Heterogeneity of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Gene Variants: A Genetic Database Analysis in Russia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Methods

4.2. Molecular Genetic Methods

4.3. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. 2024. Available online: https://omim.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Raidt, J.; Riepenhausen, S.; Pennekamp, P.; Olbrich, H.; Amirav, I.; Athanazio, R.A.; Aviram, M.; Balinotti, J.E.; Bar-On, O.; Bode, S.F.N.; et al. Analyses of 1236 genotyped primary ciliary dyskinesia individuals identify regional clusters of distinct DNA variants and significant genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2301769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouis, P.; Yiallouros, P.K.; Middleton, N.; Evans, J.S.; Kyriacou, K.; Papatheodorou, S.I. Prevalence of primary ciliary dyskinesia in consecutive referrals of suspect cases and the transmission electron microscopy detection rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, J.S.; Burgess, A.; Mitchison, H.M.; Moya, E.; Williamson, M.; Hogg, C. Diagnosis and management of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondratyeva, E.I.; Avdeev, S.N.; Kyian, T.A.; Mizernitskiy, Y.L. Classification of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Pulmonologiya 2023, 33, 731–738. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemark, A.; Goutaki, M.; Kinghorn, B.; Ardura-Garcia, C.; Baz-Redón, N.; Chilvers, M.; Davis, S.D.; De Brandt, J.; Dell, S.; Dhar, R.; et al. European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society guidelines for the diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 2500745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, A.J.; Davis, S.D.; Polineni, D.; Manion, M.; Rosenfeld, M.; Dell, S.D.; Chilvers, M.A.; Ferkol, T.W.; Zariwala, M.A.; Sagel, S.D.; et al. Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, e24–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, J.S.; Barbato, A.; Collins, S.A.; Goutaki, M.; Behan, L.; Caudri, D.; Dell, S.; Eber, E.; Escudier, E.; Hirst, R.A.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hannah, W.B.; Seifert, B.A.; Truty, R.; Zariwala, M.A.; Ameel, K.; Zhao, Y.; Nykamp, K.; Gaston, B. The global prevalence and ethnic heterogeneity of primary ciliary dyskinesia gene variants: A genetic database analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kopanos, C.; Tsiolkas, V.; Kouris, A.; Chapple, C.E.; Albarca Aguilera, M.; Meyer, R.; Massouras, A. VarSome: The human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.; Gao, Y.H.; Xie, J.Q.; He, X.W.; Wang, C.C.; Xu, J.F.; Zhang, G.J. Clinical and genetic spectrum of primary ciliary dyskinesia in Chinese patients: A systematic review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olbrich, H.; Schmidts, M.; Werner, C.; Onoufriadis, A.; Loges, N.T.; Raidt, J.; Banki, N.F.; Shoemark, A.; Burgoyne, T.; Al Turki, S.; et al. Recessive HYDIN mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia without randomization of left-right body asymmetry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, M.R.; Zariwala, M.; Leigh, M. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Clin. Chest Med. 2016, 37, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behan, L.; Dimitrov, B.D.; Kuehni, C.E.; Hogg, C.; Carroll, M.; Evans, H.J.; Goutaki, M.; Harris, A.; Packham, S.; Walker, W.T.; et al. PICADAR: A diagnostic predictive tool for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Dunnen, J.T.; Dalgleish, R.; Maglott, D.R.; Hart, R.K.; Greenblatt, M.S.; McGowan-Jordan, J.; Roux, A.F.; Smith, T.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Taschner, P.E. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illumina. BaseSpace Sequence Hub; Illumina, Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://basespace.illumina.com (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ryzhkova, O.P.; Kardymon, O.L.; Prohorchuk, E.B.; Konovalov, F.A.; Maslennikov, A.B.; Stepanov, V.A.; Afanasyev, A.A.; Zaklyazminskaya, E.V.; Kostareva, A.A.; Pavlov, A.E.; et al. Guidelines for the interpretation of massive parallel sequencing variants. Med. Genet. 2017, 16, 4–17. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demchenko, A.G.; Kyian, T.A.; Kondratyeva, E.I.; Bragina, E.E.; Ryzhkova, O.P.; Veiko, R.V.; Nazarova, A.G.; Chernykh, V.B.; Smirnikhina, S.A.; Kutsev, S.I. CFAP300 Loss-of-Function Mutations with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: Evidence from Ex Vivo and ALI Cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

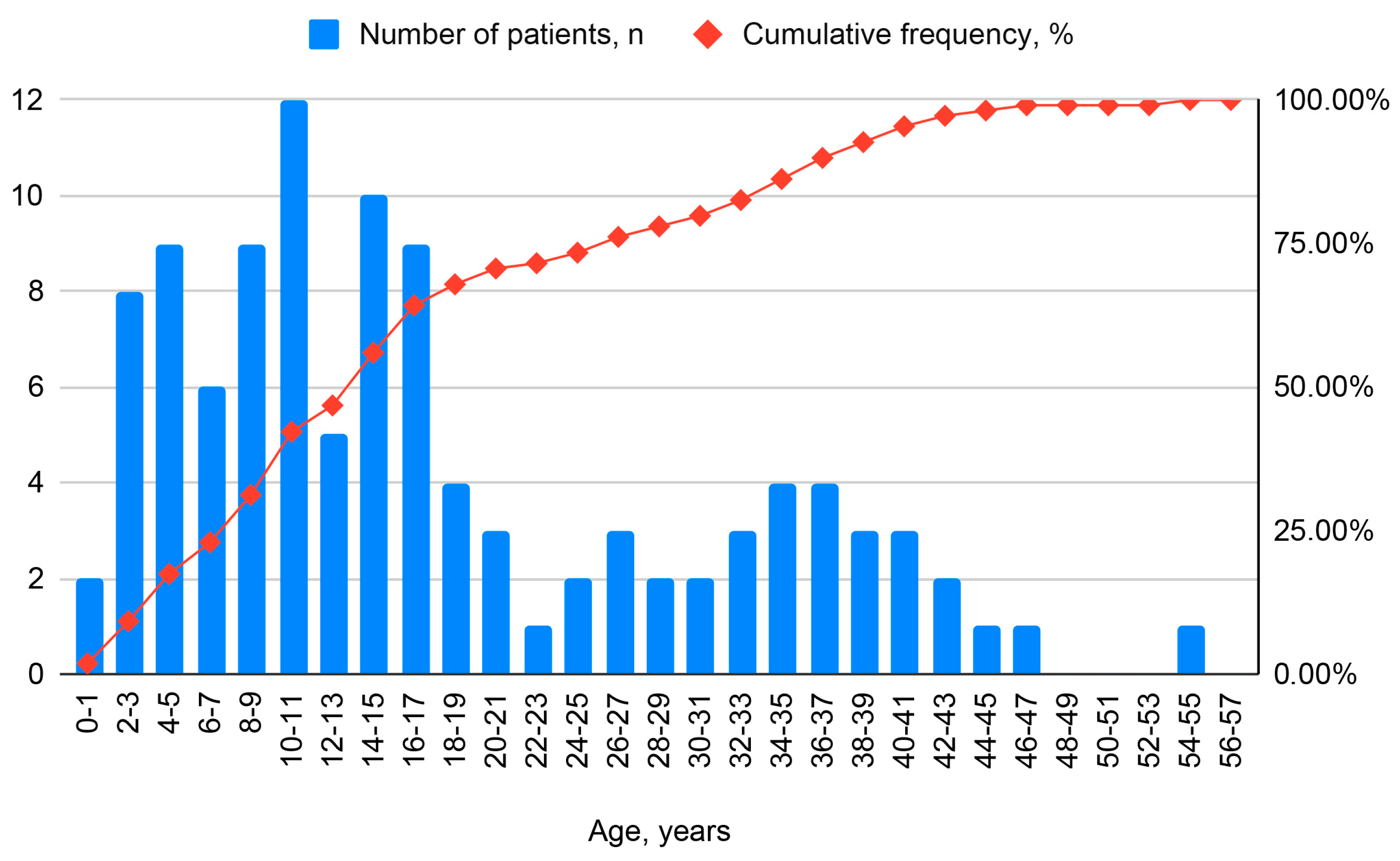

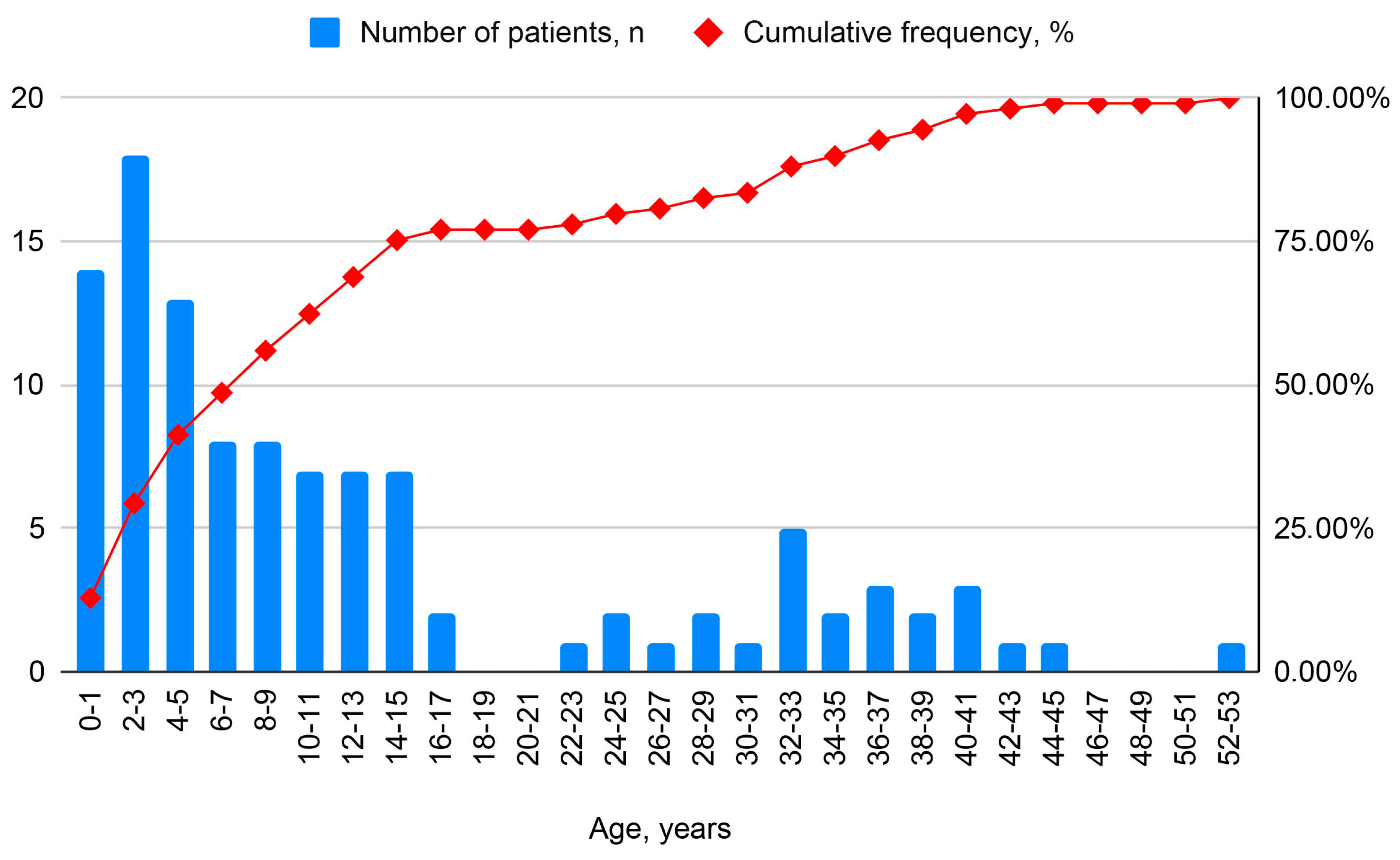

| Parameter | Child (<18 Years) | Adult (≥18 Years) | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number n (%) | 71 (65.1) | 38 (34.9) | 109 (100) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||

| M ± SD | 6.6 ± 4.8 | 27.9 ± 13.8 | 14.6 ± 13.8 |

| Me (IQR) | 7 (2.3–10.0) | 32 (17–38.5) | 10 (8–25.8) |

| № | Gene | Number of Identified Unique Genetic Variants | Inheritance Pattern | Number of Patients with Pathogenic Variants, n | Number of Patients with Pathogenic Variants, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DNAH5 | AR | 43 | 39.4 | |

| 2 | DNAH11 | AR | 10 | 9.2 | |

| 3 | CCDC39 | AR | 7 | 6.4 | |

| 4 | C11ORF70/CFAP300 | AR | 7 | 6.4 | |

| 5 | LRRC6/DNAAF11 | AR | 5 | 4.6 | |

| 6 | OFD1 | XLR | 3 | 2.7 | |

| 7 | HYDIN | AR | 3 | 2.7 | |

| 8 | DNAH9 | AR | 3 | 2.7 | |

| 9 | CCDC40 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 10 | CFAP221 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 11 | DNAH14 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 12 | CCDC114/ODAD1 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 13 | DNAL1 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 14 | DYX1C1/DNAAF4 | AR | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 15 | FOXJ1 | AD | 2 | 1.8 | |

| 16 | LRRC50/DNAAF1 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 17 | DNAH7 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 18 | DNAAF3 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 19 | CCDC164/DRC1 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 20 | RSPH4A | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 21 | CEP164 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 22 | CFAP52 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 23 | DNAH6 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 24 | DNAH17 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 25 | FSIP2 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 26 | CCDC103 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 27 | GAS8/DRC4 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 28 | SPAG1 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 29 | RSPH9 | AR | 1 | 0.9 | |

| All genes | 123 | 109 | 100% |

| № | Gene | Inheritance Pattern | KS, n | KS, % | Absence of KS, n | Absence of KS, % | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DNAH5 | AR | 32 | 55.0 | 11 | 21.5 | 0.0004 |

| 2 | DNAH11 | AR | 5 | 8.6 | 5 | 9.8 | 0.748 |

| 3 | CCDC39 | AR | 3 | 5.2 | 4 | 7.8 | 1 |

| 4 | DNAH9 | AR | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.8 | - |

| 5 | C11ORF70/CFAP300 | AR | 5 | 8.6 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.4 |

| 6 | LRRC6/DNAAF11 | AR | 1 | 1.7 | 4 | 7.8 | 0.2 |

| 7 | DNAH14 | AR | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.0 | - |

| 8 | HYDIN | AR | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.8 | - |

| 9 | CCDC114/ODAD1 | AR | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 |

| 10 | OFD1 | XLR | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.8 | - |

| 11 | DYX1C1/DNAAF4 | AR | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.0 | - |

| 12 | CFAP221 | AR | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.0 | - |

| 13 | DNAL1 | AR | 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.00 | - |

| 14 | RSPH4A | AR | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.00 | - |

| 15 | FOXJ1 | AD | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 |

| № | Gene | Unreported Genetic Variant Previously | gnomAD v3.1.2 Number of Homozygotes | gnomAD v3.1.2 Allele Frequency | ACMG | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DNAH5 | c.12850dup, p.(Tyr4284LeufsTer14) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2, PM3 | P |

| c.3074dupC, p.(Ala1026fs) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2, PM3 | P | ||

| c.8390T>G, p.(Leu2797Arg) | n/d | n/d | PM2, PM3 | VoUS | ||

| c.6813C>A, p.(Cys2271Ter) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2 | LP | ||

| c.12216del, p.(Tyr4072Ter) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2 | LP | ||

| c.13604_13609del, p.(Val4535_Tyr4536del) | n/d | n/d | PM2, PM3 | VoUS | ||

| 2 | DNAH11 | c.13387_13444dup, p.(Arg4482LysfsTer20) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| c.5461-3T>G, p.(?) | n/d | n/d | PM2, PM3 | VoUS | ||

| c.8572G>A, p.(Gly2858Ser) | 0 | 0.0002037 | PM2 | VoUS | ||

| c.8363A>G, p.(His2788Arg) | n/d | n/d | PM2 | VoUS | ||

| 3 | OFD1 | c.2674C>T, p.(Gln892Ter) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| 4 | DNAH14 | c.9011G>C, p.(Arg3004Pro) | n/d | n/d | PM2 | VoUS |

| c.12068C>T, p.(Pro4023Leu) | n/d | n/d | PM2 | VoUS | ||

| 5 | DNAH2 | c.5372C>T, p.Thr1791Met | 0 | 0.00003942 | PM2 | VoUS |

| 6 | DNAAF11/LRRC6 | c.574C>G, p.(Gln192Glu) | 0 | 0.001197 | PM2 | VoUS |

| c.1011A>G, p.(Gln337Gln) | 0 | 0.00003942 | PM2 | VoUS | ||

| 7 | DNAAF4 | c.430dup, p.(Ile144AsnfsTer8) | 0 | 0.00001994 | PVS1, PM2, PM3 | P |

| 8 | DNAAF1 | c.1384C>T, p.(Gln462Ter) | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| c.655T>C, p.(Cys219Arg) | 0 | 0.00006580 | PM2, PM3 | P | ||

| 9 | CFAP221 | c.1641dup, p.(Asn548GlnfsTer6) | 0 | 0.0001646 | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| 10 | CCDC39 | c.2492_2496del, p.Met831ThrfsTer7 | n/d | n/d | PVS1, PM2, PM3 | P |

| 11 | DNAH6 | c.11669G>A, p.(Arg3890His) | 0 | 0.0005784 | PM2 | VoUS |

| c.11612-42A>G, p.? | 0 | 0.0008870 | PM2, PP3 | VoUS | ||

| 12 | CFAP300 | c.289G>T, p.(Glu97Ter) | 0 | 0.000006576 | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| 13 | CEP164 | c. 1865G>A, p.Arg622Gln | 0 | 0.0001446 | PM2, PP3 | VoUS |

| c.3055C>T, p.Gln1019Ter | 0 | 0.00003944 | PVS1, PM2 | LP |

| Gene | Russia (N = 109) | Patient, % | International Study (N = 1236) | Patient, % (International Study) | Place (International Study) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAH5 (603335) | 43 | 39.4 | 275 | 22.0 | 1 | 0.009 |

| DNAH11 (603339) | 10 | 9.2 | 142 | 11.0 | 2 | 0.5 |

| CCDC39 (613798) | 7 | 6.4 | 66 | 5.0 | 5 | 0.7 |

| C11ORF70/CFAP300 (618058) | 7 | 6.4 | 22 | 1.8 | 13 | 0.006 |

| LRRC6/DNAAF11 (614930) | 5 | 4.6 | 44 | 3.6 | 8 | 0.3 |

| OFD1 (300170) | 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 0.24 | 18 | 0.009 |

| HYDIN (610812) | 3 | 2.7 | 42 | 3.4 | 9 | 0.8 |

| DNAH9 (603330) | 3 | 5.5 | 5 | 0.4 | 16 | 0.00008 |

| CCDC40 (613799) | 2 | 1.8 | 115 | 9.0 | 3 | 0.004 |

| CFAP221 | 2 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.08 | 22 | 0.02 |

| DNAH14 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | – | - | – |

| CCDC114/ODAD1 (615038) | 2 | 1.8 | 37 | 3.0 | 10 | 0.5 |

| DNAL1 (610062) | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | – | – | – |

| DYX1C1/DNAAF4 (608706) | 2 | 1.8 | 35 | 2.8 | 11 | 0.4 |

| FOXJ1 (602291) | 2 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.1 | 21 | 0.02 |

| Russian Cohort | Chinese Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | % | Gene | % |

| DNAH5 | 39.4 | DNAH5 | 21.1 |

| DNAH11 | 9.2 | DNAH11 | 18.3 |

| CCDC39 | 6.4 | CCDC39 | 9.2 |

| C11ORF70/CFAP300 | 6.4 | CCDC40 | 6.3 |

| LRRC6/DNAAF11 | 4.6 | HYDIN | 4.9 |

| OFD1 | 2.7 | CCNO | 4.9 |

| HYDIN | 2.7 | DNAAF3 | 4.9 |

| DNAH9 | 5.5 | DNAH1 | 3.5 |

| CCDC40 | 2 | DNAAF11 (LRRC6) | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kondratyeva, E.I.; Avdeev, S.N.; Kyian, T.A.; Ryzhkova, O.P.; Melyanovskaya, Y.L.; Zabnenkova, V.V.; Bulakh, M.V.; Merzhoeva, Z.M.; Bukhonin, A.V.; Trushenko, N.V.; et al. Heterogeneity of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Gene Variants: A Genetic Database Analysis in Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311674

Kondratyeva EI, Avdeev SN, Kyian TA, Ryzhkova OP, Melyanovskaya YL, Zabnenkova VV, Bulakh MV, Merzhoeva ZM, Bukhonin AV, Trushenko NV, et al. Heterogeneity of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Gene Variants: A Genetic Database Analysis in Russia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311674

Chicago/Turabian StyleKondratyeva, Elena I., Sergey N. Avdeev, Tatiana A. Kyian, Oksana P. Ryzhkova, Yuliya L. Melyanovskaya, Victoria V. Zabnenkova, Maria V. Bulakh, Zamira M. Merzhoeva, Artem V. Bukhonin, Natalia V. Trushenko, and et al. 2025. "Heterogeneity of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Gene Variants: A Genetic Database Analysis in Russia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311674

APA StyleKondratyeva, E. I., Avdeev, S. N., Kyian, T. A., Ryzhkova, O. P., Melyanovskaya, Y. L., Zabnenkova, V. V., Bulakh, M. V., Merzhoeva, Z. M., Bukhonin, A. V., Trushenko, N. V., Lavginova, B. B., Zhukova, D. O., & Kutsev, S. I. (2025). Heterogeneity of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Gene Variants: A Genetic Database Analysis in Russia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311674