The Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 In Vivo and Its Potential to Overcome Bacterial Resistance to Penicillin Enhanced by Hypericin-Induced Photodynamic Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination

2.2. Drug Encapsulation Efficiency

2.3. Drug Release Kinetics Study of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination

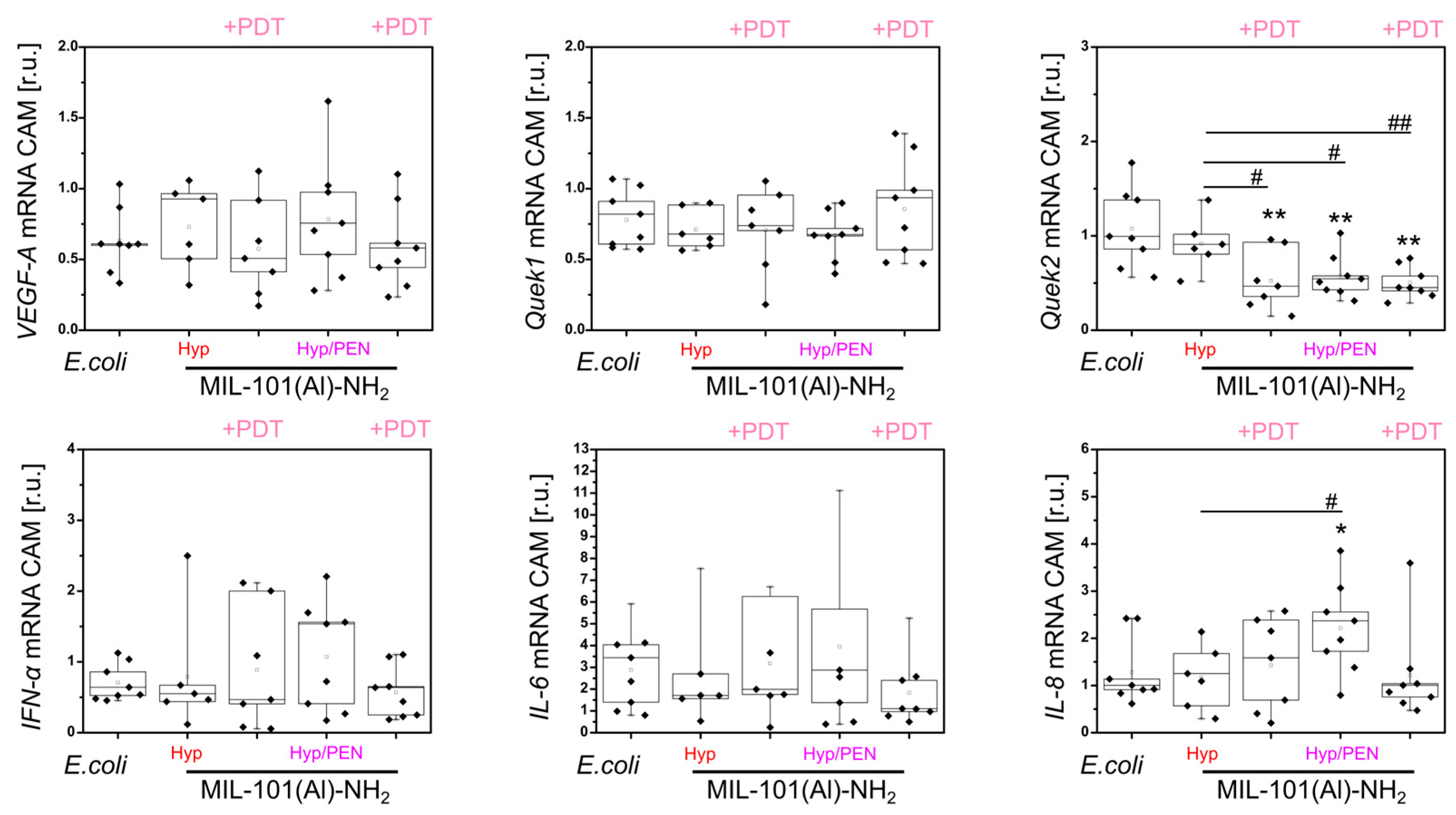

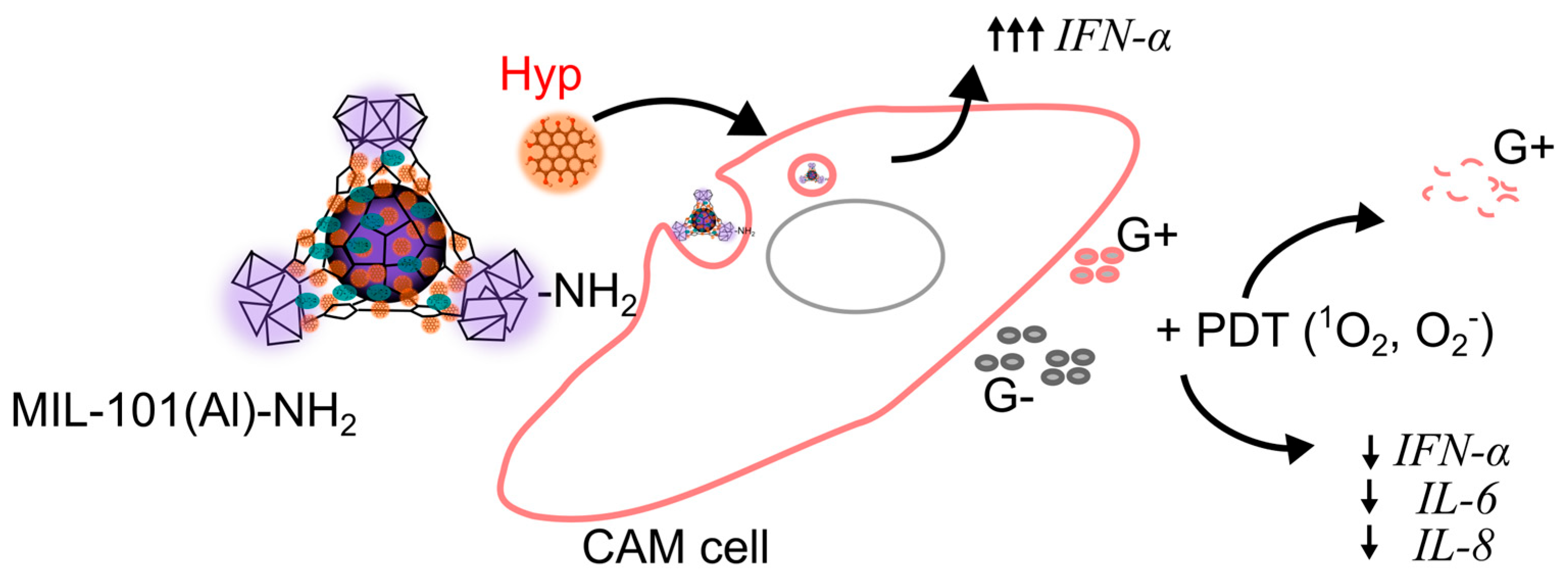

2.4. Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination In Vivo

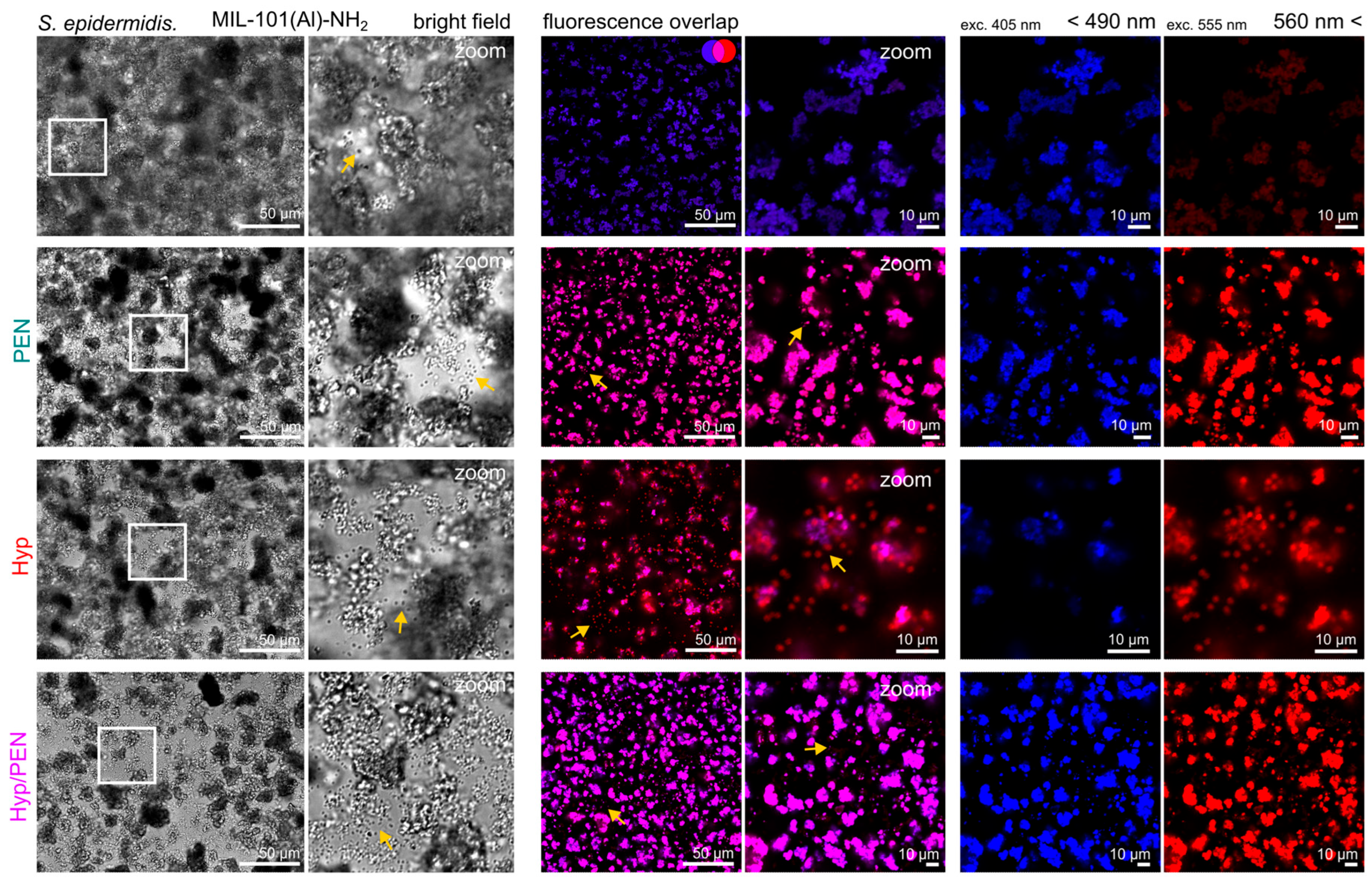

2.4.1. Interaction of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination with CAM of Quail Embryo

2.4.2. Interaction of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination with CAM of Quail Embryo Infected with E. coli

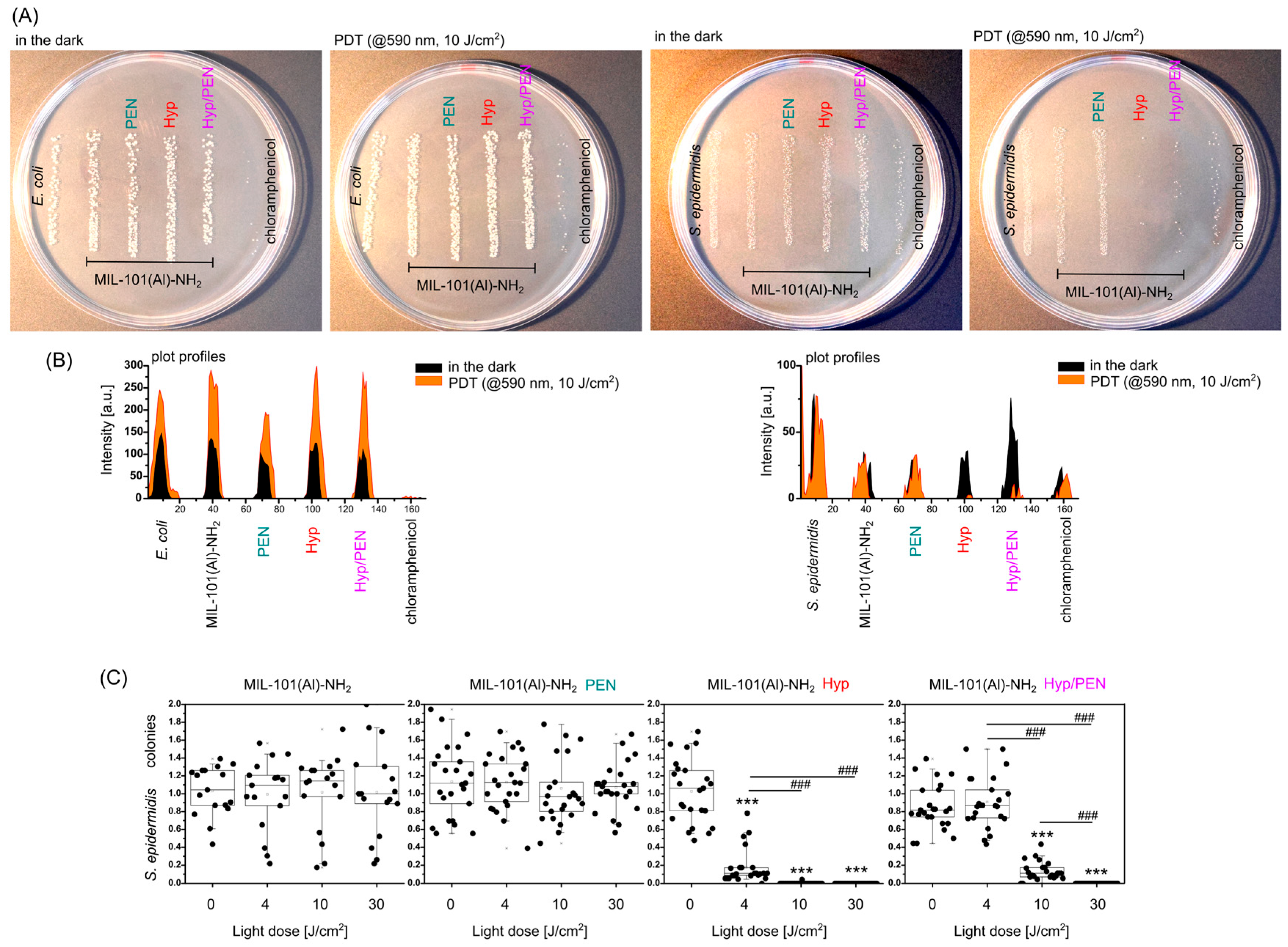

2.5. Antibacterial Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination Induced by PDT

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis and Characterization of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination

4.1.1. Synthesis of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination

4.1.2. Characterization of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination

4.1.3. PEN and Hyp Release Kinetics from MIL-101(Al)-NH2

4.2. Interaction of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination with Quail Chorioallantoic Membrane Model (CAM)

4.2.1. Preparation of Quail CAM In Vivo Model

4.2.2. Biocompatibility of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination with Quail CAM In Vivo Model and E. coli Infected CAM Model

4.2.3. Fluorescence Pharmacokinetics of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and Hyp in CAM Models

4.2.4. Photodynamic Treatment of CAM Models Induced by Combination of MIL-101(Al)-NH2, PEN and Hyp

4.2.5. Histological Evaluation of Treated CAM Models

4.2.6. Evaluation of Molecular Biology Parameters in CAM Models

4.3. Interaction of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 and MIL-101(Al)-NH2 Loaded with PEN, Hyp and Their Combination with Bacterial Strains

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandla, S.; Davenport Huyer, L.; Radisic, M. Review: Multimodal Bioactive Material Approaches for Wound Healing. APL Bioeng. 2018, 2, 021503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsley, A. A Proactive Approach to Wound Infection. Nurs. Stand. 2001, 15, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oropallo, A.R.; Andersen, C.; Abdo, R.; Hurlow, J.; Kelso, M.; Melin, M.; Serena, T.E. Guidelines for Point-of-Care Fluorescence Imaging for Detection of Wound Bacterial Burden Based on Delphi Consensus. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.O.; Quon, A.S.; Nguyen, A.; Papazyan, E.K.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y. Constructing Physiological Defense Systems against Infectious Disease with Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 3052–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.L.; Mardel, J.I.; Hill, M.R. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) As Hydrogen Storage Materials at Near-Ambient Temperature. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Chen, W. Carbon Dioxide Capture and Conversion Using Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) Materials: A Comprehensive Review. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Han, Z.; Fan, J. Review of Synthesis and Separation Application of Metal-Organic Framework-Based Mixed-Matrix Membranes. Polymers 2023, 15, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, Z.A.; Raza, M.A.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A.; Farwa, U.; Ashraf, S.; Dildar, A.; Fatima, E.; Ashraf, S.; Ali, F. Metal-Organic Frameworks for next-Generation Energy Storage Devices; A Systematic Review. Mater. Adv. 2023, 5, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capková, D.; Almáši, M. Chapter 9—Coordination Materials for Metal–Sulfur Batteries. In Electrochemistry and Photo-Electrochemistry of Nanomaterials; Yasin, G., Ibraheem, S., Kumar, A., Nguyen, T.A., Maiyalagan, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 287–331. ISBN 978-0-443-18600-4. [Google Scholar]

- Király, N.; Capková, D.; Gyepes, R.; Vargová, N.; Kazda, T.; Bednarčík, J.; Yudina, D.; Zelenka, T.; Čudek, P.; Zeleňák, V.; et al. Sr(II) and Ba(II) Alkaline Earth Metal–Organic Frameworks (AE-MOFs) for Selective Gas Adsorption, Energy Storage, and Environmental Application. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zeng, B.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Hu, T.; Zhang, L. A Systematic Review of Metal Organic Frameworks Materials for Heavy Metal Removal: Synthesis, Applications and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Álvarez, F.G.; Mendoza-Castillo, D.I.; Almáši, M.; García-Hernández, E.; Palomino-Asencio, L.; Cuautli, C.; Duran-Valle, C.J.; Adame-Pereira, M.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A. Lanthanide-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks MOF-76 for the Depollution of Xenobiotics from Water: Arsenic and Fluoride Adsorption Properties and Multi-Anionic Mechanism Analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1338, 142113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglione, C.; Hidalgo, T.; Horcajada, P. Nanoscaled Metal-Organic Frameworks: Charting a Transformative Path for Cancer Therapeutics and Beyond. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 2041–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almáši, M. A Review on State of Art and Perspectives of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in the Fight against Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. J. Coord. Chem. 2021, 74, 2111–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhaut, T.; Filinchuk, Y.; Hermans, S. Aluminium-Based MIL-100(Al) and MIL-101(Al) Metal-Organic Frameworks, Derivative Materials and Composites: Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 21483–21509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeste, A.; Paolone, A.; Itié, J.P.; Borondics, F.; Joseph, B.; Grad, O.; Blanita, G.; Zlotea, C.; Capitani, F. Mesoporous Metal-Organic Framework MIL-101 at High Pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15012–15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.Q.; Yang, J.C.; Yin, X.B. Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensing and Real-Time Detection of Water in Organic Solvents with One-Pot Synthesis of Ru@MIL-101(Al)-NH2. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 13434–13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Zheng, T.; Hou, Y.; Hong, X.; Du, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. An Aluminum Adjuvant-Integrated Nano-MOF as Antigen Delivery System to Induce Strong Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses. J. Control. Release 2019, 300, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, R.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Ning, W.; Duan, X.; Jiao, J.; Fu, X.; Zhang, G. Hollow Metal-Organic Framework-Based, Stimulator of Interferon Genes Pathway-Activating Nanovaccines for Tumor Immunotherapy. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 6, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, T.; Simón-Vázquez, R.; González-Fernández, A.; Horcajada, P. Cracking the Immune Fingerprint of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, A.M.; Martin, C.R.; Galitskiy, V.A.; Berseneva, A.A.; Leith, G.A.; Shustova, N.B. Photophysics Modulation in Photoswitchable Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8790–8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, T.; Au, V.K.M. Photoresponsive Metal-Organic Frameworks: Tailorable Platforms of Photoswitches for Advanced Functions. ChemNanoMat 2022, 8, e202100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xing, F.; Yu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, R.; Liu, M.; Ritz, U. Metal-Organic Framework-Based Advanced Therapeutic Tools for Antimicrobial Applications. Acta Biomater. 2024, 175, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tang, G.; Niu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Preparation of a Porphyrin Metal-Organic Framework with Desirable Photodynamic Antimicrobial Activity for Sustainable Plant Disease Management. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohamadpour, A.; Bahramian, B.; Khoobi, M.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Barikani, H.R.; Bahador, A. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Assessment of Three Indocyanine Green-Loaded Metal-Organic Frameworks against Enterococcus Faecalis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Shah, H.; Nawaz, A.; Xie, W.; Akram, M.Z.; Batool, A.; Tian, L.; Jan, S.U.; Boddula, R.; Guo, B.; et al. Antibacterial Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1804838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Lei, J.; Feng, X.; et al. The Enhanced Photocatalytic Sterilization of MOF-Based Nanohybrid for Rapid and Portable Therapy of Bacteria-Infected Open Wounds. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 13, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Forghani, F.; Kong, X.; Liu, D.; Ye, X.; Chen, S.; Ding, T. Antibacterial Applications of Metal–Organic Frameworks and Their Composites. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1397–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Márquez, D.M.; Blanco Flores, A.; Toledo Jaldin, H.P.; Burke Irazoque, M.; González Torres, M.; Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Toledo, C.C.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, S.; Díaz Rodríguez, J.P.; Dorazco-González, A. MIL-53 MOF on Sustainable Biomaterial for Antimicrobial Evaluation Against E. coli and S. aureus Bacteria by Efficient Release of Penicillin G. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Li, S. Crystalline Porous Frameworks (MOF@COF) for Adsorption-Desorption Analysis of β-Lactam Drugs. Polymer 2025, 320, 127973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Moradian, M.; Tayebi, H.A.; Mirabi, A. Removal of Penicillin G from Aqueous Medium by PPI@SBA-15/ZIF-8 Super Adsorbent: Adsorption Isotherm, Thermodynamic, and Kinetic Studies. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xia, X.; Hou, W.; Lv, H.; Liu, J.; Li, X. How Effective Are Metal Nanotherapeutic Platforms Against Bacterial Infections? A Comprehensive Review of Literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 1109–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Kathuria, A.; Gaikwad, K.K. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Active Food Packaging. A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1479–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, T.; Castelino, E.; Lakshmi, T.; Mulky, L.; Selvanathan, S.P.; Tahir, M. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Antibacterial Disinfection: A Review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2024, 11, e202400006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Zhu, N.; Wu, Y.; Li, G. Antibacterial Mechanisms and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Derived Nanomaterials. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, T.; Pan, X. Metal-Organic-Framework-Based Materials for Antimicrobial Applications. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3808–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntošová, V.; Benziane, A.; Zauška, L.; Ambro, L.; Olejárová, S.; Joniová, J.; Hlávková, N.; Wagnières, G.; Zelenková, G.; Diko, P.; et al. The Potential of Metal–Organic Framework MIL-101(Al)–NH2 in the Forefront of Antiviral Protection of Cells via Interaction with SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Protein and Their Antibacterial Action Mediated with Hypericin and Photodynamic Treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 691, 137454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Du, M. Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Antibacterial Activity by in-Situ Synthesized NH2-MIL-101(Al)/AgI Heterojunction and Mechanism Insight. Environ. Res. 2025, 267, 120733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zauška, Ľ.; Pillárová, P.; Volavka, D.; Kinnertová, E.; Bednarčík, J.; Brus, J.; Hornebecq, V.; Almáši, M. Kinetic Adsorption Mechanism of Cobalt(II) Ions and Congo Red on Pristine and Schiff Base-Surface-Modified MIL-101(Fe)-NH2. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 386, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K.I.; Panayotov, D.A.; Mihaylov, M.Y.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Chakarova, K.K.; Andonova, S.M.; Drenchev, N.L. Power of Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies to Characterize Metal-Organic Frameworks and Investigate Their Interaction with Guest Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1286–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, O.I.; Millange, F.; Serre, C.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Férey, G. First Direct Imaging of Giant Pores of the Metal-Organic Framework MIL-101. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 6525–6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, S.; Barrio, M.; Negrier, P.; Romanini, M.; MacOvez, R.; Tamarit, J.L. Comparative Physical Study of Three Pharmaceutically Active Benzodiazepine Derivatives: Crystalline versus Amorphous State and Crystallization Tendency. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1819–1832, Erratum in Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3926–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleňák, V.; Halamová, D.; Almáši, M.; Žid, L.; Zeleňáková, A.; Kapusta, O. Ordered Cubic Nanoporous Silica Support MCM-48 for Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drug Indomethacin. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 443, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almáši, M.; Beňová, E.; Zeleňák, V.; Madaj, B.; Huntošová, V.; Brus, J.; Urbanová, M.; Bednarčík, J.; Hornebecq, V. Cytotoxicity Study and Influence of SBA-15 Surface Polarity and PH on Adsorption and Release Properties of Anticancer Agent Pemetrexed. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, J.; Hidalgo-Rosa, Y.; Burboa, P.C.; Wu, Y.; Escalona, N.; Leiva, A.; Zarate, X.; Schott, E. UiO-66(Zr) as Drug Delivery System for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. J. Control. Release 2024, 370, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migasová, A.; Zauška, Ľ.; Zelenka, T.; Volavka, D.; Férová, M.; Gulyásová, T.; Tomková, S.; Saláková, M.; Kuchárová, V.; Samuely, T.; et al. Histidine-Modified UiO-66(Zr) Nanoparticles as an Effective PH-Responsive Carrier for 5-Fluorouracil Drug Delivery System: A Possible Pathway to More Effective Brain Cancer Treatments. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevná, V.; Zauška, L.; Benziane, A.; Vámosi, G.; Girman, V.; Miklóšová, M.; Zeleňák, V.; Huntošová, V.; Almáši, M. Effective Transport of Aggregated Hypericin Encapsulated in SBA-15 Nanoporous Silica Particles for Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer Cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2023, 247, 112785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauska, L.; Benova, E.; Urbanová, M.; Brus, J.; Zelenak, V.; Hornebecq, V.; Almáši, M. Adsorption and Release Properties of Drug Delivery System Naproxen-SBA-15: Effect of Surface Polarity, Sodium/Acid Drug Form and PH. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Cha, D.; Zheng, X.; Yousef, A.A.; Song, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Direct Imaging of Tunable Crystal Surface Structures of MOF MIL-101 Using High-Resolution Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 12021–12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntošová, V.; Datta, S.; Lenkavská, L.; MáčAjová, M.; Bilčík, B.; Kundeková, B.; Čavarga, I.; Kronek, J.; Jutková, A.; Miškovský, P.; et al. Alkyl Chain Length in Poly(2-Oxazoline)-Based Amphiphilic Gradient Copolymers Regulates the Delivery of Hydrophobic Molecules: A Case of the Biodistribution and the Photodynamic Activity of the Photosensitizer Hypericin. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4199–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundeková, B.; Máčajová, M.; Meta, M.; Čavarga, I.; Huntošová, V.; Datta, S.; Miškovský, P.; Kronek, J.; Bilčík, B. The Japanese Quail Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Model to Study an Amphiphilic Gradient Copoly(2-Oxazoline)s- Based Drug Delivery System for Photodynamic Diagnosis and Therapy Research. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yow, C.M.N.; Tang, H.M.; Chu, E.S.M.; Huang, Z. Hypericin-Mediated Photodynamic Antimicrobial Effect on Clinically Isolated Pathogens. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012, 88, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.F.C.; Aroso, R.T.; Dabrowski, J.M.; Pucelik, B.; Barzowska, A.; da Silva, G.J.; Arnaut, L.G.; Pereira, M.M. Photodynamic Inactivation of E. coli with Cationic Imidazolyl-Porphyrin Photosensitizers and Their Synergic Combination with Antimicrobial Cinnamaldehyde. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2024, 23, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Marek, A.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wieczorek, K.; Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Osek, J. Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria—A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songca, S.P.; Adjei, Y. Applications of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy against Bacterial Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubab, M.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Recent Advances and Potential Applications for Metal-Organic Framework (MOFs) and MOFs-Derived Materials: Characterizations and Antimicrobial Activities. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 42, e00837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Dao, X.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.D.; Sun, W.Y. Sensing Properties of Nh2-Mil-101 Series for Specific Amino Acids via Turn-on Fluorescence. Molecules 2021, 26, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Zhai, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Z. Dual-Emission Dye@MIL-101(Al) Composite as Fluorescence Sensor for the Selective and Sensitive Detection towards Arginine. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 323, 124025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pei, X. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Nanomaterials for Regulation of the Osteogenic Microenvironment. Small 2024, 20, 2310622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, K.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.; He, Z.; Meng, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Pei, X.; et al. Biomimetic Management of Bone Healing Stages: MOFs Induce Tunable Degradability and Enhanced Angiogenesis-Osteogenesis Coupling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. Lymphatics in the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane. Microvasc. Res. 2025, 160, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Quan, C.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Zhong, X. Palmitic Acid-Capped MIL-101-Al as a Nano-Adjuvant to Amplify Immune Responses against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 10306–10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, R.; Zaat, S.A.; Breukink, E.; Heger, M. Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy: Overview of a Promising Approach to Fight Antibiotic-Resistant Bacterial Infections. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2015, 1, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.M.; Yakovlev, V.V.; Blanco, K.C.; Bagnato, V.S. Photodynamic Inactivation and Its Effects on the Heterogeneity of Bacterial Resistance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28268, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Yin, S.; Chen, Q.D.; Sun, H.B.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L.; Sun, K. Mimicking the Competitive Interactions to Reduce Resistance Induction in Antibacterial Actions. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Webster, T.J. Bacteria Antibiotic Resistance: New Challenges and Opportunities for Implant-Associated Orthopedic Infections. J. Orthop. Res. 2018, 36, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelenka, T.; Simanova, K.; Saini, R.; Zelenkova, G.; Nehra, S.P.; Sharma, A.; Almasi, M. Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Adsorption Study on Surface-Modified HKUST-1 with Diamine/Triamine. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almáši, M.; Sharma, A.; Zelenka, T. Anionic Zinc(II) Metal-Organic Framework Post-Synthetically Modified by Alkali-Ion Exchange: Synthesis, Characterization and Hydrogen Adsorption Properties. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2021, 526, 120505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform Extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macajova, M.; Cavarga, I.; Sykorova, M.; Valachovic, M.; Novotna, V.; Bilcik, B. Modulation of Angiogenesis by Topical Application of Leptin and High and Low Molecular Heparin Using the Japanese Quail Chorioallantoic Membrane Model. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uno, Y.; Usui, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Ito, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Quantification of Interferon, Interleukin, and Toll-like Receptor 7 MRNA in Quail Splenocytes Using Real-Time PCR. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2496–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MIL-101(Al)-NH2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of treatment on: | E. coli | - | + PEN | + Hyp | + Hyp/PEN |

| * E. coli * PDT | * E. coli * PDT | ||||

| angiogenesis | |||||

| VEGF-A | ↓↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ — — | — — — |

| Quek1 | ↓ | — | — | — — — | — — — |

| Lymphogenesis | |||||

| Quek2 | — | — | — | — — ↓↓ | — ↓↓ ↓↓ |

| Immunostimulation | |||||

| IFN-α | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ — — | ↑↑↑ — — |

| IL-6 | ↑ | ↓ | — | — — — | — — — |

| IL-8 | — | — | — | — — — | — ↑ — |

| Gen | Primers (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | GGTGATAAATCCCGATGAAGT TCTCCATAAACGAAGTAAAGTCTC | 61.5 59.4 |

| IL-8 | CTGAGGTGCCAGTGCATTAG AGCACACCTCTCTTCCATCC | 63.5 63.3 |

| IFN-α | CCTTGCTCCTTCAACGACA CGCTGAGGATACTGAAGAGGT | 64.1 62.3 |

| VEGF-A | CGGAAGCCCAATGAAGTTATC GCACATCTCATCAGAGGCACA | 59.4 64.0 |

| Quek1 | CATCAATGCGAATCATACAGTTAAG CATTCACAAGCAGGGTGAATG | 60.9 59.4 |

| Quek2 | GAGATGAGCGGCTGATCTACTTC GAAAGGTTCAGGCGATACCAC | 64.7 61.3 |

| β-aktin | TGAACCCCAAAGCCAACAG CCACAGGACTCCATACCCAAG | 66.0 65.5 |

| GAPDH | GAACGCCATCACTATCTTCCAG GGGCTGAGATGATAACACGC | 62.1 60.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Máčajová, M.; Ambro, Ľ.; Meta, M.; Zauška, Ľ.; Gulyásová, T.; Bilčík, B.; Čavarga, I.; Zelenková, G.; Sedlák, E.; Almáši, M.; et al. The Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 In Vivo and Its Potential to Overcome Bacterial Resistance to Penicillin Enhanced by Hypericin-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311681

Máčajová M, Ambro Ľ, Meta M, Zauška Ľ, Gulyásová T, Bilčík B, Čavarga I, Zelenková G, Sedlák E, Almáši M, et al. The Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 In Vivo and Its Potential to Overcome Bacterial Resistance to Penicillin Enhanced by Hypericin-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311681

Chicago/Turabian StyleMáčajová, Mariana, Ľuboš Ambro, Majlinda Meta, Ľuboš Zauška, Terézia Gulyásová, Boris Bilčík, Ivan Čavarga, Gabriela Zelenková, Erik Sedlák, Miroslav Almáši, and et al. 2025. "The Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 In Vivo and Its Potential to Overcome Bacterial Resistance to Penicillin Enhanced by Hypericin-Induced Photodynamic Therapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311681

APA StyleMáčajová, M., Ambro, Ľ., Meta, M., Zauška, Ľ., Gulyásová, T., Bilčík, B., Čavarga, I., Zelenková, G., Sedlák, E., Almáši, M., & Huntošová, V. (2025). The Immunostimulatory Effect of MIL-101(Al)-NH2 In Vivo and Its Potential to Overcome Bacterial Resistance to Penicillin Enhanced by Hypericin-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311681