Development of Plasma Protein Classification Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multiple Machine Learning Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

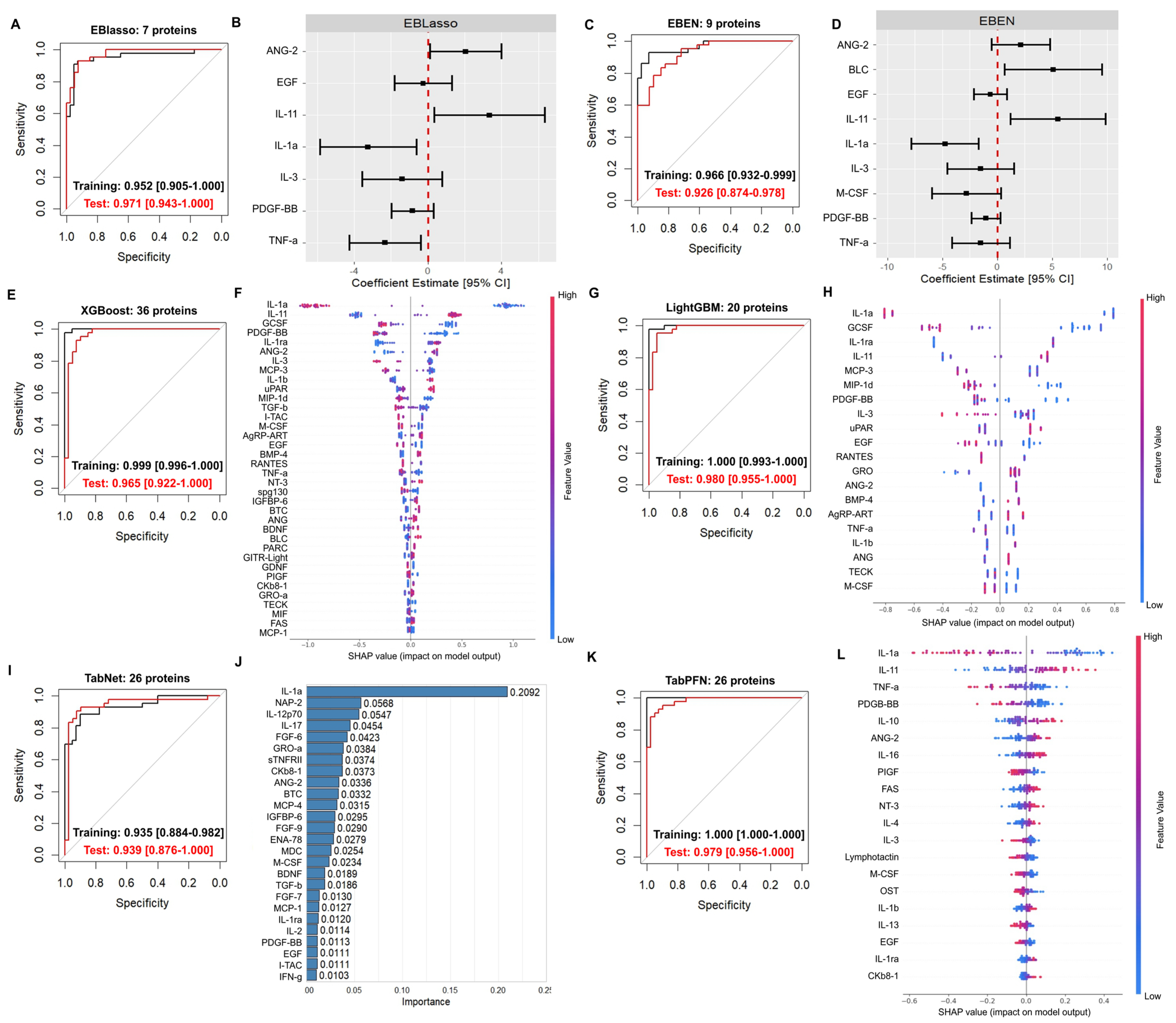

2.1. Applying Various ML Algorithms to Previously Generated Plasma Proteomic Data Yielded Highly Accurate Classification Models

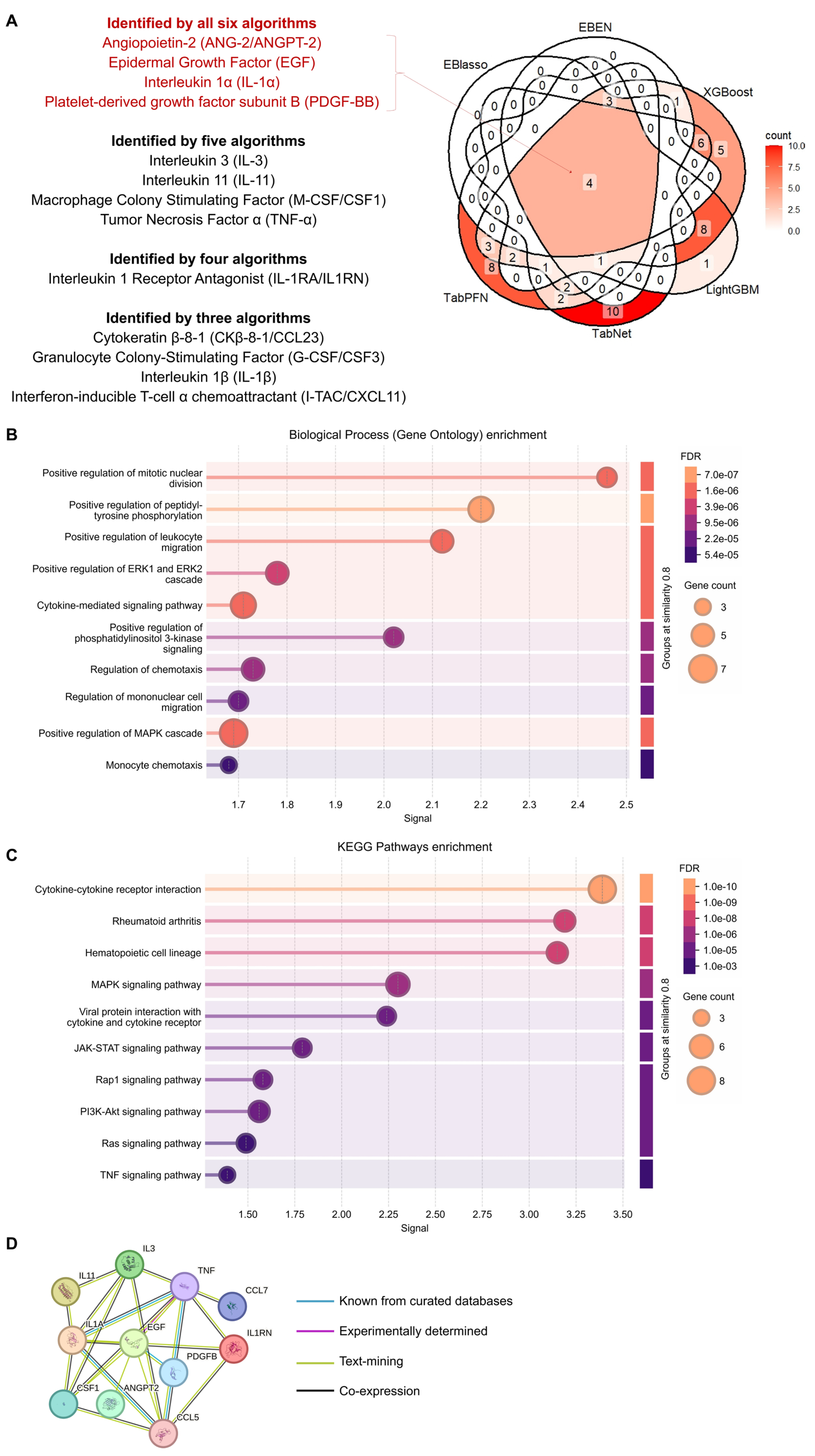

2.2. Proteins Found to Be Important for Prediction Across Different Models Are Associated with Various Functions and Pathways

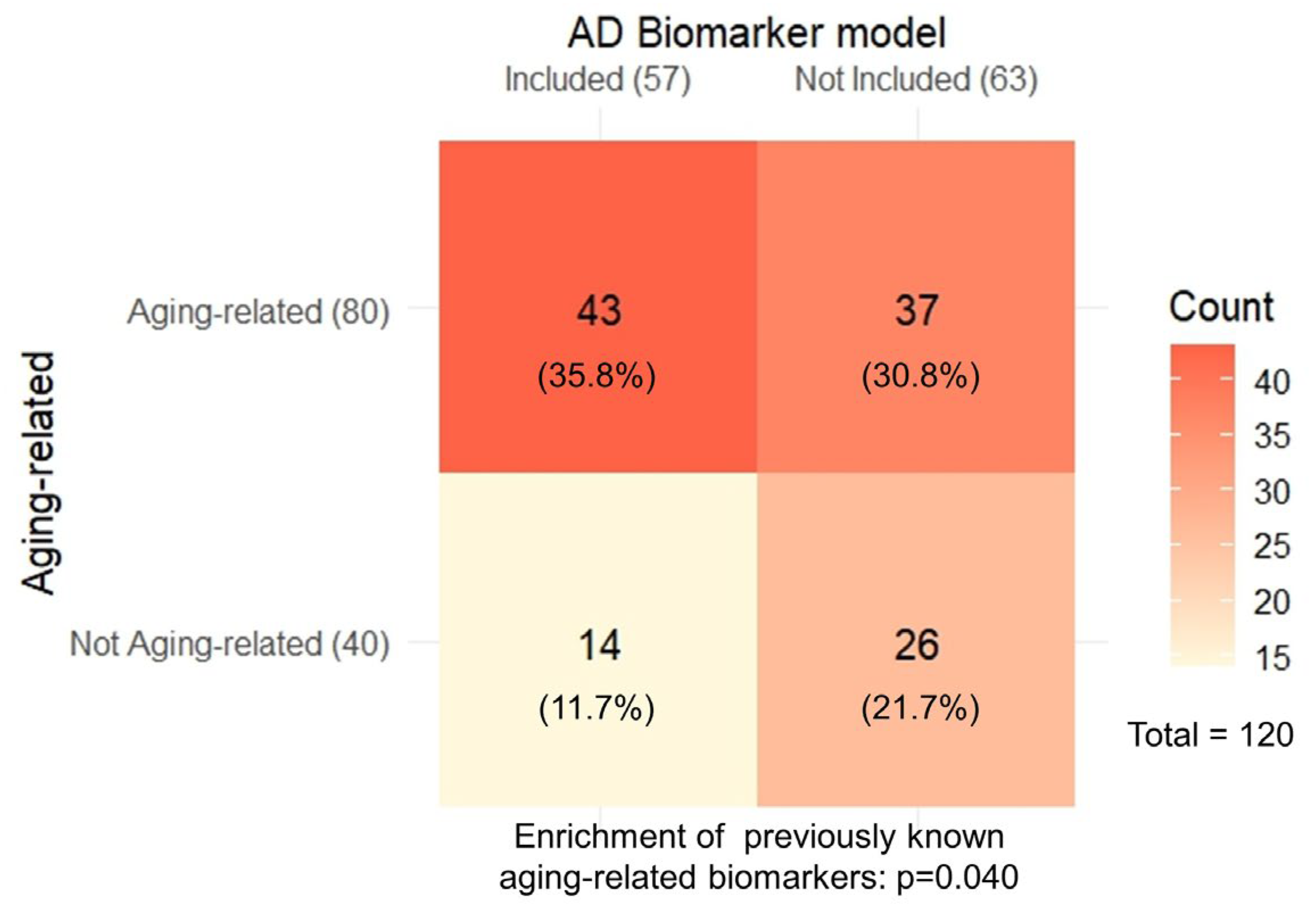

2.3. The AD Biomarkers Identified Show Overrepresentation of Aging-Related Biomarkers

2.4. The Different Models Showed Variable Performance in Predicting Other Dementia or MCI Progression to AD

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Dataset Used

4.2. Software

4.3. Development of the EBlasso, EBEN, XGBoost, LightGBM, TabNet, and TabPFN Models

4.4. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment and Network Analysis of the Overlapping Proteins

4.5. Evaluating Overlaps with Aging Models Developed in Blood

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skaria, A. The Economic and Societal Burden of Alzheimer Disease: Managed Care Considerations. 2022. Available online: https://www.ajmc.com/view/the-economic-and-societal-burden-of-alzheimer-disease-managed-care-considerations (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, F.H.; Frisoni, G.B.; Johnson, S.C.; Chen, X.; Engelborghs, S.; Ikeuchi, T.; Paquet, C.; Ritchie, C.; Bozeat, S.; Quevenco, F.-C.; et al. Clinical application of CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: From rationale to ratios. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2022, 14, e12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.J.; Richie, M. Lumbar Puncture: Technique, Indications, Contraindications, and Complications in Adults; Wolters Kluwer: Cyber City, India, 2025; Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lumbar-puncture-technique-contraindications-and-complications-in-adults (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Schindler, S.E.; Bollinger, J.G.; Ovod, V.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Li, Y.; Gordon, B.A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Xiong, C.; et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology 2019, 93, e1647–e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Horie, K.; Sato, C.; Bateman, R.J. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benussi, A.; Karikari, T.K.; Ashton, N.; Gazzina, S.; Premi, E.; Benussi, L.; Ghidoni, R.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Emeršič, A.; Simrén, J.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serum NfL and p-Tau181 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, S.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Smith, R.; Beach, T.G.; Serrano, G.E.; Chai, X.; Proctor, N.K.; Eichenlaub, U.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: Relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, T.K.; Pascoal, T.A.; Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Benedet, A.L.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Chamoun, M.; Savard, M.; Kang, M.S.; Therriault, J.; et al. Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: A diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Janelidze, S.; Palmqvist, S.; Cullen, N.; Svenningsson, A.L.; Strandberg, O.; Mengel, D.; Walsh, D.M.; Stomrud, E.; Dage, J.L.; et al. Longitudinal plasma p-tau217 is increased in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 3234–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, S.; Janelidze, S.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Zetterberg, H.; Lopera, F.; Stomrud, E.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Serrano, G.E.; Leuzy, A.; et al. Discriminative Accuracy of Plasma Phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer Disease vs Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. JAMA 2020, 324, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, N.C.; Leuzy, A.; Palmqvist, S.; Janelidze, S.; Stomrud, E.; Pesini, P.; Sarasa, L.; Allué, J.A.; Proctor, N.K.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Individualized prognosis of cognitive decline and dementia in mild cognitive impairment based on plasma biomarker combinations. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Frank, R.D.; Dage, J.L.; Jeromin, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Blennow, K.; Karikari, T.K.; Vanmechelen, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; et al. Comparison of Plasma Phosphorylated Tau Species With Amyloid and Tau Positron Emission Tomography, Neurodegeneration, Vascular Pathology, and Cognitive Outcomes. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, M.M.; Dage, J.L.; Frank, R.D.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Knopman, D.S.; Lowe, V.J.; Bu, G.; Vemuri, P.; Graff-Radford, J.; Jack, C.R.; et al. Performance of plasma phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 in the community. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1398–1405, Correction in Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2954. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02066-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscoso, A.; Grothe, M.J.; Ashton, N.J.; Karikari, T.K.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Snellman, A.; Suárez-Calvet, M.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Schöll, M.; et al. Time course of phosphorylated-tau181 in blood across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Brain 2021, 144, 325–339, Erratum in Brain 2021, 144, e57. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Simrén, J.; Leuzy, A.; Karikari, T.K.; Hye, A.; Benedet, A.L.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Schöll, M.; Mecocci, P.; Vellas, B.; et al. The diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Binette, A.P.; Strandberg, O.; Brum, W.S.; Karikari, T.K.; González-Ortiz, F.; Di Molfetta, G.; Meda, F.J.; et al. Differential roles of Aβ42/40, p-tau231 and p-tau217 for Alzheimer’s trial selection and disease monitoring. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ortiz, F.; Turton, M.; Kac, P.R.; Smirnov, D.; Premi, E.; Ghidoni, R.; Benussi, L.; Cantoni, V.; Saraceno, C.; Rivolta, J.; et al. Brain-derived tau: A novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease-type neurodegeneration. Brain 2023, 146, 1152–1165, Correction in Brain 2023, 146, 1152–1165. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kivisäkk, P.; Carlyle, B.C.; Sweeney, T.; Trombetta, B.A.; LaCasse, K.; El-Mufti, L.; Tuncali, I.; Chibnik, L.B.; Das, S.; Scherzer, C.R.; et al. Plasma biomarkers for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and prediction of cognitive decline in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1069411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Lan, G.; Lai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, X.; Bu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of plasma p-tau217/Aβ42 for Alzheimer’s disease in clinical and community cohorts. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Clears First Blood Test Used in Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-first-blood-test-used-diagnosing-alzheimers-disease (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Horie, K.; Salvadó, G.; Barthélemy, N.R.; Janelidze, S.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Saef, B.; Chen, C.D.; Jiang, H.; Strandberg, O.; et al. CSF MTBR-tau243 is a specific biomarker of tau tangle pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1954–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, W.G.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Karikari, T.K. Plasma biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders: Ready for prime time? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2023, 36, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, M.V.; Forlenza, O.V.; Diniz, B.S. Plasma Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Available Assays, Recent Developments, and Implications for Clinical Practice. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusek, M.; Smith, J.; El-Khatib, K.; Aikins, K.; Czuczwar, S.J.; Pluta, R. The Role of the JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: New Potential Treatment Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiser, A.R.; Fulop, T. Alzheimer’s Disease Is a Multi-Organ Disorder: It May Already Be Preventable. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 91, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, G.; Indaco, A.; Chiasserini, D.; Maderna, E.; Paolini Paoletti, F.; Gaetani, L.; Paciotti, S.; Petricciuolo, M.; Tagliavini, F.; Giaccone, G.; et al. Machine Learning Driven Profiling of Cerebrospinal Fluid Core Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurological Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogishvili, D.; Vromen, E.M.; Koppes-den Hertog, S.; Lemstra, A.W.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Visser, P.J.; Tijms, B.M.; Del Campo, M.; Abeln, S.; Teunissen, C.E.; et al. Discovery of novel CSF biomarkers to predict progression in dementia using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Watson, C.M.; Seyfried, N.T.; Mitchell, C.S.; Zhao, L.; Lah, J.J. Machine Learning to Stratify Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease Progression Risk with Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, e069445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, L.; Bellomo, G.; Parnetti, L.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Di Filippo, M. Neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Machine Learning Approach to CSF Proteomics. Cells 2021, 10, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficiarà, E.; Boschi, S.; Ansari, S.; D’Agata, F.; Abollino, O.; Caroppo, P.; Di Fede, G.; Indaco, A.; Rainero, I.; Guiot, C. Machine Learning Profiling of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Based on Current Cerebrospinal Fluid Markers and Iron Content in Biofluids. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 607858. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2021.607858 (accessed on 1 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Desaire, H.; Stepler, K.E.; Robinson, R.A.S. Exposing the Brain Proteomic Signatures of Alzheimer’s Disease in Diverse Racial Groups: Leveraging Multiple Data Sets and Machine Learning. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.B.; Dammer, E.B.; Duong, D.M.; Ping, L.; Zhou, M.; Yin, L.; Higginbotham, L.A.; Guajardo, A.; White, B.; Troncoso, J.C.; et al. Large-scale proteomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brain and cerebrospinal fluid reveals early changes in energy metabolism associated with microglia and astrocyte activation. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.J.; Yang, C.; Norton, J.; Johnson, M.; Fagan, A.; Bateman, R.J.; Perrin, R.J.; Morris, J.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Chhatwal, J.P.; et al. Proteomics of brain, CSF, and plasma identifies molecular signatures for distinguishing sporadic and genetic Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Britschgi, M.; Herbert, C.; Takeda-Uchimura, Y.; Boxer, A.; Blennow, K.; Friedman, L.F.; Galasko, D.R.; Jutel, M.; Karydas, A.; et al. Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1359–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Xiao, G.; Barber, R.; Reisch, J.; Doody, R.; Fairchild, T.; Adams, P.; Waring, S.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Texas Alzheimer’s Research, C. A serum protein-based algorithm for the detection of Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, C.S.; Jammeh, E.; Li, X.; Carroll, C.; Pearson, S.; Ifeachor, E. Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease with Blood Plasma Proteins Using Support Vector Machines. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 2021, 25, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.J.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Barber, I.S.; Lynham, S.; Gupta, V.; Chatterjee, P.; Goozee, K.; Hone, E.; Pedrini, S.; Blennow, K.; et al. A plasma protein classifier for predicting amyloid burden for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Petersen, M.; Johnson, L.; Hall, J.; O’Bryant, S.E. Combination of Serum and Plasma Biomarkers Could Improve Prediction Performance for Alzheimer’s Disease. Genes 2022, 13, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivisäkk, P.; Magdamo, C.; Trombetta, B.A.; Noori, A.; Kuo, Y.K.E.; Chibnik, L.B.; Carlyle, B.C.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Scherzer, C.R.; Hyman, B.T.; et al. Plasma biomarkers for prognosis of cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; You, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.-S.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Q.; Feng, J.-F.; Cheng, W.; et al. Plasma proteomic profiles predict future dementia in healthy adults. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, E.; Ali, M.; Oh, H.S.-H.; Moran-Losada, P.; Anastasi, F.; González Escalante, A.; Puerta, R.; Song, S.; et al. Large-scale plasma proteomic profiling unveils diagnostic biomarkers and pathways for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 1114–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, F.; Saloner, R.; Vogel, J.W.; Krish, V.; Abdel-Azim, G.; Ali, M.; An, L.; Anastasi, F.; Bennett, D.; Pichet Binette, A.; et al. The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium: Biomarker and drug target discovery for common neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2556–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Edwards, M.; Johnson, L.; Hall, J.; Villarreal, A.E.; Britton, G.B.; Quiceno, M.; Cullum, C.M.; Graff-Radford, N.R. A blood screening test for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 3, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llano, D.A.; Devanarayan, V.; Simon, A.J. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Evaluation of plasma proteomic data for Alzheimer disease state classification and for the prediction of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2013, 27, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.R.; Touchard, S.; Leckey, C.; O’Hagan, C.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Barkhof, F.; Bertram, L.; Blin, O.; Bos, I.; Dobricic, V.; et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease plasma. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ip, F.C.; Chan, P.; Chen, Y.; Lai, N.C.H.; Cheung, K.; Lo, R.M.N.; Tong, E.P.S.; Wong, B.W.Y.; et al. Large-scale plasma proteomic profiling identifies a high-performance biomarker panel for Alzheimer’s disease screening and staging. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Kang, J.; Svetnik, V.; Warden, D.; Wilcock, G.; David Smith, A.; Savage, M.J.; Laterza, O.F. A Machine Learning Approach to Identify a Circulating MicroRNA Signature for Alzheimer Disease. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamate, D.; Kim, M.; Proitsi, P.; Westwood, S.; Baird, A.; Nevado-Holgado, A.; Hye, A.; Bos, I.; Vos, S.J.B.; Vandenberghe, R.; et al. A metabolite-based machine learning approach to diagnose Alzheimer-type dementia in blood: Results from the European Medical Information Framework for Alzheimer disease biomarker discovery cohort. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 5, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Buckley, N.J.; Bos, I.; Engelborghs, S.; Sleegers, K.; Frisoni, G.B.; Wallin, A.; Lleo, A.; Popp, J.; Martinez-Lage, P.; et al. Plasma Proteomic Biomarkers Relating to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis Based on Our Own Studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 712545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xia, W. Proteomic Profiling of Plasma and Brain Tissue from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Reveals Candidate Network of Plasma Biomarkers. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, F.M.; Casaletto, K.B.; La Joie, R.; Walters, S.M.; Harvey, D.; Wolf, A.; Edwards, L.; Rivera-Contreras, W.; Karydas, A.; Cobigo, Y.; et al. Plasma biomarkers of astrocytic and neuronal dysfunction in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Huang, A.; Xu, S. Fast empirical Bayesian LASSO for multiple quantitative trait locus mapping. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Xu, S.; Cai, X. Empirical Bayesian elastic net for multiple quantitative trait locus mapping. Heredity 2015, 114, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 9–13 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Nair, B.; Vavilala, M.S.; Horibe, M.; Eisses, M.J.; Adams, T.; Liston, D.E.; Low, D.K.; Newman, S.F.; Kim, J.; et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arik, S.O.; Pfister, T. TabNet: Attentive Interpretable Tabular Learning. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, N.; Müller, S.; Eggensperger, K.; Hutter, F. TabPFN: A Transformer That Solves Small Tabular Classification Problems in a Second. In In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2024; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=cp5PvcI6w8_ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Hollmann, N.; Müller, S.; Purucker, L.; Krishnakumar, A.; Körfer, M.; Hoo, S.B.; Schirrmeister, R.T.; Hutter, F. Accurate predictions on small data with a tabular foundation model. Nature 2025, 637, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R115, Erratum in Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0649-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, D.W.; Caspi, A.; Corcoran, D.L.; Sugden, K.; Poulton, R.; Arseneault, L.; Baccarelli, A.; Chamarti, K.; Gao, X.; Hannon, E.; et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife 2022, 11, e73420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, I.; Tsurumi, A. Evaluating transcriptional alterations associated with ageing and developing age prediction models based on the human blood transcriptome. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Biancotto, A.; Moaddel, R.; Moore, A.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Aon, M.; Candia, J.; Zhang, P.; Cheung, F.; Fantoni, G.; et al. Plasma proteomic signature of age in healthy humans. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehallier, B.; Gate, D.; Schaum, N.; Nanasi, T.; Lee, S.E.; Yousef, H.; Moran Losada, P.; Berdnik, D.; Keller, A.; Verghese, J.; et al. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.A.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Lehallier, B. Systematic review and analysis of human proteomics aging studies unveils a novel proteomic aging clock and identifies key processes that change with age. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 60, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, L.; Lehallier, B.; de Vries, H.E.; Middeldorp, J. Markers of aging: Unsupervised integrated analyses of the human plasma proteome. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1112109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argentieri, M.A.; Xiao, S.; Bennett, D.; Winchester, L.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Ghose, U.; Albukhari, A.; Yao, P.; Mazidi, M.; Lv, J.; et al. Proteomic aging clock predicts mortality and risk of common age-related diseases in diverse populations. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2450–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacutu, R.; Thornton, D.; Johnson, E.; Budovsky, A.; Barardo, D.; Craig, T.; Diana, E.; Lehmann, G.; Toren, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Human Ageing Genomic Resources: New and updated databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1083–D1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, J.P.; Abidi, Z.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Avelar, R.A.; Barardo, D.; Chatsirisupachai, K.; Clark, P.; De-Souza, E.A.; Johnson, E.J.; Lopes, I.; et al. Human Ageing Genomic Resources: Updates on key databases in ageing research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D900–D908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chiang, H.-C.; Wu, W.; Liang, B.; Xie, Z.; Yao, X.; Ma, W.; Du, S.; Zhong, Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a preferred target for treating Amyloid-β–induced memory loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16743–16748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, L.C.D.; Highet, B.; Jansson, D.; Wu, J.; Rustenhoven, J.; Aalderink, M.; Tan, A.; Li, S.; Johnson, R.; Coppieters, N.; et al. Characterisation of PDGF-BB:PDGFRβ signalling pathways in human brain pericytes: Evidence of disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.; Severson, P.L.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Crapser, J.; Zhang, J.; Burton, E.A.; Zhang, Y.; Spevak, W.; Lin, J.; Phan, N.Y.; et al. Sustained microglial depletion with CSF1R inhibitor impairs parenchymal plaque development in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Given, K.S.; Dickson, E.L.; Owens, G.P.; Macklin, W.B.; Bennett, J.L. Concentration-dependent effects of CSF1R inhibitors on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells ex vivo and in vivo. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 318, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Yang, J.; Simanauskaite, J.; Choi, M.; Castellanos, D.M.; Chang, R.; Sun, J.; Jagadeesan, N.; Parfitt, K.D.; Cribbs, D.H.; et al. Biologic TNF-α inhibitors reduce microgliosis, neuronal loss, and tau phosphorylation in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.; Knox, J.; Chang, J.; Derbedrossian, A.; Vasilevko, V.; Cribbs, D.; Boado, R.J.; Pardridge, W.M.; Sumbria, R.K. Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrating Biologic TNF-α Inhibitor for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 2340–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.-H.; Kim, K.L.; Lee, K.-A.; Suh, W. Tie1 regulates the Tie2 agonistic role of angiopoietin-2 in human lymphatic endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 419, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnik, S.; Devraj, K.; Macas, J.; Yamaji, M.; Starke, J.; Scholz, A.; Sommer, K.; Di Tacchio, M.; Vutukuri, R.; Beck, H.; et al. Angiopoietin-2-induced blood–brain barrier compromise and increased stroke size are rescued by VE-PTP-dependent restoration of Tie2 signaling. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobov, I.B.; Brooks, P.C.; Lang, R.A. Angiopoietin-2 displays VEGF-dependent modulation of capillary structure and endothelial cell survival in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11205–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulle, C.; Ince, S.; Okonkwo, O.C.; Bendlin, B.B.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Love, S.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Elevated CSF angiopoietin-2 correlates with blood-brain barrier leakiness and markers of neuronal injury in early Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duche, A.H.; Tan, O.; Baskys, A.; Sumbria, R.K.; Roosan, M.R. Predictive gene expression signatures for Alzheimer’s disease using post-mortem brain tissue. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1591946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, S.; Love, S.; Minors, J.S. Dysregulated Angiopoietin-Tie signalling contributes to neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 20, e095139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.M.; Yano, S.; Tabassum, S.; Mitaki, S.; Michikawa, M.; Nagai, A. Alzheimer’s Amyloid β Peptide Induces Angiogenesis in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mouse through Placental Growth Factor and Angiopoietin 2 Expressions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaaraas, G.H.E.S.; Melbye, C.; Puchades, M.A.; Leung, D.S.Y.; Jacobsen, Ø.; Rao, S.B.; Ottersen, O.P.; Leergaard, T.B.; Torp, R. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Associates with Upregulated Angiopoietin and Downregulated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 83, 1651–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, A.; Plate, K.H.; Reiss, Y. Angiopoietin-2: A multifaceted cytokine that functions in both angiogenesis and inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1347, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Allen, B.; Korhonen, E.A.; Nitschké, M.; Yang, H.W.; Baluk, P.; Saharinen, P.; Alitalo, K.; Daly, C.; Thurston, G.; et al. Opposing actions of angiopoietin-2 on Tie2 signaling and FOXO1 activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3511–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, N.S.; Swanson, C.R.; Cherng, H.; Unger, T.L.; Xie, S.X.; Weintraub, D.; Marek, K.; Stern, M.B.; Siderowf, A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Plasma EGF and cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016, 3, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkqvist, M.; Ohlsson, M.; Minthon, L.; Hansson, O. Evaluation of a previously suggested plasma biomarker panel to identify Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marksteiner, J.; Kemmler, G.; Weiss, E.M.; Knaus, G.; Ullrich, C.; Mechtcheriakov, S.; Oberbauer, H.; Auffinger, S.; Hinterholzl, J.; Hinterhuber, H.; et al. Five out of 16 plasma signaling proteins are enhanced in plasma of patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Zuchowska, P.; Morris, A.W.J.; Marottoli, F.M.; Sunny, S.; Deaton, R.; Gann, P.H.; Tai, L.M. Epidermal growth factor prevents APOE4 and amyloid-beta-induced cognitive and cerebrovascular deficits in female mice. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Morris, A.W.J.; Tai, L.M. Epidermal growth factor prevents APOE4-induced cognitive and cerebrovascular deficits in female mice. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, K.P.; Thomas, R.; Morris, A.W.; Tai, L.M. Epidermal growth factor prevents oligomeric amyloid-β induced angiogenesis deficits in vitro. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2016, 36, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaswamy, P.K.; Vijaykrishnaraj, M.; Patil, P.; Alexander, L.M.; Kellarai, A.; Shetty, P. Implicative role of epidermal growth factor receptor and its associated signaling partners in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.-J.; Jeong, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Moon, M.; Hoe, H.-S. Inhibiting EGFR/HER-2 ameliorates neuroinflammatory responses and the early stage of tau pathology through DYRK1A. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Puxeddu, I.; Napoletano, S.; Scala, E.; Melillo, D.; Manocchio, S.; Angiolillo, A.; Migliorini, P.; Boraschi, D.; Vitale, E.; et al. Circulating levels of IL-1 family cytokines and receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: New markers of disease progression? J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Karima, S.; Rajaei, S.; Aghamolaii, V.; Ghahremani, H.; Ataei, R.; Tehrani, H.S.; Baram, S.M.; Tafakhori, A.; Safarpour Lima, B.; et al. Plasma Cytokines Profile in Subjects with Alzheimer’s Disease: Interleukin 1 Alpha as a Candidate for Target Therapy. Galen. Med. J. 2021, 10, e1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, W.S.; Stanley, L.C.; Ling, C.; White, L.; MacLeod, V.; Perrot, L.J.; White, C.L.; Araoz, C. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7611–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, M.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Jang, W.-C. Genetic polymorphisms of interleukin genes and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: An update meta-analysis. Meta Gene 2016, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, L.M.; Casadei, V.M.; Ferri, C.; Veglia, F.; Licastro, F.; Annoni, G.; Biunno, I.; De Bellis, G.; Sorbi, S.; Mariani, C.; et al. Association of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease with an interleukin-1alpha gene polymorphism. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Dodel, R.C.; Eastwood, B.J.; Bales, K.R.; Gao, F.; Lohmüller, F.; Müller, U.; Kurz, A.; Zimmer, R.; Evans, R.M.; et al. Association of an interleukin 1 alpha polymorphism with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2000, 55, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, J.A.; Mrak, R.E.; Graham, D.I.; Stewart, J.; Wilcock, G.; MacGowan, S.; Esiri, M.M.; Murray, L.S.; Dewar, D.; Love, S.; et al. Association of interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainero, I.; Bo, M.; Ferrero, M.; Valfrè, W.; Vaula, G.; Pinessi, L. Association between the interleukin-1α gene and Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 2004, 25, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, W.S.T.; Shenga, J.G.; Gentleman, S.M.; Graham, D.I.; Mrak, R.E.; Roberts, G.W. Microglial interleukin-1α expression in human head injury: Correlations with neuronal and neuritic β-amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 176, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.T.; Leiter, L.M.; McPhee, J.; Cahill, C.M.; Zhan, S.-S.; Potter, H.; Nilsson, L.N.G. Translation of the Alzheimer Amyloid Precursor Protein mRNA Is Up-regulated by Interleukin-1 through 5′-Untranslated Region Sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 6421–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Hartley, D.M.; Cahill, C.M.; Lahiri, D.K.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Rogers, J.T. Interleukin-1α stimulates non-amyloidogenic pathway by α-secretase (ADAM-10 and ADAM-17) cleavage of APP in human astrocytic cells involving p38 MAP kinase. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006, 84, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.C.; Hu, S.; Sheng, W.S.; Bu, D.; Bukrinsky, M.I.; Peterson, P.K. Cytokine-stimulated astrocytes damage human neurons via a nitric oxide mechanism. Glia 1996, 16, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kort, A.M.; Kuiperij, H.B.; Kersten, I.; Versleijen, A.A.M.; Schreuder, F.H.B.M.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Greenberg, S.M.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Claassen, J.A.H.R.; Verbeek, M.M. Normal cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of PDGFRβ in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masliah, E.; Mallory, M.; Alford, M.; Deteresa, R.; Saitoh, T. PDGF is associated with neuronal and glial alterations of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Halliday, M.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Toga, A.W.; Jacobs, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Amezcua, L.; et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 2015, 85, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.D.; Winkler, E.A.; Sagare, A.P.; Singh, I.; LaRue, B.; Deane, R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Pericytes Control Key Neurovascular Functions and Neuronal Phenotype in the Adult Brain and during Brain Aging. Neuron 2010, 68, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armulik, A.; Genové, G.; Mäe, M.; Nisancioglu, M.H.; Wallgard, E.; Niaudet, C.; He, L.; Norlin, J.; Lindblom, P.; Strittmatter, K.; et al. Pericytes regulate the blood–brain barrier. Nature 2010, 468, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iihara, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Tsukahara, T.; Sakata, M.; Yanamoto, H.; Taniguchi, T. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB, but not -AA, prevents delayed neuronal death after forebrain ischemia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1997, 17, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, T.; Wen, T.-C.; Matsuda, S.; Ishihara, K.; Otsuka, H.; Sakanaka, M. Platelet-derived growth factor prevents ischemia-induced neuronal injuries in vivo. Neurosci. Res. 1997, 29, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, T.; Özen, I.; Boix, J.; Barbariga, M.; Gaceb, A.; Roth, M.; Paul, G. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB has neurorestorative effects and modulates the pericyte response in a partial 6-hydroxydopamine lesion mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 94, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Teng, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Geng, F.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB protects dopaminergic neurons via activation of Akt/ERK/CREB pathways to upregulate tyrosine hydroxylase. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 1300–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Fang, C.-L.; Shen, K.; Qian, C.; Qi, C.; Li, T.; Gao, P.; Wong, P.C.; et al. Elevated PDGF-BB from Bone Impairs Hippocampal Vasculature by Inducing PDGFRβ Shedding from Pericytes. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2206938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Shu, W.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Fang, S.; Zheng, H.; Cheng, W.; Lin, Q.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, N.; et al. Bone-derived PDGF-BB enhances hippocampal non-specific transcytosis through microglia-endothelial crosstalk in HFD-induced metabolic syndrome. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-P. Cytokine Protein Arrays. In Protein Arrays: Methods and Protocols; Fung, E.T., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 215–231. ISBN 978-1-59259-759-8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F., Jr. Python Reference Manual; Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Huang, A.; Liu, D. EBglmnet: A comprehensive R package for sparse generalized linear regression models. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1627–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Github. Github-xgboost. Available online: https://github.com/dmlc/xgboost/tree/master (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Github. Github-lightgbm. Available online: https://github.com/microsoft/LightGBM/tree/master (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, F. Bayesian Optimization: Open Source Constrained Global Optimization Tool for Python. 2014. Available online: https://github.com/bayesian-optimization/BayesianOptimization (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Github. Github-shap. Available online: https://github.com/shap/shap (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Github. Github-pytorch_tabnet. Available online: https://github.com/dreamquark-ai/tabnet/tree/develop (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8024–8035. [Google Scholar]

- Github. Github-PriorLabs/TabPFN: Foundation Model for Tabular Data. Available online: https://github.com/PriorLabs/TabPFN (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Github. Github-PriorLabs/TabPFN-extensions. Available online: https://github.com/PriorLabs/tabpfn-extensions (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Robin, X.; Turck, N.; Hainard, A.; Tiberti, N.; Lisacek, F.; Sanchez, J.C.; Muller, M. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.; Sergeant, E. epiR: Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data. R Package Version 2.0.78. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epiR (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Gao, C.-H.; Dusa, A. ggVennDiagram: A ‘ggplot2’ Implement of Venn Diagram. R Package Version 1.5.2. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/gaospecial/ggVennDiagram (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Snel, B.; Lehmann, G.; Bork, P.; Huynen, M. STRING: A web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 3442–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, H.; Carlson, M.; Falcon, S.; Li, N. AnnotationDbi: Manipulation of SQLite-Based Annotations in Bioconductor. R Package Version 1.66.0. 2024. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/AnnotationDbi (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Carlson, M. org.Hs.eg.db: Genome Wide Annotation for Human. R Package Version 3.20.0. 2024. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db (accessed on 22 December 2024).

| AD vs. CN Classification Models | ||

|---|---|---|

| PAM ML 18 Plasma Proteins | Accuracy = 89% (Training and Test) | Ray S. et al., 2007 [35] |

| SVM ML 7 to 10 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.86 to 0.89 | Eke CS. et al., 2021 [37] |

| Four models with 5 to 14 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.759 to 0.838 (CV), 0.737 to 0.842 (ext. valid.) | Llano DA. et al., 2013 [45] |

| 9 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.79 (training and ext. valid.) | Sung YJ. et al., 2023 [34] |

| 5 plasma proteins + age + APOE genotype | AUC = 0.79, 0.81 (ext. valid.) | Morgan AR. et al., 2019 [46] |

| Ridge + SVM ML 11 plasma proteins + age | AUC = 0.891 (test) | Ashton NJ. et al., 2019 [38] |

| 19 hub plasma proteins | AUC = 0.969 (ext. valid.) | Jiang Y. et al., 2022 [47] |

| SVM ML 4 plasma + 6 serum proteins | AUC = 99.98% (training), 93.96% (test) | Zhang F. et al., 2022 [39] |

| LGBM ML 4 plasma proteins + demographic + cognition | AUC = 0.913 | Guo Y. et al., 2024 [41] |

| Lasso ML 7 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.796 (test), 0.721 (replication), 0.715 and 0.757 (ext. valid.) | Heo G. et al., 2025 [42] |

| Random Forest ML 14 serum proteins | AUC = 0.91 (training), 0.88 (test) | O’Bryant SE. et al., 2010 [36] |

| 21 serum proteins + age + sex + education | AUC = 0.89 | O’Bryant SE. et al., 2016 [44] |

| XGBoost ML plasma metabolite | AUC = 0.88 (test) | Stamate D. et al., 2019 [49] |

| 12 serum miRNA | Accuracy = 76% | Zhao X. et al., 2020 [48] |

| AD vs. MCI Classification or Prognostic Models | ||

| 3 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.74 (training), 0.67 (ext. valid.) | Morgan AR. et. al., 2019 [46] |

| SVM ML 7 to 10 plasma proteins | AUC = 0.80 to 0.83 | Eke CS. et. al., 2021 [37] |

| Lasso-ML selected 12 plasma proteins + plasma Aβ + plasma pTau + baseline cognitive measures + age + sex + education + APOE genotype | AUC = 0.88, accuracy = 86.7% (test)—prognostic model for MCI-progressors vs. MCI-stable | Kivisäkk P. et. al., 2022 [40] |

| EBlasso (7 Proteins) | EBEN (9 Proteins) | XGBoost (36 Proteins) | LightGBM (20 Proteins) | TabNet (27 Proteins) | TabPFN (26 Proteins) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | ||||||

| Accuracy | 0.916 [0.834–0.965] | 0.916 [0.834–0.965] | 0.988 [0.935–1.00] | 0.964 [0.898–0.992] | 0.831 [0.733–0.905] | 0.988 [0.935–1.000] |

| Sensitivity/recall | 0.930 [0.809–0.985] | 0.907 [0.779–0.974] | 0.977 [0.877–0.999] | 0.977 [0.877–0.999] | 0.884 [0.749–0.961] | 1.00 [0.918–1.000] |

| Specificity | 0.900 [0.763–0.972] | 0.925 [0.796–0.984] | 1.000 [0.912–1.000] | 0.950 [0.831–0.994] | 0.775 [0.615–0.892] | 0.975 [0.868–0.999] |

| PPV/precision | 0.909 [0.783–0.975] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] | 1.000 [0.916–1.000] | 0.955 [0.845–0.994] | 0.809 [0.667–0.909] | 0.977 [0.880–0.999] |

| NPV | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] | 0.902 [0.769–0.973] | 0.976 [0.871–0.999] | 0.974 [0.865–0.999] | 0.861 [0.705–0.952] | 1.00 [0.910–1.000] |

| Test set | ||||||

| Accuracy | 0.914 [0.830–0.965] | 0.827 [0.727–0.902] | 0.926 [0.846–0.972] | 0.938 [0.862–0.980] | 0.901 [0.815–0.956] | 0.926 [0.846–0.972] |

| Sensitivity/recall | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] | 0.833 [0.686–0.930] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] | 0.952 [0.838–0.994] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] |

| Specificity | 0.897 [0.758–0.971] | 0.821 [0.665–0.925] | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] | 0.872 [0.726–0.957] | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] |

| PPV/precision | 0.907 [0.779–0.974] | 0.833 [0.686–0.930] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] | 0.930 [0.809–0.985] | 0.886 [0.754–0.962] | 0.929 [0.805–0.985] |

| NPV | 0.921 [0.786–0.983] | 0.821 [0.665–0.925] | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] | 0.947 [0.823–0.994] | 0.919 [0.781–0.983] | 0.923 [0.791–0.984] |

| Correct Classification | EBlasso (7 Proteins) | EBEN (9 Proteins) | XGBoost (36 Proteins) | LightGBM (20 Proteins) | TabNet (26 Proteins) | TabPFN (26 Proteins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other dementia (n = 11) | 10 (90.9%) | 10 (90.9%) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 7 (63.6%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| Correct Classification | EBlasso (7 Proteins) | EBEN (9 Proteins) | XGBoost (36 Proteins) | LightGBM (20 Proteins) | TabNet (26 Proteins) | TabPFN (26 Proteins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI-AD (n = 22) | 19 (86.4%) | 20 (90.9%) | 17 (77.3%) | 16 (72.7%) | 14 (63.6%) | 18 (81.8%) |

| MCI-OD-FTD (n = 1) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) |

| MCI-OD-LBD (n = 3) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) |

| MCI-OD-VaD (n = 4) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| MCI-MCI (n = 17) | 4 not AD/ 13 AD | 8 not AD/ 9 AD | 4 not AD/ 13 AD | 7 not AD/ 10 AD | 8 not AD/ 9 AD | 4 not AD/ 13 AD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsurumi, A.; Cahill, C.M.; Liu, A.J.; Chatterjee, P.; Das, S.; Kobayashi, A. Development of Plasma Protein Classification Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multiple Machine Learning Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311673

Tsurumi A, Cahill CM, Liu AJ, Chatterjee P, Das S, Kobayashi A. Development of Plasma Protein Classification Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multiple Machine Learning Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311673

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsurumi, Amy, Catherine M. Cahill, Andy J. Liu, Pranam Chatterjee, Sudeshna Das, and Ami Kobayashi. 2025. "Development of Plasma Protein Classification Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multiple Machine Learning Approaches" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311673

APA StyleTsurumi, A., Cahill, C. M., Liu, A. J., Chatterjee, P., Das, S., & Kobayashi, A. (2025). Development of Plasma Protein Classification Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multiple Machine Learning Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311673