Impact of Air Temperature and Humidity on Performance of Heat-Source-Free Water-Floating Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thermoelectric Generators for IoT Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

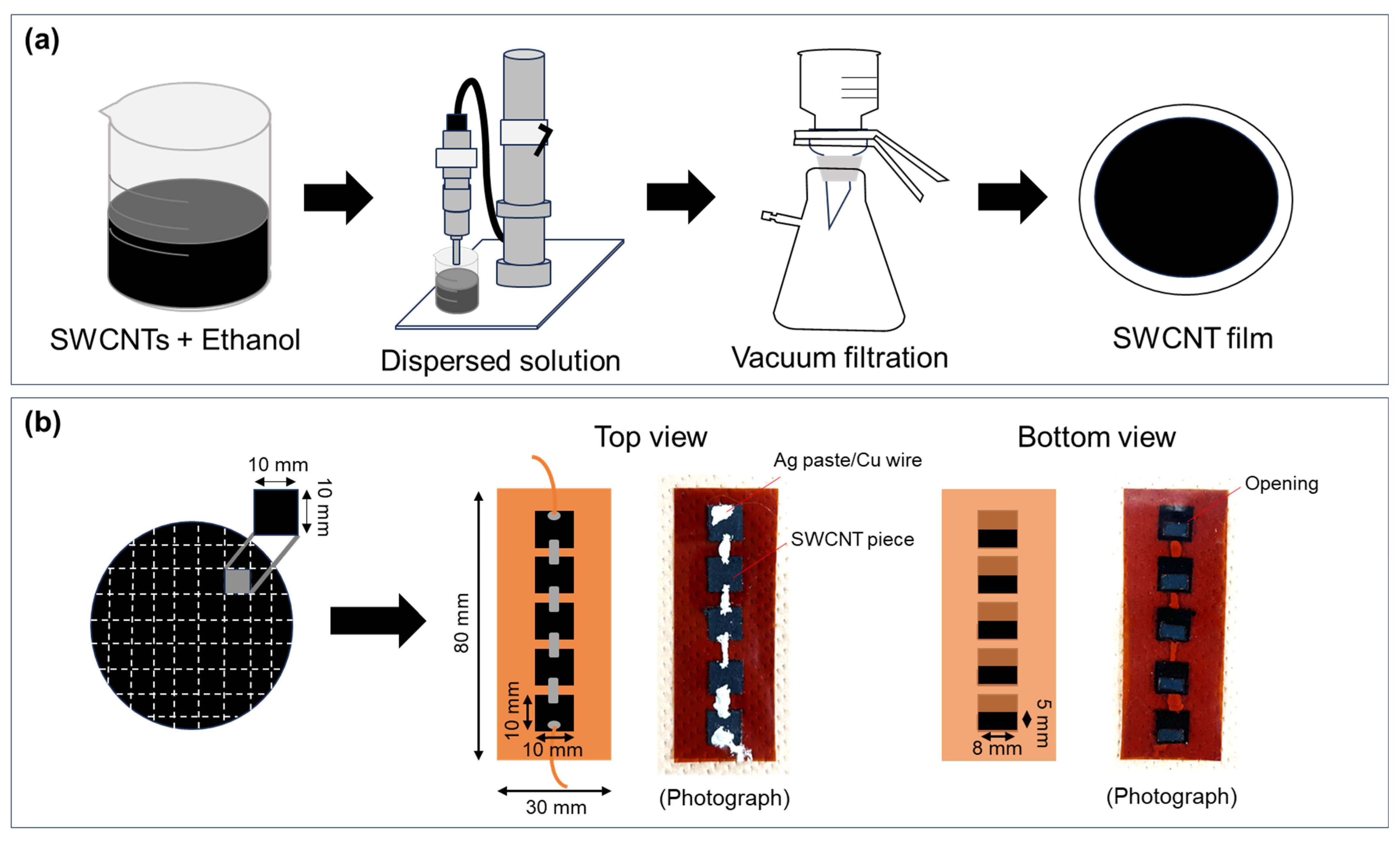

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Properties of SWCNT Powders and Films

3.2. Performance of Water-Floating SWCNT-TEGs at Different Environmental Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Dhar, S.; Singh, R. A decentralized privacy-preserving healthcare blockchain for IoT. Sensors 2019, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, I.U.; Guizani, M.; Hassan, S.; Kim, B.-S.; Khan, M.K.; Atiquzzaman, M. The internet of things: A review of enabled technologies and future challenges. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 7606–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuoi, T.T.K.; Toan, N.V.; Ono, T. Thermal energy harvester using ambient temperature fluctuations for self-powered wireless IoT sensing systems: A review. Nano Energy 2024, 121, 109186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, E.; Meyyappan, M.; Nalwa, H.S. Flexible graphene-based wearable gas and chemical sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 34544–34586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Shu, L.; Yang, Y.; Ren, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; et al. Smart textile-integrated microelectronic systems for wearable applications. Adv. Mater. 2019, 32, 1901958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jin, T.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; He, T.; Wang, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Peng, Y.; Lee, C. Wearable triboelectric sensors enabled gait analysis and waist motion capture for IoT-based smart healthcare applications. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Niyato, D.; Kim, D.I.; Han, Z. Wireless networks with rf energy harvesting: A contemporary survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 757–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeby, S.P.; Tudor, M.J.; White, N.M. Energy harvesting vibration sources for microsystems applications. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, A. Energy harvesting: State-of-the-art. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2641–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.-L.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Ray Liu, K.J. Advances in energy harvesting communications: Past, present, and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. 2016, 18, 1384–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, S.W. Hybrid Energy Harvesters: Toward sustainable energy harvesting. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1802898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Z.; Tang, T.; Deng, J.; Huo, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z. A hybrid nanogenerator based on rotational-swinging mechanism for energy harvesting and environmental monitoring in intelligent agriculture. Sensors 2025, 25, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Karimov, K.S.; Qasuria, T.A.; Ibrahim, M.A. A novel and stable way for energy harvesting from Bi2Te3Se alloy based semitransparent photo-thermoelectric module. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 849, 156702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaziri, N.; Boughamoura, A.; Muller, J.; Mezghani, B.; Tounsi, F.; Ismail, M. A comprehensive review of thermoelectric generators: Technologies and common applications. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, S.; Shiraishi, M.; Yasuda, S.; Juhasz, G.; Du, Y.; Shiraishi, Y.; Toshima, N. Green route for fabrication of water-treatable thermoelectric generators. Energy Mater. Adv. 2022, 12, 9854657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragones, R.; Joan, O.; Ferrer, C. Transforming industrial maintenance with thermoelectric energy harvesting and NB-IoT: A case study in oil refinery applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toan, N.V.; Tuoi, T.T.K.; Ono, T. Thermoelectric generators for heat harvesting: From material synthesis to device fabrication. Sensors 2020, 225, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amma, Y.; Miura, K.; Nagata, S.; Nishi, T.; Miyake, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Takashiri, M. Ultra-long air-stability of n-type carbon nanotube films with low thermal conductivity and all-carbon thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmid, H.J. Bismuth telluride and Its alloys as materials for thermoelectric generation. Materials 2014, 7, 2577–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, T.C.; Paris, B.; Miller, S.E.; Goering, H.L. Preparation and some physical properties of Bi2Te3, Sb2Te3, and As2Te3. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1957, 2, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, C.B.; Ure, R.W., Jr. Electrical and thermal properties of Bi2Te3. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmid, H.J. The electrical conductivity and thermoelectric power of bismuth telluride. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1958, 71, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-G.; Han, G.; Li, L.; Zou, J. Point defect engineering of high-performance bismuth-telluride-based thermoelectric materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 24, 5211–5218. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-P.; Zhu, T.-J.; Wang, Y.-G.; Xie, H.-H.; Xu, Z.-J.; Zhao, X.-B. Shifting up the optimum figure of merit of p-type bismuth telluride-based thermoelectric materials for power generation by suppressing intrinsic conduction. NPG Asia Mater. 2014, 6, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Tang, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tritt, T.M. High thermoelectric performance alloy with unique low-dimensional structure. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 113713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.P.; Liu, X.H.; Xie, H.H.; Shen, J.J.; Zhu, T.J.; Zhao, X.B. Improving thermoelectric properties of n-type bismuth-telluride-based alloys by deformation-induced lattice defects and texture enhancement. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 4431–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimasa, O.; Chiba, T.; Hase, M.; Komori, T.; Takashiri, M. Improvement of thermoelectric properties of flexible Bi2Te3 thin films in bent states during sputtering deposition and post-thermal annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 898, 162889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Yabuki, H.; Takashiri, M. High thermoelectric performance of flexible nanocomposite films based on nanoplates and carbon nanotubes selected using ultracentrifugation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S.; Ichihashi, T. Single-shell carbon nanotubes of 1-nm diameter. Nature 1993, 363, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.L.; Ferguson, A.J.; Cho, C.; Grunlan, J.C. Carbon-nanotube-based thermoelectric materials and devices. Sensors 2018, 30, 1704386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cao, X.; Wen, M.; Chen, C.; Wen, Q.; Fu, Q.; Deng, H. Highly electrical conductive flexible thermoelectric films fabricated by a high-velocity non-solvent turbulent secondary doping approach. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 10947–10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongthong, J.; Raginov, N.I.; Khabushev, E.M.; Goldt, A.E.; Kondrashov, V.A.; Russakov, D.M.; Shandakov, S.D.; Krasnikov, D.V.; Nasibulin, A.G. Aerosol doping of SWCNT films with p- and n-type dopants for optimizing thermoelectric performance. Carbon 2024, 218, 118670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.F.; Files, B.S.; Arepalli, S.; Ruoff, R.S. Tensile loading of ropes of single wall carbon nanotubes and their mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaempgen, M.; Chan, C.K.; Ma, J.; Cui, Y.; Gruner, G. Printable thin film supercapacitors using single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojny, F.H.; Wichmann, M.H.G.; Fiedler, B.; Kinloch, I.A.; Bauhofer, W.; Windle, A.H.; Schulte, K. Evaluation and identification of electrical and thermal conduction mechanisms in carbon nanotube/epoxy composites. Polymer 2006, 47, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Freestanding bilayers of drop-cast single-walled carbon nanotubes and electropolymerized poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for thermoelectric energy harvesting. Org. Electron. 2020, 76, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, S.; Chiba, T.; Seki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Origin of n type properties in single wall carbon nanotube films with anionic surfactants investigated by experimental and theoretical analyses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Deng, L.; Bilotti, E.; Chen, G. Flexible and foldable films of SWCNT thermoelectric composites and an s-shape thermoelectric generator with a vertical temperature gradient. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5973–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytafides, C.K.; Tzounis, L.; Karalis, G.; Formanek, P.; Paipetis, A.S. High-power all-carbon fully printed and wearable SWCNT-based organic thermoelectric generator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 11151–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimasa, O.; Tamai, R.; Nakayama, H.; Shinozaki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Self-generated temperature gradient under uniform heating in p–i–n junction carbon nanotube thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yuan, H.; Liu, C.; Lan, J.-L.; Yang, X.; Lin, Y.-H. Flexible PANI/SWCNT thermoelectric films with ultrahigh electrical conductivity. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26011–26019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-S.; Choi, S.; Im, S.H. Advances in carbon-based thermoelectric materials for high-performance, flexible thermoelectric device. Carbon Energy 2021, 3, 667–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, B.A.; Staton, N.J.; Gould, I.E.; Wesenberg, D.; Ihly, R.; Owczarczyk, Z.R.; Hurst, K.E.; Fewox, C.S.; Folmar, C.N.; Hughes, K.H.; et al. Large n- and p-type thermoelectric power factors from doped semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotube thin films. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Gao, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. High-performance organic thermoelectric modules based on flexible films of a novel n-type single-walled carbon nanotube. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 14187–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Cai, K.; Du, Y.; Chen, L. Preparation and thermoelectric properties of SWCNT/PEDOT:PSS coated tellurium nanorod composite films. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 778, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yang, S.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Wet-spun PEDOT:PSS/CNT composite fibers for wearable thermoelectric energy harvesting. Compos. Commun. 2022, 32, 101179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Liu, S.; Qiao, F.; Li, P.; He, C. Modulating carrier transport for the enhanced thermoelectric performance of carbon nanotubes/polyaniline composites. Org. Electron. 2019, 69, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Amma, Y.; Takashiri, M. Heat source free water floating carbon nanotube thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Okano, Y.; Amezawa, T.; Kuwahata, H.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. Boosting performance of heat-source free water-floating thermoelectric generators by controlling wettability by mixing single-walled carbon nanotubes with α-cellulose. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonoguchi, Y.; Nakano, M.; Murayama, T.; Hagino, H.; Hama, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Matsubara, R.; Nakamura, M.; Kawai, T. Simple salt-coordinated n-type nanocarbon materials stable in air. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3021–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horike, S.; Wei, Q.; Akaike, K.; Kirihara, K.; Mukaida, M.; Koshiba, Y.; Ishida, K. Bicyclic-ring base doping induces n-type conduction in carbon nanotubes with outstanding thermal stability in air. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, R.; Toshimitsu, F.; Matsumoto, M.; Borah, A.; Staykov, A.; Islam, M.S.; Hayami, S.; Fujigaya, T. Air-stable n-type single-walled carbon nanotubes doped with benzimidazole derivatives for thermoelectric conversion and their air-stable mechanism. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 4703–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, D.; Terasaki, N.; Nonoguchi, Y. Investigation into the stability of chemical doping and the structure of carbon nanotube. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 015318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Amezawa, T.; Okano, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Ochiai, S.; Sunaga, K.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. High thermal durability and thermoelectric performance with ultra-low thermal conductivity in n-type single-walled carbon nanotube films by controlling dopant concentration with cationic surfactant. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 063902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, K.; Futaba, D.N.; Mizuno, K.; Namai, T.; Yumura, M.; Iijima, S. Water-assisted highly efficient synthesis of impurity-free single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 2004, 306, 1362–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Jeong, S.W. Thermoelectric properties of PEDOT: PSS and acid-treated SWCNT composite films. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 23, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Li, B.; Raj, B.T.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Rezeq, M.; Cantwell, W.; Zheng, L. In Situ Surface polymerization of PANI/SWCNT bilayer film: Effective composite for improving Seebeck coefficient and power factor. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2400566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; He, C. Simultaneous enhancement of electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient in organic thermoelectric SWNT/PEDOT:PSS nanocomposites. Carbon 2019, 149, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Sun, S.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, D. Flexible organic thermoelectric composites and devices with enhanced performances through fine-tuning of molecular energy levels. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 4754–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, T.; Cai, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Hai, Y.; Shi, R.; Guo, W. Design and evaluation of an innovative thermoelectric-based dehumidifier for greenhouses. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, V.; Pepin, S.; Gallichand, J.; Caron, J. Reducing cranberry heat stress and midday depression with evaporative cooling. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 198, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J.; Ci, M.; Li, Y.; Fan, X.; Liang, Q.; Li, X. Vapor pressure deficit governs oasis cooling efficiency and drought intensified water-heat tradeoffs in arid regions. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiao, X.; Du, Q.; Song, X.; Li, J. Reducing the excessive evaporative demand improved photosynthesis capacity at low costs of irrigation via regulating water driving force and moderating plant water stress of two tomato cultivars. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 199, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, R.; Verma, H.K.; Uddin, M. Implementation of greenhouse climate control simulator based on dynamic model and vapor pressure deficit controller. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2015, 8, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, N.T.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, J.; Way, A.D.; Sadok, W. Systemic effects of rising atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on plant physiology and productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1704–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Shinozaki, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Ochiai, S.; Nakazawa, Y.; Takashiri, M. SWCNT/PEDOT:PSS/SA composite yarns with high mechanical strength and flexibility via wet spinning for thermoelectric applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S [µV/K] | σ [S/cm] | PF [μW/(m·K2)] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWCNT film | 54.2 | 27.7 | 8.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakazawa, Y.; Takizawa, T.; Nakajima, T.; Uchida, K.; Takashiri, M. Impact of Air Temperature and Humidity on Performance of Heat-Source-Free Water-Floating Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thermoelectric Generators for IoT Sensors. Sensors 2025, 25, 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247445

Nakazawa Y, Takizawa T, Nakajima T, Uchida K, Takashiri M. Impact of Air Temperature and Humidity on Performance of Heat-Source-Free Water-Floating Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thermoelectric Generators for IoT Sensors. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247445

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakazawa, Yuto, Tetsuya Takizawa, Takumi Nakajima, Keisuke Uchida, and Masayuki Takashiri. 2025. "Impact of Air Temperature and Humidity on Performance of Heat-Source-Free Water-Floating Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thermoelectric Generators for IoT Sensors" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247445

APA StyleNakazawa, Y., Takizawa, T., Nakajima, T., Uchida, K., & Takashiri, M. (2025). Impact of Air Temperature and Humidity on Performance of Heat-Source-Free Water-Floating Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thermoelectric Generators for IoT Sensors. Sensors, 25(24), 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247445