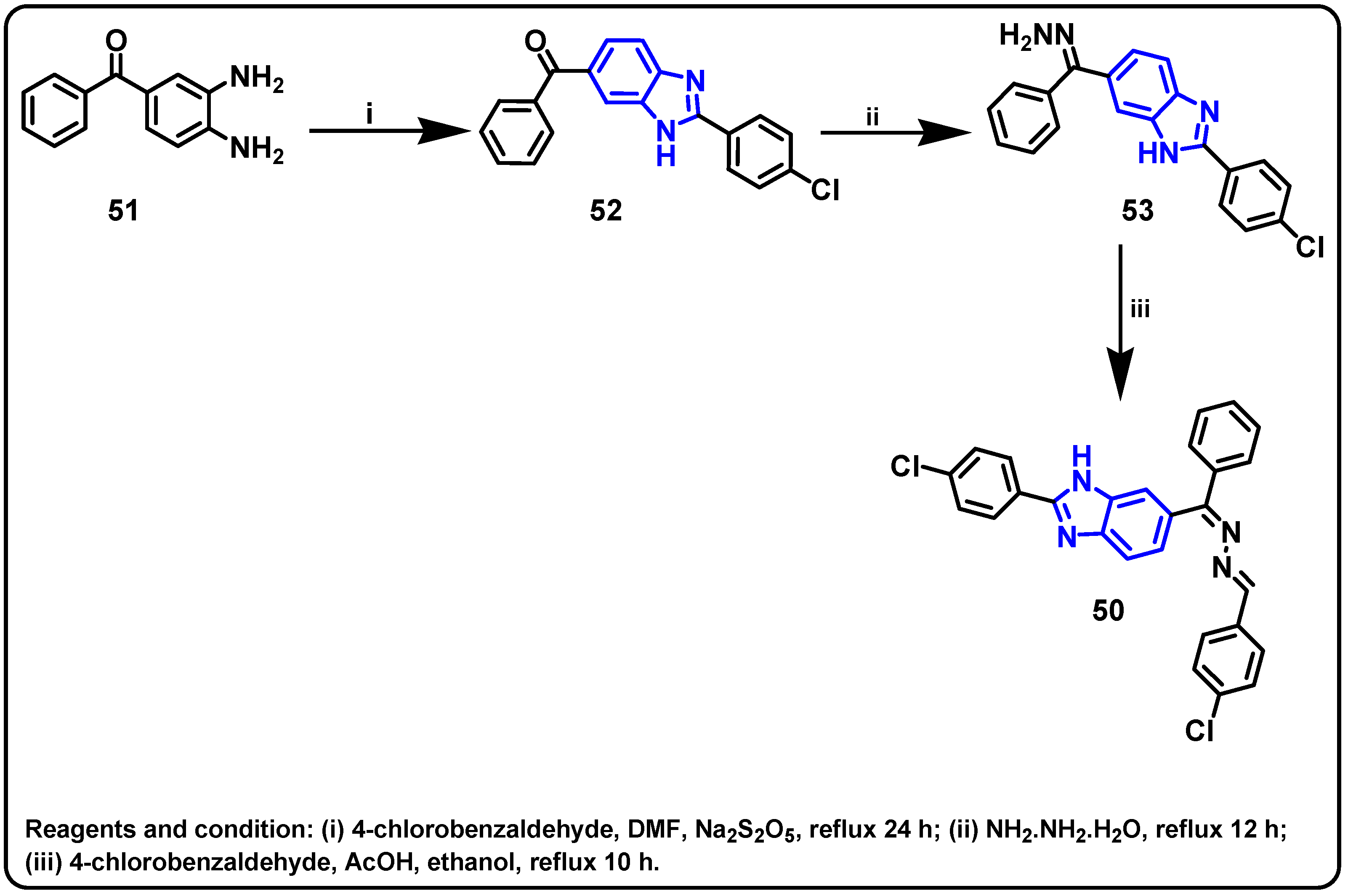

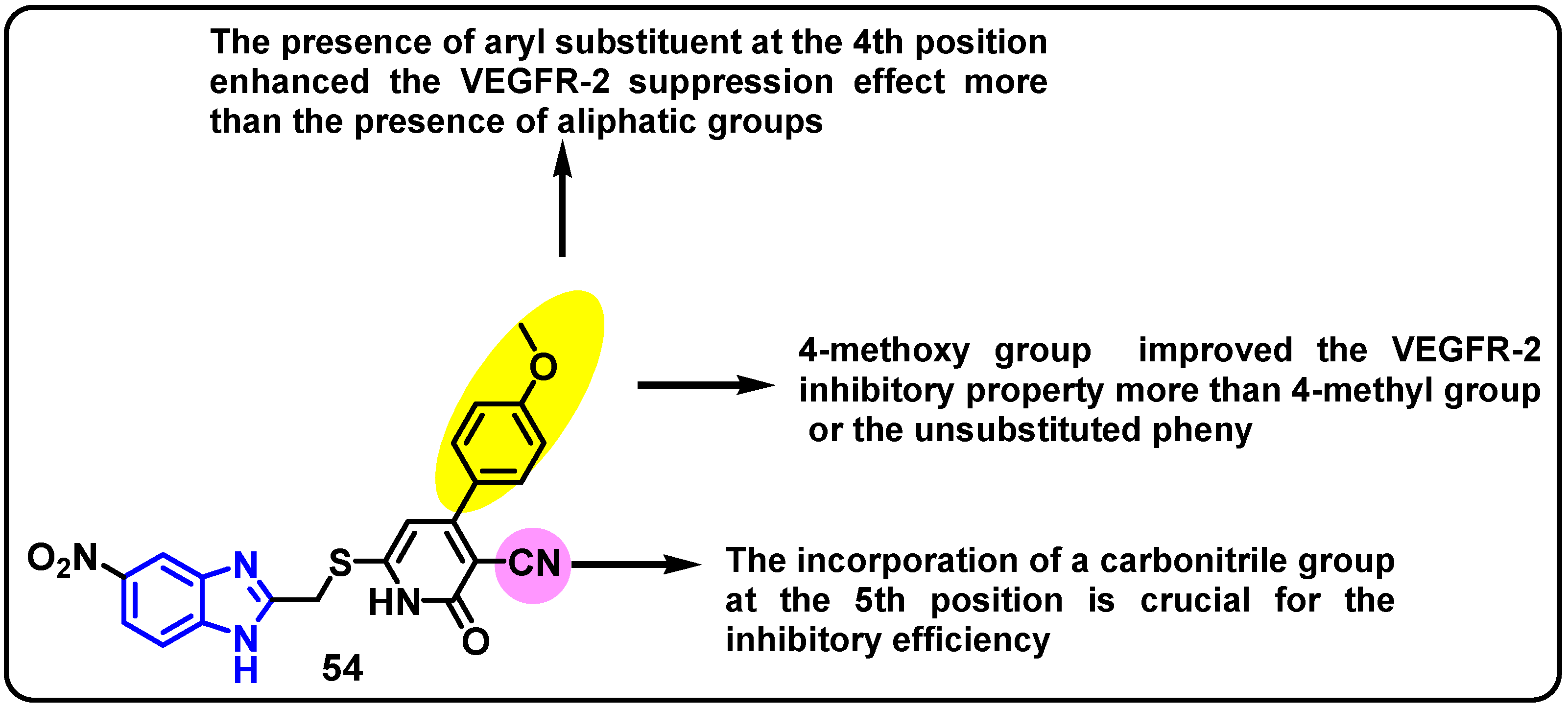

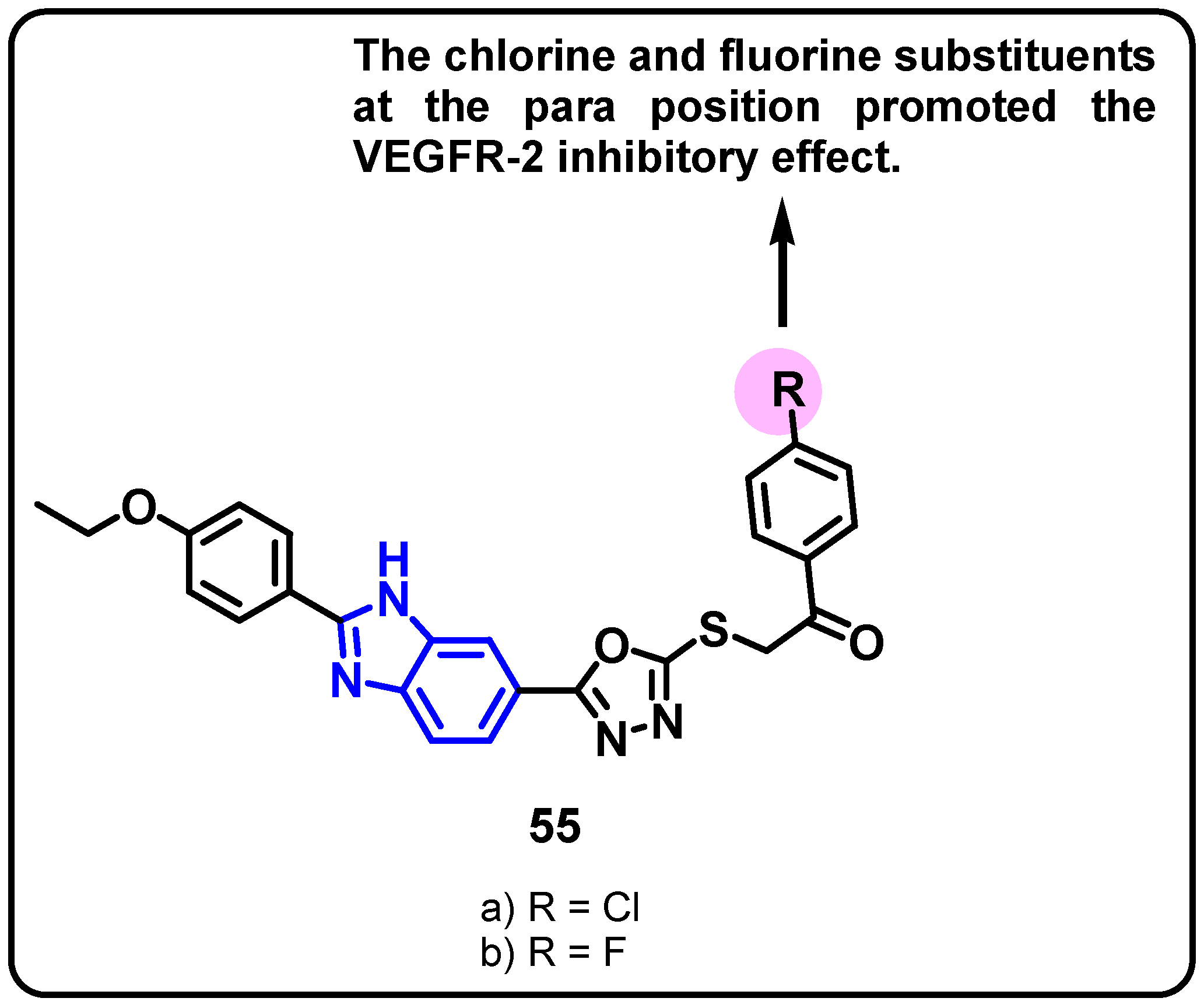

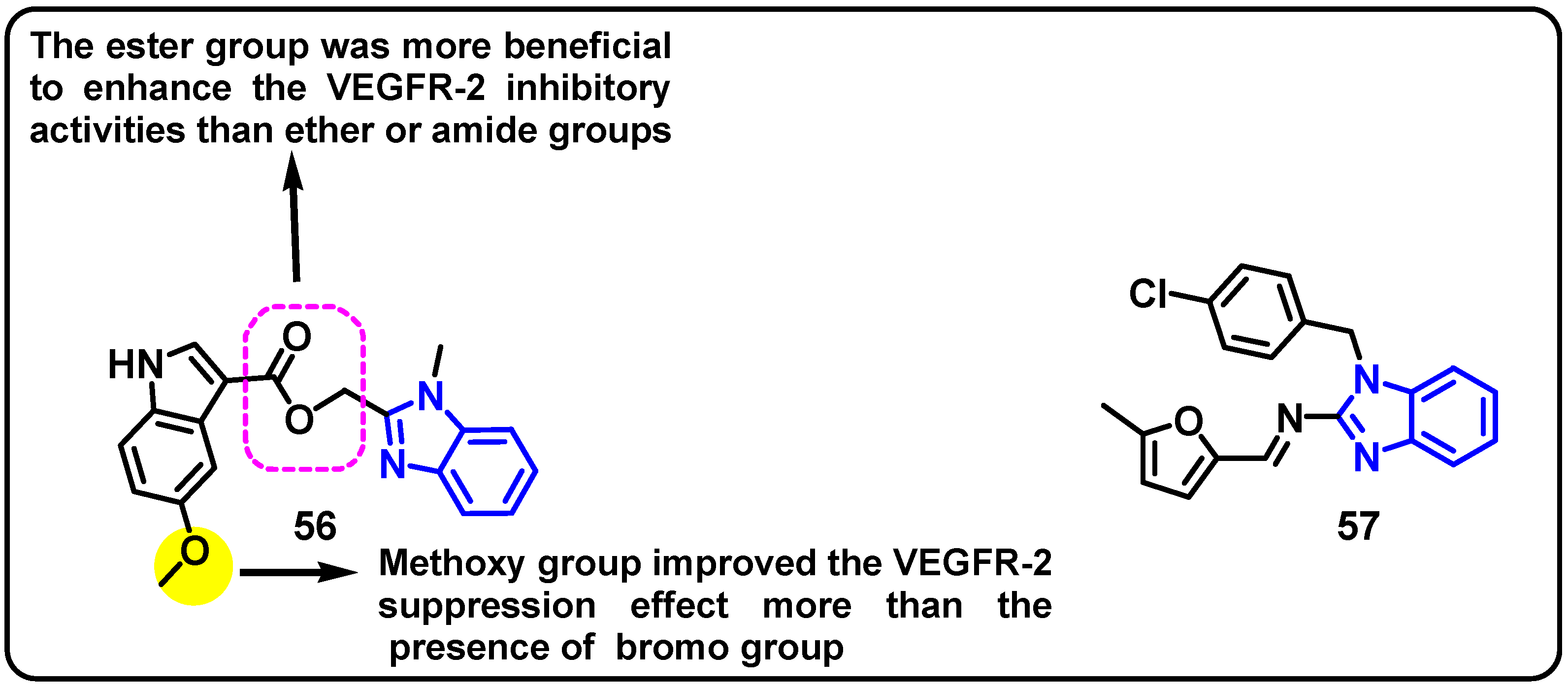

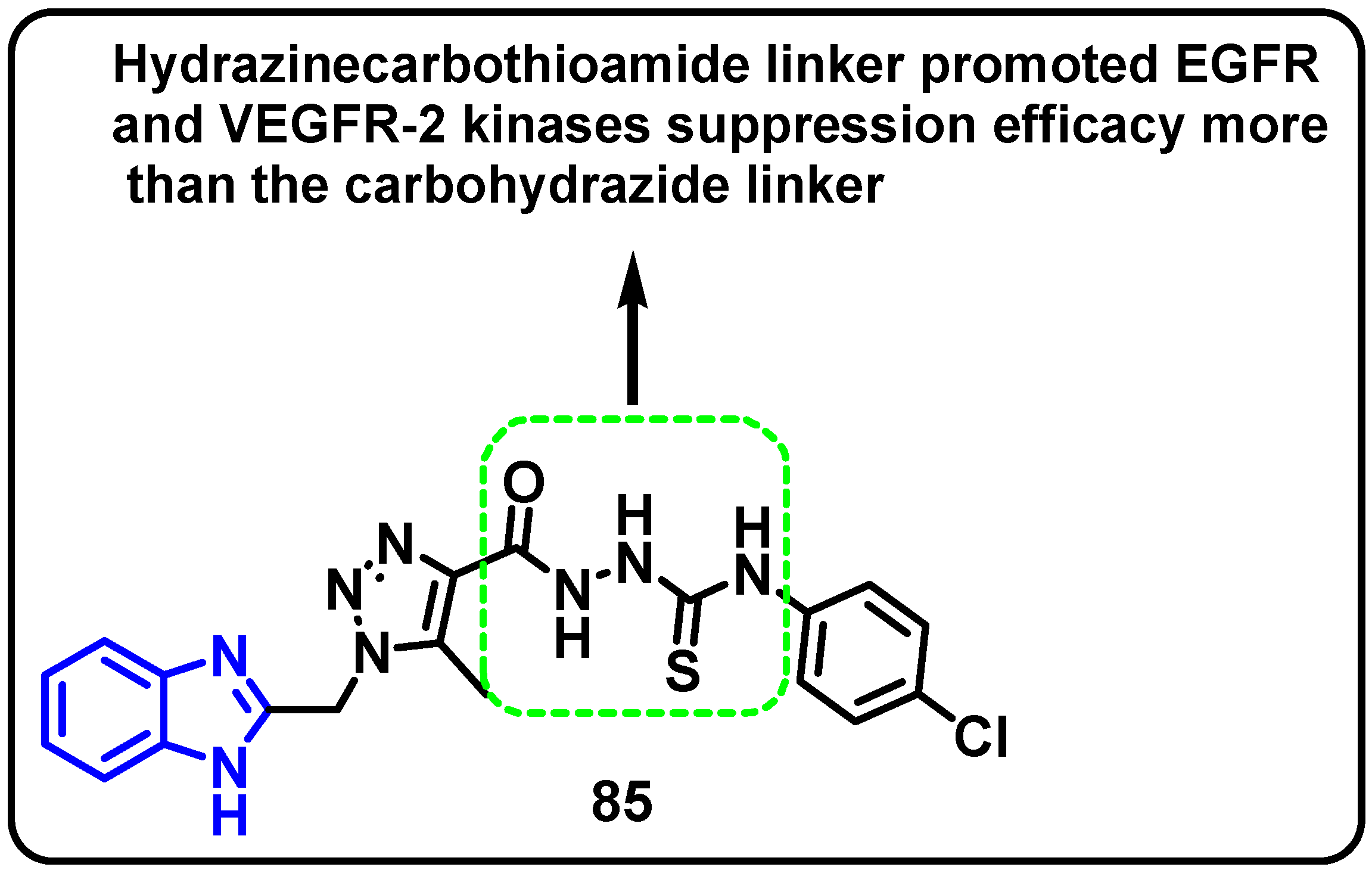

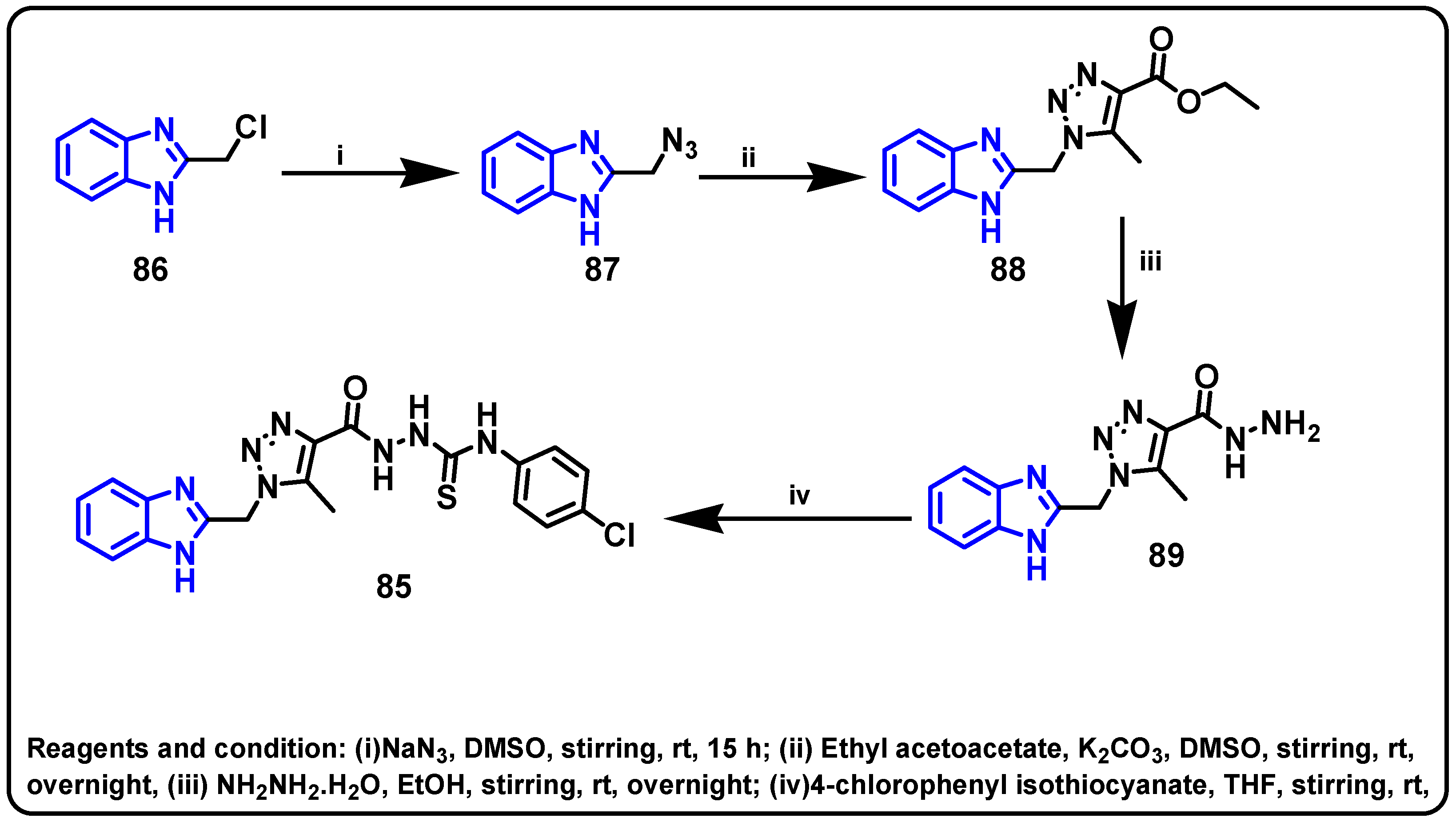

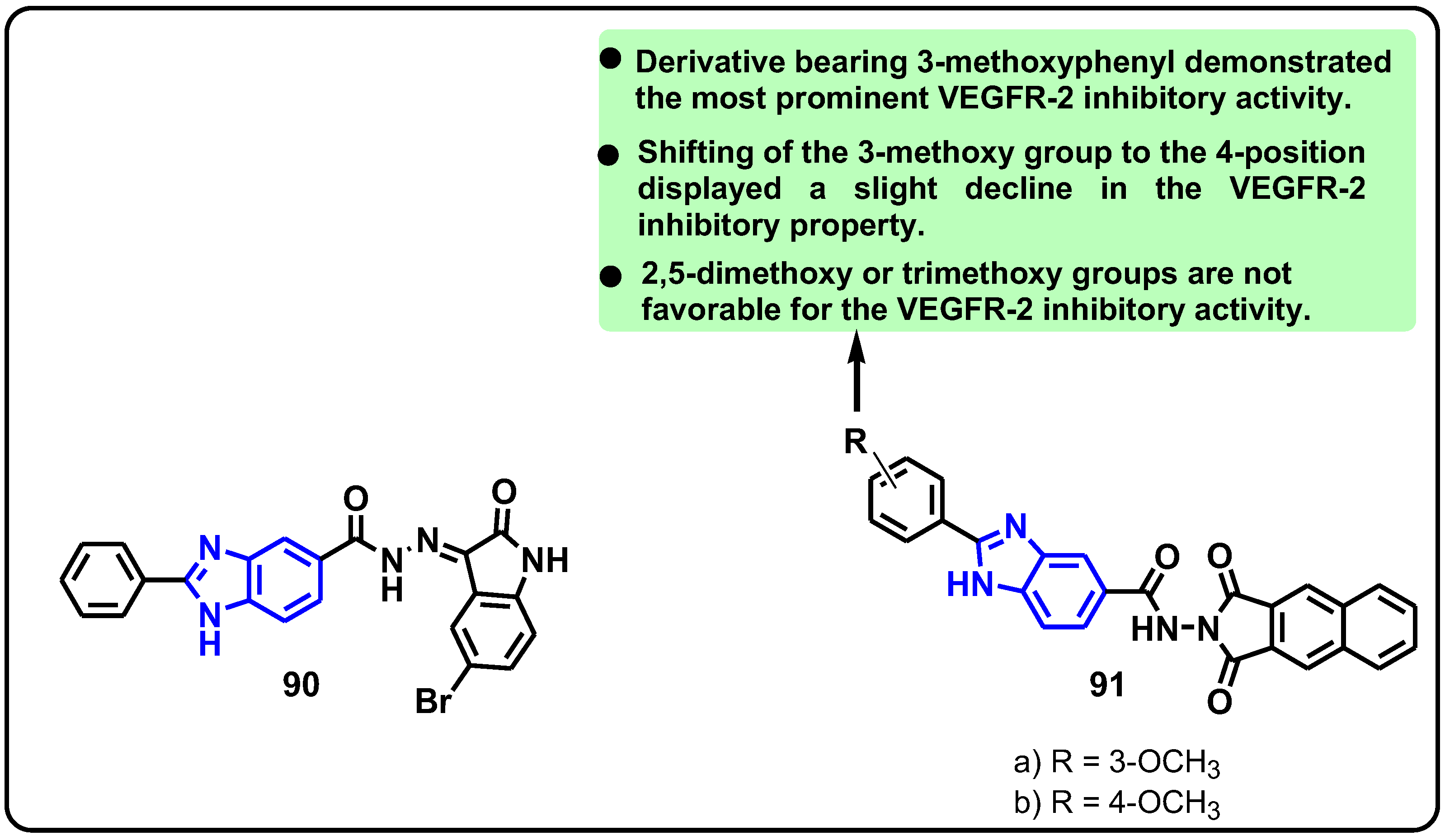

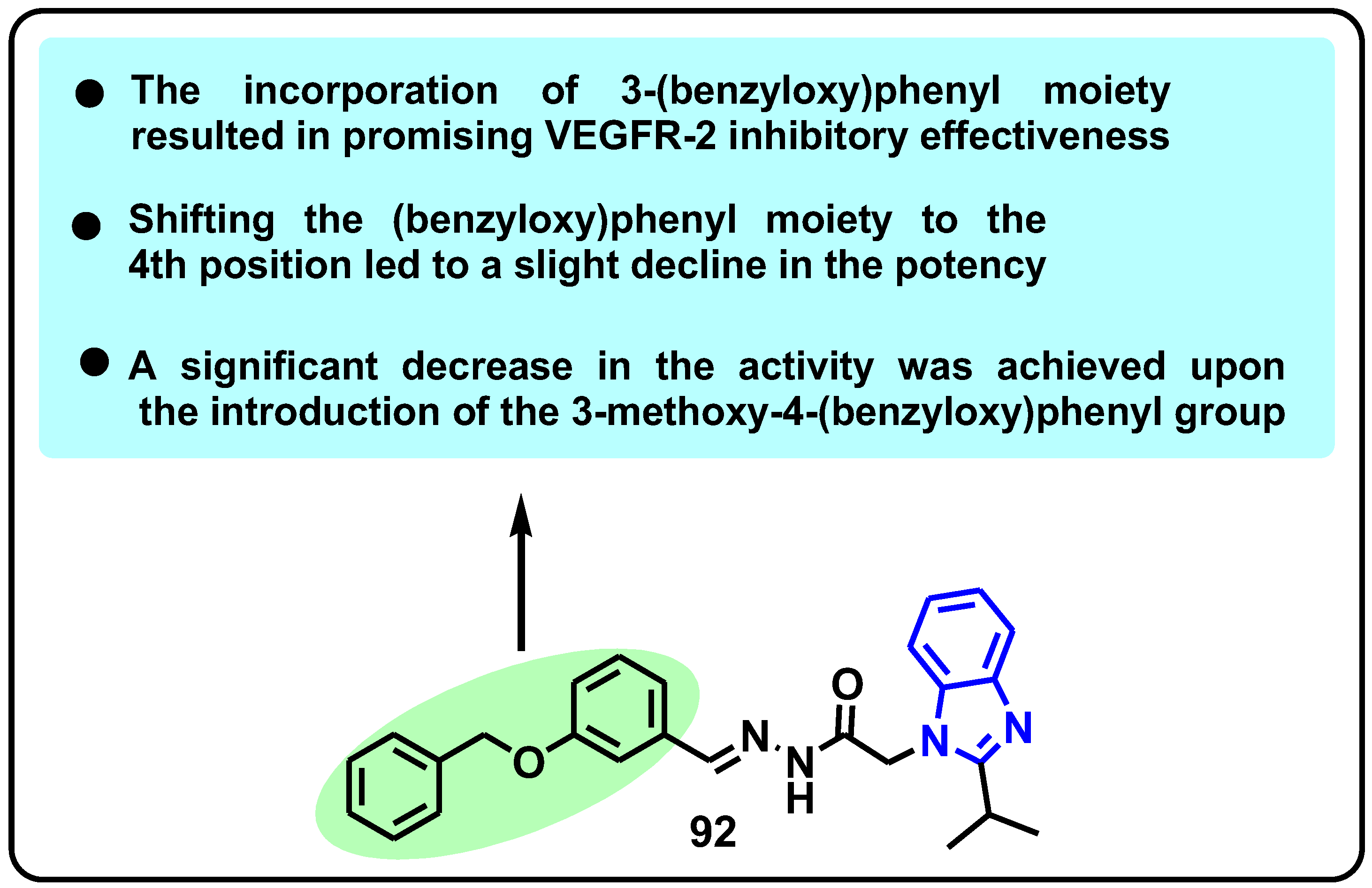

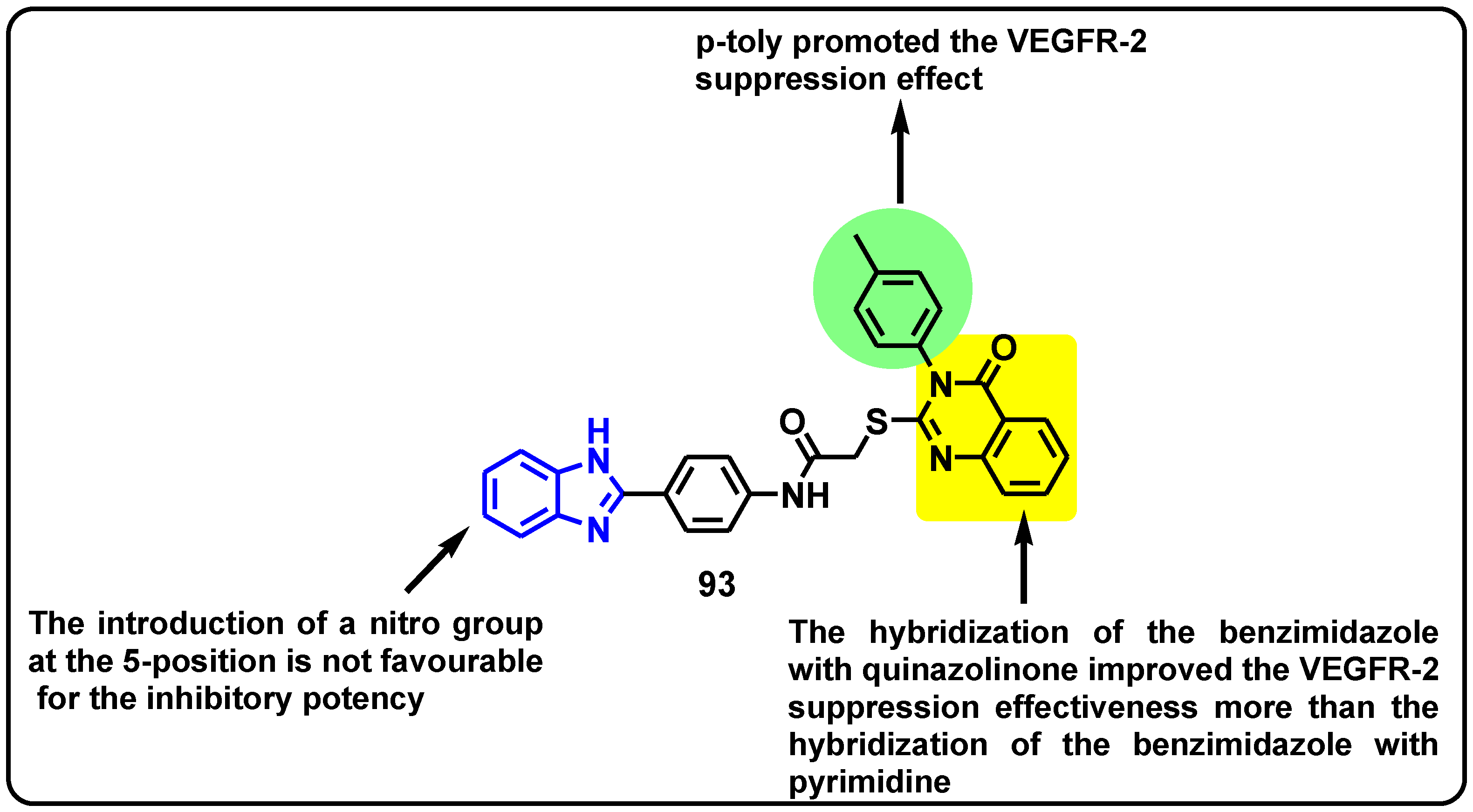

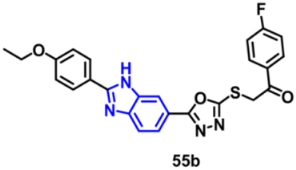

2.2.2. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as VEGFR-2 Kinase Inhibitors

2.3. c-Met Kinase Inhibitors

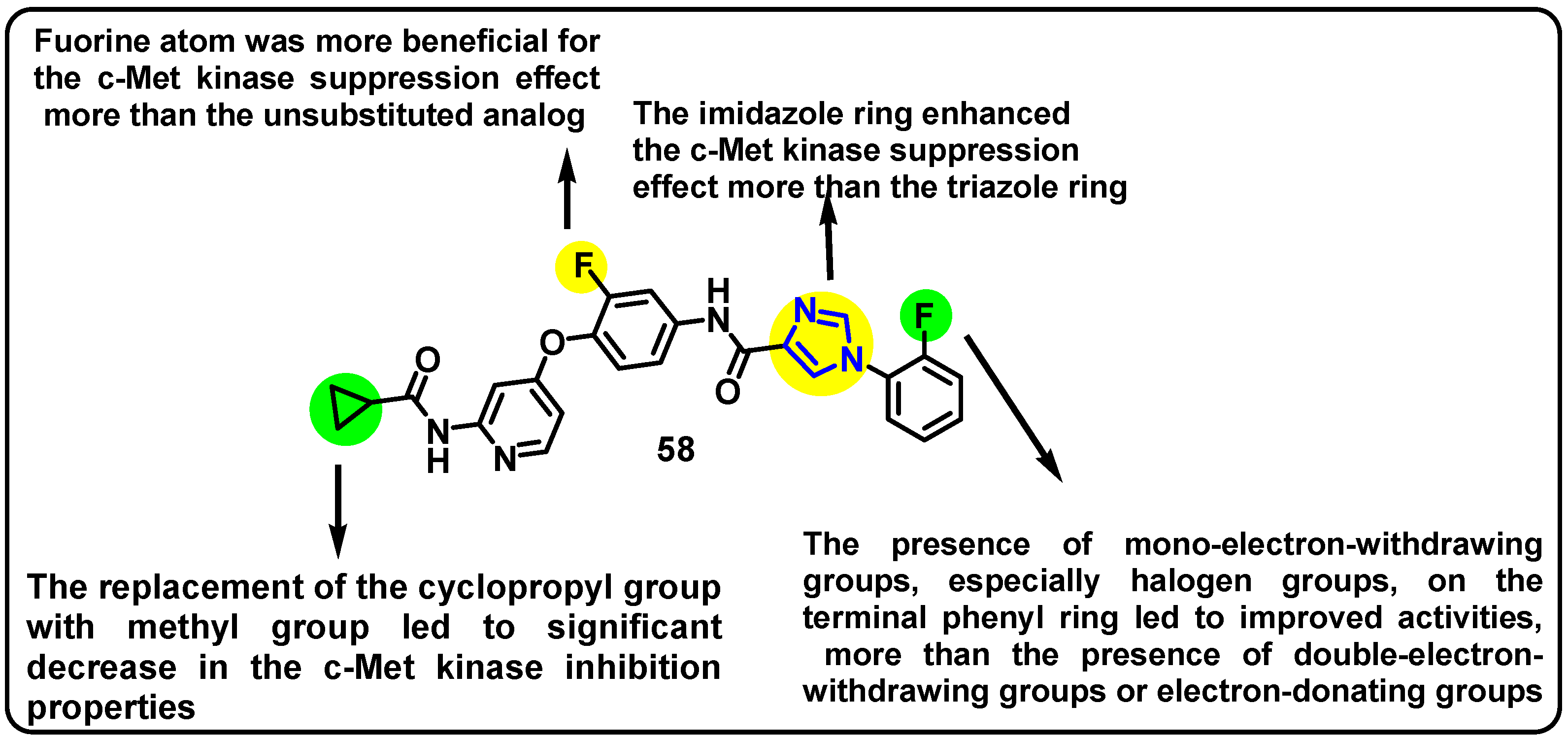

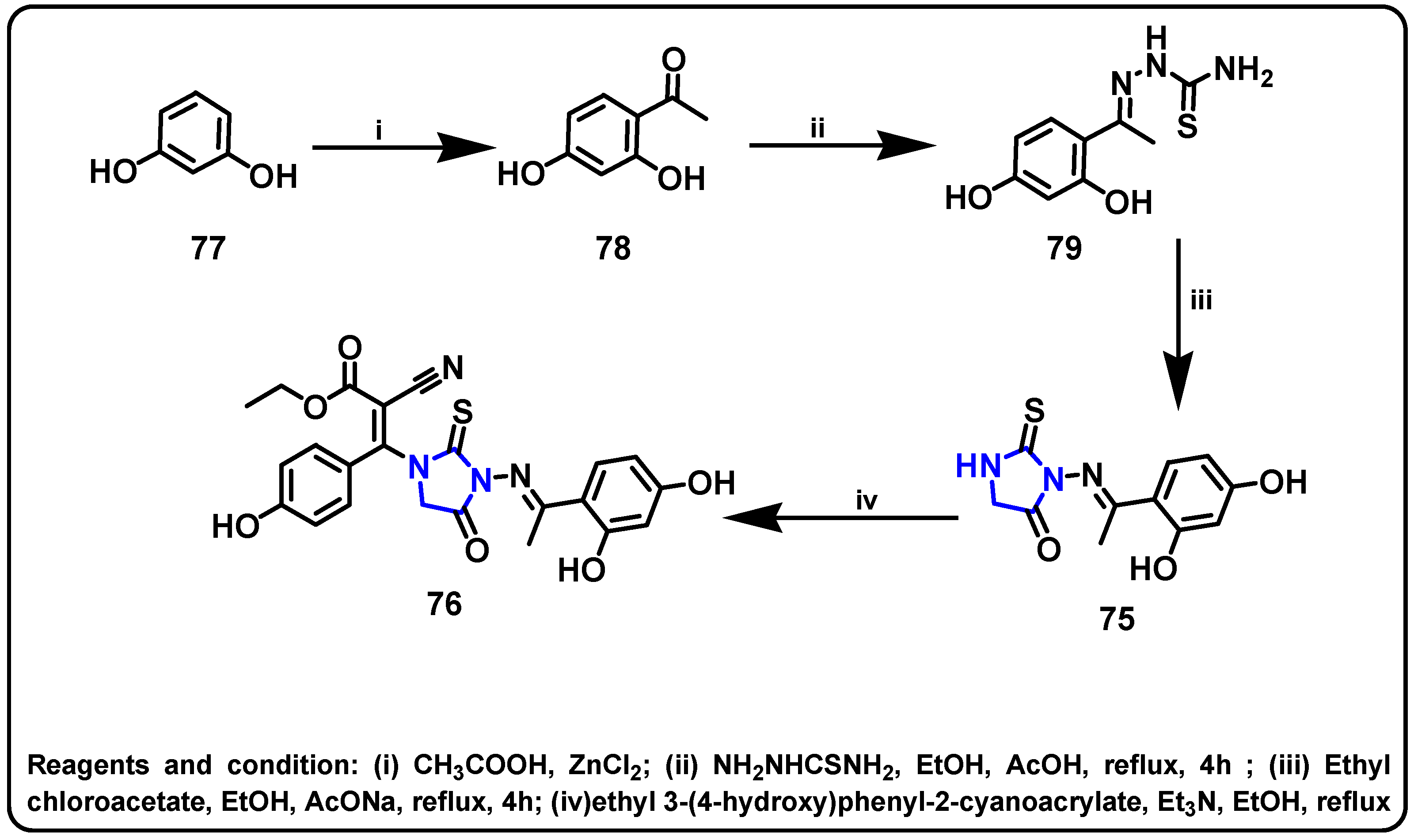

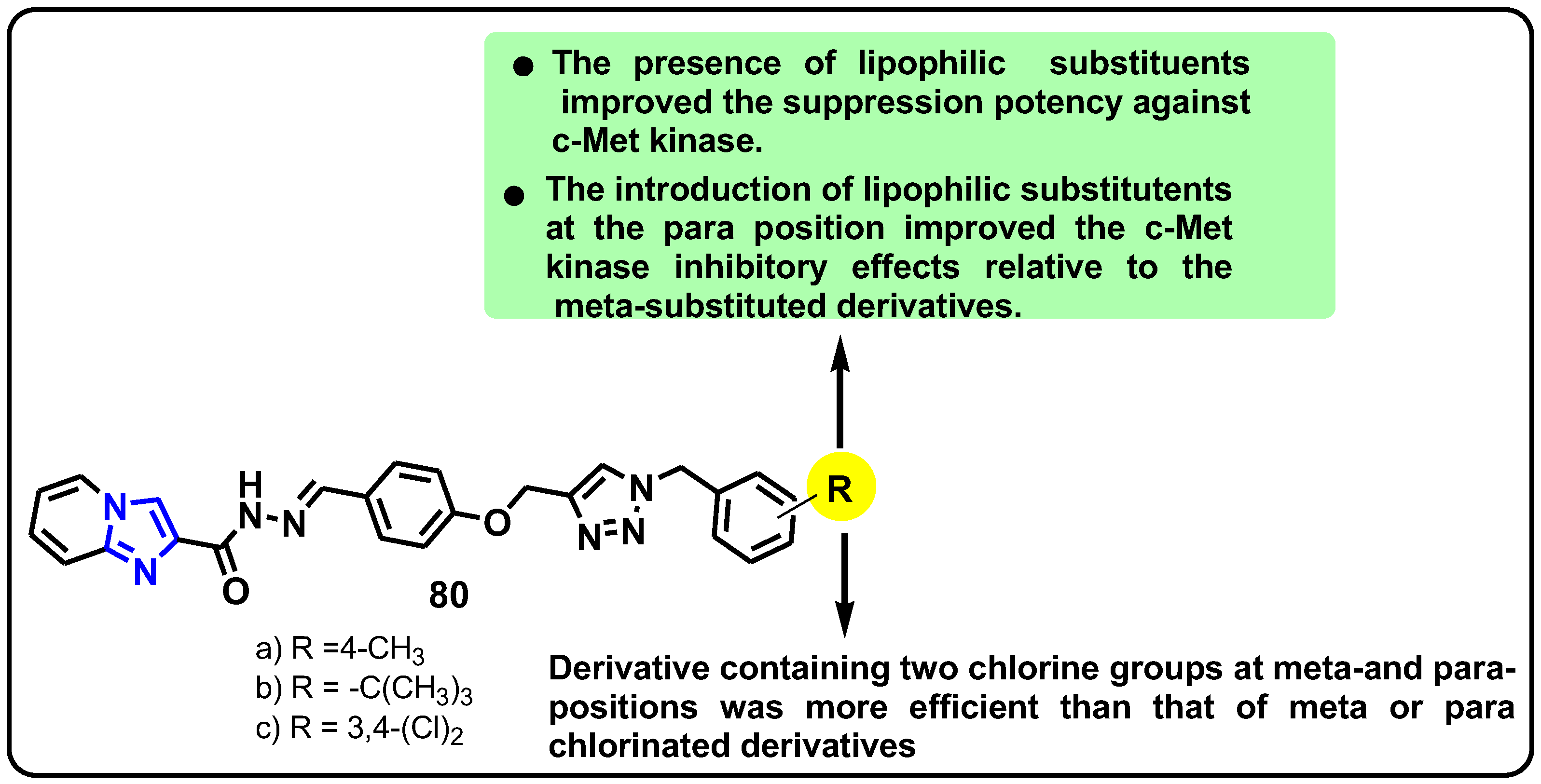

Imidazole-Based Derivatives as c-Met Kinase Inhibitor

2.4. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors (FGFR) Inhibitors

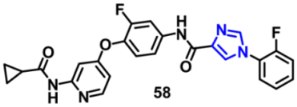

2.4.1. Imidazole-Based Derivatives as FGFR Kinase Inhibitor

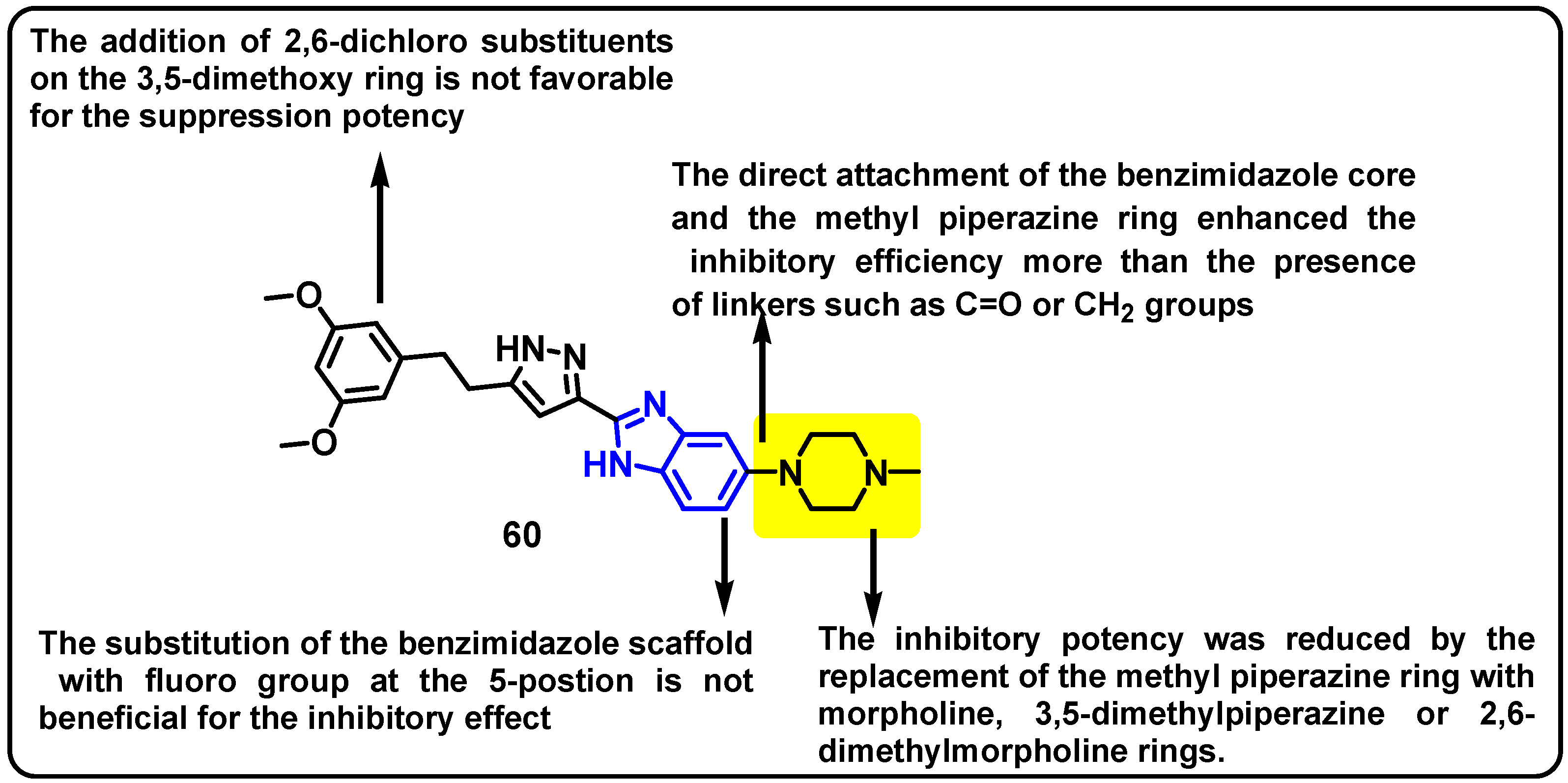

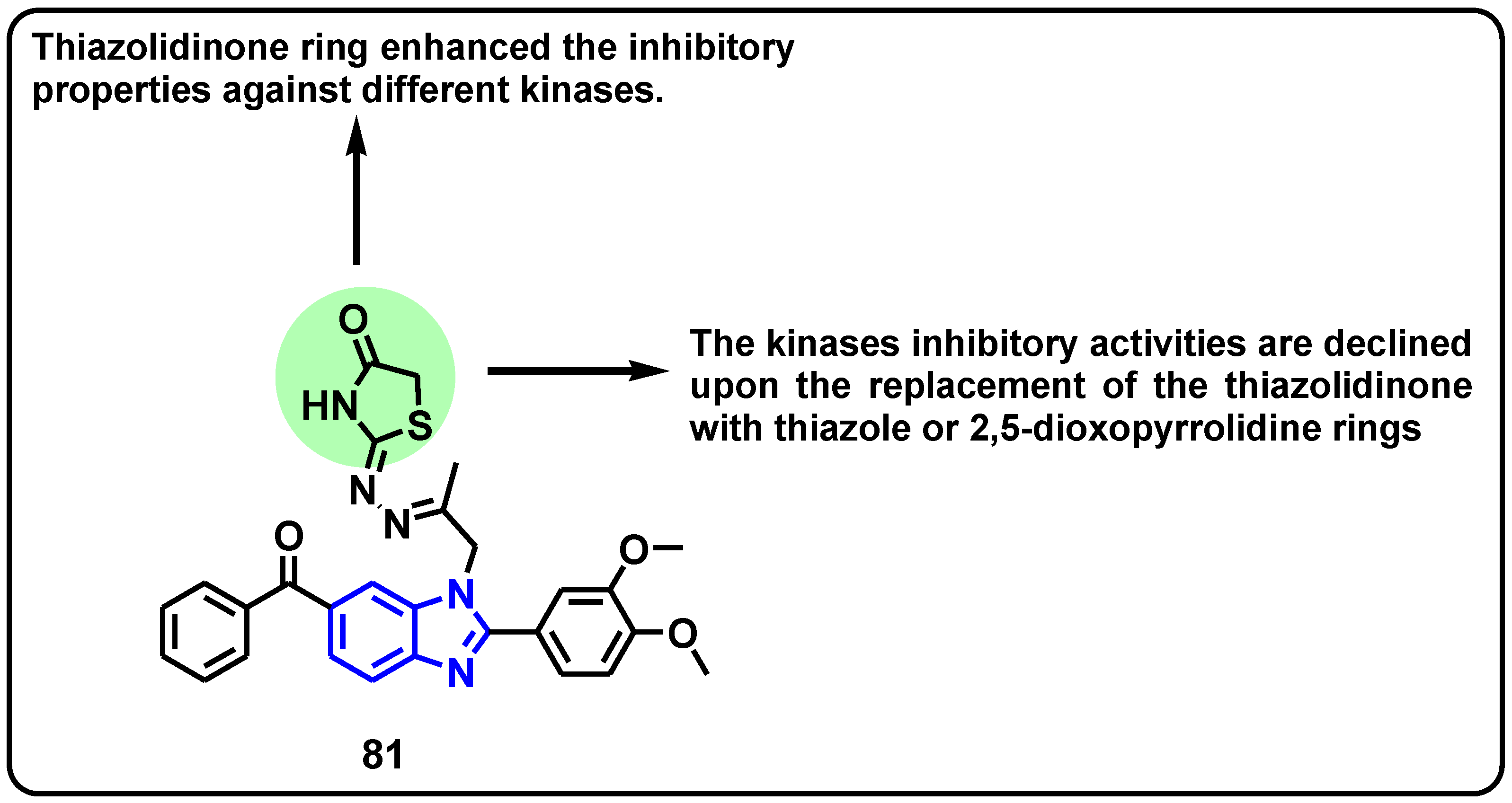

2.4.2. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as FGFR Kinase Inhibitor

2.5. FMS-like Tyrosine Kinase 3 (FLT3) Inhibitors

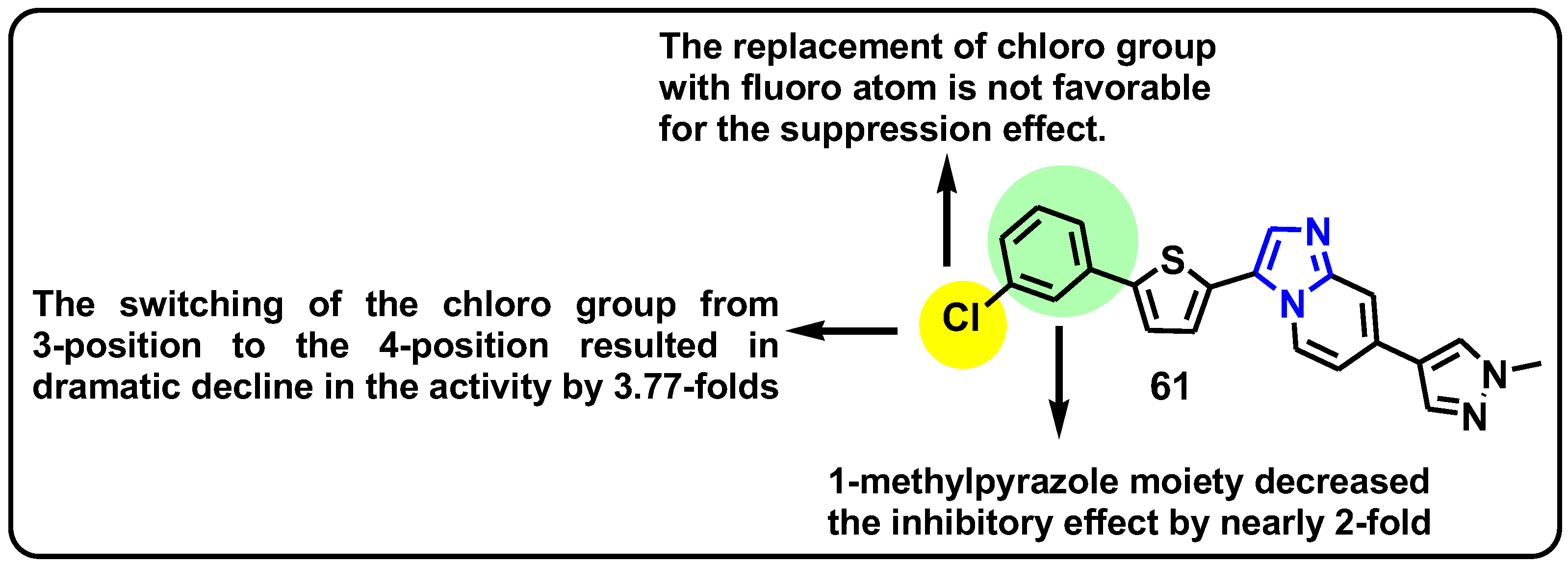

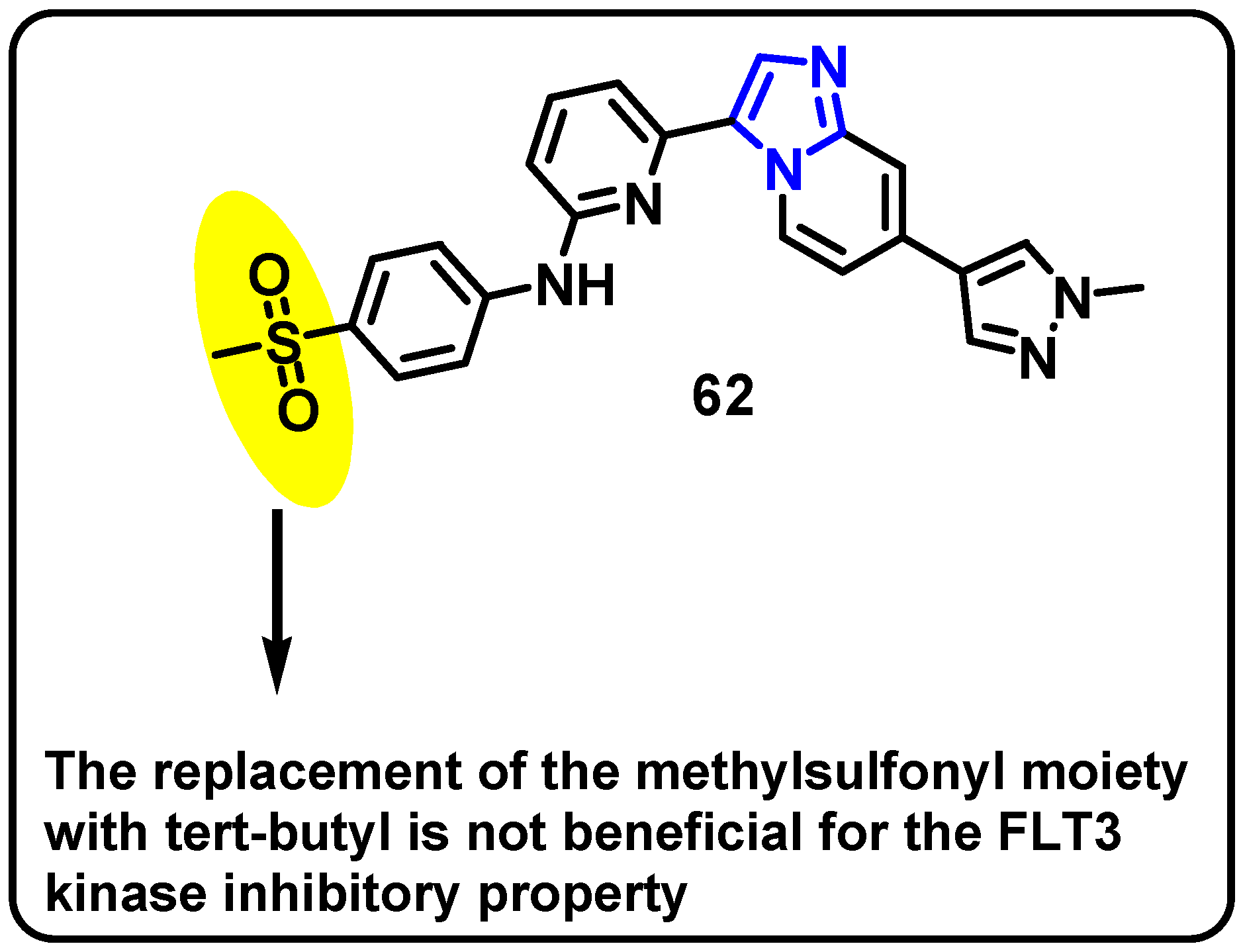

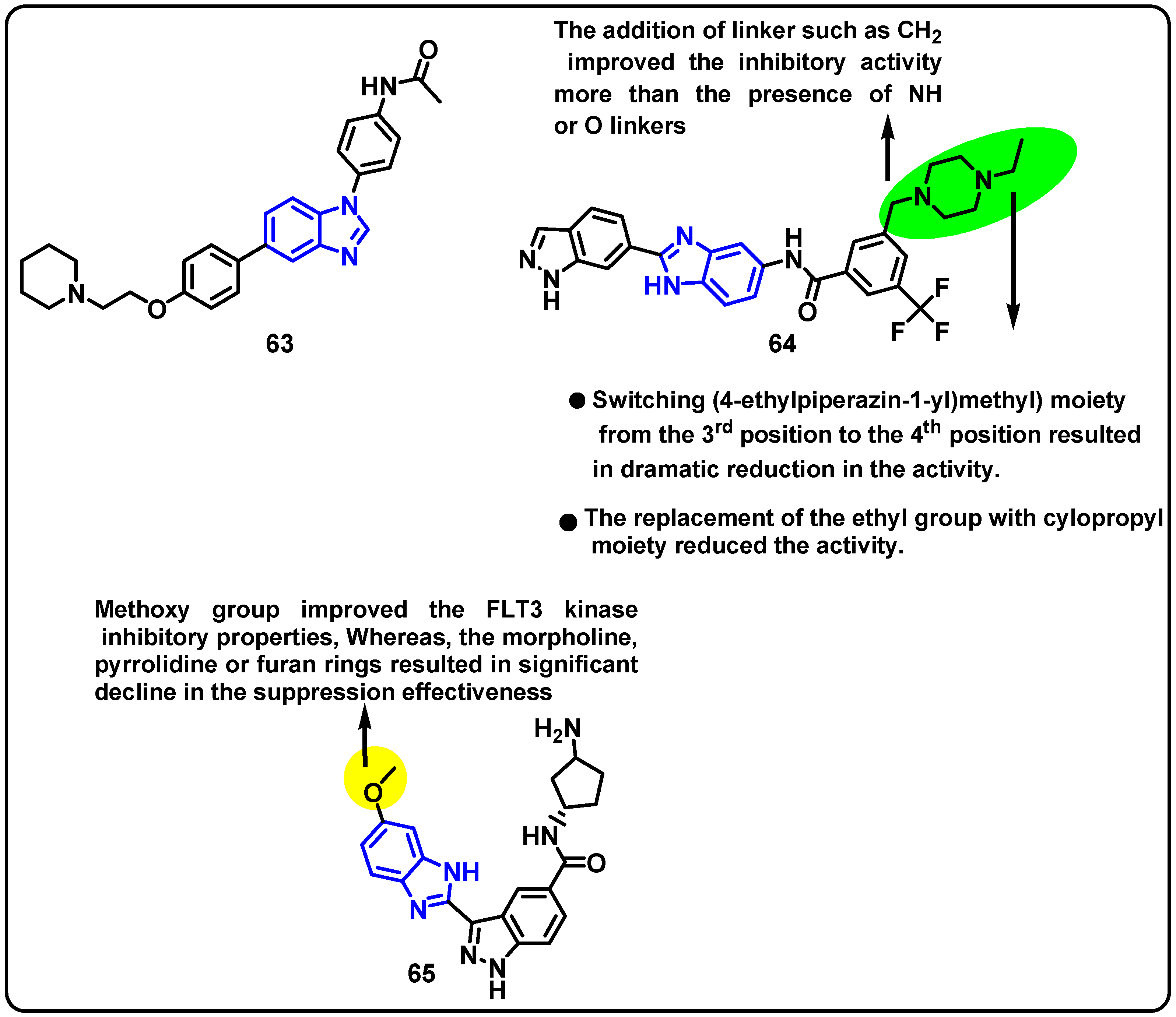

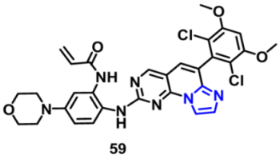

2.5.1. Imidazole-Based Derivatives as FLT3 Kinase Inhibitors

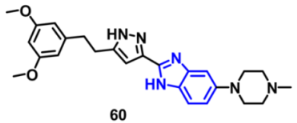

2.5.2. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as FLT3 Kinase Inhibitor

2.6. Multi-Targeting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

2.6.1. Imidazole-Based Derivatives as Multi-Targeting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

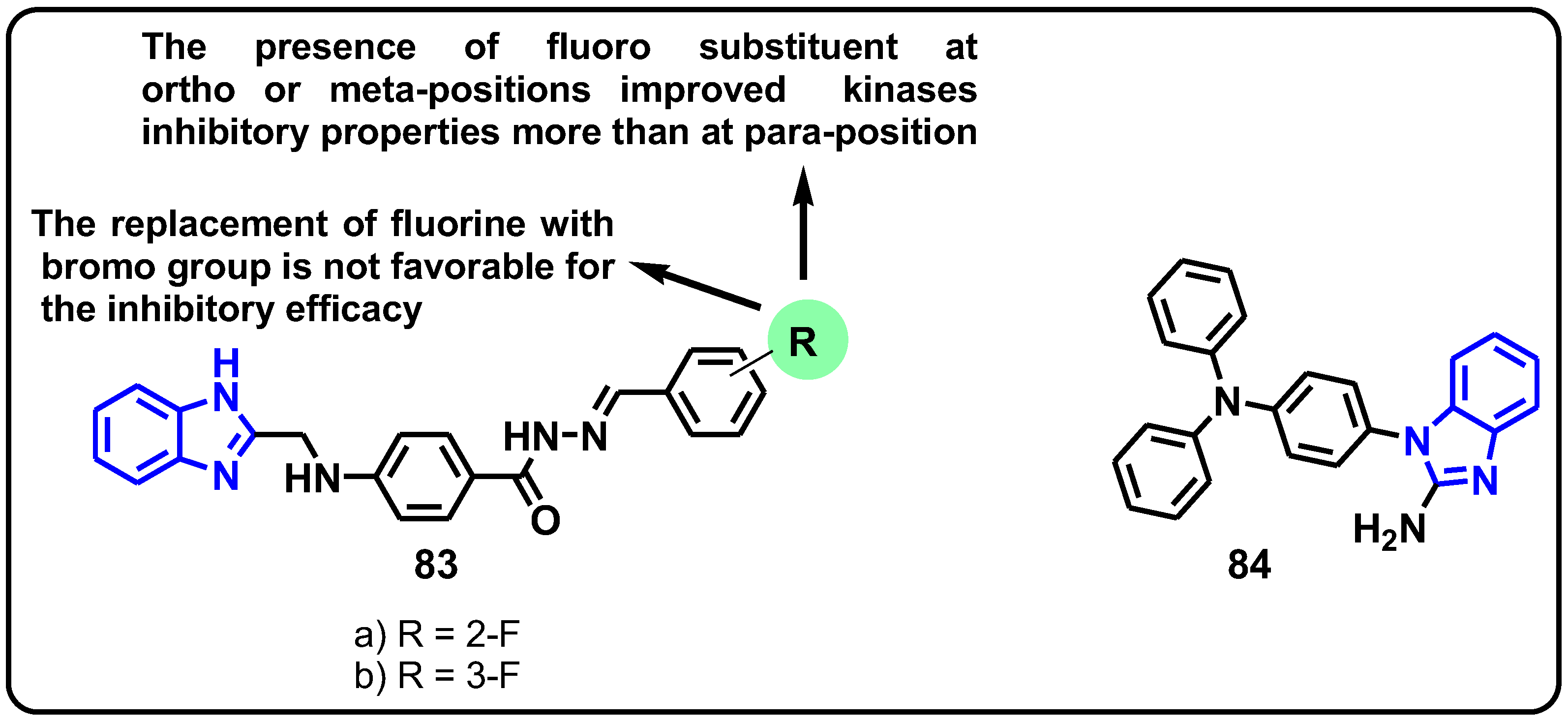

2.6.2. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as Multi-Targeting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

3. Discussion and Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piovani, D.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Bonovas, S. Non-Communicable Diseases: The Invisible Epidemic. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.M. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001, 2, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Shin, H.-R.; Bray, F.; Forman, D.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: Globocan 2008. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2893–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N.; Gold, L.S.; Willett, W.C. The causes and prevention of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 5258–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Xu, H. A systematic analysis of FDA-approved anticancer drugs. BMC Syst. Biol. 2017, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.B.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.R.; Wu, Y.-M.; Lin, S.-F. The protein tyrosine kinase family of the human genome. Oncogene 2000, 19, 5548–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S.R. Structural analysis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999, 71, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Lovly, C.M. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Lone, M.N.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Imidazoles as potential anticancer agents. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1742–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruchamy, B.; Kuruburu, M.G.; Bovilla, V.R.; Madhunapantula, S.V.; Drago, C.; Benny, S.; Presanna, A.T.; Ramani, P. Design, Synthesis, and Anti-Breast Cancer Potential of Imidazole−Pyridine Hybrid Molecules In Vitro and Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma Growth Inhibitory Activity Assessment In Vivo. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 40287–40298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plosker, G.L.; Robinson, D.M. Nilotinib. Drugs 2008, 68, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Agaram, N.P.; Wong, G.C.; Hom, G.; D’Adamo, D.; Maki, R.G.; Schwartz, G.K.; Veach, D.; Clarkson, B.D.; Singer, S.; et al. Sorafenib inhibits the imatinib-resistant KIT T670I gatekeeper mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4874–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Heimbach, T.; He, H.; Buchbinder, A.; Aghoghovbia, M.; Hourcade-Potelleret, F. Clinical Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Overview of Nilotinib, a Selective Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, N.; Naim, M.J.; Alam, J.; Nawaz, F.; Ahmed, S.; Alam, O. Benzimidazole scaffold as anticancer agent: Synthetic approaches and structure–activity relationship. Arch. Pharm. 2017, 350, e201700040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, I.; Yokoi, A.; Kohama, I.; Kumazaki, M.; Tada, Y.; Tatsumi, K.; Ochiya, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Drug library screen reveals benzimidazole derivatives as selective cytotoxic agents for KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019, 451, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, K.; Yar, M.S. Advances of benzimidazole derivatives as anti-cancer agents: Bench to bedside. In Benzimidazole; Kendrekar, P., Adimule, V., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Trudel, S.; Li, Z.H.; Wei, E.; Wiesmann, M.; Chang, H.; Chen, C.; Reece, D.; Heise, C.; Stewart, A.K. CHIR-258, a novel, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the potential treatment of t(4;14) multiple myeloma. Blood 2005, 105, 2941–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azab, A.K.; Azab, F.; Quang, P.; Maiso, P.; Sacco, A.; Ngo, H.T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Morgan, B.L.; Roccaro, A.M.; et al. FGFR3 is overexpressed wal-denstrom macroglobulinemia and its inhibition by dovitinib induces apoptosis and overcomes stro-ma-induced proliferation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 4389–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Sun, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.R.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J.S.; Park, K.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dovitinib in pretreated patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer with FGFR1 amplification: A single-arm, phase 2 study. Cancer 2016, 122, 3024–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasinoff, B.B.; Wu, X.; Nitiss, J.L.; Kanagasabai, R.; Yalowich, J.C. The anticancer multi-kinase inhibitor dovitinib also targets topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 84, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.; Chow, P.K.H.; Tai, W.M.; Choo, S.P.; Chung, A.Y.F.; Ong, H.S.; Soo, K.C.; Ong, R.; Linnartz, R.; Shi, M.M. Dovitinib demonstrates antitumor and antimetastatic activities in xenograft models of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.S.-W.; Leighl, N.B.; Riely, G.J.; Yang, J.C.-H.; Sequist, L.V.; Wolf, J.; Seto, T.; Felip, E.; Aix, S.P.; Jonnaert, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of nazartinib (EGF816) in adults with egfr-mutant non-small-cell lung carcinoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelais, G.; Epple, R.; Marsilje, T.H.; Long, Y.O.; McNeill, M.; Chen, B.; Lu, W.; Anumolu, J.; Badiger, S.; Bursulaya, B.; et al. Discovery of (R,E)-N-(7-chloro-1-(1-[4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoyl]azepan-3-yl)-1Hbenzo[d] imid-azole-2-yl)-2-methylisonicotinamide (EGF816), a novel, potent, and WT sparing covalent inhibitor of oncogenic (L858r, ex19del) and resistant (T790M) EGFR mutants for the treatment of EGFR mutant non-small-cell lung cancers. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6671–6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francini, C.M.; Musumeci, F.; Fallacara, A.L.; Botta, L.; Molinari, A.; Artusi, R.; Mennuni, L.; Angelucci, A.; Schenone, S. Optimization of Aminoimidazole Derivatives as Src Family Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2018, 23, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Song, X.; Zhao, L.M.; Piao, M.G.; Quan, J.; Piao, H.R.; Jin, C.H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novelbenzo[c][1,2,5]thiadiazol-5-yl and thieno[3,2-c]-pyridin-2-yl imidazole derivatives as ALK5 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, M.S.; Ammar, U.M.; Oh, C.-H. Anticancer profile of newly synthesized BRAF inhibitors possess 5-(pyrimidin-4-yl)imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Blewi, F.; Shaikh, S.A.; Naqvi, A.; Aljohani, F.; Aouad, M.R.; Ihmaid, S.; Rezki, N. Design and Synthesis of Novel Imidazole Derivatives Possessing Triazole Pharmacophore with Potent Anticancer Activity, and In Silico ADMET with GSK-3β Molecular Docking Investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, N.M.; Farouk, F.; George, R.F.; Abbas, S.E.; El-Badry, O.M. Design and synthesis of novel imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine based compounds as potent anticancer agents with CDK9 inhibitory activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 80, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, S.A.; Khairat, S.H.; Ali, H.I.; Shouman, S.A.; Attia, Y.M.; Ali, M.M.; Mahmoud, A.E.; Abdel-Halim, A.H.; Fyiad, A.A.; Tabll, A.; et al. Part II: New candidates of pyrazole-benzimidazole conjugates as checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, K.; Wińska, P.; Wielechowska, M.; Łukowska-Chojnacka, E.; Tölzer, C.; Niefind, K.; Bretner, M. Biological properties and structural study of new aminoalkyl derivatives of benzimidazole and benzotriazole, dual inhibitors of CK2 and PIM1 kinases. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 80, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhong, T.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Fan, Y. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation of 6-(2-amino-1Hbenzo[d]imidazole-6-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives as novel anti-cancer agents with Aurora kinase inhibition. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 190, 112108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.-S.; Sun, Y.; Gu, W. Synthesis and anticancer evaluation of novel 1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives of dehydroabietic acid as PI3Kα inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 100, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Lan, Z.; Li, W.; Han, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, P.; Zhu, W. Design, synthesis, and docking studies of quinazoline analogues bearing aryl semicarbazone scaffolds as potent EGFR inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 3148–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Xie, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Le, X.; Hong, J. Discovery of new quinazoline derivatives as irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitors and their anticancer activities—Part 1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherief, H.A.; Youssif, B.G.; Bukhari, S.N.A.; Abdelazeem, A.H.; Abdel-Aziz, M.; Abdel-Rahman, H.M. Synthesis, anticancer activity and molecular modeling studies of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives as EGFR inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 156, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarden, Y.; Pines, G. The ERBB network: At last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkman, E.-M.; Ålgars, A.; Lintunen, M.; Ristamäki, R.; Sundström, J.; Carpén, O. EGFR gene amplification is relatively common and associates with outcome in intestinal adenocarcinoma of the stomach, gastro-oesophageal junction and distal oesophagus. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.; Qi, M.; Su, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. Characterization of EGFR family gene aberrations in Cholangio-carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014, 32, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.B.; Phelps-Polirer, K.; Dingle, I.P.; Williams, C.J.; Rhett, M.J.; Eblen, S.T.; Armeson, K.; Hill, E.G.; Yeh, E.S. HUNK phosphorylates EGFR to regulate breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene 2019, 39, 1112–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujtan, L.; Subramanian, J. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2019, 19, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabe, T.; Lategahn, J.; Rauh, D. C797S resistance: The undruggable EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer? ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

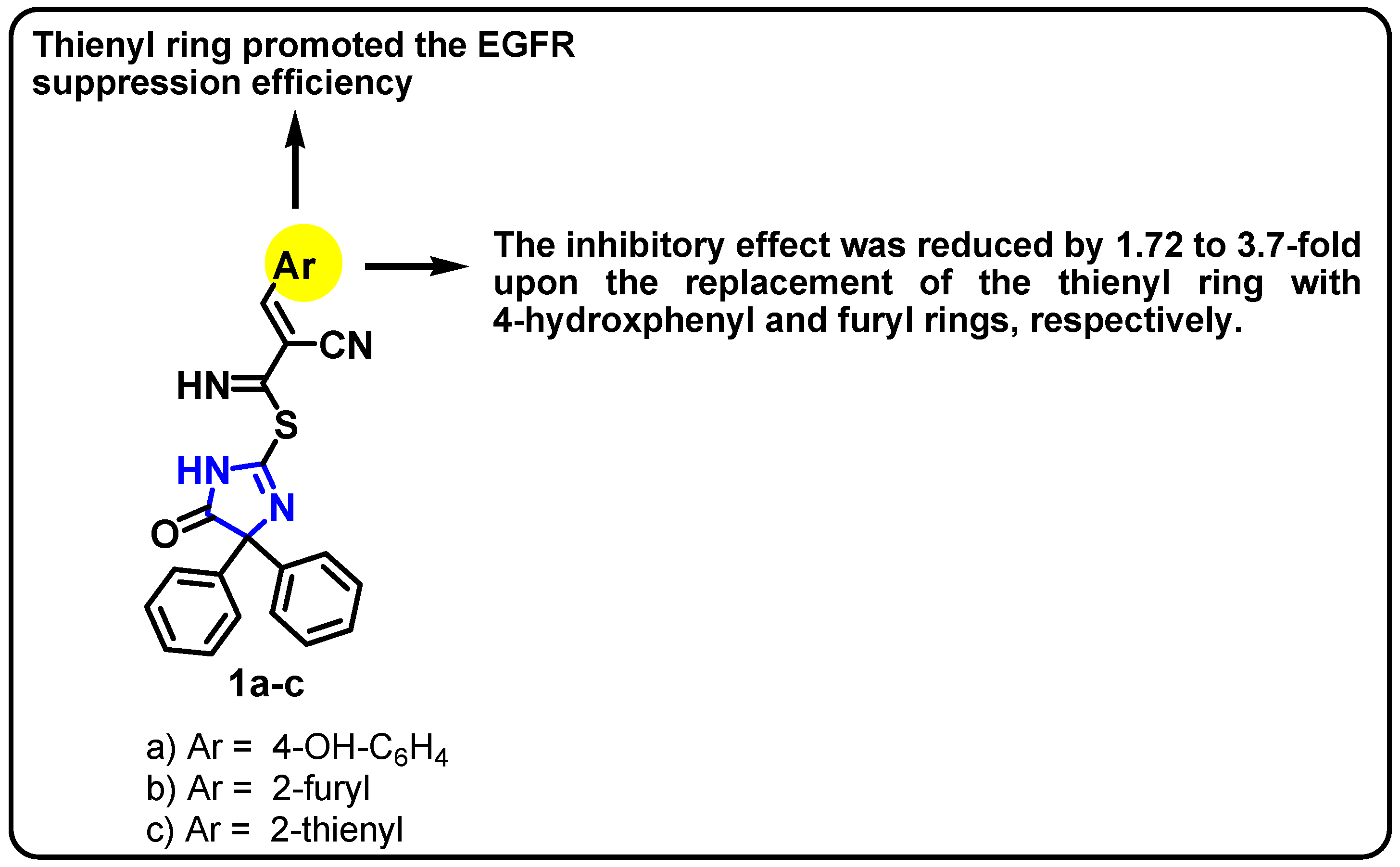

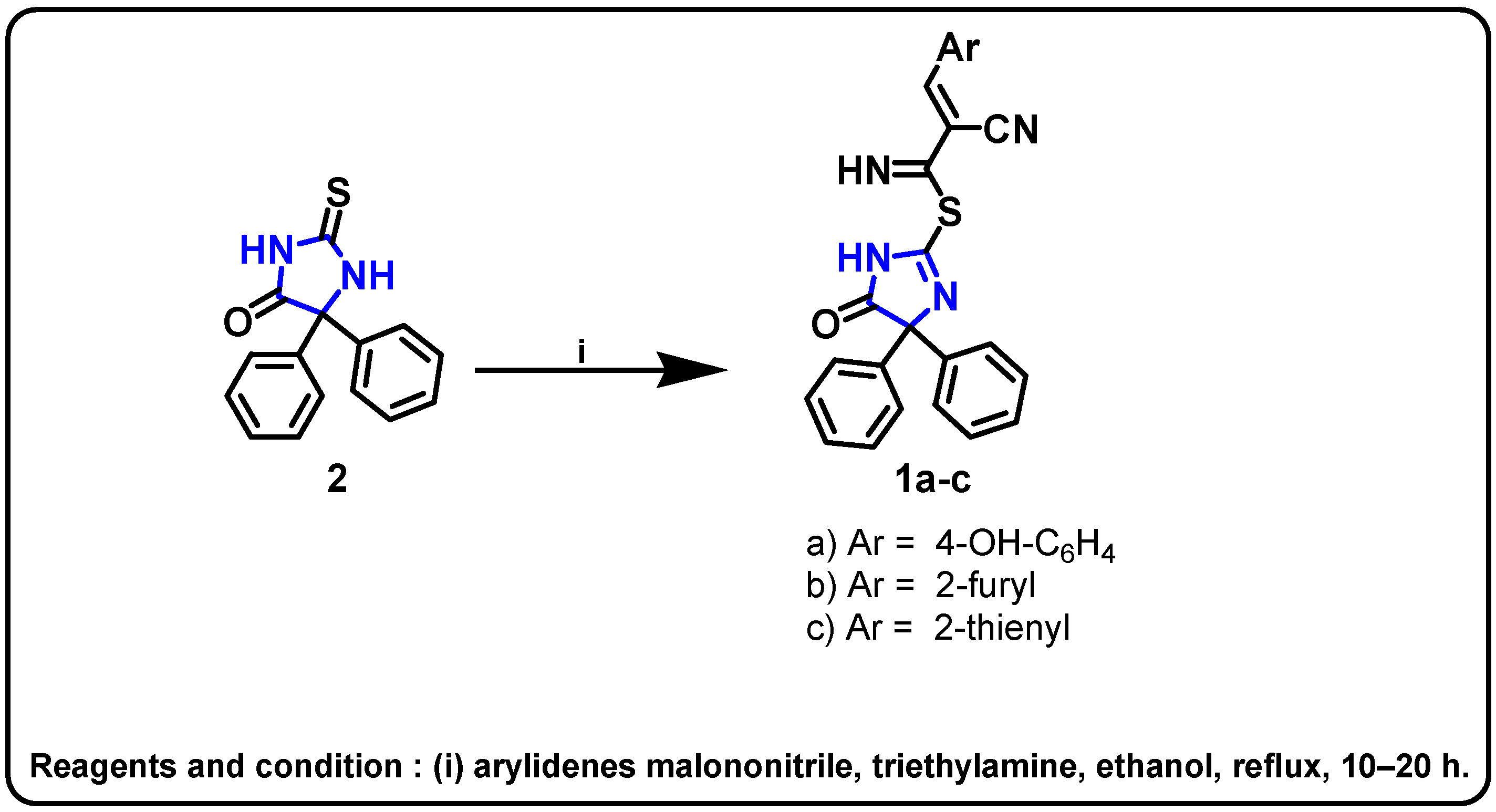

- Abdulrahman, F.G.; Abulkhair, H.S.; El Saeed, H.S.; El-Dydamony, N.M.; Husseiny, E.M. Design, synthesis, and mechanistic insight of novel imidazolones as potential EGFR inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 144, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

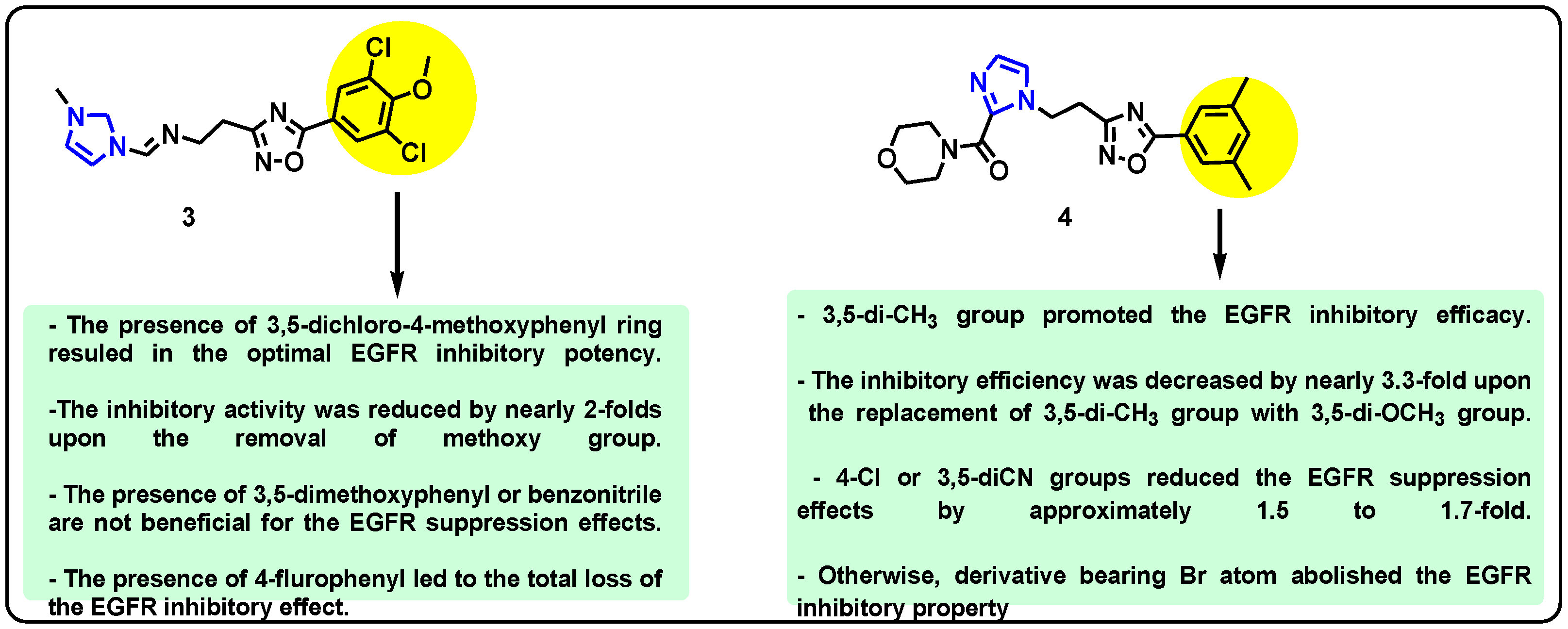

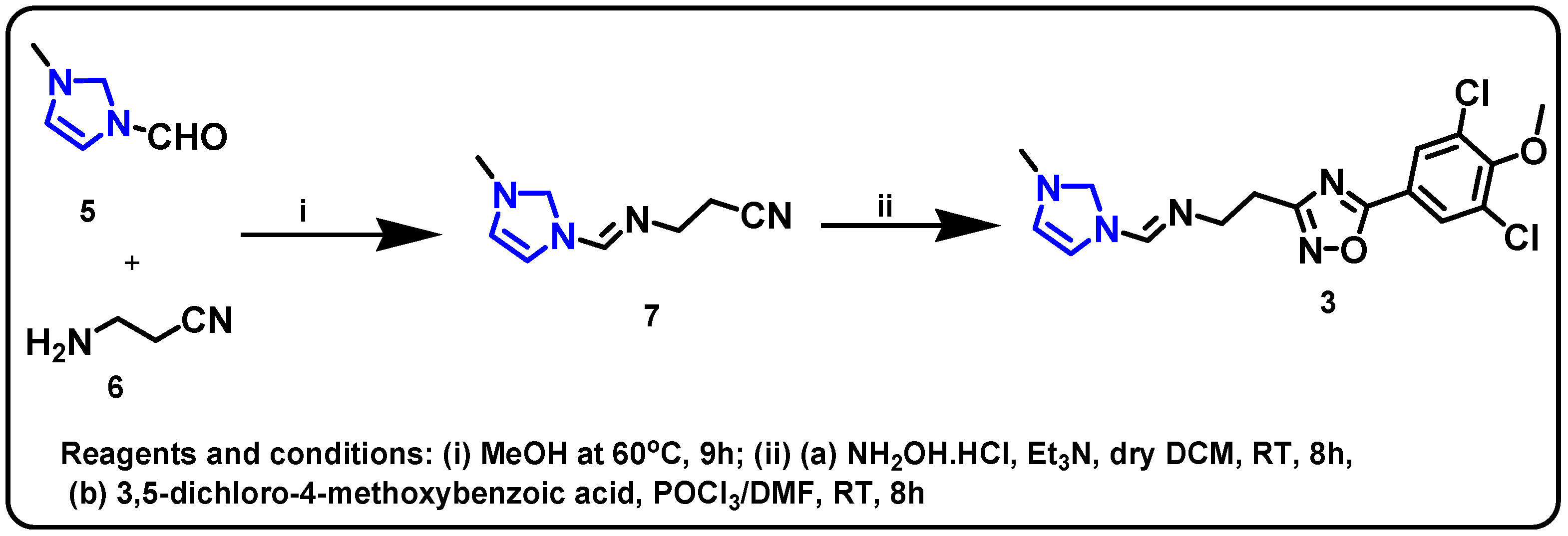

- Lavunuria, S.; Nadha, R.V.; Rapetib, S.K. Anti-Proliferative, Anti-EGFR and In Silico Studies of a Series of New Imidazole Tethered 1,2,4-Oxadiazoles. Polycycl. Aromt. Compd. 2024, 44, 4871–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannekanti, P.K.; Nukala, S.K.; Bandari, S.; Jyothi, M.; Manchal, R.; Thirukovela, N.S. Design and synthesis of some new imidazole-morpholine-1,2,4-oxadiazole hybrids as EGFR targeting in vitro anti-breast cancer agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1310, 138209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadekar, P.K.; Urunkar, G.; Roychowdhury, A.; Sharma, R.; Bose, J.; Khanna, S.; Damre, A.; Sarveswari, S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of 2,3-dihydroimidazo[2,1-b]thiazoles as dual EGFR and IGF1R inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 115, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, P.; Imtiyaz, K.; A Rizvi, M.; Nath, V.; Kumar, V.; Husain, A.; Amir, M. Design, synthesis, biological assessment and molecular modeling studies of novel imidazothiazole-thiazolidinone hybrids as potential anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

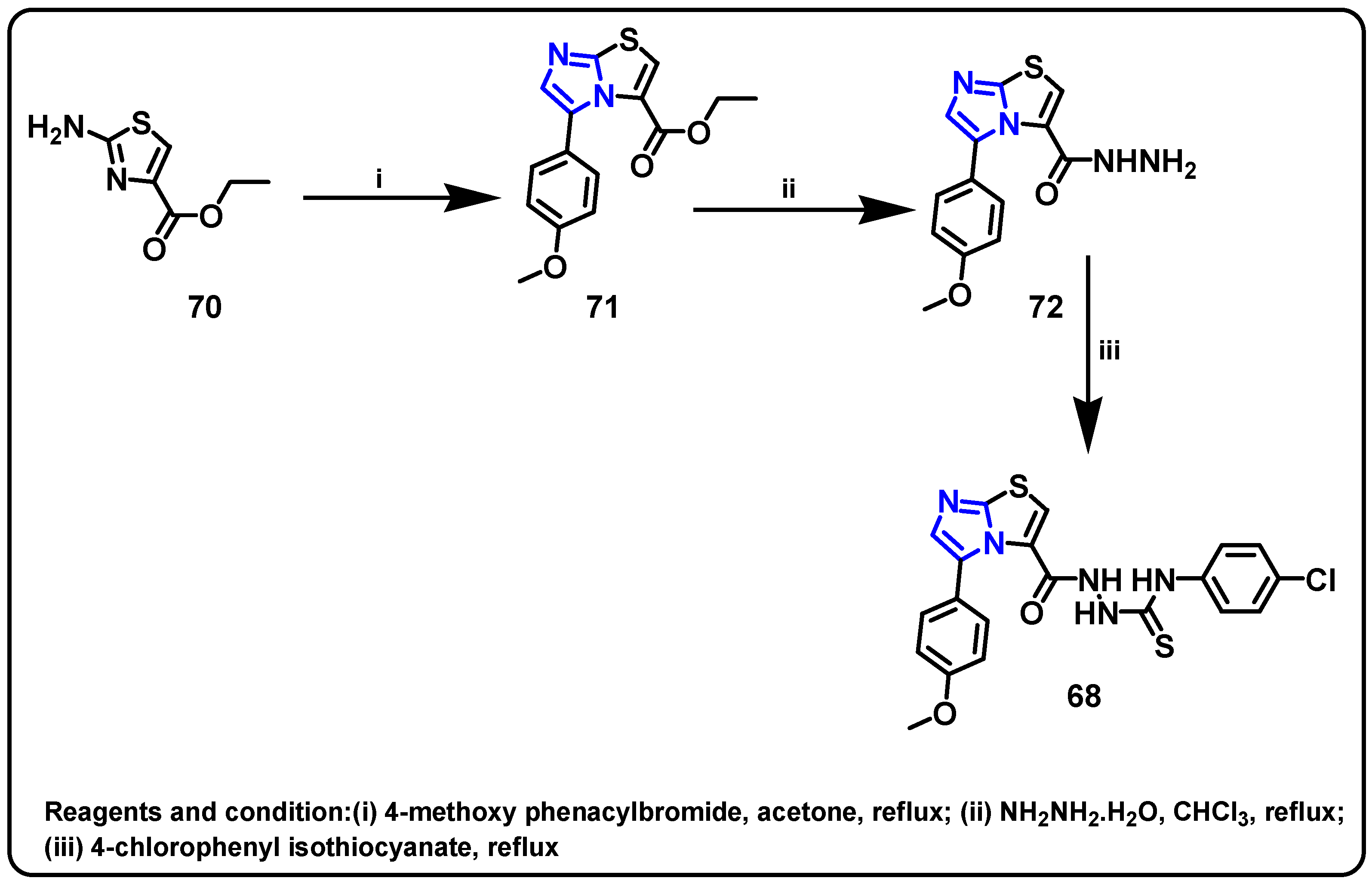

- Altıntop, M.D.; Ertorun, I.; Çiftçi, G.A.; Özdemir, A. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of a new series of imidazothiazole-hydrazone hybrids as dual EGFR and Akt inhibitors for NSCLC therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 276, 116698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.R.; Ezzat, M.A.F.; Seif, E.M.; Essa, B.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Sakr, T.M.; Ibrahim, H.S. Synthesis of S-alkylated oxadiazole bearing imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole derivatives targeting breast cancer: In vitro cytotoxic evaluation and in vivo radioactive tracing studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 153, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samala, R.; Nukala, S.K.; Manchal, R.; Nagavelli, V.R.; Narsimha, S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarine-imidazo[1,2-c][1,2,3]triazoles: PEG-400 mediated one-pot reaction under ultrasonic irradiation. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1290, 135944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnpasha, S.; Palabindela, R.; Azam, M.; Kapavarapu, R.; Nasipireddy, V.; Al-Resayes, S.I.; Narsimha, S. Synthesis and anti-breast cancer evaluation of fused imidazole-imidazo[1,2-c][1,2,3]triazoles: PEG-400 mediated one-pot reaction under ultrasonic irradiation. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1312, 138440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnpasha, S.; Azam, M.; Kapavarapu, R.; Thupurani, M.K.; Al-Resayes, S.I.; Janapatla, U.R.; Min, K.; Narsimha, S. Microwave assisted one-pot synthesis of novel 1,3,4-oxadiazole-imidazo[1′,5′:1,2]pyrrolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazoles as potent EGFR targeting anticancer agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1341, 142569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.T.; Ho, K.; Nhi, H.T.Y.; Nguyen, V.H.; Dang, T.T.; Nguyen, M.T. Imidazole[1,5-a]pyridine derivatives as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors unraveled by umbrella sampling and steered molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Joshi, G.; Kumar, M.; Arora, S.; Kaur, H.; Singh, S.; Munshi, A.; Kumar, R. Anticancer potential of some imidazole and fused imidazole derivatives: Exploring the mechanism via epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, M.M.; Eldehna, W.M.; El-Hafeez, A.A.A.; Somaa, W.R.; Albohy, A.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Agama, K.K.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Ghosh, P.; Pommier, Y.; et al. 2-Arylquinolines as novel anticancer agents with dual EGFR/FAK kinase inhibitory activity: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modelling insights. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 37, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanvand, Z.; Bakhshaiesh, T.O.; Peytam, F.; Firoozpour, L.; Hosseinzadeh, E.; Motahari, R.; Moghimi, S.; Nazeri, E.; Toolabi, M.; Momeni, F.; et al. Imidazo[1,2-a]quinazolines as novel, potent EGFR-TK inhibitors: Design, synthesis, bioactivity evaluation, and in silico studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 133, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

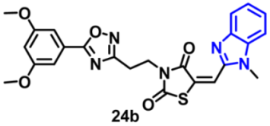

- Hagar, F.F.; Abbas, S.H.; Gomaa, H.A.M.; Youssif, B.G.M.; Sayed, A.M.; Abdelhamid, D.; Abdel-Aziz, M. Chalcone/1,3,4-Oxadiazole/Benzimidazole hybrids as novel anti-proliferative agents inducing apoptosis and inhibiting EGFR & BRAFV600E. BMC Chem. 2023, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagar, F.F.; Abbas, S.H.; Sayed, A.M.; Gomaa, H.A.; Youssif, B.G.; Abdelhamid, D.; Abdel-Aziz, M. New antiproliferative 1,3,4-oxadiazole/benzimidazole derivatives: Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation as dual EGFR and BRAFV600E inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 157, 108297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

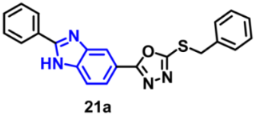

- Alzahrani, S.A.S.; Nazreen, S.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Alam, M.M. Benzimidaz-ole-1,3,4-Oxadiazole Hybrids: Synthesis, Anticancer Evaluation, Docking and DFT Studies. Chemis-trySelect 2022, 7, e202201559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagar, F.; Abbas, S.; Sayed, A.; Abdelhamid, D.; Abdel-Aziz, M. New Oxadiazole/Benzimidazole Hy-brids: Design, Synthesis, and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Adv. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 6, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Venu, K.; Saritha, B.; Sailaja, B. New molecular hybrids containing benzimidazole, thiazolidine-2,4-dione and 1,2,4-oxadiazole as EGFR directing cytotoxic agents. Tetrahedron 2022, 124, 132991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, H.A.; Alam, M.M.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Malebari, A.M.; Nazreen, S. Synthesis, antiproliferative, docking and DFT studies of benzimidazole derivatives as EGFR inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1253, 132265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.Y.; Mohammed, A.F.; Almarhoon, Z.M.; Bräse, S.; Youssif, B.G.M. Design, synthesis, and apoptotic antiproliferative action of new benzimidazole/1,2,3-triazole hybrids as EGFR inhibitors. Front. Chem. 2025, 12, 1541846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, A.M.; Ahmed, N.S.; El-Karim, S.S.A.; Anwar, M.M.; El-Hallouty, S.M. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, QSAR analysis and molecular modelling of new thiazol-benzimidazoles as EGFR inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssif, B.G.; Morcoss, M.M.; Bräse, S.; Abdel-Aziz, M.; Abdel-Rahman, H.M.; Abou El-Ella, D.A.; Abdelhafez, E.S.M. Benzimidazole-Based Derivatives as Apoptotic Antiproliferative Agents: De-sign, Synthesis, Docking, and Mechanistic Studies. Molecules 2024, 29, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.; Ayhan-Kılcıgil, G.; Karayel, A.; Guven, B.; Onay-Besikci, A. Synthesis, molecular docking, in silico ADME, and EGFR kinase inhibitor activity studies of some new benzimidazole derivatives bearing thiosemicarbazide, triazole, and thiadiazole. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2022, 59, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

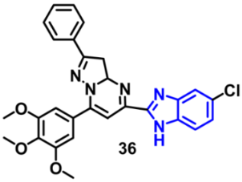

- Bagul, C.; Rao, G.K.; Veena, I.; Kulkarni, R.; Tamboli, J.R.; Akunuri, R.; Shaik, S.P.; Pal-Bhadra, M.; Kamal, A. Benzimidazole-linked pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine conjugates: Synthesis and detail evaluation as potential anticancer agents. Mol. Divers. 2023, 27, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Theodore, C.; Sivaiah, G.; Prasad, S.; Kumar, K.Y.; Raghu, M.; Alharethy, F.; Prashanth, M.; Jeon, B.-H. Design, synthesis, anticancer activity and molecular docking of novel 1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives as potential EGFR inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1294, 136341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambala, A.; Sandhya, J.; Kotilingaiah, N.; Sudha, M.; Pandiri, S.; Palabindela, R. Design, synthesis, and In silico studies of novel benzimidazole, benzoxazole, and benzothiazole analogues as EGFR-targeting anticancer agents against breast cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 786, 152723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, M. The Role of Diagnostic Roentgenology in Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1960, 262, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, N.; Sakai, N.; Hirayama, T.; Miwa, K.; Oguro, Y.; Oki, H.; Okada, K.; Takagi, T.; Iwata, H.; Awazu, Y.; et al. Discovery of N-[5-({2-[(cyclopropylcarbonyl)amino]imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-6-yl}oxy)-2-methylphenyl]-1,3-dimethyl-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxamide (TAK-593), a highly potent VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 2333–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Colbert, L.S.; Fuller, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Rev. Cancer 2010, 1806, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Cooley, H. Rates of structure development during gelation and softening of high-methoxyl pectin—Sodium alginate—Fructose mixtures. Top. Catal. 1995, 9, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, W.; Serve, H.; Do, H.; Schwittay, M.; Ottmann, O.G.; O’Farrell, A.-M.; Bello, C.L.; Allred, R.; Manning, W.C.; Cherrington, J.M. A phase 1 study of SU11248 in the treatment of patients with re-fractory or resistant acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or not amenable to conventional therapy for the disease. Blood 2005, 105, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.; Yassa, L.; Marqusee, E.; George, S.; Frates, M.C.; Chen, M.H.; Morgan, J.A.; Dychter, S.S.; Larsen, P.R.; Demetri, G.D.; et al. Hypothyroidism after sunitinib treatment for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.F.; A Rupnick, M.; Kerkela, R.; Dallabrida, S.M.; Zurakowski, D.; Nguyen, L.; Woulfe, K.; Pravda, E.; Cassiola, F.; Desai, J.; et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet 2007, 370, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Mahmoud, W.R.; Refaey, R.H.; George, R.F.; Georgey, H.H. Insight on Some Newly Synthesized Trisubstituted Imidazolinones as VEGFR-2 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkotamy, M.S.; Elgohary, M.K.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Almahli, H.; Eldehna, W.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A. Novel imidazo[2,1-b]thiazoles and imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines tethered with indolinone motif as VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptotic inducers: Design, synthesis and biological evaluations. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 151, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgohary, M.K.; Elkotamy, M.S.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Binjubair, F.A.; Alarifi, R.S.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Eldehna, W.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A. Exploring antitumor activity of novel imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole and im-idazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives on MDA-MB-231 cell line: Targeting VEGFR-2 enzyme with com-putational insight. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1322, 140579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wei, Y.; Kowah, J.A.H.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors based on the mo-lecular structures of imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole and matrine: Design, synthesis, in vitro evaluation of an-titumor activity and molecular docking. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1323, 140747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Lateef, H.M.A.; Elbastawesy, M.A.I.; Ibrahim, T.M.A.; Khalaf, M.M.; Gouda, M.; Wahba, M.G.F.; Zaki, I.; Morcoss, M.M. Design, Synthesis, Docking Study, and Antiproliferative Evaluation of Novel Schiff Base–Benzimidazole Hybrids with VEGFR-2 Inhibitory Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

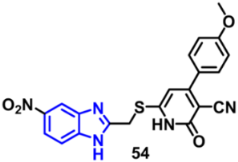

- Abdel-Mohsen, H.T.; El Kerdawy, A.M. Design, Synthesis, Molecular Docking Studies and in Silico Prediction of ADME Properties of New 5-Nitrobenzimidazole/thiopyrimidine Hybrids as Anti-angiogenic Agents Targeting Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Egypt. J. Chem. 2024, 67, 437–446. [Google Scholar]

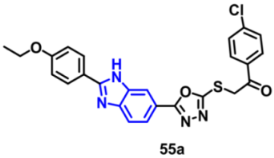

- Çevik, U.A.; Celik, I.; Görgülü, Ş.; Inan, Z.D.Ş.; Bostancı, H.E.; Özkay, Y.; Kaplacıklı, Z.A. New benzimidazole-oxadiazole derivatives as potent VEGFR-2 inhibitors: Synthesis, anticancer evaluation, and docking study. Drug Dev. Res. 2024, 85, e22218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, X.; Lv, Y.; Yu, R.; Kang, C. Design, synthesis, and antitumor activity of novel benzoheterocycle derivatives as inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase. J. Chem. Res. 2020, 44, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-J.; Chen, H.-K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lien, J.-C.; Gao, J.-Y.; Huang, Y.-H.; Hsu, J.B.-K.; Lee, G.A.; Huang, S.-W. Anti-Angiogenetic and Anti-Lymphangiogenic Effects of a Novel 2-Aminobenzimidazole Derivative, MFB. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 862326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaro, D.P.; Rubin, J.S.; Faletto, D.L.; Chan, A.M.L.; Kmiecik, T.E.; Vande Woude, G.F.; Aaronson, S.A. Identification of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor as the c-met proto-oncogene product. Science 1991, 251, 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchmeier, C.; Birchmeier, W.; Gherardi, E.; Woude, G.F.V.; Woude, V. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 4, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, S.; Carbognin, L.; Karachaliou, N.; Ma, P.; Rosell, R.; Tortora, G.; Bria, E. Tracking MET de-addiction in lung cancer: A road towards the oncogenic target. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Ma, Y.; Liang, X.; Xie, G.; Luo, Y.; Zha, D.; Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, W.; et al. Design, synthesis and antitumor evaluation of novel 5-methylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine derivatives as potential c-Met inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 104, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-W.; Ye, Z.-D.; Shi, L. c-Met kinase inhibitors: An update patent review (2014–2017). Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2019, 29, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.I.; Hu, S.; Chen, T.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lu, T. Discovery, optimization and biological evaluation for novel c-Met kinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Li, H.-J.; Fang, S.-B.; Li, Q.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C. Structure-based discovery of novel 4-(2-fluorophenoxy)quinoline derivatives as c-Met inhibitors using isocyanide-involved multicomponent reactions. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 193, 112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 6,11-dihydro-5 H-benzo[e]pyrimido-[5,4-b][1,4]diazepine derivatives as potential c-Met inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 140, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, M.H.; Liu, L.; Lee, M.; Xi, N.; Fellows, I.; D’angelo, N.D.; Dominguez, C.; Rex, K.; Bellon, S.F.; Kim, T.-S.; et al. Structure-based design of novel class II c-Met inhibitors: 1. Identification of pyrazolone-based derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Wu, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, H.; Du, S.; Wei, H.; Hou, Y.; et al. Novel 4-phenoxypyridine derivatives bearing imidazole-4-carboxamide and 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide moieties: Design, synthesis and biological evaluation as potent antitumor agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 120, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, A.N.; Kilgour, E.; Smith, P.D. Molecular pathways: Fibroblast growth factor signaling: A new therapeutic opportunity in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, C.; Heymach, J.; Overman, M.; Tran, H.; Kopetz, S. Beyond VEGF: Inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor pathway and antiangiogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6130–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ibrahimi, O.A.; Olsen, S.K.; Umemori, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Ornitz, D.M. Receptor speci-ficity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 15694–15700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Grose, R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: From development to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, V.; Cook, S.J. De-regulated FGF receptors as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 125, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, M.; Nakagama, H. FGF Receptors: Cancer Biology and Therapeutics. Med. Res. Rev. 2014, 34, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinola, M.; Leoni, V.P.; Tanuma, J.-I.; Pettinicchio, A.; Frattini, M.; Signoroni, S.; Agresti, R.; Giovanazzi, R.; Pilotti, S.; Bertario, L.; et al. FGFR4 Gly388Arg polymorphism and prognosis of breast and colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2005, 14, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Lopes de Menezes, D.; Vora, J.; Harris, A.; Ye, H.; Nordahl, L.; Garrett, E.; Samara, E.; Aukerman, S.L.; Gelb, A.B.; et al. In vivo target growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor, in colon cancer models. Clin. Canc. Res. 2005, 11, 3633–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollin, L.; Wex, E.; Pautsch, A.; Schnapp, G.; Hostettler, K.E.; Stowasser, S.; Kolb, M. Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, A.S.; Miao, J.; Wistuba, I.I.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Heymach, J.V.; Fossella, F.V.; Lu, C.; Velasco, M.R.; Box-Noriga, B.; Hueftle, J.G.; et al. Phase II trial of Cediranib in combination with cisplatin and pemetrexed in chemotherapy-N€aıve patients with unre-sectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (SWOG S0905). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2537–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M. FGFR inhibitors: Effects on cancer cells, tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, R.; Borea, R.; Coelho, A.; Khan, S.; Araújo, A.; Reclusa, P.; Franchina, T.; Van Der Steen, N.; Van Dam, P.; Ferri, J.; et al. FGFR a promising druggable target in cancer: Molecular biology and new drugs. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 113, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancker, O.V.; Wehland, M.; Bauer, J.; Infanger, M.; Grimm, D. The adverse effect of hypertension in the treatment of thyroid cancer with multi-kinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 3, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isamu, M.; Miyazai, M.-T.; Masaaki, T.; Koichi, A.; Hidetoshi, H.-K.; Hiroyasu, K.; Takayasu, K.; Junji, T.; Takashi, S.; Fumihiko, H.; et al. Tlerability of nintedanib (BIBF 1120) in combination with docetaxel: Aphase 1 study in japanase patients with pre-viously treated non- small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 346–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin, B.-K.; Jason, C.; Douglas, R.; Humphrey, G.; Michael, M.-S.; Jhon, M.-K. Phase I/II and phar-macodynamic study of Dovitinib (TKI258), an inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptors and VEGF receptors, in patients with advanced melanoma. Clin. Canc. Res. 2011, 17, 7451–7461. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, H.; Lee, L.Y.; Goh, K.Y.; Ong, R.; Hao, H.; Huang, A.; Wang, Y.; Porta, D.G.; Chow, P.; Chung, A. Infigratinib mediates vascular normalization, impairs metastasis, and improves chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2019, 69, 943–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, T.P.; Jovcheva, E.; Mevellec, L.; Vialard, J.; De Lange, D.; Verhulst, T.; Paulussen, C.; Van De Ven, K.; King, P.; Freyne, E.; et al. Discovery and pharmacological characterization of JNJ-42756493 (erdafitinib), a functionally selective small-molecule FGFR family inhibitor. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Park, S.H.; Garcia-Donas, J.; Huddart, R.; Burgess, E.; Fleming, M.; Rezazadeh, A.; Mellado, B.; Varlamov, S.; et al. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstmann, R.; Rodon, J.; Prat, A.; Perez-Garcia, J.; Adamo, B.; Felip, E.; Cortes, J.; Iafrate, A.J.; Nuciforo, P.; Tabernero, J. Genomic aberrations in the FGFR pathway: Opportunities for targeted therapies in solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touat, M.; Ileana, E.; Postel-Vinay, S.; André, F.; Soria, J.-C. Targeting FGFR signaling in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2684–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, J.C.; Kim, W.J.; Byun, J.; Gil Ahn, Y.; Park, H.-J. Structure–activity relationship studies of Imidazo[1′,2′:1,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives to develop selective FGFR inhibitors as anticancer agents for FGF19-overexpressed hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 282, 117047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamani, A.; Zdżalik-Bielecka, D.; Lipner, J.; Stańczak, A.; Piórkowska, N.; Stańczak, P.S.; Olejkowska, P.; Hucz-Kalitowska, J.; Magdycz, M.; Dzwonek, K.; et al. Discovery and optimization of novel pyrazole-benzimidazole CPL304110, as a potent and selective inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptors FGFR (1–3). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, D.G.; Griffin, J.D. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood 2002, 100, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshinchi, S.; Appelbaum, F.R. Structural and functional alterations of FLT3 in acute myeloid leu-kemia. Clin. Canc. Res. 2009, 15, 4263–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.; Black, J.; Faerman, C.; Swenson, L.; Wynn, M.; Lu, F.; Lippke, J.; Saxena, K. The structural basis for autoinhibition of FLT3 by the juxta-membrane domain. Mol. Cell 2004, 13, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa-Garcia, M.; Baer, M.R. FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: Current status and future directions. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.C.; Wang, Q.; Chin, C.-S.; Salerno, S.; Damon, L.E.; Levis, M.J.; Perl, A.E.; Travers, K.J.; Wang, S.; Hunt, J.P.; et al. Validation of ITD mutations in FLT3 as a therapeutic target in human acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2012, 485, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, N.J.; Konopleva, M.; Kadia, T.M.; Borthakur, G.; Ravandi, F.; DiNardo, C.D.; Daver, N. Advances in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: New drugs and new challenges. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versele, M.; Haefner, B.; Wroblowski, B.; Stansfield, I.; Mevellec, L.; Gilissen, R.; Neumann, L.; Augustin, M.; Jacobs, K.; Cools, J.; et al. Abstract 4800: Covalent FLT3-cys828 inhibition represents a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of FLT3-ITD and FLT3-D835 mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J.; Geney, R.; Menet, C. Type II kinase inhibitors: An opportunity in cancer for rational design. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Kaneko, N.; Ueno, Y.; Yamada, M.; Tanaka, R.; Saito, R.; Shimada, I.; Mori, K.; Kuromitsu, S. Gilteritinib, a FLT3/AXL inhibitor, shows antileukemic activity in mouse models of FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Investig. New Drugs 2017, 35, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, M.; Aly, M.M.; Khan, A.M.; Al Share, B.; Dhillon, V.; Lalo, E.; Ramos, H.; Akers, K.G.; Kim, S.; Balasubramanian, S. Efficacy analysis of different FLT3 inhibitors in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. eJHaem 2022, 4, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

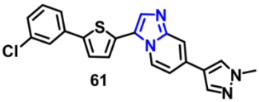

- Zhang, L.; Lakkaniga, N.R.; Bharate, J.B.; Mcconnell, N.; Wang, X.; Kharbanda, A.; Leung, Y.-K.; Frett, B.; Shah, N.P.; Li, H.-Y. Discovery of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-thiophene derivatives as FLT3 and FLT3 mutants inhibitors for acute myeloid leukemia through structure-based optimization of an NEK2 inhibitor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 225, 113776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

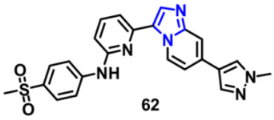

- Wang, X.; DeFilippis, R.A.; Weldemichael, T.; Gunaganti, N.; Tran, P.; Leung, Y.-K.; Shah, N.P.; Li, H.-Y. An imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-pyridine derivative potently inhibits FLT3-ITD and FLT3-ITD secondary mutants, including gilteritinib-resistant FLT3-ITD/F691L. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokla, E.M.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Milik, S.N.; McPhillie, M.J.; Minucci, S.; Abouzid, K.A. Discovery of a benzimidazole-based dual FLT3/TrKA inhibitor targeting acute myeloid leukemia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 56, 116596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, D.; Jun, J.; Baek, J.; Kim, H.; Kang, D.; Bae, H.; Cho, H.; Hah, J.-M. Rational design and synthesis of 2-(1 H -indazol-6-yl)-1 H -benzo[d]imidazole derivatives as inhibitors targeting FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and its mutants. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, B.; Jang, Y.; Kim, M.H.; Lam, T.T.; Seo, H.K.; Jeong, P.; Choi, M.; Kang, K.W.; Lee, S.-D.; Park, J.-H.; et al. Discovery of benzimidazole-indazole derivatives as potent FLT3-tyrosine kinase domain mutant kinase inhibitors for acute myeloid leukemia. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 262, 115860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabry, M.A.; Ghaly, M.A.; Maarouf, A.R.; El-Subbagh, H.I. New thiazole-based derivatives as EGFR/HER2 and DHFR inhibitors: Synthesis, molecular modeling simulations and anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 241, 114661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moharram, E.A.; El-Sayed, S.M.; Ghabbour, H.A.; El-Subbagh, H.I. Synthesis, molecular modeling simulations and anticancer activity of some new Imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole analogues as EGFR/HER2 and DHFR inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 150, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

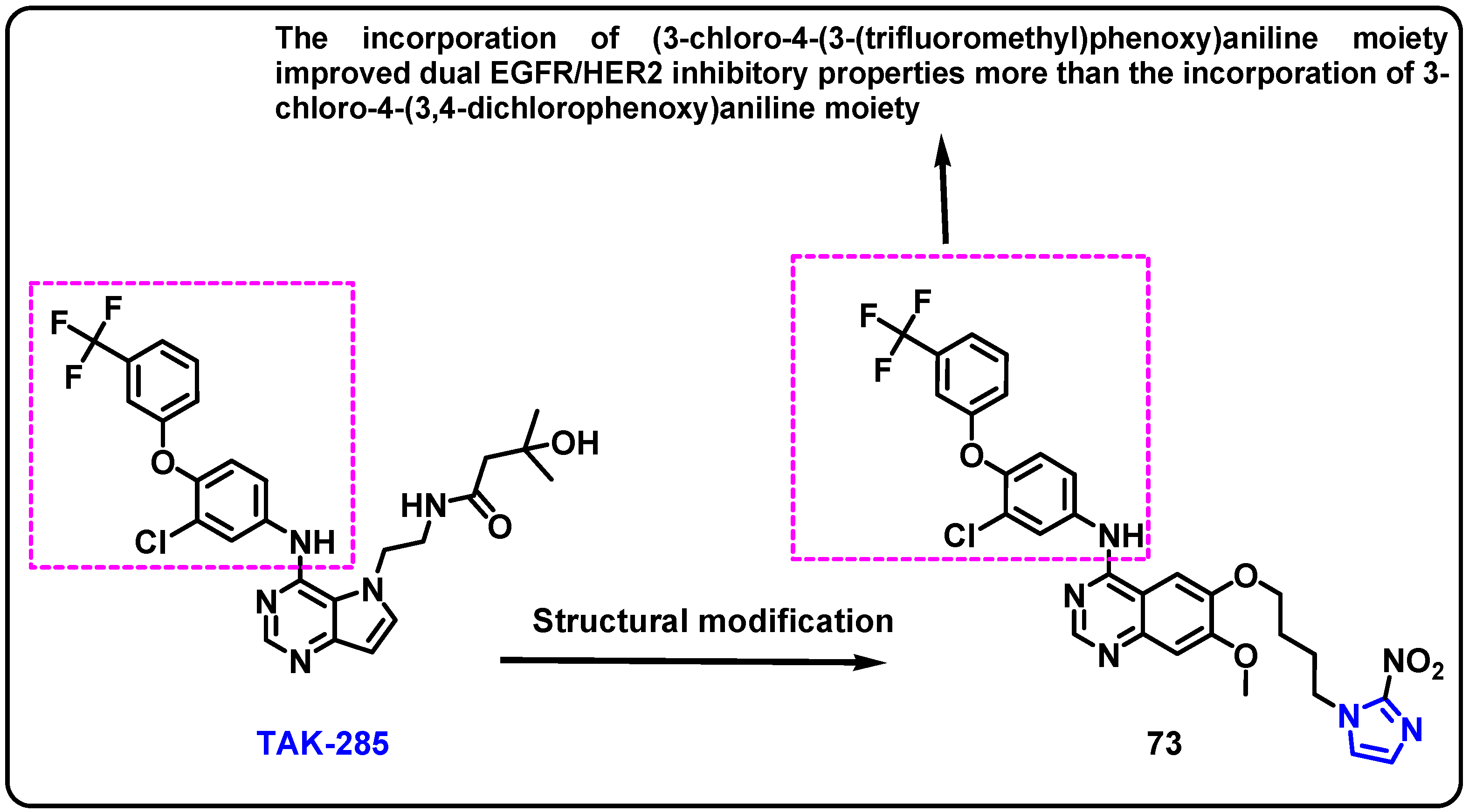

- Son, S.; Elkamhawy, A.; Gul, A.R.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Alnajjar, R.; Abdeen, A.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Alshammari, S.O.; Alshammari, Q.A.; Choi, W.J.; et al. Development of new TAK-285 derivatives as potent EGFR/HER2 inhibitors possessing antiproliferative effects against 22RV1 and PC3 prostate carcinoma cell lines. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 2202358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

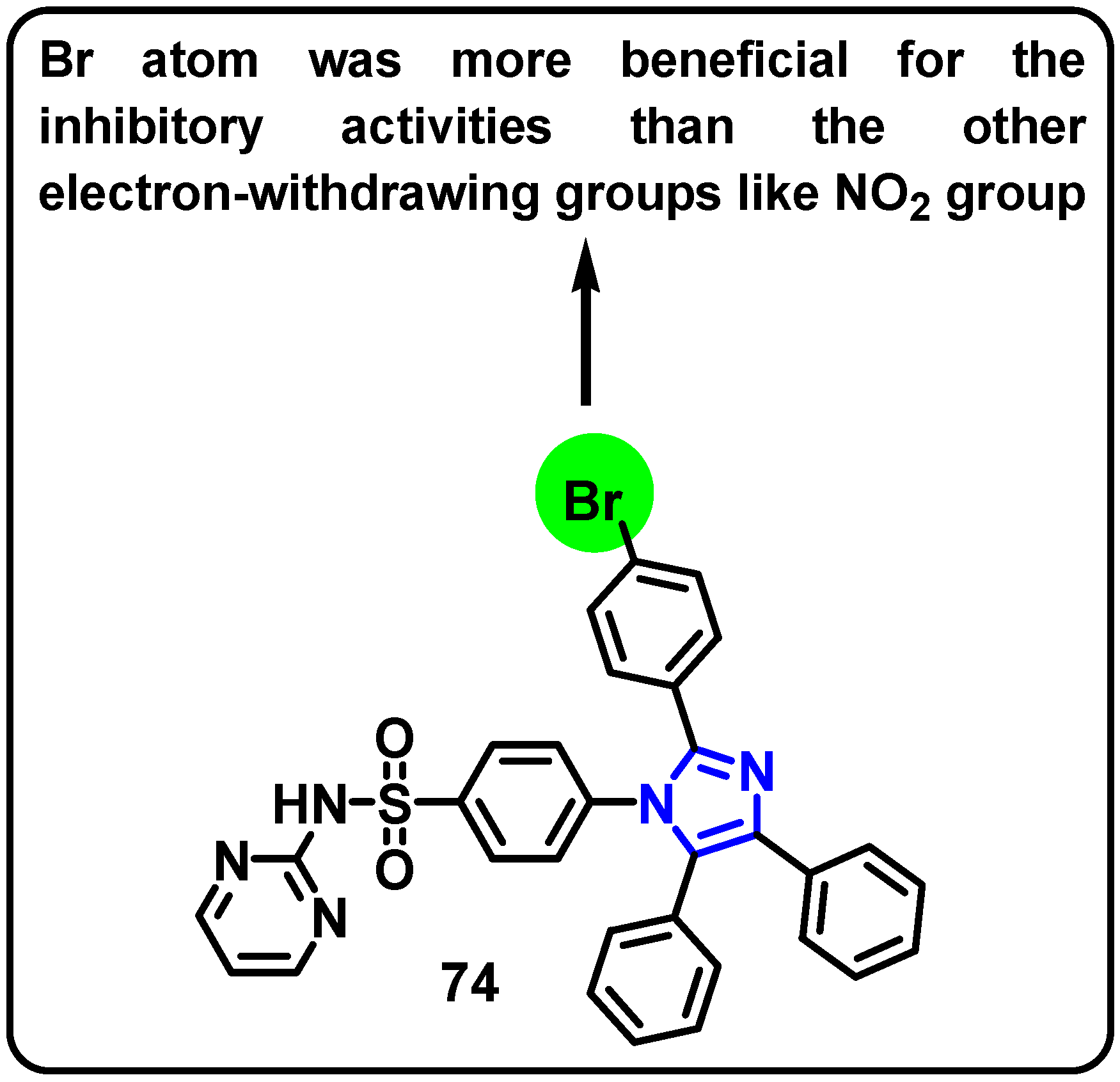

- Alghamdi, E.M.; Alamshany, Z.M.; El Hamd, M.A.; Taher, E.S.; El-Behairy, M.F.; Norcott, P.L.; Marzouk, A.A. Anticancer Activities of Tetrasubstituted Imidazole-Pyrimidine-Sulfonamide Hybrids as Inhibitors of EGFR Mutants. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202200641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

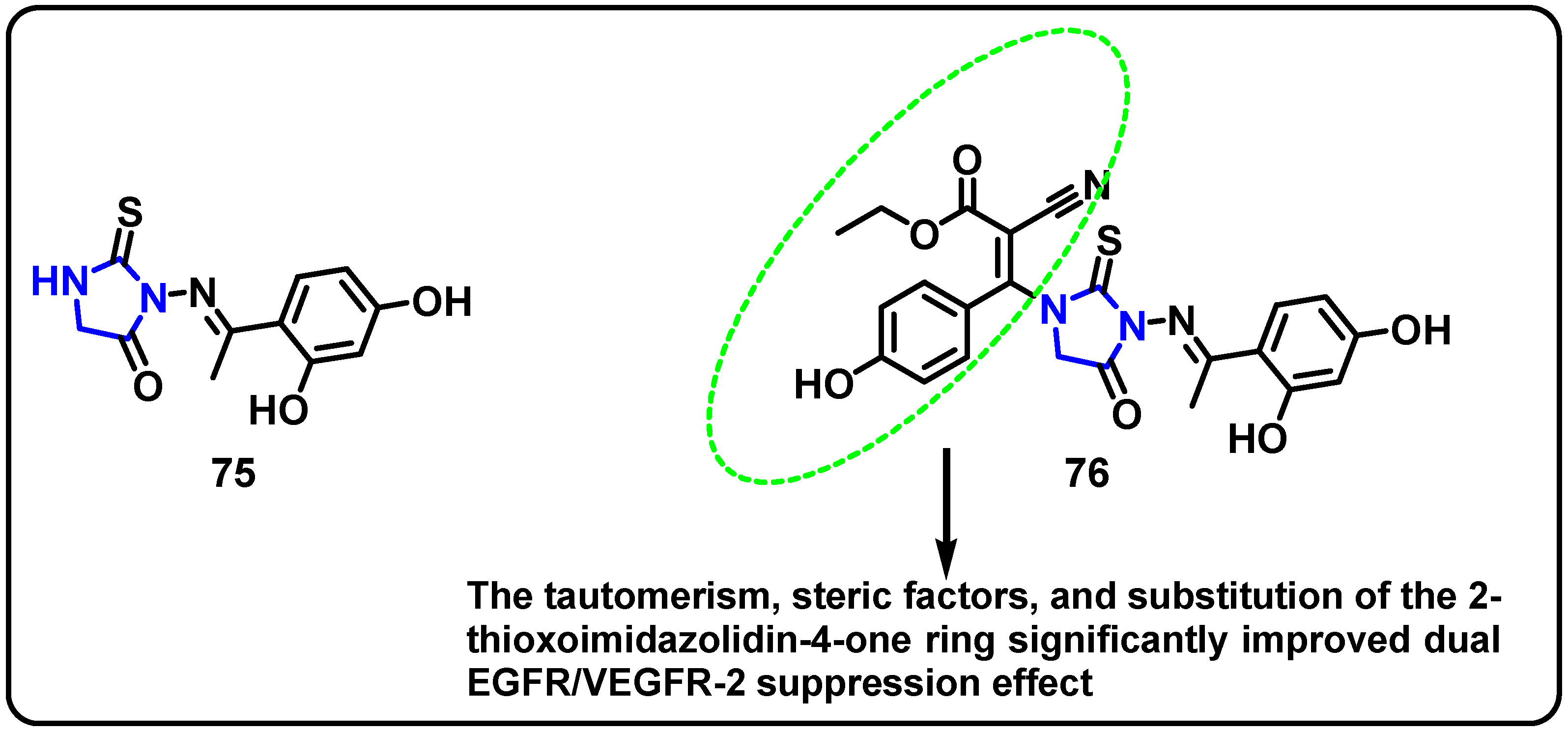

- Mourad, A.A.; Farouk, N.; El-Sayed, E.-S.H.; Mahdy, A.R. EGFR/VEGFR-2 dual inhibitor and apoptotic inducer: Design, synthesis, anticancer activity and docking study of new 2-thioxoimidazolidin-4one derivatives. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

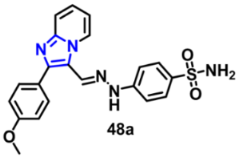

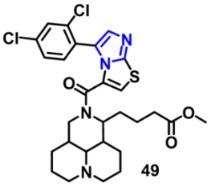

- Damghani, T.; Moosavi, F.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Mortazavi, M.; Pirhadi, S.; Kayani, Z.; Saso, L.; Edraki, N.; Firuzi, O. Imidazopyridine hydrazone derivatives exert antiproliferative effect on lung and pancreatic cancer cells and potentially inhibit receptor tyrosine kinases including c-Met. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Meguid, E.A.A.; El-Deen, E.M.M.; Nael, M.A.; Anwar, M.M. Novel benzimidazole derivatives as anti-cervical cancer agents of potential multi-targeting kinase inhibitory activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 9179–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirgany, T.O.; Rahman, A.M.; Alanazi, M.M. Design, synthesis, and mechanistic evaluation of novel benzimidazole-hydrazone compounds as dual inhibitors of EGFR and HER2: Promising candidates for anticancer therapy. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1309, 138177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirgany, T.O.; Asiri, H.H.; Rahman, A.F.M.M.; Alanazi, M.M. Discovery of 1H-benzo[d]imidazole-(halogenated) Benzylidenebenzohydrazide Hybrids as Potential Multi-Kinase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulkumar, M.; Yang, K.; Wang, N.; Penislusshiyan, S.; Palvannan, T.; Ramalingam, K.; Chen, F.; Luo, S.-H.; Zhou, Y.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y. Synthesis of benzimidazole/triphenylamine-based compounds, evaluation of their bioactivities and an in silico study with receptor tyrosine kinases. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

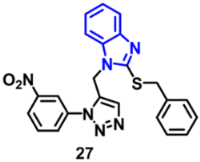

- Othman, D.I.A.; Hamdi, A.; Tawfik, S.S.; Elgazar, A.A.; Mostafa, A.S. Identification of new benzimidazole-triazole hybrids as anticancer agents: Multi-target recognition, in vitro and in silico studies. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 2166037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allam, R.M.; El Kerdawy, A.M.; Gouda, A.E.; Ahmed, K.A.; Abdel-Mohsen, H.T. Benzimidaz-ole-oxindole hybrids as multi-kinase inhibitors targeting melanoma. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 146, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Mohsen, H.T.; Nageeb, A.M. Benzimidazole–dioxoisoindoline conjugates as dual VEGFR-2 and FGFR-1 inhibitors: Design, synthesis, biological investigation, molecular docking studies and ADME predictions. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 28889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Mohsen, H.T.; Abdullaziz, M.A.; El Kerdawy, A.M.; Ragab, F.A.F.; Flanagan, K.J.; Mahmoud, A.E.E.; Ali, M.M.; El Diwani, H.I.; Senge, M.O. Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinase VEGFR-2 in Hepatocellular Cancer: Rational Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 1,2-Disubstituted Benzimidazoles. Molecules 2020, 25, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.H.; Abdel-Mohsen, H.T.; Mounier, M.M.; Abo-Elfadl, M.T.; El Kerdawy, A.M.; Ghannam, I.A. Design, synthesis and anticancer activity of novel 2-arylbenzimidazole/2-thiopyrimidines and 2-thioquinazolin-4(3H)-ones conjugates as targeted RAF and VEGFR-2 kinases inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 126, 105883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

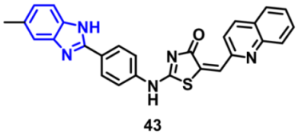

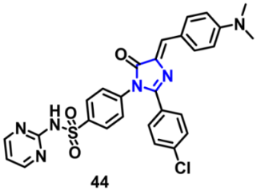

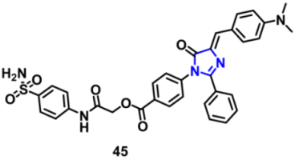

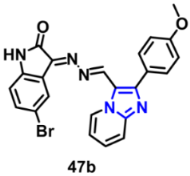

| Structure | Target Kinase | IC50 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 0.137 µM | [45] |

| EGFR | 0.47 μM | [47] |

| EGFR | 9.11 µM | [50] |

| EGFR | 0.367 µM | [52] |

| EGFR | 33.65 nM | [57] |

| EGFR | 61 nM | [60] |

| EGFR | 0.23 µM | [63] |

| EGFR | 73 nM | [65] |

| EGFR | 71.67 nM | [66] |

| EGFR | 0.09 µM | [67] |

| EGFR | 0.29 µM | [69] |

| EGFR | 0.47 μM | [71] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.07 µM | [79] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.02 µM | [79] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.22 µM | [80] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.28 µM | [80] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.576 µM | [81] |

| VEGFR-2 | 3.09 μM | [82] |

| VEGFR-2 | 2.83 μM | [84] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.475 μM | [85] |

| VEGFR-2 | 0.618 µM | [85] |

| c-Met | 0.012 μM | [97] |

| FGFR1, 2, and 4 | 8, 4, and 3.8 nM, respectively | [118] |

| FGFR (1-3) | 0.75, 0.50, and 3.05 nM, respectively | [119] |

| FLT3 | 0.053 µM | [130] |

| FLT3 | 7.94 nM | [131] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Hussain, S.A.; Dawood, D.H.; Farghaly, T.A.; Abu Alnjaa, A.M.; Zaki, M.E.A. Insight into the Anticancer Potential of Imidazole-Based Derivatives Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121839

Al-Hussain SA, Dawood DH, Farghaly TA, Abu Alnjaa AM, Zaki MEA. Insight into the Anticancer Potential of Imidazole-Based Derivatives Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121839

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Hussain, Sami A., Dina H. Dawood, Thoraya A. Farghaly, Alaa M. Abu Alnjaa, and Magdi E. A. Zaki. 2025. "Insight into the Anticancer Potential of Imidazole-Based Derivatives Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121839

APA StyleAl-Hussain, S. A., Dawood, D. H., Farghaly, T. A., Abu Alnjaa, A. M., & Zaki, M. E. A. (2025). Insight into the Anticancer Potential of Imidazole-Based Derivatives Targeting Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121839