Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Power Distribution Analytics Based on IoT

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose the PSDA scheme to address the challenges of power distribution analysis in smart grids. Our control solution is based on an IoT system, supporting efficient monitoring and analysis of power distribution.

- We apply Hilbert curve-based encoding to efficiently manage IoT devices, optimizing the processing and representation of spatial regions. Furthermore, we incorporate DPF techniques to guarantee the privacy and security of the power distribution data. This combination of advanced encoding and privacy-preserving techniques enhances the accuracy and security of the distribution analysis while addressing privacy concerns in smart grid applications.

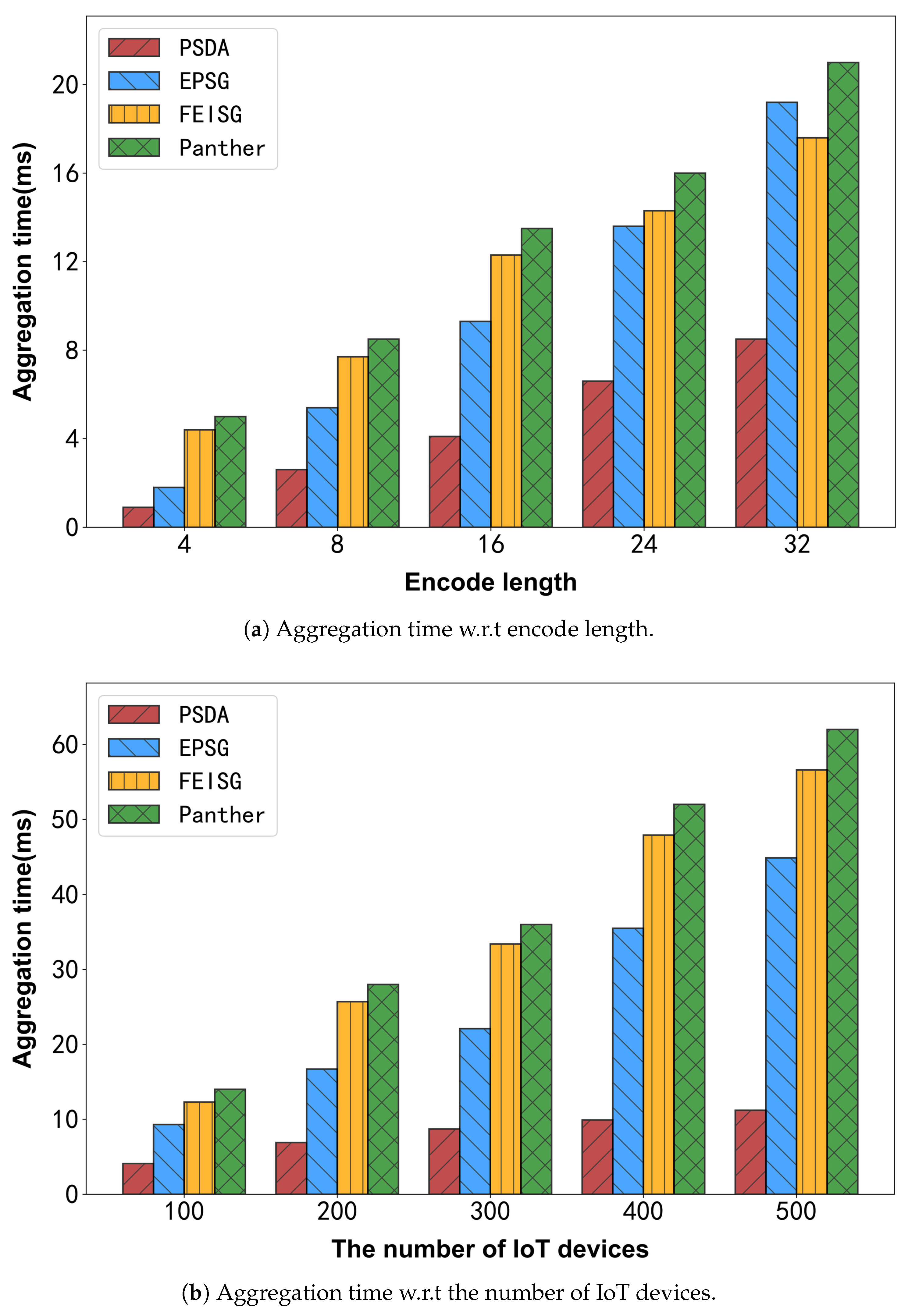

- The experimental results substantiate the superior effectiveness of the proposed method, demonstrating consistent performance improvements over existing approaches. The results indicate that PSDA achieves superior performance in both computational efficiency and communication overhead, offering a robust solution for analyzing power distribution in contemporary power systems.

2. Related Work

3. Materials

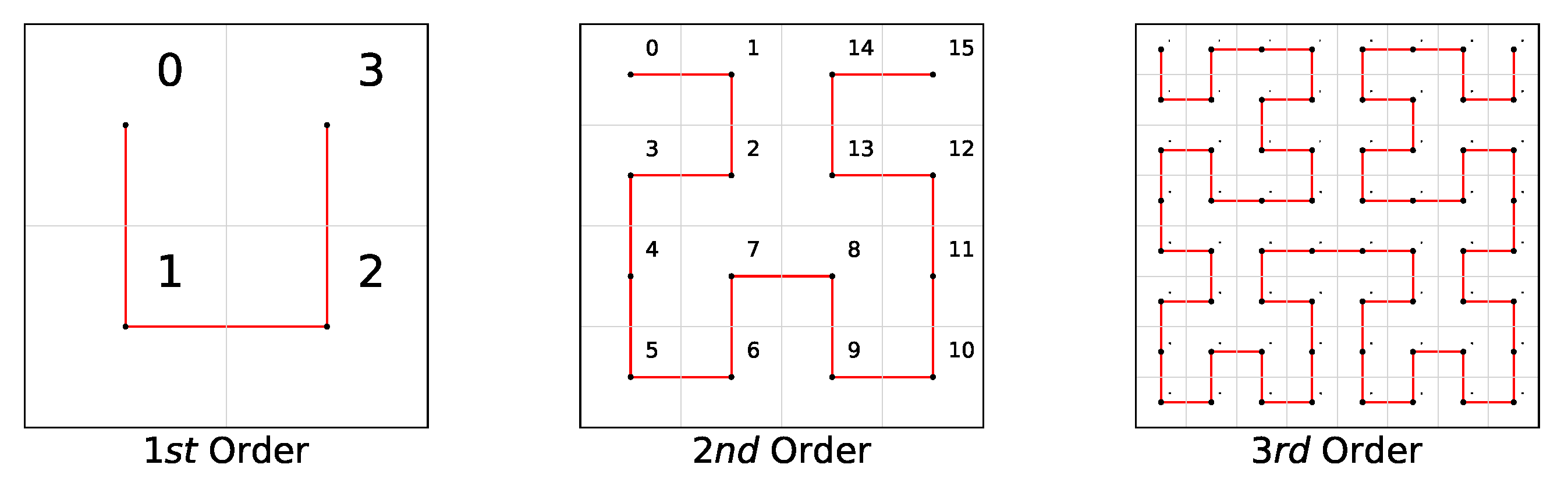

3.1. Hilbert Curve

- Recursive partitioning: the current region is divided into four subregions, forming an arrangement similar to the letter “E”.

- Transformation of the subregions:

- Apply a 90° counterclockwise rotation to the first subregion (lower left).

- The second subregion (upper left) remains unchanged.

- The third subregion (upper right part) remains unchanged.

- Apply a clockwise rotation of 90° to the fourth subregion (lower right part).

- By constant recursion, higher-order Hilbert curves are generated, and these transformations refine the curves.

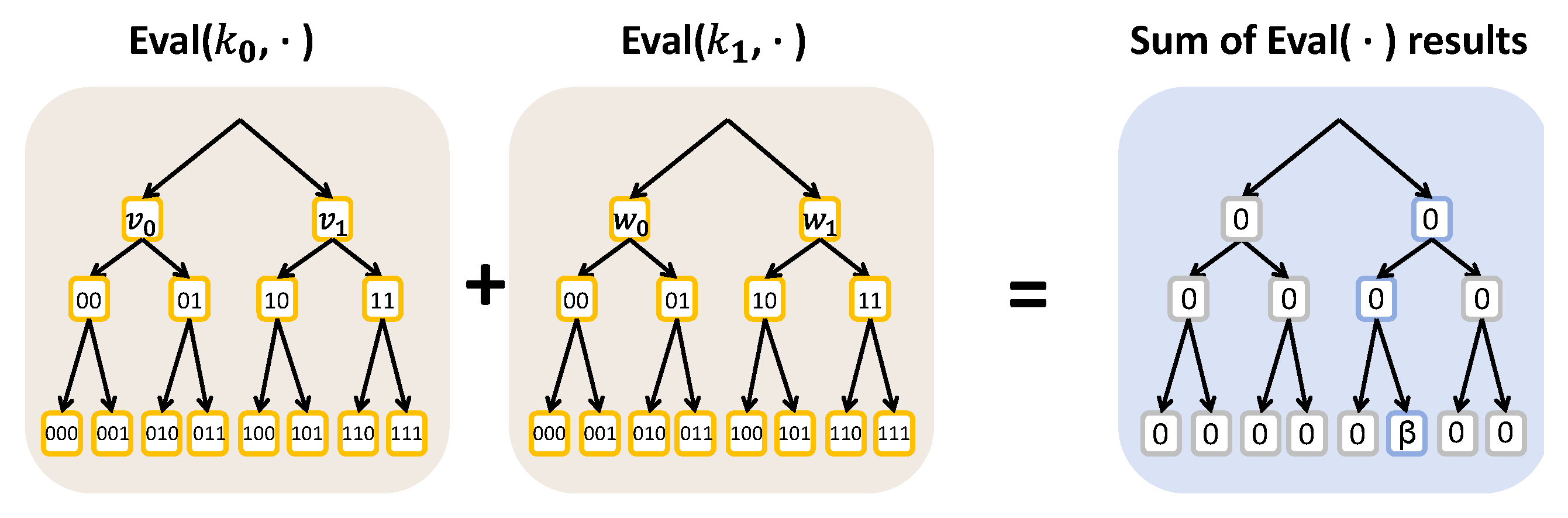

3.2. Distributed Point Functions

- Gen () → (). Given the security parameter , an index , and a value , the algorithm produces a pair of DPF keys. Conceptually, the two keys jointly encode a -dimensional vector over whose -th entry equals while all other entries are zero.

- Eval () →. Given as the party identifier, as the corresponding key and as an input, the algorithm outputs the i-th share of the vector entry at position x. The correctness property of a two-party DPF, given () ←Gen(), is formalized as

4. Models and Goals

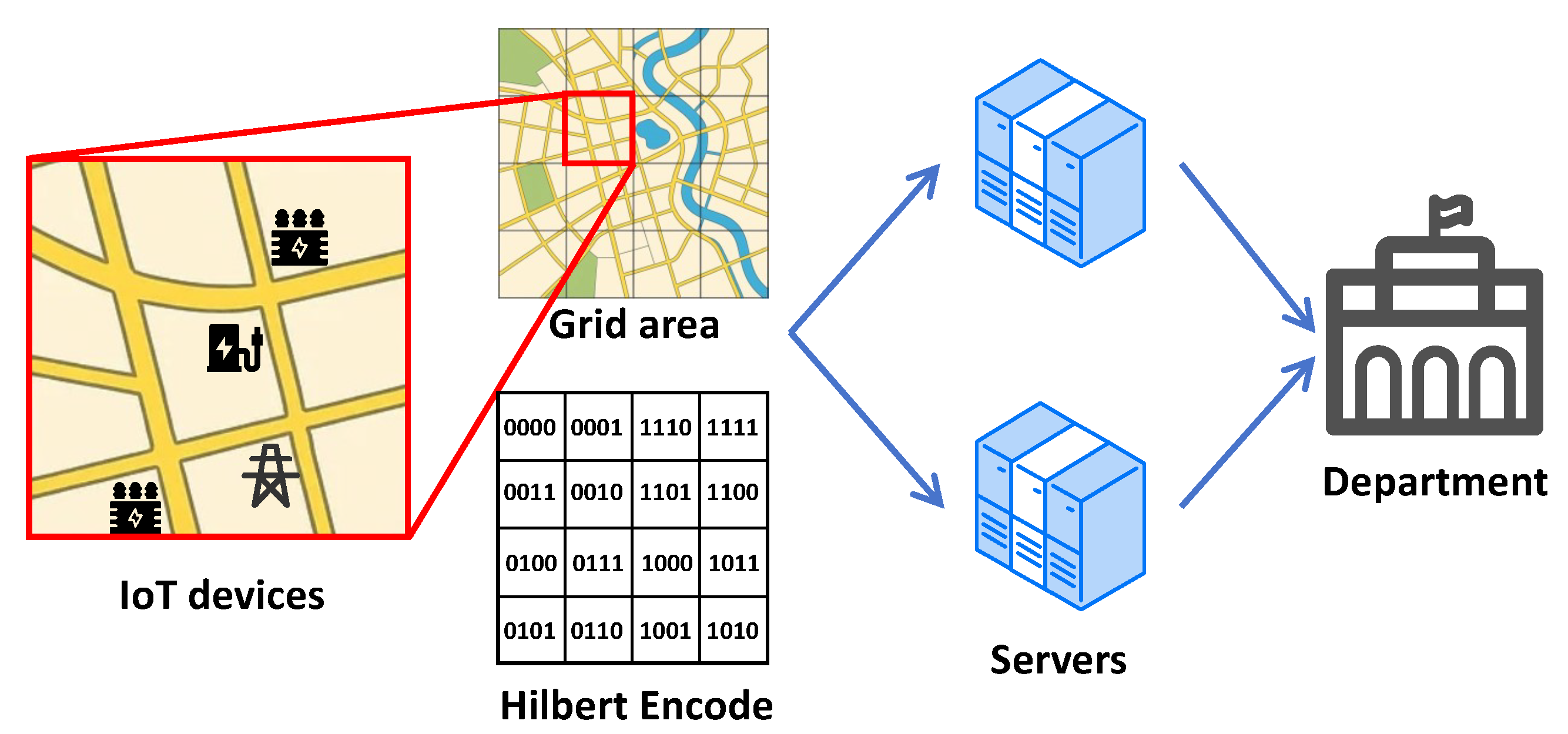

4.1. Models

- IoT devices: The first entity consists of IoT devices widely distributed across the power grid. These devices integrate sensing and communication modules, enabling the continuous acquisition of local electrical data such as voltage, current, and load fluctuations. The collected data is pre-processed locally on the IoT device and encrypted using DPF based on the Hilbert curve encoding. The Hilbert code is mapped from the real geographic location of IoT devices. The encrypted data is then transmitted to the collaborative servers for further analysis. This allows accurate identification of areas where distribution anomalies or imbalances may exist.

- Two Collaborative Servers: The two servers work together to process the encoded data received from the IoT devices. These servers handle data processing and ensure secure transmission of results to the electricity management department. They guarantee that data is processed and transmitted securely, preserving its integrity throughout the entire procedure.

- Electricity Management Department: This entity is responsible for overseeing the operation and stability of the power grid. Once the servers provide the processed data on power distribution across the grid, the electricity management department uses this information to monitor grid performance and optimize resource allocation to ensure effective grid management. The department’s main objective is to ensure the uninterrupted and efficient functioning of the grid while maintaining stable energy distribution.

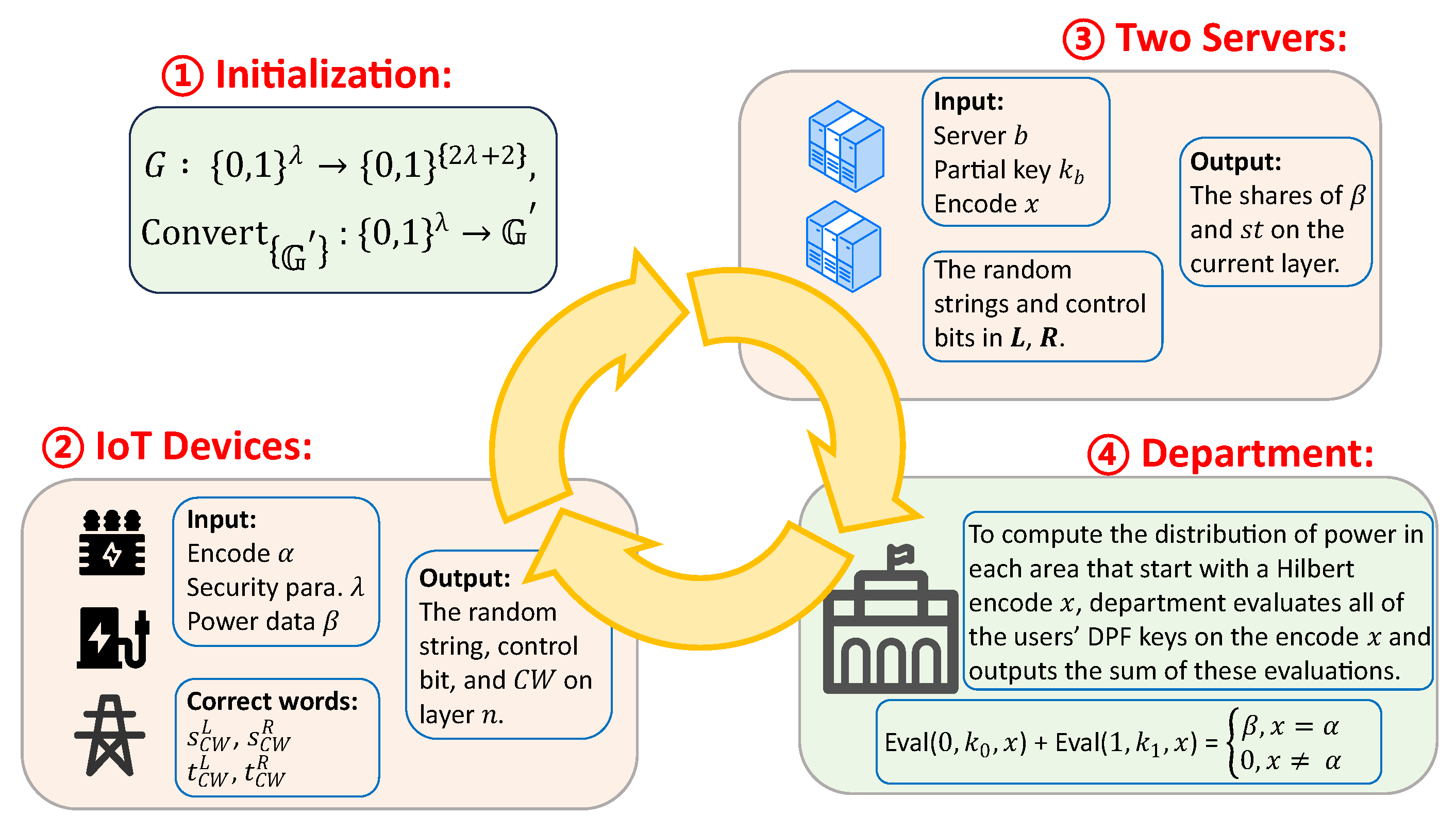

4.2. Workflow

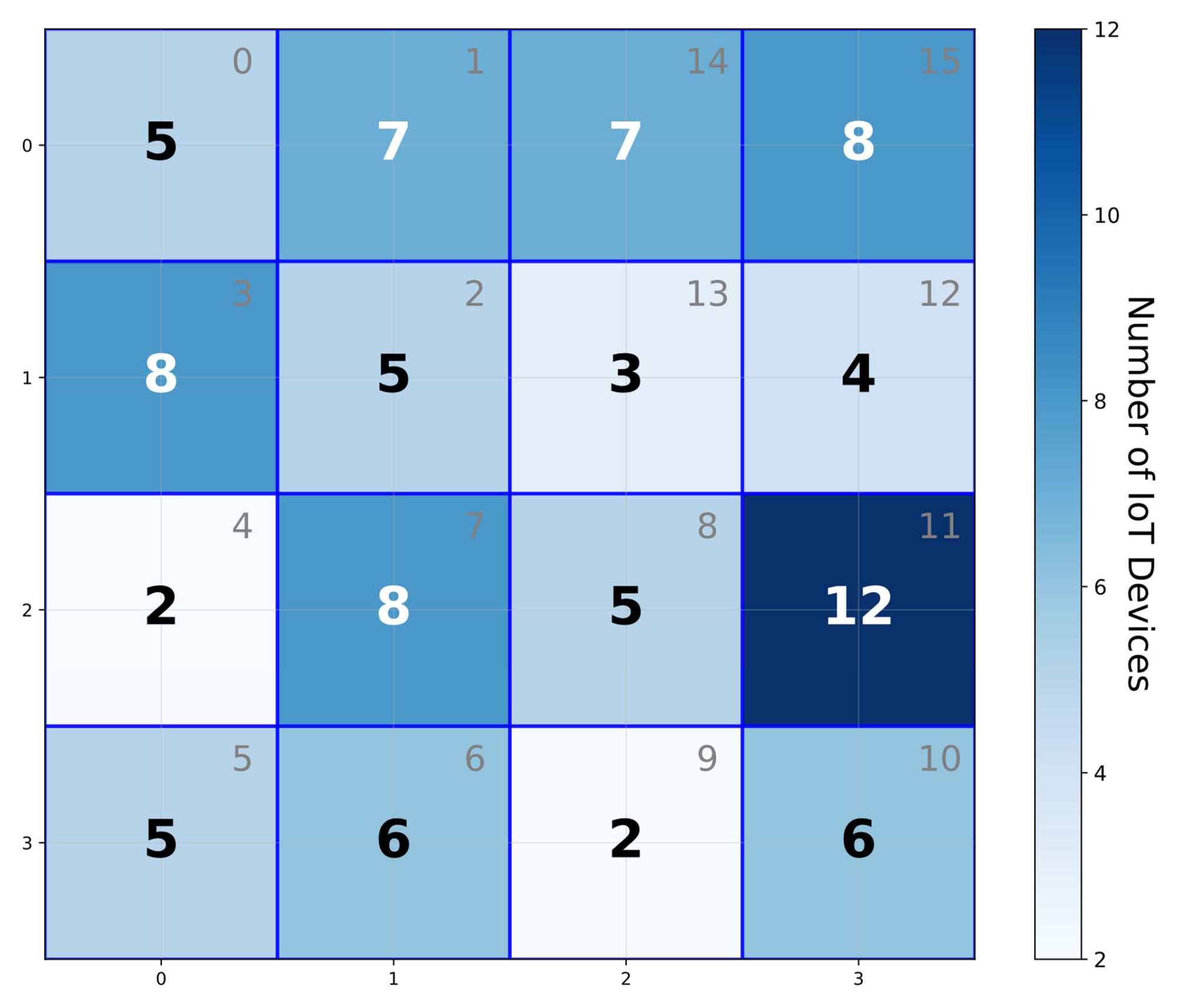

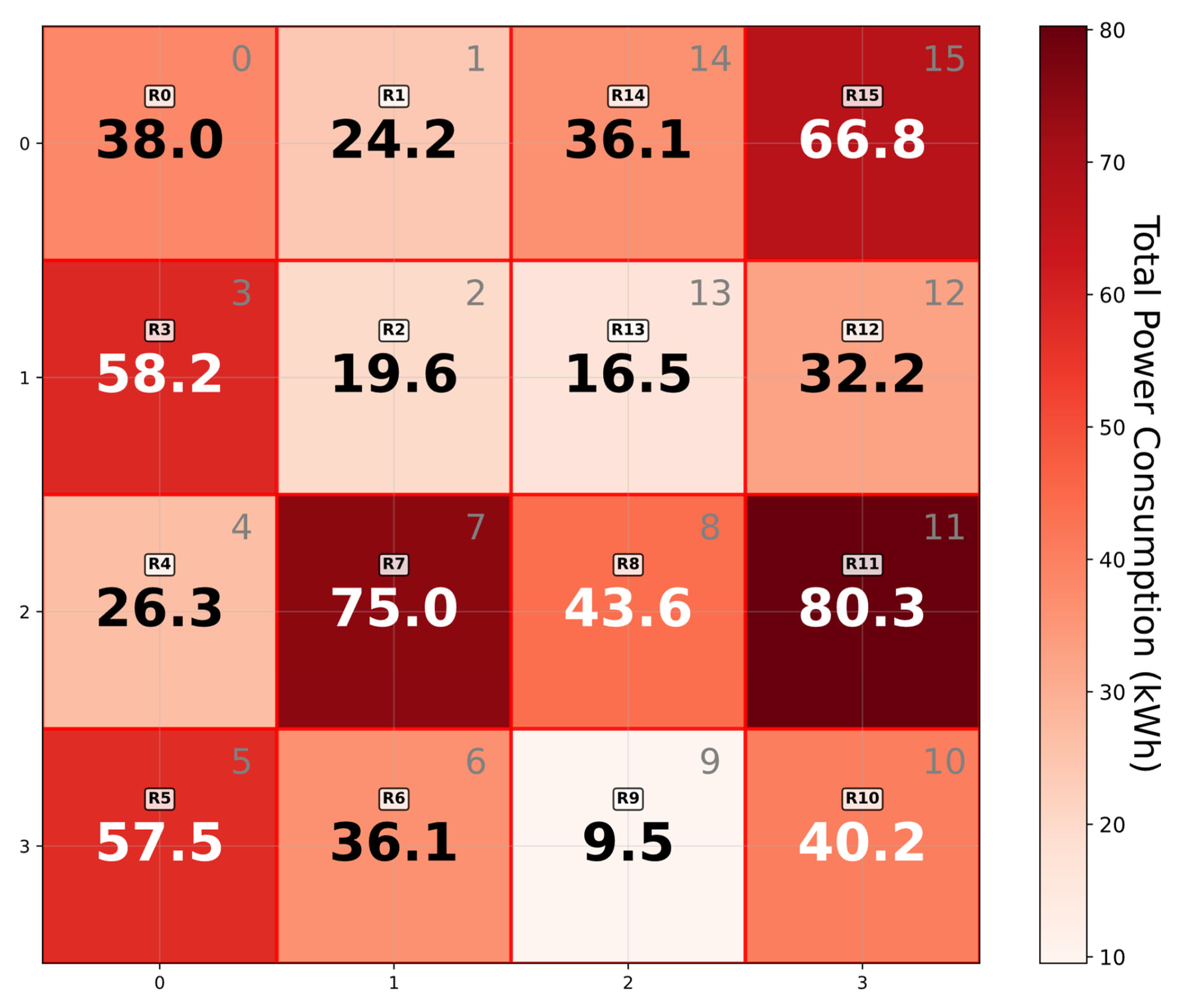

- Data Collection and Encoding: IoT devices—such as electric vehicle charging stations, smart meters, and distribution transformer monitors—are deployed across different regions of the grid to collect electrical data. These devices continuously monitor local conditions, capturing parameters like voltage and current. To enable efficient spatial analysis, the geographical area is first partitioned into smaller, manageable regions. The data from each region is then encoded using a Hilbert curve, a technique that effectively captures spatial relationships within the grid. This encoding method facilitates more accurate and scalable analysis of distribution patterns.

- Secure Transmission: Once the data is encoded, the IoT devices use DPF to generate a shared secret key for secure data transmission. The DPF ensures that the information related to fault-prone areas is encrypted and protected during transmission. The encoded data, along with the corresponding DPF shares, is securely transmitted to the two collaborative servers.

- Data Processing: The two collaborative servers receive the encrypted data and the shared keys. They work together to process the information and identify fault-prone regions based on the data provided. The servers perform the necessary computations while adhering to the security and privacy requirements set by the DPF mechanism.

- Action by the Electricity Management Department: The department analyzes the data to identify areas of the grid requiring optimization or adjustment, such as regions exhibiting imbalances or inefficiencies. After identifying such regions, the electricity management department takes the necessary actions to optimize the power distribution. This could include adjusting load distribution, deploying resources, or making other decisions to ensure the grid remains stable and efficient.

5. Methodology

5.1. Encoding

| Algorithm 1 Generating Binary Encoding for the Hilbert Curve |

|

5.2. Key Generation

| Algorithm 2 Init |

|

5.3. Data Processing

| Algorithm 3 Gen |

|

| Algorithm 4 Eval (b, , x) |

|

5.4. Security Analysis

- IoT devices: Each IoT device is assumed to be semi-honest. That is, the device follows the prescribed protocol to generate and transmit its encoded data correctly but may attempt to infer additional information from the messages it handles. Devices do not collude with other devices or with the servers. In practice, a subset of devices may behave maliciously. A malicious IoT device may tamper with its reported data, thereby influencing the overall power analysis results. The primary objective of our work, however, is to assist the electricity management department in promptly detecting such anomalous data and conducting further investigation and verification. Therefore, the security analysis in this paper does not consider scenarios in which IoT devices behave maliciously.

- Two non-colluding servers: The two servers and are assumed to be semi-honest. They faithfully follow the protocol execution but may attempt to learn private information from their locally stored shares. The fundamental assumption is that these servers are non-colluding, typically operated by the electricity management department or government. If collusion occurs, the DPF-based privacy guarantee no longer holds.

- Electricity management department: The management department is regarded as an honest party that aggregates the computation results received from both servers. It is trusted to perform the aggregation correctly.

- Multi-device adversary: This adversary compromises an arbitrary subset of IoT devices, obtaining access to their local measurements, encryption keys, and DPF shares. The compromised devices may collude with each other and attempt to infer information about other uncompromised IoT devices or the servers.

- Single-server adversary: This adversary corrupts one of the two non-colluding servers (either or ), gaining full access to its stored data, computation states, and received DPF shares. The adversary may attempt to infer the private information of IoT devices or the internal data of the another server.

6. Results

6.1. Implementation and Settings

6.2. Metrics and Baselines

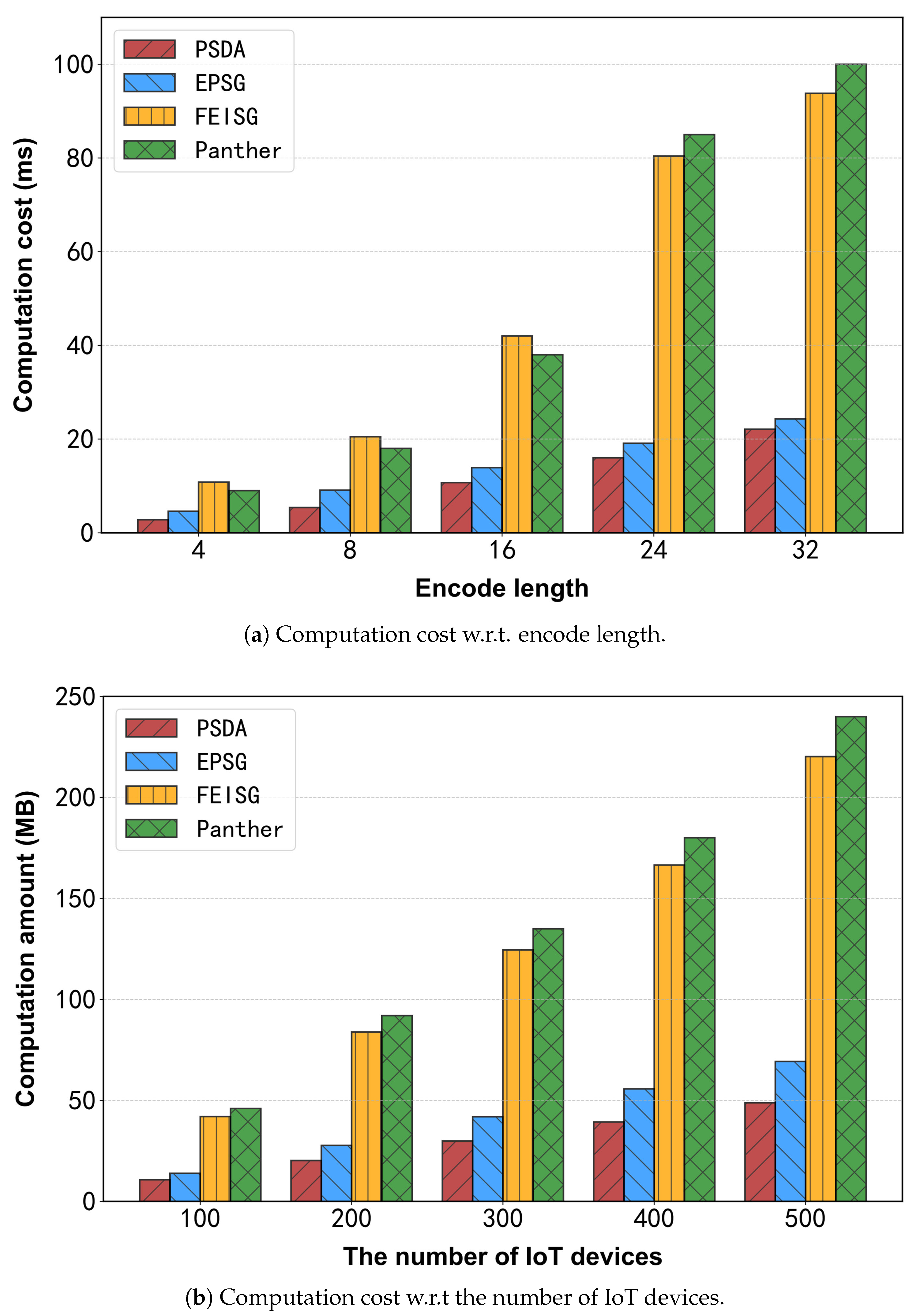

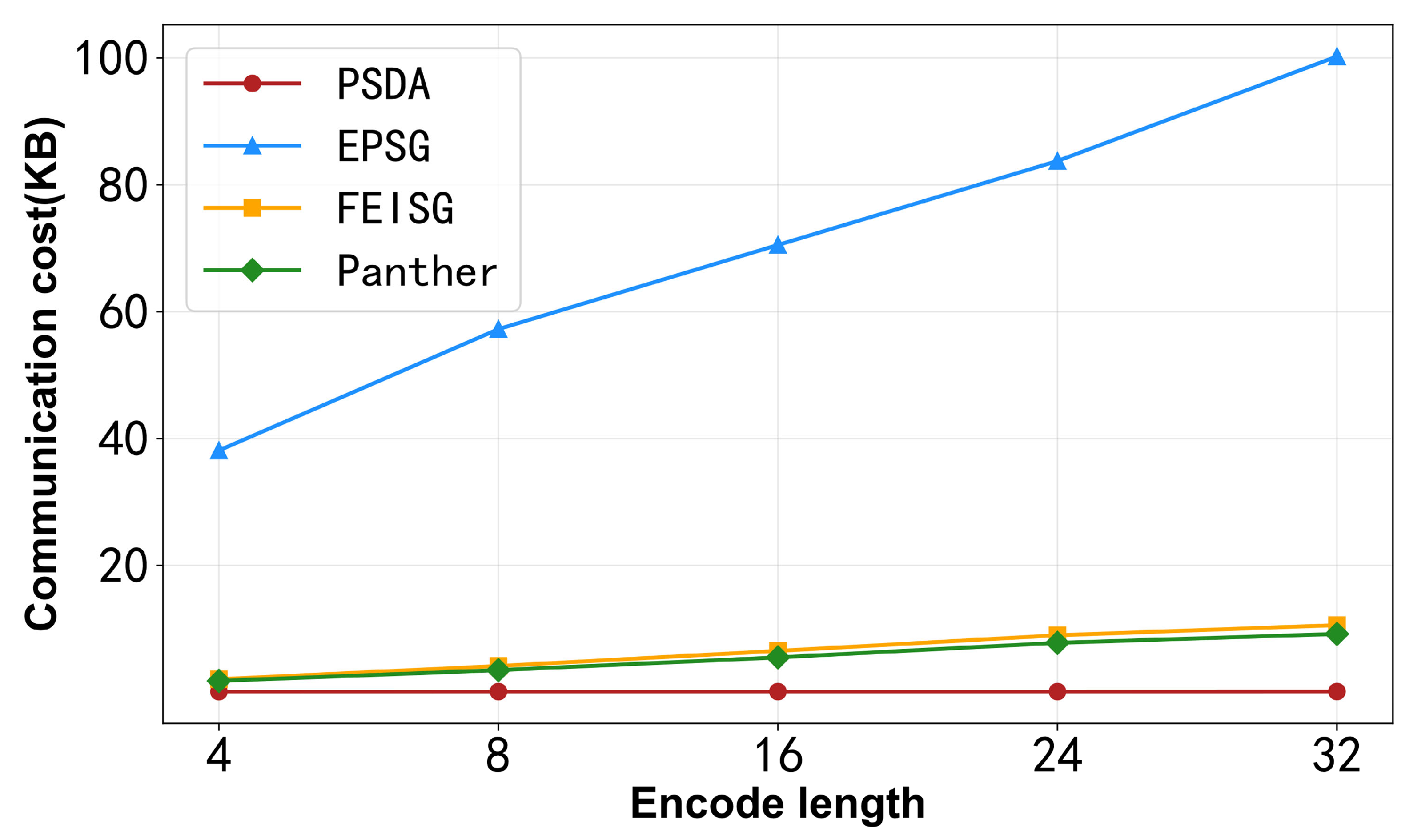

- Shruti_FEISG [20]: This paper proposed an encryption-based data consolidation strategy for smart grids leveraging fog computing [25,26], which shifts part of the cloud’s computation and storage tasks to fog nodes located near smart meters. By enabling local data compression and consolidation, the approach reduces transmission costs and improves efficiency while maintaining data security. Data is first processed and compressed at smart meters, and then it is aggregated at fog devices before being selectively uploaded to the cloud. Though this protects privacy and uses fog nodes to reduce the cost of communication with the server, it incurs significant computational cost.

- Rostampour_EPSG [21]: This paper proposed a lightweight authentication scheme for smart grids that leverages the unique physical characteristics of devices to ensure the integrity and authenticity of smart meters. By preventing cloning and tampering at the device level, the scheme establishes a secure foundation for grid communication. It provides strong protection against common attacks. While it offers robust privacy protection, it does incur certain computational and communication costs.

- Feng_Panther [27]: This paper proposed Panther, a practical secure two-party neural network (2P-NN) inference system that enables clients to obtain inference results from a server-hosted deep neural network without revealing their inputs, while the server’s model parameters remain private. The system combines a customized homomorphic encryption scheme for efficient linear-layer computation with an optimized millionaires’ protocol based on oblivious transfer and secret sharing for nonlinear functions such as ReLU and max-pooling. By reducing polynomial multiplications and communication rounds, Panther significantly decreases both computation and communication overhead. While it achieves state-of-the-art efficiency compared with prior works, it still uses homomorphic encryption as a privacy protection technique, which causes significant computational and communication overhead.

- PSDA refers to the efficient and privacy-preserving spatial distribution statistics scheme introduced in Section 5.

6.3. Performance Evaluation

6.3.1. Computation Costs on Uploading

6.3.2. Communication Costs upon Uploading

6.3.3. Aggregation Time

6.3.4. Experimental Summary

7. Discussion

7.1. Scalability in Dynamic and Large-Scale Smart Grids

7.2. Detection and Localization in Smart Grid

7.3. Function Secret Sharing Applications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kataray, T.; Nitesh, B.; Yarram, B.; Sinha, S.; Cuce, E.; Shaik, S.; Vigneshwaran, P.; Roy, A. Integration of smart grid with renewable energy sources: Opportunities and challenges—A comprehensive review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 58, 103363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Teng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, P.; Sun, M.; Deng, R.; Cheng, P.; Chen, J. Enhancing cyber-resiliency of der-based smart grid: A survey. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 4998–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Shahidehpour, M.; Yang, T.; Zeng, Z.; Chai, T. Deep reinforcement learning for smart grid operations: Algorithms, applications, and prospects. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 1055–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, S.; Ghafouri, M.; Au, M.; Kassouf, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Debbabi, M. Security of wide-area monitoring, protection, and control (WAMPAC) systems of the smart grid: A survey on challenges and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1294–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Rehman, A.U.; Wang, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Luo, P.; Elkadeem, M.R.; Abido, M.A. IoT-based monitoring and control of substations and smart grids with renewables and electric vehicles integration. Energy 2023, 282, 128924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Pengwah, A.B.; Razzaghi, R.; Andrew, L.L. An improved algorithm for topology identification of distribution networks using smart meter data and its application for fault detection. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 3850–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, D.; Cheng, J. A deep learning approach for electromechanical impedance based concrete structural damage quantification using two-dimensional convolutional neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straßer, A.; Adam, A.; Li, J. In operando detection of Lithium plating via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for automotive batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 580, 233366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etingov, D.; Zhang, P.; Shamash, Y.A. IoT-Enabled Traveling Wave Microgrid Protection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 9169–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Muguira, L.; Jiménez, J.; Lázaro, J.; Yong, W. High performance platform to detect faults in the Smart Grid by Artificial Intelligence inference. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 15, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeeq, M.A.; Zeebaree, S.R. Design and implementation of an energy management system based on distributed IoT. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 109, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, M.A. An IOT based smart grid system for advanced cooperative transmission and communication. Phys. Commun. 2023, 58, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Xiao, M.; Lai, J.; Elkadeem, M.R. Advanced energy management strategy for microgrid using real-time monitoring interface. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.A.; López, J.C.; Guzman, C.P.; Arias, N.B.; Rider, M.J.; da Silva, L.C. An IoT-based energy management system for AC microgrids with grid and security constraints. Appl. Energy 2023, 337, 120904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C. A comprehensive overview of framework for developing sustainable energy internet: From things-based energy network to services-based management system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, N.; Xue, K.; Zhu, B.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; He, D. An efficient data aggregation scheme with local differential privacy in smart grid. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Xie, R.; Lu, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K. FedDetect: A novel privacy-preserving federated learning framework for energy theft detection in smart grid. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 6069–6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, M.B.; Santos, S.F.; AlSkaif, T.; Javadi, M.S.; Castro, R.; Catalão, J.P. Preserving privacy of smart meter data in a smart grid environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, L. BESA: Boosting Encoder Stealing Attack with Perturbation Recovery. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 10007–10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Shabaz, M.; Dutta, A.K.; Ahmed, E.A. Enhancing privacy and security in IoT-based smart grid system using encryption-based fog computing. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 102, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rostampour, S.; Bagheri, N.; Ghavami, B.; Bendavid, Y.; Kumari, S.; Martin, H.; Camara, C. Using a privacy-enhanced authentication process to secure IoT-based smart grid infrastructures. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 1668–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liang, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Guo, S. Epass: Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Asynchronous Payment on Blockchain. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.09387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ren, X.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Li, C.; Zhu, L. Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning for Data Heterogeneity in 6G Mobile Networks. IEEE Netw. 2025, 39, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.; Gilboa, N.; Ishai, Y. Function secret sharing: Improvements and extensions. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 1292–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.; Inuwa, M.M. A review on fog computing: Issues, characteristics, challenges, and potential applications. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2023, 10, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometov, A.; Molua, O.L.; Komarov, M.; Nurmi, J. A survey of security in cloud, edge, and fog computing. Sensors 2022, 22, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, D. Panther: Practical secure 2-party neural network inference. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodin, D.; Smolnikar, M.; Rudež, U.; Čampa, A. Precise PMU-based localization and classification of short-circuit faults in power distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 3262–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Gupta, S.; Yadav, A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y. Traveling wave-based fault localization in FACTS-compensated transmission line via signal decomposition techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapountzoglou, N.; Raison, B.; Silva, N. Fault detection and localization in LV smart grids. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Milan PowerTech, Milan, Italy, 23–27 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, W.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L. Research on distributed power distribution fault detection based on edge computing. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 24643–24652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Mehmood, M.; Ulasyar, A.; Khattak, A.; Imran, K.; Sheh Zad, H.; Nisar, S. Cloud based IoT solution for fault detection and localization in power distribution systems. Energies 2020, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamuya, Y.D.; Lee, Y.D.; Shen, J.W.; Shafiullah, M.; Kuo, C.C. Application of machine learning for fault classification and location in a radial distribution grid. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, H.; Yunhao, Z.; Shiming, T.; Yang, Y.; Wenhai, Y. Fault point detection of IOT using multi-spectral image fusion based on deep learning. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 64, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhe, F.G.Y.; Boum, A.T.; Ele, P.; Mbey, C.F.; Kakeu, V.J.F. Fault detection, classification and location in power distribution smart grid using smart meters data. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2022, 26, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Najafzadeh, M.; Pouladi, J.; Daghigh, A.; Beiza, J.; Abedinzade, T. Fault detection, classification and localization along the power grid line using optimized machine learning algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Adhikari, S.; Datta, S.; Devi, K.J.; Devi, A.D.; Alsaif, F.; Alsulamy, S.; Ustun, T.S. Deep learning based relay for online fault detection, classification, and fault location in a grid-connected microgrid. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 62674–62696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, N.N. Fault Identification, Classification, and Location on Transmission Lines Using Combined Machine Learning Methods. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2022, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.; Gilboa, N.; Ishai, Y. Function secret sharing. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Sofia, Bulgaria, 26–30 April 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 337–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jawalkar, N.; Gupta, K.; Basu, A.; Chandran, N.; Gupta, D.; Sharma, R. Orca: FSS-based secure training and inference with GPUs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2024; pp. 597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Dauterman, E.; Rathee, M.; Popa, R.A.; Stoica, I. Waldo: A private time-series database from function secret sharing. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2022; pp. 2450–2468. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, R.; Xu, J.; Ren, X.; Deng, H. Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Power Distribution Analytics Based on IoT. Sensors 2025, 25, 6677. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216677

Xu R, Xu J, Ren X, Deng H. Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Power Distribution Analytics Based on IoT. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6677. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216677

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ruichen, Jiayi Xu, Xuhao Ren, and Haotian Deng. 2025. "Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Power Distribution Analytics Based on IoT" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6677. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216677

APA StyleXu, R., Xu, J., Ren, X., & Deng, H. (2025). Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Power Distribution Analytics Based on IoT. Sensors, 25(21), 6677. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216677