Multi-Target Neuroprotective Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Ficus benjamina L. Leaf Extracts: Mitochondrial Modulation, Antioxidant Defense, and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival In Vivo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

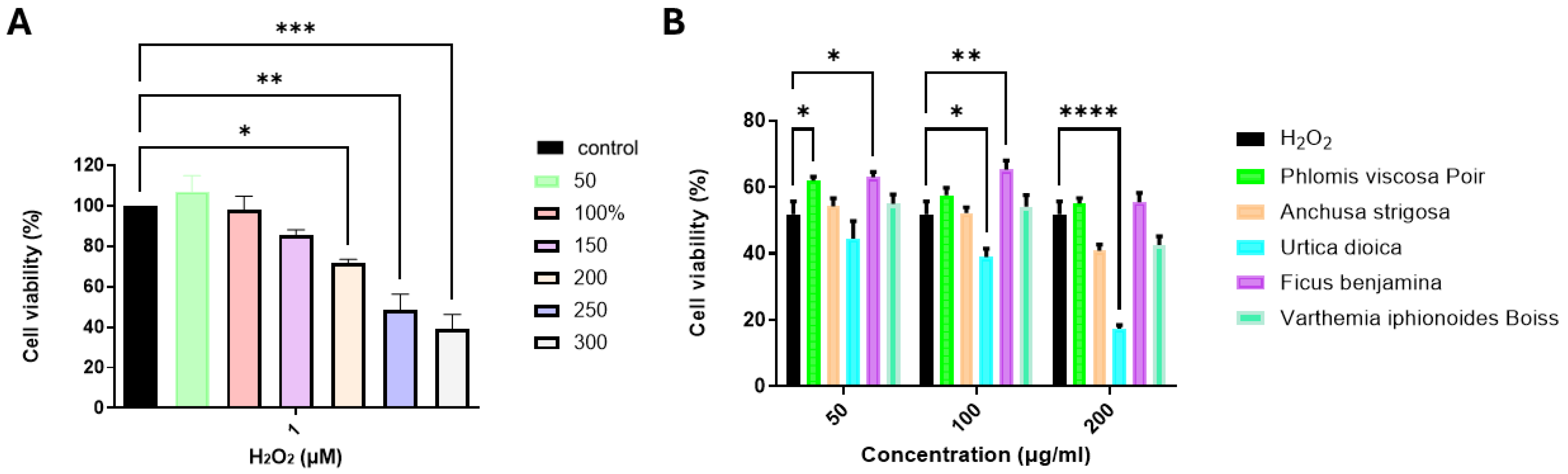

2.1. Evaluation of the Neuroprotective Effects of Plant Extracts on H2O2-Treated SH-SY5Y Cells

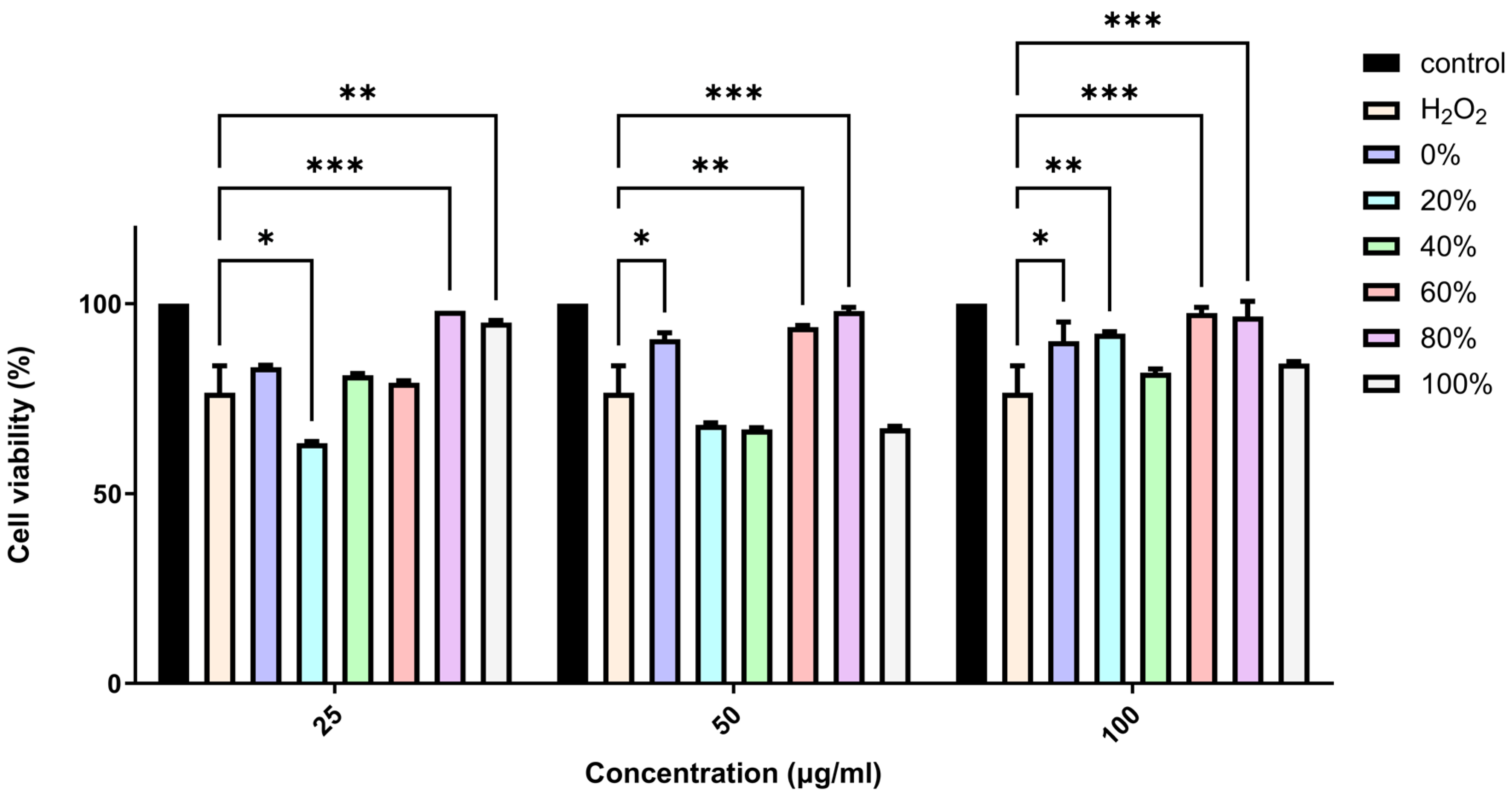

2.2. Evaluation of the Neuroprotective Effects of F. benjamina Fractions on H2O2-Treated SH-SY5Y Cells

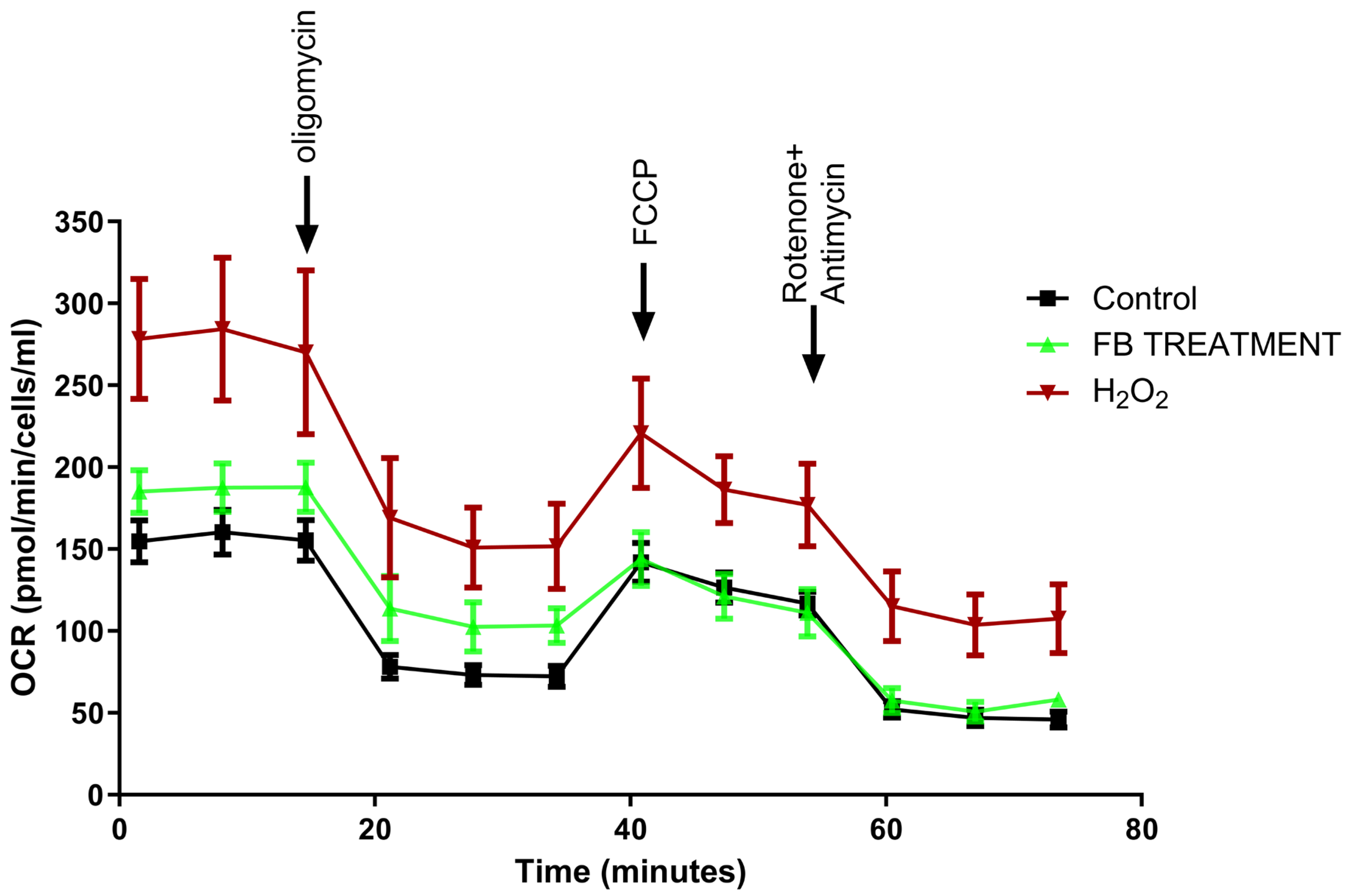

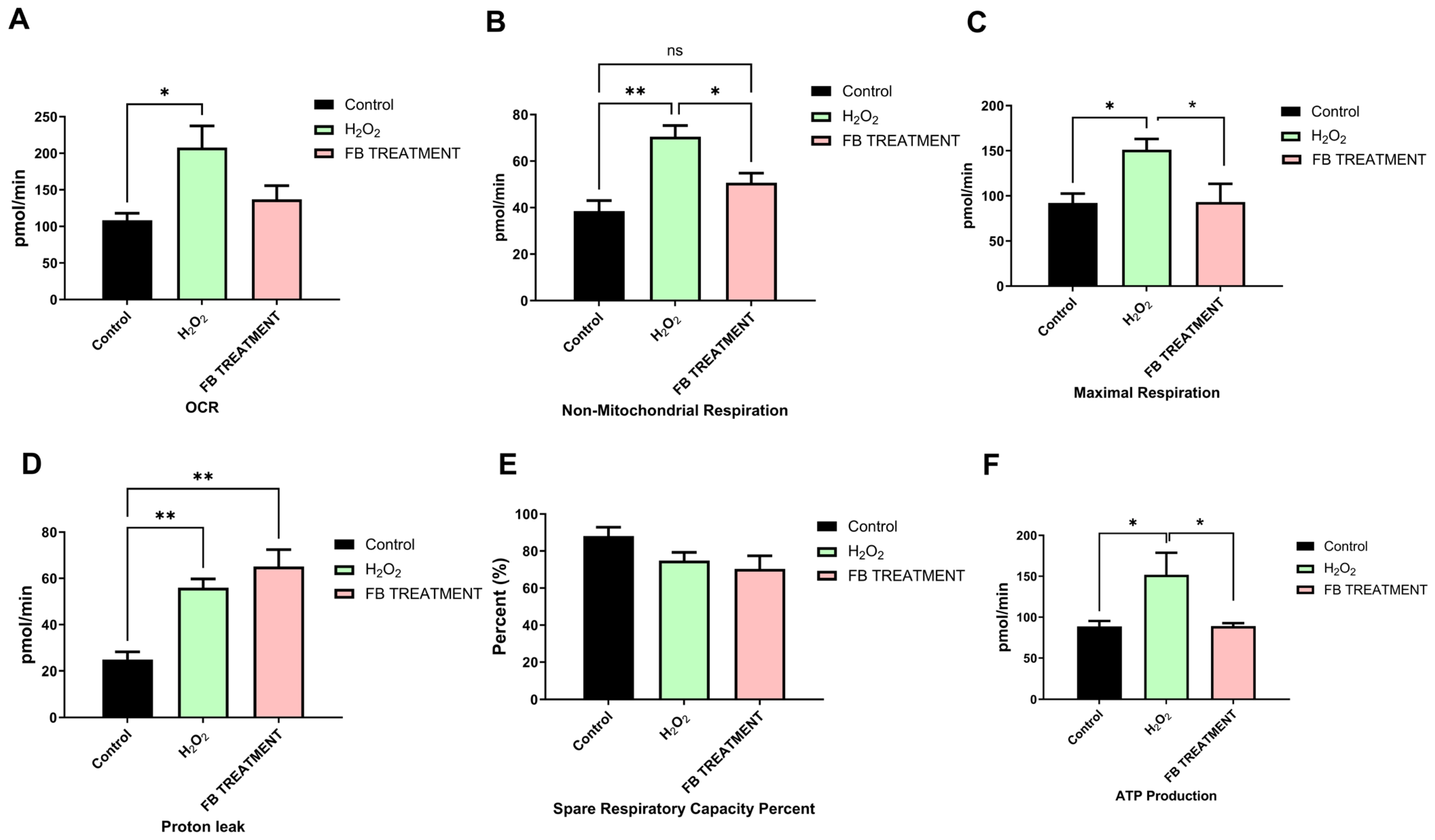

2.3. Favorable Effects of F. benjamina 80% Fraction on Mitochondrial Respiration in H2O2-Treated SH-SY5Y Cells

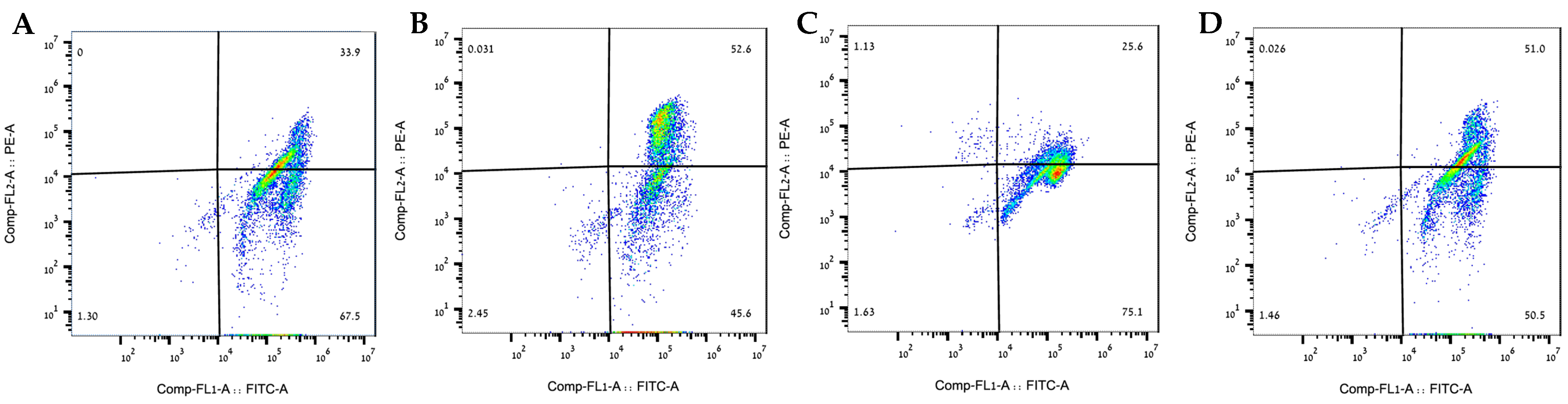

2.4. The 80% Fraction Alleviated Induced Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Damage in SH-SY5Y Cells

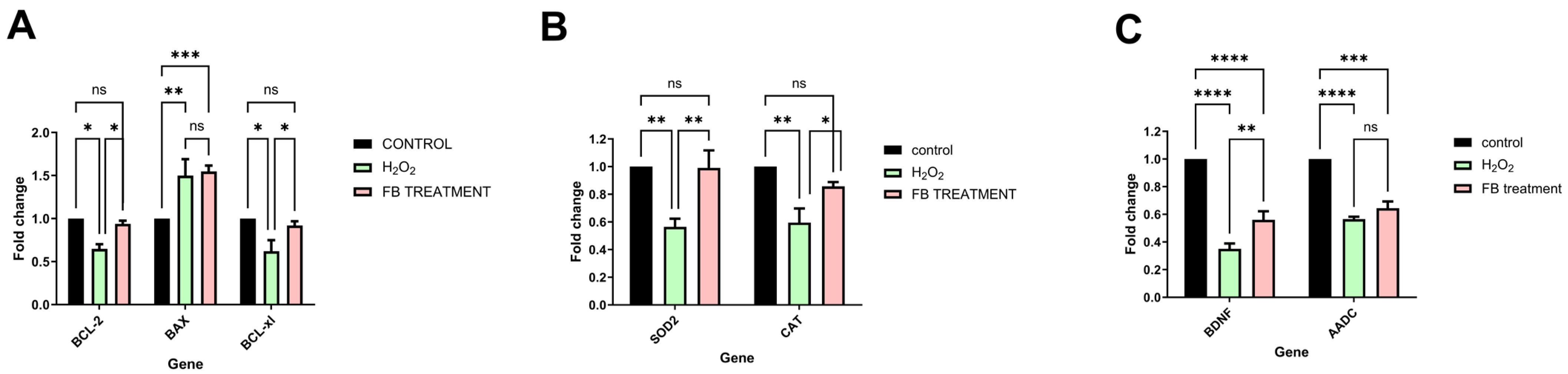

2.5. Multi-Target Neuroprotective Mechanisms of 80% Fraction Against Oxidative Stress

2.6. BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) and AADC (Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase)

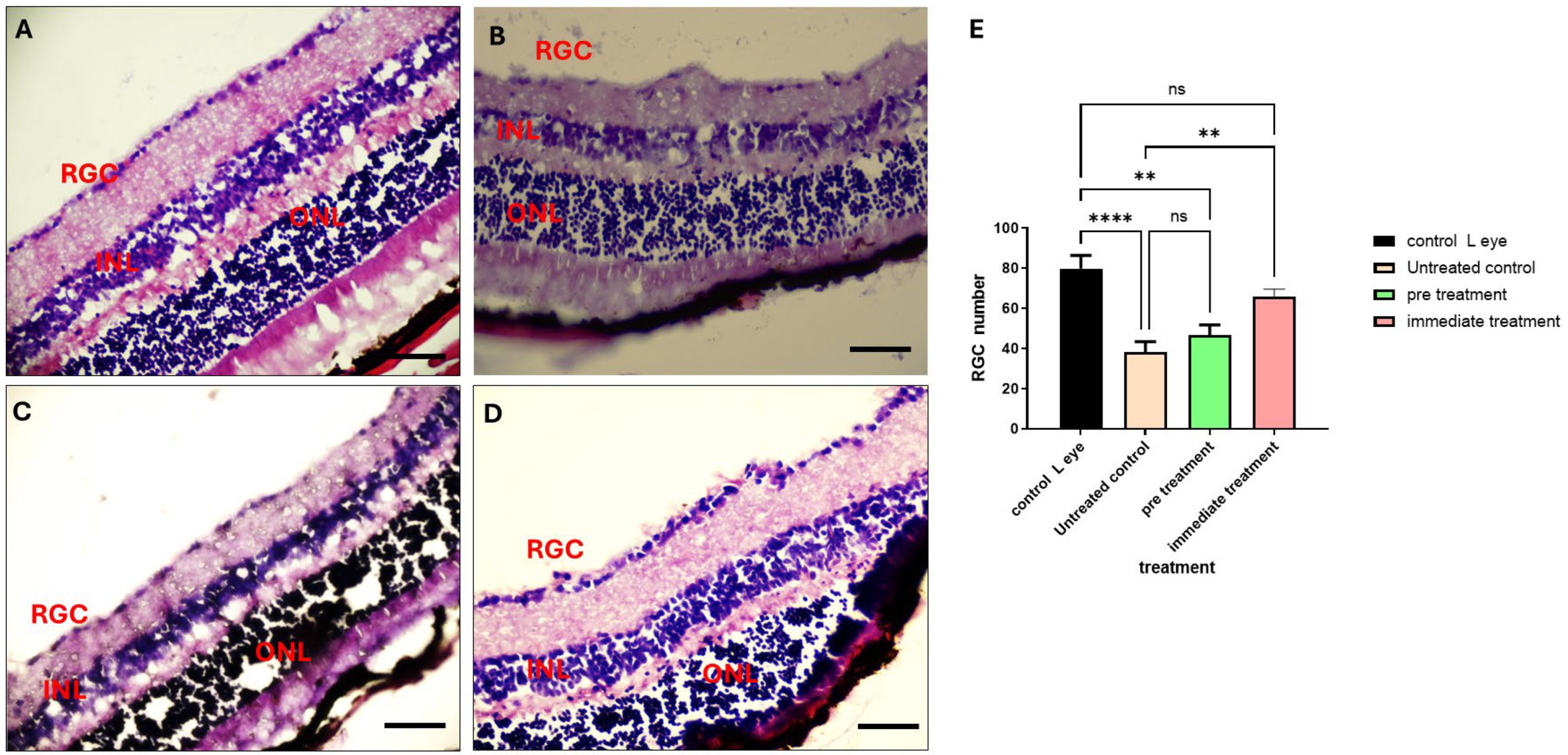

2.7. The 80% Fraction Enhances Retinal Ganglion Cell (RGCs’) Survival Following ONC

2.8. Identification of Phytochemicals

3. Discussion

3.1. Cytoprotective Effects of F. benjamina Leaf Extract

3.2. Mitochondrial Functional Modulation

3.3. Gene Expression Modulation by F. benjamina Extract

3.4. In Vivo Neuroprotection

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Line

4.2. Treatment of Plant Material

4.3. Identification of Plant Compounds

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay

4.6. RNA Isolation and Assessment of mRNA Expression Using Real-Time RT-PCR

4.6.1. RNA Extraction

4.6.2. cDNA Synthesis

4.6.3. Real-Time PCR

4.7. Evaluation of Mitochondrial Respiration and Cellular Bioenergetics

4.8. Establishment of Optic Nerve Crush Model and Intravitreal Injections

4.8.1. Animals

4.8.2. Optic Nerve Crush (ONC) Model

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AADC | Aromatic L-amino Acid Decarboxylase |

| BAX | BCL2-associated X |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FCCP | Carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| LC-ESI-MS | Liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry |

| MALDI-TOF-MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| ONC | Optic nerve crush |

| SOD2 | Superoxide Dismutase 2 |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Li, X.; Kong, X.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Lv, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, X. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Ischemic Stroke, 1990–2021: An Analysis of Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, D.; Small, C.N.; Goutnik, M.; Hoh, B. Ischemic Stroke. In Acute Care Neurosurgery by Case Management Pearls and Pitfalls; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambi, L.; Hamad, A.; Salah, H.; Sulieman, A. Stroke and Disability: Incidence, Risk Factors, Management, and Impact. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.K.; Rich, W.; Reilly, M.A. Oxidative Stress in the Brain and Retina after Traumatic Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1021152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonfiglio, F.; Böhm, E.W.; Pfeiffer, N.; Gericke, A. Oxidative Stress: A Suitable Therapeutic Target for Optic Nerve Diseases? Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Ye, Y.; Jian, Z.; Zhi, Z.; Gu, L. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation to Prevent Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, Q.W. Refocusing Neuroprotection in Cerebral Reperfusion Era: New Challenges and Strategies. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W. Regulation of BDNF-TrkB Signaling and Potential Therapeutic Strategies for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J.M.; Melovn, S. SOD2 in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Melendez, J.A.; Cederbaum, A.I. Overexpression of Catalase in Cytosolic or Mitochondrial Compartment Protects HepG2 Cells against Oxidative Injury. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26217–26224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Candelario-Jalil, E. Emerging Neuroprotective Strategies for the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke: An Overview of Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 335, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccilli, B.; Alan, A.; Aljeradat, B.; Shahzad, A.; Almealawy, Y.; Chisvo, N.S.; Ennabe, M.; Weinand, M. Neuroprotection Strategies in Traumatic Brain Injury: Studying the Effectiveness of Different Clinical Approaches. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2024, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Xia, Q.; Zhan, G.; Bing, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Tian, W.; Lian, H.; Li, X.; Chu, Q. Vialinin A Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Neuronal Injuries after Ischaemic Stroke by Accelerating Keap1 Degradation through Inhibiting USP4-Mediated Deubiquitination. Phytomedicine 2024, 124, 155304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Sun, J.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wu, S.; Zhou, L.; Chung, S.K.; Cheng, X. Scutellarin Acts on the AR-NOX Axis to Remediate Oxidative Stress Injury in a Mouse Model of Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Phytomedicine 2022, 103, 154214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, V.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, A.; Huanbutta, K.; Dheer, D.; Sangnim, T. Natural Product-Based Pharmacological Studies for Neurological Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1011740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, H.; Pan, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Z.; Dong, W.; Xie, A.; Qi, X. Dendritic Hydrogels with Robust Inherent Antibacterial Properties for Promoting Bacteria-Infected Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 11144–11155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shen, Y.; You, S.; Shao, L.; Bao, R.; Zhang, D.; Dong, W.; Lin, J. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Nanoparticle-Functionalized Quaternary Chitosan/Dialdehyde Xanthan Gum Hydrogel for Oral Mucosa Repair. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 329, 147761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elufioye, T.O.; Berida, T.I.; Habtemariam, S. Plants-Derived Neuroprotective Agents: Cutting the Cycle of Cell Death through Multiple Mechanisms. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 3574012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachrach, Z.Y. Contribution of Selected Medicinal Plants for Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Sci. J. Fac. Med. Niš. 2012, 29, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Rajeswari, V.D.; Venkatraman, G.; Ramanathan, G. Phytochemicals in Parkinson’s Disease: A Pathway to Neuroprotection and Personalized Medicine. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 83, 1427–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, D.M.; Bland, J.S. A Review of the Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Cruciferous Vegetable Phytochemicals. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Afzal, S.; Khursheed, A.; Saeed, B.; Zahra, S.; Majeed, H.; Sarwar, S.; Qureshi, M.S.; Qureshi, M.S.; Qureshi, M.I.; et al. Phytochemical Profiling and Therapeutic Potential of Ficus Benjamina L.: Insights into Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 2024, 4, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.; Ranawat, M.S. A Review on Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activity of Ficus Benjamina. Curr. Funct. Foods 2024, 3, E26668629305712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisha, N.; Sreenivasulu, M.; Sangeeta, K.; Chetty, C. Antioxidant Properties of Ficus Species—A Review. Int. J. Pharmtech. Res. 2010, 2, 2174–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, A.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Budovsky, A.; Khalfin, B.; Ben-Shabat, S. Therapeutic Potential of Ficus Benjamina: Phytochemical Identification and Investigation of Antimicrobial, Anticancer, Pro-Wound-Healing, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Rasool, N.; Rizwan, K.; Zubair, M.; Riaz, M.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M.; Rana, U.A.; Nafady, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.E. Chemical Composition and Biological Studies of Ficus Benjamina. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-X.; Zhang, B.-D.; Zhu, W.-F.; Zhang, C.-F.; Qin, Y.-M.; Abe, M.; Akihisa, T.; Liu, W.-Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of Ficus Hispida L.f.: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari Zarch, Z.; Salehi, E.; Morovati-Sharifabad, M.; Paidar Ardakani, A.; Heydarnejad, M.S. Effect of Aqueous Extract of Fig Fruit (Ficus Carica) on Wound Healing in Albino Rabbits. J. Shahrekord Univ. Med. Sci. 2022, 24, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapar, M.L.G.; Alejandro, G.J.D.; Meve, U.; Liede-Schumann, S. Quantitative Ethnopharmacological Documentation and Molecular Confirmation of Medicinal Plants Used by the Manobo Tribe of Agusan Del Sur, Philippines. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udonkang, M.; Inyang, I.; Fidelis, F.; Isamoh, T. Assessment of the Neurotoxicity of Ethanol Leaf Extract of Ficus Benjamina (Weeping Fig) on Brain of Wistar Rats. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2024, 30, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmolinsky, L.; Huleihel, M.; Zaccai, M.; Ben-Shabat, S. Potent Antiviral Flavone Glycosides from Ficus Benjamina Leaves. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-N.; Shang, N.-Y.; Kang, Y.-Y.; Sheng, N.; Lan, J.-Q.; Tang, J.-S.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.-L.; Peng, Y. Caffeic Acid Alleviates Cerebral Ischemic Injury in Rats by Resisting Ferroptosis via Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amico, R.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Cordaro, M.; Fusco, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Interdonato, L.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Crea, R.; Siracusa, R.; et al. Hidrox® and Chronic Cystitis: Biochemical Evaluation of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Pain. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1046, Correction in Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuto, M.; Modafferi, S.; Rampulla, F.; Zimbone, V.; Tomasello, M.; Spano’, S.; Ontario, M.L.; Palmeri, A.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Siracusa, R.; et al. Redox Modulation of Stress Resilience by Crocus Sativus L. for Potential Neuroprotective and Anti-Neuroinflammatory Applications in Brain Disorders: From Molecular Basis to Therapy. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2022, 205, 111686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuto, M.; Majzúnová, M.; Torcitto, G.; Antonuzzo, S.; Rampulla, F.; Di Fatta, E.; Trovato Salinaro, A. Functional Food Nutrients, Redox Resilience Signaling and Neurosteroids for Brain Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.H.; Sharma, N.; An, S.S.A. Mechanistic Insights into the Neuroprotective Potential of Sacred Ficus Trees. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.; Trewin, A.J.; Amitrano, A.M.; Kim, M.; Wojtovich, A.P. Use the Protonmotive Force: Mitochondrial Uncoupling and Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 3873–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.R.; He, C.; Danes, J.M.; Paviani, V.; Coelho, D.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Bonini, M.G. Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase: What the Established, the Intriguing, and the Novel Reveal About a Key Cellular Redox Switch. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.S.; Sullivan, K.A.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Backus, C.; Hayes, J.M.; Sakowski, S.A.; Feldman, E.L. Neurodegeneration and Early Lethality in Superoxide Dismutase 2-Deficient Mice: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems. Neuroscience 2012, 212, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalouli, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Biswas, P.; Rahman, H.; Harrath, A.H.; Lee, I.S.; Kang, S.; Choi, J.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B. Targeting Natural Antioxidant Polyphenols to Protect Neuroinflammation and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1492517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, G.F.; Palmero, C.Y.; de Souza-Menezes, J.; Araujo, A.K.; Guimarães, A.G.; de Barros, C.M. Dermatan Sulfate Obtained from the Phallusia Nigra Marine Organism Is Responsible for Antioxidant Activity and Neuroprotection in the Neuroblastoma-2A Cell Lineage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Maldonado, J.M.; Salazar, R.; Alvarez-Fitz, P.; Acevedo-Quiroz, M.; Flores-Alfaro, E.; Hernández-Sotelo, D.; Espinoza-Rojo, M.; Ramírez, M. Phenolic Compounds of Therapeutic Interest in Neuroprotection. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Liska, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Flavonoids and Their Role in Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Human Diseases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 413, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Nie, Z.; Shu, H.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Yu, S.; Liu, H. The Role of BDNF on Neural Plasticity in Depression. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebas, E.; Rzajew, J.; Radzik, T.; Zylinska, L. Neuroprotective Polyphenols: A Modulatory Action on Neurotransmitter Pathways. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, R.; Fu, H.; Liu, X.; Miao, L. Citrus Extraction Provides Neuroprotective Effect in Optic Nerve Crush Injury Mice through P53 Signaling Pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 122, 106517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z. Optic Nerve Crush Injury in Rodents to Study Retinal Ganglion Cell Neuroprotection and Regeneration. Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2708, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.Y.; Cringle, S.J. Oxygen Distribution in the Mouse Retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 2006, 47, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappoport, D.; Morzaev, D.; Weiss, S.; Vieyra, M.; Nicholson, J.D.; Leiba, H.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N. Effect of Intravitreal Injection of Bevacizumab on Optic Nerve Head Leakage and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival in a Mouse Model of Optic Nerve Crush. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 8160–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chibhabha, F.; Yang, Y.; Ying, K.; Jia, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ullah, S.; Liang, Z.; Xie, M.; Li, F. Non-Invasive Optical Imaging of Retinal Aβ Plaques Using Curcumin Loaded Polymeric Micelles in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 Transgenic Mice for the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 7438–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, T.C.; Zahavi, A.; Friedman-Gohas, M.; Weiss, S.; Sternfeld, A.; Ilguisonis, A.; Badash, D.; Geffen, N.; Ofri, R.; BarKana, Y.; et al. Azithromycin and Sildenafil May Have Protective Effects on Retinal Ganglion Cells via Different Pathways: Study in a Rodent Microbead Model. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, B.; Richard, S.; Kramarz Dadon, J.; Sela, T.C.; Geffen, N.; Halperin-Sternfeld, M.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N.; Zahavi, A. Molecular and Histological Characterization of a Novel Hydrogel-Based Strategy for Inducing Experimental Glaucoma in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Helmuth, M.; Trzeczak, D.; Chindo, B.A. Methanol Extract of Ficus Platyphylla Decreases Cerebral Ischemia Induced Injury in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolkiffly, S.Z.I.; Stanslas, J.; Abdul Hamid, H.; Mehat, M.Z. Ficus Deltoidea: Potential Inhibitor of pro-Inflammatory Mediators in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Activation of Microglial Cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Moriano, C.; González-Burgos, E.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Mitochondria-Targeted Protective Compounds in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 408927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.T.; Oertel, W.H.; Surmeier, D.J.; Geibl, F.F. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease—A Key Disease Hallmark with Therapeutic Potential. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, K.R.; Singh, S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease–A Step towards Mitochondria Based Therapeutic Strategies. Aging Health Res. 2023, 3, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratviman-Storobinsky, O.; Hasanreisoglu, M.; Offen, D.; Barhum, Y.; Weinberger, D.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N. Progressive Damage along the Optic Nerve Following Induction of Crush Injury or Rodent Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in Transgenic Mice. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 2171. [Google Scholar]

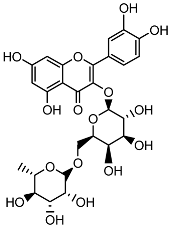

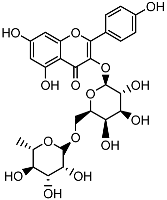

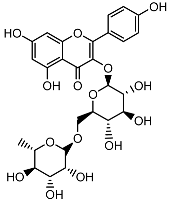

| Compound | Molecular Structure | Methods of Identification | Conc., mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic acid |  | HPLC LC-ESI-MS | 7.6 ± 0.58 |

| Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside |  | HPLC LC-ESI-MS | 11.5 ± 0.21 |

| Kaempferol 3-O-robinobioside |  | HPLC LC-ESI-MS | 4.3 ± 0.19 |

| Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside |  | HPLC LC-ESI-MS | 3.9 ± 0.55 |

| Gene | Primer Pair | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| BDNF |

FP

RP |

ATGACCATCCTTTTTCCTTACT

GCCACCTTGTCCTCGGAT |

| AADC |

FP

RP |

AACAAAGTGAATGAAGCTCTTC

GCTCTTTGATGTGTTCCCAG |

| SOD2 |

FP

RP |

AGGCCGTGTGCGTGCTGAAG

CACCTTTGCCCAAGTCATCTGC |

| CAT |

FP

RP |

CCTTTCTGTTGAAGATGCGGCG

GGCGGTGAGTGTCAGGATAG |

| Bcl-2 |

FP

RP |

GATTGAGGGATCGTTGCCTTA

CCTTGGCATGAGATGCAGGA |

| BAX |

FP

RP |

GCGAGTGTCTCAAGCGCATC

CCAGTTGAAGTTGCCGTCAGAA |

| Bcl-xl |

FP

RP |

CTTTGCCTAAGGCGGATTTGAA

AATAGGGATGGGCTCAACCAGTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dahan, A.; Oz, M.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Zahavi, A.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N.; Khalfin, B.; Ben-Shabat, S.; Lubin, B.C.R. Multi-Target Neuroprotective Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Ficus benjamina L. Leaf Extracts: Mitochondrial Modulation, Antioxidant Defense, and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311746

Dahan A, Oz M, Yarmolinsky L, Zahavi A, Goldenberg-Cohen N, Khalfin B, Ben-Shabat S, Lubin BCR. Multi-Target Neuroprotective Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Ficus benjamina L. Leaf Extracts: Mitochondrial Modulation, Antioxidant Defense, and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival In Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311746

Chicago/Turabian StyleDahan, Arik, Moria Oz, Ludmila Yarmolinsky, Alon Zahavi, Nitza Goldenberg-Cohen, Boris Khalfin, Shimon Ben-Shabat, and Bat Chen R. Lubin. 2025. "Multi-Target Neuroprotective Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Ficus benjamina L. Leaf Extracts: Mitochondrial Modulation, Antioxidant Defense, and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival In Vivo" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311746

APA StyleDahan, A., Oz, M., Yarmolinsky, L., Zahavi, A., Goldenberg-Cohen, N., Khalfin, B., Ben-Shabat, S., & Lubin, B. C. R. (2025). Multi-Target Neuroprotective Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Ficus benjamina L. Leaf Extracts: Mitochondrial Modulation, Antioxidant Defense, and Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival In Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311746