Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Composition of Defatted Flour

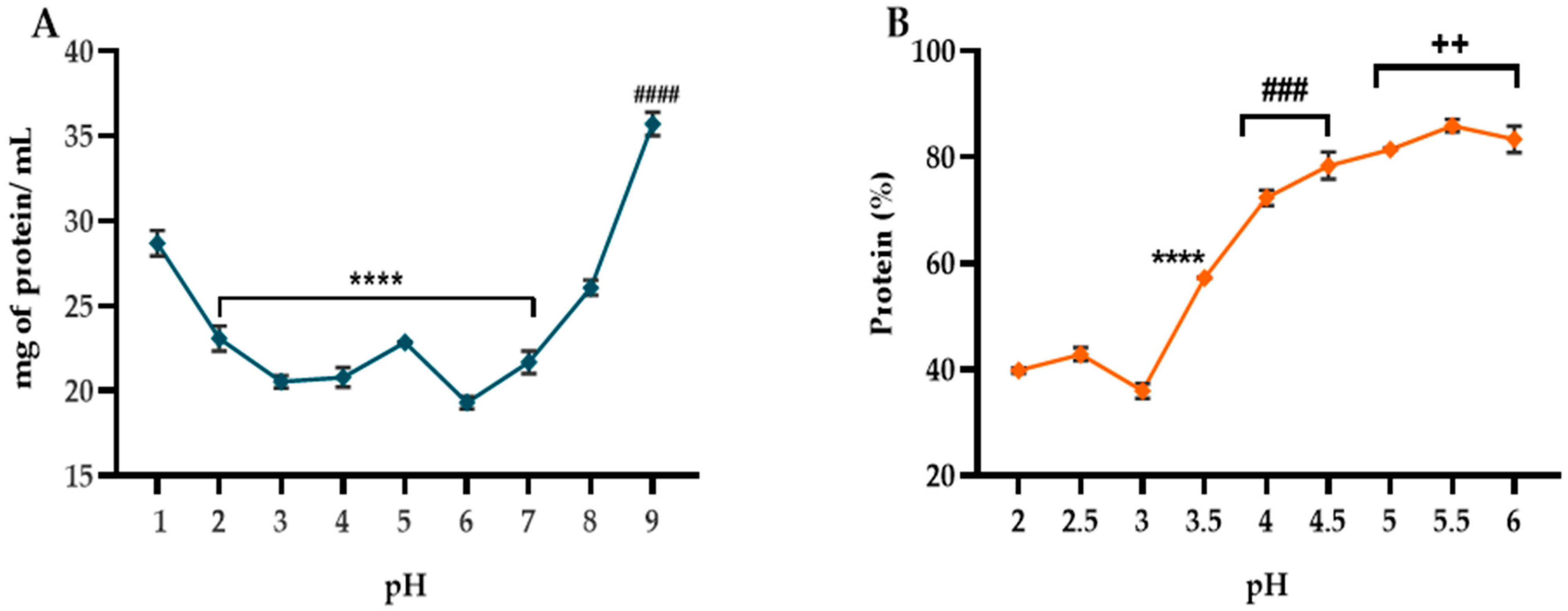

2.2. Determination of Protein Isolation Conditions

2.3. Evaluation of the Degree of Hydrolysis and the Amino Acid Profile

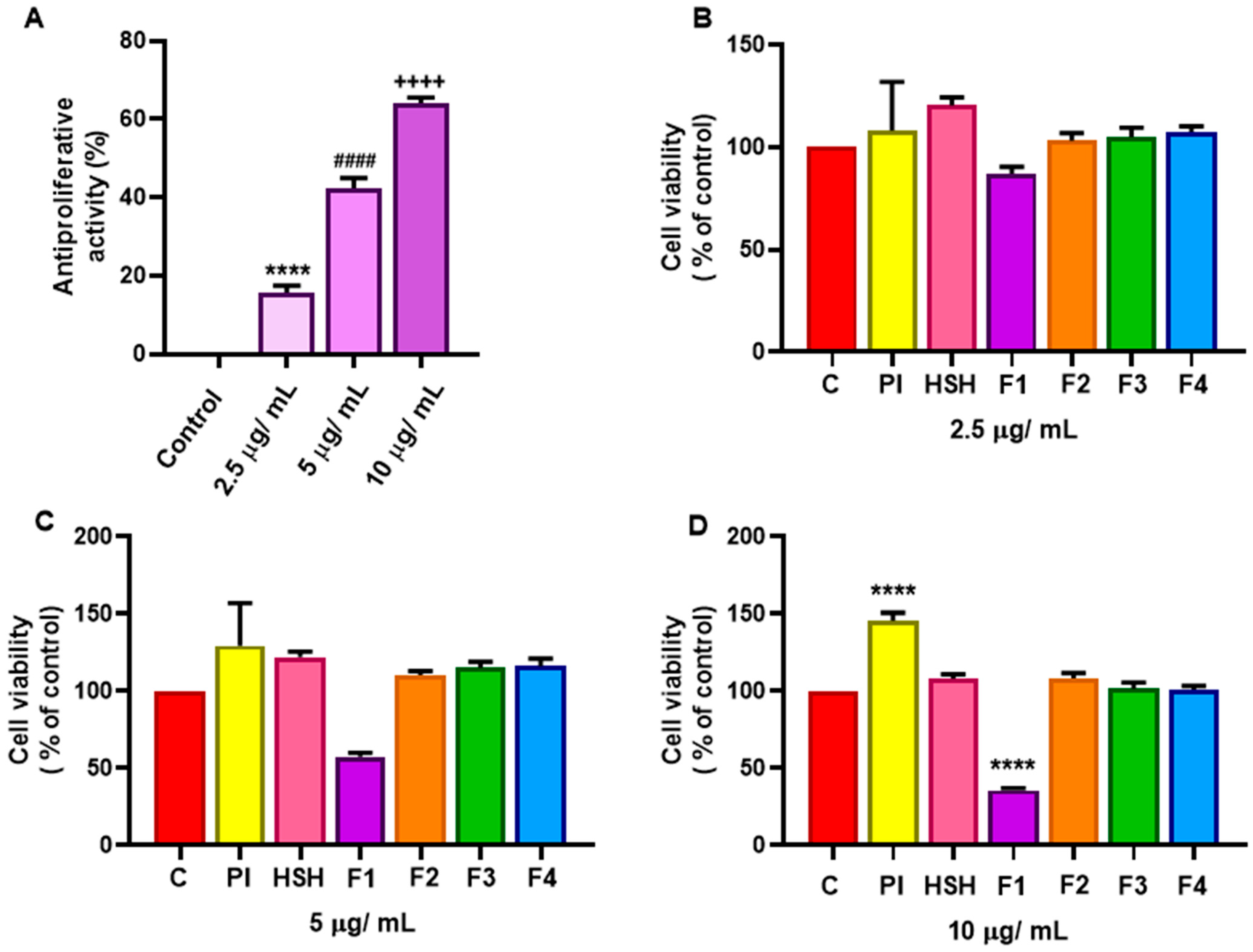

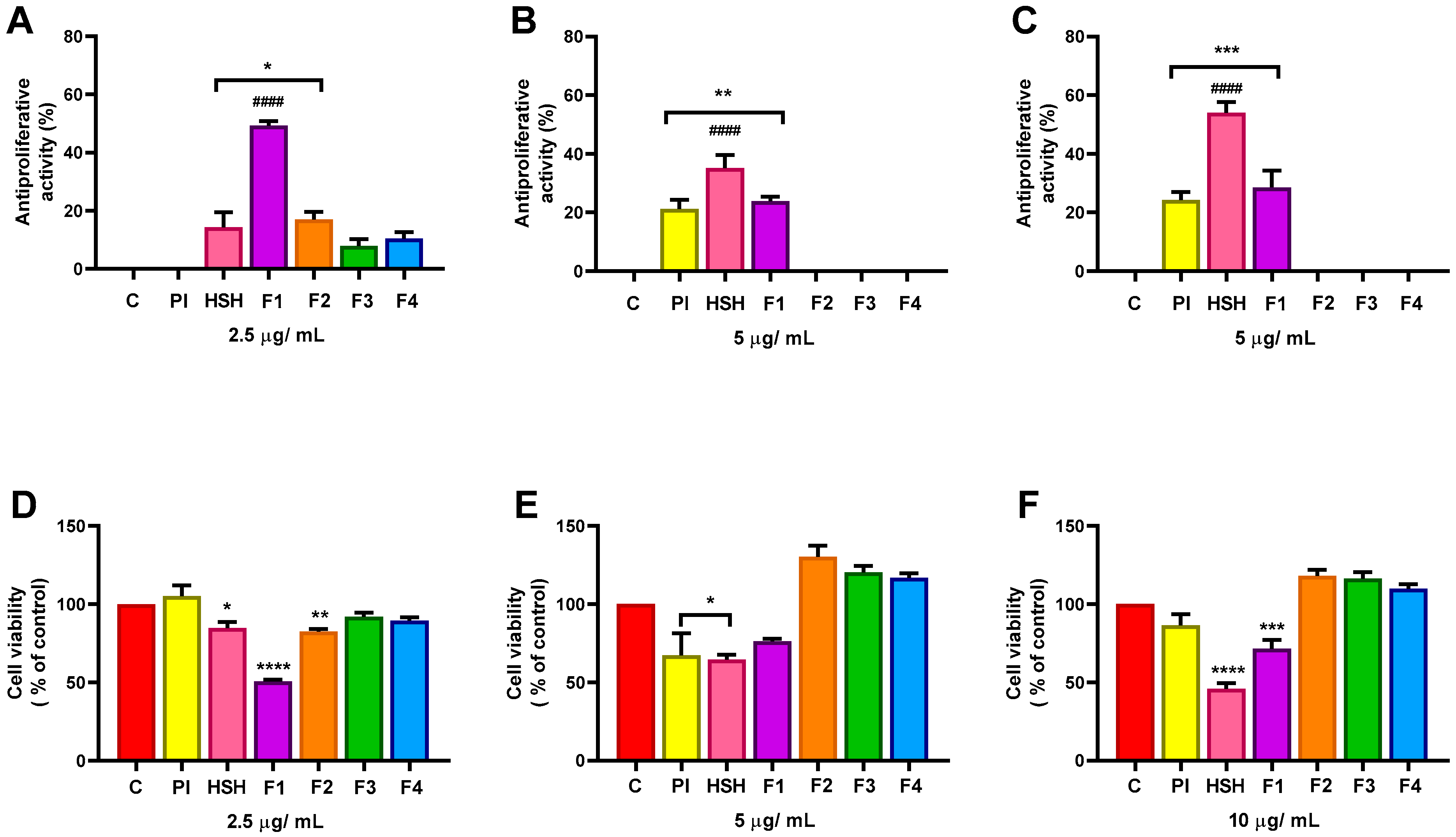

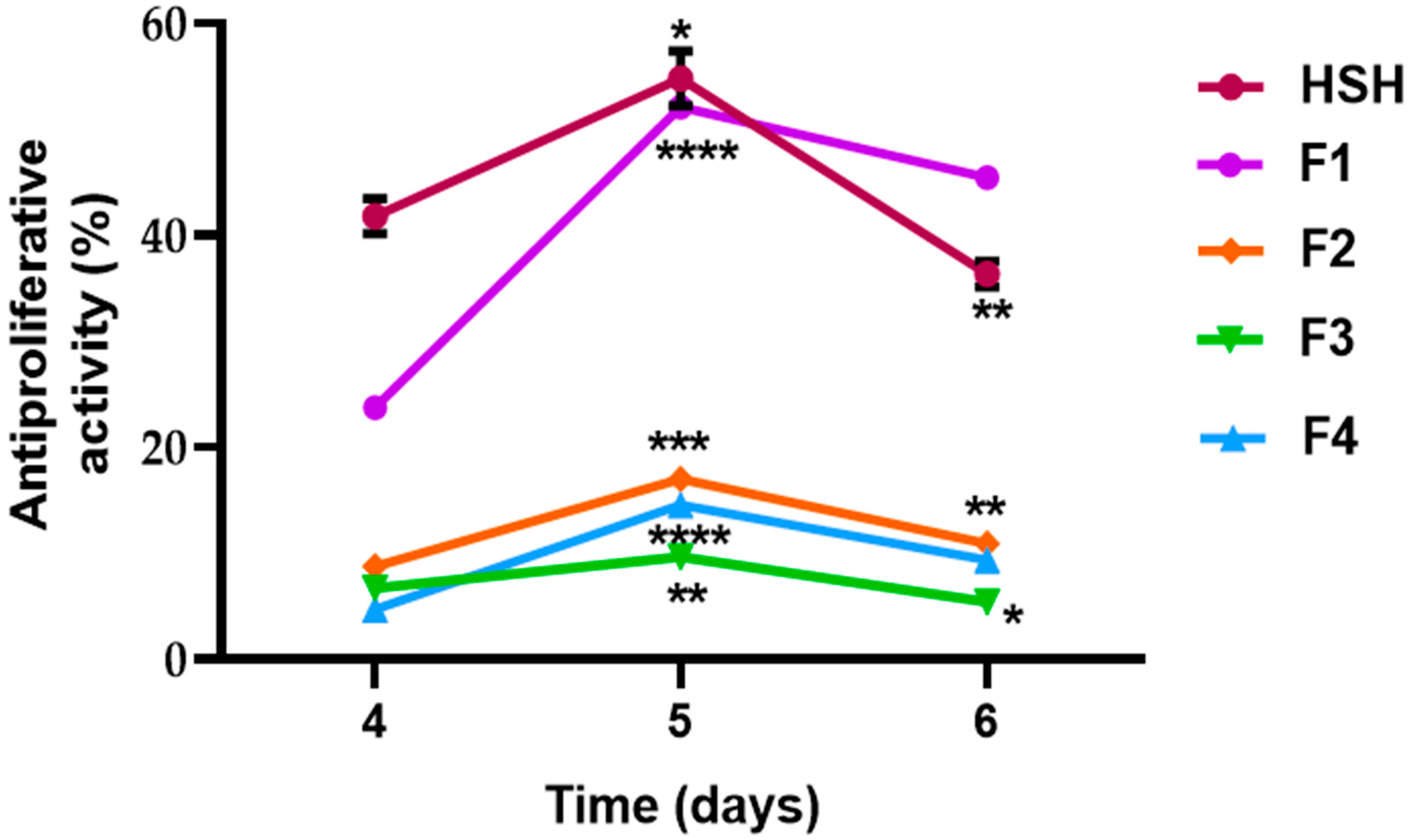

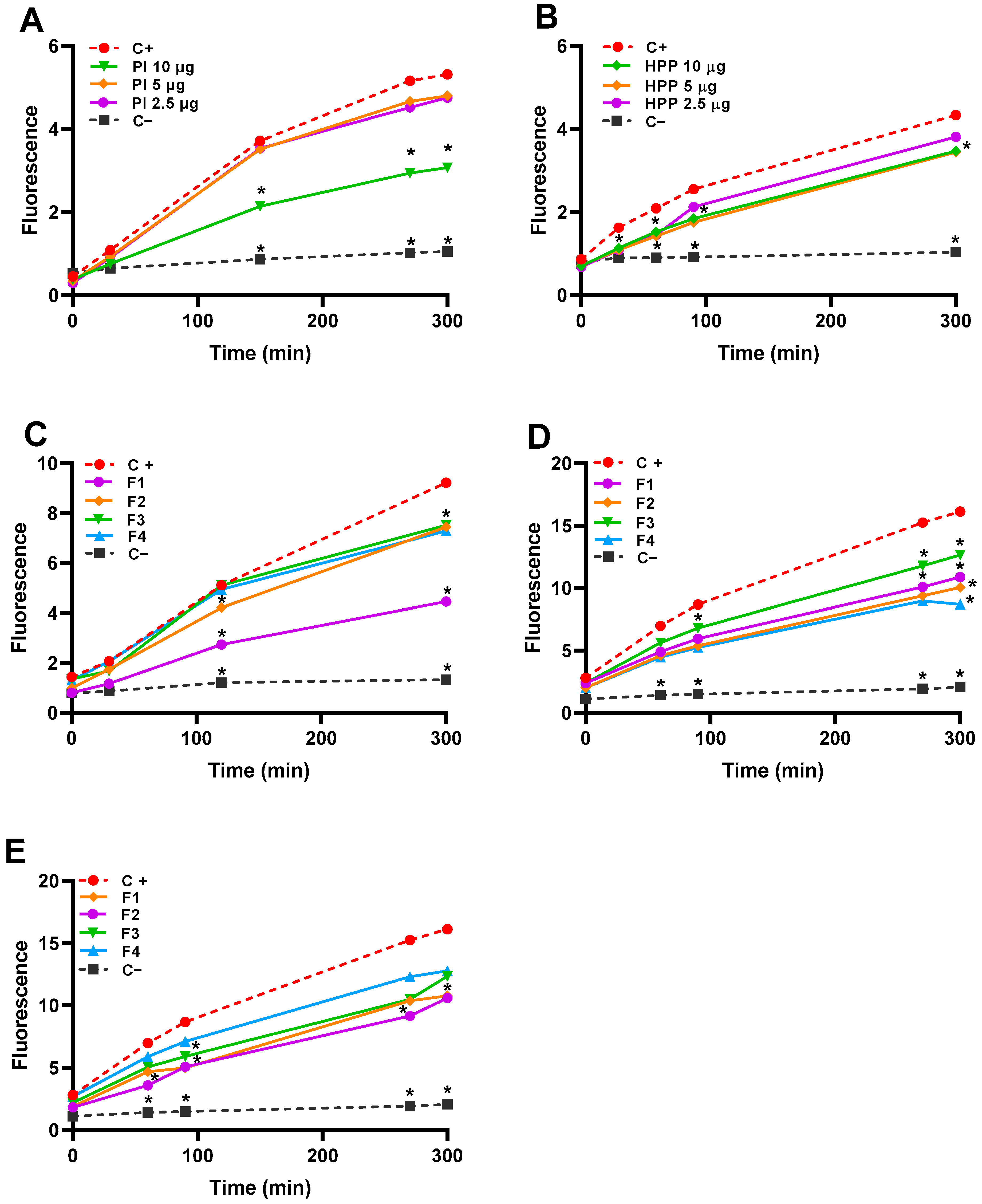

2.4. Antiproliferative Effect of PI, HSH, and Fractions

2.5. Effect on Antioxidant Capacity in the Caco-2 Cell Line

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Biological Materials and Reactive

3.2. Obtention of the Hemp Defatted Flour

3.3. Preparation of Hemp Seed Protein Isolate (PI)

3.4. Hydrolysis of Hemp Seed Protein Isolate

3.5. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH)

3.6. Fractionation of the Hydrolysate by Membrane Ultrafiltration

3.7. Amino Acid Composition Analysis

3.8. Cell Culture

3.9. Proliferative Activity Assay in Caco-2 Cell Line

3.10. Proliferative Activity Assay in THP-1 Cell Line

3.11. Antioxidant Activity Assay in Caco-2 Cell Line

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McPartland, J.M.; Guy, G.W.; Hegman, W. Cannabis is indigenous to Europe and cultivation began during the Copper or Bronze age: A probabilistic synthesis of fossil pollen studies. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2018, 27, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawler, J.; Stout, J.M.; Gardner, K.M.; Hudson, D.; Vidmar, J.; Butler, L.; Page, J.E.; Myles, S. The genetic structure of marijuana and hemp. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinon, B.; Molinari, R.; Costantini, L.; Merendino, N. The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional quality and potential functionality for human health and nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomah, B.D. Hempseed: A functional food source. In Molecular Mechanisms of Functional Food; Campos-Vega, R., Oomah, B.D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 269–356. [Google Scholar]

- Chelliah, R.; Wei, S.; Daliri, E.B.M.; Elahi, F.; Yeon, S.J.; Tyagi, A.; Liu, S.; Madar, I.H.; Sultan, G.; Oh, D.H. The role of bioactive peptides in diabetes and obesity. Foods 2021, 10, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Lao, F.; Pan, X.; Wu, J. Food Protein-Derived Antioxidant Peptides: Molecular Mechanism, Stability and Bioavailability. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, T.B.; He, T.P.; Li, H.B.; Tang, H.W.; Xia, E.Q. The structure-activity relationship of the antioxidant peptides from natural proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Sánchez, G.; Álvarez-López, A.I.; Ponce-España, E.; Carrillo-Vico, A.; Bollati, C.; Bartolomei, M.; Lammi, C.; Cruz-Chamorro, I. Hempseed (Cannabis sativa) protein hydrolysates: A valuable source of bioactive peptides with pleiotropic health-promoting effects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgih, A.T.; Udenigwe, C.C.; Aluko, R.T. In vitro antioxidant properties of hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) protein hydrolysate fractions. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martin, N.M.; Toscano, R.; Villanueva, A.; Pedroche, J.; Millan, F.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Millan-Linares, M.C. Neuroprotective protein hydrolysates from hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6732–6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgih, A.T.; Alashi, A.; He, R.; Malomo, S.; Aluko, R.E. Preventive and treatment effects of a hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) meal protein hydrolysate against high blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Failla, M.L. Intestinal cell models for investigating the uptake, metabolism and absorption of dietary nutrients and bioactive compounds. Curr. Opin. Food. Sci. 2021, 41, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Huang, T.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Huang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Liang, M. Optimization of differentiation and transcriptomic profile of THP-1 cells into macrophage by PMA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Yamabe, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Konno, T.; Tada, K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer 1980, 26, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.D.; Neufeld, J.; Leson, G. Evaluating the quality of protein from hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) products through the use of the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11801–11807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, J.C. Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview. Euphytica 2004, 140, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awol, S.M.; Kuyu, C.G.; Bereka, T.Y. Physicochemical stability, microbial growth, and sensory quality of teff flour as affected by packaging materials during storage. LWT 2023, 189, 115488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Coupland, J.N. The effect of surfactants on the solubility, zeta potential, and viscosity of soy protein isolates. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Ten, Z.; Wang, X.S.; Yang, X.Q. Physicochemical and functional properties of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) protein isolate. J.Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8945–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moure, A.; Sineiro, J.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Functionality of oilseed protein products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero Cánovas, J.; Zafrilla Rentero, P.; Martínez-Cachá Martínez, A.; Leal Hernández, M.; Abellán Alemán, J. Péptidos bioactivos. Clin. Invest. Arterioscl. 2011, 23, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Griffin, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, W. Antioxidant properties of hemp proteins: From functional food to phytotherapy and beyond. Molecules 2022, 27, 7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megías, C.; Yust, M.D.M.; Pedroche, J.; Lquari, H.; Giron-Calle, J.; Alaiz, M.; Millán, F.; Vioque, J. Purification of an ace inhibitory peptide after hydrolysis of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) protein isolates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa Crespo, I.; Laviada Molina, H.; Chel-Guerrero, L.; Ortíz-Andrade, R.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Efecto inhibitorio de fracciones peptídicas derivadas de la hidrólisis de semillas de chía (Salvia hispanica) sobre las enzimas α-amilasa y α-glucosidasa. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Huang, Y.; Islam, S.; Fan, B.; Tong, L.; Wang, F. Influence of the degree of hydrolysis on functional properties and antioxidant activity of enzymatic soybean protein hydrolysates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Lammi, C.; Boschin, G.; Zanoni, C.; Arnoldi, A. Exploration of potentially bioactive peptides generated from the enzymatic hydrolysis of hempseed proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10174–10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picariello, G.; Ferranti, P.; Addeo, F. Use of brush border membrane vesicles to simulate the human intestinal digestion. Food Res. Int. 2016, 88, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Rosales, L.B.; Cruz-Guerrero, A.E.; García-Garibay, J.M.; Gómez-Ruíz, L.C.; Contreras-López, E.; Guzman-Rodríguez, F.; Gonzalez-Olivares, L.C. Bioactive peptides of whey: Obtaining, activity, mechanism of action, and further applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 10351–10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Z.; Everett, D.W.; Gilbert, E.P.; Singh, H.; Ye, A. Digestion of food proteins: The role of pepsin. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 6919–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Jung, D.; Lee, J.; Ki, W.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, E.M.; Nam, M.S.; Kim, K.K. Bioactive peptides in the pancreatin-hydrolysates of whey protein support cell proliferation and scavenge reactive oxygen species. Anim. Cells Syst. 2022, 26, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.H.; Bean, S.; Hsieh, C.F.; Shi, Y.C. Changes in protein and starch digestibility in sorghum flour during heat–moisture treatments. J. Sci. Food Agric 2017, 97, 4770–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, T.; Li, H.; Yu, J. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Property, Structure, and Aggregation of Skim Milk Proteins. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 714869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, E.; Tsopmo, A.; Oliviero, T.; Fogliano, V.; Udenigwe, C.C. Bioprocessing of common pulses changed seed microstructures, and improved dipeptidyl peptidase-IV and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udenigwe, C.C.; Aluko, R.E. Food protein-derived bioactive peptides: Production, processing, and potential health benefits. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, R11–R24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.F.; Hu, F.Y.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.R.; Luo, H.Y. Influence of amino acid compositions and peptide profiles on antioxidant capacities of two protein hydrolysates from skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) dark muscle. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2580–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.N.; Jiang, Y.F.; Ru, J.N.; Lu, J.H.; Ding, B.; Wu, J. Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Weiss-Steider, B.; Rivera-Martínez, A.R.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Casein and Peptides Derived from Casein as Antileukaemic Agents. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 8150967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, M.; Moridnia, A.; Mortazavi, D.; Salehi, M.; Bagheri, M. Kefir: A powerful probiotics with anticancer properties. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Alonso, J.J.; López-Lázaro, M. Dietary manipulation of amino acids for cancer therapy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; You, M.; Nguyen, D.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Li, Y.Y.; Feun, L.G.; Kuo, M.T.; Savaraj, N. Enhancing the Effect of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Signaling and Arginine Deprivation in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, M.; Ibragimow, I.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H. Caco-2 Cell Line Standardization with Pharmaceutical Requirements and In Vitro Model Suitability for Permeability Assays. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón-Calle, J.; Vioque, J.; Yust, M.D.M.; Pedroche, J.; Alaiz, M.; Millán, F. Effect of chickpea aqueous extracts, organic extracts, and protein concentrates on cell proliferation. J. Med. Food 2004, 7, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hernandez, C.; Aguilera-Puga, M.D.C.; Plisson, F. Deconstructing the potency and cell-line selectivity of membranolytic anticancer peptides. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, K.; Berneman, Z.N.; Van Bockstaele, D.R. Cell cycle and apoptosis. Cell Prolif. 2003, 36, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Dong, Y.; Sun, Y.F.; Mei, X.S.; Ma, X.S.; Shi, J.; Yanh, Q.L.; Ji, Y.R.; Zhang, Z.H.; Sun, H.N.; et al. Anticancer property of hemp bioactive peptides in Hep3B liver cancer cells through Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givonetti, A.; Tonello, S.; Cattaneo, C.; D’Onghia, D.; Vercellino, N.; Sainaghi, P.P.; Colangelo, D.; Cavaletto, M. Hempseed Water-Soluble Protein Fraction and Its Hydrolysate Display Different Biological Features. Life 2025, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Guo, H.; Teng, C.; Zhang, B.; Blecker, C.; Ren, G. Colon cancer activity of novel peptides isolated from in vitro digestion of quinoa protein in Caco-2 Cells. Foods 2022, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruslanov, E.; Kusmartsev, S. Chapter 4 Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry. In Advanced Protocols in Oxidative Stress II, Methods in Molecular Biology; Armstrond, D., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 594, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Joseph, J.A. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, E.S.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Zhou, W.; Chen, H.; Li, T.; Wu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, X.; et al. Phytochemical profiles of rice and their cellular antioxidant activity against ABAP induced oxidative stress in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Food Chem. 2020, 318, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixi, G.; Ye, T.; Hong, L.; Wang, T.; Monticello, C.; Lopez-Barbosa, N.; Vincoff, S.; Yudistyra, V.; Zhao, L.; Haarer, E.; et al. SaLT&PepPr is an interface-predicting language model for designing peptide-guided protein degraders. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, O.; Jakeman, P.; FitzGerald, R.J. Antioxidative peptides: Enzymatic production, in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity and potential applications of milk-derived antioxidative peptides. Amino Acids 2013, 44, 797–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Quan, Z.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J.A. New insights into antioxidant peptides: An overview of efficient screening, evaluation models, molecular mechanisms, and applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, T.; Chen, D.; Gu, H.; Mao, X. Identification and molecular docking of antioxidant peptides from hemp seed protein hydrolysates. LWT 2021, 147, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Lo, Y.M. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed oil. Ultrason. Sonochemestry 2013, 20, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (Technical Bulletin); Sigma-Aldrich: St. Louis, MI, USA.

- AOAC International. AOAC Official International Methods of Analysis; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000; Volume 17, No. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Nissen, J. Determination of the degree of hydrolysis of food protein hydrolysates by trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1979, 27, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonklin, C.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O. Assessment of antioxidant properties of membrane ultrafiltration peptides from mungbean meal protein hydrolysates. PeerJ 2018, 8, e5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiz, M.; Navarro, J.L.; Girón, J.; Vioque, E. Amino acid analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography after derivatization with diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate. J. Chromatogr. 1992, 591, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yust, M.M.; Pedroche, J.; Girón-Calle, J.; Vioque, J.; Millán, F.; Alaiz, M. Determination of tryptophan by high-performance liquid chromatography of alkaline hydrolysates with spectrophotometric detection. Food Chem. 2024, 85, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J.; Girón-Calle, J.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Pectin-rich extracts from olives inhibit proliferation of Caco-2 and THP-1 cells. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4844–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón-Calle, J.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J. Effect of chickpea protein hydrolysates on cell proliferation and in vitro bioavailability. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Determination | HS | HSF |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein (N × 6.25) | 20.25 ± 0.09 | 57.84 ± 3.56 |

| Fat | 57.54 ± 0.20 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| Moisture | 2.88 ± 0.43 | 10.03 ± 0.37 |

| HSH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | PI | HSH | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

| Aspartic acid a | 11.68 ± 0.01 | 8.04 ± 0.01 | 10.08 ± 0.00 | 8.92 ± 0.01 | 10.45 ± 0.03 | 6.03 ± 0.01 |

| Glutamic acid b | 17.93 ± 0.06 | 12.44 ± 0.049 | 18 ± 0.01 | 16.86 ± 0.01 | 16.13 ± 0.01 | 10.40 ± 0.01 |

| Serine | 5.65 ± 0.01 | 3.40 ± 0.03 | 6.88 ± 0.05 | 6.02 ± 0.01 | 6.20 ± 0.01 | 5.41 ± 0.01 |

| Histidine | 3.07 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.09 | 3.73 ± 0.12 | 3.65 ± 0.09 | 3.40 ± 0.07 | 3.97 ± 0.10 |

| Glycine | 4.99 ± 0.11 | 3.71 ± 0.28 | 8.09 ± 0.03 | 5.56 ± 0.01 | 5.79 ± 0.00 | 4.35 ± 0.01 |

| Threonine | 3.75 ± 0.02 | 2.69 ± 0.01 | 4.90 ± 0.04 | 3.74 ± 0.05 | 4.06 ± 0.08 | 3.39 ± 0.01 |

| Arginine | 13.52 ± 0.13 | 9.04 ± 0.05 | 15.24 ± 0.05 | 14.28 ± 0.01 | 13.80 ± 0.00 | 14.14 ± 0.03 |

| Alanine | 4.61 ± 0.06 | 3.39 ± 0.17 | 3.89 ± 0.17 | 4.79 ± 0.00 | 5.21 ± 0.02 | 5.22 ± 0.00 |

| Proline | 1.72 ± 0.04 | 1.27 ± 0.07 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 1.86 ± 0.02 | 2.06 ± 0.08 |

| Tyrosine | 2.73 ± 0.00 | 2.05 ± 0.00 | 1.67 ± 0.01 | 2.79 ± 0.01 | 2.57 ± 0.08 | 4.38 ± 0.01 |

| Valine | 5.80 ± 0.04 | 3.93 ± 0.26 | 5.61 ± 0.01 | 5.8 ± 0.01 | 6.26 ± 0.40 | 6.66 ± 0.01 |

| Methionine | 1.17 ± 0.00 | 1.86 ± 0.03 | 1.62 ± 0.03 | 2.60 ± 0.02 | 1.88 ± 0.09 | 2.19 ± 0.00 |

| Cysteine | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| Isoleucine | 4.73 ± 0.03 | 3.32 ± 0.09 | 4.76 ± 0.01 | 4.80 ± 0.02 | 5.16 ± 0.02 | 5.00 ± 0.01 |

| Tryptophan | 1.4 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 1.2 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.04 |

| Leucine | 7.77 ± 0.03 | 5.26 ± 0.06 | 5.96 ± 0.01 | 7.16 ± 0.01 | 6.90 ± 0.01 | 11.22 ± 0.04 |

| Phenylalanine | 5.49 ± 0.02 | 3.71 ± 0.14 | 3.86 ± 0.01 | 4.75 ± 0.05 | 4.57 ± 0.00 | 9.87 ± 0.04 |

| Lysine | 3.90 ± 0.01 | 2.94 ± 0.02 | 3.61 ± 0.01 | 4.30 ± 0.01 | 4.58 ± 0.01 | 4.44 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juárez-Cruz, M.V.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Vioque, J.; Girón-Calle, J.; Quevedo-Corona, L. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311741

Juárez-Cruz MV, Jiménez-Martínez C, Vioque J, Girón-Calle J, Quevedo-Corona L. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311741

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuárez-Cruz, Merit Valeria, Cristian Jiménez-Martínez, Javier Vioque, Julio Girón-Calle, and Lucía Quevedo-Corona. 2025. "Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311741

APA StyleJuárez-Cruz, M. V., Jiménez-Martínez, C., Vioque, J., Girón-Calle, J., & Quevedo-Corona, L. (2025). Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Hemp Seed Proteins (Cannabis sativa L.), Protein Hydrolysate, and Its Fractions in Caco-2 and THP-1 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311741