1. Introduction

Along with the rapid development of aerospace technologies, to satisfy the need for in-orbit utilization, increasing load size, satellite size, mass, and the structure of satellite tends to be complicated. During the execution of evaluations and quality audits on larger satellites, noise test is required. The mechanical conditions of satellites during launch are relatively stringent, primarily for two reasons. One factor is the force conveyed through the docking interface of the satellite and rocket, including the relatively stable mechanical conditions produced by engine thrust and the transient mechanical conditions resulting from rocket engine ignition, stage separation, etc. The second factor pertains to the mechanical conditions directly affecting the satellite’s surface caused by the noise environment within the fairing, which must be considered in the satellite design process due to its impact on the satellite structure. Considering all of the above factors, it is essential to analyze the response and stress of large satellites subject to acoustic excitation. In previous research, there have been many studies on the response analysis of thin-walled structures subjected to noise excitation. The stress analysis and structural strength verification of satellites subjected to acoustic excitation remain essential in the design of large satellite structures and require particular attention.

Previous investigators have performed comprehensive studies on the response analysis of noise excitation. The prevalent methodologies mostly include finite element analysis (FEA), statistical energy analysis (SEA) [

1], and the FE-SEA hybrid approach. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) models serves as a fundamental methodology in aerospace engineering for structural design and performance optimization. By discretizing complex spacecraft structures into a finite set of elements, this analytical technique employs numerical simulations to predict structural mechanical responses under diverse operational conditions, thereby ensuring design reliability and safety. A systematic model verification strategy consisted of finite element modeling, modal test, correlation analysis, and model updating was proposed [

2]. Li Xiufeng [

3] proposed a method of finite clement model simplification based on topology optimization aiming at the difficult modeling problem of dynamic analysis model caused by complex composition of spacecraft equipment. Finite element analysis offers the benefit of calculating the response at any location inside the structure and obtaining the distribution of that response. Nevertheless, as the frequency of analysis escalates, the increase in grid density and the rise in uncertainty aspects inside the structure will significantly elevate computational costs and reduce analytical accuracy. Consequently, it is inadequate for predicting high-frequency vibration responses. Du Ligang [

4] performed modal analysis of a specific aircraft in a free-free state and conducted random vibration response study under aerodynamic noise utilizing Nastran, thereby validating the efficacy of the finite element model for predicting vibration environments. Li Qing and Xing Likun [

5] employed modal analysis to examine the random vibration response of cabin panels subjected to noise loads, including issues such as damping parameters and the effects of additional mass in the flow field. Cao Maoguo and Li Lin [

6] presented a calculation formula and methodology for the power spectral density of the random vibration acceleration response of thin-walled cylindrical shell structures subjected to noise loads, and derived the calculation formula for the power spectral density and mean square value of the Von Mises stress response, which can be directly applied in fatigue strength analysis; random vibration analysis is primarily employed to evaluate the dynamic response of a spacecraft that is subjected to random base excitation or acoustic excitation. Chen Hua [

7] discussed the fatigue damage analysis of a spacecraft structure under random vibration; Jie Zhang [

8] performed an equivalency study on spacecraft acoustic excitation and random vibration; Dulat Akzhigitov [

9] presents the results of numerical modeling and vibration testing of a nanosatellite’s optical payload, aimed at assessing its mechanical stability under the mechanical impacts of launch. Javier Sanz-Corretge [

10] presents a spectral-based methodology for the probabilistic failure analysis of composite laminates subjected to zero-mean, stationary Gaussian random vibrations. Statistical energy analysis (SEA) promises theoretical advantages in predicting high-frequency vibrational responses. Considering the unpredictability of structural connection methods and manufacturing processes, complex and specific models are not required for the effective computation of statistical average vibration response values [

11,

12,

13,

14]. As a result, a reply and response distribution at defined regions cannot be provided, leading to insufficient computational accuracy in the low to mid frequency range. Wang Dong and Liu Wei [

15] examined the attributes of several dynamic environment prediction techniques, emphasizing the concepts and applications of statistical energy analysis (SEA) methodologies. They confirmed that precise assessment of SEA parameters in a single experiment can more accurately predict dynamic results. Zhang Jin, Zou Yuanjie [

16] employed the FE-SEA hybrid approach to analyze more intricate coupled systems utilizing conventional finite element methods and statistical energy analysis. Zhu Weihong and Han Zengyao [

17] employed the Finite Element Energy Statistical Analysis (FE-SEA) method to develop a spacecraft acoustic vibration prediction model, subsequently comparing it with experimental data to validate the efficacy of the prediction approach. Peng Wang [

18] analyzed vibration and reliability analysis of non-uniform composite beam under random load; Jesús M. [

19] allowed us to determine the fatigue life of a component that is being subjected to a random vibration environment. Koki SATO [

20] proposed a new modal analysis method and evaluated its effectiveness compared to acoustic results from experiments. Dong, F [

21] analyzed the fatigue life of honeycomb sandwich panels and conducted experiments.

Currently, most of the large satellite structures employ composite materials, particularly honeycomb panels. Specialized methods are necessary for stress analysis of the satellite’s structure in this configuration, owing to the absence of relevant elements in finite element software. The primary application technique is the equivalent method [

22]; Xu Shengjin and Kong Xianren [

23] indicated an equivalent approach for orthotropic honeycomb sandwich panels based on low-order shear theory, validating its accuracy by experimental verification. He Rui [

24] posited that aluminum honeycomb sandwich panels demonstrate a nonlinear frequency response function in random vibration tests, characterized by a reduction in FRF amplitude and an elevation in damping ratio as the excitation intensity increases, aligning with the nonlinear damping model; Laurent Wahl [

25] analyzed shear stresses in honeycomb sandwich plates, some equations are derived in order to calculate the real shear stresses from the shear stresses of the homogeneous core. Zhao Jingjing [

26] presents the intrinsic nature of an adhesively bonded multi-layer structure which increases the risk of debonding when the honeycomb sandwich structure is under strain or exposed to varying temperatures. Wang Mo-Nan [

27] focuses on the in-plane shear respond and failure mode of large size honeycomb sandwich composites which consist of plain weave carbon fabric laminate skins and aramid paper core. Alaa Al-Fatlawi [

28] investigated replacing the currently used aluminum base plates of aircraft pallets with composite sandwich plates to reduce the weight of the pallets, thereby the weight of the unit loads transported by aircraft. Qi, D.Z [

29] analyzed the buckling loads of a composite sandwich structure, which was reinforced by a honeycomb layer and filled with viscoelastic damping material, Fei-Hao Li [

30] established a three-dimensional vibration theory for ultralight cellular-cored sandwich plates subjected to linearly varying in-plane distributed loads; Zhuo Xu [

31] introduced a nonlinear damping prediction model for partially filled composite honeycomb sandwich panels and formulated a structural energy equation by integrating high-order shear theory with finite element analysis, thereby offering a more precise computational approach for examining the nonlinear damping properties of honeycomb sandwich structures. Sadiq Emad Sadiq [

32] presents a suggested analytical solution for a forced vibration of an aircraft sandwich plate with a honeycomb core under transient load.

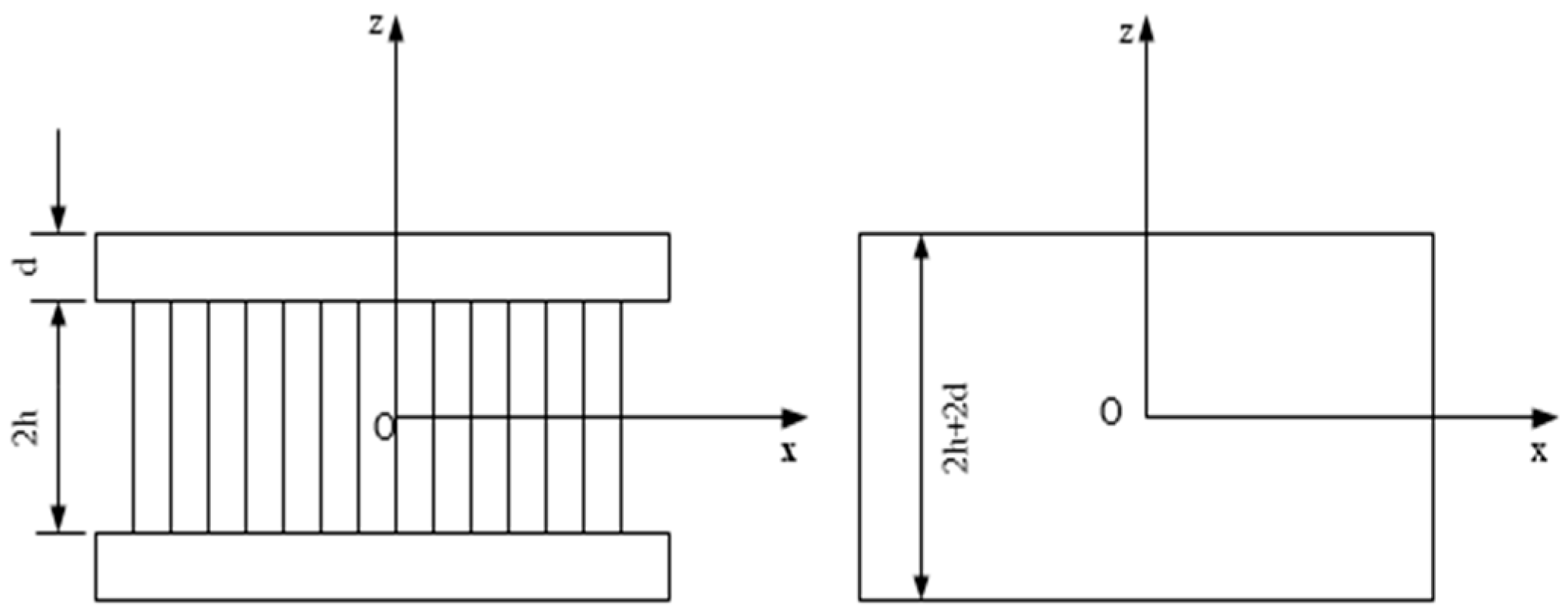

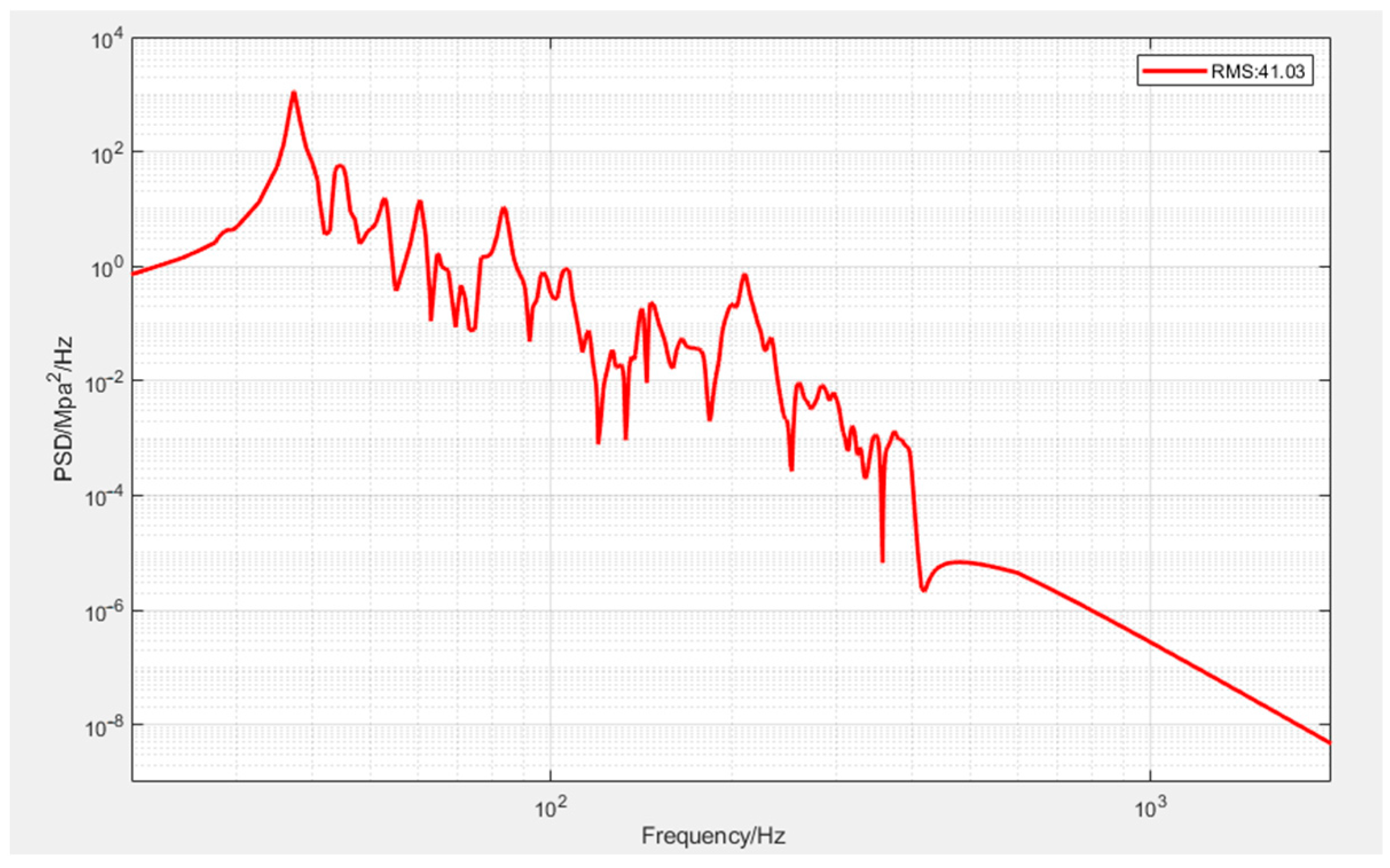

Based on a previous study, this article develops a finite element model of a large satellite with honeycomb sandwich panels that are equivalent to orthotropic shear plates of identical stiffness and sizes, and calculated the elastic modulus, shear modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and equivalent density of the mechanical model, providing parameters for stress calculation. This article abandons the traditional method of noise excitation analysis, transforms the sound pressure spectrum into pressure power spectral density, converts noise excitation into random excitation, and implements it on the surface of the satellite finite element model. In previous analyses, the damping ratio for frequency response analysis was generally taken as a constant value of 0.03, and in order to obtain a more accurate analysis, a variable damping model was adopted, analyzing the vibration response and stress subjected to acoustic excitation, conducting satellite noise testing, and then comparing it with noise test results to validate the efficacy of the predictive method.

5. Conclusions

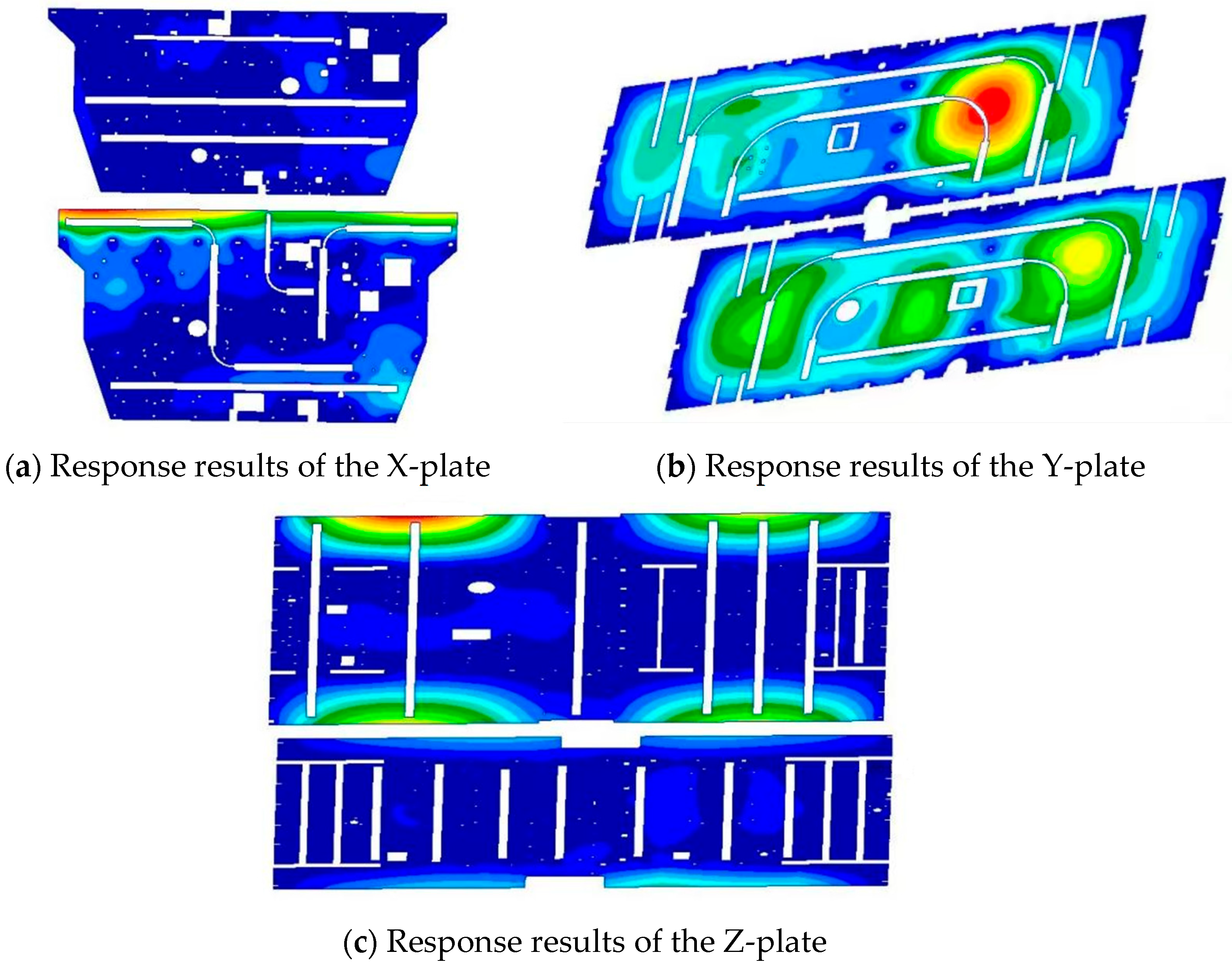

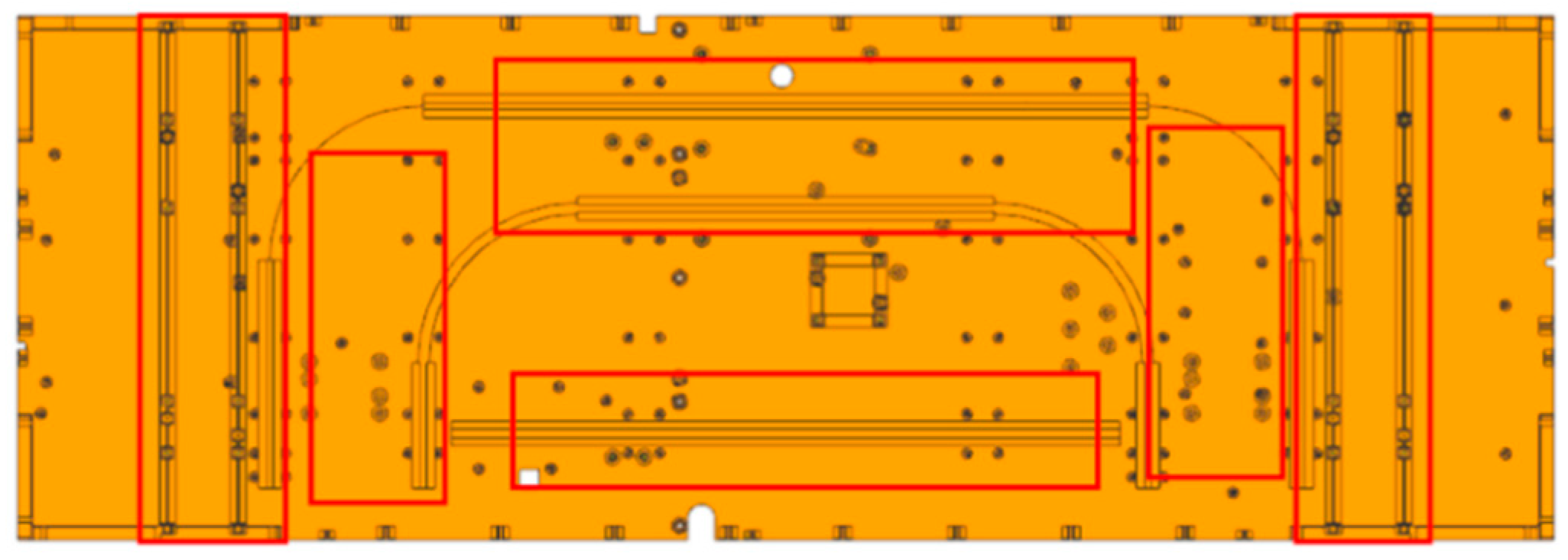

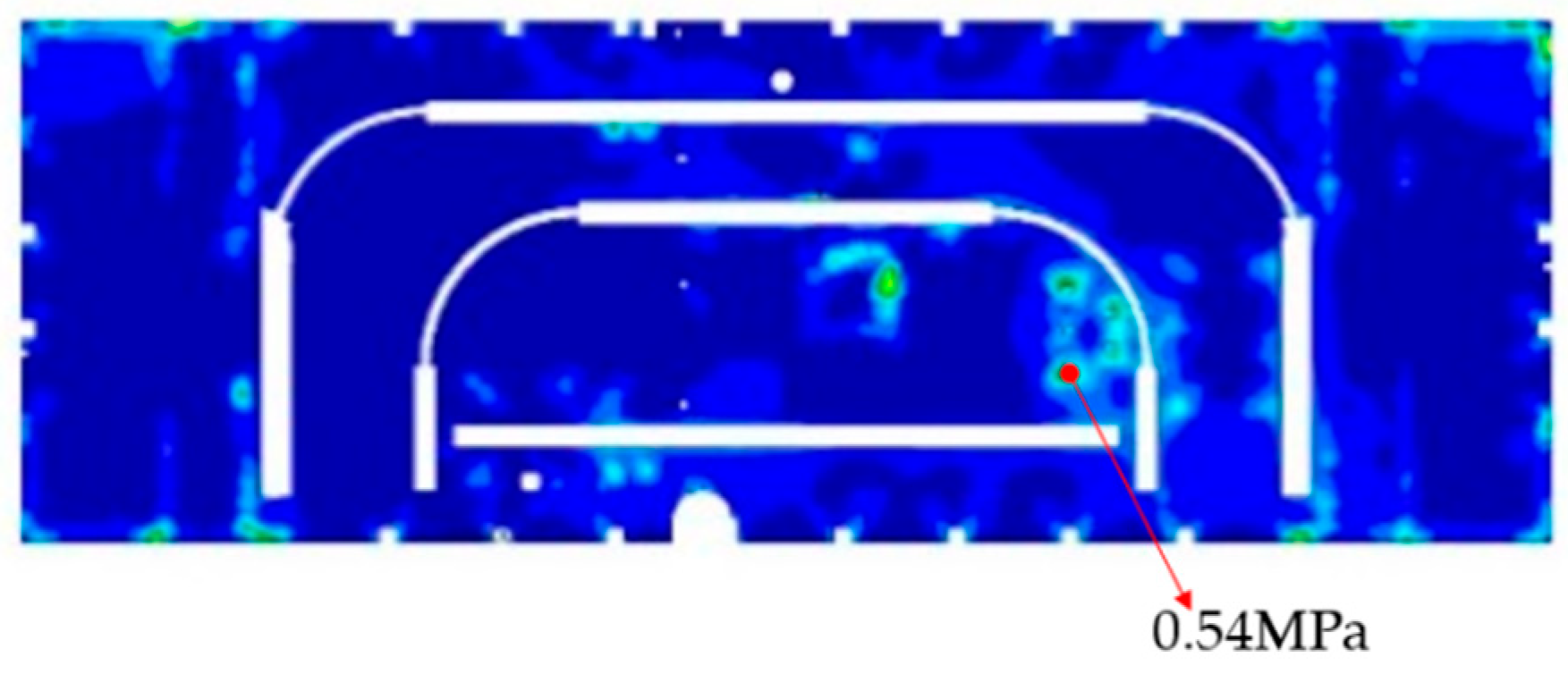

This paper develops a finite element analysis model for the vibration of satellite structures subjected to acoustic excitation. Equivalent calculations were conducted on the honeycomb sandwich panel construction to determine its response and stress, transform acoustic excitation into random pressure exerted on the satellite’s flat surface, and studied the impact of damping parameters on simulation results. In reaction to the phenomenon of damage to the honeycomb panel structure during noise testing of a satellite, the vibration response results under noise excitation were analyzed comparatively. The damping model employed in this research demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for response results compared to the traditional constant damping model, with a maximum error of 0.61 g. Upon checking the stress of the honeycomb sandwich panel, it was determined that the maximum stress at the site of the honeycomb core failure was 0.45 MPa, exceeding the stress limit of the sparse honeycomb core, hence identifying the reason of the honeycomb panel damage. According to simulation results, the honeycomb panel was locally modified to a dense honeycomb structure, and its maximum stress subsequently satisfied the design specifications. Noise testing was conducted once more, ensuring that the difference between the stress result and the simulation results of the skin at the site of honeycomb collapse is less than 10%, and the maximum difference between the noise test response results and the simulation results is 0.58 g, verifying the feasibility and accuracy of the satellite stress and response analysis simulation method subjected to acoustic excitation in this article, the simulation indicates that the maximum shear stress of the honeycomb core is 0.54 MPa, far less than the stress limit of the dense honeycomb, which solves the issue of honeycomb collapse. Simultaneously, employing a dense honeycomb structure locally can guarantee the satellite’s safe operation in orbit.

The paper establishes a finite element simulation model using an equivalent honeycomb model and empirical damping model, transforming the sound pressure spectrum into pressure power spectral density, converting noise excitation into random excitation, and implementing it on the surface of the satellite finite element model. A variable damping model instead of fixed value damping is adopted; the response and stress results subjected to noise excitation are analyzed and tested.

This analytical method serves as a reference for subsequent research. The simulation method proposed in this work enables a dynamic analysis of a large spacecraft and space stations during rocket launch phases. Our forthcoming work will prioritize the following aspects: composite material applications, variable damping research, and nonlinear dynamic response analysis, the integration of machine learning for faster parameter optimization or coupling with high-fidelity commercial solvers.