Phytochemical Characterization of Astragalus boeticus L. Extracts, Diuretic Activity Assessment, and Oral Toxicity Prediction of Trans-Resveratrol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Identification of the Extracts

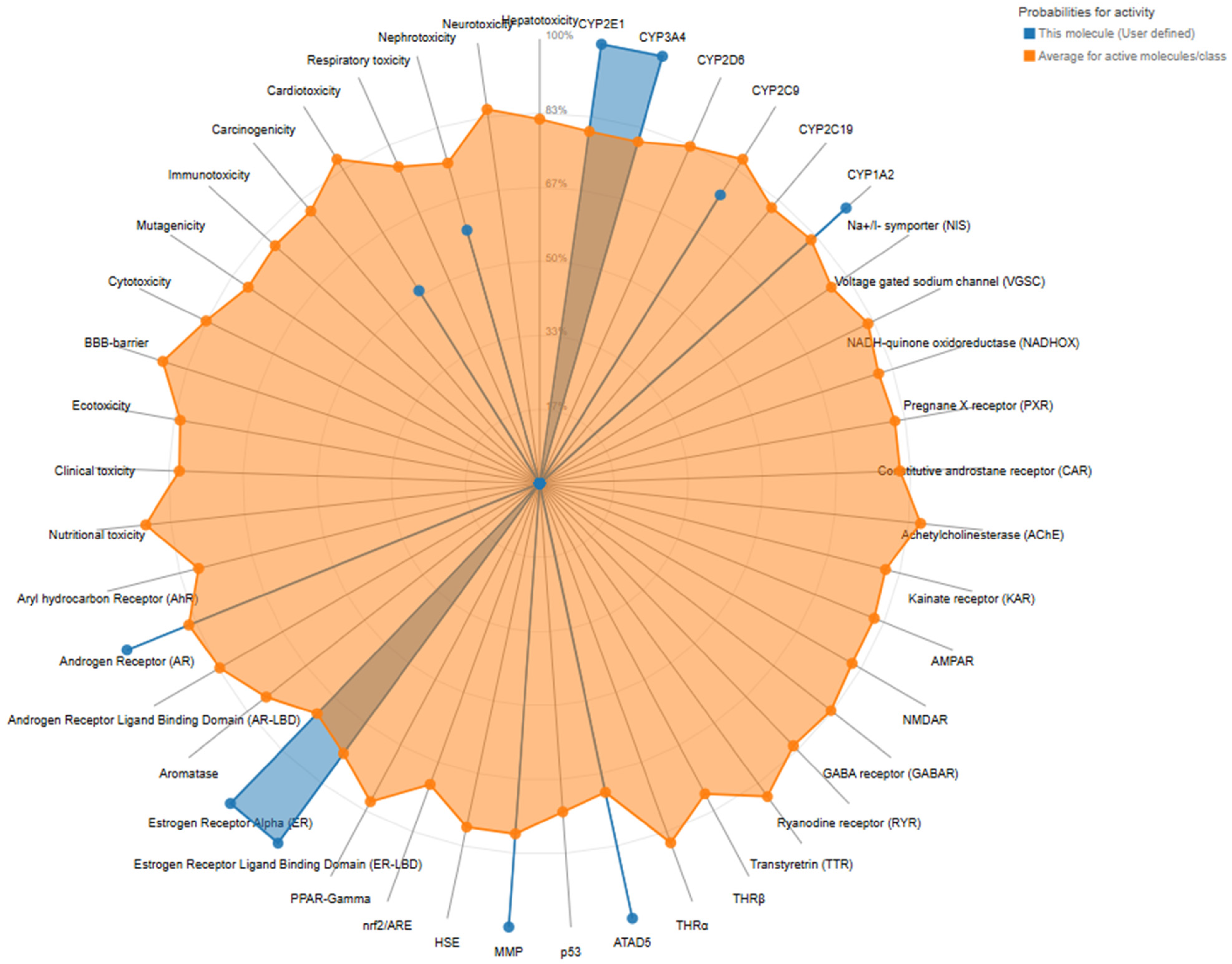

2.2. Predictive Toxicological Characterization of Trans-Resveratrol from A. boeticus

2.3. Subchronic Diuretic Treatment

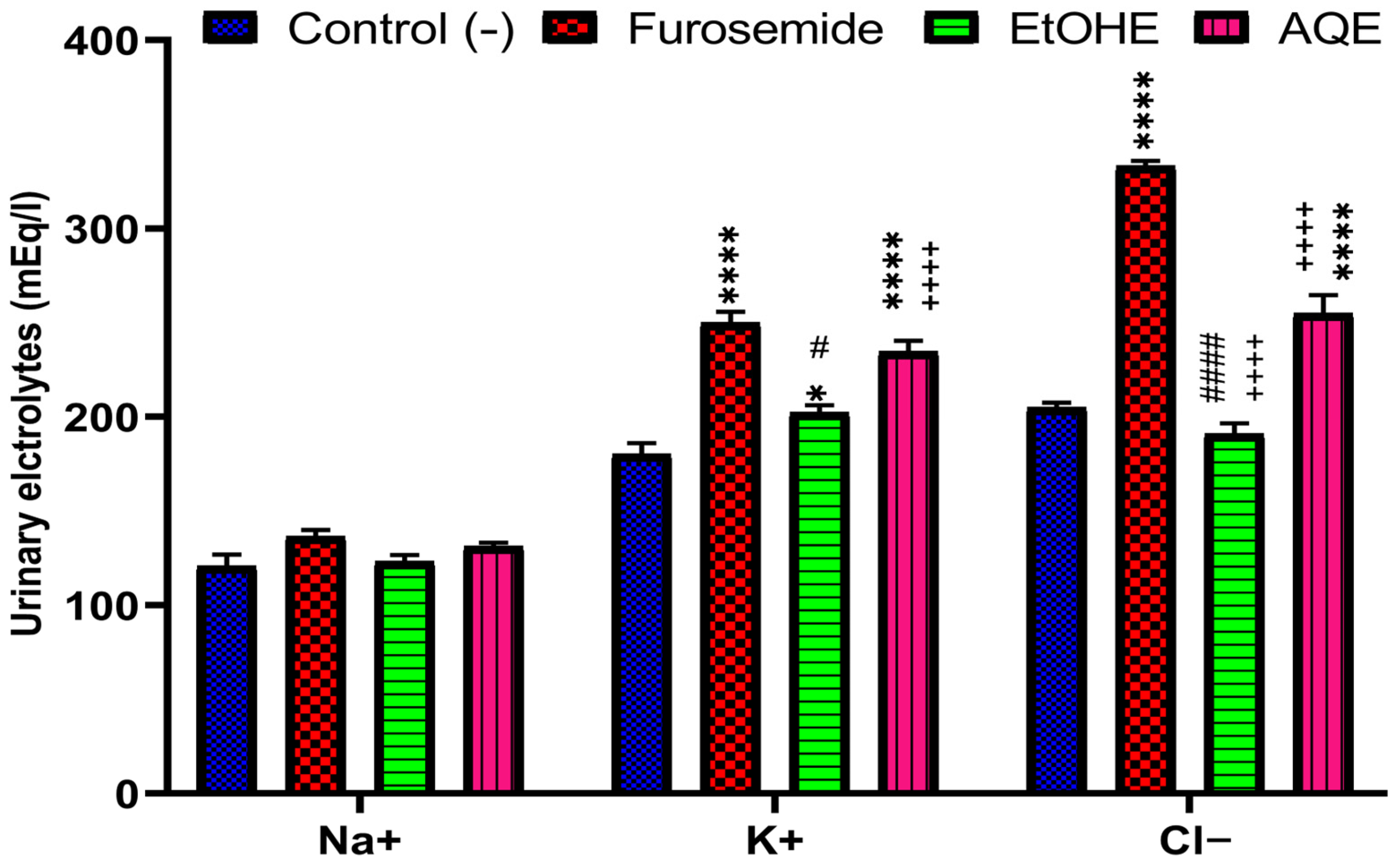

2.3.1. Impact of AQE and EtOHE on Urinary Electrolyte Excretion

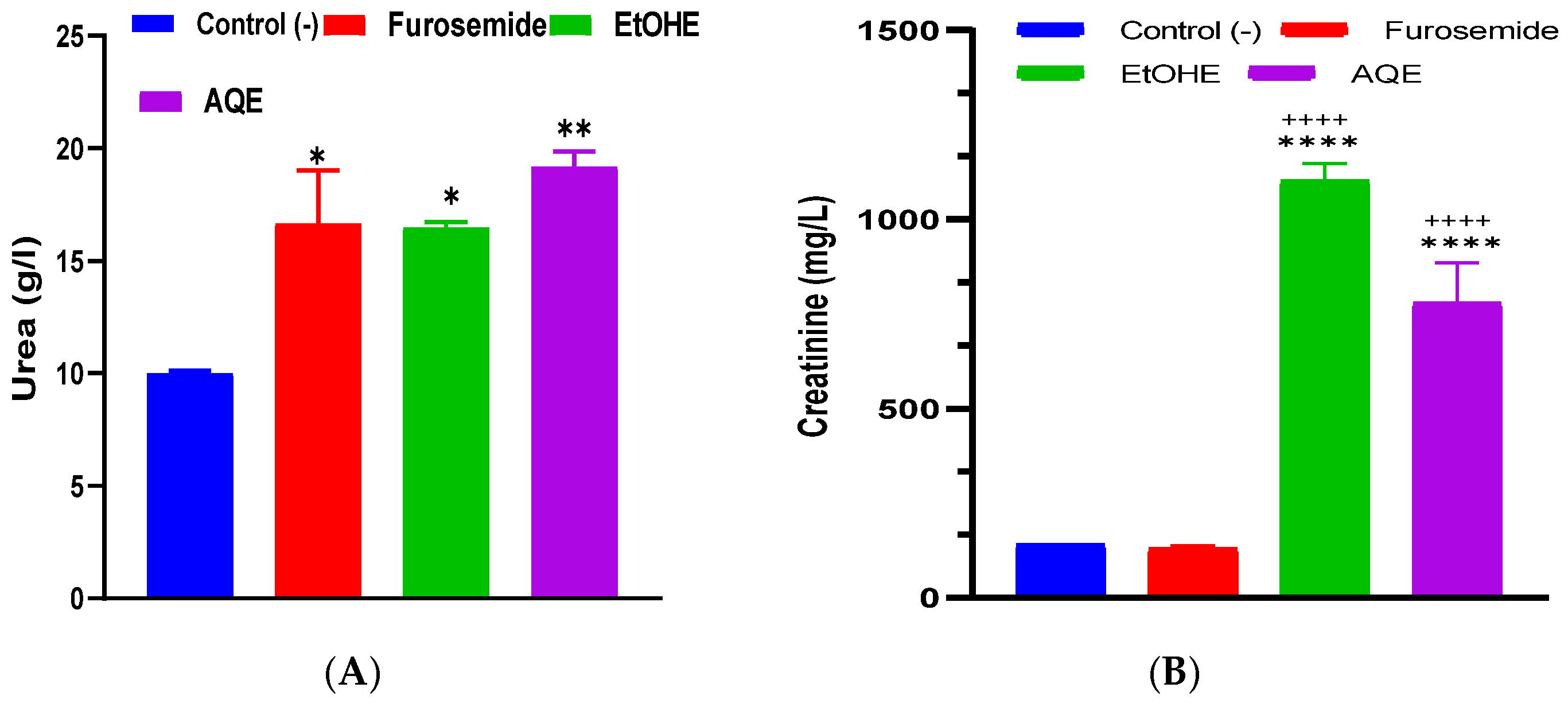

2.3.2. Impact of AQE and EtOHE on Urinary Urea and Creatinine

2.3.3. Impact of AQE and EtOHE on Plasma Electrolyte Level

2.3.4. Impact on Plasma Urea and Creatinine Levels

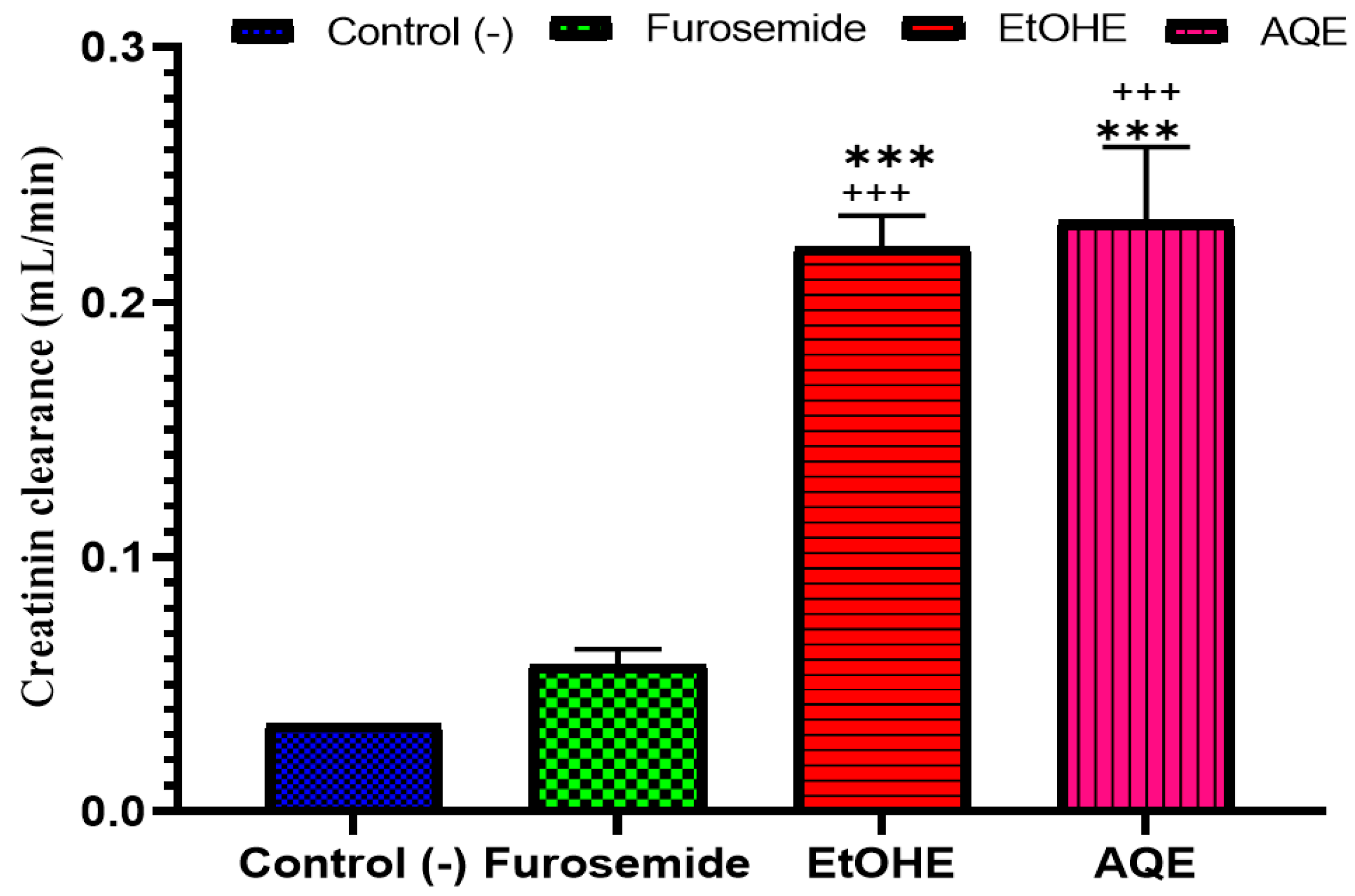

2.3.5. Impact of AQE and EtOHE on Creatinine Clearance

2.3.6. Impact of AQE and EtOHE on Hepatic Biochemical Parameters

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Extract Preparation

4.3. Analysis by LC-MS/MS of A. boeticus Extracts

4.4. In Silico Toxicological Profiling of Trans-Resveratrol from A. boeticus

4.4.1. Phytochemical Target Compound

4.4.2. Toxicological Evaluation

4.5. Evaluation of the Diuretic Effect of A. boeticus Extracts

4.5.1. Animals

4.5.2. Experimental Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, J.; Peng, A.; Lin, S. Mechanisms of the Therapeutic Effect of Astragalus Membranaceus on Sodium and Water Retention in Experimental Heart Failure. Chin. Med. J. 1998, 111, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arumugham, V.; Shahin, M. Therapeutic Uses of Diuretic Agents; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hailu, W.; Engidawork, E. Evaluation of the Diuretic Activity of the Aqueous and 80% Methanol Extracts of Ajuga Remota Benth (Lamiaceae) Leaves in Mice. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaradat, N.A.; Zaid, A.N.; Abuzant, A.; Khalaf, S.; Abu-Hassan, N. Phytochemical and Biological Properties of Four Astragalus Species Commonly Used in Traditional Palestinian Medicine. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhavar, P.; Deshpande, D.S. Recent Updates On Medicinal Potentiality of Fabaceae Family: Critical. Int J Pharm Sci Critical Review. Int. J. Pharm. Bio Sci. 2022, 13, b32–b41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klichkhanov, N.K.; Suleimanova, M.N. Chemical Composition and Therapeutic Effects of Several Astragalus Species (Fabaceae). Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2024, 518, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, V.; Esposito, A.; Scognamiglio, M.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; Ciardiello, F.; Troiani, T.; Potenza, N.; Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B. Spectroscopic Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment towards Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines of Acylated Cycloartane Glycosides from Astragalus boeticus L. Molecules 2019, 24, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anywar, G.; Kakudidi, E.; Byamukama, R.; Mukonzo, J.; Schubert, A.; Oryem-Origa, H.; Jassoy, C. A Review of the Toxicity and Phytochemistry of Medicinal Plant Species Used by Herbalists in Treating People Living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 615147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseha, S.T.; Mekonnen, Y.; Desalegn, A.; Eyado, A.; Wondafarsh, M. Toxicity Study and Antibacterial Effects of the Leaves Extracts of Boscia coriacea and Uvaria Leptocladon. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2022, 32, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agour, A.; Soulo, N.; Bassouya, M.; EL Hajjaji, M.A.; Bari, A.; Derwich, E. HPLC Analysis, Hemolytic Activity, and Acute Toxicity of Haplophyllum tuberculatum (Forssk.) Aqueous Extract and in Silico Study. J. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2025, 1, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Agour, A.; Mssillou, I.; El Abdali, Y.; Bari, A.; Lyoussi, B.; Derwich, E. Phytochemical Characterization, Acute Toxicity and Hemolytic Activity of Cotula cinerea (Del.) Aqueous and Ethanolic Extracts. J. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2024, 1, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Sener, B.; Kilic, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Resveratrol: A Double-Edged Sword in Health Benefits. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, L.G.; D’Orazio, J.A.; Pearson, K.J. Resveratrol and Cancer: Focus on in Vivo Evidence. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, R209–R225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangeni, R.; Sahni, J.K.; Ali, J.; Sharma, S.; Baboota, S. Resveratrol: Review on Therapeutic Potential and Recent Advances in Drug Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervaiz, S.; Holme, A.L. Resveratrol: Its Biologic Targets and Functional Activity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2851–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: The in Vivo Evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Phenolics Content in Astragalus Species. Pak. J. Bot 2002, 34, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, C.-C.; Olah, N.-K.; Vlase, L.; Mogoșan, C.; Mocan, A. Comparative Studies on Polyphenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Diuretic Effects of Nigella sativa L. (Black Cumin) and Nigella damascena L. (Lady-in-a-Mist) Seeds. Molecules 2015, 20, 9560–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vizcaino, F.; Duarte, J. Flavonols and Cardiovascular Disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010, 31, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Pérez-Palencia, R.; Vargas, F.; Angeles Ocete, M.; Pérez-Vizcaino, F.; Zarzuelo, A.; Tamargo, J. Antihypertensive Effects of the Flavonoid Quercetin in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 133, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moussaoui, A.; Bourhia, M.; Jawhari, F.Z.; Khalis, H.; Chedadi, M.; Agour, A.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Alzahrani, A.; Alyahya, H.K.; Alotaibi, A. Responses of Withania frutescens (L.) Pauquy (Solanaceae) Growing in the Mediterranean Area to Changes in the Environmental Conditions: An Approach of Adaptation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 666005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, E.; Odabaş Köse, E.; Yavuz, M.; Kilit, A.C.; Korkut, A.; Özkaya Gül, S.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Celep, M.E.; Göktürk, R.S. Phenolic Compound Profiles, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Potentials and Molecular Docking Studies of Astragalus gymnolobus Methanolic Extracts. Plants 2024, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikurkcu, C.; Zengin, G. Polyphenol Profile and Biological Activity Comparisons of Different Parts of Astragalus macrocephalus Subsp. Finitimus from Turkey. Biology 2020, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S. Diuretics in Primary Hypertension–Reloaded. Indian Heart J. 2016, 68, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loew, D.; Loew, D.; Heimsoth, V.; Kuntz, E.; Schilcher, H. Diuréticos: Química, Farmacología y Terapéutica Incluida Fitoterapia; Salvat: Barcelona, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wargo, K.A.; Banta, W.M. A Comprehensive Review of the Loop Diuretics: Should Furosemide Be First Line? Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adin, D.; Atkins, C.; Papich, M.G. Pharmacodynamic Assessment of Diuretic Efficacy and Braking in a Furosemide Continuous Infusion Model. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2018, 20, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghouizi, A.; El Menyiy, N.; Falcão, S.I.; Vilas-Boas, M.; Lyoussi, B. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Activity, and Diuretic Effect of Moroccan Fresh Bee Pollen in Rats. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.; Ghizlane, N.; Widad, T.; Chebaibi, M.; Alhalmi, A.; Soulo, N.; Alnasser, S.M.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Badiaa, L. HPLC-DAD Profiling and Diuretic Effect of Solanum elaeagnifolium (Cav.) Aqueous Extract: A Combined Experimental and Computational Approach. Phyton 2025, 94, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tbatou, W.; Aboulghazi, A.; El Ghouizi, A.; El-Yagoubi, K.; Soulo, N.; Ouaritini, Z.B.; Lyoussi, B. Phenolic Screening, Antioxidant Activity and Diuretic Effect of Moroccan Pinus pinaster Bark Extract. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine 2025, 15, 1450. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A. Drugs Affecting Renal Excretory Function. In Introduction to Basics of Pharmacology and Toxicology: Volume 2: Essentials of Systemic Pharmacology: From Principles to Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou, S.; Tahraoui, A.; Israili, Z.; Lyoussi, B. Diuretic Activity of the Aqueous Extracts of Carum carvi and Tanacetum vulgare in Normal Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurikova, T.; Skrovankova, S.; Mlcek, J.; Balla, S.; Snopek, L. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, and Biological Effects of European Cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos). Molecules 2018, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Bungau, S.; Kumar, K.; Zengin, G.; Khan, F.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, R.; Venkatachalam, T.; Tit, D.M.; Vesa, C.M. Pleotropic Effects of Polyphenols in Cardiovascular System. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikós, E.; Horváth, A.; Ács, K.; Papp, N.; Balázs, V.L.; Dolenc, M.S.; Kenda, M.; Kočevar Glavač, N.; Nagy, M.; Protti, M. Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Natural Drugs. Molecules 2021, 26, 7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, N.D.; Khatib, A.; Link-Struensee, A.M.R.; Ijzerman, A.P.; Rungkat-Zakaria, F.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Adenosine A1 Receptor Binding Activity of Methoxy Flavonoids from Orthosiphon stamineus. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Xi, Y.; Jiang, W. Protective Roles of Flavonoids and Flavonoid-Rich Plant Extracts against Urolithiasis: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdala, S.; Martín-Herrera, D.; Benjumea, D.; Gutiérrez, S.D. Diuretic Activity of Some Smilax Canariensis Fractions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-GÃ3mez, A.; Pablo-PÃ, S.S.; MelÃ, M.E. Diuretic Activity of Aqueous Extract and Smoothie Preparation of Verbesina crocata in Rat. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2018, 13, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateel, R.; Rai, M.S.; Kumar, A.J. Evaluation of Diuretic Activity of Gallic Acid in Normal Rats. JSIR J 2014, 3, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Kee, H.J.; Jin, L.; Ryu, Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, G.R.; Jeong, M.H. Gentisic Acid Attenuates Pressure Overload-induced Cardiac Hypertrophy and Fibrosis in Mice through Inhibition of the ERK 1/2 Pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 5964–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, N.-A.; Roudsari, N.M.; Momtaz, S.; Abdolghaffari, A.H.; Atkin, S.L.; Sahebkar, A. Regulatory Mechanisms of Vanillic Acid in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 2562–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloud, B. Effects of Cyanidin 3-O-Glucoside on Cardiovascular Complications and Immune Response in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A.; Akhtar, M.F.; Sharif, A.; Akhtar, B.; Siddique, R.; Ashraf, G.M.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Alharthy, S.A. Anticancer, Cardio-Protective and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Natural-Sources-Derived Phenolic Acids. Molecules 2022, 27, 7286. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Li, X.; Luo, X.; Sha, Y.; Gong, P.; Gu, J.; Tan, R. Hepatoprotective Effect and Potential Mechanism of Aqueous Extract from Phyllanthus emblica on Carbon-Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5345821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.-C.; Ho, Y.-L.; Huang, G.-J.; Huang, M.-H.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Huang, S.-S.; Hou, W.-C.; Chang, Y.-S. Hepatoprotective Effect of the Aqueous Extract of Flemingia macrophylla on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Acute Hepatotoxicity in Rats through Anti-Oxidative Activities. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2011, 39, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elaziz, M.A.; Mustafa Gouda Elewa, A.; Zaki Mohamed Zaki Abdel Hamid, D.; Essam Soliman Ahmed Hassan, N.; Csongrádi, É.; Hamdy Hamouda Mohammed, E.; Abdel Gawad, M. The Use of Urinary Kidney Injury Molecule-1 and Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for Diagnosis of Hepato-Renal Syndrome in Advanced Cirrhotic Patients. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2346284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A Webserver for the Prediction of Toxicity of Chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An Integrated Online Platform for Accurate and Comprehensive Predictions of ADMET Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Guendouz, S.; Al-Waili, N.; Aazza, S.; Elamine, Y.; Zizi, S.; Al-Waili, T.; Al-Waili, A.; Lyoussi, B. Antioxidant and Diuretic Activity of Co-Administration of Capparis spinosa Honey and Propolis in Comparison to Furosemide. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakour, M.; Al-Waili, N.S.; El Menyiy, N.; Imtara, H.; Figuira, A.C.; Al-Waili, T.; Lyoussi, B. Antioxidant Activity and Protective Effect of Bee Bread (Honey and Pollen) in Aluminum-Induced Anemia, Elevation of Inflammatory Makers and Hepato-Renal Toxicity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 4205–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polyphenols | AqE (µg/g) | EtOHE (µg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Protocatechuic acid | 40 | 33 |

| Vanillic acid | 75 | 81 |

| Gallic acid | 22 | 22 |

| Salicylic acid | 7 | 12 |

| Gentisic acid | 97 | 89 |

| p-Coumaric acid | 75 | 67 |

| Caffeic acid | 1 | - |

| Ferulic acid | 76 | - |

| Sinapic acid | 87 | 7 |

| Trans-resveratrol | 270 | 170 |

| Myricetin | 5 | 1 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | 90 | 90 |

| Petunidin-3-O-glucoside | 1 | 1 |

| Malvidin-3-O-glucoside | 43 | 47 |

| Classification | Target | Shorthand | Prediction | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ toxicity | Hepatotoxicity | dili | Inactive | 0.74 |

| Organ toxicity | Neurotoxicity | neuro | Inactive | 0.77 |

| Organ toxicity | Nephrotoxicity | nephro | Active | 0.59 |

| Organ toxicity | Respiratory toxicity | respi | Inactive | 0.57 |

| Organ toxicity | Cardiotoxicity | cardio | Active | 0.51 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Carcinogenicity | carcino | Inactive | 0.71 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Immunotoxicity | immuno | Inactive | 0.86 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Mutagenicity | mutagen | Inactive | 0.92 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Cytotoxicity | cyto | Inactive | 0.98 |

| Toxicity endpoints | BBB-barrier | bbb | Inactive | 0.55 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Ecotoxicity | eco | Inactive | 0.55 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Clinical toxicity | clinical | Inactive | 0.60 |

| Toxicity endpoints | Nutritional toxicity | nutri | Inactive | 0.89 |

| Nuclear receptor | Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) | nr_ahr | Inactive | 0.63 |

| Nuclear receptor | Androgen Receptor (AR) | nr_ar | Active | 1.0 |

| Nuclear receptor | Androgen Receptor Ligand Binding Domain (AR-LBD) | nr_ar_lbd | Inactive | 0.99 |

| Nuclear receptor | Aromatase | nr_aromatase | Inactive | 0.85 |

| Nuclear receptor | Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ER) | nr_er | Active | 1.0 |

| Nuclear receptor | Estrogen Receptor Ligand Binding Domain (ER-LBD) | nr_er_lbd | Active | 1.0 |

| Nuclear receptor | PPAR-Gamma | nr_ppar_gamma | Inactive | 0.97 |

| Stress response | Nrf2/ARE | sr_are | Inactive | 0.93 |

| Stress response | HSE | sr_hse | Inactive | 0.93 |

| Stress response | MMP | sr_mmp | Active | 1.0 |

| Stress response | p53 | sr_p53 | Inactive | 0.53 |

| Stress response | ATAD5 | sr_atad5 | Active | 1.0 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | THRα | mie_thr_alpha | Inactive | 0.90 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | THRβ | mie_thr_beta | Inactive | 0.78 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | TTR | mie_ttr | Inactive | 0.97 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | RYR | mie_ryr | Inactive | 0.98 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | GABAR | mie_gabar | Inactive | 0.96 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | NMDAR | mie_nmdar | Inactive | 0.92 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | AMPAR | mie_ampar | Inactive | 0.97 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | KAR | mie_kar | Inactive | 0.99 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | AChE | mie_ache | Inactive | 0.74 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | CAR | mie_car | Inactive | 0.98 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | PXR | mie_pxr | Inactive | 0.92 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | NADHOX | mie_nadhox | Inactive | 0.97 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | VGSC | mie_vgsc | Inactive | 0.95 |

| Molecular Initiating Events | NIS | mie_nis | Inactive | 0.98 |

| Metabolism | CYP1A2 | CYP1A2 | Active | 0.92 |

| Metabolism | CYP2C19 | CYP2C19 | Inactive | 0.71 |

| Metabolism | CYP2C9 | CYP2C9 | Active | 0.76 |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6 | CYP2D6 | Inactive | 0.80 |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | Active | 1.0 |

| Metabolism | CYP2E1 | CYP2E1 | Inactive | 0.99 |

| Toxicity Target | Avg Pharmacophore Fit | Avg Similarity Known Ligands | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen Receptor | 1.27% | 78.37% |

| Prostaglandin G/H Synthase 1 | 30.82% | 82.45% |

| Groups | Saluretic Index | Rapport Na+/K+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Potassium | Chloride | ||

| Control | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.67 |

| Furosemide | 1.12 | 1.38 | 1.6 | 0.54 |

| EtOHE | 1.02 | 1.12 | 0.93 | 0.60 |

| AQE | 1.08 | 1.3 | 1.24 | 0.55 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 228.24 g/mol |

| Number of hydrogen bond acceptors | 3 |

| Number of hydrogen bond donors | 3 |

| Number of atoms | 17 |

| Number of bonds | 18 |

| Number of rotatable bonds | 2 |

| Molecular refractivity | 67.88 |

| Topological polar surface area (TPSA) | 60.69 Å2 |

| Octanol/water partition coefficient (logP) | 2.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elidrissi, A.E.; Soulo, N.; Elrherabi, A.; Chelouati, T.; Zwirech, O.; Agour, A.; El-Yagoubi, K.; Tbatou, W.; Nasr, F.A.; Al-zharani, M.; et al. Phytochemical Characterization of Astragalus boeticus L. Extracts, Diuretic Activity Assessment, and Oral Toxicity Prediction of Trans-Resveratrol. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121893

Elidrissi AE, Soulo N, Elrherabi A, Chelouati T, Zwirech O, Agour A, El-Yagoubi K, Tbatou W, Nasr FA, Al-zharani M, et al. Phytochemical Characterization of Astragalus boeticus L. Extracts, Diuretic Activity Assessment, and Oral Toxicity Prediction of Trans-Resveratrol. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121893

Chicago/Turabian StyleElidrissi, Ahmed Elfallaki, Najoua Soulo, Amal Elrherabi, Tarik Chelouati, Otmane Zwirech, Abdelkrim Agour, Karima El-Yagoubi, Widad Tbatou, Fahd A. Nasr, Mohammed Al-zharani, and et al. 2025. "Phytochemical Characterization of Astragalus boeticus L. Extracts, Diuretic Activity Assessment, and Oral Toxicity Prediction of Trans-Resveratrol" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121893

APA StyleElidrissi, A. E., Soulo, N., Elrherabi, A., Chelouati, T., Zwirech, O., Agour, A., El-Yagoubi, K., Tbatou, W., Nasr, F. A., Al-zharani, M., Qurtam, A. A., & Derwich, E. (2025). Phytochemical Characterization of Astragalus boeticus L. Extracts, Diuretic Activity Assessment, and Oral Toxicity Prediction of Trans-Resveratrol. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121893