Biological Activities of Novel Kombuchas Based on Alternative Ingredients to Replace Tea Leaves

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Alternative Substrates to Replace Tea in Innovative Kombucha Beverages

2.2. Physicochemical and Biochemical Characteristics of Alternative Kombucha Beverages

2.3. Biological Activities of Alternative Kombucha Beverages

2.3.1. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.2. Immune-Modulatory Activity

2.3.3. Antiproliferative/Antitumoral Activity

2.3.4. Hypoglycemic Activity

2.3.5. Antihypertensive and Hypolipidemic/Hypocholesterolemic Activity

2.3.6. Antimicrobial Activity

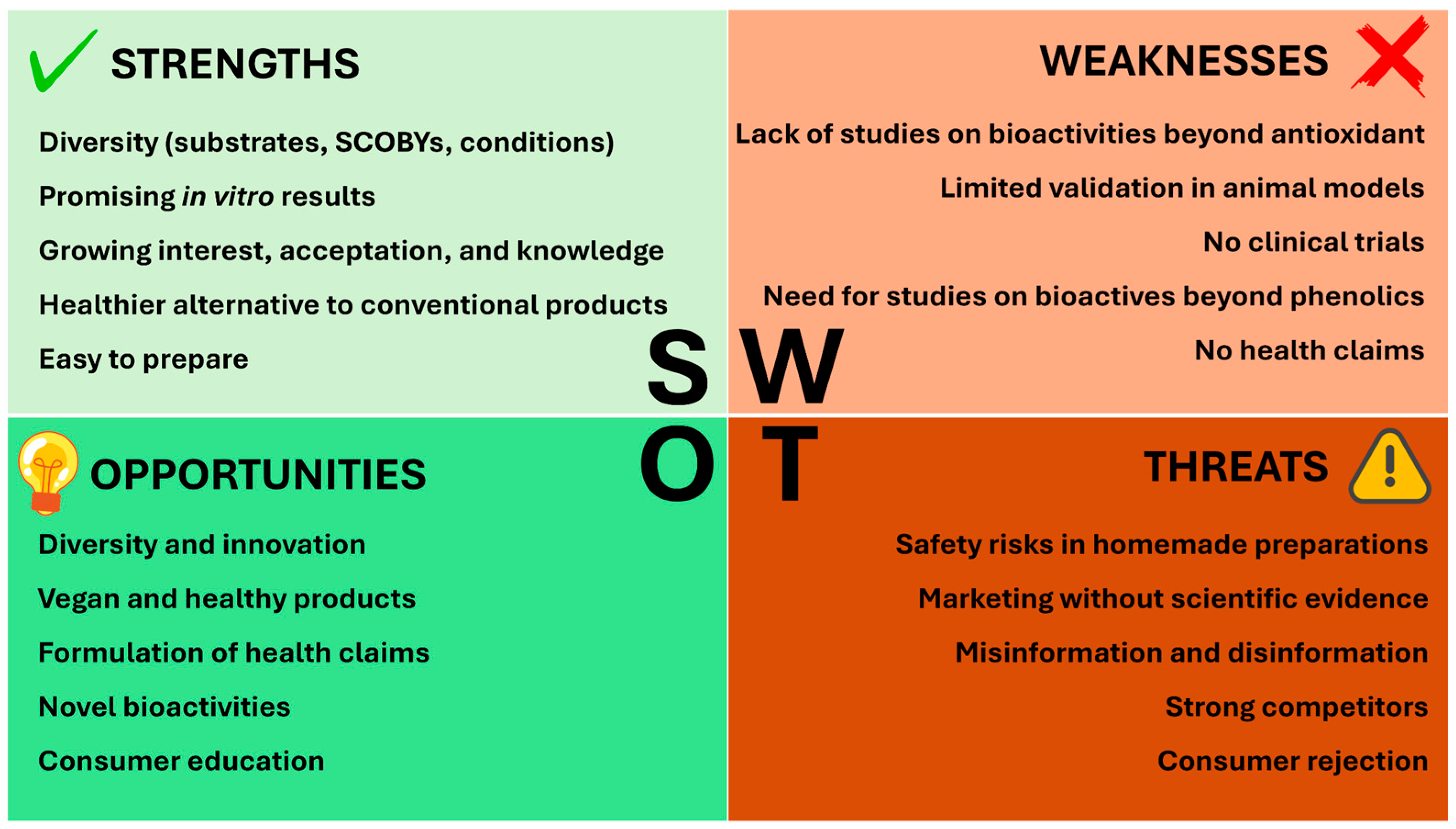

2.4. Current Status of Alternative Kombucha Beverages Assessed Through a SWOT Analysis

2.4.1. Strengths

2.4.2. Weaknesses

2.4.3. Opportunities

2.4.4. Threats

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. SWOT Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCOBY | Symbiotic consortium/culture of bacteria and yeasts |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

| AAB | Acetic acid bacteria |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| DSL | D-saccharide-1,4-lactone |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- de las Nieves Siles-Sánchez, M.; Tejedor-Calvo, E.; Jaime, L.; Santoyo, S.; Morales, D. Green Extraction Technologies and Kombucha Elaboration Using Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo) Fruits to Obtain Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Fractions. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 18, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Júnior, J.C.; Meireles Mafaldo, Í.; de Lima Brito, I.; Tribuzy de Magalhães Cordeiro, A.M. Kombucha: Formulation, Chemical Composition, and Therapeutic Potentialities. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewkod, T.; Bovonsombut, S.; Tragoolpua, Y. Efficacy of Kombucha Obtained from Green, Oolongand Black Teas on Inhibition of Pathogenic Bacteria, Antioxidation, and Toxicity on Colorectal Cancer Cell Line. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.; Zhang, X.X.; Mutukumira, A.N. Kombucha: Production and Microbiological Research. Foods 2022, 11, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, R.; Malbaša, R.V.; Lončar, E.S.; Vitas, J.S.; Sathishkumar, M. A Review on Kombucha Tea-Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Astiazaran, O.J. Recent Advances in Kombucha Tea: Microbial Consortium, Chemical Parameters, Health Implications and Biocellulose Production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 377, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.M.D.; de Almeida, A.L.; do Amaral, R.Q.G.; da Mota, R.N.; de Sousa, P.H.M. Kombucha: Review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, J.F.; Ruiz, L.F.; Silva, C.B.; Uekane, T.M.; Silva, K.A.; Gonzalez, A.G.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha: A Review of Substrates, Regulations, Composition, and Biological Properties. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Pitts, E.R.; Budner, D.; Thompson-Witrick, K.A. Kombucha: Biochemical and Microbiological Impacts on the Chemical and Flavor Profile. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 10025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, J.; De Vuyst, L. Acetic Acid Bacteria in Fermented Foods and Beverages. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D. Biological Activities of Kombucha Beverages: The Need of Clinical Evidence. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiz, G.M.; Bonifácio, D.B.; de Paulo, R.S.; Teixeira, C.M.; Martino, H.S.D.; de Barros, F.A.R.; Milagro, F.I.; Bressan, J. Benefits of Kombucha Consumption: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials Focused on Microbiota and Metabolic Health. Fermentation 2025, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.; Sousa, P.; Wurlitzer, N. Alternative Raw Materials in Kombucha Production. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, S.; He, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, P. Comprehensive Evaluation of Quality and Bioactivity of Kombucha from Six Major Tea Types in China. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.; Gutiérrez-Pensado, R.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B. Novel Kombucha Beverages with Antioxidant Activity Based on Fruits as Alternative Substrates. LWT 2023, 189, 115482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitas, J.S.; Cvetanović, A.D.; Mašković, P.Z.; Švarc-Gajić, J.V.; Malbaša, R.V. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Novel Types of Kombucha Beverages with Yarrow. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.G.; Zhou, D.D.; Cheng, J.; Wu, S.X.; Saimaiti, A.; Huang, S.Y.; Liu, Q.; Shang, A.; Li, H.B.; Li, S. Preparation and Evaluation of Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Kombucha Beverage Based on Antioxidant Capacities, Phenolic Compounds and Sensory Qualities. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 35, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicanski, A.S.; Cvetkovic, D.D.; Markov, S.L.; Saponjac, V.T.T.; Vulic, J.J. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of the Beverage by Fermentation of Sweetened Lemon Balm (Melissa Offi Cinalis L.) Tea with Symbiotic Consortium of Bacteria and Yeasts. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 52, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazi, M.I.; Liaqat, F.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, D. Fermentation, Functional Analysis, and Biological Activities of Turmeric Kombucha. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitas, J.; Vukmanović, S.; Čakarević, J.; Popović, L.; Malbaša, R. Kombucha Fermentation of Six Medicinal Herbs: Chemical Profile and Biological Activity. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2020, 26, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıkmış, S.; Tuğgüm, S. Evaluation of Microbiological, Physicochemical and Sensorial Properties of Purple Basil Kombucha Beverage. Turk. J. Agric.—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 7, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Flores, S.; Pereira, T.S.S.; Ramírez-Rodrigues, M.M. Optimization of Hempseed-Added Kombucha for Increasing the Antioxidant Capacity, Protein Concentration, and Total Phenolic Content. Beverages 2023, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cabral, B.D.; Larrosa-Pérez, M.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E. Oak Kombucha Protects against Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Processes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 272, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Alcantar-Orozco, E.J.; Monserrat-Juarez, V.H.; Ramírez-España, J.C.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E. In Vitro and in Vivo Assessment of Anti-Hyperglycemic and Antioxidant Effects of Oak Leaves (Quercus convallata and Quercus arizonica) Infusions and Fermented Beverages. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Beaufort, S.; Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Taillandier, P.; Bouajila, J.; Debouba, M. Kombucha Fermentation of African Mustard (Brassica tournefortii) Leaves: Chemical Composition and Bioactivity. Food Biosci. 2019, 30, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, P.; Felisiak, K.; Adamska, I. The Potential of Dried Ginkgo Biloba Leaves as a Novel Ingredient in Fermented Beverages of Enhanced Flavour and Antioxidant Properties. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 141018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuningtyas, S.; Alfarabi, M.; Lestari, Y.; Noviardi, H. The In Vitro and In Silico Study of α-Glucosidase Inhibition by Kombucha Derived from Syzygium polyanthum (Wight) Walp. Leaves. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2024, 31, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor-Calvo, E.; Morales, D. Chemical and Aromatic Changes during Fermentation of Kombucha Beverages Produced Using Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo) Fruits. Fermentation 2023, 9, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifudin, S.A.; Ho, W.Y.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdullah, R.; Koh, S.P. Fermentation and Characterisation of Potential Kombucha Cultures on Papaya-Based Substrates. LWT 2021, 151, 121060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, L.; Ben Abid, S.; Hamdi, M. Development of a Beverage from Red Grape Juice Fermented with the Kombucha Consortium. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidah, E.; Yurista, S.; Rahmadani, N.R. Characteristic of Physical, Chemical, and Microbiological Kombucha from Various Varieties of Apples. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Paris, France, 7–9 February 2018; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 131. [Google Scholar]

- Tomar, O. Determination of Some Quality Properties and Antimicrobial Activities of Kombucha Tea Prepared with Different Berries. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2023, 47, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klawpiyapamornkun, T.; Uttarotai, T.; Wangkarn, S.; Sirisa-ard, P.; Kiatkarun, S.; Tragoolpua, Y.; Bovonsombut, S. Enhancing the Chemical Composition of Kombucha Fermentation by Adding Indian Gooseberry as a Substrate. Fermentation 2023, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidah, E.; Dewantari, F.J.; Novitasari, F.R.; Srianta, I.; Blanc, P.J. Potential of Snake Fruit (Salacca zalacca (Gaerth.) Voss) for the Development of a Beverage through Fermentation with the Kombucha Consortium. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidah, E.; Afgani, C.A.; Kalsum, U.; Srianta, I.; Blanc, P.J. Comparison of in Vivo Antidiabetes Activity of Snake Fruit Kombucha, Black Tea Kombucha and Metformin. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.L.; Netto, M.C.; Bendel Junior, L.; de Moura, L.F.; Brasil, G.A.; Bertolazi, A.A.; de Lima, E.M.; Vasconcelos, C.M. Kombucha Fermentation in Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) Beverage and Its in Vivo Gastroprotective Effect: Preliminary Study. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.F.; Cavalcante, M.P.; Sensheng, Y.; dos Santos Silva, S.; Frota Gaban, S.V. Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, and Sensory Profiles of Kombucha and Kombucha-Like Beverages Prepared Using Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis) and Apple (Malus pumila). ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, C.; Plastina, P.; Cione, E.; Bekatorou, A.; Petsi, T.; Fazio, A. Improved Antioxidant Properties and Vitamin C and B12 Content from Enrichment of Kombucha with Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) Powder. Fermentation 2024, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksornsri, T.; Chaturapornchai, N.; Jitsayen, N.; Rojjanapaitoontip, P.; Peanparkdee, M. Development of Kombucha-like Beverage Using Butterfly Pea Flower Extract with the Addition of Tender Coconut Water. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushargina, R.; Rimbawan, R.; Dewi, M.; Damayanthi, E. Metagenomic Analysis, Safety Aspects, and Antioxidant Potential of Kombucha Beverage Produced from Telang Flower (Clitoria ternatea L.) Tea. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Miranda, J.; Martins Pereira Belo, G.; Silva de Lima, L.; Alencar Silva, K.; Matsue Uekane, T.; Gonçalves Martins Gonzalez, A.; Naciuk Castelo Branco, V.; Souza Pitangui, N.; Freitas Fernandes, F.; Ribeiro Lima, A. Arabic Coffee Infusion Based Kombucha: Characterization and Biological Activity during Fermentation, and in Vivo Toxicity. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos Santos, L.; Roselino, M.N.; de Carvalho Alves, J.; Viana, S.N.A.; dos Reis Requião, E.; dos Santos Ferro, J.M.R.B.; de Souza, C.O.; Ribeiro, C.D.F. Production and Characterization of Kombucha-like Beverage by Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) by-Product as Raw Material. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.; Maresca, E.; Aulitto, M.; Termopoli, V.; De Risi, A.; Correggia, M.; Fiorentino, G.; Consonni, V.; Gosetti, F.; Orlandi, M.; et al. Exploiting Agri-Food Residues for Kombucha Tea and Bacterial Cellulose Production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara, G.B.; Do Prado, G.M.; de Sousa, P.H.M.; Viera, V.B.; de Araújo, H.W.C.; Lima, A.R.N.; Filho, A.A.L.A.; Vieira, Í.G.P.; Fernandes, V.B.; Oliveira, L.D.S.; et al. Biotransformation of Tropical Fruit By-Products for the Development of Kombucha Analogues with Antioxidant Potential. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 62, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.; Bouajila, J.; Beaufort, S.; Rizk, Z.; Taillandier, P.; El Rayess, Y. Development of a New Kombucha from Grape Pomace: The Impact of Fermentation Conditions on Composition and Biological Activities. Beverages 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sknepnek, A.; Pantić, M.; Matijašević, D.; Miletić, D.; Lević, S.; Nedović, V.; Nikšić, M. Novel Kombucha Beverage from Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma Lucidum, with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Effects. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2018, 20, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sknepnek, A.; Tomić, S.; Miletić, D.; Lević, S.; Čolić, M.; Nedović, V.; Nikšić, M. Fermentation Characteristics of Novel Coriolus Versicolor and Lentinus Edodes Kombucha Beverages and Immunomodulatory Potential of Their Polysaccharide Extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, D.; de la Fuente-Nieto, L.; Marco, P.; Tejedor-Calvo, E. Elaboration and Characterization of Novel Kombucha Drinks Based on Truffles (Tuber melanosporum and Tuber aestivum) with Interesting Aromatic and Compositional Profiles. Foods 2024, 13, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.R.; Neto, R.O.; dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; do Nascimento, T.P.; Pressete, C.G.; Azevedo, L.; Martino, H.S.D.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Barros, F.A.R. de Kombuchas from Green and Black Teas Have Different Phenolic Profile, Which Impacts Their Antioxidant Capacities, Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France; Council of the European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Teng, J.; Wei, B.; Huang, L.; Xia, N. Phenolic Compounds, Bioactivity, and Bioaccessibility of Ethanol Extracts from Passion Fruit Peel Based on Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmassebi, J.F.; BaniHani, A. Impact of Soft Drinks to Health and Economy: A Critical Review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Han, S.E.; Paik, S.S.; Kim, Y.J. Corrosive Esophageal Injury Due to a Commercial Vinegar Beverage in an Adolescent. Clin. Endosc. 2020, 53, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaashyap, M.; Cohen, M.; Mantri, N. Microbial Diversity and Characteristics of Kombucha as Revealed by Metagenomic and Physicochemical Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, R.; Marimuthu, S.; Swaminathan, K. Changes in Content of Organic Acids and Tea Polyphenols during Kombucha Tea Fermentation. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, Y.E.; Tuenter, E.; Breynaert, A.; Foubert, K.; Herawati, H.; Hariati, A.M.; Aulanni’am, A.; De Bruyne, T.; Hermans, N. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Tea and Kombucha from Rhizophora Mucronata Leaves. Beverages 2024, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusoff, I.M.; Mat Taher, Z.; Rahmat, Z.; Chua, L.S. A Review of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Plant Bioactive Compounds: Phenolics, Flavonoids, Thymols, Saponins and Proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A. Concept, Mechanism, and Applications of Phenolic Antioxidants in Foods. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G.R.; Antony, P.J.; de Paula Lana, M.J.M.; da Silva, B.F.X.; Oliveira, R.V.; Jothi, G.; Hariharan, G.; Mohana, T.; Gan, R.Y.; Gurgel, R.Q.; et al. Natural Products Modulating Interleukins and Other Inflammatory Mediators in Tumor-Bearing Animals: A Systematic Review. Phytomedicine 2022, 100, 154038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Tao, L.; Lai, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, L.; Shen, Q.; Liu, D.; et al. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polysaccharides from Ginkgo Biloba: Process Optimization, Composition and Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S.; Patel, K.; Belgamwar, V.; Wadher, K. Functional Polysaccharide Lentinan: Role in Anti-Cancer Therapies and Management of Carcinomas. Pharmacol. Res.—Mod. Chin. Med. 2022, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Deng, Z.; Qin, X.; Nie, J.; Qiao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, S. Structural Features and in Vitro Antitumor Activity of a Water-Extracted Polysaccharide from Ganoderma applanatum. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 13205–13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeem, M.I.; Bankole, H.A.; Fatai, A.A.; Saibu, G.M.; Wusu, A.D. Genus Aloe as Sources of Antidiabetic, Antihyperglycemic and Hypoglycemic Agents: A Review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarz-Blanch, N.; Morales, D.; Calvo, E.; Ros-Medina, L.; Muguerza, B.; Bravo, F.I.; Suárez, M. Role of Chrononutrition in the Antihypertensive Effects of Natural Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Qin, Y. Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Disease: Current Knowledge, Existing Challenges, and New Opportunities for Management Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Piao, J.; Zhu, L.; Yao, L.; Liu, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; et al. The Effects of Different Extraction Methods on Physicochemical, Functional and Physiological Properties of Soluble and Insoluble Dietary Fiber from Rubus chingii Hu. Fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 93, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, S.E.; Fletcher, M.H.; Wuest, W.M. Natural Products as Platforms to Overcome Antibiotic Resistance. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 12415–12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, H.; Papadopoulou, C. Antimicrobial Activity of Basil, Oregano, and Thyme Essential Oils. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Adhikari, K. Current Trends in Kombucha: Marketing Perspectives and the Need for Improved Sensory Research. Beverages 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, K.; Prajapati, J.; Patel, D.; Patel, R.; Varshnei, A.; Saraf, M.; Goswami, D. Multidisciplinary Advances in Kombucha Fermentation, Health Efficacy, and Market Evolution. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.K.A.; Wang, B.; Lima, E.M.F.; Shebeko, S.K.; Ermakov, A.M.; Khramova, V.N.; Ivanova, I.V.; Rocha, R.d.S.; Vaz-Velho, M.; Mutukumira, A.N.; et al. Kombucha: An Old Tradition into a New Concept of a Beneficial, Health-Promoting Beverage. Foods 2025, 14, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyt, R.W.; Lie, F.B.; Wilderom, C.P.M. The Origins of SWOT Analysis. Long Range Plan. 2023, 56, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alternative Substrate Group | Specific Substrate | pH | Total Soluble Solids (° Brix) | Total Carbohydrates (% w/v) | Ethanol (% v/v) | Soluble Proteins (µg/mL) | Acetic Acid (g/L) | Acidity (g/L) | Total Phenolic Compounds (mg/100 mL) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plants/herbs | Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | 2.4–3.5 | - | - | - | - | 2–15 (approx.) | 1.3–17.8 | 14–34 | [16] |

| Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) | 3.0–4.5 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | - | - | <10–61.9 | [17] | |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale) | 3.2–5.2 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | - | - | <10–75.3 | [17] | |

| Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) | 3.1–4.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 2.1–8.1 | 70.8–85.0 | [18] | |

| Turmeric (Curcuma longa) | 2.9–6.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10–80 | [19] | |

| Winter savory (Satureja montana) | <3–>4 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.18–0.48 | <0.4–2 (approx.) | 6–10 | [20] | |

| Wild thyme (Thymus serpyllum) | <3–>4 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.41–0.60 | <1–<2.5 (approx.) | 9–11 | [20] | |

| Purple basil (Ocilum basilicum) | 3.0–3.1 | 7.1–8.5 | - | - | - | - | 8.0–8.4 (titratable) | 22.5–26.6 | [21] | |

| Hempseeds hearts (Cannabis sativa sativa) | - | - | - | - | 0.3–7.8 | - | - | 10.5–88.1 | [22] | |

| Leaves | Oak leaves (Quercus resinosa, Quercus arizonica, and Quercus convallata) | 2.8–3.5 | - | Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | - | - | - | - | Individual species were identified and quantified | [23] |

| Oak leaves (Q. convallata and Q. arizonica) | 3.2–3.3 | 10.1–10.4 | Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | - | - | - | 66–68 | Individual species were identified and quantified | [24] | |

| African mustard leaves (Brassica tournefortii) | 3.0–7.0 | - | Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | 0.0–1.4 | - | 0–14 | - | 17.5–27.0 (mg/100 mg) | [25] | |

| Peppermint leaves (Mentha piperita) | <3–>5 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.12–1.94 | 0.1–4.5 (approx.) | 10–15 | [20] | |

| Stinging nettle leaves (Urtica dioica) | <3–4 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.18–3.03 | <0.5–5 (approx.) | 8–11 | [20] | |

| Quince leaves (Cydonia oblonga) | 3–5 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.14–2.39 | <1–<2.5 (approx.) | 11–12 | [20] | |

| Ginkgo biloba leaves | 2.6–3.8 | 10.7–17.0 | - | - | - | - | 0.2–1.8 | 480–870 (approx.) | [26] | |

| Indonesian bay leaf (Syzygium polyanthum) | 2.9–3.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [27] | |

| Fruits | Summer (cherry: Prunus avium; plum: Prunus domestica; strawberry: Fragaria × ananassa; apricot: Prunus armeniaca) and winter (persimmon: Diospyros kaki; grape: Vitis vinifera; orange: Citrus × sinensis; pomegranate: Punica granatum) fruits | 2.0–4.1 | - | 1.5–11.1 | 0.0–3.1 | - | - | - | 1.3–17.6 | [15] |

| Strawberry tree fruit (Arbutus unedo) | 2.9–3.6 | - | 1.4–11.0 | - | 0.2–3.1 | - | - | 4.3–19.7 | [28] | |

| Papaya (pulps and leaves) (Carica papaya) | 2.8–6.1 | 7 (approx.)–14 (approx.) | - | 0.0–1.2 | - | 0.0–1.6 | - | - | [29] | |

| Red grape (V. vinifera) | 2.9–4.0 | - | - | 0.0–0.9 | - | - | 25.9–104.2 (meq/L) | 210–350 (approx.) | [30] | |

| Apple (Malus domestica) | 3.0–3.5 (approx.) | - | Total sugars: 4–17 (approx.) | - | - | - | 4–17 | 17.5–35 (approx.) | [31] | |

| Black mulberry (Morus nigra) | 2.8–4.0 | 8.2–9.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 23.8–26.6 | [32] | |

| Black grape (Vitis lambrusca) | 2.5–3.5 | 6.9–7.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 14.3–16.0 | [32] | |

| Rosehip fruit (Rosa canina) | 2.6–3.3 | 7.1–7.8 | - | - | - | - | - | 6.7–7.2 | [32] | |

| Indian gooseberry (Phyllanthus emblica) | 2.2–4.0 | 5.3–13.0 | - | 0.0–2.1 | - | 6.7–46.7 | - | 5–70 (approx.) | [33] | |

| Snake fruit (Salacca zalacca) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.4–16.5 | 27.5–62.3 | [34] | |

| Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | 3.2–3.9 | 12.9–13.9 | - | - | - | - | 5.7–15.6 | 28.1–53.6 | [35] | |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) | 3.1–3.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96.3–116.7 | [36] | |

| Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) | 3.2–3.5 | 4.0–13.1 | - | 6.2 | 300 (total protein) | - | 11.3 | 13.2 | [37] | |

| Apple (Malus pumila) | 3.5–4.2 | 12.0–17.0 | - | 1.7 | 100 (total protein) | - | 8.2 | 29.3 | [37] | |

| Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) | 2.9–3.5 | - | Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | 0–1.4 | 1.8–5 | 0–31 | - | 0.9–1.2 | [38] | |

| Flowers | Elderberry flowers (Sambucus nigra) | <3–4 (approx.) | - | - | - | - | 0.91–6.90 | 1–>15 (approx.) | 8–12 | [20] |

| Butterfly pea flower (Clitoria ternatea) | 2.5–5.4 | 13.0–25.3 | Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | - | - | 0–12.31 | 0–0.8 | 9–34 | [39] | |

| Butterfly pea flower (C. ternatea) | 3.5 | - | - | 0.2 | - | 1.65 | - | 129.4 | [40] | |

| Seeds/grains | Arabic coffee (Coffea arabica) | 3.3–4.5 | 4.0–5.2 | Reducing sugars: 3.9–5.1 | - | - | - | 0.8–7.2 | 51.1–57.1 | [41] |

| Vegetal by-products | Cocoa bean shell (Theobroma cacao) | 3.2–4.2 | 7–8 (approx.) | - | 0 | 1–3 (mg/L, approx.) | 9–24 (approx.) | [42] | ||

| Citrus fruit residues and spent coffee grounds (C. arabica) | 4.0–5.0 | - | Cellulose production was measured | - | - | - | - | 2.9 | [43] | |

| Guava by-products (Psidium guajava) | 2.9–3.5 | 7.3–8.1 | - | - | - | 7.3 | 2.6–7.5 | - | [44] | |

| Acerola by-products (Malpighia emarginata) | 2.6–3.0 | 6.6–7.5 | - | - | - | 14.7 | 3.2–9.4 | - | [44] | |

| Tamarind by-products (Tamarindus indica) | 2.8–3.2 | 7.4–8.3 | - | - | - | 5 | 4.4–10.0 | - | [44] | |

| Grape pomace (Vitis vinifera) | 2.9–3.4 | 2.1–5.3 | Total sugars: 0.7–5.7 | 0.1–1.0 | - | 1.0–13.0 | 3.4–12.4 | 17.6–50.7 | [45] | |

| Mushrooms | Reishi mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum) | 2.8–4.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 2.5–22.8 | 24.5 | [46] |

| Turkey tail mushroom (Trametes versicolor) | 3.0–5.2 | - | Total polysaccharides, sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | 0.0–3.1 | - | - | 1.0 (approx.)–33.5 | 19 | [47] | |

| Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) | 3.2–5.4 | - | Total polysaccharides, sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified | 0.0–4.3 | - | - | 1.0 (approx.)–23.4 | 33 | [47] | |

| Truffles | Black truffle (Tuber melanosporum) | 2.5–5.6 | - | 2.5–7.4 | 0.0–1.6 | 7.5–31.0 | - | - | 1.8–50.7 | [48] |

| Summer truffle (Tuber aestivum) | 2.8–5.7 | - | 1.8–6.4 | 0.0–0.7 | 4.0–36.4 | - | - | 4.3–64.4 | [48] |

| Biological Activity | Main Bioactive Compound/s | Alternative Substrate Group | Specific Substrate | Experimental Model/Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant | Phenolic compounds | Plants/herbs | Lemon balm (M. officinalis) | Radical-scavenging assays | [18] |

| Turmeric (C. longa) | Radical-scavenging assays | [19] | |||

| Ginger (Z. officinale) | Radical-scavenging assays | [17] | |||

| Liquorice (G. uralensis) | Radical-scavenging assays | [17] | |||

| Hempseed hearts (C. sativa sativa) | Radical-scavenging assays | [22] | |||

| Leaves | Oak leaves (Q. resinosa, Q. arizonica, and Q. convallata) | THP-1 human monocytic cells | [23] | ||

| Oak leaves (Q. convallata and Q. arizonica) | Radical-scavenging assays; C57BL/6 mice | [24] | |||

| African mustard leaves (B. tournefortii) | Radical-scavenging assays | [25] | |||

| Ginkgo biloba leaves | Radical-scavenging assays | [26] | |||

| Fruits | Summer (cherry: P. avium; plum: P. domestica; strawberry: Fragaria x ananassa; apricot: P. armeniaca-) and winter (persimmon: D. kaki; grape: V. vinifera; orange: Citrus x sinensis; pomegranate: P. granatum-) fruits | Radical-scavenging assays | [15] | ||

| Apple (M. domestica) | Radical-scavenging assays | [31] | |||

| Black mulberry (M. nigra) | Radical-scavenging assays | [32] | |||

| Black grape (V. lambrusca) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Rosehip fruits (R. canina) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Blueberry (V. myrtillus) | Radical-scavenging assays | [36] | |||

| Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | Wistar rats | [35] | |||

| Flowers | Butterfly pea flower (C. ternatea) | Radical-scavenging assays | [39] | ||

| Seeds/grains | Arabic coffee (C. arabica) | Radical-scavenging assays | [41] | ||

| By-products | Cocoa bean shell (T. cacao) | Radical-scavenging assays | [42] | ||

| Citrus fruit residues and spent coffee grounds (C. arabica) | Radical-scavenging assays | [43] | |||

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids) | Plants/herbs | Purple basil (O. basilicum) | Radical-scavenging assays | [21] | |

| Winter savory (S. montana) | Radical-scavenging assays | [20] | |||

| Wild thyme (T. serpyllum) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Leaves | Peppermint leaves (M. piperita) | Radical-scavenging assays | |||

| Stinging nettle leaves (U. dioica) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Quince leaves (C. oblonga) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Flowers | Elderberry flowers (S. nigra) | Radical-scavenging assays | |||

| Mushrooms | Reishi mushroom (G. lucidum) | Radical-scavenging assays | [46] | ||

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids); DSL | Fruits | Indian gooseberry (P. embilica) | Radical-scavenging assays | [33] | |

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids), ascorbic acid, and vitamin B12 | Jujube (Z. jujuba) | Radical-scavenging assays | [38] | ||

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids and anthocyanins) | Flowers | Butterfly pea flower (C. ternatea) | Radical-scavenging assays | [40] | |

| Fruits | Red grape (V. vinifera) | Radical-scavenging assays | [30] | ||

| Grape pomace (V. vinifera) | Radical-scavenging assays | [45] | |||

| Phenolic compounds and organic acids | Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | Radical-scavenging assays | [34] | ||

| - | By-products | Guava by-products (P. guajava) | Radical-scavenging assays | [44] | |

| Acerola by-products (M. emarginata) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Tamarind by-products (T. indica) | Radical-scavenging assays | ||||

| Immune-modulatory | Phenolic compounds | Leaves | Oak leaves (Q. resinosa, Q. arizonica, and Q. convallata) | THP-1 human monocytic cells | [23] |

| Phenolic compounds (anthocyanins) | Fruits | Grape pomace (V. vinifera) | 5-lipoxygenase inhibition assay | [45] | |

| Polysaccharides and phenolic compounds | Mushrooms | Turkey tail mushroom (T. versicolor) | PBMCs | [47] | |

| Shiitake mushroom (L. edodes) | PBMCs | [47] | |||

| Antiproliferative/antitumoral | Phenolic compounds | Plants/herbs | Turmeric (C. longa) | A-431 cells | [19] |

| Leaves | African mustard leaves (B. tournefortii) | MCF-7 cells | [25] | ||

| Phenolic compounds and vitamin C | Plants/herbs | Yarrow (A. millefolium) | RD and Hep2c cells | [16] | |

| Hypoglycemic | Phenolic compounds | Leaves | Oak leaves (Q. convallata and Q. arizonica) | α-amylase and α-glycosidase inhibition assays, glucose diffusion assay, and C57BL/6 mice | [24] |

| Fruits | Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | Wistar rats | [35] | ||

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids and tannins) and saponins | Leaves | Indonesian bay leaf (S. polyanthum) | α-glycosidase inhibition assays | [27] | |

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoid glycosides) | Leaves | Mangrove leaves (Rhizophora mucronata) | α-glycosidase inhibition assays | [56] | |

| Phenolic compounds (anthocyanins) | Fruits | Grape pomace (V. vinifera) | α-amylase and α-glycosidase inhibition assays | [45] | |

| Antihypertensive | Phenolic compounds (flavonoids) | Plants/herbs | Winter savory (S. montana) | ACE inhibition assay | [20] |

| Wild thyme (T. serpyllum) | ACE inhibition assay | ||||

| Leaves | Peppermint leaves (M. piperita) | ACE inhibition assay | |||

| Stinging nettle leaves (U. dioica) | ACE inhibition assay | ||||

| Quince leaves (C. oblonga) | ACE inhibition assay | ||||

| Flowers | Elderberry flowers (S. nigra) | ACE inhibition assay | |||

| Hypolipidemic/hypocholesterolemic | Phenolic compounds | Fruits | Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | Wistar rats | [35] |

| Antimicrobial | Phenolic compounds | Plants/herbs | Turmeric (C. longa) | Microbiological analyses | [19] |

| Lemon balm (M. officinalis) | [18] | ||||

| Fruits | Apple (M. domestica) | [31] | |||

| Black mulberry (M. nigra) | [32] | ||||

| Black grape (V. lambrusca) | |||||

| Rosehip fruits (R. canina) | |||||

| Phenolic compounds and organic acids | Fruits | Snake fruit (S. zalacca) | [34] | ||

| Phenolic compounds | Seeds/grains | Arabic coffee (C. arabica) | [41] | ||

| Phenolic compounds (flavonoids) | Mushrooms | Reishi mushroom (G. lucidum) | [46] | ||

| Phenolic compounds (anthocyanins) | Fruits | Red grape (V. vinifera) | [30] | ||

| Phenolic compounds and vitamin C | Plants/herbs | Yarrow (A. millefolium) | [16] | ||

| Neuroprotective | Phenolic compounds | Leaves | African mustard leaves (B. tournefortii) | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition assay | [25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hontana-Moreno, N.; Morales, D. Biological Activities of Novel Kombuchas Based on Alternative Ingredients to Replace Tea Leaves. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111722

Hontana-Moreno N, Morales D. Biological Activities of Novel Kombuchas Based on Alternative Ingredients to Replace Tea Leaves. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111722

Chicago/Turabian StyleHontana-Moreno, Noemi, and Diego Morales. 2025. "Biological Activities of Novel Kombuchas Based on Alternative Ingredients to Replace Tea Leaves" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111722

APA StyleHontana-Moreno, N., & Morales, D. (2025). Biological Activities of Novel Kombuchas Based on Alternative Ingredients to Replace Tea Leaves. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111722