Integrated Genomic–Metabolomic Analysis for Tri-Categorical Classification of Type 2 Diabetes Status in the Korean Ansan–Ansung Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

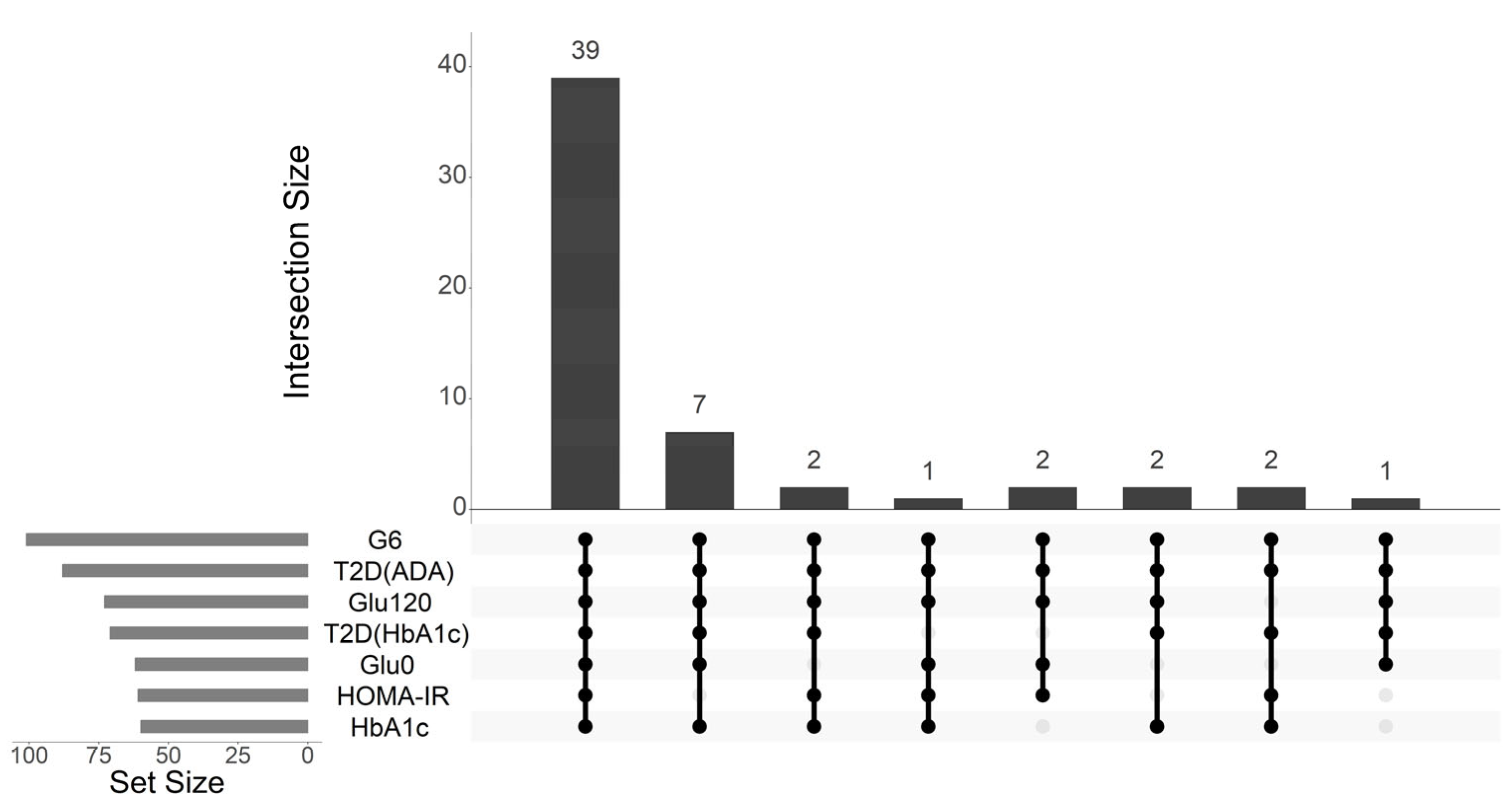

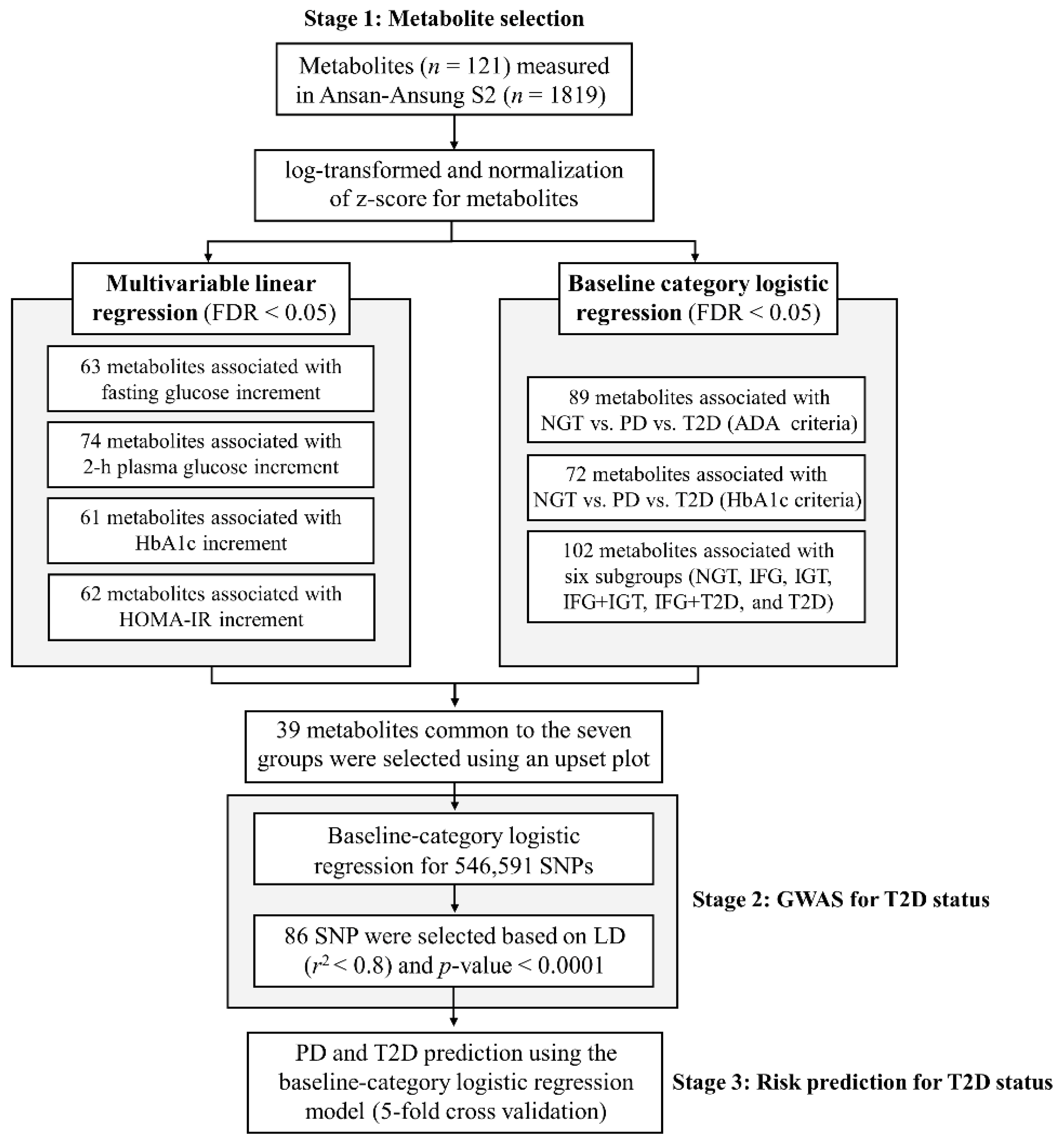

2.2. Metabolites Associated with Glycemic Traits and T2D Status

2.3. Genetic Variant Associated with T2D Status

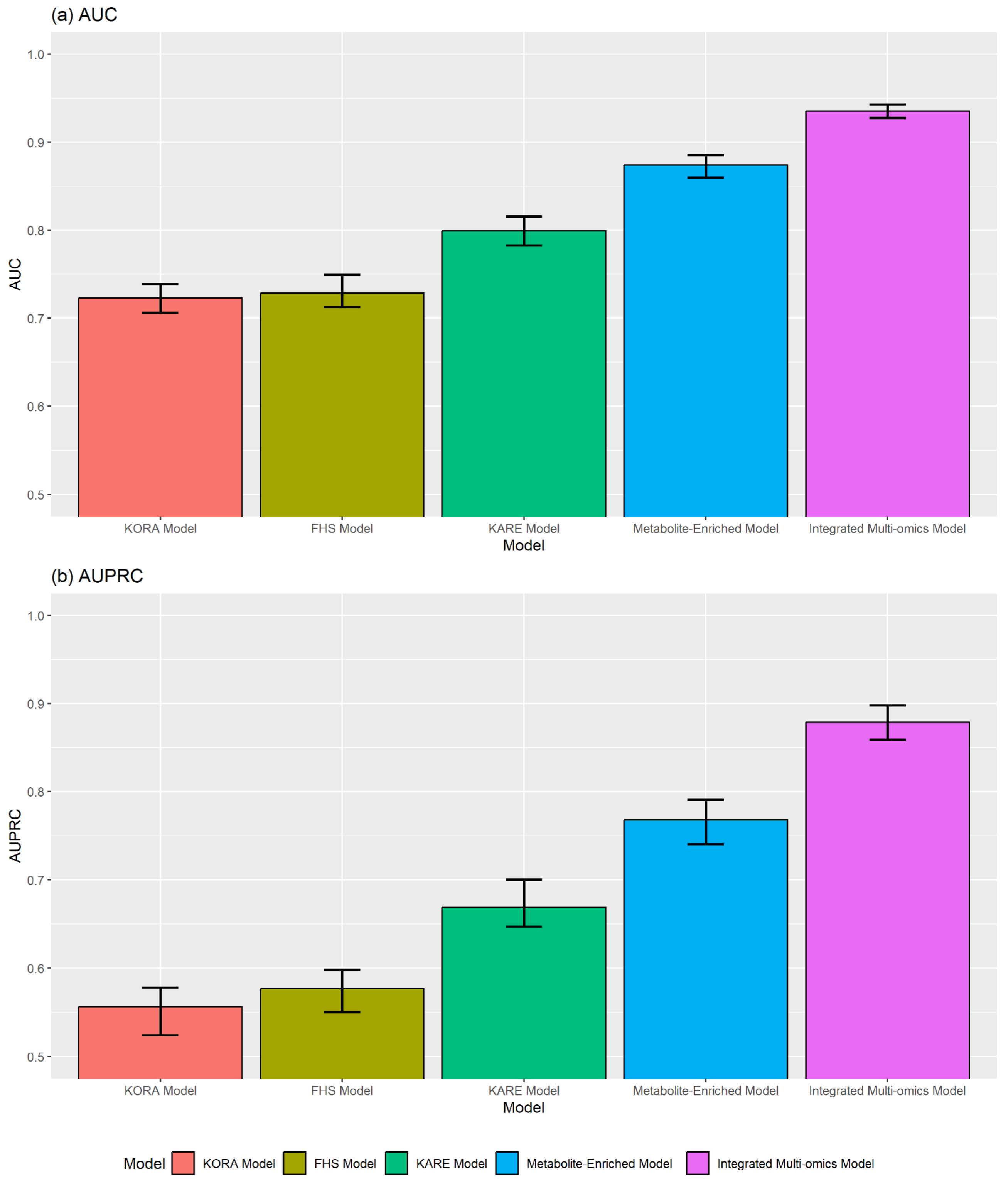

2.4. Performance of T2D Prediction Models

2.5. Comparison with Existing Prediction Models

2.6. Functional Annotation of Associated Genetic Variants

3. Discussion

3.1. Valine

3.2. Alanine

3.3. Glutamate and Glutamine

3.4. Glycine

3.5. Lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC) Acyl C18:2

3.6. Hexose

3.7. Sphingomyelins

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Cohort and Design

4.2. Assessment of Clinical and Biochemical Factors

4.3. Definition of T2D Status

4.4. Genotyping and QC

4.5. Metabolomic Profiling and Preprocessing

4.6. Statistical Analyses

4.6.1. Selection of Metabolites Linked to Glycemic Traits

- ADA-based T2D status: Participants were grouped into NGT (=1), PD (=2), or T2D (=3) groups according to the ADA criteria.

- HbA1c-based grouping: Based on HbA1c levels, participants were classified into the following three groups: normal (<5.7%), PD (5.7–6.4%), and T2D (≥6.5%).

- Six glucose subgroups: To further delineate intermediate phenotypes, we defined six categories based on the FPG and 2h-PG levels. NGT was defined as FPG < 100 mg/dL and 2h-PG < 140 mg/dL. IFG was defined as 100 ≤ FPG ≤ 125 mg/dL with 2h-PG < 140 mg/dL, whereas IGT was defined as FPG < 100 mg/dL with 140 ≤ 2h-PG < 200 mg/dL. Combined IFG and IGT was defined as 100 ≤ FPG ≤ 125 mg/dL and 140 ≤ 2h-PG < 200 mg/dL. Further, we specified an IFG with diabetes-range 2h-PG (IFG+T2D) group (100 ≤ FPG ≤ 125 mg/dL and 2h-PG ≥ 200 mg/dL) and a T2D with normal FPG group (FPG < 100 mg/dL and 2h-PG ≥ 200 mg/dL).

4.6.2. Genomic Association with T2D Status

4.6.3. Construction and Assessment of Prediction Models

- Model 1 (Clinical Risk Model): This foundational model included only standard demographic, clinical, and lipid variables (age, sex, BMI, and HDL cholesterol level) to establish baseline predictive performance.

- Model 2 (Metabolite-Enriched Model): The second model was augmented by incorporating the full panel of metabolites identified as significant in our initial association analyses. This model was designed to assess the predictive contributions of the metabolic signatures.

- Model 3 (Integrated Multi-omics Model): The final model integrated the set of pruned independent SNPs from the GWAS alongside clinical and metabolomic factors. This model represents the full-scale multi-omics approach.

4.6.4. Functional Annotation of the Associated Loci

- Initial mapping to genes and regulatory regions: We conducted variant annotation using ANNOVAR (version 2018Apr16, https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/ (accessed on 26 November 2025)) with the hg19/GRCh37 reference genome and Ensemble gene build 106 [123]. All SNPs that exceeded the prespecified significance threshold were first mapped to their nearest genes and subsequently interrogated using additional publicly available resources, including the Ensembl VEP and Regulome DB databases.

- Assessment of deleteriousness and pathogenicity: Each variant was further evaluated using CADD [58] and DANN [59] scores. These complementary tools integrate evolutionary conservation, biochemical features, and regulatory context to estimate the probability of a variant being functionally deleterious. Variants exceeding commonly applied thresholds (CADD ≥ 12.37 or DANN ≥ 0.8) were prioritized for downstream consideration.

- Integration with expression and regulatory databases: To gain insight into potential issue-specific effects, prioritized variants were cross-referenced with eQTL datasets and RegulomeDB annotations [60]. Particular attention was given to variants with a RegulomeDB score of 3 or lower, as these are more likely to lie within transcription factor-binding sites or DNase-hypersensitive regions with regulatory potential. This step enabled the identification of variants associated with altered gene expression in metabolically relevant tissues such as the liver, adipose tissue, and pancreas.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Accuracy |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| AUPRC | Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve |

| BA | Balanced Accuracy |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CADD | Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DANN | Deleterious Annotation of genetic variants using Neural Networks |

| PD | Prediabetes |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| eQTL | Expression Quantitative Trait Locus |

| F1 | F1-Score |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FHS | Framingham Heart Study |

| FPG | Fasting Plasma Glucose |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| IFG | Isolated Impaired Fasting Glucose |

| IGT | Impaired Glucose Tolerance |

| KARE | Korean Association Resource |

| KoGES | Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study |

| KORA | Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg |

| LD | Linkage Disequilibrium |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NGT | Normal Glucose Tolerance |

| OvR | One-vs.-Rest |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TCHL | Total Cholesterol |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| QC | Quality Control |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| 2h-PG | 2 h postprandial Plasma Glucose levels |

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119, Erratum in Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 204, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federation, I.D. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes, A. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44 (Suppl. S1), S15–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabák, A.G.; Herder, C.; Rathmann, W.; Brunner, E.J.; Kivimäki, M. Prediabetes: A high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet 2012, 379, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Taliun, D.; Thurner, M.; Robertson, N.R.; Torres, J.M.; Rayner, N.W.; Payne, A.J.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Scott, R.A.; Grarup, N.; et al. Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes loci to single-variant resolution using high-density imputation and islet-specific epigenome maps. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujkovic, M.; Keaton, J.M.; Lynch, J.A.; Miller, D.R.; Zhou, J.; Tcheandjieu, C.; Huffman, J.E.; Assimes, T.L.; Lorenz, K.; Zhu, X.; et al. Discovery of 318 new risk loci for type 2 diabetes and related vascular outcomes among 1.4 million participants in a multi-ancestry meta-analysis. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Spracklen, C.N.; Marenne, G.; Varshney, A.; Corbin, L.J.; Luan, J.; Willems, S.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Horikoshi, M.; et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 840–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.I. Genomics, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2339–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolio, T.A.; Collins, F.S.; Cox, N.J.; Goldstein, D.B.; Hindorff, L.A.; Hunter, D.J.; McCarthy, M.I.; Ramos, E.M.; Cardon, L.R.; Chakravarti, A.; et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 2009, 461, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeggini, E.; Scott, L.J.; Saxena, R.; Voight, B.F.; Marchini, J.L.; Hu, T.; de Bakker, P.I.; Abecasis, G.R.; Almgren, P.; Andersen, G.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.H.; Ivanisevic, J.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: Beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, G.J.; Yanes, O.; Siuzdak, G. Innovation: Metabolomics: The apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferre, M.; Hruby, A.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.B.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Hu, F.B. Metabolomics in Prediabetes and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Stefan, N.; Yu, Z.; Mühlenbruch, K.; Drogan, D.; Joost, H.G.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U.; Hrabě de Angelis, M.; Peters, A.; et al. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes 2013, 62, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newgard, C.B. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, L. Metabolomics in nutrition research: Current status and perspectives. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Fan, J.; Sun, X.; Zheng, J.S.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, D. Integrative metabolomics and genomics reveal molecular signatures for type 2 diabetes and its cardiovascular complications. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmen, A.; Wroblewski, F.; Ladue, J.S. Transaminase activity in human blood. J. Clin. Investig. 1955, 34, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vozarova, B.; Stefan, N.; Lindsay, R.S.; Saremi, A.; Pratley, R.E.; Bogardus, C.; Tataranni, P.A. High alanine aminotransferase is associated with decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1889–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, E.G.; Testa, R.; Savarino, V. Liver enzyme alteration: A guide for clinicians. Cmaj 2005, 172, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.; Harris, R.; Sattar, N.; Ebrahim, S.; Davey Smith, G.; Lawlor, D.A. Alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and incident diabetes: The British Women’s Heart and Health Study and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, E.P.; Procópio, J.; Carvalho, C.R.; Carpinelli, A.R.; Newsholme, P.; Curi, R. New insights into fatty acid modulation of pancreatic beta-cell function. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2006, 248, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, J.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Russell, R.C.; Yu, F.X.; Park, H.W.; Plouffe, S.W.; Tagliabracci, V.S.; Guan, K.L. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 2015, 347, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solloway, M.J.; Madjidi, A.; Gu, C.; Eastham-Anderson, J.; Clarke, H.J.; Kljavin, N.; Zavala-Solorio, J.; Kates, L.; Friedman, B.; Brauer, M.; et al. Glucagon Couples Hepatic Amino Acid Catabolism to mTOR-Dependent Regulation of α-Cell Mass. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.; Liang, L.; Razquin, C.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; et al. High plasma glutamate and low glutamine-to-glutamate ratio are associated with type 2 diabetes: Case-cohort study within the PREDIMED trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, V.; Stütz, O.; Kinscherf, R.; Schykowski, M.; Kellerer, M.; Holm, E.; Dröge, W. Elevated venous glutamate levels in (pre)catabolic conditions result at least partly from a decreased glutamate transport activity. J. Mol. Med. 1996, 74, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butte, N.F.; Hsu, H.W.; Thotathuchery, M.; Wong, W.W.; Khoury, J.; Reeds, P. Protein metabolism in insulin-treated gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, S.; Marliss, E.B.; Morais, J.A.; Lamarche, M.; Gougeon, R. Whole-body protein anabolic response is resistant to the action of insulin in obese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.T.; Li, C.; Peng, X.P.; Guo, J.; Yue, S.J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, F.Y.; Han, J.Z.; Huang, Y.H.; Yang, L.; et al. An excessive increase in glutamate contributes to glucose-toxicity in β-cells via activation of pancreatic NMDA receptors in rodent diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.J.; Larson, M.G.; Vasan, R.S.; Cheng, S.; Rhee, E.P.; McCabe, E.; Lewis, G.D.; Fox, C.S.; Jacques, P.F.; Fernandez, C.; et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-S.; Xu, T.; Lee, Y.; Kim, N.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Cho, S.Y.; Kim, K.-Y.; Nam, M.; Adamski, J.; et al. Identification of putative biomarkers for type 2 diabetes using metabolomics in the Korea Association REsource (KARE) cohort. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Carli, F.; Rosso, C.; Buzzigoli, E.; Marietti, M.; Della Latta, V.; Ciociaro, D.; Abate, M.L.; Gambino, R.; Cassader, M.; et al. Altered amino acid concentrations in NAFLD: Impact of obesity and insulin resistance. Hepatology 2018, 67, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Bassot, A.; Bulteau, A.L.; Pirola, L.; Morio, B. Glycine Metabolism and Its Alterations in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Prado, W.L.; Josephson, S.; Cosentino, R.G.; Churilla, J.R.; Hossain, J.; Balagopal, P.B. Preliminary evidence of glycine as a biomarker of cardiovascular disease risk in children with obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2023, 47, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Oh, S.F.; Wada, S.; Rowe, G.C.; Liu, L.; Chan, M.C.; Rhee, J.; Hoshino, A.; Kim, B.; Ibrahim, A.; et al. A branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanand, S.; Vander Heiden, M.G. Emerging Roles for Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; McGarrah, R.W.; Herman, M.A.; Bain, J.R.; Shah, S.H.; Newgard, C.B. Insulin action, type 2 diabetes, and branched-chain amino acids: A two-way street. Mol. Metab. 2021, 52, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimou, A.; Tsimihodimos, V.; Bairaktari, E. The Critical Role of the Branched Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) Catabolism-Regulating Enzymes, Branched-Chain Aminotransferase (BCAT) and Branched-Chain alpha-Keto Acid Dehydrogenase (BCKD), in Human Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanweert, F.; Schrauwen, P.; Phielix, E. Role of branched-chain amino acid metabolism in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes-related metabolic disturbances BCAA metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, T.; Ohishi, T.; Matsui, T.; Saito, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Takasaki, J.; Matsumoto, S.; Kamohara, M.; Hiyama, H.; Yoshida, S.; et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion via an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 326, 744–751, Erratum in Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 329, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Sattler, R.; Yu, Z.; Herder, C.; Messias, A.C.; Floegel, A.; He, Y.; Heim, K.; Campillos, M.; Holzapfel, C.; Thorand, B.; et al. Novel biomarkers for pre-diabetes identified by metabolomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012, 8, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, J.M.; Kashyap, S.R.; Kasumov, T.; Zhang, R.; Kelly, K.R.; Defronzo, R.A.; Kirwan, J.P. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, P.J.; Summers, S.A. Sphingolipids and phospholipids in insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrac Barlovic, D.; Harjutsalo, V.; Sandholm, N.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P.H. Sphingomyelin and progression of renal and coronary heart disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quehenberger, O.; Armando, A.M.; Brown, A.H.; Milne, S.B.; Myers, D.S.; Merrill, A.H.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Jones, K.N.; Kelly, S.; Shaner, R.L.; et al. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 3299–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Sun, L.; Wu, Q.; Zong, G.; Qi, Q.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zeng, R.; Liang, L.; Lin, X. Associations among circulating sphingolipids, β-cell function, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes: A population-based cohort study in China. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geidl-Flueck, B.; Gerber, P.A. Insights into the Hexose Liver Metabolism-Glucose versus Fructose. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, K.L.; Schwarz, J.M.; Keim, N.L.; Griffen, S.C.; Bremer, A.A.; Graham, J.L.; Hatcher, B.; Cox, C.L.; Dyachenko, A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, H.-Y.; Fan, Z.-Y.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.-X. Metabolomics Signatures in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Integrative Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 105, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Horst, K.W.; Schene, M.R.; Holman, R.; Romijn, J.A.; Serlie, M.J. Effect of fructose consumption on insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diet-intervention trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1562–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Geng, F.; Hu, Z.H.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.Q.; Liu, J.C.; Qi, Y.H.; Li, L.J. Preliminary study of urine metabolism in type two diabetic patients based on GC-MS. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 2889–2896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Park, T.J.; Kim, J.M.; Yun, J.H.; Yu, H.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, B.J. Identification of metabolic markers predictive of prediabetes in a Korean population. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentzsch, P.; Witten, D.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D886–D894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, D.; Chen, Y.; Xie, X. DANN: A deep learning approach for annotating the pathogenicity of genetic variants. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, A.P.; Hong, E.L.; Hariharan, M.; Cheng, Y.; Schaub, M.A.; Kasowski, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Park, J.; Hitz, B.C.; Weng, S.; et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.B.; An, Y.R.; Kim, S.J.; Park, H.W.; Jung, J.W.; Kyung, J.S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S. Lipid metabolic effect of Korean red ginseng extract in mice fed on a high-fat diet. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Muller, C.; Schwedhelm, E.; Arunachalam, P.; Gelderblom, M.; Magnus, T.; Gerloff, C.; Zeller, T.; Choe, C.U. Homoarginine- and Creatine-Dependent Gene Regulation in Murine Brains with l-Arginine:Glycine Amidinotransferase Deficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sahra, I.; Manning, B.D. mTORC1 signaling and the metabolic control of cell growth. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 45, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Lamming, D.W. The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin: The Grand ConducTOR of Metabolism and Aging. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Richardson, N.E.; Green, C.L.; Spicer, A.B.; Murphy, M.E.; Flores, V.; Jang, C.; Kasza, I.; Nikodemova, M.; Wakai, M.H.; et al. The adverse metabolic effects of branched-chain amino acids are mediated by isoleucine and valine. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 905–922.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, S.G. Alanine to glycine ratio is a novel predictive biomarker for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 26, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollheim, C.B. Beta-cell mitochondria in the regulation of insulin secretion: A new culprit in type II diabetes. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felig, P.; Marliss, E.; Cahill, G.F., Jr. Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1969, 281, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marliss, E.B.; Gougeon, R. Editorial: Diabetes mellitus, lipidus et…proteinus! Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1474–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougeon, R.; Morais, J.A.; Chevalier, S.; Pereira, S.; Lamarche, M.; Marliss, E.B. Determinants of whole-body protein metabolism in subjects with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Marliss, E.B.; Morais, J.A.; Chevalier, S.; Gougeon, R. Insulin resistance of protein metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Su, M.; Jia, W.; Jia, W. Metabonomic variations in the drug-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and healthy volunteers. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davì, G.; Chiarelli, F.; Santilli, F.; Pomilio, M.; Vigneri, S.; Falco, A.; Basili, S.; Ciabattoni, G.; Patrono, C. Enhanced lipid peroxidation and platelet activation in the early phase of type 1 diabetes mellitus: Role of interleukin-6 and disease duration. Circulation 2003, 107, 3199–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Johansson, B.L.; Hjemdahl, P.; Li, N. Exercise-induced platelet and leucocyte activation is not enhanced in well-controlled Type 1 diabetes, despite increased activity at rest. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwdorp, M.; Stroes, E.S.; Meijers, J.C.; Büller, H. Hypercoagulability in the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005, 5, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfossi, G.; Russo, I.; Trovati, M. Platelet dysfunction in central obesity. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 19, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oresic, M.; Simell, S.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Näntö-Salonen, K.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Parikka, V.; Katajamaa, M.; Hekkala, A.; Mattila, I.; Keskinen, P.; et al. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, P.; Lewerenz, J.; Dittmer, S.; Noack, R.; Maher, P.; Methner, A. Mechanisms of oxidative glutamate toxicity: The glutamate/cystine antiporter system xc- as a neuroprotective drug target. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2010, 9, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Seino, Y. Regulation of amino acid metabolism and α-cell proliferation by glucagon. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 9, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Chantar, M.L.; Vazquez-Chantada, M.; Ariz, U.; Martinez, N.; Varela, M.; Luka, Z.; Capdevila, A.; Rodriguez, J.; Aransay, A.M.; Matthiesen, R.; et al. Loss of the glycine N-methyltransferase gene leads to steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Lapworth, A.L.; McGarrah, R.W.; Kwee, L.C.; Crown, S.B.; Ilkayeva, O.; An, J.; Carson, M.W.; Christopher, B.A.; Ball, J.R.; et al. Muscle-Liver Trafficking of BCAA-Derived Nitrogen Underlies Obesity-Related Glycine Depletion. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.C.; Hsu, J.W.; Tai, E.S.; Chacko, S.; Wu, V.; Lee, C.F.; Kovalik, J.P.; Jahoor, F. De Novo Glycine Synthesis Is Reduced in Adults With Morbid Obesity and Increases Following Bariatric Surgery. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 900343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Tran, P.O.; Harmon, J.; Robertson, R.P. A role for glutathione peroxidase in protecting pancreatic beta cells against oxidative stress in a model of glucose toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12363–12368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolenaar, W.H. LPA: A novel lipid mediator with diverse biological actions. Trends Cell Biol. 1994, 4, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, G.; Sandhya Rani, M.R.; Gerber, C.E.; Mukhopadhyay, C.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Chisolm, G.M.; Kottke-Marchant, K. Lysophosphatidylcholine regulates human microvascular endothelial cell expression of chemokines. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2003, 35, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Radu, C.G.; Yang, L.V.; Bentolila, L.A.; Riedinger, M.; Witte, O.N. Lysophosphatidylcholine-induced surface redistribution regulates signaling of the murine G protein-coupled receptor G2A. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 2234–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, W.L.; Knotts, T.A.; Chavez, J.A.; Wang, L.P.; Hoehn, K.L.; Summers, S.A. Lipid mediators of insulin resistance. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, S39–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppack, S.W.; Evans, R.D.; Fisher, R.M.; Frayn, K.N.; Gibbons, G.F.; Humphreys, S.M.; Kirk, M.L.; Potts, J.L.; Hockaday, T.D. Adipose tissue metabolism in obesity: Lipase action in vivo before and after a mixed meal. Metabolism 1992, 41, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, P.H.; Levak-Frank, S.; Hudgins, L.C.; Radner, H.; Friedman, J.M.; Zechner, R.; Breslow, J.L. Lipoprotein lipase controls fatty acid entry into adipose tissue, but fat mass is preserved by endogenous synthesis in mice deficient in adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 10261–10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Botolin, D.; Xu, J.; Christian, B.; Mitchell, E.; Jayaprakasam, B.; Nair, M.G.; Peters, J.M.; Busik, J.V.; Olson, L.K.; et al. Regulation of hepatic fatty acid elongase and desaturase expression in diabetes and obesity. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 2028–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigger, L.; Cruciani-Guglielmacci, C.; Nicolas, A.; Denom, J.; Fernandez, N.; Fumeron, F.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Ktorza, A.; Kramer, W.; Schulte, A.; et al. Plasma Dihydroceramides Are Diabetes Susceptibility Biomarker Candidates in Mice and Humans. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.; Parnham, M.J.; Geisslinger, G.; Schiffmann, S. Ceramides as Novel Disease Biomarkers. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Rütti, M.F.; Ernst, D.; Saely, C.H.; Rein, P.; Drexel, H.; Porretta-Serapiglia, C.; Lauria, G.; Bianchi, R.; von Eckardstein, A.; et al. Plasma deoxysphingolipids: A novel class of biomarkers for the metabolic syndrome? Diabetologia 2012, 55, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anroedh, S.; Hilvo, M.; Akkerhuis, K.M.; Kauhanen, D.; Koistinen, K.; Oemrawsingh, R.; Serruys, P.; van Geuns, R.J.; Boersma, E.; Laaksonen, R.; et al. Plasma concentrations of molecular lipid species predict long-term clinical outcome in coronary artery disease patients. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvo, M.; Salonurmi, T.; Havulinna, A.S.; Kauhanen, D.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tell, G.S.; Meyer, K.; Teeriniemi, A.M.; Laatikainen, T.; Jousilahti, P.; et al. Ceramide stearic to palmitic acid ratio predicts incident diabetes. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1424–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvo, M.; Meikle, P.J.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tell, G.S.; Dhar, I.; Brenner, H.; Schöttker, B.; Lääperi, M.; Kauhanen, D.; Koistinen, K.M.; et al. Development and validation of a ceramide- and phospholipid-based cardiovascular risk estimation score for coronary artery disease patients. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véret, J.; Coant, N.; Berdyshev, E.V.; Skobeleva, A.; Therville, N.; Bailbé, D.; Gorshkova, I.; Natarajan, V.; Portha, B.; Le Stunff, H. Ceramide synthase 4 and de novo production of ceramides with specific N-acyl chain lengths are involved in glucolipotoxicity-induced apoptosis of INS-1 β-cells. Biochem. J. 2011, 438, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boslem, E.; Meikle, P.J.; Biden, T.J. Roles of ceramide and sphingolipids in pancreatic β-cell function and dysfunction. Islets 2012, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boslem, E.; Weir, J.M.; MacIntosh, G.; Sue, N.; Cantley, J.; Meikle, P.J.; Biden, T.J. Alteration of endoplasmic reticulum lipid rafts contributes to lipotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26569–26582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véret, J.; Bellini, L.; Giussani, P.; Ng, C.; Magnan, C.; Le Stunff, H. Roles of Sphingolipid Metabolism in Pancreatic β Cell Dysfunction Induced by Lipotoxicity. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeituni, S.; Stiban, J. Roles of Ceramides and Other Sphingolipids in Immune Cell Function and Inflammation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1161, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.A.; Ha, H. Thr55 phosphorylation of p21 by MPK38/MELK ameliorates defects in glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in diet-induced obese mice. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ge, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, B.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, R.; Ai, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Teng, Y. MELK promotes Endometrial carcinoma progression via activating mTOR signaling pathway. eBIOMEDICINE 2020, 51, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.A.; Ha, H. Ablation of AMPK-Related Kinase MPK38/MELK Leads to Male-Specific Obesity in Aged Mature Adult Mice. Diabetes 2021, 70, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Lilly lecture 1987. The triumvirate: Beta-cell, muscle, liver. A collusion responsible for NIDDM. Diabetes 1988, 37, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defronzo, R.A. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2009, 58, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.C.; Pessin, J.E. Ins (endocytosis) and outs (exocytosis) of GLUT4 trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 476279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Lipina, C.; Petrie, J.R.; Murphy, M.J.; Morris, A.D.; Sutherland, C.; Cuthbertson, D.J. Obesity-induced insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle is characterised by defective activation of p42/p44 MAP kinase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

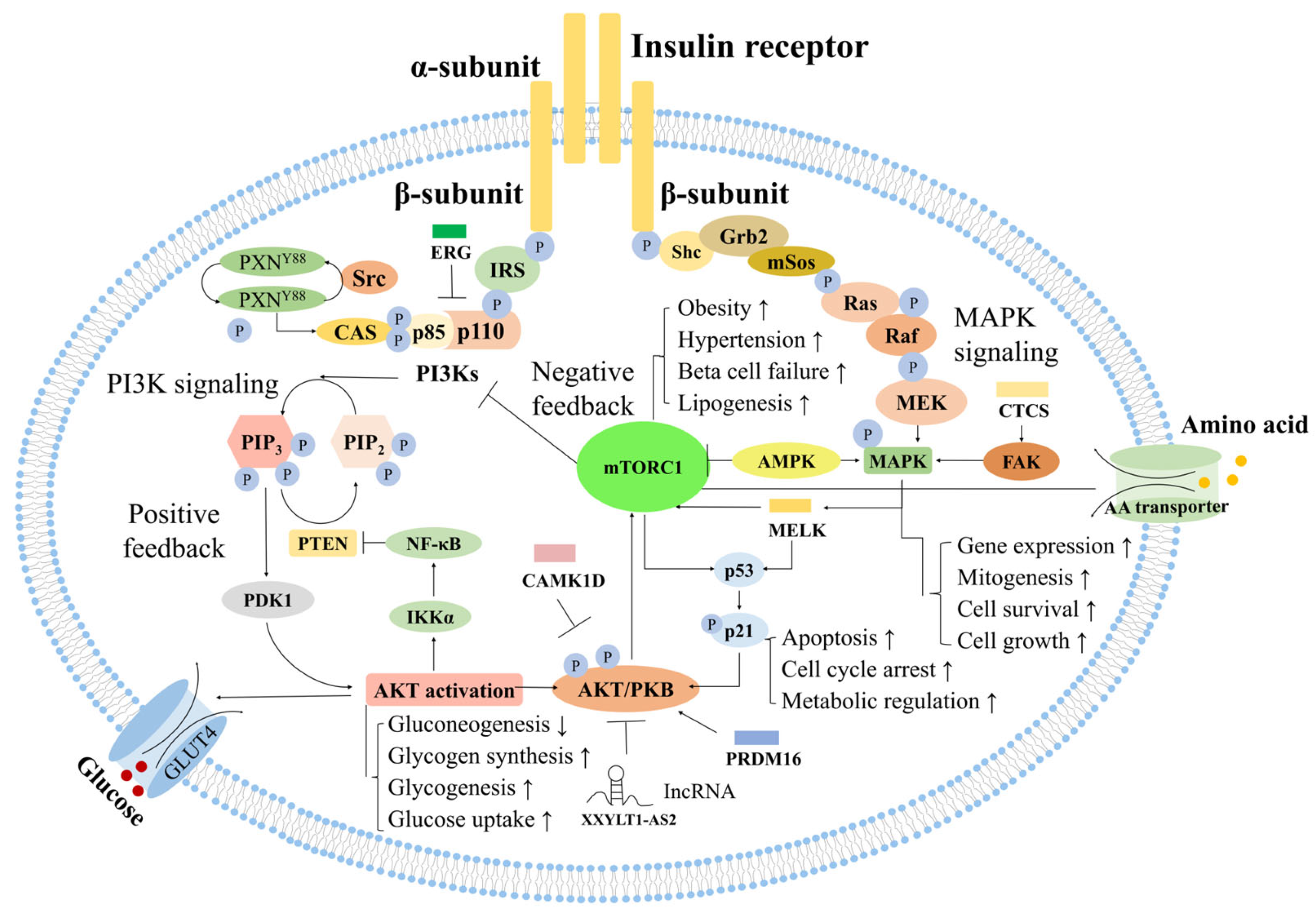

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newgard, C.B.; An, J.; Bain, J.R.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Stevens, R.D.; Lien, L.F.; Haqq, A.M.; Shah, S.H.; Arlotto, M.; Slentz, C.A.; et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.A. Ceramides in insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006, 45, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Hatch, G.M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, M. The relationship between phospholipids and insulin resistance: From clinical to experimental studies. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, B.G.; Ko, G.E.S.g. Cohort Profile: The Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwangbo, Y.; Kang, D.; Kang, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, E.K.; Kim, Y.A.; Chang, Y.J.; Choi, K.S.; Jung, S.Y.; Woo, S.M.; et al. Incidence of Diabetes After Cancer Development: A Korean National Cohort Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Nong, K.; Vandvik, P.O.; Guyatt, G.H.; Schnell, O.; Rydén, L.; Marx, N.; Brosius, F.C., 3rd; Mustafa, R.A.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Benefits and harms of drug treatment for type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2023, 381, e074068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.M.; Levy, J.C.; Matthews, D.R. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. S1), S17–S38. [CrossRef]

- Draznin, B.; Aroda, V.R.; Bakris, G.; Benson, G.; Brown, F.M.; Freeman, R.; Green, J.; Huang, E.; Isaacs, D.; Kahan, S.; et al. 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. S1), S244–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, S.; Hwang, M.Y.; Shin, D.M.; Park, M.Y.; Lu, Y.; Yoon, K.; Jang, H.M.; Kim, Y.K.; et al. The Korea Biobank Array: Design and Identification of Coding Variants Associated with Blood Biochemical Traits. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.J.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, B.J. Identification of novel non-synonymous variants associated with type 2 diabetes-related metabolites in Korean population. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.X.; Mondal, T.; Tabish, A.M.; Abadpour, S.; Ericson, E.; Smith, D.M.; Knöll, R.; Scholz, H.; Kanduri, C.; Tyrberg, B.; et al. The long noncoding RNA TUNAR modulates Wnt signaling and regulates human β-cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 320, E846–E857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Ji, H.; Ryu, D.; Cho, E.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Albizia julibrissin Exerts Anti-Obesity Effects by Inducing the Browning of 3T3L1 White Adipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kang, S.G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Dietary Supplementation of Methyl Cedryl Ether Ameliorates Adiposity in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xia, F.; Yu, J.; Sheng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, G. Distinct response of adipocyte progenitors to glucocorticoids determines visceral obesity via the TEAD1-miR-27b-PRDM16 axis. Obesity 2023, 31, 2335–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.C.; Soares, A.C.; Martins, F.F.; Resende, A.C.; Inada, K.O.P.; Souza-Mello, V.; Nunes, N.M.; Daleprane, J.B. Coffee consumption prevents obesity-related comorbidities and attenuates brown adipose tissue whitening in high-fat diet-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 117, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Eurotium cristatum from Fu Brick Tea Promotes Adipose Thermogenesis by Boosting Colonic Akkermansia muciniphila in High-Fat-Fed Obese Mice. Foods 2023, 12, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.O.; Ha, T.W.; Jung, H.U.; Lim, J.E.; Oh, B. A cardiac-null mutation of Prdm16 causes hypotension in mice with cardiac hypertrophy via increased nitric oxide synthase 1. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Belmonte, L.M.; Moreno-Santos, I.; Gómez-Doblas, J.J.; García-Pinilla, J.M.; Morcillo-Hidalgo, L.; Garrido-Sánchez, L.; Santiago-Fernández, C.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Carrasco-Chinchilla, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, P.L.; et al. Expression of epicardial adipose tissue thermogenic genes in patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction heart failure. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 14, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, Q.; Yao, Q.; Yu, J.; Jiang, K.; Wan, Y.; Tang, Q. PRDM16 exerts critical role in myocardial metabolism and energetics in type 2 diabetes induced cardiomyopathy. Metabolism 2023, 146, 155658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Zhu, Q.; Asteian, A.; Lin, H.; Xu, H.; Ernst, G.; Barrow, J.C.; Xu, B.; Cameron, M.D.; Kamenecka, T.M.; et al. TNP [N2-(m-Trifluorobenzyl), N6-(p-nitrobenzyl)purine] ameliorates diet induced obesity and insulin resistance via inhibition of the IP6K1 pathway. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, T.T.; Vu, V.V.; Pham, P.V. Transcriptional Factors of Thermogenic Adipocyte Development and Generation of Brown and Beige Adipocytes From Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 876–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Chen, S.; Zeng, G.; Yuan, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xiong, X.; Xu, B.; Huang, Q. Angiogenesis-Browning Interplay Mediated by Asprosin-Knockout Contributes to Weight Loss in Mice with Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Song, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Liang, L.; Zhao, J. Astragalus polysaccharide regulates brown adipocytes differentiation by miR-6911 targeting Prdm16. Lipids 2022, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradas-Juni, M.; Hansmeier, N.R.; Link, J.C.; Schmidt, E.; Larsen, B.D.; Klemm, P.; Meola, N.; Topel, H.; Loureiro, R.; Dhaouadi, I.; et al. A MAFG-lncRNA axis links systemic nutrient abundance to hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, A.; Tang, P.; et al. Gut microbiota induces DNA methylation via SCFAs predisposing obesity-prone individuals to diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 182, 106355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhu, K.; Zeng, P.; Ding, G. Dab1 Contributes to Angiotensin II-Induced Apoptosis via p38 Signaling Pathway in Podocytes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2484303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballif, B.A.; Arnaud, L.; Cooper, J.A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Disabled-1 is essential for Reelin-stimulated activation of Akt and Src family kinases. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003, 117, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gasperi, R.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; Wen, P.H.; Li, J.; Perez, G.M.; Curran, T.; Elder, G.A. Cortical development in the presenilin-1 null mutant mouse fails after splitting of the preplate and is not due to a failure of reelin-dependent signaling. Dev. Dyn. 2008, 237, 2405–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb, C.; Eresheim, C.; Nimpf, J. Clusterin is a ligand for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and signals via the Reelin-signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 4161–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, F.; Ma, H.; Xing, N.; Hou, L.; Du, Y.; Ding, H. Silencing of FOS-like antigen 1 represses restenosis via the ERK/AP-1 pathway in type 2 diabetic mice. Diab Vasc. Dis. Res. 2021, 18, 14791641211058855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jaber, H.; Mohamed, N.A.; Govindharajan, V.K.; Taha, S.; John, J.; Halim, S.; Alser, M.; Al-Muraikhy, S.; Anwardeen, N.R.; Agouni, A.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Validation of GATA-3 Suppression for Induction of Adipogenesis and Improving Insulin Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huda, N.; Hosen, M.I.; Yasmin, T.; Sarkar, P.K.; Hasan, A.; Nabi, A. Genetic variation of the transcription factor GATA3, not STAT4, is associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Bangladeshi population. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marampon, F.; Antinozzi, C.; Corinaldesi, C.; Vannelli, G.B.; Sarchielli, E.; Migliaccio, S.; Di Luigi, L.; Lenzi, A.; Crescioli, C. The phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor tadalafil regulates lipidic homeostasis in human skeletal muscle cell metabolism. Endocrine 2018, 59, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, F.; Tang, Y. CircDLGAP4 induces autophagy and improves endothelial cell dysfunction in atherosclerosis by targeting PTPN4 with miR-134-5p. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 2952–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppelreuther, M.; Lundsgaard, A.M.; Mensberg, P.; Sjøberg, K.; Vilsbøll, T.; Kiens, B.; Füllekrug, J. Acyl-CoA synthetase expression in human skeletal muscle is reduced in obesity and insulin resistance. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfín, D.A.; DeAguero, J.L.; McKown, E.N. The Extracellular Matrix Protein ABI3BP in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, I.H.; Longacre, M.J.; Stoker, S.W.; Kendrick, M.A.; O’Neill, L.M.; Zitur, L.J.; Fernandez, L.A.; Ntambi, J.M.; MacDonald, M.J. Characterization of Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms in pancreatic beta cells: Gene silencing shows participation of ACSL3 and ACSL4 in insulin secretion. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 618, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.S.; Grevengoed, T.J.; Pascual, F.; Ellis, J.M.; Willis, M.S.; Coleman, R.A. Deficiency of cardiac Acyl-CoA synthetase-1 induces diastolic dysfunction, but pathologic hypertrophy is reversed by rapamycin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkhani, S.; Marandi, S.M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Kim, S.K. Effects of Exercise Training and Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation On Hepatic Lipid Metabolism In Prediabetes Mice. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Gupta, A.; Sehgal, A.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Diaconu, C.C.; Rahdar, A.; Hafeez, A.; Bhatia, S.; et al. A spotlight on underlying the mechanism of AMPK in diabetes complications. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 70, 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Tajes, J.; Gaulton, K.J.; van de Bunt, M.; Torres, J.; Thurner, M.; Mahajan, A.; Gloyn, A.L.; Lage, K.; McCarthy, M.I. Developing a network view of type 2 diabetes risk pathways through integration of genetic, genomic and functional data. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Han, J.M.; Yu, X.; Lam, A.J.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Pesenacker, A.M.; Huang, Q.; Chen, V.; Speake, C.; Yorke, E.; et al. Characterization of regulatory T cells in obese omental adipose tissue in humans. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 49, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, J.; Cheng, Z. Regulation of the Proliferation of Diabetic Vascular Endothelial Cells by Degrading Endothelial Cell Functional Genes with QKI-7. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 6177809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, P.F.; Yu, T.; et al. Long noncoding RNA XXYLT1-AS2 regulates proliferation and adhesion by targeting the RNA binding protein FUS in HUVEC. Atherosclerosis 2020, 298, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacos, K.; Gillberg, L.; Volkov, P.; Olsson, A.H.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Gjesing, A.P.; Eiberg, H.; Tuomi, T.; Almgren, P.; et al. Blood-based biomarkers of age-associated epigenetic changes in human islets associate with insulin secretion and diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, T. TBCK influences cell proliferation, cell size and mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Jang, J.H.; Song, I.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Doh, K.O.; Lee, T.J. Suppression of TBCK enhances TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by causing the inactivation of the akt signaling pathway in human renal carcinoma Caki-1 cells. Genes Genom. 2023, 45, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.J.; Lim, H.X.; Song, J.H.; Lee, A.; Kim, E.; Cho, D.; Cohen, E.P.; Kim, T.S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-interacting multifunctional protein 1 suppresses tumor growth in breast cancer-bearing mice by negatively regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell functions. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Son, W.S.; Park, M.C.; Kim, C.M.; Cha, B.H.; Yoon, K.J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, S.G. ARS-interacting multi-functional protein 1 induces proliferation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by accumulation of β-catenin via fibroblast growth factor receptor 2-mediated activation of Akt. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Tian, L.; You, R.; Halpert, M.M.; Konduri, V.; Baig, Y.C.; Paust, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Jia, F.; et al. AIMp1 Potentiates T(H)1 Polarization and Is Critical for Effective Antitumor and Antiviral Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; Gu, C.; Gu, X.; Yang, Y. AIMP1 promotes multiple myeloma malignancy through interacting with ANP32A to mediate histone H3 acetylation. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 1185–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitfeld, J.; Kehr, S.; Müller, L.; Stadler, P.F.; Böttcher, Y.; Blüher, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kovacs, P. Developmentally Driven Changes in Adipogenesis in Different Fat Depots Are Related to Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Cao, X.F.; An, L.; Qiu, Y.; Du, M.; Ma, X.; et al. Exome sequencing reveals novel IRXI mutation in congenital heart disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 3193–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana, L.; Feng, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, P. Effect of Chinese herbal compound GAPT on the early brain glucose metabolism of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 2058738419841482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Ko, S.K.; Chung, S.H. Euonymus alatus prevents the hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia induced by high-fat diet in ICR mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 102, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citro, M.; Gadaleta, G.; Gamba Ansaldi, S.; Molinatti, M.; Salvetti, E.; Bruni, B. The HLA system and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A review and personal studies. Ann. Osp. Maria Vittoria Torino 1983, 26, 108–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noble, J.A.; Besançon, S.; Sidibé, A.T.; Rozemuller, E.H.; Rijkers, M.; Dadkhodaie, F.; de Bruin, H.; Kooij, J.; Martin, H.R.N.; Ogle, G.D.; et al. Complete HLA genotyping of type 1 diabetes patients and controls from Mali reveals both expected and novel disease associations. Hla 2024, 103, e15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, E.J.; Andreadis, E.A.; Kakou, M.G.; Vassilopoulos, C.V.; Vlachonikolis, I.G.; Gianna-Kopoulos, N.A.; Tarassi, K.E.; Papasteriades, C.A.; Nicolaides, A.N. Association of the HLA antigens with early atheromatosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. Angiol. 2002, 21, 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, V.; Zúñiga, J.; Azocar, J.; Clavijo, O.P.; Terreros, D.; Kidwai, H.; Pandey, J.P.; Yunis, E.J. Genetic interactions of KIR and G1M immunoglobulin allotypes differ in obese from non-obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 45, 3857–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.D.; Svejcar, J.; Kühnl, P.; Baur, M.P. HLA and obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1984, 38, 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hankir, M.K.; Kranz, M.; Gnad, T.; Weiner, J.; Wagner, S.; Deuther-Conrad, W.; Bronisch, F.; Steinhoff, K.; Luthardt, J.; Klöting, N.; et al. A novel thermoregulatory role for PDE10A in mouse and human adipocytes. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrocki, A.R.; Rodriguez, C.G.; Toolan, D.M.; Price, O.; Henry, M.; Forrest, G.; Szeto, D.; Keohane, C.A.; Pan, Y.; Smith, K.M.; et al. Genetic deletion and pharmacological inhibition of phosphodiesterase 10A protects mice from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2014, 63, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, B.; Banke, E.; Ekelund, M.; Frederiksen, S.; Degerman, E. Alterations in cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activities in omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues in human obesity. Nutr. Diabetes 2011, 1, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Wainstein, J.; Tsameret, S.; Landau, Z. Role of High Energy Breakfast “Big Breakfast Diet” in Clock Gene Regulation of Postprandial Hyperglycemia and Weight Loss in Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterman, J.E.; Wopereis, S.; Kalsbeek, A. The Circadian Clock, Shift Work, and Tissue-Specific Insulin Resistance. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claycombe-Larson, K.J.; Bundy, A.; Lance, E.B.; Darland, D.C.; Casperson, S.L.; Roemmich, J.N. Postnatal exercise protects offspring from high-fat diet-induced reductions in subcutaneous adipocyte beiging in C57Bl6/J mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 99, 108853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizcano, F.; Romero, C.; Vargas, D. Regulation of adipogenesis by nuclear receptor PPARγ is modulated by the histone demethylase JMJD2C. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2011, 34, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y.; Wang, B.J.; Chen, B.C.; Tseng, J.C.; Jiang, S.S.; Tsai, K.K.; Shen, Y.Y.; Yuh, C.H.; Sie, Z.L.; Wang, W.C.; et al. Histone Demethylase KDM4C Stimulates the Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells via Activation of AKT and c-Myc. Cancers 2019, 11, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.A.; Manoharan, R.; Ha, H. Smad proteins differentially regulate obesity-induced glucose and lipid abnormalities and inflammation via class-specific control of AMPK-related kinase MPK38/MELK activity. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.A.; Manoharan, R.; Ha, H. DAXX ameliorates metabolic dysfunction in mice with diet-induced obesity by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase-related kinase MPK38/MELK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 572, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, H.A.; Jung, H.; Ha, H. Murine protein serine/threonine kinase 38 stimulates TGF-beta signaling in a kinase-dependent manner via direct phosphorylation of Smad proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 30959–30970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, S.; Zhao, J.; Tiwari, S.; Eng, K.; Guey, L.T.; Tien, E. RNAi screening in primary human hepatocytes of genes implicated in genome-wide association studies for roles in type 2 diabetes identifies roles for CAMK1D and CDKAL1, among others, in hepatic glucose regulation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromont, C.; Atzori, A.; Kaur, D.; Hashmi, L.; Greco, G.; Cabanillas, A.; Nguyen, H.V.; Jones, D.H.; Garzón, M.; Varela, A.; et al. Discovery of Highly Selective Inhibitors of Calmodulin-Dependent Kinases That Restore Insulin Sensitivity in the Diet-Induced Obesity in Vivo Mouse Model. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6784–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, L.; Zeng, T.; Wang, W.; Yan, Y.; Qiu, K.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Y. DNA methylation profiling reveals novel pathway implicated in cardiovascular diseases of diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Z.; Shi, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z. CAMK1D Inhibits Glioma Through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 845036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo Martínez, M.; Ritsvall, O.; Bastrup, J.A.; Celik, S.; Jakobsson, G.; Daoud, F.; Winqvist, C.; Aspberg, A.; Rippe, C.; Maegdefessel, L.; et al. Vascular smooth muscle-specific YAP/TAZ deletion triggers aneurysm development in mouse aorta. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e170845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Qi, F.; Zheng, S.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, J. Fibroblast-Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 Mediates Extracellular Matrix Deposition and Inhibits Smooth Muscle Cell Contractility in Marfan Syndrome Aortic Aneurysm. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, K.; Herlan, L.; Witten, A.; Qadri, F.; Eisenreich, A.; Lindner, D.; Schädlich, M.; Schulz, A.; Subrova, J.; Mhatre, K.N.; et al. Cpxm2 as a novel candidate for cardiac hypertrophy and failure in hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2022, 45, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrova, J.; Böhme, K.; Gillespie, A.; Orphal, M.; Plum, C.; Kreutz, R.; Eisenreich, A. MiRNA-29b and miRNA-497 Modulate the Expression of Carboxypeptidase X Member 2, a Candidate Gene Associated with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, L.; Huang, Y. miR-107 inhibited malignant biological behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells by regulating the STK33/ERK signaling pathway in vivo and vitro. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xiang, J.; Zhan, C.; Liu, J.; Yan, S. STK33 Promotes the Growth and Progression of Human Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumour via Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyel, T.; Frorup, C.; Storling, J.; Pociot, F. Cathepsin C Regulates Cytokine-Induced Apoptosis in beta-Cell Model Systems. Genes 2021, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Florido, A.; Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Altmae, S.; Ortega, F.B.; Esteban-Cornejo, I. Cardiorespiratory fitness and targeted proteomics involved in brain and cardiovascular health in children with overweight/obesity. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2023, 23, 2076–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, G.; Fan, K.; Ma, J. Up-regulated cathepsin C induces macrophage M1 polarization through FAK-triggered p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 382, 111472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; An, Y.; Xia, B.; Wan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J. Cathepsin C Is Involved in Macrophage M1 Polarization via p38/MAPK Pathway in Sudden Cardiac Death. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2021, 2021, 6139732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.K.; Bayliss, J.; Devereux, C.; Bezawork-Geleta, A.; Roberts, D.; Huang, C.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Ryan, A.; Townley, S.L.; Selth, L.A.; et al. SMOC1 is a glucose-responsive hepatokine and therapeutic target for glycemic control. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaaz8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Balasubramanian, S.; Dhawan, S.; Leung, A.; Chen, Z.; Natarajan, R. Integrative Omics Analyses Reveal Epigenetic Memory in Diabetic Renal Cells Regulating Genes Associated with Kidney Dysfunction. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2490–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, M.; Baltzer, N.; Pan, G.; Bárcenas Walls, J.R.; Smolinska Garbulowska, K.; Kumar, C.; Skrtic, S.; Komorowski, J.; Wadelius, C. Studies of liver tissue identify functional gene regulatory elements associated to gene expression, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic diseases. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Qiu, X.; Pan, R.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Wu, Q.Q.; Pan, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Dietary intervention preserves β cell function in mice through CTCF-mediated transcriptional reprogramming. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20211779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Seibert, O.; Kloting, N.; Dietrich, A.; Strassburger, K.; Fernandez-Veledo, S.; Vendrell, J.J.; Zorzano, A.; Bluher, M.; Herzig, S.; et al. PPP2R5C Couples Hepatic Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematullah, M.; Rashid, F.; Nimker, S.; Khan, F. Protein Phosphatase 2A Regulates Phenotypic and Metabolic Alteration of Microglia Cells in HFD-Associated Vascular Dementia Mice via TNF-alpha/Arg-1 Axis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 4049–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Shen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C.; Cao, C.; Yang, L.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Li, B.; Li, Y. Alteration of gene expression profile following PPP2R5C knockdown may be associated with proliferation suppression and increased apoptosis of K562 cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deursen, D.; Jansen, H.; Verhoeven, A.J. Glucose increases hepatic lipase expression in HepG2 liver cells through upregulation of upstream stimulatory factors 1 and 2. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijk, W.; Di Filippo, M.; Kooijman, S.; van Eenige, R.; Rimbert, A.; Caillaud, A.; Thedrez, A.; Arnaud, L.; Pronk, A.; Garcon, D.; et al. Identification of a Gain-of-Function LIPC Variant as a Novel Cause of Familial Combined Hypocholesterolemia. Circulation 2022, 146, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, K.; Chakraborty, R.; Boerwinkle, E.A. Ionizing radiation and genetic risks. VI. Chronic multifactorial diseases: A review of epidemiological and genetical aspects of coronary heart disease, essential hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Mutat. Res. 1999, 436, 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenta, G.; Berg, G.; Arias, P.; Zago, V.; Schnitman, M.; Muzzio, M.L.; Sinay, I.; Schreier, L. Lipoprotein alterations, hepatic lipase activity, and insulin sensitivity in subclinical hypothyroidism: Response to L-T(4) treatment. Thyroid 2007, 17, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Palaia, T.; Ragolia, L. Impaired insulin-stimulated myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein signaling in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012, 302, C1371–C1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Yang, S.X.; Ye, F.; Xia, X.P.; Shao, X.X.; Xia, S.L.; Zheng, B.; Xu, C.L. Hypoxia-induced Rab11-family interacting protein 4 expression promotes migration and invasion of colon cancer and correlates with poor prognosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, P.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, F. Diet-induced obese alters the expression and function of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 164, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Frano, M.R.; Hernandez-Carretero, A.; Weber, N.; Borkowski, K.; Pedersen, T.L.; Osborn, O.; Newman, J.W. Diet-induced obesity and weight loss alter bile acid concentrations and bile acid-sensitive gene expression in insulin target tissues of C57BL/6J mice. Nutr. Res. 2017, 46, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Shlomo, S.; Zvibel, I.; Rabinowich, L.; Goldiner, I.; Shlomai, A.; Santo, E.M.; Halpern, Z.; Oren, R.; Fishman, S. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4-deficient rats have improved bile secretory function in high fat diet-induced steatosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, S.; Daneshvar, K.; Roy, L.D.; Grover, P.; Kidiyoor, A.; Mosley, L.; Sahraei, M.; Mukherjee, P. MUC1 induces drug resistance in pancreatic cancer cells via upregulation of multidrug resistance genes. Oncogenesis 2013, 2, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessina, S.; Cantini, G.; Kapetis, D.; Cazzato, E.; Di Ianni, N.; Finocchiaro, G.; Pellegatta, S. The multidrug-resistance transporter Abcc3 protects NK cells from chemotherapy in a murine model of malignant glioma. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, N.E.; Lambert, W.M.; Watkins, R.; Giashuddin, S.; Huang, S.J.; Oxelmark, E.; Arju, R.; Hochman, T.; Goldberg, J.D.; Schneider, R.J.; et al. High levels of Hsp90 cochaperone p23 promote tumor progression and poor prognosis in breast cancer by increasing lymph node metastases and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8446–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaran, M.; Behmand, M.J.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Mosaddeghi-Heris, R.; Ahmadi, M.; Rezaie, J. High-fat diet-induced biogenesis of pulmonary exosomes in an experimental rat model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 7589–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ye, X.; Sun, L.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X. Downregulation of serum RAB27B confers improved prognosis and is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression through PI3K-AKT-P21 signaling. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 61118–61132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, B.G.; Jelinek, J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, K.; Rha, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Jin, H.S.; Choi, D.K.; et al. Promoter methylation changes in ALOX12 and AIRE1: Novel epigenetic markers for atherosclerosis. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Zhu, R.; Jia, Z.; Ban, J.; Zhen, R.; Chen, X.; Pan, X.; Ren, Q.; et al. Effect of semaglutide and empagliflozin on cognitive function and hippocampal phosphoproteomic in obese mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 975830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, S.Q.Z.; Loh, K.W.Z.; Soong, T.W. Calcium Channel Splice Variants and Their Effects in Brain and Cardiovascular Function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1349, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nandula, S.R.; Huxford, I.; Wheeler, T.T.; Aparicio, C.; Gorr, S.U. The parotid secretory protein BPIFA2 is a salivary surfactant that affects lipopolysaccharide action. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Scott, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Doerner, S.; Satake, M.; Croniger, C.M.; Wang, Z. PTPRT regulates high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbers, L.; Luedeke, M.; Rinckleb, A.; Kolb, S.; Wright, J.L.; Maier, C.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Stanford, J.L. Obesity and Prostate Cancer Risk According to Tumor TMPRSS2:ERG Gene Fusion Status. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 181, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, C.M.; Gurley, J.M.; Kurylowicz, K.; Lin, P.K.; Chen, W.; Elliott, M.H.; Davis, G.E.; Bhatti, F.; Griffin, C.T. An inhibitor of endothelial ETS transcription factors promotes physiologic and therapeutic vessel regression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26494–26502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.; Shi, L.; Huang, C.C.; Kim, A.J.; Ko, M.L.; Zhou, B.; Ko, G.Y. High-Fat Diet-Induced Retinal Dysfunction. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 2367–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Gao, D.; Hu, W.; Gadal, S.; Hieronymus, H.; Wang, S.; Lee, Y.S.; Sullivan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Choi, D.; et al. Oncogenic ERG Represses PI3K Signaling through Downregulation of IRS2. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Song, G.; Ming, Q.; Ma, X.; Yang, J.; Deng, S.; Wen, Y.; et al. Antidiabetic Activity of Ergosterol from Pleurotus Ostreatus in KK-A(y) Mice with Spontaneous Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) Status Based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Criteria | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Glucose Tolerance (NGT) (n = 747) | Prediabetes (PD) (n = 736) | T2D (n = 336) | ||

| SEX | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 316 (42.30%) | 357 (48.51%) | 204 (60.71%) | |

| Female | 431 (57.70%) | 379 (51.49%) | 132 (39.29%) | |

| AGE (years) a | 54.94 ± 8.56 | 57.47 ± 8.90 | 56.60 ± 8.64 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) b | 23.59 ± 2.96 | 25.14 ± 3.21 | 25.35 ± 2.99 | <0.0001 |

| HDL c | 45.37 ± 10.22 | 43.02 ± 9.51 | 42.07 ± 9.93 | <0.0001 |

| LDL d | 118.73 ± 30.10 | 122.61 ± 34.55 | 123.35 ± 35.63 | 0.031 |

| TG e | 113.51 ± 64.55 | 161.89 ± 144.66 | 179.47 ± 131.38 | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c f | 5.23 ± 0.24 | 5.72 ± 0.32 | 6.38 ± 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| FPG g | 83.74 ± 5.32 | 97.47 ± 9.84 | 115.82 ± 29.18 | <0.0001 |

| 2h-PG h | 93.79 ± 18.32 | 138.99 ± 33.95 | 238.50 ± 58.22 | <0.0001 |

| INSO i | 6.82 ± 2.97 | 8.20 ± 3.59 | 8.20 ± 3.62 | <0.0001 |

| TCHL j | 186.80 ± 32.55 | 198.01 ± 36.20 | 201.31 ± 35.31 | <0.0001 |

| HOMA_IR k | 1.42 ± 0.65 | 1.99 ± 0.93 | 2.38 ± 1.26 | <0.0001 |

| Metabolite | Linear Regression Beta | Baseline-Category Logistic Regression Odds Ratio (OR)—95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Ref. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu0 | Glu120 | HbA1c | HOMA-IR | Criteria by ADA | Criteria by HbA1c | Six Subgroups (G6) | ||||||||

| PD | T2D | PD | T2D | IFG | IGT | IFG+IGT | IFG+T2D | T2D | ||||||

| Alanine | 3.546 | 11.084 | 0.104 | 0.183 | 1.623 (1.44–1.83) | 1.742 (1.50–2.02) | 1.432 (1.28–1.60) | 1.690 (1.370–2.08) | 1.733 (1.46–2.07) | 1.338 (1.15–1.56) | 1.641 (1.36–1.98) | 1.704 (1.38–2.11) | 1.790 (1.49–2.15) | [23,24,25,26] |

| Glutamine | −2.895 | −5.019 | −0.065 | −0.078 | 1.181 (1.04–1.34) | 0.825 (0.73–0.94) | 1.152 (1.02–1.30) | 0.723 (0.62–0.85) | 0.958 (0.81–1.13) | 1.312 (1.10–1.56) | 0.885 (0.75–1.05) | 0.869 (0.72–1.04) | 0.809 (0.70–0.94) | [27,28,29,30] |

| Glutamate | 2.025 | 7.377 | 0.082 | 0.112 | 1.317 (1.17–1.48) | 1.492 (1.30–1.72) | 1.169 (1.05–1.31) | 1.477 (1.23–1.77) | 1.283 (1.09–1.51) | 1.065 (0.91–1.25) | 1.130 (0.94–1.35) | 1.199 (0.98–1.47) | 1.544 (1.32–1.81) | [31,32,33,34] |

| Glycine | −3.179 | −13.062 | −0.096 | −0.107 | 0.771 (0.69–0.86) | 0.490 (0.42–0.58) | 0.802 (0.72–0.90) | 0.579 (0.47–0.72) | 0.728 (0.61–0.87) | 0.747 (0.64–0.87) | 0.677 (0.56–0.82) | 0.493 (0.39–0.62) | 0.488 (0.40–0.60) | [35,36,37,38,39] |

| Proline | 1.312 | 3.750 | 0.039 | 0.124 | 1.371 (1.22–1.54) | 1.228 (1.06–1.42) | 1.247 (1.12–1.39) | 1.179 (0.97–1.44) | 1.372 (1.17–1.62) | 1.345 (1.16–1.56) | 1.236 (1.03–1.48) | 1.161 (0.95–1.43) | 1.218 (1.02–1.45) | - |

| Valine | 2.069 | 10.079 | 0.089 | 0.137 | 1.593 (1.41–1.80) | 1.504 (1.29–1.75) | 1.412 (1.26–1.59) | 1.446 (1.17–1.79) | 1.317 (1.10–1.58) | 1.503 (1.28–1.76) | 1.359 (1.12–1.65) | 1.223 (0.98–1.52) | 1.604 (1.33–1.94) | [40,41,42,43,44] |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine acyl C17:0 | −1.337 | −9.621 | −0.085 | −0.070 | 0.887 (0.80–0.99) | 0.615 (0.53–0.71) | 0.841 (0.76–0.94) | 0.645 (0.53–0.79) | 1.063 (0.91–1.25) | 0.814 (0.70–0.94) | 0.874 (0.74–1.04) | 0.593 (0.48–0.73) | 0.668 (0.56–0.80) | - |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine acyl C18:2 | −2.244 | −13.128 | −0.087 | −0.082 | 0.768 (0.68–0.87) | 0.552 (0.47–0.64) | 0.787 (0.70–0.88) | 0.574 (0.47–0.71) | 0.946 (0.79–1.13) | 0.748 (0.64–0.88) | 0.601 (0.50–0.73) | 0.586 (0.47–0.73) | 0.564 (0.47–0.68) | [18,45,46] |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C30:2 | 1.106 | 3.578 | 0.063 | 0.113 | 1.029 (0.92–1.15) | 1.269 (1.11–1.45) | 1.148 (1.03–1.28) | 1.495 (1.25–1.79) | 1.049 (0.89–1.24) | 0.970 (0.83–1.13) | 0.974 (0.82–1.16) | 1.073 (0.88–1.31) | 1.392 (1.19–1.63) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C32:1 | 1.238 | 5.771 | 0.083 | 0.123 | 1.187 (1.06–1.33) | 1.423 (1.24–1.64) | 1.288 (1.16–1.44) | 1.534 (1.28–1.85) | 1.118 (0.95–1.32) | 1.215 (1.05–1.41) | 1.153 (0.97–1.38) | 1.170 (0.96–1.43) | 1.542 (1.31–1.82) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C34:1 | 2.302 | 8.975 | 0.110 | 0.139 | 1.376 (1.23–1.55) | 1.771 (1.53–2.05) | 1.476 (1.32–1.65) | 1.819 (1.51–2.20) | 1.349 (1.14–1.60) | 1.295 (1.11–1.51) | 1.305 (1.09–1.56) | 1.436 (1.17–1.76) | 1.957 (1.65–2.32) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C34:2 | 2.364 | 8.378 | 0.112 | 0.139 | 1.256 (1.12–1.41) | 1.749 (1.51–2.02) | 1.364 (1.22–1.52) | 1.873 (1.55–2.27) | 1.449 (1.22–1.71) | 1.199 (1.03–1.39) | 1.089 (0.91–1.30) | 1.526 (1.25–1.87) | 1.838 (1.54–2.19) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C34:4 | 2.406 | 4.157 | 0.076 | 0.127 | 1.331 (1.19–1.49) | 1.359 (1.18–1.57) | 1.241 (1.11–1.38) | 1.357 (1.13–1.64) | 1.585 (1.35–1.86) | 1.116 (0.96–1.30) | 1.396 (1.17–1.66) | 1.156 (0.94–1.42) | 1.409 (1.19–1.67) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C36:1 | 1.574 | 5.092 | 0.085 | 0.131 | 1.363 (1.22–1.53) | 1.473 (1.28–1.70) | 1.411 (1.27–1.57) | 1.526 (1.27–1.84) | 1.339 (1.14–1.58) | 1.308 (1.13–1.51) | 1.196 (1.00–1.43) | 1.241 (1.02–1.52) | 1.558 (1.32–1.84) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C36:2 | 1.666 | 3.662 | 0.072 | 0.125 | 1.231 (1.10–1.38) | 1.445 (1.26–1.66) | 1.266 (1.14–1.41) | 1.479 (1.23–1.78) | 1.498 (1.27–1.77) | 1.156 (1.00–1.34) | 1.041 (0.87–1.24) | 1.302 (1.07–1.59) | 1.484 (1.25–1.76) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C36:4 | 2.392 | 5.926 | 0.080 | 0.108 | 1.229 (1.10–1.38) | 1.457 (1.26–1.68) | 1.185 (1.06–1.32) | 1.477 (1.22–1.79) | 1.393 (1.18–1.65) | 0.999 (0.86–1.16) | 1.253 (1.05–1.50) | 1.266 (1.03–1.55) | 1.567 (1.32–1.86) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C36:5 | 3.313 | 9.998 | 0.083 | 0.152 | 1.456 (1.30–1.63) | 1.726 (1.49–2.00) | 1.221 (1.10–1.36) | 1.568 (1.28–1.92) | 1.639 (1.38–1.94) | 1.178 (1.01–1.37) | 1.642 (1.37–1.97) | 1.538 (1.25–1.89) | 1.911 (1.59–2.30) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C38:5 | 2.789 | 7.325 | 0.073 | 0.138 | 1.421 (1.27–1.59) | 1.589 (1.38–1.83) | 1.206 (1.08–1.34) | 1.473 (1.21–1.79) | 1.587 (1.34–1.88) | 1.129 (0.97–1.31) | 1.522 (1.27–1.82) | 1.396 (1.14–1.71) | 1.716 (1.44–2.05) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C38:6 | 2.493 | 11.166 | 0.068 | 0.100 | 1.314 (1.17–1.47) | 1.723 (1.49–2.00) | 1.231 (1.10–1.37) | 1.563 (1.28–1.91) | 1.349 (1.14–1.60) | 1.236 (1.06–1.44) | 1.349 (1.13–1.62) | 1.579 (1.28–1.95) | 2.066 (1.72–2.48) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C40:5 | 1.570 | 5.209 | 0.063 | 0.101 | 1.336 (1.19–1.49) | 1.360 (1.18–1.57) | 1.260 (1.13–1.40) | 1.378 (1.14–1.67) | 1.278 (1.08–1.51) | 1.201 (1.04–1.39) | 1.386 (1.16–1.66) | 1.205 (0.98–1.48) | 1.444 (1.22–1.72) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C40:6 | 1.273 | 7.090 | 0.038 | 0.088 | 1.212 (1.09–1.35) | 1.398 (1.22–1.67) | 1.189 (1.07–1.32) | 1.287 (1.06–1.56) | 1.152 (0.98–1.36) | 1.240 (1.07–1.44) | 1.167 (0.98–1.39) | 1.387 (1.13–1.70) | 1.532 (1.29–1.82) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C42:0 | −1.917 | −7.155 | −0.074 | −0.055 | 0.644 (0.57–0.73) | 0.666 (0.57–0.77) | 0.701 (0.62–0.79) | 0.761 (0.61–0.94) | 0.669 (0.56–0.80) | 0.614 (0.52–0.73) | 0.705 (0.58–0.85) | 0.623 (0.50–0.78) | 0.791 (0.66–0.95) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C42:1 | −1.989 | −7.005 | −0.077 | −0.076 | 0.657 (0.58–0.74) | 0.675 (0.58–0.79) | 0.725 (0.65–0.81) | 0.763 (0.61–0.95) | 0.676 (0.57–0.81) | 0.650 (0.55–0.77) | 0.687 (0.57–0.83) | 0.660 (0.53–0.83) | 0.763 (0.63–0.92) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine diacyl C42:5 | 2.007 | 5.350 | 0.039 | 0.130 | 1.202 (1.07–1.35) | 1.399 (1.22–1.60) | 1.065 (0.96–1.18) | 1.364 (1.15–1.62) | 1.312 (1.12–1.53) | 1.067 (0.92–1.25) | 1.277 (1.08–1.51) | 1.313 (1.09–1.59) | 1.491 (1.28–1.74) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C34:3 | −3.095 | −11.585 | −0.066 | −0.103 | 0.646 (0.57–0.74) | 0.624 (0.53–0.74) | 0.813 (0.72–0.92) | 0.832 (0.67–1.04) | 0.692 (0.57–0.84) | 0.656 (0.55–0.78) | 0.477 (0.38–0.59) | 0.596 (0.47–0.76) | 0.670 (0.55–0.82) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C40:3 | −1.369 | −4.267 | −0.038 | −0.061 | 0.728 (0.65–0.82) | 0.881 (0.76–1.02) | 0.840 (0.75–0.94) | 0.995 (0.81–1.22) | 0.761 (0.64–0.91) | 0.671 (0.57–0.79) | 0.732 (0.60–0.89) | 0.800 (0.65–0.99) | 0.975 (0.82–1.16) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C40:5 | 2.229 | 5.218 | 0.041 | 0.089 | 1.219 (1.08–1.37) | 1.384 (1.19–1.61) | 1.143 (1.02–1.28) | 1.284 (1.05–1.58) | 1.457 (1.22–1.74) | 0.950 (0.81–1.12) | 1.355 (1.12–1.63) | 1.248 (1.01–1.55) | 1.618 (1.35–1.94) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C42:1 | −2.046 | −9.762 | −0.076 | −0.095 | 0.687 (0.61–0.78) | 0.671 (0.57–0.78) | 0.734 (0.65–0.83) | 0.746 (0.60–0.93) | 0.759 (0.64–0.91) | 0.652 (0.55–0.77) | 0.664 (0.54–0.81) | 0.635 (0.50–0.80) | 0.711 (0.59–0.86) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C42:4 | −2.318 | −8.109 | −0.057 | −0.098 | 0.648 (0.58–0.73) | 0.658 (0.57–0.77) | 0.774 (0.69–0.87) | 0.844 (0.68–1.04) | 0.632 (0.53–0.76) | 0.613 (0.52–0.73) | 0.657 (0.54–0.80) | 0.616 (0.49–0.77) | 0.741 (0.62–0.89) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C44:4 | −2.876 | −8.058 | −0.075 | −0.101 | 0.667 (0.59–0.75) | 0.618 (0.53–0.72) | 0.747 (0.67–0.84) | 0.757 (0.61–0.94) | 0.580 (0.48–0.70) | 0.690 (0.59–0.81) | 0.651 (0.53–0.79) | 0.541 (0.43–0.68) | 0.713 (0.59–0.86) | - |

| Phosphatidylcholine acyl–alkyl C44:6 | −2.425 | −9.002 | −0.078 | −0.082 | 0.606 (0.54–0.68) | 0.587 (0.50–0.69) | 0.691 (0.62–0.78) | 0.728 (0.59–0.91) | 0.590 (0.49–0.71) | 0.603 (0.51–0.71) | 0.652 (0.54–0.79) | 0.522 (0.42–0.66) | 0.681 (0.57–0.82) | - |

| Hydroxysphingomyeline C14:1 | −2.901 | −7.242 | −0.068 | −0.100 | 0.727 (0.65–0.82) | 0.645 (0.56–0.75) | 0.887 (0.79–0.99) | 0.772 (0.63–0.95) | 0.649 (0.55–0.77) | 0.800 (0.68–0.94) | 0.630 (0.52–0.76) | 0.636 (0.51–0.79) | 0.690 (0.57–0.83) | - |

| Hydroxysphingomyeline C16:1 | −2.607 | −7.032 | −0.062 | −0.084 | 0.777 (0.69–0.87) | 0.636 (0.55–0.74) | 0.950 (0.85–1.06) | 0.764 (0.62–0.94) | 0.676 (0.57–0.81) | 0.841 (0.72–0.99) | 0.682 (0.57–0.82) | 0.627 (0.51–0.77) | 0.687 (0.57–0.82) | - |

| Hydroxysphingomyeline C22:2 | −4.245 | −12.596 | −0.109 | −0.159 | 0.599 (0.52–0.69) | 0.451 (0.38–0.54) | 0.758 (0.67–0.86) | 0.579 (0.46–0.73) | 0.489 (0.40–0.60) | 0.649 (0.54–0.78) | 0.501 (0.41–0.62) | 0.510 (0.40–0.65) | 0.442 (0.36–0.54) | - |

| Sphingomyeline C16:0 | −2.944 | −10.466 | −0.056 | −0.127 | 0.671 (0.59–0.76) | 0.567 (0.49–0.66) | 0.862 (0.77–0.97) | 0.822 (0.67–1.01) | 0.611 (0.51–0.73) | 0.652 (0.55–0.77) | 0.532 (0.44–0.65) | 0.505 (0.41–0.63) | 0.623 (0.52–0.75) | [47,48,49,50,51] |

| Sphingomyeline C16:1 | −3.564 | −10.665 | −0.068 | −0.127 | 0.685 (0.60–0.78) | 0.5560 (0.47–0.66) | 0.865 (0.77–0.98) | 0.759 (0.61–0.95) | 0.582 (0.48–0.71) | 0.712 (0.60–0.85) | 0.519 (0.42–0.64) | 0.532 (0.42–0.68) | 0.578 (0.47–0.71) | - |

| Sphingomyeline C18:1 | −2.891 | −4.906 | −0.043 | −0.091 | 0.784 (0.69–0.89) | 0.640 (0.55–0.75) | 0.966 (0.86–1.09) | 0.769 (0.62–0.95) | 0.561 (0.47–0.68) | 0.881 (0.75–1.04) | 0.663 (0.54–0.81) | 0.688 (0.55–0.86) | 0.672 (0.55–0.82) | - |

| Sphingomyeline C24:1 | −2.231 | −7.499 | −0.069 | −0.095 | 0.693 (0.62–0.78) | 0.647 (0.56–0.75) | 0.805 (0.72–0.90) | 0.749 (0.62–0.91) | 0.662 (0.56–0.79) | 0.616 (0.53–0.72) | 0.639 (0.53–0.77) | 0.690 (0.56–0.85) | 0.676 (0.57–0.81) | - |

| Hexose | 13.101 | 32.126 | 0.338 | 0.360 | 1.916 (1.64–2.24) | 7.566 (6.04–9.48) | 1.694 (1.48–1.94) | 7.469 (5.73–9.74) | 3.728 (2.96–4.70) | 1.133 (0.93–1.39) | 3.893 (3.06–4.96) | 8.413 (6.47–10.95) | 8.576 (6.70–10.98) | [52,53,54,55,56] |

| Model | AUC a | AUPRC b | Sensitivity c | Specificity d | Precision e | ACC f | MCC g | F1 h | BA i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Risk Model | 0.695 | 0.523 | 0.712 | 0.488 | 0.410 | 0.563 | 0.192 | 0.521 | 0.600 |

| Metabolite-Enriched Model | 0.874 | 0.768 | 0.825 | 0.749 | 0.622 | 0.774 | 0.545 | 0.709 | 0.787 |

| Integrated Multi-omics Model | 0.935 | 0.879 | 0.888 | 0.525 | 0.483 | 0.646 | 0.400 | 0.626 | 0.707 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cha, J.; Choi, S. Integrated Genomic–Metabolomic Analysis for Tri-Categorical Classification of Type 2 Diabetes Status in the Korean Ansan–Ansung Cohort. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311688

Cha J, Choi S. Integrated Genomic–Metabolomic Analysis for Tri-Categorical Classification of Type 2 Diabetes Status in the Korean Ansan–Ansung Cohort. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311688